Submitted:

12 September 2025

Posted:

15 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

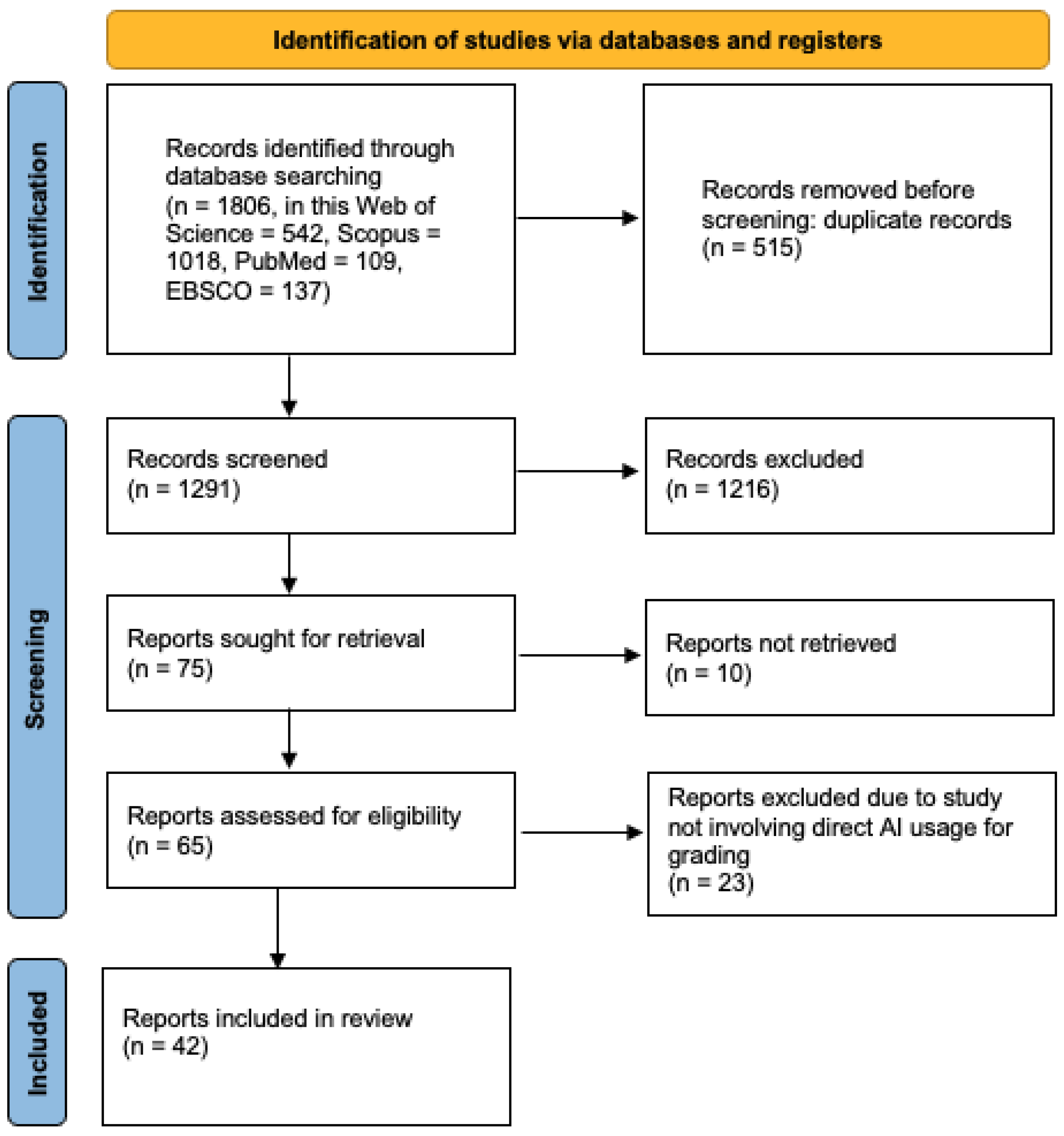

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility criteria and the search

- Focused on students across different educational levels, i.e., both elementary and higher education, as well as specific educational contexts like studies on only medical students or only English as a Foreign Language (EFL) students.

- Involved the use of LLM type of generative AI, both commercially available (like ChatGPT, Gemini, or Claude) as well as open sourced or custom LLMs. The usage of GenAI needed to be within the context of student grading (e.g., automatic scoring, response sheets, or descriptive grades). So, for instance, we were not interested in studies that involved using GenAI solely to provide feedback to students without the grading context.

- Were empirical. Other reviews and purely opinion-based pieces were excluded from our review.

- Were published in peer-review journals and conference proceedings after the official launch of ChatGPT in late 2022.

