1. Introduction

Bovine leukemia virus (BLV) belongs to the Retroviridae family, Orthoretrovirinae subfamily, and Deltaretrovirus genus, which also includes such well-known representatives as human and simian T-lymphotropic viruses [

1,

2]. BLV is the causative agent of enzootic bovine leukosis (EBL). EBL is one of the most common virus-induced oncological diseases in cattle worldwide [

3]. The time from the moment of infection of a cow with BLV to the appearance of pronounced symptoms of the disease can vary greatly [

4]. In addition, about 70% of infected animals are in a state of chronic asymptomatic infection, while 30% have lymphocytosis. About 5% of all infected livestock develop an oncogenic process [

5]. All these factors significantly complicate the timely diagnosis of the disease. In natural conditions, BLV infects exclusively cattle, spreading through horizontal or vertical transmission mechanisms. In experimental conditions, it was found that the virus is also capable of infecting pigs, horses, monkeys and rabbits. [

6,

7].

BLV causes a chronic infection, the mechanism of which is the integration of BLV provirus DNA into the host cell genome. This leads to long-term persistence of the virus. The chronic nature of the infection ensures the preservation of cells in an intact state for a long time, which contributes to the use of these cells as systems for the constant synthesis of viral particles [

8]. The main targets of BLV in the body are B lymphocytes and plasma cells, but BLV is also able to infect CD2+ T cells, CD3+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, γ/δ T helpers, monocytes and some granulocytes [

9].

The BLV genome is a single-stranded RNA+ molecule approximately 9,000 nucleotides long. There is a CAP structure at the 5' end of the genome, and at the 3' end there is a polyadenylated tail (poly-A). The BLV genome contains genes encoding structural proteins (gag and env), enzymes (pro and pol), and regulatory proteins (tat and rex) [

10,

11]. The region of the BLV env gene, which encodes receptor-binding proteins is of the greatest interest.

There has been increased interest in studying the genetic variability of the BLV env gene in isolates extracted from different geographic regions in recent years. Particular attention has been paid to the region of the env gene encoding the gp51 glycoprotein, based on which BLV strains were classified into seven genotypes in 2009 [

12]. Subsequently, genotype 8 was described, which was detected in samples from Croatia in 2012 [

13], as well as genotypes 9 and 10, detected in samples from Bolivia in 2016 [

14], Thailand in 2016 [

15], and Myanmar in 2017 [

16]. In 2019, genotype 11 was described in China [

17], and in 2021, genotype 12 was described in Kazakhstan [

18].

Deciphering and analyzing the genomic sequences of BLV strains are key steps for a deep understanding of the life cycle of this virus, the mechanisms of pathogenesis of enzootic bovine leukemia (EBL) and the patterns of infection spread. Molecular epidemiological analysis of BLV includes the study of phylogenetic relationships between BLV isolates extracted from different geographic regions. Comparative study of nucleotide sequences allows not only to identify the routes of virus transmission, but also to reconstruct its evolutionary changes, which contributes to the development of more effective measures for disease control and prevention [

17,

18,

19].

The results of epizootological studies are of practical importance, as EBL poses a serious threat to livestock breeding. This virus results in a decrease of milk yield, a reduction in the average life expectancy of cows, and the need to introduce quarantine measures and restrictions on the export of products from infected animals. Direct economic losses caused by EBL in the livestock industry are significant for many countries. For example, in the United States alone, the damage from this disease in 2021 amounted to

$ 285 million [

20].

According to global statistics, the prevalence of EBL among bovine in some regions of the world reaches 90% [

21]. In Russia, according to general estimates, the prevalence rate of cattle with BLV based on diagnostics using ELISA and immunodiffusion reaction is at the level of 7% (924 thousand out of 15.5 million animals are carriers of BLV). BLV infection is the first in the ranking of causes of cattle mortality [

22]. According to the Veterinary Department of the Ministry of Agriculture of Russia, the epizootic situation with bovine leukemia is focal in nature [

23].

