Submitted:

02 September 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- ✓ To analyze the spatio-temporal pattern of meteorological drought occurrence in different climate regions across Ethiopia.

- ✓ To analyze the response of agricultural drought to meteorological drought, and discuss drought propagation dynamics at different climate zones in Ethiopia.

- ✓ To evaluate the predictive potential of machine learning models and feature importance in predicting cereal crop yields.

2. Methodology

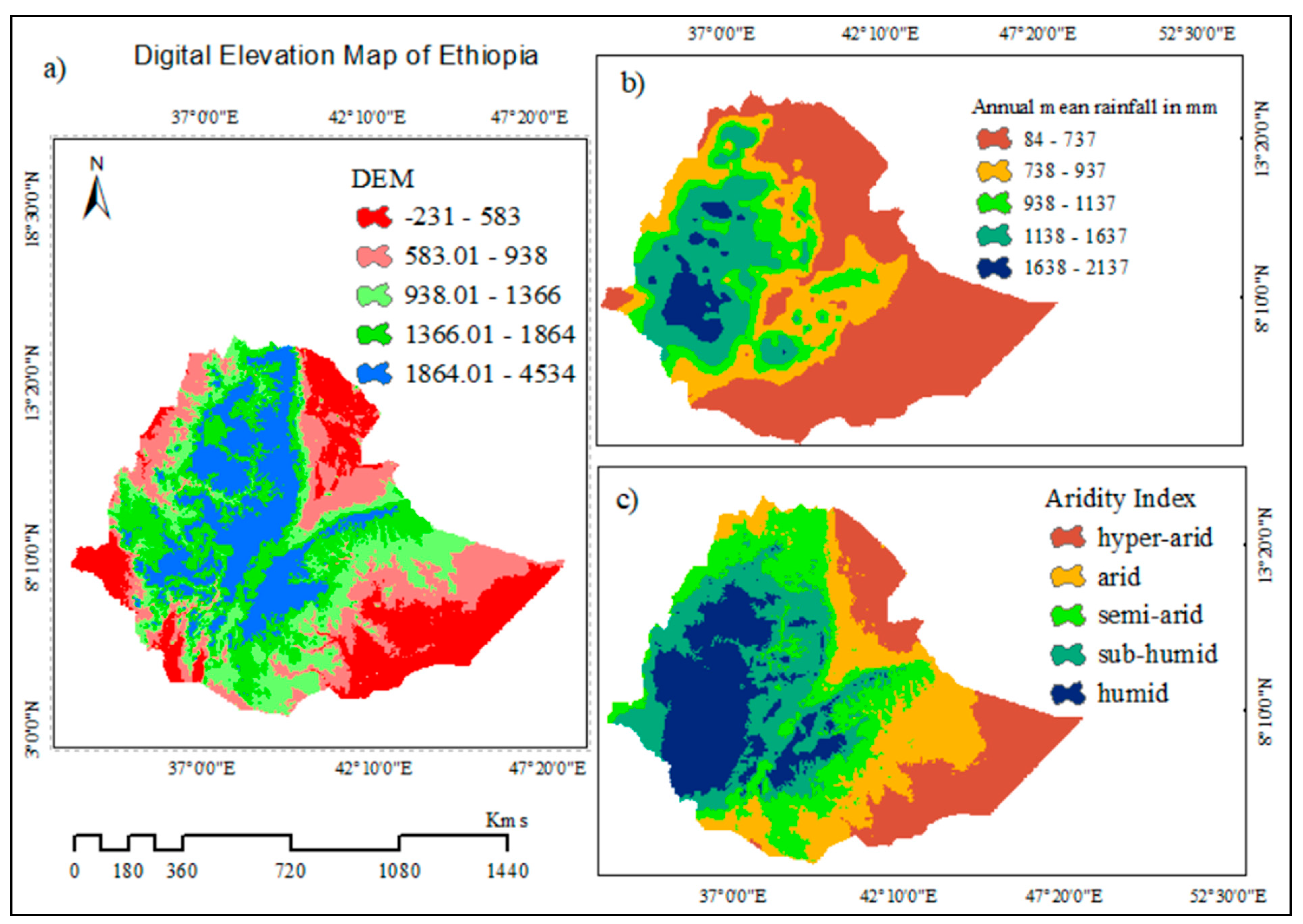

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Datasets and Sources

2.1.1. Observation Data

2.1.2. Soil Moisture

2.1.3. Crop Yield Choice

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI)

