Submitted:

13 September 2025

Posted:

17 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

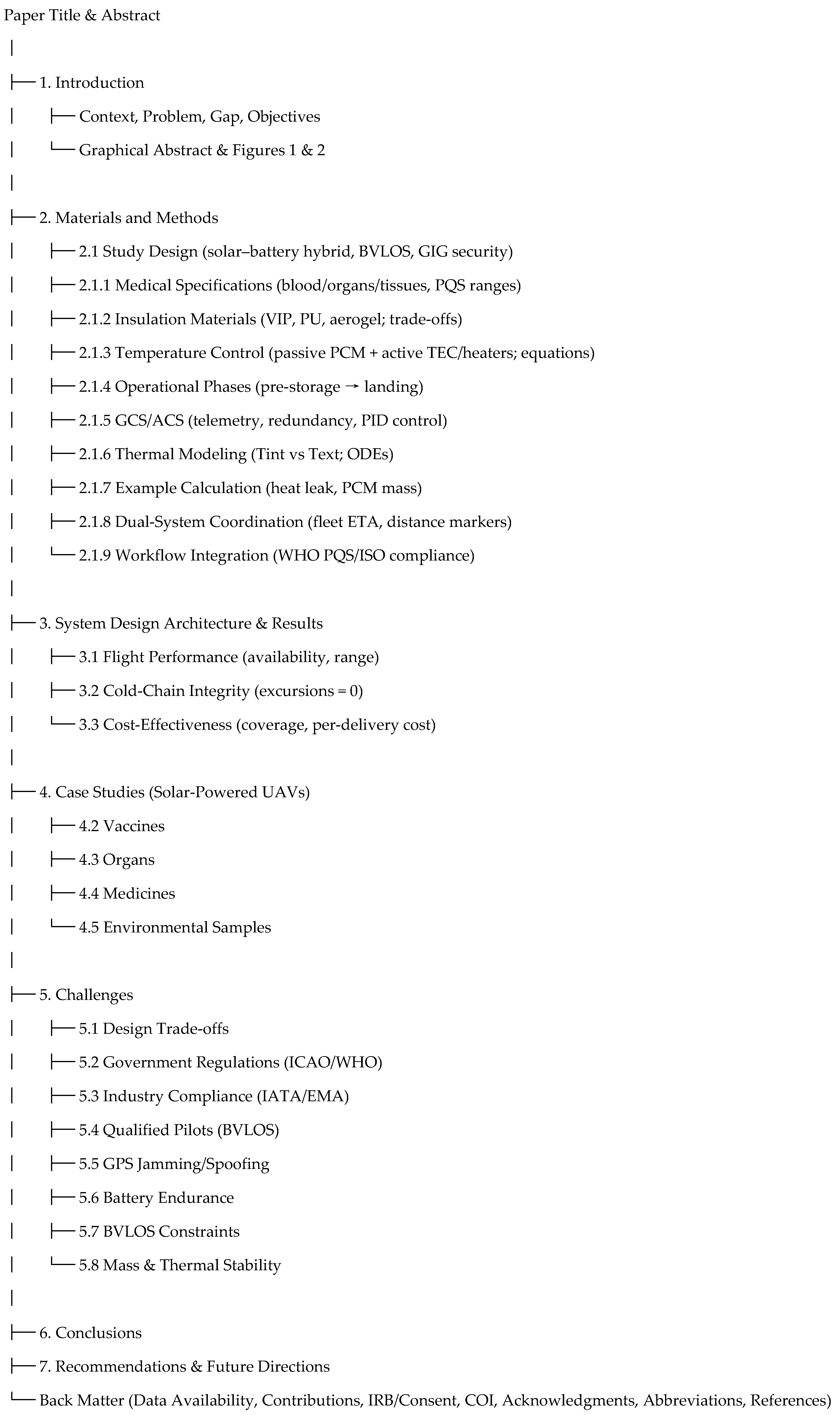

1. Introduction

1.1. Importance

1.2. Background

1.3. Problem Statement

1.4. Research Gap

1.5. Evidence

1.6. Local Context

1.7. Study Objectives

- 1.

-

Integrate Hybrid Solar-Battery PropulsionDevelop and test a propulsion system that combines solar energy harvesting with battery storage to significantly extend UAV endurance and minimize downtime between missions.

- 2.

-

Develop a Tiered UAV Fleet ArchitectureDesign a multi-tier fleet system capable of handling diverse payload capacities, ranging from small, lightweight vaccine packages to larger biologic shipments, while optimizing cost and operational efficiency.

- 3.

-

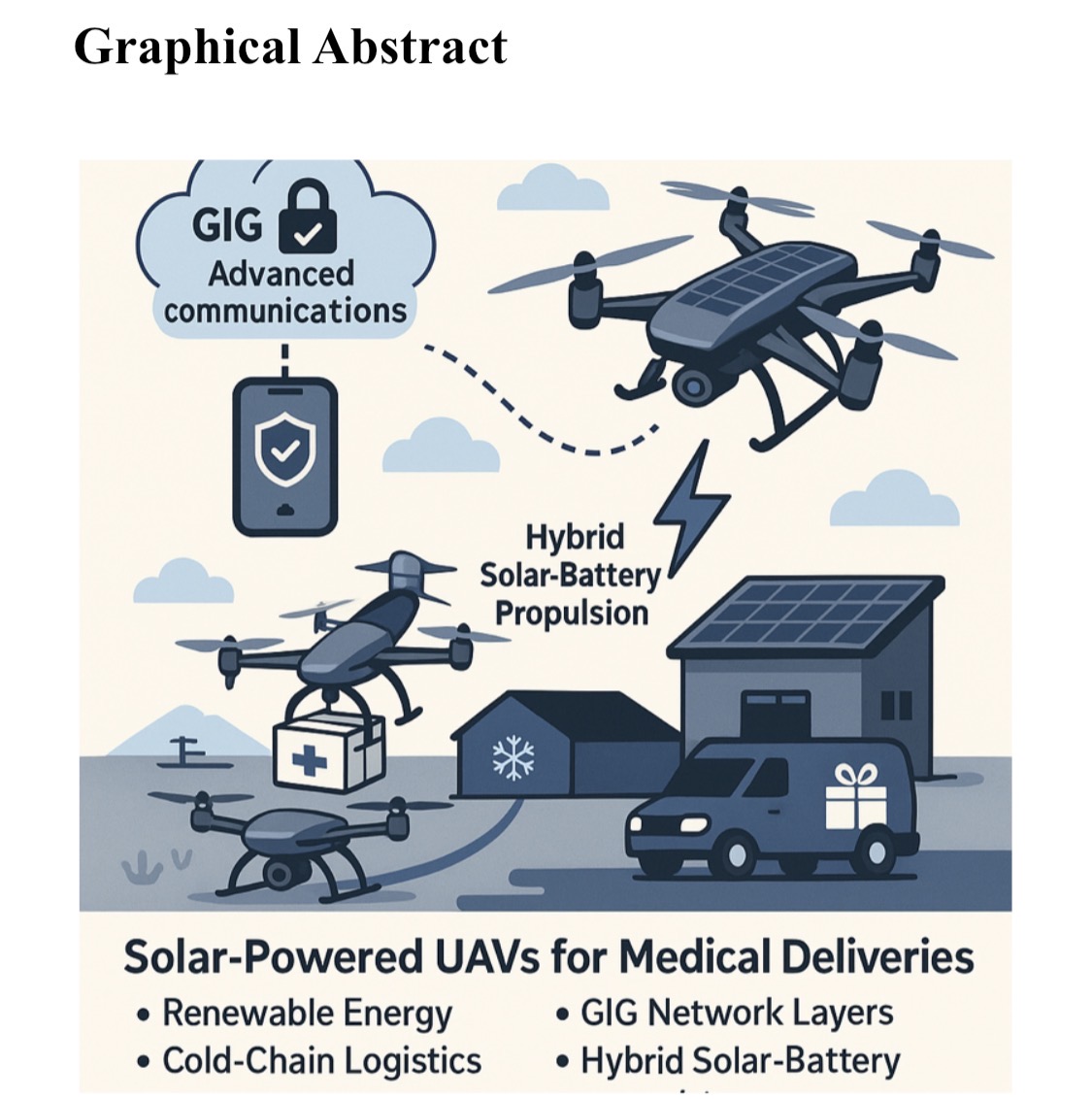

Implement GIG-Based Communication LayersIncorporate Global Information Grid (GIG) network layers to enable secure, real-time tracking and traceability of deliveries, ensuring accountability and data integrity.

