Submitted:

27 June 2025

Posted:

01 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Work

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Remote Sensing Indexes

2.1.1. Normalized Difference Vegetation Index

2.1.2. Enhanced Vegetation Index

2.1.3. Atmospherically Resistant Vegetation Index

2.1.4. Normalized Difference Water Index

2.1.5. Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index

2.1.6. Transformed Vegetative Index

2.1.7. Normalized Difference Moisture Index

2.1.8. Normalized Multi-Band Drought Index

2.1.9. Modified Normalized Water Index

2.1.10. Modified Normalized Difference Vegetation Index

2.1.11. Ratio Drought Index

2.1.12. Red-Edge Chlorophyll Index

2.2. Machine Learning Classifier

2.3. Random Forest

2.3.1. Gradient Boosting Classifier

2.4. Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)

2.4.1. Bagging Classifier

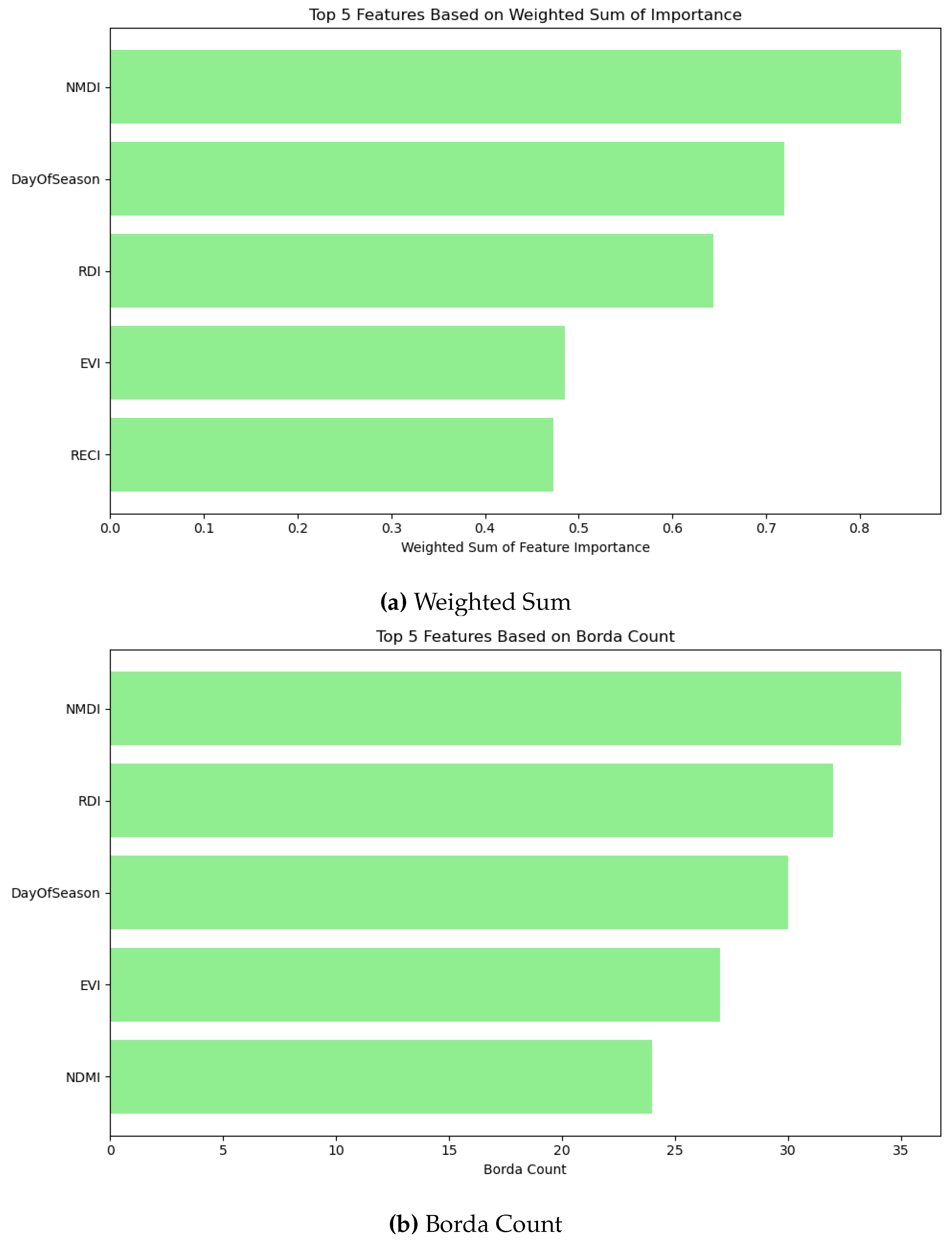

3. Feature Ranking and Aggregation Techniques

3.0.2. SHapley Additive exPlanations Analysis

3.0.3. Borda Count

3.0.4. Weighted Sum

4. Resampling Techniques

4.1. Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique

4.2. Borderline SMOTE

4.3. Adaptive Synthetic Sampling Approach

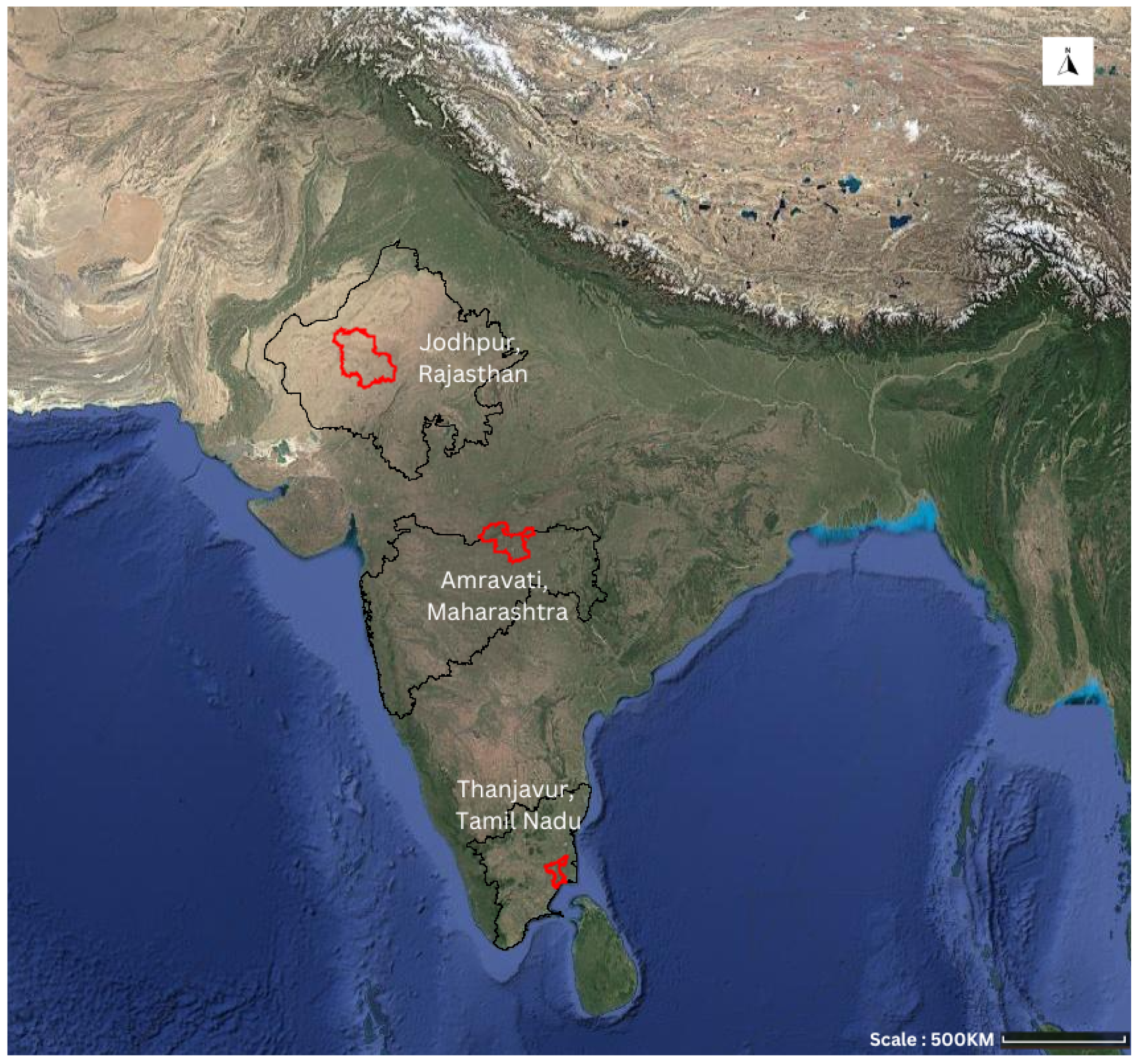

5. Data and Study Area

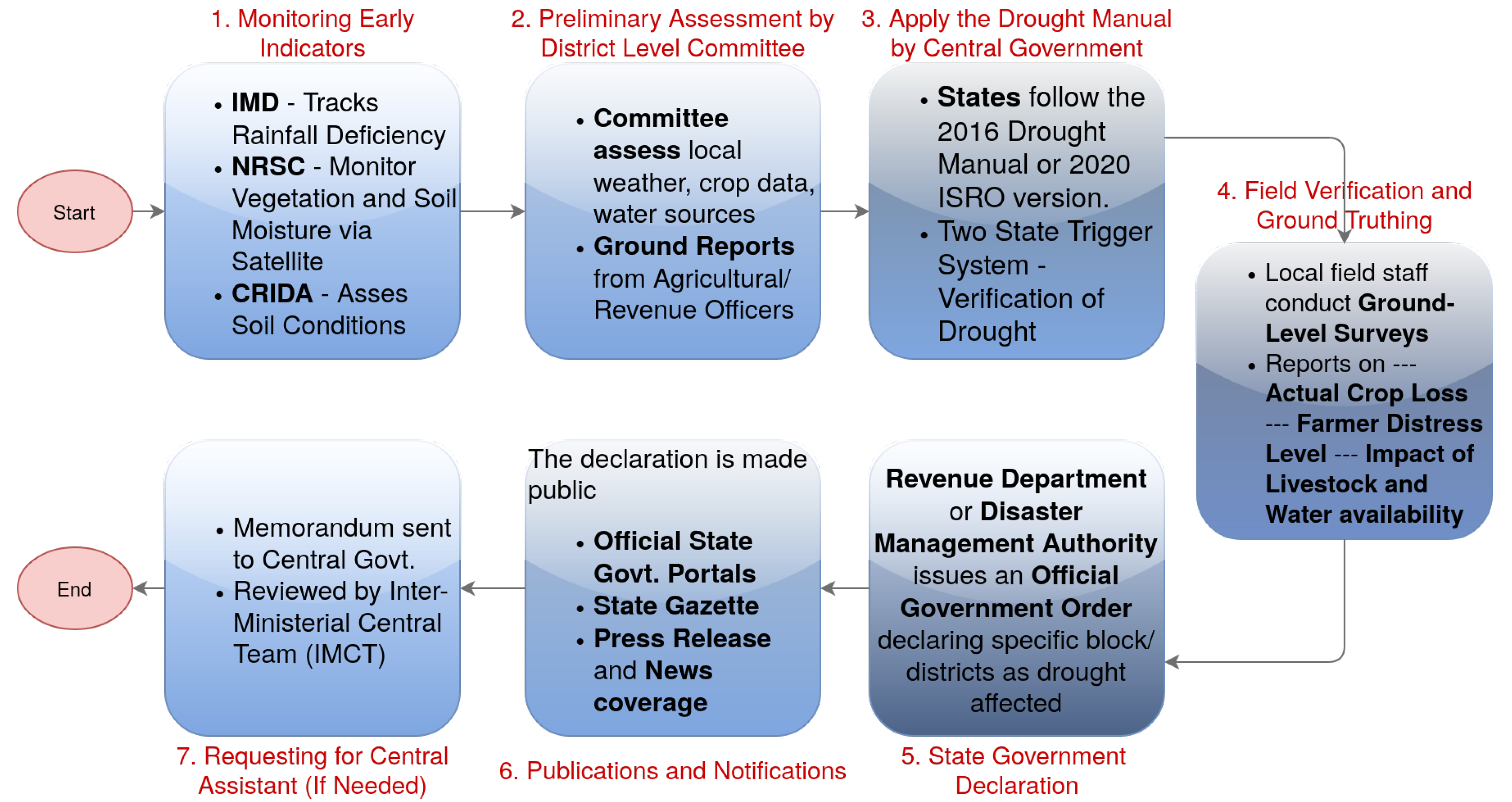

5.1. Drought Declaration Process in India

5.2. Ground Truth Table

5.2.1. Jodhpur

5.2.2. Amravati

5.2.3. Thanjavur

6. Methodology

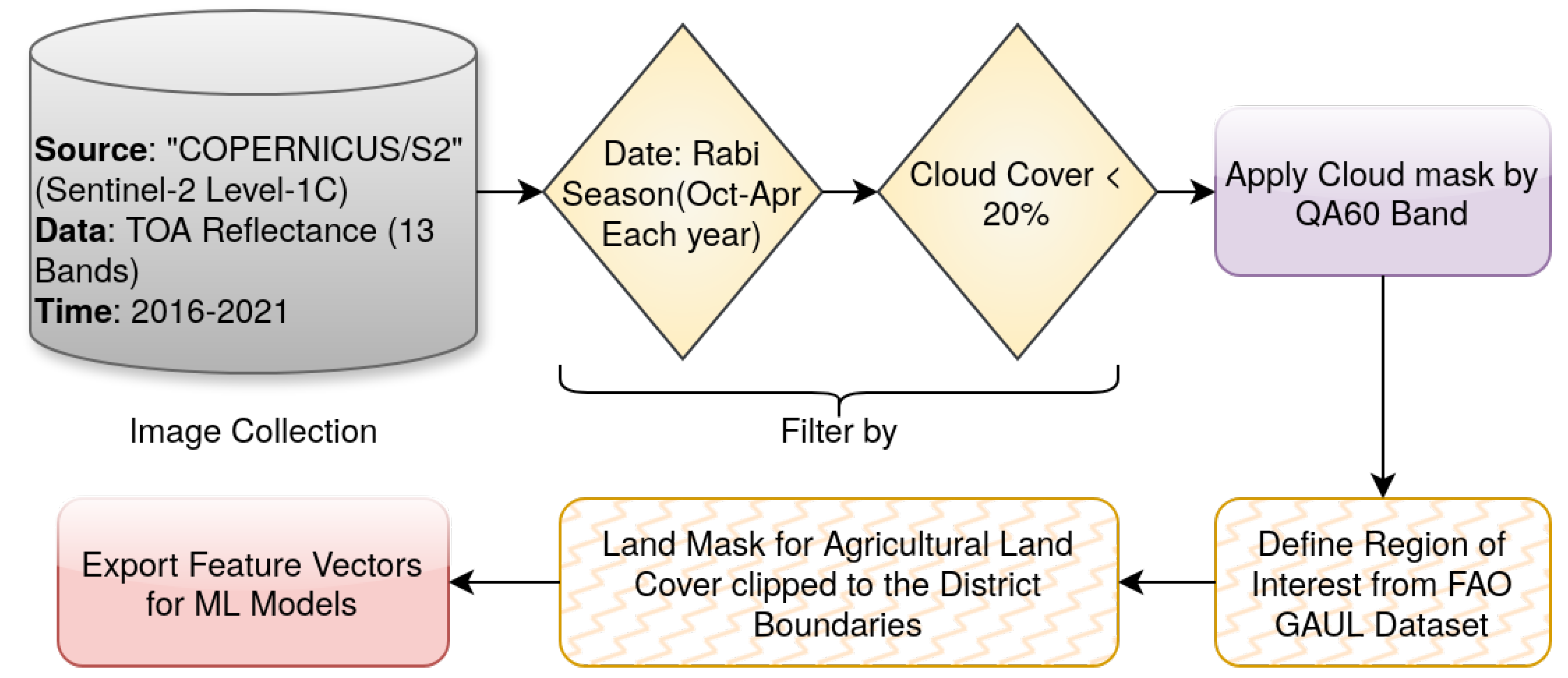

6.1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

6.2. Feature Engineering

6.3. Machine Learning Model Training and Evaluation

6.4. Error Analysis

6.5. Software and Libraries

6.6. Evaluation Metrics

- Accuracy: The percentage of correct predictions. It is defined as .

