Submitted:

30 October 2025

Posted:

31 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

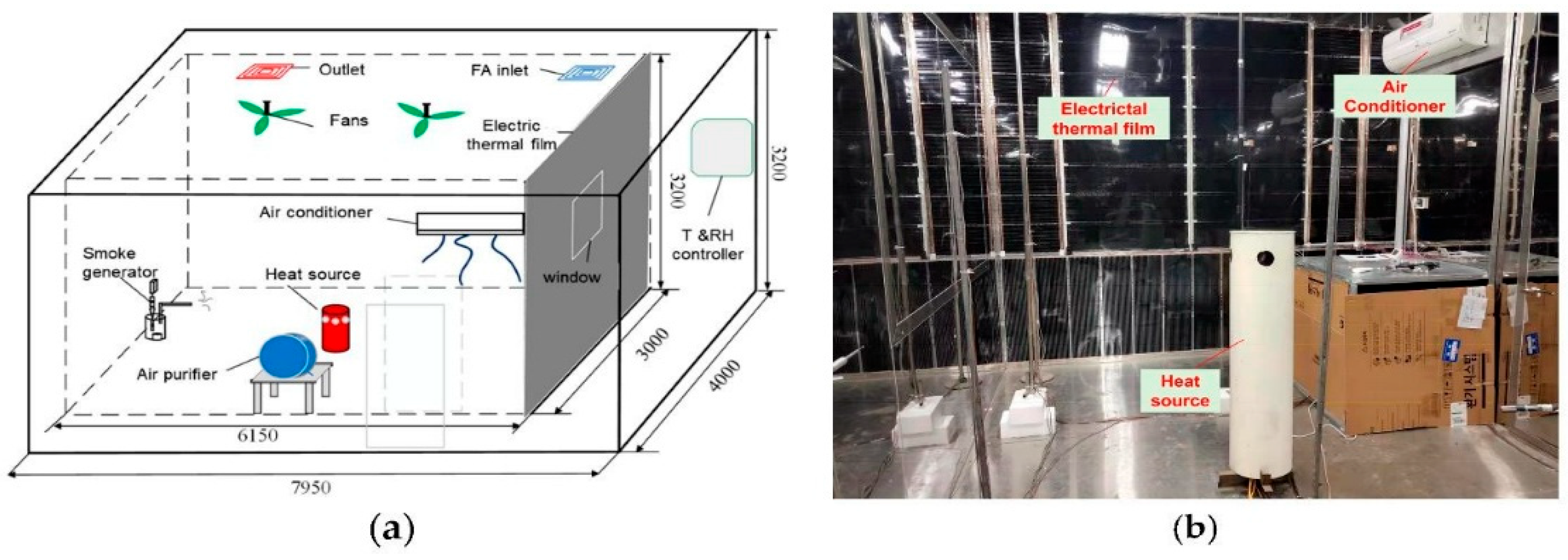

2. Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Particulate Matter PM 2.5 and PM 10 in Indoor Environments

3.1.1. Air Pollution Concentration and Its Impact on Human Health

3.1.2. Air Pollution Concentration in Residential Buildings

- -

- frequent use of an air fresheners (6-7 days a week) (p = 0.0016),

- -

- living near a gas station (< 0.5 miles) (p = 0.01),

- -

- season - lower PM 2.5 in summer than in winter (p = 0.03).

- -

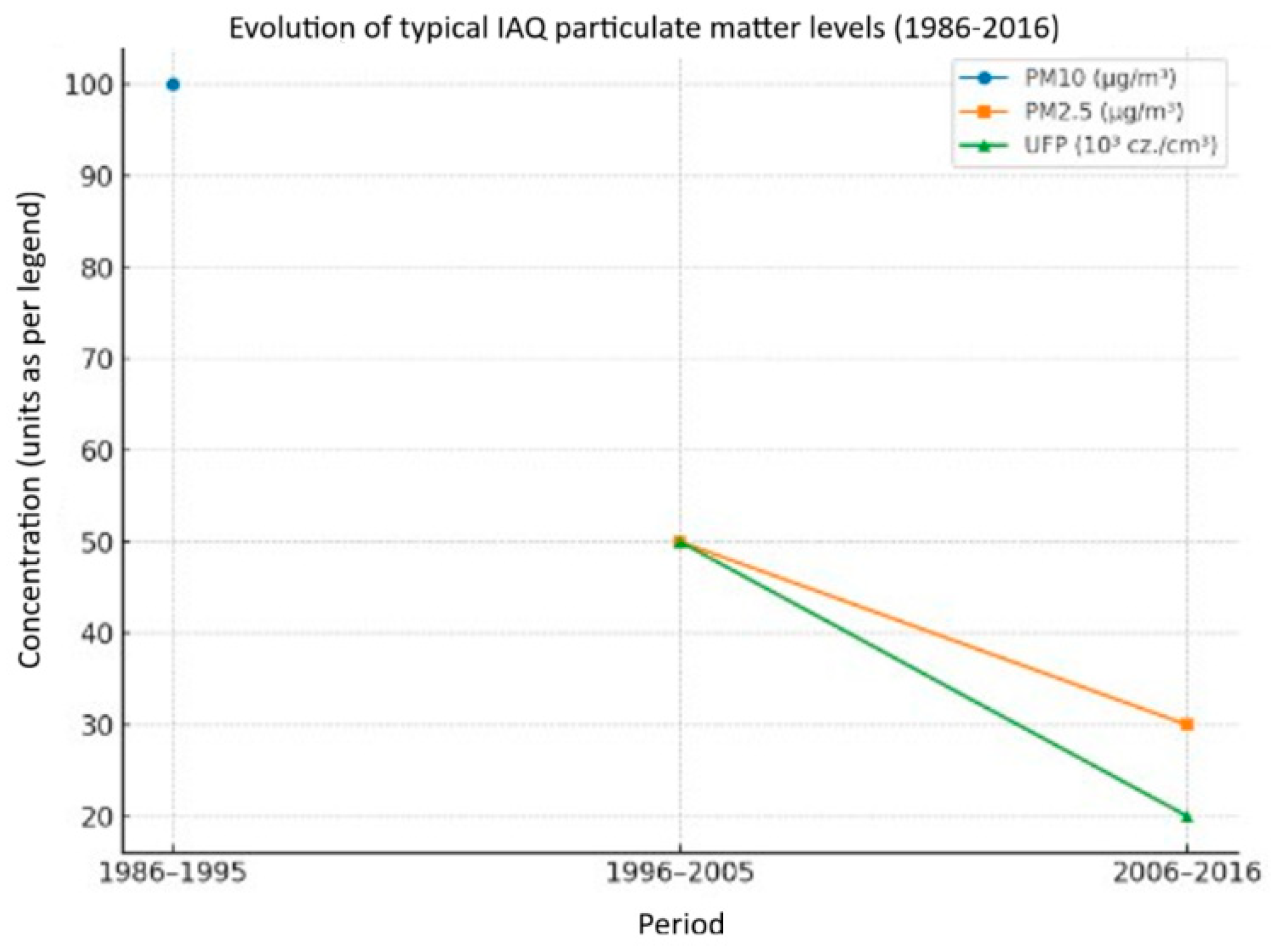

- between 1986 and 1995, research focused mainly on PM 10,

- -

- from the mid-1990s, the emphasis shifted to PM 2.5 (20–80 µg·m-3) and ultrafine particles (103–105 particles·cm-3),

- -

- after 2006, the studies also included secondary organic aerosols; typical levels of PM 2.5 decreased (10–50 µg·m-3), and UFP stabilised at 103–104 particles·cm-3.

3.1.3. Air Pollution Concentration in Public-Use Buildings

- -

- SU-1 (Sikornik district - urban area 1),

- -

- PU-2 (Pszczyńska Street - urban area 2) - kindergarten located 50 m from a street,

- -

- R-3 (village of Przezchlebie - rural area 3),

- -

- SR-4 (village of Świętoszowice - rural area 4) - kindergarten located 50 m from the A1 highway.

