1. Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that varies from mild to severe and affects both genders with similar prevalence, manifesting at any age.[

1] However, the onset of psoriasis exhibits a bimodal age distribution,[

2] characterized by early-onset before the age of 40 and late-onset after the age of 40.[

3] Early-onset psoriasis is strongly associated with genetic factors, such as the HLA-Cw6 allele, a family history of the disease, and more severe and extensive cutaneous involvement.[

4,

5,

6,

7] Psoriasis treatment strategy is based on severity: mild cases typically involve topical therapies such as corticosteroids and vitamin D analogs, moderate to severe cases may require phototherapy or systemic treatments like methotrexate and cyclosporine, while severe cases often rely on biological therapies (biologics) targeting immune pathways like TNF-alpha and IL-17 inhibitors.[

8,

9] Regardless of severity, lifestyle modifications are essential for effective disease management.[

10]

Despite the similar prevalence between genders, men often experience more severe forms of psoriasis. Studies have demonstrated higher median Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) scores in men compared to women,[

11] and men's higher use of biologic treatments reflects greater disease severity.[

12] Additionally, a recent study from our group identified transcriptomic differences in psoriatic lesions between men and women, revealing sex-specific molecular pathways and immune cell variations that may contribute to the observed disparities in disease severity. (

Unpublished Data) The reasons for these gender differences remain unclear but are thought to be multifactorial, involving hormonal, genetic, and psychosocial factors.[

13] Our study utilized electronic health records (EHR) from Clalit Health Services (CHS) in Israel, to examine gender-based and onset-based differences in treatment patterns in order to improve personalized treatment approaches and patient care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

The study is based on electronic health records extracted from the CHS database, the largest Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) in Israel, serving a population of more than 4.5 million people as of 2024. Data was extracted by the North District's Research Data Center, using the Clalit Research Data sharing platform for de-identified data powered by MDClone (

https://www.mdclone.com). The electronic health records were recorded between 1998-2022, (excluding some retroactive diagnoses from before 1998) and contained clinical and administrative data collected in hospitals (inpatient clinics and emergency room settings), primary care clinics, pharmacies, laboratories, and diagnostic and imaging centers. The data is also linked to national databases providing socio-demographic information related to patients and clinics. The data were specifically extracted from the CHS database focusing on inflammatory diseases.

