1. Introduction

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), or drones, have emerged as a groundbreaking technology with significant potential to revolutionize various sectors, including healthcare [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. The ability of drones to navigate challenging terrains, avoid traffic congestion, and provide rapid delivery makes them an attractive option for transporting critical medical materials such as blood samples [

7,

8]. Traditional car transportation, while effective, is often hindered by traffic delays, road conditions, and geographic barriers, which can compromise the timely delivery of medical samples. Additionally, car transportation is, compared to drone transportation, way more expensive [

6,

9,

10].

Currently, drones are already being utilized for transporting critical medical materials such as blood samples, vaccines, and medications in remote and underserved regions [

11]. For instance, in Rwanda and Ghana, drones operated by companies like Zipline have been successfully delivering blood products and essential medical supplies to rural healthcare facilities, significantly reducing delivery times and overcoming logistical challenges posed by difficult terrains and poor infrastructure [

12,

13]. These applications underscore the versatility and efficiency of drones in enhancing healthcare delivery, particularly in areas where traditional transportation methods are hindered by geographical and infrastructural barriers. This study aims to further explore the ecological impact and efficiency of drones compared to traditional transportation methods in the context of medical sample transportation in central Europe.

The importance of maintaining sample integrity during transport cannot be overstated, as delays and environmental conditions can significantly impact the accuracy of diagnostic tests [

14,

15,

16]. This study aims to bridge the knowledge gap by systematically examining the impact of high-speed drone transportation compared to traditional car transportation on analytical results of different analytes. By subjecting various blood materials and analytes to both transportation modalities under diverse weather conditions, this study seeks to elucidate the differential effects on sample integrity and analytical outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

Sample Collection and Preparation: Blood samples, including Blood in EDTA, Serum, Li-Heparin Plasma und citrate plasma tubes (BD Vacutainer™), were collected using standard venipuncture techniques by trained healthcare professionals and were immediately aliquoted into appropriate containers to minimize preanalytical variability.

Transportation Modalities: Blood samples were transported using two distinct modalities: high-speed drone transportation and traditional car transportation. For drone transportation, a custom-built UAV equipped with secure sample containers was utilized (Jedsy Drone Company). The drone's maximum speed exceeded 100 km/h, enabling rapid transit between designated pickup and delivery points. Car transportation involved the use of standard medical transport vehicles operated by trained personnel following established protocols. The duration of the samples transported by drone was 32 minutes. The duration of transportation by car was 30 minutes.

Dangerous Goods: The authorized container for dangerous goods is the VACUETTE® Transport Box (VTB) link Manufactured by Greiner Bio-One GmbH. Certified to safely transport UN3373 Biological Substance Category B was used to transport the blood samples with the drone.

Experimental Design: Transportation experiments were conducted under diverse weather conditions in realistic scenarios and assess the resilience of each transportation modality. Weather conditions varied between 0 and 20 degrees Celsius, encompassing a spectrum of environmental factors likely to influence sample integrity during transit. Temperature (Libero CL V9.14) and vibration (TDK InvenSense) data were continuously monitored during transportation using data loggers and accelerometers.

Vibration Metrics: To measure the vibration levels experienced during transportation, TDK InvenSense accelerometers were used. These high-precision sensors were placed inside the sample containers to capture real-time vibration data throughout the journey. The accelerometers measured tri-axial vibrations (x, y, and z axes) and recorded data at high frequency (4 times per second) to ensure accurate representation of the transportation conditions. The vibration data was then analyzed to determine the impact of transportation-induced mechanical agitation on blood sample integrity.

Analytical Assays: A comprehensive panel of analytes spanning clinical chemistry, hematology, and coagulation parameters was selected for analysis to assess the impact of transportation modalities on sample integrity and analytical outcomes. A total of 27 analytes were tested on serum samples, 20 on EDTA whole blood, 26 on Lithium-Heparin plasma, and 5 on Citrate plasma, encompassing a broad spectrum of clinically relevant markers.