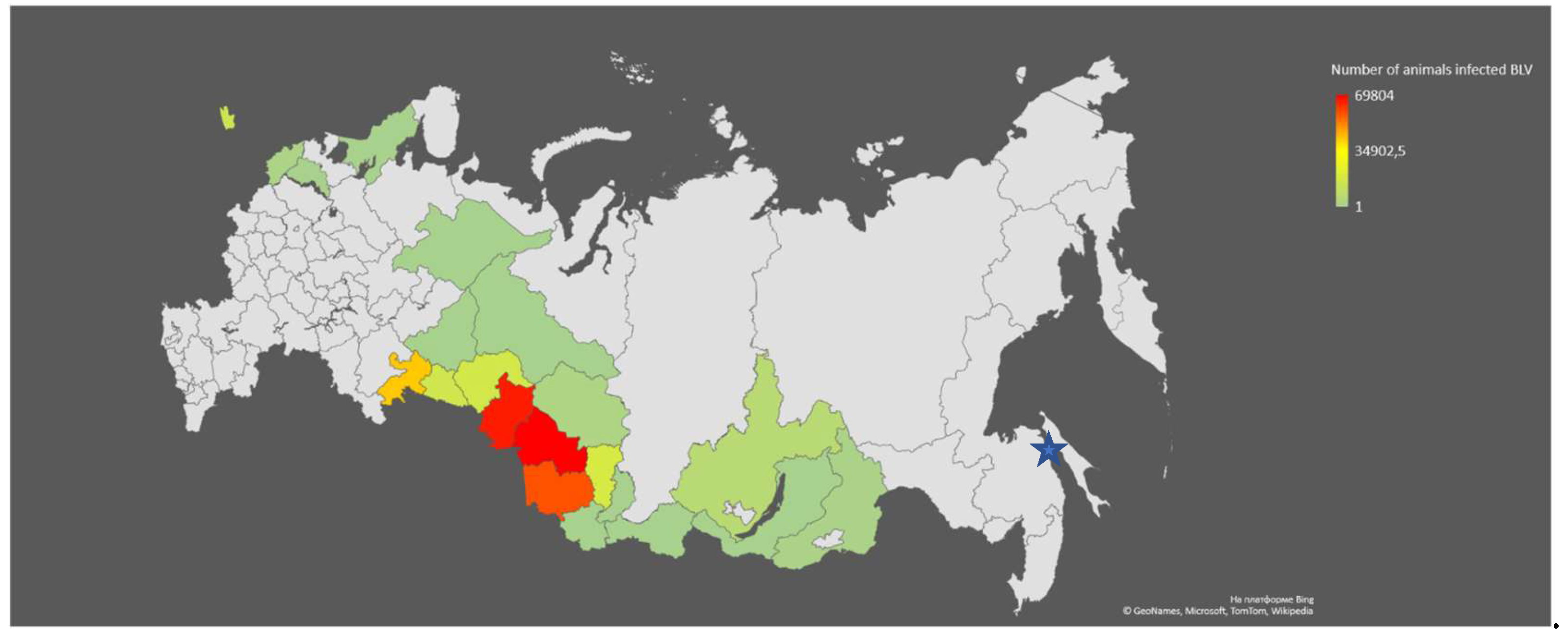

The Novosibirsk region (NREG) is a significant agricultural region of the Russian Federation (RF), playing a key role in providing the country's population with dairy and meat products. At the same time, the NREG belongs to the group of unfavorable regions in terms of cattle BLV infestation (

Figure 1) [

22].

Molecular-epidemiological data on the spread of BLV in the Russian Federation are limited and require further expansion to successfully counteract this pathogen.

The aim of this study was to analyze the prevalence of bovine leukemia virus among cows in the Novosibirsk region of the Russian Federation, genotyping the identified BLV isolates, and studying the phylogenetic relationships of viruses circulating in Russia based on the analysis of the sequences of the env gene fragment encoding the BLV gp51 protein.

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of BLV Among Cattle in Individual and Commercial Farms of Kochenyovo District of Novosibirsk Region

It was necessary to determine at the initial phase of the study which farms (small or large) had the highest proportion of infected animals. These data were important for expanding the scope of epidemiological research.

