1. Introduction

In recent years, a trend has been observed in Mediterranean areas showing an increase in both the frequency and severity of adverse events related to temperature and precipitation. Extended periods of drought, episodes of extreme temperatures, and prolonged heat waves have become more common [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. It is well known that long periods of low rainfall and high temperatures generate elevated rates of evapotranspiration, ultimately intensifying climatic severity [

7,

8,

9].

These changes in precipitation and temperature patterns are increasingly linked to climate change [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. In this scenario, water availability is reduced and is negatively affecting the volume of water reserves. At the same time, high rates of evapotranspiration are clearly harming both soil and plant moisture levels.

In the case that concerns us in this work, droughts significantly reduce the availability of water for irrigation and, consequently, soil moisture levels, which—together with high rates of evapotranspiration, as previously mentioned—cause crops to experience substantial water stress. This results in fields being abandoned, crops drying out completely, or, at best, exhibiting stunted growth that severely diminishes productivity [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

This situation is evident in Mediterranean regions that face this severe climate crisis [

21], leading to fierce competition for water resources. These are complex areas where an intense struggle for water affects not only agricultural spaces independently, but also urban areas and, especially, those where both coexist [

22], further aggravating the problem. In such territories, there is a coincidence: the most productive irrigated agricultural areas overlap with zones designated for urban development; here, population growth, tourism-related activities, urban expansion, and intensive irrigated agriculture all converge [

23,

24].

Paradoxically, irrigated crops have continued to grow, as we will demonstrate later, with subtropical crops—mainly mangoes and avocados—expanding most persistently despite being in a semi-arid environment. This has created a high demand for water, which is necessary to achieve optimal yields. This type of crop was introduced to the Mediterranean region of Europe from Central America, specifically from Mexico, about 30 years ago. In this context, these crops have become locally sourced products for the European market, highly sought after by consumers, and they fetch prices that are especially attractive for farmers. This not only explains why cultivated areas have steadily increased in the study area over recent decades, but also why this has become a way of life for many farmers; therefore, any solution must take their needs and acceptance into account.

The increasing demand for water to sustain agricultural production of these crop types has become a serious problem in these arid and semi-arid regions [

25,

26]. On numerous occasions, the urgent need to adopt more efficient irrigation strategies has been raised in order to ensure sustainable and economically viable production [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Conversely, water scarcity can represent a significant obstacle for farmers, which is further exacerbated during drought periods [

32], as production becomes severely limited during those times [

33]. In response to this shortage, groundwater pumping is often used to compensate for the lack of surface water, being, in many cases, the only alternative to offset the deficit and maintain yields [

34,

35]. In this context, and despite all the above, there remains an inadequate awareness regarding water scarcity and the efficient use of water resources. This has led farmers to over-irrigate, causing notable decreases in the water table, with risks of salinization and depletion [

36,

37].

Thus, the scope of the analysis focuses on a Mediterranean area in the south of the Iberian Peninsula. In this region, there is ongoing overexploitation of water reserves for this type of crops. Although it is evident that this is currently a difficult problem to solve, it is clear that studies analyzing it in depth, such as the one we present here, are necessary. Therefore, we want to show that, from a climatic perspective, periods of drought and high temperatures will become increasingly frequent. It is also crucial to design irrigation strategies that adapt to shortages and periods of scarcity, considering that there may be limitations in water resources at times. The frequency, amount, and distribution of irrigation must be regulated, even though these crops suffer serious dehydration damage under extreme heat and deficit irrigation conditions [

38,

39,

40].

Based on the territorial evidence that illustrates the issue at hand, we propose the following objectives for analysis. First, to examine how drought is impacting the availability of water resources. Second, to analyze how water deficits affect irrigated crops, particularly subtropical crops. Third, to determine whether there is any spatial pattern in the distribution of crops that is conditioned by water scarcity. Finally, to provide reflections aimed at minimizing the problem based on the analyses carried out.

To this end, we propose a methodology that can be replicated in other territories with similar characteristics and that allows for the systematization of procedures to obtain knowledge useful to researchers interested in this field of study. At the same time, it is a methodological proposal that seeks to contribute to water sustainability in this type of agricultural crops, demonstrating that technological solutions exist to make agricultural production more efficient.

We rely on the fact that this topic has been widely developed across various lines of research. From a geographical perspective, the most compelling area is not only the study of the spatial expansion of crops or their environmental consequences, but also the application of remote sensing techniques for crop monitoring, specifically to manage their conditions through precision agriculture approaches [

41,

42,

43,

44]. It is also essential to understand the variable behavior of crops and to measure their evolution over time in order to achieve efficiency in the use of inputs, thus saving water resources—not only aiming for economic savings but also for more rational water use in irrigation.

Thus, the methodology first addresses the identification of the duration and magnitude of drought periods. For this, we have used the SPI (Standardized Precipitation Index) and SPEI (Standardized Precipitation-Evapotranspiration Index). In 2009, the WMO (World Meteorological Organization) recommended that countries use the SPI as the main index for meteorological drought, since it is an effective indicator for identifying, monitoring, and analyzing drought conditions [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. We used these indices to define the type and intensity of drought, as they facilitated its monitoring. As is known, a drought period occurs whenever the SPI, regardless of the time scale analyzed, remains continuously negative and reaches an intensity of -1.0 or lower; the event ends when the SPI becomes positive [

50]. Each drought event, therefore, has a duration defined by its beginning and end, and a different intensity for each month it persists. The SPEI index, based on the SPI, includes a temperature parameter, which allows the effect of temperature on the emergence of droughts to be considered through a basic calculation of water balance [

51]. This makes it ideal for observing the impact of rising temperatures caused by climate change in regions where temperature significantly influences the effects of drought [

52], such as during the Mediterranean summer season. This index quantifies the severity and temporal variability of droughts [

53], with a multiscale character that is crucial for analyzing impacts on vegetation [

51,

54]. The advantage of using multiscalar drought indices is related to their ability to account for differences in the response times of vegetation or water reserves to conditions of water deficit [

55,

56].

Combining the information provided by the aforementioned indices with the use of remote sensing is fundamental for generating agronomically applicable data, broadening the scope of analysis when we rely on data collected by remote sensors with different resolutions, and therefore at different scales. It is precisely this interplay of scales that, until now, has allowed for more precise diagnostics at the crop level. However, with improvements in remote sensing systems, a single scale may be sufficient to discern parameters such as crop heterogeneity, detect problems early, or determine possible water needs [

57,

58]. Nonetheless, other scales remain relevant and are valuable for these types of studies, such as supplementing information with sensors installed in the soil or on UAVs that collect highly accurate, site-specific data within plantations [

59]. Moreover, thanks to open access to a wide variety of remote sensor imagery, it is possible to expand the application of remote sensing techniques. There are numerous experiences and applications in different crops using products from various remote sensors [

60,

61,

62].

This study utilized Sentinel imagery from the Copernicus program. Such images have been in use for some time. Many studies have employed Sentinel-2 data [

63], including for the remote estimation of crop and grass chlorophyll and nitrogen content using red-edge bands on Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-3 [

64], for evaluating the potential of using crop biomass [

65,

66], or for land cover classification using Sentinel-2A [

67]. The use of this data source is determined by its utility for obtaining vegetation indices, as our interest here is in acquiring useful information about crop status. These data have proven extremely useful for analyzing crop conditions and their level of water stress, allowing us to map their distribution and the changes occurring in cultivated surfaces, which, as we will see later, are highly dependent on extreme climatic events such as drought [

68]. Since there is a freely accessible image archive available from 2015 onward, it is possible to conduct time series analyses from that date. In this way, we have been able to observe the dynamics of drought effects on crops and regularly update the information [

69,

70]. Furthermore, a spatial resolution of 10x10 meters per pixel has been achieved, allowing for more detailed analysis and yielding excellent results [

71,

72,

73,

74]. Thanks to this, we have been able to make more precise interpretations [

75,

76].

