Submitted:

14 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- Risk of Overtraining: The high volume of kicking sets (8x50m daily) may strain knee and hip flexors, particularly in developing cadets. Studies note that excessive repetition of flutter kicks can lead to overuse injuries (Wirth et al., 2022).

- Psychological Fatigue: While novelty initially motivated swimmers, extended use of the same drills (6+ weeks) risks boredom, which could diminish returns (Sammoud et al., 2018).

- Comparison to Classical Training: The control group classical program (technical drills, steady-state freestyle) showed slower gains but may offer better long-term technical mastery (Veiga & Roig, 2015). Hybrid models combining both approaches could optimize results.

- -

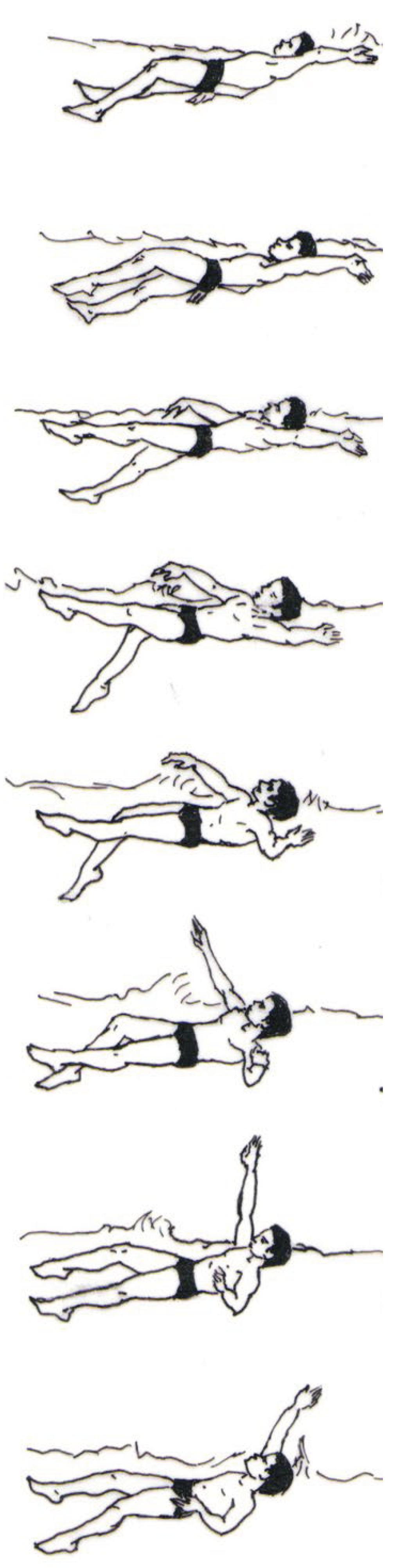

- Increased leg strength and power backstroke leg training can help improve leg strength and power, which can translate to improvements in freestyle swimming;

- -

- Improved muscle endurance backstroke leg training can help improve muscle endurance, which can be beneficial for longdistance swimming events;

- -

- enhanced neuromuscular coordination backstroke leg training can help improve neuromuscular coordination, which can be beneficial for swimming efficiency and speed.

- -

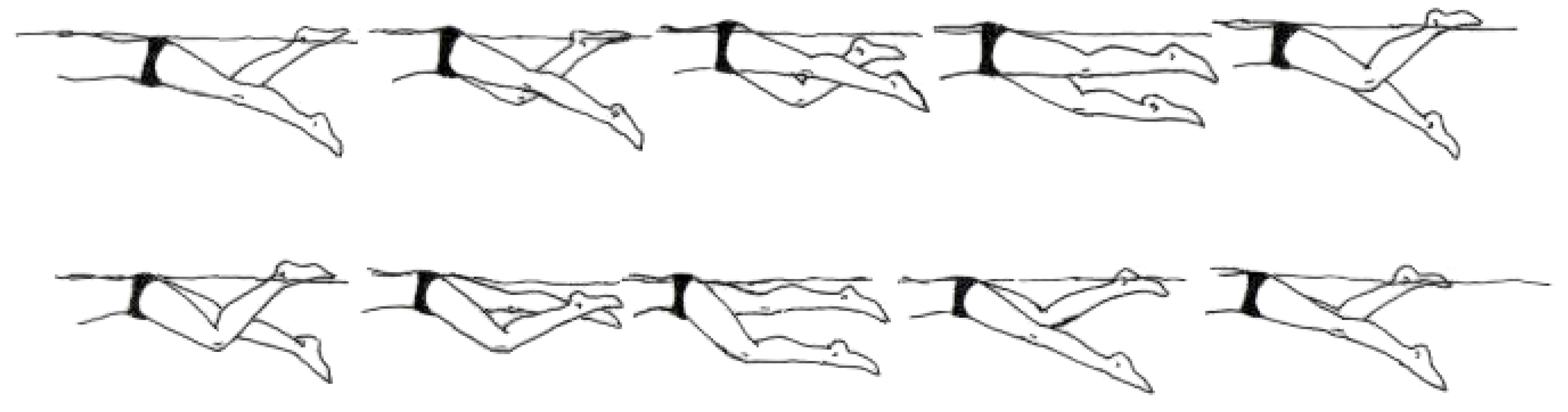

- amplitude relatively small amplitude and large kicks increase drag;

- -

- frequency high frequency.

- -

- technique the kick originates from the hip, with a relaxed knee and ankle, creating ’’whipping ’’ motion and both upkick and downkick contribute to propulsion.

- -

- amplitude like freestyle, smaller is generally better to reduce drag.

- -

- frequency high frequency.

- -

- technique the kick originates from the hip, with a relaxed knee and ankle, creating a “whipping” motion. The ‘’upward’’ kick is often emphasized more in backstroke for propulsion.

- -

- flutter kick mechanics: both strokes rely on a similar flutter kick technique originating from the hips. The muscle activation patterns are very similar, although the emphasis on the upkick versus the downkick might vary slightly. Strengthening the hip flexors, extensors, quadriceps, hamstrings, and calf muscles through backstroke kicking directly benefits the freestyle kick;

- -

- core engagement: both strokes require significant core stability to maintain body position, facilitate rotation, and transfer power from the legs to the arms. Backstroke kicking necessitates strong core activation to prevent excessive arching of the back and maintain a streamlined body position.

- -

- propulsive principles: improving the leg drive through backstroke training translates to a more powerful core engagement during both swim styles.

