Submitted:

06 December 2024

Posted:

09 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

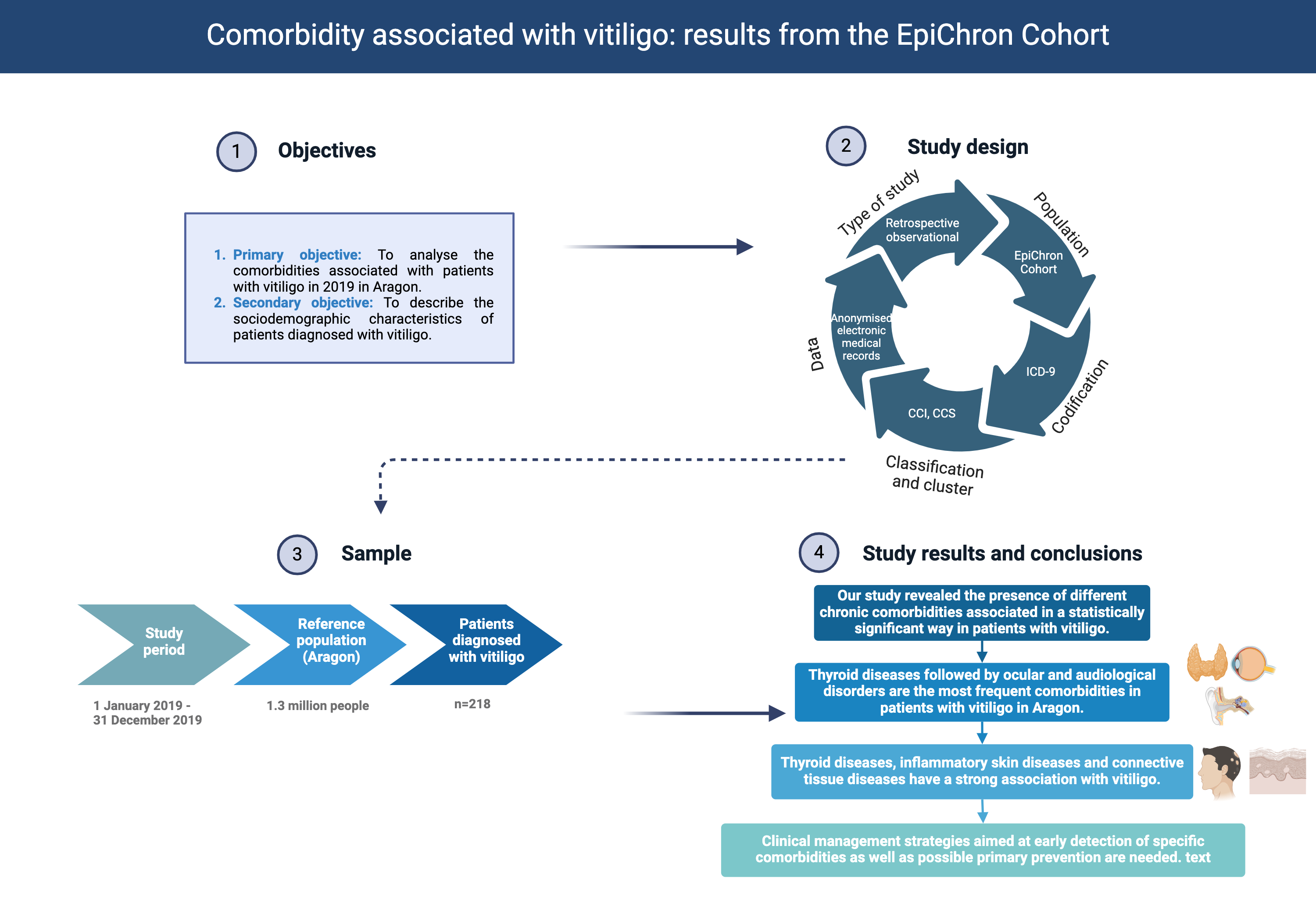

Background: Vitiligo is linked to a range of systemic, autoimmune and dermatologic diseases, some of which may not have been described in the literature. Methods: An observational, retrospective study based on the clinical information of the individuals of the EpiChron Cohort (Aragon, Spain; reference population 1.3 million inhabitants) with a diagnosis of vitiligo between 1 January and 31 December 2019 was conducted. The main socio-demographic and clinical characteristics were described, as well as the likelihood of presenting vitiligo based on sex, age, nationality, area of residence and the area's deprivation index. The prevalence of chronic comorbidities was calculated, and logistic regression models were used to obtain the crude and age- and sex-adjusted odds ratios (OR) of each comorbidity (dependent variable) according to the presence or not of vitiligo (independent variable). Results: 218 patients diagnosed with vitiligo were analysed (56.42% women). The mean age was 44.0 years. The diseases associated the most with vitiligo were thyroid disorders (OR 3.01, p<0.000), ocular and hearing anomalies (OR 1.54, p=0.020), inflammatory disorders of the skin (OR 2.21, p<0.000), connective tissue diseases (OR 1.84, p=0.007), lower respiratory diseases (OR 1.78, p=0.014), urinary tract infections (OR 1.69, p=0.032) and cardiac dysrhythmias (OR 1.84, p=0.034). Conclusion: This research highlights the importance of understanding the broader health implications of vitiligo and provides a foundation for further exploration into the complex interplay between this dermatologic condition and a diverse range of comorbidities.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Variables and Data Sources

2.3. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Population

3.2. Chronic Comorbidities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mastacouris N, Strunk A, Garg A. Incidence and Prevalence of Diagnosed Vitiligo According to Race and Ethnicity, Age, and Sex in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2023 Sep 1;159(9):986-990. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Whitton M, van Geel N. Vitiligo. Lancet. 2015 Jul 4;386(9988):74-84. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahir AM, Thomsen SF. Comorbidities in vitiligo: comprehensive review. Int J Dermatol. 2018 Oct;57(10):1157-1164. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisoli ML, Essien K, Harris JE. Vitiligo: Mechanisms of Pathogenesis and Treatment. Annu Rev Immunol. 2020 Apr 26;38:621-648. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchioro HZ, Silva de Castro CC, Fava VM, Sakiyama PH, Dellatorre G, Miot HA. Update on the pathogenesis of vitiligo. An Bras Dermatol. 2022 Jul-Aug;97(4):478-490. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taieb A, Alomar A, Böhm M, Dell'anna ML, De Pase A, Eleftheriadou V, Ezzedine K, Gauthier Y, Gawkrodger DJ, Jouary T, Leone G, Moretti S, Nieuweboer-Krobotova L, Olsson MJ, Parsad D, Passeron T, Tanew A, van der Veen W, van Geel N, Whitton M, Wolkerstorfer A, Picardo M; Vitiligo European Task Force (VETF); European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV); Union Europe´enne des Me´decins Spe´cialistes (UEMS). Guidelines for the management of vitiligo: the European Dermatology Forum consensus. Br J Dermatol. 2013 Jan;168(1):5-19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergqvist C, Ezzedine K. Vitiligo: A Review. Dermatology. 2020;236(6):571-592. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taïeb A, Picardo M; VETF Members. The definition and assessment of vitiligo: a consensus report of the Vitiligo European Task Force. Pigment Cell Res. 2007 Feb;20(1):27-35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee JH, Ju HJ, Seo JM, Almurayshid A, Kim GM, Ezzedine K, Bae JM. Comorbidities in Patients with Vitiligo: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2023 May;143(5):777-789.e6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu Z, Wang T. Beyond skin white spots: Vitiligo and associated comorbidities. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023 Feb 23;10:1072837. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan KC, Yang TH, Huang YC. Vitiligo and thyroid disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Dermatol. 2018 Dec 1;28(6):750-763. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prados-Torres A, Poblador-Plou B, Gimeno-Miguel A, Calderón-Larrañaga A, Poncel-Falcó A, Gimeno-Feliú LA, González-Rubio F, Laguna-Berna C, Marta-Moreno J, Clerencia-Sierra M, Aza-Pascual-Salcedo M, Bandrés-Liso AC, Coscollar-Santaliestra C, Pico-Soler V, Abad-Díez JM. Cohort Profile: The Epidemiology of Chronic Diseases and Multimorbidity. The EpiChron Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2018 Apr 1;47(2):382-384f. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compés Dea ML, Olivan Bellido E, Feja Solana C, Aguilar Palacio I, García-Carpintero Romero Del Hombrebueno G, Adiego Sancho B. Construcción de un índice de privación por zona básica de salud en Aragón a partir de datos de censo de 2011 [Construction of a deprivation index by Basic Healthcare Area in Aragon using Population and Housing Census 2011]. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2018 Dec 10;92:e201812087. Spanish. [PubMed]

