1. Introduction

Despite continuous developments in regional anesthesia, with new types and approaches to nerve blocks described in literature and conferences almost daily, the way in which we, as practicing anesthesiologists, can determine whether the nerve block has been successful, has not changed significantly in the last 100 years. It is still based on subjective observations – the patient's own reported sensations, the onset of motor blockade, and the disappearance of sensation in the anesthetized regions. Often, it can take a long time for these changes to occur, and the patient is not always able to adequately assess their feelings or inform the anesthesiologist about them, which results in the patient suffering pain during or after surgery in the event of an undiagnosed, unsuccessful nerve block.

N. Ischiadicus block, performed through both proximal and distal accesses, has long proven itself to be an invaluable, effective pain relief option for moderately and severely painful surgeries of the lower leg distal portions. It effectively reduces pain and opiate consumption to a minimum, especially when using a perineural catheter [

1], and can be combined with femoral or saphenous nerve blocks for complete anesthesia of the distal part of the lower leg [

2]. Compared to the alternative - ankle blocks - it can reduce pain levels by an average of 1.5 points more and lasts longer (up to 20 hours compared to 14.5 hours) [

3]. An experienced operator using ultrasound guidance achieves success in 90%–95% of cases with the supra-popliteal approach [

4]. However, this also means that up to 10% of patients experience block failure, consistent with Barrington et al.'s large retrospective study showing that approximately 10% of general PNBs fail [

5].

But the problem lies not in the fact how we perform regional anesthesia, but rather that there is no objective, quantitative method for timely detection of failed nerve blocks (FNB).

One method that could be used to address this problem is thermography. It is a non-invasive, quantitative method based on the objective analysis of thermographic images, which, when viewed, would lead any two or more independent observers to the same conclusion.

Our options to diagnose failed PNB in clinical practice are limited, subjective and often inaccurate [

6]. Their effectiveness is influenced by the operator's understanding of skin innervation areas, each patient's individual sensations and anatomy, and, often in clinical practice, the limited turn-over time between surgeries.

Thermography is not new and has already proven itself in regional anesthesia [

7]. However, its wider application in clinical practice is currently limited by many unanswered practical questions. In our study, conducted at the Hospital of Traumatology and Orthopedics, we attempted to answer some of these questions. The aim of the study was to determine how different local anesthetics affect the rate of skin temperature changes after the popliteal sciatic nerve block, observing these changes with a thermographic camera.The primary research objective of the study was to explore how different local anesthetics will affect the speed of onset for thermographic skin changes. The secondary objectives were to analyze obtained data, extrapolate our findings for clinical practice and evaluate the thermography method feasibility for detecting PNB failures in acute bone fractures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

From November 30, 2024, to April 30, 2025, a prospective, randomized study was conducted at the Traumatology and Orthopedics Hospital in Riga. The study was conducted in accordance with the permission of the Ethics Committee of the Hospital of Traumatology and Orthopedic, application No. 49/2024/1 and follows the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines.

Both acute and elective surgical patients were enrolled. All the patients had surgery on the distal portion of the lower extremity scheduled and according to both international and Hospital of Traumatology and Orthopaedics guides of best practices, had indications for N. Ischiadicus blocks to ensure postoperative analgesia. Additional inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found here (

Appendix A1).

All the patients were divided into three groups depending on local anesthetic used (Group B, Group R, Group L). Each group consisted of 20 patients. Randomization was done by using a free online randomizing tool. In group B - 20 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine anesthetic was used; Group R - 20 ml of 0.375% ropivacaine anesthetic; Group L - 20 ml of 1% lidocaine anesthetic.

The fixed doses and concentrations of local anesthetics were specifically selected based on information available in the literature on the potency of each local anesthetic with the aim of ensuring their equal equipotency [

8] when performing nerve blocks.

Patients who met the study criteria received full information and signed a consent form, which explained the study and its objectives. In addition, all patients signed the standard form of the Hospital of Traumatology and Orthopedics, consenting to anesthesia and surgical manipulation. Prior to arriving at the pre - operative room, each patient received premedication - Tab. Eterocoxibum 90 mg p/o and Tab. Midazolamum 7.5 or 3.75 mg (based on age and comorbidities) p/o for anxiolysis. Each patient was assigned a number from 1 to 60 and included in one of the three randomized groups.

