1. Introduction

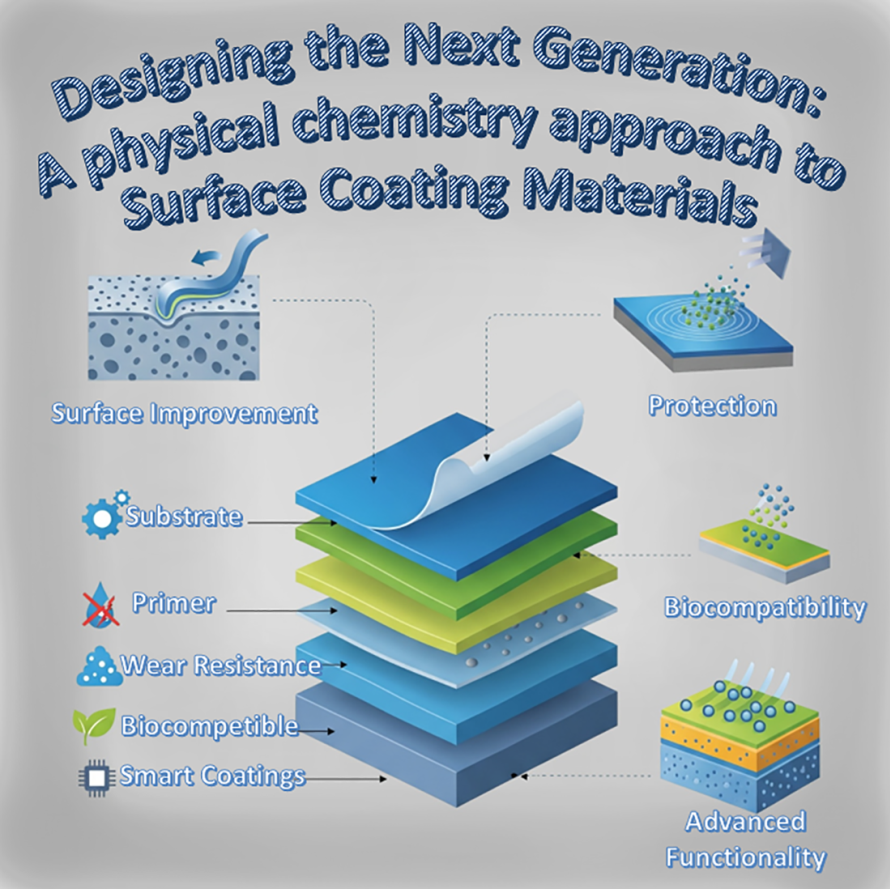

Surface coatings are protective and decorative layers applied to various substrates, such as metal, wood, plastic or concrete, to improve properties such as aesthetics, durability and functionality [

1]. In addition to preventing phenomena such as corrosion, wear and the influence of environmental factors, they also contribute to enhancing performance characteristics such as high temperature resistance, electrical conductivity and chemical resistance [

2,

3]. Depending on the requirements of the application, coating materials can be deposited using methods ranging from simple techniques such as brushing and spraying to more complex processes such as thermal spraying, electroplating or chemical vapor deposition [

1]. Thanks to this adaptability, surface coatings are a key factor in many sectors, including construction, automotive, aerospace, electronics and packaging, as they extend the life of materials and enhance both their performance and aesthetic value [

4].

They can be used to tailor or modify the properties of the material. There are many types of surface coating materials, based on organic, inorganic, polymeric, or composite structures, that can give the surface curtain properties, like self-healing or anti-corrosive [

4,

5,

6]. Their application is important because of the protection and performance improvement they impart to the bulk materials. Surface coating materials can protect against UV radiation, reduce friction or prevent rusting and degradation, increasing the durability of the materials [

2,

7,

8,

9]. In some cases, the appearance like the color or the texture can be enhanced. Functional properties like conductivity can be modified as well. Maintenance costs can be reduced by lowering repair frequency, increasing the sustainability of the materials.

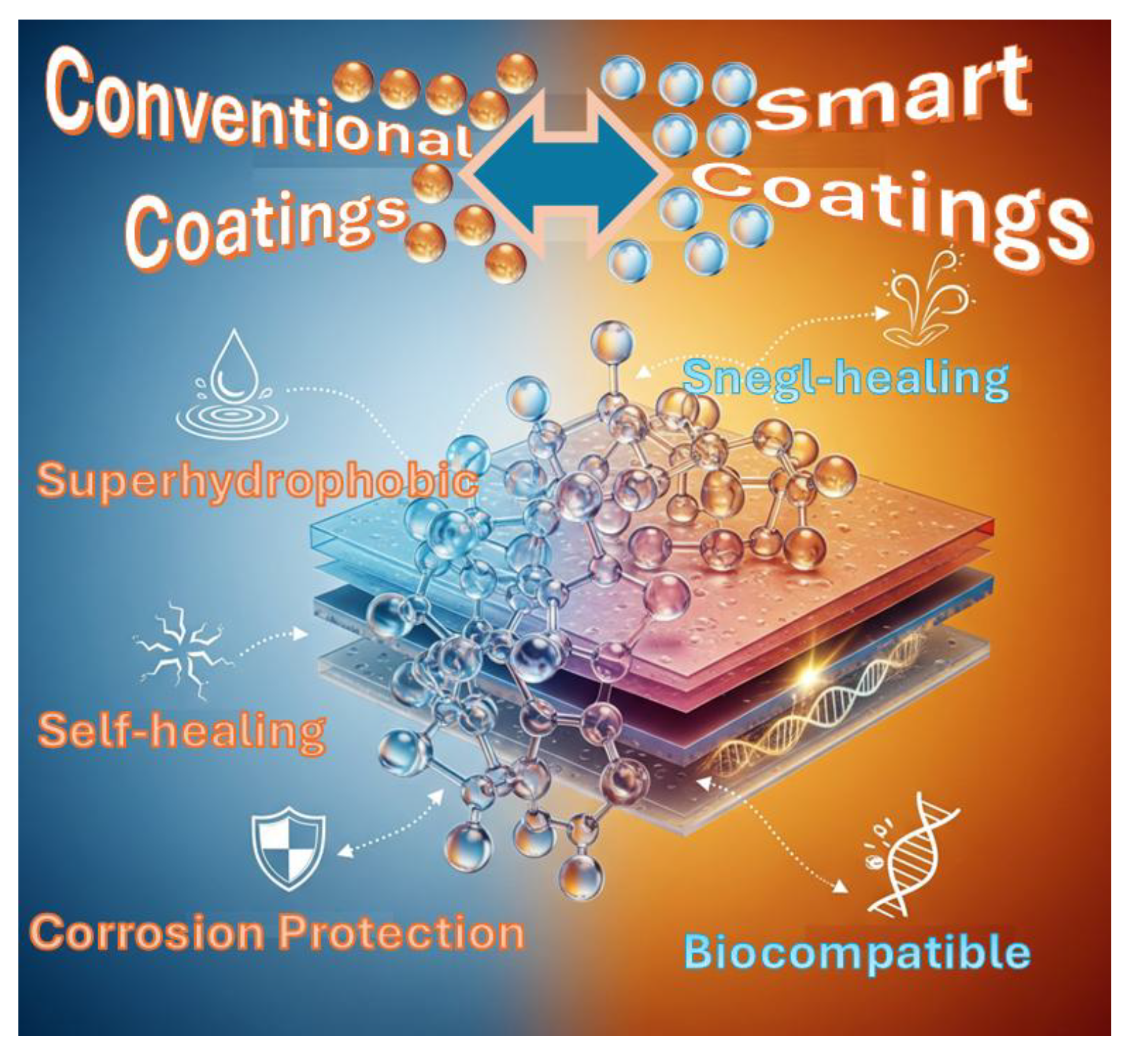

Surface coating materials, like mentioned before, are thin layers that can be applied to substrates to modify their properties, but without changing the bulk material [

1]. Nowadays, many industrial fields use them, like in aerospace, biomedical applications, electronics, energy, construction and others. Despite the good properties of the coating materials that were mentioned before, the conventional materials ace some limitations, like durability or environmental hazards. To solve this problem, smart coating materials can be fabricated, with better properties and less limitations [

10,

11]. This is crucial, due to the demand for new coatings with new and better levels of performance like the demand for sustainability, and green chemistry, or multifunctionality, allowing the coating material to have many properties. In this review, the principal categories of these materials are examined, with particular attention to their respective advantages and limitations, followed by a comparative evaluation of their performance in specific applications (

Figure 1).

2. Physicochemical Insights

The interface between a coating and its either substrate, bulk material or environment is governed by thermodynamic principles, such as surface energy, wetting, and adhesion. For instance, minimizing the Gibbs free energy at the interface ensures strong adhesion and stability. This involves tailoring the coating’s surface chemistry to match or complement the substrate’s properties, often quantified by contact angle measurements or surface tension. Techniques like self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) or functionalization can fine-tune these interactions.

Electrochemical phenomena are central to coatings for corrosion protection. Ion transport, dielectric permittivity, and the presence of nanoscale defects control electrolyte penetration and the establishment of localized electrochemical cells [

5]. The incorporation of inhibitors or functional nanofillers has been shown to alter transport properties, suppress anodic and cathodic reactions, and reduce corrosion currents [

6]. Modeling studies have further elucidated how diffusion coefficients and redox kinetics within the coating influence long-term protective performance [

7].

The formation and curing of coatings involve complex chemical reactions, including polymerization, cross-linking, and sol-gel processes. The kinetics of these reactions dictate the rate of film formation, directly influencing coating uniformity, thickness, and durability. In thermal or UV-cured coatings, curing follows Arrhenius-type kinetics, where the rate constant is expressed as:

Controlling activation energy (

) and curing temperature (

T) enables fine-tuning of the cross-linking density and final mechanical properties. Photoinitiated systems additionally depend on the efficiency of radical or cationic generation under irradiation, which can be tailored through initiator selection and wavelength matching [

12]. Understanding competitive pathways such as side reactions, incomplete curing, or degradation during processing is equally important. These can lead to defects including microcracking, poor adhesion, or delamination, ultimately compromising protective performance. Strategies such as catalyst optimization, staged curing, or incorporation of stabilizers are employed to minimize these undesired processes [

13].

The microstructure of a coating at the molecular and nanoscale—including its crystallinity, porosity, or how its phases separate—directly affects its larger-scale properties such as hardness, corrosion resistance, and water repellency (hydrophobicity). For example, adding nanoparticles like titanium dioxide can improve coating’s UV resistance, while creating layered structures with materials like graphene can enhance its overall function. To understand this relationship between the nanoscale structure and the coating’s performance, scientists use specialized tools like X-ray diffraction (XRD), atomic force microscopy (AFM), and molecular dynamics simulations [

14].

Thermodynamic and kinetic control also underpin the development of “smart” coatings. Stimuli-responsive polymers exploit conformational entropy changes to adjust permeability in response to external triggers (e.g., pH, temperature, or redox potential) [

10]. Similarly, sol–gel derived oxides rely on hydrolysis–condensation kinetics to control microstructure and porosity, thereby tuning barrier efficiency [

11]. Nanostructured additives can reduce interfacial free energy, promote passivation layer formation, or inhibit crack propagation through mechanisms analogous to toughening in composite materials [

8].

Taken together, these physicochemical insights establish guiding principles for next-generation coatings: (i) Molecular-level control of cohesive and adhesive forces to optimize integrity; (ii) Thermodynamic stability to withstand degradation under thermal fluctuations and aggressive chemical environments; (iii) Kinetic regulation of transport and self-healing responses; (iv) Interfacial design to regulate surface energy, electronic properties, and the formation of protective/passivating layers. By integrating molecular design, electrochemical understanding, and nanoscale engineering, physical chemistry provides a predictive framework for moving beyond empirical development toward rational design of multifunctional, adaptive, and sustainable surface coatings.

