Submitted:

10 March 2025

Posted:

11 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- High Operational Costs: The employment of field personnel in collecting data means higher salary, transportation, and administrative overhead costs. These costs rise even more during the deployment of personnel in difficult geographical terrains or areas that are highly inhabited by people.

- Safety Risks to Personnel: Deployment of human workers in hazardous environments, such as unstable infrastructures, extreme weather conditions, and insecurity is a huge safety risk to personnel. Manual data collection exposes personnel to accidents, injuries, and health hazards.

- Data inaccuracies and delays: Most data intake mechanisms worked manually are invariably prone to human inaccuracies, further bringing down the accuracy of the consumption readings. Besides that, the time it takes for the actual collection of data manually from a large number of locations inherently makes data availability delayed and limits the real value of real-time monitoring and analysis.

- Recent developments in Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV), or drone, technology have opened exciting vistas in use for transforming many industries and sectors, including urban infrastructure management. Indeed, UAVs inherently offer a very attractive alternative to manual data collection in SMI for several reasons [4,14,15,16,17,18]:

- Agility and Maneuverability: It can navigate through complicated urban environments to reach places where it is hard or dangerous for human personnel. Their agility to move through narrow spaces and to fly at different altitudes favors them as an optimal choice for data acquisition in a wide range of settings.

- Scalability and Cost-Effectiveness: The deployment of a swarm of inter-connected UAVs will have the added advantage of rapid data collection in a very short time from a large number of smart meters deployed within a wide area. Such a scalable solution reduces the time and cost required for manual data gathering considerably.

- Reduced Safety Risks: The use of UAVs in data collection will reduce the need to deploy personnel in hazard-prone environments, and by doing so it reduces accidents, injuries, or health hazards to workers significantly.

- Improved Data Accuracy and Timeliness: Equipped with appropriate sensors, UAVs would be able to download data directly from smart meters with no potential human error from manual entry. Besides, rapid deployment and data transmission by UAVs provide real-time monitoring and analysis in a timely manner.

2. Related Work

- To design and develop a comprehensive SMI architecture based on a self-organizing UAV swarm for efficient and reliable data collection from smart meters. This architecture encompasses the design of key components (DMC and UAV swarm), communication protocols, and operational phases for seamless data acquisition.

- While existing research highlights the potential of UAV swarms for smart metering, there is a critical need to address the unique security challenges posed by these interconnected systems. This paper aims to bridge this gap by conducting a comprehensive security analysis of a UAV swarm-based SMI, identifying key threats across different operational phases, and proposing a multi-phased security model to mitigate these vulnerabilities. We will analyze potential attacks targeting the Data Management Center (DMC), individual drones, and communication links, developing tailored security protocols, authentication mechanisms, and countermeasures for each phase. Through rigorous evaluation, we will assess the effectiveness of our proposed solutions in mitigating specific attack types, comparing their strengths and limitations against existing approaches.

3. System Design and Architecture

3.1. System Overview

3.2. Data Management Center (DMC)

- Mission Planning and Configuration: Human operators interact with the DMC to define mission parameters, such as the target area for data collection, desired swarm formation, data collection frequency, and any specific waypoints or flight paths the swarm should follow.

- Swarm Configuration and Management: The operator selects the number of SDs to deploy, assigns a specific drone as the LD, and monitors the status of individual drones within the swarm through a user-friendly interface.

- Data Processing and Analysis: The DMC receives data collected by the UAV swarm, processes it to extract relevant information, performs analysis to identify consumption patterns or anomalies, and generates reports for further action or decision-making.

- Communication and Interfacing: The DMC establishes communication links with the LD using a reliable wireless communication protocol. It also interfaces with external systems, such as utility company databases or energy management platforms, to share data and facilitate integration with existing infrastructure.

3.3. UAV Swarm: Leader Drone (LD) and Slave Drones (SDs)

3.3.1. Leader Drone (LD)

- Receiving Mission Instructions: The LD receives detailed mission parameters from the DMC, including GPS waypoints, desired swarm formation, and data collection instructions.

- Relaying Instructions to SDs: The LD disseminates mission instructions received from the DMC to the SDs, ensuring synchronized swarm movements and task execution.

- Monitoring Swarm Status: The LD continuously monitors the status of individual SDs, including battery levels, location, and sensor readings. It relays this information back to the DMC for real-time situational awareness.

- Aggregating Data from SDs: As SDs collect data from smart meters, they transmit it to the LD, which aggregates the data from all SDs and periodically transmits it back to the DMC for processing and analysis.

3.3.2. Slave Drones (SDs)

- Following LD Instructions: SDs receive and execute instructions from the LD, maintaining formation during flight, deploying to specific locations, and initiating data collection sequences.

- Data Collection from Smart Meters: SDs are equipped with appropriate sensors to collect data from smart meters. This may involve optical character recognition (OCR) to read data from traditional meters or wireless communication protocols to interface with smart meters directly.

- Transmitting Data to the LD: Once data is collected, SDs transmit it wirelessly to the LD for aggregation and eventual transmission to the DMC.

3.4. Communication Protocols and Data Exchange

- DMC to LD Communication: We propose utilizing a robust wireless communication protocol, such as 4G/LTE or potentially 5G in areas with coverage, for communication between the DMC and the LD. This ensures a stable connection with sufficient bandwidth for transmitting mission data and receiving status updates and aggregated data from the swarm.

- LD to SD Communication: For communication between the LD and SDs, a suitable wireless local area network (WLAN) protocol, such as Wi-Fi or Zigbee, can be employed. These protocols offer high data rates, low latency, and energy efficiency, essential for maintaining swarm coordination and exchanging data effectively.

