1. Introduction

Bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD) is a serious threat to cattle worldwide (Son et al., 2022). The responsible pathogen exists primarily in two species: bovine viral diarrhea virus comprises two species: Pestivirus tauri (BVDV-1) and Pestivirus bovis (BVDV-2). Both are enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses that fall under the genus Pestivirus within the Flaviviridae family (ICTV, 2021). Their genome is organised into a single open reading frame (ORF), which translates into four structural and eight non-structural proteins. This ORF is bordered by untranslated regions (UTRs) at both the 5′ and 3′ extremities (Zhao et al., 2023). To date, researchers have identified 21 BVDV-1 subtypes (ranging from 1a to 1u) and 4 BVDV-2 subtypes (2a to 2d) (Mirosław & Polak, 2019). Given the limited availability of complete genome data, genotyping relies primarily on 5′-UTR sequences available in public databases (Giangaspero & Zhang, 2023). Both BVDV-1 and BVDV-2 can be found in two biotypes: non-cytopathic (NCP), responsible for the majority of infections and the establishment of persistent infections (PI) and the cytopathic (CP) biotype, developed from NCP and linked with mucosal disease (De Oliveira et al., 2020; Madeddu et al., 2021). Transmission is through direct contact and indirect exposure through contaminated surfaces, feed, aerosols, and fomites (Bisschop et al., 2025). Infection may lead to clinical manifestations, that vary from subclinical to acute haemorrhagic syndrome and lethal mucosal disease. BVDV induces immunosuppression, which aggravates clinical signs, particularly in the presence of concurrent infections (Mirosław & Polak, 2019). Exposure of pregnant, seronegative dams during 40 to 120 days of gestation, commonly leads to the delivery of calves that are persistently infected (PI). They harbour the virus during their lifetime and continuously shed it, confirming the persistence and ongoing spread of BVDV in the herd (Mirosław & Polak, 2019). Although PI animals may live to adulthood without obvious clinical signs, they are more disposed to subsequent disease, (Adkins et al., 2024; Köster et al., 2024). (Ferreira et al., 2024; Su et al., 2023).. Currently, approximately 96% of Algerian farms raise imported cattle, with Prim’ Holstein accounting for 75% of the population and Pie-Rouge des Plaines making up a further 20% (Mostefa & Mounia, 2024). Approximately 35.1% of cows were classified as cachectic (body condition score (BCS) ≤2 on a 0 to 5 scale) (Kechroud et al., 2024). Furthermore, several research efforts have demonstrated the presence of BVDV and its epidemiological patterns among various animal populations in Algeria Guidoum et al., 2020). However, no regulated or compulsory program has been established to eradicate BVDV in Algeria. This work aimed to define the prevalence of BVD in cachectic cows in the Tiaret province and to explore a potential possible association between BVDV infection and cachexia. Our examination of existing studies suggests that this is the first research in Algeria to focus on the the possible contribution of BVDV to the development of cachexia. This study seeks to fill this critical knowledge gap by employing serological and molecular methods to detect BVDV in cachectic animals and to elucidate the virus’s potential role in weight loss and metabolic disturbances.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

This study involved 100 cachectic cattle of both sexes, from 10 herds (

Table 1). The animals included local, imported, and predominantly crossbreeds from Tiaret province in northwestern Algeria (

Figure 1). Sampling focused on the cachectic subgroup within each herd, regardless of herd size. Animals were selected based on clinical evaluation in ten herds. Cachexia was identified by a poor body condition score of ≤2 on a 0 to 5 scale as previously described (Edmonson et al., 1989).

2.2. Blood sample collection

A total of 100 blood samples were collected from the animals described above. After collection, the samples were delivered to the Institute of Veterinary Sciences in Tiaret, where serum separation was carried out by centrifugation at 1500 g for 10 minutes. The recovered serum was decanted and stored at –20 °C. Finally, the samples were transported in an icebox to the Institute of Veterinary Medicine of Serbia in Belgrade, for molecular and serological analyses, according to the international regulations governing the transport of biological materials.

2.3. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for BVDV detection

The commercially available ID Screen® BVD p80 Antibody Competition ELISA kit (Innovative Diagnostics, Grabels, France) was used to detect antibodies against the p80 (NS3) protein in serum samples. The competitive ELISA assay demonstrated full sensitivity and specificity, each measured at 100% (Assunção et al., 2022). The test and result interpretation were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The optical density was measured with a microplate reader (Multiskan MS LabSystems® Microplate Reader, Vantaa, Finland).