2.3.2. Drought Propagation Characteristics

2.4. Development of Crop Yield Prediction Models

2.4.1. Model Performance Evaluation and Intercomparison

3. Results

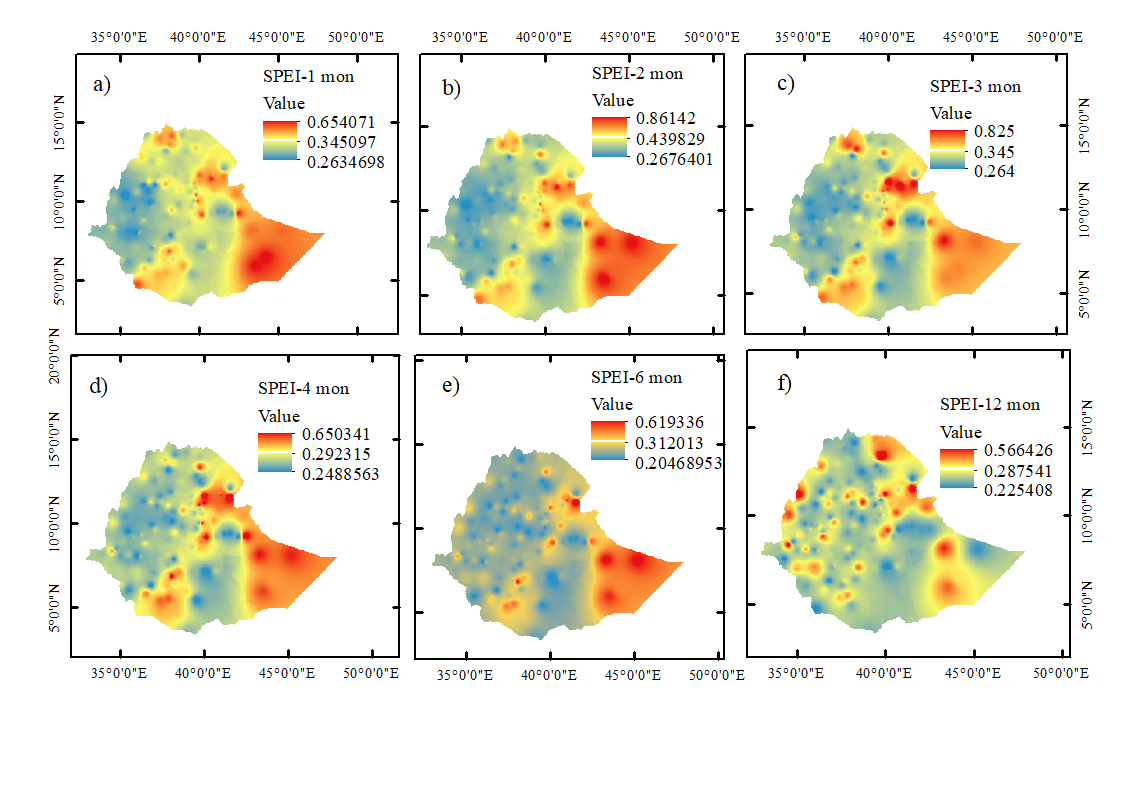

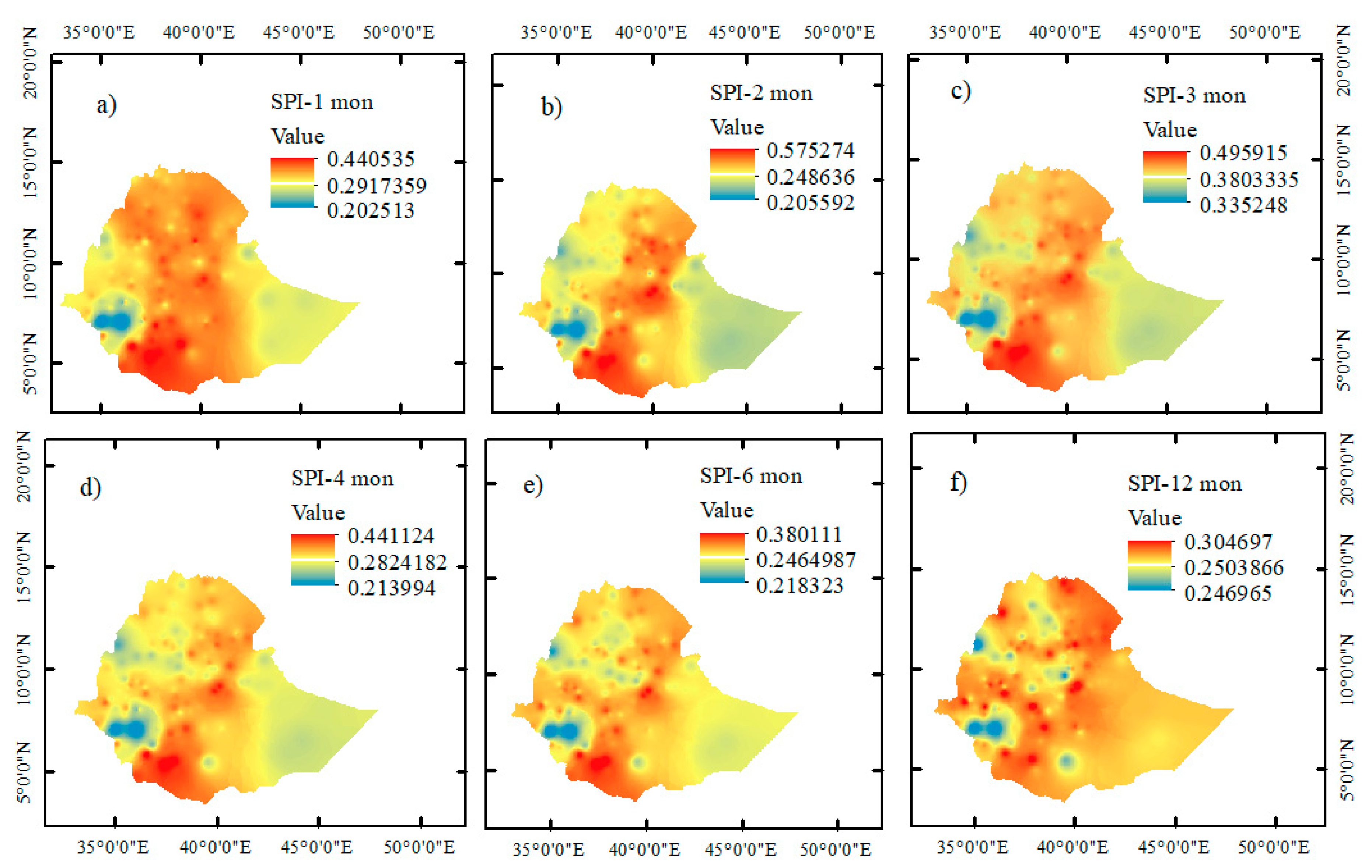

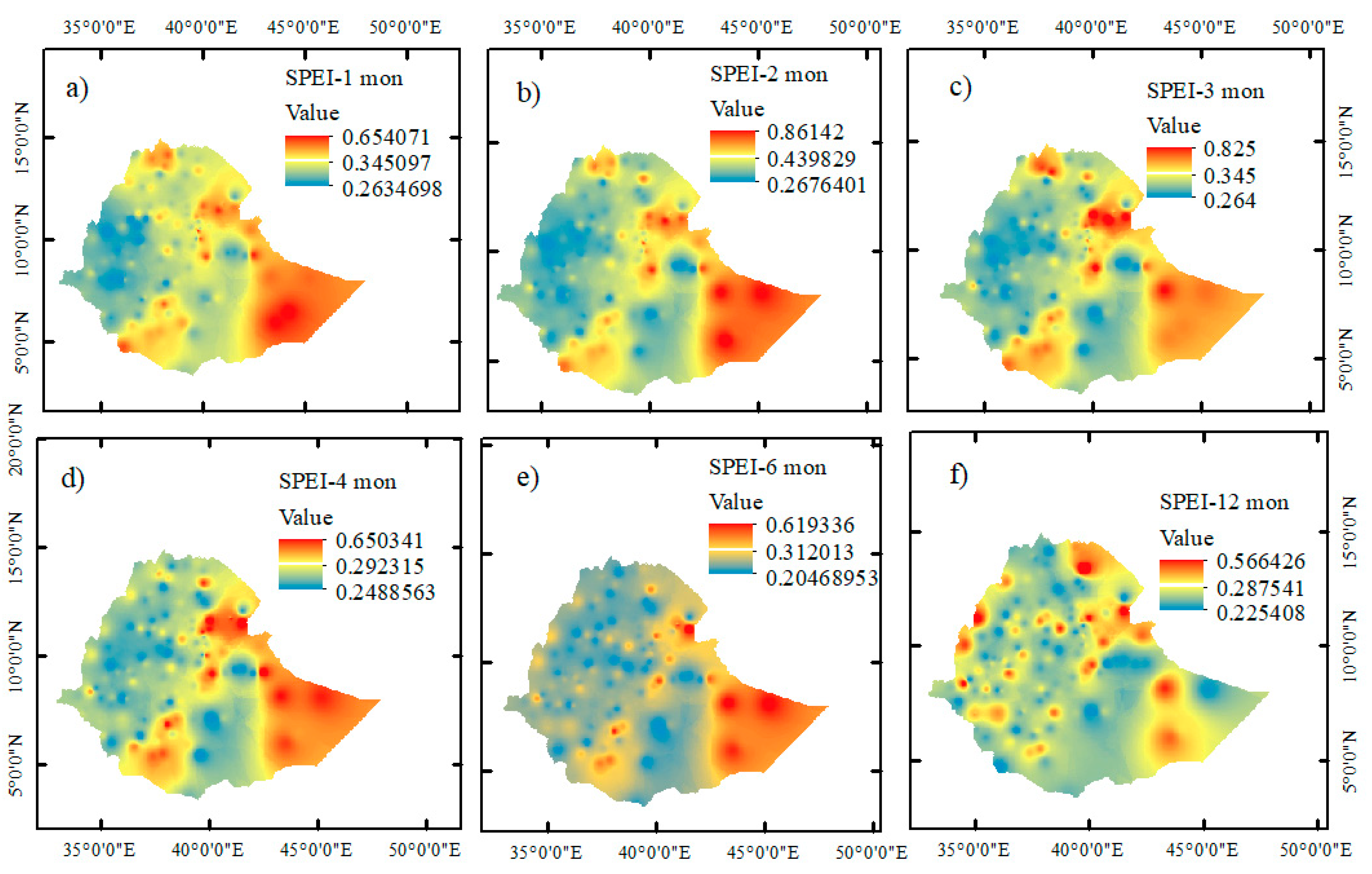

3.1. Drought Propagation Time

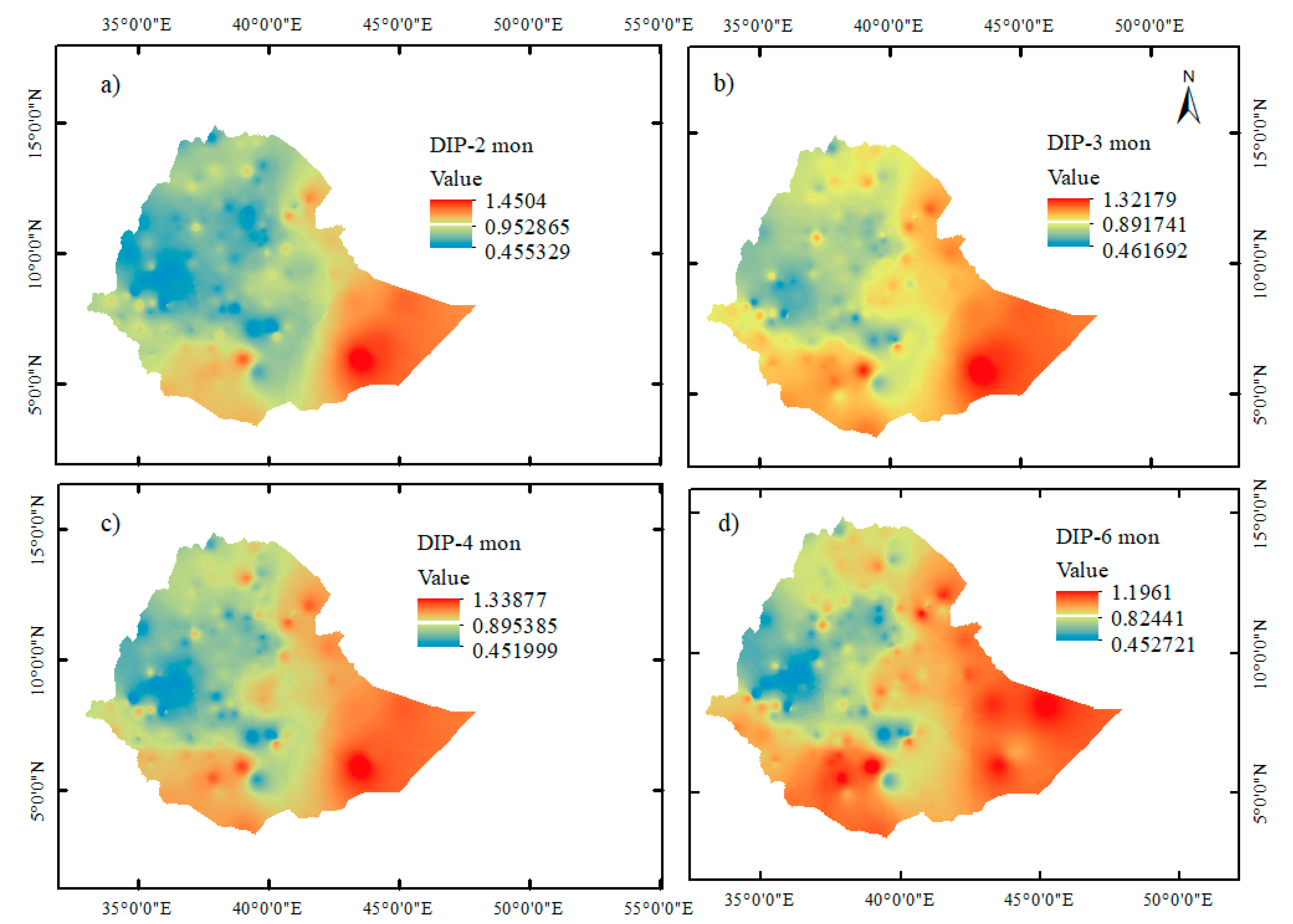

3.2. Drought Intensity Propagation

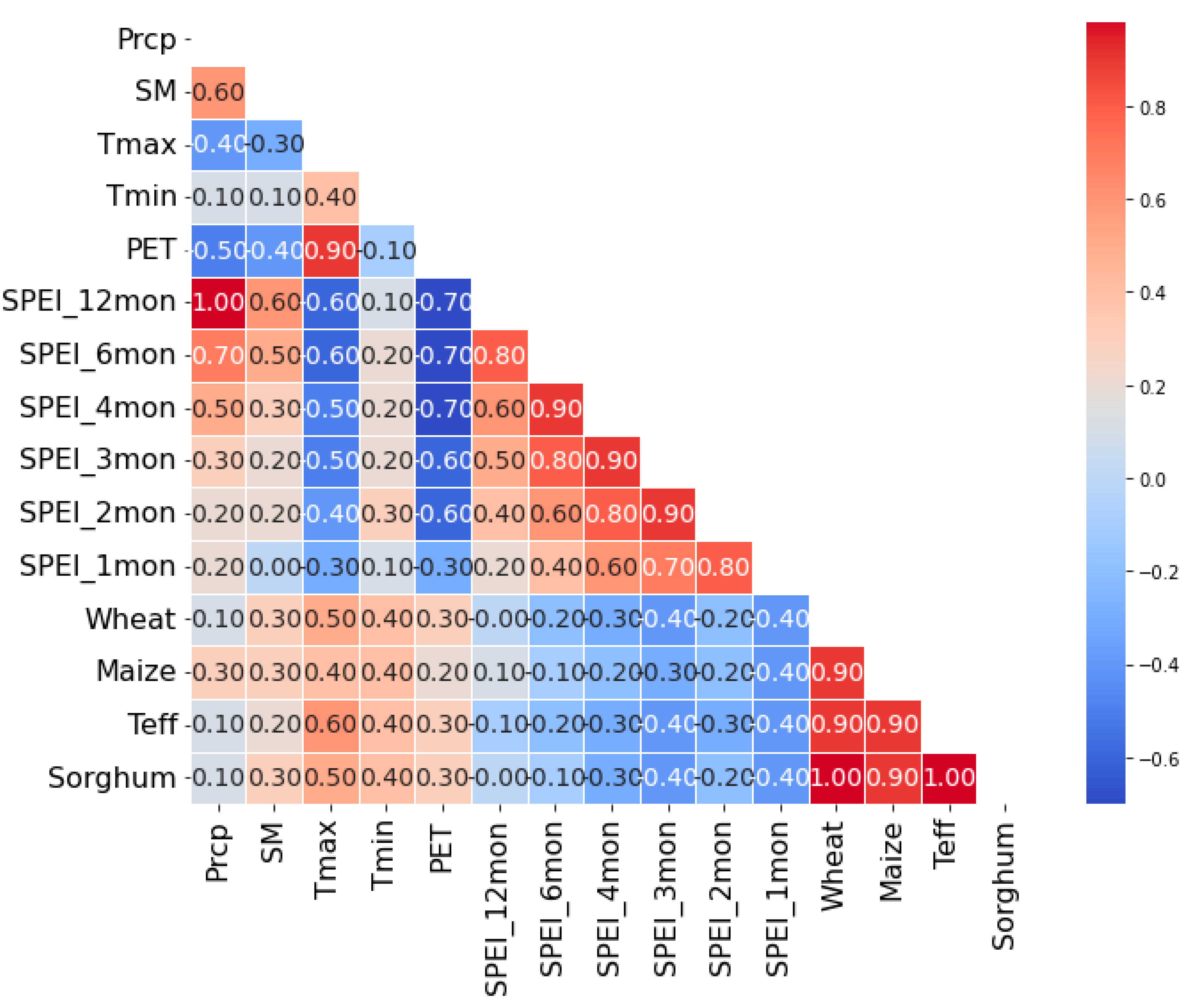

3.3. Cereal Crop Yield Prediction

3.3.1. Model Evaluation

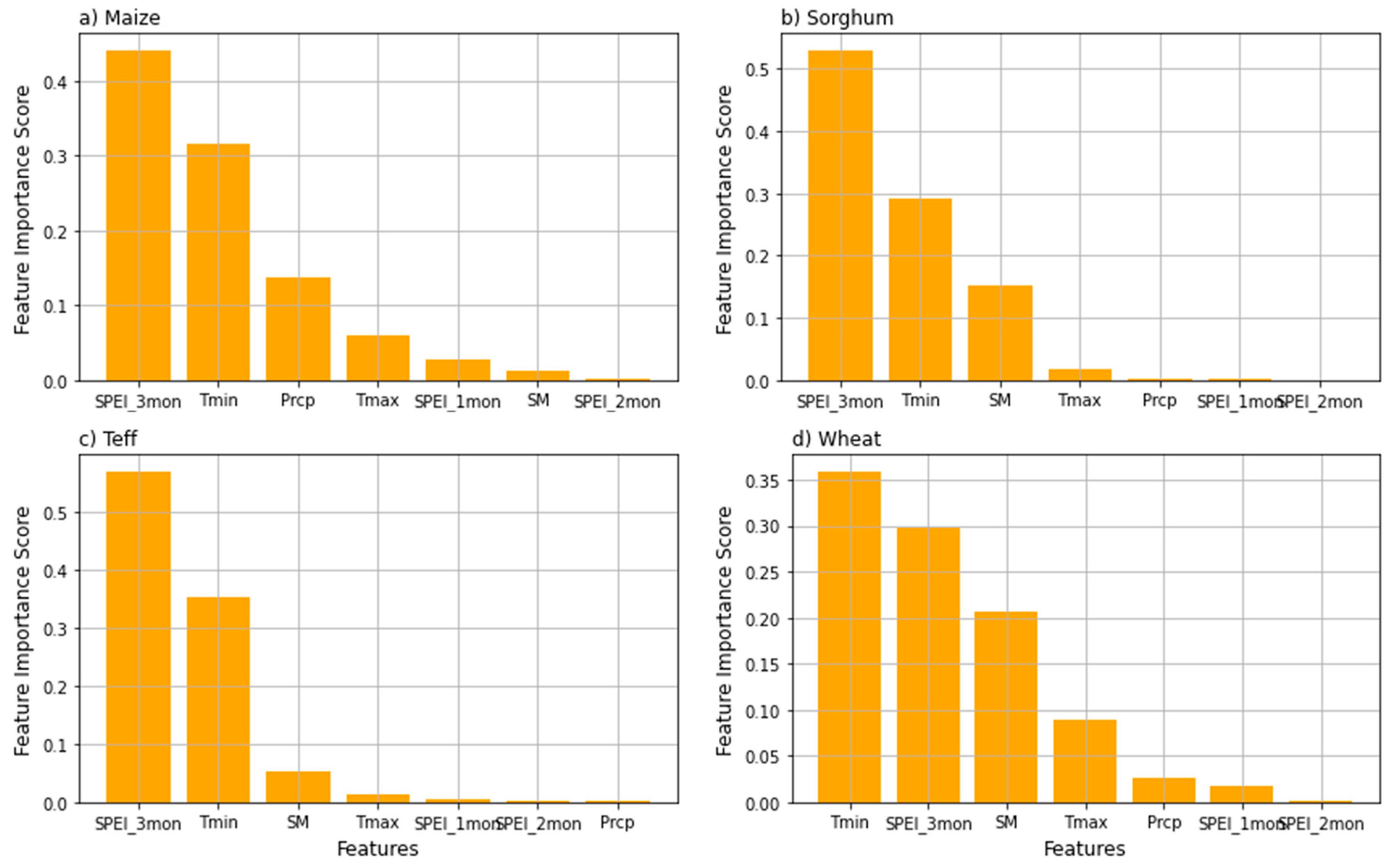

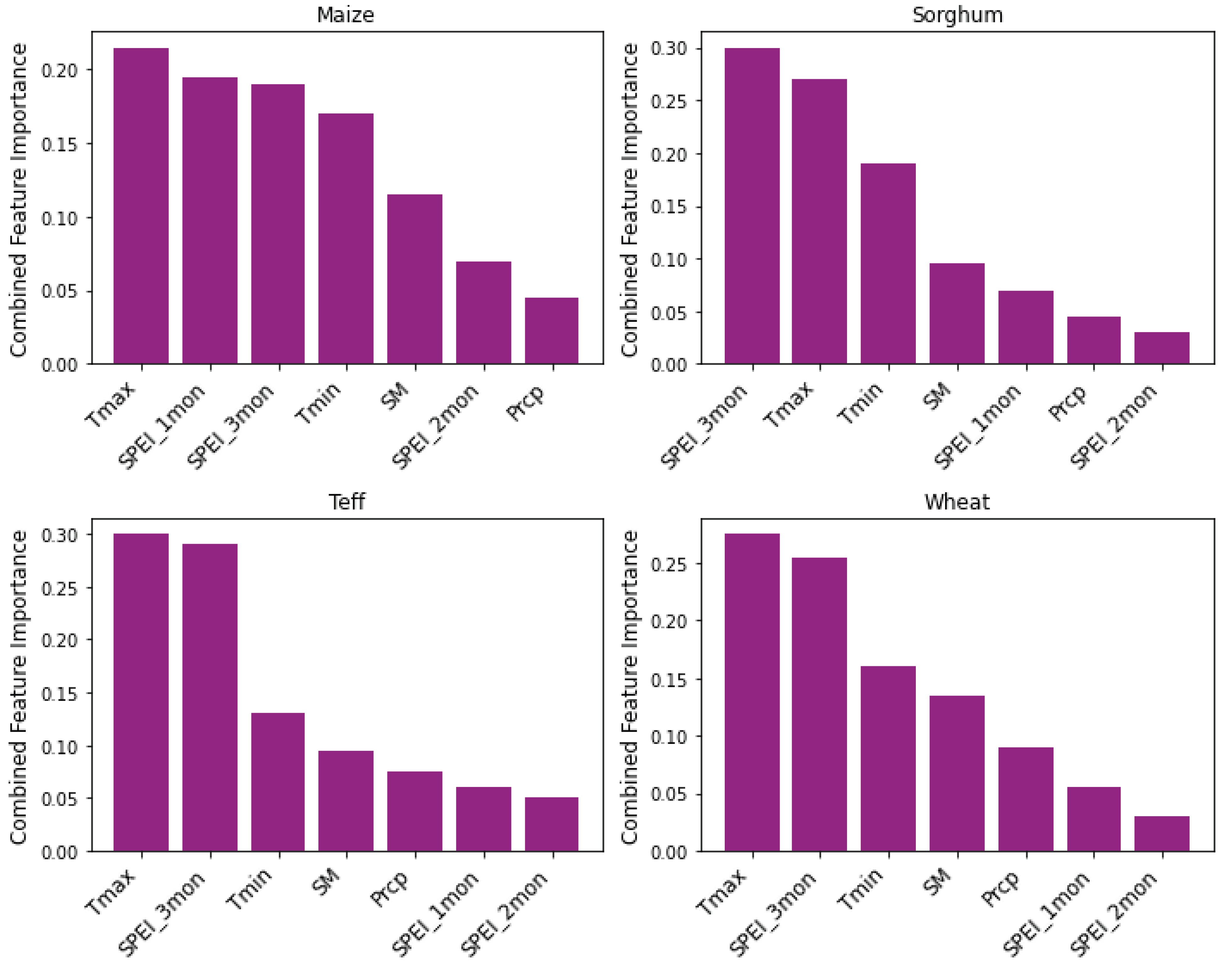

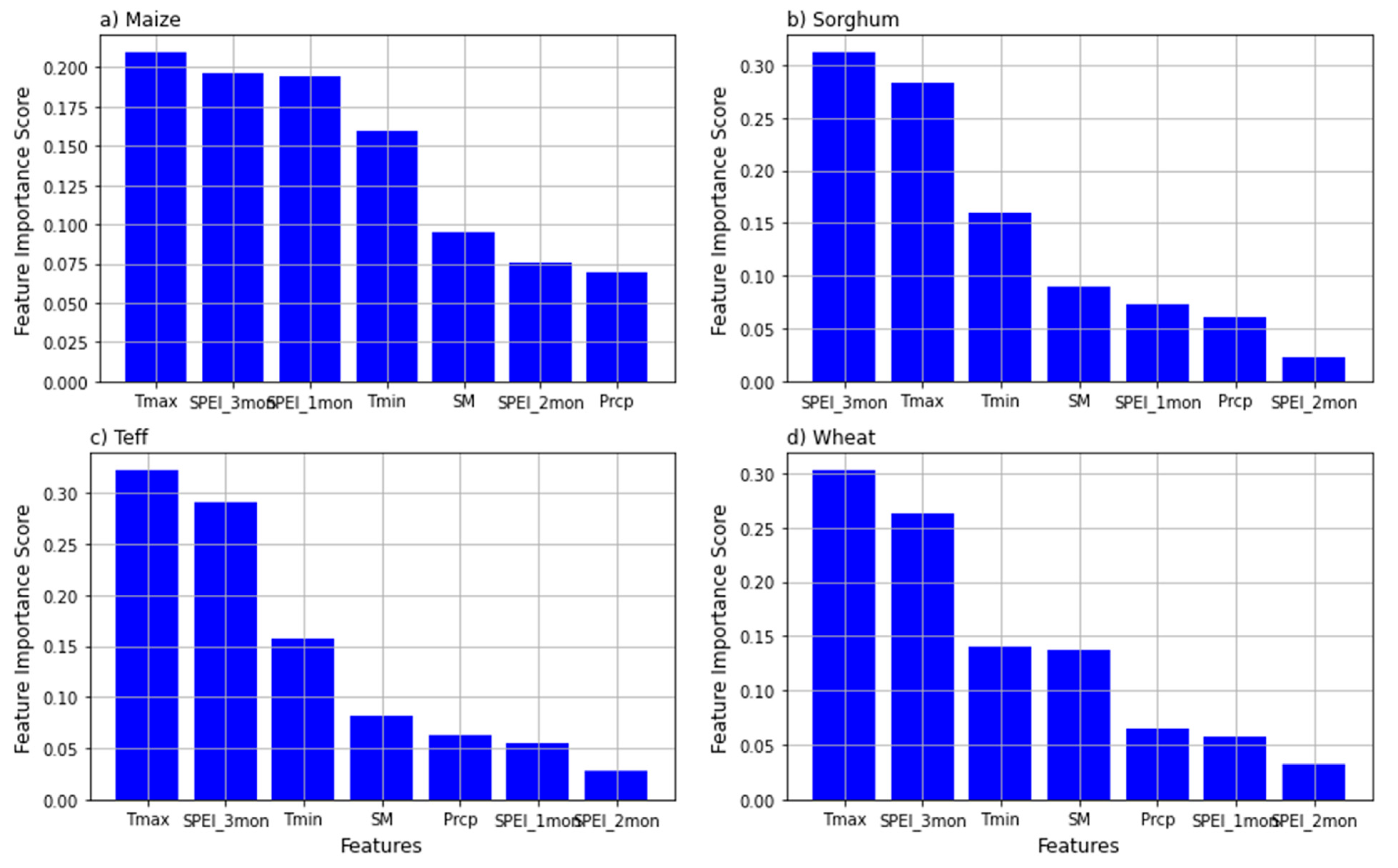

3.3.2. Feature Importance

4. Discussion and Conclusion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Material

