1. Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) is a paradigm that envisions all the real objects and devices that may also contain electronic microchips being connected to the Internet. It is already present in many industrial, public services, and consumer domains, as well as in cross-domain applications. Wireless connectivity is currently predominant between the real object/device and the wireless data reader connected to an edge computing device and the Internet. There are currently approximately 18 billion IoT objects/devices worldwide, and the number is expected to surpass 40 billion by 2030 [

1]. The trends show that IoT is expanding globally, as its market cap is expected to reach

$12 trillion by 2030 [

2].

Such a large number of various IoT objects / devices already generates an enormous amount of data, leading to many questions related to ethics, privacy and data protection [

3]. Recently, due to the recent bloom in data analytics and Machine Learning (ML) fields, data has become a resource of strategic importance [

4]. Therefore, there is a considerable demand for data on the market, but many challenges are also involved in the data business. To comply with the laws and regulations, in some cases, the data owners must be able to retain control over their data. For instance, under GDPR [

5], the data subjects must be able to access, modify and delete their data.

To ensure data sovereignty in the data market, as described by the EU’s data strategy [

6], the International Data Spaces Association (IDSA) [

7] is developing International Data Spaces (IDS) [

8]. This framework enables data owners to retain control over their data through data usage policies while being able to charge for its usage. On the other hand, this framework enables data consumers to safely and legally use the data to improve their businesses. The IDSA provides documentation and implementation guidelines that specifically address security issues. Although the guidelines are already comprehensive enough, we argue that they still can be improved. This involves systematically identifying threats and mapping them to specific components and interactions within the IDS that are not detailed in the provided documents. This method provides insight into the system’s resilience against contemporary threats.

Recently, large companies such as Disney suffered significant data breaches due to a single compromised user who downloaded an infected game modification [

9]. The hackers consequently gained access to all the data on his computer, allowing them to breach his work account. Similarly, the MOVEit data breach in 2023 exposed millions of records by exploiting a vulnerability in a file transfer tool, while T-Mobile saw 37 million customers’ data leaked due to an exposed API [

10,

11]. In 2024, it was discovered that a widely used open-source software XZ utils contained a backdoor [

12]. The backdoor allowed unauthorized users to compromise and control the OpenSSH Secure Shell Protocol (SSH) daemon process (sshd), enabling attackers to run arbitrary commands on the targeted system before the authentication stage, thereby gaining complete control over the system. In 2020, a series of Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks hit the New Zealand Stock Exchange, forcing it to suspend trading for several days. The attackers targeted the exchange’s infrastructure with a massive DDoS attack, causing a significant loss of service availability, thus undermining investor confidence [

13]. Enterprise data marketplaces typically restrict access to improve security and reduce the risk of DDoS attacks. However, severe consequences can occur if users are compromised [

14]. Recent Industry 4.0 studies show that network-based attacks represent the most significant threat [

15]. Denial of Service (DoS), DDoS, and Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attacks are the most prevalent among these. Furthermore, there has been a notable rise in the frequency of such attacks since 2017, highlighting the growing vulnerability of interconnected industrial systems. This increasing trend underscores the critical need for robust intrusion detection systems to counter these evolving threats.

In the wake of the mentioned prominent cybersecurity incidents involving data breaches and DDoS attacks, we stress the need to revisit the security mechanisms of the IDS. In this paper, we assess IDS security through the lens of the STRIDE methodology to identify vulnerabilities. We have chosen STRIDE because of its straightforward approach and suitability for a distributed system consisting of multiple components of different trust levels. Hence, we deem STRIDE capable of systematically addressing the novel threats. We also assess the feasibility of vulnerability exploitation using state-of-the-art tools and techniques. The primary contribution of this paper lies in threat analysis of the IDS, emphasizing novel threats through which recent major incidents occurred. Additionally, we establish a framework for future threat identification. Lastly, based on the results, we propose improvements to IDS, contributing to developing a more secure framework. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section II discusses background and state-of-the-art related work.

Section III provides a deeper insight into the STRIDE methodology.

Section IV shows the analysis results and proposed mitigation strategies.

Section V provides a thorough discussion of the results.

Section VI concludes the paper.

2. Background and Related Work

The proliferation of data-driven business models and various data generation, collection, storage, and retrieval technologies has led to the emergence of data space ecosystems that enable secure and sovereign data sharing among organizations. Data spaces like the IDS aim to facilitate trustworthy data exchange while ensuring data sovereignty and compliance with regulations like GDPR and NIS2. While GDPR focuses specifically on data security, NIS2 encompasses the security of the entire infrastructure, expanding the scope to the overall resilience of the systems and incident response capabilities.