2.2. Definition of Cohort

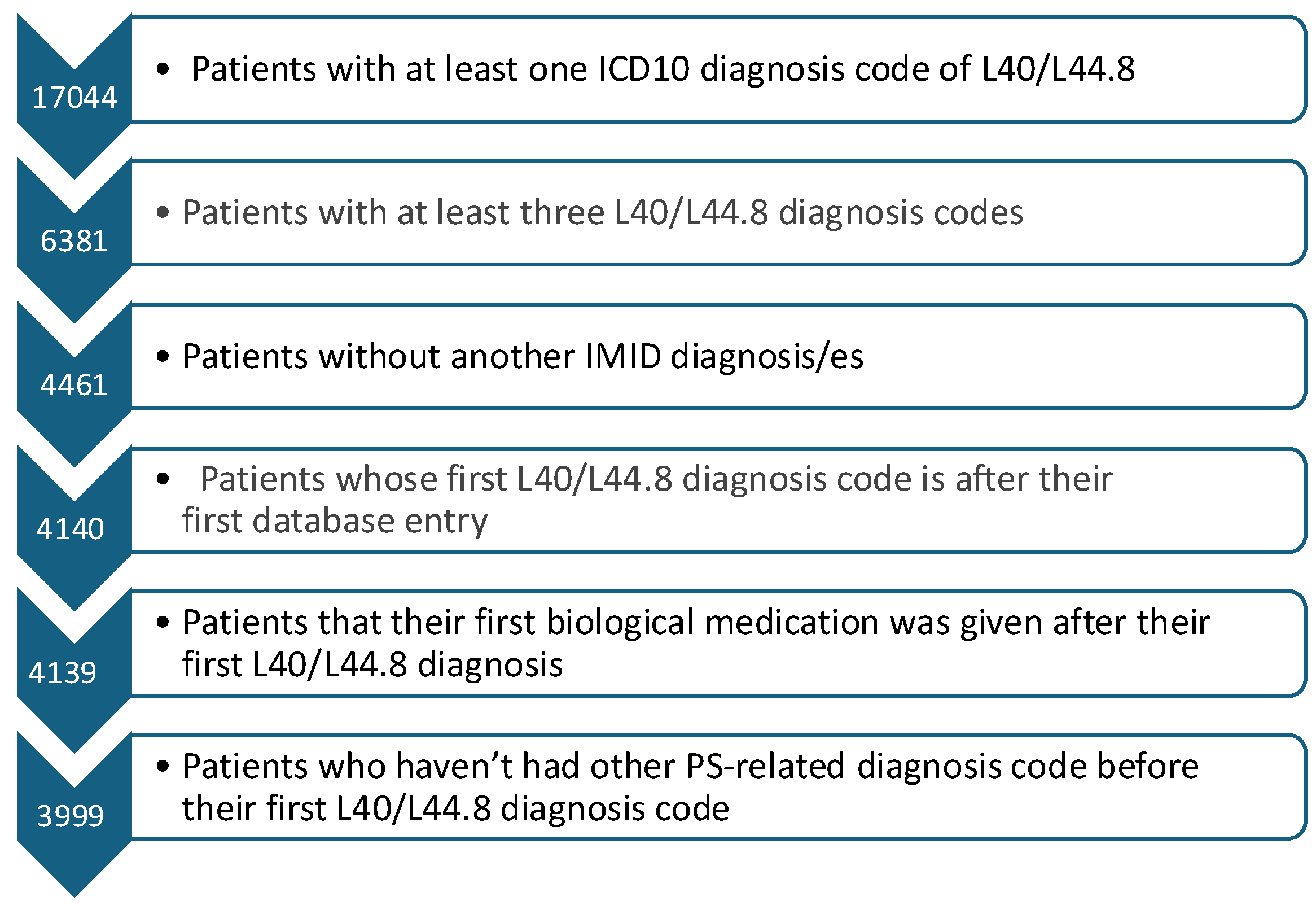

We defined the psoriasis cohort using a previously described algorithm [

14] requiring each patient to have at least three records of psoriasis diagnosis codes. ICD-10 codes L40 and L44.8, and ICD-9 codes 696, 696.1, and 696.8 were defined as the optimal diagnosis codes for psoriasis. Patients with other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs), such as rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, and psoriatic arthritis, were excluded to minimize confounding factors. To ensure data accuracy, we excluded patients whose initial psoriasis diagnosis coincided with their first database entry, as this indicated retrospective data inclusion. Additionally, patients with any other psoriasis-related diagnoses before their first confirmed diagnosis were excluded to establish the true onset of psoriasis (

Table A1). A graphical representation of this psoriasis-cohort selection is provided in

Figure A1.

2.3. Baseline Characteristics

We identified the onset date of psoriasis by the first recorded ICD-10 diagnosis code of L40 or L44.8 in the database. Patients were classified as either early-onset (diagnosed before age 40) or late-onset (diagnosed at age 40 or older). We assessed the proportion of individuals reporting smoking or physical activity, as well as BMI and obesity rates, using the measurements closest to the defined onset date. The obesity rate was calculated using BMI, with obesity defined as a BMI greater than 30. We evaluated the socio-economic distribution across three scale parameters: low, median, and high.

2.4. Treatments

The systemic medications included in the analysis were Acitretin (Neotigason), Methotrexate, Cyclosporine, and Otezela. The biologic medications analyzed were Remicade, Enbrel, Humira, Stelara, Cosentyx, Taltz, Tremfya, Ilumya, and Skyrizi. No records for Bimzelx or Siliq were available in the database. Cimzia was administrated to only 2 patients in the psoriasis cohort and was excluded from the analysis.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

We represented continuous variables (age at onset and BMI) by median and IQR and analyzed them using the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test. Categorical variables, representing proportions within a selected population (smoking, obesity, physical activity, and socioeconomic distribution), were tested using Chi-square test. For cases with missing patient data, we specified in parentheses the number of patients included in the analysis.

We used Fisher's exact test to analyze differences in the proportions of biological, systemic or phototherapy treatments between males and females by psoriasis-onset. We calculated the proportion of patients with at least one record of the specified medication or phototherapy, relative to the total number of patients in each gender category.

The time from psoriasis onset to initiation of systemic or phototherapy treatment was estimated using Kaplan–Meier survival curves to account for the varying follow-up times, with patients censored if they did not receive treatment during the observation period. (Time was calculated from the date of the initial psoriasis diagnosis to the date of the last recorded entry in the database, indicating the end of record tracking for the patient.) Patients who commenced treatment before their first diagnosis of psoriasis (43 out of 615 patients who received systemic treatment and 13 out of 240 patients who received phototherapy) and patients whose initial diagnosis occurred before January 1, 2000, were excluded from the survival analysis. The survival analysis was performed using the “ggsurvfit” R package. All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.2.3). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

A flow chart of the selection of the cohort according to the inclusion criteria is depicted in