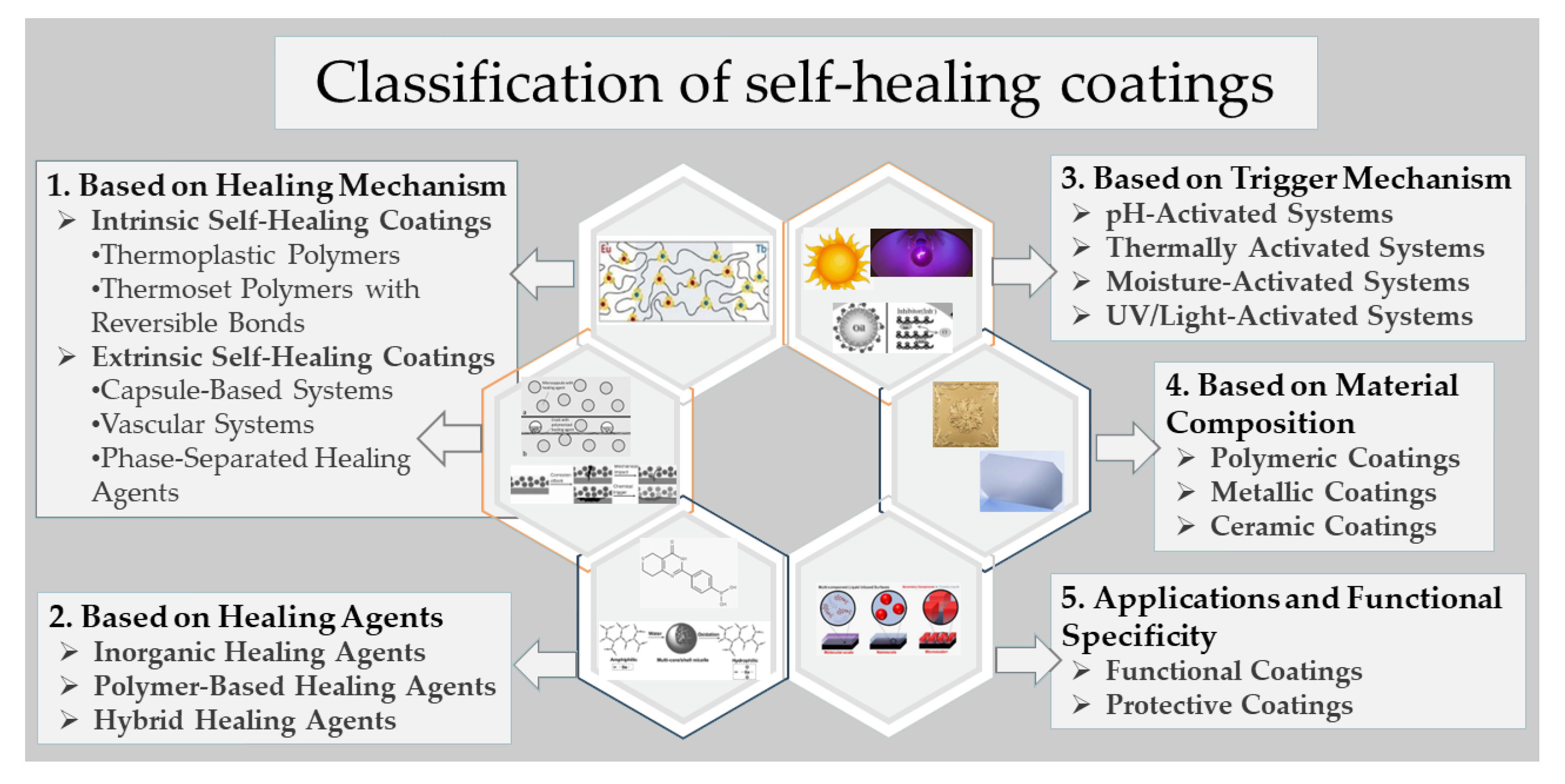

3. Categories of Coating Materials

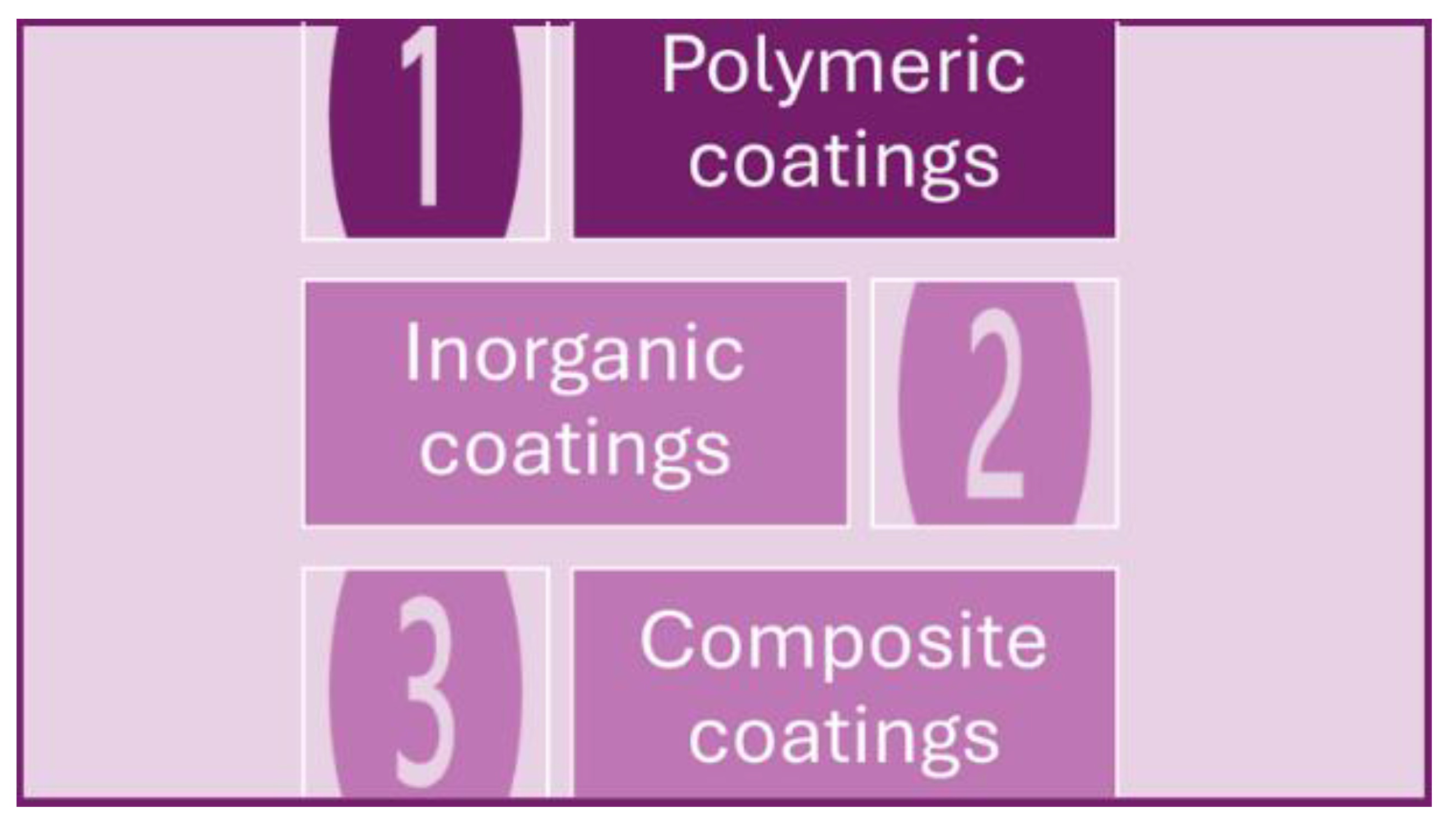

As mentioned before, the surface coating materials can be divided into 3 categories, based on the materials that are used (

Figure 2). There are the polymeric coatings, the inorganic coatings, and the composite coatings. The polymeric coatings are made from organic polymers, that provide flexibility and corrosion protection [

15]. The inorganic coatings can offer durability against harsh environments and excellent heat resistance [

16]. Finally, the composite coatings can provide many benefits like enhanced strength and tailored functional properties. In advanced applications, these categories are often integrated to exploit synergistic effects, such as improved electrochemical stability, superior adhesion to metallic substrates, and enhanced barrier properties. The selection of the appropriate coating system is governed by parameters including substrate–coating interfacial chemistry, microstructural characteristics, and long-term degradation mechanisms. Recent research efforts are increasingly focused on nanostructured and multifunctional coatings that can simultaneously provide corrosion resistance, self-healing capability, and environmental sustainability [

17].

3.1. Polymer Coatings

Polymeric coatings are flexible and tough, which helps them withstand mechanical stress and changes in temperature without cracking. Over time, advanced coatings have been developed with special additives and nanocomposites to improve their adhesion, chemical resistance, and overall durability. These coatings are also a popular choice for corrosion protection because they are effective, easy to apply, and affordable. They work primarily by creating a strong barrier that prevents corrosive substances like water, oxygen, and chloride ions from reaching the underlying material.

Polyurethane can be applied as a polymeric coating in sprayable self-healing paint systems, demonstrating outstanding healing capabilities. However, the monomers that are used are linked with aromatic or aliphatic disulfides of various molecular weights, which can reduce the healing efficiency of the coatings due to decreased molecular mobility and low surface energy [

18]. Capsules with a shell of poly (methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) and a core of ionic oligomeric polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) can also be used, in combination with an epoxy coating, for corrosion protection [

19]. A self-healing polyurethane–acrylic coating can also be employed to address structural defects arising from internal stresses during curing.

Epoxy coatings can be used for anti-corrosive protection, but their brittle nature, the propagation of microcracks, and their limited self-healing capacity present a challenge [

20]. A synergistic strategy can be employed that combines active solvents (1,4-butanediol diglyceryl ether), hydrogen bonding, and flexible polyurethane (PU) segments, with the aim of developing an advanced self-healing hybrid resin [

20]. Chitosan can be used as a shell material with an oil core to create self-healing and antibacterial microcapsules for wood coatings, significantly improving the coating’s performance by 2% [

21]. Lastly, a smart water-soluble coating can be employed, featuring photochemical self-healing and anticorrosive properties, using plant-acid-doped polyaniline (PANI), which functions both as a photothermal conversion material and as a green anticorrosive filler [

22].

3.2. Inorganic Coatings

Inorganic coatings, including oxides, silicates, nitrides, and phosphates, are favored for their durability in harsh conditions. They offer exceptional hardness, thermal stability, and chemical resistance, which is the reason they are important for high-temperature and marine environments. These coatings work by forming a dense, strong layer that acts as a powerful barrier against corrosion, oxidation, and wear. Recent advances in technologies like nanostructure and sol–gel fabrication have allowed for the creation of even better coatings with enhanced adhesion and multiple protective functions.

A ceramic coating with chemically bonded phosphate (CBxPA) can be prepared via a two-component spray, exhibiting both corrosion resistance and self-healing capability through water activation [

23]. Liquid silicone resin can be used for crack self-healing in a ceramic matrix, which has significant applications in high-temperature components such as turbine blades in aero engines [

16].

Zinc phosphate also be used as a coating with self-healing properties, being a safe and environmentally friendly additive capable of covering steel substrates [

24,

25,

26]. Additionally, magnesium phosphate cement (MPC) can be used as a green coating material due to its dense structure and excellent adhesion. However, its naturally hydrophilic nature and poor water resistance make it susceptible to penetration by water containing harmful ions, thereby limiting its use as a coating material [

27].