Kochenyovo district was selected to assess the prevalence of bovine leukemia virus (BLV) in small and large livestock farms of the Novosibirsk region. As part of the study, 317 blood samples were collected, including 200 samples from animals from a large livestock farm Razdolnoye LLC and 117 samples from private livestock of small individual farms in remote settlements of Kochenyovo district. Animals were selected for analysis randomly. A population of mononuclear cells was isolated from whole blood samples of cattle, from which total cellular DNA was isolated, which was then used for PCR diagnostics of animals to detect DNA of the BLV. The results of the PCR analysis are presented in

Table 1.

In individual farms located in five territorially remote settlements of the Kochenevyovo district (settlements of Kochenyovo, Shagalovo, Kazakovo, Prokudskoe, Svetly), significant differences in the prevalence of animals were found. A positive PCR test for the presence of DNA of the BLV was obtained for cattle in 4 of the 5 settlements, the detection rate of DNA of the BLV varied from 0 to 79% with a median value of 38.5% [95% CI: 0; 76.7].

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of BLV Strains Spreading in the Novosibirsk Region

The performed screening of cattle revealed a high prevalence of leukemia in bovine kept in a large meat and dairy farm. Therefore, in order to study the genetic diversity of BLV, it was decided to additionally collect blood samples from cattle with previously diagnosed BLV infection using the ELISA method in five large farms in the Novosibirsk region located far from each other in the Bolotnoye, Tatarsk, Toguchinsk, Barabinsk and Dovolnoye districts.

In total, out of 459 cow blood samples collected in remote areas of the Novosibirsk region, BLV env fragments were successfully obtained and sequenced for 417 samples, including 191 for samples of animals from farms in the Kochenyovo district, 60 from Bolotnoye, 60 from Tatarsk, 54 from Toguchin, 35 from Barabinsk and 17 from Dovolnoye districts (Fig. 2).

The obtained env-gp51 nucleotide sequences of approximately 1000 bps long were used to analyze the genetic diversity of the isolated BLVs. To construct a phylogenetic tree based on the ML method, 396 deciphered env BLV nucleotide sequences and reference sequences of other BLV isolates previously classified into known genotypes G1–G12 were used. Additionally, the phylogenetic tree included the most identical BLV nucleotide sequences from GenBank, selected using the Blast resource.

The performed phylogenetic analysis turned out to be uninformative due to the extremely limited number of BLV sequences deposited in GenBank that were longer than 800 bps, which significantly reduced the sampling for comparing BLV isolates when conducting phylogenetic analysis.

Since the shorter env fragment of 400-500 bps long is most often used in molecular genetic studies of BLV, it was decided to take similar fragments of the sequences we deciphered and use them to study phylogenetic relationships with other BLV strains circulating in the world.

Phylogenetic analysis performed on the basis of a 540 bps long fragment of the env gene showed that all BLV sequences isolated in the Novosibirsk region are grouped with a high level of support into two separate clades with reference samples of the G4 and G7 genotypes (Fig. 3). Thus, it can be concluded that the BLV sequences we obtained belong to two BLV genotypes - G4 and G7. It can be said that G4 predominates in the Novosibirsk region, since the distribution of this virus genotype significantly prevails in 5 of the 6 studied districts of the Novosibirsk region (

Table 2). The G7 BLV genotype predominated only in the Toguchin district (78.3% of infected animals).

The viruses of the G7 genotype were clustered with the BLV G7 viruses isolated in different regions of the Russian Federation, as well as in Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Moldova. The BLV G7 population studied in this work demonstrated a high degree of homogeneity. Phylogenetic analysis of the BLV G7 did not reveal any statistically significant association of samples based on their belonging to the farm. The only exceptions were Tatarsk (clusters with a support level from 74 to 100, 2-3 samples), Razdolnoye (clusters with a support level from 90 to 100, 2-4 samples), Toguchin (there is a large cluster of 16 viruses with a support level of 74). Pairs or threes of the BLV G7 samples isolated in almost every farm, where the circulation of this genovariant of the virus was observed, formed phylogenetic branches with a support index of 100, which may indicate the spread of the BLV infection within each farm.