The IDS connectors are a bridge between the IoT devices and the IDS, and they initially relied on Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) to exchange messages in the JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) format [

16]. Currently, the IDS components communicate using the IDS Communication Protocol 2 (IDSCP-2) [

17] and Multipart messages [

18]. The connectors play a crucial role in ensuring seamless and secure data integration across different devices and systems by managing data flow between various endpoints. They are responsible for enforcing data usage policies, maintaining data integrity, and facilitating interoperability across heterogeneous systems within the data space. Additionally, IDS connectors support trusted data exchange by authenticating the parties involved and encrypting data transmissions to prevent unauthorized access and tampering. This procedure ensures that data sovereignty is preserved, aligning with regulatory requirements and providing a secure foundation for data-driven business operations. However, as data spaces become more interconnected and complex, they also become more susceptible to security threats due to more components and complex interrelationships.

2.1. IDS Security

Several studies have highlighted the challenges of securing data spaces. For instance, the authors in [

14] discuss the security implications of data marketplaces and the importance of robust access control mechanisms. Similarly, [

15] provides a comprehensive review of cybersecurity threats in Industry 4.0, emphasizing the prevalence of network-based threats such as DoS and DDoS attacks and MitM attacks. Many EU data space projects exist [

19], but we choose to use the IDS testbed [

8] as the reference for our analysis because it is an open-source project provided by the IDSA. IDSA is a Germany-based non-profit organization comprising over 180 companies focused on establishing and promoting standards for data spaces [

7].

The authors presented the criteria for the operational IDS environment consisting of technical requirements for the IDS components [

20]. Although the criteria are already very detailed, the report omitted to address threats such as MitM attacks and application-layer DDoS attacks that often cannot be detected by the methods applicable to the network-based attacks [

21]. The certification criteria outline what security measures should be in place but may not explicitly model potential threats. These include modern hacking techniques and tools like the ones outlined in

Table 1. The way that the hackers utilize such tools is contextually described by the MITRE attack matrix for enterprise [

22].

It is worth mentioning that hackers no longer have to target someone individually. Instead, they may buy the data of the infected users on the dark web markets and exploit it using some of the aforementioned sophisticated tools [

27]. For instance, a hacker can look up the URL of the targeted enterprise and see if any of its users have been infected. If so, the hacker may proceed and buy all the data from such a user, including not only the enterprise URL credentials but all the other data from the compromised device, such as the enterprise’s Virtual Private Network (VPN) credentials, session cookies, other applications’ information, detailed device and network information, etc. Such an approach may render many conventional defense strategies useless, allowing the hackers to bypass user authentication methods and gain access to VPNs, chats, storage, source code, and other sensitive data. Our analysis aims to identify such threats systematically, mapping them to specific components and interactions within the IDS, thus complementing the mentioned criteria to form a more robust security framework both in the short-term and in the long-term.

Mahiru [

28] is a federated data exchange system, somewhat similar to the IDS concept, designed to enable secure, decentralized collaboration between multiple parties with varying levels of trust. Its strengths lie in its decentralized design, minimizing central trust dependencies, and using X.509 certificates to prevent spoofing and tampering. Its policy and registry replication provide redundancy, mitigating DDoS attacks by avoiding single points of failure. However, Mahiru faces challenges from MitM attacks involving reverse proxies, which render SSL/TLS protections ineffective. Additionally, endpoint malware could expose private keys and compromise the registry, leading to privacy breaches and the risk of DDoS attacks. Furthermore, there is the threat of backdoors in open-source software, which could introduce additional vulnerabilities. Although Mahiru offers protection against common threats, it is still susceptible to the same kinds of threats as the IDS.

MIRANDA [

29] is a Security Orchestration and Automated Response (SOAR) system that can be applied to IDS to enhance its cybersecurity capabilities. However, it does not necessarily fill all security gaps. It introduces features like automated threat detection, incident response, and Actionable Cyber-Threat Intelligence (ACTI) sharing, strengthening IDS’s security setup. MIRANDA also introduces network packet inspection through tools like Snort and Suricata and advanced analytics engines that leverage machine learning to help detect and mitigate threats like DDoS attacks. However, it comes with some weaknesses, including the risk of a single point of failure due to its centralized architecture and potential vulnerabilities from using open-source tools, which may introduce backdoors. While MIRANDA enhances overall security, endpoint vulnerabilities can still expose sensitive data. MitM attacks are not explicitly addressed, indicating that MIRANDA improves security but may leave certain novel threats unaddressed.