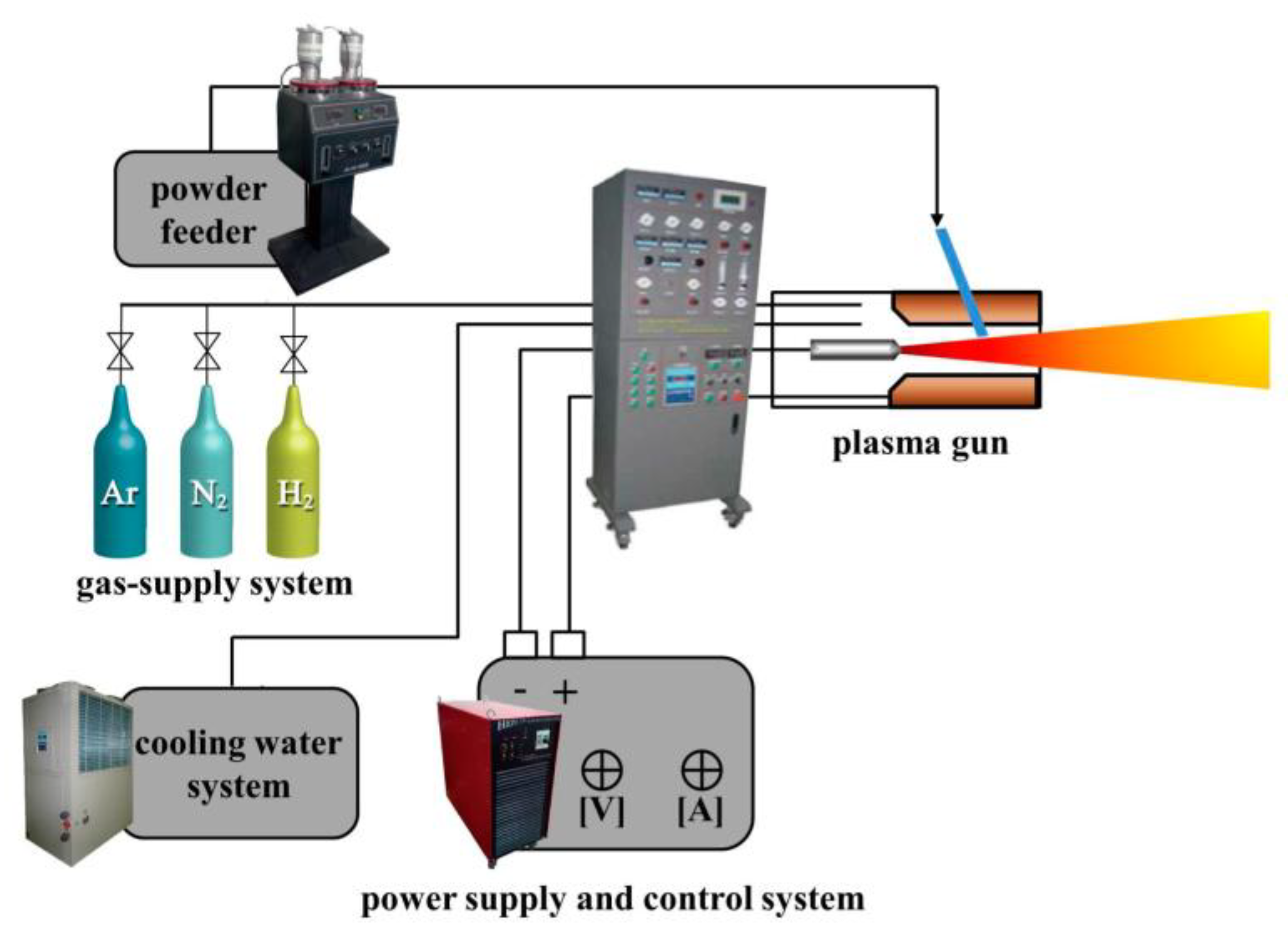

Some coating deposition techniques include Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD), where the material is vaporized and deposited onto a surface to form a thin coating; Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD), which involves a chemical reaction of gases on the substrate resulting in the formation of a solid material; and thermal spraying, which entails melting or heating powdered material and propelling it at high velocity onto a surface.

3.3. Composite Coatings

Composite hybrid coatings can also be employed. Composite coatings blend organic and inorganic components to create a highly effective protective layer. By combining materials like polymers, ceramics, and nanoparticles, these coatings offer a mix of benefits, including mechanical strength, corrosion resistance, and specific functions like self-healing or water repellency. The versatility of their internal structure allows them to be customized for different applications, improving their ability to act as a barrier, resist wear, and adhere to various surfaces. Current research is concentrating on nanocomposite coatings, using advanced engineering to enhance their durability and provide multiple functions.

Phosphate ceramic coatings with chemical bonding (FCBPC) modified with organic–inorganic hybrid alumina nanoparticles (FAS-Al₂O₃) can be prepared. The FAS-Al₂O₃ can bond with AlPO₄ and act as a binder, filling the gaps between ceramic grains, increasing the coating’s cohesion and adhesion to the substrate, thereby limiting and/or extending the diffusion path of corrosive agents within the coating. This results in enhanced corrosion resistance [

17]. Organic–inorganic biomimetic double-walled microcapsules with benzotriazole and linseed oil as core materials can be used in the field of anticorrosive coatings [

28].

Other microcapsules that can be employed to promote self-healing in epoxy coatings include poly(urea-formaldehyde-melamine) microcapsules containing dehydrated castor oil (DCO) [

29] To enhance epoxy systems, BPPM nanosheets, which possess multiple active sites within the coating matrix, can be added [

30]. Finally, hybrid TiO₂/SiO₂ microcapsules can be employed, offering not only self-healing but also self-cleaning capabilities. TiO₂ serves as a photocatalyst, while SiO₂ functions as the shell, and linseed oil can be used as the core [

31]. All the above exhibit excellent anticorrosive performance, and the self-healing properties of the coatings employed were significantly enhanced. Furthermore, the composite microcapsules demonstrated desirable morphology, good thermal stability, and improved mechanical strength.

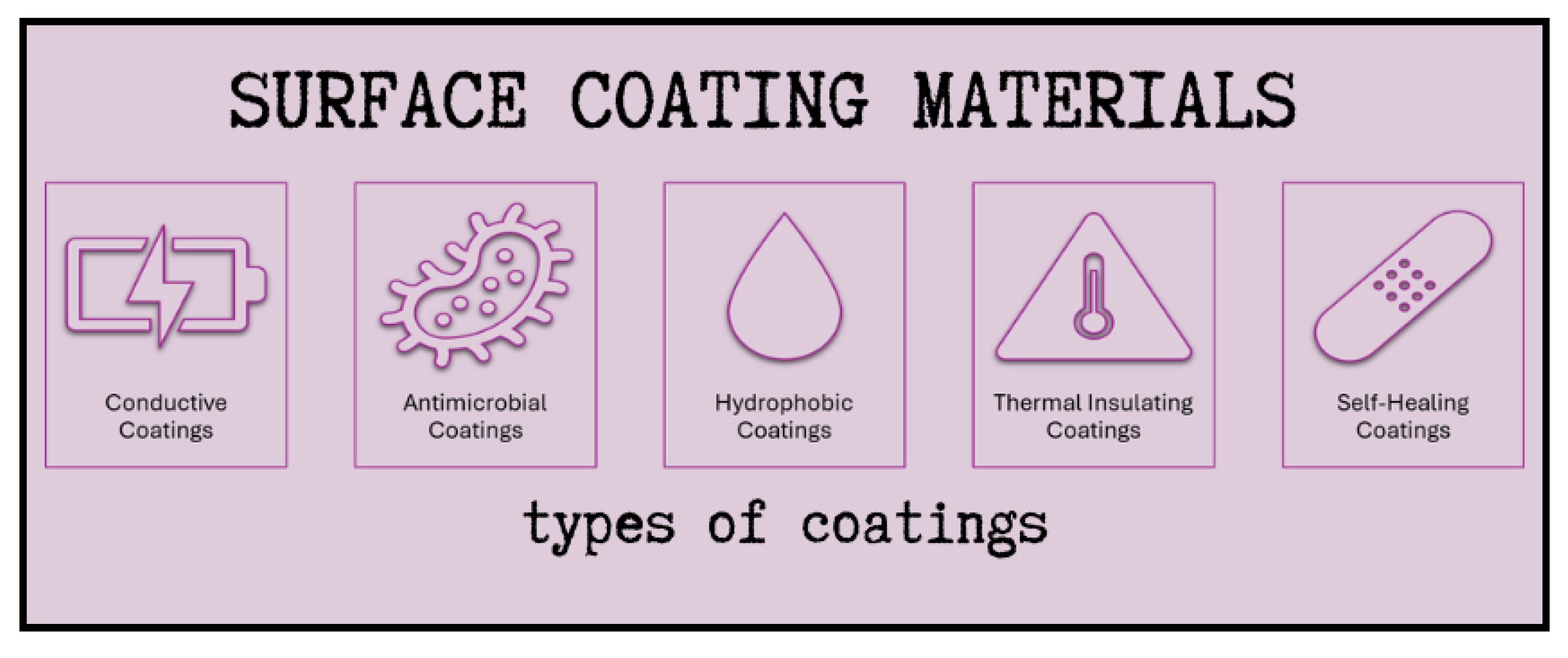

4. New Generation of Surface Coating Materials

The new generation of surface coating materials is designed to move beyond passive protection and deliver active, multifunctional performance. These advanced coatings often use nanomaterials, smart polymers, or materials inspired by nature to provide features like self-healing and adaptive barrier functionality that respond to their environment. Sustainability is a major focus, with a push toward eco-friendly formulas and a reduction in toxic chemicals. These innovations aim to extend the life of products, lower maintenance costs, and meet the high demands of future industrial and military applications. In this section, there will be an analysis of the new generation coating materials as well as their use in different applications (

Figure 3).

Thermal spraying coatings like Zn, Zn-15Al. Al and Al-5Mg can be combined with paints, elevating their anti-corrosion properties However in areas that have been damaged, the corrosion can start easier [

32]. Conventional materials like hydroxyapatite or Ti6Al4V can be used in biomedical applications, due to their biocompatibility. Their ideal density is something that should be studied, since the thinner layers exhibit better adhesion to substrates, but lack in resistance. The density should be appropriate, to balance mechanical strength and flexibility, preventing brittleness while maintaining adequate protection [

33]. For the same applications, amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP), or a non-crystalline CaP compound can be used, with the downside that they might degrade quickly [

34,

35].

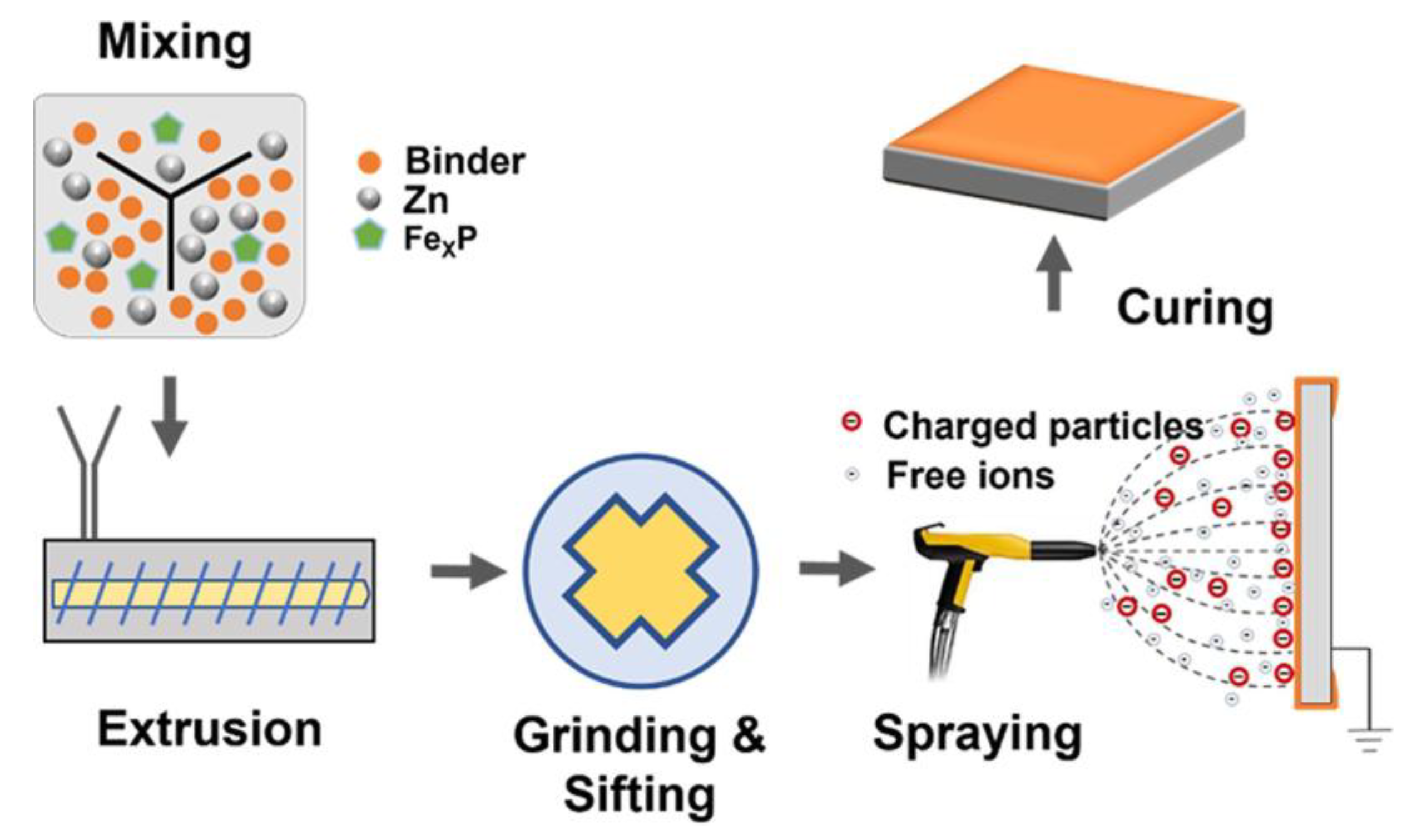

Zinc-rich polyester powder coatings with iron phosphate can be used as protective coatings against corrosion, even though they have several disadvantages such as their toxicity and environmental impact (

Figure 4) [

36]. In addition, traditional insulation materials can be utilized, which also have many disadvantages such as their limited thermal insulation properties and their insufficient durability [

37]. Such materials are polystyrene foam insulation boards, phenolic resin foam materials and rock wool insulation materials, that are susceptible to deformation and emission of toxic gases under high temperatures which poses safety risks. Furthermore, their insufficient moisture resistance and relatively short lifespan have emerged as significant challenges in their applications [

38].

