1. Background

Menopause is a natural biological transition marking the end of a woman’s reproductive years, clinically defined as 12 consecutive months without menstruation [

1]. It is typically preceded by perimenopause, a stage characterised by hormonal fluctuations and irregular cycles, and followed by post-menopause [

2,

3]. Common symptoms include vasomotor disturbances such as hot flushes and night sweats, urogenital changes, sleep disruption, mood alterations, memory lapses, and musculoskeletal pain [

4,

5]. In Ghana, these symptoms are often under-recognised in clinical practice and rarely discussed openly, resulting in many women navigating this transition without adequate support or guidance [

6].

Ghana’s population is growing and ageing, with women constituting a significant proportion of this demographic shift. The proportion of women over 45 years is steadily increasing, reflecting both improvements in life expectancy and the wider epidemiological transition [

7]. However, these demographic changes are occurring alongside persistent socioeconomic inequalities. While Ghana has achieved lower-middle-income status, disparities remain stark between rural and urban settings, and between wealthy and resource-poor households [

8]. Many women approaching or experiencing menopause are engaged in informal labour, agriculture, and caregiving roles, often balancing economic precarity with health needs that remain largely invisible in national health planning [

9].

Women’s health services in Ghana have historically focused on maternal and child health, infectious diseases, and reproductive health, leaving conditions related to midlife and ageing under-prioritised. Healthcare access is uneven, with rural communities facing long travel distances to facilities, shortages of skilled health professionals, and limited diagnostic capacity [

10,

11]. Cost barriers, combined with out-of-pocket payment systems, further restrict access to care for chronic conditions and menopausal health concerns [

12]. As a result, many women rely on traditional remedies or informal advice networks, while biomedical services remain under-utilised or inaccessible for menopause-related symptoms [

13].

Rationale

The MARIE Ghana chapter’s work-package (WP)-2a aims to capture the lived experiences of perimenopausal, menopausal, and post-menopausal women across diverse settings. By documenting symptoms, challenges, and coping strategies, this study seeks to illuminate the intersection of biological, sociocultural, and health system factors shaping menopause. These insights will inform clinical practice and public health policies to better address the needs of midlife women in Ghana as well contribute to more equitable and culturally responsive approaches to menopausal care both within Ghana and globally.

2. Methods

This study was conducted under the Ghana chapter of the MARIE–projects WP2a. The overall WP2a was a convergent mixed-methods design. The qualitative sample comprised of eighteen participants (PID1–PID18) and were recruited from urban, peri-urban, and rural settings across Ghana through purposive sampling to capture variation in age, menopausal stage, occupation, socioeconomic background, and comorbidity status.

Ethical approval was obtained through local Ghanaian research governance committee at Narh-Bita hospital. All participants provided written informed consent prior to taking part in the study.

2.1. Data collection

Interviews were conducted using a topic guide developed specifically for the Ghanaian context, informed by existing literature and refined through consultation with local clinicians, researchers, and community representatives. The guide explored women’s experiences of menopausal symptoms, access to healthcare, work–life challenges, coping strategies, and societal perceptions of menopause. Interviews were carried out by FTK, an experienced qualitative researcher fluent in English and 3 local Ghanaian languages.

Participants were offered the choice to be interviewed in English or their preferred local language with interpretation provided when required. Some participants chose to speak in English and their preferred language as this is common practice in Ghana. All interviews were audio-recorded with participant consent and subsequently transcribed verbatim.

To ensure linguistic and conceptual accuracy, a rigorous forward–backward translation process was employed. Initial transcripts in local languages were first translated into English by bilingual researcher (NAM). A second translator (CNM) back-translated the English version into the source language. Discrepancies between the original and back-translated versions were reviewed collaboratively by the research team to resolve inconsistencies and ensure semantic equivalence, cultural sensitivity, and contextual clarity. This iterative process enhanced the trustworthiness of the data and preserved participants’ intended meanings, particularly for culturally nuanced expressions and idioms relating to menopause. Final transcripts were verified by FTK prior to coding and analysis.

2.2. Data analysis

Thematic analysis was conducted by GD and NAM followed Braun and Clarke’s six-phase framework, incorporating coding, theme development, and interpretative synthesis. To enhance rigour, transcripts were coded, with discrepancies resolved through consensus. Analysis was contextualised using the Delanerolle–Phiri framework for equity-oriented interpretation.