2.2. Threat Identification

STRIDE [

30] is a threat modeling methodology developed by Microsoft [

31] in 1999 to identify and categorize six specific types of security threats:

spoofing, tampering, repudiation, information disclosure, DoS, and elevation of privilege. A more detailed description of the types of categorized threats is shown in

Table 2. STRIDE’s strengths lie in its broad applicability and comprehensive threat coverage, albeit it can be time-intensive and requires expert knowledge. STRIDE is a straightforward and easy-to-understand approach consisting of three main steps: identification of the architecture, breaking into components or Trust Boundaries (TB) encompassing multiple components, and identifying threats to each component or TB. Therefore, STRIDE can be conducted for each component individually or for each TB, including multiple components of the same trust level. In our paper, we analyze each TB because otherwise, there would be duplicates in the results for components of the same trust level. While various other security assessment methodologies exist, such as LINDDUN for privacy threats or OCTAVE for risk management, STRIDE is most suitable for our analysis due to its versatility in handling the complex, distributed architecture of the chosen IDS testbed. By focusing on the risks inherent in authentication, data exchange, and distributed TBs, STRIDE allows us to systematically address security concerns in a multifaceted system like the IDS testbed, ensuring that all relevant threats are considered early in the design process.

In summary, while IDS and similar systems provide the means for secure data sharing, significant gaps remain in addressing threats like endpoint security, MitM and DDoS attacks, and backdoors. Given that the IDS framework is still in development, now is the ideal time to assess and address these vulnerabilities. Our work aims to identify threats systematically and proposes solutions that can be integrated into the IDS framework, thereby contributing to a more secure and resilient data space architecture.

3. Methodology

STRIDE is a widely adopted threat modeling framework that helps identify potential security threats by categorizing them into six distinct types. This systematic approach suits complex systems such as IDS, where many components with different roles and privileges interact. To conduct the STRIDE-based threat analysis, we followed the guidelines provided by the Open Worldwide Application Security Project (OWASP) [

30] and the United Kingdom’s Department for Science, innovation and Technology [

32]. We applied the STRIDE framework to the IDS by conducting the following:

System decomposition: Dismantling the IDS architecture into its core components, forming a context diagram that shows how data flows through the application.

TB enumeration: Mark the places in the context diagram where trust levels change. A single TB will surround all components with the same security attributes.

Threat enumeration: Systematically identifying potential threats for each STRIDE category at each TB.

Risk assessment: Incorporating real-world practical scenarios involving known hacking tools and techniques to illustrate how threats could manifest.

Mitigation: Provide mitigation strategies.