- Precision: The fraction of true drought predictions among all predicted droughts. It is defined as .

- Recall: The fraction of actual droughts that were correctly identified. It is defined as

7. Results & Discussion

7.1. Model Performance

7.1.1. Before Oversampling

7.1.2. SMOTE

7.1.3. Borderline SMOTE

7.1.4. ADASYN

| Methods/Metrics | Accuracy | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|

| XG Boost | 0.8426 | 0.7859 | 0.8269 |

| Random Forest | 0.8426 | 0.7829 | 0.8324 |

| Bagging Classifier | 0.8328 | 0.7807 | 0.8022 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.7177 | 0.6176 | 0.7500 |

7.2. Error Analysis

7.3. Model Performance (Season Majority-Voting Strategy)

7.4. SHAP Analysis

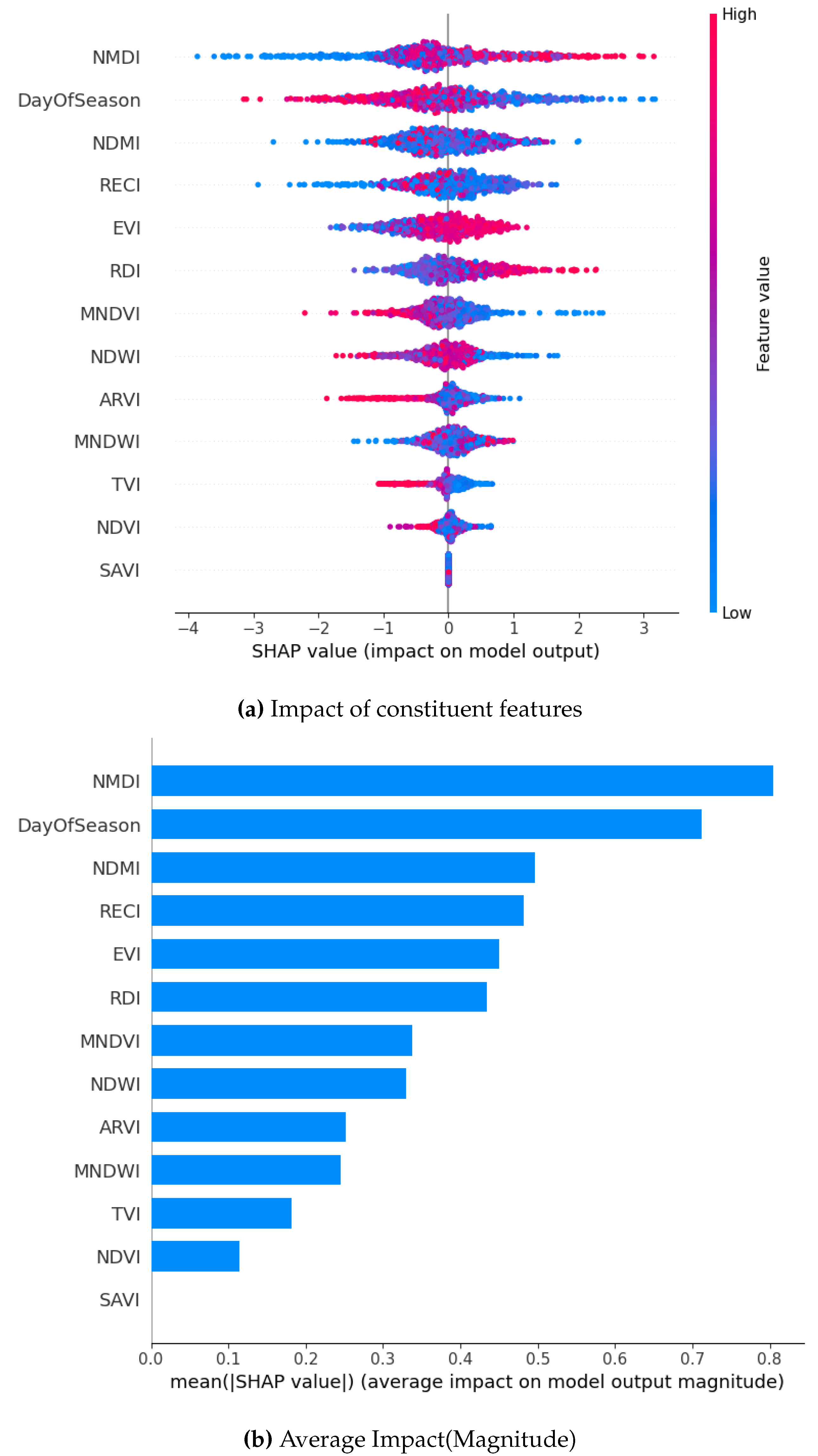

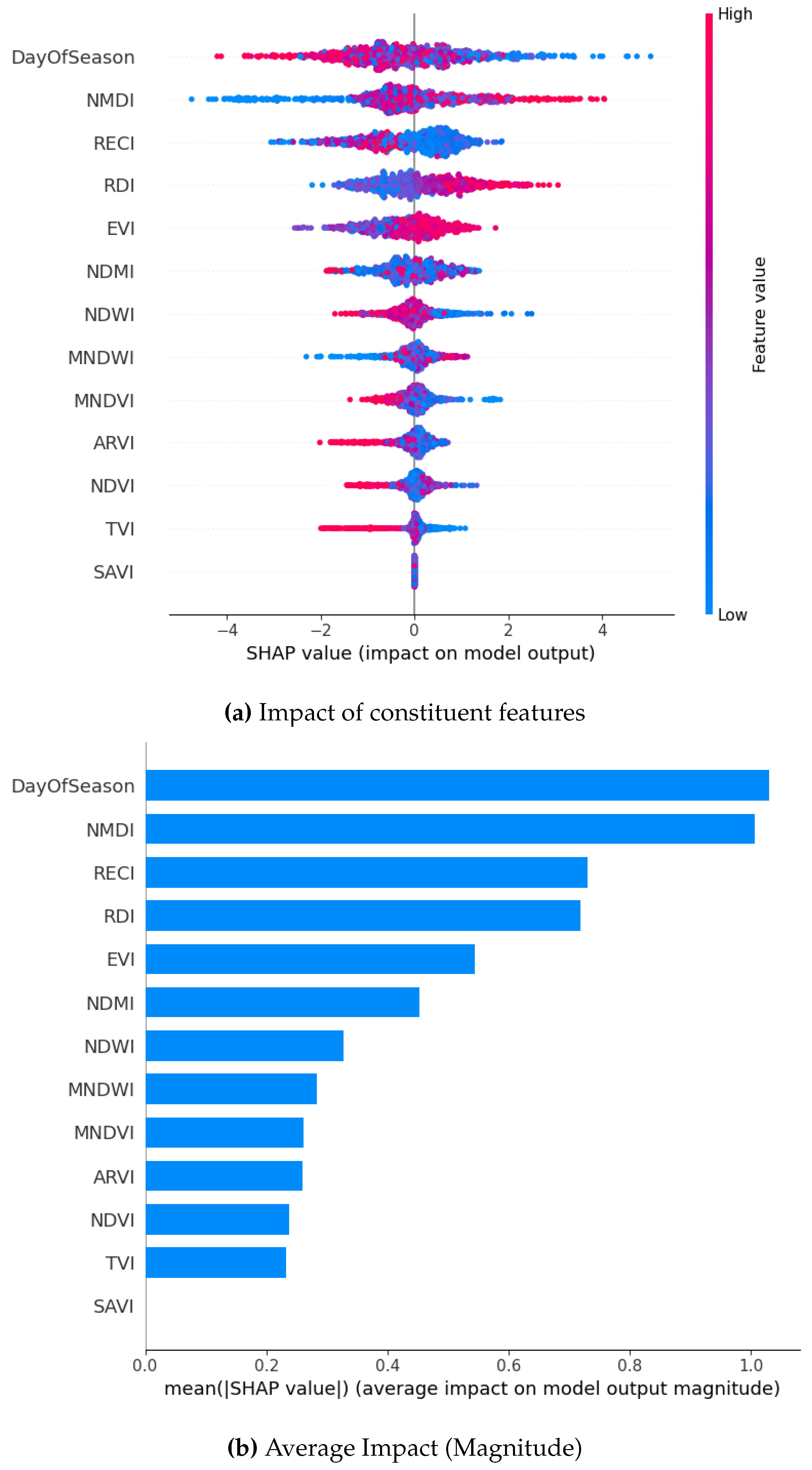

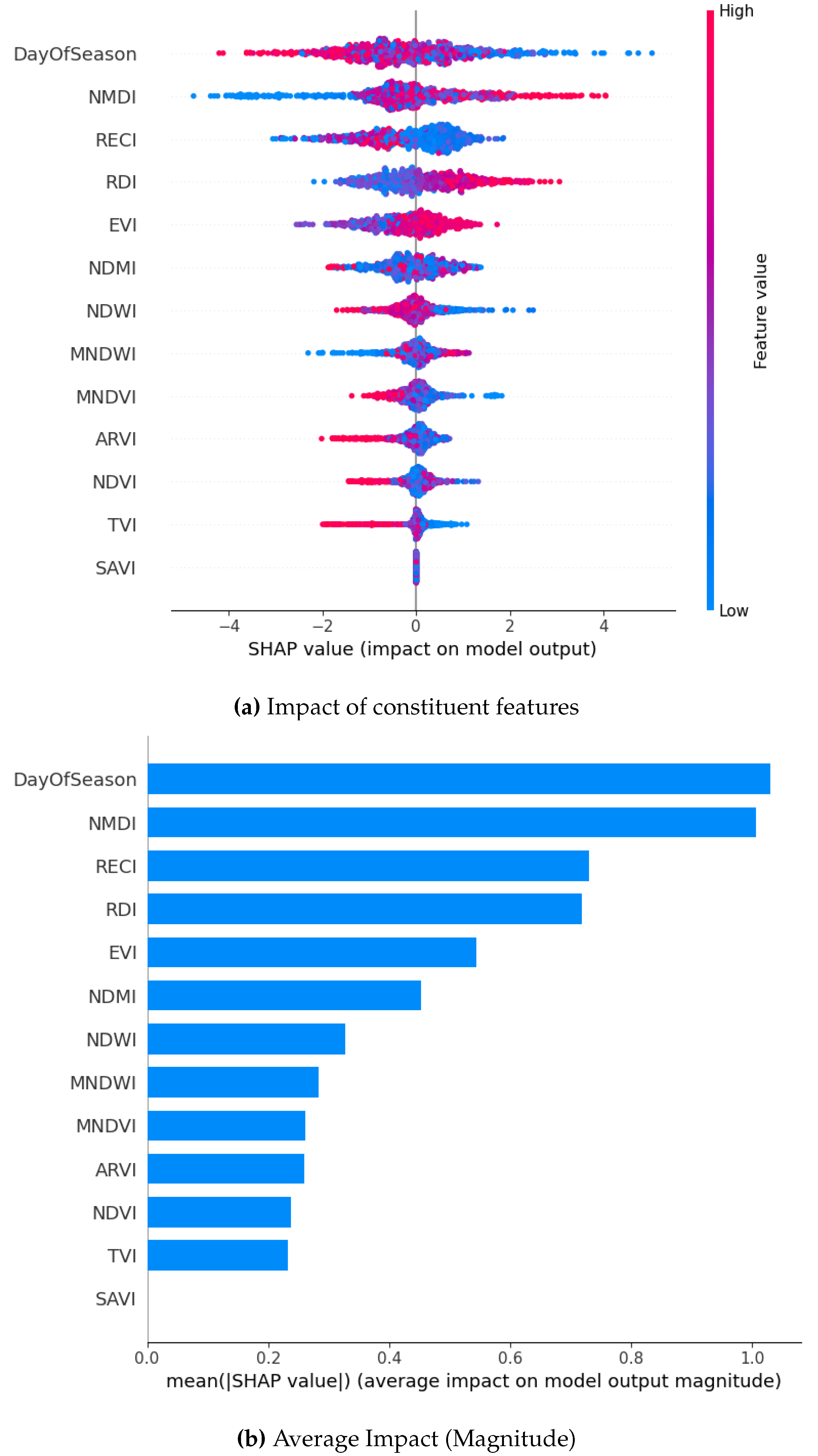

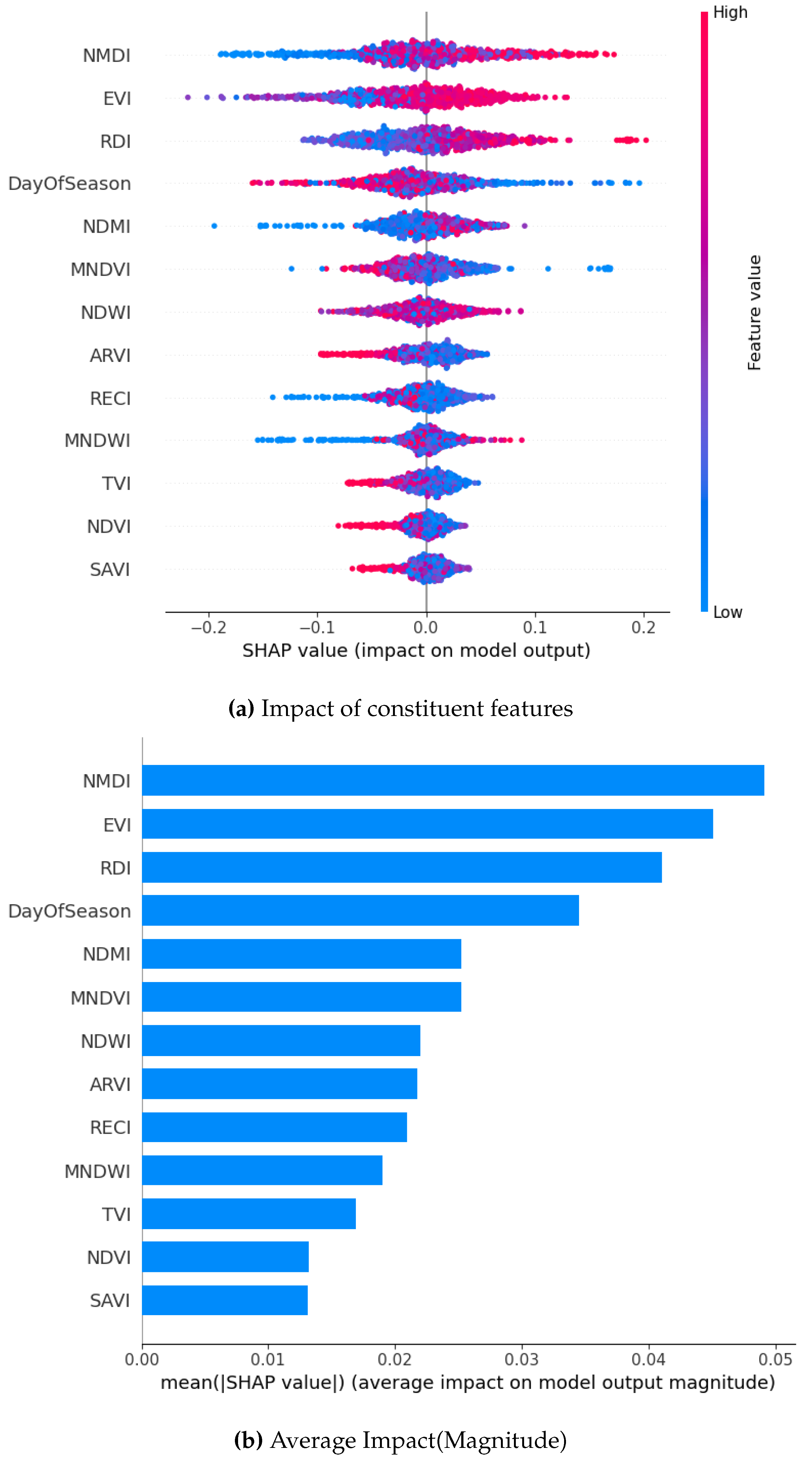

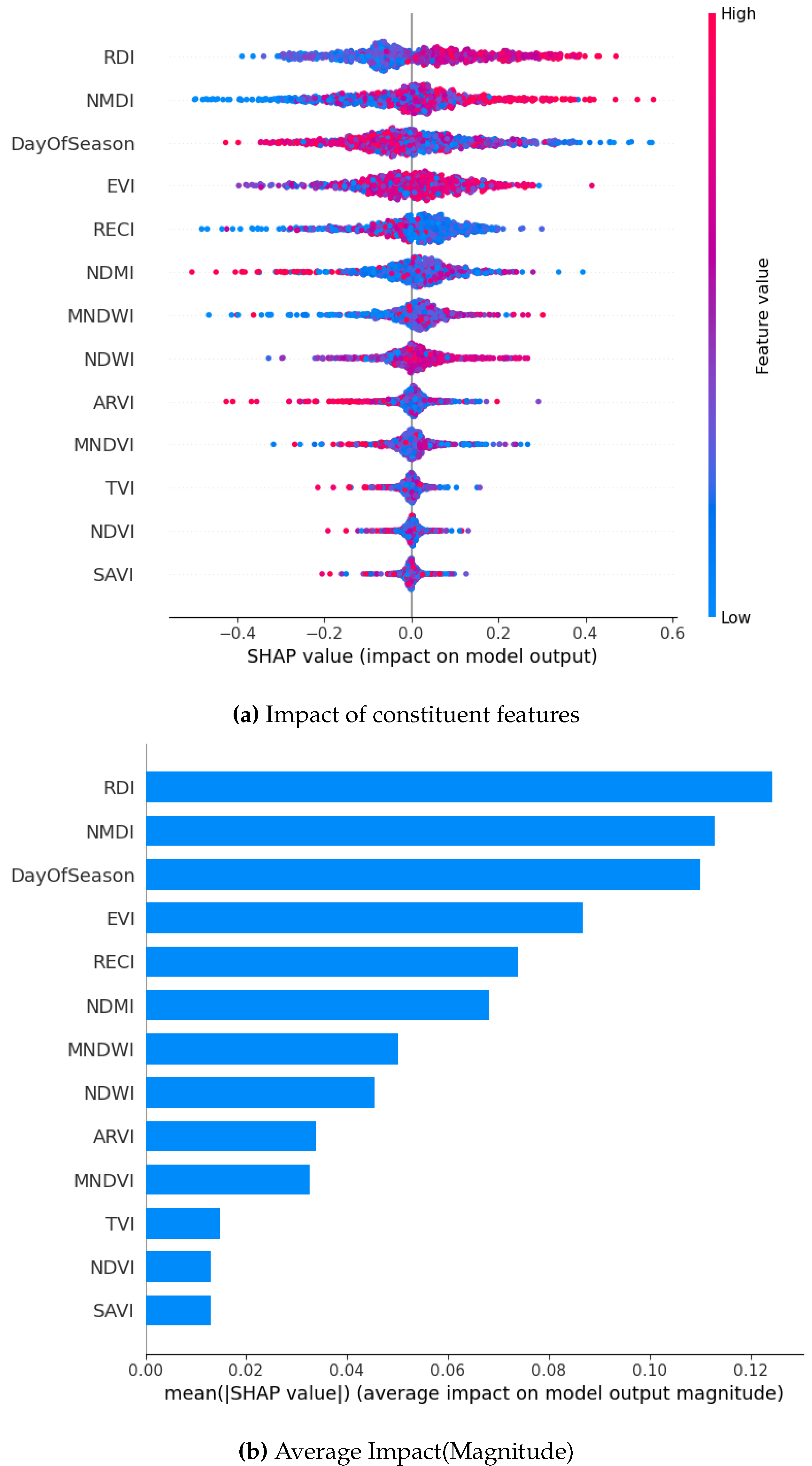

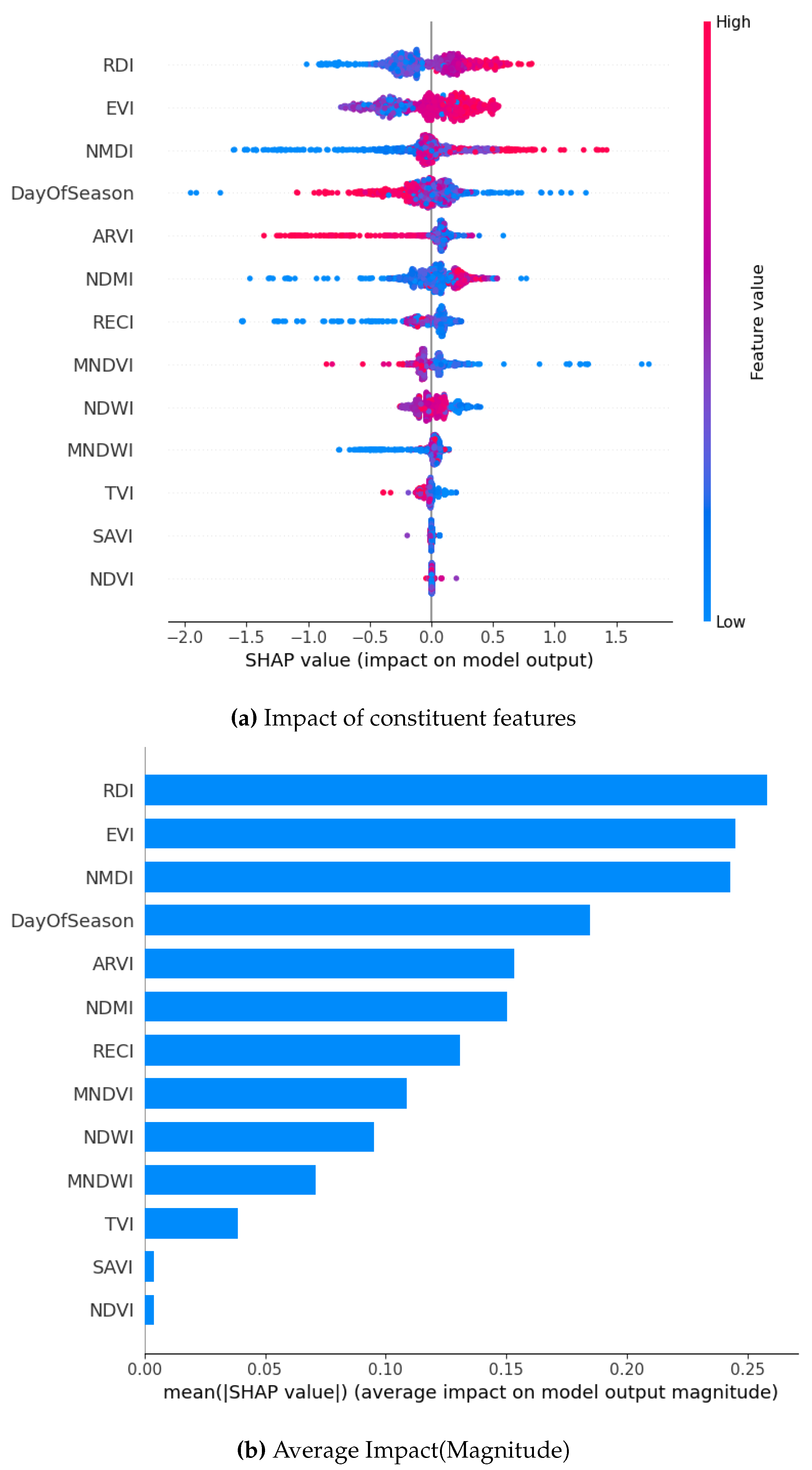

7.4.1. Before Oversampling

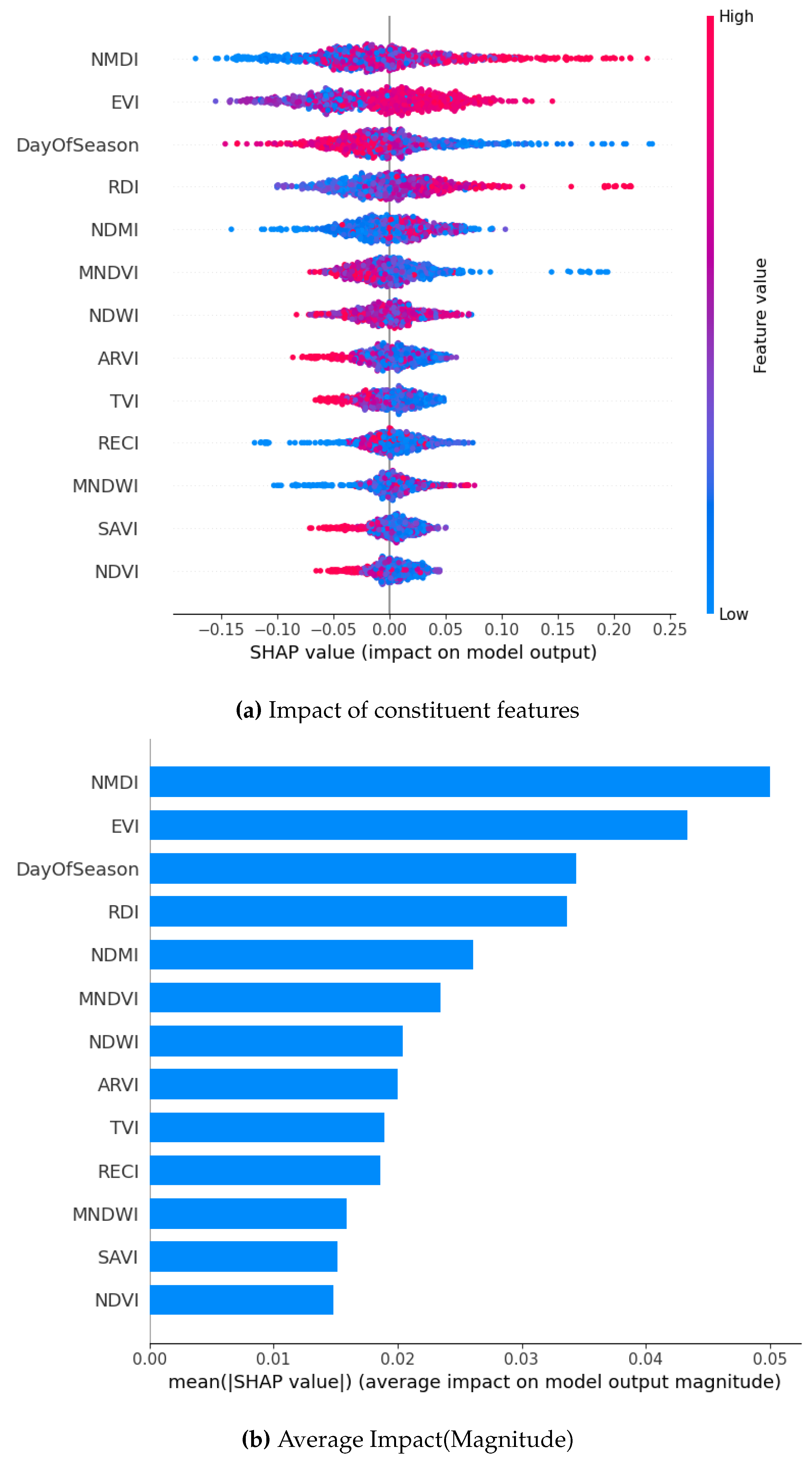

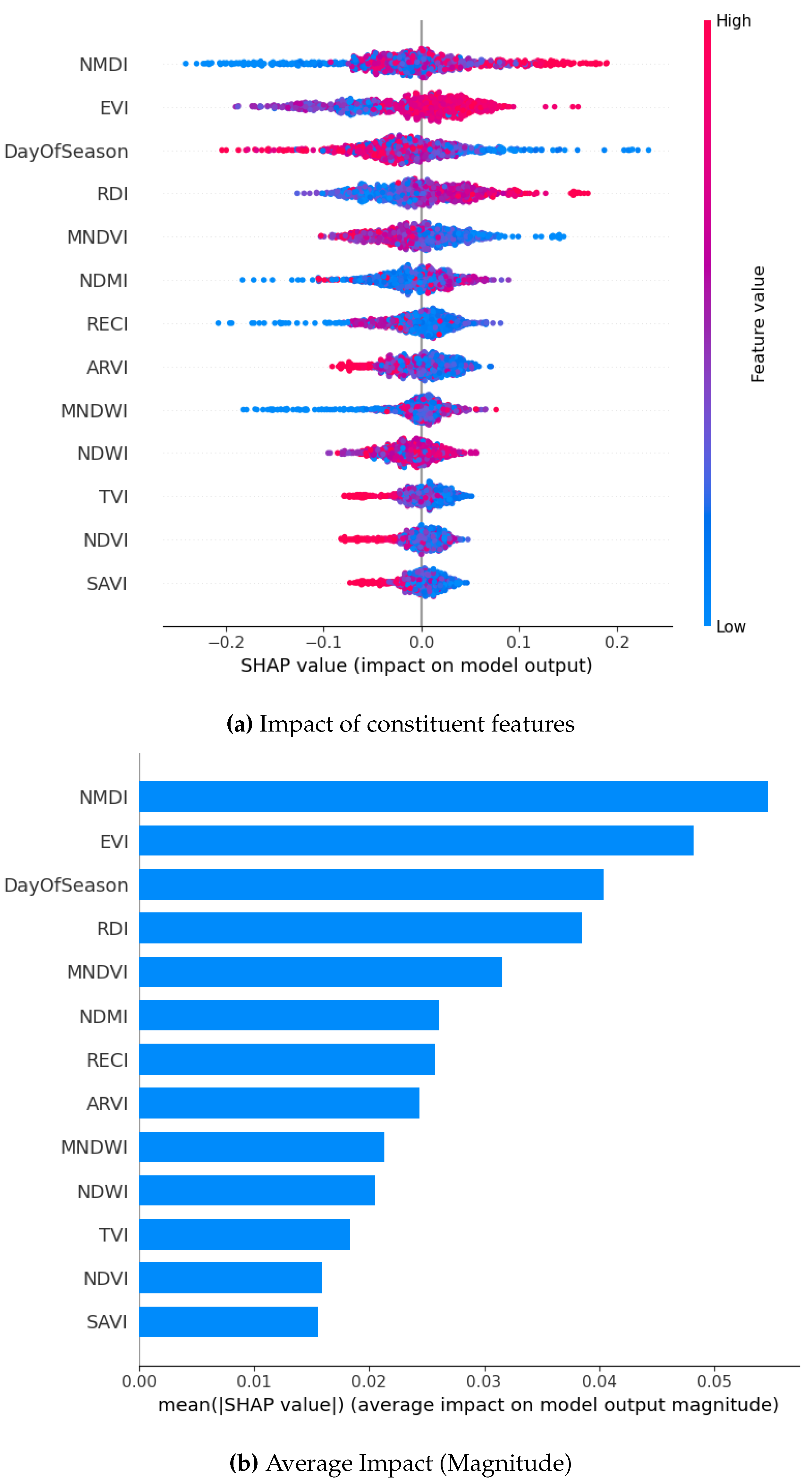

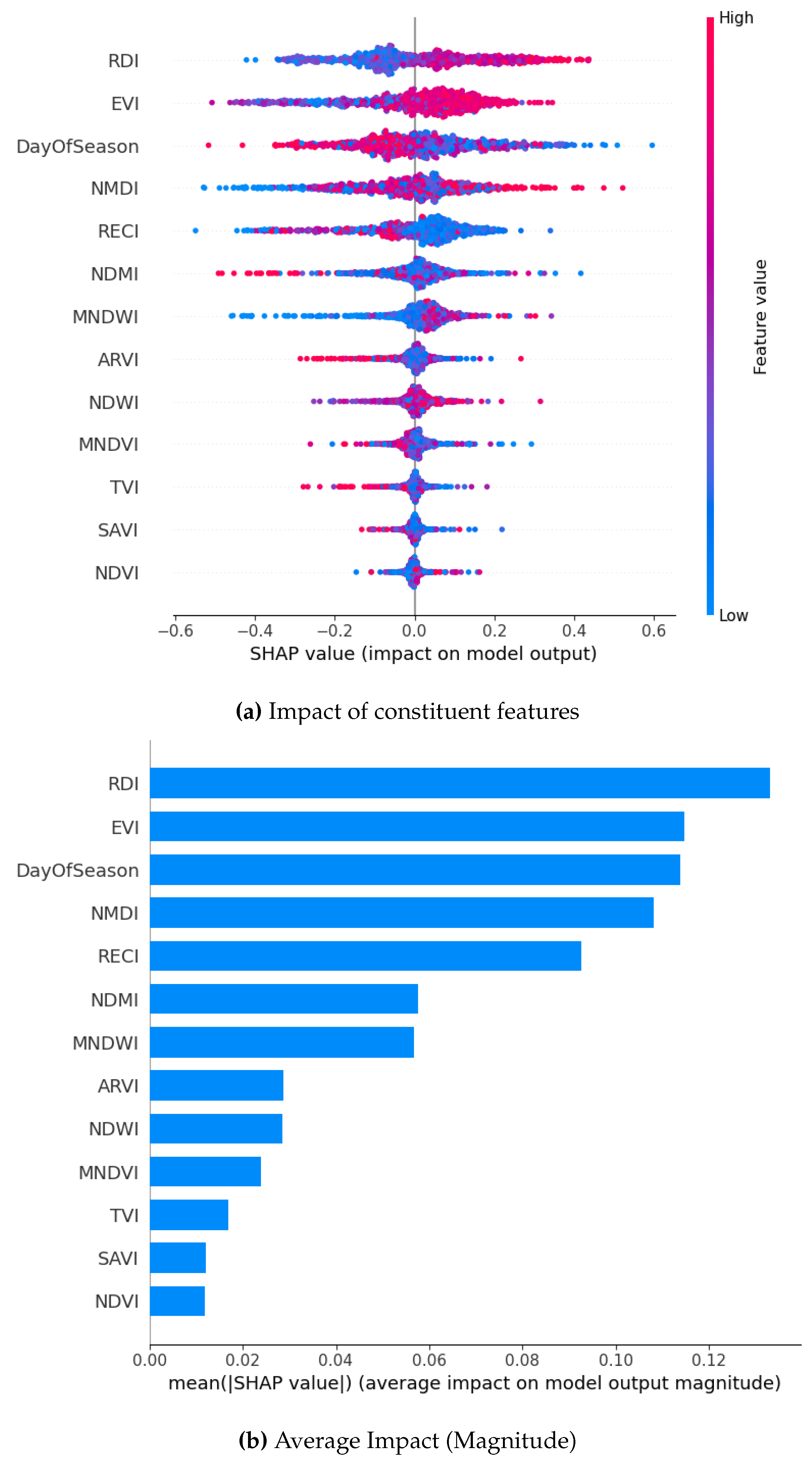

7.4.2. SMOTE

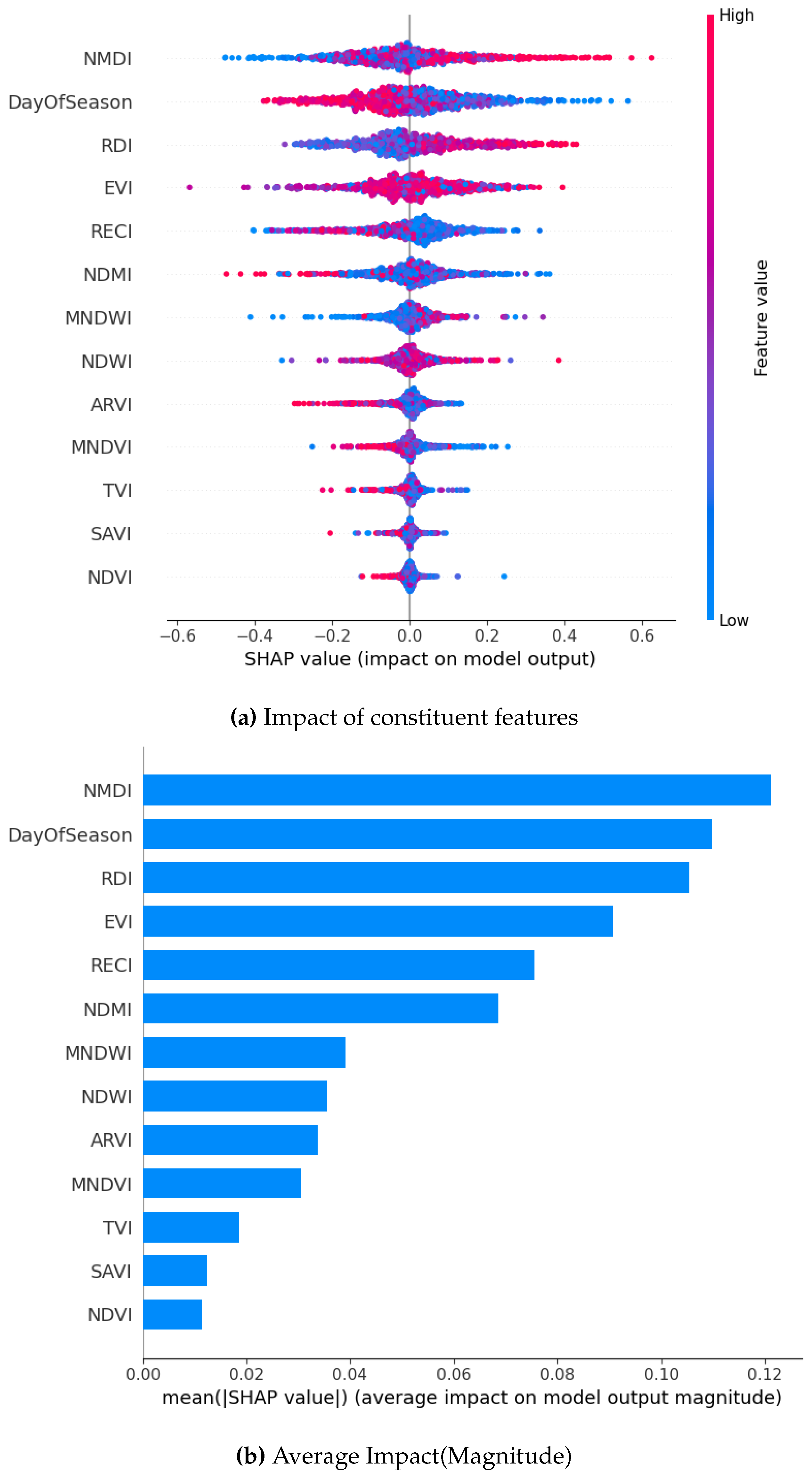

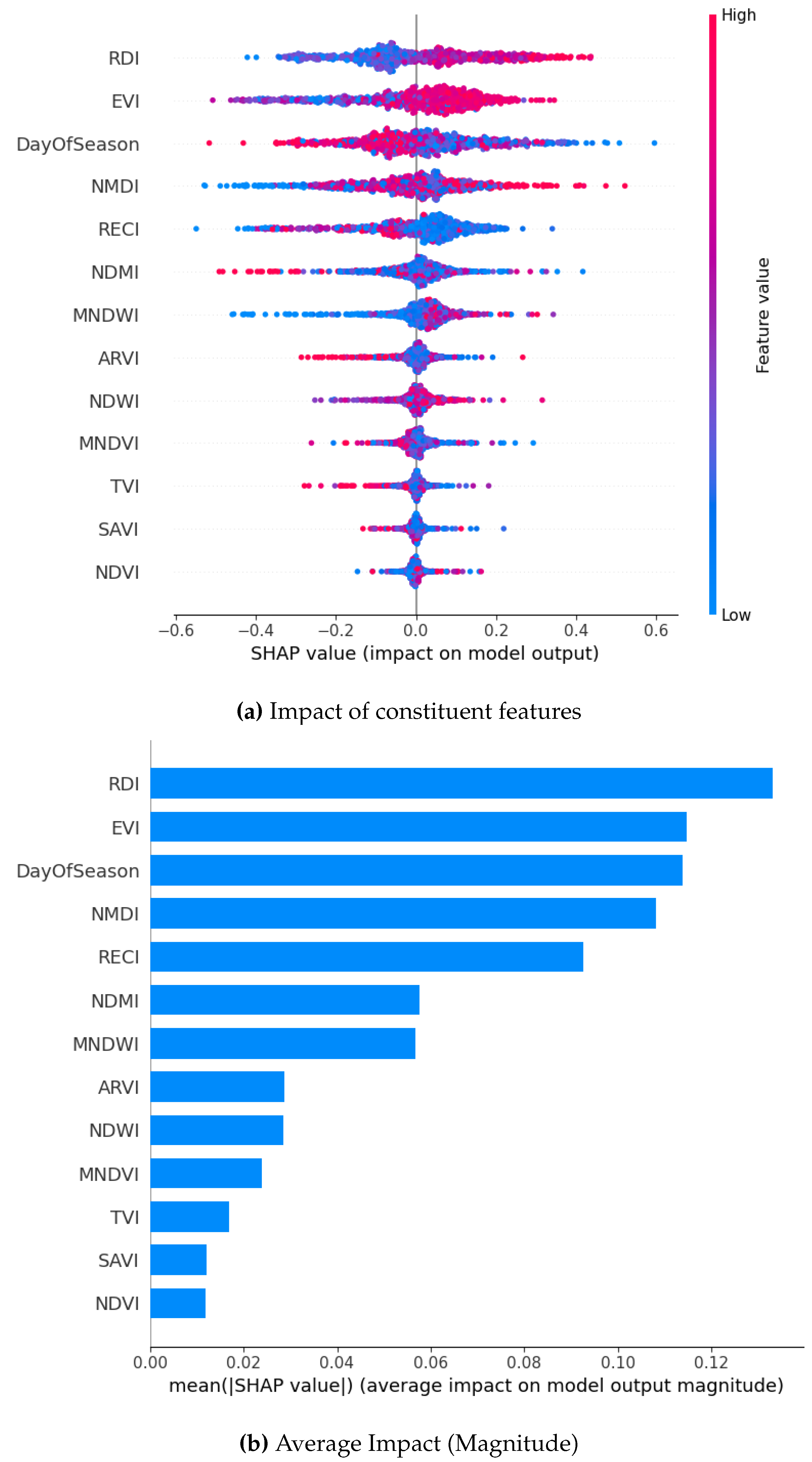

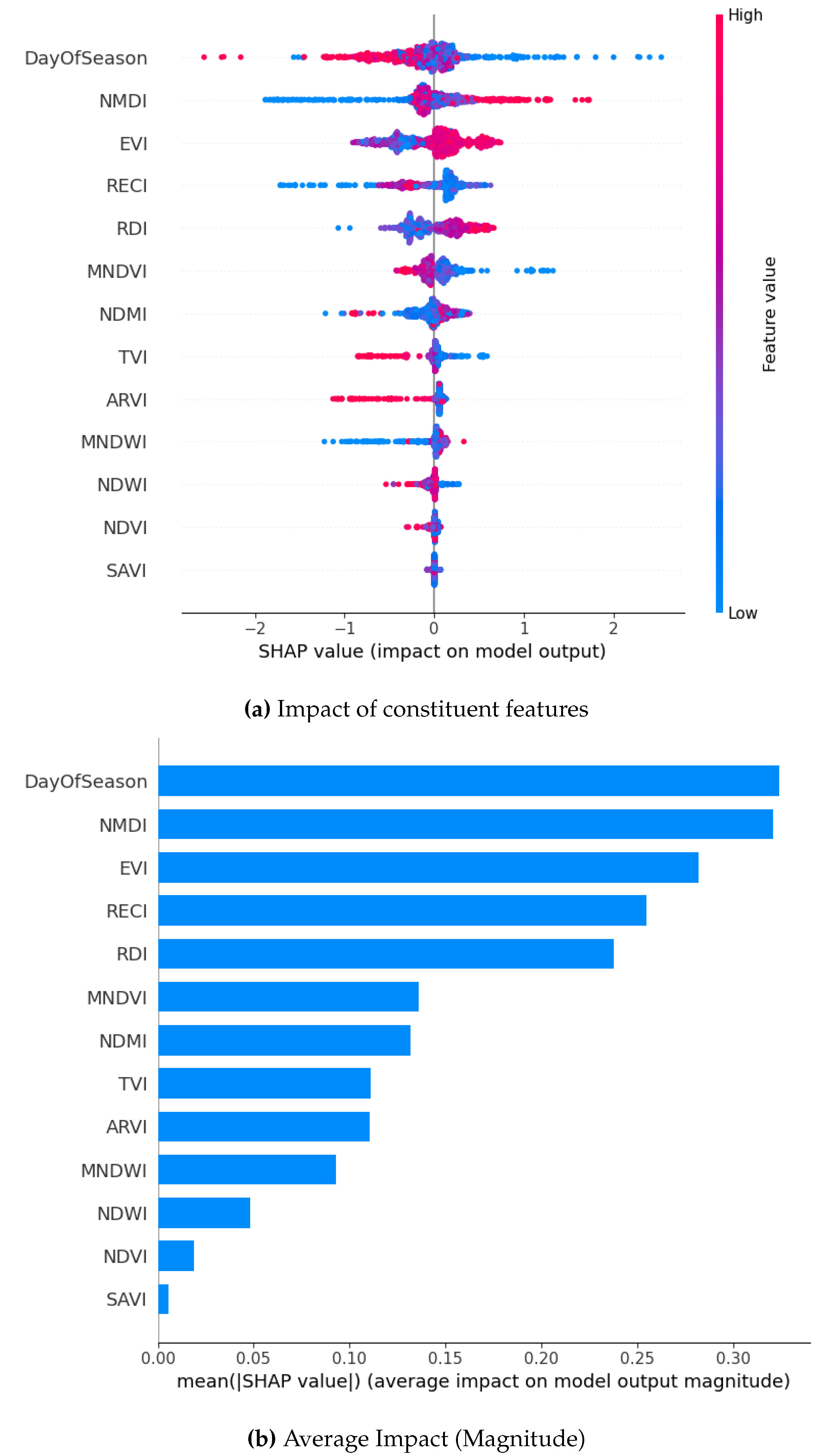

7.4.3. SMOTE Borderline

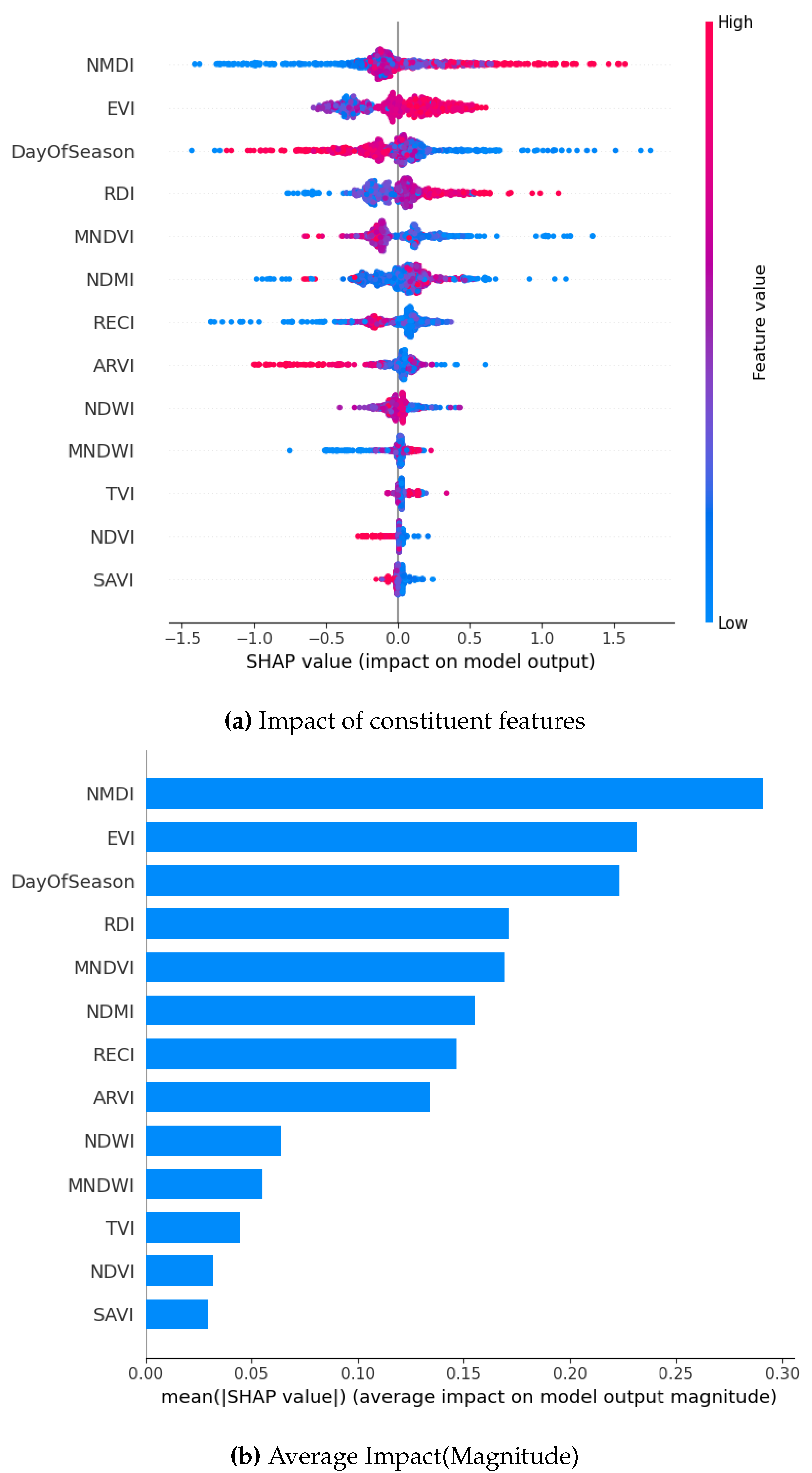

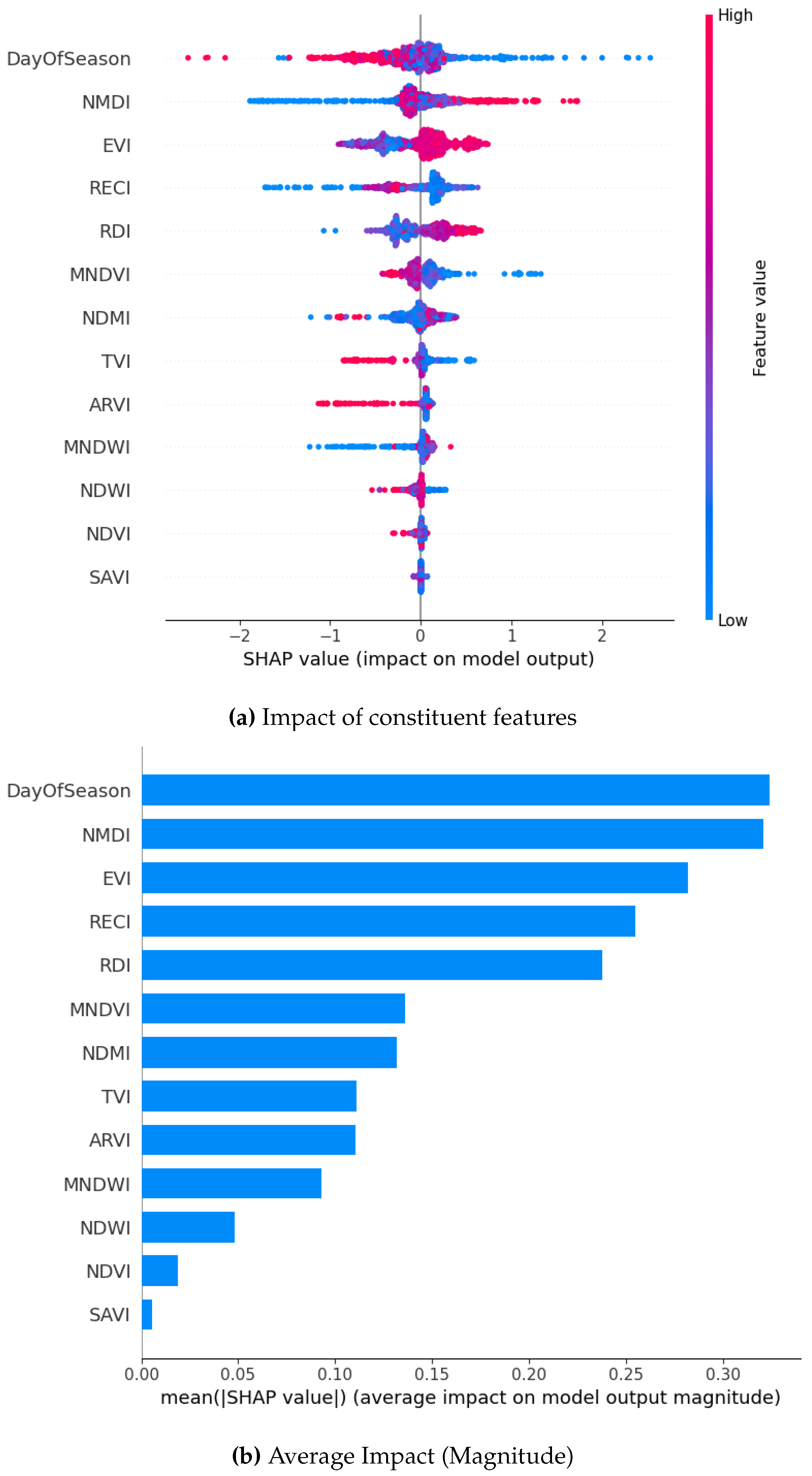

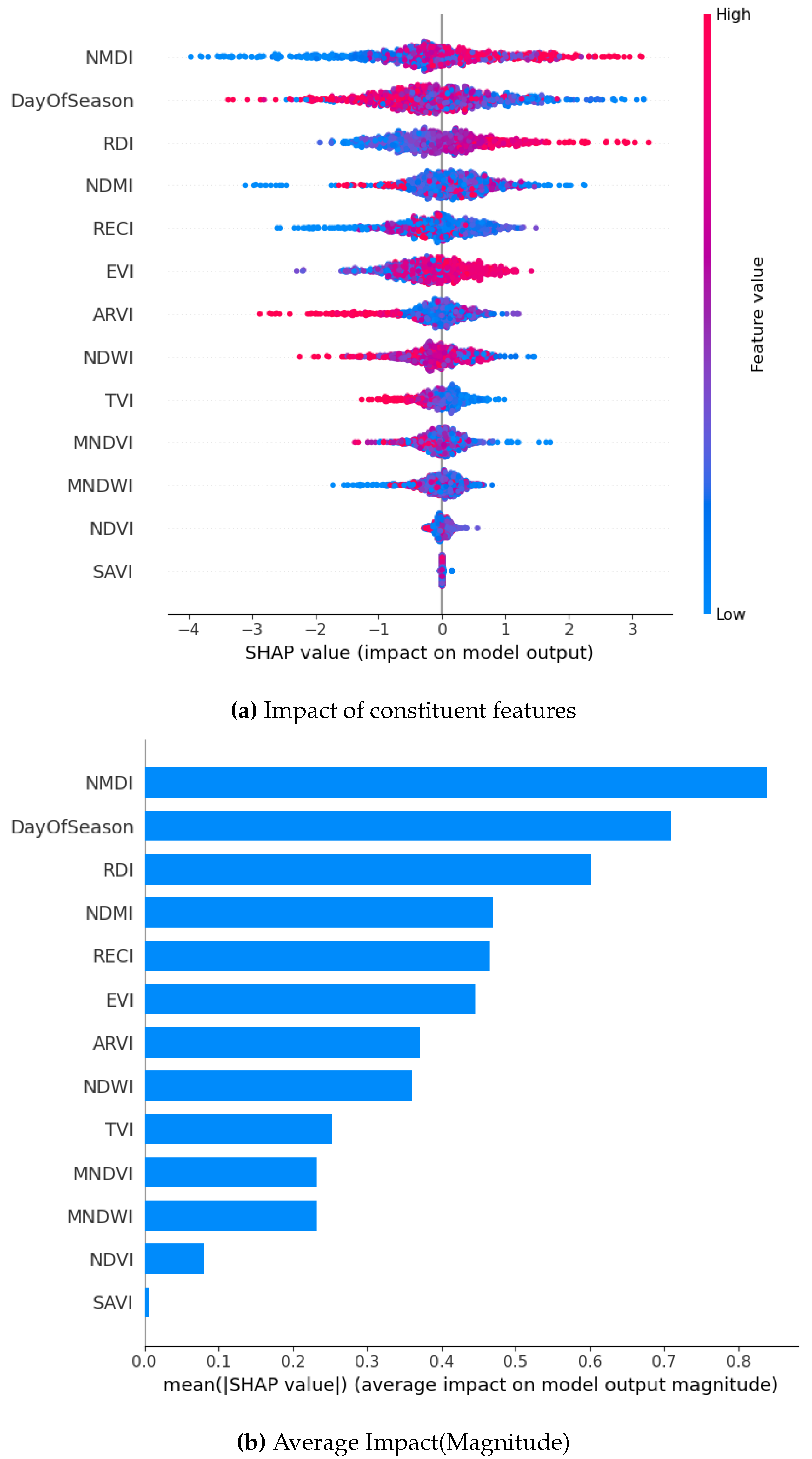

7.4.4. AdaSyn

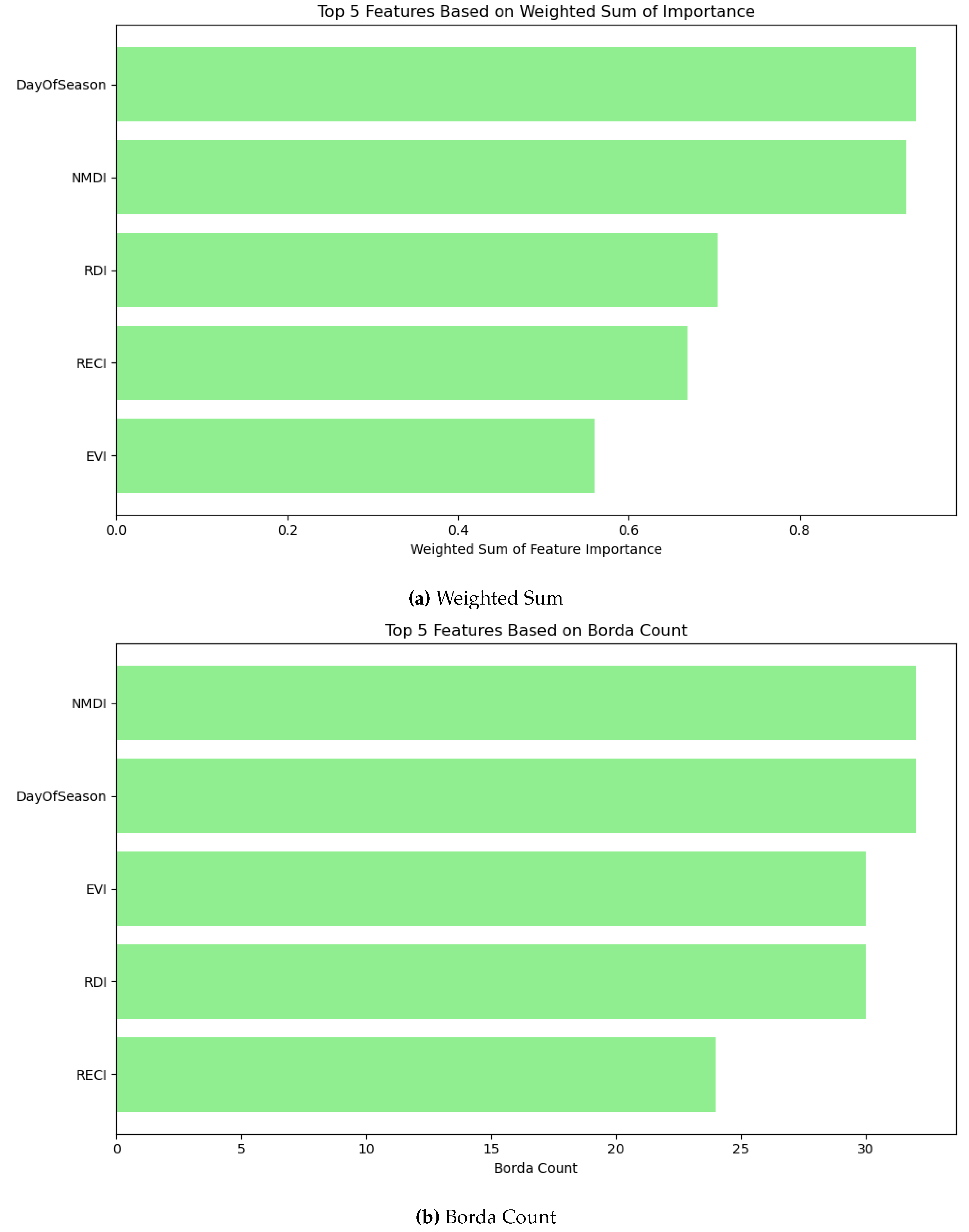

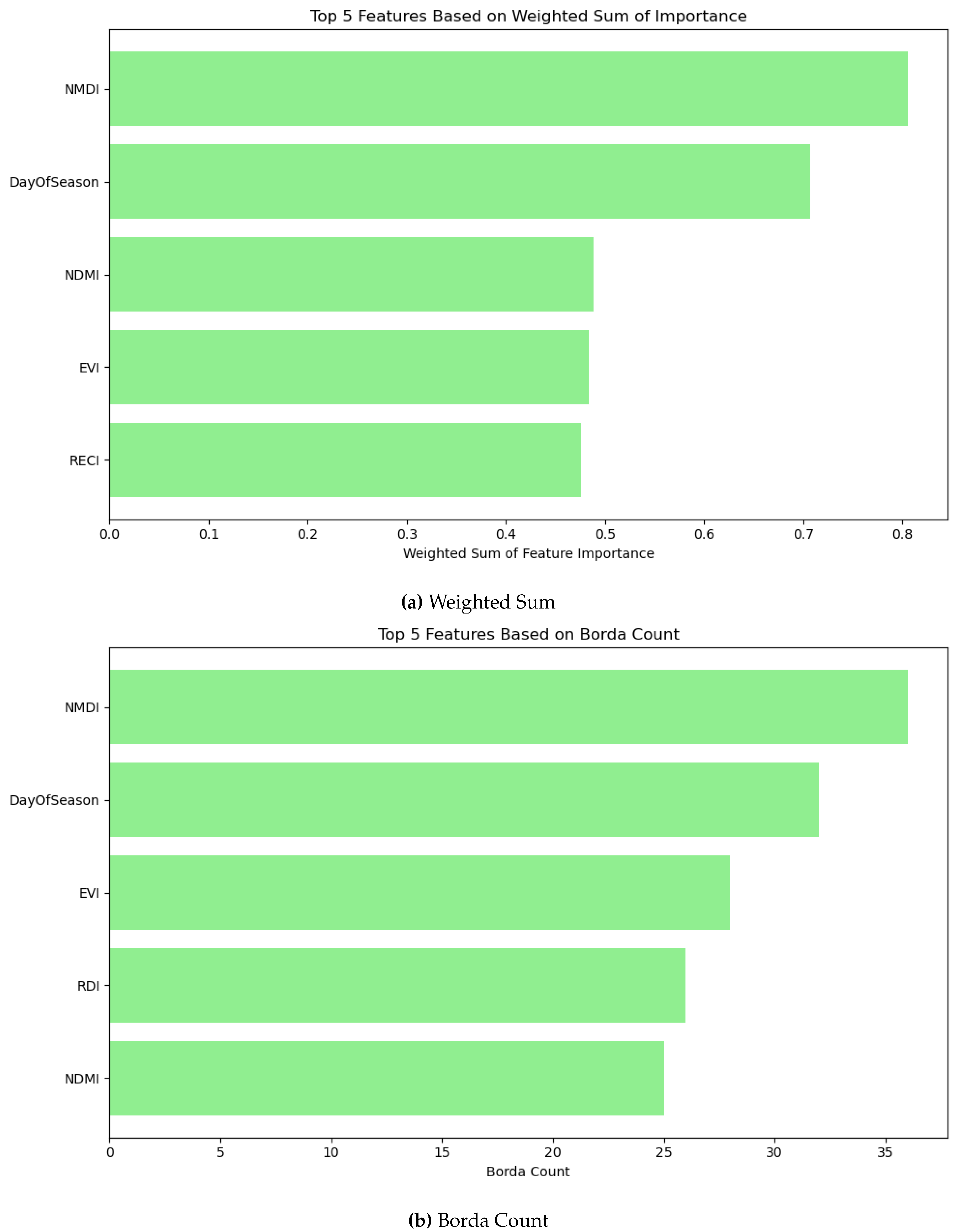

7.5. Model Aggregation for Most Relevant Features

7.5.1. Before Oversampling

7.5.2. SMOTE