Statistical Analysis: Statistical analyses were performed using established methodologies, including Passing Bablok regression and Bland-Altman analysis, to evaluate the agreement between transported samples and reference controls. Correlation coefficients (r) and slopes were calculated to quantify the degree of concordance between transportation modalities. Additionally, mean percentage differences were assessed to identify analytes exhibiting significant deviations from the negative control and ascertain the clinical relevance of observed discrepancies using the software MedCalc Statistical Software version 22.030 (MedCalc Software bv, Ostend, Belgium;

https://www.medcalc.org; 2020)

Quality Control Measures: Stringent quality control measures were implemented throughout the transportation and analytical processes to ensure the reliability and validity of results. Calibration checks, instrument maintenance, and proficiency testing were performed regularly to uphold analytical accuracy and precision. Furthermore, temperature monitoring (Libero CL V9.14) and data logging mechanisms were employed to monitor sample conditions during transportation and safeguard against potential deviations.

Flight Planning: Software Used: Pix4D and PX4 Autopilot

Flight Paths: Detailed flight paths were planned using to cover the entire study area. The paths were designed to ensure comprehensive coverage and data overlap.

Altitude: The flights were conducted at an altitude of 100 meters on average (

Table 1 and

Table 2).

Flight Execution: Number of Flights: A total of 12 flights were conducted over the study period.

Duration: Each flight lasted approximately 30 minutes.

Weather Conditions: Flights were carried out under various weather conditions including light rain, winds (up to 40 km/h) and sunshine.

Aircraft: Operations are performed using the Jedsy Glider. The aircraft configuration features ADS-B IN transceiver, FLARM and Remote ID broadcast. Each aircraft used has a serial number compliant with ANSI/CTA-2063-A-2019, Small Unmanned Aerial Systems Serial Numbers, 2019, according to Article 40(4) of Regulation (EU) 2019/945. Jedsy’s manufacturer code is 1883, assigned by the International Civil Aviation Organization

Routes: The Route of the Drone was between Vaduz, Liechtenstein (47.134787, 9.513150) and Buchs SG Switzerland (47.166668, 9.466664). The average flight hight was 540 metres above mean sea level where the hight over ground was 100 meter on average.