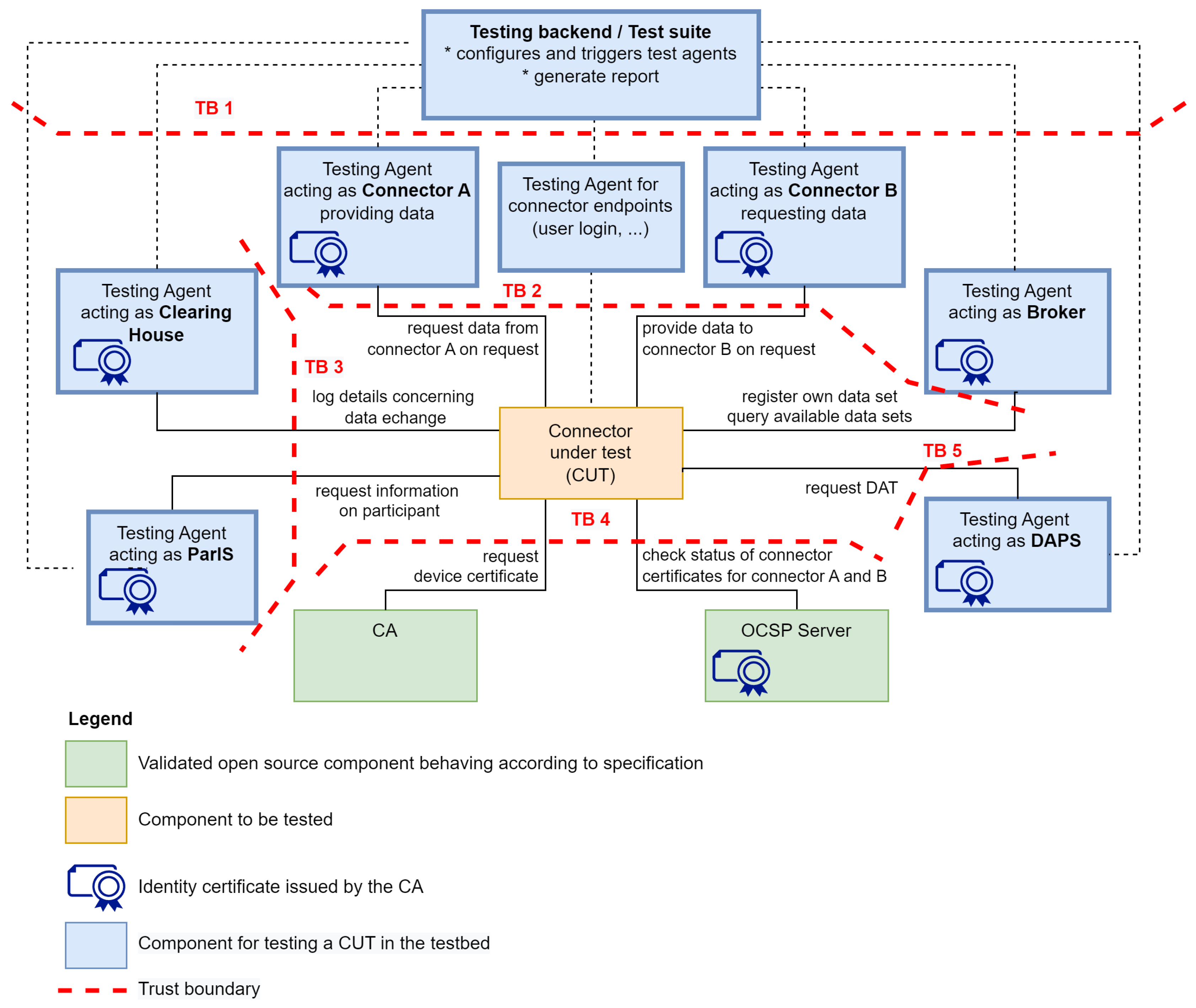

Since the IDS testbed is still in the early development stages, it is the right time now to perform the security assessment. This way, it will be easier to consider security concerns, as doing so in the later development stages requires more effort. However, even in the early stages, the project is relatively big, consisting of 13 Docker containers. Given the size of the project, we chose not to develop detailed Level-1 and Level-2 data flow diagrams. Instead, we conducted the STRIDE analysis on the context diagram of the final envisioned version of the testbed made by IDSA (

Figure 1), as it provides a simplified system overview. Despite its high-level nature, this approach helps to establish the foundations for the system’s early security posture. We present the description of the TBs in

Table 3 to provide a more detailed insight into the reasoning behind the choice of positioning the boundaries as displayed in the context diagram (

Figure 1).

The system includes a central Connector Under Test (CUT), the main component being evaluated for secure data exchange functionality within the IDS framework. The CUT interacts with multiple components, such as Clearing House, Participant Information Service (ParIS), Broker, and Dynamic Attribute Provisioning Service (DAPS). Testing Backend configures, triggers, and monitors the operations of the various test agents, generating reports on the CUT’s performance. Connector agents provide and request data, emulating a real-world data exchange. The CUT facilitates data transfer between these connectors, ensuring compliance with IDS policies and security protocols. The Broker registers and queries available data sets, while the Clearing house logs details of data exchanges, maintaining transparency and traceability. The Certificate Authority (CA) issues and manages certificates, verifying the identity and integrity of connectors. DAPS provides and verifies dynamic attributes, ensuring that only authorized entities access the data. It is worth mentioning that the system’s designed interface is web-based.

As part of the STRIDE analysis, we construct a table of strengths and vulnerabilities for each STRIDE threat type at every TB. We identify strengths and weaknesses based on the recommendations for threat modeling while also considering the already discussed threats. Upon identifying threats, we enumerate them so that each can be independently addressed.

4. Results

In this section, we present the results of the STRIDE analysis performed on the final envisioned version of the IDS testbed and provide mitigation strategies. We conducted the STRIDE analysis for each TB and enumerated the potential vulnerabilities. The results of the STRIDE analysis are presented in

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8. The vulnerabilities are enumerated in ascending order using the vxx syntax, where xx is a two-digit number starting from 01.