- Chronic Condition Indicator (CCI) for ICD-9-CM [Internet]. [cited 2023 Nov 22]. Available from: https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic/chronic.

- Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM [Internet]. [cited 2023 Nov 22]. Available from: https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.

- Moreno-Juste A, Gimeno-Miguel A, Poblador-Plou B, Calderón-Larrañaga A, Cano Del Pozo M, Forjaz MJ, Prados-Torres A, Gimeno-Feliú LA. Multimorbidity, social determinants and intersectionality in chronic patients. Results from the EpiChron Cohort. J Glob Health. 2023 Feb 3;13:04014. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krüger C, Schallreuter KU. A review of the worldwide prevalence of vitiligo in children/adolescents and adults. Int J Dermatol. 2012 Oct;51(10):1206-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almenara-Blasco M, Carmona-Pírez J, Gracia-Cazaña T, Poblador-Plou B, Pérez-Gilaberte JB, Navarro-Bielsa A, Gimeno-Miguel A, Prados-Torres A, Gilaberte Y. Comorbidity Patterns in Patients with Atopic Dermatitis Using Network Analysis in the EpiChron Study. J Clin Med. 2022 Oct 29;11(21):6413. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rios-Duarte JA, Sanchez-Zapata MJ, Silverberg JI. Association of vitiligo with multiple cutaneous and extra-cutaneous autoimmune diseases: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023 Nov;315(9):2597-2603. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim JH, Lew BL, Sim WY, Kwon SH. Incidence of childhood-onset vitiligo and increased risk of atopic dermatitis, autoimmune diseases, and psoriasis: A nationwide population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022 Nov;87(5):1196-1198. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen YT, Chen YJ, Hwang CY, Lin MW, Chen TJ, Chen CC, Chu SY, Lee DD, Chang YT, Liu HN. Comorbidity profiles in association with vitiligo: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015 Jul;29(7):1362-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu Z, Wang T. Beyond skin white spots: Vitiligo and associated comorbidities. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023 Feb 23;10:1072837. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genedy R, Assal S, Gomaa A, Almakkawy B, Elariny A. Ocular and auditory abnormalities in patients with vitiligo: a case-control study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021 Aug;46(6):1058-1066. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopal KV, Rama Rao GR, Kumar YH, Appa Rao MV, Vasudev P; Srikant. Vitiligo: a part of a systemic autoimmune process. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007 May-Jun;73(3):162-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kussainova A, Kassym L, Akhmetova A, Glushkova N, Sabirov U, Adilgozhina S, Tuleutayeva R, Semenova Y. Vitiligo and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020 Nov 10;15(11):e0241445. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen CY, Wang WM, Chung CH, Tsao CH, Chien WC, Hung CT. Increased risk of psychiatric disorders in adult patients with vitiligo: A nationwide, population-based cohort study in Taiwan. J Dermatol. 2020 May;47(5):470-475. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padmakar S, Murti K, Pandey K, Kumari S, Kumar R, Siddiqui NA, et al. Suicidal ideation associated with vitiligo - A systematic review of prevalence and assessment. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2022 Sep 1;17:101140. [CrossRef]