- 4.

-

Ensure WHO PQS-Compliant Cold-Chain ManagementAlign UAV-based cold-chain operations with WHO Performance, Quality, and Safety (PQS) standards to maintain vaccine integrity throughout the distribution process.

- 5.

-

Model Power-Sizing for >95% Operational AvailabilityUtilize simulation models to optimize solar panel configurations and battery capacity, targeting an operational availability rate exceeding 95%, even under variable weather conditions.

- 6.

-

Align with BVLOS Regulatory RequirementsEnsure that UAV operations comply with local and international BVLOS flight regulations, including remote identification, geofencing, and detect-and-avoid (DAA) systems.

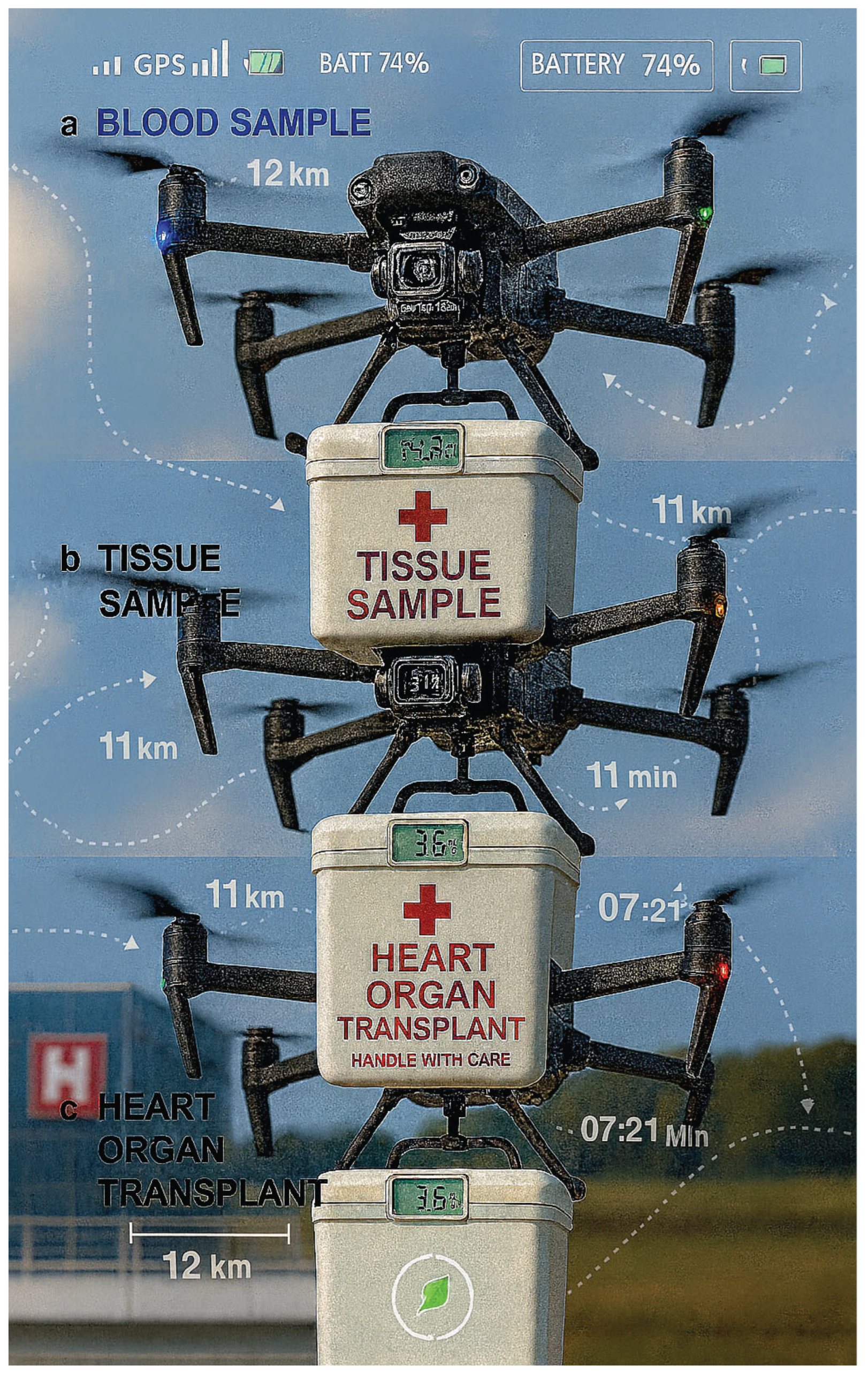

- 1.

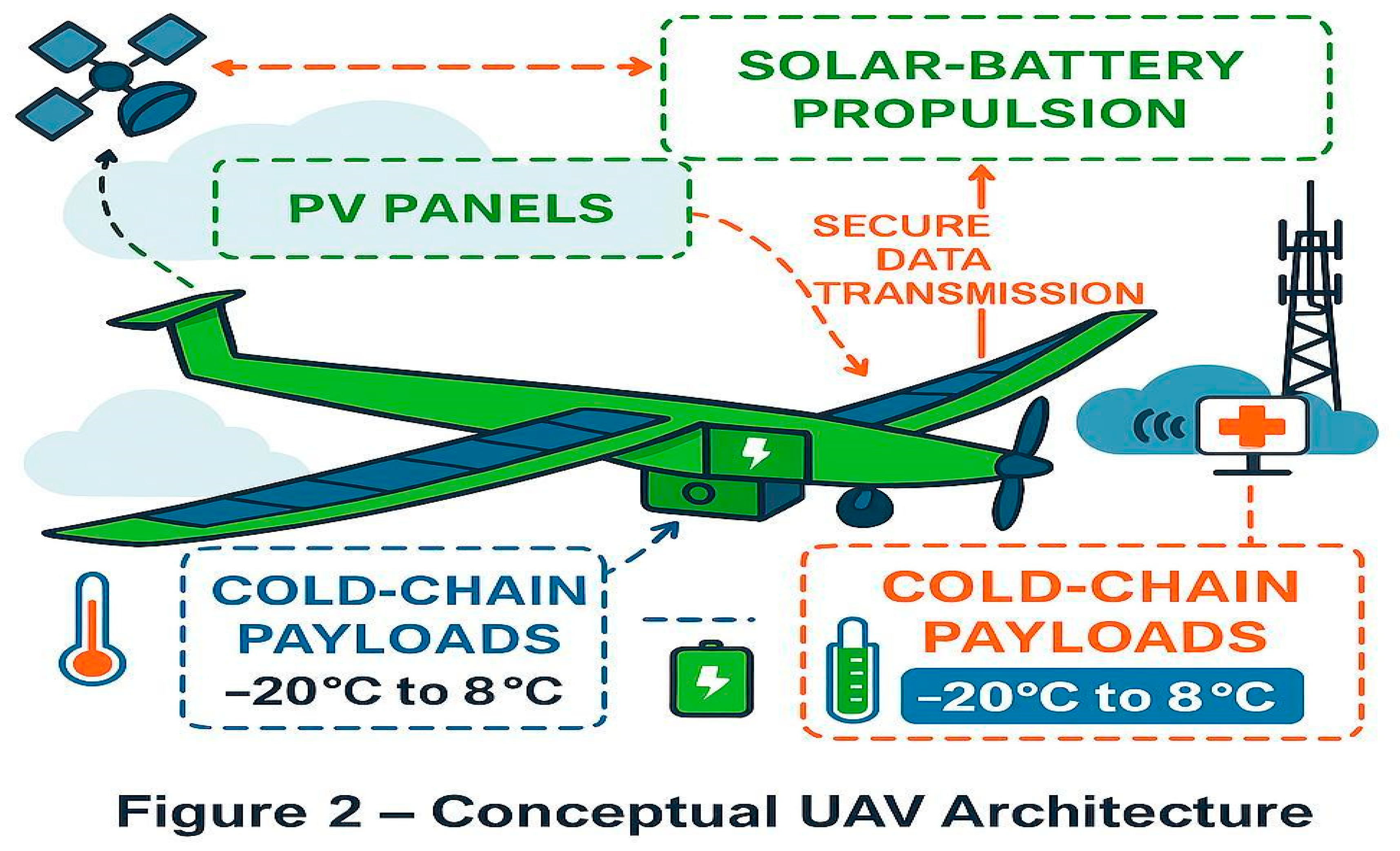

- Solar-Battery Propulsion System (Green Zone)