2.2. Procedure

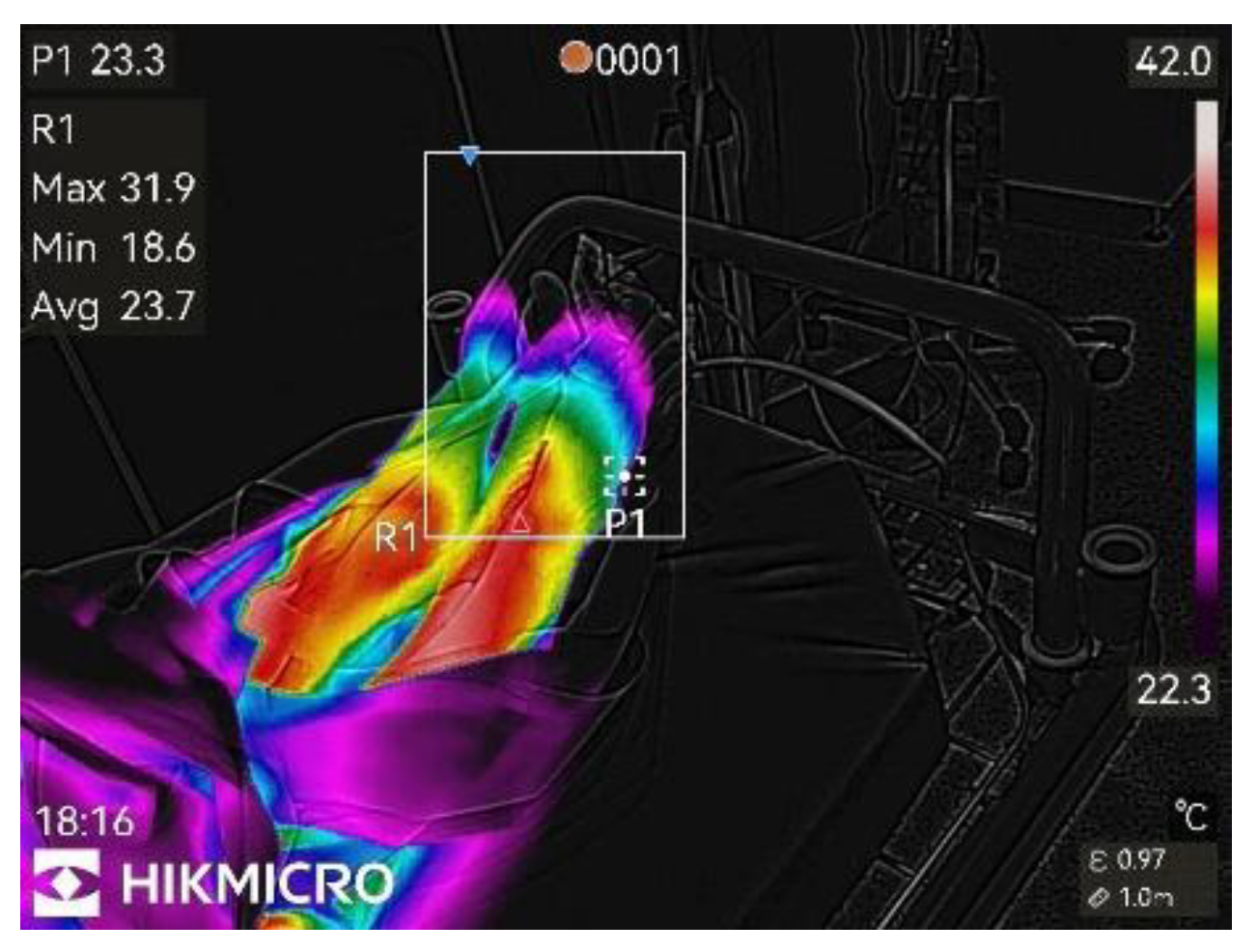

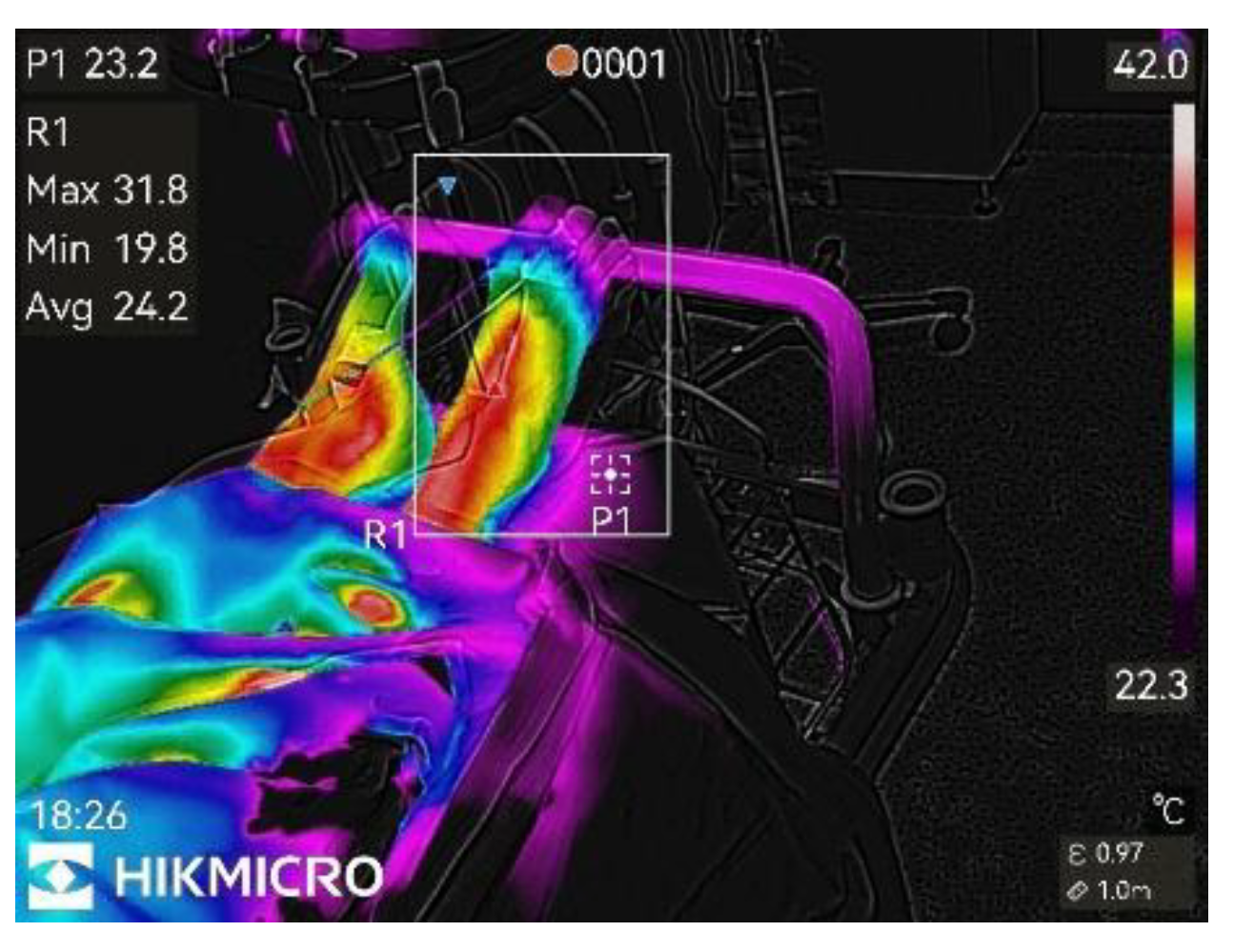

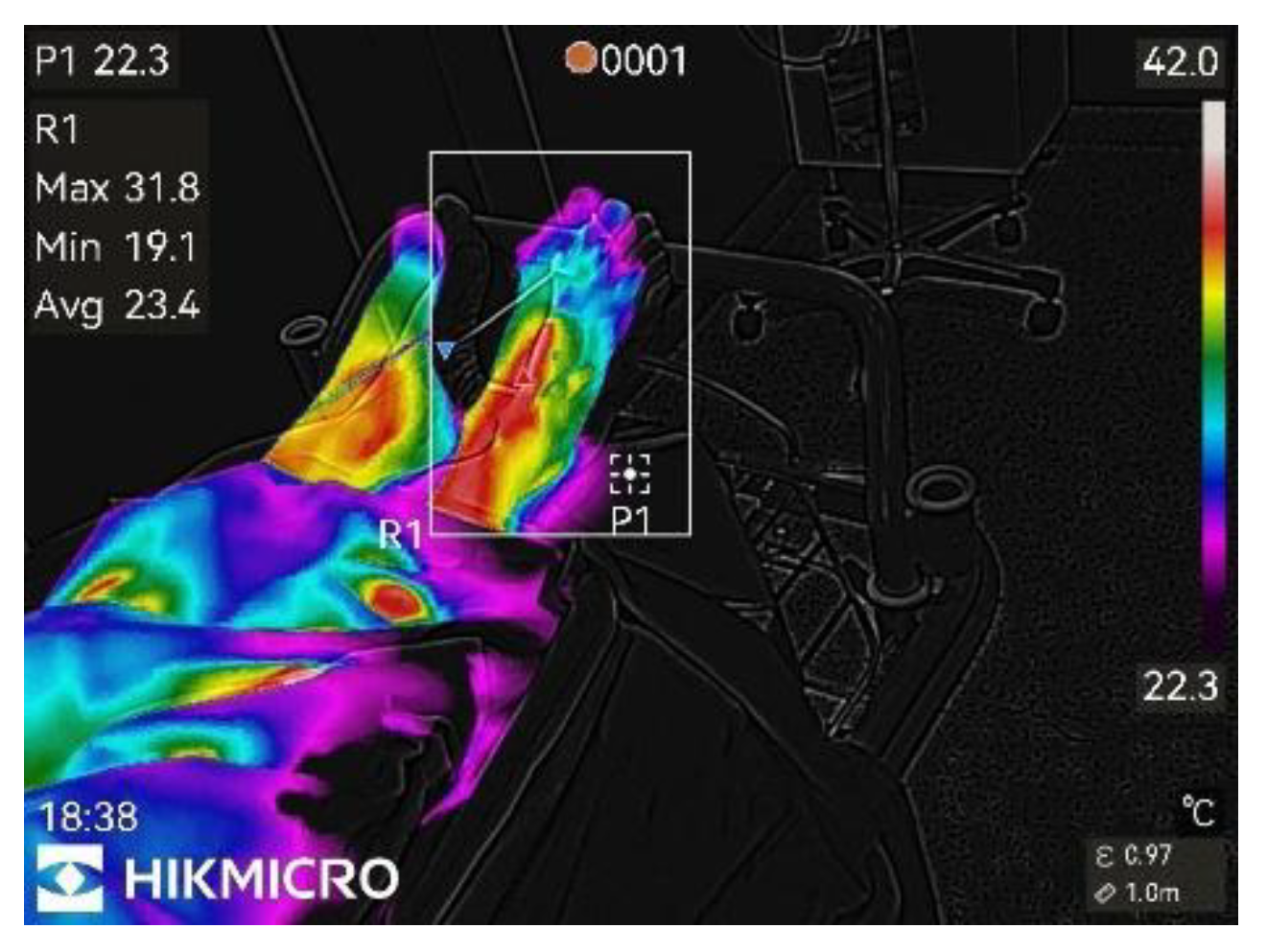

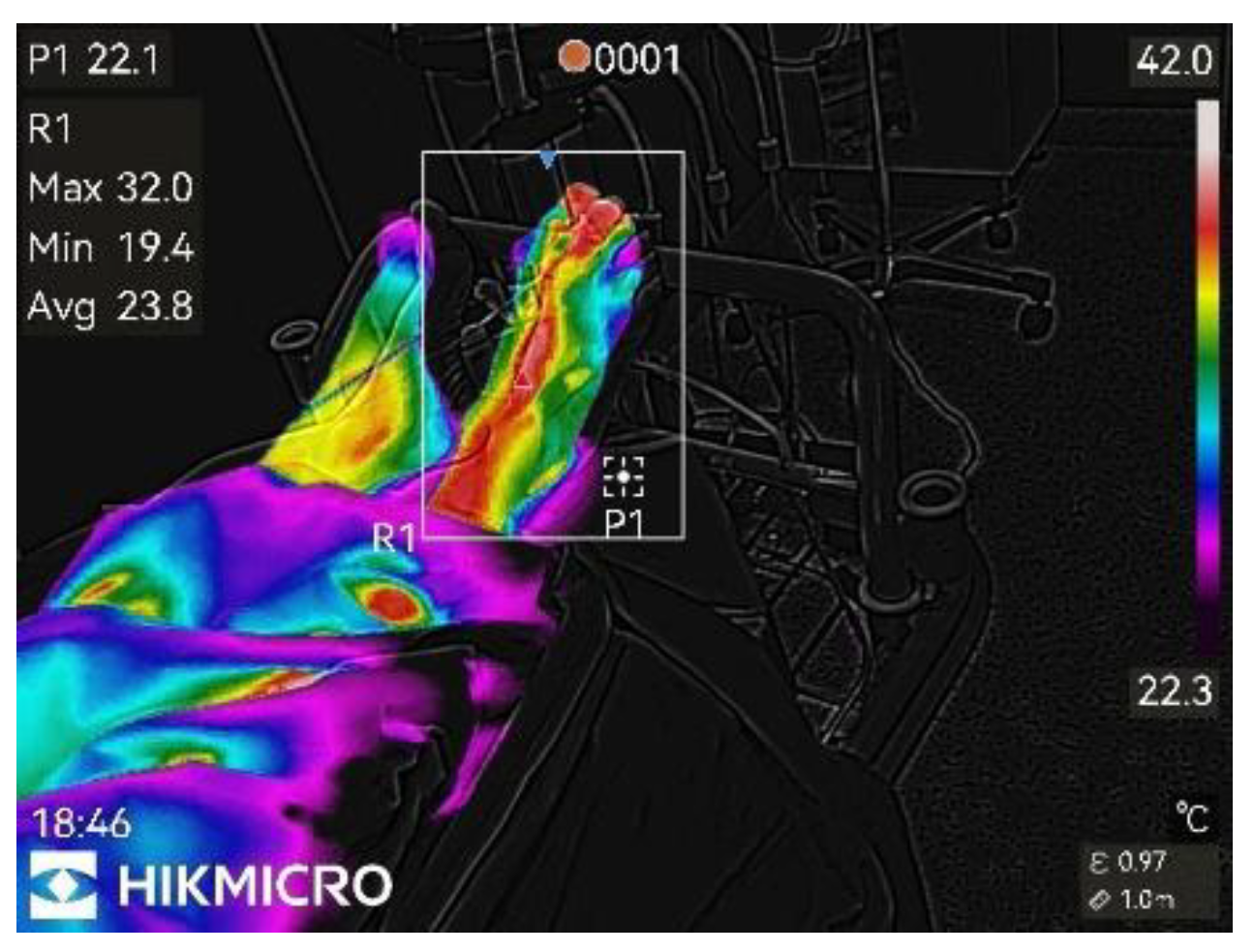

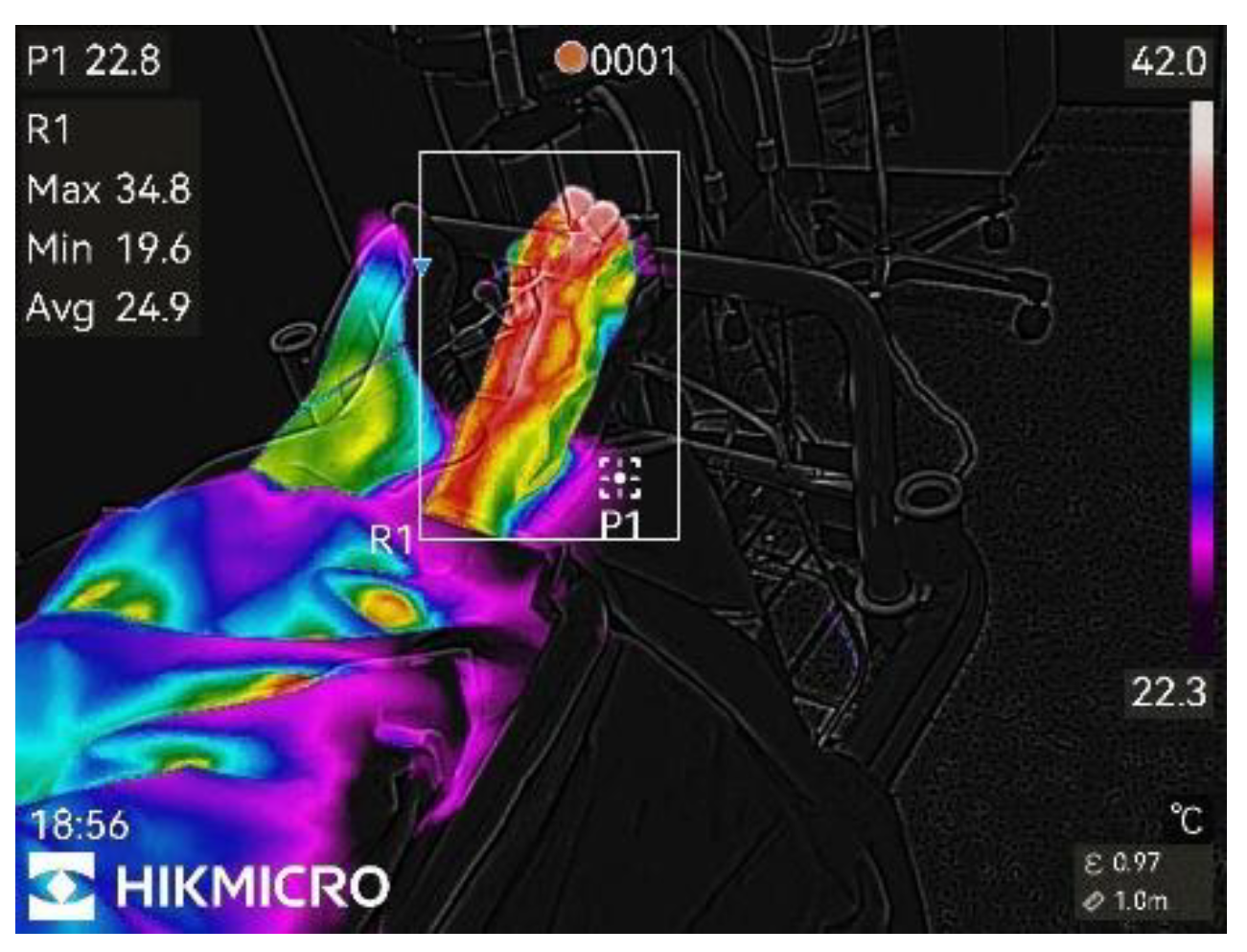

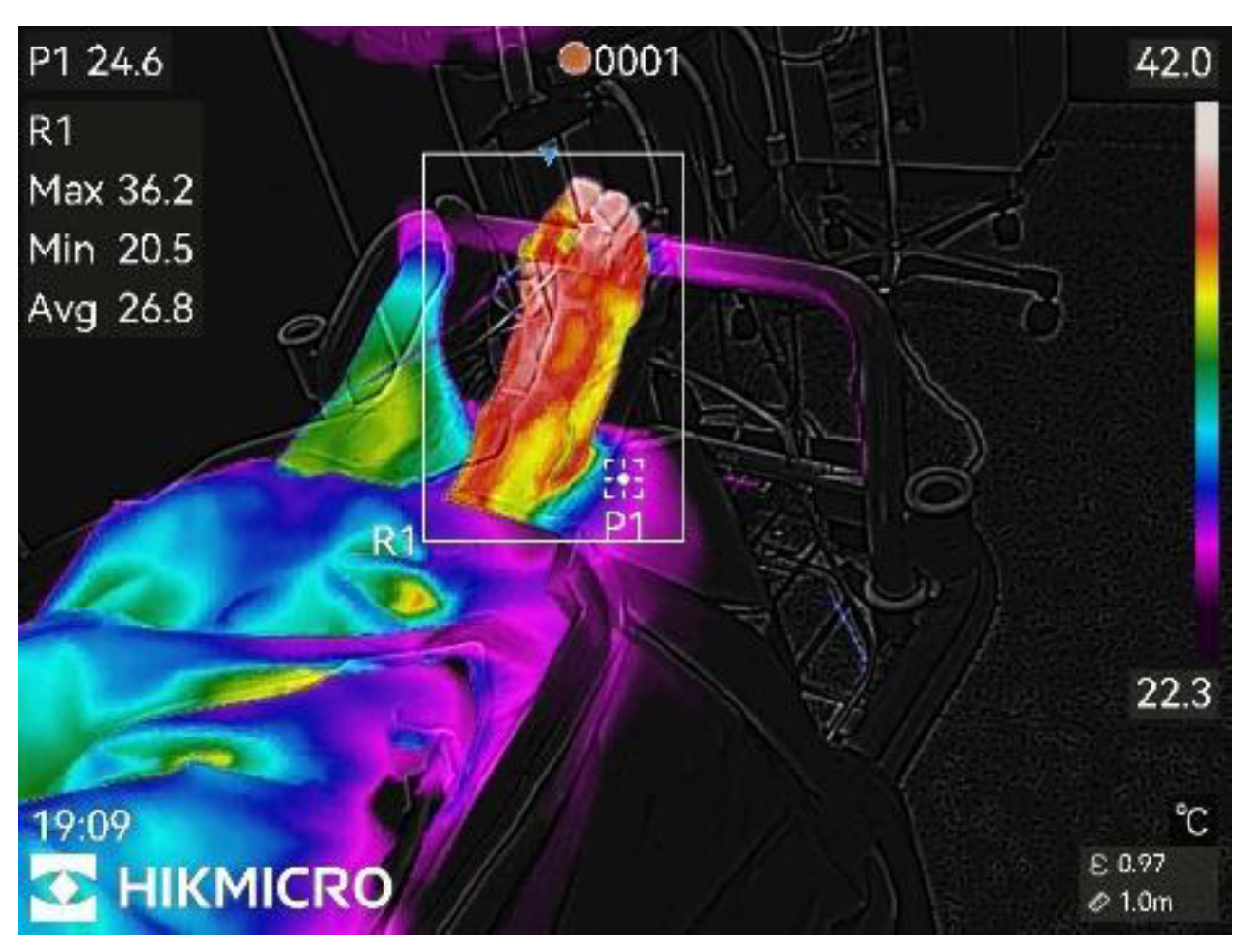

After arrival, all patients had the surgical site exposed up to the knee level for 15 minutes to ensure temperature equilibrium with the environment, as recommended by international medical thermography guidelines [

9]. The ambient temperature in the preoperative preparation room remained constant at 22 degrees Celsius throughout the study. After 15 minutes, the first image was taken with a thermography camera (HICKMICRO SP60), after which a N. Ischiadicus block in the suprapopliteal approach was performed. Both ultrasound guidance and nerve stimulator were used during the procedure. Each patient received a fixed dose of 20 ml of the local anesthetic prescribed for the respective group. Immediately after the block was performed and every minute thereafter, up to and including 45 minutes, thermographic images were taken of the anesthetized patient's extremity. In total, there were 47 thermographic images for each patient (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 shows thermographic pictures obtained for single patient in an elective group, when bupivacaine was used).