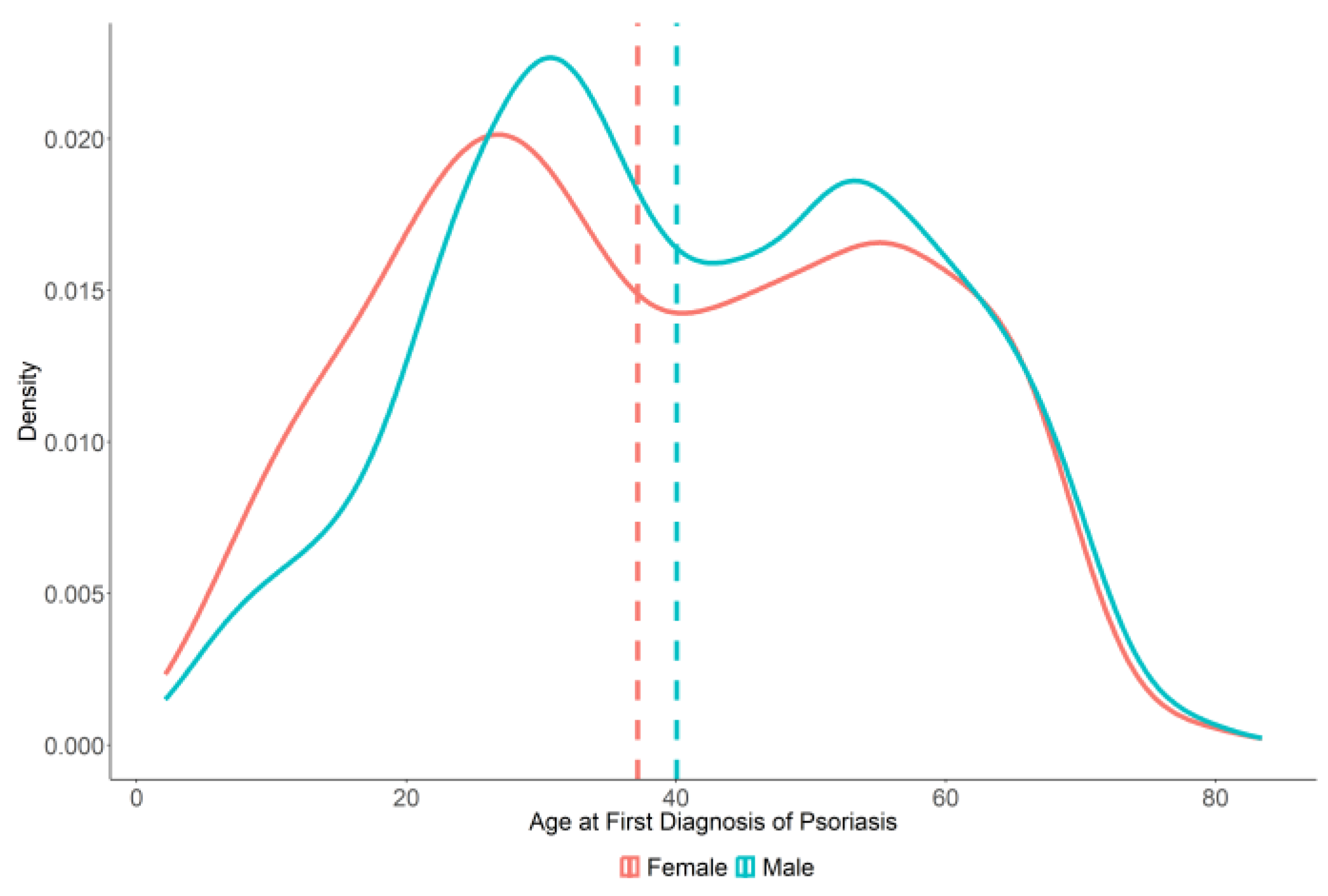

Figure A1. A total of 3999 patients met the inclusion criteria. Among them, 2613 were male (65.3%). The age distribution at psoriasis onset showed a bimodal pattern in both genders, with women tending to have an earlier onset compared to men (

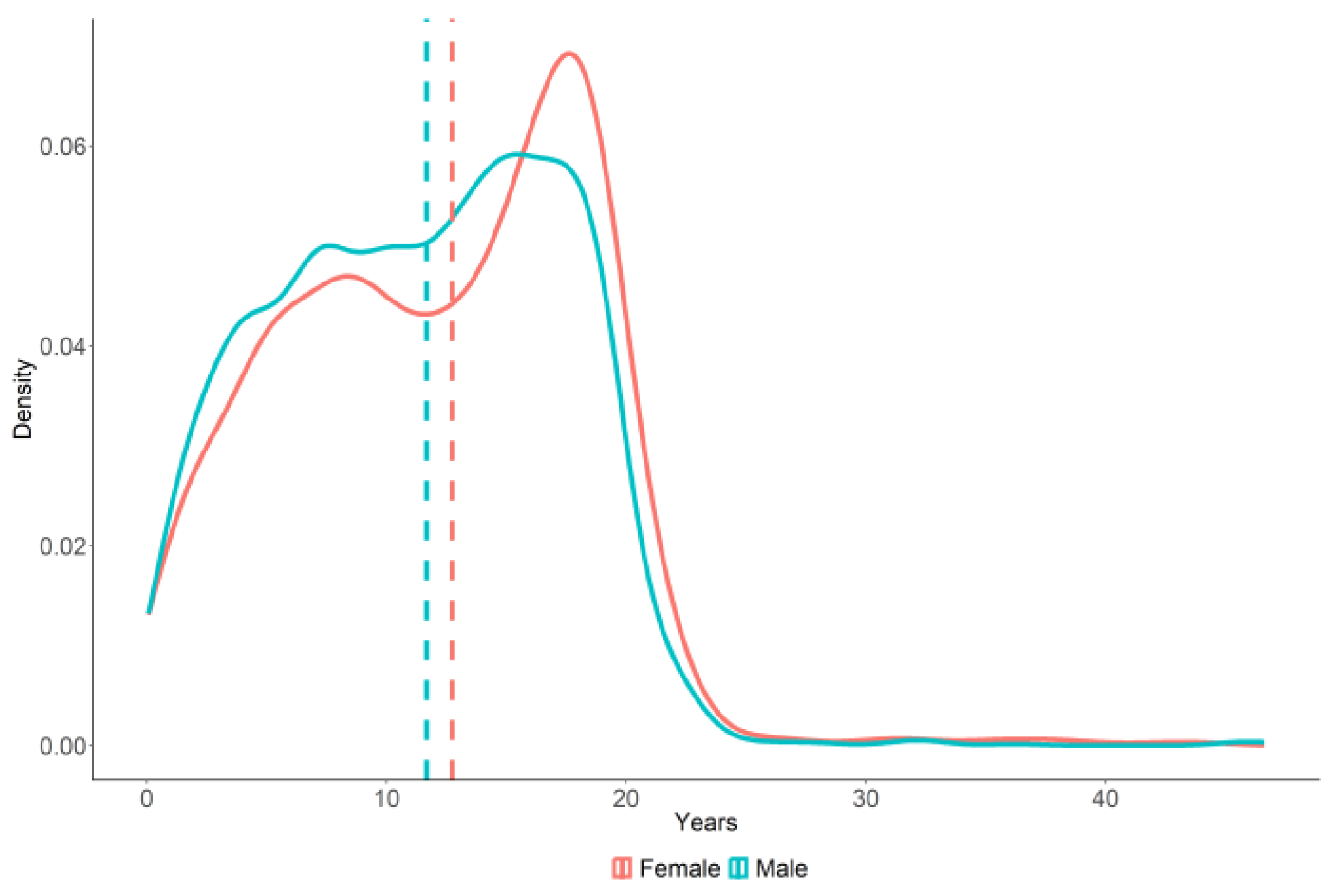

Figure B1). The median follow-up period in the psoriasis cohort was approximately 11 years for males and 12 years for females. (

Figure B2)

We analyzed the baseline characteristics between men and women (

Table 1), finding that men in the entire cohort and in the early onset subgroup were diagnosed at an older age (p<0.001) and had higher rates of smoking and higher BMI (p<0.001). In contrast, obesity rates, physical activity, and socioeconomic distribution were similar between genders. Among late-onset patients, males had a significantly higher smoking rate, while all other parameters were similar between genders, except for a higher, non-statistically significant rate of obesity among women compared to men.