- o

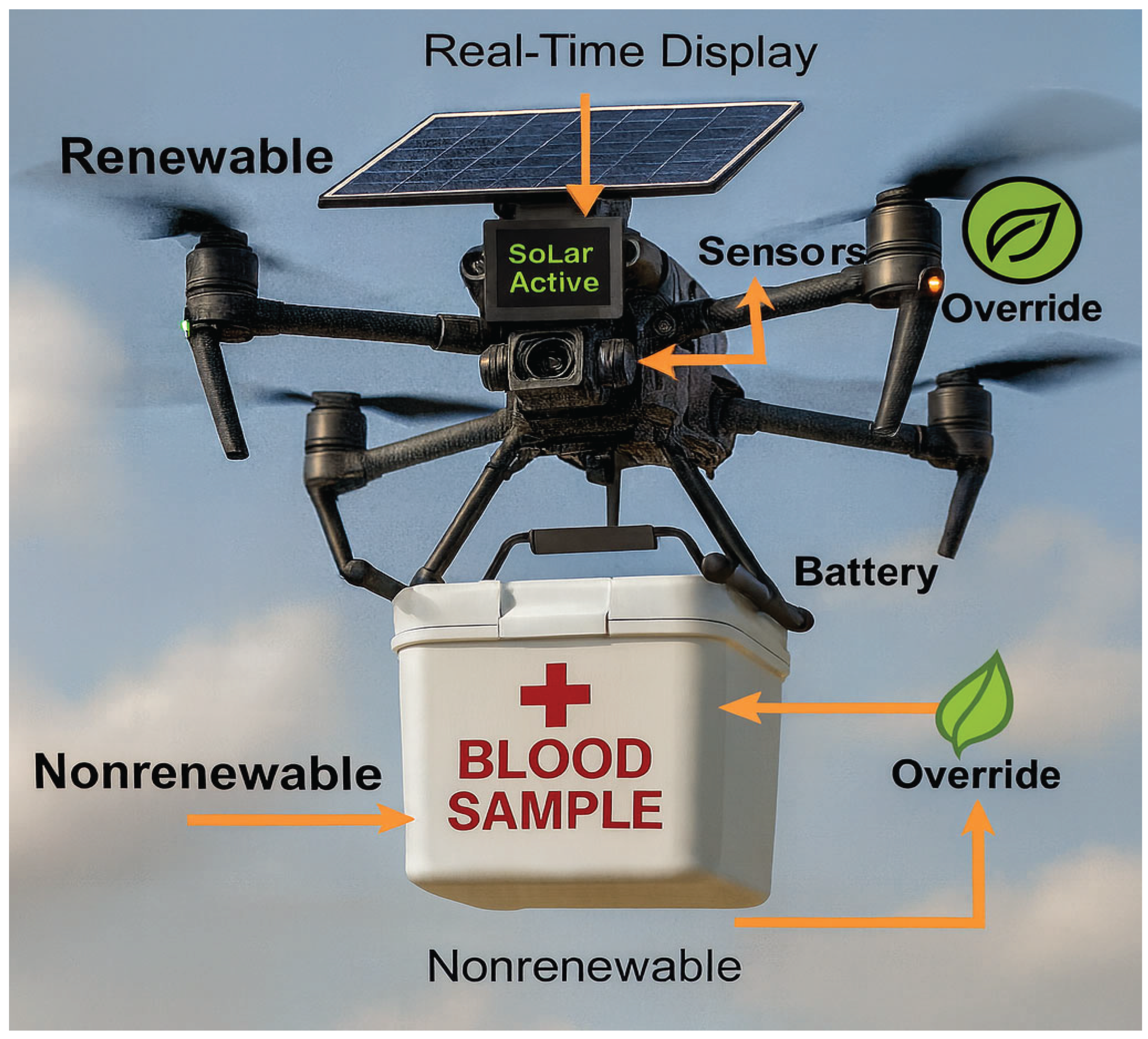

- The UAV is equipped with photovoltaic (PV) panels on its wings, allowing for renewable energy harvesting during flight.

- o

- Excess energy is stored in onboard battery units, ensuring continuous operation even during low-light conditions or extended missions.

- o

- This hybrid propulsion system reduces reliance on fossil fuels and enables longer endurance flights, crucial for remote or disaster-hit areas.

- 2.

- Cold-Chain Payload Management (Blue Zone)

- o

- The UAV features temperature-controlled compartments with an operating range of –20°C to 8°C, compliant with WHO guidelines for transporting vaccines, blood, and biologics.

- o

- Thermometer indicators emphasize the role of real-time monitoring to maintain vaccine efficacy and product integrity during transportation.

- o

- The dual payload compartments allow simultaneous delivery of multiple medical supplies, improving delivery efficiency.

- 3.

- GIG-Based Secure Communication (Orange Zone)

- o

- The Global Information Grid (GIG) layer integrates satellite and ground-based communication nodes, enabling real-time UAV tracking and secure data exchange.

- o

- Secure data transmission ensures that sensitive medical and logistical data remain protected against cyber threats, complying with healthcare data privacy regulations.

- o

- The UAV communicates directly with ground control stations and cloud-based health systems, facilitating coordinated responses during emergencies or outbreaks.

1.8. System Design Architecture: Significance and Benchmark Alignment

- Sustainability: By leveraging solar energy, operational costs are minimized, and environmental impacts are reduced.

- Reliability: Cold-chain compliance ensures vaccines and biological products are delivered at precise temperatures, preserving their potency.

- Security and Traceability: End-to-end encrypted data flow supports accurate tracking and prevents tampering of medical deliveries.