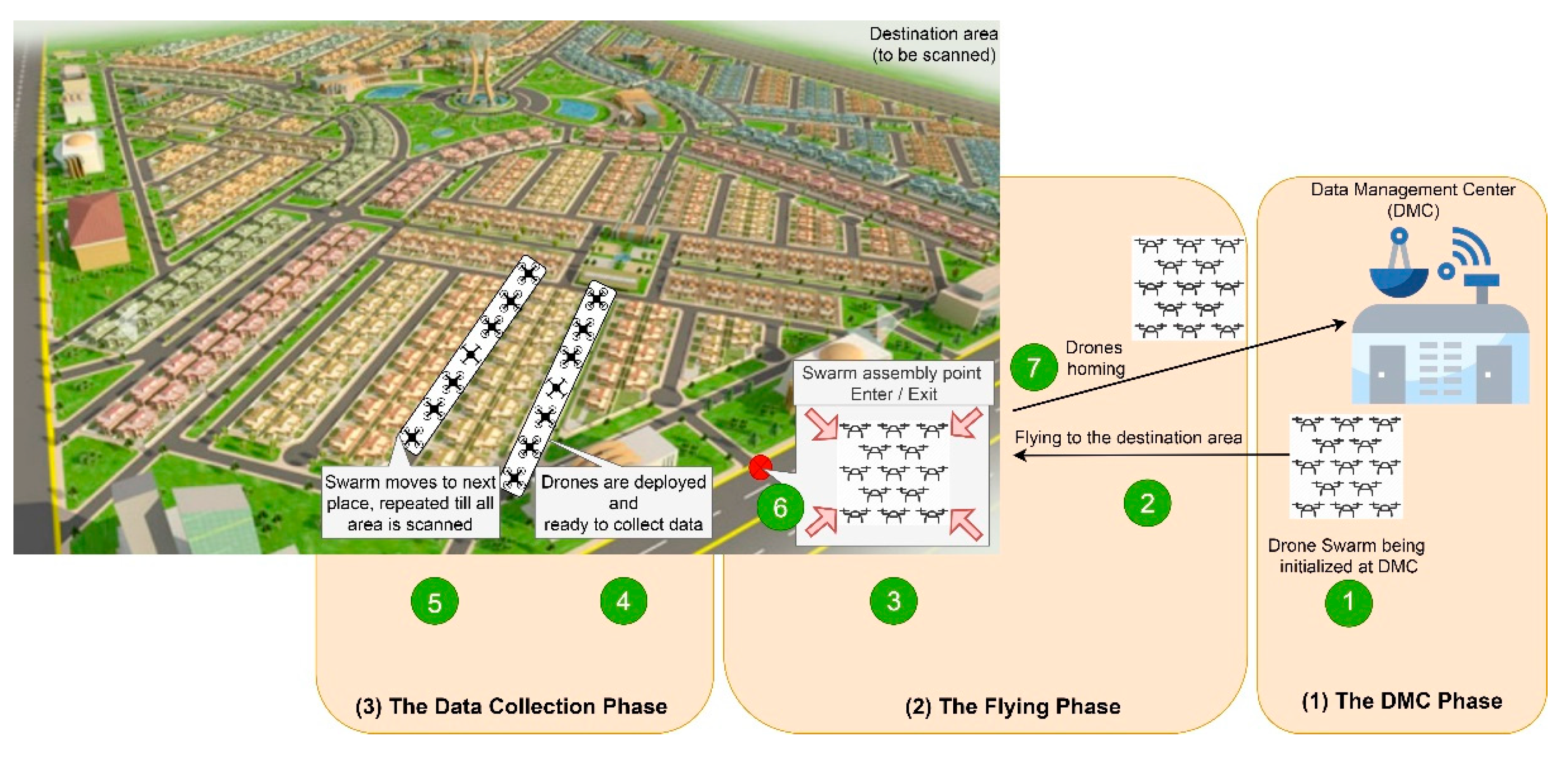

3.5. Operational Phases

3.5.1. DMC Phase (Initialization and Configuration)

- Swarm Power-Up: The operator powers up the required number of SDs and the designated LD.

- Connection Establishment: The LD establishes a secure connection with the DMC, and the SDs connect to the LD, forming the swarm network.

- Mission Information Upload: The operator defines mission parameters (e.g., target GPS coordinates, swarm formation, data collection frequency) through the DMC interface. The DMC transmits this information to the LD.

- SD Configuration: The LD receives the mission information and configures each SD with its specific role and tasks for the mission.

3.5.2. Flying Phase (Transit and Formation)

- Swarm Launch: Upon receiving the launch command from the DMC, the LD initiates takeoff, followed by the SDs.

- Formation Establishment: The LD guides the SDs to form the pre-defined swarm formation (e.g., linear, grid) while navigating towards the target area.

- Waypoint Navigation: The LD, following the designated flight path and waypoints, leads the swarm to the target location for data collection. The SDs maintain their relative positions within the formation throughout the flight.

3.5.3. Data Collection Phase (Deployment and Sensing)

- Target Area Arrival: The LD, upon reaching the designated target area, signals the SDs to prepare for deployment.

- SD Deployment: The SDs autonomously deploy to their assigned locations within the target area, following a pre-defined deployment strategy to ensure efficient coverage of smart meters.

- Data Acquisition: SDs activate their onboard sensors and collect data from the designated smart meters. The data collected may include energy consumption readings, voltage levels, and other relevant parameters.

- Data Transmission to LD: Each SD transmits its collected data wirelessly to the LD for aggregation.

- LD Aggregation and Transmission to DMC: The LD aggregates the data received from all SDs and periodically transmits it back to the DMC using the established long-range communication link.

- Mission Completion and Return: Upon receiving confirmation from the DMC that sufficient data has been collected, the LD initiates the swarm's return to the launch site, maintaining formation throughout the flight back.

