Submitted:

15 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

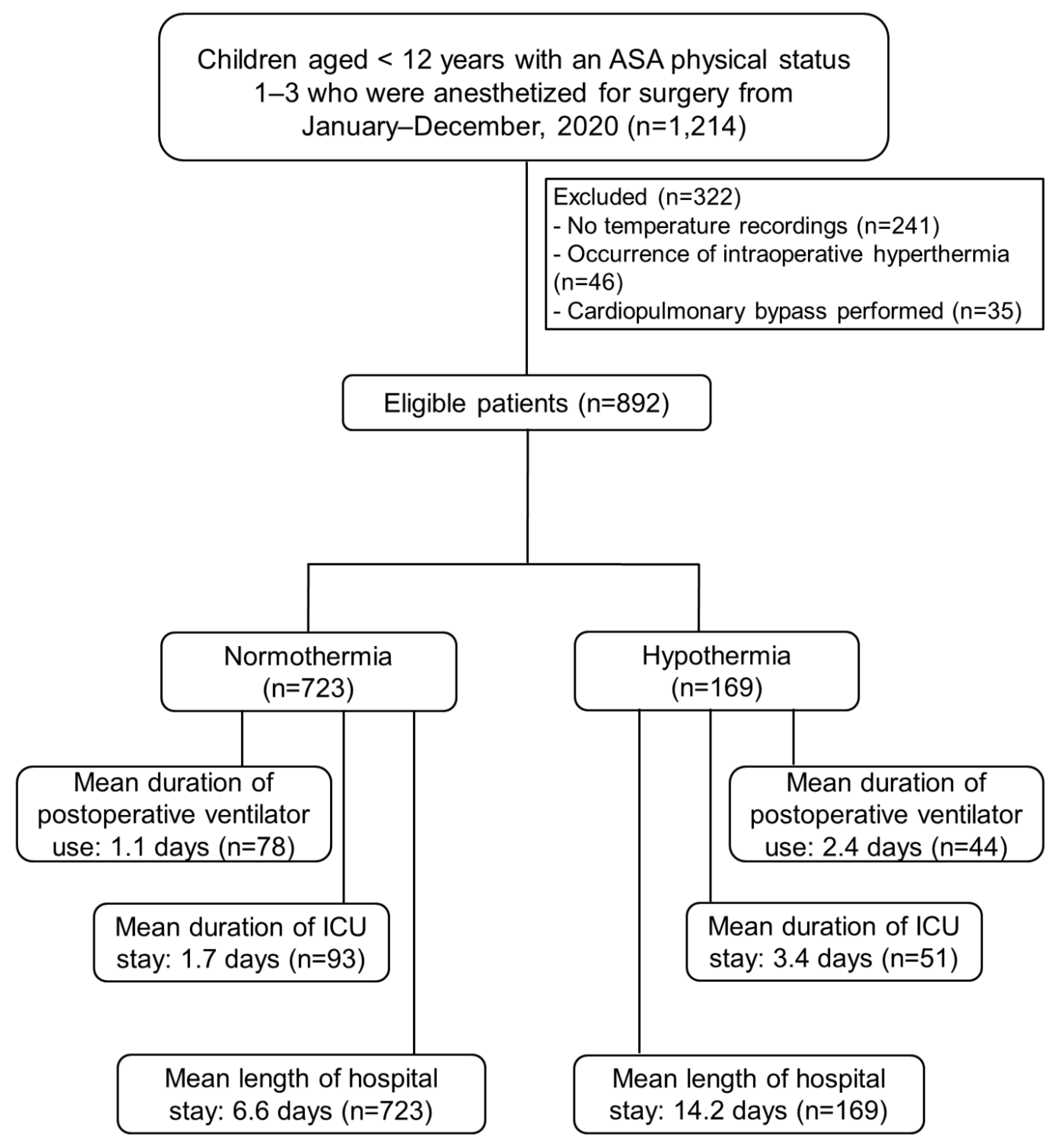

Background/Objectives: Few studies have investigated the perioperative adverse events following intraoperative hypothermia in pediatric patients with preserved functional capacity. We aimed to assess associations between intraoperative hypothermia and adverse outcomes in pediatric patients undergoing anesthesia. Methods: This retrospective cohort study included children under 12 years of age who underwent anesthesia in 2020 at Songklanagarind Hospital, Thailand. Intraoperative hypothermia was defined as the occurrence of >1 episode of a core temperature drop to <36 °C during anesthesia. Perioperative data were extracted from the hospital information system and analyzed to identify adverse outcomes. Children with an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status of 4–5 were excluded to ensure only those with preserved functional capacity before surgery were included. Multivariate regression modeling was used to evaluate associations between hypothermia and adverse outcomes after adjusting for potential confounders. Odds ratios (ORs) or beta coefficients (β) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were determined. Results: Among the 892 patients, 169 (19%) experienced intraoperative hypothermia. Intraoperative hypothermia was significantly associated with postoperative ventilator requirements (p<0.001), postoperative intensive care unit (ICU) admission (p<0.001), longer ventilator requirements (p<0.001), and prolonged ICU stays (p<0.001) and hospitalization periods (p<0.001). The multivariate analysis demonstrated that intraoperative hypothermia was only associated with prolonged ICU stays (β 1.2 [0.67,1.73] days) and hospitalization periods (β 1.42 [0.78, 1.71] days). Conclusions: Intraoperative hypothermia was associated with adverse outcomes in children with preserved functional capacity undergoing anesthesia, suggesting hospital policies should be modified to ensure vigorous perioperative temperature management to mitigate these outcomes.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

2.2. Standard Operating Procedures for Pediatric Anesthesia

2.3. Main Exposure

2.4. Potential Confounding Variables

2.5. Definition of Variables

2.6. Outcomes

2.7. Sample Size Determination

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Hypothermia-Related Outcomes

3.3. Univariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of Significant Outcomes Related with Intraoperative Hypothermia

3.4. Univariate and Multivariate Negative Binomial Regression Analysis of Significant Outcomes Related with Intraoperative Hypothermia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AR ASA BSA CI GA ICU IQR OR PACU |