2.2. Screening and quality assessment

| Category | Search Terms / Filters |

|---|---|

| Inclusion: AI Technologies | “ChatGPT” OR “Claude” OR “Gemini” OR “Copilot” OR “Deepseek” OR “generative AI” OR “generative artificial intelligence” OR “large language model*” OR “LLM*” OR “text-to-text model*” OR “multimodal AI” OR “transformer-based model*” |

| Inclusion: Education Contexts | “adult education” OR “college*” OR “elementary school*” OR “graduate” OR “higher education” OR “high school*” OR “K-12” OR “kindergarten*” OR “middle school*” OR “postgrad*” OR “primary school*” OR “undergrad*” OR “vocational education” |

| Inclusion: Assessment Contexts | “assessment” OR “grading” OR “scoring” OR “feedback” OR “AI grading” OR “automated assessment” OR “automated scoring” OR “automated grading” OR “automated feedback” OR “automatic assessment” OR “automatic scoring” OR “automatic grading” OR “automatic feedback” OR “machine-generated feedback” |

| Exclusion: Study Types | NOT “bibliometrics analysis” OR “literature review” OR “rapid review” OR “scoping review” OR “systematic review” |

| Exclusion: Time Frame | AND PUBYEAR > 2022 |

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the analyzed articles

- Computer science – 7 studies (mainly automatic assessment of programming tasks and code),

- Foreign languages – 7 studies (assessment of essays and written assignments in foreign languages),

- Mathematics – 5 studies (calculation tasks, mathematical reasoning),

- Medicine – 5 studies (exam questions, open-ended tasks in medical education),

- Engineering – 3 studies (engineering projects, open-ended tasks),

- Pedagogy, social sciences, and humanities – single studies (assessment of essays, reflections, creativity).

| Study | Level | Field | LLM type | Task type | Key findings |

| [27] | university or college | medicine | gpt4, gemini 1.0 pro | short answers | GPT-4 assigns significantly lower grades than the teacher, but rarely incorrectly gives maximum scores to incorrect answers (low “false positives”). Gemini 1.0 Pro gives grades similar to those given by teachers—their grades did not differ significantly from human scores. Both GPT-4 and Gemini achieve moderate agreement with teacher assessments, but GPT-4 demonstrates high precision in identifying fully correct answers. |

| [28] | secondary school | foreign language | gpt3.5, gpt4, iFLYTEK, and Baidu Cloud | essay | LLM models (GPT-4, GPT-3.5, iFLYTEK) achieved results very close to human raters in identifying correct and incorrect segments of text. Their accuracy at the T-unit level (syntactic segments) was about 81%, and at the sentence level 71–77%. GPT-4 stood out with the highest precision (fewest false positives), meaning it rarely incorrectly marked incorrect answers as correct. |

| [29] | university or college | math | other | calculation tasks | Even with advanced prompting (zero/few-shot), GPT-3.5 performs noticeably worse than AsRRN. GPT-3.5 improves when reference examples are provided, but it does not reach the effectiveness of the relational model. |

| [30] | university or college | economics | gpt4 | short answers | GPT-4 grades very consistently and reliably: agreement indices (ICC) for content and style scores range from 0.94 to 0.99, indicating nearly “perfect” consistency between repeated ratings on different sets and at different times. |

| [31] | university or college | computer science | gpt3.5 | coding tasks | The model correctly classified 73% of solutions as correct or incorrect. Its precision for correct solutions was 80%, and its specificity in detecting incorrect solutions was as high as 88%. However, recall—the ability to identify all correct solutions—was only 57%. In 89–100% of cases, AI-generated feedback was personalized, addressing the specific student’s code. This was much more detailed than traditional e-assessment systems, which usually rely on simple tests. |

| [32] | primary school | na | gpt3 | other | AI grades were in very high agreement with the ratings of a panel of human experts (r = 0.79–0.91 depending on the task type), meaning that AI can generate scores comparable to subjective human judgments. The model demonstrates high internal consistency of ratings (reliability at H = 0.82–0.89 for different subscales and overall originality), making AI a reliable tool in educational applications. |

| [33] | secondary school | biology | bert | short answers | The alephBERT-based system clearly outperforms classic CNN models in automatic grading of students’ short biology answers, both in overall and detailed assessment (for each category separately). The model showed surprisingly good performance even in “zero-shot” mode—that is, when grading answers to new questions about the same biological concepts it had not seen during training. This means that AI can be used to automatically grade new tasks, as long as they relate to similar concepts/rubrics. |

| [34] | university or college | foreign language | gpt4, gpt3.5 | essay | ChatGPT 4 achieved higher reliability coefficients for holistic assessment (both G-coefficient and Phi-coefficient) than academic teachers evaluating English as a Foreign Language (EFL) essays. ChatGPT 3.5 had lower reliability than the teachers, but was still a supportive tool. In practice, ChatGPT 4 was more consistent and predictable in its scoring than humans. Both ChatGPT 3.5 and 4 generated more and more relevant feedback on language, content, and text organization compared to the teachers. |