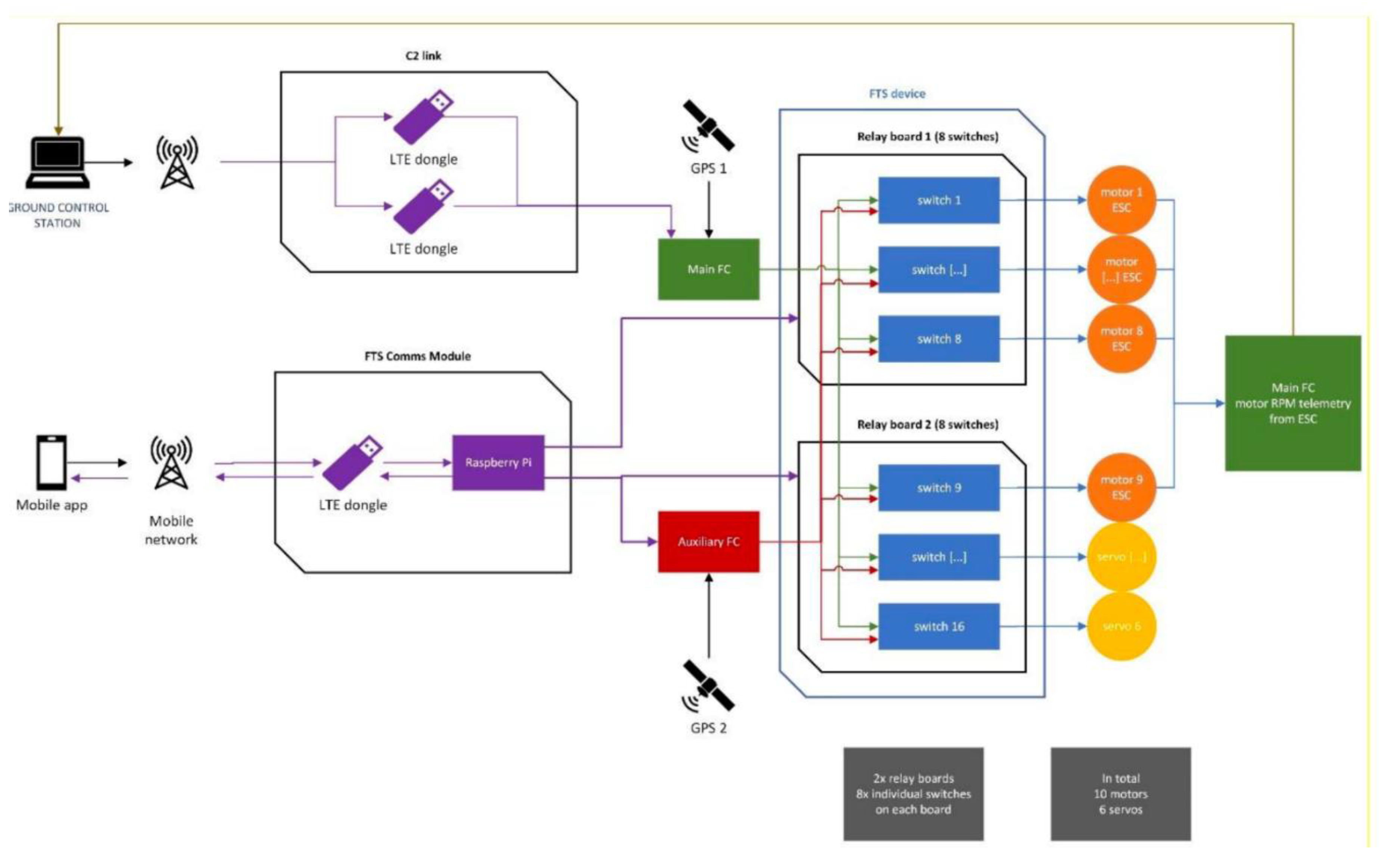

Functionality

The RPIC activates the FTS using a mobile phone app (segregated from the GCS).

The app sends the activation command through the mobile network to the FTS comms module installed on the aircraft (segregated from the C2 link and using a different network provider).

The FTS comms module activates the FTS device. Once activated, the FTS reroutes the motor and servo inputs to be controlled by the auxiliary Flight Controller which is pre-programmed to:

Stabilize and stop the aircraft in Hovering mode as quickly as possiblem(approx. 4G deceleration)

Navigate to the horizontal GPS location where the FTS was triggered in Hovering mode at slow speed (5m/s),

Turn into the wind using the weathervane function to let the Cruising motor help in countering the wind more efficiently,

Slowly descend at 3m/s or less until touchdown,

Disarm the aircraft.

The RPIC can disable the FTS at any time using the same FTS segregated trigger and regain full control of the aircraft (this is done only in case of inadvertent activation).

System Architecture

The FTS Comms module features an LTE dongle, to provide connectivity to the mobile network, and a Raspberry Pi, used to manage the connection to the mobile app trigger and send the activation command to the FTS device and the auxiliary FC. The Raspberry Pi transmits its status back to the mobile app, so that the connection to the FTS can be constantly monitored during operations. The main FC has access to all the sensors of the aircraft except for the GPS module 2. The auxiliary FC has access only to the GPS module 2 and its own built-in sensors (IMUs and barometer), all completely segregated from the sensors used by the main FC during normal operations. The FTS device is comprised of 16 switches on two relay boards. Each switch controls one motor or servo command line. Each switch input comes from either the Main or the Auxiliary Flight Controller, determining which of the FCs has command over the motors and the servos: in normal operations the Main FC has control, when the FTS is engaged the Auxiliary FC has control. The motors’ ESC output their telemetry data to the Main FC: their RPM individual values are displayed on the RPIC interface of the Ground Control Station. This functionality is used to verify the functionality of the FTS during the pre-flight checks.

