Submitted:

12 September 2025

Posted:

15 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

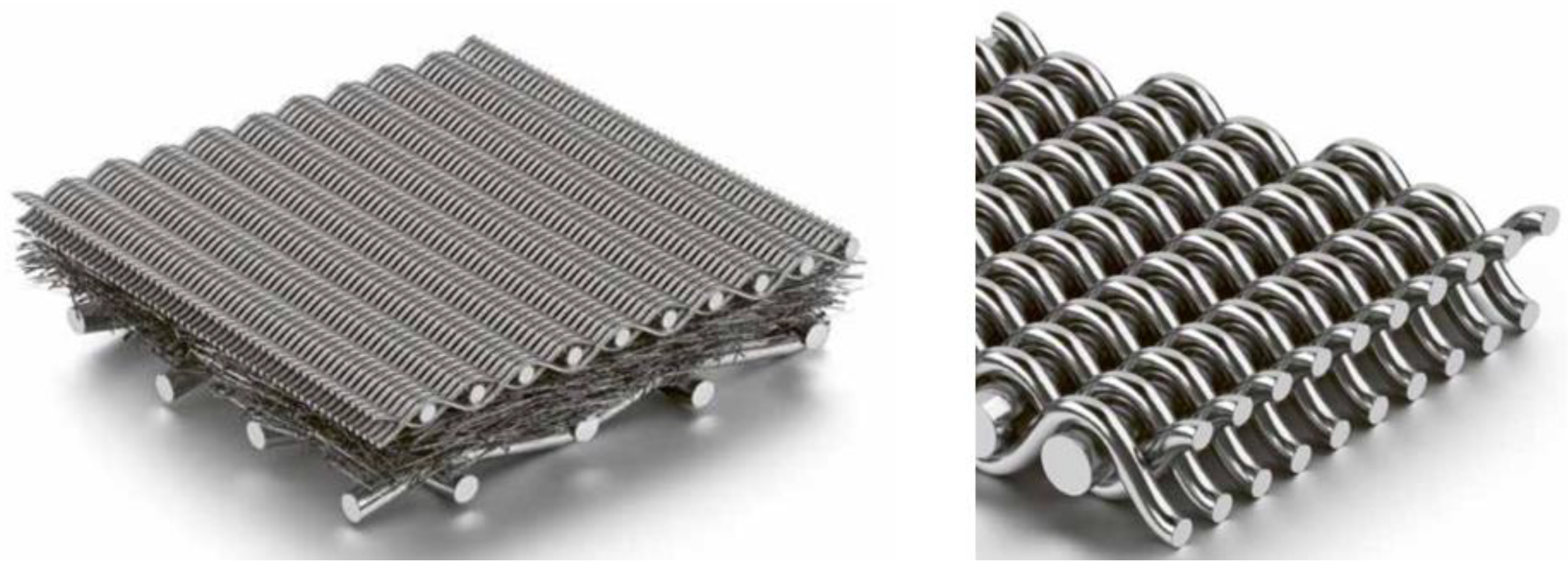

2. Metal Filters

2.1. Properties

2.2. Use of Metal Filters

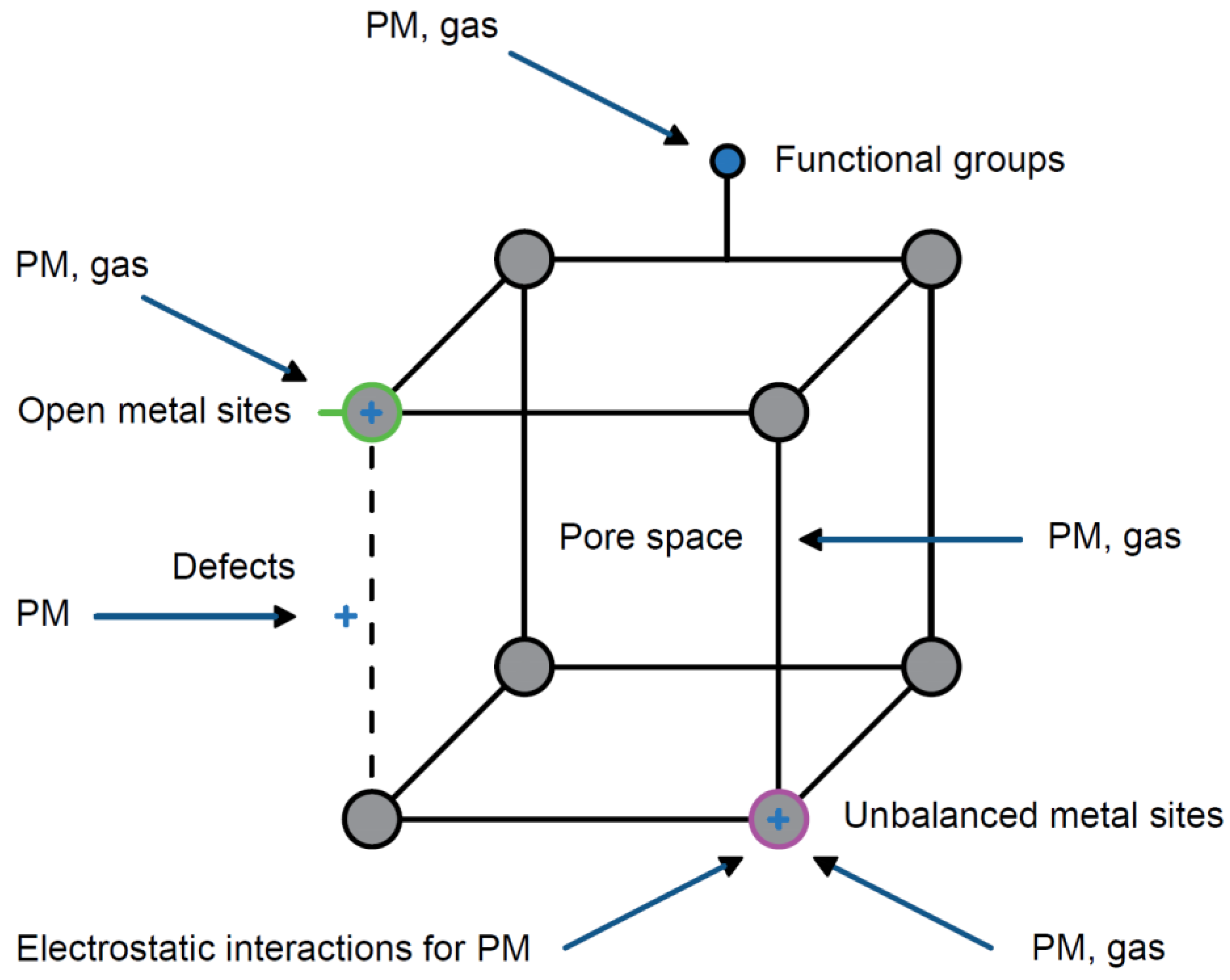

3. MOF-Polymer Composites

3.1. Properties

3.2. Use of MOF-Polymer Composites

4. Tested Filters and Achieved Filtration Parameters

4.1. Metal Mesh Filters

4.2. Metal Composite Filters

4.3. MOF-Polymer Composites

4.4. Summary of Tested Filters

4.4.1. Recommendation for Improving Filter Performance Testing

5. Commercially Offered Metal Filters

5.1. Summary of Commercially Offered Metal Filters

6. Discussion

6.1. Filtration and Adsorption Mechanisms of the Described Filters

6.2. Regeneration of the Described Filters

6.3. Comparison and Practical Potential of the Described Filters

7. Conclusion and Future Challenges

- Metal filters and MOF-polymer composites are very promising materials for reducing air pollution. Their usage and maintenance depend on their thermal, chemical (e.g., oxidation), and mechanical resistance. The choice of material must be adapted to the operating environment, including the chemical composition of the flue gas, temperature, and humidity. Further research is needed to improve the thermal resistance of MOF-based filters.

- For comparing the efficiency of the tested filters, a uniform measurement methodology is necessary. This is related to the refinement of standards for measuring the filtration efficiency of filter materials for high-temperature flue gas filtration.

- With stricter limits and greater awareness of air pollution, filters may be introduced in combustion systems, but further research is still needed for the practical application of an efficient, operationally safe, and recyclable filter at an acceptable financial cost.