As a result, we have monitored crop status in relation to periods of drought, extreme heat and heatwaves. The scientific literature supporting our study in this area is extensive. Drought analysis based on vegetation conditions has emerged as one of the strongest research topics in remote sensing [

17,

77,

78]. Another aspect related to our work is how climatic conditions influence physiological and biochemical changes that reduce crop health, enabling the identification of areas with water stress [

79,

80,

81,

82], since the leaves of trees—and specifically, chlorophyll, its structure, and water content—show observable changes according to their spectral response [

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88]. Other studies confirm significant links between leaf chlorophyll and water content, canopy temperature, and tree water stress [

89,

90]. It has also been observed that when soil moisture falls below the drought threshold and cannot meet water demand, crop cells begin to lose water, leading to changes in morphological structure and canopy cover [

91,

92]. With this, we have been able to detect zones with less effective irrigation, observing reductions in greenness and water content as signs of plant stress [

1,

93]. Finally, the objectives of our study required the use of vegetation indices as indicators to complete the analysis, evaluating the dynamics of crop status in relation to droughts and their effects on crops [

94,

95], thus providing information on their health status [

96,

97,

98,

99,

100].

The following vegetation indices were used in this study to analyze the effects of drought on crops: NDVI, NDWI, NDMI, NDDI, MSI, GNDVI [

16,

101,

102,

103]. Through NDVI [

104], we sought to observe the response of crops to drought conditions, as it is an index widely employed in these cases [

105,

106,

107], including for detecting changes in crops [

108,

109,

110]. NDVI also yields good results for monitoring crop status due to the unequivocal response when crops are irrigated. As expected, the use of the NDVI index allowed us to represent the absorption of chlorophyll pigments in plants and the reflectance of vegetative matter [

10,

68]. This has been highly useful for measuring changes in the chlorophyll content of crop canopies [

75,

111,

112], and we obtained a strong correlation between these changes and episodes of precipitation deficit, given that plants responded by reducing photosynthetic activity, leading NDVI values to decrease [

113]. It was observed that if an area consistently shows low NDVI values, this indicates a need for irrigation to maintain or promote crop growth [

36,

114]. Other indices we have tested include MSI, which has helped assess crop and soil water content and stress [

114,

115]. NDWI and NDMI have proven sensitive to changes in the leaf water content that forms the canopy [

94,

116,

117], allowing us to establish the relationship with soil moisture content [

118].

On the other hand, this study aimed to address the intensity, geographic scope, and temporal dynamics of droughts, which largely depend on how vegetation indices are interpreted and applied [

36,

113,

119]. The combination of indices and the classification of their values have been very important for establishing reliable indicators of crop stress, mainly due to dry conditions, allowing degrees of intensity to be defined [

120]. The spatial extent of drought has been determined by examining the distribution patterns of drought values in relation to the vegetation indices applied to these crop areas [

34,

121].

Given that the analysis process cannot be static, we have conducted temporal monitoring of drought with the aim of understanding complete dynamics, from the beginning of the period considered (2014) until recovery after precipitation events [

122]. The goal was to measure its duration and intensity through the changes observed in index values over time, thus facilitating the spatiotemporal assessment of its effects on the territory [

91,

123]. Therefore, a combined use of vegetation indices and drought monitoring indices was implemented [

124,

125,

126]. Studies indicate that this is the best way to analyze drought and that by combining multiple data sources—including vegetation indices with hydrological or meteorological data—a more comprehensive perspective is obtained [

10,

113,

127,

128]. This approach aids the construction of multisensor models [

129], which integrate various techniques to better address the complexity inherent in studying drought [

53,

102,

130]. Drought indices can incorporate all this information: meteorological data, the status of water resources and reserves (both surface and groundwater), and vegetation indices. Altogether, this information can enhance management and irrigation techniques applied to crops with varying water needs, which is essential for measuring water use efficiency in conditions of scarcity [

131,

132,

133,

134,

135,

136].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

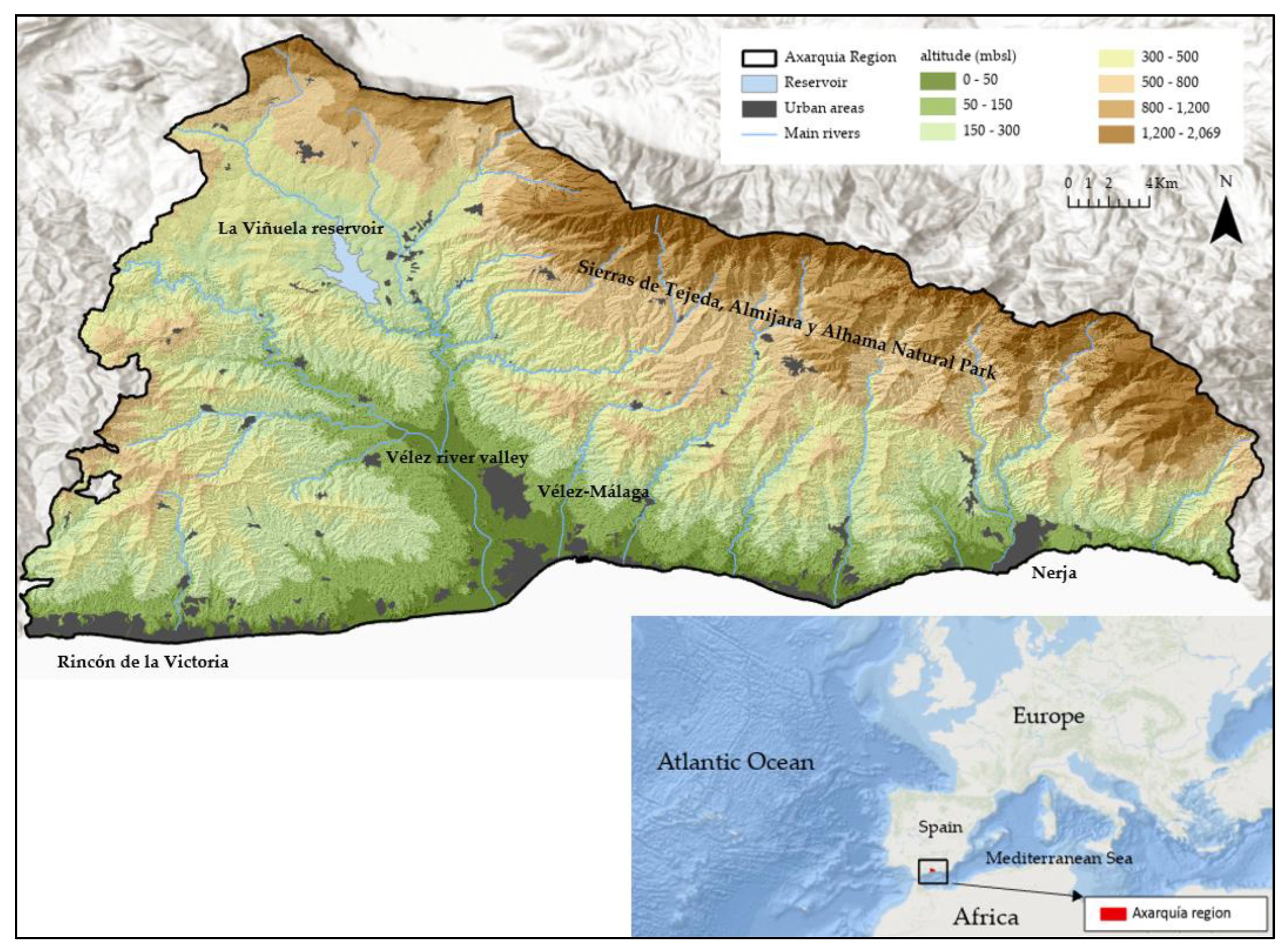

The study area is classified, from a climatic standpoint, within the semi-arid Mediterranean zones, which are considered critical regions of the Mediterranean climate due to their tendency toward increasing aridity [

77,

137]. This includes southern Spain, located at the western edge of the Mediterranean Sea (

Figure 1). The study area covers an extension of 1,023.72 km² within this region. It is particularly interesting for research given the diverse situations related to the study topic. The area is characterized by complex orography, with an altitudinal gradient exceeding 2,000 meters above sea level within just 20 km from the coast. This topography prevents cold air masses from entering and moderates winter temperatures, while conversely accentuating summer heat. Agricultural spaces are concentrated in the valleys, as the remainder of the land is mountainous, reducing the availability of arable soils. In these valleys, groundwater resources and the most fertile soils for cultivation are also located.