3. Results

The characteristics table summarises the demographic and socioeconomic profile of participants, including age, menopausal stage, education, occupation, and regional distribution.

Table 1 provides contextual insight into the diversity of the sample and allows for interpretation of findings within Ghana’s broader population landscape.

Socioeconomic status (SES) was assessed using a composite wealth index following the methodology employed by the Ghana Demographic and Health Survey (DHS). Household-level data on ownership of durable goods, housing quality, water and sanitation facilities, and access to basic services were collected. Each asset variable was coded as binary (0 = not present, 1 = present) and subjected to principal component analysis (PCA) to generate a weighted composite wealth score. Participants were ranked according to this score and stratified into five quintiles representing relative socioeconomic position within the sample.

The

lowest quintile (Q1) was defined as the

lower class, representing the most socioeconomically disadvantaged households. This group typically exhibited indicators of material deprivation, such as earthen floors, shared or unimproved sanitation, reliance on biomass fuels, and absence of key assets such as household appliances, a vehicle for travel and a home. Subsequent quintiles were categorised as lower-middle, middle, upper-middle, and upper class, with increasing access to infrastructure and durable goods. This stratification aligns with national and international standards for measuring wealth-based inequalities in Ghana and enables direct comparison with DHS and World Bank datasets (

Table 2).

By applying this approach, the classification captures relative household wealth rather than income alone, providing a robust and contextually appropriate measure of SES in settings where income data are unreliable or incomplete.