- -

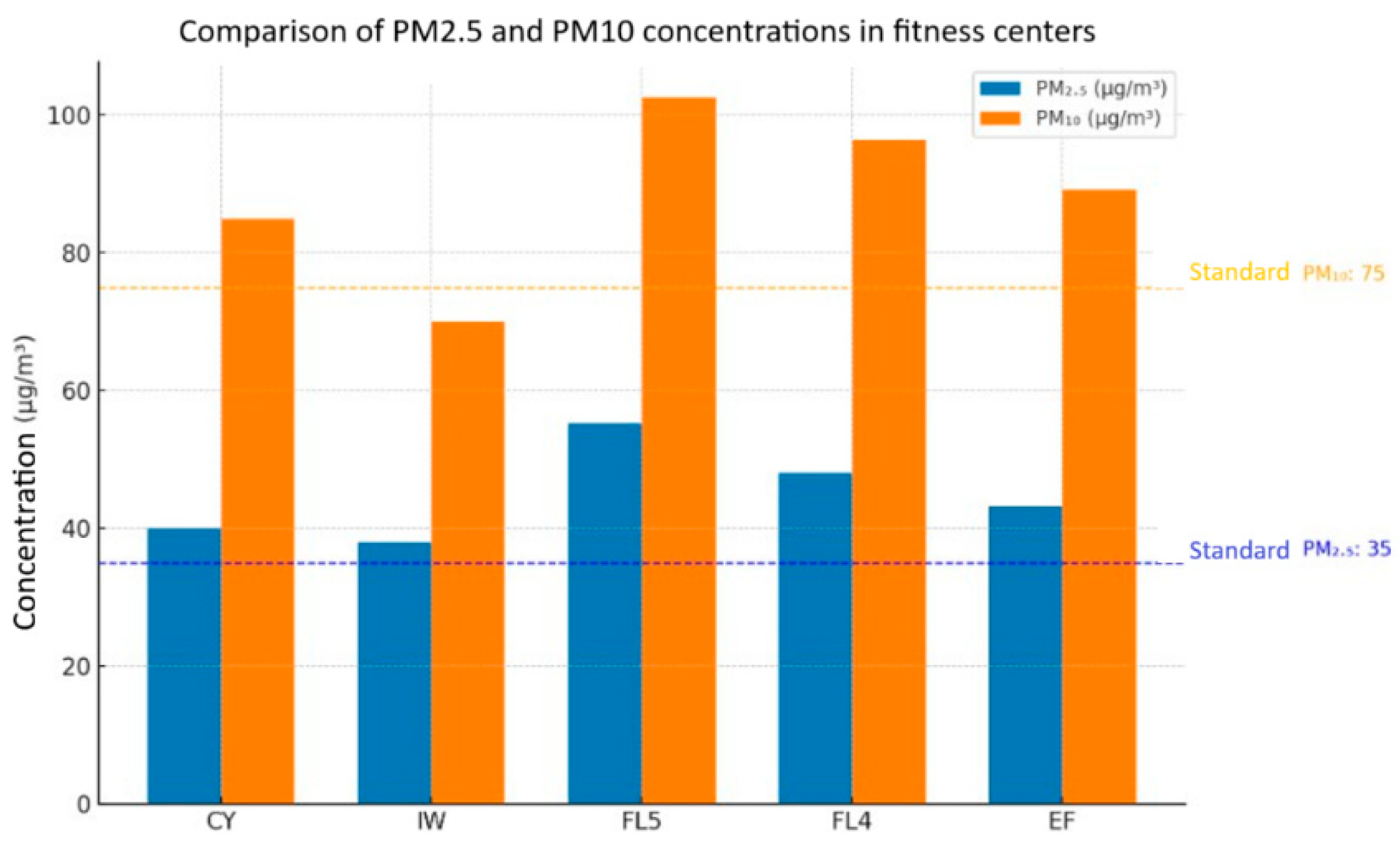

- PM 2.5 concentrations exceed the standard limit (35 µg·m-3) in all fitness centres, particularly in FL5 and FL4.

- -

- PM 10 concentrations also exceed the allowed level (75 µg·m-3) in most facilities, especially in FL5 (102.6 µg·m-3) and FL4 (96.4 µg·m-3).

- -

- hall, summer: PM 1 = 29 µg·m-3, PM 2.5 = 30 µg·m-3, PM 4 = 31 µg·m-3, PM 10 = 18 µg·m-3, TSP = 40 µg·m-3,

- -

- outdoor area, summer: PM 1 = 22 µg·m-3, PM 2.5 = 23 µg·m-3, PM 4 = 24 µg·m-3, PM 10 = 13 µg·m-3, TSP = 27 µg·m-3,

- -

- hall, winter: PM 1 = 38 µg·m-3, PM 2.5 = 39 µg·m-3, PM 4 = 40 µg·m-3, PM 10 = 33 µg·m-3, TSP = 45 µg·m-3,

- -

- outdoor area, winter: PM 1 = 56 µg·m-3, PM 2.5 = 52 µg·m-3, PM 4 = 52 µg·m-3, PM 10 = 31 µg·m-3, TSP = 29 µg·m-3.

- -

- above the fourth floor, the concentrations decreased by approximately 0.11 µg·m-3 per metre,

- -

- indoor PM 2.5 concentrations increased slightly with height: on average by +0.02 µg·m-3 per metre, from 5.3 µg·m-3 (1st floor) to 5.8 µg·m-3 (9th floor),

- -

- outdoor concentrations varied throughout the day,

- -

- indoor concentrations remained relatively stable, except for an increase in the morning on the ninth floor between 9:00 am and 3:00 pm, probably related to office activities.

3.1.4. Concentration of Air Pollution in Historical Buildings

3.1.5. Concentration of Air Pollution in the Indoor Environment - Summary

3.2. Measurement Methodology for Airborne Particulate Matter PM 2.5 and PM 10

- -

- PCE-PQC 34 Air Quality Monitor – The device operates with advanced particle counting technology, enabling measurement of particulate concentrations with diameters of < 10 μm (PM 10), < 5 μm (PM 5), < 2.5 μm (PM 2.5) and < 1 μm (PM 1), with a flow rate of 2.83 l·min-1 and a detection range of 0.3 to 25 μm. Calibration is carried out according to technical specifications. Precise calculations of the mass of the particle in µg·m-3 are enabled by its high sensitivity and integrated mass concentration mode. To ensure high accuracy, the device uses a long-life laser diode.