Moreover, metal hydride coating technology is also often used in materials used for hydrogen storage, due to their large storage capacity. However, current coating technology faces challenges in terms of uniformity, stability, and scale-up [

39]. Finally, edible polysaccharide-based films and coatings have attracted attention in the food industry in recent years due to their green, environmentally friendly, and non-toxic food packaging materials, delaying the ripening of fruits and vegetables [

40]. However, they face limitations in antioxidant properties, antibacterial efficacy, and overall stability [

41,

42]

4.1. Self-Healing Coatings

For self-healing coatings, polymeric, composite and smart materials are often used. They can successfully repair cracks or damage without external intervention, and they can be activated by heat, light or chemical reaction. They can be used as additives in paints, for protective layers, electronics or aerospace.

Epoxy coatings are widely used for corrosion protection, especially for marine corrosion. However, the problems of brittleness, microcrack progression, and poor self-healing properties are yet to be addressed. So, a synergistic strategy by development of a high-performance self-healing hybrid resin is achieved by combining reactive diluents (1,4-butanediol diglyceryl ether), hydrogen bond interactions, and flexible polyurethane (PU) domains were created. The results indicated that the epoxy equivalent weight increased self-healing efficiency by facilitating chain mobility [

15].

There is also a new smart coating, with the ability to selectively release the corrosion inhibitors and repair the mechanical damage. Once the corrosion begins, the polymer releases the corrosion inhibitor and cerium, that later forms insoluble cerium oxides or cerium hydroxides on cathodic sites. So, this is also a new surface coating material that has self-healing, anti-corrosive properties, that is also pH responsive [

43].

Low-carbon steel surfaces can have improved corrosion resistance by modifying a commercial epoxy coating by adding microcapsules. These microcapsules can be composed of a poly (methyl methacrylate) shell and a core of ionic polydimethylsiloxane (PDMA) oligomers. Then, these microcapsules were incorporated into the matrix of the epoxy coating. The corrosion protection abilities were highly improved [

44].

Waterborne epoxy (EP) coatings are generally an excellent protection against corrosion. Traditional waterborne epoxy systems, however, face many challenges like weak interfacial bonding between functional fillers and the resin matrix, compounded by nanoparticle agglomeration during physical blending, reducing the long-term durability in harsh conditions. To solve this problem, incorporation of BPPM nanosheets can be done, enhancing the interfacial compatibility and the crosslinking density of the EP-based coating, through the phosphate and the amino groups on the nanosheets. The results indicated that this coating exhibits excellent self-healing properties, making it suitable for long-lasting applications [

45].

4.2. Thermal Insulating Coatings

Another type of coating is the one with thermal insulating properties. Aerogels, ceramics, or even composite types of materials can be used for these coatings. They usually have low thermal conductivity, and can be used in applications like construction work, aerospace, and energy efficient buildings. High-performance silica aerogel (SiO

2 aerogel) can be used as a thermal insulation coating, due to its excellent thermal insulation ability. When the mass ratio of hollow glass to SiO

2 aerogel microspheres is 1:1, the overall performance of the coating was the best with good thermal conductivity [

46]. Aerogels SiO

2 are porous materials with an internal network structure replete with gas and a solid appearance, with extremely low density and outstanding thermal insulation capabilities [

37].

Epoxy resin-based coatings can enhance their thermal insulation properties, with a prefabricated zirconium-doped silicone (ZAS) resin, and then a Si/Zr/P/N/Al multielement synergistic system for flame retardancy and thermal insulation was created. A comprehensive analysis that had been conducted on the impact of varying Zr and Si doping amounts on the flame-retardant and thermal insulation performance of the coatings indicated their excellent performances [

47]. A high-performance nanocomposite paint-based coating can be derived from naturally occurring and highly insulating layered vermiculite. Samples that were coated with vermiculite/epoxy nanocomposite paint indicated their resistance to thermal degradation. Ultra-thin vermiculite in nanocomposite coatings, can be fabricated and used due to their low thermal conductivity in thermal insulation systems [

48].

A new heat insulated coating combined antimony-doped tin oxide (ATO) and cesium tungsten bronze (Cs

0.33WO

3) was created and used in different glass samples, to enhance the cooling of the buildings. As a result, this coating can effectively reduce the solar heat gain, while the indoor daylighting illuminance was kept at a high level. This can save up to 9.5% of the building energy, if the coating is applied to south facing clear glass windows [

49]. Moreover, a transparent Al doped ZnO (AZO)/epoxy composite can be used as a glass thermal insulation coating, by incorporating AZO nanoparticles into a transparent epoxy matrix. Results showed the excellent thermal insulation property of this coating [

50].

4.3. Antimicrobial Coatings

Nanomaterials and polymers with cations can be used for antimicrobial coatings, due to their ability to inhibit or destroy microorganisms through contact. Hospitals, public spaces, biomedical devices or packaging, can benefit from these kinds of coatings [

51]. To prevent Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a derivative of hyaluronic acid (HA) and diethylenetriamine (DETA) was created. This selective derivative was used to set up a green fabrication procedure for HA-DETA capped silver nanoparticles with the aim to achieve a polymeric based coating with potential application in the treatment of medical devices associated infections. Results indicated the good antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of the HA-DETA/Ag nanocomposites [

52].

Moreover, a new biofunctionalized nanosilver (ICS-Ag), employing itaconyl-chondroitin sulfate nanogel (ICSNG) as a synergistic reducing and stabilizing agent was created, to effectively eradicate microbial infections and biofilms formation. This can be used for medical devices, since they can be a place where dangerous microbes can grow. So, the nanogel can be used as an antimicrobial coating for medical devices, due to its excellent antibiotic and antifungal capacity, as well as its good biocompatibility [

53].

For common-touch surfaces, an antimicrobial coating can be deposited on a generic adhesive film (wrap), and then this wrap can be attached to the touch surface. This can be done through two antimicrobial wraps with an active ingredient of cuprous oxide (Cu

2O), with two different binders, one based on polyurethane (PU) and the other based on polydopamine (PDA). These wraps can be removed and replaced as well, used for aesthetic or protective purposes [

54]. The antimicrobial coatings exhibit a delivery peak release of the antimicrobial agent at an early age, losing their antimicrobial activity over time. So, a novel geopolymer paint with long term antimicrobial activity was created, based on natural zeolite with silver and copper ions. This coating is very promising, due to its antimicrobial and antifungal properties, and can be applied against the spread of diseases and pathogens [

55].

4.4. Hydrophobic Coatings

Hydrophobic coatings can be used for self-cleaning surfaces, photovoltaics, or textiles, and they are fabricated from polymers. They have the ability to repel water and to reduce wetness and they are resistant to ice and dirt. Hybrid microcapsules TiO

2/SiO

2 with self-cleaning and self-repairing capabilities can be used to extend the service life of decorative coating by repairing micro-cracks with self-healing microcapsules, while giving them hydrophobic self-cleaning and photocatalytic self-cleaning functions [

31].

Magnesium phosphate cement (MPC) is a green coating material, with excellent adhesion and dense structure. However, it is naturally hydrophilic, making it susceptible to infiltration by water containing harmful ions, limiting its application as a coating material. So, polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) can be used, and new PDMS-modified MPC coatings can be created. These coatings are hydrophobic, due to the cross-linking reaction between PDMS and MPC, which lowers the surface energy through chemical modification [

27].

4.5. Conductive Coatings

Finally, the conductive coatings can be used in electronics, clean rooms and screens, due to their ability to disperse or remove static charges and to their high electrical conductivity. Graphene, carbon nanotubes and conductive polymers are some of the materials that can be used for these coatings.

A new type of intelligent water-borne coating was developed, with photothermal, self-healing and anti-corrosion properties. Phytic acid (PA) doped polyaniline was used as the photothermal conversion material and green anti-corrosion filler. The doping of PANI by PA improved the dispersibility of PANI in waterborne coatings. These coatings exhibit both self-healing and excellent anti-corrosion performance to elongate the service life of the coating [

22].

Waterborne polyurethane (WPU-SS)/ liquid metal (LM) composites have been discovered, that have high strength and excellent self-healing efficiency. Elastomers that exhibit these characteristics are rare. This enhanced mechanical, thermal, and electrical performance makes WPU-SS/LM composites promising for applications in conductive elastomers and dynamic switches [

56].

Table 1 tabulates the different types of surface coating materials.

5. Comparison of the Surface Coating Materials

Nowadays, there are many coating materials. There are criteria for the final decision of the surface coating material that will be used, choosing among the conventional or the smart ones, or the type of materials that will be used, like energy efficiency, lifespan, performance, cost or even the ease of the application. Furthermore, the specific needs of each industry or product often determine the most appropriate choice, as each application presents its own challenges. Therefore, the process of selecting surface coating material requires a combination of technical performance, cost-effectiveness and long-term sustainability.

5.1. Coating Comparison

In terms of cost, low-cost materials are more ideal for mass applications, as they are economical solutions in industry, whereas high-cost materials are used in applications that high precision and performance are necessary. Surface coating materials of high performance and durability like nanomaterials or microcapsules are used for advanced applications, and smart coatings (

Figure 5) [

63,

64,

65,

66,

67]. Almost every material is applied by coating or spraying while some function as additives in polymeric matrices [

58]. For anti-corrosion protection of metals, materials like BPPM nanosheets, biomimetic capsules, zinc phosphate and TiO₂/SiO₂ can be utilized due to their active protection and their multilayer defense. [

68,

69,

70].

For environmentally friendly coatings, chitosan or polyaniline with phytic acid and MPC can be used, since they are not toxic. Microcapsules PMMA/PDMS, DCO and biomimic microcapsules have self-healing properties, due to their active recovery of their functionality[

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78]. Moreover, for surface coatings on building materials, due to their compatibility with the mortars, MPC or zinc phosphate can be utilized, to improve the lifespan of substrates [

79]. Finally, high-performance multifunctional coatings can be obtained, due to the combination of anti-corrosion mechanical and thermal properties. Such coatings can be either hybrid capsules TiO₂/SiO₂, FCBPC with με FAS-Al₂O₃ or nanosheets BPPM [

30,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84]. In

Table 2, there is the comparison between some of the materials that were mentioned in this review paper.

5.2. Conventional and Smart Coatings

Metallic coatings are simple, effective, and successfully limit contact between metals or alloys and corrosive media. However, the degradation of the coatings allows corrosive agents to penetrate the surface of underlying metals and alloys causing material failures due to corrosion, such as cracks and delamination at the interface area [

85,

86,

87]. Thus, smart coatings have been developed that can detect invisible microscopic corrosion from below and may even have self-repairing capabilities [

62]. Over time, coatings inevitably fail. On aircraft, organic coatings will degrade or be damaged during use, particularly in marine environments with high salinity, temperature and humidity [

88].

Furthermore, conventional protective coatings are an easy solution for preventing corrosion on metals, [

89,

90,

91] but as mentioned before, these coatings can be damaged due to mechanical damage [

92]. Thus, smart anti-corrosion coatings were created to solve this problem, which provide for the early diagnosis of corrosion before it has time to form (

Figure 6) [

93,

94,

95]. Smart sensing coatings have a limited lifespan due to the use of fluorescent compounds, which also have a limited lifespan. This increases the cost, as the rate of renewal of these compounds in the coatings increases. This means that coatings with a high lifetime must be found for long-term applications [

62].

Conventional coatings also most often break easily and microcracks are created, which are easily corrected with smart coatings with self-healing properties. This is easily done by incorporating factors that enhance this property [

96]. Finally, most damaged coatings require replacement, which is often difficult and expensive. Therefore, smart coatings with self-healing properties are essential [

97].

Table 3 tabulates the characteristics between conventional and new smart materials, baes on criteria like cost, lifespan, environmental impact, energy efficiency, the ease of the application and finally the performance.

Based on

Table 3, it may be remarked that smart surface coating materials exhibit many advantages and innovations compared to conventional ones, especially in anti-corrosion protection. Their performance is excellent, since they have the ability to detect corrosion in early stages. At the same time, they incorporate self-healing properties, thus extending their functional duration. The cost is initially higher compared to conventional materials but is ultimately offset by the reduced need for maintenance and replacement that conventional coatings require. This also helps with the environmental impact of these materials in the long term, due to their increased durability and thus the reduction of waste. Finally, their rapid response to environmental changes makes them the best choice in terms of sustainability and reliability, in critical applications such as aeronautics but also in applications in marine environments.