Hardware details

FTS Device - Relay modules (2x)

Product link:

Technical data:

Relay switching current: approx. 8x60mA

Operating voltage: 3.3V to 5V

8x relay (switching power DC: max. 30V / 10A AC: max. 250V / 10A)

Relay with 3 contacts (change switch)

Direct control with microcontroller via digital output

Header pin for control RM 2.54mm

8x 3 screw terminals each for connecting the load

8x status LED for displaying the relay status

4x mounting holes 3mm

Size: 138 x 50 x 19mm

Weight: 105g

FTS Comms module – LTE Dongle

ZTE MF833V USB modem

Product link:

FTS Comms module – Raspberry Pi

Raspberry Pi Zero WH

Product link:

Technical data:

BCM 2835 SOC @ 1GHz

512MB RAM

On-board wireless LAN - 2.4 GHz 802.11 b / g / n (BCM43438)

On-board Bluetooth 4.1 + HS Low-energy (BLE) (BCM43438)

micro SD slot

mini HDMI type C connection

1x micro-B USB for data

1x micro-B USB for power supply

CSI Camera Connector (requires a separately available adapter cable)

Equipped 40-pin GPIO connector

Compatible with available pHAT / HAT add-on boards

Dimensions: 65 x 30 x 5mm

Auxiliary FC

Holybro Pixhawk 6C

Product link:

Processors & Sensors

FMU Processor: STM32H743

32 Bit Arm® Cortex®-M7, 480MHz, 2MB memory, 1MB SRAM

IO Processor: STM32F103

32 Bit Arm® Cortex®-M3, 72MHz, 64KB SRAM

On-board sensors

Accel/Gyro: ICM-42688-P

Accel/Gyro: BMI055

Mag: IST8310

Barometer: MS5611

Mechanical data

Dimensions: 84.8 * 44 * 12.4 mm

Weight (Plastic Case) : 34.6g

Other

Operating temperature: -40 ~ 85°c

Platform:

NVIDIA Jetson Xavier NX KI System-on-Modul, NVIDIA®

reComputer J202 - Carrier Board for Jetson Xavier NX/Nano/TX2 NX

3. Results

The comparative analysis of high-speed drone transportation versus traditional car transportation r evealed nuanced differences in the integrity and preanalytical parameters of blood samples across diverse weather conditions. A total of 27 analytes were assessed in serum samples, 20 in EDTA whole blood, 26 in Lithium-Heparin plasma, and 5 in Citrate plasma, encompassing a comprehensive spectrum of clinical markers.

Serum Samples (

Table 4): For serum samples transported via both drone and car, correlation coefficients (r) ranged from 0.830 to 0.998, indicating strong to perfect agreement between transportation method. Slopes varied from 0.947 to 1.023, demonstrating minimal deviations from unity. Notably, five analytes (total bilirubin, Calcium, Ferritin, Kalium, and Sodium) exhibited discrepancies between transported samples and negative controls, characterized by correlation coefficients lower than 0.800 and mean percentage differences outside the range of ±10%. However, no significant differences were observed between drone and car transportation modalities.

For EDTA Whole Blood (

Table 5), Citrate Plasma Samples (

Table 6), and Lithium-Heparin Plasma (

Table 7), similar patterns were observed. For EDTA Whole Blood, the slopes ranged from 0.960 to 1.158, and the correlation coefficients (r) ranged from 0.860 to 0.999. For citrate plasma samples the slopes ranged from 0.944 to 1.000 and the correlation coefficient (r) from 0.926 to 0.981. Lithium Heparin Plasma samples had slopes ranging from 0.938 to 1.077 and correlation coefficients (r) from 0.806 to 0.997.