- -

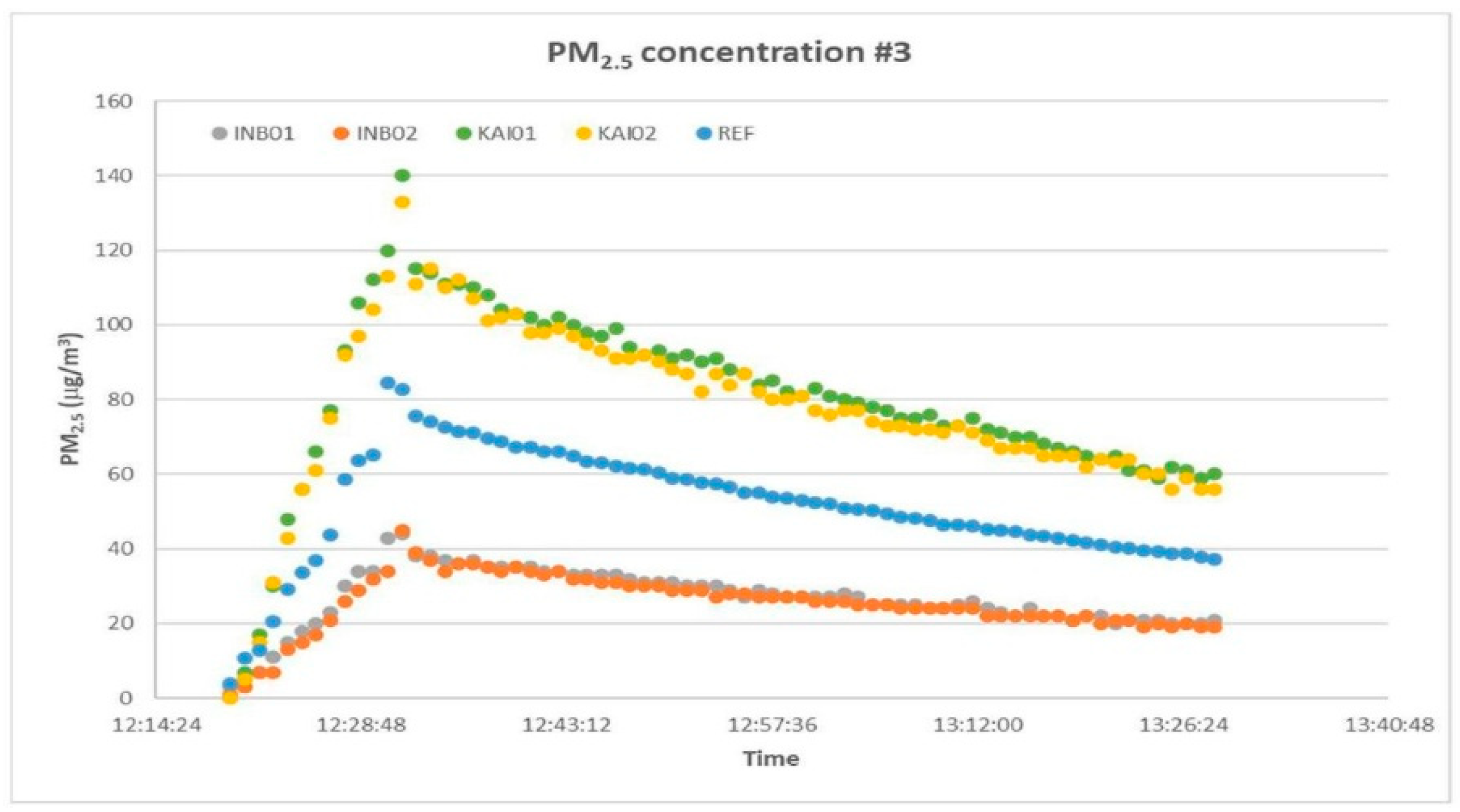

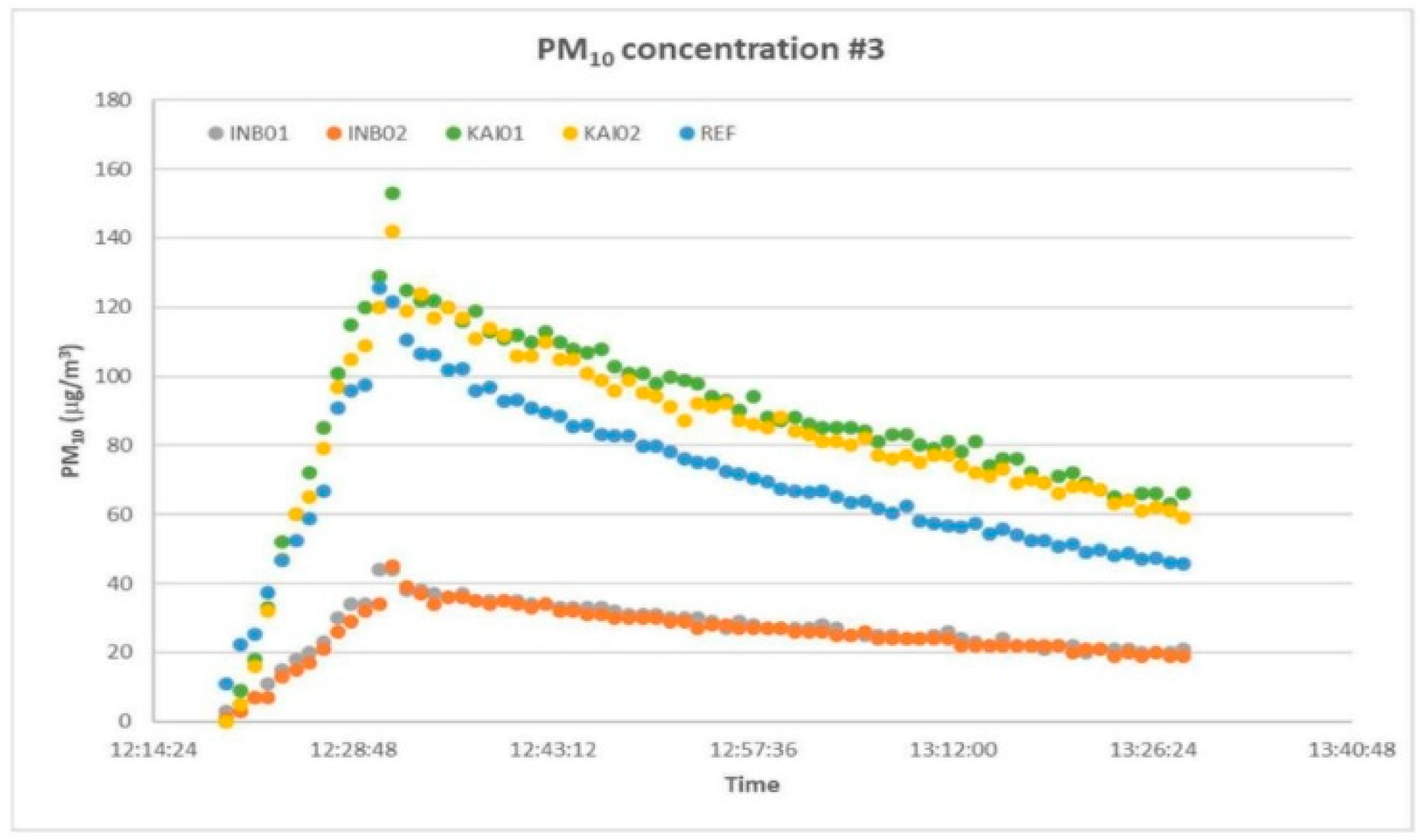

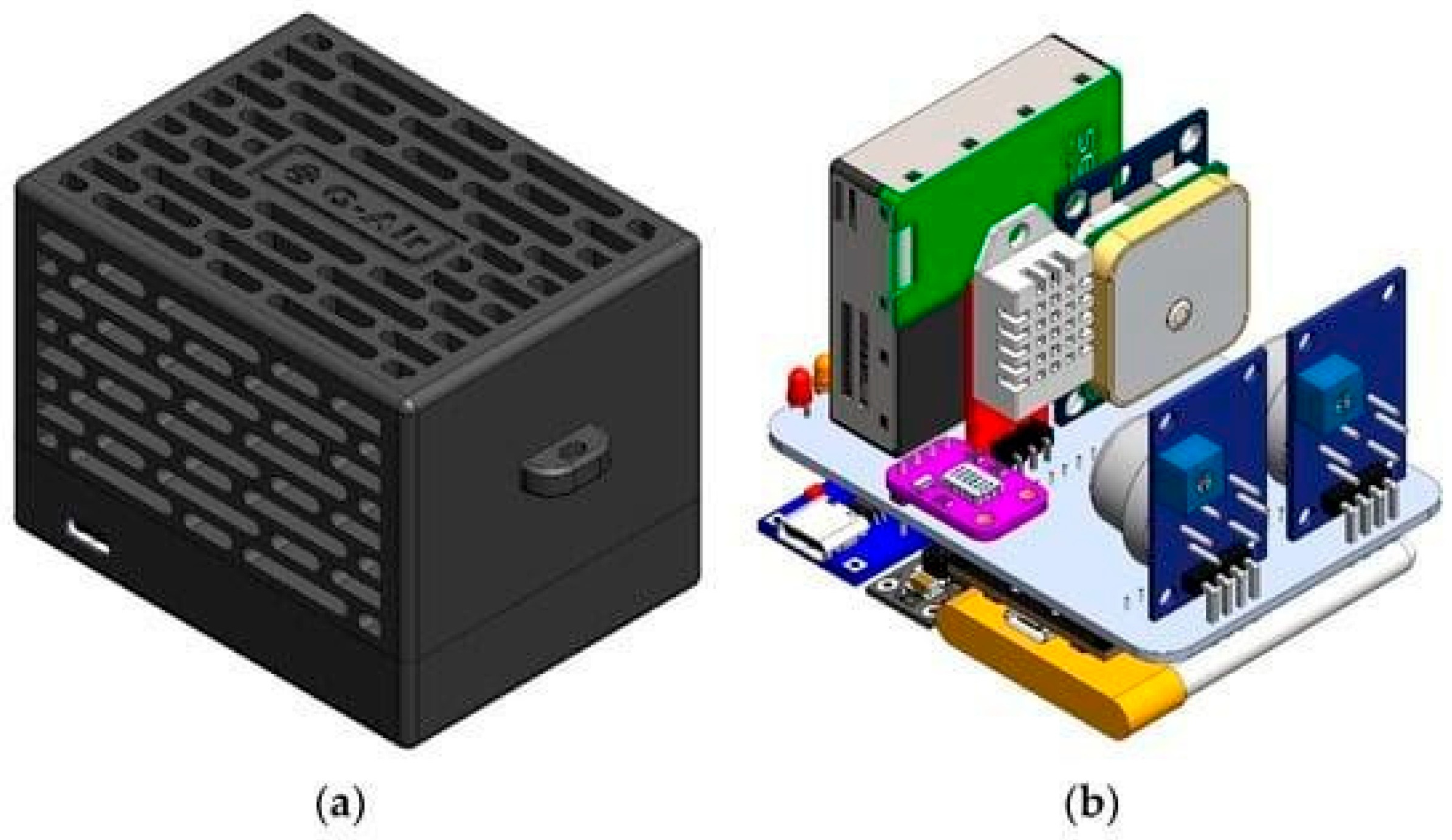

- inBiot (MICA) and Kaiterra devices – These sensors are commercially available and certified under RESET and WELL standards. They operate using laser scattering technology for particulate measurement and are based on proprietary algorithms. The technical parameters of these devices are presented in Table 5.