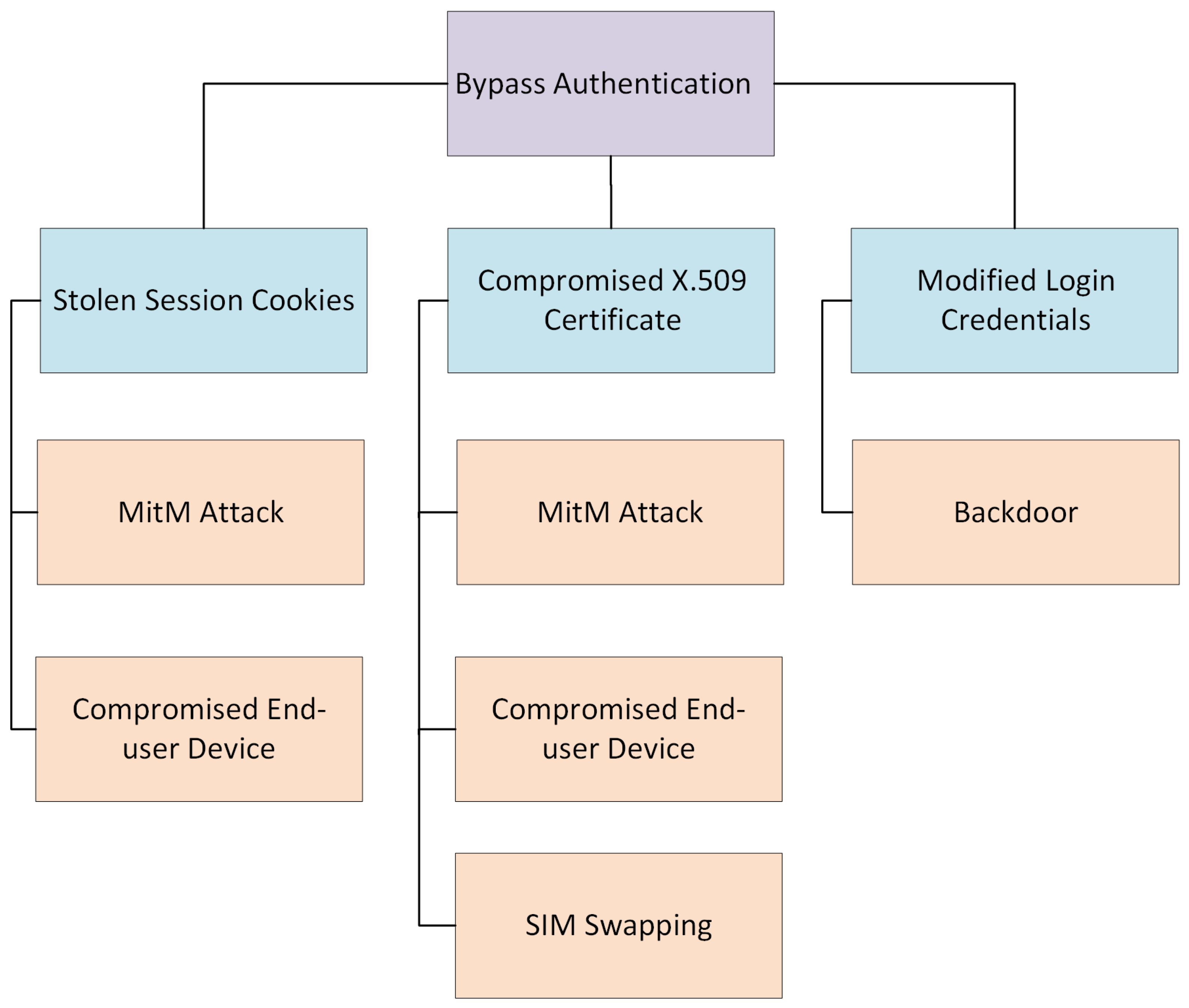

The results of our analysis confirm that novel threats such as compromised end-user devices, backdoors in open-source software, MiTM attacks, and SIM swapping pose significant security challenges to the IDS framework. Traditional vulnerabilities such as weak key management and susceptibility to DDoS attacks were also identified across multiple TBs. Most of the threats were identified individually at TB 2, where we enumerated eight vulnerabilities. This result is intuitively clear, as TB 2 is the critical interface between users (public internet) and the IDS, exposing it to external attack vectors. This exposure increases the likelihood of exploitation, primarily via compromised user devices and network-based threats such as MitM and DDoS attacks. TB 2’s vital role in handling sensitive interactions between external endpoints and the system underscores its heightened risk profile. In contrast, other TBs such as TB 1, TB 3, TB 4, and TB 5, which are responsible for secure internal operations, certificate management, and token provisioning, show fewer vulnerabilities but remain susceptible to targeted attacks, mainly if key management processes are not rigorously followed or if internal services like the CA are overwhelmed by DoS attacks. Overall, the analysis highlights several threats, particularly at TB 2, where the attack surface is the largest and the potential impact of vulnerabilities is most significant. Additionally, we present an attack tree example (