Among the studied BLV G7 5 virus variants (Fig. 3, the branch is marked with an arrow), 2 from Dovolnoye and 3 from Tatarsk district (the distance between these districts is about 400 km, Fig. 2) formed a separate statistically significant cluster of BLV sequences with a support coefficient of 90. At the same time, they were grouped together with seven other sequences of the G7 genotype from the Russian Federation (3 pcs), Moldova (3 pcs) and Kazakhstan (1 pcs), deposited in GenBank.

The results of the analysis of samples from the Kochenyovo district of the Novosibirsk region showed that the G7 genotype was found in two of the six villages: 30% of the tested animals from the Prokudskoe village and 12% of the animals from the Razdolnoye farm were carriers of BLV (

Table 1, Fig. 3).

The G4 viruses which we studied in Novosibirsk region were clustered with the G4 BLV genovariants previously isolated from farms in Ukraine, Moldova, Kazakhstan, South Africa, Chile, Belarus, Mongolia, Poland, Belgium, and Argentina. In Kochenyovo district of Novosibirsk region, the G4 genotype was detected in all farms studied where BLV infection was found.

The BLV study identified a significant number of pairs or quadruples of genetically related G4 viruses, grouped into branches with a support factor of 100, that were isolated from cows on a single farm. This confirms the fact that leukemia spreads between animals within a farm.

The prevalence of BLV genotypes G4 and G7 showed significant differences (

Table 2). The range of the proportion of infected animals in farms was from 21.7% to 100% for G4 with a median value of 77.5% [95% CI: 57.55; 100]; the range of the proportion of animals carrying BLV G7 was from 0 to 78.3% with a median value of 22.65% [95% CI: 0; 42.45].

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of a 540 bp long fragment of the BLV env gene performed by the maximum likelihood method.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of a 540 bp long fragment of the BLV env gene performed by the maximum likelihood method.

The evolutionary history was found using a maximum likelihood method based on the Kimura two-parameter model. A discrete gamma distribution was used to model differences in evolutionary rates between sites. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured by the number of substitutions per site. Blue indicates BLV samples collected from private farms in Kochenyovo district; Red indicates samples from Razdolnoye LLC in Kochenyovo district; Green indicates samples from Tatarsk district; Turquoise indicates samples from Bolotnoye district; Light blue indicates samples from Dovolnoye district; Fuchsia indicates samples from Barabinsk district; Yellow indicates samples from Toguchin district. Black indicates BLV reference sequences from the GenBank database.

3.3. Analysis of Nucleotide and Amino Acid Sequences of the BLV

Analysis of nucleotide and amino acid variability was performed for the deciphered BLV fragments of 810 bps in length starting in the gp51 region, which encodes the virion envelope proteins and covers all conformational epitopes and the most significant regions of the env gene.

BLV fragments isolated from 381 samples were included in the comparative analysis of nucleotide variability. 38 env gene sequences from the international GenBank database, including the same region of the env gene, were added to the formed sample. All currently known BLV genotypes presented in the international GenBank database, from genotype G1 to G14, were selected as sequences for comparison. Sequence identity in comparison with genotypes G1 - G14 varied from 92.1% to 100%. Pairwise sequence identity in comparison with genotypes G4 and G7 from our sample, with reference sequences from GenBank, varied from 96.6% to 100% and from 97.4% to 100%, respectively.

Based on the pairwise identity matrix, BLV sequences were found that had 100% identity with each other (

Table 3). Identity for most samples was observed among BLV samples collected in the same area, but there were also samples with 100% identity collected from farms located in different areas of the Novosibirsk region, including significantly remote ones. For example, 6 samples of the G4 genotype collected in the Toguchin district and 3 samples of the same genotype collected in the Tatarsky district had 100% identity (the distance between the farms is about 600 km,

Table 3).

