1. Introduction

The importance of the avoidance of hypothermia in patients with burn injuries is well documented. The International Society for Burn Injuries (ISBI) recommends the avoidance of hypothermia, with this being defined as a core temperature of <36

°C [

1]. Local guidelines at the Regional Burns Centre at University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom, advocate avoiding hypothermia per the ISBI guidelines. Additionally, they recommend the maintenance of a core-peripheral temperature gap of ≤ 2

°C in the initial 48 hours following a severe burn injury, based on local experts' consensus. To our knowledge, the use of core-peripheral temperature gradients as a predictor of prognosis in critically ill patients with major burn injuries has not previously been investigated.

Thermoregulation remains a significant challenge in critically ill burn patients. The early onset of hypothermia is associated with increased mortality and length of stay [

2]. This particular challenge is compounded by varied staff perceptions and practices in monitoring temperature, temperature targets and interventions to achieve these targets. Such variation has been highlighted by recent surveys in North America and the UK [

3,

4]. These surveys identified that although the measurement of core body temperature is standard practice, the measurement of peripheral temperature is much more variable. Of the UK burns centres surveyed, 67% routinely measured core and peripheral temperatures in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) setting. Some respondents measured core and peripheral temperatures together in the initial 48-72 hours following injury but, after this time, measured core temperature in isolation [

3].

A raised core-peripheral temperature gradient is well established as a non-invasive indicator of shock; however, its quantitative value is still controversial. Isben first discovered the relationship between peripheral temperature and cardiac function in the 1960s [

5]. This finding was supported by work by Joly and Weil, who conducted a study on 100 patients with signs of circulatory shock and found a statistically significant correlation between worsening cardiac index and decreased toe temperature [

6]. In recent years, Amson and colleagues conducted a prospective observational study to determine the association between core-to-skin temperature gradient and day 8 mortality in patients with septic shock. Their findings showed that a temperature gradient >7 degrees predicted 8-day mortality, independently of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score. The core-peripheral temperature gradient correlated with other markers of hypoperfusion, including capillary refill time, mottling score and lactate level [

7].

Contrary to these findings, an older study by Woods and colleagues demonstrated no association between temperature gradient and invasive measures of circulating blood volume, including cardiac index, systemic vascular resistance and systemic vascular resistance index [

8]. Many research groups have concluded that although a high core-peripheral temperature gradient may be a helpful indicator of shock, it should only be used as an adjunct to other clinical signs and haemodynamic variables [

9,

10]. When used in isolation, a core-peripheral temperature gradient is not a reliable indicator of hypoperfusion. In keeping with this, a systematic review of studies between 1969 and 2009 showed a lack of consensus on the usefulness of skin temperature as a marker of hypoperfusion; the review concluded that skin temperature is not a reliable indicator of hypoperfusion when used in isolation [

9].

A raised core-peripheral temperature differential is typical in the initial hours following a major burn injury [

10]. The raised gap represents the body's attempts to maintain core temperature when faced with an insult to the normal physiological thermoregulatory mechanisms, and burns shock contributed to by hypovolaemia, cardiac depression and increased peripheral vascular resistance. The core-peripheral gradient has been used as a non-invasive marker of hypovolaemia and a guide for fluid resuscitation in adults [

11] and paediatric burn patients [

12]. Unlike other markers of hypoperfusion, including raised base deficit [

13], raised lactate [

14] and reduced urine output [

15], the significance of core-peripheral temperature gradients as a predictor of prognosis to our knowledge has not been investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aim of the Study

The difference (the gap) between the core and peripheral temperature is perceived as an integral part of patient temperature management decision-making in many critical conditions. However, the timing and determinants of the gap in severe burn injuries are poorly understood. Therefore, we set up to explore the timing, magnitude, and prognostic factors of the core-peripheral temperature gap in those patients.

2.2. Methodology

Data was collected from 116 patients admitted with severe burns to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) at Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust between 2016 and 2022.