Figure 2) to illustrate the spoofing threat analysis of TB 2. Although SIM Swapping may not directly allow for the reissuing of a certificate, it may allow resetting passwords and gaining access to many online services where the users may also store X.509 certificates, such as emails, chats, and cloud storage. While the certificate is necessary for authentication, session cookies are sufficient for maintaining the session and thus pose a security risk if compromised. Similarly, root access to the system can allow the hackers to easily modify or issue new login credentials to themselves and pass the authentication phase effortlessly.

Lastly, in

Table 9, we provide mitigation strategies for the identified vulnerabilities. In addition to technical solutions, regular and comprehensive security training for IDS users should also be incorporated. Some of the discussed threats are unknown to the average users, making them the weakest link in the security chain. Security training should focus on raising awareness about risks such as SIM swapping, compromised end-user devices, and MitM attacks, as well as best practices for handling sensitive data and recognizing suspicious activities. Training should also cover how to respond to security incidents, such as reporting suspicious behavior or device compromise. By educating users, organizations can significantly reduce the likelihood of successful attacks that target human vulnerabilities.

5. Discussion

The STRIDE analysis identified several persistent vulnerabilities across the IDS in the wake of newly appearing attack vectors. TB 2 was recognized as the most risky due to its exposure to the public internet. Data from compromised end-user devices may end up on dark web markets, where it can be subsequently bought and exploited via tools such as Linken Sphere. This vulnerability may pose an even more significant threat to enterprise software, as user data may allow hackers to cause more damage. For instance, stolen session cookies can be used to access the enterprise website, data, source code, etc, allowing the hackers to steal or tamper with the data. Furthermore, end-user devices can also be victims of MitM attacks, resulting in hijacked user credentials and session cookies. While SIM swapping may seem like a minor threat affecting SMS-only services, it is far from harmless. Many digital service providers rely on phone numbers to reset passwords and gain access to their services. These include email providers, social media, and chat applications that may harbor useful information for hackers. Lastly, sophisticated attacks originate from backdoors in open-source projects that may happen to be some of the most prevalent applications, as shown in the recent examples. Such backdoors pose a significant challenge because building applications from scratch requires many resources, whereas including the existing software takes much less time and effort. Therefore, if the utilized software is compromised, it can easily lead to the most severe consequences. Detecting malicious code in such software is difficult due to obfuscated code [

33], external dependencies, etc. In our case, we assumed that the application developers did not have malicious intent and were not compromised, which may not always be the case. Overall, achieving absolute sovereignty over code is not something that most companies can afford, so remedies such as code auditing, automated software review tools, and secure coding practices are recommended. For example, Bhandari et al. [

34] provides an ML-based source code analyzer that scans the code for vulnerabilities. The system should undergo regular security assessments to keep up with the state-of-the-art threats and protection.

The IDS already incorporates industry-standard security mechanisms, such as X.509 certificates, TLS protection, RBAC, etc. However, some mechanisms, such as protection against DDoS attacks via redundancy, can be improved, as proposed in Mahiru [

28]. Adopting a semantic approach to designing authentication components, as proposed by Zhidovich et al. [

35], can improve the efficiency and compatibility of security mechanisms within the IDS. This approach emphasizes the integration of standardized, secure authentication protocols, enhancing resistance to threats such as phishing and man-in-the-middle attacks. Access points into the system should always be protected by an intrusion detection system that performs packet filtering. Since IDS is an enterprise software, removing it entirely from the public internet and allowing access to only a set of whitelisted IP addresses would significantly reduce the risk of DDoS and other attack vectors. This approach implies that the users have to connect using a VPN whose IP is trusted by the IDS. The attackers would have to compromise the user’s VPN before becoming able to attack the system. Therefore, this approach would add an additional layer of protection without any considerable trade-offs.