| [35] | university or college | mixed | gpt4, gpt3.5 | short answers | GPT-4 performs well in grading short student answers (QWK ≥ 0.6, indicating good agreement with human scores) in 44% of cases in the one-shot setting, significantly better than GPT-3.5 (21%). The best results occur for simple, narrowly defined questions and short answers; open and longer, more elaborate answers are more challenging. ChatGPT (especially GPT-4) tends to give higher grades than teachers—less often awarding failing grades and more often scoring higher than human examiners. |

| [36] | university or college | foreign language | Infinigo ChatIC | essay | Texts “polished” by ChatGPT (infinigoChatIC) receive much higher scores in automated grading systems (iWrite) than texts written independently or with classic machine translators. The average score increase was about 17%. AI effectively eliminates grammatical errors and significantly increases the diversity and sophistication of vocabulary (e.g., more complex and precise expressions). This results in higher scores for both language and technical/structural aspects of the text. |

| [37] | university or college | na | gpt4 | multiple choice tasks | Generative AI (GPT-4) achieved high agreement with human expert ratings when grading open tutor responses in training scenarios (F1 = 0.85 for selecting the best strategy, F1 = 0.83 for justifying the approach). The Kappa coefficient indicates good agreement (0.65–0.69), although the AI scored somewhat more strictly than humans and was more sensitive to answer length (short answers were more often marked incorrect). Overall, AI grading was slightly more demanding than human grading (average scores were about 25% lower when graded by AI). |

| [38] | university or college | engineering | gpt4o | short answers | GPT-4o (ChatGPT) showed strong agreement with teaching assistants (TAs) in grading conceptual questions in mechanical engineering, especially where grading criteria were clear and unambiguous (Spearman’s p exceeded 0.6 in 7 out of 10 tasks, up to 0.94; low RMSE). |

| [39] | k12 | mixed | gpt3.5 | essay | Essay scores assigned by ChatGPT 3.5 show poor agreement with those assigned by experienced teachers. Agreement was low in three out of four criteria (content, organization, language), and only moderate for mechanics (e.g., punctuation, spelling). On average, ChatGPT 3.5 gave slightly higher grades than humans in each category, but the differences were not statistically significant (except for mechanics, where AI was noticeably more “lenient”). |

| [40] | primary school | math | gpt3.5, gpt4 | calculation tasks | A system based on GPT-3.5 (fine-tuned) achieved higher agreement with teacher ratings than “base” GPT-3.5 and GPT-4, especially for clear, unambiguous criteria. |

| [41] | university or college | computer science, medicine | gpt4 | essay, coding tasks | ChatGPT grading is more consistent and predictable for high-quality work. With weaker or average work, there is greater variability in scores (wider spread), especially in programming tasks. |

| [42] | secondary school | mixed | gpt4 | short answers | GPT-4 using the “chain-of-thought” (CoT) method and few-shot prompting achieved high agreement with human examiners when grading short open-ended answers in science subjects (QWK up to 0.95; Macro F1 up to 1.00). The CoT method allowed AI not only to assign a score but also to generate justification (explanation of the grading decision) in accordance with the criteria (rubrics). |

| [43] | k12 | mixed | bert | short answers | LLM models (here: BERT) achieve high agreement with human ratings in short open-ended response tasks in standardized educational tests (QWK ≥ 0.7 for 11 out of 13 tasks). |

| [44] | university or college | medicine | gpt3.5 | essay | ChatGPT 3.5 could grade and classify medical essays according to established criteria, while also generating detailed, individualized feedback for students. |

| [45] | university or college | medicine | gpt3.5 | essay | ChatGPT 3.5 achieves comparable grading performance to teachers in formative tasks (including critical analysis of medical literature). Overall agreement between ChatGPT and teachers was 67%, and AUCPR (accuracy index) was 0.69 (range: 0.61–0.76). The reliability of grading (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.64, considered acceptable for formative assessment. |

| [46] | primary school | math | gpt4 | calculation tasks | GPT-4, used as an Automated Assessment System (AAS) for open-ended math responses, achieved high agreement with the ratings of three expert teachers for most questions, demonstrating the potential of AI to automate the grading of complex assignments, not just short answers. |

| [47] | university or college | computer science | gpt4 | coding tasks | ChatGPT-4, used as part of the semi-automatic GreAIter tool, achieves very high agreement with human examiners (98.2% accuracy, 100% recall, meaning no real errors in code are missed). Despite this high effectiveness, AI can be overly critical (precision 59.3%)—it generates more false alarms (incorrectly detected errors) than human examiners. |

| [48] | university or college | chemistry | gpt3.5, bard | short answers | Generative AI (e.g., ChatGPT, Bard) can significantly improve the grading of open-ended student work in natural sciences, especially thanks to data augmentation and more precise mapping of students’ reasoning levels. |

| [49] | university or college | computer science | gpt3 | short answers | AI (GPT-3, after fine-tuning) achieved very high agreement with human ratings in classifying the specificity of statements (97% accuracy) and sufficient accuracy in assessing effort (83%). Zero-shot models (without training) were much less accurate—automatic grading performance increases after fine-tuning on human-graded data. |