Allergic rhinitis American Society of Anesthesiologists Body surface area Confidence interval General anesthesia Intensive care unit Interquartile range Odds ratio Post-anesthesia care unit |

References

- Burns, S.M.; Piotrowski, K.; Caraffa, G.; Wojnakowski, M. Incidence of postoperative hypothermia and the relationship to clinical variables. J Perianesth Nurs 2010, 25, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, S.; Aksoy, S.M.; But, A. The incidence of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia in patients undergoing general anesthesia and an examination of risk factors. Int J Clin Pract 2021, 75, e14103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, B.; Christensen, R.; Voepel-Lewis, T. Perioperative hypothermia in the pediatric population: Prevalence, risk factors and outcomes. J Anesthe Clinic Res 2010, 1, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessler, D.I. Perioperative thermoregulation and heat balance. Lancet 2016, 387, 2655–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galante, D. Intraoperative hypothermia. Relation between general and regional anesthesia, upper- and lower-body warming: what strategies in pediatric anesthesia? Paediatr Anaesth 2007, 17, 821–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boniol, M.; Verriest, J.P.; Pedeux, R.; Doré, J.F. Proportion of skin surface area of children and young adults from 2 to 18 years old. J Invest Dermatol 2008, 128, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M.; Baumgart, S. Avery’s neonatology: pathophysiology & management of the newborn, 1st ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, USA, 2005; pp. 1–3845. [Google Scholar]

- Brindle, M.E.; McDiarmid, C.; Short, K.; Miller, K.; MacRobie, A.; Lam, J.Y.K.; et al. Consensus guidelines for perioperative care in neonatal intestinal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. World J Surg 2020, 44, 2482–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Lei, Y.; Xu, S.; Si, Y.; Li, S.; Xia, Z.; et al. Intraoperative hypothermia and its clinical outcomes in patients undergoing general anesthesia: National study in China. PLoS On. 2017, 12, e0177221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, O.H.; Barclay, K.L. Perioperative hypothermia in patients undergoing major colorectal surgery. ANZ J Surg 2014, 84, 550–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, A.; Sessler, D.I.; Lenhardt, R. Perioperative normothermia to reduce the incidence of surgical-wound infection and shorten hospitalization. Study of Wound Infection and Temperature Group. N Engl J Med 1996, 334, 1209–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Bene, V.E. Clinical methods: The history, physical, and laboratory examinations. In Temperature, 1st ed.; Walker, H.K., Hall, W.D., Hurst, J.W., Eds.; Butterworths: Oxford, UK, 1990; pp. 990–993. [Google Scholar]