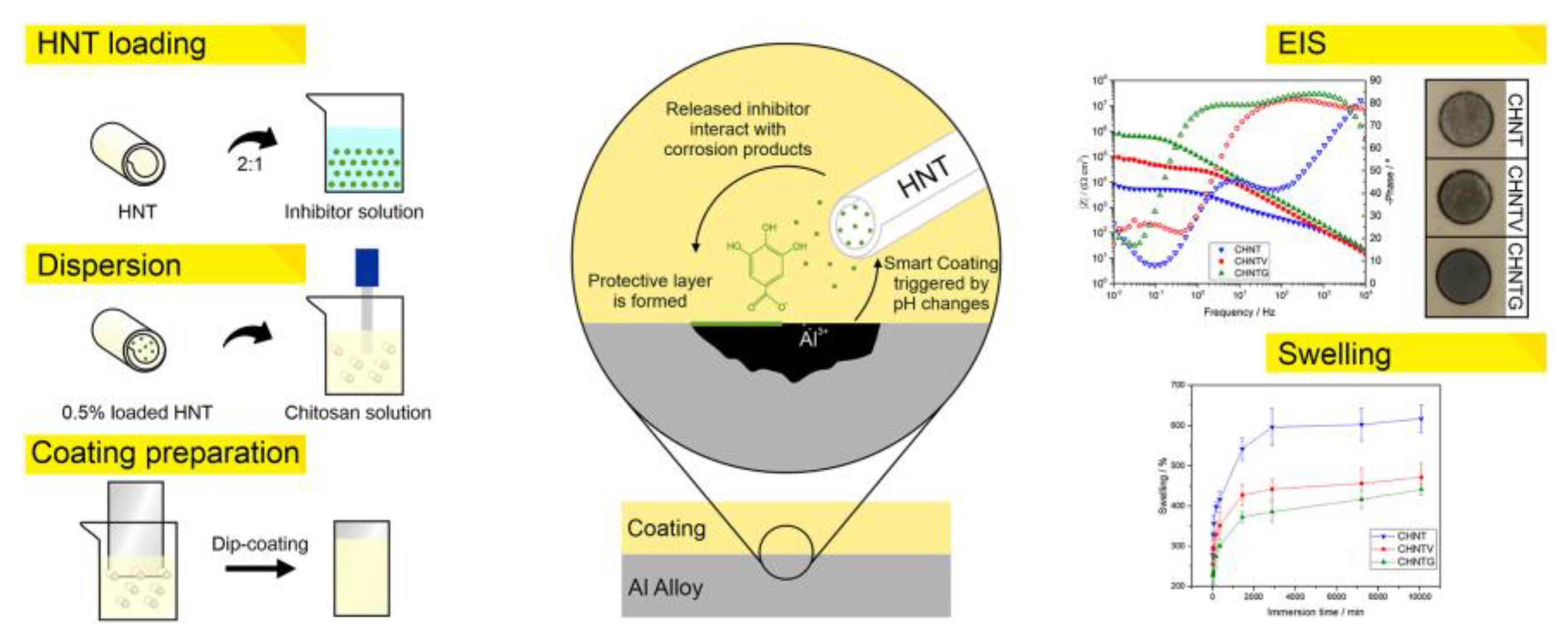

6. Technical Specifications

These surface coating materials should have certain characteristics to be used in applications. First, the microcapsules should cover the healing agent and be compatible with the coating matrix. Also, they should be stable under different environments, and they should respond to changes of stimuli. This is happening to prevent the repair agent from running away [

98]. They should have the ability to respond to stimuli, as the self-healing agent can be released depending on changes in environmental conditions, such as pH [

99,

100,

101] or changes like mechanical failure [

102].

When it comes to coatings for anti-corrosion protection, it is important to use sustainable and non-toxic materials. These materials help reduce environmental impact while maintaining effective protection of metals. Additionally, advances in nanotechnology and hybrid composites allow for enhanced durability and multifunctional performance in harsh environments (

Figure 7) [

71].

Photochromic materials are smart materials that change color when exposed to UV radiation, finding applications in lenses, plastics, and fabrics. They possess important properties such as fast response times, excellent reversibility, and the ability to undergo multiple cycles without significant degradation. These features make them highly versatile for protective coatings, adaptive textiles, and optical devices [

103]. In addition, smart coating materials should have small size and strong photoinduction ability, to be suitable for building blocks for complex optical tools [

104]. Other important properties of these materials include their ability to self-repair damage and cracks, as well as respond to environmental changes, which further enhances the effectiveness of their protective functions [

61].

Coating materials with self-healing properties should combine high flexibility with excellent adhesion to the substrate to ensure both durability and effective protection. Additionally, these coatings must be resistant to environmental factors such as moisture, temperature fluctuations, and chemical exposure. Their ability to maintain structural integrity under stress ensures long-term performance and minimizes maintenance requirements [

105]. Microcapsule materials need to have chemical and mechanical resistance, sufficient loading capacity, an impermeable shell wall to prevent leakage of the incorporated substance, the ability to detect corrosion, and the ability to provide sustained release of the active substance when needed, as mentioned before [

106].

7. Challenges to be Faced

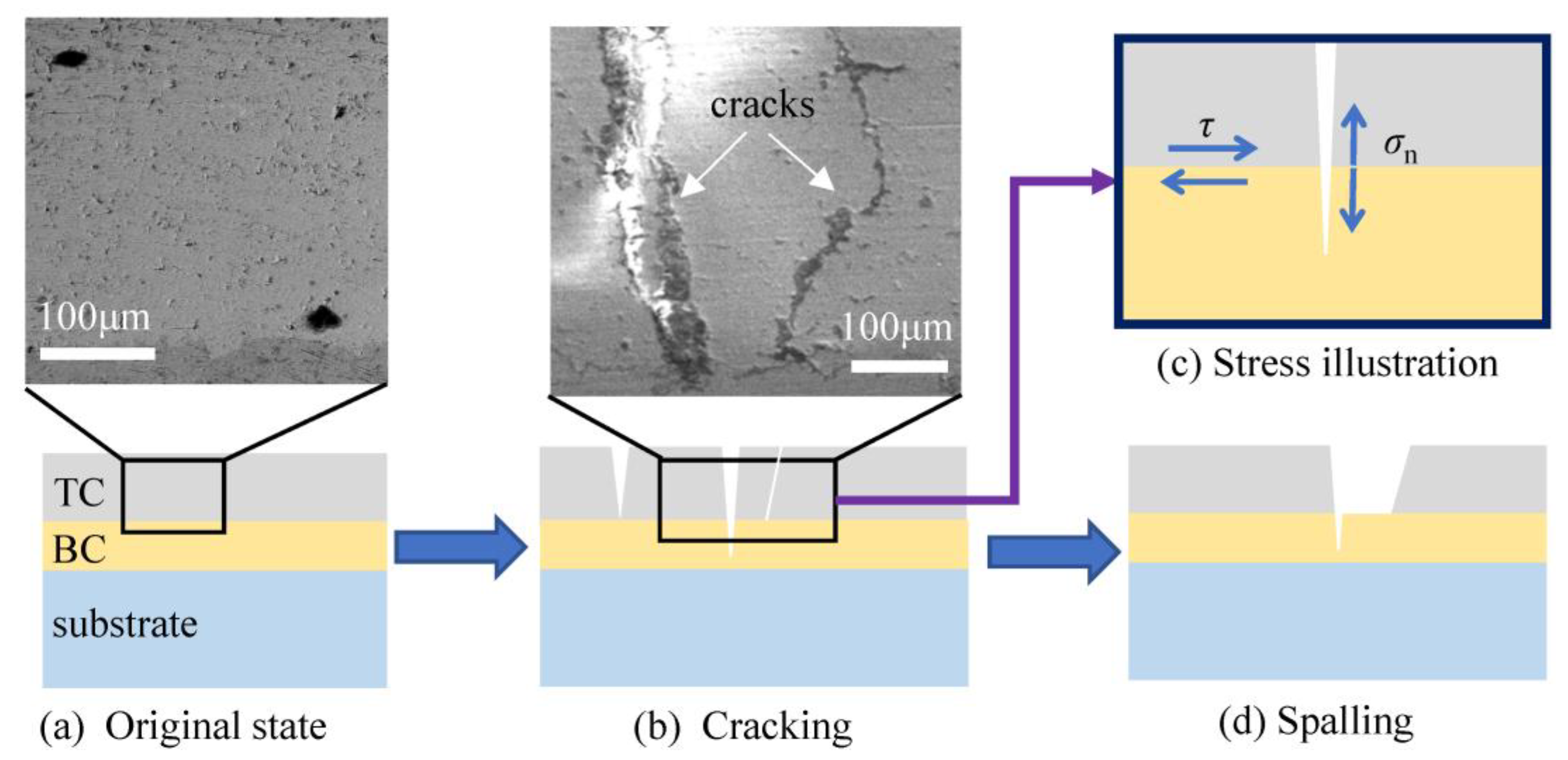

7.1. Durability and Wear Resistance Issues

The surface coating materials often face problems with long term and chemical stability. First of all, the repeated contact with abrasive surfaces or particulate matter gradually weakens the coating. Even strong coatings can be prone to micro-scale wear, lowering the after all efficiency and functional performance [

3]. Also, the protection can be compromised due to cracks. Ceramics and other brittle coatings may be damaged, even if they ae highly resistant. Some other times, repeated impacts lead to degradation that is not noticeable, until the catastrophic failure occurs [

107].

Moreover, high or low temperatures may affect the substrate, making it expand, and this generates stress. This thermal fatigue can cause cracking, particularly if the coating has elastic modulus (

Figure 8) [

108]. High-temperature coatings used in applications like turbines, must balance thermal stability with mechanical compliance.

Polymeric bonds might break down after exposure to UV radiation leading to surface cracking. If exposure is prolonged, then the hardness reduces, and so does the resistance in outdoor applications [

110]. Acidic or alkaline environments can erode the protective coatings as well, especially the polymeric layers. Also, salt, humidity and industrial chemicals accelerate the wear [

111]. The porosity, microcracks and the voids in coatings are also weak points, making the coating prone to cracks, accelerating the total failure of the coating. Poor adhesion between the coating and the substrate may lead to failure under stress as well [

112].

7.2. Environmental and Health Hazards

Most of the time, toxicity may come from the solvents, or the heavy metals in traditional coatings. Many conventional coatings rely on volatile organic compounds (VOCs) for applications. VOCs evaporate into the atmosphere, and this can cause air pollution [

113]. Chronic exposure can be catastrophic, causing respiratory problems. Coatings often contain lead, chromium, cadmium and other heavy metals, that are really toxic to humans and animals. Leaching can contaminate the water and food chains [

114].

Epoxy resins and other curing agents can also be toxic, causing allergies or asthma. Moreover, many coating compounds are non-biodegradable, and residual from spraying, wash or even discarded coated materials persist in soil and water, making the contamination worse [

115]. Spray and brush applications expose workers to airborne chemicals and dust. Long-term effects like lung disease are very common. Certain chemical coatings and VOCs release greenhouse gases during production. This can cause environmental problems. Studies should be heading towards a more bio-based approach of coating [

116].

7.3. Cost and Scalability Constraints

Surface coating materials are expensive, due to the precision and the specific materials that are needed. Advanced coating materials, like nanocomposites or special polymers, often require expensive raw materials [

117]. If there is a need for rare metals, nanoparticles or functional additives, the production cost increases significantly.

Sometimes, the techniques that are used are expensive, like CVD, thermal spraying, or plasma-assisted deposition consume large amounts of energy [

118]. Moreover, high temperature, vacuum or other conditions add to the general cost, as well as specialized deposition equipment like spray systems, vacuum chambers and their maintenance expenses [

119]. Skilled operators are often required, for precise control over the coating thickness and uniformity, and trained personnel are also required. Eco-friendly alternatives must be used, to replace the hazardous ones, and they are more expensive than the regulars (

Figure 9) [

120].

7.4. Adhesion and Compatibility Challenges

Another challenge that surfaces coating materials face is the poor bonding with certain substrates or multi-material interfaces. Firstly, differences in chemical composition between the substrate and coating material can lead to poor bonding making the coating prone on breaking [

121] Contamination or hydrophobic surfaces often reduce the adhesion. Smooth surfaces may prevent the mechanical interlocking, and this can also weaken the adhesion. Stress can be caused by excessive roughness, promoting the coating delamination [

122].

Unfortunately, some polymers or composites chemically react poorly with metals or ceramics, and this incompatibility can result in micro-cracks and even interfacial separation. Adsorbed water and humidity can interfere with the interface. UV light or exposure to aggressive chemicals can degrade the coating, as mentioned before [

123].

The thickness of the coating is very important. Very thin coatings may fail to cover imperfections, reducing adhesion, but extreme thick coatings can accumulate internal stress that compromises the general stability [

124]. Mechanical stress like vibration, bending or abrasion can limit the service life of the coating. Low flexibility coatings may crack under mechanical load. This is something that can happen over time as well, since the long-term environmental exposure can lead the coating to break down [

125].