2.4. RNA extraction and RT-PCR

Nucleic acid was extracted from 200 µl of each serum sample using the IndiMag® Pathogen Kit (QIAGEN for INDICAL BIOSCIENCE Leipzig, Germany) with the IndiMag 48s (INDICAL) extraction system. Amplification of viral RNA was conducted using the Luna Universal One-Step RT-qPCR Kit (New England Biolabs, NEB) ® on an Applied Biosystems Quant Studio 3 Real-Time PCR System. Briefly, the amplification was carried out in a 12.5 µl reaction volume assembled on ice (2.5 µl template RNA per sample in combination with 10 µL of Reaction mix, which includes 0,4 µl of each primer (10 µM) and 0,2 µl of probe (Hoffmann et al., 2006).

The thermal included a single reverse transcription step at 55 °C for 10 minutes, followed by initial denaturation at 95 °C for 1 minute. This was succeeded by 50 amplification cycles consisting of denaturation at 95 °C for 10 seconds and a combined annealing and extension phase at 60 °C for 30 seconds. Samples with a Ct value below 45 were classified as positive.

RT-qPCR positive samples were subjected to conventional gel-based RT-PCR aiming to generate amplicons for amplification and sequencing of the 5`UTR region, using QIAGEN One Step RT-PCR Kit (Qiagen, Germany) and primers 324-F 5′-ATGCCCWTAGTAGGACTAGCA-3′ and 326-R 5′-TCAACTCCATGTGCCATGTAC-3′, amplifying ~288 bp and 299 bp region (Vilček et al., 1994). The reaction mixture was consisted of 2 µl of template and 18 µl of master mix (6 µl RNase-free water, 0.8 QIAGEN One Step RT-PCR Enzyme Mix, 4 µl 5x QIAGEN One Step RT-PCR Buffer, 0.8 µl dNTP Mix, 4 µl 5x Q-Solution, 1.2 µl of each primer (10 µM), and 2 µl template). RT-PCR products were analysed in a 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide and visualised under UV light after gel electrophoresis, and PCR products of specific length (263 base pairs) were sent to LGC Germany for sequencing.

2.5. Phylogenetic analysis of BVDV

Phylogenetic analysis was initiated by comparing the attained nucleotide sequences with reference sequences available in GenBank using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) to identify closely related strains. Representative sequences showing the highest similarity were selected for inclusion in the analysis. Multiple sequence alignment was performed with ClustalW, and phylogenetic trees were inferred using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method implemented in MEGA X. The most appropriate nucleotide substitution model was established with the MEGA X Find Best DNA/Protein Models feature, and evolutionary distances were calculated according to the Tamura-Nei model. The reliability of the phylogenetic tree topology was assessed by performing 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

2.6. Virus isolation:

BVDV isolation from RT-qPCR-positive samples was carried out in Madin-Darby Bovine Kidney (MDBK, ATCC CCL-22) cell culture. The cells were cultured in Gibco DMEM/F-12 GlutaMAX ™ medium (Fisher Scientific, Vantaa, Finland), enriched with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) for essential nutrients and MycoZap® (Basel, Switzerland) to avoid contamination. Serum samples (100 µl) were inoculated into an 80% MDBK confluent layer of 24 24-well plate and incubated for 7 days at 37 °C with 5% CO2. As BVDV is typically non-cytopathic, Immunoperoxidase Monolayer Assay (IPMA) was conducted on cells after the first passage, by the WOAH protocol (WOAH, 2021) Negative samples were subjected to the next passages; in total, 3 passages were conducted.

2.7. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using the R software (version 4.5.1), including overall seroprevalence, herd-level seroprevalence and within-herd prevalence rates. True prevalence was determined using the formula described by (Stevenson, 2008).

The ELISA test used in this study was very sensitive and specific, with a score of 100% for both (Assunção et al., 2022).

BVDV prevalence was also calculated separately by age group and sex. The Wilson score method was employed to estimate 95% confidence intervals for the proportion, and Fisher's exact test was performed. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. ELISA for BVDV antibody detection

Out of 94 serum samples, 88 animals (93.62%) were seropositive for BVDV antibodies, 4 (4.26%) were seronegative, and 2 (2.13%) had doubtful results. For precision in prevalence estimation, only samples with clear-cut results (positive or negative) were included to estimate seroprevalence. Out of 92 valid results, the true seroprevalence was the same as the apparent prevalence and estimated at 95.65%. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of the adjusted prevalence was estimated by the Wilson score method and ranged from 89.7% to 98.4%. Overall herd-level seroprevalence was 100%; all the herds contained at least a single BVD-positive animal. Within herd-level seroprevalence of BVDV was high in all ten herds examined (

Table 02), with herds (2, 3, 4, 6, 7, and 9) recording 100% seropositivity. Slightly lower levels were found in Herd 1 (88.9%), Herd 5 (90.0%), Herd 8 (91.0%), and Herd 10 (90.0%).