Figure 4.

SDT matrix with color coding of pairwise identity indices obtained by aligning a set of nucleotide sequences of the BLV env gene of the G4 genotypes, as well as reference sequences from the GenBank database. The length of the sequences used to plot the graph is 810 bps.

Figure 4.

SDT matrix with color coding of pairwise identity indices obtained by aligning a set of nucleotide sequences of the BLV env gene of the G4 genotypes, as well as reference sequences from the GenBank database. The length of the sequences used to plot the graph is 810 bps.

Figure 5.

SDT matrix with color coding of pairwise identity indices obtained by aligning a set of nucleotide sequences of the BLV env gene of the G7 genotypes, as well as reference sequences from the GenBank database. The length of the sequences used to plot the graph is 810 bps.

Figure 5.

SDT matrix with color coding of pairwise identity indices obtained by aligning a set of nucleotide sequences of the BLV env gene of the G7 genotypes, as well as reference sequences from the GenBank database. The length of the sequences used to plot the graph is 810 bps.

Further, the studied samples with 100% identity in the nucleotide sequence were excluded from the 381 sequences on the bases of the comparison results. Thus, 61 unique sequences of the BLV env gene were selected for further construction of multiple alignment based on the SDT matrix.

3.4. Mutation Analysis of the Studied Sequences of BLV Isolates

To assess mutational differences in the studied region of the BLV genome, 61 unique nucleotide sequence was translated into the corresponding amino acid sequences. Multiple alignment was performed for the obtained amino acid sequences, which made it possible to identify 54 amino acid substitutions, including 40 among G4 viruses, 14 among G7 (Fig. 5).

Both single mutations occurring in a few percent of cases and amino acid substitutions characteristic of the majority of the studied samples were described.

The distribution of substitutions by functional regions of the viral envelope protein was as follows: 14 substitutions were found in the neutralizing domain (ND), 9 substitutions in the CD8+ T-cell epitope, 6 substitutions in the B epitope, 7 substitutions in the D epitope, 5 substitutions were identified in the TMHR epitope (transmembrane hydrophobic region), and 13 amino acid substitutions were found in the A epitope of the BLV gp51 protein.

Four amino acid positions were found in which substitutions were detected in comparison with the FLK-BLV reference sequence (M35242) among both G4 and G7 BLV variants.

In 97.9% of BLV genotype 4 and 7 samples, the A16T substitution was recorded in the GP51 region, in 1% (only among G7) – A16I and in 1% (only among G4) – the codon corresponded to the reference sequence.

The presence of amino acid A in codon 16 is characteristic of BLV G1 from the USA, for G8 from Ukraine; for G4 viruses circulating in Moldova, Poland, Belgium, France and for G12 BLV, the A16T substitution has been described; among G7 from Moldova, the A16I sequence is common.

Unique, previously undescribed substitutions were found in 379 of 381 studied cases at position K42R (GP51) and in 380 samples – S222L (ND3).

In codon 50 (GP51), the S50F substitution was found in 378 cases. S50F is a substitution characteristic of G7 viruses from Moldova and Russia, for G4 – from Moldova, Africa and France; for G8 from Ukraine, for G10 from Thailand and for G12 from Kazakhstan.

The substitution characteristic of G7 samples was registered in codon A259V in the epitope A region (it was found in 84 of 92 studied samples). A259V was previously described for BLV G7 from Russia and Moldova. In the G4 sampling collection, the codon 259 sequence corresponded to the reference one, similar sequences of BLV G4 were found in Moldova, France and Africa.

Mutations specific to Russian BLV G4 include substitutions at positions S24F (GP51), A41P (GP51), R89H (CD4+ T-cell epitope GP51) and I112T (ND1 GP51).

The S24F substitution is typical for G4 from Moldova and France. The sampling collection of G7 viruses previously studied did not contain a sequence identical to the reference one, which corresponds to previously described G7 variants from Moldova. The A41P substitution has also been previously described for G4s from Moldova, Belgium, France and China.