Ethics Statement

Funding

Author Contribution

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Y. Zhou, J. Y. Zhou, J. Li, W. Jia, F. Zhang, H. Zhang, and S. Wang, “The Evolution of Drought and Propagation Patterns from Meteorological Drought to Agricultural Drought in the Pearl River Basin,” 2025.

- C. Springs, N. C. Springs, N. Carolina, O. Board, M. Regional, and N. Drought, “THE DROUGHT MONITOR,” no. April, 2002.

- M. Neelam and C. Hain, “Global Flash Droughts Characteristics : Onset, Duration, and Extent at Watershed Scales,” 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Temesgen, “Determinants of Tillage Frequency Among Smallholder Farmers in Two Semi- Arid Areas in Ethiopia Determinants of tillage frequency among smallholder farmers in two semi-arid areas in Ethiopia,” no. December, 2008. [CrossRef]

- T. Zolt, “The patterns of potential evapotranspiration and seasonal aridity under the change in climate in the upper Blue Nile basin, Ethiopia,” vol. 641, no. 22, 2024. 20 October. [CrossRef]

- S. Liu et al., “Spatiotemporal response of agricultural drought to meteorological drought in the upper Hanjiang River Basin from three-dimensional perspective,” Agric. For. Meteorol., vol. 368, p. 110531, 2025.

- T. H. E. Need and F. O. R. Proactive, “Global Drought Snapshot,” 2023.

- A. Dai, “Drought under global warming :a review,” pp. 45–65, 2011. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhang et al., “Dynamic Characteristics of Meteorological Drought and Its Impact on Vegetation in an Arid and Semi-Arid Region,” 2023.

- J. K. Green, H. J. K. Green, H. Alemohammad, J. A. Berry, and P. Gentine, “Regionally strong feedbacks between the atmosphere and terrestrial biosphere,” no. June, 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. M. O. WMO, “Drought monitoring and early warning : concepts, progress and future challenges,” World Meteorogical Organ., no. 1006, p. 24, 2006, [Online]. Available: http://www.wamis.org/agm/pubs/brochures/WMO1006e.

- Y. Liu, F. Y. Liu, F. Shan, H. Yue, X. Wang, and Y. Fan, “Global analysis of the correlation and propagation among meteorological, agricultural, surface water, and groundwater droughts,” J. Environ. Manage., vol. 333, p. 117460, 2023.

- M. Dai et al., “Propagation characteristics and mechanism from meteorological to agricultural drought in various seasons,” J. Hydrol., vol. 610, p. 127897, 2022.

- B. N. Wolteji, S. T. B. N. Wolteji, S. T. Bedhadha, S. L. Gebre, E. Alemayehu, and D. O. Gemeda, “Multiple indices based agricultural drought assessment in the rift valley region of Ethiopia,” Environ. Challenges, vol. 7, p. 100488, 2022.

- J. Wu, X. J. Wu, X. Chen, H. Yao, and D. Zhang, “Multi-timescale assessment of propagation thresholds from meteorological to hydrological drought,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 765, p. 144232, 2021.