Acknowledgements

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wei, W.; Tao, Y.; Feng, T.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; Pang, J.; Li, D.; Xu, G.; Liang, X.; Gao, M.; et al. Self-Assembly-Dominated Hierarchical Porous Nanofibrous Membranes for Efficient High-Temperature Air Filtration and Unidirectional Water Penetration. J. Memb. Sci. 2023, 686, 121996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Tian, E.; Zhang, Y.; Mo, J. Utilizing Electrostatic Effect in Fibrous Filters for Efficient Airborne Particles Removal: Principles, Fabrication, and Material Properties. Appl. Mater. Today 2022, 26, 101369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, Y. Air Pollution and Lung Cancer Risks. In Encyclopedia of Environmental Health; Elsevier, 2011; pp. 26–38.

- Anderson, J.O.; Thundiyil, J.G.; Stolbach, A. Clearing the Air: A Review of the Effects of Particulate Matter Air Pollution on Human Health. J. Med. Toxicol. 2012, 8, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Yu, Z.; Yu, C.; Chen, H.; Pan, F. An Electrically Renewable Air Filter with Integrated 3D Nanowire Networks. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State of Global Air Report 2024 | State of Global Air. Available online: https://www.stateofglobalair.org/resources/report/state-global-air-report-2024 (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Zhu, C.; Yang, F.; Xue, T.; Wali, Q.; Fan, W.; Liu, T. Metal-Organic Framework Decorated Polyimide Nanofiber Aerogels for Efficient High-Temperature Particulate Matter Removal. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 300, 121881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Baeyens, J.; Dewil, R.; Appels, L.; Zhang, H.; Deng, Y. Advances in Rigid Porous High Temperature Filters. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 139, 110713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhuo, L.; Ning, D.; Yan, N.; Li, J.; Chen, S.; Lu, Z. Multiple Hydrogen Bonding Self-Assembly Tailored Electrospun Polyimide Hybrid Filter for Efficient Air Pollution Control. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 412, 125260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, F.; Baumbach, G.; Straub, D.; Thorwarth, H.; Vogt, U. Novel Metal Mesh Filter Equipped with Pulse-Jet Regeneration for Small-Scale Biomass Boilers. Biomass and Bioenergy 2022, 163, 106520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaivosoja, T.; Jalava, P.I.; Lamberg, H.; Virén, A.; Tapanainen, M.; Torvela, T.; Tapper, U.; Sippula, O.; Tissari, J.; Hillamo, R.; et al. Comparison of Emissions and Toxicological Properties of Fine Particles from Wood and Oil Boilers in Small (20–25 KW) and Medium (5–10 MW) Scale. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 77, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sippula, O.; Hokkinen, J.; Puustinen, H.; Yli-Pirilä, P.; Jokiniemi, J. Comparison of Particle Emissions from Small Heavy Fuel Oil and Wood-Fired Boilers. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 4855–4864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, L.S.; Tullin, C.; Leckner, B.; Sjövall, P. Particle Emissions from Biomass Combustion in Small Combustors. Biomass and Bioenergy 2003, 25, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Ji, Z.; Xu, Q.; Li, H. Performance Assessment of Sintered Metal Fiber Filters in Fluid Catalytic Cracking Unit. Int. J. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2014, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metallic Mesh Filter Elements for Hot Gas Filtration Available online: https://www.gkd-group.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/hot-gas-filtration_brochure_c_gkd.pdf.

- Gregorovičová, E.; Pospíšil, J. Ceramic Filters for High-Temperature Flue Gas Filtration and Their Regeneration: A Review of the Current State of Knowledge. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 190, 688–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Lai, N.; Jiang, B.; Liu, X.; Xia, D. An Efficient and Continuous Filter Operation for Dust-laden Flue Gas Based on a Self-cleaning Stainless Steel Weaved Filter. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2023, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, H. PTFE Foam Coating Ultrafine Glass Fiber Composite Filtration Material with Ultra-Clean Emissions. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 352, 128219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FRMC Hot Gas Filter – Replace Ceramic for Ultra-High TEMP. Available online: https://www.metalfilter.org/metalfilter/frmc-hot-gas-filter/index.html (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Rahimpour, M.R.; Makarem, M.A.; Meshksar, M. Advances in Synthesis Gas: Methods, Technologies and Applications: Syngas Purification and Separation; Elsevier Science, 2022; ISBN 9780323985215.