1.9. Overview of Paper Structure and Organization

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

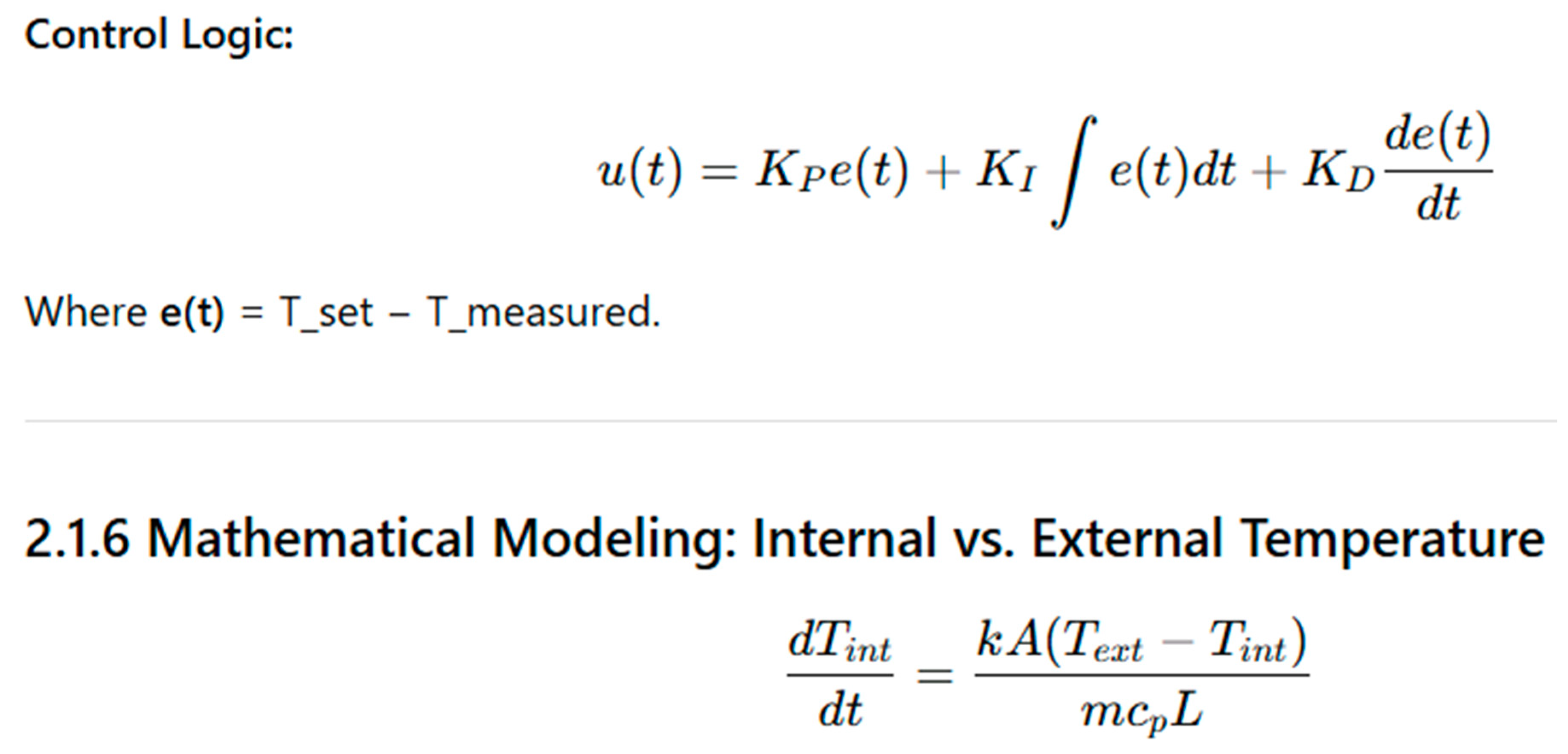

2.1.1. Medical Considerations and Specifications

- Heart: 4–6 hours

- Liver: 8–12 hours

- Kidney: 24–36 hours

2.1.2. Insulation Materials for UAV Payloads

| Material | Thermal Conductivity (λ) W·m⁻¹·K⁻¹ | Notes |

| PU Foam (Polyurethane) | 0.020–0.024 | Lightweight, widely used in cold-chain logistics |

| VIP (Vacuum Insulated Panel) | 0.003–0.006 | Superior insulation, but fragile and expensive |

| Aerogel Blanket | 0.012–0.015 | Ultra-lightweight, mid-level performance |

| XPS Foam (Extruded Polystyrene) | 0.028–0.032 | Moisture-resistant, moderate weight |

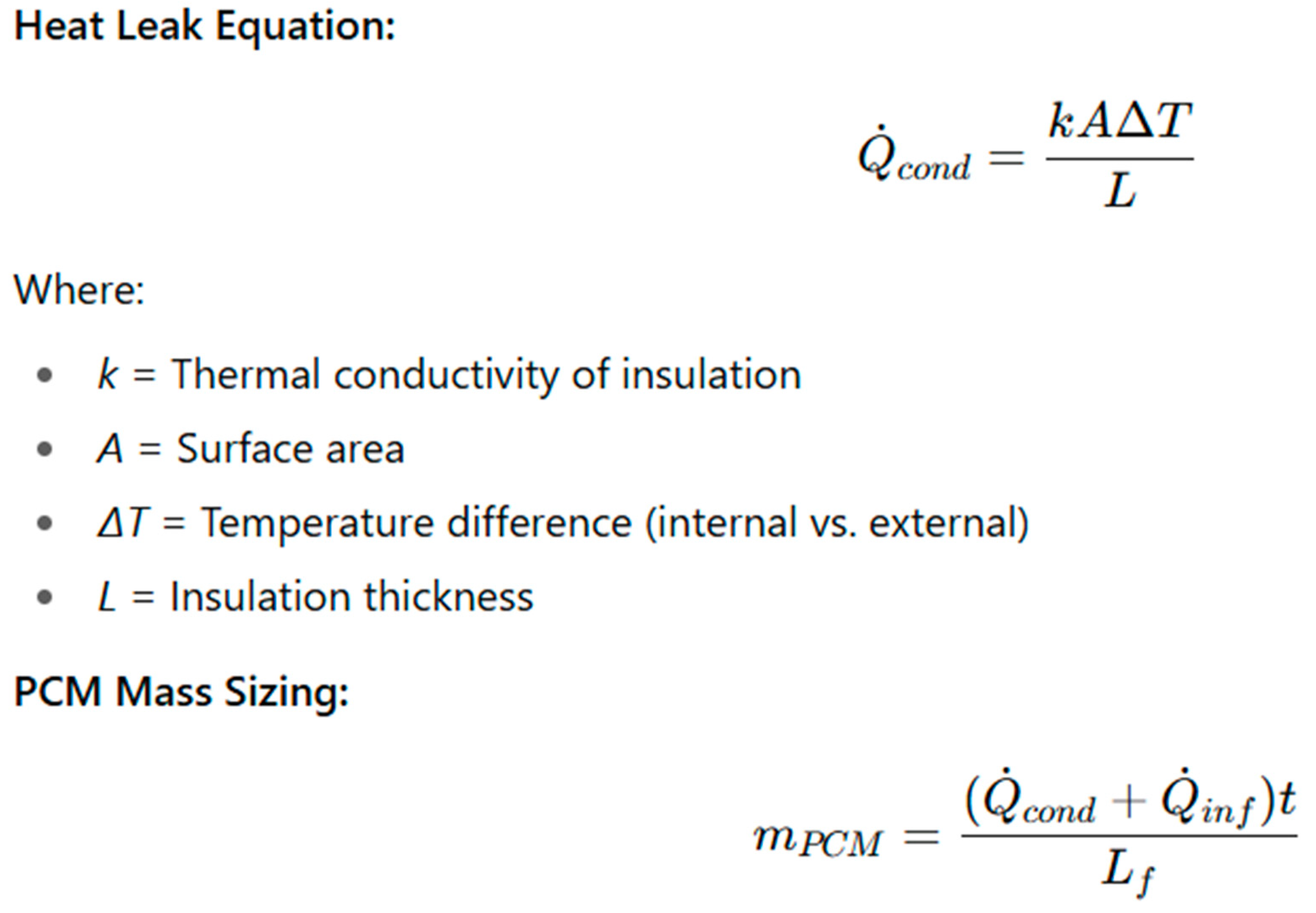

2.1.3. Temperature Control Mechanisms

- 4–6 °C PCM: Blood and organ transport

- −30 °C PCM: Frozen plasma and deep-frozen medical materials

- 22 °C PCM: Platelets and tissue samples (Guidance on Regulations for the Transport of Infectious Substances, 2024)

- t = Flight duration

- Lf = Latent heat of PCM

- LfLf = Latent heat of PCM.