- -

- TSI SidePak AM510 – personal dust monitor (PM 2.5, PM 10).

- -

- TSI DustTrak II/DRX – portable dust monitor (PM 1, PM 2.5, PM 4, PM 10).

- -

- GrayWolf AdvancedSense Pro – multifunctional IAQ monitor (PM, VOCs, CO2, T, RH).

- -

- PCE-PQC 34 – reference particle counter (PM 1, PM 2.5, PM 4, PM 10).

- -

- PurpleAir – networked optical PM sensor (PM 1, PM 2.5, PM 10).

- -

- inBiot MICA – IAQ monitor (CO2, PM, VOCs, T, RH).

- -

- Kaiterra – IAQ monitor (CO2, PM 2.5, VOCs, T, RH).

- -

- Canāree A1 – personal IAQ sensor (PM, VOCs, CO2, T, RH).

- -

- Q-Air – IAQ device (PM, CO2, CH2O, VOCs, T, RH).

- -

- TSI DustTrak, SidePak, PCE-PQC 34, PurpleAir,

- -

- DustTrak/SidePak – controlled studies (schools, fitness centres),

- -

- PurpleAir – epidemiological and population studies.

3.3. Methods for Reducing the Concentration of Particulate Matter PM 2.5 and PM 10

- -

- ‘sham’ period (air purifiers operated but without filters),

- -

- period with LE filter (low-efficiency HEPA-type),

- -

- period with HE filter (true HEPA, high efficiency).

- -

- organic pollutants mainly from domestic activities such as cooking (45 %),

- -

- resuspension and infiltration of pollutants related to traffic and waste combustion products (14 %),

- -

- secondary aerosols (13 %),

- -

- tobacco smoke (7 %),

- -

- urban dust (2 %),

- -

- unidentified sources (19 %).

- -

- introduction of forced ventilation,

- -

- restoration of the air exchange system,

- -

- cleaning of air conditioning filters,

- -

- installation of air diffusers in the ceiling equipped with air filters,

- -

- removal of sealed office grilles,

- -

- replacement of heavy carpets with better ventilated flooring materials.

- -

- LL – low outdoor and low indoor levels,

- -

- HL – high outdoor and low indoor levels,

- -

- LH – low outdoor and high indoor levels,

- -

- HH – high levels both outdoors and indoors.

- -

- the optimal placement of air purifiers within office spaces,

- -

- the integration of air purifiers with existing ventilation systems,

- -

- and adjustment of operating parameters to the specific conditions of office environments (including the number of occupants, the type of furniture, and the characteristics of airflow).

4. Conclusions

References

- Chen J., Hoek G. Long-term exposure to PM and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environment International, 2020, 143, 105974. [CrossRef]

- Wesseling J., de Ruiter H., Blokhuis C., Drukker D., Weijers E., Volten H., Vonk J., Gast L., Voogt M., Zandveld P., van Ratingen S., Tielemans E. Development and implementation of a platform for public information on air quality, sensor measurements, and citizen science, Atmosphere, 2019, 10(8), 445. [CrossRef]

- Aguado A., Rodríguez-Sufuentes S., Verdugo F.; Rodríguez-López A., Figols M., Dalheimer J., Gómez-López A., González-Colom R., Badyda A., Fermoso J. Verification and usability of indoor air quality monitoring tools in the framework of health-related studies, Air, 2025, 3(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Leikauf G.D., Kim S.-H., Jang A.-S. Mechanisms of ultrafine particle-induced respiratory health effects, Experimental and Molecular Medicine, 2020, 52(3), pp.: 329–337. [CrossRef]

- Nair A.N., Anand P., George A., Mondal N. A review of strategies and their effectiveness in reducing indoor airborne transmission and improving indoor air quality, Environmental Research, 2022, 216, 113579. [CrossRef]

- Chen R., Zhao A., Chen H., Zhao Z., Cai J., Wang C., Yang C., Li H., Xu X., Ha S., Li T., Kan H. Cardiopulmonary Benefits of Reducing Indoor Particles of Outdoor Origin: A Randomized, Double-Blind Crossover Trial of Air Purifiers, Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2015, 65(21), pp.: 2279–2287. [CrossRef]

- Allen R.W., Carlsten C., Karlen B., Leckie S., van Eeden S., Vedal S., Wong I., Brauer M. An air filter itervention study of endothelial function among healthy adults in a woodsmoke-impacted community, American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 2011, 183(9), pp.: 1222–1230. [CrossRef]

- Bräuner E.V., Forchhammer L., Møller P., Barregard L. Gunnarsen L., Afshari A., Wåhlin P., Glasius M., Dragsted L.O., Basu, S., Raaschou-Nielsen O., Loft S. Indoor particles affect vascular function in the aged. An air filtration-based intervention study, American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 2008, 177(4), pp.: 419–425. [CrossRef]

- Haryanto B. Air Pollution—A Comprehensive Perspective, Ed.; IntechOpen, 2012, London, UK.

- Thompson McK., Castorina R., Chen W., Moore D., Peerless K., Hurley S. Effectiveness of air filtration in reducing PM2.5 exposures at a school in a community heavily impacted by air pollution, Atmosphere, 2024, 15(8), 901. [CrossRef]

- Jia L., Ge J., Wang Z., Jin W., Wang C., Dong Z., Wang C., Wang R. Synergistic impact on indoor air quality: The combined use of air conditioners, air purifiers, and fresh air systems, Buildings, 2024, 14(6), 1562. [CrossRef]

- Klaver Z.M., Crane R.C, Ziemba R.A., Bard R.L., Adar S.A., Brook R.D., Morishita M. Reduction of outdoor and indoor PM2.5 source contributions via portable air filtration systems in a senior residential facility in Detroit, Michigan, Toxics, 2023, 11(12), 1019. [CrossRef]

- Lee D., Kim Y., Hong K.-J., LeeG., Kim H.-J., Shin D., Han B. Strategies for effective management of indoor air quality in a kindergarten: CO2 and fine particulate matter concentrations, Toxics, 2023, 11(11), 931. [CrossRef]

- Sung W.-P., Chen T.-Y., Liu C.-H. Strategy for improving the indoor environment of office spaces in subtropical cities, Buildings, 2022, 12(4), 412. [CrossRef]

- Kim J.-H., Yeo M.-S. Effect of flow rate and filter efficiency on indoor PM2.5 in ventilation and filtration control, Atmosphere, 2020, 11(10), 1061. [CrossRef]

- Matz C.J., Stieb D.M., Davis K., Egyed M., Rose A., Chou B., Brion O. Effects of age, season, gender and urban-rural status on time-activity: Canadian human activity pattern survey 2 (CHAPS 2). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2014, 11(2), pp.: 2108–2124. [CrossRef]

- Report of Indoor Air Quality, United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2025.