Analyzing specific analytes within each sample type revealed a few discrepancies between transported samples (Natrium, Potassium) and reference controls, characterized by deviations in correlation coefficients and mean percentage differences. However, these discrepancies did not exhibit a consistent pattern across transportation modalities, with no significant differences observed between drone and car transportation methods.

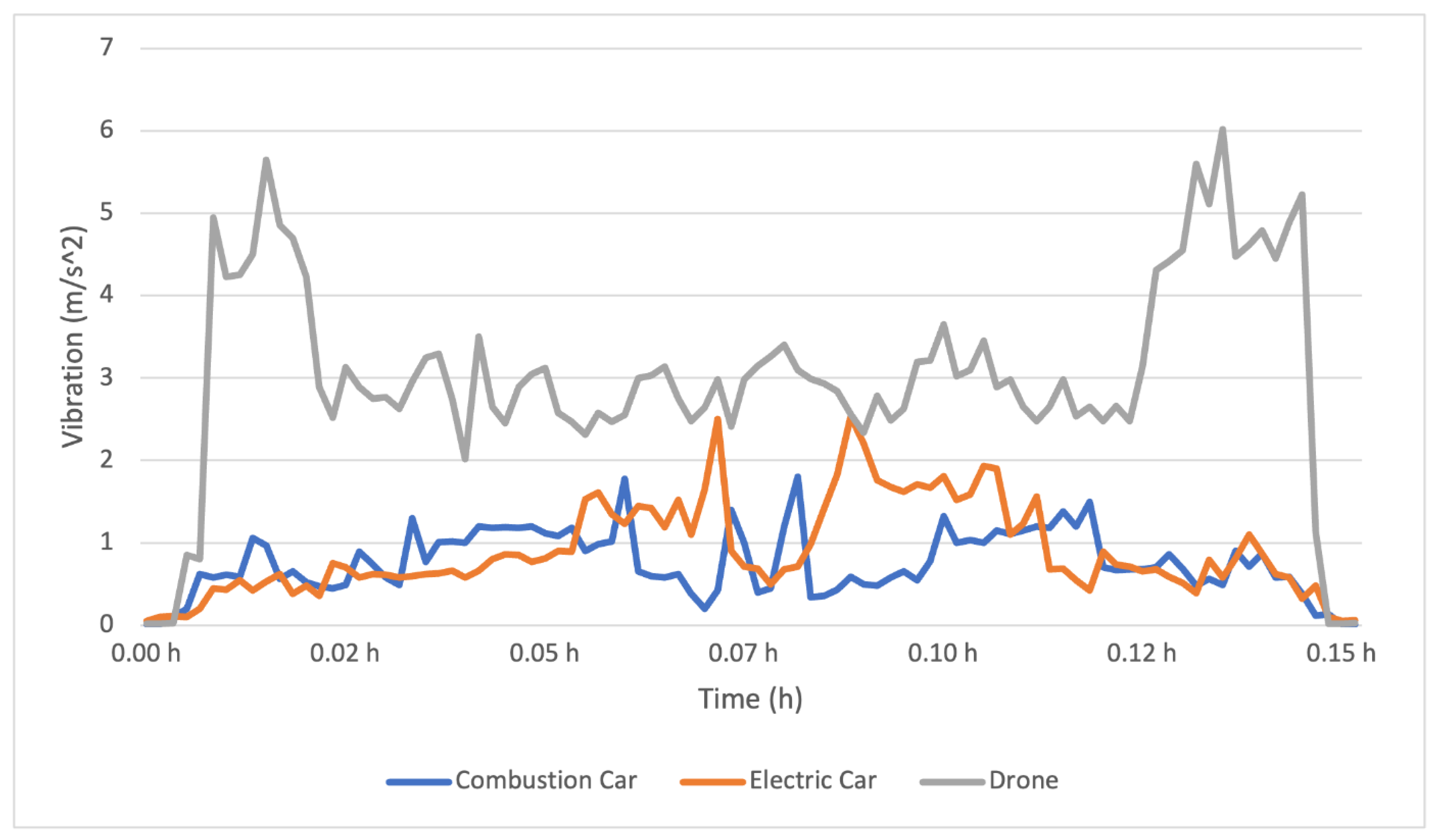

Accelerometer measurements showed higher vibrations with the drone, but without noticeable impact on sample integrity (

Figure 1).