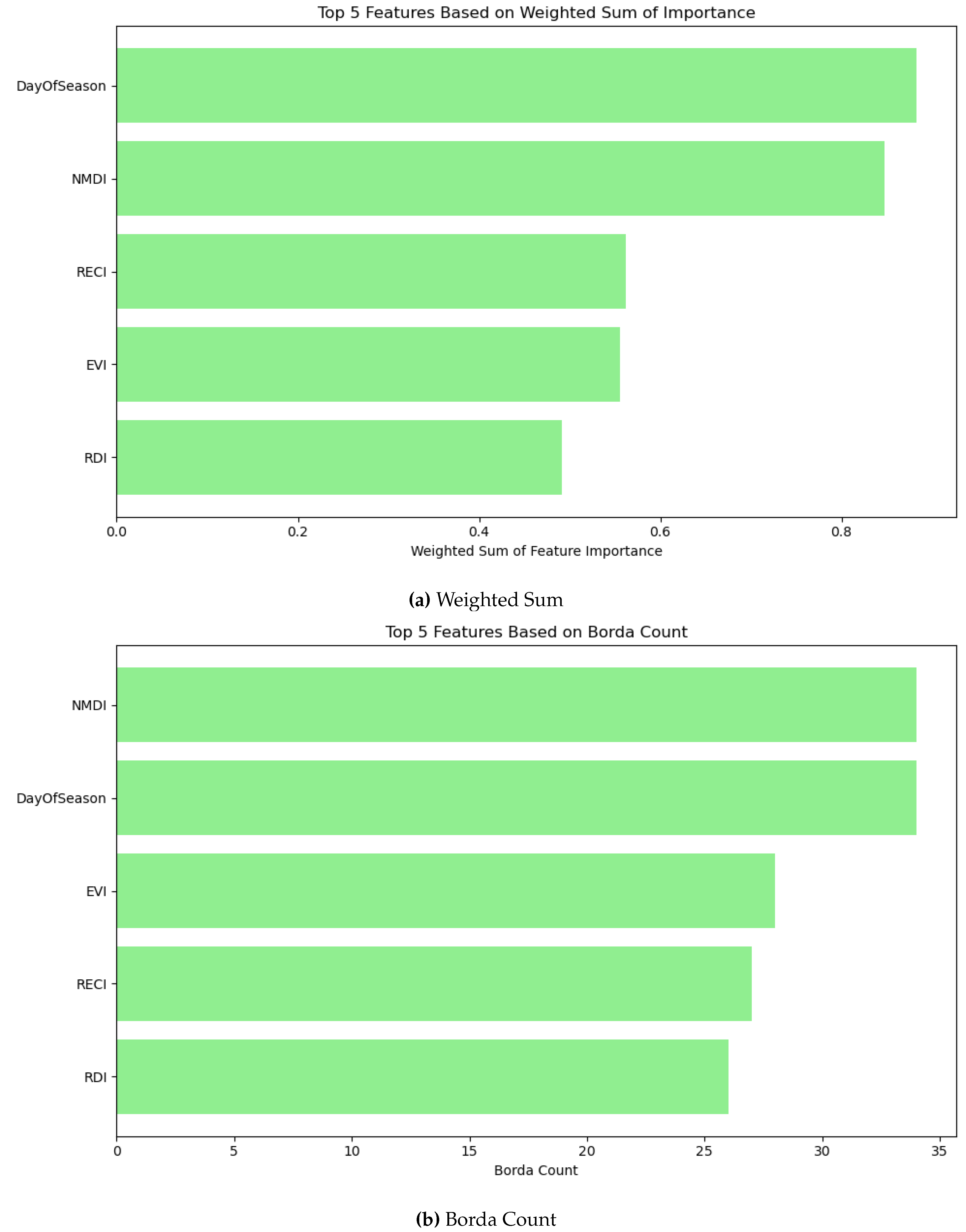

7.5.3. Borderline SMOTE

7.5.4. ADASYN

| XGBoost | Random Forest | Bagging | Gradient Boosting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top 1 | Acc: 0.5657 Prec: 0.4596 Rec: 0.5632 |

Acc: 0.5917 Prec: 0.4866 Rec: 0.5989 |

Acc: 0.5917 Prec: 0.4866 Rec: 0.5989 |

Acc: 0.5907 Prec: 0.4867 Rec: 0.6511 |

| Top 2 | Acc: 0.6938 Prec: 0.5958 Rec: 0.7005 |

Acc: 0.7112 Prec: 0.6184 Rec: 0.7033 |

Acc: 0.6721 Prec: 0.5735 Rec: 0.6648 |

Acc: 0.6308 Prec: 0.5267 Rec: 0.6511 |

| Top 3 | Acc: 0.7687 Prec: 0.6752 Rec: 0.7995 |

Acc: 0.7904 Prec: 0.7050 Rec: 0.8077 |

Acc: 0.7828 Prec: 0.6962 Rec: 0.7995 |

Acc: 0.6504 Prec: 0.5467 Rec: 0.6758 |

| Top 4 | Acc: 0.7709 Prec: 0.6852 Rec: 0.7775 |

Acc: 0.7926 Prec: 0.7235 Rec: 0.7692 |

Acc: 0.7839 Prec: 0.7165 Rec: 0.7500 |

Acc: 0.6786 Prec: 0.5766 Rec: 0.7033 |

| Top 5 | Acc: 0.8230 Prec: 0.7445 Rec: 0.8407 |

Acc: 0.8165 Prec: 0.7456 Rec: 0.8132 |

Acc: 0.8187 Prec: 0.7599 Rec: 0.7912 |

Acc: 0.6960 Prec: 0.5929 Rec: 0.7363 |

| XGBoost | Random Forest | Bagging | Gradient Boosting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top 1 | Acc: 0.5657 Prec: 0.4596 Rec: 0.5632 |

Acc: 0.5917 Prec: 0.4866 Rec: 0.5989 |

Acc: 0.5917 Prec: 0.4866 Rec: 0.5989 |

Acc: 0.5907 Prec: 0.4867 Rec: 0.6511 |

| Top 2 | Acc: 0.6298 Prec: 0.5277 Rec: 0.6016 |

Acc: 0.6406 Prec: 0.5394 Rec: 0.6209 |

Acc: 0.6547 Prec: 0.5553 Rec: 0.6346 |

Acc: 0.6135 Prec: 0.5092 Rec: 0.6099 |

| Top 3 | Acc: 0.7687 Prec: 0.6752 Rec: 0.7995 |

Acc: 0.7980 Prec: 0.7150 Rec: 0.8132 |

Acc: 0.7828 Prec: 0.6962 Rec: 0.7995 |