Nevertheless, another essential aspect that should be considered is the human factor, as the system users will interact with TB 2 the most. Human factors can be the deciding element in the success of device compromise and MitM attacks. Therefore, implementing and enforcing security policies and frequent security training sessions with the users is essential. Judging by the recent events, it appears that security incidents involving sophisticated viruses that compromise end-user devices and MitM attacks are on the rise as cyber-criminal strategies evolve and become accessible to a large number of hackers. Dark web markets present a service-oriented criminal economy where hackers no longer have to conduct the entire hacking process independently. They may instead outsource processes such as user data acquisition, setting up proxies and VPNs, creating hacking tools, and others. Rather, these and many others are now available for purchase as data, software, and services.

In our study, we used the final envisioned version of the IDS as a reference. However, as the system evolves, there may be changes to how it is implemented, but new threats may also appear in due time. Although our analysis is comprehensive, it is still limited to the available resources, and it was conducted on a high level using a context diagram. Once the software is of higher technical readiness, the analysis should be repeated using more detailed data flow diagrams. Such an approach will provide a far more detailed insight into every aspect of the system and will result in a more comprehensive security analysis. In the future, we plan to research concrete tools for preventing, detecting, and mitigating the discussed threats, thus contributing to safer enterprises.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we analyzed the IDS and performed a STRIDE threat analysis on the final envisioned version of the IDS testbed. We presented some of the most impactful state-of-the-art hacking tools and techniques and integrated them into our analysis. Using the context diagram provided by the IDSA, we identified five TBs and conducted the STRIDE analysis for each. The results indicate that the highest number of threats exist at the TB between end-users and the IDS system. We highlighted both technical aspects and the importance of the human factor in cybersecurity. Lastly, we proposed a set of mitigation strategies and discussed potential system improvements. This study lays the foundation for further threat analysis of the IDS and should aid researchers and industry in developing a more robust and secure data spaces framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.G. and A.A.; methodology, N.G. and A.S.; validation, A.S., A.R. and A.P.; formal analysis, N.G.; investigation, N.G.; writing—original draft preparation, N.G. and A.A.; writing—review and editing, all authors contributed; visualization, N.G.; supervision, A.R. and A.P.; project administration, A.R. and A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Kristiania University College and HSLU. and The APC was funded by Kristiania University College.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Analytics, I. Number of Connected IoT Devices. https://iot-analytics.com/number-connected-iot-devices/, accessed on 2024-10-02. IoT Market Update—Summer 2024.

- Al-Sarawi, S.; Anbar, M.; Abdullah, R.; Al Hawari, A.B. Internet of Things Market Analysis Forecasts, 2020–2030. 2020 Fourth World Conference on Smart Trends in Systems, Security and Sustainability (WorldS4), 2020, pp. 449–453. [CrossRef]

- Liebrand, K.; Moser, K.; Knüsli, S.; Copigneaux, B.; Le Gall, F.; Smadja, P.; Andrushevich, A.; Melakessou, F. Ethics, privacy and data protection in BUTLER. Project Title: Ubiquitous, Secure Internet-of-Things with Location and Contex-Awareness, EU FP7 Project 2011.

- Rainie, S.C.; Lee Schultz, J.; Briggs, E.; Riggs, P.; Palmanteer-Holder, N.L. Data as a Strategic Resource. International Indigenous Policy Journal 2017, 8, 1–29.

- Info, G. General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). https://gdpr-info.eu/, accessed on 2024-10-02. European Data Protection Regulation.

- European Strategy for Data. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/strategy-data, accessed on 2024-10-02.

- (IDSA), I.D.S.A. International Data Spaces. https://internationaldataspaces.org/, accessed on 2024-10-02. Dataspace Protocol and International Standards for Trusted Data Sharing.

- (IDSA), I.D.S.A. International Data Spaces Testbed. https://github.com/International-Data-Spaces-Association/IDS-testbed/tree/master, accessed on 2024-10-02. GitHub repository.

- Bingham, S. Disney, Slack, and the Case of the Missing 13,000 PDFs. https://www.fileopen.com/blog/disney-slack-and-the-case-of-the-missing-13000-pdfs, accessed on 2024-10-02. FileOpen Blog.

- Ventures, C. MOVEit Breach: How Cl0p Exploited File Transfer Vulnerabilities. https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa23-158a, accessed on Accessed: 7 October 2024.

- Smith, J. T-Mobile Data Breach Exposes 37 Million Customers’ Personal Data. https://techcrunch.com/2023/01/19/t-mobile-data-breach, accessed on Accessed: 7 October 2024.

- CVE-2024-3094 - XZ Backdoor. https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2024-3094, accessed on 2024-10-02.