Similarly, when classified by sex, BVDV prevalence was 94.74% (95% CI: 87.23–97.93%) in females and 100% in males (95% CI: 80.64–100%). These results indicate a general exposure to BVDV across all age groups and sexes (

Table 3), with no statistically significant differences between groups (p > 0.05).

3.2. RT-qPCR and sequencing

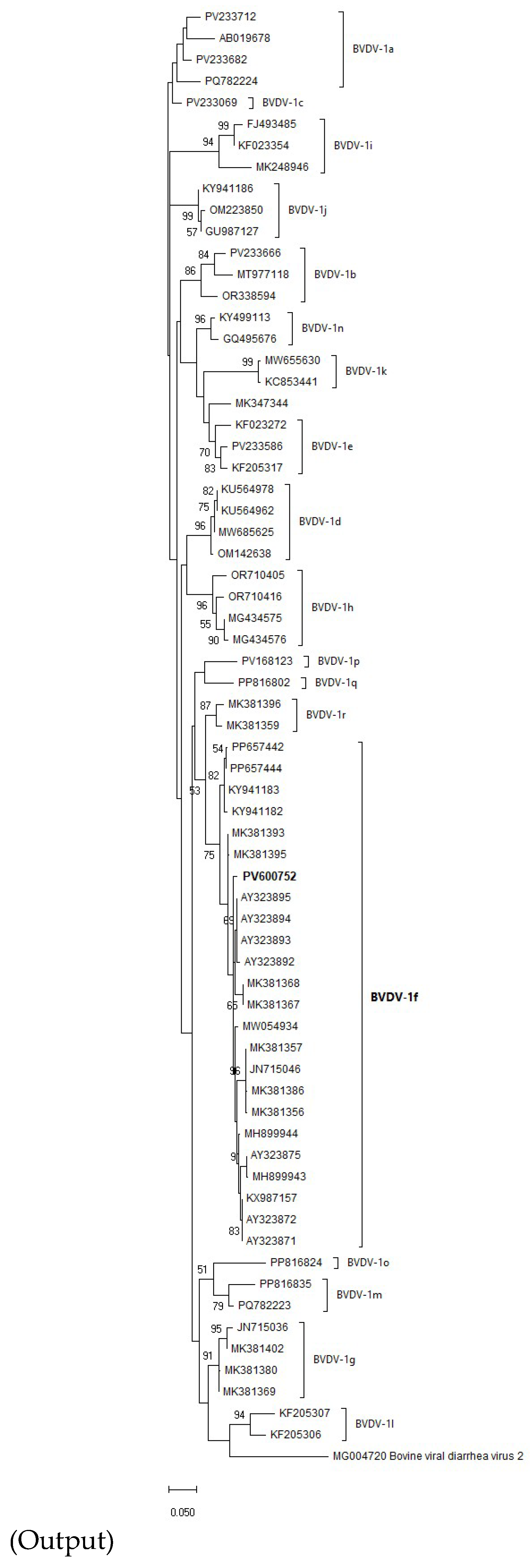

Out of 100 tested samples for BVDV, 10 were BVDV-1 positive based on RT-qPCR. Among these, 2 samples exhibited distinct bands on gel-based RT-PCR at the predicted size and were selected for Sanger sequencing. The obtained 263-bp 5′UTR sequences showed 100% nucleotide identity; therefore, only one representative sequence was deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under accession number PV600752. Phylogenetic analysis (

Figure 2), performed in MEGA X using the Maximum Likelihood method with the Tamura-Nei model and 1,000 bootstrap replicates, revealed that the virus belongs to the BVDV-1f subtype. The sequence clustered with high bootstrap support (≥90%) alongside strains MK381368 and MK381367 from Poland. Bootstrap support values were shown next to the branches, with only those ≥50% displayed. These findings confirm the circulation of BVDV-1f subtype in Algeria, in agreement with nucleotide distance analysis (see Supplementary Output).