- Liu, P.; Chen, G.F. Porous Materials: Processing and Applications; Elsevier Science, 2014; ISBN 9780124078376.

- Li, L.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, Z.; Gu, H.; Shi, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, M.; Zhao, Z. Improved Design of Metal Fiber Filter Materials: Experiment and Theory. J. Memb. Sci. 2023, 675, 121559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarleton, E.S. Progress in Filtration and Separation; Elsevier Science, 2014; ISBN 9780123983077.

- Shi, J.; Kumar, C. The Effect of Fibre Surface Roughness on the Mechanical Behaviour of Ceramic Matrix Composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1998, 250, 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israelachvili, J.N. Intermolecular and Surface Forces; Intermolecular and Surface Forces; Academic Press, 2011; ISBN 9780123919335.

- Li, L.; Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Hou, X.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Gu, H.; Ding, R. Three-Dimensional Numerical Simulation and Structural Optimization of Filtration Performance of Pleated Cylindrical Metal Fiber Filter. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 311, 123224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeyens, J. The Growing Potential of Sintered Metal Fiber Filters. Proc6th Glob Con f Mater Sci Eng 2017, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Schildermans, I.; Baeyens, J.; Smolders, K. Pulse Jet Cleaning of Rigid Filters: A Literature Review and Introduction to Process Modelling. Filtr. Sep. 2004, 41, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struschka, M.; Goy, J. Entwicklung Eines Kompakten Und Kostengünstigen Gewebefilters Für Biomassekessel. Inst. für Feuerungs-und Kraftwerkstechnik (IFK), Univ. Stuttgart 2015.

- Shah, Y.T. Chemical Energy from Natural and Synthetic Gas; CRC Press, 2017; ISBN 9781523114054.

- Yang, L.; Ji, Z.; Wu, X.; Ma, W. Application and Operating Experience of Sintered Metal Fiber Hot Gas Filters for FCC Unit. Procedia Eng. 2015, 102, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; Kayal, N.; Chakrabarti, O.; Innocentini, M.D.M. Permeation Behavior of Oxide Bonded SiC Ceramics at High Temperature and Prediction of Pressure Drop in Candle Filters. Trans. Indian Ceram. Soc. 2022, 81, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, S.; Rubow, K.L.; Sekellick, R. Sintered Metal Hot Gas Filters Available online: https://mottcorp.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Sintered-Metal-Hot-Gas-Filters.pdf.

- childermans, I.; Baeyens, J. Hot Gas Filtration: A Growing Market. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 4th International Conference for Conveying and Handling Particulate Solids, Budapest, May 2003; 2003.