As previously mentioned, the study area features a typical subtropical Mediterranean climate, with an average annual temperature of 17.4°C and a maximum of 28°C, as well as an average annual precipitation of 576 mm. These temperatures are favorable for cultivating subtropical species such as mango and avocado, which require temperatures between 10°C and 30°C. Outside this range, the crop's potential yield decreases, necessitating the identification of zones that meet the required temperature thresholds. This is why the initial cultivation areas were located along coastal riverbanks, where a very mild microclimate prevails due to the presence of high mountains adjacent to a warm, continentalized sea—the Mediterranean. This setting provides protection from inland cold while also creating a sunny microenvironment on south-facing mountain slopes.

As for rainfall, it is insufficient for this type of crop, and even more so for any irrigated agriculture, since these crops require daily or near-daily irrigation on a regular schedule. For this reason, the establishment of irrigated crops in the area was made possible by the availability of surface water resources, which are hydrologically regulated by the Viñuela reservoir. In this text, we will refer to these resources as stored water, used both for agricultural irrigation and urban supply. On the other hand, dryland crops predominated until the construction of the reservoir in 1994. As is known, dryland crops in Mediterranean regions are much less demanding in terms of water, as they rely on rainfall. Since then, irrigated crops have continuously expanded, especially subtropical varieties such as avocado and mango [

138]. It has already been noted that these crops require large volumes of irrigation water, which, alongside coastal tourism, creates significant pressure on the scarce available water resources [

39,

139,

140]. For instance, in recent years, a total of 1,342 illegal infrastructures related to water extraction have been identified as a means for many farmers to increase water availability, responding to water scarcity or supply shortages due to the absence of adequate hydrological planning [

141].

The irrigated area within the study region was measured at 14,372.56 hectares in 2023, according to data from the Natural Heritage Information System of Andalusia (SIPNA, acronyms in Spanish). Of this total, subtropical crops accounted for 63.59%, covering a surface area of 8,942.52 hectares. It is important to consider newly established plantations, which occupy 2,418.42 hectares (14.98% of the total irrigated area) and are not yet included in production data. Horticultural crops covered 1,585.81 hectares (11.27% of the irrigated area), citrus crops occupied 557.14 hectares (3.96%), and greenhouses covered 868.67 hectares (6.17%). As can be understood, all of these crop types require abundant water resources for their survival.

It is also important to note, especially due to its implications for water demand, that the average age of the crops is 9 years, ranging from 6 years in the youngest plantations to 20 years in the oldest. Most of these are mature, productive trees. The planting patterns used—which determine tree density—range from the traditional spacing of 8x8 m to 7x8 m, to narrower layouts in younger, primarily intensive plantations: 4x4; 4x1.5; 3x3; 3x1.5; and 2x1.5 m². For example, in one hectare (10,000 m²), for an 8x8 m grid, each tree occupies 32 m², resulting in a total of 312 trees. If the grid is reduced to 4x4 m—a medium-density model—each tree occupies 16 m², increasing the number to 625 trees per hectare. The plantation structure, as with any other crop, is determined by the grower, who should consider the environment and soil conditions to establish the appropriate number of seedlings.

According to data collected by the authors in the field, it is evident that a sufficient and well-distributed water supply is vital for an avocado plantation to remain healthy and achieve high yields sustainably over many years. On average, an avocado tree requires approximately 110 liters of water per week, while a mango tree requires between 50 and 120 liters per day. It is important to note that the irrigation method used is drip irrigation, as this system allows water to be applied directly to the root zone and offers greater control over moisture loss under the prevailing environmental conditions of these Mediterranean semi-arid environments. However, it should be mentioned that irrigation systems largely depend on soil type; generally, there are 2–3 laterals per row of trees, with an emitter flow rate of 0.6–2.3 l/h, increasing up to 4 l/h during the hottest months, and an irrigation frequency of approximately 6 hours per day.

The estimated water needs for crops in this area are around 8,000 m³/ha per year, as calculated by local irrigation communities. Nevertheless, several factors influence the determination of these needs (climate, plantation orientation, tree age, soil type, etc.), which can even vary at the plot level. The agency responsible for water distribution, the Confederación Hidrográfica del Sur, under the Government of Spain, has set an allocation of 7,692 m³/ha for subtropical crops in the study area. This figure is clearly insufficient for growers and does not meet the water requirements of these crops, especially during periods of severe precipitation shortage. To check the availability of stored water, real-time data on reservoir volumes can be accessed through the Automatic Hydrological Information System (SAIH, acronyms in Spanish) of the Red Hidrosur (

https://www.redhidrosurmedioambiente.es/saih/).

2.2. Materials and Methods

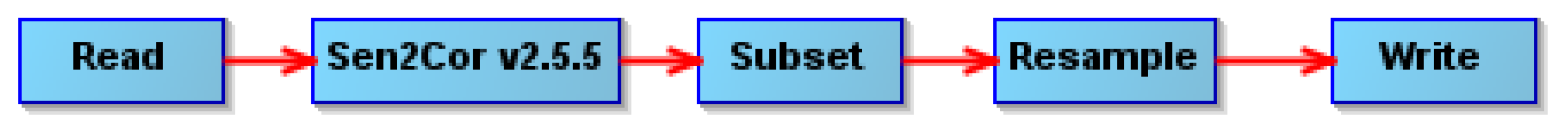

To address the objectives of the study, we followed the scheme presented below in

Figure 2, which serves as a reference for the subsequent methodological development.

As shown in

Figure 2, in order to assess the magnitude of demand pressure on water resources, we analyzed precipitation patterns using the SPI index, which helps identify meteorological drought, and the SPEI index at time scales greater than 12 months, which is used to detect hydrological drought periods and their intensity. To quantify the irrigated areas, we utilized land use information downloaded from the Andalusian Natural Heritage Information System (SIPNA, acronyms in Spanish). Based on this data, the area occupied by these types of crops was delineated. Finally, satellite images for remote sensing analysis were obtained from the Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem (Sentinel 2A). The starting date for data analysis coincides with the implementation of stored water resources in 1994 and extends to 2024 (a 30-year period) that provides sufficient perspective on the evolution of climatic conditions.