3.2. Virus isolation

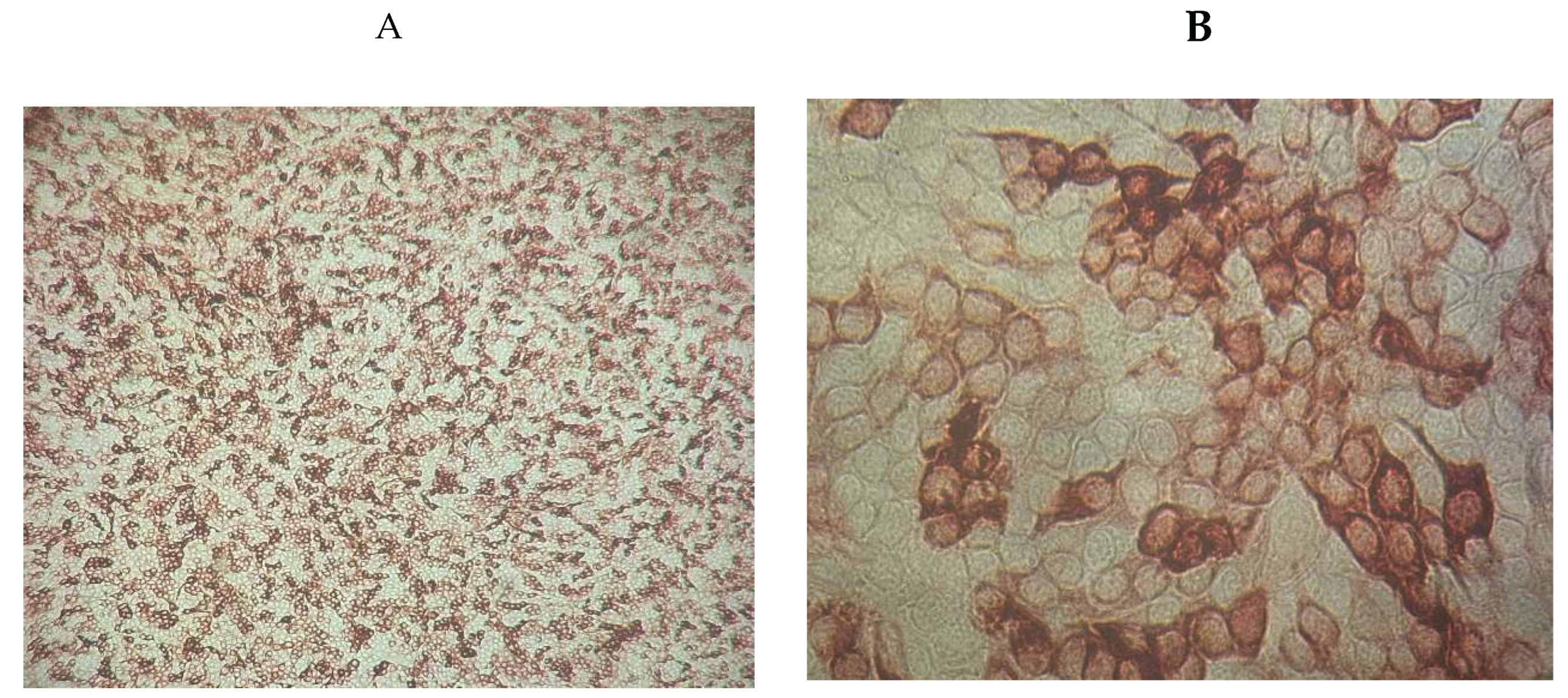

IPMA revealed specific immunostaining in 2 out of 10 isolates. Notably, no cytopathic effects were observed, confirming the presence of the antigen and the absence of associated cellular damage.

Figure 3.

Immunoperoxidase staining of MDBK cells infected with NCP BVDV (A ×100) and (B×400).

Figure 3.

Immunoperoxidase staining of MDBK cells infected with NCP BVDV (A ×100) and (B×400).

4. Discussion

Bovine pestiviruses appear to be widely distributed across North Africa, affecting various domestic animal species (Guidoum et al., 2020). Although surveillance reports are still unavailable, previous studies suggest that BVDV serotypes are widespread and circulate across a large geographical area (Alali et al., 2024; Elkhoja et al., 2024; Guidoum et al., 2020; Saidi et al., 2018). In our study, we used an ELISA to detect BVDV-specific antibodies, RT-PCR to detect viral RNA and virus isolation in cell culture for the recovery of viable viral strains. Our results revealed a notably high seroprevalence (93.62%), indicating that the examined animals were exposed to BVDV on a large scale, raising worries about continued viral circulation. At the herd level with the seroprevalence was 96%. Conversely, 4.26% of samples were negative, suggesting that a tiny part of the population did not show an immune response.

The high seroprevalence , contrasts sharply with earlier findings about BVDV in Algeria where Derdour et al. (2017), revealed a very low seroprevalence of (1.39%) and that can largely be explained by their focus on intensively managed dairy herds, whereas our study examined animals from traditional farming systems, which present 70% of the total number of farms in the country (FAO, 2025), and characterised by mixed species grazing, frequent introduction of new stock and minimal biosecurity, tend to facilitate viral exposure and persistence (Zirra-Shallangwa et al., 2022). Guidoum et al. (2020) reported a seroprevalence of 59.9% at the population level and 93.5% at the herd level in the same study area. Similarly, our findings confirm a high level of BVDV seroprevalence, consistent with their observations and reinforcing evidence of the widespread presence of the infection in the region. The high seroprevalence supports the efficient transmission of BVDV in closed livestock systems, where close contact between animals facilitates viral dissemination (Guidoum et al., 2020; Zirra-Shallangwa et al., 2022).