In addition, a skin thermometer was attached to the anesthetized extremities toe, which ensured continuous temperature measurement, and every 3 minutes a sensation test was performed on the dorsal part of the foot with ice until the sensation of cold completely disappeared. All this data were recorded and used as additional confirmation of the success of the block (the main criteria for the success of the nerve block remains visible local anaesthetic spread around the nerve in Vloka fascial sheath).

2.3. Statistical Analysis and Data Storage

The images obtained were stored on a camera and then uploaded to Google Drive, from where they were analyzed using the official HICKMICRO free thermography image analysis application HICKMICRO ANALYZER V1.7.1. The data was recorded in MS Office Excel (Microsoft 365) format. Statistical analysis was performed in IBM SPSS 29.0 by employees of the Statistics Laboratory at the University of Latvia.

Wilcoxon range tests, Spearman rank correlations were used to compare quantitative variable data. Linear regression methods were used for scalar reactions and variable correlations. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Total Population

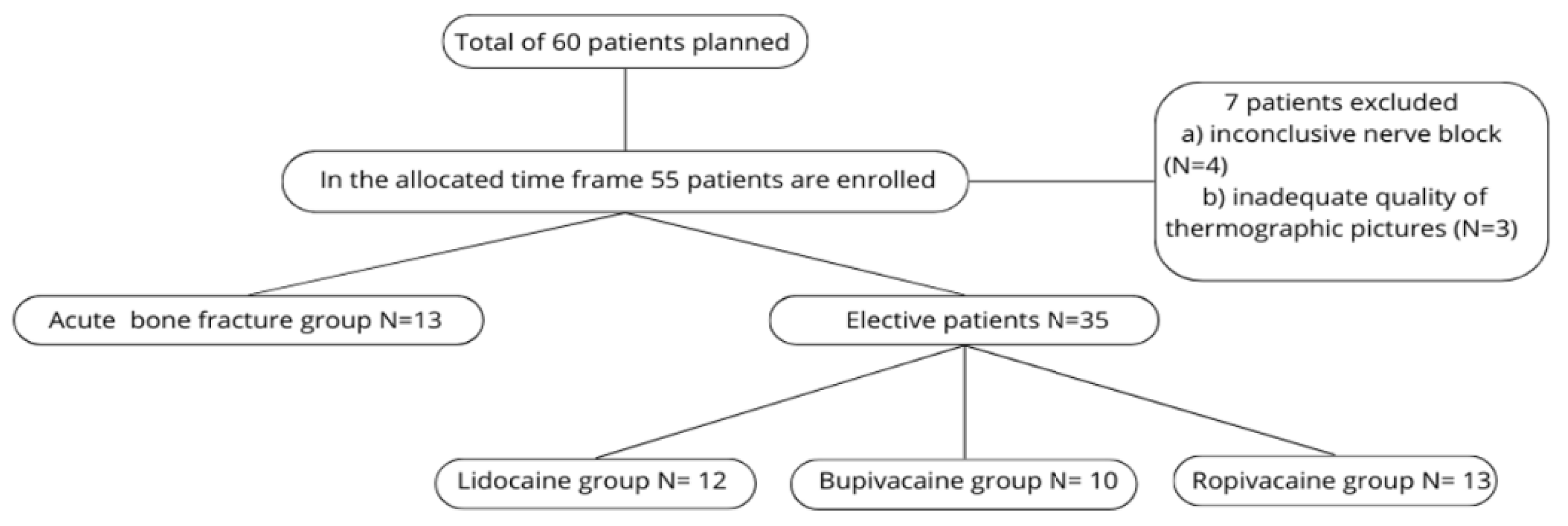

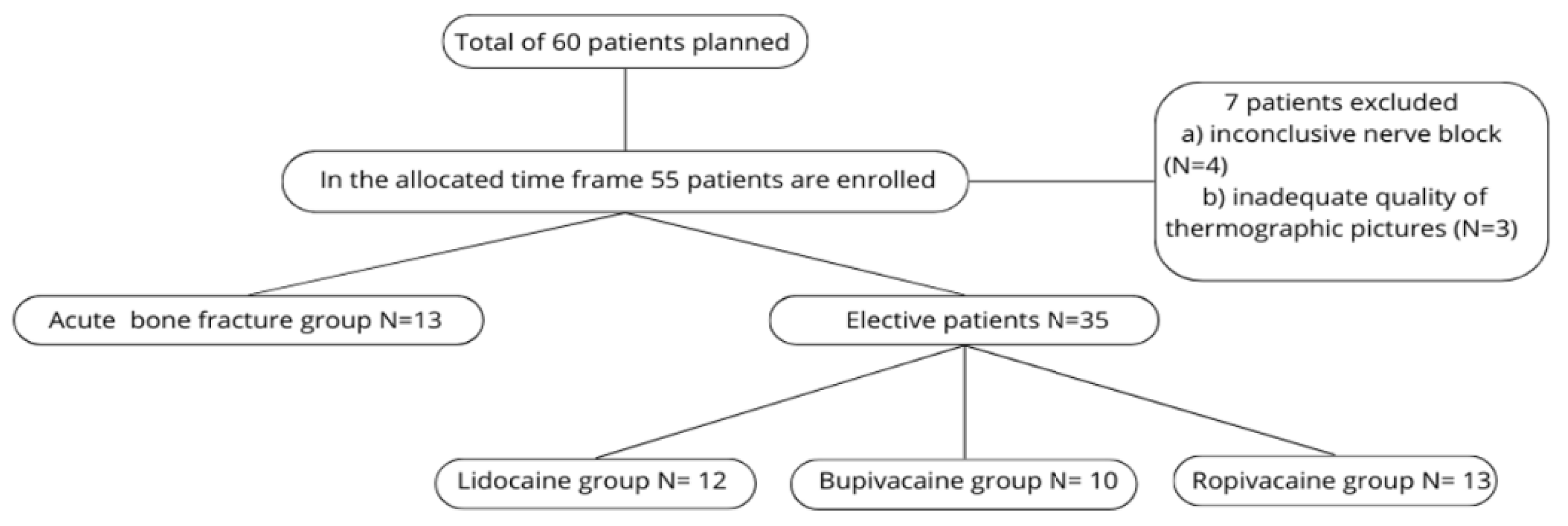

During the study period, 55 of 60 planned patients were enrolled; 7 were later excluded due to inconclusive nerve blocks or poor-quality thermography images. In total, 48 patients were analyzed.

During data analysis, we further divided those 48 patients in 2 large groups: patients with acute bone fractures (N=13) and patients undergoing elective surgery without acute bone fractures (N=35).

For elective patients, three sub-groups (Group L, Group B, Group R) were retained for data analysis. For acute fracture patients, due to the relatively small total number, all three groups were combined and analyzed as one group.

Flowchart of patient population.