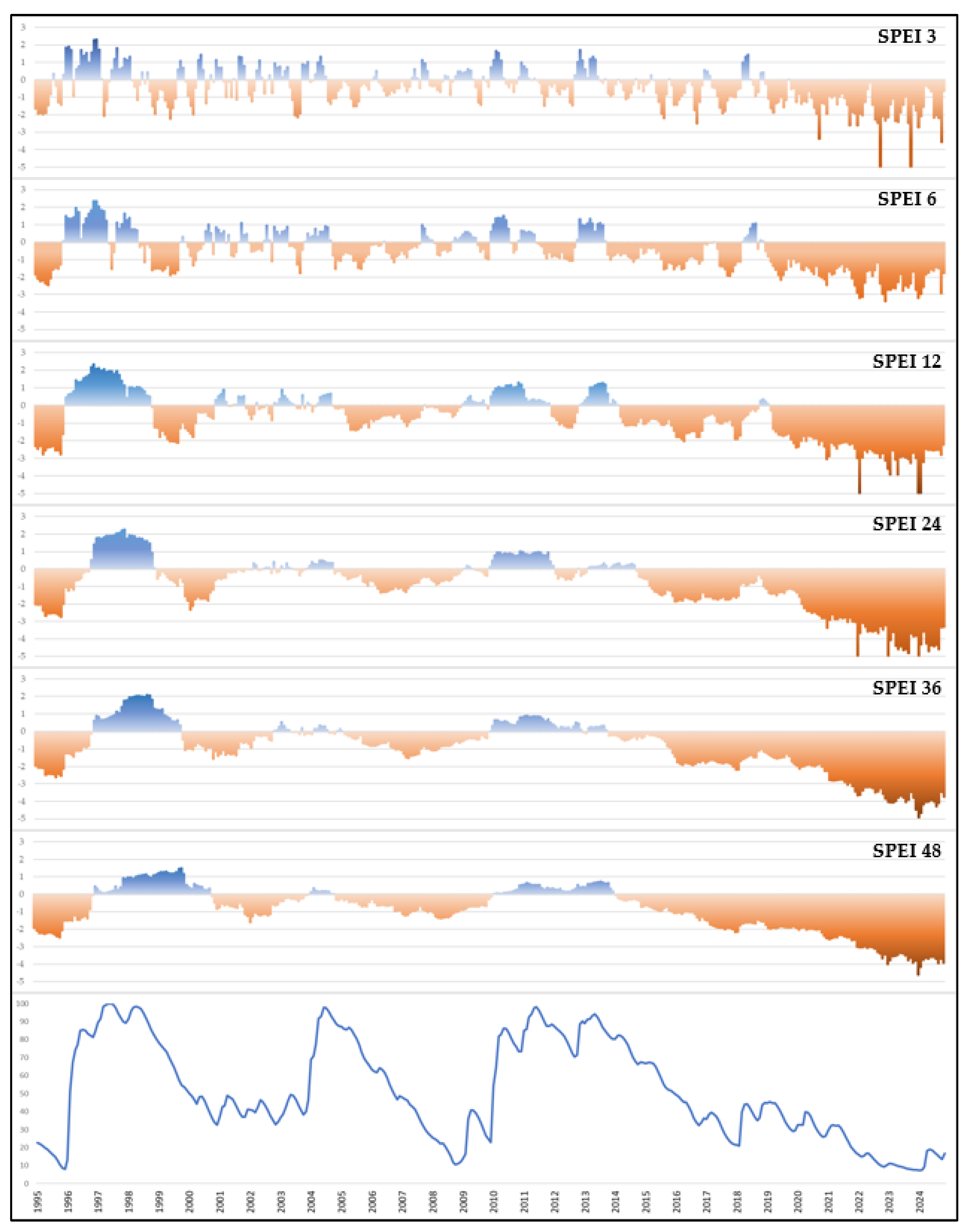

2.3. Temporal Delimitation of Drought Periods

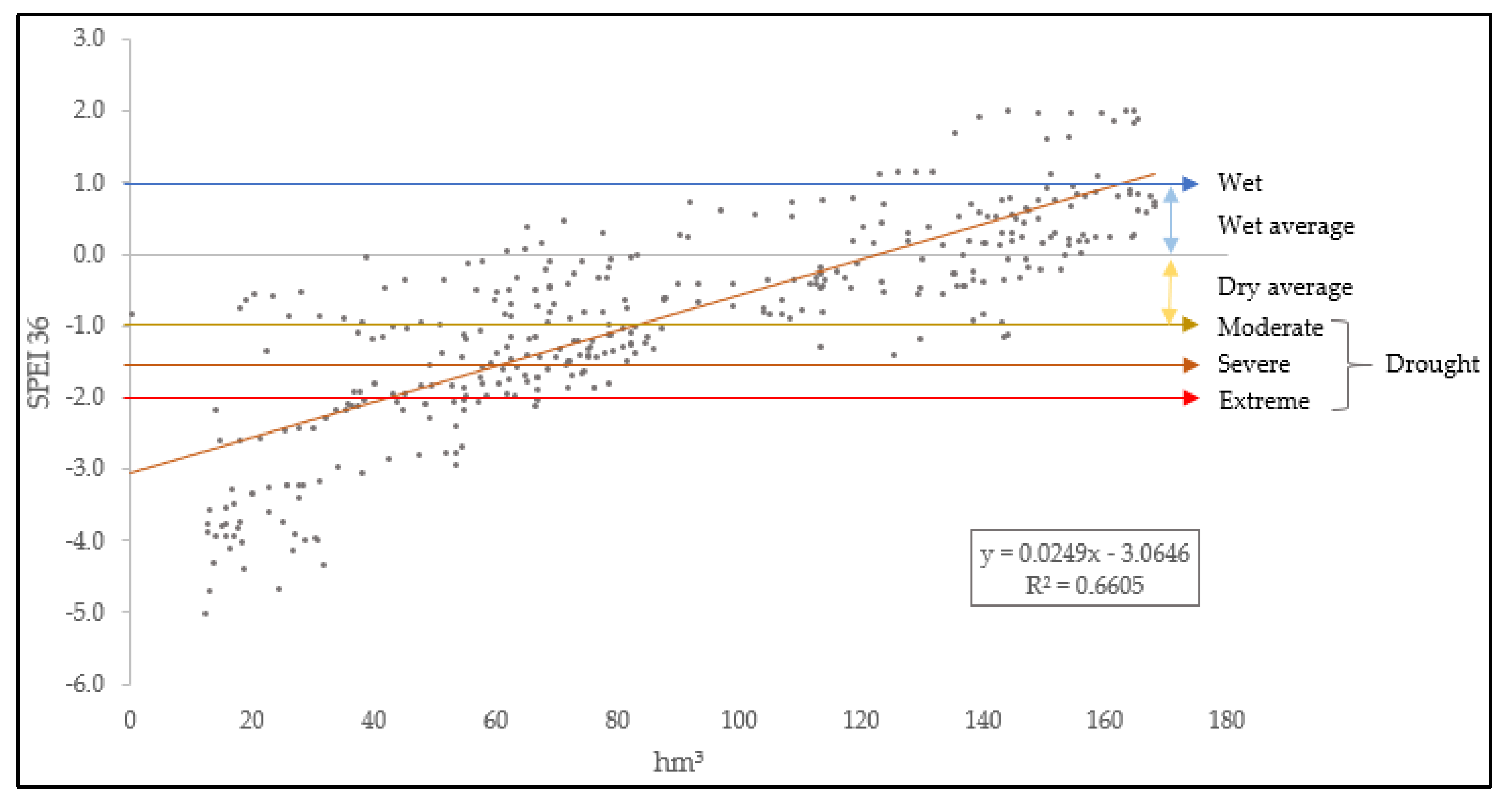

The methodological process begins with identifying the duration and magnitude of drought using data from the SPI and SPEI indices at various time scales, along with the volume of accumulated water that supplies irrigation for subtropical crops [