Adults showed an elevated seroprevalence of BVDV compared to younger animals. This aligns with other studies (Aragaw et al., 2018; Elkhoja et al., 2024; Nigussie et al., 2010) that have observed elevated seroprevalence rates in older age groups, and may be related to cumulative exposure over time, where older individuals have had more chances to be exposed to BVDV in their lifetime. Therefore, the measured antibody prevalence reflects the amount of animals that have been exposed to BVDV at some point in their lives (Houe, 1995). BVDV seroprevalence was 100% in males and 94.7% in females. While this contrasts with Elkhoja et al. (2024), who found elevated prevalence in females, it aligns with Lotuffo et al. (2013) and Nigussie et al. (2010), who found higher rates in males. The difference may reflect greater exposure of breeding males, though the small male sample size could have led to overestimation. Despite these variations, no statistically significant sex- or age-related differences were observed, likely due to the high overall prevalence.

The interpretation of the ELISA and RT-PCR results indicates that the identification of viral RNA in seronegative animals strongly suggests the presence of persistently infected (PI) animals. This aligns with Goens (2002), who noted that PI calves do not produce a detectable antibody response to BVDV due to immunological tolerance to the virus acquired in utero. According to Goens (2002) and Orban et al. (1983), the best way for confirmation of PI status is the combination of PCR or virus isolation results with the absence of BVDV antibodies. Conversely, transiently infected animals may no longer test positive by PCR once their immune system has cleared the virus. Among the ten animals testing positive by RT PCR, nine also had detectable antibodies by competitive ELISA, reflecting either recent or past acute infections, while one calf aged <1 year was RT-PCR positive yet seronegative. Normally, calves at this age should still have antibodies from their mother’s colostrum, which protect them for the first 4–6 months. The fact that this calf was seronegative but still had virus in its blood strongly suggests it was persistently infected (PI), since PI animals carry the virus for life but fail to produce antibodies. Similar results were reported by Brinkhof et al. (1996).

Although only one animal was confirmed as PI, making it unlikely that BVDV alone explains the cachexia we saw. However, the virus’s immunosuppressive effects may predispose animals to secondary infections or exacerbate existing diseases (Lanyon et al., 2014; Mirosław & Polak, 2019). In the Tiaret region, multiple studies have reported diseases commonly associated with cachexia, such as Paratuberculosis (Hemida & Kihal, 2015) and various parasitic infections (Boulkaboul, 2003; Kouidri et al., 2012), leading to marked weight loss. Furthermore, BVDV may lead to weight loss not only through direct effects on the host immune system but also by increasing susceptibility to respiratory or gastrointestinal infections (Houe, 1995).

Our findings match previous studies showing that BVDV is widely distributed across North Africa, though the considerable variability in seroprevalence by country. Elkhoja et al. (2024) noted low prevalence in Tunisia (11.8%) and moderate prevalence in Libya (48.6%). Alali et al. (2024) reported 56.1% seroprevalence in Morocco. Such heterogeneity would be the result of variation in animal movement patterns, biosecurity deficiencies, and the lack of harmonised control programs. Nevertheless, it confirms that BVDV is endemic throughout North Africa. (Thabti et al., 2005) have documented both BVDV-2a and BVDV-1b circulating in Tunisia. To date, molecular sequencing data remain unavailable for Moroccan and Libyan BVDV isolates, underlining the need for targeted genetic surveillance in these regions. The detection of different BVDV subtypes in two different studies suggests that increasing prevalence is associated with the emergence of new viral lineages, which reinforces the need to extend surveillance to additional regions.

Virus isolation in cell culture was applied and two non-cytopathogenic BVDV strains were isolated, which provided further confirmation of the presence of infectious virus in the selected animals. All BVDV isolates obtained from cell cultures were classified as non-cytopathogenic (NCP) strains. This aligns with previous findings showing that NCP biotypes are more commonly found in nature than cytopathogenic (CP) strains (Ridpath, 2010). These findings support the likelihood that the animals were either PI or in early transient infection stages, without showing signs of mucosal disease. However, given the rapid mutation rate of RNA viruses such as BVDV, the emergence of CP strains cannot be excluded (Peterhans et al., 2010; Ridpath, 2010).