| [50] | university or college | education | bert | essay | Pretrained models on large datasets, such as BigBird and Longformer, achieved the highest effectiveness in classifying the level of reflection in student assignments (77.2% and 76.3% accuracy, respectively), clearly outperforming traditional “shallow” ML models (e.g., SVM, Random Forest), which did not exceed 60% accuracy. |

| [51] | k12 | mixed | gpt3.5turbo, claude3.5, gpt4turbo, spark | essay | Generative models such as GPT-4 often incorrectly assess the topic relevance of essays and generate feedback that is too general, impractical, or even misleading. This phenomenon results partly from “sycophancy” (excessive leniency) and LLM hallucinations—the models tend to give overly optimistic evaluations. |

| [52] | university or college | chemistry | bert, gpt3.5, gpt4 | other | Language models (LLMs, e.g., GPT-4) perform worse in grading long, multi-faceted, factual answers than in grading short responses—even with advanced techniques and rubrics, F1 for GPT-4 was only 0.69 (for short responses, 0.74). Using a detailed rubric (i.e., breaking grading into many small criteria) improves AI’s results by 9% (accuracy) and 15% (F1) compared to classical, general scoring. Rubrics help the model better identify which aspects of the answer are correct or incorrect. GPT-4 achieves the highest results among tested models (F1 = 0.689, accuracy 70.9%), but still does not perform as well as for short answers and often misses nuances in complex, multi-faceted student answers. |

| [53] | university or college | computer science | other | essay | ChatGPT should not be used as a standalone grading tool. AI-generated grades are unpredictable, can be inconsistent, and do not always match the criteria used by teachers. |

| [54] | university or college | education | other | essay | ChatGPT 3.5 achieved moderate or good agreement with teacher grades (ICC from 0.6 to 0.8 in various categories), meaning it can effectively score student work based on the same criteria as humans. ChatGPT generated more feedback, often giving general suggestions and summaries, but less frequently providing specific solutions and explanations. AI feedback was less precise, less detailed, and less emotionally supportive, but more “inspiring” for some students. Students implemented teacher suggestions more often (80.2%) than ChatGPT’s (59.9%), and AI feedback was more frequently rejected (40% of cases). |

| [55] | university or college | mixed | gpt4o, claude3.5, gemini1.5pro | other | The newest models (Claude 3.5 Sonnet, GPT-4o, Qwen2 72B) can be a valuable support in grading complex, open-ended tasks (authentic assignments) in higher education, using rubric-based assessment. GPT-4o and Claude 3.5 Sonnet produce results closest to human grading in terms of score distribution and consistency. |

| [56] | primary school | math | gpt4o | calculation tasks | GPT-4o can effectively support the assessment of tasks requiring logical and spatial reasoning in children, provided that advanced prompting techniques are used. Simple prompting (Zero-Shot/Few-Shot) is insufficient—grading effectiveness by LLMs increases significantly when using advanced methods, such as Visualization of Thought and Self-Consistency (multiple generations with majority voting). In the best settings, GPT-4o achieved 93–100% correct grades on tasks testing logical and spatial skills, such as coloring objects according to math-logical-spatial rules. |

| [57] | university or college | foreign language | bert, gpt3.5turbo | essay | ChatGPT (GPT-3.5-turbo) performs much worse than dedicated BERT or SIAM models in the task of assessing whether a pair of student essays represents progression (improvement) or regression in language skills. ChatGPT’s effectiveness in this task was significantly lower (accuracy ∼56%) than the best models based on BERT architecture. |

| [58] | university or college | medicine | gpt4 | essay | The results obtained by ChatGPT strongly correlate with human ratings, especially for questions with clearer scope. AI enables immediate grading of large numbers of assignments and provides individual, detailed rubric-based feedback—which is hard for a single teacher to deliver with large groups. |

| [59] | k12 | mixed | gpt4, gpt3.5 | short answers | The GPT-4 model using few-shot prompting achieved human-level agreement (Cohen’s Kappa 0.70), very close to expert level (Kappa 0.75). AI grades were stable regardless of subject (history/science), task difficulty, and student age. |

| [60] | secondary school | na | bert, gpt3.5turbo | multiple choice tasks | Tuned ChatGPT outperforms the state-of-the-art BERT model in both multi-label and multi-class tasks. The average grading performance improvement for ChatGPT was about 9.1% compared to BERT, and for more complex (multi-class) tasks even over 10%. The “base” version of GPT-3.5 is not effective enough—tuning is necessary for subject/class/task-specific data. |

| [61] | university or college | computer science | bert | coding tasks | A fine-tuned LLM can automatically assess student work in terms of higher-order cognitive skills (HOTS) without expert involvement, with greater accuracy and scalability than traditional systems. |

| [62] | primary school | foreign language | gpt4trubo | essay | Scores assigned by ChatGPT 3.5 were generally comparable to those given by academic staff. The average exact agreement between AI and humans was 67%. For individual criteria, agreement ranged from 59% to 81%. Using ChatGPT for grading reduced grading time fivefold (from about 7 minutes to 2 minutes per assignment), potentially saving hundreds of teacher work hours. |