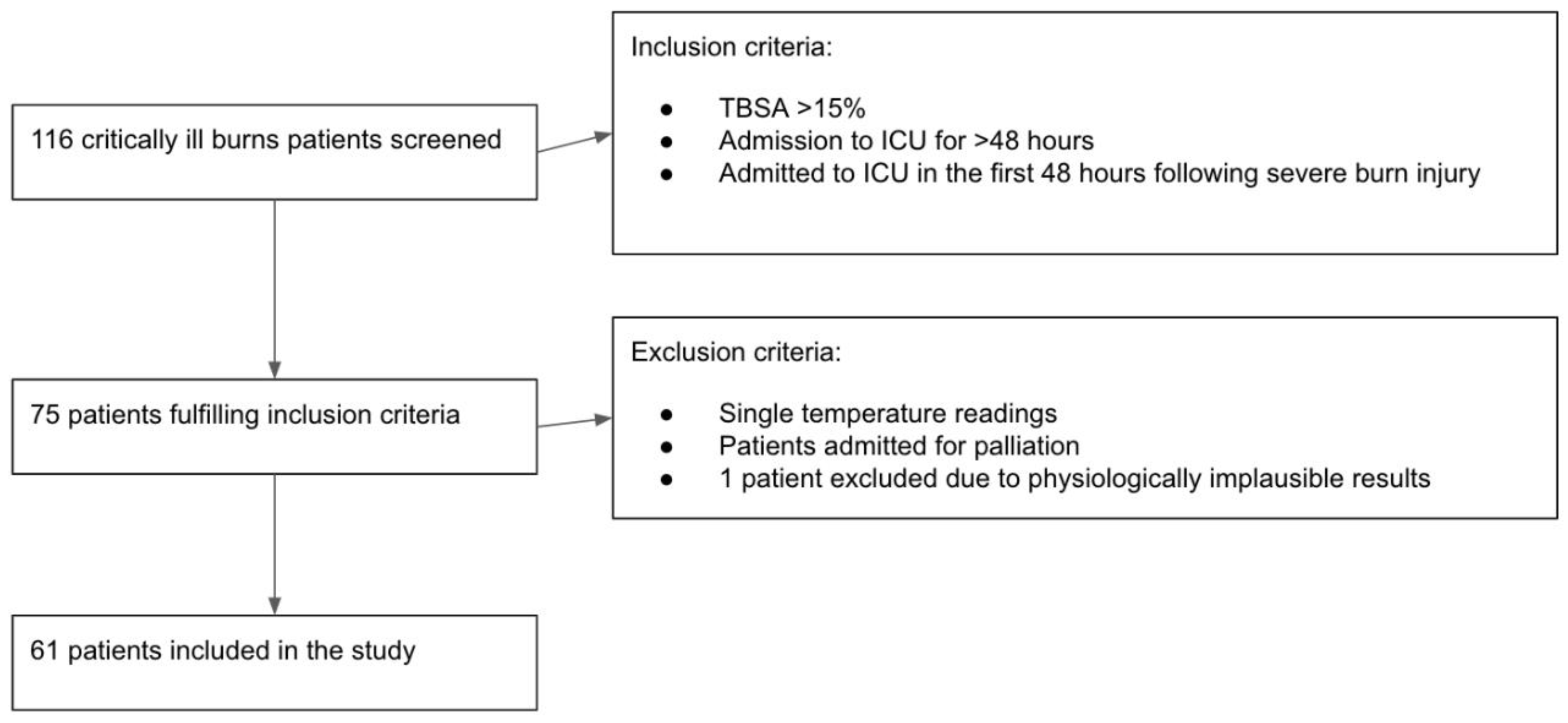

Patients who had sustained a total body surface area (TBSA) burn injury of greater than 15% and were admitted to the ICU for at least 48 hours were included in the analysis. Patients admitted to the ICU for palliation, or those who did not have concurrent core and peripheral temperature measurement recordings were excluded. One patient's observations were further excluded due to the physiologically implausible results, attributed to the technical error in the measurement. Sixty-one patients met these criteria, and their data recorded on the hospital's electronic system (PICS – Prescribing Information and Communication System, Birmingham, United Kingdom) were retrospectively analysed (

Figure 1).