3.2. Comparison of Psoriasis Treatment Management and Time to Treatment Initiation Between Male and Female

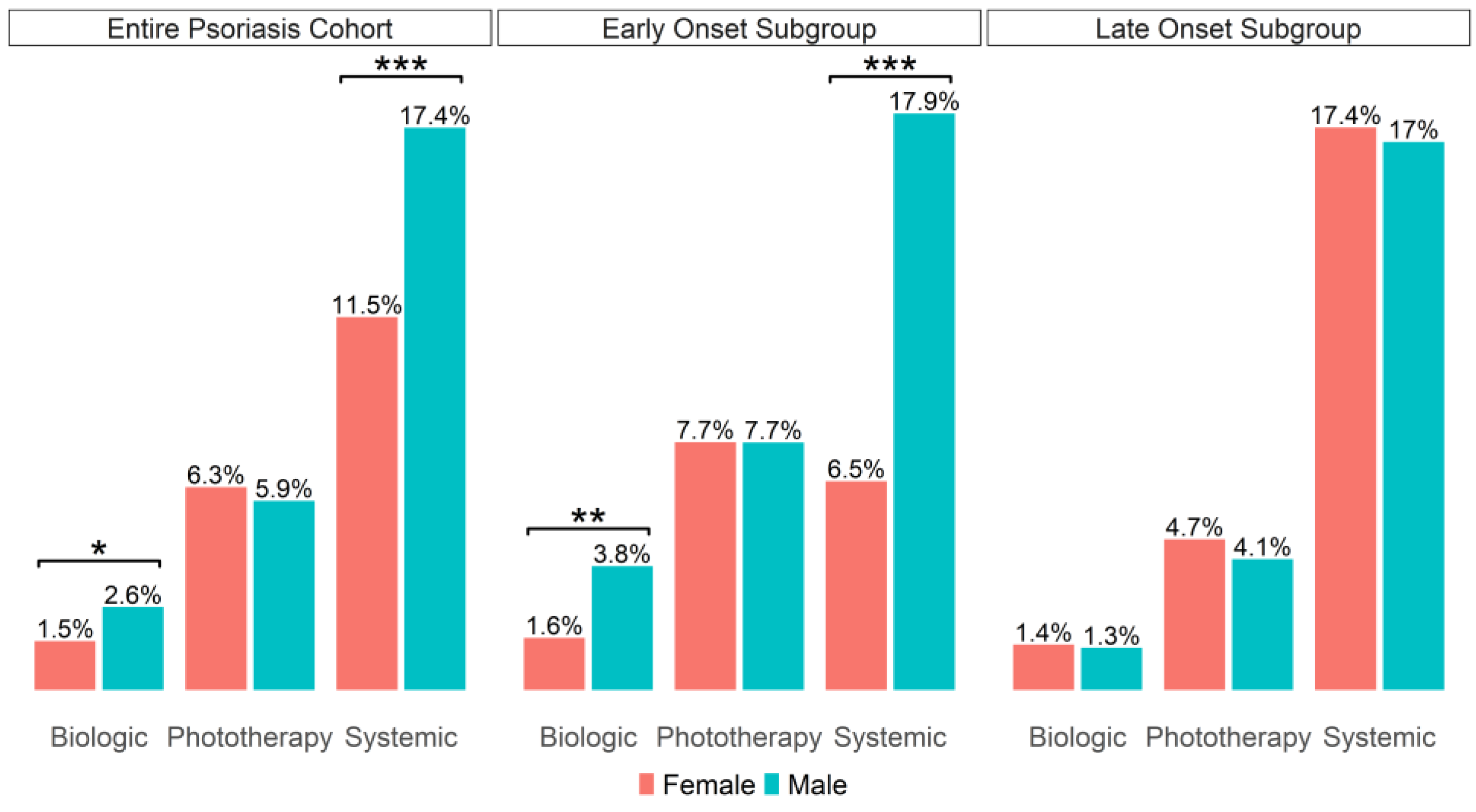

To determine if there is a gender-dependent effect on therapy modality, we compared any use of phototherapy, systemic, and biologic treatment, among men and women. While no statistically significant difference was found in phototherapy rates between genders, males demonstrated higher biologic and systemic treatment usage (p=0.03, p<0.001, respectively), as illustrated in

Figure 1 (left). To understand the association between the age of disease onset and gender, we analyzed the early- and late-onset cohorts separately. In the early-onset subgroup, men exhibited significantly greater use of biologic and systemic medications than women (p=0.005, p<0.001, respectively), with phototherapy rates remaining equal (

Figure 1, middle). Conversely, in the late-onset subgroup, treatment rates, including systemic, biologic, and phototherapy, showed no gender disparity (

Figure 1, right).