| [63] | university or college | engineering | gpt3.5 | short answers | ChatGPT 3.5 more often assigns average grades (e.g., C, D, E) and less frequently than humans gives the highest or lowest marks. ChatGPT is consistent—repeated grading of the same work yielded similar results. |

| [64] | k12 | computer science | other | coding tasks | The average effectiveness of GPT autograder for simple tasks was 91.5%, and for complex ones—only 51.3%. There was a strong correlation between LLM and official autograder scores (r = 0.84), but GPT-4 tended to underestimate scores, i.e., giving students lower results than they actually deserved (prevalence of so-called false negatives). |

| [65] | university or college | biology | gpt4 | short answers | SteLLA achieved “substantial agreement” with human grading—Cohen’s Kappa was 0.67 (compared to 0.83 for two human graders), and raw agreement was 0.84 (versus 0.92 for humans). This means the automated grading system is close to human-level agreement, though not equal to it yet. |

| [66] | university or college | math | gpt4, gpt3.5 | calculation tasks | The average grade given by GPT-4 for student solutions is very close to grades assigned by human examiners, but detailed accuracy is lower—random errors occur, equivalent solutions can be missed, and calculation mistakes appear. |

| [67] | university or college | foreign language | gpt4, bard | essay | The highest reliability was obtained for the FineTuned ChatGPT version (ICC = 0.972), slightly lower for ChatGPT Default (ICC = 0.947), and Bard (ICC = 0.919). The reliability of LLMs exceeded even some human examiners in terms of repeatability. The best match between LLM and human examiners was for “objective” criteria such as grammar and mechanics. Both ChatGPT and Bard almost perfectly matched human scores for grammar and mechanics (punctuation, spelling). |

| [68] | university or college | engineering, foreign language | gpt4, gpt3.5 | essay | ChatGPT (both 3.5 and 4) grades student essays more “generously” than human examiners. The average grades assigned by ChatGPT are higher than those given by teachers, regardless of model version. AI often gives higher grades even if the work quality is not high, leading to a “ceiling effect” (grades clustering near the top end). The agreement between human examiners was high (“good”), while for ChatGPT-3.5 it was only “moderate” and for ChatGPT-4 even “low”. |

3.2. Role of GenAI in grading

3.3. AI vs. human grading quality

3.4. Factors impacting GenAI grading performance

3.5. Educational and pedagogical implications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- adopt common reporting standards and stronger sampling beyond convenience cohorts;

- track model generations with preregistered protocols;

- expand multilingual and modality-diverse evaluations; and

- connect grading metrics to downstream learning outcomes and equity impacts.

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jukiewicz, M. How generative artificial intelligence transforms teaching and influences student wellbeing in future education. Frontiers in Education 2025, Volume 10. [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Xu, M.; Patros, P.; Wu, H.; Kaur, R.; Kaur, K.; Fuller, S.; Singh, M.; Arora, P.; Parlikad, A.K.; et al. Transformative effects of ChatGPT on modern education: Emerging Era of AI Chatbots. Internet of Things and Cyber-Physical Systems 2024, 4, 19–23. [CrossRef]

- Al Murshidi, G.; Shulgina, G.; Kapuza, A.; Costley, J. How understanding the limitations and risks of using ChatGPT can contribute to willingness to use. Smart Learning Environments 2024, 11, 36. [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.; Silva, G.; Arocutipa, J.; Berrios, H.; Marcos Rodriguez, M.; Reyes, G.; Lopez, H.; Teves, R.; Rivera, H.; Arias-Gonzáles, J. Effect of Chat GPT on the digitized learning process of university students. Journal of Namibian Studies : History Politics Culture 2023, 33, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Hung, J.; Chen, J. The Benefits, Risks and Regulation of Using ChatGPT in Chinese Academia: A Content Analysis. Social Sciences 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Raile, P. The usefulness of ChatGPT for psychotherapists and patients. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2024, 11, 1–8.

- De Duro, E.S.; Improta, R.; Stella, M. Introducing CounseLLMe: A dataset of simulated mental health dialogues for comparing LLMs like Haiku, LLaMAntino and ChatGPT against humans. Emerging Trends in Drugs, Addictions, and Health 2025, p. 100170. [CrossRef]

- Maurya, R.K.; Montesinos, S.; Bogomaz, M.; DeDiego, A.C. Assessing the use of ChatGPT as a psychoeducational tool for mental health practice. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 2025, 25, e12759, [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/capr.12759]. [CrossRef]

- Memarian, B.; Doleck, T. ChatGPT in education: Methods, potentials, and limitations. Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans 2023, 1, 100022. [CrossRef]

- Diab Idris, M.; Feng, X.; Dyo, V. Revolutionizing Higher Education: Unleashing the Potential of Large Language Models for Strategic Transformation. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 67738–67757. [CrossRef]