3.2. Primary Outcome

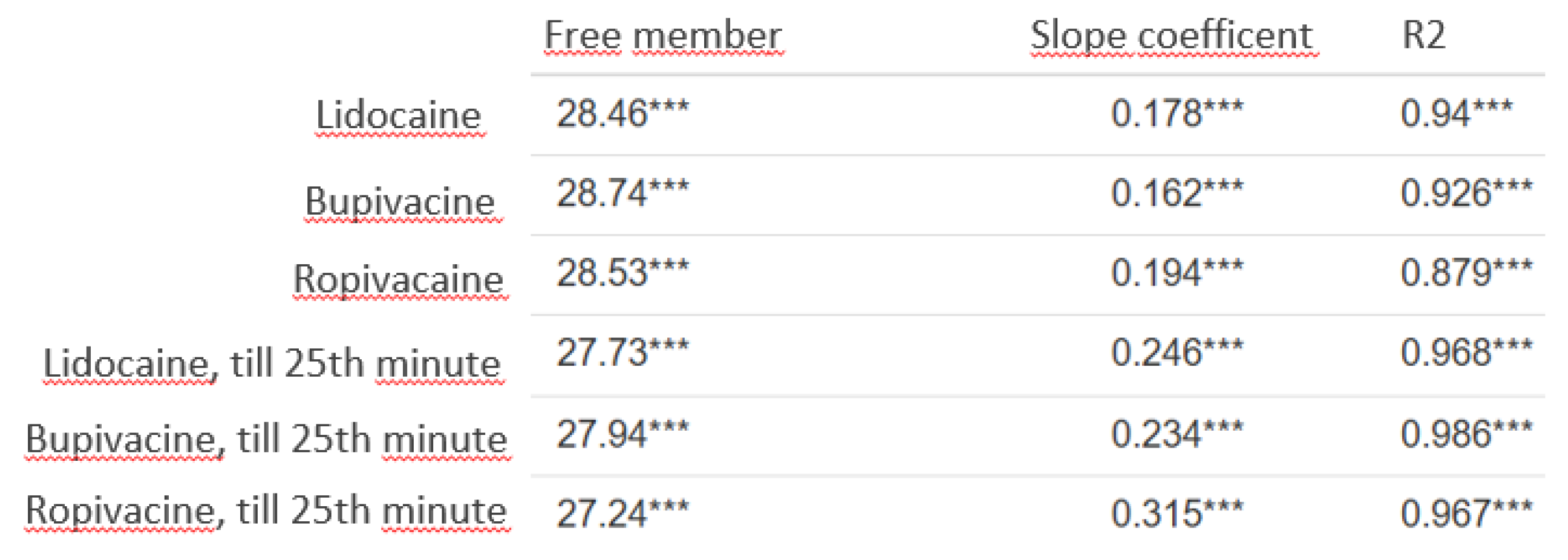

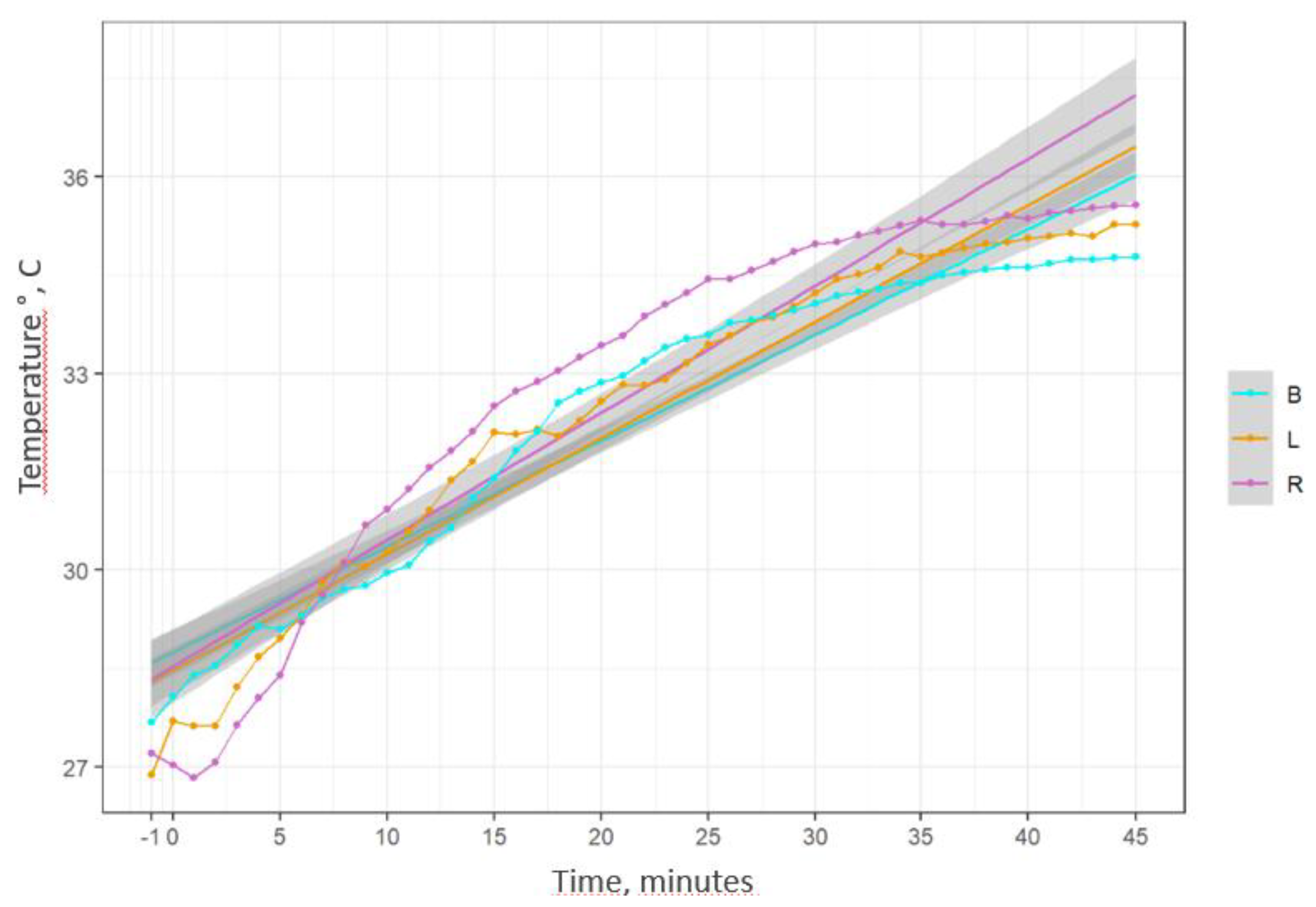

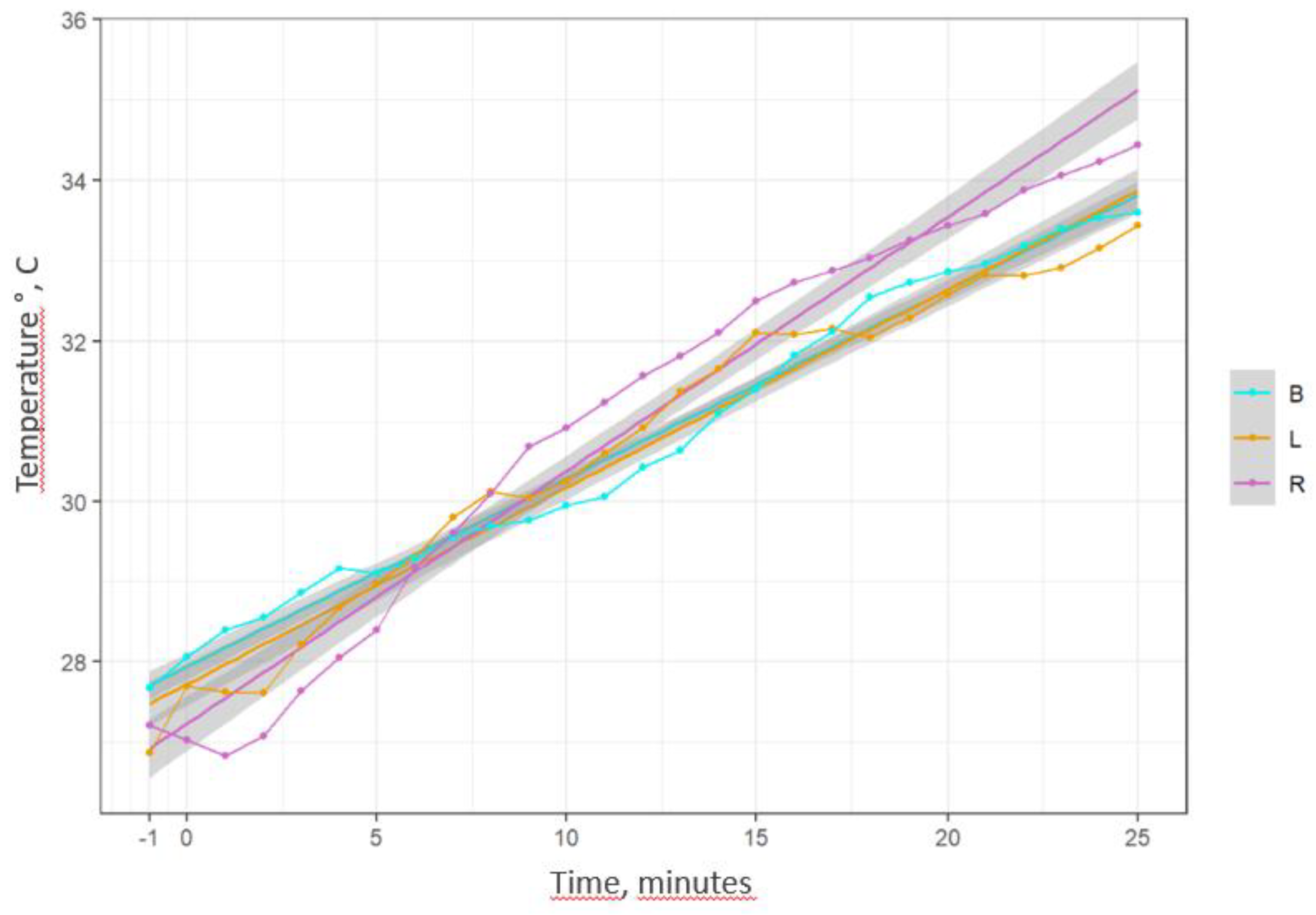

To determine if there is a difference between the three LAs and the rate of skin temperature increase, we used linear regression. In statistics, linear regression is a model that estimates the relationship between a scalar response and one or more explanatory variables. In this study, linear regression was used to show correlation between time and temperature increase. The higher the slope value, the steeper the curve, i.e., the faster the temperature increase in the respective time unit.