- -

- body roll is important in both freestyle and backstroke for reach and power. The coordinated activation of oblique abdominal muscles helps generate this roll. Training in one stroke will improve muscle efficiency in the other.

- -

- body position prone versus supine affects the distribution of muscle activation and the way the swimmer interacts with the water;

- -

- emphasis on kick phase: while the flutter kick is similar, backstroke often places greater emphasis on the upward kick for propulsion.

- -

- the biomechanical similarities between the freestyle and backstroke flutter kicks provide a strong rationale for using backstroke leg training to enhance freestyle performance. Both kicks originate from the hips, utilize similar muscle activation patterns in the legs (Gonjo et al., 2021), and require core stability to maintain a streamlined body position;

- -

- by strengthening the hip flexors, extensors, quadriceps, hamstrings, and calf muscles through backstrokespecific kicking drills, swimmers can improve the power and efficiency of their freestyle kick. Furthermore, the heightened core engagement demanded by backstroke kicking translates to improved stability and power transfer in the freestyle stroke, ultimately contributing to increased swimming speed (Silva, A. et al., 2013).

Method

Hypothesis

Methodology

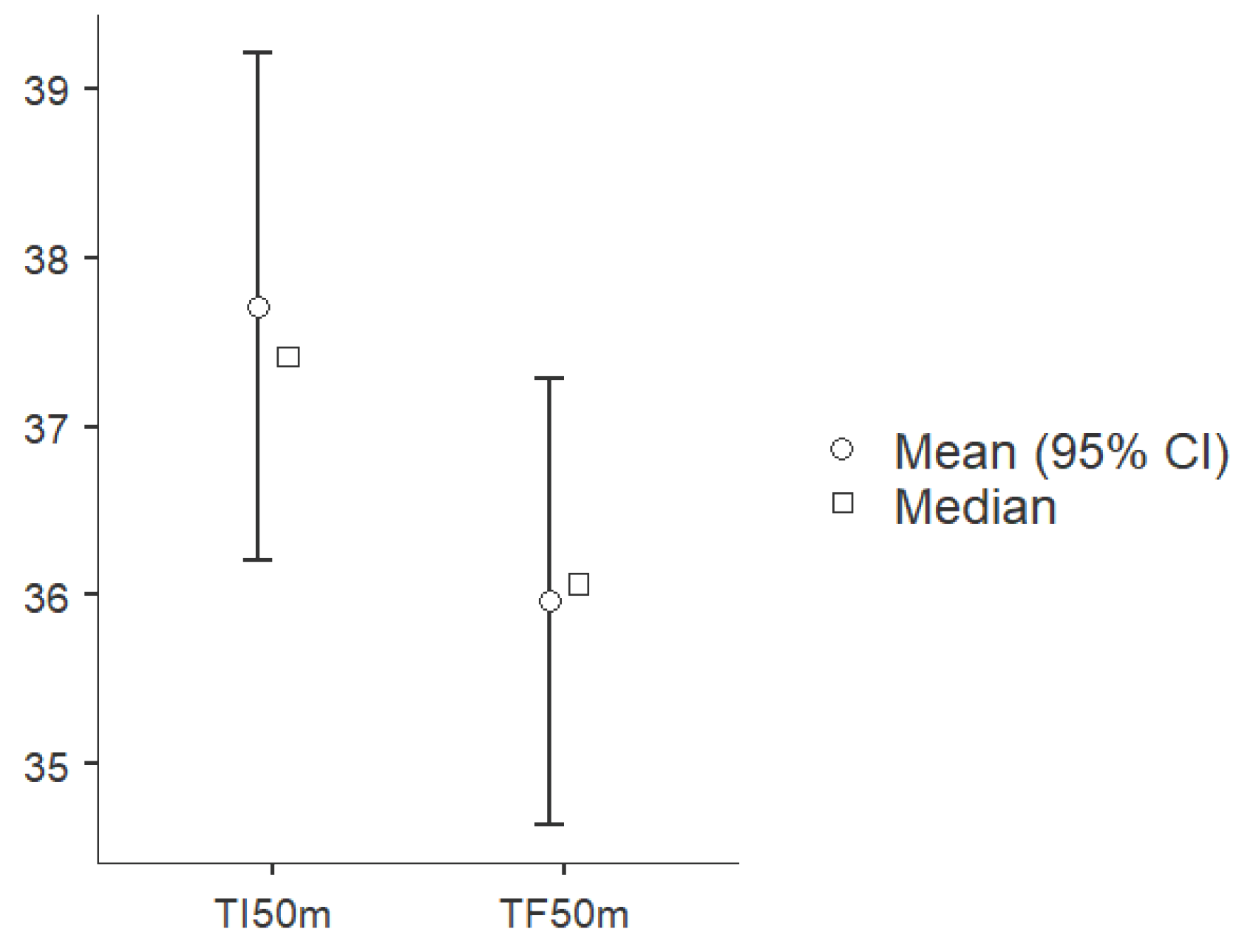

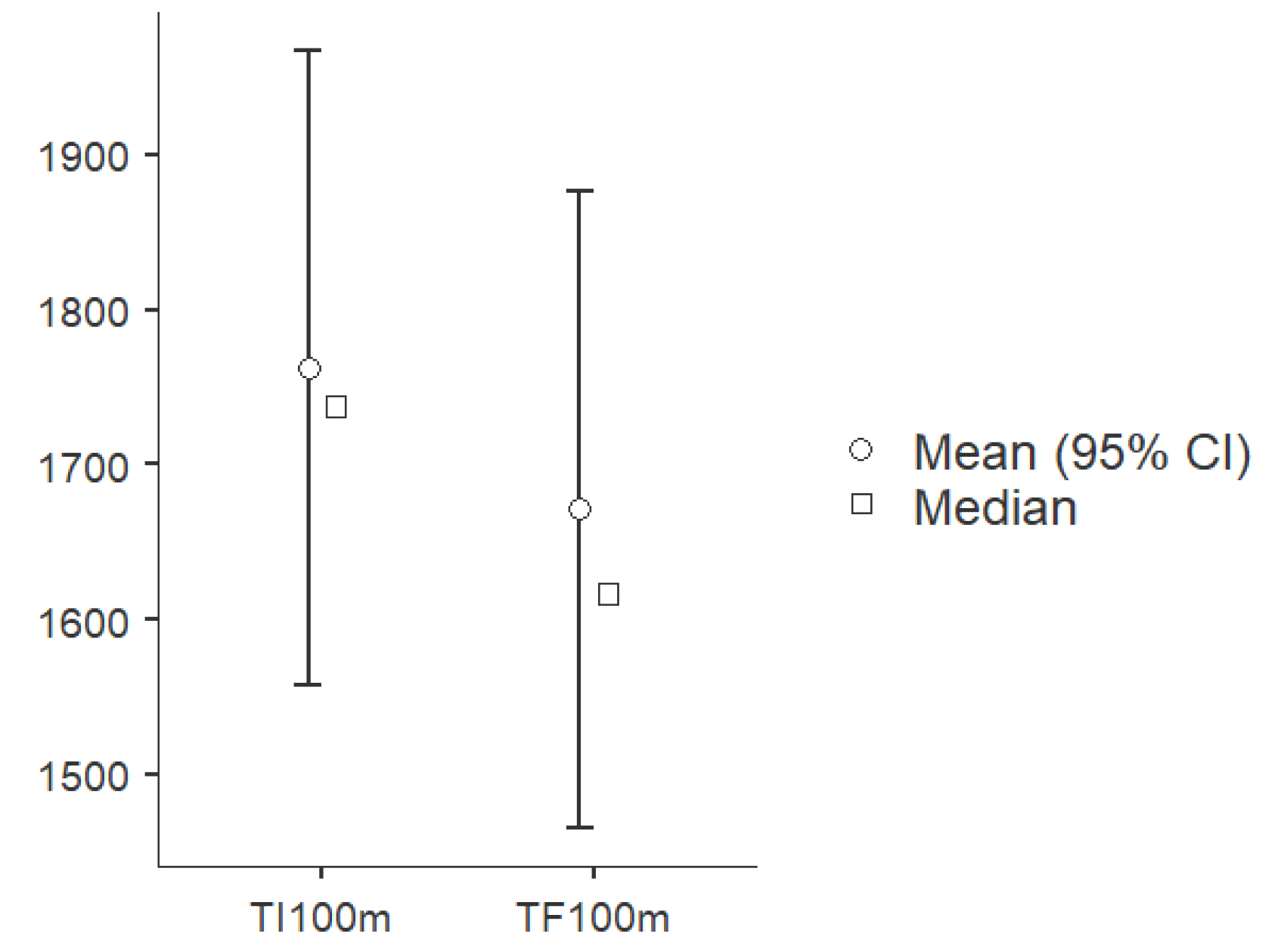

Results

Discussions

Conclusions

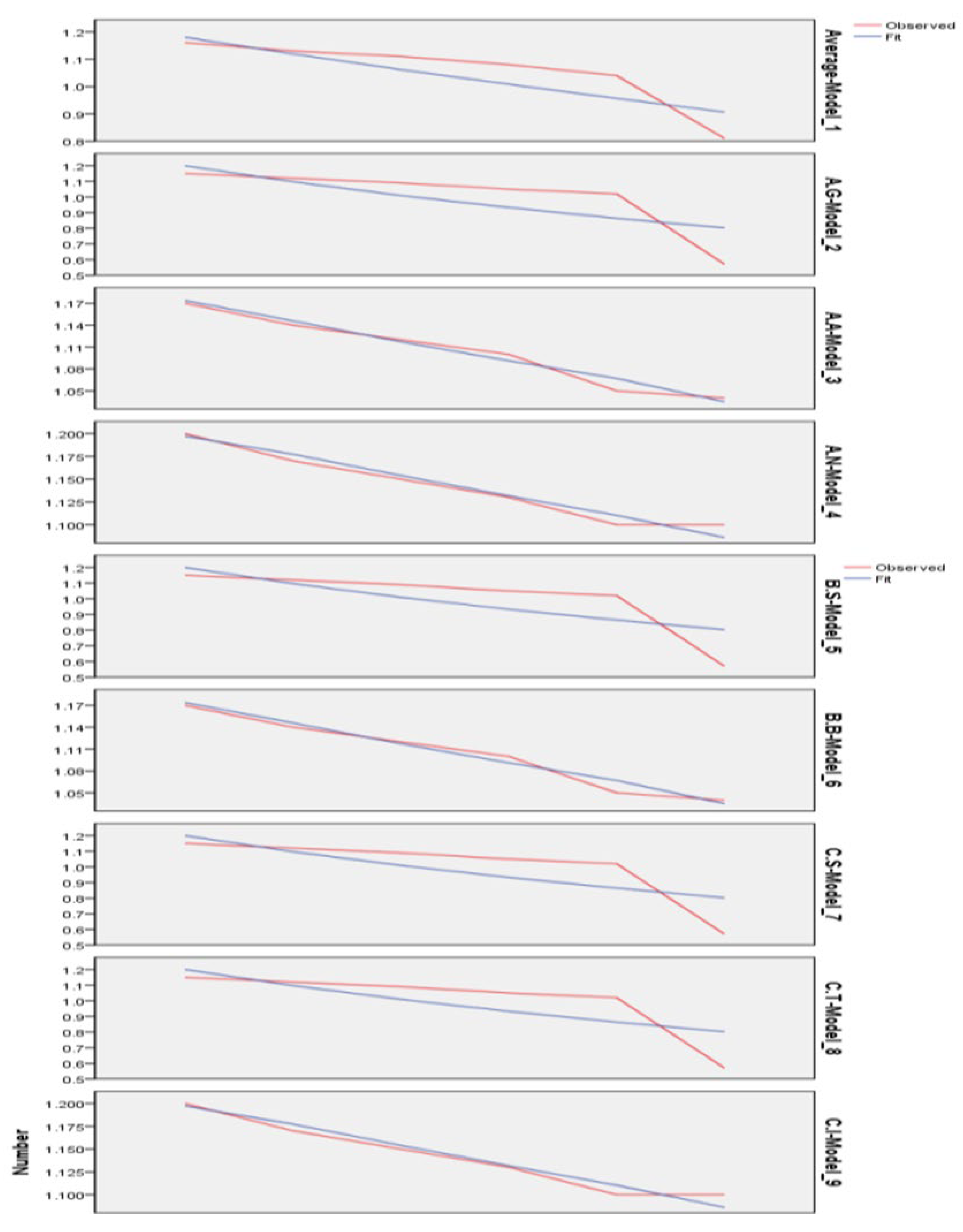

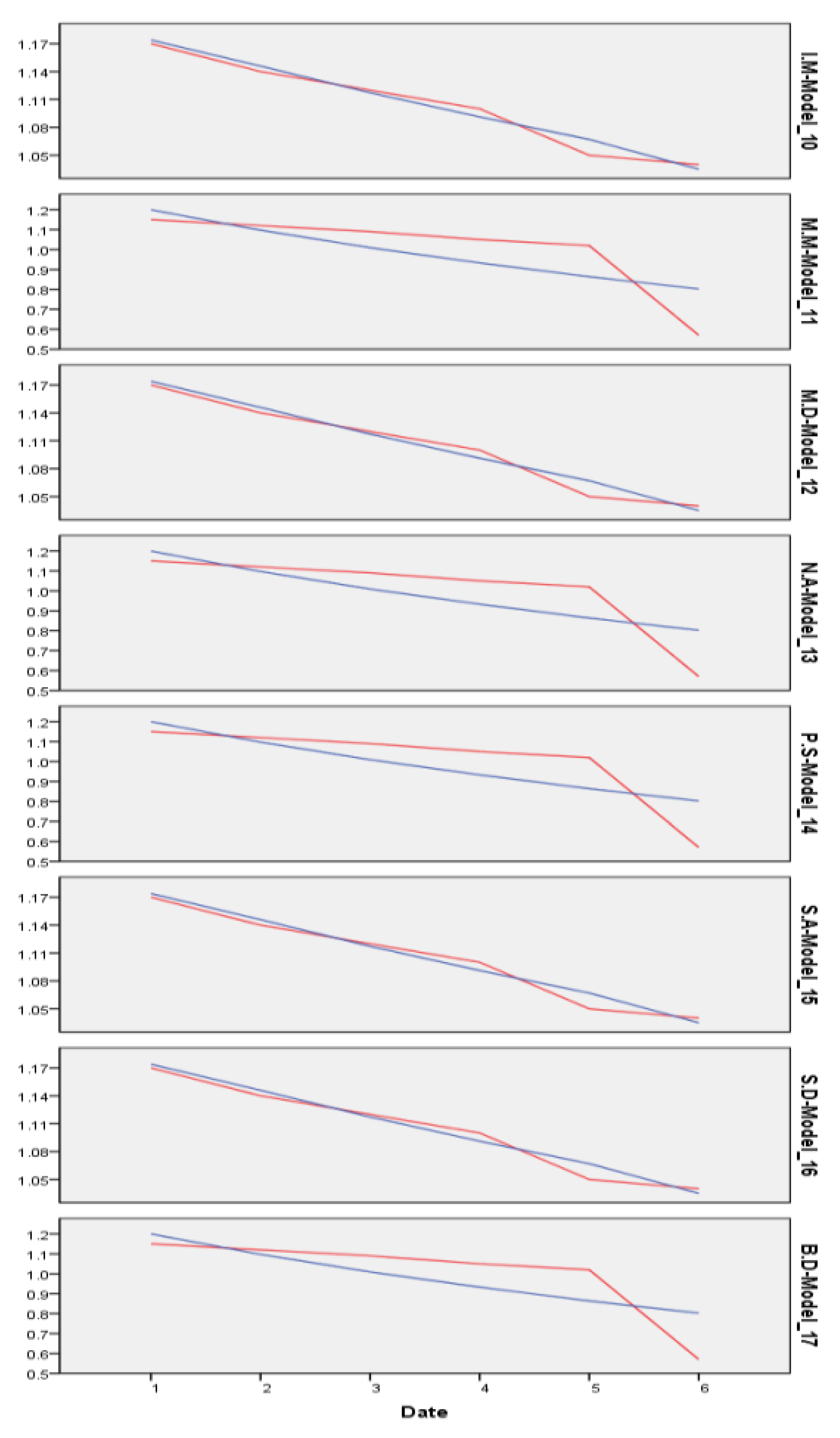

| No | Sex | Class | Age | Initial testing/ 50 m freestyle 11.01.2023 | Final testing/ 50 m freestyle 22.02.2023 | Initial testing/ 100 m freestyle 12.01.2023 | Final testing/ 100 m freestyle 23.02.2023 | Week 1 8x50 Back leg/ pl.1.20 | Week 2 8x50 Back leg/ pl.1.20 | Week 3 8x50 Back leg/ pl.1.15 | Week 4 8x50 Back leg/ pl.1.15 | Week 5 8x50 Back leg/ pl.1.10 | Week 6 8x50 Back leg/ pl.1.10 |