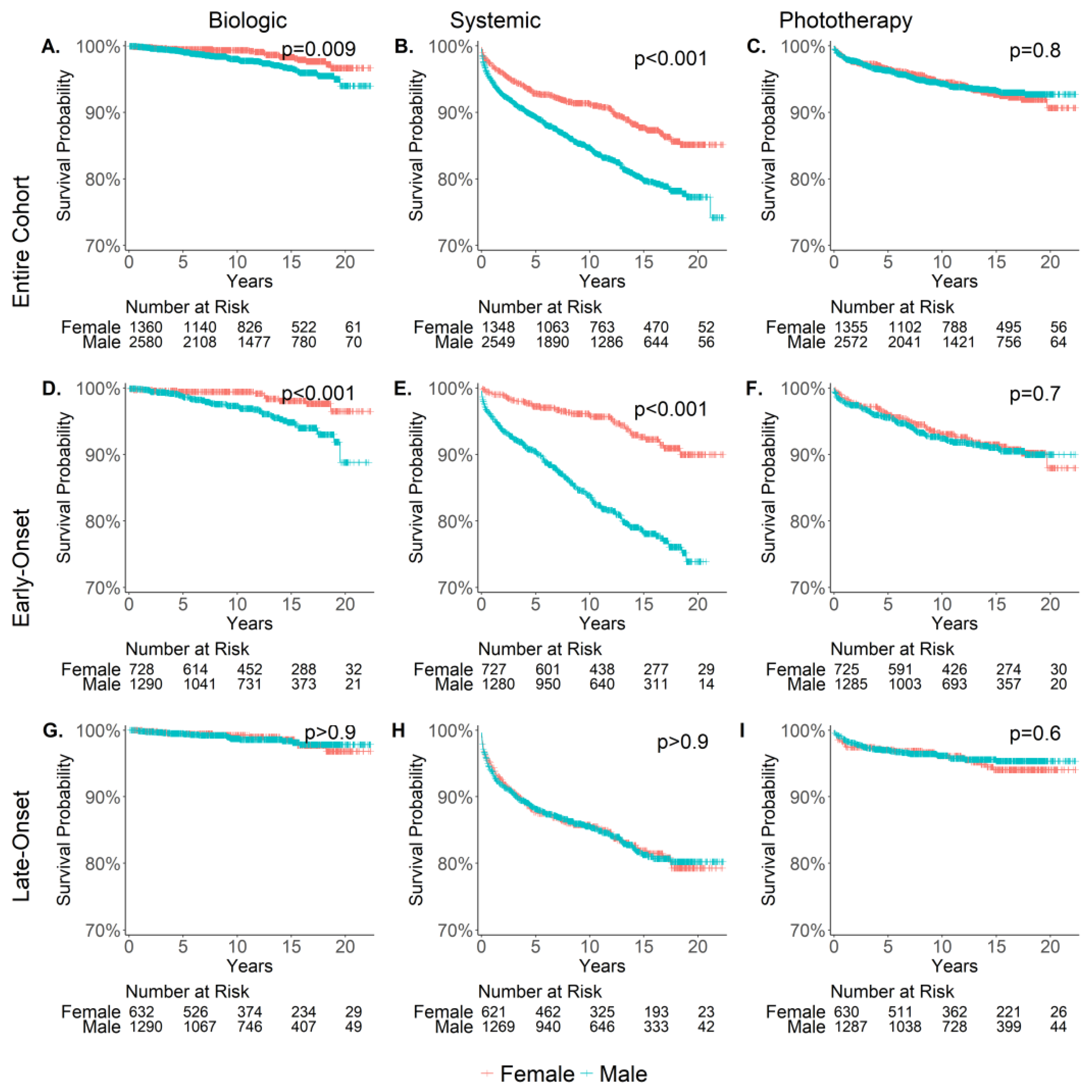

A similar trend was observed in a survival analysis (

Figure 2) conducted to evaluate the time from the onset of psoriasis to the initiation of a new treatment (phototherapy, systemic or biologic). In the entire cohort, men received systemic and biologic treatment significantly sooner than women, (

Figure 2A,B) a pattern that was also evident in the early-onset subgroup (

Figure 2D,E). No significant differences were observed in the late-onset subgroup (

Figure 2G,H). This finding suggests that the significance observed in the entire cohort is primarily driven by the early-onset group. Regarding phototherapy, the time elapsed from the onset of psoriasis to the first phototherapy treatment showed no significant gender-based differences in either the early or late subgroup (

Figure 2F,I).