The coefficient of determination (r squared) of the obtained linear regressions in our study was very high in all cases, especially when looking at the results up to the 25th minute, when the temperature increase is the fastest, which indicates that the models obtained in all groups will be able to predict the temperature increase with very high accuracy (

Appendix A2). The data obtained shows that when observing values up to 45 minutes, the average skin temperature increase is relatively similar in all groups. Higher slope coefficient can be observed in the ropivacaine group (slope coefficient -SC- 0.194), followed by the lidocaine group (SC 0.178) and the bupivacaine group (SC 0.162). When observing the results only up to the 25th minute, a greater difference appears; in this case, the slope coefficient of ropivacaine is significantly higher than the rate of increase of the other two local anesthetics (SC 0.315) compared to bupivacaine (SC 0.234) and lidocaine (SC 0.246). These results are also shown in a graph in

Appendix A3 and

Appendix A4.

3.3. Secondary Outcomes

One of the most important questions for clinical usage of thermography is - how long it takes for statistically significant changes in skin temperature to occur when using a thermographic camera? To answer this question, we used Wilcoxon-signed range tests. Taking a significance level of α=0.05 or less, the shortest time when the first statistically significant changes appear in the lidocaine group is 15 minutes, in the bupivacaine group - 15 minutes, and in the ropivacaine group - 10 minutes. It is worth noting that in the lidocaine group, the α value was already very close to 0.05 (0.057) at 10 minutes (

Appendix A5). This is consistent with the previously observed results for linear regressions, where the average temperature increase in the ropivacaine group was the most rapid, followed by the lidocaine and bupivacaine groups. If we use these obtained time points for statistically significant temperature changes, we can estimate the degree of temperature increase that will be observed at these cut-off times. For example, for ropivacaine, the total temperature increase at 10 minutes will be 3.709C compared to the pre-block temperature, for lidocaine, the increase at 10 minutes will be 3.392C, while bupivacaine will have the smallest increase, only 2.28°C at 10 minutes (

Appendix A6).

Another important question for clinical practice is - how does the initial skin temperature influence the rate of increase for the skin temperature? An empirical hypothesis was put forward that the lower the outgoing skin temperature, the faster the observed temperature increase after nerve block. Spearman's rank correlation test was used to prove the hypothesis. It showed that there is a statistically significant and strong negative correlation between pre-block temperature and the average rate of temperature change (ρ=−0.855, P<.001), i.e., the lower the skin temperature in the area of interest before regional anesthesia, the faster the temperature changes will be observed (

Appendix A8).

As for the feasibility of using a thermography method for detecting PNB failure in acute bone fracture - we also chose the Wilcoxon range tests. Due to the small total number of patients in this group (N=13) separate subgroups were not identified. An attempt was made to answer only one main question: will a statistically significant change in temperature be observed in cases of acute bone fractures? All patients in this group had an initial skin temperature higher than 32°C in the regions of interest. Taking a significance level of α=0.05 or less, the shortest time when the first statistically significant changes appear is 25 minutes. This confirms that statistically significant temperature changes will also be observed in acute bone fractures after peripheral nerve block (PNB) using the thermography method (

Appendix A7).

4. Discussion

Thermography is an appealing possible alternative to commonly used tests. It has already been studied in various peripheral and centroaxial blocks before.

For our study, after literature review and based on the specifics of our hospital workflow, we chose the N.Ischaidicus block in the supra-popliteal approach as the nerve block of choice, as the thermography method has already proven itself in this type of blocks [

10,

11].

It is known that each local anesthetic has its own onset speed and duration. The literature describes that lidocaine has the fastest onset, followed by ropivacaine and bupivacaine. This is based on the pharmacodynamic parameters of the substances - pKa, lipophilicity, molecular size. However, both the onset speed and duration of action are also influenced by other factors - mainly LA concentration and total volume around the nerve [

12]. To obtain accurate data on how different local anesthetics affect the rate of change in skin temperature, these two additional factors were eliminated in this study by using a fixed volume and equipotent LA concentrations.

The author's study analyzed and included only patients in whom nerve block was considered successful. This was determined by the following parameters: convincing local anesthetic distribution around the nerve under ultrasound control, positive sensory block with ice (loss of temperature sensation), temperature increase around the toe, measured continuously with a non-invasive skin thermometer.

Based on a review of the available literature, it was expected that lidocaine would have the fastest onset of action and, consequently, the fastest temperature increase [

13], followed by ropivacaine and bupivacaine [

14].

Using linear regression, in our study, we found that the fastest temperature increase up to 45 minutes was in the ropivacaine group (slope coefficient -SK- 0.194), followed by the lidocaine group (SK 0.178) and the bupivacaine group (SC 0.162).

When observing the results only up to 25 minutes, a greater difference appears; in this case, the slope coefficient of ropivacaine is significantly higher than the rate of increase of the other two local anesthetics (SC 0.315) compared to bupivacaine (SC 0.234) and lidocaine (SC 0.246). In this case, it could be explained that the true equipotent concentration of ropivacaine would be 0.33%, not 0.375%, which we used in the study. However, the fact that the slope coefficients in the lidocaine and bupivacaine groups were so similar would suggest that the rate of temperature change is influenced directly by concentration and volume (or "strength"), rather than pKa or other pharmacodynamic parameters.

Spearman's rank correlation revealed a statistically significant and strong negative correlation between pre-block temperature and mean rate of temperature change (ρ=−0.855, P<.001). The finding of a negative correlation is consistent with the findings of other authors that effective temperature increase after nerve block requires initial vasoconstriction in the region under study [

2].

A clinically very important question is how much time must pass after a nerve block is performed for a statistically significant change in temperature to be observed?

It would be more meaningful to also view these changes in comparison with the previous different author study findings of the onset of sensory changes following the nerve block. Kim HJ et al. in their study using 0.375% ropivacaine and 0.25% levobupivacaine in infraclavicular blocks found that sensory block with ropivacaine occurs on average in 15-22.5 minutes, while levobupivacaine takes 17.5-35 minutes [

15].

Cuvillon et al. used various combinations of LA, as well as ropivacaine and bupivacaine separately, in their study on N.Ischiadicus blocks [

16]. The study found that sensory-motor block occurred in 23 +/- 12 minutes in the ropivacaine group and in 28 +/- 12 minutes in the bupivacaine group. It should be noted that this study used much higher doses of LA than ours - ropivacaine for the N. Ischiadicus block 150 mg (authors 75 mg), bupivacaine 100 mg (authors 50 mg).

Less is known about the speed of action of lidocaine in PNB. It is usually used either in distal infiltration blocks (fingers, ankles) or in combination with various other LAs to determine whether it accelerates the speed of action. Almasti et al. compared the onset speed of lidocaine and bupivacaine at different concentrations in axillary and supraclavicular nerve plexus blocks in their study. Using a fixed amount of 0.4 ml/kg, it was found that 0.66% lidocaine, without combining it with other LAs, has a speed of onset of 13.0 ± 1.02 minutes [

17].

Gamal M et al, using a 1:1 mixture of 0.5% bupivacaine and 2% lidocaine in supraclavicular nerve blocks and measuring changes with a thermographic camera in the relevant areas of the hand, found that a significant increase in temperature was observed in virtually all nerves after 15 minutes meaning that in all cases, a successful nerve block could be assessed after 15 minutes. In contrast, sensory-motor blocks often occurred only around the 30-minute mark [

18]. Asghar S. et al studied thermographic changes after infraclavicular axillary nerve block and found that if the temperature between the 2nd and 5th fingers of the hand was < 30°C 30 minutes after the block, this meant a failed block in 100% of cases [

19].

In our study we used Wilcoxon rank tests to determine at which point in time we could observe statistically significant temperature changes. Choosing a significance level of α=0.05 or less, the shortest time when the first statistically significant temperature changes appear is 15 minutes in the lidocaine group, 15 minutes in the bupivacaine group, and 10 minutes in the ropivacaine group. It is worth noting that in the lidocaine group, the α value was already very close to 0.05 (0.057) at 10 minutes. In terms of absolute temperature increase figures, the total temperature increase for ropivacaine at 10 minutes will be 3.709°C compared to the pre-block temperature, for lidocaine at 10 minutes it will be 3.392°C, while bupivacaine will have the smallest increase, only 2.28°C at 10 minutes (3.72°C at 15 minutes). In short, our results correlate with those obtained by Gamal M et al.