Acc: 0.6504 Prec: 0.5467 Rec: 0.6758 |

| Top 4 | Acc: 0.7883 Prec: 0.7161 Rec: 0.7692 |

Acc: 0.7937 Prec: 0.7219 Rec: 0.7775 |

Acc: 0.7861 Prec: 0.7169 Rec: 0.7582 |

Acc: 0.6786 Prec: 0.5766 Rec: 0.7033 |

| Top 5 | Acc: 0.8132 Prec: 0.7319 Rec: 0.8324 |

Acc: 0.8165 Prec: 0.7519 Rec: 0.7995 |

Acc: 0.8056 Prec: 0.7354 Rec: 0.7940 |

Acc: 0.7036 Prec: 0.6056 Rec: 0.7170 |

8. Conclusion

Funding

References

- Urban, M.; Berger, C.; Mudau, T.E.; Heckel, K.; Truckenbrodt, J.; Onyango Odipo, V.; Smit, I.P.; Schmullius, C. Surface moisture and vegetation cover analysis for drought monitoring in the southern Kruger National Park using Sentinel-1, Sentinel-2, and Landsat-8. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimeno-Sotelo, L.; Sorí, R.; Nieto, R.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Gimeno, L. Unravelling the origin of the atmospheric moisture deficit that leads to droughts. Nature Water 2024, 2, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AghaKouchak, A.; Farahmand, A.; Melton, F.S.; Teixeira, J.; Anderson, M.C.; Wardlow, B.D.; Hain, C.R. Remote sensing of drought: Progress, challenges and opportunities. Reviews of Geophysics 2015, 53, 452–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hao, Z.; Feng, S.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Hao, F. Agricultural drought prediction in China based on drought propagation and large-scale drivers. Agricultural Water Management 2021, 255, 107028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satapathy, T.; Dietrich, J.; Ramadas, M. Agricultural drought monitoring and early warning at the regional scale using a remote sensing-based combined index. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2024, 196, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorooshian, S.; AghaKouchak, A.; Arkin, P.; Eylander, J.; Foufoula-Georgiou, E.; Harmon, R.; Hendrickx, J.M.; Imam, B.; Kuligowski, R.; Skahill, B.; et al. Advanced concepts on remote sensing of precipitation at multiple scales. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2011, 92, 1353–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.C.; Hain, C.; Wardlow, B.; Pimstein, A.; Mecikalski, J.R.; Kustas, W.P. Evaluation of drought indices based on thermal remote sensing of evapotranspiration over the continental United States. Journal of Climate 2011, 24, 2025–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim Jr, R.R. A review of twentieth-century drought indices used in the United States. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2002, 83, 1149–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Fan, H. Deriving drought indices from MODIS vegetation indices (NDVI/EVI) and Land Surface Temperature (LST): Is data reconstruction necessary? International Journal of applied earth observation and geoinformation 2021, 101, 102352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Brown, J.F.; Verdin, J.P.; Wardlow, B. A five-year analysis of MODIS NDVI and NDWI for grassland drought assessment over the central Great Plains of the United States. Geophysical research letters 2007, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, W.H.; Tadesse, T.; Wardlow, B.D.; Hayes, M.J.; Svoboda, M.D.; Hong, E.M.; Pachepsky, Y.A.; Jang, M.W. Developing