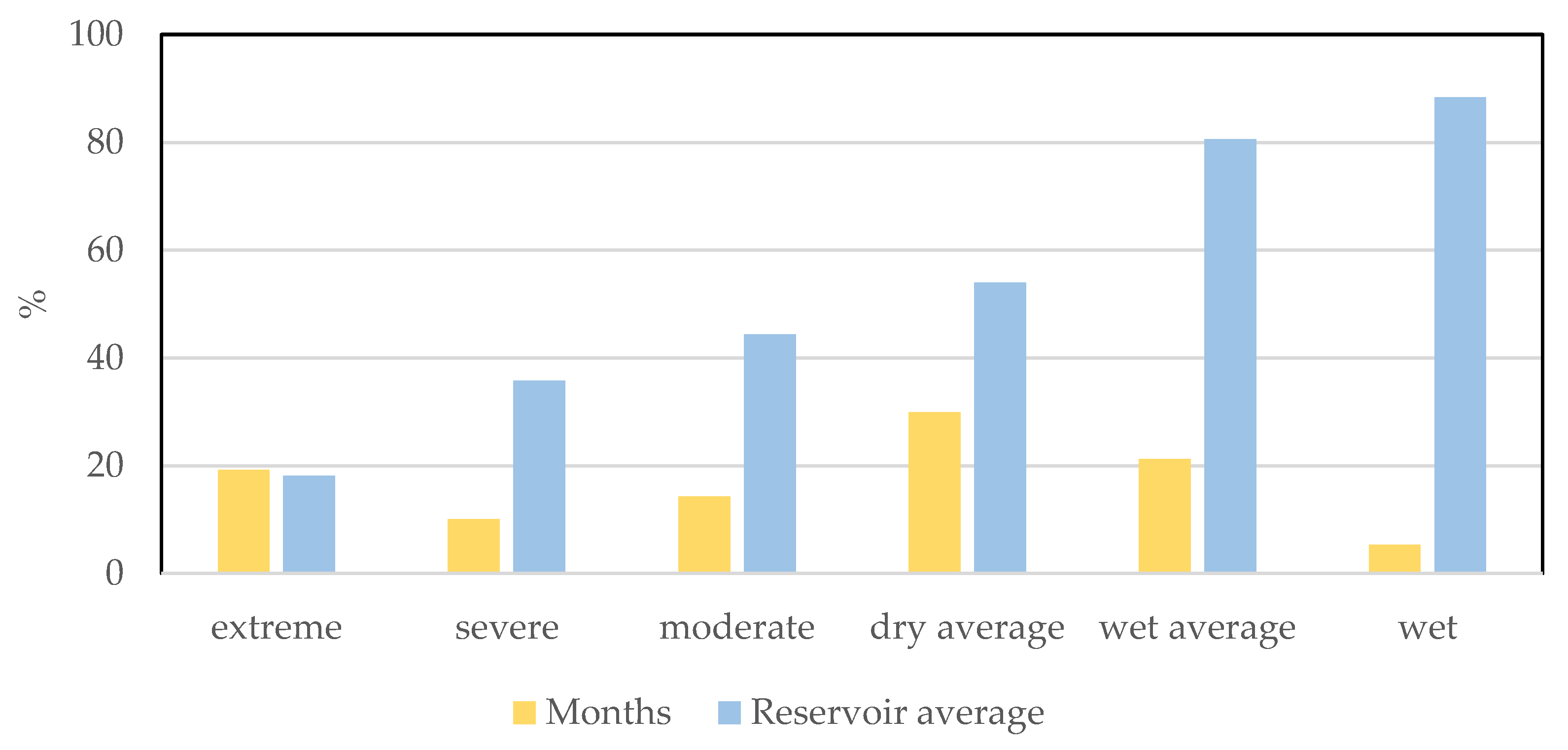

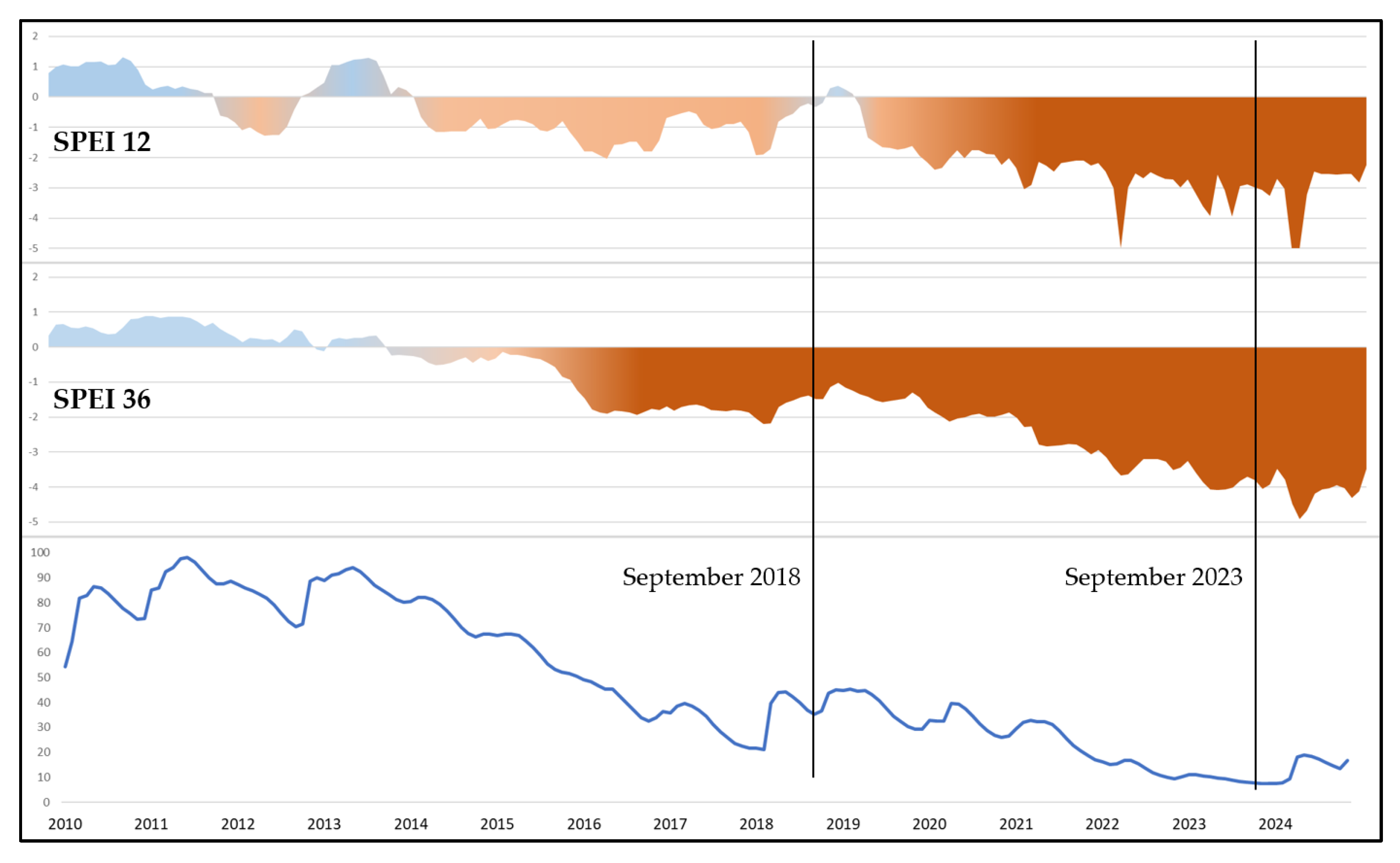

77]. Selecting the appropriate time scale for both indices is crucial to define the type of drought being analyzed [

55,

142]; therefore, monthly reservoir water values are correlated with monthly SPI and SPEI values from 1 to 48 months using Pearson's correlation. The highest correlation indicates the most suitable time scale for defining hydrological drought, since a drop in reservoir levels directly results in reduced water resources for irrigation [

56,

143]. Once the time scale is selected, the impact of different drought magnitudes on reservoir water levels is observed, and a linear regression is applied to confirm the prediction. Additionally, it is essential to monitor the 12-month SPEI behavior, as a longer drought period might mask a shorter wet period that is sufficient to allow a temporary recharge of reservoir water and, consequently, an increase in extractable availability [

53]. Finally, to determine the drought period to be analyzed, it is necessary for the SPEI value to remain below -1 continuously over time [

45], combined with water reserves reaching a deficit level that leads to insufficient irrigation resources.