| 1 | F | 6 | 13 | 38,86 | 36,72 | 1’21’’83 | 1’20’’23 | 1.14-1.15 | 1.10-1.12 | 1.07-1.09 | 1.03-1.05 | 1.00-1.02 | 0.55-0.57 |

| M | 6 | 13 | 34,92 | 33,24 | 1’14’’27 | 1’13’’73 | 1.15-1.17 | 1.13-1.14 | 1.11-1.12 | 1.09-1.10 | 1.04-1.05 | 1,04 | |

| M | 6 | 13 | 43,16 | 40,26 | 1’32’’06 | 1’30’’59 | 1.18-1.20 | 1.16-1.17 | 1.14-1.15 | 1.11-1.13 | 1,10 | 1,10 | |

| F | 6 | 13 | 38,29 | 35,63 | 1’22’’13 | 1’20’’13 | 1.14-1.15 | 1.10-1.12 | 1.07-1.09 | 1.03-1.05 | 1.00-1.02 | 0.55-0.57 | |

| F | 6 | 13 | 42,65 | 40,27 | 1’33’’00 | 1’31’’97 | 1.15-1.17 | 1.13-1.14 | 1.11-1.12 | 1.09-1.10 | 1.04-1.05 | 1,04 | |

| F | 6 | 13 | 42,88 | 40,30 | 1’33’’19 | 1’31’’36 | 1.14-1.15 | 1.10-1.12 | 1.07-1.09 | 1.03-1.05 | 1.00-1.02 | 0.55-0.57 | |

| M | 6 | 13 | 34,07 | 32,83 | 1’14’’15 | 1’12’’87 | 1.14-1.15 | 1.10-1.12 | 1.07-1.09 | 1.03-1.05 | 1.00-1.02 | 0.55-0.57 | |