- El Edelbi, R.; Lindemalm, S.; Eksborg, S. Estimation of body surface area in various childhood ages--validation of the Mosteller formula. Acta Paediatr 2012, 101, 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongsayreepong, S.; Chaibundit, C.; Chadpaibool, J.; Komoltri, C.; Suraseranivongse, S.; Suwannanonda, P.; et al. Predictor of core hypothermia and the surgical intensive care unit. Anesth Analg 2003, 96, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngamjarus, C.; Chongsuvivatwong, V.; McNeil, E. n4Studies: Sample size calculation for an epidemiological study on a smart device. Siriraj Med J 2016, 68, 160–170. [Google Scholar]

- Zeileis, A.; Kleiber, C.; Jackman, S. Regression models for count data in R. J Stat Softw 2008, 27, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, J.; Shu, Q. Study of risk factors for intraoperative hypothermia during pediatric burn surgery. World J Pediatr Surg. 2021, 4, e000141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Le, Z.; Chu, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Fan, J.; et al. Risk factors and outcomes of intraoperative hypothermia in neonatal and infant patients undergoing general anesthesia and surgery. Front Pediatr 2023, 11, 1113627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamura, M.; Saito, W.; Miyagi, M.; Shirasawa, E.; Imura, T.; Nakazawa, T.; et al. Incidence of unintentional intraoperative hypothermia in pediatric scoliosis surgery and associated preoperative risk factors. Spine Surg Relat Res 2020, 5, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Wan, S.Y.K.; Tay, C.L.; Tan, Z.H.; Wong, I.; Chua, M.; et al. Perioperative temperature management in children: What matters? Pediatr Qual Saf 2020, 5, e350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deekiatphaiboon, C.; Oofuvong, M.; Karnjanawanichkul, O.; Siripruekpong, S.; Bussadee, P. Ultrasonography measurement of glottic transverse diameter and subglottic diameter to predict endotracheal tube size in children: a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 15215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongyingsinn, M.; Pookprayoon, V. Incidence and associated factors of perioperative hypothermia in adult patients at a university-based, tertiary care hospital in Thailand. BMC Anesthesiol 2023, 23, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.M.; Beattie, C.; Christopherson, R.; Norris, E.J.; Perler, B.A.; Williams, G.M.; et al. Unintentional hypothermia is associated with postoperative myocardial ischemia. The Perioperative Ischemia Randomized Anesthesia Trial Study Group. Anesthesiology 1993, 78, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, S.M.; Fleisher, L.A.; Breslow, M.J.; Higgins, M.S.; Olson, K.F.; Kelly, S.; et al. Perioperative maintenance of normothermia reduces the incidence of morbid cardiac events. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 1997, 277, 1127–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Fan, J.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y. Risk factors for intraoperative hypothermia in infants during general anesthesia: A retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2023, 102, e34935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görges, M.; Afshar, K.; West, N.; Pi, S.; Bedford, J.; Whyte, S.D. Integrating intraoperative physiology data into outcome analysis for the ACS Pediatric National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Paediatr Anaesth 2019, 29, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oofuvong, M.; Geater, A.F.; Chongsuvivatwong, V.; Chanchayanon, T.; Sriyanaluk, B.; Saefung, B.; et al. Excess costs and length of hospital stay attributable to perioperative respiratory events in children. Anesth Analg 2015, 120, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oofuvong, M.; Tanasansuttiporn, J.; Wasinwong, W.; Chittithavorn, V.; Duangpakdee, P.; Jarutach, J.; et al. Predictors of death after receiving a modified Blalock-Taussig shunt in cyanotic heart children: A competing risk analysis. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0245754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuonen, A.; Riva, T.; Erdoes, G. Bradycardia in a newborn with accidental severe hypothermia: treat or don’t touch? A case report. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2021, 29, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.T.; Ting, P.C.; Chang, W.Y.; Yang, M.W.; Chang, C.J.; Chou, A.H. Predictive risk index and prognosis of postoperative reintubation after planned extubation during general anesthesia: a single-center retrospective case-controlled study in Taiwan from 2005 to 2009. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan 2013, 51, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, S.; Mascha, E.; Na, J.; Sessler, D.I. The effects of mild perioperative hypothermia on blood loss and transfusion requirement. Anesthesiology 2008, 108, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmied, H.; Kurz, A.; Sessler, D.I.; Kozek, S.; Reiter, A. Mild hypothermia increases blood loss and transfusion requirements during total hip arthroplasty. Lancet 1996, 347, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.B. The environment and disease: Association or causation? Proc R Soc Med 1965, 58, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ralph, N.; Gow, J.; Conway, A.; Duff, J.; Edward, K.; Alexander, K.; et al. Costs of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia in Australia: A cost-of-illness study. Collegian 2020, 27, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Intraoperative hypothermia | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 723) | Yes (n = 169) | ||