7.5. Aesthetic Longevity

Finally, the coatings face some problems related to the aesthetic longevity, like color fading or surface roughening over time. Aesthetic longevity is very important in terms of surface coatings, since most of the time is the outer layer of the bulk material [

126]. Especially in paints and other applications of this kind, this is very crucial. UV radiation and sunlight exposure can affect the color stability, Environmental conditions or chemical exposure can cause the lack of gloss, that is very important in some applications [

127].

Chemical reactors sometimes change their color due to oxidation or hydrolysis. This is causing the coating material to fade. Moisture, acid rain, and others can accelerate this process, especially outdoors. Physical wear, including scratches, scuffs, and abrasion, can diminish the surface uniformity and overall visual appeal of coatings [

128,

129,

130]. Moreover, Environmental factors such as temperature fluctuations, humidity, salt exposure, and acid rain can degrade coating surfaces. Outdoor coatings are especially vulnerable to these stresses, while indoor coatings generally experience more controlled conditions [

131,

132,

133,

134].

To prevent the costings from these, UV absorbers, antioxidants, and nanoparticle additives can be added, to significantly enhance aesthetic longevity. These additives prevent pigment degradation, inhibit chemical reactions, and protect resin matrices from breakdown [

135,

136]. Innovations in additive technology have allowed coatings to maintain gloss, color, and surface smoothness for longer periods, even in harsh environments. Also, proper maintenance is important. This includes gentle cleaning and avoidance of harsh chemicals. Regular inspections and timely removal of contaminants such as dirt, mold, or corrosive substances prevent surface damage and fading.

8. Future Potential

These coatings are used due to their exceptional effectiveness in sectors such as aerospace, where the dissolution of the material brings economic risks, as well as safety hazards. Their market demand is also increasing with the prospect of revolutionizing other sectors as well, such as the automotive industry, electronics, medicine, the energy sector, and building materials [

137,

138]. There are also innovative approaches such as supramolecular valve technology, where supramolecular valves were introduced and investigated for more effective protection [

60,

65,

139,

140].

Future research can focus on the development of external nanocapsules embedded in metamorphic coatings. Research to evaluate and compare different self-healing metamorphic coatings is necessary, under real operating conditions. This could contribute to the development of specific metal substrates, thus leading to more effective coatings. Innovative self-healing ceramic coatings have also been developed through extrinsic or intrinsic approaches to crack healing [

57,

58,

141]. These studies suggest that the development of self-adhesive coatings on a commercial scale will revolutionize the coatings market in the coming years. More research should be conducted to optimize the parameters, depending on the type of coating, whether polymeric, inorganic or organic. This will achieve continuous self-healing and an extended lifespan of the coating [

61].

Furthermore, combined advantages of active corrosion protection and corrosion detection capability can be incorporated into the same coating. This allows rapid identification of the area of erosion as well as immediate self-healing through controlled release [

142,

143]. These coatings are called sensing-self-healing hybrid coatings and there is a great need for their development on a commercial scale. They could offer online monitoring in various industries such as aerospace, biomedical and chemical industries, and self-heal in areas where damage is detected, leading to longer lifespan, reduced maintenance costs and increased safety.

Although smart coatings are particularly important and have a promising future in protection against corrosion, pollution and wear, and while they act actively by detecting and healing damage, reducing the need for human intervention, they also have certain problems. Their design complexity, such as achieving the balance between self-healing effectiveness and protective barriers, is one of the challenges that must be addressed in the future [

144]. Self-reporting coatings have also attracted interest recently. They are smart coating materials that have the ability to detect and “report” the presence of wear or damage to the substrate (such as corrosion, cracks, mechanical stress) without the need for external inspection [

65,

145].

Color indicators directly visualize corrosion, while fluorescent indicators require excitation by UV radiation at a specific wavelength [

62,

146]. These coatings have been studied both with and without the use of nano-/microcapsules. Although direct mixing of the tracer molecules with resin can provide fluorescence detection, it carries the risk of undesirable effects, such as easy dissolution of the tracer and uncontrolled outflow of charged tracers when the coating is damaged [

147,

148]. Further research is needed to address issues such as the optimization and use of appropriate indicators for different environments as well as the stability of color signals.

Future studies can be conducted to develop corrosion detection coatings in opaque coating systems. Issues such as the lifespan, cost, and environmental impact of these innovative coatings with sensory characteristics also need to be examined more thoroughly and are a topic for future research [

149,

150]. Some of the coatings have the disadvantage of adding external capsules, which compromise the integrity of the coating and subsequently lead to loss of properties if the capsule content is not precisely optimized.

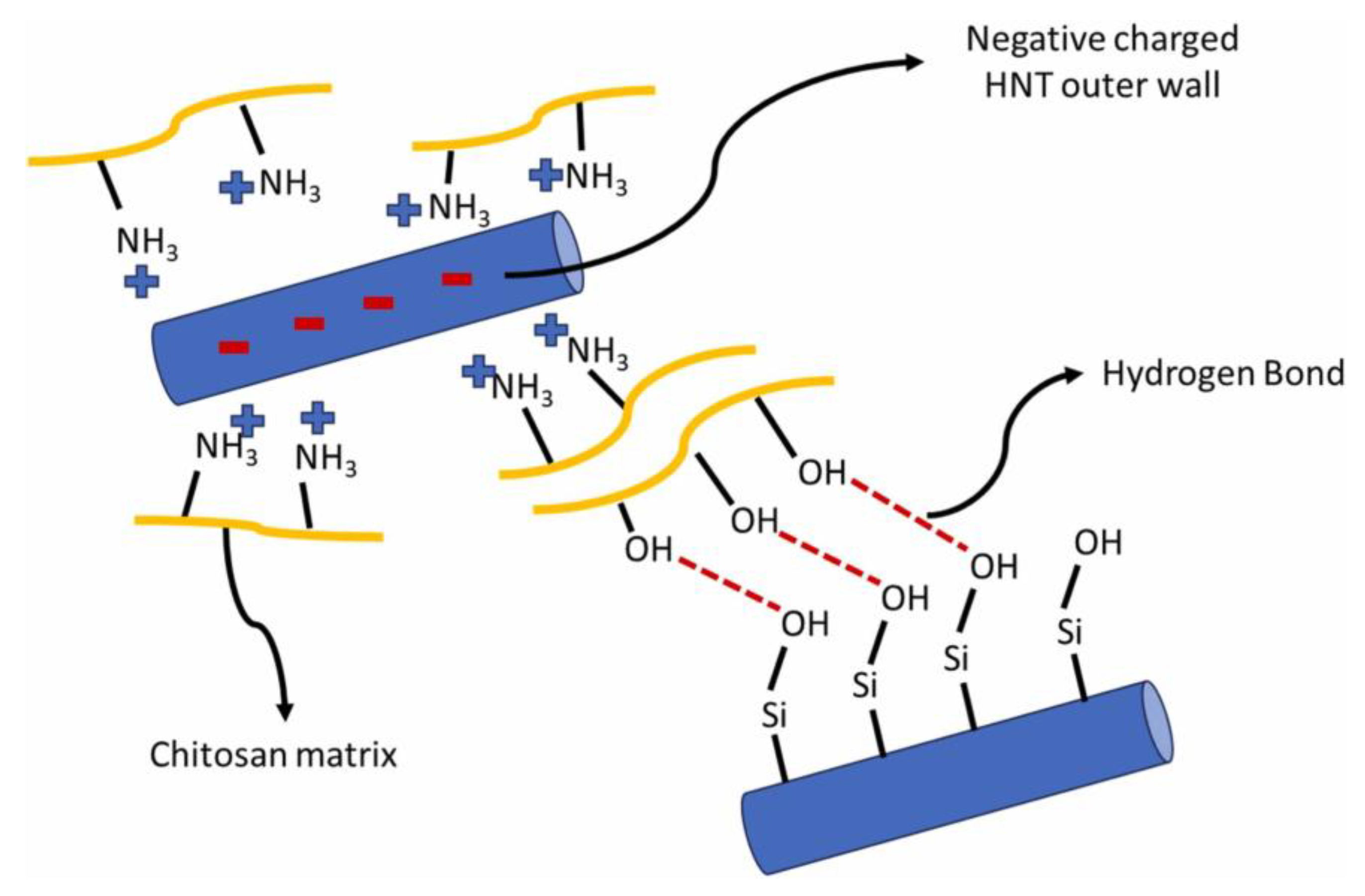

For the optimization of the microcapsules that are used for the coating matrixes, micro/nano carriers based on oxide nanoparticles, carbonaceous and two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials can be used [

67]. These advanced coatings can increase the electrochemical impedance values of steel. Moreover, biodegradable and non-toxic materials like chitosan and other biopolymers can be further studied. However, it cannot act on its own against corrosion with great effectiveness, so its functionality must be investigated through structural modifications, [

151,

152] (

Figure 10) formation of composite materials [

153,

154,

155] but also the development of smart coatings [

156,

157]. This will develop green coatings that are environmentally friendly and non-toxic.

Furthermore, a future potential application can be the monitoring of the condition of the coating and the repairing any damage that has occurred over time, in order to extend the maintenance cycle, reduce operating costs and extend the lifespan of the structure [

157] The construction of coating systems based on shape memory polymers (SMPs), to enhance longevity and safety can be studied. Organic coatings often exhibit problems and deterioration when exposed to corrosive chemicals and aqueous environments. Shape memory polymers can be a solution to this problem. These polymers can also be heat sensitive. This reduces the need to use large amounts of healing agents, thus maximizing the effectiveness of restoration in larger damages [

158].

9. Conclusions

In conclusion, smart coatings, in their ability not only to detect the first onset of corrosion but also to heal the evolving corrosion or crack, present a point of interest in modern research. Different types of coatings were discussed, such as polymeric, composite and inorganic, which belong to the category of self-healing coatings. The characteristics and properties of the coatings were also analyzed, and specific problems that need to be overcome were identified, while possible future applications were discussed. Various materials that can be used for smart coatings were mentioned, as well as application methods.

A comparative table was made based on cost, performance and environmental impact, where it was concluded that polymeric coatings are easier to apply, have good mechanical properties, and can be used for metal protection at low cost and in an environmentally friendly manner. Inorganic coatings have excellent durability and chemical stability and can be used as substrates in constructions and to replace heavy metals, while having the lowest cost. Finally, composite/hybrid coatings have smart functionality and higher performance than other categories, and find application in high technologies, where special conditions are needed, and are most suitable for use in applications where self-healing properties are needed.

The new coating materials have many advantages in their use. Self-healing coatings, with crack or damage repair properties, can be used in paints, aerospace, electronics and other applications. Thermal insulation coating can be applied in energy-efficient buildings and building materials, due to their thermal conductivity. Additionally, antimicrobial coatings with properties that inhibit or destroy microorganisms can be used in hospitals or medical applications, while hydrophobic coatings can repel water and be applied to self-cleaning surfaces and photovoltaics. Finally, conductive coatings can be used in electronics due to their electrical conductivity.

They have advantages in terms of their high performance and their smart properties such as the detection of early corrosion. Their cost is high, but as mentioned before, it is offset by the ultimately reduced need for maintenance. They are more environmentally friendly due to their increased durability, as this contributes to the reduction of waste, making them a more sustainable and reliable solution, compared to conventional coating materials. They also have properties of rapid response to environmental changes, ideal for special applications such as aeronautics. For the future, innovative coatings with multiple self-healing properties, visibly permeable, can be manufactured, which are based on hybrid inorganic-organic nanocomposites together with ionomers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P. and I.A.K.; methodology, M.P. and I.A.K.; validation, M.P. and I.A.K.; formal analysis, M.P.; investigation, M.P.; resources, V.B. and I.A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P., E.C.V., V.B. and I.A.K.; writing—review and editing, M.P., E.C.V., V.B. and I.A.K.; visualization, I.A.K.; supervision, I.A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Research Excellence Partnerships-SEA project: GoSmartSurf; project code: 10574. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used the artificial intelligence tool Gemini, version 2.0 flash, for the purposes of creating part of the background template of the graphical abstract and Figure 6. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 2D |