- A. K. Mishra and V. P. Singh, “Review paper A review of drought concepts,” J. Hydrol., vol. 391, no. 1–2, pp. 202–216, 2010. [CrossRef]

- W. J. Quirk and U. States, “Drought in the Sahara : A Biogeophysical Feedback Mechanism,” no. 75, 2014. 19 March. [CrossRef]

- S. Huang, P. S. Huang, P. Li, Q. Huang, G. Leng, B. Hou, and L. Ma, “The propagation from meteorological to hydrological drought and its potential influence factors,” J. Hydrol., vol. 547, pp. 184–195, 2017.

- A. I. Gevaert, T. I. E. A. I. Gevaert, T. I. E. Veldkamp, and P. J. Ward, “The effect of climate type on timescales of drought propagation in an ensemble of global hydrological models,” pp. 4649–4665, 2018.

- J. Wei et al., “Drought variability and its connection with large-scale atmospheric circulations in Haihe River Basin,” Water Sci. Eng., 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. K. Kumar, B. K. K. Kumar, B. Rajagopalan, and M. A. Cane, “On the Weakening Relationship Between the Indian Monsoon and ENSO Published by : American Association for the Advancement of Science Stable URL : https://www.jstor.org/stable/2898422 Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article : You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. On the Weakening Relationship Between the Indian Monsoon and ENSO,” vol. 284, no. 5423, pp. 2156–2159, 1999.

- E. Viste, D. E. Viste, D. Korecha, and A. Sorteberg, “Recent drought and precipitation tendencies in Ethiopia,” Theor. Appl. Climatol., vol. 112, no. 3–4, 2013. [CrossRef]

- G. M. Tullu, “Impact of ENSO on Drought in Borena Zone, Ethiopia,” no. January, 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Warner and M. L. Mann, “Agricultural Impacts of the 2015 / 2016 Drought in Ethiopia Using High- Agricultural Impacts of the 2015 / 2016 Drought in Ethiopia Using High-Resolution Data Fusion Methodologies,” no. October, 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Korecha and A. G. Barnston, “Predictability of June-September rainfall in Ethiopia,” Mon. Weather Rev., vol. 135, no. 2, pp. 628–650, 2007. [CrossRef]

- D. Korecha and A. Sorteberg, “Validation of operational seasonal rainfall forecast in Ethiopia,” Water Resour. Res., vol. 49, no. 11, pp. 7681–7697, 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. Review, “Research Progress and Conceptual Insights on Drought Impacts and Responses among Smallholder Farmers in South Africa :,” 2022.

- F. Mare, Y. T. F. Mare, Y. T. Bahta, and W. Van Niekerk, “Development in Practice The impact of drought on commercial livestock farmers in South Africa,” vol. 4524, 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. 1267. 2019.

- E. for the C. of H. A. OCHA, “DROUGHT RESPONSE of ETHIOPIA,” vol. 2022, no. December, 2022, [Online]. Available: https://reliefweb. 2022.

- B. K. Wossenyeleh, V. U. B. K. Wossenyeleh, V. U. Brussel, and A. S. Kasa, “Drought propagation in the hydrological cycle in a semiarid region : a case study in the Bilate catchment, Ethiopia Drought propagation in the hydrological cycle in a semiarid region : a case study in the Bilate catchment, Ethiopia,” no. February, 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. M. Tullu and M. T. Guta, “Effects of meteorological and agricultural droughts on crop production in Arsi Effects of meteorological and agricultural droughts on crop production in Arsi Zone Ethiopia,” no. January, 2025. [CrossRef]

- F. Wang et al., “Dynamic variation of meteorological drought and its relationships with agricultural drought across China,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 261, p. 107301, 2022.

- Y. Dahhane, V. Y. Dahhane, V. Ongoma, A. Hadri, M. H. Kharrou, and O. Hakam, “Probabilistic linkages of propagation from meteorological to agricultural drought in the North African semi-arid region,” 2023.

- S. Park, J. S. Park, J. Lee, M. Jeong, S. Park, Y. Kim, and H. Yoon, “Identification of propagation characteristics from meteorological drought to hydrological drought using daily drought indices and lagged correlations analysis Journal of Hydrology : Regional Studies Identification of propagation characteristics from meteorological drought to hydrological drought using daily drought indices and lagged correlations analysis,” J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud., vol. 55, no. November, p. 101939, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Von Matt, R. C. Von Matt, R. Muelchi, L. Gudmundsson, and O. Martius, “Compound droughts under climate change in Switzerland,” vol. 2022, no. January, pp. 1–37, 2024.

- D. Muthuvel and X. Qin, “Probabilistic Analysis of Future Drought Propagation, Persistence, and Spatial Concurrence in Monsoon-Dominant Asian Region under Climate Change,” no. March, 2025.

- M. Rashid, B. S. M. Rashid, B. S. Bari, Y. Yusup, M. A. Kamaruddin, and N. Khan, “A Comprehensive Review of Crop Yield Prediction Using Machine Learning Approaches With Special Emphasis on Palm Oil Yield Prediction,” vol. 9, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Capuano, M. P. Capuano, M. Sellerino, A. Ruocco, W. Kombe, and K. Yeshitela, “Climate change induced heat wave hazard in eastern Africa: Dar Es Salaam (Tanzania) and Addis Ababa (Ethiopia) case study,” p. 3366, Apr. 2013.

- R. J. Zomer, X. R. J. Zomer, X. Jianchu, and A. Tr, “Version 3 of the Global Aridity Index and Potential Evapotranspiration Database,” pp. 1–15, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Gaillard, N. M. Gaillard, N. Whitehouse, M. Madella, K. Morrison, and L. Von Gunten, “Past land-use and land-cover change:the challenge of quantification at the subcontinental to global scales,” vol. 26, no. 1, 2018.

- T. Dinku and S. J. Connor, “Improving availability, access and use of climate information,” no. December, 2014.