- Hadi Mogavi, R.; Deng, C.; Juho Kim, J.; Zhou, P.; D. Kwon, Y.; Hosny Saleh Metwally, A.; Tlili, A.; Bassanelli, S.; Bucchiarone, A.; Gujar, S.; et al. ChatGPT in education: A blessing or a curse? A qualitative study exploring early adopters’ utilization and perceptions. Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans 2024, 2, 100027. [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.O.; Lee, Y.J. Prompt: ChatGPT, Create My Course, Please! Education Sciences 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Onal, S.; Kulavuz-Onal, D. A Cross-Disciplinary Examination of the Instructional Uses of ChatGPT in Higher Education. Journal of Educational Technology Systems 2024, 52, 301–324. [CrossRef]

- Li, M. The Impact of ChatGPT on Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: Challenges, Opportunities, and Future Scope. Encyclopedia of Information Science and Technology, Sixth Edition 2025, pp. 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Lucas, H.C.; Upperman, J.S.; Robinson, J.R. A systematic review of large language models and their implications in medical education. Medical Education 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jukiewicz, M. The future of grading programming assignments in education: The role of ChatGPT in automating the assessment and feedback process. Thinking Skills and Creativity 2024, 52, 101522. [CrossRef]

- Kıyak, Y.S.; Emekli, E. ChatGPT prompts for generating multiple-choice questions in medical education and evidence on their validity: a literature review. Postgraduate medical journal 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.; Wafik, H.A.; Mahbub, S.; Das, J. Gen Z and Generative AI: Shaping the Future of Learning and Creativity. Cognizance Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies 2024, 4, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.R. Navigating the integration of generative artificial intelligence in higher education: Opportunities, challenges, and strategies for fostering ethical learning. Advances in Biomedical and Health Sciences 2025, 4. [CrossRef]

- Reimer, E.C. Examining the Role of Generative AI in Enhancing Social Work Education: An Analysis of Curriculum and Assessment Design. Social Sciences 2024, 13, 648. [CrossRef]

- Tzirides, A.O.O.; Zapata, G.; Kastania, N.P.; Saini, A.K.; Castro, V.; Ismael, S.A.; You, Y.l.; dos Santos, T.A.; Searsmith, D.; O’Brien, C.; et al. Combining human and artificial intelligence for enhanced AI literacy in higher education. Computers and Education Open 2024, 6, 100184.

- Wu, D.; Chen, M.; Chen, X.; Liu, X. Analyzing K-12 AI education: A large language model study of classroom instruction on learning theories, pedagogy, tools, and AI literacy. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2024, 7, 100295.

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [CrossRef]

- Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kirtley, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Ayala, A.P.; Moher, D.; Page, M.J.; Koffel, J.B.; Blunt, H.; Brigham, T.; Chang, S.; et al. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Systematic Reviews 2021, 10, 39. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for information 2018, 34, 285–291.

- Grévisse, C. LLM-based automatic short answer grading in undergraduate medical education. BMC Medical Education 2024, 24, 1060.

- Jiang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Pan, Z.; He, J.; Xie, K. Exploring the role of artificial intelligence in facilitating assessment of writing performance in second language learning. Languages 2023, 8, 247.

- Li, Z.; Lloyd, S.; Beckman, M.; Passonneau, R.J. Answer-state recurrent relational network (AsRRN) for constructed response assessment and feedback grouping. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, 2023, pp. 3879–3891.

- Hackl, V.; Müller, A.E.; Granitzer, M.; Sailer, M. Is GPT-4 a reliable rater? Evaluating consistency in GPT-4’s text ratings. Frontiers in Education 2023, 8, 1272229. [CrossRef]

- Azaiz, I.; Deckarm, O.; Strickroth, S. Ai-enhanced auto-correction of programming exercises: How effective is gpt-3.5? arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.10737 2023.

- Acar, S.; Dumas, D.; Organisciak, P.; Berthiaume, K. Measuring original thinking in elementary school: Development and validation of a computational psychometric approach. Journal of Educational Psychology 2024, 116, 953–981. [CrossRef]

- Schleifer, A.G.; Klebanov, B.B.; Ariely, M.; Alexandron, G. Transformer-based Hebrew NLP models for short answer scoring in biology. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 18th Workshop on Innovative Use of NLP for Building Educational Applications (BEA 2023), 2023, pp. 550–555.

- Li, J.; Huang, J.; Wu, W.; Whipple, P.B. Evaluating the role of ChatGPT in enhancing EFL writing assessments in classroom settings: A preliminary investigation. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2024, 11, 1268. [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.H.; Ginter, F. Automatic short answer grading for finnish with chatgpt. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2024, Vol. 38, pp. 23173–23181.

- Dong, D. Tapping into the pedagogical potential of InfinigoChatIC: Evidence from iWrite scoring and comments and Lu & Ai’s linguistic complexity analyzer. Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) Special Issue on ChatGPT 2024.