2.4. Satellite Image Acquisition and Processing

Once the drought event is defined, available satellite images are selected for both the initial date—which indicates the crops’ previous condition—and the final date, to evaluate the end state and evolution throughout the drought. The chosen image dates begin in September for two main reasons: first, to ensure that the water supplied to the crops comes exclusively from irrigation, taking advantage of the Mediterranean climate’s typical summer drought [

45,

111,

144]; and second, because this is a key stage when the fruit is reaching full development, immediately before harvesting, meaning that a lack or deficit of irrigation directly impacts crop health and reduces productivity [

1,

93,

102]. Our analysis centers on the use of Sentinel-2 satellite imagery from ESA’s Copernicus program. As is known, Sentinel-2 currently includes two active satellites (the Level 2A and Level 2B products), which, through their multispectral optical sensors, provide images across 13 spectral bands. The minimum spatial resolution is 10x10 meters (10 m/px) for most bands, with 20 m and 60 m resolution for others (see

Table 1). This resolution is well suited for the objectives of our study and the geographic area under analysis.

Downloading and processing are conducted using SNAP software, specifically developed to handle imagery from the Sentinel satellites. Additionally, the Sen2Cor plugin is installed, which serves as an excellent tool for atmospheric and geometric correction of Sentinel satellite data (the Level-2A product) [

53,

145]. This procedure is essential for performing multitemporal image analyses and for reliably comparing spectral indices [

146]. The following steps are undertaken:

- 1)

Download Sentinel 2A and 2B satellite images at Level L1C using the “Product Library” tool for the selected dates that include our study area, which is divided into two images.

- 2)

Atmospheric correction of the images is performed with the “Sen2Cor” tool, upgrading them from Level L1C to Level L2A to enhance visualization.

- 3)

Crop the images spatially and spectrally using the “Subset” tool, defining the study area and selecting the bands to be used—specifically bands 2, 3, 4, 8, and 11—to reduce data volume.

- 4)

Standardize the spatial resolution of the spectral bands to 10 meters with the “Resampling” tool, since band 11 has a resolution of 20 meters and the rest are 10 meters.

- 5)

Merge the two images that make up the study area with the “Mosaicking” tool, using the WGS84 projection, ortho-rectified with the Copernicus Global DEM at 30 meters and a pixel size of 10 meters.

This workflow can be implemented by building a model using the “Graph Builder” tool (

Figure 3). Once the model is defined, the “Batch Processing” tool allows users to load the created model and apply it to different images simultaneously, streamlining the process.

Es preciso aplicar también un proceso de verificación para el control de las calidad de las imágenes, sobre todo como es el caso, cuando se trata de estudios cuantitativos y multitemporales, ya que de ello depende la calidad de los resultados. Hemos observado que uno de los principales problemas que tiene el uso de imágenes Sentinel-2 para este tipo de estudios es el de la corrección atmosférica y de iluminación.

It is also essential to implement a verification process to ensure the quality control of the images, especially in quantitative and multitemporal studies, as the reliability of the results depends on this. One of the main challenges associated with the use of Sentinel-2 images for such studies is atmospheric and illumination correction. In Sentinel-2 products, a preliminary step before utilization involves converting radiance to apparent reflectance at the top of the atmosphere (TOA) for a flat surface. This transformation is straightforward but must be followed by a conversion from apparent reflectance to true reflectance, i.e.; at the surface level (BOA, bottom of atmosphere). Variables considered in the transformation from radiance to BOA reflectance include illumination geometry, water vapor content, and aerosol optical thickness in the atmosphere. Additionally, the potential influence of clouds must be taken into account, especially cirrus or translucent clouds, which are common in semi-arid environments due to typical atmospheric conditions (surface heat and high-altitude cold). This results in persistent daytime haze when winds are absent. The quality of atmospheric correction results depends on the accuracy of available input data for these variables and effects, as well as the model applied to the radiance or TOA reflectance image [

147,

148].

Image correction is performed using the Sen2Cor tool, as previously mentioned. Sen2Cor is a processor for Sentinel-2, Level 2A product generation and formatting. It performs atmospheric, terrain, and cirrus corrections on Top-Of-Atmosphere (TOA) Level 1C input data, producing Bottom-Of-Atmosphere (BOA) output. Its product format is equivalent to the Level 1C User Product: JPEG 2000 images, at three different resolutions—60, 20, and 10 meters [

149]. This ensures the acquisition of images free from atmospheric reflectance artifacts that could negatively affect subsequent analysis.

Another important consideration when working with time series derived from the combination of several spectral bands is the need to access each available image individually, rather than averaging images from specific periods, as this could increase statistical error in the results of vegetation indices generated in the next methodological step. Let us examine an example:

Three sequences of images within the temporal range from 2017-10-01 to 2018-01-30.

Bands: B4 and B8 from Sentinel 2A.

Reflectance values for B4: 1, 4, 3. The mean of these values is: (2+4+3)/3 = 3.

Reflectance values for B8: 2, 7, 3. The mean of these values is: (2+7+3)/3 = 4.

Calculation of the mean reflectance values for a hypothetical NDVI case:

Calculation of individual reflectance values for a hypothetical NDVI case and the mean calculated NDVI:

Sequence 1: (2-1) / (2+1) = 0.333

Sequence 2: (7-4) / (7+4) = 0.273

Sequence 3: (3-3) / (3+3) = 0

As observed in the previous examples, it is necessary to carry out combinatorial procedures in order to reduce the possibility of error, as even using only three images, the margin of error can be quite high. Therefore, it is advisable to access all available images within the temporal study range prior to calculating vegetation indices. With this in mind, we have performed an initial filtering of Sentinel-2A images based on several factors to avoid including data from images that could introduce noise when creating vegetation indices:

- 1)

Images were selected for the study’s temporal range: from 2015 (the earliest available images) to 2024. It was necessary to harmonize images taken before and after January 25, 2002, to ensure comparability, as changes in image processing within the Copernicus program— which began generating images with new radiometric calibration— directly affected temporal image analysis, especially when conducting comparisons of vegetation indices as in this case.

- 2)

Images from the area of interest were chosen by selecting only the tile or tiles (100x100 km2 grid images, orthorectified in UTM/WGS84 projection) that encompass the study area, thus providing the input geometry.

- 3)

A clip was performed using this input geometry, cropping the 100x100 km2 images to only the area corresponding to the specific crop and variety under study. This approach allows for an accurate assessment of the heterogeneity in crop evolution, minimizing interference from other crop types or varieties. Achieving data homogeneity is essential.

- 4)

Pixels associated with water vapor (clouds) were removed, as their reflectance does not represent the surface of interest and would generate negative values when analyzing vegetation indices. To achieve this, Sentinel-2 Level-2A’s QA60 band is used—see

Table 2 for a simplified overview of the filtering criteria—by which a straightforward function is created for cloud masking. Technically, QA60 is not a true spectral band but rather reuses two far-infrared water vapor reflectance bands. The source bands are B10 and B11, with the QA60 service flagging, via a Boolean filter, any bits where opaque clouds are present. With this, we can assess each image, apply all previous filters, and finally apply this last step, which removes all pixels where QA60 indicates opaque clouds.