The study was reviewed and approved through the Clinical Audit Registration System (University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, registration number CARMS-14835, registered on 20/11/2018).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Hypothermia was defined at baseline as a core temperature of <36°C. Target core temperature was defined as temperature between 37.5°C and 39.5°C. Continuous variables were categorised as elderly patients (>65 years), high TSBA (>50), and high Baux (>100) and were assessed and recorded within 24 hours after admission to ICU. In the first 24 hours, inhalation injury was assessed via direct bronchoscopy. Core temperature was measured via an indwelled bladder catheter probe. The peripheral temperature was measured using a tympanic thermometer. The external transfer was an emergency or urgent transfer from a peripheral hospital to the burns centre for the escalation of care.

Data collected included patient sex, age, presence or absence of inhalational injury, TBSA of injury, revised Baux score, hourly core temperatures, and peripheral temperatures during the first 48 hours of ICU admission.

Descriptive statistics were presented using means and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and count and percent (%) for categorical variables. The association between baseline clinical and demographic characteristics and core-peripheral temperature gap above >2°C on admission to ICU and at 48h and with in-ICU mortality was assessed using univariable logistic regression. Statistical significance was assumed at the 0.05 level. All analyses were conducted with Stata 17.0 or 18.5 (StataCorp LLC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Cohort

Across the six-year period, a total of 116 patients were admitted to the ICU burns service. Seventy-five patients met the inclusion criteria, and 14 were excluded per pre-defined exclusion criteria, leaving 61 patients to be studied. The selection process details are presented in section 2.2 Methodology (

Figure 1). The baseline characteristics of the studied patients are presented in

Table 1.

3.2. Temperature Values in the Initial 48 Hours

Hourly core and peripheral temperature readings were collected for each patient in the ICU during the first 48 hours of admission (resuscitation period). On average, 35 (SD ±9.9) observations were made for each patient during the first 48 hours, with patients being under observation on average for 41.9 (±9.7) hours. Some data were missing due to the patient being outside the ICU for operative or diagnostic procedures. The average core body temperature in the cohort increased from 36.6°C (±1.4) at baseline to 37.7°C (±0.7) at 48 hours. The mean core-peripheral temperature gap at baseline was 1.4°C (±1.7) and reached 3.6°C (±1.6) at the end of 48 hours. This change in both parameters showed a moderate positive correlation between the core temperature and the core-peripheral temperature gap at 48 hours (r=0.5, p<0.001). 18 patients (29.5%) were hypothermic (<36°C), and 19 patients (31.1%) had a core-peripheral temperature gap of >2 °C at admission to the ICU. Those numbers were reduced to 2 patients remaining hypothermic (3.3%) and 12 patients having a core-peripheral temperature gap of >2° C at the end of the 48-hour resuscitation period. (

Table 2,

Table 3).

3.3. Predictors of core-peripheral temperature gap at the beginning and the end of the resuscitation period

3.3.1. Core peripheral gap at the admission to ICU

Further statistical analysis was performed to analyse the association between the patient clinical and demographic characteristics at admission to the ICU and the core-peripheral gap (

Table 4). None of the characteristics evaluated at the admission to the ICU significantly increased the risk of a core-peripheral gap above 2° C.

3.3.2. Core Peripheral Gap at 48 Hours

A similar analysis was performed at 48 hours of patient admission to the ICU to identify variables increasing the odds of the core-peripheral gap being above 2°C at the end of the resuscitation period (

Table 5). Higher core temperature at 48h was significantly associated with the risk of a core-peripheral temperature gap above 2°C. No other variables were associated with a significant risk of the elevated gap beyond 2° C.