As suggested by Köster et al. (2024), wildlife may contribute to BVDV transmission. Wild boar (Sus scrofa), which are prevalent in northern forests (Zeroual et al., 2018) and have been shown to carry BVDV in Serbia (Milićević et al., 2018), represent a potential risk factor that could hinder the eradication of BVDV in domestic cattle. In Algeria, multi-species herding (Far & H Yakhler, 2015), a scarcity of data on pestiviruses in wild ruminants (Guidoum et al., 2020) and the high adaptability of pestiviruses to multiple hosts (Mirosław & Polak, 2019) may partly explain the high prevalence observed in our study. This study is the first to report BVDV-1f strain in Algeria. Although Guidom et al. (2020) previously identified BVDV-1a in Algerian cattle, our molecular analysis revealed that the two isolates characterised in this study belong to the 1f lineage, a genotype that has not been documented in the region before. Notably, these 1f strains showed the highest genetic similarity to isolates reported in Poland, suggesting a circulation of previously unknown strains. This subtype is most frequently reported in Germany and Slovenia, and is thought to be common in Europe (Mirosław & Polak, 2019). Although no BVDV vaccines are currently in use in Algeria, antigenic variation between subtypes is still an important factor in the success of future eradication programmes. The recognition of BVDV-1f in this study emphasises the importance of accounting for this subtype when devising future control and vaccination strategies in Algeria.

The comparison to previous research affirms the need for epidemiological surveillance to better understand the development of BVDV and its effect on cattle health. In areas where BVDV is widespread and poorly controlled, transient infection is almost inevitable at some point in an animal's life. This highlights the importance of taking a combined approach using both ELISA and PCR tests to accurately identify infected animals and develop effective control measures, such as rigorous biosecurity measures, targeted vaccination programs, and early diagnostic techniques to reduce BVDV infection in cattle herds.

The relatively small sample size may not accurately represent the epidemiological differences between regions or production systems. Future studies should involve a large sample size, and tests for a wider range of pathogens related to cachexia in cattle.

5. Conclusion

Although the elevated prevalence of BVDV antibodies observed in this study was not associated with cachexia, a comparison with previous Algerian research highlights the lack of current control measures for preventing and eliminating BVDV. Given the limited number of studies on BVDV performed in Algeria, this study serves as an important reference for further research. It is crucial to identify the specific strains present in the local cattle population, such as in the Tiaret province. In addition, Genetic characterisation aids in the invention of targeted vaccination and monitors the possible introduction of virulent genotypes that may aggravate the potential clinical and financial impact of the disease.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.M. and N.G.; methodology, V.M and L.V.; validation, D.G.; formal analysis, S.Š. and L.V; investigation, N.G.; resources, V.M.; data curation N.G.; writing—original draft preparation, N.G.; writing—review and editing, V.M.; visualization, A.B.; supervision, H.H.; project administration, V.M.; funding acquisition, V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by the Serbian Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation (Contract No 451-03-136/2025-03/ 200030).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the absence of a formal animal ethics committee in Algeria. The study involved only blood sampling, which was carried out by trained personnel, using minimally invasive techniques and in accordance with international animal welfare guidelines and good veterinary practices.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available from the corresponding author by reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The sequence PV600752 has been generated through the Sanger Sequencing Services of the Animal and Health Sub-program of the Joint FAO/IAEA Centre in Vienna, Austria.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BVD |