- 5)

When applying a bitmask for QA60, each image must be processed sequentially by date, applying the cloud-masking algorithm, and saving it with its corresponding date and without clouds. If a particular image is fully cloud-covered, it is excluded from the image collection. If it is mostly clear, it is retained, and for images with a certain proportion of removed pixels, their influence will be weighted accordingly in subsequent mean calculations.

- (1)

Bitmask for QA60.

Bit 10: Opaque clouds 0: No opaque clouds.1: Opaque clouds present.

Bit 11: Cirrus clouds. 0: No cirrus clouds. 1: Cirrus clouds present.

2.5. Image Analysis, Application of Spectral Indexes and Statistical Analysis

Once the images have been processed and corrected, the area occupied by subtropical crops is analyzed by applying various spectral indexes, which are then subjected to statistical tests to develop a model that best identifies the impact of drought events and possible irrigation deficits on these crops. The selected vegetation indexes (VI) (see

Table 3) were chosen based on scientific literature because they facilitate the interpretation of crop and soil condition under drought [

16,

17,

114]. These indexes include NDVI, GNDVI, and GCI to detect crop health and vigor [

34,

101,

111,

150], NDWI for identifying water presence [

2,

94], and NDDI, NDMI, and MSI to assess soil dryness and vegetation stress due to water shortages [

56,

94,

98,

118,

151]. It will later be shown that not all these indexes yield the expected results when subjected to statistical analysis.

The calculation of the VIs is carried out using the “raster calculator” tool in ArcGIS Pro software, where the formula for each VI is entered and applied to the already processed images. Subsequently, the area of subtropical crops is delineated based on land use data from the Andalusian Natural Heritage Information System (SIPNA), and with the “extract by mask” tool in ArcGIS Pro, the results of the VI calculations are extracted, streamlining the process. With all the VIs calculated for the area of subtropical crops, a principal component analysis is performed using SPSS software. The composition of the components will identify the VIs best suited to build an effective predictive model that can explain the impact of drought and irrigation deficit on crops, further simplifying the process [

152,

153]. The component that explains the highest percentage of variance and is consistent with the defined objective is selected. Once the component is defined, and to verify the robustness of the results, Bartlett’s test of sphericity, the KMO test, and Cronbach’s alpha are applied, making the necessary adjustments that will determine the final model to be used [

2,

113].

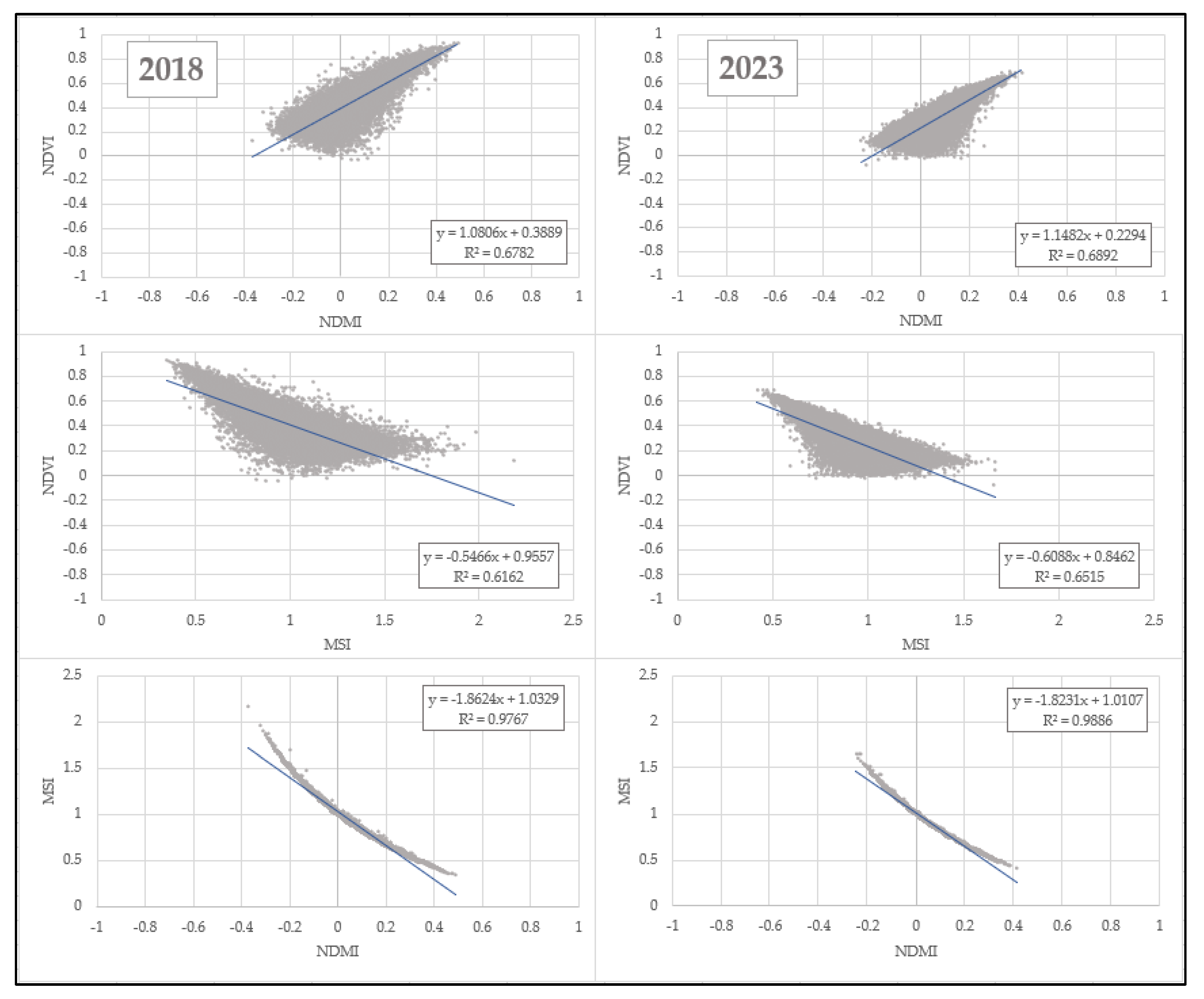

2.6. Classification of Indexes, Cluster Analysis and Mapping

Next, before conducting the cluster analysis, the results obtained from the calculation of the selected vegetation indices are classified according to the following criteria:

- 1)

For vegetation indices focused on detecting crop health and vigor, a distinction is made between crops with low and high vegetation cover, taking into account that young plantations may be included among those with low cover.

- 2)

For vegetation indices measuring canopy and soil moisture content, a differentiation is established between irrigated and non-irrigated crops, as well as the water stress they may experience due to a lack of water or insufficient irrigation.

To validate the robustness in the application of these criteria, scatter plots are generated, calculating both the correlation and the linear regression between the VIs. This process is carried out using SPSS software. In addition, specific literature has been consulted in which classifications are applied to VIs for different plant species [

2,

25,

34,

36,

49,

112,

114,

154].

Once the indices are classified, the images are reclassified with ArcGIS Pro software in order to perform a cluster analysis using the “multivariate clustering” tool, applying the K-medoids algorithm and the pseudo F statistic to select the optimal number of clusters [

155,

156]. This final cluster analysis allows for the differentiation of cultivated areas with similar characteristics and behaviors, as well as the temporal comparison of the status of subtropical crops, highlighting the most significant changes that occurred after the drought period. For this, the “compute change raster” tool is used, selecting the categorical difference method in ArcGIS Pro software. As a result, we obtain, on one hand, data that allow us to evaluate the volume and magnitude of changes experienced by the crops and, on the other, maps that make it possible to assess their spatial distribution across the territory.