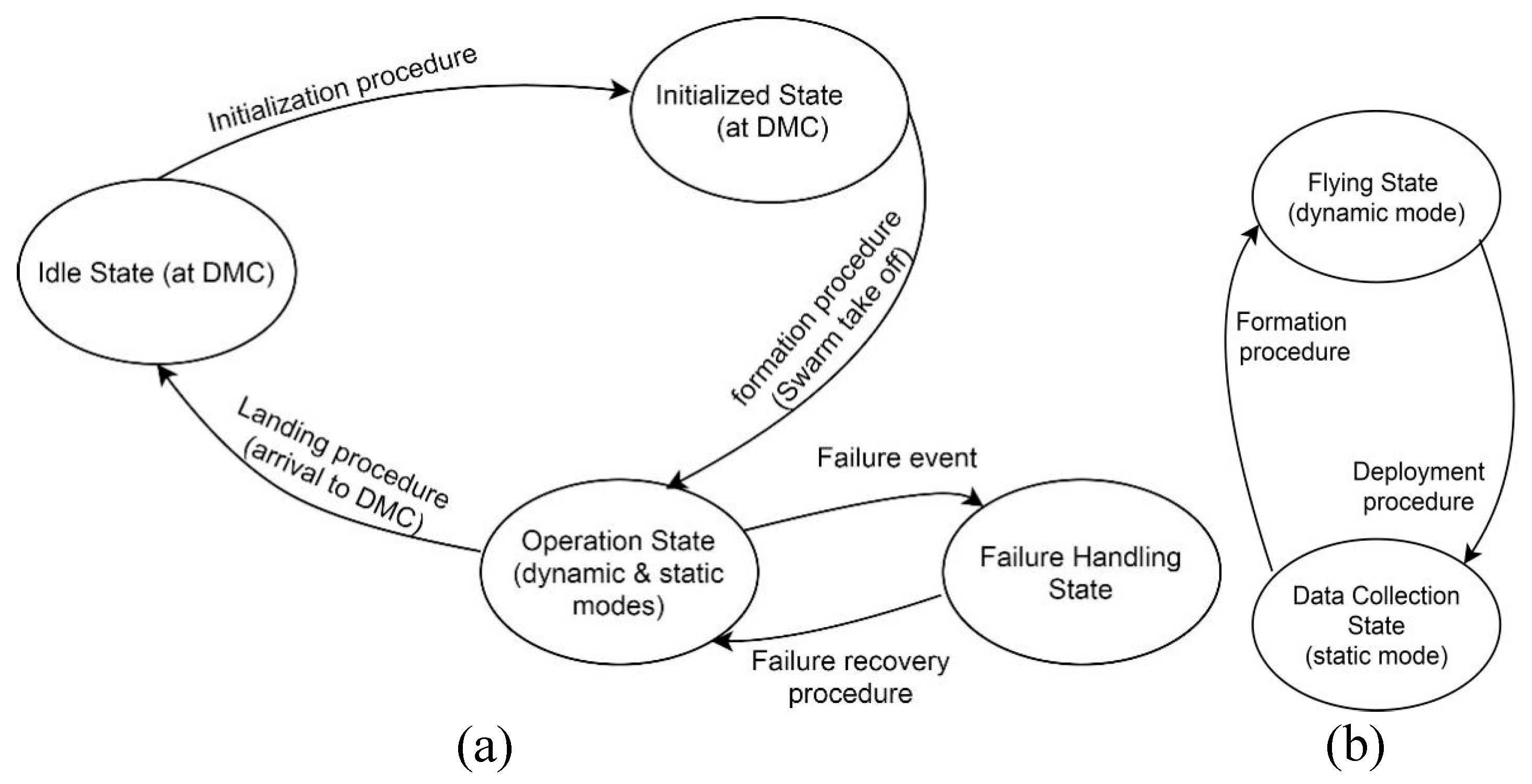

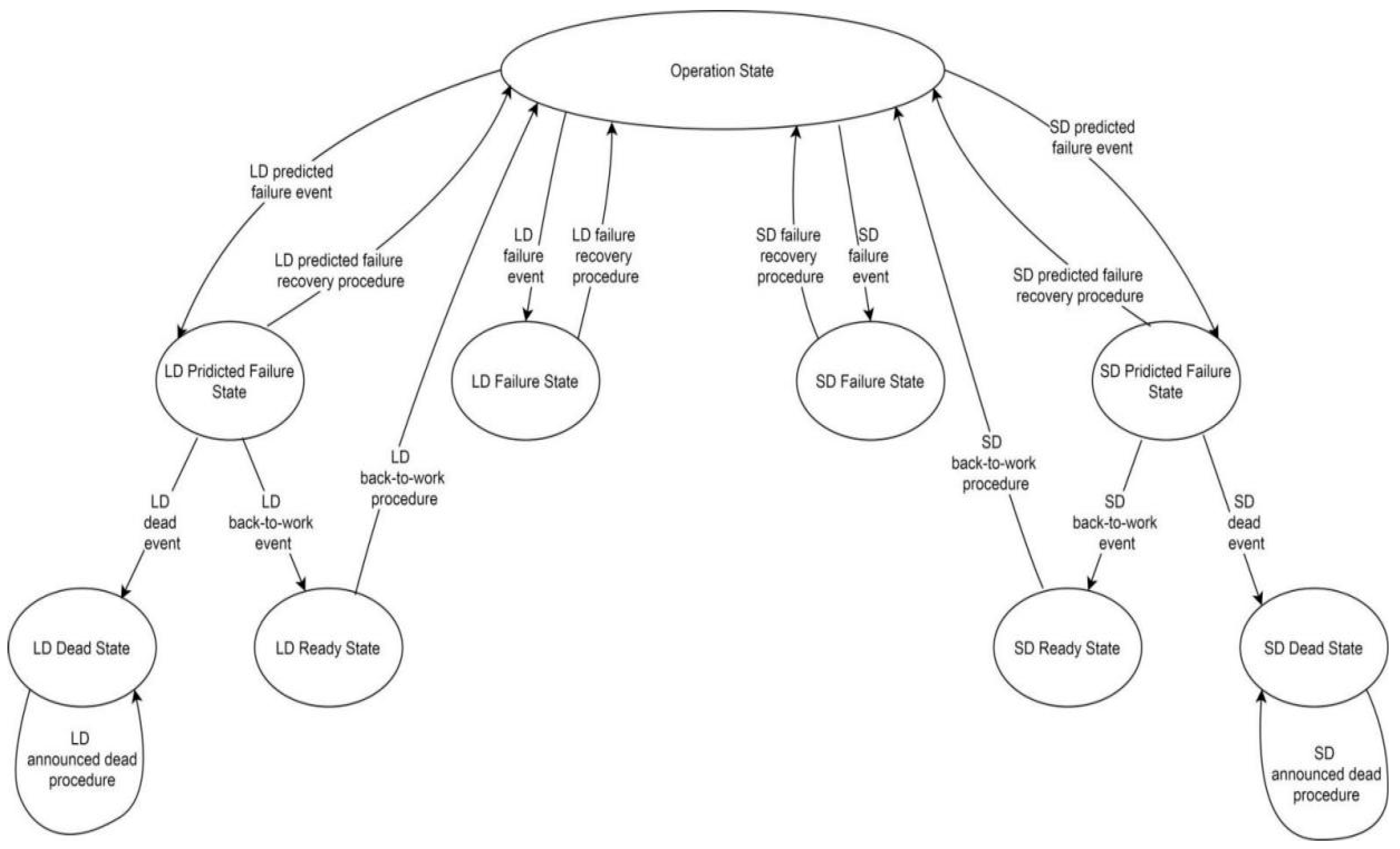

4. Ensuring System Reliability: Robust Failure Handling

4.1. Leader Drone (LD) Failure Handling

- Backup LD Designation: During the initialization phase, the operator designates a specific SD as the backup LD. This backup LD possesses all the capabilities of the primary LD and remains on standby throughout the mission.

- Hard Handover (Immediate LD Failure): In the event of a sudden and unexpected LD failure (e.g., collision, loss of communication), the backup LD immediately takes over the leadership role. It assumes responsibility for swarm coordination, data aggregation, and communication with the DMC, ensuring minimal disruption to the mission.