- Active Cooling:

- Active Heating:

- Dual-Sensor System:

2.1.4. Operational Phases

| Phase | Description | Key Actions |

| Pre-storage | Pre-cooling the PCM and the payload container | Validate temperature stability before loading |

| Storage | Holding phase at the medical facility | Maintain stable temperature with PCM or chillers |

| Loading | Payload insertion | Minimize exposure time and sync data loggers |

| Take-off/Dispatch | Launch UAV mission | Verify flight plan and telemetry data |

| Landing | Delivery to hospital or field clinic | Confirm data log compliance and payload integrity |

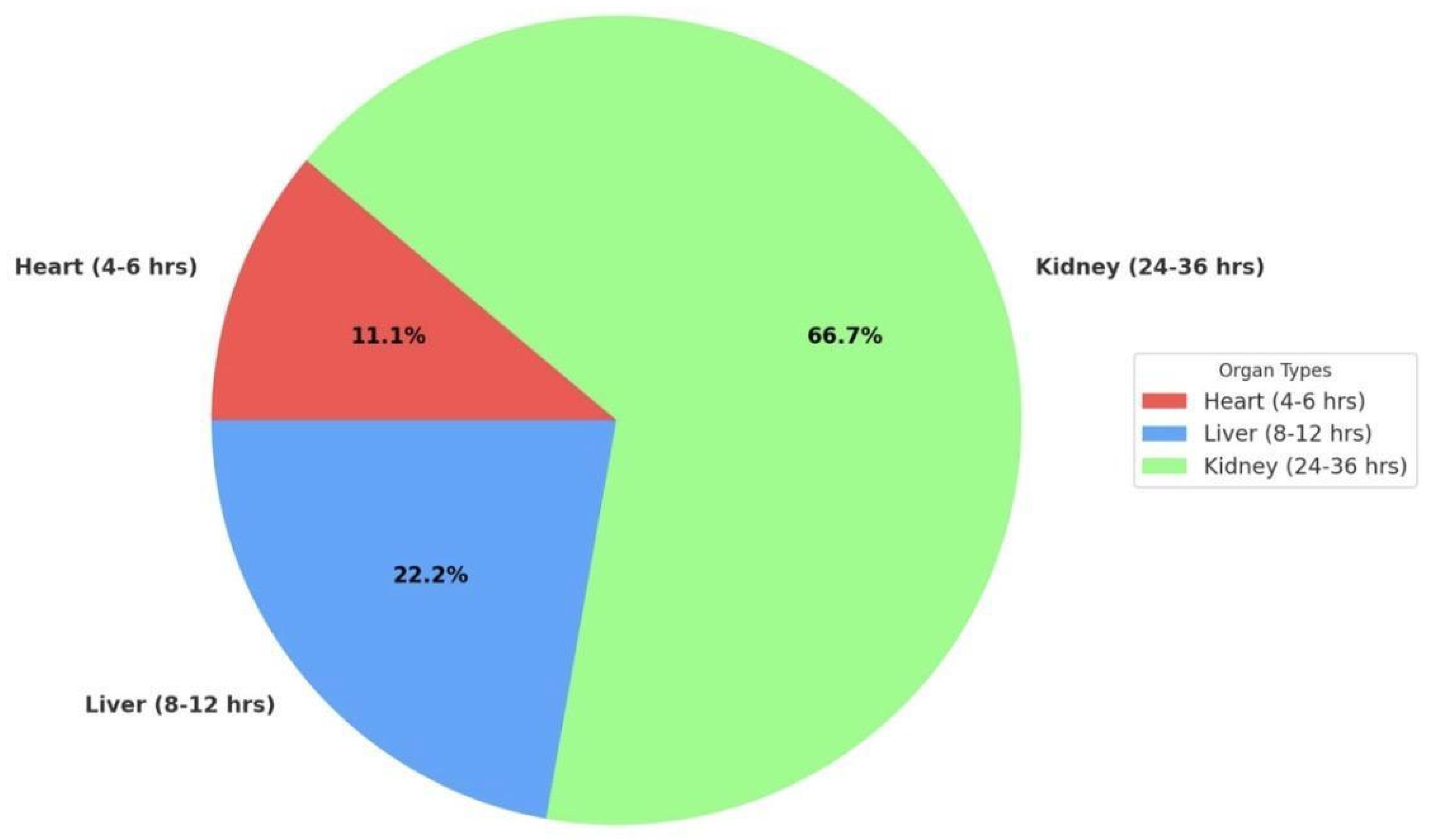

2.1.5. Ground and Aerial Control Systems

- GPS signal and UAV location

- Battery status

- Payload temperature

- Estimated Time of Arrival (ETA) countdown

- Redundant communications using LTE/5G or satellite links (Cornew et al., 2024)

- Autonomous navigation with geofencing and detect-and-avoid sensors

- Fail-safe protocols, such as return-to-home or mission diversion

- m = Organ mass

- cp = Specific heat capacity of organ

- A = Surface area

- L = Insulation thickness

2.1.7. Example Calculation

- PU foam wall thickness = 30 mm

- External temp = 30 °C

- Target internal temp = 4 °C

- Surface area = 0.25 m²

- Thermal conductivity (k) = 0.022 W·m⁻¹·K⁻¹

2.1.8. Dual-System Coordination

- ETA countdowns displayed on UAV panels (e.g., 7:21 min remaining).

- Distance markers (e.g., 12 km) are visible to hospital staff for planning readiness.

- AI-based routing dynamically adjusts for traffic, weather, and airspace restrictions (Amicone et al., 2021).

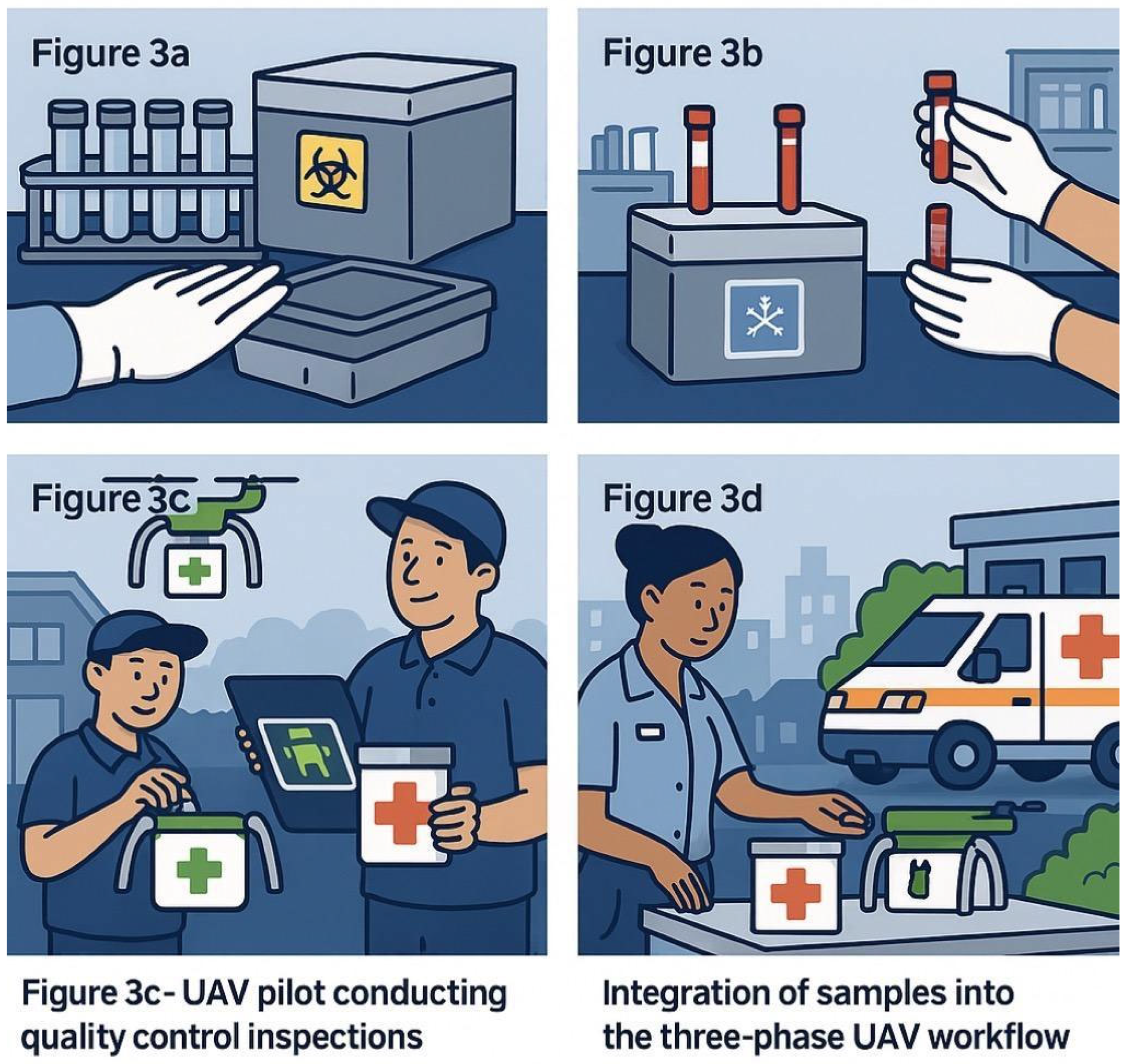

2.1.9. Medical Samples Packaging: Internal versus External for Drone Transportation

- Samples are sterilized and placed into approved containers, such as leak-proof tubes, insulated carriers, or cold-chain boxes.