3.3. Comparison of Time to Treatment Initiation Between Early-Onset and Late-Onset Patients

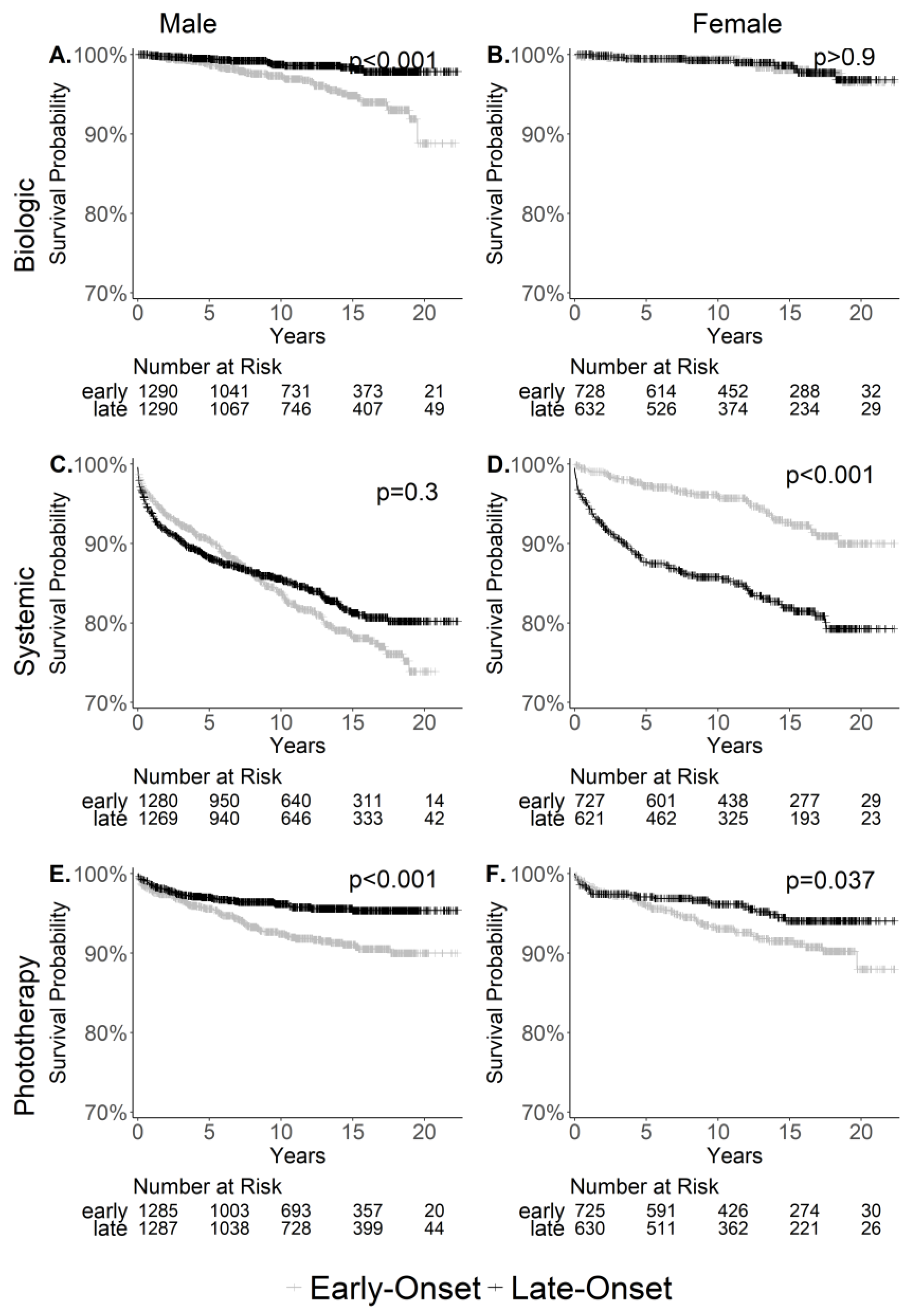

To further understand the different patterns of treatment initiation among early and late onset patients, we compared the time from onset to treatment initiation between early-onset and late-onset males (

Figure 3 Left), as well as between early-onset and late-onset females (

Figure 3 Right). Among males, early-onset patients received biologic and phototherapy treatments significantly sooner than late-onset patients, although the time to systemic treatment initiation was similar between early and late-onset males (

Figure 3A,C,E). For females, late-onset patients initiated systemic treatment earlier (

Figure 3D), while there was no significant difference in the time to biologic treatment initiation (

Figure 3B). Similar to males, early-onset females received phototherapy sooner than late-onset females (

Figure 3F).

4. Discussion

Over the past decade, studies evaluating the severity of affected areas in psoriasis have shown that men tend to have more extensive and severe manifestations of the disease than women.[

11,

12,

15,

16] Additionally, previous studies have highlighted distinct psychological [

17], clinical [

3,

18], and genetic [

5,

19] characteristics between early-onset and late-onset psoriasis.

In line with other studies, we found that significantly more men received higher lines of therapy, suggesting a higher severity of psoriasis among men. However, after dividing the patients into early and late-onset subgroups, this trend was evident only in the early-onset subgroup. This is in agreement with previous studies indicating a notable difference in PASI scores between sexes in those under 30.[

11,

12]

Our finding may stem from clinicians' caution in prescribing systemic or biologic treatments to women of childbearing age, as many immunosuppressive medications carry risks of teratogenic effects and potential complications during pregnancy and breastfeeding.[

20] In the early-onset subgroup, 52.8% of women experienced one or more pregnancies after disease onset, which may explain the observed disparity in treatment. This may suggest that many women of childbearing age receive suboptimal treatment, highlighting the need for continued research on the safety of biologics during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

However, this explanation alone cannot account for the higher PASI scores or extent of involvement reported in men in other studies [

11,

12,

15,

16]. Therefore, given the median follow-up period for women of about 12 years (see

Figure B2), it is reasonable to assume that women with severe psoriasis would likely have been recommended treatment during intervals when pregnancy planning was not an issue. Additionally, certain biologic drugs such as infliximab, adalimumab, and certolizumab pegol (Cimzia) may be considered for use during pregnancy and lactation in severe cases.[

21] This suggests that biological differences, along with gender-based behaviors, could affect the course of the disease.