- Soft Handover (Predicted LD Failure): To further enhance resilience, we introduce a novel failure prediction mechanism. The LD continuously monitors its onboard sensors (e.g., battery level, temperature) and can predict potential failures in advance. If the LD anticipates a failure, it initiates a soft handover process, transferring leadership to the designated backup LD before the failure occurs. This proactive approach allows for a smoother transition and potentially extends the operational life of the failing LD by allowing it to enter a power-saving mode.

4.2. Slave Drone (SD) Failure Handling

- Dynamic Task Reallocation: If an SD fails or becomes unresponsive, the LD dynamically reassigns its tasks to other available SDs within the swarm. This ensures that all designated smart meters are covered, maintaining data collection continuity.

- Failure Isolation: The LD isolates the failed SD from the swarm network to prevent potential communication interference or disruption to other operational drones.

- Optional Return to Base: Depending on the severity of the failure and mission parameters, the LD can instruct the failed SD to return to the base station autonomously for maintenance or replacement.

4.3. Environmental Disturbance Mitigation

- Robust Formation Control Algorithm: The swarm utilizes a robust formation control algorithm that considers environmental factors and adjusts drone positions and movements dynamically to maintain formation integrity and prevent collisions.

- Onboard Sensors for Obstacle Avoidance: Each drone is equipped with onboard sensors (e.g., cameras, ultrasonic sensors) to detect and avoid obstacles autonomously, ensuring safe navigation through complex urban environments.

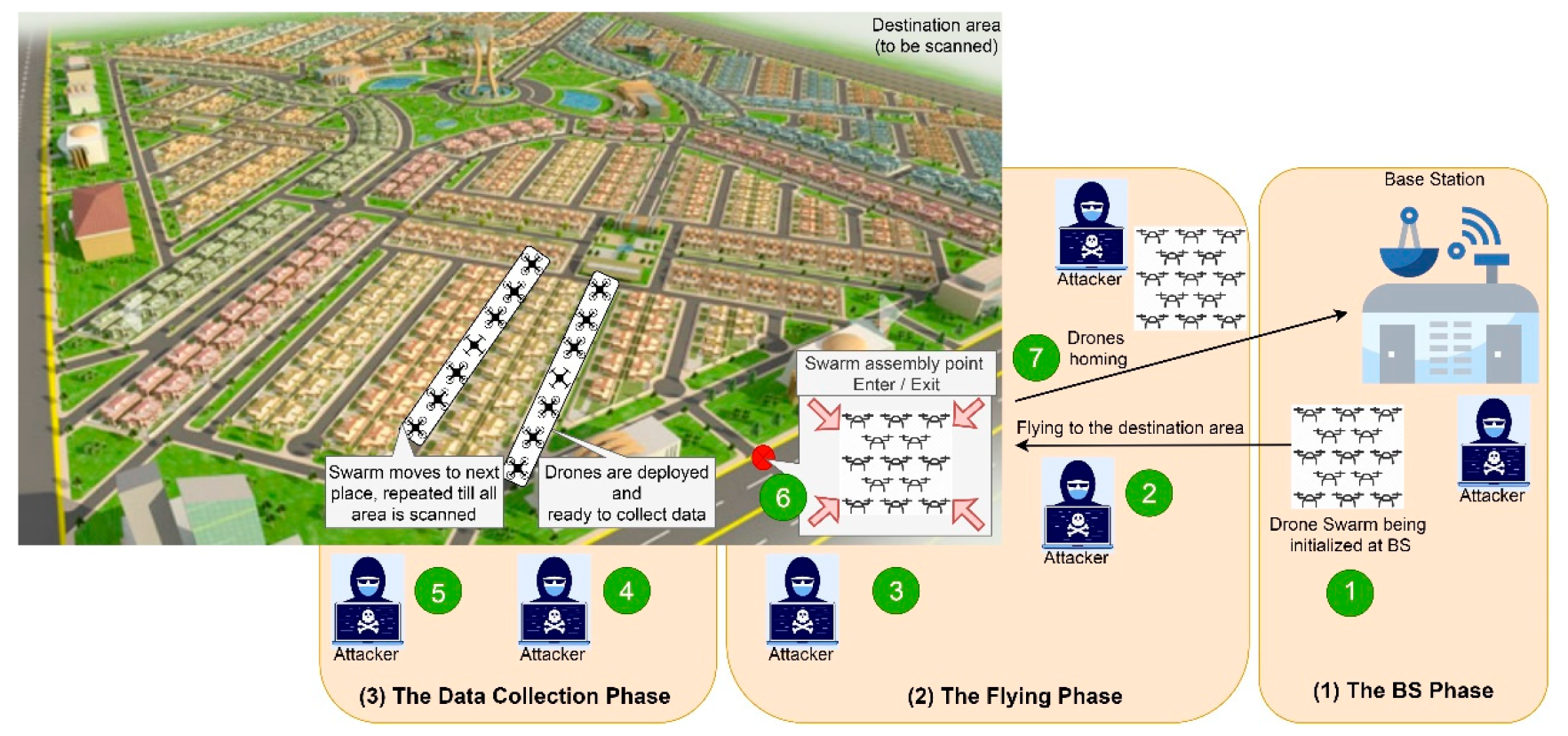

5. The Proposed System Security Model

5.1. Swarm Mission Roadmap and Phases

- The DMC Phase: Includes swarm member selection and initialization before launching the operation (pre-operation procedure) as well as swarm member inspection after returning from a mission (post-operation procedure).

- The Flying Phase: Comprises the swarm flight from the DMC to the destination area and vice versa, the moving from one place to another within the destination area, and the formation/deployment procedures.

- The Data Collection Phase: In this phase, data is collected as the drones stay stationary with no mobility, either hovering or landing.