| M | 6 | 13 | 38,17 | 37,32 | 1’23’’26 | 1’21’’06 | 1.18-1.20 | 1.16-1.17 | 1.14-1.15 | 1.11-1.13 | 1,10 | 1,10 | |

| F | 6 | 13 | 39,25 | 36,87 | 1’31’’12 | 1’29’’49 | 1.15-1.17 | 1.13-1.14 | 1.11-1.12 | 1.09-1.10 | 1.04-1.05 | 1,04 | |

| M | 6 | 13 | 34,28 | 32,77 | 1’15’’10 | 1’12’’92 | 1.14-1.15 | 1.10-1.12 | 1.07-1.09 | 1.03-1.05 | 1.00-1.02 | 0.55-0.57 | |

| M | 6 | 13 | 37,59 | 36,51 | 1’26’’88 | 1’25’’68 | 1.15-1.17 | 1.13-1.14 | 1.11-1.12 | 1.09-1.10 | 1.04-1.05 | 1,04 | |

| M | 6 | 13 | 35,32 | 33,87 | 1’15’’16 | 1’12’’77 | 1.14-1.15 | 1.10-1.12 | 1.07-1.09 | 1.03-1.05 | 1.00-1.02 | 0.55-0.57 | |

| M | 6 | 13 | 34,18 | 32,16 | 1’15’’18 | 1’13’’55 | 1.14-1.15 | 1.10-1.12 | 1.07-1.09 | 1.03-1.05 | 1.00-1.02 | 0.55-0.57 | |

| M | 6 | 13 | 35,98 | 34,58 | 1’24’’20 | 1’22’10 | 1.15-1.17 | 1.13-1.14 | 1.11-1.12 | 1.09-1.10 | 1.04-1.05 | 1,04 | |

| M | 6 | 13 | 36,49 | 35,47 | 1’26’’93 | 1’25’’28 | 1.15-1.17 | 1.13-1.14 | 1.11-1.12 | 1.09-1.10 | 1.04-1.05 | 1,04 | |

| F | 6 | 13 | 37,24 | 36,61 | 1’22’’29 | 1’20’’48 | 1.14-1.15 | 1.10-1.12 | 1.07-1.09 | 1.03-1.05 | 1.00-1.02 | 0.55-0.57 |

References

- Alshdokhi, K. , Petersen, C., Clarke, J. 2020, Improvement and variability of adolescent backstroke swimming performance by age. Front. Sport Act Living. [CrossRef]

- Arkadiusz Stanula, Adam Maszczyk, Robert Roczniok et al., The Development and Prediction of Athletic Performance in Freestyle Swimming, 2012, Journal of Human Kinetics volume 32, 97-107. [CrossRef]

- Born, D.-P. , Schönfelder, M., Logan, O., Olstad, B. & Romann, M., 2022, Performance development of european swimmers across the olympic cycle. Front. Sport Act Liv. [CrossRef]

- De Jesus, K. et al., 2011, Biomechanical analysis of backstroke swimming starts. Int J Sports Med 2011; 32(7): 546-551. [CrossRef]

- Didier, C., Seifert, L., Carter, M. 2008, Arm coordination in elite backstroke swimmers. J. Sports Sci. 26, 675–682. [CrossRef]

- Dormehl, S., Williams, C., Robertson, S., 2016, Modelling the progression of male swimmers’ performances through adolescence. Sports. 4, 2 Sports 2016, 4(1), 2. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A. et al., 2022, Velocity variability and performance in backstroke in elite and good-level swimmers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19. [CrossRef]

- Gonjo, T. , McCabe, C., Sousa, A., Ribeiro, J., Fernandes, R. J., Vilas-Boas, J. P., Sanders, R., 2018, Differences in kinematics and energy cost between front crawl and backstroke below the anaerobic threshold. European Journal of Applied Physiology, Volume 118, 1107–1118. [CrossRef]

- Gonjo, T. et al., 2020, Front crawl is more efficient and has smaller active drag than backstroke swimming: kinematic and kinetic comparison between the two techniques at the same swimming speeds. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. Volume 8 - 2020. [CrossRef]

- Gonjo, T. , Fernandes, R., Vilas-Boas, J. P., Sanders, R., 2021 (1), Body roll amplitude and timing in backstroke swimming and their differences from front crawl at the same swimming intensities. Sci. Rep. [CrossRef]

- Gonjo, T., Fernandes, R., Vilas-Boas, J. P., Sanders, R., 2021 (2), Differences in the rotational effect of buoyancy and trunk kinematics between front crawl and backstroke swimming. Sport Biomech. 22(12), 1590–1601. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W., Soh, K.G., Zakaria, N.S., Baharuldin, M.T.H., Gao, Y.; Effect of Resistance Training Methods and Intensity on the Adolescent Swimmer’s Performance: A Systematic Review. 2022.

- John Kulas, Renata Garcia Prieto Palacios Roji, Adam Smith, IBM SPSS Essentials: Managing and Analyzing Social Sciences Data, Print ISBN:9781119417422 Online ISBN:9781119417453 |DOI:10.1002/9781119417453 © 2021 John Wiley & Sons Inc. 9. [CrossRef]

- Kerby, D. S. , 2014, The simple difference formula: An approach to teaching nonparametric correlation. Comprehensive Psychology, 3, 2165–2228. [CrossRef]

- Khaled Alshdokhi, Carl Petersen, Jenny Clarke, Improvement and Variability of Adolescent Backstroke Swimming Performance by Age, Front. Sports Act. Living, 23 April 2020, Sec. Sports Science, Technology and Engineering, Volume 2 - 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lerda, R. , Cardelli, C., 2003, Analysis of stroke organisation in the backstroke as a function of skill. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 74, 215–219. [CrossRef]

- Nikodelis, T. , Gourgoulis, V., Lola, A., Ntampakis, I., Kollias, I., 2023, Front Crawl and Backstroke Sprint Swimming have Distinct Differences along with Similar Patterns Regarding Trunk Rotations, Journal of Sports Sciences, 28(3), 229–236. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team, 2022, R: A Language and environment for statistical computing. (Version 4.1) [Computer software]. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org. (R packages retrieved from CRAN snapshot 2023-04-07).

- Revelle, W. , 2023, Psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. [R package]. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.

- Sammoud, S. et al., 2018, Key somatic variables in young backstroke swimmers. J. Sports Sci. 37, 1162–1167. [CrossRef]

- Silva, A., Figueiredo, P., Seifert, L., Soares, S., Vilas-Boas, J. P., 2013, Backstroke technical characterization of 11–13 year-old swimmers. J. Sport Sci. Med. 24(3), 409–419.