| Demographics | |||

| Male sex | 468 (64.7%) | 108 (63.9%) | 0.8 |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 4.6 [1.8, 7.7] | 3.9 [1.2, 8.1] | 0.12 |

| Age (years) >1 / <1 | 619 (85.6%)/104 (14.4%) | 129 (76.3%)/40 (23.7%) | 0.003* |

| Body weight (kg), median (IQR) | 15.6 [10.2, 22.8] | 14.6 [9.0, 23.0] | 0.06 |

| Body height (cm), median (IQR) | 102.0 [80.3, 122.0] | 99.0 [72.0, 122.0] | 0.12 |

| Percentile weight >P3/<P3 | 578 (79.9%)/145 (20.1%) | 126 (74.6%)/43 (25.4%) | 0.12 |

| BSA (m2), median (IQR) | 0.7 [0.5, 0.9] | 0.6 [0.4, 0.9] | 0.05 |

| Weight-to-BSA ratio, median (IQR) | 23.5 [21.1, 26.6] | 23.2 [20.4, 25.6] | 0.087 |

| Underlying disease | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | 123 (17.0%) | 26 (15.4%) | 0.6 |

| Respiratory disease | 129 (17.8%) | 32 (18.9%) | 0.7 |

| Neurologic disease | 60 (8.3%) | 30 (17.8%) | <0.001* |

| Hematologic disease | 220 (30.4%) | 55 (32.5%) | 0.6 |

| Endocrine disease | 46 (6.4%) | 9 (5.3%) | 0.6 |

| Elective/emergency surgery | 628 (86.9%)/95 (13.1%) | 151 (89.3%)/18 (10.7%) | 0.4 |

|

Preoperative body temperature (°C), median (IQR) |

36.8 [36.6, 37.0] | 36.8 [36.6, 37.0] | 0.5 |

| Route of temperature monitoring | 0.11 | ||

| Rectal | 69 (9.6%) | 14 (8.4%) | |

| Nasopharyngeal | 160 (22.2%) | 48 (28.7%) | |

| Esophageal | 250 (34.7%) | 54 (32.3%) | |

| Skin | 237 (32.9%) | 47 (28.1%) | |

| Axillary | 5 (0.7%) | 4 (2.4%) | |

| Unknown | 2 (0.3%) | 2 (1.2%) | |

| Magnitude of surgery | <0.001* | ||

| Major | 50 (6.9%) | 30 (17.8%) | |

| Intermediate | 510 (70.5%) | 121 (71.6%) | |

| Minor | 163 (22.5%) | 18 (10.7%) | |

| Site of surgery | 0.001* | ||

| Superficial | 116 (16.0%) | 19 (11.2%) | |

| Eye, ear/nose/throat | 318 (44.0%) | 50 (29.6%) | |

| Abdomen | 125 (17.3%) | 38 (22.5%) | |

| Extremities | 133 (18.4%) | 45 (26.6%) | |

| Intracranial | 17 (2.4%) | 12 (7.1%) | |

| Intrathoracic | 14 (1.9%) | 5 (3.0%) | |

| Variable | Intraoperative hypothermia | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 723) | Yes (n = 169) | ||

| ASA physical status | 0.005** | ||

| 1 | 158 (21.9%) | 39 (23.1%) | |

| 2 | 377 (52.1%) | 67 (39.6%) | |

| 3 | 188 (26.0%) | 63 (37.3%) | |

| Type of GA | |||

| GA with caudal/epidural block | 80 (11.1%) | 27 (16.0%) | 0.077 |

| GA with peripheral nerve block | 52 (7.2%) | 18 (10.7%) | 0.13 |

| Type of airway management | 0.2 | ||

| Endotracheal tube | 622 (86.0%) | 139 (82.2%) | |

| Laryngeal mask airway | 101 (14.0%) | 30 (17.8%) | |

| Anesthesia time (min), median (IQR) | 105.0 [80.0, 150.0] | 145.0 [100.0, 190.0] | <0.001* |