The amino acid sequence R89H is characteristic of G4 from Moldova, Belgium, Poland, France, Africa and China. The I112T substitution has also been previously described for G4 sequences from Moldova, France and Africa.

Single mutations, registered in several percent of cases (from 0.3 to 3%), were described in different regions of the studied fragment of the env gene, higher amino acid variability among our sample of viruses was observed in the GP51 region, especially the position N18/K/S/E with the predominant distribution of N18K.

Figure 6.

Alignment of the obtained amino acid sequences of the BLV gp51 protein. 61 sequences of BLV strains isolated in the Novosibirsk region of Russia are indicated. The figure highlights differences from the FLK-BLV reference sequences.

Figure 6.

Alignment of the obtained amino acid sequences of the BLV gp51 protein. 61 sequences of BLV strains isolated in the Novosibirsk region of Russia are indicated. The figure highlights differences from the FLK-BLV reference sequences.

4. Discussion

The number of cattle in the Siberian Federal District, which includes the Novosibirsk region, is in second place among all regions of Russia, second only to the Volga Federal District. The number of dairy cows breeds in Siberia is estimated at 1,243,000 heads [

16]. As part of the Novosibirsk Region, it is the Kochenyovo District that is one of the largest agricultural districts, which is among the top five leaders in the production and sale of agricultural products. More than 30% of all employed residents are engaged in agriculture in the district. At the same time, the unfavorable epizootological situation regarding the spread of BLV remains in the Novosibirsk region as a whole, and in Kochenyovo district, in particular.

The first objective of this study was to conduct a comparative assessment of the prevalence of cattle in the Kochenyovo district of the Novosibirsk region in individual farms with 1-2 cows and in the large livestock farm Razdolnoye, which has a large livestock population (more than 10 thousand animals).

The PCR diagnostics performed on a random sample of 200 animals from the Razdolnoye farm revealed BLV DNA in 71.5% of the samples examined.

Individual farms with similar BLV prevalence rates were found both in large settlements with many individual livestock farms and in small villages. The highest livestock prevalence was recorded in individual farmsteads in the villages of Kazakovo (230 residents; 19 tested animals; 68.4% livestock prevalence) and Proskudskoye (5.9 thousand residents; 38 tested animals; 79% livestock prevalence), located geographically far from the Razdolnoye farm. In the farms of the villages of Kochenyovo and Svetly, located near the Razdolnoye farm, the livestock prevalence was significantly lower - 8.3% and 13.3%, respectively. Thus, proximity to a large livestock farm with a high BLV prevalence was not a risk factor associated with the spread of BLV.

BLV DNA was not detected in any of the 18 samples collected in the village of Shagalovo. Shagalovo settlement is the most geographically isolated one, with poor transportation links with other settlements in the Novosibirsk region. Perhaps economic and geographical conditions can partly explain the absence of BLV among cattle in this settlement. No connection was found between the frequency of BLV DNA detection and the breed of the animal.

The described higher prevalence of livestock in large livestock farms compared to small farms is consistent with data obtained in a number of other studies [

16], which once again indicates the difficulty of observing sanitary anti-epizootic measures to prevent ingress of infection of animals within large livestock farms.

The reasons for the high prevalence of BLV in the Razdolnoye farm, according to veterinary specialists, were the low quality of diagnostics (untimely and incorrect use of certain methods, such as ELISA diagnostics of calves), insufficient control over the sterilization of medical instruments used in veterinary procedures, and violation of sanitary requirements when tattooing and piercing the ears of cattle. In addition to horizontal routes, transmission of the infection was observed during calving and through milk when feeding calves. Early diagnostics of calves was not performed in Razdolnoye, all young animals were kept without culling/separate keeping of sick animals. Following the study, a BLV elimination plan was developed and implemented at the Razdolnoye farm, including early repeat PCR diagnostics of calves, carefully developed logistics for separating animal and personnel flows, monitoring compliance with anti-epizootic measures to prevent infection of animals both in stalls and with grazing in the summer months, which began to yield tangible results in improving the health of the herd of animals [

16].