Furthermore, sample temperature decreased by 4.3°C (from 20.0 to 15.7°C) at 0°C outside temperature at an altitude of 1800 meters above sea level (AMSL) and a flown distance of 31.8 km over 30 minutes of flight. At other altidues and higher outside temperatures the decrease in sample temperature was even less pronounced.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the feasibility and efficacy of high-speed drone transportation in the context of medical logistics, particularly concerning the transportation of sensitive blood samples. The results indicate that high-speed drone transportation maintains the integrity of blood samples as effectively as traditional car transportation, which has significant implications for the future of medical logistics.

The use of drones for transporting medical samples presents numerous advantages, especially in terms of speed and accessibility. Drones can bypass many of the logistical challenges faced by ground vehicles, such as traffic congestion, road conditions, and geographic barriers. This capability is particularly advantageous in remote or underserved areas where access to timely medical transportation is limited. The results of our study underscore that drones, despite the higher vibrations measured during transport, do not negatively impact the integrity of blood samples. Specifically, for serum samples, the correlation coefficient (r) ranged from 0.830 to 1.000, and the slopes varied from 0.913 to 1.111. Five analytes, including total bilirubin, Calcium, Ferritin, Kalium, and Sodium, showed discrepancies with correlation coefficients lower than 0.800, slopes not between 0.8 and 1.2, and mean percentage differences outside the range of ±10%. However, no significant differences were observed between drone and car transportation. This finding aligns with previous research that highlights the robustness of blood samples to vibrations experienced during transportation [

17].

Traditional car transportation has long been the standard for transporting medical samples, but it is not without its drawbacks. Factors such as traffic delays and route inefficiencies can compromise the timeliness of sample delivery. Our study shows that drones offer a comparable, if not superior, alternative to cars, particularly in urban areas with significant traffic congestion or rural areas with difficult terrain. For EDTA whole blood, Lithium-Heparin plasma, and Citrate plasma samples, similar patterns emerged. The correlation coefficients (r), when comparing drone versus car transportation, ranged from 0.829 to 0.997 for EDTA, 0.939 to 0.998 for Lithium-Heparin, and 0.830 to 1.000 for Citrate samples. The slopes ranged from 0.956 to 1.051 for EDTA, 0.938 to 1.085 for Lithium-Heparin, and 0.913 to 1.111 for Citrate samples. Analyzing specific analytes, a few discrepancies were identified, but no significant differences were observed between the transportation methods. This is supported by research from Rosser et al. (2018) [

18], who demonstrated the potential for drones to reduce delivery times significantly in healthcare logistics.

One of the critical aspects of blood sample transportation is maintaining a stable temperature to preserve sample integrity. Our study found that although the temperature of samples decreased during drone flights, the decrease was within acceptable limits. Specifically, sample temperature decreased by 4.3°C (from 20.0 to 15.7°C) at 0°C outside temperature at an altitude of 1800 meters above sea level and a flown distance of 31.8 km over 30 minutes of flight. This finding is consistent with the work of Sharma et al. (2019) [

19], who found that temperature fluctuations during drone transport did not adversely affect the quality of medical samples. Future drone designs could incorporate more advanced temperature control mechanisms to further ensure sample stability, even in extreme weather conditions.

The higher vibrations recorded during drone transportation did not result in significant discrepancies in analyte concentrations. This suggests that the design of drone transport containers can mitigate the effects of mechanical agitation or the vibrations itself are still too weak to influence the samples. Previous studies have also shown that while drones may experience higher levels of vibration compared to ground transportation, the impact on sample integrity is negligible when appropriate measures are taken [

20]. Accelerometer measurements showed higher vibrations with the drone but without noticeable impact on sample integrity.