the vegetation drought response index for South Korea (VegDRI-SKorea) to assess the vegetation condition during drought events. International journal of remote sensing 2018, 39, 1548–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkash, V.; Singh, S. A review on potential plant-based water stress indicators for vegetable crops. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Fernández, J.; González-Zamora, A.; Sánchez, N.; Gumuzzio, A.; Herrero-Jiménez, C. Satellite soil moisture for agricultural drought monitoring: Assessment of the SMOS derived Soil Water Deficit Index. Remote Sensing of Environment 2016, 177, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.C.; Zolin, C.A.; Sentelhas, P.C.; Hain, C.R.; Semmens, K.; Yilmaz, M.T.; Gao, F.; Otkin, J.A.; Tetrault, R. The Evaporative Stress Index as an indicator of agricultural drought in Brazil: An assessment based on crop yield impacts. Remote Sensing of Environment 2016, 174, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Q.; Zhao, M.; Kimball, J.S.; McDowell, N.G.; Running, S.W. A remotely sensed global terrestrial drought severity index. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2013, 94, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilip, T.; Kumari, M.; Murthy, C.; Neelima, T.; Chakraborty, A.; Devi, M.U. Monitoring early-season agricultural drought using temporal Sentinel-1 SAR-based combined drought index. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2023, 195, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volden, E. New Capabilities in Earth Observation for Agriculture, 2017.