Sequencing studies of BLV in Russia are very limited. The second objective of our study was to investigate the genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships of the BLV population circulating in the Novosibirsk region of Russia. To increase the sample collection scope of BLV, the next stage of this study included additional blood collection from animals positive for the immunodiffusion reaction for BLV infection, kept in large livestock farms in five remote districts of the Novosibirsk region: Bolotnoye, Tatarsk, Toguchin, Barabinsk and Dovolnoye.

Thus, in this study, we report a molecular genetic analysis of BLV sequences obtained from infected cattle from six remote areas of the Novosibirsk region. We focused on the analysis of the region of the env gene encoding the gp51 peptide, as this fragment is the most studied region of the BLV genome and allows for genotyping and sub genotyping of virus strains.

The most common genotypes are G4, G7 and G8 in the Russian Federation [

16]. According to the Ministry of Veterinary and Phytosanitary Surveillance, the characteristic genotypes of BLV are G1, G4, G7 and G8 for the European part of Russia. The appearance of the G1 genotype in the European part of Russia could be the result of the purchase of cattle primarily from the USA, where the G1 genotype was predominant [

29].

The Novosibirsk region of Russia is no exception. It has been shown that the G4 and G7 BLV genotypes are currently spreading in the cattle population in Siberia. Among 417 samples examined, 77.9% belonged to genotype 4, 22.1% to genotype 7 BLV. At the same time, the prevalence of the virus genotypes was uneven: in 5 of the 6 examined districts of the Novosibirsk region, G4 BLV prevailed, while the G7 BLV genotype prevailed only in the Toguchin district (78.3% of infected animals). In the Kochenyovo district, where blood was collected from animals kept on farms in 6 different settlements, G7 was found in only two settlements - in 13.5% of cattle on the large Razdolnoye farm and in 30% of animals in the village of Proskudskoye (where there are a large number of individual farms), territorially remote from the Razdolnoye farm.

The greatest differences in the prevalence of BLV genotypes were found in the farms of Bolotnoye (G7 – 0%, G4 – 100%) and Toguchin districts (G7 – 78.3%, G4 – 21.7%). It is interesting that of all the farms included in the study, only these districts border each other, the distance between the farms is about 60 km (Fig. 2). The distance of 60 km can be considered a small distance compared to the territorial remoteness between other farms included in the study, located at a distance of 180 km to 600 km from each other.

Phylogenetic analysis performed for the decoded BLV env sequences indicates the closeness of Siberian bovine leukemia viruses to the virus population circulating in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, the CIS (Poland, Belgium, France, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Ukraine). The described characteristics of the studied BLVs correspond to the previously described initial stage of the spread of bovine leukemia in Russia. According to Vafin R.R. et al., Rola-Łuszczak M. et al., BLV spread in Russia due to the import of breeding cattle in 1945-1947 from Germany to farms in Western Siberia, Moscow, Leningrad and Kaliningrad regions [

25,

26]. Subsequently, leukemia spread to most regions of Russia [

30].

The separate phylogenetic clusters of BLV for genotype 7 described in this study indicate that different representatives of BLV genotype 7 were repeatedly imported to the Novosibirsk region of Russia.

As a result of phylogenetic analysis, several separate clusters of BLV isolates were identified within the studied G 4 and G 7. Analysis of the obtained sequences taking into account the sampling area shows that most of the genetically close BLV isolates for each virus genotype were isolated from cows located in the same locality or farm. However, some clusters of close BLV isolates were obtained from animals from remote farms.

An analysis of the phylogenetic relationships of BLV allows us to conclude that BLV in the Novosibirsk Region mainly circulates within individual settlements and rarely goes beyond their borders. The transmission of the virus may be due to joint grazing of livestock on common pastures. An additional factor in the spread of BLV between farms may be the acquisition of breeding cattle, which may be carriers of the virus without pronounced clinical manifestations of infection [

31].