The integration of drones into medical logistics has broader implications for healthcare delivery. By reducing transportation times and ensuring the rapid delivery of critical medical materials, drones can enhance the overall efficiency of healthcare systems. This is particularly important in emergency situations where time is of the essence [

8,

21,

22]. The ability to quickly deliver blood samples for diagnostic testing can expedite treatment decisions and improve patient outcomes. Additionally, drones can play a crucial role in disaster response scenarios, where traditional transportation infrastructure may be compromised [

23,

24].

While the potential benefits of drone transportation are clear, several regulatory and practical considerations must be addressed to facilitate widespread adoption. Regulatory frameworks need to be developed to ensure the safe and ethical use of drones in medical logistics. Issues such as airspace management, privacy concerns, and public acceptance must be carefully navigated. Collaborative efforts among policymakers, regulatory agencies, healthcare providers, and technology developers will be essential to establish clear guidelines and standards for drone operations in healthcare settings.

Future research should focus on optimizing drone design and payload capacity to accommodate a broader range of medical materials and sample volumes. The implementation of real-time monitoring systems and predictive analytics algorithms could enhance the resilience and adaptability of drone operations, allowing for proactive adjustments in response to changing environmental conditions. Additionally, studies should explore the cost-effectiveness and scalability of drone transportation compared to traditional methods, considering factors such as maintenance, operational costs, and environmental impact.

Limitations: While efforts were made to simulate real-world conditions and mitigate confounding factors, certain limitations inherent to the study design should be acknowledged. Variability in environmental conditions and logistical constraints may introduce inherent biases and limit the generalizability of findings. Additionally, the study focused primarily on analytical outcomes and may not capture broader considerations such as cost-effectiveness and scalability of transportation modalities.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate that high-speed drone transportation of blood samples does not significantly alter analyte concentrations when compared to traditional car transportation. Any observed discrepancies between transported samples and reference controls were attributed to the transportation process itself rather than the mode of transportation. This underscores the potential of drone technology to enhance the efficiency and reliability of medical sample transport, particularly in scenarios requiring rapid and reliable delivery for timely diagnosis and treatment. Moving forward, continued research, innovation, and collaboration will be essential to harness the full transformative potential of drones in healthcare delivery and logistics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S, L.R and M.R.; methodology, N.S, L.R.; formal analysis, N:S.; resources, L.R and M.R; data curation, N.S and F.L.; writing—original draft preparation, N.S.; writing—review and editing, N.S, L.R, F.L and M.R.; visualization, N.S.; supervision, L.R.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our deepest gratitude to all those who contributed to this research. Our heartfelt thanks to the laboratory personnel and transportation service providers in the Principality of Liechtenstein and Switzerland for their invaluable support and cooperation during the data collection phase. Special thanks to Loren Risch and Martin Rach for their unwavering guidance and expertise. We are also grateful to the environmental experts and stakeholders who participated in our workshops, offering their insights and helping us prioritize the criteria for evaluating transportation modalities. Their contributions were crucial in shaping the direction and scope of this study. Our appreciation goes to the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) for providing the established methodologies and tools necessary for the accurate calculation of CO2 footprints. The technical and logistical support received from various institutions and organizations was instrumental in the successful completion of this research. Lastly, we thank our families and friends for their constant encouragement and understanding throughout this journey. Without their support, this work would not have been possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Sigari, Cyrus, and Peter Biberthaler. "Medical drones: Disruptive technology makes the future happen." Der Unfallchirurg 124.12 (2021): 974.

- Zailani, Mohamed Afiq Hidayat, et al. "Drone for medical products transportation in maternal healthcare: A systematic review and framework for future research." Medicine 99.36 (2020): e21967.

- George, ANANYA ELIZABETH. "Employment of drones in medical, emergency and relief settings." International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Science, 5 (1) (2017): 21-27.

- Wulfovich, Sharon, Homero Rivas, and Pedro Matabuena. "Drones in healthcare." Digital Health: Scaling Healthcare to the World (2018): 159-168.