- Jiang X.Q., Mei X.D., Feng D. Air pollution and chronic airway diseases: What should people know and do? Journal of Thoracic Disease, 2016, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Xydi I., Saharidis G., Kalantzis G., Pantazopoulos I., Gourgoulianis K.I., Kotsiou O.S. Assessing the impact of spatial and temporal variability in fine particulate matter pollution on respiratory health outcomes in asthma and COPD patients, Journal of Personalized Medicine, 2024, 14(8), 833. [CrossRef]

- Hart J.E., Grady S.T., Laden F., Coull B.A., Koutrakis P., Schwartz J.D., Moy M.L., Garshick E. Effects of indoor and ambient black carbon and PM2.5 on pulmonary function among individuals with COPD, Environmental Health Perspectives, 2018, 126(12). [CrossRef]

- de Hartog J.J., Ayres J.G., Karakatsani A., Analitis A., Brink H.T., Hameri K., Harrison R., Katsouyanni K., Kotronarou A., Kavouras I., Meddings C., Pekkanen J., Hoek G. Lung function and indicators of exposure to indoor and outdoor particulate matter among asthma and COPD patients. Occuppational and Environmental Medicine, 2010, 67(1). [CrossRef]

- Hsu S.O., Ito K., Lippmann M. Effects of thoracic and fine PM and their components on heart rate and pulmonary function in COPD patients. Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology, 2011, 21, pp.: 464–472. [CrossRef]

- Cortez-Lugo M., Ramírez-Aguilar M., Pérez-Padilla R., Sansores-Martínez R., Ramírez-Venegas A., Barraza-Villarreal A. Effect of personal exposure to PM2.5 on respiratory health in a Mexican panel of patients with COPD, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2015, 12(9), pp.: 10635–10647. [CrossRef]

- Li Z., Wen Q., Zhang R. Sources, health effects and control strategies of indoor fine particulate matter (PM2.5): A review. Science of the Total Environment, 2017, 586, pp.: 610–622. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L., Ou C., Magana-Arachchi D., Vithanage M., Vanka K.S., Palanisami T., Masakorala K., Wijesekara H., Yan Y., Bolan N., Kirkham M.B. Indoor particulate matter in urban households: sources, pathways, characteristics, health effects, and exposure mitigation, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2021, 18(21), 11055. [CrossRef]

- Seguel J.M., Merrill R., Seguel D., Campagna A.C. Indoor air quality, American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 2016, 11(4), pp.: 284–295. [CrossRef]

- Park Ś., Seo J., Lee Ś. Distribution characteristics of indoor PM2.5 concentration based on the water type and humidification method, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2020, 17(22), 8638. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q., Ao R., Chen H., Li J., Wei L., Wang Z. Characteristics of PM2.5 and CO2 concentrations in typical functional areas of a University campus in Beijing based on low-cost sensor monitoring, Atmosphere 2024, 15(9), 1044. [CrossRef]

- Kadiri K., Turcotte D., Gore R., Bello A., Woskie S.R. Determinants of indoor NO2 and PM2.5 concentration in senior housing with gas stoves, Toxic, 2024, 12(12), 901. [CrossRef]

- Tham K.W. Indoor air quality and its effects on humans—A review of challenges and developments in the last 30 years, Energy and Buildings, 2016, 130, pp.: 637–650. [CrossRef]

- Šedivá T., Štefánik D. The Seasonality of PM and NO2 Concentrations in Slovakia and a Comparison with Chemical-Transport Model. 2024, 15(10), 1203. [CrossRef]

- Järvi K., Vornanen-Winqvist C., Mikkola R., Kurnitski J., Salonen H. Online questionnaire as a tool to assess symptoms and perceived indoor air quality in a school environment, Atmosphere, 2018, 9(7), 270. [CrossRef]