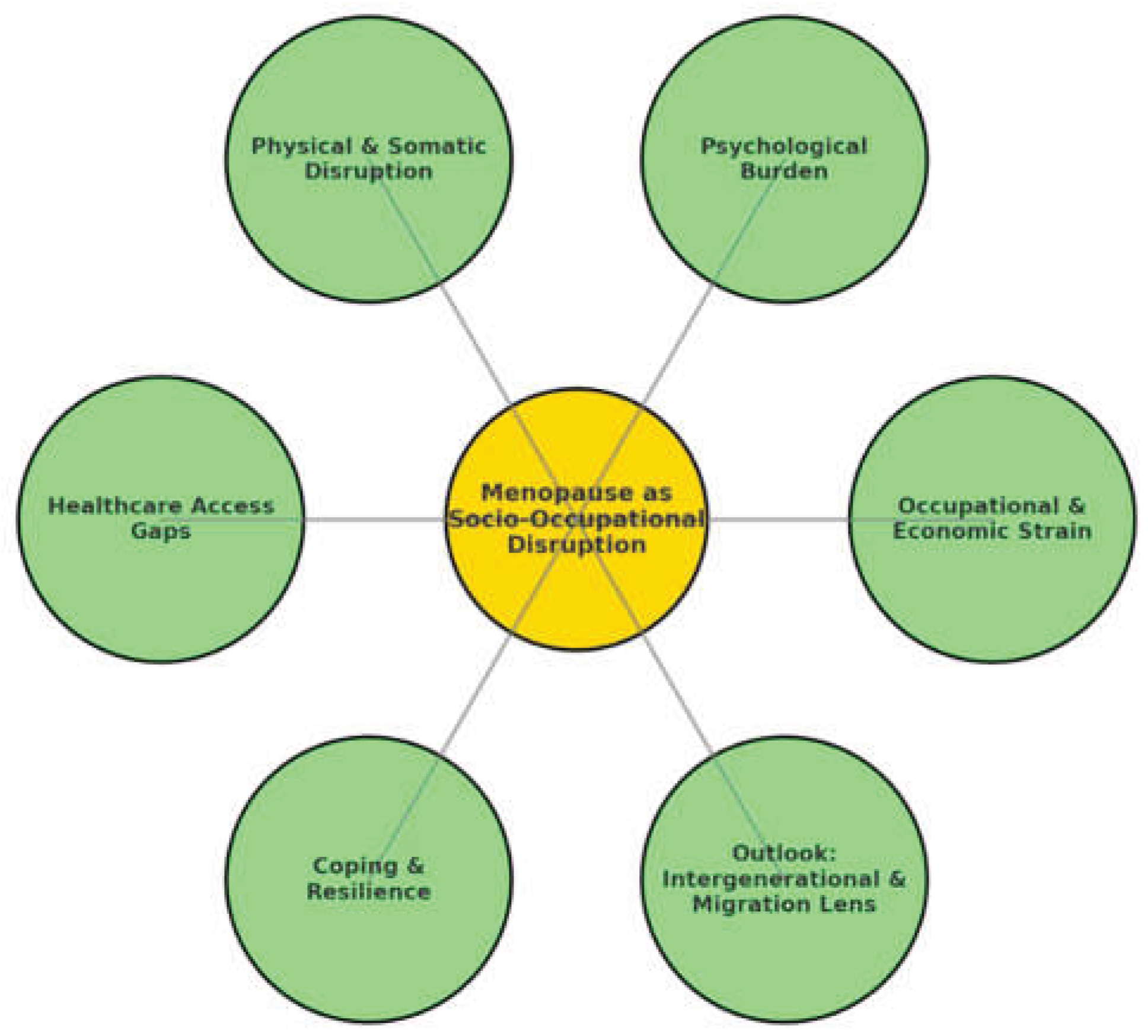

3.1. Thematic synthesis

Six key themes emerged from the analysis of women’s accounts of menopause in Ghana. Each theme is presented narratively, supported by illustrative participant quotations (italicised). A thematic map (

Figure 1) visually summarises these domains, while a detailed thematic table (

Table 3) and a colloquial-to-scientific framing matrix (

Table 4) further illustrate findings.

3.2. Occupational and economic strain

Menopause was most frequently described as disruptive to women’s ability to work, particularly in market and trading occupations, where environmental heat and prolonged hours compounded vasomotor symptoms. Women reported feeling incapacitated by hot flushes, dizziness, and fatigue that directly interfered with their livelihoods.

“I can’t sit in the market without the heat making me dizzy… people think I am lazy, but it is not laziness.” (PID3)

This disruption was not limited to market traders. Teachers, office workers, and women in informal employment reported difficulties balancing paid work with domestic responsibilities. The dual pressures of caregiving and professional expectations amplified the sense of exhaustion:

“I come home tired from teaching, but the night sweats mean I don’t sleep. Then I still have to cook and care for everyone.” (PID7)

Reduced productivity frequently translated into financial insecurity. Unlike workers in formal sectors in some high-income settings, Ghanaian women described an absence of workplace protections, flexible scheduling, or social safety nets. For those whose survival depended on daily trading, interruptions meant immediate income loss:

“If I don’t sell, there is no money. But with the pain I cannot push myself like before.” (PID9)

The occupational strain was thus both a symptom-level challenge and a broader structural inequity, with menopause intersecting with precarious livelihoods, gendered expectations, and the informal economy.

3.3. Psychological burden and emotional disruption

Psychological symptoms were described as equally, if not more, burdensome than physical ones. Women spoke of anxiety, depressive episodes, and rapid mood swings, often experienced in silence.

“Sometimes I just cry and don’t know why. My children think I am weak.” (PID11)

For some, the distress was profound enough to lead to suicidal ideation. These accounts revealed the severe mental health toll of untreated menopausal symptoms:

“The pain and the sadness together… sometimes I just wish not to wake up.” (PID14)

Such expressions underscore the scale of unmet psychological need. Yet participants frequently described these symptoms as a natural consequence of ageing, or spiritualised them within frameworks of religious and cultural interpretation. For example, low mood was often seen as the work of “dark spirits” or divine punishment, rather than a health issue requiring care.

“When I am sad too much, my mother says I should pray harder, that evil spirits are disturbing me.” (PID6)

The normalisation of emotional turmoil combined with stigma around mental health meant that most women did not seek medical help, further entrenching inequalities.

3.4. Physical and somatic disruption

Somatic symptoms formed the most visible and widely reported dimension of menopausal experience. Vasomotor symptoms such as hot flushes and night sweats were nearly universal, often described in embodied and localised language.

“My body burns and then I am cold again, it happens even in church.” (PID4)

But beyond vasomotor changes, women highlighted musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, urinary incontinence, and dizziness. These issues directly limited mobility, independence, and social participation.

“My back pain is so bad I cannot carry loads like before, so I depend on my daughter.” (PID12)

Sleep disruption was particularly burdensome, with many women describing cycles of insomnia leading to daytime exhaustion.