Two-dimensional |

| ACP |

Amorphous calcium phosphate |

| AFM |

Atomic force microscopy |

| AlPO₄ |

Aluminum phosphate |

| ATO |

Antimony-doped tin oxide |

| BC |

Bondcoat |

| CBxPA |

Ceramic coating with chemically bonded phosphate |

| CVD |

Chemical Vapor Deposition |

| DCO |

Dehydrated castor oil |

| DETA |

Diethylenetriamine |

| EP |

Waterborne epoxy |

| FAS-Al₂O₃ |

Phosphate ceramic coatings with alumina nanoparticles |

| FCBPC |

Phosphate ceramic coatings |

| HA |

Hyaluronic acid |

| ICS-Ag |

Biofunctionalized nanosilver |

| ICSNG |

Itaconyl-chondroitin sulfate nanogel |

| LM |

Liquid metal |

| MPC |

Magnesium phosphate cement |

| PA |

Phytic acid |

| PANI |

Polyaniline |

| PDA |

Polydopamine |

| PDMA |

Polydimethylsiloxane |

| PDMS |

Polydimethylsiloxane |

| PMMA |

Poly(methyl methacrylate) |

| PU |

Polyurethane |

| PVD |

(Physical Vapor Deposition) |

| SAMs |

Self-assembled monolayers |

| SEM |

Scanning electron microscopy |

| SiO2 aerogel |

Silica aerogel |

| SMPs |

Shape memory polymers |

| TC |

Topcoat |

| VOCs |

Volatile organic compounds |

| WPU-SS |

Waterborne polyurethane |

| XRD |

X-ray diffraction |

| ZAS |

Zirconium-doped silicone |

References

- Fotovvati, B.; Namdari, N.; Dehghanghadikolaei, A. On Coating Techniques for Surface Protection: A Review. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 2019, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, B.; Fathi, R.; Shi, H.; Wei, H. Advanced Corrosion Protection through Coatings and Surface Rebuilding. Coatings 2023, 13, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony Jose, S.; Lapierre, Z.; Williams, T.; Hope, C.; Jardin, T.; Rodriguez, R.; Menezes, P.L. Wear- and Corrosion-Resistant Coatings for Extreme Environments: Advances, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Coatings 2025, 15, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, M.; Mohd Ripin, Z.; Pasang, T.; Jiang, C.-P. Surface Engineering of Metals: Techniques, Characterizations and Applications. Metals (Basel) 2023, 13, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Xie, W.; Yang, Q.; Cao, Y.; Ren, J.; Almalki, A.S.A.; Xu, Y.; Cao, T.; Ibrahim, M.M.; Guo, Z. Self-Healing Anti-Corrosive Coating Using Graphene/Organic Cross-Linked Shell Isophorone Diisocyanate Microcapsules. React Funct Polym 2024, 202, 106000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhou, H.; Graham, M.; Smith, J.; Sheng, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Shchukina, E.; et al. Superior Anti-Corrosion and Self-Healing Bi-Functional Polymer Composite Coatings with Polydopamine Modified Mesoporous Silica/Graphene Oxide. J Mater Sci Technol 2021, 95, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony Jose, S.; Lapierre, Z.; Williams, T.; Hope, C.; Jardin, T.; Rodriguez, R.; Menezes, P.L. Wear- and Corrosion-Resistant Coatings for Extreme Environments: Advances, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Coatings 2025, 15, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Suhendri; Tajudin, A. N.; Suwarto, F.; Sudigdo, P.; Thom, N. Durability Evaluation of Heat-Reflective Coatings for Road Surfaces: A Systematic Review. Sustain Cities Soc 2024, 112, 105625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caramitu, A.R.; Ciobanu, R.C.; Lungu, M.V.; Lungulescu, E.-M.; Scheiner, C.M.; Aradoaei, M.; Bors, A.M.; Rus, T. Polymeric Protective Films as Anticorrosive Coatings—Environmental Evaluation. Polymers (Basel) 2024, 16, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Zarrouk, A.; Selvaraj, M.; Assiri, M.A.; Khanna, V.; Kumar, A.; Berdimurodov, E.; Eliboev, I. Nanomaterial-Based Smart Coatings for Sustainable Corrosion Protection in Harsh Marine Environments: Advances in Environmental Management and Durability. Inorg Chem Commun 2025, 176, 114280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, M.; Figueiredo, J.; Perina, F.C.; Abessa, D.M.S.; Martins, R. Environmental Behavior of Novel “Smart” Anti-Corrosion Nanomaterials in a Global Change Scenario. Environments 2025, 12, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsiadły, R.; Podemska, K.; Szymczak, A.M. Novel Visible Photoinitiators Systems for Free-Radical/Cationic Hybrid Photopolymerization. Dyes and Pigments 2011, 91, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusly, S.N.A.; Jamal, S.H.; Samsuri, A.; Mohd Noor, S.A.; Abdul Rahim, K.S. Stabilizer Selection and Formulation Strategies for Enhanced Stability of Single Base Nitrocellulose Propellants: A Review. Energetic Materials Frontiers 2024, 5, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadeesh, P.; Rangappa, S.M.; Siengchin, S. Advanced Characterization Techniques for Nanostructured Materials in Biomedical Applications. Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research 2024, 7, 122–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, K.; Zhang, C.; Deng, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Fang, D.; Ye, Z.; Wu, J. Tailoring an Epoxy-Polyurethane Self-Healing Coating for Anticorrosion Performance. Prog Org Coat 2025, 208, 109489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, M.; He, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yu, J.; Zhang, X.; Ren, Z. In-Situ Formation of SiC Nanowires for Self-Healing Ceramic Composites Using Liquid Silicone Resin. Composites Communications 2025, 56, 102336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, M.; Miao, X.; Bian, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y. Chemically Bonded Phosphate Ceramic Coatings with Self-Healing Capability for Corrosion Resistance. Surf Coat Technol 2023, 473, 129987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Jeon, H.; Kim, S.-M.; Lee, M.; Park, C.; Joo, Y.; Seo, J.; Oh, D.X.; Park, J. Self-Healable Spray Paint Coatings Based on Polyurethanes with Thermal Stability: Effects of Disulfides and Diisocyanates. Prog Org Coat 2025, 198, 108931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumezgane, O.; Suriano, R.; Fedel, M.; Tonelli, C.; Deflorian, F.; Turri, S. Self-Healing Epoxy Coatings with Microencapsulated Ionic PDMS Oligomers for Corrosion Protection Based on Supramolecular Acid-Base Interactions. Prog Org Coat 2022, 162, 106558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, K.; Zhang, C.; Deng, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Fang, D.; Ye, Z.; Wu, J. Tailoring an Epoxy-Polyurethane Self-Healing Coating for Anticorrosion Performance. Prog Org Coat 2025, 208, 109489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Liu, E. Fabrication of Chitosan-Encapsulated Microcapsules Containing Wood Wax Oil for Antibacterial Self-Healing Wood Coatings. Ind Crops Prod 2024, 222, 119438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lin, W.; Liu, R.; Luo, J. Photothermal Self-Healing and Anti-Corrosion Water-Borne Coatings Based on Phytic Acid-Doped Polyaniline. Prog Org Coat 2025, 204, 109267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Y.; Li, N.; Liu, Z.; Zuo, Y.; Li, Z.; Qian, S.; Zhang, C.; Yu, J. Bulk Self-Healing Behaviour Based on Water-Excited Chemically Bonded Phosphate Ceramic Coating and Its Anti-Corrosion Resistance. Appl Surf Sci 2025, 681, 161575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiro, M.; Collazo, A.; Izquierdo, M.; Nóvoa, X.R.; Pérez, C. Characterisation of Barrier Properties of Organic Paints: The Zinc Phosphate Effectiveness. Prog Org Coat 2003, 46, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, G.; Deyá, M.C.; Romagnoli, R.; Amo, B. del Three Generations of Inorganic Phosphates in Solvent and Water-Borne Paints: A Synergism Case. Appl Surf Sci 2005, 252, 1386–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Jia, C.; Meng, G.; Zhang, T.; Wang, F. The Role of a Zinc Phosphate Pigment in the Corrosion of Scratched Epoxy-Coated Steel. Corros Sci 2009, 51, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Khaskhoussi, A.; Hu, X.; Yang, J.; Shi, C. Surface Energy and Microstructural Analyses of Novel Highly Hydrophobic Magnesium Phosphate Cement Coatings. Cem Concr Compos 2025, 163, 106168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Guo, K.; Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Zhu, G. Biomimetic Mineralization in Double-Walled Microcapsules Making for Self-Healing Anticorrosive Coatings. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2025, 709, 136046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, F.G.; Bendinelli, E.V.; Aoki, I.V. Microcapsules Containing Dehydrated Castor Oil as Self-Healing Agent for Smart Anticorrosive Coatings. Prog Org Coat 2024, 197, 108863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xiao, G.; Wang, F.; Ma, X.; Liu, S.; Yan, H.; Gou, J.; Cao, J.; Wang, Y. Catalytic Crosslinking of Epoxy Coatings via BN-Based Hybrid Materials for Enhanced Corrosion Resistance, Self-Healing Capabilities and Mechanical Properties. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 515, 163653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Wang, X.; Zou, F.; Zhong, Y.; Guo, G. Preparation of TiO2 Hybrid SiO2 Wall Environment-Friendly Microcapsules Based on Interfacial Polycondensation: Realize the Integration of Self-Cleaning and Self-Healing Functions. Mater Today Commun 2024, 41, 111034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Kainuma, S.; Yang, H.; Kim, A.; Nishitani, T. Deterioration Mechanism of Overlaid Heavy-Duty Paint and Thermal Spray Coatings on Carbon Steel Plates in Marine Atmospheric Environments. Prog Org Coat 2025, 200, 109057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svehla, M.; Morberg, P.; Bruce, W.; Zicat, B.; Walsh, W.R. The Effect of Substrate Roughness and Hydroxyapatite Coating Thickness on Implant Shear Strength. J Arthroplasty 2002, 17, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masamoto, K.; Fujibayashi, S.; Yabutsuka, T.; Hiruta, T.; Otsuki, B.; Okuzu, Y.; Goto, K.; Shimizu, T.; Shimizu, Y.; Ishizaki, C.; et al. In Vivo and in Vitro Bioactivity of a “Precursor of Apatite” Treatment on Polyetheretherketone. Acta Biomater 2019, 91, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaoka, Y.; Fujibayashi, S.; Yabutsuka, T.; Yamane, Y.; Ishizaki, C.; Goto, K.; Otsuki, B.; Kawai, T.; Shimizu, T.; Okuzu, Y.; et al. Synergistic Effect of Sulfonation Followed by Precipitation of Amorphous Calcium Phosphate on the Bone-Bonding Strength of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polyetheretherketone. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Yang, M.; Zhu, W.; Tang, K.; Chen, J.; Joseph Noël, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, J. Zinc-Rich Polyester Powder Coatings with Iron Phosphide: Lower Zinc Content and Higher Corrosion Resistance. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2024, 133, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Duan, Y.; Chen, J.; Yao, S.; Peng, L.; Chen, W.; Menshutina, N.; Liu, M. A Review of Silica Aerogel Based Thermal Insulation Coatings: Preparation, Properties and Applications. Prog Org Coat 2025, 208, 109449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Sun, J.; Liew, K.M.; Zhu, G. Flammability and Safety Design of Thermal Insulation Materials Comprising PS Foams and Fire Barrier Materials. Mater Des 2016, 99, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Liu, C.; Yang, J.; Guo, J.; Huang, Q. A Review of Metal Hydride Coating Technology: Applications and Challenges in Energy Storage and Catalysis. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2025, 149, 150080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iñiguez-Moreno, M.; Ragazzo-Sánchez, J.A.; Barros-Castillo, J.C.; Sandoval-Contreras, T.; Calderón-Santoyo, M. Sodium Alginate Coatings Added with Meyerozyma Caribbica: Postharvest Biocontrol of Colletotrichum Gloeosporioides in Avocado (Persea Americana Mill. Cv. Hass). Postharvest Biol Technol 2020, 163, 111123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, H.E.; Abdel Aziz, M.S.; Alsehli, M. Carboxymethyl Cellulose/Sodium Alginate/Chitosan Biguanidine Hydrochloride Ternary System for Edible Coatings. Int J Biol Macromol 2019, 139, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Ren, J.; Xiao, X.; Cao, Y.; Zou, Y.; Qi, B.; Luo, X.; Liu, F. Recent Advances in Polysaccharide-Based Edible Films/Coatings for Food Preservation: Fabrication, Characterization, and Applications in Packaging. Carbohydr Polym 2025, 364, 123779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auepattana-Aumrung, K.; Crespy, D. Self-Healing and Anticorrosion Coatings Based on Responsive Polymers with Metal Coordination Bonds. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 452, 139055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumezgane, O.; Suriano, R.; Fedel, M.; Tonelli, C.; Deflorian, F.; Turri, S. Self-Healing Epoxy Coatings with Microencapsulated Ionic PDMS Oligomers for Corrosion Protection Based on Supramolecular Acid-Base Interactions. Prog Org Coat 2022, 162, 106558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xiao, G.; Wang, F.; Ma, X.; Liu, S.; Yan, H.; Gou, J.; Cao, J.; Wang, Y. Catalytic Crosslinking of Epoxy Coatings via BN-Based Hybrid Materials for Enhanced Corrosion Resistance, Self-Healing Capabilities and Mechanical Properties. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 515, 163653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Z.; Ma, S.; Wang, H.; Guan, Z.; Lian, B.; Qiu, Y.; Jiang, Y. Modulation of Thermal Insulation and Mechanical Property of Silica Aerogel Thermal Insulation Coatings. Coatings 2022, 12, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Liu, A.; He, Y.; Hu, Z.; Bian, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, M. Preparation and Performance Analysis of a Novel Zirconium-Doped Silicone Resin Modified Epoxy Resin-Based Intumescent Flame-Retardant and Thermal-Insulating Coating. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 520, 165996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethurajaperumal, A.; Manohar, A.; Banerjee, A.; Varrla, E.; Wang, H.; Ostrikov, K. (Ken) A Thermally Insulating Vermiculite Nanosheet–Epoxy Nanocomposite Paint as a Fire-Resistant Wood Coating. Nanoscale Adv 2021, 3, 4235–4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Lu, L.; Xu, X. Thermal and Daylighting Performance of Glass Window Using a Newly Developed Transparent Heat Insulated Coating. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 1080–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-Q.; Kang, Y.; Xiao, H.-M.; Mei, S.-G.; Zhang, G.-L.; Fu, S.-Y. Preparation and Characterization of Transparent Al Doped ZnO/Epoxy Composite as Thermal-Insulating Coating. Compos B Eng 2011, 42, 2176–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Silva, P.; Borges, J.; Sampaio, P. Recent Advances in Metal-Based Antimicrobial Coatings. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 2025, 344, 103590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martorana, A.; Pitarresi, G.; Palumbo, F.S.; Catania, V.; Schillaci, D.; Mauro, N.; Fiorica, C.; Giammona, G. Fabrication of Silver Nanoparticles by a Diethylene Triamine-Hyaluronic Acid Derivative and Use as Antibacterial Coating. Carbohydr Polym 2022, 295, 119861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, R.; Alharbi, N.M. Biosynthesized Silver Nanoparticles-Capped Chondroitin Sulfate Nanogel Targeting Microbial Infections and Biofilms for Biomedical Applications. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 253, 127080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadinasab, S.; Williams, M.D.; Falkinham, J.O.; Ducker, W.A. Facile Implementation of Antimicrobial Coatings through Adhesive Films (Wraps) Demonstrated with Cuprous Oxide Coatings. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolov, A.; Dobreva, L.; Danova, S.; Miteva-Staleva, J.; Krumova, E.; Rashev, V.; Vilhelmova-Ilieva, N.; Tsvetanova, L.; Barbov, B. Antimicrobial Geopolymer Paints Based on Modified Natural Zeolite. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2023, 19, e02642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhao, H.; Ji, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Wen, S.; Liu, J. High-Strength, Self-Healing Waterborne Polyurethane Elastomers with Enhanced Mechanical, Thermal, and Electrical Properties. Composites Communications 2024, 51, 102100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontiza, A.; Kartsonakis, I.A. Smart Composite Materials with Self-Healing Properties: A Review on Design and Applications. Polymers (Basel) 2024, 16, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartsonakis, I.A.; Kontiza, A.; Kanellopoulou, I.A. Advanced Micro/Nanocapsules for Self-Healing Coatings. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 8396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xiao, G.; Wang, F.; Ma, X.; Liu, S.; Yan, H.; Gou, J.; Cao, J.; Wang, Y. Catalytic Crosslinking of Epoxy Coatings via BN-Based Hybrid Materials for Enhanced Corrosion Resistance, Self-Healing Capabilities and Mechanical Properties. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 515, 163653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimyai, T.; Crespy, D.; Rohwerder, M. Corrosion-Responsive Self-Healing Coatings. Advanced Materials 2023, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saji, V.S. Smart Self-Healing and Self-Reporting Coatings – an Overview. Prog Org Coat 2025, 205, 109318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Wang, Y.; Gu, L.; Feng, Z.; Lei, B.; Zhu, L.; Guo, H.; Meng, G. Smart Sensing Coatings for Early Warning of Degradations: A Review. Prog Org Coat 2023, 177, 107418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartsonakis, I.A.; Kontiza, A.; Kanellopoulou, I.A. Advanced Micro/Nanocapsules for Self-Healing Coatings. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 8396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udoh, I.I.; Ekerenam, O.O.; Daniel, E.F.; Ikeuba, A.I.; Njoku, D.I.; Kolawole, S.K.; Etim, I.-I.N.; Emori, W.; Njoku, C.N.; Etim, I.P.; et al. Developments in Anticorrosive Organic Coatings Modulated by Nano/Microcontainers with Porous Matrices. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 2024, 330, 103209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, S.; Park, S.; Chelliah, R.; Yeon, S.-J.; Barathikannan, K.; Vijayalakshmi, S.; Jeong, Y.-J.; Rubab, M.; Oh, D.H. Emerging Trends in Smart Self-Healing Coatings: A Focus on Micro/Nanocontainer Technologies for Enhanced Corrosion Protection. Coatings 2024, 14, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Huang, N.; Yan, X. Effect of Composite Addition of Antibacterial/Photochromic/Self-Repairing Microcapsules on the Performance of Coatings for Medium-Density Fiberboard. Coatings 2023, 13, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, M.; Bi, H.; Dam-Johansen, K. Advanced Materials for Smart Protective Coatings: Unleashing the Potential of Metal/Covalent Organic Frameworks, 2D Nanomaterials and Carbonaceous Structures. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 2024, 323, 103055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, W.; Rao, J.; Zhang, Y. Progress in the Preparation and Applications of Microcapsules for Protective Coatings Against Corrosion. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simescu, F.; Idrissi, H. Effect of Zinc Phosphate Chemical Conversion Coating on Corrosion Behaviour of Mild Steel in Alkaline Medium: Protection of Rebars in Reinforced Concrete. Sci Technol Adv Mater 2008, 9, 045009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, X. Preparation and Corrosion Properties of TiO2-SiO2-Al2O3 Composite Coating on Q235 Carbon Steel. Coatings 2023, 13, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, L.; de Sousa Santos, F.; da Conceição, T.F. Sustainable Smart Coating of Chitosan, Halloysite Nanotubes and Phenolic Acids for Corrosion Protection of Al Alloy. Mater Chem Phys 2025, 345, 131240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Ruiz, A.; Dévora-Isiordia, G.; Sánchez-Duarte, R.; Villegas-Peralta, Y.; Orozco-Carmona, V.; Álvarez-Sánchez, J. Chitosan-Based Sustainable Coatings for Corrosion Inhibition of Aluminum in Seawater. Coatings 2023, 13, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umoren, S.A.; AlAhmary, A.A.; Gasem, Z.M.; Solomon, M.M. Evaluation of Chitosan and Carboxymethyl Cellulose as Ecofriendly Corrosion Inhibitors for Steel. Int J Biol Macromol 2018, 117, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Ruiz, A.A.; Sánchez-Duarte, R.G.; Orozco-Carmona, V.M.; Devora-Isiordia, G.E.; Villegas-Peralta, Y.; Álvarez-Sánchez, J. Chitosan and Its Derivatives as a Barrier Anti-Corrosive Coating of 304 Stainless Steel against Corrosion in 3.5% Sodium Chloride Solution. Coatings 2024, 14, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartsonakis, I.A.; Kontiza, A.; Kanellopoulou, I.A. Advanced Micro/Nanocapsules for Self-Healing Coatings. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 8396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolini, N.A.; Cordeiro Neto, A.G.; Pellanda, A.C.; Carvalho Jorge, A.R. de; Barros Soares, B. de; Floriano, J.B.; Berton, M.A.C.; Vijayan P, P.; Thomas, S. Evaluation of Corrosion Protection of Self-Healing Coatings Containing Tung and Copaiba Oil Microcapsules. Int J Polym Sci 2021, 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uko, L.; Elkady, M. Biohybrid Microcapsules Based on Electrosprayed CS-Immobilized NanoZrV for Self-Healing Epoxy Coating Development. RSC Adv 2024, 14, 18467–18477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neon Gan, S.; Shahabudin, N. Applications of Microcapsules in Self-Healing Polymeric Materials. In Microencapsulation - Processes, Technologies and Industrial Applications; IntechOpen, 2019.