- Sonia, N. S. , 2010, Relationship between different swimming styles and somatotype in national level swimmers. Br. J. Sports Med. 44, i13. [CrossRef]

- Stan E. A. Swimming and rescue from drowning, Printech, ISBN 978-606-23-0173-6, Bucharest, 2014.

- Stibilj, J. , Košmrlj, K., Jernej, K. 2020, Evaluation of Mistakes in Backstroke Swimming. Kinesiologia Slovenica; Ljubljana Vol. 26, Iss. 2, (2020): 5-15.

- Tomohiro, G. , Narita K., et al., 2020, Front Crawl Is More Efficient and Has Smaller Active Drag Than Backstroke Swimming: Kinematic and Kinetic Comparison Between the Two Techniques at the Same Swimming Speeds, Front Bioeng Biotechnol, Sep 24;8:570657. [CrossRef]

- Veiga, S., Roig, A., 2015, Underwater and surface strategies of 200 m world level swimmers. J. Sports Sci. 34, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Vilain, M., Careau, V., 2022, Performance trade-offs in elite swimmers. Adapt Hum. Behav. Physiol. 8(1), 28–51.

- Watanabe, Y. , Wakayoshi, K., Nomura, T., 2017, New evaluation index for the retainability of a swimmer’s horizontal posture. PLoS One, 12(5) e0177368. [CrossRef]

- West R., Lorimer A., Pearson S. et al., 2022, The Relationship Between Undulatory Underwater Kick Performance Determinants and Underwater Velocity in Competitive Swimmers: A Systematic Review, 2022, Open access, Published: 28 July, Volume 8, article number 95. [CrossRef]

- Wirth, K. , Keiner, M., Fuhrmann, S., Nimmerichter, A., Haff, G.G.; 2022, Strength Training in Swimming. Environ Res Public Health, Apr 28; 19(9):5369. [CrossRef]