- Montgomery SN, Syder N, Barajas G, Elbuluk N. Psychological comorbidities of vitiligo: a retrospective cross-sectional analysis in an urban population. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023 Dec 4;316(1):14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezzedine K, Soliman AM, Li C, Camp HS, Pandya AG. Comorbidity Burden Among Patients with Vitiligo in the United States: A Large-Scale Retrospective Claims Database Analysis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023 Oct;13(10):2265-2277. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Men | Women | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 95 (43.58) | 123 (56.42) | 218 (100) |

| Mean age, years (SD1) | 42.45 (22.97) | 45.15 (19.85) | 43.97 (21.26) |

| Age group, years (n, %) | |||

| 0–17 | 23 (24.21) | 13 (10.57) | 36 (16.51) |

| 18–44 | 23 (24.21) | 53 (43.09) | 76 (34.86) |

| 45–64 | 31 (32.63) | 36 (29.27) | 67 (30.73) |

| ≥65 | 18 (18.95) | 21 (17.07) | 39 (17.89) |

| Nationality (n, %) | |||

| Spain | 71 (74.74) | 94 (76.42) | 165 (75.69) |

| Eastern Europe | 4 (4.21) | 8 (6.50) | 12 (5.50) |

| Asia | 0 (0) | 1 (0.81) | 1 (0.46) |

| North Africa | 4 (4.21) | 3 (2.44) | 7 (3.21) |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 1 (1.05) | 1 (0.81) | 2 (0.92) |

| Latin America | 14 (14.74) | 16 (13.01) | 30 (13.76) |

| EU and North America | 1 (1.05) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.46) |

| Area of residence | |||

| Urban2 (n, %) | 58 (61.05) | 70 (56.91) | 128 (58.72) |

| Deprivation index3 (n, %) | |||

| Q1 | 13 (13.68) | 37 (30.08) | 50 (22.94) |

| Q2 | 30 (31.58) | 29 (23.58) | 59 (27.06) |

| Q3 | 24 (25.26) | 18 (14.63) | 42 (19.27) |

| Q4 | 28 (29.47) | 39 (31.71) | 67 (30.73) |

| Number of chronic diseases (mean, SD) | 2.75 (1.92) | 3.56 (2.68) | 3.21 (2.41) |

| Multimorbidity, yes (n, %) | 62 (65.26) | 94 (76.42) | 156 (71.56) |

| 1 Standard deviation; 2 Versus rural; 3 Deprivation index of the residence area according to 26 socio-economic indicators and categorized from least (Q1) to most (Q4) deprived | |||

| Variable | Crude OR1 | p-value | Adjusted OR2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Men | ref. | |||

| Woman | 1.14 (0.87-1.48) | 0.349 | ||

| Age group (years) | ||||

| 0–17 | ref. | |||

| 18–44 | 0.93 (0.63-1.38) | 0.724 | ||

| 45–64 | 0.73 (0.49-1.09) | 0.129 | ||

| ≥65 | 0.48 (0.30-0.76) | 0.002 | ||

| Nationality | ||||

| Spain | ref. | ref. | ||

| Eastern Europe | 1.07 (0.27-4.32) | 0,924 | 1.01 (0.25-4.08) | 0,987 |

| Asia | 0.99 (0.14-7.09) | 0,994 | 0.91 (0.13-6.52) | 0,927 |

| North Africa | 1.56 (0.87-2.80) | 0,139 | 1.45 (0.81-2.61) | 0,213 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 3.30 (2.23-4.87) | 0,000 | 3.06 (2.07-4.53) | 0,000 |

| Latin America | 2.04 (0.96-4.36) | 0,064 | 1.92 (0.90-4.10) | 0,091 |

| EU and North America | 0.60 (0.08-4.27) | 0,607 | 0.60 (0.08-4.26) | 0,606 |

| Area of residence | ||||

| Urban | ref. | ref. | ||

| Rural | 1.07 (0.82-1.41) | 0,597 | 1.08 (0.83-1.42) | 0,552 |

| Deprivation index3 (n, %) | ||||

| Q1 | ref. | ref. | ||

| Q2 | 1.27 (0.87-1.86) | 0,208 | 1.29 (0.88-1.88) | 0,188 |

| Q3 | 1.08 (0.72-1.62) | 0,720 | 1.10 (0.73-1.66) | 0,650 |

| Q4 | 1.28 (0.89-1.85) | 0,181 | 1.30 (0.90-1.88) | 0,160 |

| 1 Odds ratio; 2 adjusted odds ratios for sex and age; 3 Deprivation index of the residence area according to 26 socio-economic indicators and categorized from least (Q1) to most (Q4) deprived | ||||