BLV genotypes 4 and 7 isolated in Russia, including those described in this study, represent specific phylogenetic groups of viruses located separately from BLV representatives of the same genotypes isolated in other countries of the world. The described situation with the epizootic of BLV genovariants 4 and 7 in Russia and in the Novosibirsk region supports the general concept of the spread of BLV genotypes in the world [

4,

17].

Pairwise alignment of the deciphered nucleotide sequences of BLV variants with the reference sequences of bovine leukemia virus from GeneBank showed a fairly high degree of identity of the studied G4 viruses - from 97.3 to 100%, which is natural, since the overall variability within the G4 genotype is one of the lowest compared to other BLV genotypes (the average distance between nucleotides is 0.011 ± 0.002) [32, 33]. In the case of the G7 genotype of BLV, about 16 isolates under study represented a separate group of viruses with a low level of similarity both to the BLV reference sequences and to the rest of the viruses represented in the sample.

When comparing the predicted amino acid sequences of the studied BLVs with the reference sequence of the FLK-BLV env gene, 54 amino acid substitutions were found that were characteristic of the studied BLV samples. The greatest amino acid variability among the studied BLV sample was observed in the GP51 region, in the neutralizing domain, in the epitope A of the BLV gp51 protein of the studied env gene fragments. The leader peptide of the envelope plays an important role in the incorporation of the Env protein into emerging virions, since it is primarily responsible for the transport of the polypeptide into the endoplasmic reticulum of infected cells. For another known retrovirus (HIV-1), it was shown that some mutations in its signal peptide can be associated with viral infectivity [

34]. Many authors have noted the function of the neutralization domain (ND) of the surface protein, associated with the penetration of the virus into the cell and interaction with neutralizing antibodies, which determines the immunogenicity of this region of the Env protein [

29]. In the ND domain of the BLVs we studied, a mutation I112T was described, previously also described by other authors [

12,

16]. The amino acid substitution I112T(ND) was characteristic of 30 samples of the G4 BLV genotype, although this mutation is noteworthy in that it occurs among the G7 genotype. Mutation A259V in the A epitope was exclusively among the 7th BLV genotype, which is quite conservative.

Point substitutions were noted during the analysis that were found only in individual BLV samples. A number of amino acid substitutions in the BLV genome, found within the DD’ epitopes and epitope A, may be involved in the development of infectivity. The S254L substitution, described in many studies, prevents the formation of syncytia with a simultaneous disruption of the expression of surface glycoproteins [

35]. Since all substitutions in specific samples, even point ones, are located near this region, it can be assumed that these substitutions may affect the immunostimulatory and fusogenic properties of the virus [

29,

35].

The K248N substitution is present in 13 of 174 G4 samples, this mutation is characteristic of our samples and is not found in any reference sample. This mutation is located in the GP51 gene region of the main structural protein of the env gene region. In 379 of 381 BLVs studied, a unique, previously undescribed substitution was found at position K42R (GP51) and in 380 samples – a unique S222L substitution (ND3).

The identified differences in the amino acid sequences of the bovine leukemia virus may indicate significant intraspecific variability of BLV, as well as the possible influence of additional evolutionary mechanisms on the formation and divergence of virus genotypes. Previously undescribed mutations at position N18K/S/E/I, detected in 14 samples, and N10S/K/T, detected in 5 samples are of particular interest. These substitutions require additional study, since they were found in BLV isolates obtained from animals originating from different geographic areas where animals do not interact with each other. It is also worth noting that these mutations are not associated with any particular BLV genotype. This fact may indicate the evolutionary or epidemiological significance of these mutations.

Previously, 110 Russian BLV sequences were deposited in the international database. As a result of our study, 320 new sequences of the env gene of BLV genotypes 4 and 7 circulating in the Novosibirsk region were deposited, which makes a significant contribution to the study of molecular epidemiology and molecular genetic characteristics of BLV strains circulating in the territories of the Russian Federation.

Further molecular-epidemic analysis will allow not only to understand the ways of BLV spreading, but also to describe its antigen diversity, which is necessary for the development of preventive measures, implementation of effective measures for the health improvement of cattle not only for large agricultural enterprises, but also for private farmsteads in Russia.