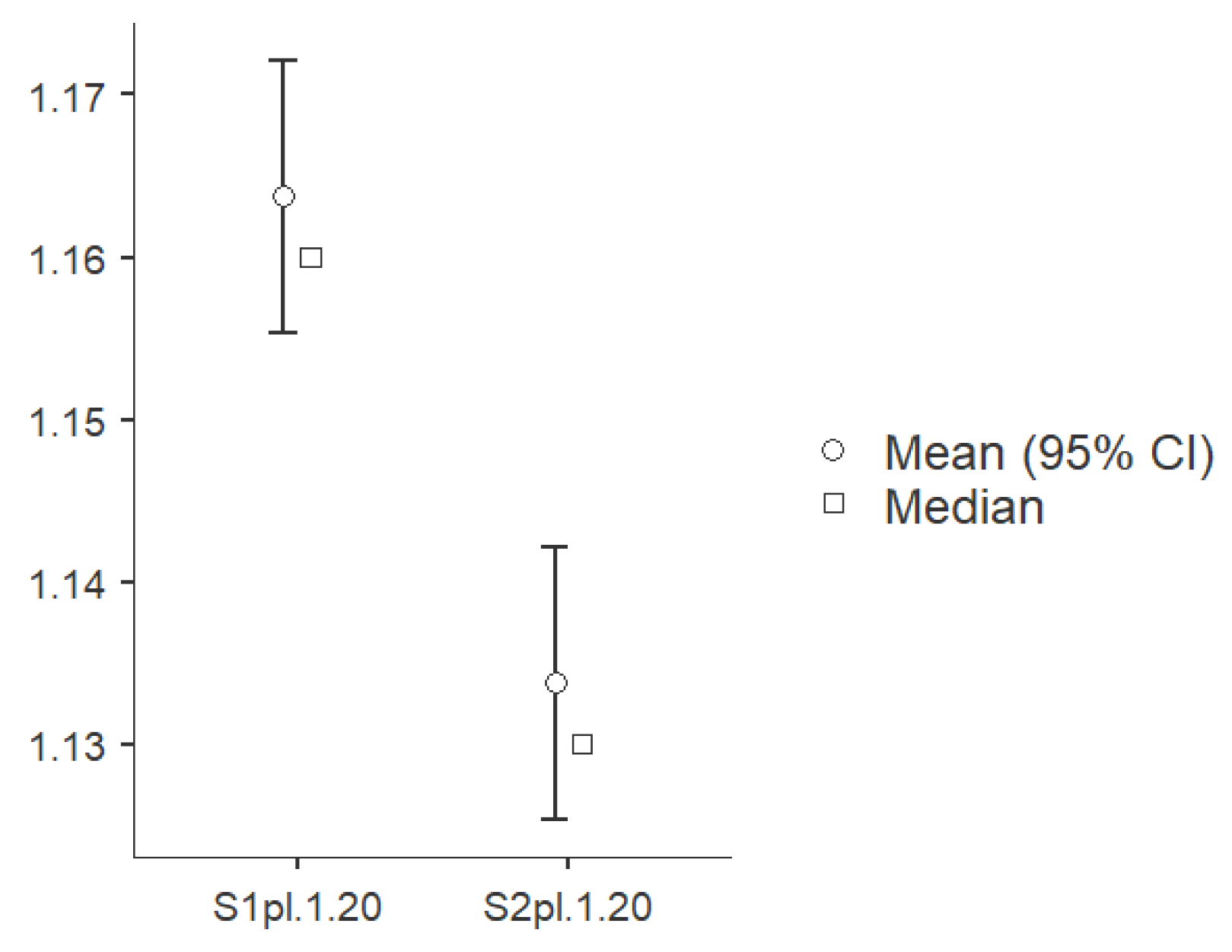

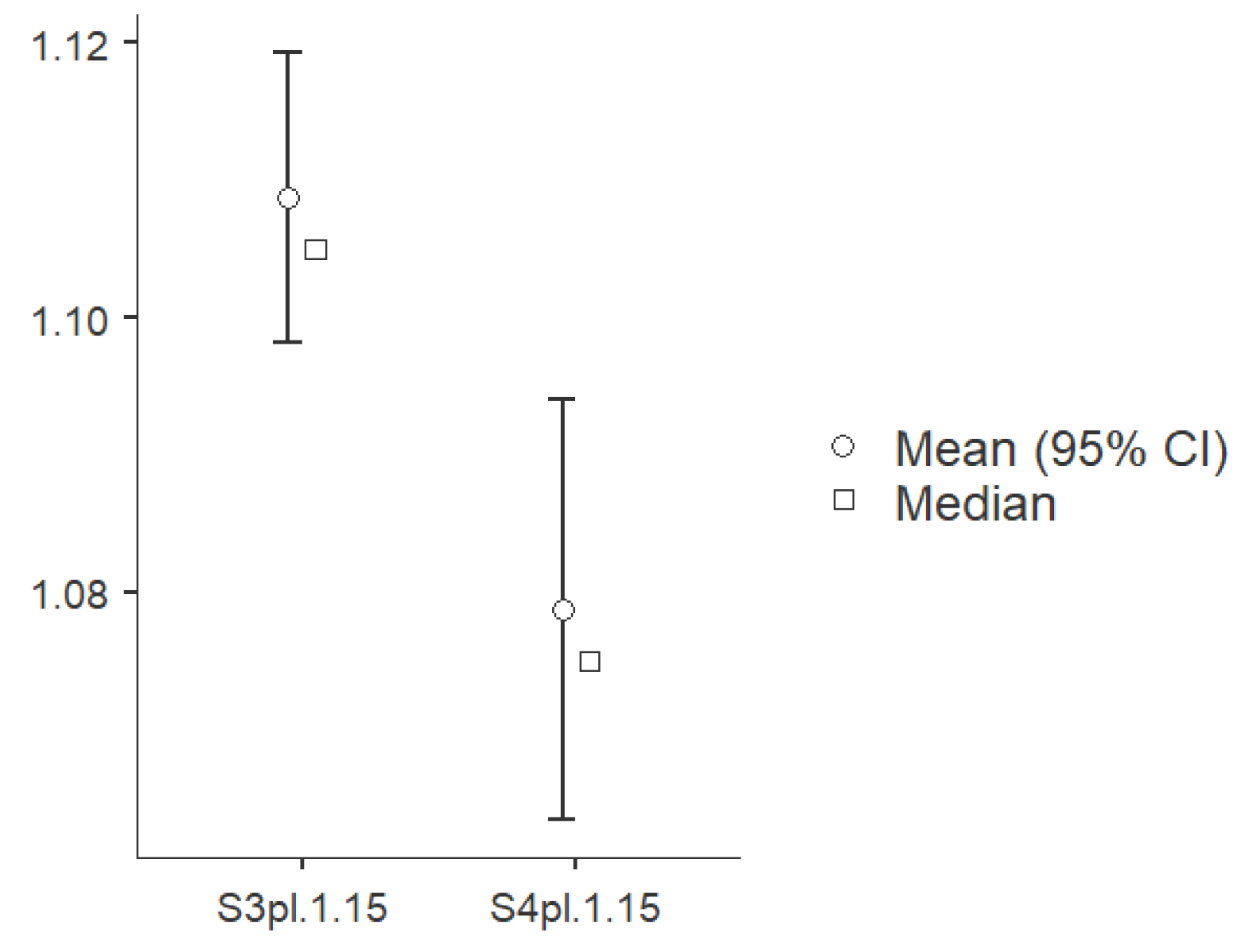

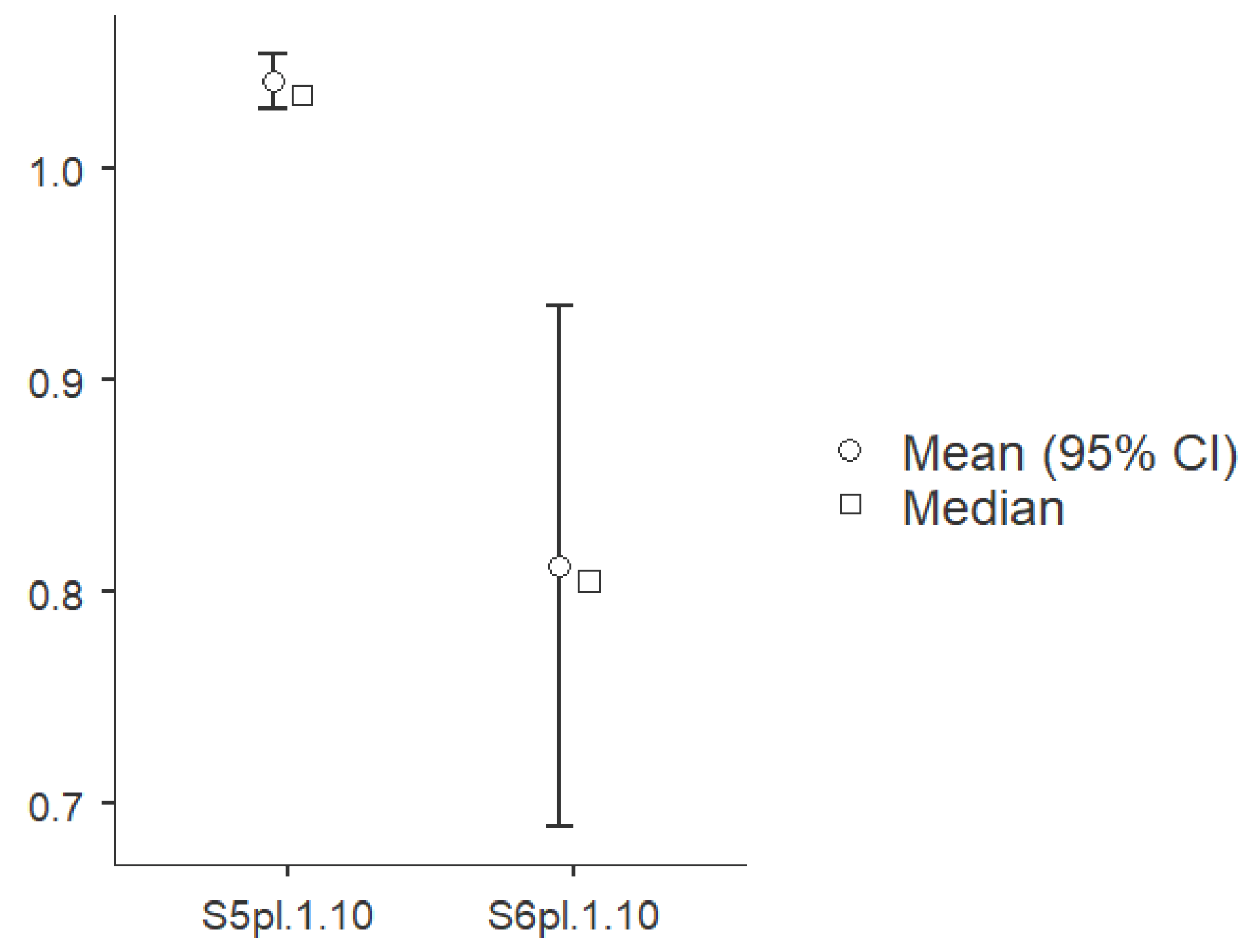

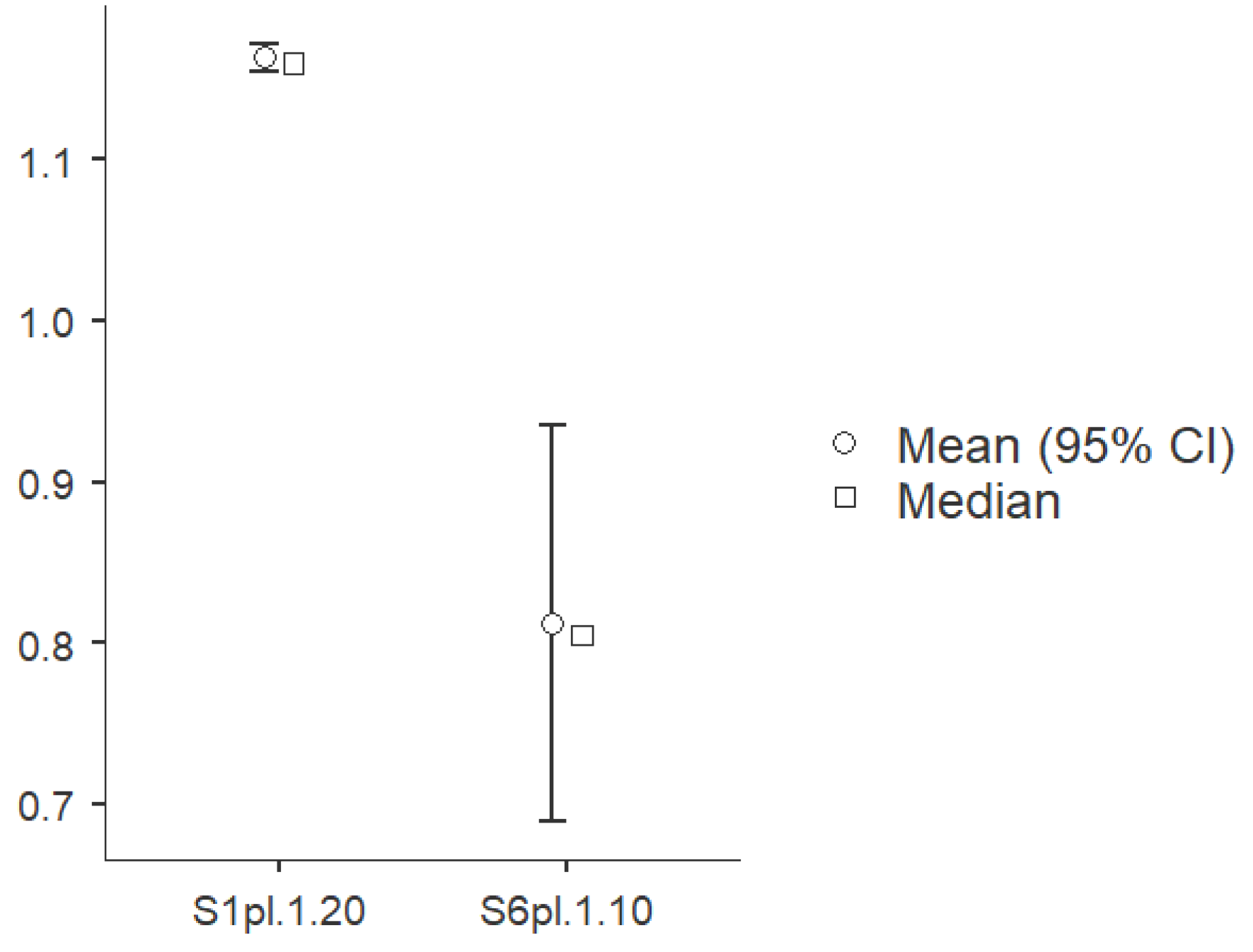

| Statistic W | p | Mean difference | SE difference | Effect Size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TI50m | TF50m | 136 | < .001 | 1.745 | 0.17606 | Rank biserial correlation | 1 |

| TI100m | TF100m | 136 | < .001 | 93.5001 | 9.36833 | 1 | |

| S1pl.1.20 | S2pl.1.20 | 136 | < .001 | 0.03 | 2.87E-17 | 1 | |

| S3pl.1.15 | S4pl.1.15 | 136 | < .001 | 0.03 | 0.00258 | 1 | |

| S5pl.1.10 | S6pl.1.10 | 105 | < .001 | 0.23 | 0.05713 | 1 | |

| S1pl.1.20 | 136 | < .001 | 0.3549 | 0.05911 | 1 | ||

| Note. Hₐ μ Measure 1 - Measure 2 ≠ 0 | |||||||

| ᵃ 2 pair(s) of values were tied | |||||||

| Week Subjects |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.15 | 1.12 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 0.57 | |

| 1.17 | 1.14 | 1.12 | 1.1 | 1.05 | 1.04 | |

| 1.20 | 1.17 | 1.15 | 1.13 | 1.1 | 1.1 | |

| 1.15 | 1.12 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 0.57 | |

| 1.17 | 1.14 | 1.12 | 1.1 | 1.05 | 1.04 | |

| 1.15 | 1.12 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 0.57 | |

| 1.15 | 1.12 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 0.57 | |

| 1.20 | 1.17 | 1.15 | 1.13 | 1.1 | 1.1 | |

| 1.17 | 1.14 | 1.12 | 1.1 | 1.05 | 1.04 | |

| 1.15 | 1.12 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 0.57 | |

| 1.17 | 1.14 | 1.12 | 1.1 | 1.05 | 1.04 | |

| 1.15 | 1.12 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 0.57 | |

| 1.15 | 1.12 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 0.57 | |

| 1.17 | 1.14 | 1.12 | 1.1 | 1.05 | 1.04 | |

| 1.17 | 1.14 | 1.12 | 1.1 | 1.05 | 1.04 | |

| 1.15 | 1.12 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 0.57 | |

| Average | 1.16 | 1.13 | 1.11 | 1.08 | 1.04 | 0.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).