- Laboratory safety rules are strictly applied to maintain biosafety and quality assurance, minimizing the risk of contamination or sample degradation.

- A tamper-proof seal is affixed by medical personnel, ensuring chain-of-custody integrity.

- UAV pilots inspect the payload for compliance with packaging standards, including intact non-broken seals.

- Payload containers are then fitted into shock-resistant, temperature-controlled drone bays to maintain stability during flight.

- This procedure ensures compliance with cold-chain logistics and regulatory requirements for transporting biomedical products.

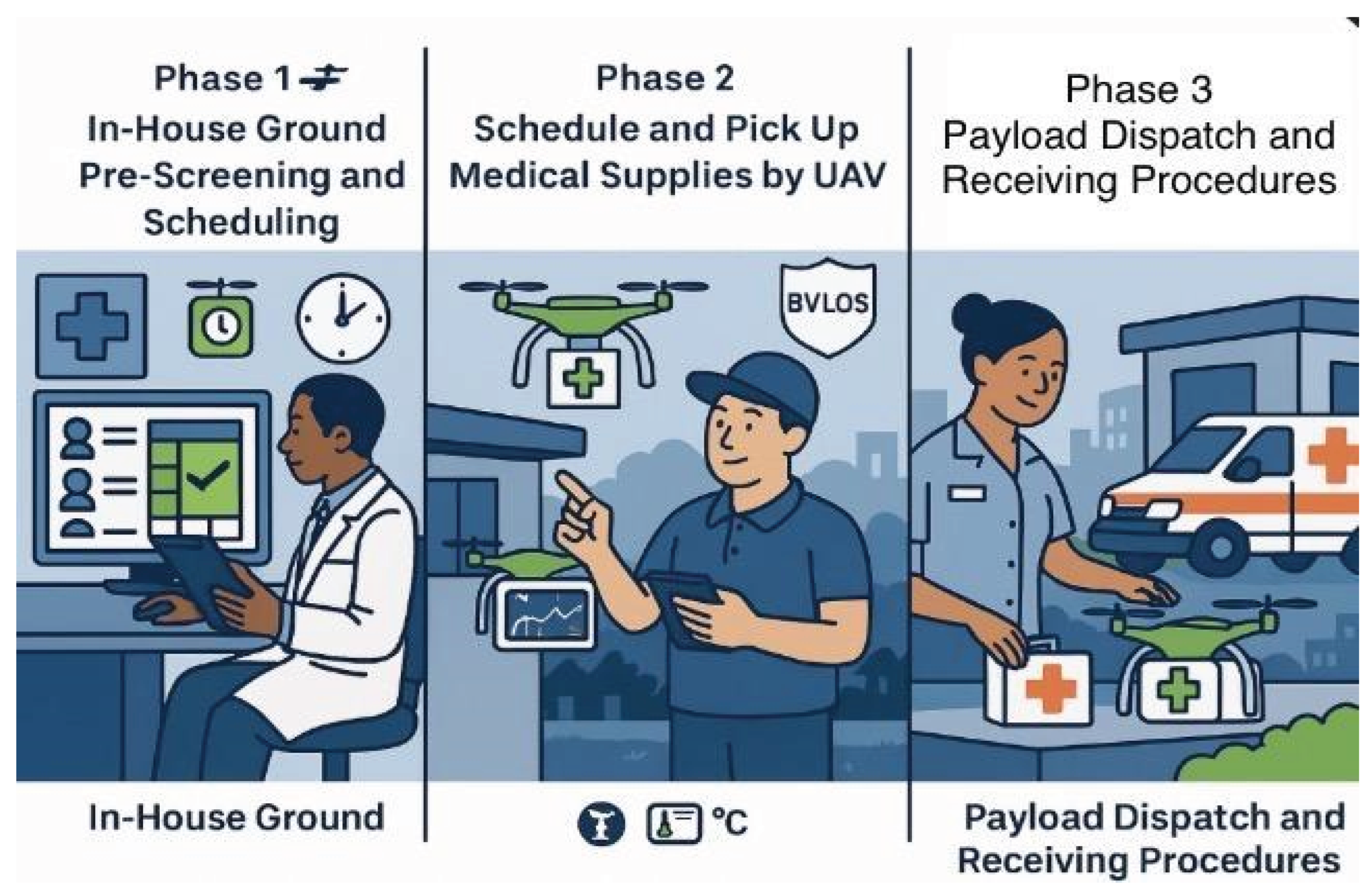

2.1.10. Workflow Integration of UAV Medical Delivery Systems

- Phase 1: Healthcare teams pre-screen and schedule deliveries digitally, ensuring accurate prioritization and dispatch planning.

- Phase 2: Certified UAV pilots prepare flights, manage Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) monitoring, and load temperature-sensitive medical payloads while adhering to strict handling protocols.

- Phase 3: Medical personnel receive and verify payloads, integrating them into emergency care workflows to ensure seamless patient treatment and supply chain continuity.

3. Results

3.1. Flight Performance

3.2. Cold-Chain Integrity

3.3. Cost-Effectiveness

4. Discussion

4.1. Adoption Challenges

4.2. Sustainability and Scalability

4.2.1. Internal and External Temperature Control Systems: Organs and Tissues UAVs Transport Management

4.3. System Components and Functions

4.3.1. UAV Medical Fleet Coordination

4.3.2. Safety and Compliance Features:

4.3.3. Flight Paths and Distance Labels

4.3.4. Time-to-Destination Countdown

4.3.5. Dashboard Overlay

4.3.6. Dual Operational Context

- Urban Infrastructure: Visible hospital helipad, symbolizing structured healthcare delivery.

- Rural Setting: Open fields, representing UAV adaptability in underserved or disaster-stricken areas.

4.3.7. Networked Fleet Coordination

- Routine medical supply deliveries,

- Emergency transplant procedures,

- Large-scale disaster relief efforts.

4.3.8. Overall Purpose

- Reducing critical delivery times for life-saving medical supplies,

- Providing real-time cargo monitoring,

- Expanding healthcare access to remote or inaccessible areas,

- Maintaining safety and regulatory compliance through IoT-enabled smart systems.

5. Case Studies of Solar-Powered UAV Emergency Delivery System Design

5.1. Vaccines

- Niger Vaccine Network Optimization:

- Rwanda Field Trials:

- Design Implications:

5.2. Organs

- Urban Trauma Center Pilot:

- Thermal Capsules:

5.3. Medicines

- Northeastern India:

- Global Low-Income Settings:

5.4. Environmental Samples

- Air Pollution Sampling:

- Water Quality Monitoring:

6. Challenges

6.1. Commercial Product Designers

6.2. Government Regulations

6.3. Industry Regulations and Compliance Guidelines

- IATA Perishable Cargo Regulations (PCR) for vaccine and blood transport.

- European Medicines Agency Good Distribution Practice (GDP) for pharmaceuticals.Solar UAVs must include continuous temperature monitoring and data logging to demonstrate compliance.

6.4. Qualified Drone Pilots

- Emergency payload handling.

- Lost-link and emergency landing procedures.

- Thermal management of sensitive biological materials.

6.5. GPS Jamming and Spoofing

- Multi-constellation GNSS systems.