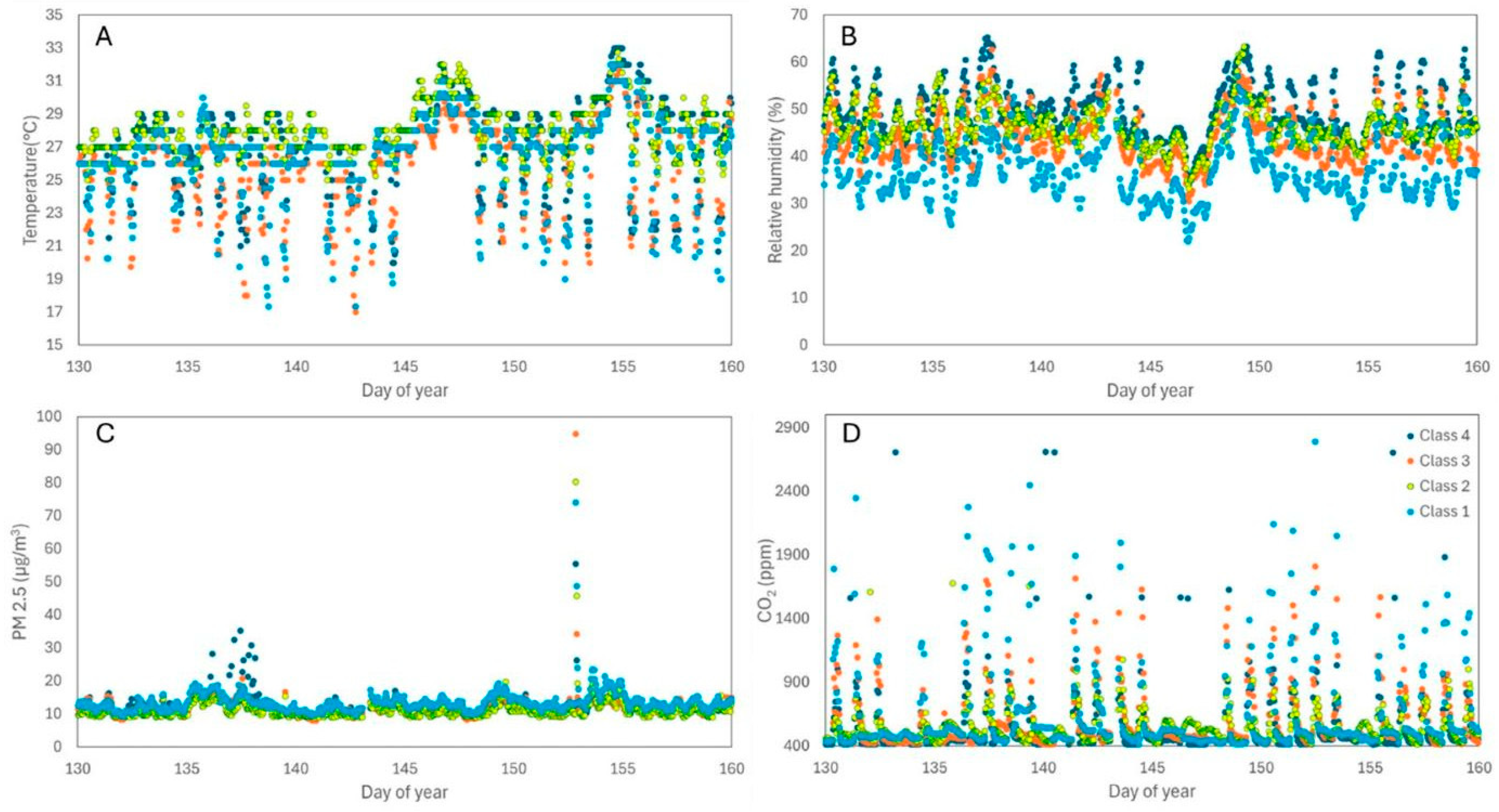

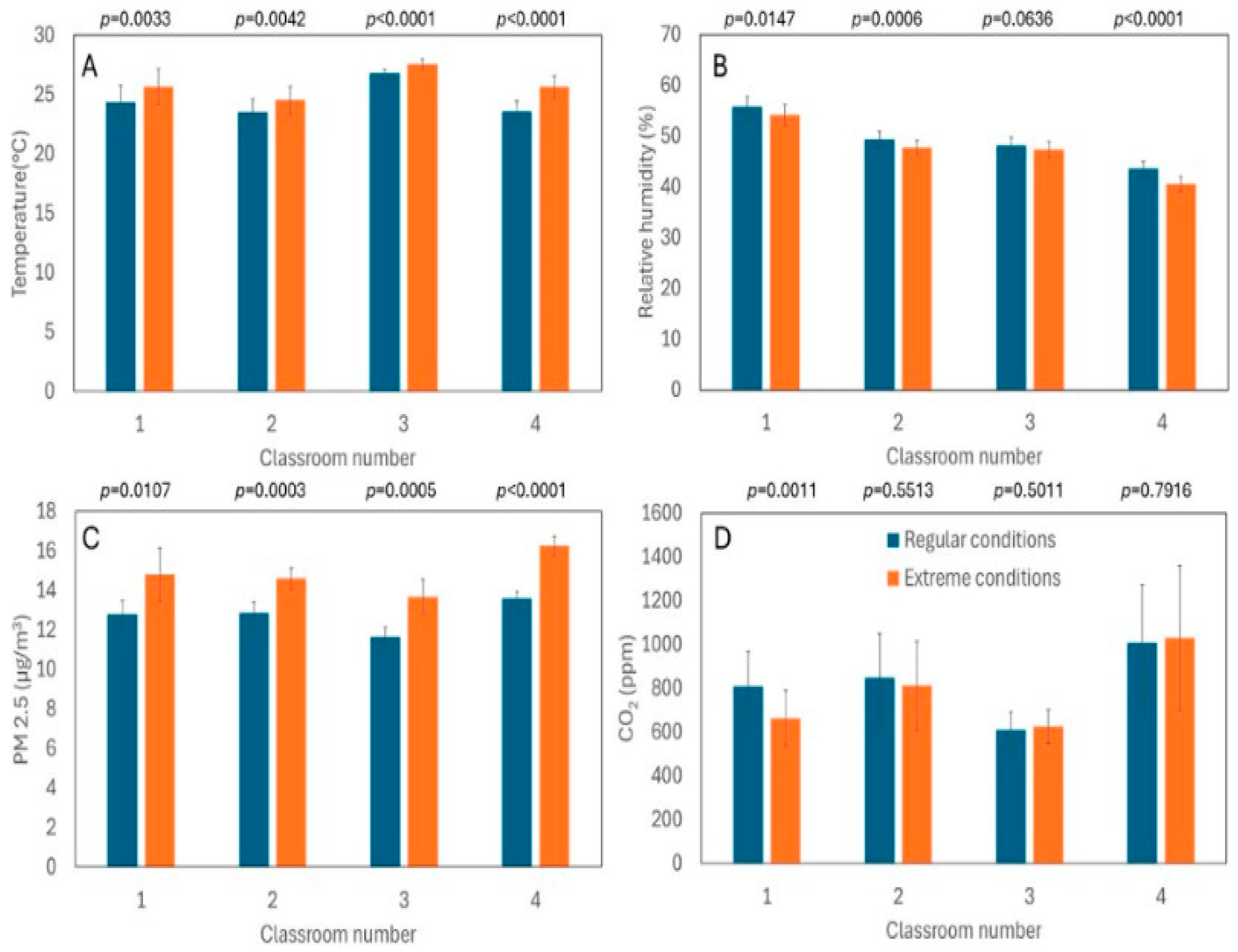

- Kochavi S.A., Kira O., Gal E. Real-time monitoring of environmental parameters in schools to improve indoor resilience under extreme events, Smart Cities 2025, 8(1), 7. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, WHO global air quality guidelines: particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxid, 2021.

- Canha N., Correia C., Mendez S., Gamelas C.A., Felizardo M. Monitoring indoor air quality in classrooms using low-cost sensors: Does the perception of teachers match reality?, Atmosphere 2024, 15(12), 1450. [CrossRef]

- Portaria n.o 138-G/2021. Portaria n.o 138-G/2021—Requisitos Para a Avaliação Da Qualidade Do Ar Interior Nos Edifícios de Comércio e Serviços. Diário República, 2021, 1, 128.

- Barmparesos N., Saraga D., Karavoltsos S., Maggos T., Assimakopoulos V.D. Sakellari A., Bairachtari K., Assimakopoulos M.N. Chemical composition and source apportionment of PM10 in a green-roof primary school building, Applied Sciences, 2020, 10(23), 8464. [CrossRef]

- Mainka A., Zajusz-Zubek E. Indoor air quality in urban and rural preschools in upper Silesia, Poland: Particulate matter and carbon dioxide, Enviromental Research and Public Helth, 2015, 12(7), pp.: 7697-7711. [CrossRef]

- PN-EN 12341:2024-01 Ambient air - Standard gravimetric measurement method for the determination of the PM 10 or PM 2.5 mass concentration of suspended particulate matter.

- Moldovan F., Moldovan Ł. Indoor air quality in an orthopedic hospital from Romania, Toxic; 2024, 12(11), 815. [CrossRef]

- Chen R., Zhang X., Wang P., Xie K., Jian J., Zhang Y., Zhang J., Yuan Y., Na P., Yi, M., Xu J. Transparent thermoplastic polyurethane air filters for efficient electrostatic capture of particulate matter pollutants, Nanotechnology, 2019, 30, 015703. [CrossRef]

- Kuo P-Y., Chen C.-Y., Wu T.-Y. Influence of interior decorations on indoor air quality in fitness centers, Engineering Proceedings, 2023, 55(1), 56. [CrossRef]

- Bralewska K., Rogula-Kozłowska W., Bralewski A. Size-segregated particulate matter in a selected sports facility in Poland, Sustainability, 2019, 11(24), 6911. [CrossRef]

- Chang L.T.-C., Leys J., Heidenreich S., Koen T. Determining aerosol type using a multichannel DustTrak DRX, Journal of Aerosol Science, 2018, 126, pp.: 68–84. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Exposure Factors Handbook, EPA, Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- Saidin H., Razak A.A., Mohamad M.F., Ul-Saufie A.Z., Zaki S.A., Othman N. Hazard evaluation of indoor air quality in bank offices, Buildings, 2023, 13(3), 798. [CrossRef]

- Wallace L. Cracking the code-Matching a proprietary algorithm for a low-cost sensor measuring PM1 and PM2.5. Science of Total Environment, 2023, 893, 164874. [CrossRef]

- https://tsi.com/discontinued-products/sidepak-personal-aerosol-monitor-am510.

- https://tsi.com/products/aerosol-and-dust-monitors/aerosol-and-dust-monitors/dusttrak%E2%84%A2-ii-aerosol-monitor-8532.

- Wenner M.M, Ries-Roncalli A., Whalen M.C.R., Jing P. The relationship between indoor and outdoor fine particulate matter in a high-rise building in Chicago monitored by PurpleAir sensors, Sensors, 2024, 24(8), 2493. [CrossRef]

- Magi B.I., Cupini C., Francis J., Green M., Hauser C. Evaluation of PM2.5 measured in an urban setting using a low-cost optical particle counter and a Federal Equivalent Method Beta Attenuation Monitor. Aerosol Science of Technology, 2020, 54, pp.: 147–159. [CrossRef]

- Malings C., Tanzer R., Hauryliuk A., Saha P.K., Robinson A.L., Presto A.A., Subramanian R. Fine particle mass monitoring with low-cost sensors: Corrections and long-term performance evaluation, Aerosol Science and Technology, 2020, 54, pp.: 160–174. [CrossRef]

- Mehadi A., Moosmüller H., Campbell D.E., Ham W., Schweizer D., Tarnay L., Hunter J. Laboratory and field evaluation of real-time and near real-time PM2.5 smoke monitors. Journal of the Air and Waste Management Association, 2020, 70(2), pp.: 158–179. [CrossRef]

- Barkjohn K.K., Gantt B., Clements A.L. Development and application of a United States wide correction for PM2.5 data collected with the PurpleAir sensor, Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 2021, 14(6), pp.: 4617–4637. [CrossRef]

- Wu J., Weng J., Xia B., Zhao Y., Song Q. The synergistic effect of PM2.5 and CO2 concentrations on occupant satisfaction and work productivity in a meeting room, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2021, 18(8), 4109. [CrossRef]

- Zhang G., Li W., Cheng Q., Zhou Z., Wang Q,, Peng Z. Source identification and characterization of indoor particulate matter in Potala Palace museum, Buildings, 2023, 13(9), 2138. [CrossRef]

- Daher N., Ruprecht A., Invernizzi G., de Marco C., Miller-Schulze J., Heo J.B., Shafer M.M., Schauer J.J., Sioutas C. Chemical characterization and source apportionment of fine and coarse particulate matter inside the refectory of Santa Maria Delle Grazie church, home of Leonardo Da Vinci’s “Last Supper”, Environmental Science and Technology, 2011, 45(24), pp.: 10344-10353. [CrossRef]