For example, variations in hormones and metabolism might influence disease severity compared to men. Both clinical and animal models have shown that hormones play a key role in mediating sex-specific differences in immune responses [

22,

23]. In psoriasis, these hormonal differences may influence the course of the disease. For example, the role of estrogen in human psoriasis is not fully understood, however, multiple studies suggest that estrogen has anti-inflammatory effects on the disease.[

24,

25,

26,

27] In addition, in a study of 47 pregnant psoriasis patients, 55% reported improvement during pregnancy, while postpartum, only 9% reported improvement.[

26] Average monthly estrogen levels are significantly higher in younger women and decline with age.[

28] Therefore, we hypothesized that estrogen plays a role in moderating psoriasis severity in young women, and the similarity in treatment rates observed between men and women in older age may be partly due to decreased estrogen levels in women. Supporting this, a study by Mowad et al found that 48% of menopausal women experienced psoriasis exacerbation, while only 2% showed improvement.[

29] Furthermore, later age at natural menopause and longer reproductive years were significantly associated with a reduced risk of late-onset psoriasis.[

30]

At the same time, it's important to highlight evidence suggesting that estrogen may also have pro-inflammatory effects on psoriasis, indicating a potential dual role for estrogen that varies depending on the context.[

31] Additionally, women in the early-onset cohort had lower rates of smoking and lower BMI compared to both early-onset men and late-onset patients, which may also help explain the differences between genders. Apart from biological differences, behavioral aspects may also contribute to the differences between genders. Women are often more cautious about adopting new treatments, as they tend to perceive medical risks as higher [

32] and have greater concerns about potential side effects, whereas men may be more open to innovative therapies.

Our study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, it lacked information on the extent of psoriasis involvement or PASI scores, limiting our ability to fully assess disease severity in the study population. The data, recorded between 1999 and 2002, may also have gaps or incomplete records. Furthermore, the study included significantly more males than females, and the use of biologics was not consistently distributed across the years.

5. Conclusions

Our findings indicate that the timing of disease onset may play a role in treatment decisions, emphasizing the importance of a more personalized approach to psoriasis management that accounts for both gender and age at onset.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MS.D.; methodology, T.L. and E.S.; software, T.L.; formal analysis, T.L.; investigation, T.L., E.S., N.F., G.S., MiS.D., E.G., I.M and MS.D; writing—original draft preparation, T.L. and E.S.; writing—review and editing, MS.D., I.M. and N.F; visualization, T.L.; supervision, MS.D.; project administration, S.A.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by The Milken Family Foundation (T.L).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board of CHS (protocol code 0110-21-COM2 6.12.2021).

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were accessed under a specific data-sharing agreement with Clalit Health Services (CHS), Israel. Access to these data is restricted to protect patient confidentiality and is available only to researchers who obtain permission from CHS following submission and approval of a detailed research protocol. Data analyses were conducted within the CHS research room as required by CHS policy. Researchers interested in accessing the data or computing code should contact Clalit Health Services directly to inquire about the data access procedure.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the "Clalit Health Services Research Room Team" for data access and technical support. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used ChatGPT-3 and ChatGPT-4 for the purposes of language editing, phrasing, and clarification of ideas. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this manuscript. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CHS |

Clalit Health Services |

| PASI |

Psoriasis Area Severity Index |

| EHR |

Electronic Health Records |

| HMO |

Health Maintenance Organization |

| IMIDs |

Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Psoriasis-related diagnoses which not included in the psoriasis cohort criteria.

Table A1.

Psoriasis-related diagnoses which not included in the psoriasis cohort criteria.

| Diagnosis |

ICD10 |

ICD9/other codes |

| Impetigo Herpetiformis |

L40.1 |

6943 |

| Parapsoriasis |

L41 |

6962 |

| Intertrigo Psoriasis |

L53.8 |

6958 |

| Poikikoderma Vasculare Atrophicans |

unknown |

6962 |

| Psoriasis w/wo Arthropathy |

unknown |

S91 |

Figure A1.

A graphical representation of the psoriasis cohort selection process.

Figure A1.

A graphical representation of the psoriasis cohort selection process.

Appendix B

Appendix B.1

Figure B1.

Distribution of males and females by age at first diagnosis of psoriasis. The dashed lines indicate the medians for males and females.

Figure B1.

Distribution of males and females by age at first diagnosis of psoriasis. The dashed lines indicate the medians for males and females.

Appendix B.2

Figure B2.

Distribution of time from psoriasis onset to the patient's last recorded date in the database. The dashed lines indicate the medians for males and females.

Figure B2.

Distribution of time from psoriasis onset to the patient's last recorded date in the database. The dashed lines indicate the medians for males and females.