“I lie down but sleep does not come… by morning I am already tired.” (PID10)

These physical disruptions did not occur in isolation but cascaded into family and economic life. A woman’s inability to carry loads or work long hours meant increased reliance on children or relatives, reshaping household roles. Others spoke of embarrassment around urinary incontinence, leading to social withdrawal. These accounts demonstrate how somatic symptoms were not just biomedical phenomena but deeply social, reshaping relationships and self-worth.

3.5. Barriers to healthcare access and knowledge

Healthcare-seeking behaviour was shaped by both systemic barriers and sociocultural framing. Many women described financial exclusion as the main determinant of whether they sought care.

“Even paracetamol is expensive now. I cannot go to hospital just for sweating.” (PID8)

Those who did access healthcare often reported dismissive attitudes from providers. Symptoms were trivialised as “women’s problems” or normal ageing, leaving women without adequate explanations or treatment options.

“When I told the doctor about my heat and pains, he just laughed and said it is women’s things.” (PID5)

This dismissal created a feedback loop of mistrust, further discouraging healthcare-seeking. In addition, profound knowledge gaps were evident: many women lacked even basic information about menopause, instead interpreting their symptoms through moral or spiritual lenses.

“Nobody explained what was happening. I thought maybe it was punishment.” (PID2)

This combination of provider inattention, unaffordable services, and sociocultural misinterpretation entrenched barriers to equitable care.

3.6. Coping, resilience, and withdrawal

In the absence of accessible medical support, women described a spectrum of coping strategies. Faith and prayer were common sources of resilience, with religious belief framing menopause as a spiritual journey to be endured.

“I pray and fast; God will carry me through this time.” (PID13)

Others relied on silence or social withdrawal as a way to manage symptoms without inviting stigma.

“I keep quiet and bear it. Talking does not change anything.” (PID2)

Resilience was evident, but often framed as passive endurance rather than empowered adaptation. Some women spoke of withdrawing from community gatherings to avoid embarrassment from sweating or irritability, highlighting how coping mechanisms could simultaneously protect dignity while deepening isolation.

“I don’t go to gatherings much, I feel people will laugh at me.” (PID15)

Coping strategies thus reflected both agency and constraint, shaped by religious norms, gender expectations, and limited social support.

3.7. Outlook, migration, and intergenerational lessons

Despite the burden, many participants reflected on menopause as a predictable life stage, emphasising the importance of preparing the next generation.

“I tell my daughters this will come one day, so they should not be shocked.” (PID16)

This intergenerational framing was significant, as it suggested women sought to normalise menopause for their daughters in ways they themselves had been denied. Women positioned themselves as informal educators, filling the knowledge gap left by healthcare systems.

Migration also featured in the narratives. Some participants noted that Ghanaian women abroad faced similar struggles, but within different healthcare systems. This highlighted both continuity and divergence of experience.

“My sister in London says she suffers the same, but the doctors there don’t listen either.” (PID18)

Such accounts underscore the global relevance of Ghanaian women’s experiences, showing how gaps in menopause care transcend borders and shape diasporic lives.

3.8. Linguistic framings and cultural expressions of menopause

In addition to the symptomatic and structural disruptions outlined, the language used by women to describe their experiences provided critical cultural insight. Terms in Akan, Ga, and Ewe framed menopause as a life stage both biologically and socially recognised. For example, in Akan, perimenopause was described as “Ne bra no reyɛ kɔtɔkɔtɔ”(her menses is faltering), menopause as “W’etwa bra” (her menses has ceased), and post-menopause as “Ɔaba mu aberewa mu” (she has entered old age). Similarly, Ga women referred to perimenopause as “Enfo bla”, menopause as “Ekpa wese yam” or “Efo bla”, and post-menopause as “Efee yoomo” or “Egbɔ”. In Ewe, perimenopause was described as “Dzinu kpɔkpɔ fe ngɔ” (the beginning of menstrual cessation), menopause as “Dzinukpɔkpɔ”, and post-menopause as “Dzinukpɔkpɔ le ame fe dzinukpɔkpɔ megbe” (completion of the transition beyond menstruation).