- T. Dinku, R. T. Dinku, R. Faniriantsoa, R. Cousin, I. Khomyakov, and A. Vadillo, “ENACTS : Advancing Climate Services Across Africa,” vol. 3, no. January, pp. 1–16, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Q. Li, A. Q. Li, A. Ye, Y. Zhang, and J. Zhou, “The Peer-To-Peer Type Propagation From Meteorological Drought to Soil Moisture Drought Occurs in Areas With Strong Land-Atmosphere Interaction Water Resources Research,” 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. G. & Karthikeyan, “Role of Initial Conditions and Meteorological Drought in Soil Moisture Drought Propagation: An Event-Based Causal Analysis Over South Asia,” pp. 1–21, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Zomer and A. Trabucco, “Global Aridity Index and Potential Evapo-Transpiration ( ET 0 ) Database v3 Methodology and Dataset Description,” no. March, pp. 1–6, 2022.

- E. Elias, P. F. E. Elias, P. F. Okoth, J. J. Stoorvogel, and G. Berecha, “Cereal yields in Ethiopia relate to soil properties and N and P fertilizers,” Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems, vol. 126, no. 2, pp. 279–292, 2023. [CrossRef]

- CSA, “The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Central Statistical Agency (CSA) Report on Area, Production and Farm Management Practice of Belg Season Crops for Private Peasant Holdings,” vol. V, p. 25, 2021.

- E. October. 2019.

- CSA, “The Federa Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, the Centeral Statistical Agency (CSA) Report on Area and Production of Majr Crops,” vol. I, 2020.

- L. Cochrane and Y. W. Bekele, “Data in Brief Average crop yield ( 2001 – 2017 ) in Ethiopia : Trends at national, regional and zonal levels,” Data Br., vol. 16, pp. 1025–1033, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Vicente-Serrano, S. S. M. Vicente-Serrano, S. Beguería, and J. I. López-Moreno, “A multiscalar drought index sensitive to global warming: the standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index,” J. Clim., vol. 23, no. 7, pp. 1696–1718, 2010.

- Z. You et al., “Mechanisms of meteorological drought propagation to agricultural drought in China : insights from causality chain,” npj Nat. Hazards, 2025. [CrossRef]

- G. H. Hargreaves and R. G. Allen, “History and Evaluation of Hargreaves Evapotranspiration Equation,” J. Irrig. Drain. Eng., vol. 129, no. 1, pp. 53–63, 2003. [CrossRef]

- P. Pandya and N. K. Gontia, “Early crop yield prediction for agricultural drought monitoring using drought indices, remote sensing, and machine learning techniques,” no. January, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Shi, “A New Perspective on Drought Propagation : Causality Geophysical Research Letters,” pp. 1–9, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Dinku, “The Climate Data Tool : Enhancing Climate Services Across Africa,” no. April, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. K. T. G, C. K. K. T. G, C. Shubha, and S. A. Sushma, “Random Forest Algorithm for Soil Fertility Prediction and Grading Using Machine Learning,” no. 1, pp. 1301–1304, 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Genuer et al., “Variable selection using Random Forests To cite this version : HAL Id : hal-00755489,” vol. 31, no. 14, 2012.

- D. Wallach, D. D. Wallach, D. Makowski, and J. W. Jones, “Working with Dynamic Crop Models, 2nd Edition Table of Contents,” no. December, pp. 1–2, 2013.

- S. Kim et al., “Modeling Temperature Responses of Leaf Growth, Development, and Biomass in Maize with MAIZSIM,” pp. 1523–1537, 2012. [CrossRef]

- T. Chai, R. R. T. Chai, R. R. Draxler, and C. Prediction, “Root mean square error ( RMSE ) or mean absolute error ( MAE )? – Arguments against avoiding RMSE in the literature,” no. 2005, pp. 1247–1250, 2014. [CrossRef]

- P. Krause and D. P. Boyle, “Advances in Geosciences Comparison of different efficiency criteria for hydrological model assessment,” pp. 89–97, 2005.

- J. H. Jeong, J. P. J. H. Jeong, J. P. Resop, N. D. Mueller, and D. H. Fleisher, “Random Forests for Global and Regional Crop Yield Predictions,” pp. 1–15, 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. Toleva, “The Proportion for Splitting Data into Training and Test Set for the Bootstrap in Classification Problems,” no. May, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Xu, X. H. Xu, X. Wang, C. Zhao, S. Shan, and J. Guo, “Seasonal and aridity influences on the relationships between drought indices and hydrological variables over China,” Weather Clim. Extrem., vol. 34, p. 100393, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Gaona, P. J. Gaona, P. Quintana-seguí, M. J. Escorihuela, A. Boone, and M. C. Llasat, “Interactions between precipitation, evapotranspiration and soil-moisture-based indices to characterize drought with high-resolution remote sensing and land-surface model data,” pp. 3461–3485, 2022.

- S. Data, “Selection of Independent Variables for Crop Yield Prediction Sensing Data,” 2021.

- O. M. Adisa et al., “Application of Artificial Neural Network for Predicting Maize Production in South Africa,” pp. 1–17. [CrossRef]

- S. Kim and H. Kim, “A new metric of absolute percentage error for intermittent demand forecasts,” Int. J. Forecast., vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 669–679, 2016. [CrossRef]

| SPEI Values | Categories of Climatic Moisture | SPEI Values | Categories of Climatic Moisture |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 2.00 | Extremely wet | -1.49 to -1.00 | Moderately dry |

| 1.05 to 1.99 | Severely wet | -1.99 to -1.50 | Severely dry |

| 1.00 to 1.49 | Moderately wet | ≤ -2 | Extremely dry |

| DIP | Index Range | DIP | Index Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| (0.9, 1.1) | Peer-to-peer | ||

| (1.1, 1.2) | Mildly strong | (0.8, 0.9) | Middy weak |

| (1.2, 1.3) | Moderately strong | (0.7, 0.8) | Moderately weak |

| (1.3, +∞) | Extra strong | (0.0, 0.7) | Extra weak |

| Crop | RF MAE (qt/ha) | RF RMSE (qt/ha) | RF R² | XGB MAE (qt/ha) | XGB RMSE (qt/ha) | XGB R² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | 3.4046 | 4.04 | 0.59 | 2.9054 | 8.85 | 0.64 |

| Maize | 4.5439 | 5.98 | 0.54 | 2.7817 | 14.47 | 0.71 |

| Sorghum | 2.6566 | 2.99 | 0.72 | 1.9426 | 7.81 | 0.74 |

| Teff | 2.2363 | 2.45 | 0.56 | 2.7817 | 2.45 | 0.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).