- Kamp, C.J.; Folino, P.; Wang, Y.; Sappok, A.; Ernstmeyer, J.; Saeid, A.; Singh, R.; Kharraja, B.; Wong, V.W. Ash Accumulation and Impact on Sintered Metal Fiber Diesel Particulate Filters. SAE Int. J. Fuels Lubr. 2015, 8, 2015–2015-01–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, Z.; Gu, H.; Yuan, H.; Cao, S. Numerical Simulation Study on Depth Filtration Performance of Metal Fiber Pre-Filters with Different Pleat Structures. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2024, 425, 113337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, Z.; Gu, H.; Wang, Y.; Yu, X. Numerical Simulation Study on the Filtration Performance of Metal Fiber Filters. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2024, 171, 105169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-W.; Kim, Y.-I.; Park, C.; Aldalbahi, A.; Alanazi, H.S.; An, S.; Yarin, A.L.; Yoon, S.S. Reusable and Durable Electrostatic Air Filter Based on Hybrid Metallized Microfibers Decorated with Metal–Organic–Framework Nanocrystals. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 85, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Gao, Q.; Zhou, S.; Tang, G.; Xiang, T.; Chun, T.; Zhang, K.; Long, H.; Qian, F.; Li, G. Ultra-Superhydrophobic MOFs Coated on Polydopamine-Modified Polyethylene Terephthalate for Efficient Removal of Particulate Matter. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 466, 143083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-M.; Xie, L.-H.; Wu, Y. Recent Advances in the Shaping of Metal–Organic Frameworks. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 2840–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Wu, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, J. Electrospun Polyimide/Metal-Organic Framework Nanofibrous Membrane with Superior Thermal Stability for Efficient PM 2.5 Capture. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 11904–11909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soleimani, B.; Niknam Shahrak, M.; Walton, K.S. The Influence of Different Functional Groups on Enhancing CO2 Capture in Metal-Organic Framework Adsorbents. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2024, 163, 105638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yin, F.; Zhang, X.-F.; Zheng, T.; Yao, J. Delignified Wood Filter Functionalized with Metal-Organic Frameworks for High-Efficiency Air Filtration. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 293, 121095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Dong, X.; Chen, Z.; Lai, Y. Particulate Matter Capturing via Naturally Dried ZIF-8/Graphene Aerogels under Harsh Conditions. iScience 2019, 16, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, S.; Yao, C.; Ren, W.; Chen, C.; Zhang, L. Metal–Organic Framework-Based Nanofiber Filters for Effective Indoor Air Quality Control. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 15807–15814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Niu, H.; Wu, D. Polyimide Fibers with High Strength and High Modulus: Preparation, Structures, Properties, and Applications. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2018, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Low, Z.-X.; Gore, D.B.; Kumar, R.; Asadnia, M.; Zhong, Z. Porous Metal–Organic Framework-Based Filters: Synthesis Methods and Applications for Environmental Remediation. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 430, 133160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, K.; Bowlin, G.L. Electrospinning Jets and Nanofibrous Structures. Biomicrofluidics 2011, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Wang, P.; Shi, J.; Li, F.; Li, W.; Lyu, B.; Ma, J. A Green Chemistry Approach to Leather Tanning Process: Cage-like Octa(Aminosilsesquioxane) Combined with Tetrakis(Hydroxymethyl)Phosphonium Sulfate. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 1102–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Riccardis, M.F. Electrospun Nanofibrous Membranes for Air Filtration: A Critical Review. Compounds 2023, 3, 390–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Rind, N.A.; Tang, N.; Liu, H.; Yin, X.; Yu, J.; Ding, B. Electrospun Nanofibers for Air Filtration. In Electrospinning: Nanofabrication and Applications; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 365–389.

- Wang, A.; Fan, R.; Zhou, X.; Hao, S.; Zheng, X.; Yang, Y. Hot-Pressing Method To Prepare Imidazole-Based Zn(II) Metal–Organic Complexes Coatings for Highly Efficient Air Filtration. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 9744–9755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, Y.; Niu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Pan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C. Encrusting MOF Nanoparticles onto Nanofibers via Spray-Initiated Synthesis to Boost the Filtration Performances of Nanofiber Membranes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 331, 125569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhen, Y.; Feng, Y.; Jiang, X.; Qin, Z.; Yang, W.; Qie, Y. Polyacrylonitrile@TiO2 Nanofibrous Membrane Decorated by MOF for Efficient Filtration and Green Degradation of PM2.5. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 635, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltrop, L.; Härdtlein, M.; Jenssen, T.; Henßler, M.; Kruck, C.; Özdemnir, E.D.; Hartmann, H.; Poboss, N.; Scheffknecht, G. Leitfaden Feste Biobrennstoffe:[Planung, Betrieb Und Wirtschaftlichkeit von Bioenergieanlagen Im Mittleren Und Großen Leistungsbereich](4., Vollst. Überarb. Aufl.). Gülzow-Prüzen FNR 2014.