These linguistic framings demonstrate how menopause is not only understood biologically but also situated in social time, marking shifts in identity, status, and expected roles. The Akan phrase “Ɔaba mu aberewa mu”, for instance, explicitly locates post-menopause within the cultural category of becoming an “elder woman,” carrying both dignity and, at times, marginalisation.

Alongside stage-specific terminology, women used culturally embedded expressions to describe symptoms in ways that reflected embodied experience.

Table 2 illustrates these colloquial expressions. For example, night sweating was described in Akan as

“Anadwo fifiri”, in Ewe as

“Zã me fifia fe”, and in Ga as

“Mankɛ latsa”. Hot flushes were articulated as

“Ɔhyew nketsenketse” (Akan),

“Dzoxorxor le alame” (Ewe), or

“Hetsɛmɔ Latsa” (Ga). These terms often evoke heat, burning, or flooding, showing how physiological symptoms are culturally mapped through metaphors of fire, water, and disruption.

Other phrases revealed how emotional and somatic symptoms are localised within language. Irritability was expressed in Akan as

“Ebufuw” (anger), in Ewe as

“Dzikudodo” (troubled heart), and in Ga as

“Minfumɔ bibibi” (inner restlessness). Similarly, low mood was framed in Akan as

“Awerɛhoɔ” (sadness), in Ewe as

“Nɔnɔ si bɔbɔ de anyi” (a heart heavy with grief), and in Ga as

“Ominnhyɛɛ ohe” (lack of joy). These expressions illustrate how psychological and somatic experiences of menopause are inseparable from cultural idioms of distress, shaping whether women interpret symptoms as illness, spirituality, or natural change (

Table 5).

The use of these linguistic markers demonstrates that Ghanaian women’s understanding of menopause is richly embedded in cultural, social, and spiritual frameworks. Such idioms provide explanatory models that bridge biological phenomena with lived experience. They also carry implications for clinical care: without sensitivity to these framings, biomedical explanations risk being mistranslated or dismissed.

By situating menopause within Akan, Ga, and Ewe vocabularies, participants positioned their experiences in continuity with prior generations while also acknowledging gaps in biomedical recognition. This highlights the need for culturally responsive care and educational interventions that respect and engage with local idioms, rather than displacing them. It also underscores the global significance of Ghanaian women’s voices, as these terms travel across diasporic communities, shaping how menopause is discussed and understood in high-income settings where many Ghanaians migrate.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary and implications

This study highlights menopause as an embodied, occupational, and socio-cultural disruption in Ghana. Women’s accounts illustrate the intersection of physical, psychological, and social dimensions with economic precarity and gendered expectations. Symptoms were normalised or trivialised, leaving women unsupported within both households and health systems. These findings underscore menopause as more than a biological event: it is a deeply social and inequity-laden phenomenon with significant implications for women’s livelihoods, wellbeing, and dignity.

Our findings indicate menopause significantly affects women’s ability to sustain livelihoods. Market women report dizziness and heat intolerance while teachers describe balancing professional duties with family caregiving despite chronic sleep deprivation. For traders, physical pain directly compromises productivity and income. This echoes findings from sub-Saharan Africa where menopausal symptoms are linked to occupational disruption, loss of economic agency, and reduced self-efficacy. Given Ghana’s high reliance on informal market economies, these disruptions have profound implications for both women’s independence and household income security.

Emotional struggles were a striking feature of participants’ accounts. Women described unexplained sadness, anger outbursts, and, in some cases, suicidality. The narratives reflect broader African research showing that menopause is frequently accompanied by psychological distress, stigma, and identity shifts that remain poorly addressed in health systems. Importantly, the silence surrounding mental health in Ghana exacerbates the invisibility of this burden. Addressing these needs requires psychosocial as well as biomedical interventions.

Participants reported vasomotor symptoms. Sleep disruption and fatigue were also recurrent complaints. These somatic disruptions parallel epidemiological data showing that musculoskeletal pain is prevalent among Ghanaian and West African women and is a major driver of disability. Vasomotor symptoms remain among the most common and distressing menopausal experiences globally. The interplay of pain, sleep disruption, and fatigue contributes to functional decline, affecting productivity and social engagement.