5.2. Security Analysis and Countermeasures

5.3. The Threat Model

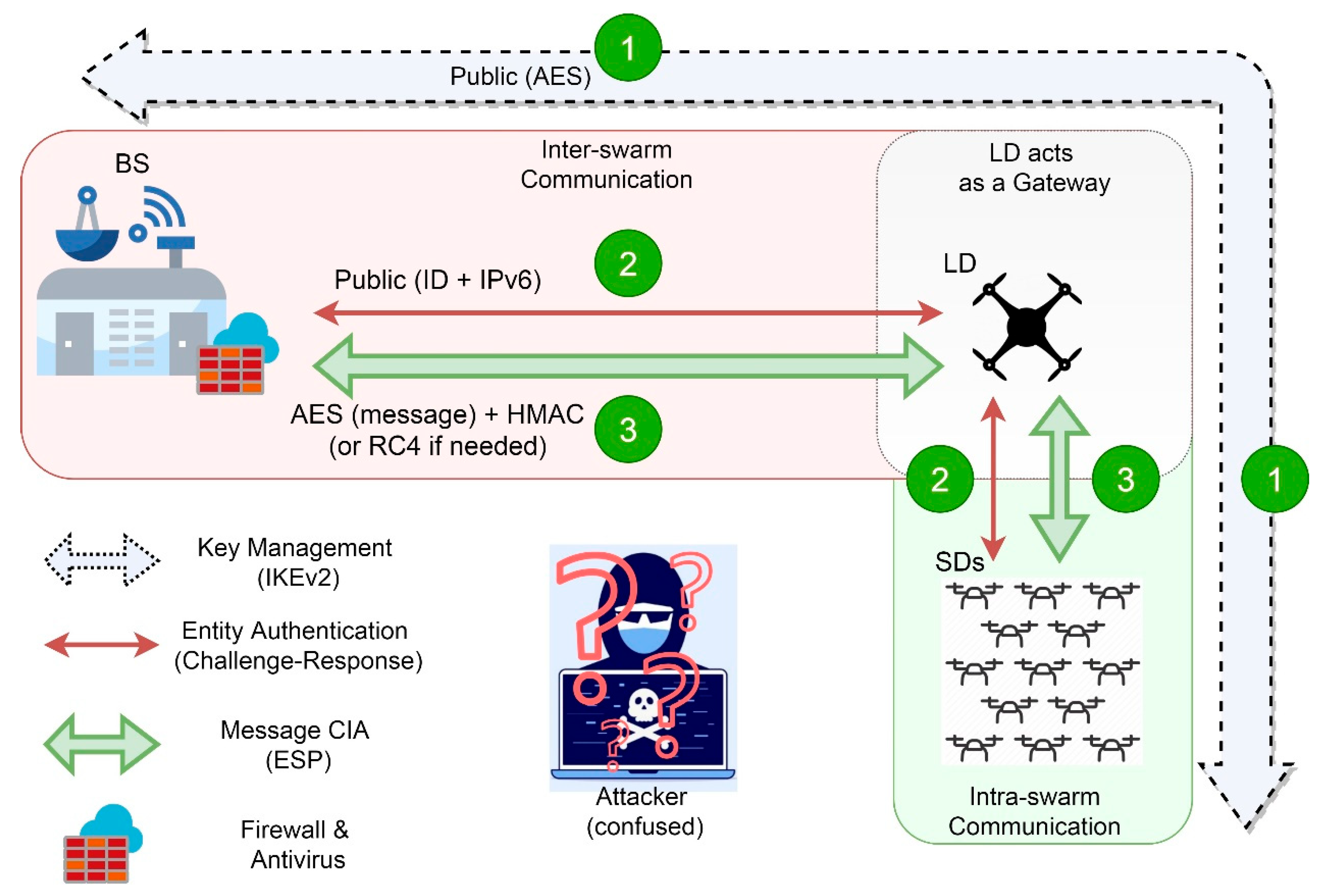

5.4. The Network Security Model

- Bidirectional entity authentication between the DMC server and the LD and also between the LD and other SDs.

- All the transferred packets, i.e. the transactions among swarm nodes and the DMC, are encrypted and sent along with their Hash-based Message Authentication (HMAC) to achieve message confidentiality, integrity, and authentication. The Internet Protocol Security (IPSec), explained in detail in the coming sub-section, is adopted for this purpose.

- Implementing a suitable firewall solution.

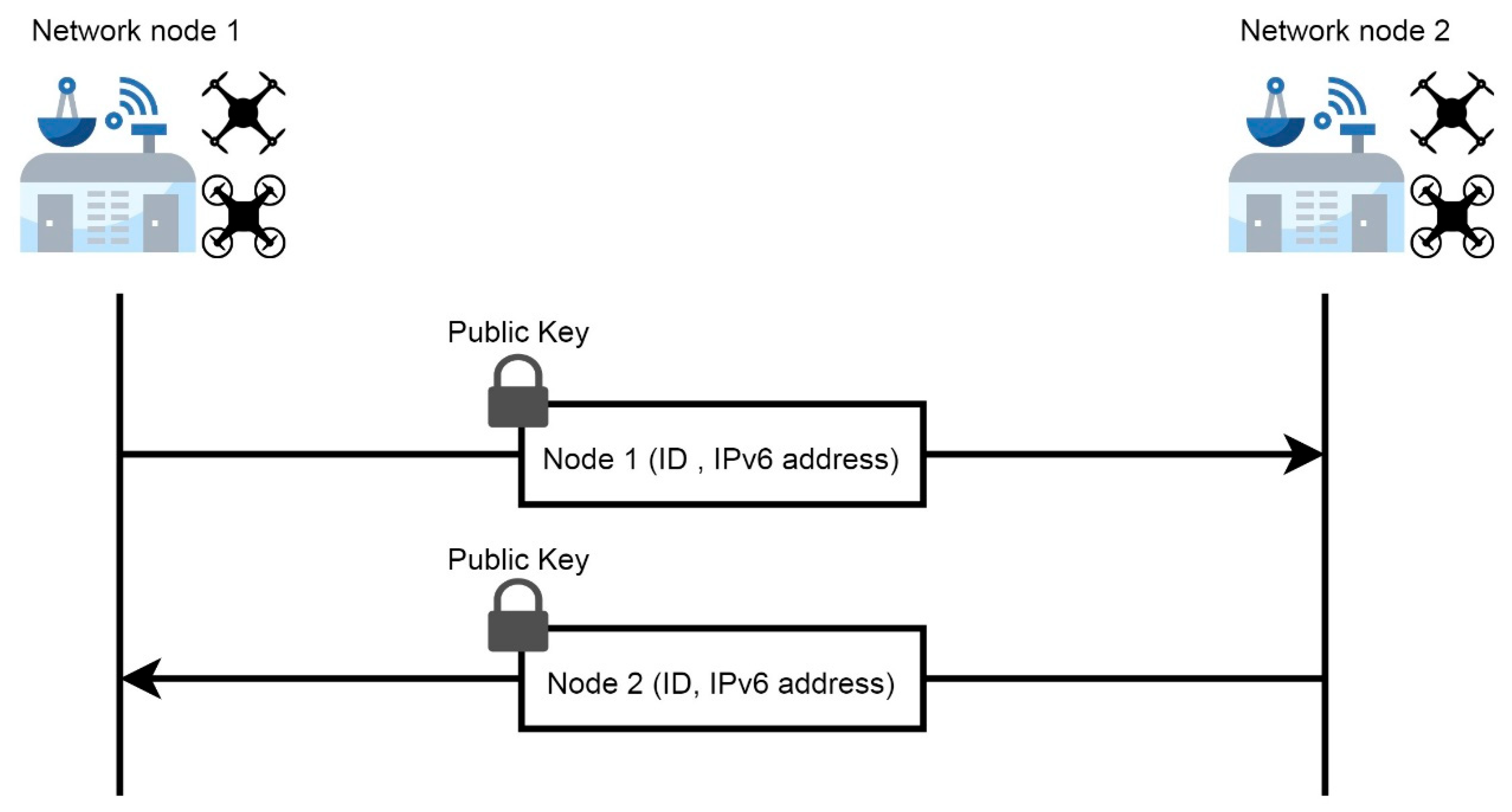

5.4.1. Bidirectional Entity Authentication

- The challenge/response messages are encrypted using the other end’s public key, so no node can decrypt the message unless it has the associated private key.