- Thomas, D.R.; Lin, J.; Bhushan, S.; Abboud, R.; Gatz, E.; Gupta, S.; Koedinger, K.R. Learning and ai evaluation of tutors responding to students engaging in negative self-talk. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Eleventh ACM Conference on Learning@ Scale, 2024, pp. 481–485.

- Gao, R.; Guo, X.; Li, X.; Narayanan, A.B.L.; Thomas, N.; Srinivasa, A.R. Towards Scalable Automated Grading: Leveraging Large Language Models for Conceptual Question Evaluation in Engineering. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of Machine Learning Research. FM-EduAssess at NeurIPS 2024 Workshop, 2024.

- Jackaria, P.M.; Hajan, B.H.; Mastul, A.R.H. A comparative analysis of the rating of college students’ essays by ChatGPT versus human raters. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research 2024, 23.

- Jin, H.; Kim, Y.; Park, Y.S.; Tilekbay, B.; Son, J.; Kim, J. Using large language models to diagnose math problem-solving skills at scale. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the eleventh ACM conference on learning@ scale, 2024, pp. 471–475.

- Li, J.; Jangamreddy, N.K.; Hisamoto, R.; Bhansali, R.; Dyda, A.; Zaphir, L.; Glencross, M. AI-assisted marking: Functionality and limitations of ChatGPT in written assessment evaluation. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 2024, 40, 56–72.

- Cohn, C.; Hutchins, N.; Le, T.; Biswas, G. A Chain-of-Thought Prompting Approach with LLMs for Evaluating Students’ Formative Assessment Responses in Science. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2024, Vol. 38, pp. 23182–23190. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Johnson, M.; Ruan, C. Investigating Sampling Impacts on an LLM-Based AI Scoring Approach: Prediction Accuracy and Fairness. Journal of Measurement and Evaluation in Education and Psychology 2024, 15, 348–360. [CrossRef]

- Shamim, M.S.; Zaidi, S.J.A.; Rehman, A. The revival of essay-type questions in medical education: harnessing artificial intelligence and machine learning. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan 2024, 34, 595–599. [CrossRef]

- Sreedhar, R.; Chang, L.; Gangopadhyaya, A.; Shiels, P.W.; Loza, J.; Chi, E.; Gabel, E.; Park, Y.S. Comparing Scoring Consistency of Large Language Models with Faculty for Formative Assessments in Medical Education. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2025, 40, 127–134.

- Lee, U.; Kim, Y.; Lee, S.; Park, J.; Mun, J.; Lee, E.; Kim, H.; Lim, C.; Yoo, Y.J. Can we use GPT-4 as a mathematics evaluator in education?: Exploring the efficacy and limitation of LLM-based automatic assessment system for open-ended mathematics question. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education 2024, pp. 1–37.

- Grandel, S.; Schmidt, D.C.; Leach, K. Applying Large Language Models to Enhance the Assessment of Parallel Functional Programming Assignments. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Large Language Models for Code, New York, NY, USA, 2024; LLM4Code ’24, p. 102–110. [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.P.; Graulich, N. Navigating the data frontier in science assessment: Advancing data augmentation strategies for machine learning applications with generative artificial intelligence. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2024, 7, 100265.

- Menezes, T.; Egherman, L.; Garg, N. AI-grading standup updates to improve project-based learning outcomes. In Proceedings of the 2024 on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education V. 1; 2024; pp. 17–23.

- Zhang, C.; Hofmann, F.; Plößl, L.; Gläser-Zikuda, M. Classification of reflective writing: A comparative analysis with shallow machine learning and pre-trained language models. Education and Information Technologies 2024, 29, 21593–21619.

- Zhuang, X.; Wu, H.; Shen, X.; Yu, P.; Yi, G.; Chen, X.; Hu, T.; Chen, Y.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. TOREE: Evaluating topic relevance of student essays for Chinese primary and middle school education. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics ACL 2024, 2024, pp. 5749–5765.

- Sonkar, S.; Ni, K.; Tran Lu, L.; Kincaid, K.; Hutchinson, J.S.; Baraniuk, R.G. Automated long answer grading with RiceChem dataset. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education. Springer, 2024, pp. 163–176.

- Huang, C.W.; Coleman, M.; Gachago, D.; Van Belle, J.P. Using ChatGPT to Encourage Critical AI Literacy Skills and for Assessment in Higher Education. In Proceedings of the ICT Education; Van Rensburg, H.E.; Snyman, D.P.; Drevin, L.; Drevin, G.R., Eds., Cham, 2024; pp. 105–118. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Yao, Y.; Xiao, L.; Yuan, M.; Wang, J.; Zhu, X. Can ChatGPT effectively complement teacher assessment of undergraduate students’ academic writing? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 2024, 49, 616–633.

- Agostini, D.; Picasso, F.; Ballardini, H.; et al. Large Language Models for the Assessment of Students’ Authentic Tasks: A Replication Study in Higher Education. In Proceedings of the CEUR Workshop Proceedings, 2024, Vol. 3879.