- Oigbochie, A. E., E. B. Odigie, and B. I. G. Adejumo. "Importance of drones in healthcare delivery amid a pandemic: Current and generation next application." Open Journal of Medical Research (ISSN: 2734-2093) 2.1 (2021): 01-13.

- Yakushiji, Koki, et al. "Short-range transportation using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) during disasters in Japan." Drones 4.4 (2020): 68.

- Konert, Anna, Jacek Smereka, and Lukasz Szarpak. "The use of drones in emergency medicine: practical and legal aspects." Emergency medicine international 2019.1 (2019): 3589792.

- Johnson, Anna M., et al. "Impact of using drones in emergency medicine: What does the future hold?." Open Access Emergency Medicine (2021): 487-498.

- Wolfe, Mary K., Noreen C. McDonald, and G. Mark Holmes. "Transportation barriers to health care in the United States: findings from the national health interview survey, 1997–2017." American journal of public health 110.6 (2020): 815-822.

- Weiss, D. J. , et al. "Global maps of travel time to healthcare facilities." Nature medicine 26.12 (2020): 1835-1838.

- Poljak, Mario, and A. J. C. M. Šterbenc. "Use of drones in clinical microbiology and infectious diseases: current status, challenges and barriers." Clinical Microbiology and Infection 26.4 (2020): 425-430.

- Demuyakor, John. "Ghana go digital Agenda: The impact of zipline drone technology on digital emergency health delivery in Ghana." Humanities 8.1 (2020): 242-253.

- Tarr, Anthony A., et al. "Drones—healthcare, humanitarian efforts and recreational use." Drone Law and Policy. Routledge, 2021. 35-54.

- González-Domínguez, Raúl, et al. "Recommendations and best practices for standardizing the pre-analytical processing of blood and urine samples in metabolomics." Metabolites 10.6 (2020): 229.

- Gerber, Teresa, et al. "Assessment of pre-analytical sample handling conditions for comprehensive liquid biopsy analysis." The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics 22.8 (2020): 1070-1086.

- Thuile, Katharina, et al. "Evaluation of the in vitro stability of direct oral anticoagulants in blood samples under different storage conditions." Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation 81.6 (2021): 461-468.

- Amukele, T. K. , Sokoll, L. J., Pepper, D., Howard, D. P., & Street, J. (2017). Can unmanned aerial systems (drones) be used for the routine transport of chemistry, hematology, and coagulation laboratory specimens?. PLOS ONE, 12(7), e0180183.

- Rosser, J. C. , Vignesh, V., Terwilliger, B. A., & Parker, B. C. (2018). Surgical and medical applications of drones: a comprehensive review. JSLS: Journal of the Society of Laparoscopic & Robotic Surgeons, 22(3).

- Sharma, A. , Kwon, J., Ravichandran, N., & Park, S. (2019). Evaluation of blood sample transportation using small drones. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (CCLM), 57(12), 1778-1785.

- Amukele TK, Sokoll LJ, Pepper D, Howard DP, Street J (2015) Can Unmanned Aerial Systems (Drones) Be Used for the Routine Transport of Chemistry, Hematology, and Coagulation Laboratory Specimens? PLoS ONE 10(7): e0134020. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Nathan B., et al. "Current summary of the evidence in drone-based emergency medical services care." Resuscitation Plus 13 (2023): 100347.

- Zailani, M. A. , et al. "Drone versus ambulance for blood products transportation: an economic evaluation study." BMC health services research 21 (2021): 1-10.

- Anand, R. , et al. "Emergency Medical Services Using Drone Operations in Natural Disaster and Pandemics." Inventive Communication and Computational Technologies: Proceedings of ICICCT 2021. Springer Singapore, 2022.

- Sivasuriyan, V. "Drone usage and disaster management." Bodhi Int. J. Res. Humanit. Arts Sci 5 (2021): 93-97.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).