- When decrypting the message, the node ID is considered another identity proof of the sender.

- Also, the sender has a unique IPv6 address which can be extracted when decrypting the message, and it also proves the identity of the sender.

- The procedure is bidirectional and the same procedure is repeated for the other node. Additionally, when the receiver accepts the challenge and replies with a response, this is another proof of its identity.

5.4.2. Bidirectional Message Confidentiality, Integrity, and Authentication

- IPSec Mode: This is considered to work in the tunneling mode for all the system connections acting as a Virtual Private Network (VPN) between each pair of nodes. The reason behind this is not to only encrypt the IPSec header and payload for a packet but also to allow the IPv6 header to be encrypted as well, which provides a better information-hiding for security purposes. In tunnel mode, the (inner) IP header carries the ultimate addresses for the source and destination, whereas an (outer) IP header may contain specific IP addresses, e.g. addresses of security gateways.

- IPSec Type: The Encapsulating Security Payload (ESP) protocol type of IPSec is selected to provide security features that are implemented in all communicating peers, thus, protecting the whole session. ESP provides many services including; data confidentiality, data origin authentication and message integrity, anti-replay service, and Key management.

- Data Confidentiality: This could be provided by using 128-bit AES keys, as mentioned earlier, as a block cipher. However, if the system application contains data streaming as in the proposed SMI system, e.g. video call, then a stream ciphering should be used to provide data encryption, refer to Table 3. We suggest using the 128-bit Rivest Cipher 4 (RC4) algorithm as a lightweight and fast stream ciphering approach that offers a reasonable level of confidentiality to encrypt the transmitted streaming packets among system nodes.

- Data Origin Authentication and Message Integrity: This could be achieved by using a Hashed Message Authentication Code using HMAC-SHA1 where the combination of the message and the AES key is hashed and yields the intermediate Message Authentication Code (MAC) that is hashed again with the same key to generate the HMAC. Finally, before data transmission, the resulting HMAC is appended to the encrypted message.

- Anti-replay Service: This is an IPSec built-in feature and could be enabled which adds an IPSec sequence number to differentiate messages and prevent anti-replay attacks.

- Key Management: This is provided in IPSec through the Internet Key Exchange (IKE) protocol. We suggest using one pair of public-private keys for each network node, see Table 3, IKE version 2 (IKEv2) is the version of choice as it supports mobility, maintains the form of IKEv1, and designs the connection process more simply and quickly [34]. IKEv2 uses several cryptographic algorithms to deliver its function, including four transform types; encryption algorithm, integrity algorithm, Diffie-Helman Groups, and pseudorandom functions [35].

- Renewing Cipher Keys: This could be achieved by assigning SAs a certain lifetime for the specified set of keys.

5.4.3. The System Phases and Specific Security Procedures

- The DMC Phase:

- Pre-operation Launch: In this scenario, the drone swarm operator performs an identity check for system nodes before authentication, then configures the SAD for each network node so it will have the required sets of keys, i.e. AES key pair and RC4 (if any), that might be renewed during the mission for each phase and also while swarm repositioning when collecting readings in the field. After that, the mission information file, which contains all required information for the mission completion such as a list of GPS coordinates as waypoints, is encrypted and uploaded to the LD, which in turn sends the required information to each swarm member.

- Post-operation Completion: After drone swarm homing and landing in the DMC, an identity inspection for each UAV is done to ensure that neither a legitimate UAV nor a malicious UAV has joined the swarm. Also, all stored readings are uploaded to the server and all security keys are erased from the SAD.

- 2.

- The Flying Phase

- Renewing Cipher Keys: The AES and RC4 keys should be renewed, i.e. calling for a new key set from the SAD, before each flight.

- Periodic Entity Authentication: Entity check should be performed periodically using the suggested entity authentication mechanism, refer to Figure 6, during the flight.

- 3.

- The Data Collection Phase:

- Renewing Cipher Keys: The AES and RC4 keys should be renewed periodically, i.e. retrieving a new key set from the SAD, after each landing.

- Periodic Entity Authentication: This procedure should be carried out before transferring any sensitive data using the suggested entity authentication approach, refer to Figure 6.

5.4.4. The Security Solutions Assessment

6. Performance and Overhead Analysis

6.1. Model Derivation

- Computational Overhead (Time): The total time of cryptographic operations (O_c) can be calculated by multiplying the time per operation (t_c), the frequency of operations (f_c), and the total mission time (T_mission) as shown:

- 2.

- Communication Overhead (Time): Likewise, the time spent on security-related communication (O_comm) can be found by multiplying the time per message transmission (t_comm), the frequency of transmissions (f_comm), and the mission time as given:

- 3.

- Total Time Overhead: Summing the computational and communication overheads yields the total time overhead (O_total) as illustrated:

- 4.

- Computational Overhead (Energy): Similar to the time overhead, the energy consumed by cryptographic operations (E_comp) is calculated using energy per operation (E_c) instead of time as shown:

- 5.

- Communication Overhead (Energy): Similarly, the energy consumed by communication (E_comm_total) is calculated using energy per message (E_comm) as shown:

- 6.

- Total Energy Overhead: The sum of computational and communication energy expenditures gives the total energy overhead (E_total) as given:

- 7.

- Feasible Mission Time: The feasible mission time (T_feasible) is calculated by dividing the battery capacity (B) by the total power consumption (base power (P_base) added to the average power overhead) as shown:

- 8.

- Swarm Impact (Communication): The communication overhead is affected by the swarm size (n). To model the increased communication burden as the swarm grows, a scaling factor (α) that represents the proportion of communication overhead related to the number of other UAV groups is introduced. We assume the leader drone (LD) handles aggregation efficiently, thereby inter-UAV communication is not directly proportional to n.