- Varghese, D.; Radulović, M.; Stojković, S.; Crnojević, V. Reviewing the potential of Sentinel-2 in assessing the drought. Remote sensing 2021, 13, 3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Blackburn, G.A.; Onojeghuo, A.O.; Dash, J.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Y.; Atkinson, P.M. Fusion of Landsat 8 OLI and Sentinel-2 MSI data. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2017, 55, 3885–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh Noi, P.; Kappas, M. Comparison of random forest, k-nearest neighbor, and support vector machine classifiers for land cover classification using Sentinel-2 imagery. Sensors 2017, 18, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrant, S.; Selles, A.; Le Page, M.; Mermoz, S.; Gascoin, S.; Bouvet, A.; Ahmed, S.; Kerr, Y.H.; et al. Sentinel-1&2 for near real time cropping pattern monitoring in drought prone areas. application to irrigation water needs in telangana, south-india. International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2019, 42, 285–292. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Ren, L.; Teuling, A.J.; Zhu, Y.; Wei, L.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, S.; Yang, X.; Fang, X.; et al. Analysis of flash droughts in China using machine learning. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2022, 26, 3241–3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Kaur, L.; Kaur, G. Drought stress detection technique for wheat crop using machine learning. PeerJ Computer Science 2023, 9, e1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, A.; Jalali, M.; He, H.; Al-Ansari, N.; Elbeltagi, A.; Alsafadi, K.; Abdo, H.G.; Sammen, S.S.; Gyasi-Agyei, Y.; Rodrigo-Comino, J. Estimation of SPEI meteorological drought using machine learning algorithms. IEEe Access 2021, 9, 65503–65523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriram, K.; Suresh, K. Machine learning perspective for predicting agricultural droughts using Naïve Bayes algorithm. Middle-East J Sci Res 2016, 24, 178–184. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.S.; Sohn, E.; Park, J.D.; Jang, J.D. Estimation of soil moisture using deep learning based on satellite data: A case study of South Korea. GIScience & Remote Sensing 2019, 56, 43–67. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, P.; Wang, B.; Li Liu, D.; Yu, Q. Machine learning-based integration of remotely-sensed drought factors can improve the estimation of agricultural drought in South-Eastern Australia. Agricultural Systems 2019, 173, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodhan, F.A.; Zhang, J.; Hasan, S.S.; Sharma, T.P.P.; Mohana, H.P. A review of machine learning methods for drought hazard monitoring and forecasting: Current research trends, challenges, and future research directions. Environmental modelling & software 2022, 149, 105327. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, D.; Ungar, L. Generalized SHAP: Generating multiple types of explanations in machine learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.07155. [Google Scholar]

- Saari, D.G. Selecting a voting method: the case for the Borda count. Constitutional Political Economy 2023, 34, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, H.; Quinn, N.; Horswell, M.; White, P. Assessing vegetation response to soil moisture fluctuation under extreme drought using sentinel-2. Water 2018, 10, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.; Justice, C.; Van Leeuwen, W. MODIS vegetation index (MOD13). Algorithm theoretical basis document 1999, 3, 295–309. [Google Scholar]

- Jopia, A.; Zambrano, F.; Pérez-Martínez, W.; Vidal-Páez, P.; Molina, J.; De la Hoz Mardones, F. Time-series of vegetation indices (VNIR/SWIR) derived from Sentinel-2 (A/B) to assess turgor pressure in kiwifruit. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2020, 9, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Huete, A.R.; Didan, K.; Miura, T. Development of a two-band enhanced vegetation index without a blue band. Remote sensing of Environment 2008, 112, 3833–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentinel Hub. Atmospherically Resistant Vegetation Index (ARVI). Available online: https://custom-scripts.sentinel-hub.com/sentinel-2/arvi/ (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Marshall, G.; Zhou, X. Drought detection in semi-arid regions using remote sensing of vegetation indices and drought indices. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2004. 2004 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium. IEEE; 2004; Vol. 3, pp. 1555–1558. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, Y.J.; Tanre, D. Atmospherically resistant vegetation index (ARVI) for EOS-MODIS. IEEE transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 1992, 30, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Javed, N.; Faisal, M.; Sadia, H. A framework for smart agriculture system to monitor the crop stress and drought stress using sentinel-2 satellite image. In Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence: Advances and Applications: ICAIAA 2022; Springer, 2023; pp. 345–361. [Google Scholar]

- McFeeters, S.K. The use of the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) in the delineation of open water features. International journal of remote sensing 1996, 17, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.R. A soil-adjusted vegetation index (SAVI). Remote sensing of environment 1988, 25, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Li, J.; Cao, L.; Liu, Y.; Jin, S.; Zhao, B. Evaluation of vegetation index-based curve fitting models for accurate classification of salt marsh vegetation using sentinel-2 time-series. Sensors 2020, 20, 5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nellis, M.D.; Briggs, J.M. Transformed vegetation index for measuring spatial variation in drought impacted biomass on Konza Prairie, Kansas. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science (1903) 1992, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Shi, X.; Yu, D.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, Z. Estimating models of vegetation fractional coverage based on remote sensing images at different radiometric correction levels. Frontiers of Forestry in China 2009, 4, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strashok, O.; Ziemiańska, M.; Strashok, V. Evaluation and Correlation of Sentinel-2 NDVI and NDMI in Kyiv (2017–2021). Journal of Ecological Engineering 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentinel Hub. Normalized Difference Moisture Index (NDMI). https://custom-scripts.sentinel-hub.com/sentinel-2/ndmi/, 2024. [Accessed: 27-Jan-2024].

- Wang, L.; Qu, J.J. NMDI: A normalized multi-band drought index for monitoring soil and vegetation moisture with satellite remote sensing. Geophysical Research Letters 2007, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.w.; Chen, H.l. The Application of Modified Normalized Difference Water Index (MNDWI) by Leaf Area Index in the Retrieval of Regional Drought Monitoring. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2015, 40, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. Modification of normalised difference water index (NDWI) to enhance open water features in remotely sensed imagery. International journal of remote sensing 2006, 27, 3025–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurgens, C. The modified normalized difference vegetation index (mNDVI) a new index to determine frost damages in agriculture based on Landsat TM data. International Journal of Remote Sensing 1997, 18, 3583–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Wang, L.; Gao, M.; Zhu, X.; Feng, W.; Li, N. Ratio Drought Index (RDI): A soil moisture index based on new NIR-red triangle space. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2024, 45, 6976–6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EOS Data Analytics. Chlorophyll Index: Overview, Calculation, and Application. https://eos.com/make-an-analysis/chlorophyll-index/, 2024. [Accessed: 27-Jan-2024].

- Sentinel Hub. Red-edge Chlorophyll Index (RECI). https://custom-scripts.sentinel-hub.com/custom-scripts/sentinel-2/chl_rededge/, 2024. [Accessed: 27-Jan-2024].

- Jafarzadeh, H.; Mahdianpari, M.; Gill, E.; Mohammadimanesh, F.; Homayouni, S. Bagging and boosting ensemble classifiers for classification of multispectral, hyperspectral and PolSAR data: a comparative evaluation. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Ahmad, M.N.; Javed, A. Comparison of Random Forest and XGBoost Classifiers Using Integrated Optical and SAR Features for Mapping Urban Impervious Surface. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Annals of statistics 2001, pp. 1189–1232.

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, 2016, pp.

- Breiman, L. Bagging predictors. Machine learning 1996, 24, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapley, L.S. A value for n-person games. Contribution to the Theory of Games 1953, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2017, NIPS’17, p.

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.I. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nature Machine Intelligence 2020, 2, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacuit, E. Voting methods 2011.

- Churchman, C.W.; Ackoff, R.L. An approximate measure of value. Journal of the Operations Research Society of America 1954, 2, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. Journal of artificial intelligence research 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Wang, W.Y.; Mao, B.H. Borderline-SMOTE: a new over-sampling method in imbalanced data sets learning. In Proceedings of the International conference on intelligent computing. Springer; 2005; pp. 878–887. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Bai, Y.; Garcia, E.A.; Li, S. ADASYN: Adaptive synthetic sampling approach for imbalanced learning. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE international joint conference on neural networks (IEEE world congress on computational intelligence). Ieee; 2008; pp. 1322–1328. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAO Global Administrative Unit Layers (GAUL) 2015. http://www.fao.org/geospatial/gb/en/products/gaul/index.html. [Accessed: 27-Jan-2024].

- Copernicus. Copernicus Global Land Cover. https://land.copernicus.eu/global/lc. [Accessed: 27-Jan-2024].

- (ISRO), I.S.R.O. Drought Assessment Using Remote Sensing and GIS: Drought Manual 2020. Technical report, National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC), ISRO, 2020.

- (ISRO), I.S.R.O. Agri-DSS Help Manual. Technical report, National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC), ISRO, 2020.

- Mishra, V.; Singh, M.; Ghosh, S.; et al. Monitoring Agricultural Drought in India Using Multisource Remote Sensing Indicators. Environmental Challenges 2021, 4, 100021. [Google Scholar]

- The Hindu. 19 Districts in Rajasthan Drought Hit. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/19-districts-in-rajasthan-droughthit/article8491809.ece, 2016. Accessed: 2025-02-07.

- Factly. 266 Districts in 11 Different States Declared Drought-Affected (2015-16). https://factly.in/266-districts-11-different-states-drought-affected-2015-16/, 2016. Accessed: 2025-02-07.

- Parliament of India. Drought Fund Allocation Status (2017). https://sansad.in/getFile/loksabhaquestions/annex/14/AU4057.pdf?source=pqals, 2017. Accessed: 2025-02-07.

- Firstpost Editor. Drought in Rajasthan: Over Rs 7000 Crore Spent on Projects But Not Much Water Has Flown Through Western Region. https://www.firstpost.com/india/drought-in-rajasthan-over-rs-7000-crore-spent-on-projects-but-not-much-water-has-flown-through-western-region-6331911.html, 2019. Accessed: 2025-02-07.

- ANI. Rajasthan Govt Declares 5555 Villages as Drought-Affected. https://www.aninews.in/news/national/general-news/rajasthan-govt-declares-5555-villages-as-drought-affected20190306224744/, 2019. Accessed: 2025-02-07.

- The Statesman. 1388 Villages in Rajasthan Declared Drought-Affected by State Govt. https://www.thestatesman.com/india/1388-villages-in-rajasthan-declared-drought-affected-by-state-govt-1502820817.html, 2019. Accessed: 2025-02-07.

- NDTV. More Than 1,000 Villages in 4 Districts of Rajasthan Affected by Drought. https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/more-than-1-000-villages-in-4-districts-of-rajasthan-affected-by-draught-2130998, 2019. Accessed: 2025-02-07.

- Government of India. Annexure to Lok Sabha Question AU454: Central Assistance for Drought. https://sansad.in/getFile/loksabhaquestions/annex/177/AU454.pdf?source=pqals, 2020. Accessed: 2025-02-07.

- Economic Times. Maharashtra Government Declares Drought in 29,000 Villages. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/maharashtra-government-declares-drought-in-29000-villages/articleshow/52238372.cms?from=mdr, 2016. Accessed: 2025-02-07.

- Hindustan Times. Maharashtra declares drought; 26 districts hit. https: //www.hindustantimes.com/mumbai-news/maharashtra-declares-drought-26-districts-hit/story-ETaPfo9owb7yVW8EQ1lQGL.html, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Times of India. Eight of 11 Vidarbha districts declared drought-hit. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/nagpur/8-of-11-vid-dists-declared-drought-hitryots-say-need-more-sops-to-tackle-crisis/articleshow/66595394.cms, 2018. Accessed: 2025-02-07.

- Times of India. Drought brings down Rabi crop area by 40% in 2018-19. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/pune/drought-brings-down-rabi-crop-area-by-40-in-2018-19/articleshow/67949533.cms, 2019. Accessed: 2025-02-07.

- Hindu, T. Rain causes immense damage to huts and paddy fields. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil-nadu/rain-causes-immense-damage-to-huts-and-paddy-fields/article7882286.ece, 2015. Accessed: 2025-02-07.

- Reports, S. Drought-Affected States Report AU981. https://sansad.in/getFile/loksabhaquestions/annex/15/AU981.pdf?source=pqals, 2016. Accessed: 2025-02-07.

- Moneylife. Retreating Monsoon Worst in 140 Years, TN Declares Drought as 144 Farmers Die. https://www.moneylife.in/article/retreating-monsoon-worst-in-140-years-tn-declares-drought-as-144-farmers-die/49433.html, 2017. Accessed: 2025-02-07.

- Tamil Nadu Agricultural Department. Government Order on Drought Declaration. https://www.tnagrisnet.tn.gov.in/fcms/documents/go/20-GO.No.29-2(2).pdf, 2017. Accessed: 2025-02-07.

- Hindu, T. Heavy rain in Tiruvarur and Thanjavur districts. https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Tiruchirapalli/heavy-rain-in-tiruvarur-and-thanjavur-districts/article19991157.ece, 2017. Accessed: 2025-02-07.

- New Indian Express. 24 districts declared as drought-hit; number to rise in coming months. https://www.newindianexpress.com/states/tamil-nadu/2019/Mar/21/24-districts-declared-as-drought-hit-number-to-rise-in-coming-months-1953962.html, 2019. Accessed: 2025-02-07.

- Bricks, N. Tamil Nadu Weather Forecast December 12, 2019. https://www.newsbricks.com/tamil-nadu/tamil-nadu-weather-forecast-december-12-2019/67258, 2019. Accessed: 2025-02-07.

- Weather.com. Northeast Monsoon to Commence Over South India From , 2020. https://weather.com/en-IN/india/news/news/2020-10-27-northeast-monsoon-commence-over-south-india-from-october-28, 2020. Accessed: 2025-02-07. 28 October.

- of India, T. Disasters That Struck India in 2020. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/disasters-that-struck-india-in-2020/articleshow/79954339.cms, 2020. Accessed: 2025-02-07.