- Journal, I. Massive DDoS Attack Takes New Zealand Stock Exchange Offline for 4 Days. https://www.insurancejournal.com/news/international/2021/02/05/600216.htm. Accessed: 7 October 2024.

- Eichler, R.; Gröger, C.; Hoos, E.; Stach, C.; Schwarz, H.; Mitschang, B. Introducing the enterprise data marketplace: a platform for democratizing company data. Journal of Big Data 2023, 10, 173. [CrossRef]

- Pedreira, V.; Barros, D.; Pinto, P. A review of attacks, vulnerabilities, and defenses in industry 4.0 with new challenges on data sovereignty ahead. Sensors 2021, 21, 5189. [CrossRef]

- Nast, M.; Rother, B.; Golatowski, F.; Timmermann, D.; Leveling, J.; Olms, C.; Nissen, C. Work-in-Progress: Towards an International Data Spaces Connector for the Internet of Things. 2020 16th IEEE International Conference on Factory Communication Systems (WFCS), 2020, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- (IDSA), I.D.S.A. IDS-G Protocols: IDSCP2. https://github.com/International-Data-Spaces-Association/IDS-G/tree/main/Communication/protocols/idscp2, accessed on 2024-10-02.

- (IDSA), I.D.S.A. IDS-G Communication Protocols: Multipart. https://docs.internationaldataspaces.org/ids-knowledgebase/ids-g/communication/protocols/multipart, accessed on 2024-10-02.

- Data Spaces. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/data-spaces, accessed on 2024-10-02.

- Menz, N.; Resetko, A. Criteria Catalogue: Operational Environments. Technical Report 5675802, Zenodo, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Praseed, A.; Thilagam, P.S. DDoS Attacks at the Application Layer: Challenges and Research Perspectives for Safeguarding Web Applications. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2019, 21, 661–685. [CrossRef]

- MITRE ATT&CK Framework Version 9. https://attack.mitre.org/versions/v9/, accessed on 2024-10-02.

- The Phishing Framework for Red Team Companies. https://evilginx.com/, accessed on 2024-10-02.

- For Pentesters of Antifraud Systems. https://ls.app/, accessed on 2024-10-02.

- Kim, M.; Suh, J.; Kwon, H. A Study of the Emerging Trends in SIM Swapping Crime and Effective Countermeasures. 2022 IEEE/ACIS 7th International Conference on Big Data, Cloud Computing, and Data Science (BCD), 2022, pp. 240–245. [CrossRef]

- Arasaratnam, O.; Bennett Pursell, Harry Toor, C.R. XZ Backdoor CVE-2024-3094. https://openssf.org/blog/2024/03/30/xz-backdoor-cve-2024-3094/, accessed on 2024-10-02.

- Kermitsis, E.; Kavallieros, D.; Myttas, D.; Lissaris, E.; Giataganas, G., Dark Web Markets. In Dark Web Investigation; Akhgar, B.; Gercke, M.; Vrochidis, S.; Gibson, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 85–118. [CrossRef]

- Veen, L.E.; Shakeri, S.; Grosso, P. Mahiru: a federated, policy-driven data processing and exchange system. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.17155 2022.

- Repetto, M. Adaptive monitoring, detection, and response for agile digital service chains. Computers & Security 2023, 132, 103343. [CrossRef]

- Conklin, L.; Victoria Drake, Sven Strittmatter, Z.B.; Shostack, A. Threat Modeling Process. https://owasp.org/www-community/Threat_Modeling_Process, accessed on 2024-10-02.

- Blog, M.S. STRIDE Chart. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2007/09/11/stride-chart/, accessed on 2024-10-02.

- Department for Science, I..T.D. Conducting a STRIDE-based threat analysis. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/secure-connected-places-playbook-documents/conducting-a-stride-based-threat-analysis, accessed on 2024-10-02. Secure Connected Places Playbook.

- Behera, C.K.; Bhaskari, D.L. Different obfuscation techniques for code protection. Procedia Computer Science 2015, 70, 757–763. [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, G.P.; Assres, G.; Gavric, N.; Shalaginov, A.; Grønli, T.M. IoTvulCode: AI-enabled vulnerability detection in software products designed for IoT applications. International Journal of Information Security 2024, pp. 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Zhidovich, A.; Lubenko, A.; Vojteshenko, I.; Andrushevich, A. Semantic Approach to Designing Applications with Passwordless Authentication According to the FIDO2 Specification. OSTIS 2023, p. 311.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).