Bovine Viral Diarrhoea |

| BVDV |

Bovine Viral Diarrhoea Virus |

| CP |

Cytopathogenic |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| IPMA |

Immunoperoxidase Monolayer assay |

| NCP |

Non cytopathogenic |

| RT-PCR |

Real time PCR |

References

- Adkins, M.; Moisa, S.; Beever, J.; Lear, A. Targeted Transcriptome Analysis of Beef Cattle Persistently Infected with Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus. Genes 2024, 15, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alali, S.; Laabouri, F. Z. , Choukri, I., Outenrhrine, H., El Ghourdaf, A., & El Berbri, I. Bovine Respiratory Disease: Sero-Epidemiological Surveys in Unvaccinated Cattle in Morocco. World’s Veterinary Journal 2024, 14, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragaw, K.; Sibhat, B.; Ayelet, G.; Skjerve, E.; Gebremedhin, E. Z. , & Asmare, K. Seroprevalence and factors associated with bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) infection in dairy cattle in three milksheds in Ethiopia. Tropical Animal Health and Production 2018, 50, 1821–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunção, S.F. V. , Antos, A., Barbosa, J. D., Reis, J. K. P., Larska, M., & Oliveira, C. H. S. Diagnosis and phylogenetic analysis of bovine viral diarrhea virus in cattle (Bos taurus) and buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) from the Amazon region and Southeast Brazil. Pesquisa Veterinária Brasileira 2022, 42, e06955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisschop, P.I. H. , Strous, E. E. C., Waldeck, H. W. F., Van Duijn, L., Mars, M. H., Santman-Berends, I. M. G. A., Wever, P., & Van Schaik, G. Risk factors for the introduction of bovine viral diarrhea virus in the context of a mandatory control program in Dutch dairy herds. Journal of Dairy Science 2025, 108, 821–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulkaboul, A. Parasitisme des tiques (Ixodidae) des bovins à Tiaret, Algérie. Revue d’élevage et de médecine vétérinaire des pays tropicaux 2003, 56, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkhof, J.; Zimmer, G.; Westenbrink, F. Comparative study on four enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays and a cocultivation assay for the detection of antigens associated with the bovine viral diarrhoea virus in persistently infected cattle. Veterinary Microbiology 1996, 50, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, L. G. , Mechler-Dreibi, M. L., Almeida, H. M. S., & Gatto, I. R. H. Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus: Recent Findings about Its Occurrence in Pigs. Viruses 2020, 12, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derdour, S.-Y.; Hafsi, F.; Azzag, N.; Tennah, S.; Laamari, A.; China, B.; Ghalmi, F. Prevalence of the main infectious causes of abortion in dairy cattle in Algeria. Journal of Veterinary Research 2017, 61, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmonson, A. J. , Lean, I. J., Weaver, L. D., Farver, T., & Webster, G. A Body Condition Scoring Chart for Holstein Dairy Cows. Journal of Dairy Science 1989, 72, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhoja, H.; Buishi, I.; Brocchi, E.; Grazioli, S.; Mahmoud, A.; Eldaghayes, I.; Dayhum, A. The first evidence of bovine viral diarrhea virus circulation in Libya. Veterinary World 2024, 1012–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO (2025). Algeria | Family Farming Knowledge Platform. https://www.fao.org/family-farming/countries/dza/en/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Far, Z. & H Yakhler. (2015). Typology of cattle farming systems in the semi-arid region of Setif: Diversity of productive directions? http://www.lrrd.cipav.org.co/lrrd27/6/far27117.html.

- Feknous, N.; Hanon, J.-B.; Tignon, M.; Khaled, H.; Bouyoucef, A.; Cay, B. Seroprevalence of border disease virus and other pestiviruses in sheep in Algeria and associated risk factors. BMC Veterinary Research 2018, 14, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J. S. , Baccili, C. C., Nemoto, B. S., Vieira, F. K., Sviercoski, L. M., Ienk, T., Pagno, J. T., & Gomes, V. Biosecurity practices associated with bovine viral diarrhea virus infection in dairy herds in Brazil. Ciência Rural 2024, 54, e20230679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giangaspero, M.; Zhang, S. Pestivirus A Bovine viral diarrhea virus type 1 species genotypes circulating in China and Turkey. Open Veterinary Journal 2023, 13, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goens, D. The evolution of bovine viral diarrhea: A review. The Canadian Veterinary Journal 2002, 43, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guidoum, K. A. , Benallou, B., Pailler, L., Espunyes, J., Napp, S., & Cabezón, O. Ruminant pestiviruses in North Africa. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2020, 184, 105156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemida, H.; Kihal, M. Detection of paratuberculosis using histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and ELISA in West Algeria. Comparative Clinical Pathology 2015, 24, 1621–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, B.; Depner, K.; Schirrmeier, H.; Beer, M. A universal heterologous internal control system for duplex real-time RT-PCR assays used in a detection system for pestiviruses. Journal of Virological Methods 2006, 136, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houe, H. Epidemiology of Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 1995, 11, 521–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICTV (2021). Pestivirus—Flaviviridae. International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). https://ictv.global/report/chapter/flaviviridaeport/flaviviridaeport/flaviviridae/pestivirus.

- Kechroud, A. A. , Merdaci, L., Aoun, L., Gherissi, D. E., & Saidj, D. Welfare evaluation of dairy cows reared in the East of Algeria. Tropical Animal Health and Production 2024, 56, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köster, J.; Schneider, K.; Höper, D.; Salditt, A.; Beer, M.; Miller, T.; Wernike, K. Novel Pestiviruses Detected in Cattle Interfere with Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus Diagnostics. Viruses 2024, 16, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouidri, M.; Khoudja, F. B. , Boulkaboul, A., & Selles, M. (2012). PREVALENCE, FERTILITY AND VIABILITY OF CYSTIC ECHINOCOCCOSIS IN SHEEP AND CATTLE OF ALGERIA. 3.