- Xie, B.; Li, S.; Chu, W.; Liu, C.; Hu, S.; Jin, H.; Zhou, F. Improving Filtration and Pulse-Jet Cleaning Performance of Metal Web Filter Media by Coating with Polytetrafluoroethylene Microporous Membrane. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020, 136, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, W.; Liang, Y.; Dong, D.; Lin, J. FeAl/Al2O3 Porous Composite Microfiltration Membrane for Highly Efficiency High-temperature Particulate Matter Capturing. J. Porous Mater. 2021, 28, 955–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.M.; Hirai, T.; Kumakawa, A.; Yuan, R.Z. Cyclic Thermal Shock Resistance of TiC/Ni3Al FGMs. Compos. Part B Eng. 1997, 28, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Zhang, N.; Zhuo, L.; Qin, P.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Z. “MOF-Cloth” Formed via Supramolecular Assembly of NH2-MIL-101(Cr) Crystals on Dopamine Modified Polyimide Fiber for High Temperature Fume Paper-Based Filter. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 168, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorovičová, E.; Pospíšil, J.; Sitek, T. The Bulk Density and Cohesion of Submicron Particles Emitted by a Residential Boiler When Burning Solid Fuels. Fire 2023, 6, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 29463-3:2011 - High-Efficiency Filters and Filter Media for Removing Particles in Air — Part 3: Testing Flat Sheet Filter Media. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/51837.html (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Wei, W.; Han, Y.; Chen, J.; Han, F.; Zou, D.; Zhang, F.; Zhong, Z.; Xing, W. Fabrication of Robust SiC Ceramic Membrane Filter with Optimized Flap for Industrial Coal-Fired Flue Gas Filtration. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 302, 122075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impossible, W. Standard Hot Gas Cleaning Filter Available online: https://www.boedon.com/pdf/hot-gas-filtration-filter-elements-catalogue.pdf.

- Metal Hot Gas Filter Offers Great Resistant to High Temperatures. Available online: https://www.boedon.com/products/industrial-filtration/hot-gas/index.html (accessed on 3 August 2024).

- Porous Metal Filter Elements Available online: https://mottcorp.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Filter-Element-Overview.pdf.

- Industrial High-Temp Gas Filter | Saifilter Hot Gas System. Available online: https://www.saifilter.com/products/hot-gas-industry-filter/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- High Temperature Gas Filtration System Available Media and Materials Sintered Metal Fibre Sintered Metal Mesh Available online: https://www.saifilter.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Saifilter-Hot-Gas-Filters-Brochure.pdf.

- Stainless Steel Filter Media Available online: https://dorstener-drahtwerke.de/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Marktinfo-Filtermedia-Englisch.pdf.

- DaZhou Metal Mesh Industrial|Iron Wire|Filtration Metal Mesh. Available online: https://www.dzmetalmesh.com/ (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Filter Elements Available online: https://alloyfilter.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/ALL-FILTER-ELEMENTS-FROM-FILTALLOY.pdf.

- Filters Manufacturer in India | Kumar Filters. Available online: https://kumarfilter.com/index.php (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Deeraj, B.D.; Jayan, J.S.; Raman, A.; Asok, A.; Paul, R.; Saritha, A.; Joseph, K. A Comprehensive Review of Recent Developments in Metal-Organic Framework/Polymer Composites and Their Applications. Surfaces and Interfaces 2023, 43, 103574. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Yue, F.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, C.; Shi, M.; Ma, Y.; Berrettoni, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H. Zr-MOF/MXene Composite for Enhanced Photothermal Catalytic CO2 Reduction in Atmospheric and Industrial Flue Gas Streams. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 100274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.-G.; Bigdeli, F.; Panjehpour, A.; Larimi, A.; Morsali, A.; Dhakshinamoorthy, A.; Garcia, H. Metal Organic Framework Composites for Reduction of CO2. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 493, 215257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omarova, A.; Baimatova, N.; Kazemian, H. MOF-199-Based Coatings as SPME Fiber for Measurement of Volatile Organic Compounds in Air Samples: Optimization of in Situ Deposition Parameters. Microchem. J. 2023, 185, 108263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Filter type | Dimensions (mm) / Filtration area (cm2) | Combustion source (product) | Production method | Mesh or wire size / Fiber or wire diameter (µm) / Porosity (%) | Flue gas temperature (°C) |

Particle size (µm) |

Flow rate (Airflow) (m3/h) | Airflow Velocity (m/s) |

Pressure drop (Pa) |

Filtration efficiency (%) / Dust concentration (mg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

METAL MESH Qu et al. [62] Stainless steel weaved bag (SSWB) |

8200 cm2 130 mm (Diameter) 2000 mm (Length) |

Dust-laden flue gas (SiO2 and Al2O3) | Plain Dutch weave method | 800 ± 10 | 5.71 (Average) |