In the acute fracture group, using Wilcoxon rank tests, assuming a significance level of α=0.05 or less, the shortest time when the first statistically significant changes appeared, was 25 minutes. This is consistent with previous studies - the lower the initial temperature, the slower the temperature increase, and in all cases of acute fractures, the initial temperature was 32°C or higher. Der Strasse et al., using a thermographic camera for diagnosing acute bone fractures in a hospital emergency department, found that in acute, combined lower leg fractures, the temperature difference between the two legs can be as high as 4.5°C, which corresponds to the high skin temperature observed in our study[

20]. Since some starting temperatures were nearly 34°C or higher, the overall increase was minimal and inconclusive, as the maximum temperature cannot surpass a human's core temperature of 36.6°C.

To authors knowledge, this is the first study that explores how different local anesthetics affect skin temperature changes and onset times in PNB when using the same nerve block, equipotent LA concentrations and evaluates the methods feasibility for detecting the PNB failure in acute bone fractures. If this method will ever be adopted for regular clinical use, these are some of the most important questions that need to answer beforehand.

5. Conclusions

The study found no clinically significant differences between skin temperature increases using thermography and 3 different equipotent doses of LA.The rate of temperature increases when using equipotent doses of local anesthetic is primarily determined by the initial temperature in the anesthetized skin area (Due to this reason, for practical purposes, using this method for diagnosing failed nerve blocks in acute bone fractures is not recommended as in this the initial vasodilation at fracture sites is high leading to high starting temperature, therefore any increase in temperature is comparatively small if any. Finally, after a nerve block at least 15 minutes should pass before assessment of the block failure can be made using the local anesthetic concentrations used in our study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, Andrejs Zirnis, Aleksejs Miščuks; validation Iveta Golubovska.; investigation Andrejs Zirnis, Everita Bīne, Valērija Kopanceva, Valentīna Sļepiha resources Uldis Rubīns; data curation Uldis Rubīns, Andrejs Zirnis.; writing—original draft preparation, Andrejs Zirnis; writing—review and editing Iveta Golubovska; supervision Aleksejs Miščuks, Iveta Golubovska. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Thermography camera used in our research was obtained through the Latvian company ‘’Mikrotiks’’ research support grant, issued by University of Latvia Foundation (2024).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the permission of the Ethics Committee of the Hospital of Traumatology and Orthopedics, application No. 49/2024/1 (2024) and follows the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is based on and produced from the thesis of Andrejs Ernests Zirnis, MD, University of Latvia, Residency in Medicine Programme (2025). The abstract was presented at the 10th International Scientific Conference of the Baltic Society of Regional Anesthesia (2025) as an oral presentation.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors report no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SC |

Slope coefficent |

| PNB |

peripheral nerve block |

| LA |

local anesthetic |

| RA |

regional anesthesia |

| P/o |

per os |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion Criteria |

Exclusion criteria |

| Surgery for the distal part of the lower leg |

Patients refusal |

| Age 18-65 |

Repeated surgery on lower extremity |

| Body Mass Index 23-38 |

Nerve damage (trauma or other) |

| |

Decompensated diabetes (HbA1C > 8.5%) |

| |

Peripheral artery disease (Fontaine 2 or above) |

| |

Local infection in the region of surgery |

| |

Patients with sepsis |

| |

Bodyweight under 50 kilograms |

| |

Chronic kidney insufficiency 3B or higher degree |

Appendix A.2. Table Shows Linear Regression Models for all 3 of the Local Anesthetics Groups

This table shows R squared values and slope coefficients for all elective patient cohort. Additionally, on the lower part results only till the 25th minute were analyzed and showed much steeper slope coefficients with higher R squared values.

Appendix A3. Linear Regression Models for Different Local Anesthetics up till 45 Minutes

Colours B- bupivacaine, L - lidocaine, R - Ropivacaine.

Appendix A4. Linear Regression Models for Different Local Anesthetics up till the 25th Minute

Colours B- bupivacaine, L - lidocaine, R - Ropivacaine.

Colours B- bupivacaine, L - lidocaine, R - Ropivacaine.

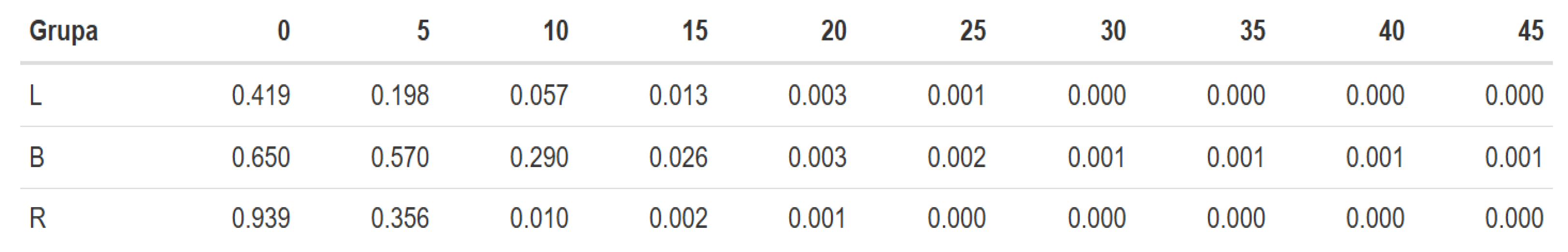

Appendix A5. Wilxocon Range for Test Elective Patient Cohort

Group : L - lidocaine, B- bupivacaine, R - Ropivacaine.

The upper line represents time in minutes after nerve block, where 0 is the first minute right after and 45 - 46th minute after nerve block. The rest of numbers represent α values.

Taking a significance level of α=0.05 or less, the shortest time when the first statistically significant changes appear in the lidocaine group is 15 minutes, in the bupivacaine group - 15 minutes, and in the ropivacaine group - 10 minutes.

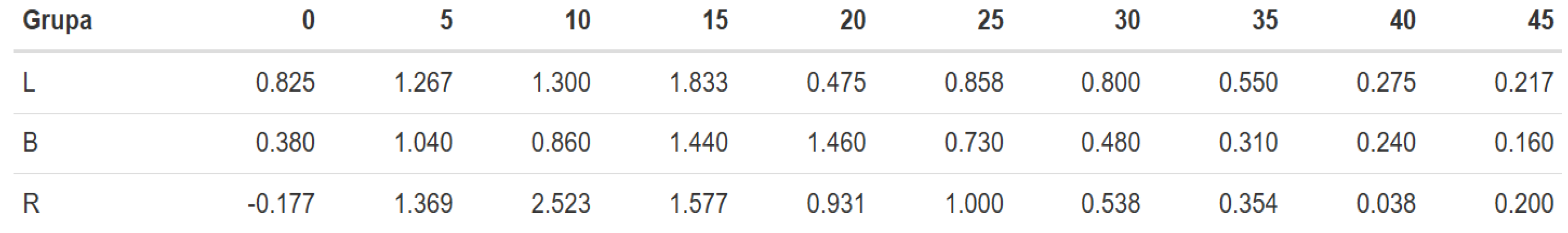

Appendix A6. Temperature Changes in Absolute Numbers Over Time

Group : L - lidocaine, B- bupivacaine, R - Ropivacaine. The upper line represents time in minutes after nerve block, where 0 is the first minute right after and 45 - 46th minute after nerve block. The rest of numbers represent absolute temperature increase in degrees.

This table shows absolute increase in temperature every 5 minutes, starting from 0 as the first minute after nerve block. I.e. in Lidocaine group at 0 (first minute) skin temperature increased by 0.825°C, at 5(6minutes) - for additional 1.267°C, in total summary increase during this time is 2.092°C.

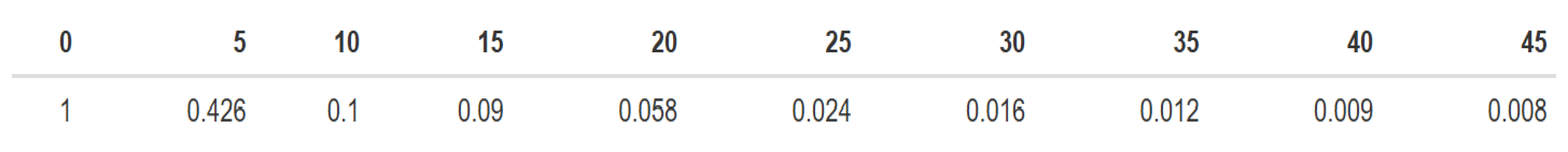

Appendix A7. Wilcoxon Range Tests for Acute Bone Fracture Group

The upper line represents time in minutes after nerve block, where 0 is the first minute right after and 45 - 46th minute after nerve block.