- Lanyon, S. R. , Hill, F. I., Reichel, M. P., & Brownlie, J. Bovine viral diarrhoea: Pathogenesis and diagnosis. The Veterinary Journal 2014, 199, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotuffo, Z.M. N. , Pérez, M. B. B., Díaz, M. A. H., & Reina Tibisay Escobar Ladrón de Guevara. Seroprevalencia de la diarrea viral bovina en rebaños lecheros de dos municipios del estado Barinas, Venezuela. 2013, 33, 162–168. [Google Scholar]

- Madeddu, S.; Marongiu, A.; Sanna, G.; Zannella, C.; Falconieri, D.; Porcedda, S.; Manzin, A.; Piras, A. Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus (BVDV): A Preliminary Study on Antiviral Properties of Some Aromatic and Medicinal Plants. Pathogens 2021, 10, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milićević; V; Maksimović-Zorić; J; Veljović; Lj, K. u.r.e.l.j.u.š.i.ć.; B; Savić; B; Cvetojević; Đ; Jezdimirović; N; Radosavljević; V Bovine viral diarrhea virus infection in wild boar. Research in Veterinary Science 2018, 119, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirosław, P.; Polak, M. Increased genetic variation of bovine viral diarrhea virus in dairy cattle in Poland. BMC Veterinary Research 2019, 15, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostefa, M.; Mounia, H. (2024). Typology and practices of dairy cattle farming in northwestern Algeria.

- My Maps. (2025). Google My Maps. https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/edit?mid=1WF2QP6iQZibXhbgI30oMgdtXDZSls1o&ll=29.366571718177315,1.6344754461455668&z=5.

- Nigussie, Z.; Mesfin, T.; Sertse, T.; Tolosa Fulasa, T.; Regassa, F. Seroepidemiological study of bovine viral diarrhea (BVD) in three agroecological zones in Ethiopia. Tropical Animal Health and Production 2010, 42, 319–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orban, S.; Liess, B.; Hafez, S. M. , Frey, H. -R., Blindow, H., & Sasse-Patzer, B. Studies on transplacental transmissibility of a Bovine Virus Diarrhoea (BVD) vaccine virus1,2: I. Inoculation of pregnant cows 15 to 90 days before parturition (190th to 265th day of gestation). Zentralblatt Für Veterinärmedizin Reihe B 1983, 30, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterhans, E.; Bachofen, C.; Stalder, H.; Schweizer, M. Cytopathic bovine viral diarrhea viruses (BVDV): Emerging pestiviruses doomed to extinction. Veterinary Research 2010, 41, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridpath, J. The Contribution of Infections with Bovine Viral Diarrhea Viruses to Bovine Respiratory Disease. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 2010, 26, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saidi, R.; Bessas, A.; Bitam, I.; Ergün, Y.; Ataseven, V.S. Bovine herpesvirus-1 (BHV-1), bovine leukemia virus (BLV) and bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) infections in Algerian dromedary camels (Camelus dromaderius). Tropical Animal Health and Production 2018, 50, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.; Cho, S.; Ji, J.-M.; Cho, J.-K.; Bang, S.-Y.; Choi, Y.-J.; Kim, C.-H.; Kim, W.H. Prevalence study of bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) from cattle farms in Gyeongsangnam-do, South Korea in 2021. Korean Journal of Veterinary Service 2022, 45, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, M. (2008). An Introduction to Veterinary Epidemiology. Massey University.

- Su, N.; Wang, Q.; Liu, H.-Y.; Li, L.-M.; Tian, T.; Yin, J.-Y.; Zheng, W.; Ma, Q.-X.; Wang, T.-T.; Li, T.; Yang, T.-L.; Li, J.-M.; Diao, N.-C.; Shi, K.; Du, R. Prevalence of bovine viral diarrhea virus in cattle between 2010 and 2021: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2023, 9, 1086180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thabti, F.; Kassimi, L. B. , M’Zah, A., Romdane, S. B., Russo, P., Said, M. S. B., & Pepin, M. (2005). First detection and genetic characterization of bovine viral diarrhoea viruses (BVDV) types 1 and 2 in Tunisia. Revue Méd. Vét.

- Vilček, Š.; Herring, A. J. , Herring, J. A., Nettleton, P. F., Lowings, J. P., & Paton, D. J. Pestiviruses isolated from pigs, cattle and sheep can be allocated into at least three genogroups using polymerase chain reaction and restriction endonuclease analysis. Archives of Virology 1994, 136, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OAH (2021). BOVINE VIRAL DIARRHOEA [Chapter 3.4.7 – Terrestrial Manual]. World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH). https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/fr/Health_standards/tahm/3.04.07_BVD.pdf.

- Zeroual, F.; Leulmi, H.; Bitam, I.; Benakhla, A. Molecular evidence of Rickettsia slovaca in spleen of wild boars in northeastern Algeria. New Microbes and New Infections 2018, 24, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Song, Y.-H.; Song, J.-M.; Shi, K.; Li, J.-M.; Diao, N.-C.; Zong, Y.; Zeng, F.-L.; Du, R. The effect of fibroblast growth factor 21 on a mouse model of bovine viral diarrhea. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2023, 10, 1104779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zirra-Shallangwa, B.; González Gordon, L.; Hernandez-Castro, L. E. , Cook, E. A. J., Bronsvoort, B. M. D. C., & Kelly, R. F. The Epidemiology of Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2022, 9, 947515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).