Finally, for the proper application of these indices in assessing the condition of the studied crops, we have considered a series of result verification aspects:

- 1)

Disposition, quantification, and evolution of the crop. Understanding physical aspects is essential both to comprehend how the crop responds to specific events and interventions, and to interpret monitoring results. To achieve this, a temporal sequence of RGB images is conducted. This analysis allows for observation of crop evolution and temporal variability, enabling detection of possible impacts suffered by the crop, its response to solutions or management techniques applied in the field, correlation of crop behavior in areas with different productivity, as well as the recording of this information for comparison at different times.

- 2)

Study of crop behavior according to the different growth cycles during the same season. Throughout the production months, information is obtained to assess the state, variability, and evolution of crop vigor and water status, with the aim of detecting impacts and anomalies.

- 3)

Crop characterization. This is carried out considering three variables: Tree Count Management, Tree Height Measurement, and Erosion Risk, with the intention of evaluating the homogeneity of the cultivated area under analysis.

4. Discussion

As has been mentioned, the exploitation of new areas with this type of crop has become a common practice over the last few decades. This dynamic has been guided more by economic factors than by a perspective of environmental sustainability. With this work, we wanted to demonstrate this fact, in addition to the fact that in the coming decades, the conditions imposed by climate change in these territories cannot be overlooked. In these climatic domains, the scarcity of precipitation will become increasingly evident and average annual temperatures will become increasingly extreme. As a result, it will not be possible to continue planting with the current inconsistency, irrigating lands with crops that are very demanding of water. In summary, this may be the hypothesis we started from, but it was also necessary to provide a methodological proposal to support this hypothesis.

Studies indicate that the best way to analyze the complexity of the drought problem is by applying remote sensing techniques with statistical indicators, by combining various data sources, integrating vegetation indices with hydrological or meteorological data. This leads us to the construction of multisensory models, in which these various techniques are integrated to provide a better response to the complexity of the problems being analyzed.

In this work, we have once again resorted to vegetation indices in order to provide analytical elements to improve discrimination within the same type of crop in areas where differences in cover conditions occur. As is known, the use of these indices is based on their ability to discriminate plant masses by their radiometric behaviors in the different bands of the electromagnetic spectrum. We have used well-known indices such as NDVI, NDMI, or MSI. These indices have revealed significant patterns in the behavior of crops that are easily recognizable, but the study would have been incomplete if we had not analyzed the cause of the spectral response of crops, and therefore we included climatic indices such as SPI and SPEI. Various authors have pointed to the possibilities offered by combining them with vegetation indices. In this context, the analysis of the radiative transfer of leaves and canopies has been valuable for modeling and understanding the behavior of these indices. Along with this, the cause that determines the information they provide.

But perhaps there is another issue that should be considered, which we plan to analyze in future studies. We support what some authors [

166] have shown that during the different stages of cultivation, the values of the indices vary, being different both in the ripening process (the color of the avocado skin changes from bright green to dark green, almost brown) and in flowering (the leaves are a deep green color). Like other studies, we have focused on evaluating the spectral indices in terms of their sensitivity to the biophysical parameters of vegetation and the factors affecting canopy reflectance, mainly those derived from the crop's nutritional and moisture conditions.

However, we believe that it yields good results to estimate other parameters as those outlined below.

First of all, we would highlight the estimation of the vigor of the vegetation based on the chlorophyll content in the leaves, which is an indicator of the tree's nutrition and the state of its photosynthesis. In fact, the absorption of the red band is considered optimal for estimating Chl (leaf and canopy chlorophyll) and N (canopy nitrogen), coinciding with Band 4 (664.6 -central wavelength (nm)- Sentinel-2A and 664.9, Sentinel-2B). These will be indicators that will show the state of subtropical crops, presenting high and linearly positive correlations according to the amount of chlorophyll in the leaf. For avocado vegetation covers, the average NDVI values have been around 0.601, between a maximum value of 0.890 and a minimum of 0.368 during the study period, since a typical tree of this crop, being in good condition, represents dense vegetation. In this sense, the chlorophyll content in the leaf, as the variable most directly related to the values provided by these indices, allows us to determine the differences in health status. At the same time, it allows us to reduce the interpretation that we can make solely in those areas of more leafy vegetation.

Secondly, directly related to the water availability of the plant, we would highlight the water content, either from the tree canopy in particular or from the context of the plant in general. We have made this estimation based on the main NDMI index and indirectly through the effect of water stress on LAI and chlorophyll content with reference to the NDVI and MSI indices. We estimate that vegetation indices based on shortwave infrared bands (NIR and SWIR) provide good estimates. Thus, they provide significant R values (R² between 0.25 and 0.60 for NDVI and 0.30 and 0.80 for NDMI), which means NDMI shows good results in its application for monitoring crop moisture, while NDVI allows for indirect estimation, only based on the effects of changes in chlorophyll due to variations in water content and leaf area index. The application of the NDWI index has helped to estimate potential evapotranspiration, as it is related to this vegetation index through leaf vigor and water stress. We can observe that some plots that showed high vigor in the NDVI, NDWI, or NDMI displayed values that predict levels of water stress in the cover. The result of applying the MSI index has yielded a good outcome at the midpoint between the two previous ones, in such a way that, while the areas of more vigorous crops are maintained, other areas with behavior closer to average or predominant values are also observed [

170,

171,

172].

Thirdly, it has been interesting to observe the potential net productivity of the crop, related to the photosynthetically active radiation absorbed by the tree, especially when the leaves are horizontal and the soil is sufficiently dark, as is predominant in many areas of the study region. Some authors refer to an efficiency factor for each tree, although indirectly, green and dry biomass can be estimated from NDVI, GNDVI, and MSI, but in this case, different adjustments must be made for the results to be good [

173,

174].

Another aspect to consider is the LAI index, which shows a positive association with NDVI, GNDVI, and MSI, especially when the specimens are not too leafy and do not completely cover the ground, allowing for differentiation of the degree of green cover. Otherwise, with high values (above 4, mainly), NDVI becomes saturated, but MSI remains more stable. On the other hand, although indirectly, we can estimate the green biomass that will be determined by the age of the tree and its percentage of green cover, since a healthy adult tree shows a very clear response, while areas with growing specimens or greater water stress show less leaf vigor and lower canopy density [

175,

176,

177,

178,

179,

180,

181].

In fifth place and considering that this work is carried out in semi-arid Mediterranean environments, the analysis of the amount of water received by the plant canopy is fundamental, because it is obviously directly related to the vigor of the tree. However, in these areas, we find a certain lag between precipitation and the response of the vegetation cover, primarily due to its irregularity, not only in time but also in its volume. Very related to this is the potential evapotranspiration in these environments due to the high temperatures we have already mentioned and inversely related to the vegetation indices analyzed through leaf vigor and the water stress that the tree presents, mainly from May to September. This is a crucial time as the tree needs to receive the necessary water contributions, coinciding with a high evapotranspiration; to which it should be added that it is in a process of preparing for flowering, making the need for hydration and nutrient supply fundamental for the good harvest of the following season. Consequently, after a dry hydrological year or a prolonged period of drought, farmers have had to make extraordinary water contributions so that the tree is not affected.

Finally, we want to emphasize the importance of conducting an analysis of phenological dynamics, and for this we have followed the seasonal evolution of the indices (temporal variability) and considered the characteristic factors of these cycles, which we have termed cultivation stages. The results have shown differences in the behavior of the crop, although there is also a clear correlation depending on its phenological stage. This has represented an advancement in the recognition of the crop because it allows for the identification and characterization, among other aspects, of diseases, with the indices being able to detect disorders in the expected behavior [

182,

183,

184,

185].