Despite distressing symptoms, participants highlighted pervasive barriers to healthcare. Women reported provider dismissal alongside financial obstacles and lack of accessible information. These findings align with research showing that over half of Ghanaian women report difficulties accessing healthcare, shaped by socioeconomic status, location, and age. Further, the availability of menopause-specific treatment options in Ghana is limited, with only a handful of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) formulations accessible compared to higher-income countries [

14]. Together, these barriers leave women largely unsupported during this critical life stage. Despite challenges, women demonstrated resilience. Faith was a central resource. Others adopted silent endurance or withdrew from social life due to fear of ridicule. Similar coping strategies have been reported among Ghanaian women facing chronic illness, where religious frameworks provide meaning and endurance but may also prevent open discussion of suffering. While faith and silence may buffer distress, they can also foster isolation and limit help-seeking.

Women’s narratives also revealed intergenerational and global perspectives. Some emphasised preparing their daughters for menopause, reflecting proactive resilience and the desire to normalize the experience for future generations. At the same time, diaspora comparisons revealed systemic neglect. This suggests that medical dismissal of menopausal concerns may be a transnational phenomenon rooted in gendered gaps in healthcare systems.

The Ghanaian context remains shaped by cultural silences around menopause. For some women, menopause symbolizes wisdom and liberation, but for others, it is a source of stigma and diminished value [

15]. Encouragingly, recent advocacy efforts such as Abla Dzifa Gomashie’s public discussion of menopause in Ghana’s parliament reflect a growing “menopause revolution” in Africa, challenging silence and calling for structural support [

16]. Recognizing menopause within Ghana’s national health priorities would ensure that women’s midlife health receives the attention afforded to maternal and reproductive health.

Some participants reflected on the experiences of Ghanaian women in the diaspora, particularly in developed countries such as the UK. While migration is often associated with better access to healthcare, women’s accounts suggest that this is not always the case. This highlights a paradox: although advanced health systems in developed countries may offer more treatment options such as hormone replacement therapy, migrant women still encounter gendered medical neglect and dismissal of menopausal concerns. Research in high-income settings similarly shows that menopause is frequently under-prioritised, with healthcare providers lacking adequate training or viewing symptoms as a “normal” stage of life not requiring intervention [

17]. Thus, while the material availability of services is greater in developed countries, the quality of support is limited by systemic gaps in awareness and sensitivity. These findings suggest that the challenges faced by Ghanaian women are not merely a product of resource scarcity but also reflect broader global patterns of medical invisibility around menopause.

4.2. Clinical implications

Clinicians in Ghana and beyond must recognise menopause as a legitimate health concern. Integrating menopause into chronic disease management, screening for psychological distress, and improving provider training to interpret colloquial idioms can reduce misdiagnosis and neglect. Routine menopause counselling in primary care, affordable pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, and multidisciplinary support including occupational and mental health are needed. For diaspora populations, clinicians in HICs should be trained to contextualise Ghanaian women’s idioms and embodied experiences within culturally competent care.

4.3. Policy and practice implications

Policy change is essential to close systemic gaps. Menopause should be incorporated into national health strategies, alongside reproductive and non-communicable disease agendas (

Table 6). Workplace protections for women in informal sectors, public health campaigns to improve literacy, and subsidised access to treatments are critical. Population science approaches must capture menopause as part of women’s life-course health, not an afterthought. For global health, addressing menopause in Ghana resonates across migration pathways, offering lessons for health systems in HICs where Ghanaian women remain underserved.

5. Conclusions

Menopause in Ghana is a neglected but profound determinant of women’s health and livelihoods. Women experience it as an embodied and occupational disruption, compounded by systemic inequities and cultural silencing. Clinical recognition, policy reform, and culturally competent global health strategies are urgently needed. Attending to menopause not only improves health equity in Ghana but strengthens global women’s health by bridging local experiences with diaspora realities.

Author contributions

GD developed the ELEMI program and the MARIE project. This was furthered by GD, NAM and FTK. FTK and NAM submitted and secured the ethics approval for the study in Ghana. FTK, ILN, KEP, CNM, PO, NO, LL, BB, CK, EB, JAA, EIA, HKG, FA, ELB, ZL and LG recruited participants to the study. GD and NAM conducted the data analysis. GD and NAM wrote the first draft and was furthered by all other authors. VP edited and formatted all versions of the manuscript. All authors critically appraised, reviewed and commented on all versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study is part of the MARIE project, funded NIHR Research Capability Fund.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflict of interest. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, the Department of Health and Social Care or the Academic institutions.