References

- Eder, L.; Widdifield, J.; Rosen, C.F.; Cook, R.; Lee, K.; Alhusayen, R.; Paterson, M.J.; Cheng, S.Y.; Jabbari, S.; Campbell, W.; et al. Trends in the Prevalence and Incidence of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis in Ontario, Canada: A Population-Based Study. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken) 2019, 71, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schonmann, Y.; Ashcroft, D.M.; Iskandar, I.Y.K.; Parisi, R.; Sde-Or, S.; Comaneshter, D.; Batat, E.; Shani, M.; Vinker, S.; Griffiths, C.E.M.; et al. Incidence and Prevalence of Psoriasis in Israel between 2011 and 2017. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 2075–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henseler, T.; Christophers, E. Psoriasis of Early and Late Onset: Characterization of Two Types of Psoriasis Vulgaris. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1985, 13, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiro, R.; Tejón, P.; Alonso, S.; Coto, P. Age at Disease Onset: A Key Factor for Understanding Psoriatic Disease. Rheumatology 2014, 53, 1178–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coto-Segura, P.; Vázquez-Coto, D.; Velázquez-Cuervo, L.; García-Lago, C.; Coto, E.; Queiro, R. The IFIH1/MDA5 Rs1990760 Gene Variant (946Thr) Differentiates Early- vs. Late-Onset Skin Disease and Increases the Risk of Arthritis in a Spanish Cohort of Psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallon, E.; Bunker, C.B.; Newson, R. HLA-Cw6 and the Genetic Predisposition to Psoriasis: A Meta-Analysis of Published Serologic Studies. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1999, 113, 693–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrándiz, C.; Pujol, R.M.; García-Patos, V.; Bordas, X.; Smandía, J.A. Psoriasis of Early and Late Onset: A Clinical and Epidemiologic Study from Spain. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2002, 46, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.W.; Read, C. Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation, and Treatment of Psoriasis. JAMA 2020, 323, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J.; Kim, M. Challenges and Future Trends in the Treatment of Psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.-H.; Chi, C.-C.; Yeh, M.-L.; Wang, S.-H.; Tsai, Y.-S.; Hsu, M.-Y. Lifestyle Changes for Treating Psoriasis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägg, D.; Sundström, A.; Eriksson, M.; Schmitt-Egenolf, M. Severity of Psoriasis Differs Between Men and Women: A Study of the Clinical Outcome Measure Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) in 5438 Swedish Register Patients. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2017, 18, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägg, D.; Eriksson, M.; Sundström, A.; Schmitt-Egenolf, M. The Higher Proportion of Men with Psoriasis Treated with Biologics May Be Explained by More Severe Disease in Men. PLoS One 2013, 8, e63619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N. Application of Sex/Gender-Specific Medicine in Healthcare. Korean J. Women Health Nurs. 2023, 29, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eder, L.; Widdifield, J.; Rosen, C.F.; Alhusayen, R.; Cheng, S.Y.; Young, J.; Campbell, W.; Bernatsky, S.; Gladman, D.D.; Paterson, M.; et al. Identifying and Characterizing Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Patients in Ontario Administrative Data: A Population-Based Study From 1991 to 2015. J. Rheumatol. 2020, 47, 1644–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, S.J.; Jo, S.J.; Youn, J. Il Clinical Study on Psoriasis Patients for Past 30 Years (1982–2012) in Seoul National University Hospital Psoriasis Clinic. J. Dermatol. 2013, 40, 731–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Komy, M.H.M.; Mashaly, H.; Sayed, K.S.; Hafez, V.; El-Mesidy, M.S.; Said, E.R.; Amer, M.A.; AlOrbani, A.M.; Saadi, D.G.; El-Kalioby, M.; et al. Clinical and Epidemiologic Features of Psoriasis Patients in an Egyptian Medical Center. JAAD Int. 2020, 1, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remröd, C.; Sjöström, K.; Svensson, Å. Psychological Differences between Early- and Late-Onset Psoriasis: A Study of Personality Traits, Anxiety and Depression in Psoriasis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2013, 169, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chularojanamontri, L.; Kulthanan, K.; Suthipinittharm, P.; Jiamton, S.; Wongpraparut, C.; Silpa-Archa, N.; Tuchinda, P.; Sirikuddta, W. Clinical Differences between Early- and Late-onset Psoriasis in Thai Patients. Int. J. Dermatol. 2015, 54, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Tsai, T.-F. HLA-Cw6 and Psoriasis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 178, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nast, A.; Smith, C.; Spuls, P.I.; Avila Valle, G.; Bata-Csörgö, Z.; Boonen, H.; De Jong, E.; Garcia-Doval, I.; Gisondi, P.; Kaur-Knudsen, D.; et al. EuroGuiDerm Guideline on the Systemic Treatment of Psoriasis Vulgaris – Part 2: Specific Clinical and Comorbid Situations. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, 281–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchner, A.; Gröchenig, H.P.; Sautner, J.; Helmy-Bader, Y.; Juch, H.; Reinisch, S.; Högenauer, C.; Koch, R.; Hermann, J.; Studnicka-Benke, A.; et al. Immunosuppressives and Biologics during Pregnancy and Lactation. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2019, 131, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbels Bupp, M.R. Sex, the Aging Immune System, and Chronic Disease. Cell Immunol. 2015, 294, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarra, F.; Campolo, F.; Franceschini, E.; Carlomagno, F.; Venneri, M. Gender-Specific Impact of Sex Hormones on the Immune System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, N.; Watanabe, S. Regulatory Roles of Sex Hormones in Cutaneous Biology and Immunology. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2005, 38, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, A.; Honda, T. Regulatory Roles of Estrogens in Psoriasis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murase, J.E.; Chan, K.K.; Garite, T.J.; Cooper, D.M.; Weinstein, G.D. Hormonal Effect on Psoriasis in Pregnancy and Post Partum. Arch. Dermatol. 2005, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cemil, B.C.; Cengiz, F.P.; Atas, H.; Ozturk, G.; Canpolat, F. Sex Hormones in Male Psoriasis Patients and Their Correlation with the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index. J. Dermatol. 2015, 42, 500–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanczyk, F.Z.; Clarke, N.J. Measurement of Estradiol—Challenges Ahead. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowad, C.M.; Margolis, D.J.; Halpern, A.C.; Suri, B.; Synnestvedt, M.; Guzzo, C.A. Hormonal Influences on Women with Psoriasis. Cutis 1998, 61, 257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Yi, Y.; Jing, D.; Yang, S.; Guo, Y.; Xiao, H.; Kuang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; et al. Age at Natural Menopause, Reproductive Lifespan, and the Risk of Late-Onset Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis in Women: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 144, 1273–1281.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; He, M.; Jiang, J.; Duan, X.; Chai, B.; Zhang, J.; Tao, Q.; Chen, H. Triggers for the Onset and Recurrence of Psoriasis: A Review and Update. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.R.; Jenkins, M. Gender Differences in Risk Assessment: Why Do Women Take Fewer Risks than Men? Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2006, 1, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).