6.2. The Proposed Scenario Settings and Results

7. Conclusions

Competing Interest declaration

References

- K. C. Aleksander. Military use of unmanned aerial vehicles–a historical study. Safety & Defense 2018, 4, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- J. Kim, S. Kim, C. Ju, and H. I. Son. Unmanned aerial vehicles in agriculture: A review of perspective of platform, control, and applications. Ieee Access 2019, 7, 105100–105115. [Google Scholar]

- M. Lyu, Y. Zhao, C. Huang, and H. Huang. Unmanned aerial vehicles for search and rescue: A survey. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 3266. [Google Scholar]

- M. S. Qassab and Q. I. Ali. A UAV-based portable health clinic system for coronavirus hotspot areas. Healthcare Technology Letters 2022, 9, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- K. Peng, J. Du, F. Lu, Q. Sun, Y. Dong, P. Zhou, et al.. A hybrid genetic algorithm on routing and scheduling for vehicle-assisted multi-drone parcel delivery. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 49191–49200. [Google Scholar]

- W. Chen, J. Liu, H. Guo, and N. Kato. Toward robust and intelligent drone swarm: Challenges and future directions. IEEE Network 2020, 34, 278–283. [Google Scholar]

- G. Skorobogatov, C. Barrado, and E. Salamí. Multiple UAV systems: A survey. Unmanned Systems 2020, 8, 149–169. [Google Scholar]

- S. -J. Chung, A. A. Paranjape, P. Dames, S. Shen, and V. Kumar. A survey on aerial swarm robotics. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2018, 34, 837–855. [Google Scholar]

- C. W. Reynolds. Flocks, herds and schools: A distributed behavioral model. in Proceedings of the 14th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques 1987, 25-34. 1987; 25–34.

- H. T. Do, H. T. Hua, M. T. Nguyen, C. V. Nguyen, H. T. Nguyen, H. T. Nguyen, et al.. Formation control algorithms for multiple-uavs: a comprehensive survey. EAI Endorsed Transactions on Industrial Networks and Intelligent Systems 2021, 8, e3–e3.

- Q. Ouyang, Z. Wu, Y. Cong, and Z. Wang. Formation control of unmanned aerial vehicle swarms: A comprehensive review. Asian Journal of Control 2023, 25, 570–593. [Google Scholar]

- K. -K. Oh, M.-C. Park, and H.-S. Ahn. A survey of multi-agent formation control. Automatica 2015, 53, 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, J. Liu, Z. He, Z. Li, Q. Zhang, and Z. Ding. A survey of multi-agent systems on distributed formation control. Unmanned Systems 2023, 1–14.

- F. Saffre, H. Hildmann, and H. Karvonen. The design challenges of drone swarm control. in International conference on human-computer interaction 2021, 408-426. 2021, 408–426.

- O. I. Abiodun, A. Jantan, A. E. Omolara, K. V. Dada, N. A. Mohamed, and H. Arshad. State-of-the-art in artificial neural network applications: A survey. Heliyon 2018, 4.

- V. François-Lavet, P. Henderson, R. Islam, M. G. Bellemare, and J. Pineau. An introduction to deep reinforcement learning. Foundations and Trends® in Machine Learning 2018, 11, 219–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. L. Qaddoori and Q. I. Ali. An efficient security model for industrial internet of things (IIoT) system based on machine learning principles. Al-Rafidain Engineering Journal (AREJ) 2023, 28, 329–340. [Google Scholar]

- M. H. Khoshafa, T. M. Ngatched, Y. Gadallah, and M. H. Ahmed. Securing LPWANs: A Reconfigurable Intelligent Surface (RIS) Assisted UAV Approach. IEEE Wireless Communications Letters, 2023.

- H. K. Saini and K. Jain. Heuristics to Secure IoT-Based Edge-Driven UAV. in Multidisciplinary Approaches to Sustainable Human Development, ed: IGI Global. 2023, 283–301.

- S. Q. Nguyen, A.-T. Le, C.-B. Le, P. T. Tin, and Y.-H. Kim. Exploiting user clustering and fixed power allocation for multi-antenna UAV-assisted IoT systems. Sensors 2023, 23, 5537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, L. Meng, M. Zhang, and W. Meng. A secure and lightweight batch authentication scheme for Internet of Drones environment. Vehicular Communications 2023, 44, 100680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Aljumah. UAV-Based Secure Data Communication: Multilevel Authentication Perspective. Sensors 2024, 24, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Yin, N. Cheng, Y. Song, Y. Hui, Y. Li, T. H. Luan, et al.. UAV-assisted secure uplink communications in satellite-supported IoT: Secrecy fairness approach. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023.

- J. Wang, Z. Jiao, J. Chen, X. Hou, T. Yang, and D. Lan. Blockchain-aided secure access control for UAV computing networks. IEEE Transactions on Network Science and Engineering, 2023.

- I. Committee. IEEE standard for wireless access in vehicular environments-security services for applications and management messages. IEEE Vehicular Technology Society 2013, 1609.

- E. Rescorla and N. Modadugu. Datagram transport layer security version 1.2. 2070-1721, 2012.

- S. Kent and K. Seo. Security architecture for the internet protocol. 2070-1721, 2005.

- Y. Mekdad, A. Aris, L. Babun, A. E. Fergougui, M. Conti, R. Lazzeretti, et al.. A Survey on Security and Privacy Issues of UAVs. arXiv preprint, 2021; arXiv:2109.14442, 2021.

- R. N. Akram, K. Markantonakis, K. Mayes, O. Habachi, D. Sauveron, A. Steyven, et al.. Security, privacy and safety evaluation of dynamic and static fleets of drones. in 2017 IEEE/AIAA 36th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC) 2017, 1-12.

- Q. Ibrahim and M. Qassab. Theory, Concepts and Future of Self Organizing Networks (SON). Recent Advances in Computer Science and Communications (Formerly: Recent Patents on Computer Science) 2022, 15, 904–928. [Google Scholar]

- V. A. Dovgal and D. V. Dovgal. Security analysis of a swarm of drones resisting attacks by intruders. in Distance educational technologies: proceedings of the 5th Intern. scient. and pract. conf. Simferopol 2020, 372-377.

- F. Jahan, W. Sun, Q. Niyaz, and M. Alam. Security modeling of autonomous systems: a survey. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2019, 52, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Q. I. Ali. Towards Secure & Green Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI). International Journal of Applied Science and Engineering 2017, 14, 147–169. [Google Scholar]

- D. H. Lee and J. G. Kim. IKEv2 authentication exchange model and performance analysis in mobile IPv6 networks. Personal and ubiquitous computing 2014, 18, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Praptodiyono, M. I. Santoso, T. Firmansyah, A. Abdurrazaq, I. H. Hasbullah, and A. Osman. Enhancing IPsec performance in mobile IPv6 using elliptic curve cryptography. in 2019 6th International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Computer Science and Informatics (EECSI) 2019, 186-191.