Availability of data and material

The PIs and the study sponsor may consider sharing anonymous data upon reasonable a request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from Nar-Bita-Hospital.

Consent to participate

Obtained.

Consent for publication

All authors consented to publish this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

MARIE Consortium: Aini Hanan binti Azmi, Alyani binti Mohamad Mohsin, Arinze Anthony Onwuegbuna, Artini binti Abidin, Ayyuba Rabiu, Chijioke Chimbo, Chinedu Onwuka Ndukwe, Choon-Moy Ho, Chinyere Ukamaka Onubogu, Diana Chin-Lau Suk, Divinefavour Echezona Malachy, Emmanuel Chukwubuikem Egwuatu, Eunice Yien-Mei Sim, Farhawa binti Zamri, Fatin Imtithal binti Adnan, Geok-Sim Lim, Halima Bashir Muhammad, Ifeoma Bessie Enweani-Nwokelo, Ikechukwu Innocent Mbachu, Jinn-Yinn Phang, John Yen-Sing Lee, Joseph Ifeanyichukwu Ikechebelu, Juhaida binti Jaafar, Karen Christelle, Kathryn Elliot, Kim-Yen Lee, Kingsley Chidiebere Nwaogu, Lee-Leong Wong, Lydia Ijeoma Eleje, Min-Huang Ngu, Noorhazliza binti Abdul Patah, Nor Fareshah binti Mohd Nasir, Norhazura binti Hamdan, Nnanyelugo Chima Ezeora, Nnaedozie Paul Obiegbu, Nurfauzani binti Ibrahim, Nurul Amalina Jaafar, Odigonma Zinobia Ikpeze, Obinna Kenneth Nnabuchi, Pooja Lama, Puong-Rui Lau, Rakshya Parajuli, Rakesh Swarnakar, Raphael Ugochukwu Chikezie, Rosdina Abd Kahar, Safilah Binti Dahian, Sapana Amatya, Sing-Yew Ting, Siti Nurul Aiman, Sunday Onyemaechi Oriji, Susan Chen-Ling Lo, Sylvester Onuegbunam Nweze, Damayanthi Dassanayake, Nimesha Wijayamuni, Prasanna Herath, Thamudi Sundarapperuma, Vaitheswariy Rao, Xin-Sheng Wong, Xiu-Sing Wong, Yee-Theng Lau, Heitor Cavalini, Jean Pierre Gafaranga, Emmanuel Habimana, Chigozie Geoffrey Okafor, Assumpta Chiemeka Osunkwo, Gabriel Chidera Edeh, Esther Ogechi John, Kenechukwu Ezekwesili Obi, Oludolamu Oluyemesi Adedayo, Odili Aloysius Okoye, Chukwuemeka Chukwubuikem Okoro, Ugoy Sonia Ogbonna, Chinelo Onuegbuna Okoye, Babatunde Rufus Kumuyi, Onyebuchi Lynda Ngozi, Nnenna Josephine Egbonnaji, Oluwasegun Ajala Akanni, Perpetua Kelechi Enyinna, Yusuf Alfa, Theresa Nneoma Otis, Catherine Larko Narh Menka, Kwasi Eba Polley, Isaac Lartey Narh, Bernard B. Borteih, Andy Fairclough, Kingsley Emeka Ekwuazi, Michael Nnaa Otis, Jeremy Van Vlymen, Chidiebere Agbo, Francis Chibuike Anigwe, Kingsley Chukwuebuka Agu, Chiamaka Perpetua Chidozie, Chidimma Judith Anyaeche, Clementine Kanazayire, Jean Damascene Hanyurwimfura, Nwankwo Helen Chinwe, Stella Matutina Isingizwe, Jean Marie Vianney Kabutare, Dorcas Uwimpuhwe, Melanie Maombi, Ange Kantarama, Uchechukwu Kevin Nwanna, Benedict Erhite Amalimeh, Theodomir Sebazungu, Elius Tuyisenge, Yvonne Delphine Nsaba Uwera, Emmanuel Habimana, Nasiru Sani, Amarachi Pearl Nkemdirim, Rukshini Puvanendram, Manisha Mathur, Rajeswari Kathirvel, Farah Safdar, Raksha Aiyappan, Jean Pierre Gafaranga, Bertin Ngororano, Victor Archibon, Ibe Michael Usman, Baraka Godfrey Mwahi, Filbert Francis Ilaza, Zepherine Pembe, Clement Mwabenga, Mpoki Kaminyoghe, Brenda Mdoligo, Thomas Alone Saida, Nicodemus E. Mwampashi, Olisaemeka Nnaedozie Okonkwo, Bethel Chinonso Okemeziem, Bethel Nnaemeka Uwakwe, Goodnews Ozioma Igboabuchi, Ifeoma Francisca Ndubuisi.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Narh-Bita Hospital (MARIE:An exploration of the mental and physical health impact in menopausal women) on the 27th of March 2024.