- Dai, X.; Qian, J.; Qin, J.; Yue, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Jia, X. Preparation and Properties of Magnesium Phosphate Cement-Based Fire Retardant Coating for Steel. Materials 2022, 15, 4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, V.; Padmapreetha, R.; Chandrasekhar, S.B.; Murugan, K.; Johnson, R. Oxidation Resistant TiO2–SiO2 Coatings on Mild Steel by Sol–Gel. Surf Coat Technol 2019, 378, 125041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, N.; Basirun, W.J.; Mohammed Nor, A.; Johan, M.R. Super-Amphiphobic Coating System Incorporating Functionalized Nano-Al2O3 in Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) with Enhanced Corrosion Resistance. Coatings 2020, 10, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignesh, M.; Anbuchezhiyan, G.; Mamidi, V.K.; Vivek Anand, A. Enriching Mechanical, Wear, and Corrosion Behaviour of SiO2/TiO2 Reinforced Al 5754 Alloy Hybrid Composites. Mater Lett 2024, 361, 136106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Shen, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, E.; Zhang, J. Effect of Al2O3 on Microstructure and Corrosion Characteristics of Al/Al2O3 Composite Coatings Prepared by Cold Spraying. Metals (Basel) 2024, 14, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q.; Huang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xie, D.; Sheng, X. Black Phosphorus Nanosheets for Advanced Polymer Coatings and Films: Preparation, Stability and Applications. J Mater Sci Technol 2025, 216, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Wan, H.; Tu, X.; Li, W. A Better Understanding of Failure Process of Waterborne Coating/Metal Interface Evaluated by Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. Prog Org Coat 2020, 142, 105558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Song, D.; Li, X.; Zhang, D.; Gao, J.; Du, C. Failure Mechanisms of the Coating/Metal Interface in Waterborne Coatings: The Effect of Bonding. Materials 2017, 10, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhong, X.; Li, L.; Hu, J.; Peng, Z. Unmasking the Delamination Mechanisms of a Defective Coating under the Co-Existence of Alternating Stress and Corrosion. Prog Org Coat 2023, 180, 107560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funke, W. Blistering of Paint Films and Filiform Corrosion. Prog Org Coat 1981, 9, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, J.J.; Ferreira-Aparicio, P.; Chaparro, A.M. Anti-Corrosion Coating for Metal Surfaces Based on Superhydrophobic Electrosprayed Carbon Layers. Appl Mater Today 2018, 13, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, J.; Jin, Z.; Hou, P.; Zhao, H.; Wang, L. Synthesis of Graphene-Epoxy Nanocomposites with the Capability to Self-Heal Underwater for Materials Protection. Composites Communications 2019, 15, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Wang, P.-Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, B. Mangrove Inspired Anti-Corrosion Coatings. Coatings 2019, 9, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhoke, S.K.; Khanna, A.S. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) Study of Nano-Alumina Modified Alkyd Based Waterborne Coatings. Prog Org Coat 2012, 74, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Frankel, G.S. Corrosion-Sensing Behavior of an Acrylic-Based Coating System. Corrosion 1999, 55, 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkirskiy, V.; Keil, P.; Hintze-Bruening, H.; Leroux, F.; Vialat, P.; Lefèvre, G.; Ogle, K.; Volovitch, P. Factors Affecting MoO 4 2– Inhibitor Release from Zn 2 Al Based Layered Double Hydroxide and Their Implication in Protecting Hot Dip Galvanized Steel by Means of Organic Coatings. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2015, 7, 25180–25192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Fickert, J.; Landfester, K.; Crespy, D. Encapsulation of Self-Healing Agents in Polymer Nanocapsules. Small 2012, 8, 2954–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Han, H.; Yi, M.; Xu, Z.; Hui, H.; Wang, R.; Zhou, M. Overview of Smart Anti-Corrosion Coatings and Their Micro/Nanocontainer Gatekeepers. Mater Today Commun 2025, 42, 111316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Peng, F.; Liu, X. Protection of Magnesium Alloys: From Physical Barrier Coating to Smart Self-Healing Coating. J Alloys Compd 2021, 853, 157010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehra, S.; Mobin, M.; Aslam, R.; Parveen, M.; Aslam, A. Nanocontainer-Loaded Smart Functional Anticorrosion Coatings. In Smart Anticorrosive Materials; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 481–497.

- Taheri, N.; Sarabi, A.A.; Roshan, S. Investigation of Intelligent Protection and Corrosion Detection of Epoxy-Coated St-12 by Redox-Responsive Microcapsules Containing Dual-Functional 8-Hydroxyquinoline. Prog Org Coat 2022, 172, 107073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siva, T.; Kandhasamy, K.; Vaduganathan, K.; Sathiyanarayanan, S.; Ramadoss, A. Electrosynthesis of Silica Reservoir Incorporated Dual Stimuli Responsive Conducting Polymer-Based Self-Healing Coatings. Ind Eng Chem Res 2023, 62, 3942–3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]