- Y. -j. Lee, H.-s. Chae, and K.-w. Lee. Countermeasures against large-scale reflection DDoS attacks using exploit IoT devices. Automatika: časopis za automatiku, mjerenje, elektroniku, računarstvo i komunikacije 2021, 62, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Su, H. Zhou, Y. Deng, and M. Dohler. Energy-efficient cellular-connected UAV swarm control optimization. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications, 2023.

- K. Han, E. Al Nuaimi, S. Al Blooshi, R. Psiakis, and C. Y. Yeun. Scalable Authenticated Communication in Drone Swarm Environment. Journal of Internet Technology 2024, 25, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Q.I. Ali.Design and implementation of an embedded intrusion detection system for wireless applications. IET Information Security 2012, 6, 171–182. [CrossRef]

- M.H., Q. I. Ali, Internet of Autonomous Vehicles Communication Infrastructure: A Short Review 2023. [CrossRef]

- Q.I. Ali Securing solar energy-harvesting road-side unit using an embedded cooperative-hybrid intrusion detection system. IET Information Security 2016, 10, 386–402. [CrossRef]

- Q. I. Ali. An efficient simulation methodology of networked industrial devices. in Proc. 5th Int. Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals and Devices 2008, 1-6.

- Q. I. Ali. Security issues of solar energy harvesting road side unit (RSU). Iraqi Journal for Electrical & Electronic Engineering 2015, 11.

| Criteria | Proposed System | IEEE 1609.2 [25] | IETF DTLS (RFC 6347) [26] | IETF IPsec (RFC 4301) [27] |

| Data Encryption | AES-128 (static data), RC4 (streaming data) | AES-128 or equivalent | AES-128 or higher | AES-128 or higher |

| Authentication Method | Bidirectional Entity Authentication (RSA) | PKI, Digital Certificates | Pre-shared Keys or Certificates | Pre-shared Keys or Certificates |

| Integrity Mechanism | HMAC-SHA1 | Digital Signatures | HMAC with hash | HMAC with hash |

| Scalability | High (Designed for UAV swarms) | Moderate (Primarily for VANET) | Low to Moderate | High (for scalable networks) |

| Flexibility | High (Adapts to operational phases of a UAV swarm) | Low to Moderate (For VANET environments) | Moderate (Transport layer security) | High (Supports various network types) |

| DDoS Resistance | High (Anti-replay mechanisms, Firewall) | Moderate (For VANET resilience) | Moderate | High (Anti-replay protection) |

| Attack Type | Description |

| ID Spoofing | Pretending to be the real drone, is achieved by compromising the communication link and obtaining the ID of a certain UAV. |

| Eavesdropping Attacks | To improve communication performance, most UAVs avoid encrypting wireless communication hence allowing them to eavesdrop on transferred data, e.g. sensor and GPS data. |

| DoS and DDoS Attacks | Flooding the drone’s network card with random invaluable traffic by sending excessive requests which overloads its resources and disrupts its availability. |

| Man-in-the-Middle Attacks | One of the popular attacks is done by controlling the communication link and modifying packets maliciously. |

| Replay Attacks | After a successful eavesdropping attack, it replays valid data to the drone to enforce it to receive repeated data without the ability to separate legitimate requests from malicious ones. |

| Forgery Attacks | Compromising drone communication link integrity by sending a forged request to unauthenticated drones. |

| Key Name | Purpose | Nodes |

| AES key group 1 (multiple key pairs each for a UAV)* | To encrypt the intra-swarm reports and commands and also for bidirectional entity authentication. | SD - LD |

| AES key 2 (one key pair)* | To encrypt the inter-swarm reports and commands and also for bidirectional entity authentication. | LD - DMC |

| Public-Private key group 1 (one pair for each network node) | Key management. | SD - LD LD - DMC |

| RC4 stream ciphering* | To encrypt streamed data (if any) | SD - LD LD - DMC |

| Attack Type | Against | Flaws | Suggested Defense |

| ID spoofing | UAV, server | Pretending to be a legitimate node. | The use of suitable entity authentication methods. |

| Eavesdropping attacks | Communication link | Data disclosure, including telemetry, feeds, and DMC commands. | Adopting authenticated encryption. |

| DoS and DDoS attacks | Communication link | Compromising the availability of certain services | Using a firewall to block incoming traffic from the UDP port of origin (port 1900). |

| Man-in-the-Middle attacks | Communication link | Controlling the communication channel and modifying the packets maliciously. | Encrypting control commands. Implementing solutions to authenticate UAVs. |

| Replay attacks | UAV, server | Node confusion so it cannot separate legitimate requests from malicious ones. | Secure communication scheme establishment. The use of authentication mechanisms. The use of IPSec sequence number. |

| Forgery attacks | Communication link | Compromising UAV's communication integrity by sending a forged request to unauthenticated UAVs. | Encryption and integrity of control commands. Implementing techniques to authenticate UAVs |

| Parameter | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| t_c | Cryptographic operation time (ms) | AES-128: 2, SHA-256: 1, Auth: 5 |

| t_comm | Message transmission time (ms) | 0.04 |

| E_c | Energy per cryptographic operation (mJ) | AES-128: 0.1, SHA-256: 0.05, Auth: 0.25 |

| E_comm | Energy per message transmission (mJ) | 0.01 |

| B | Battery capacity (mJ) | 6000 |

| P_base | Base power consumption (mW) | 500 |

| α | Swarm scaling factor | 0.1 |

| T_mission | Desired mission time (s) | 3600 |

| f_c | Frequency of crypto operations (1/s) | 1/300 (every 5 min) |

| f_comm | Frequency of transmissions (1/s) | 1/300 (every 5 min) |

| Scenario | O_total (s) | E_total (mJ) | T_feasible (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n=5,α=0.1) | 1.2336 | 12.24 | 3599.83 |

| Larger Swarm (n=25,α=0.1) | 1.2816 | 12.24 | 3599.82 |

| Higher Comm Frequency (fcomm=1/60) | 2.0160 | 18.36 | 3599.69 |

| Larger Swarm (n=50,α=0.1) | 1.5616 | 12.24 | 3599.80 |

| Extreme Swarm (n=100,α=0.1) | 1.8816 | 12.24 | 3599.77 |

| Increased Scaling (n=50,α=0.2) | 1.8320 | 12.24 | 3599.78 |

| High Scaling (n=50,α=0.5) | 3.0240 | 12.24 | 3599.66 |

| High Scaling (n=100,α=0.5) | 4.6080 | 12.24 | 3599.54 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).