References

- Delanerolle, G.; Phiri, P.; Elneil, S.; Talaulikar, V.; Eleje, G.U.; Kareem, R.; et al. Menopause: a global health and wellbeing issue that needs urgent attention. The Lancet Global Health. 2025, 13, e196–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoro, N.; Roeca, C.; Peters, B.A.; Neal-Perry, G. The menopause transition: signs, symptoms, and management options. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2021, 106, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kalita, K.; Raina, D.; Mall, P. The Basics of Perimenopause: Menopause and Pre-Menopause. Utilizing AI Techniques for the Perimenopause to Menopause Transition: IGI Global. 2024; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hoga, L.; Rodolpho, J.; Gonçalves, B.; Quirino, B. Women's experience of menopause: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. JBI Evidence Synthesis. 2015, 13, 250–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, Y.A.; Gebeyehu, N.A.; Gelaw, K.A. The prevalence of occupational-related low back pain among working populations in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology. 2024, 19, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delanerolle, G.; Pathiraja, V.; Mudalige, T.; Dasanyake, L.; Rathnayake, N.; Sundarapperuma, T.; et al. Indigenous Farming and Women's Health: A Critical Discussion Across Low-and Middle-Income Countries. 2025.

- Wongnaah, F.G.; Osborne, A.; Duodu, P.A.; Seidu, A.-A.; Ahinkorah, B.O. Barriers to healthcare services utilisation among women in Ghana: evidence from the 2022 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Health Services Research. 2025, 25, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dery, L.G. Ghana's Health Policy: Human Resources and Health Outcomes Inequality in Northern and Southern Ghana: Keele University. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Amoako, J. Women's occupational health and safety in the informal economy: Maternal market traders in Accra, Ghana. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bawontuo, V.; Adomah-Afari, A.; Amoah, W.W.; Kuupiel, D.; Agyepong, I.A. Rural healthcare providers coping with clinical care delivery challenges: lessons from three health centres in Ghana. BMC Family Practice. 2021, 22, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nsiah, R.B.; Larbi-Debrah, P.; Avagu, R.; Yeboah, A.K.; Anum-Doku, S.; Zakaria, S.A.-R.; et al. Mapping health disparities: spatial accessibility to healthcare facilities in a rural district of Ghana using geographic information systems techniques. American Journal of Health Research. 2024, 12, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derkyi-Kwarteng, A.N.C.; Agyepong, I.A.; Enyimayew, N.; Gilson, L. A narrative synthesis review of out-of-pocket payments for health services under insurance regimes: a policy implementation gap hindering universal health coverage in sub-Saharan Africa. International journal of health policy and management. 2021, 10, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cathline, W. Perceptions, Attitudes and Management of Menopause among Menopausal Women in Three Communities, Tema: University of Ghana. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Odiari, E.A.; Chambers, A.N. Perceptions, attitudes, and self-management of natural menopausal symptoms in ghanaian women. Health Care for Women International. 2012, 33, 560–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matina, S.S.; Cohen, E.; Mokwena, K.; Mendenhall, E. Menopause and aging in sub-Saharan Africa: a narrative review. Climacteric. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbaya, S. A menopause revolution is stirring in Africa-I’m helping it to succeed. The Guardian. 2024.

- Steffan, B.; Loretto, W. Menopause, work and mid-life: Challenging the ideal worker stereotype. Gender, Work & Organization. 2025, 32, 116–131. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).