3.3.3. In-ICU mortality and core-peripheral gap

Further analysis was performed to assess the impact of the different patient characteristics on patients' in-ICU mortality (

Table 6). There were no deaths among patients transferred from external hospitals. Two variables showed significant reductions in the odds of in-ICU mortality: a target core temperature at the end of the resuscitation period and a core-peripheral gap > 2°C at the end of the same period. Both variables, as mentioned before, moderately correlated with each other.

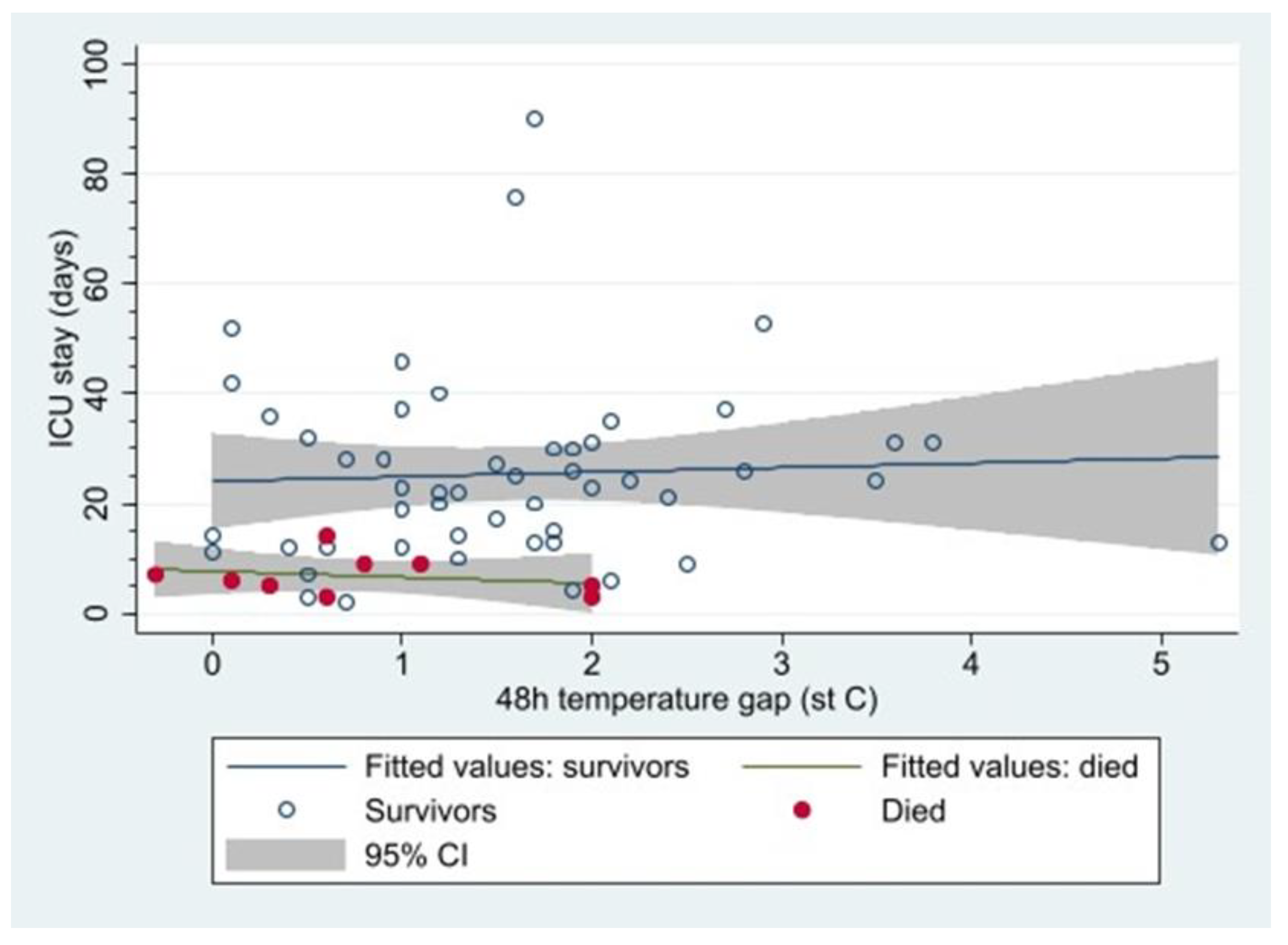

Nine patients died whilst in ICU; all of them had core peripheral gap <2°C at 48h. It is worth noting the survivors had a higher mean 48-hour gap (1.6 [95%CI: 1.3 to 1.9] vs. non-survivors 0.8 [0.2 to 1.4]; p = 0.04) (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

There is limited literature on the value of the core-peripheral temperature gap in managing major burns. Therefore, different guidelines discussing the gap have been based on expert opinion and evidence for the core-peripheral temperature gap in other conditions, such as septic shock. The institutional guidelines at the burns centre where this study was conducted advocate a core-peripheral temperature gap of ≤2°C and a target body temperature between 37.5C and 39.5C during admission following a severe burn injury. The guidelines assumed that a core-peripheral temperature gap above two degrees in the first 48 hours would be associated with a higher mortality rate. This was not reflected in the data from our study.

The cohort of patients who survived was found to have a higher core-peripheral temperature gap at 48 hours than those who died. Furthermore, all patients in the cohort who died after 48 hours had a core peripheral temperature gap of <2°C (

Figure 2). These findings differed from the initial expert consensus and local guidelines. The reason for such a discrepancy may be multifactorial.

Previous studies looking into the core-peripheral temperature gap and its use as a prognostic factor in critically ill patients have looked at patients with pathologies other than burn injuries. The prospective study by Amson and colleagues evaluating the value of core-skin temperature gradient as a marker of early mortality in patients with septic shock had a very different result; they found that a gap of >7°C was predictive of early mortality [