Statistically significant changes ( α=0.05 or less) can be seen after 25th minute.

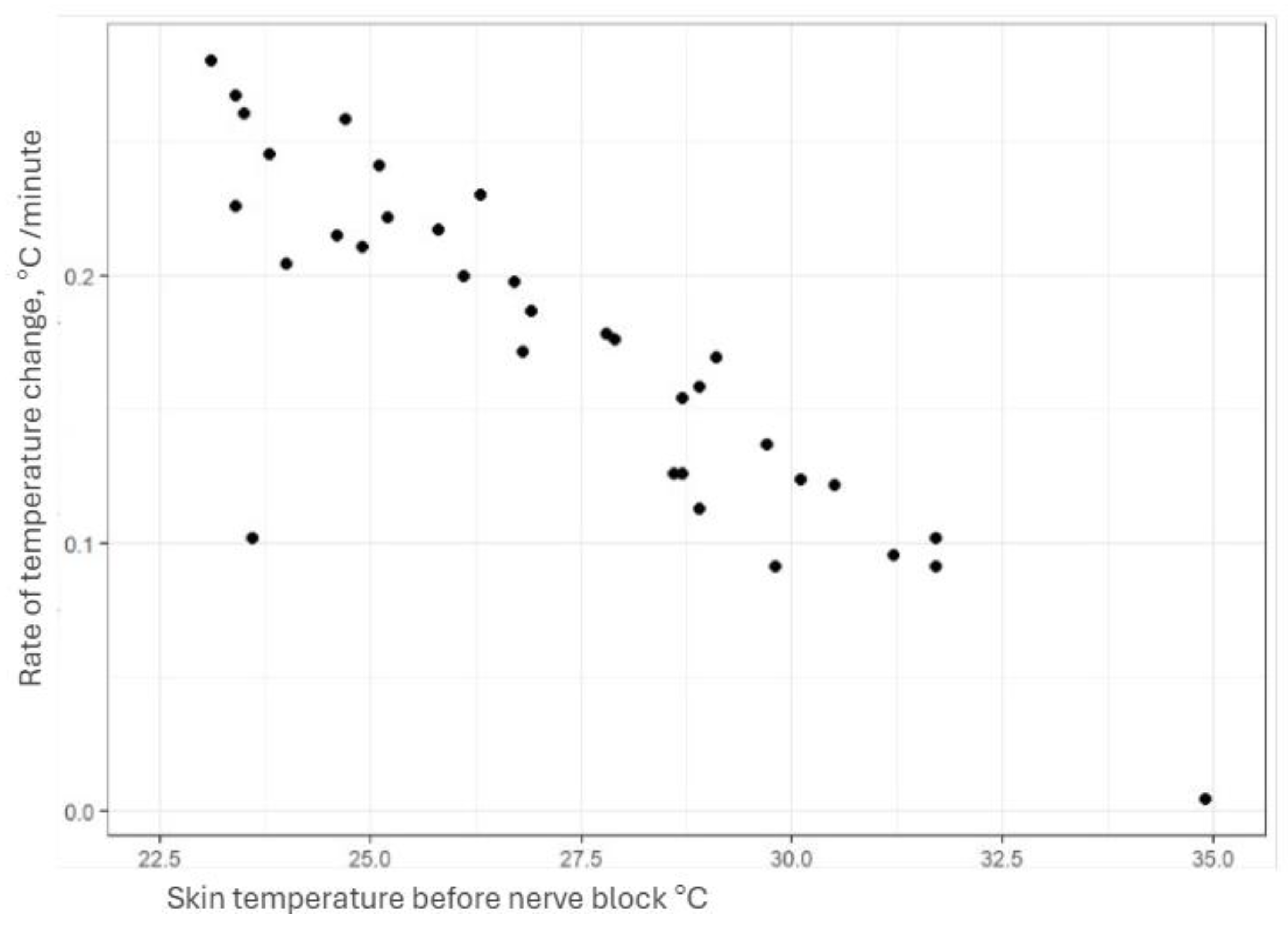

Appendix A8. Rate of Skin Temperature Changes, Based on the Initial Temperature

This graph shows how initial skin temperature influences the speed of subsequent temperature increase after nerve block. Each black dot represents a single case from our study.

References

- Continuous popliteal sciatic nerve block for postoperative pain control at home: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study.Ilfeld BM, Morey TE, Wang RD, Enneking FK. Anesthesiology. 2002 Oct;97(4):959-65. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combination Lower Extremity Nerve Blocks and Their Effect on Postoperative Pain and Opioid Consumption: A Systematic Review. Gianakos AL, Romanelli F, Rao N, Badri M, Lubberts B, Guss D, DiGiovanni CW. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2021 Jan-Feb;60(1):121-131. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ankle Block vs Single-Shot Popliteal Fossa Block as Primary Anesthesia for Forefoot Operative Procedures: Prospective, Randomized Comparison; Schipper ON, Hunt KJ, Anderson RB, Davis WH, Jones CP, Cohen BEFoot Ankle Int. 2017 Nov;38(11):1188-1191. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ultrasound guidance improves the success of sciatic nerve block at the popliteal fossa. Reg Anesth Pain Med. Perlas A, Brull R, Chan VW, McCartney CJ, Nuica A, Abbas S. 2008 May-Jun;33(3):259-65. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preliminary results of the Australasian Regional Anaesthesia Collaboration: a prospective audit of more than 7000 peripheral nerve and plexus blocks for neurologic and other complications. Barrington MJ, Watts SA, Gledhill SR, Thomas RD, Said SA, Snyder GL, Tay VS, Jamrozik K. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009 Nov-Dec;34(6):534-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monitoring regional blockade. Ode, K., Selvaraj, S. and Smith, A.F. (2017), Anaesthesia, 72: 70-75. [CrossRef]

- Assessment of skin temperature during regional anaesthesia - What the anaesthesiologist should know H. Hermanns, R. Werdehausen, M. W. Hollmann, M. F. Stevens. [CrossRef]

- https://resources.wfsahq.org/atotw/pharmacology-for-regional-anaesthesia/ ( accessed on 23.06.25.).

- https://www.iact-org.org/professionals/thermog-guidelines.html#imaging (accessed on 22.06.25.).

- Skin temperature measured by infrared thermography after ultrasound-guided blockade of the sciatic nerve. Van Haren FG, Kadic L, Driessen JJ. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2013 Oct;57(9):1111-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uniform Distribution of Skin-Temperature Increase After Different Regional-Anesthesia Techniques of the Lower Extremity. Werdehausen R, Braun S, Hermanns H, et alRegional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine 2007;32:73-78.

- Basic pharmacology of local anaesthetics. A. Taylor and G. McLeod. [CrossRef]

- Comparison of local anesthetics for digital nerve blocks: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. Vinycomb TI, Sahhar LJ. 2014 Apr;39(4):744-751.e5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A double-blind comparison of ropivacaine, bupivacaine, and mepivacaine during sciatic and femoral nerve blockade. Fanelli G, Casati A, Beccaria P, Aldegheri G, Berti M, Tarantino F, Torri G. Anesth Analg. 1998 Sep;87(3):597-600. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comparison of the onset time between 0.375% ropivacaine and 0.25% levobupivacaine for ultrasound-guided infraclavicular brachial plexus block: a randomized-controlled trial. Kim HJ, Lee S, Chin KJ, Kim JS, Kim H, Ro YJ, Koh WU. Sci Rep. 2021 Feb 25;11(1):4703. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- A comparison of the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of bupivacaine, ropivacaine (with epinephrine) and their equal volume mixtures with lidocaine used for femoral and sciatic nerve blocks: a double-blind randomized study. Cuvillon P, Nouvellon E, Ripart J, Boyer JC, Dehour L, Mahamat A, L'hermite J, Boisson C, Vialles N, Lefrant JY, de La Coussaye JE. Anesth Analg. 2009 Feb;108(2):641-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onset times and duration of analgesic effect of various concentrations of local anesthetic solutions in standardized volume used for brachial plexus blocks. Almasi R, Rezman B, Kriszta Z, Patczai B, Wiegand N, Bogar L. Heliyon. 2020 Sep 2;6(9):e04718. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thermal Imaging to Predict Failed Supraclavicular Brachial Plexus Block: A Prospective Observational Study. Gamal M, Hasanin A, Adly N, Mostafa M, Yonis AM, Rady A, Abdallah NM, Ibrahim M, Elsayad M. Local Reg Anesth. 2023;16:71-80. [CrossRef]

- Ultrasound-guided lateral infraclavicular block evaluated by infrared thermography and distal skin temperature. Asghar S, Lundstrøm LH, Bjerregaard LS, Lange KH.Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2014 Aug;58(7):867-74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detecting bone lesions in the emergency room with medical infrared thermography. Der Strasse, W.a., Campos, D.P., Mendonça, C.J.A. et al. BioMed Eng OnLine 21, 35 (2022). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).