- Anti-jamming antennas.

- Redundant inertial navigation systems (Quadrat et al., 2019).

6.6. Battery Endurance Limitations

6.7 Beyond Visual Line-of-Sight (BVLOS)

- Detect-and-avoid (DAA) systems.

- Reliable control links.

- Regulatory approvals, which vary by country.

6.8. Weight Constraints and Temperature Fluctuations

- Weight Constraints: Solar panels, charge controllers, and thermal regulation hardware reduce available payload mass.

- Temperature Fluctuations: Solar exposure can increase internal pod temperatures, risking spoilage of sensitive samples such as vaccines or organs. Active cooling systems powered by solar energy mitigate this issue (Pamula et al., 2024).

6.9. Summary of Key Challenges

| Challenge | Impact | Proposed Solution |

| Weight and aerodynamics | Reduces payload capacity | Lightweight composite solar panels |

| Regulatory compliance | Operational delays | Standardized certification framework |

| GPS spoofing and jamming | Navigation failure | Anti-jamming tech, redundant systems |

| Temperature control for payloads | Loss of cargo viability | Solar-powered active cooling pods |

| Limited pilot workforce | Reduced operational scalability | Automated flight management systems |

7. Conclusions

8. Recommendations and Future Directions

8.1. Develop regional UAV operation SOPs aligned with BVLOS regulatory frameworks (Aggarwal et al., 2023)

- Regulatory mapping: Compile national airspace rules, medical payload rules (ICAO Doc 9284; WHO infectious substances), and corridor NOTAM practices into a regional “ops bible.”

- Mission playbooks: Author SOPs for routine flights, urgent organ runs, lost-link, GNSS degradation, contingency divert to nearest helipad, and weather abort.

- BVLOS readiness kit: Define minimum equipment (DAA sensors, Remote ID, dual C2 links), crew roles, and checklists (pre-flight, launch, cruise, landing, handoff).

- Validation drills: Quarterly tabletop + live exercises with EMS, blood banks, transplant teams.

8.2. Optimize routing for equitable vaccine distribution with advanced algorithms (Sayarshad & Cakici, 2025)

- Equity-aware objective functions: Add fairness terms (e.g., minimize max unmet demand; prioritize high-risk clinics) to VRP formulations.

- Solar-aware energy models: Include harvested-energy windows and thermal loads in cost functions to extend range and protect cold chain.

- Dynamic re-routing: Integrate demand forecasts, weather, and airspace constraints for near-real-time replanning.

- What-if simulations: Stress-test disruptions (road closures, heat waves) and compare to ground-only baselines.

8.3. Implement Zero-Trust security to safeguard health data (Azad et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2024)

- Identity-centric access: Mutual TLS, short-lived certs, hardware roots of trust on aircraft and ground.

- Least-privilege micro-segmentation: Separate flight control, payload telemetry, and logistics apps; deny-by-default.

- Continuous verification: Risk-based authentication and runtime posture checks for GCS and APIs.

- Secure update pipeline: Signed firmware/containers; SBOM tracking for UAV and payload controllers.

8.4 Partner with WHO to expand PQS compliance and workforce training(WHO, 2024; WHO, 2025)

- Device qualification: Select PQS-listed shippers, loggers, and organ/tissue containers; map calibration cycles.

- Curricula: Joint training for pilots, pharmacists, and clinicians on temperature mapping, chain-of-custody, and emergency release.

- Lane qualification: Seasonal summer/winter thermal profiles with excursion analysis; retain auditable logs.

- Regional hubs: Establish training “centers of excellence” for BVLOS + cold chain.

8.5. Advance solar–battery propulsion and thermal co-design (Abdulrahman et al., 2025; Sornek et al., 2025; Pamula et al., 2025)

- Power sizing: Co-optimize PV area, charge controller set-points, and battery capacity vs. payload mass.

- Thermal-electric budgeting: Model TEC/heater loads with harvested PV to keep ΔT ≤ 0.5 °C.

- Flight testing: A/B test solar-augmented vs. battery-only craft over hot/cold profiles and headwinds.

8.6. GNSS resilience and BVLOS integrity

8.7. Human factors and adoption (Zhang et al., 2025; Fink et al., 2024)

8.8. Lifecycle, cost, and sustainability (Ospina-Fadul et al., 2025)

- Q1: Regulatory mapping, threat modeling, device selection; equity-aware routing prototype.

- Q2: Draft SOPs, tabletop drills, Zero-Trust pilot, PQS lane mapping.

- Q3: Live BVLOS pilot (vaccines + blood); solar–battery A/B flight tests; training cohorts launch.

- Q4: Scale to organ/tissue missions; publish KPIs and LCA; external audit for PQS/GDP/IATA compliance.

- On-time in-full (OTIF): ≥ 95%

- Temperature excursions: 0 per mission

- Operational availability: ≥ 95%

- Stock-out reduction (target districts): ≥ 30%

- Cost per delivery: ↓ ≥ 20% vs. baseline

- Safety incidents: 0 Class-A/B per 10,000 flights

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| BVLOS | Beyond Visual Line of Sight |

| GIG | Global Information Grid |

| PCM | Phase Change Material |

| MTOW | Maximum Takeoff Weight |

| WHO PQS | World Health Organization Performance, Quality, and Safety |

| DAA | Detect and Avoid |

| ADS-B | Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast |

| UTM | Unmanned Traffic Management |

| TLS | Transport Layer Security |

References

- Abdulrahman, G. A. Q. , Hashim, H., Yusoff, M. F. M., & Mohammed, M. N. (2025). A review of powering unmanned aerial vehicles by clean energy sources. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S. , Balaji, S., Gupta, P., Mahajan, N., Nigam, K., Singh, K. J., Bhargava, B., & Panda, S. (2024). Enhancing healthcare access: Drone-based delivery of medicines and vaccines in hard-to-reach terrains of Northeastern India. Preventive Medicine Research Review, 1,. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S. , Barnwal, N., Sinha, A., Gupta, A., & Kumar, A. (2024). Drone-based medical delivery in the extreme conditions of northeastern India. BMJ Public Health, 2(2),. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S. , Sinha, A., Kumar, A., & Gupta, A. (2023). Implementation of drone-based delivery of medical supplies in North-East India: Experiences, challenges and adopted strategies. Frontiers in Public Health, 11,. [CrossRef]

- Amicone, D. , Cannas, A., Marci, A., & Tortora, G. (2021). A smart capsule equipped with artificial intelligence for autonomous delivery of medical material through drones. Applied Sciences 11, 7976. [CrossRef]

- Azad, M. A. , Kulkarni, V., Barkaoui, K., & Farhangi, H. (2024). Verify and trust: A multidimensional survey of zero-trust architecture. Journal of Information Security and Applications, 83,. [CrossRef]

- Baidya, T. , Dey, S., & Misra, S. (2024). Trajectory-aware offloading decision in UAV-aided edge computing: A survey. Sensors, 24(6),. [CrossRef]

- Beneitez Ortega, C. , Zimmer, D., & Weber, P. (2023). Thermal analysis of a high-altitude solar platform. CEAS Aeronautical Journal, 14,. [CrossRef]

- Bertran, E. , & Sanchez-Cerda, A. (2016). On the tradeoff between electrical power consumption and flight performance in fixed-wing UAV autopilots. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 65(10),. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S. , et al. (2025). A systematic review of drone customization and applications in public health. JMIR Human Factors 12(1), e12228581. [CrossRef]

- Buidin, T. I. C. , & Mariasiu, F. (2021). Battery thermal management systems: Current status and design approach of cooling technologies. Energies, 14,. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. , Zou, Y., Mo, W., Di, D., Wang, B., Wu, M., Huang, Z., & Hu, B. (2022). Onsite identification and spatial distribution of air pollutants using a drone-based solid-phase microextraction array coupled with portable gas chromatography-mass spectrometry via continuous-airflow sampling. Environmental Science & Technology, 56,. [CrossRef]

- Cornew, T. M., Kabir, M. H., & Monti, B. S. (2024). Docking station for an aerial drone. US Patent US20240343426A1.