| Operation time (min), median (IQR) | 70.0 [50.0, 110.0] | 100.0 [60.0, 140.0] | 0.001* |

| Neuromuscular blocking agent use | 0.023*** | ||

| None | 127 (17.6%) | 34 (20.1%) | |

| Cisatracurium | 595 (82.3%) | 132 (78.1%) | |

| Rocuronium | 1 (0.1%) | 3 (1.8%) | |

| Volatile anesthetic use | 0.019*** | ||

| None (intravenous anesthetics only) | 21 (2.9%) | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Sevoflurane | 676 (93.5%) | 167 (98.8%) | |

| Desflurane | 26 (3.6%) | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Active warming | 709 (98.1%) | 163 (96.4%) | 0.2 |

| Fluid use | |||

| Crystalloid (mL), median (IQR) | 172.0 [100.0, 300.0] | 163.0 [85.0, 350.0] | 0.8 |

| Colloid | 7 (1.0%) | 2 (1.2%) | 0.7 |

| Characteristic | Hypothermia group |

|---|---|

| Nadir temperature (°C) | |

| Mean (SD) | 35.5 (0.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 35.6 [35.3, 35.7] |

| Duration of hypothermia (min) | |

| Mean (SD) | 65.0 (48.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 60.0 (30.0, 90.0) |

| Severity of hypothermia | |

| Mild (34 °C to <36 °C) | 169 (100%) |

| Moderate (32 °C to <34 °C) | 0 |

| Variable |

Intraoperative hypothermia | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 723) | Yes (n = 169) | ||

| Blood loss (mL), median (IQR) | 5.0 [1.0, 15.0] | 5.0 [2.0, 20.0] | 0.011* |

| Blood transfusion | 34 (4.7%) | 25 (14.8%) | <0.001** |

| Intraoperative bradycardia | 24 (3.3%) | 5 (3.0%) | 0.5 |

| Length of PACU stay (min), median (IQR) | 45.0 [35.00, 60.0] | 45.0 [30.00, 60.0] | 0.12 |

| Shivering | 6 (0.8%) | 2 (1.2%) | 0.7 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 8 (1.1%) | 2 (1.2%) | 0.9 |

|

Postoperative oxygen requirements |

38 (5.3%) | 5 (3.0%) | 0.29 |

| Oxygen cannula | 7 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.4 |

| Non-rebreather mask | 2 (0.3%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0.2 |

| Mask/oxygen flow | 28 (3.9%) | 3 (1.8%) | 0.3 |

| Oxygen box | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| High-frequency nasal cannula | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0.5 |

|

Postoperative ventilator requirement |

78 (10.8%) | 44 (26.0%) | <0.001** |

| Duration of oxygen and ventilator requirement (days) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.1 (6.9) | 2.4 (7.4) | <0.001+ |

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | 0.0 [0.0, 1.0] | <0.001* |

| Postoperative ICU admission | 93 (12.9%) | 51 (30.2%) | <0.001** |

| Duration of ICU admission (days) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.7 (8.6) | 3.4 (10.1) | <0.001+ |

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | 0.0 [0.0, 1.0] | <0.001* |

| Duration of hospitalization (days) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 6.6 (14.1) | 14.2 (24.5) | <0.001+ |

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 [1.0, 5.0] | 4.0 [2.0, 13.0] | <0.001* |

| Reintubation | 1 (0.1%) | 2 (1.2%) | 0.094 |

|

Variable |

Postoperative ventilator requirement | Postoperative ICU admission | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Hypothermia | 1.87 (0.77, 4.55) | 0.167 | 1.93 (0.97, 3.87) | 0.063 |

| Respiratory tract infection/ AR/asthma | 7.17 (2.88, 17.88) | < 0.001 | 3.56 (1.78, 7.09) | < 0.001 |

| Underlying neurologic disease | 4.48 (1.83, 10.96) | 0.001 | ||

| ASA physical status = 3 (Ref: <2) | 21.86 (7.16, 66.79) | < 0.001 | 11.37 (5.72, 22.61) | < 0.001 |