1560 ± 5 |

0.03 (Superficial) |

2820–2910 (<3000) (Before cleaning) |

Above 99.9 with 1440 h <8.3 (Outlet) 17000 ± 300 (Inlet) |

|

|

METAL MESH Schott et al. [10] Stainless steel mesh |

800 cm2 (One candle) 1200 cm2 (Total) |

Dust-laden flue gas | Weave – braid, twill, linen | 25, 50, 135 (Mesh size) 61.3, 34.6, 36 (Porosity) |

700 (Max.) |

64.1 ± 4.7 | 0.9 ± 0.1 |

1200 ± 10 (Max.) 200-400 (Residual) |

90 (Max.) <20 (Outlet) (for 25 and 50 mesh size) 83 (Max. regenerability efficiency) |

|

|

METAL COMPOSITE Yang et al. [5] Carbon nanowires growth on a 304 Stainless steel mesh |

Incense coil | In situ vapor growth method | 30 × 30 (Openings of the mesh) 10–100 (The length of nanowires) ~0.12 (Diameter of the nanowires) |

PM2.5 |

0.002432 |

0.1 |

200–300 (Initial) |

96.1 (After four cycles >95) >2 (Inlet) |

||

| PM10 | ||||||||||

|

METAL COMPOSITE Xie et al. [56] Metal web with PTFE |

0.37 mm (Metal web) 0.11 mm (PTFE membrane) (Thickness) 230 mm (Length) 85 mm (Wide) |

Dust (SiO2) | Hot-pressing process | 1.71 (Metal web fiber) 0.38 (PTFE fiber) |

260 | 2.61 (Median diameter) PM2.5 = 46.52 % |

0.1023 (Face) |

425 (Residual) |

99.32 0.532 (Outlet, average) 130 (Inlet) |

|

|

METAL COMPOSITE Gui et al. [57] FeAl/Al2O3 PCMM |

7.065 cm2 (Effective) 5 mm (Thickness) |

Incense | Powder metallurgy method via the combination of mutual diffusion and chemical reaction | 2.34 (Average pore diameter) 1–3 (Bigger pore diameter) 0–1 (Smaller pore diameter) 47.6 (Porosity) |

600 | PM2.5 | 0.12 | 3000 |

96.2 |

|

| PM2.5–10 | 99.3 | |||||||||

|

MOF-POLYMER COMPOSITES Xie et al. [59] PI@PDA@MOF fibers |

100 cm2 (Effective) |

NaCl particles (0.3–10 µm) |

8 (Average diameter of PI Fiber) 5–6 mm (Length of PI fibers) |

260 | PM0.3 | 0.032 | 57.5 | 93.05 ± 1.27 | ||

|

MOF-POLYMER COMPOSITES Xie et al. [9] PI-POSS@ZIF |

100 cm2 (Effective) |

NaCl particles (0.3–10 µm) |

Electrospinning and hydrogen bonding self-assembly | 0.266 ± 0.035 (PI fiber diameter) |

280 | PM0.3 |

0.032 |

49.21 | 99.28 | |

|

MOF-POLYMER COMPOSITES Zhu et al. [7] ZIF-8/PI NFA |

5 mm (Thickness) 50 cm2 (Effective) |

Incense | Electrospinning, imidization, etc. | 300 | PM2.5-10 | 0.053 (Face) |

88.5 | 99.3 | ||

| PM2.5 | 99.5 | |||||||||

|

MOF-POLYMER COMPOSITES Dong et al. [39] SH-Mp-PET (Ti, Zn, Cu) |

0.001–0.002 (Pore size of MOF) |

Up to 200 (Thermal stability) |

PM0.3 | 53 (Ti) |

97.97 ± 0.81 | |||||

| 49 (Zn) |

97.76 ± 0.48 | |||||||||

| 50 (Cu) |

97.83 ± 0.54 | |||||||||

|

MOF-POLYMER COMPOSITES Wei et al. [1] PI/CD-MOF nanofiber filter |

100 cm2 (Effective) |

NaCl particles (0.3–2.5 µm) |

Co-electrospinning method | 1000 (Metal mesh) 0.680 ± 0.020 (PI fiber diameter) |

<300 | PM0.3 | 0.032 | 136 | 99.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).