- Mongabay. Though Cyclone Nivar Had a Soft Landing, Floods Hit Coastal Districts. https://india.mongabay.com/2020/12/though-cyclone-nivar-had-a-soft-landing-floods-hit-coastal-districts/, 2020. Accessed: 2025-02-07.

| ARVI | EVI | MNDVI | MNDWI | NDMI | NDVI | NDWI | NMDI | RDI | RECI | SAVI | TVI | date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2713 | 0.4561 | -0.2863 | -0.2797 | -0.0222 | 0.2668 | -0.2600 | 0.4326 | 1.8608 | 0.5180 | 0.4802 | 0.8747 | 2018-01-02 |

| 0.2912 | 0.6662 | -0.3054 | -0.3240 | -0.0341 | 0.2881 | -0.2937 | 0.4220 | 1.9493 | 0.5633 | 0.5184 | 0.8864 | 2018-01-07 |

| 0.2950 | 0.7153 | -0.3604 | -0.3653 | -0.0481 | 0.2945 | -0.3228 | 0.4089 | 2.2248 | 0.6098 | 0.5299 | 0.8894 | 2018-01-17 |

| Year/District | Jodhpur | Amravati | Thanjavur |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Drought | Drought | No Drought |

| 2017 | No Drought | No Drought | Drought |

| 2018 | No Drought | No Drought | No Drought |

| 2019 | Drought | Drought | Drought |

| 2020 | Drought | No Drought | No Drought |

| 2021 | No Drought | No Drought | No Drought |

| Methods/Metrics | Accuracy | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|

| XG Boost | 0.8230 | 0.7982 | 0.7390 |

| Random Forest | 0.8339 | 0.8349 | 0.7225 |

| Bagging Classifier | 0.8415 | 0.8344 | 0.7473 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.7459 | 0.7500 | 0.5457 |

| Methods/Metrics | Accuracy | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|

| XG Boost | 0.7937 | 0.7112 | 0.8049 |

| Random Forest | 0.7861 | 0.7002 | 0.8022 |

| Bagging Classifier | 0.7807 | 0.6966 | 0.7875 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.7090 | 0.6062 | 0.7527 |

| Methods/Metrics | Accuracy | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|

| XG Boost | 0.8393 | 0.8426 | 0.7527 |

| Random Forest | 0.8426 | 0.8544 | 0.7253 |

| Bagging Classifier | 0.8371 | 0.8344 | 0.7335 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.7286 | 0.6667 | 0.6264 |

| (a) XGBoost | ||

|---|---|---|

| Predicted | ||

| Actual | No Drought | Drought |

| No Drought | 489 | 68 |

| Drought | 95 | 269 |

| (b) Random Forest | ||

| Predicted | ||

| Actual | No Drought | Drought |

| No Drought | 505 | 52 |

| Drought | 101 | 263 |

| (c) Bagging | ||

| Predicted | ||

| Actual | No Drought | Drought |

| No Drought | 503 | 54 |

| Drought | 92 | 272 |

| (d) Gradient Boosting | ||

| Predicted | ||

| Actual | No Drought | Drought |

| No Drought | 492 | 65 |

| Drought | 169 | 195 |

| (a) XGBoost | ||

|---|---|---|

| Predicted | ||

| Actual | No Drought | Drought |

| No Drought | 438 | 119 |

| Drought | 71 | 293 |

| (b) Random Forest | ||

| Predicted | ||

| Actual | No Drought | Drought |

| No Drought | 432 | 125 |

| Drought | 72 | 292 |

| (c) Bagging | ||

| Predicted | ||

| Actual | No Drought | Drought |

| No Drought | 432 | 125 |

| Drought | 77 | 287 |

| (d) Gradient Boosting | ||

| Predicted | ||

| Actual | No Drought | Drought |

| No Drought | 379 | 178 |

| Drought | 90 | 274 |

| (a) XGBoost | ||

|---|---|---|

| Predicted | ||

| Actual | No Drought | Drought |

| No Drought | 499 | 58 |

| Drought | 90 | 274 |

| (b) Random Forest | ||

| Predicted | ||

| Actual | No Drought | Drought |

| No Drought | 512 | 45 |

| Drought | 100 | 264 |

| (c) Bagging | ||

| Predicted | ||

| Actual | No Drought | Drought |

| No Drought | 504 | 53 |

| Drought | 97 | 267 |

| (d) Gradient Boosting | ||

| Predicted | ||

| Actual | No Drought | Drought |

| No Drought | 443 | 114 |

| Drought | 136 | 228 |

| (a) XGBoost | ||

|---|---|---|

| Predicted | ||

| Actual | No Drought | Drought |

| No Drought | 475 | 82 |

| Drought | 63 | 301 |

| (b) Random Forest | ||

| Predicted | ||

| Actual | No Drought | Drought |

| No Drought | 473 | 84 |

| Drought | 61 | 303 |

| (c) Bagging | ||

| Predicted | ||

| Actual | No Drought | Drought |

| No Drought | 475 | 82 |

| Drought | 72 | 292 |

| (d) Gradient Boosting | ||

| Predicted | ||

| Actual | No Drought | Drought |

| No Drought | 388 | 169 |

| Drought | 91 | 273 |

| Methods/Metrics | Accuracy | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|

| XG Boost | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Random Forest | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Bagging Classifier | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| Methods/Metrics | Accuracy | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|

| XG Boost | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Random Forest | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 |

| Bagging Classifier | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| Methods/Metrics | Accuracy | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|

| XG Boost | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Random Forest | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Bagging Classifier | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Methods/Metrics | Accuracy | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|

| XG Boost | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Random Forest | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Bagging Classifier | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| XGBoost | Random Forest | Bagging | Gradient Boosting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top 1 | Acc: 0.6253 Prec: 0.5493 Rec: 0.3797 |

Acc: 0.6015 Prec: 0.4959 Rec: 0.4973 |

Acc: 0.6004 Prec: 0.495 Rec: 0.4945 |

Acc: 0.6352 Prec: 0.6111 Rec: 0.2115 |

| Top 2 | Acc: 0.734 Prec: 0.6951 Rec: 0.5824 |

Acc: 0.709 Prec: 0.6463 Rec: 0.5824 |

Acc: 0.6916 Prec: 0.5615 Rec: 0.5852 |

Acc: 0.658 Prec: 0.6485 Rec: 0.3295 |

| Top 3 | Acc: 0.747 Prec: 0.7191 Rec: 0.5097 |

Acc: 0.7633 Prec: 0.7548 Rec: 0.6297 |

Acc: 0.7644 Prec: 0.7139 Rec: 0.6374 |

Acc: 0.7025 Prec: 0.7308 Rec: 0.3486 |

| Top 4 | Acc: 0.7894 Prec: 0.7656 Rec: 0.6731 |

Acc: 0.7752 Prec: 0.7041 Rec: 0.6648 |

Acc: 0.7687 Prec: 0.7382 Rec: 0.6297 |

Acc: 0.7188 Prec: 0.7465 Rec: 0.3486 |

| Top 5 | Acc: 0.81 Prec: 0.7936 Rec: 0.7033 |

Acc: 0.81 Prec: 0.7981 Rec: 0.6951 |

Acc: 0.7894 Prec: 0.7607 Rec: 0.6813 |

Acc: 0.7318 Prec: 0.7352 Rec: 0.4239 |

| XGBoost | Random Forest | Bagging | Gradient Boosting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top 1 | Acc: 0.625 Prec: 0.549 Rec: 0.3797 |

Acc: 0.6015 Prec: 0.4959 Rec: 0.4973 |

Acc: 0.6004 Prec: 0.495 Rec: 0.4945 |

Acc: 0.6352 Prec: 0.6111 Rec: 0.2115 |

| Top 2 | Acc: 0.734 Prec: 0.6951 Rec: 0.5824 |

Acc: 0.709 Prec: 0.6463 Rec: 0.5824 |

Acc: 0.6916 Prec: 0.5615 Rec: 0.5852 |

Acc: 0.658 Prec: 0.6485 Rec: 0.3295 |

| Top 3 | Acc: 0.7492 Prec: 0.7152 Rec: 0.6701 |

Acc: 0.7416 Prec: 0.7019 Rec: 0.6016 |

Acc: 0.7362 Prec: 0.685 Rec: 0.6164 |

Acc: 0.6721 Prec: 0.6722 Rec: 0.3324 |

| Top 4 | Acc: 0.7991 Prec: 0.7573 Rec: 0.6521 |

Acc: 0.7894 Prec: 0.7591 Rec: 0.6841 |

Acc: 0.785 Prec: 0.7496 Rec: 0.6293 |

Acc: 0.6938 Prec: 0.6667 Rec: 0.4052 |

| Top 5 | Acc: 0.8241 Prec: 0.8079 Rec: 0.7083 |

Acc: 0.8263 Prec: 0.8282 Rec: 0.7143 |

Acc: 0.8208 Prec: 0.7953 Rec: 0.7363 |

Acc: 0.7318 Prec: 0.7362 Rec: 0.3987 |

| XGBoost | Random Forest | Bagging | Gradient Boosting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top 1 | Acc: 0.6428 Prec: 0.5368 Rec: 0.7005 |

Acc: 0.6384 Prec: 0.5324 Rec: 0.7005 |

Acc: 0.6384 Prec: 0.5324 Rec: 0.7005 |

Acc: 0.5863 Prec: 0.4827 Rec: 0.6511 |

| Top 2 | Acc: 0.6960 Prec: 0.5933 Rec: 0.7335 |

Acc: 0.6743 Prec: 0.5714 Rec: 0.7033 |

Acc: 0.6775 Prec: 0.5743 Rec: 0.7115 |

Acc: 0.6308 Prec: 0.5241 Rec: 0.717 |

| Top 3 | Acc: 0.7481 Prec: 0.6454 Rec: 0.8049 |

Acc: 0.7622 Prec: 0.6706 Rec: 0.7830 |

Acc: 0.7611 Prec: 0.6651 Rec: 0.7967 |

Acc: 0.6417 Prec: 0.5381 Rec: 0.6593 |

| Top 4 | Acc: 0.7731 Prec: 0.6850 Rec: 0.7885 |

Acc: 0.7785 Prec: 0.6914 Rec: 0.7940 |

Acc: 0.7763 Prec: 0.6946 Rec: 0.7747 |

Acc: 0.6743 Prec: 0.5711 Rec: 0.7060 |

| Top 5 | Acc: 0.7742 Prec: 0.6912 Rec: 0.7747 |

Acc: 0.7600 Prec: 0.6706 Rec: 0.7720 |

Acc: 0.7633 Prec: 0.6722 Rec: 0.7830 |

Acc: 0.6667 Prec: 0.5621 Rec: 0.7088 |

| XGBoost | Random Forest | Bagging | Gradient Boosting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top 1 | Acc: 0.5559 Prec: 0.4592 Rec: 0.6951 |

Acc: 0.5668 Prec: 0.4635 Rec: 0.6099 |

Acc: 0.5668 Prec: 0.4635 Rec: 0.6099 |

Acc: 0.5559 Prec: 0.4624 Rec: 0.7610 |

| Top 2 | Acc: 0.6960 Prec: 0.5933 Rec: 0.7335 |

Acc: 0.6797 Prec: 0.5762 Rec: 0.7170 |

Acc: 0.6786 Prec: 0.5756 Rec: 0.7115 |

Acc: 0.6308 Prec: 0.5241 Rec: 0.7170 |

| Top 3 | Acc: 0.7090 Prec: 0.6127 Rec: 0.7170 |

Acc: 0.7101 Prec: 0.6131 Rec: 0.7225 |

Acc: 0.7123 Prec: 0.6187 Rec: 0.7008 |

Acc: 0.6482 Prec: 0.5379 Rec: 0.7802 |

| Top 4 | Acc: 0.7535 Prec: 0.6546 Rec: 0.7967 |

Acc: 0.7427 Prec: 0.6440 Rec: 0.7802 |

Acc: 0.7459 Prec: 0.6540 Rec: 0.7582 |

Acc: 0.6721 Prec: 0.5671 Rec: 0.7198 |

| Top 5 | Acc: 0.7828 Prec: 0.6981 Rec: 0.7940 |

Acc: 0.7655 Prec: 0.6762 Rec: 0.7802 |

Acc: 0.7546 Prec: 0.6612 Rec: 0.7775 |

Acc: 0.6667 Prec: 0.5621 Rec: 0.7088 |

| XGBoost | Random Forest | Bagging | Gradient Boosting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top 1 | Acc: 0.6602 Prec: 0.5770 Rec: 0.5247 |

Acc: 0.6721 Prec: 0.5901 Rec: 0.5577 |

Acc: 0.6634 Prec: 0.5734 Rec: 0.5797 |

Acc: 0.6580 Prec: 0.6052 Rec: 0.3874 |

| Top 2 | Acc: 0.7177 Prec: 0.6615 Rec: 0.5852 |

Acc: 0.7144 Prec: 0.6583 Rec: 0.5769 |

Acc: 0.6873 Prec: 0.6111 Rec: 0.5742 |

Acc: 0.6754 Prec: 0.6148 Rec: 0.4780 |

| Top 3 | Acc: 0.7524 Prec: 0.7208 Rec: 0.6099 |

Acc: 0.7622 Prec: 0.7393 Rec: 0.6154 |

Acc: 0.7568 Prec: 0.7273 Rec: 0.6154 |

Acc: 0.6992 Prec: 0.6445 Rec: 0.5330 |

| Top 4 | Acc: 0.7644 Prec: 0.7348 Rec: 0.6319 |

Acc: 0.7524 Prec: 0.7208 Rec: 0.6099 |

Acc: 0.7524 Prec: 0.7166 Rec: 0.6181 |

Acc: 0.6862 Prec: 0.6106 Rec: 0.5687 |

| Top 5 | Acc: 0.8122 Prec: 0.8091 Rec: 0.6868 |

Acc: 0.8165 Prec: 0.8155 Rec: 0.6923 |

Acc: 0.8176 Prec: 0.8182 Rec: 0.6923 |

Acc: 0.6840 Prec: 0.6034 Rec: 0.5852 |

| XGBoost | Random Forest | Bagging | Gradient Boosting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top 1 | Acc: 0.5820 Prec: 0.4673 Rec: 0.4121 |

Acc: 0.5896 Prec: 0.4834 Rec: 0.5604 |

Acc: 0.5896 Prec: 0.4834 Rec: 0.5604 |

Acc: 0.6135 Prec: 0.5153 Rec: 0.3709 |

| Top 2 | Acc: 0.7177 Prec: 0.6615 Rec: 0.5852 |

Acc: 0.7199 Prec: 0.6688 Rec: 0.5769 |

Acc: 0.6851 Prec: 0.6088 Rec: 0.5687 |

Acc: 0.6754 Prec: 0.6148 Rec: 0.4780 |

| Top 3 | Acc: 0.7275 Prec: 0.6707 Rec: 0.6099 |

Acc: 0.7329 Prec: 0.6903 Rec: 0.5879 |

Acc: 0.7090 Prec: 0.6472 Rec: 0.5797 |

Acc: 0.6667 Prec: 0.5893 Rec: 0.5165 |

| Top 4 | Acc: 0.7514 Prec: 0.7116 Rec: 0.6236 |

Acc: 0.7535 Prec: 0.7231 Rec: 0.6099 |

Acc: 0.7293 Prec: 0.7152 Rec: 0.6071 |

Acc: 0.6873 Prec: 0.6105 Rec: 0.5769 |

| Top 5 | Acc: 0.8078 Prec: 0.7877 Rec: 0.7033 |

Acc: 0.8143 Prec: 0.8123 Rec: 0.6886 |

Acc: 0.8154 Prec: 0.8129 Rec: 0.7775 |

Acc: 0.6667 Prec: 0.5621 Rec: 0.6923 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).