- Masková L., Smolík J., Travnickova T., Havlica J., Ondráčková L., Ondráček J. Contribution of visitors to the indoor PM in the National Library in Prague, Czech Republic, Aerosol Air Quality Research, 2016, 16, pp.; 1713–1721. [CrossRef]

- Wang L., Xiu G. Chen Y., Xu F., Wu L., Zhang D. Characterizing particulate pollutants in an Enclosed Museum in Shanghai, China, Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 2015, 15, pp.: 319–328. [CrossRef]

- de Bock L.A., van Grieken R.E., Camuffo D., Grime G.W. Microanalysis of museum aerosols to elucidate the soiling of paintings: Case of the Correr Museum, Venice, Italy, Environmental Science and Technology, 1996, 30(11), pp.: 3341– 3350. [CrossRef]

- Gysels K., Deutsch F., van Grieken R. Characterisation of particulate matter in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium, Atmospheric Environment, 2002, 36(25), pp.: 4103–4113. [CrossRef]

- Hu T., Lee S., Cao J., Chow J.C., Watson J.G., Ho K., Ho W., Rong B., An Z. Characterization of winter airborne particles at Emperor Qin’s Terra- cotta Museum, China, Science of the Total Environment, 2009, 407(20), pp.: 5319–5327. [CrossRef]

- Krupińska B., Worobiec A., Rotondo G.G., Novaković V., Kontozova V. Ro C.-U., van Grieken R., de Wael K. Assessment of the air quality (NO2, SO2, O3 and particulate matter) in the Plantin-Moretus Museum/Print Room in Antwerp, Belgium, in different seasons of the year, Microchemical Journal, 2012, 102, pp.: 49–53. [CrossRef]

- Nuñez J.G.C., Negrette O.A.C., Sáenz K.J.B., Sáenz C.G.D. Design and implementation of an indoor and outdoor air quality measurement device for the detection and monitoring of gases with hazardous health effects, Engineering Proceedings, 2025, 83(1), 13. [CrossRef]

- Abulude F.O., Gbotoso A.O., Ademilua S.O. Indoor air measurements with a low- cost air quality sensor: A preliminary report, Engineering Proceedings, 2023, 48(1), 31. [CrossRef]

- Wallace L., Ott W. Long-term indoor-outdoor PM2.5 measurements using PurpleAir Sensors: An improved method of calculating indoor-generated and outdoor-infiltrated contributions to potential indoor exposure, Sensors, 2023, 23(3), 1160. [CrossRef]

- https://graywolfsensing.com/iaq-graywolf-update/.

- https://www.reichelt.com/de/en/shop/product/pce-pqc_34eu_particle_counter-413117.

- https://www2.purpleair.com/products/purpleair-pa-ii?variant=40067691774049.

- https://www.inbiot.es.

- https://www.kaiterra.com.

- https://pierasystems.com.

- https://smartairfilters.com.

- https://www.mouser.pl/.

- https://metone.com.

- https://tsi.com/products/aerosol-and-dust-monitors/aerosol-and-dust-monitors/dusttrak%E2%84%A2-drx-aerosol-monitor-8533ep.

- Song Y.W., Kim S.E., Park J.-C. Indoor air pollutant (PM 10, CO2) reduction using a vortex exhaust ventilation system in a mock-up room, Buildings, 2025, 15(1), 144. [CrossRef]

- Lopes M.B., Kanama N., Poirier B., Guyot G., Ondarts M., Gonze E., Mendes N., A numerical and experimental study to compare different IAQ-based smart ventilation techniques, Buildings, 2024, 14(11), 3555. [CrossRef]

- https://www.iqair.com/.

- ASHRAE Standard 52.2, Performance and Recommendations.

- Chinese Standard GB/T 18801-2022, Air Cleaner.

- Lee M. An analysis on the concentration characteristics of PM2.5 in Seoul, Korea from 2005 to 2012. Asia-Pacific Journal of Atmospheric Science, 2014, 50(1), pp.: 585–594. [CrossRef]

- Martins N.R., da Graça G.C. Impact of outdoor PM2.5 on natural ventilation usability in California’s nondomestic buildings, Applied Energy, 2017, 189, pp.: 711–724. [CrossRef]

- Kim S.-G., Sung G., Yook S.-J., Kim M., Park D. Reducing PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations in a subway station by changing the diffuser arrangement, Toxics, 2022, 10(9), 537. [CrossRef]

- Lee H., Sung J.-H., Kim M., Kim Y.-S., Lee Y., Kim Y.-J., Han B., Kim H.-J. Development of electrostatic-precipitator-type air conditioner for reduction of fine particulate matter in subway. IEEE Transaction on Industry Applications, 2022, 58(3), pp.: 3992–3998. [CrossRef]

- Sun F., Zhang X., Xue T., Cheng P., Yu T. The performance testing and analysis of common new filter materials: A case of four filter materials, Materials, 2024, 17(12), 2802. [CrossRef]

- Li X., Wang X.X., Yue T.-T., Xu Y., Zhao M.-L., Yu M., Ramakrishna S., Long Y.-Z. Waterproof-breathable PTFE nano- and microfiber membrane as high efficiency PM2.5 filter, Polymers, 2019, 11(4), 590. [CrossRef]

- Pirhadi M., Mousavi A., Sioutas C. Evaluation of a high flow rate electrostatic precipitator (ESP) as a particulate matter (PM) collector for toxicity studies, Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 739, 140060. [CrossRef]

- Afshari A., Ekberg L., Forejt L., Mo J., Rahimi S., Siegel J., Chen W., Wargocki P., Zurami S., Zhang J. Electrostatic precipitators as an indoor air cleaner - A literature review, Sustainability, 2020, 12(21), 8774. [CrossRef]

- Sokolovskij E., Kilikevičius A., Chlebnikovas A., Matijošius J., Vainorius D. Innovative electrostatic precipitator solutions for efficient removal of fine particulate matter: Enhancing performance and energy efficiency, Machines, 2024, 12(11), 761. [CrossRef]

- Fan X., Wang Y., Zhong W.-H., Pan S. Hierarchically Structured All-Biomass Air Filters with High Filtration Efficiency and Low Air Pressure Drop Based on Pickering Emulsion. ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces, 2019, 11, issue 15, pp. 14266–14274. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Cruz Y., Bordón P., Pulido-Melián E., Saura-Cayuela T., Monzón M. Development of cellulose air filters for capturing fine and ultrafine particles through the valorization of banana cultivation biomass waste, Environments, 2024, 11(3), 50. [CrossRef]

- Lee H., Jun Z., Zahra Z. Phytoremediation: The sustainable strategy for improving indoor and outdoor air quality, Environments, 2021, 8(11), 118. [CrossRef]

- Falzone C., Jupsin H., el Jarroudi M., Romain A.-C. Advancing methodologies for investigating PM2.5 removal using green wall system, Plants, 2024, 13(12), 1633. [CrossRef]

| Location / Group |

PM 1 (µg·m-3) |

PM 2.5 (µg·m-3) |

PM 10 (µg·m-3) |

TSP (µg·m-3) |

| SU-1 (I) - older | 51.21 | 70.59 | 117.57 | 134.43 |

| SU-1 (II) - younger | 25.97 | 41.17 | 68.26 | 73.05 |

| PU-2 (I) | 78.89 | 106.06 | 149.81 | 163.81 |

| PU-2 (II) | 33.70 | 49.06 | 79.92 | 96.78 |

| PR-3 (I) | 83.64 | 102.05 | 135.93 | 147.54 |

| PR-3 (II) | 78.13 | 80.94 | 104.90 | 124.24 |

| SR-4 (I) | 102.11 | 125.69 | 166.12 | 184.24 |

| SR-4 (II) | 49.04 | 67.65 | 81.49 | 91.19 |

| Average - urban area | ~47.4 | ~66.7 | ~103.9 | ~117.0 |

| Average - rural area | ~78.2 | ~94.1 | ~122.1 | ~136.8 |

| Parameter | EPA Standard (Taiwan) |

Range of results in the fitness centers surveyed |

Exceedings |

| CO2 | ≤ 1000 ppm | 776 ppm | FL5 - 776 ppm |

| CH2O | ≤ 0,08 ppm | 0,20-1,36 ppm | All fitness centres |

| VOCs | ≤ 0,56 ppm | 0,6-1,21 ppm | FL4 |

| PM 2.5 | ≤ 35 µg·m-3 | 30,6-55,3 µg·m-3 | FL5 - 55,3 µg·m-3; FL4 - 48,1 µg·m-3; EF - 42,3 µg·m-3; |