- Tapia-Mandiola, S.; Araya, R. From play to understanding: Large language models in logic and spatial reasoning coloring activities for children. AI 2024, 5, 1870–1892.

- Lin, N.; Wu, H.; Zheng, W.; Liao, X.; Jiang, S.; Yang, A.; Xiao, L. IndoCL: Benchmarking Indonesian Language Development Assessment. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2024, 2024, pp. 4873–4885.

- Quah, B.; Zheng, L.; Sng, T.J.H.; Yong, C.W.; Islam, I. Reliability of ChatGPT in automated essay scoring for dental undergraduate examinations. BMC Medical Education 2024, 24, 962. [CrossRef]

- Henkel, O.; Hills, L.; Boxer, A.; Roberts, B.; Levonian, Z. Can large language models make the grade? an empirical study evaluating llms ability to mark short answer questions in k-12 education. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Eleventh ACM Conference on Learning@ Scale, 2024, pp. 300–304.

- Latif, E.; Zhai, X. Fine-tuning ChatGPT for automatic scoring. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2024, 6, 100210. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Li, Y.; He, X.; Fang, J.; Yan, Z.; Xie, C. An assessment framework of higher-order thinking skills based on fine-tuned large language models. Expert Systems with Applications 2025, 272, 126531.

- Fokides, E.; Peristeraki, E. Comparing ChatGPT’s correction and feedback comments with that of educators in the context of primary students’ short essays written in English and Greek. Education and Information Technologies 2025, 30, 2577–2621.

- Flodén, J. Grading exams using large language models: A comparison between human and AI grading of exams in higher education using ChatGPT. British educational research journal 2025, 51, 201–224.

- Gonzalez-Maldonado, D.; Liu, J.; Franklin, D. Evaluating GPT for use in K-12 Block Based CS Instruction Using a Transpiler and Prompt Engineering. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 56th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education V. 1, New York, NY, USA, 2025; SIGCSETS 2025, p. 388–394. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; White, B.; Ding, A.; Costa, R.; Hachem, A.; Ding, W.; Chen, P. Stella: A structured grading system using llms with rag. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData). IEEE, 2024, pp. 8154–8163.

- Gandolfi, A. GPT-4 in education: Evaluating aptness, reliability, and loss of coherence in solving calculus problems and grading submissions. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education 2025, 35, 367–397.

- Yavuz, F.; Çelik, Ö.; Yavaş Çelik, G. Utilizing large language models for EFL essay grading: An examination of reliability and validity in rubric-based assessments. British Journal of Educational Technology 2025, 56, 150–166.

- Manning, J.; Baldwin, J.; Powell, N. Human versus machine: The effectiveness of ChatGPT in automated essay scoring. Innovations in Education and Teaching International 2025, pp. 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Gurin Schleifer, A.; Beigman Klebanov, B.; Ariely, M.; Alexandron, G. Transformer-based Hebrew NLP models for Short Answer Scoring in Biology. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 18th Workshop on Innovative Use of NLP for Building Educational Applications (BEA 2023); Kochmar, E.; Burstein, J.; Horbach, A.; Laarmann-Quante, R.; Madnani, N.; Tack, A.; Yaneva, V.; Yuan, Z.; Zesch, T., Eds., Toronto, Canada, 2023; pp. 550–555. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.R.; Lin, J.; Bhushan, S.; Abboud, R.; Gatz, E.; Gupta, S.; Koedinger, K.R. Learning and AI Evaluation of Tutors Responding to Students Engaging in Negative Self-Talk. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Eleventh ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale, New York, NY, USA, 2024; L@S ’24, p. 481–485. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Yao, Y.; Xiao, L.; Yuan, M.; Wang, J.; Zhu, X. Can ChatGPT effectively complement teacher assessment of undergraduate students’ academic writing? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 2024, 49, 616–633. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Zhang, K. Artificial Intelligence for Computer Science Education in Higher Education: A Systematic Review of Empirical Research Published in 2003–2023: M. Zhu, K. Zhang. Technology, Knowledge and Learning 2025, pp. 1–25.

- Pereira, A.F.; Mello, R.F. A Systematic Literature Review on Large Language Models Applications in Computer Programming Teaching Evaluation Process. IEEE Access 2025.

- Albadarin, Y.; Saqr, M.; Pope, N.; Tukiainen, M. A systematic literature review of empirical research on ChatGPT in education. Discover Education 2024, 3, 60.

- Lo, C.K.; Yu, P.L.H.; Xu, S.; Ng, D.T.K.; Jong, M.S.y. Exploring the application of ChatGPT in ESL/EFL education and related research issues: A systematic review of empirical studies. Smart Learning Environments 2024, 11, 50.

- Dikilitas, K.; Klippen, M.I.F.; Keles, S. A systematic rapid review of empirical research on students’ use of ChatGPT in higher education. Nordic Journal of Systematic Reviews in Education 2024, 2. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).