| Comorbidity | Prevalence | Crude OR | Adjusted OR1 | p-value2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | ||

| Disorders of lipid metabolism | 60 (27.5) | 0.86 (0.64-1.15) | 1.11 (0.80-1.53) | 0.532 |

| Thyroid disorders | 55 (25.2) | 2.58 (1.90-3.50) | 3.01 (2.18-4.15) | 0.000* |

| Hypertension | 50 (22.9) | 0.74 (0.54-1.02) | 1.12 (0.76-1.63) | 0.569 |

| Other nutritional; endocrine; and metabolic disorders | 41 (18.8) | 0.97 (0.69-1.36) | 1.18 (0.83-1.68) | 0.356 |

| Spondylosis; intervertebral disc disorders; other back problems | 39 (17.9) | 1.26 (0.89-1.78) | 1.42 (1.00-2.02) | 0.051 |

| Other ear and sense organ disorders | 35 (16.1) | 1.41 (0.98-2.02) | 1.54 (1.07-2.22) | 0.020* |

| Anxiety disorders | 29 (13.3) | 0.91 (0.61-1.34) | 0.92 (0.62-1.36) | 0.660 |

| Blindness and vision defects | 28 (12.8) | 1.47 (0.99-2.19) | 1.44 (0.97-2.15) | 0.070 |

| Menstrual disorders | 24 (11.0) | 1.39 (0.91-2.13) | 1.23 (0.78-1.94) | 0.364 |

| Other inflammatory condition of skin | 24 (11.0) | 2.15 (1.41-3.29) | 2.21 (1.45-3.38) | 0.000* |

| Osteoarthritis | 23 (10.6) | 0.95 (0.62-1.47) | 1.50 (0.93-2.41) | 0.093 |

| Other upper respiratory disease | 22 (10.1) | 0.79 (0.51-1.23) | 0.75 (0.48-1.16) | 0.196 |

| Other connective tissue disease | 22 (10.1) | 1.77 (1.14-2.76) | 1.84 (1.19-2.87) | 0.007* |

| Allergic reactions | 22 (10.1) | 1.05 (0.67-1.63) | 0.91 (0.58-1.43) | 0.674 |

| Depression and mood disorders | 22 (10.1) | 0.78 (0.50-1.21) | 0.88 (0.56-1.37) | 0.563 |

| Headache; including migraine | 21 (9.6) | 0.97 (0.62-1.52) | 0.89 (0.57-1.40) | 0.624 |

| Other lower respiratory disease | 20 (9.2) | 1.78 (1.12-2.82) | 1.78 (1.12-2.82) | 0.014* |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 20 (9.2) | 0.96 (0.61-1.53) | 1.39 (0.86-2.27) | 0.181 |

| Asthma | 19 (8.7) | 1.23 (0.77-1.98) | 1.16 (0.72-1.85) | 0.546 |

| Urinary tract infections | 19 (8.7) | 1.58 (0.98-2.52) | 1.69 (1.05-2.73) | 0.032* |

| Neoplasms | 16 (7.3) | 1.25 (0.75-2.08) | 1.49 (0.89-2.49) | 0.131 |

| Genitourinary symptoms and ill-defined conditions | 15 (6.9) | 0.91 (0.54-1.53) | 1.32 (0.76-2.29) | 0.323 |

| Obesity | 15 (6.9) | 0.69 (0.41-1.17) | 0.76 (0.45-1.29) | 0.316 |

| Cardiac dysrhythmias | 14 (6.4) | 1.26 (0.74-2.17) | 1.84 (1.05-3.22) | 0.034* |

| 1 odds ratios adjusted by sex and age; 2 p-values for the adjusted OR; * p<0.05. | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).