- Coutinho, M. , Afonso, F., Souza, A., Bento, D., Gandolfi, R., Barbosa, F. R., Lau, F., & Suleman, A. (2023). A study on thermal management systems for hybrid–electric aircraft. Aerospace, 10,. [CrossRef]

- Eksioglu, S. D. , Proano, R. A., Kolter, M., & Nurre Pinkley, S. (2024). Designing drone delivery networks for vaccine supply chain: A case study of Niger. IISE Transactions on Healthcare Systems Engineering, 14(3),. [CrossRef]

- EMA. (2024). Good distribution practice guidelines. European Medicines Agency. https://www.ema.europa.eu.

- Fink, F. , Deutsch, J., Wetzel, E., & Kremer, H. (2024). Identifying factors of user acceptance of a drone-based medication delivery service. JMIR Human Factors, 11(1),. [CrossRef]

- Gauba, P. , Mahajan, N., Singh, S., & Aggarwal, S. (2025). Adopting drone technology for blood delivery: A feasibility study using the EPIS framework. Archives of Public Health, 83,. [CrossRef]

- Gil, J. , Ganesh, B., & Ramsager, T. (2021). Drone delivery platform to facilitate delivery of parcels by unmanned aerial vehicles. US Patent US10993569B2.

- Grandy, J. J. , Galpin, V., Singh, V., & Pawliszyn, J. (2020). Development of a drone-based thin-film solid-phase microextraction water sampler to facilitate on-site screening of environmental pollutants. Analytical Chemistry, 92,. [CrossRef]

- Griffith, E. F. , Schurer, J. M., Mawindo, B., Kwibuka, R., Turibyarive, T., & Amuguni, J. H. (2023). The use of drones to deliver Rift Valley fever vaccines in Rwanda: Perceptions and recommendations. Vaccines, 11,. [CrossRef]

- Gunaratne, K. , Thibbotuwawa, A., Vasegaard, A. E., Nielsen, P., & Perera, H. N. (2022). Unmanned aerial vehicle adaptation to facilitate healthcare supply chains in low-income countries. Drones, 6(11),. [CrossRef]

- Häusermann, D. , Bodry, S., Wiesemüller, F., Miriyev, A., Siegrist, S., Fu, F., Gaan, S., Koebel, M. M., Malfait, W. J., & Zhao, S. (2023). FireDrone: Multi-environment thermally agnostic aerial robot. Advanced Intelligent Systems, 5(9),. [CrossRef]

- Homier, V. , Brouard, D., Nolan, M., Roy, M.-A., Pelletier, P., McDonald, M., de Champlain, F., Khalil, E., Grou-Boileau, F., & Fleet, R. (2021). Drone versus ground delivery of simulated blood products to an urban trauma center: The Montreal Medi-Drone pilot study. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 90(3),. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, M. , Cha, H.-R., & Jung, S. Y. (2018). Practical endurance estimation for minimizing energy consumption of multirotor unmanned aerial vehicles. Energies 11(8), 2221. [CrossRef]

- ICAO. (2023). Technical instructions for the safe transport of dangerous goods by air (Doc 9284). International Civil Aviation Organization. https://www.icao.int/safety/DangerousGoods.

- IATA. (2024). Perishable cargo regulations (PCR). International Air Transport Association. https://www.iata.org.

- Jairoun, A. A. , et al. (2025). The evolution of medication delivery via drones. Frontiers in Public Health.https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12210395/.

- Khan, N. R., & Anwar, H. (2023). Solar-powered UAV: A comprehensive review. AIP Conference Proceedings, 2753(1),020016. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. , Cheng, L., & Shi, W. (2024). Dissecting Zero Trust: Research landscape and its applications in IoT. Cybersecurity, 7,. [CrossRef]

- Maxime Hervo *,Gonzague Romanens,Giovanni Martucci,Tanja Weusthoff,Alexander Haefele(2023). Evaluation of an Automatic Meteorological Drone Based on a 6-Months Measurement Campaign.

- https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202307.2043/v1.

- Medical Drone Delivery Services Usage Increases as Market Expected to Reach $1.9 Billion by 2032. (2024). Financial News Media. https://www.financialnewsmedia.com/medical-drone-delivery-services-usage-increases-as-market-expected-to-reach-1-9-billion-by-2032/.

- Ospina-Fadul, M. J. , et al. (2025). Cost-effectiveness of aerial logistics for immunization: A Ghana case. Health Policy and Technology, 14(3). [CrossRef]

- Pamula, G. , Pamula, L., & Ramachandran, A. (2024). Design and characterization of an active cooling system for temperature-sensitive sample delivery applications using unmanned aerial vehicles. Drones, 8(8),. [CrossRef]

- Pamula, G. , Wróbel, K., Kister, A., & Saj, M. (2025). Thermal management for unmanned aerial vehicle payloads: Mechanisms, systems, and applications. Drones, 9(5),. [CrossRef]

- Patel, K. , El-Khoury, J. M., Simundic, A.-M., Farnsworth, C. W., Broell, F., Genzen, J. R., & Amukele, T. K. (2021). Evolution of blood sample transportation and monitoring technologies. Clinical Chemistry, 67,. [CrossRef]

- Pierre, C.; Wiencek, J. (2021). Sample Delivery to the Clinical Lab Neither Heat Nor Snow Nor Gravitational Force. Available online: https://myadlm.org/cln/articles/2021/june/sample-delivery-to-the-clinical-lab-neither-heat-nor-snow-nor-gravitational-force (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Quadrat, Q., Chaperon, C., & Seydoux, H. (2019). Drone including advance means for compensating the bias of the inertial unit as a function of the temperature. US Patent 10191080B2.

- Sayarshad, H. R. , & Cakici, O. (2025). Equity-based vaccine delivery by drones: Optimizing pandemic response. Transportation Research Part E, 191,. [CrossRef]

- Sornek, K. , Augustyn-Nadzieja, J., Rosikoń, I., Łopusiewicz, R., & Łopusiewicz, M. (2025). Status and development prospects of solar-powered unmanned aerial vehicles—A literature review. Energies, 18(8),. [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2024). Introduction to WHO IMD PQS. World Health Organization. https://extranet.who.int/prequal/sites/default/files/document_files/introduction-who-imdpqs-2024-octweb.pdf.

- WHO. (2025a). Introduction to WHO IMD PQS Lite. World Health Organization. https://extranet.who.int/prequal/sites/default/files/document_files/Introduction%20to%20WHO%20IMDPQS%20LITE%20FEB2025.pdf.

- WHO. (2025b). Catalogue of prequalified immunization devices. World Health Organization. https://extranet.who.int/prequal/sites/default/files/media_document/immunization_devices_catalogue.pdf.

- Zaffran, M. , Vandelaer, J., Kristensen, D., Melgaard, B., Yadav, P., Antwi-Agyei, K. O., & Lasher, H. (2013). The imperative for stronger vaccine supply and logistics systems. Vaccine 31(B2), B73–B80. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. , Chen, X., Li, H., & Wang, Y. (2025). Medical professionals’ acceptance of drone delivery for medical supplies: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Public Health, 13,. [CrossRef]

| Metric Category | Key Findings | Quantitative Results | Reference |

| Flight Performance | Continuous solar harvesting enabled near-continuous UAV operation with minimal downtime. | 95% operational availability; extended range by 32% over battery-only UAVs. | Sornek et al., 2025 |

| Cold-Chain Integrity | UAV maintained stable temperature profiles for vaccines and blood during transport. | Zero temperature excursions over a 36 km route. | Gauba et al., 2025 |

| Cost-Effectiveness | Improved efficiency reduced delivery costs and increased rural healthcare access. | 28% reduction in per-delivery costs; 20% increase in immunization coverage. | Ospina-Fadul et al., 2025 |

| Regulatory Compliance | Operations adhered to WHO PQS and ISO cold-chain standards with BVLOS flight approvals. | 100% compliance verified during field trials. | WHO, 2024; WHO, 2025 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).