| Body weight (kg) | 0.81 (0.78, 0.84) | < 0.001 | ||

| Body height (cm) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) | < 0.001 | ||

| Percentile weight <P3 (Ref: >P3) | 0.31 (0.11, 0.85) | 0.023 | ||

| Weight-to-BSA ratio <16 (Ref: >16) | 204.06 (40.51, 1027.91) | < 0.001 | 17.63 (5.38, 57.76) | < 0.001 |

| Major surgery | 5.88 (2.15, 16.09) | < 0.001 | ||

| Anesthesia time (min) | 1.0039 (0.9998, 1.008) | 0.06 | 1.0048 (1.001, 1.0086) | 0.012 |

| Emergency surgery | 4.08 (1.53, 10.83) | 0.005 | ||

| Site of surgery (Ref: superficial) | 0.003* | |||

| Eye, ear/nose/throat | 0.76 (0.3, 1.91) | 0.558 | ||

| Abdomen | 1.09 (0.42, 2.82) | 0.853 | ||

| Extremities | 1.04 (0.36, 2.99) | 0.944 | ||

| Intracranial | 6.3 (1.9, 20.93) | 0.003 | ||

| Intrathoracic | 8.37 (1.39, 50.49) | 0.02 | ||

|

Variable |

Duration of ventilator requirement (days) | Duration of ICU stay (days) | Duration of hospitalization period (days) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted β ((95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted β (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted β (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Hypothermia | 0.22 (-0.31, 0.74) | 1 | 1.20 (0.67, 1.73) | 0.001 | 1.42 (0.78, 1.71) | 0.001 |

| Age (years) | 0.08 (-0.05,0.22) | 1 | 0.22 (0.09,0.36) | 0.001 | ||

| Respiratory tract infection/AR/asthma | 0.91 (0.42, 1.39) | 0.001 | 1.15 (0.62, 1.69) | 0.001 | ||

| Congenital heart disease | -0.50 (-1.088, 0.09) | 0.1 | 0.81 (0.63, 1.04) | 0.01 | ||

| Underlying neurologic disease | 1.87 (1.17, 2.59) | 0.001 | 1.48 (0.86, 2.10) | 0.001 | ||

| Underlying hematologic disease | 1.83 (1.56,2.14) | 0.001 | ||||

| ASA physical status =3 (Ref: < 2) | 2.63 (2.08, 3.20) | 0.001 | 3.74 (3.19, 4.31) | 0.001 | 2.58 (2.09, 3.18) | 0.001 |

| Percentile weight < P3 (Ref: > P3) | 0.31 (-0.26, 0.88) | 1 | 1.34 (1.11, 1.61) | 0.01 | ||

| Body height (cm) | -0.03 (-0.05, -0.02) | 0.001 | -0.06 (-0.04, -0.01) | 0.001 | ||

| Body weight (kg) | 0.05 (0.02, 0.08) | 0.01 | ||||

| Weight-to-BSA ratio < 16 (Ref: >16) | 2.19 (1.37, 3.02) | 0.001 | 1.46 (0.63, 2.28) | 0.001 | ||

| Emergency surgery | 0.58 (0.009, 1.14) | 0.04 | 0.66 (0.05, 1.28) | 0.05 | 1.61 (1.28, 2.01) | 0.001 |

| Anesthesia time (min) | 0.002 (-0.00, 0.004) | 1 | 1.00 (1.001, 1.002) | 0.001 | ||

| Site of surgery (Ref: superficial) | 0.001* | <0.001* | ||||

| Eye, ear/nose/throat | -0.62 (-1.29, 0.044) | 0.1 | 0.64 (0.50, 0.83) | 0.001 | ||

| Abdomen | -1.31 (-2.09,- 0.53) | 0.01 | 1.49 (1.13, 1.95) | 0.01 | ||

| Extremities | -0.80 (-1.61, 0.002) | 0.1 | 1.23 (0.92, 1.63) | 1 | ||

| Intracranial | -1.62 (-2.76,- 0.47) | 0.01 | 1.10 (0.69, 1.75) | 1 | ||

| Intrathoracic | 0.41 (-0.73, 1.55) | 1 | 2.54 (1.49, 4.33) | 0.001 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).