| PM 10 | ≤ 75 µg·m-3 | 70,8-102,6 µg·m-3 | FL5 -102,6 µg·m-3; FL4 - 96,4 µg·m-3; EF -89,23 µg·m-3; |

| CO | ≤ 9 ppm | 0-2 ppm | No exceedances |

| O3 | ≤ 0,06 ppm | 0 ppm | No exceedances |

| Dependence | R (correlation coefficient) |

| Temperature - CH2O/CO2/VOCs | 0.3-0.7 (moderate) |

| Humidity - CH2O/CO2/VOCs | 0.3-0.7 (moderate) |

| CH2O - VOCs | > 0.7 (strong) |

| CO2 - VOCs | > 0.7 (strong) |

| CH2O - CO2 | > 0.7 (strong) |

| PM 2.5/ PM 10 - Temperature | 0.3-0.5 (moderate) |

| O3 - other parameters | 0 (no correlation) |

| Group |

Heating season (µg·d-1) |

Off season (µg·d-1) |

Heating season (µg·kg-1·d-1) |

Off season (µg·kg-1·d-1) |

| Students | 337 | 92 | 6,7 | 2 |

| Teachers | 377 | 118 | 5,3 | 1,6 |

| Sportsman | 473 | 145 | 6,6 | 1,8 |

| No. | City | Object | Type of study | Study results |

| 1. | China [56] |

Potala Palace Museum in Tibet | X-ray fluorescence analysis (XRF) | Studies have shown that the concentration of PM 1-10 particulate matter outdoors was lower than indoors. Airborne particles were classified into four categories: soil dust brought in by outdoor tourists, incense ash, human-induced pollution, and ores. |

| 2. | Milan [57] |

The refectory of the Church of Santa Maria Delle Grazie, which houses Leonardo da Vinci's "The Last Supper" | chemical mass balance model |

11.2 % of the particles came from gasoline cars, urban soil and wood smoke |

| 3. | Czech Republic [58] |

The Baroque Library Hall of the National Library in Prague | chemical mass balance model |

Tourists contribute to 35 % of indoor particulate matter |

| 4. | China [59] |

Museum in the Shanghai CBD | chemical mass balance model |

The coarse particles were mainly soot aggregates and minerals, while the fine particles were mainly soot aggregates. Ca, Si, Al, Na, C, O, S, and Mg were enriched in the coarse particles, and S was mainly enriched in the fine particles. |

| 5. | Italy [60] |

The Correa Museum in Piazza SAN Marco in Venice | electron probe X-ray microanalysis and scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray measurement (SEM-EDX) | Calcium-rich particles, aluminosilicates, and organic materials were the most dominant particles. Calcium-rich solid particles (from poor wall condition) |

| 6. | Belgium [61] |

Royal Art Gallery of Antwerp | chemical mass balance model |

In winter, construction activities were the main source of Ca- and Ca-Si-rich particles. Sea salt was also present in the atmosphere. In summer, Ca concentrations were low, while S concentrations were abundant. |

| 7. | China [62] |

Museum of the Terracotta Warriors and Horses of Emperor Qin | electron microscopy and energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry (SEM-EDX) | Most of the airborne particles in the museum consisted of soil dust, sulphur-containing particles, and low-sulphur particles such as soot aggregates and biogenic particles - tourists contribute to indoor airborne particulate matter |

| 8. | Belgium [63] |

Plantin-Moretus Museum/Printing Workshop Antwerp | energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (EDXRF) and electron probe microanalyzer (EPMA) methods | The results show that in the fine fraction, the proportion of C-rich particles ranged from 35 % to 80 %, while in the coarse fraction these values ranged from 25 % to 45 %. |

| Device | MICA (inBiot) | Sensedge Mini (Kaiterra) |

| Measured parameters | CO2, PM 1, PM 2.5, PM 4, PM 10, Formaldehyde, TVOC, Temperature, RH |

CO2, PM 2.5, PM 10, TVOC, Temperature, RH |

| Measurement accuracy PM | ±5 µg·m-3 + ±5% (0–100 µg·m-3); ±10% (100–1000 µg·m-3) |

±3 µg·m-3 (0–30 µg·m-3); ±10% (30–1000 µg·m-3) |

| Measurement technology | laser scattering technology | laser scattering technology |

| Technical certificates | RESET, WELL | RESET, WELL |

| Cost (€) | 500 | 750 |

| No. | Device | Sensor type | Measured parameters | Typical applications |

Accuracy/role in research |

Measurement range |

| 1 | TSI SidePak AM510 [48] |

Portable dust monitor | PM 2.5, PM 10 | Personal exposure, sports, schools | High, mobile | 0,001–20 mg·m-3 (1–20 000 µg·m-3) |

| 2 | TSI DustTrak II/DRX [49] |

Laser dust monitor | PM 1, PM 2.5, PM 4, PM 10 | Laboratories, epidemiology, fitness |

Very high, reference |

0,001–150 mg·m-3 (II), 0,001–400 mg·m-3 (DRX) |

| 3 | GrayWolf AdvancedSense [67] |

IAQ – multi-parameter | PM, VOCs, CO2, T, RH | Comprehensive IAQ research | Very high | up to 100 000 µg·m-3 (depending on the module) |

| 4 | PCE-PQC 34 [68] |

Particle counter | PM 1, PM 2.5, PM 4, PM 10, number of particles | Scientific research, reference | Very high | 0,3–25 µm (size range, mass dependent mode) |

|

5 |

PurpleAir [69] |

Optical PM sensor | PM 1, PM 2.5, PM 10 | Citizen science networks, global monitoring | Average (compensated by quantity) | 0–1000 µg·m-3 |

| 6 | inBiot MICA [70] |

IAQ | CO2, PM 2.5, PM 10, VOCs, T, RH | Schools, offices, education | Good, implementation | 0–1000 µg·m-3 |

| 7 | Kaiterra [71] |

IAQ | CO2, PM 2.5, VOCs, T, RH | Offices, homes, schools | Popular, easy to use | 0–1000 µg·m-3 |

| 8 | Canāree A1 [72] |

Personal IAQ | PM 2.5, PM 10, VOCs, CO2, T, RH | Individual monitoring | Good, unique mobility | 0–6000 µg·m-3 |

| 9 | GreenYourAir Device 1178/PM2.5 [19] |

PM network sensor | PM 2.5 | Fieldwork (Greece) | Average | Measurement every 3 minutes, long-term |

| 10 | Qingping Air Monitor Lite [28,73] |

IAQ sensor | PM 2.5, CO2, T, RH | Academician (Beijing) | Satisfactory | 0–1000 µg·m-3 |

| 11 | Sampler ARA N-FRM [28] |

Reference sampler | PM 2.5 | Reference studies | Very high (reference) |

Reference method |

| 12 | HPMA115S0 [35,74] |

Sensor PM | PM 2.5, PM 10 | Schools (Portugal) | Average (15%) | 0–1000 µg·m-3 |

| 13 | Aerocet-831 [42,75] |

Portable meter | PM 1, PM 2.5, PM 4, PM 10 | Fitness Centers (Taiwan) | Average | 0 – 1,000 µg·m-3 |

| 14 | DustTrak 8533/8534 [43,44,76] |

Laser dust monitor | PM 1, PM 2.5, PM 4, PM 10, TSP | Sports halls | Very high | 0.001 to 150 µg·m-3 - 1 minute readings |

| 15 | Personal pump + gravimetric filtres [29] |

Gravimetric | PM 2.5 | Epidemiological studies (USA) | Very high (reference) |

Gravimetric method |

| 16 | XRF + CMB, EF, FA, PMF [56] |

Analytical methods | Chemical composition PM 2.5 i PM 10 | Identification of sources in museums | Very high | Composition analysis |

|

Flow (m3·h-1) |

Filter efficiency (%) |

Scenario |

PM 2.5 reduction (%) |

| 100 | 35 | LL | 7 |

| 100 | 65 | HL | 15 |

| 100 | 95 | LH | 20 |

| 100 | 95 | HH | 22 |

| 600 | 35 | LL | 29 |

| 600 | 65 | HL | 32 |

| 600 | 95 | LH | 35 |

| 600 | 95 | HH | 38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).