7]. The differing pathophysiology of septic shock and severe burn injuries means that although there is evidence to show that a raised core-peripheral temperature gap is indicative of a poorer outcome in patients with septic shock, it is not generalisable to patients with severe burn injuries. Ambient temperature manipulation of the patient's environment to avoid hypothermia forms an essential part of managing critically ill patients with burn injuries. It is unclear what value measuring the core-peripheral temperature gap has in an environment where the patient's temperature is actively manipulated.

Our study showed a highly varied distribution of 48-hour temperature gaps in patients who survived (

Figure 2). Additionally, our study had a relatively small cohort of patients since data from our unit alone were analysed. Given our study's limitations, one cannot definitively conclude from our data alone that a lower 48-hour temperature gap is associated with increased mortality in patients with major burn injury. Our data show that the factor reducing mortality is the avoidance of hypothermia and, even more importantly, achieving higher core temperature during the resuscitation phase. Therefore, one may hypothesise that the core-peripheral gap in patients, in whom core temperature is actively manipulated, simply reflects the ability of patients to respond to therapeutic interventions. Our results suggest that the utmost priority is in achieving an adequate target core temperature in the initial resuscitation phase rather than placing undue importance on the core-peripheral gap when making clinical therapeutic decisions.

Further studies, in the form of a multicentre trial, would provide a significantly larger cohort of patients. This would allow for the stratification of the core-peripheral temperature gap and further determination of the impact of the core-peripheral gap value on outcomes in critically ill patients with severe burn injuries.

5. Conclusions

A core-peripheral gap above 2°C is not indicative of poorer outcomes in adult patients with severe burns during the resuscitation period. To the contrary, in our cohort, a temperature gap below 2°C as a single independent variable was associated with higher mortality. The mortality in those patients was also increased by hypothermia (temperature below 36°C) at admission and at the end of the study period. Achieving a higher core body temperature at the end of the resuscitation period had an even more pronounced, albeit opposite effect, significantly reducing mortality.

Our findings support previous studies suggesting that avoiding hypothermia and achieving a higher core temperature are associated with reduced mortality. However, it also challenges the previous expert consensus that a lower core-peripheral gap indicates poorer outcomes. Further research with a larger cohort of patients is required to identify whether a higher core-peripheral temperature gap predicts patient outcomes in critically ill patients with severe burns.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: NK, JD, RM, EC, BT and TT; methodology: RM, EC, BT and TT, validation RM, EC, BT and TT; formal analysis: BT.; investigation: NK, JD, RM, EC and TT; resources: RM, EC and TT; data curation: RM, EC and TT; writing—original draft preparation: NK, JD and TT; writing—review and editing: NK, JD, RM, EC, BT and TT; visualisation: NK and JD.; supervision: TT; project administration: RM, EC and TT. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Clinical Audit Registration System (University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, registration number CARMS-14835, registered on 20/11/2018).

Informed Consent Statement

"Individual prospective patient consent was not applicable, as the study design is a retrospective analysis (an audit) of routinely collected data, registered and performed within the institutional framework.".

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available. per request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahuja, RB. ISBI practice guidelines for burn care: Editorial. Burns 2016, 42, 951–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler B, Kenngott T, Fischer S, Hundeshagen G, Hartmann B, Horter J, Münzberg M, Kneser U, Hirche C. Early hypothermia as risk factor in severely burned patients: A retrospective outcome study. Burns. 2019, 45, 1895–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullhi R, Ewington I, Chipp E, Torlinski T. A descriptive survey of operating theatre and intensive care unit temperature management of burn patients in the United Kingdom. Int J Burns Trauma. 2021, 11, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pruskowski KA, Rizzo JA, Shields BA, Chan RK, Driscoll IR, Rowan MP, Chung KK. A Survey of Temperature Management Practices Among Burn Centers in North America. J Burn Care Res. 2018, 39, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isben, B. Treatment of Shock with Vasodilators Measuring Skin Temperature on the Big Toe: Ten Years' Experience in 150 Cases. Diseases of the Chest. 1967, 52, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly HR, Weil MH. Temperature of the great toe as an indication of the severity of shock. Circulation. 1969, 39, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amson H, Vacheron CH, Thiolliere F, Piriou V, Magnin M, Allaouchiche B. Core-to-skin temperature gradient measured by thermography predicts day-8 mortality in septic shock: A prospective observational study. J Crit Care. 2020, 60, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods IF, et al. Danger of using core/peripehral temperature gradient as a guide to therapy in shock. Critical Care Medicine. 1987, 15, 850–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeong Brigitte WF, Childs C. A systematic review on the role of extremity skin temperature as a non-invasive marker for hypoperfusion in critically ill adults in the intensive care setting. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2012, 10, 1504–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renshaw A, Childs C. The significance of peripheral skin temperature measurement during the acute phase of burn injury: an illustrative case report. Burns. 2000, 26, 750–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, B.; Brock, L.; Aynsley-Green, A. Observations on central and peripheral temperatures in the understanding and management of shock. British Journal of Surgery 1969, 56, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aynsley-Green, A.; Pickering, D. Use of central and peripheral temperature measurements in care of the critically ill child. Archives of Disease in Childhood 1974, 49, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snell JA, Loh NH, Mahambrey T, Shokrollahi K. Clinical review: the critical care management of the burn patient. Crit Care. 2013, 17, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamolz LP, Andel H, Schramm W, Meissl G, Herndon DN, Frey M. Lactate: early predictor of morbidity and mortality in patients with severe burns. Burns. 2005, 31, 986–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeng JC, Lee K, Jablonski K, Jordan MH: Serum lactate and base deficit suggest inadequate resuscitation of patients with burns injuries: application of point-of-care laboratory instrument. J Burn Care Rehabil 1997, 18, 402–405.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).