Submitted:

11 September 2025

Posted:

12 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

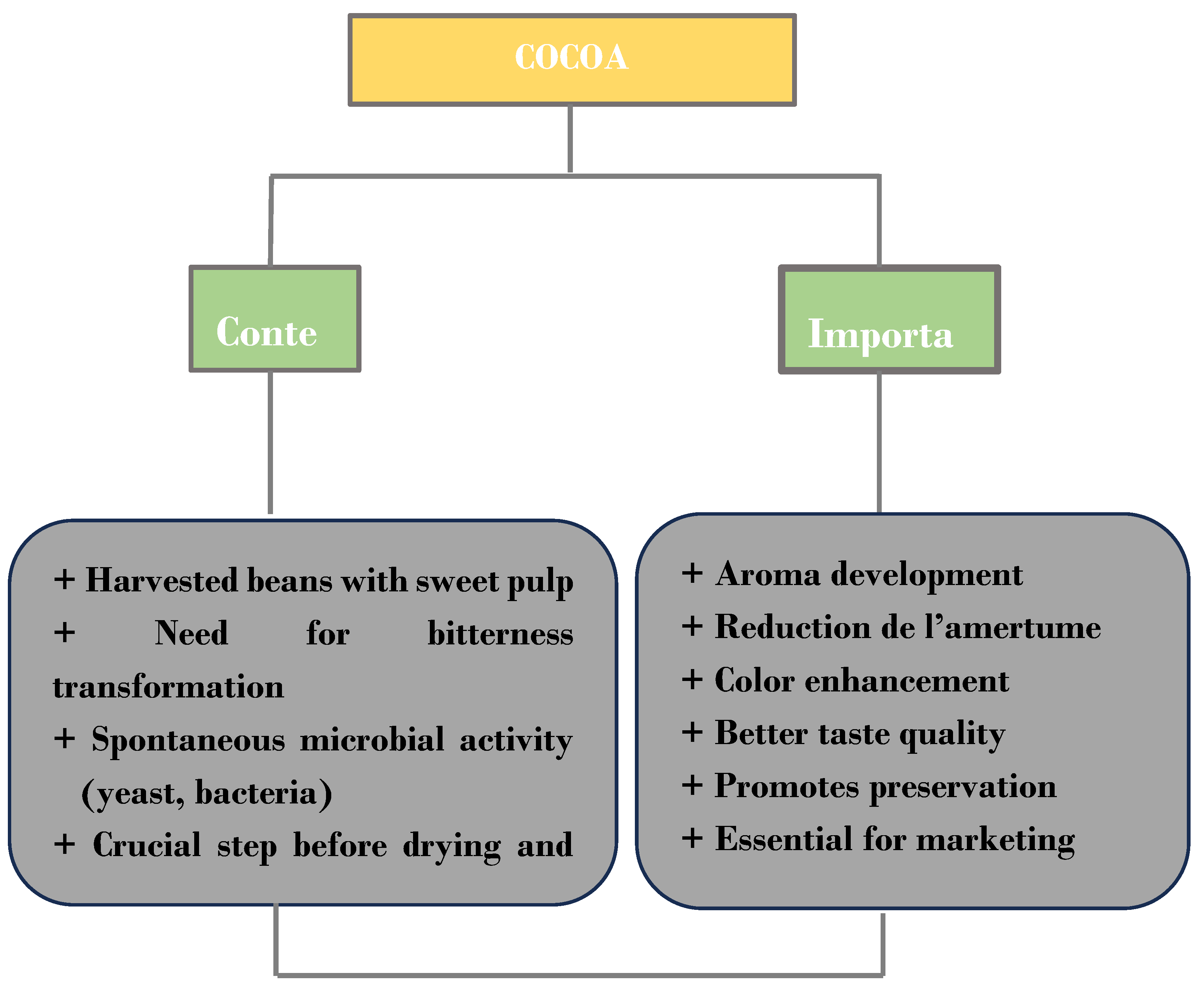

2. Background and Importance of Fermentation in Ivory Coast

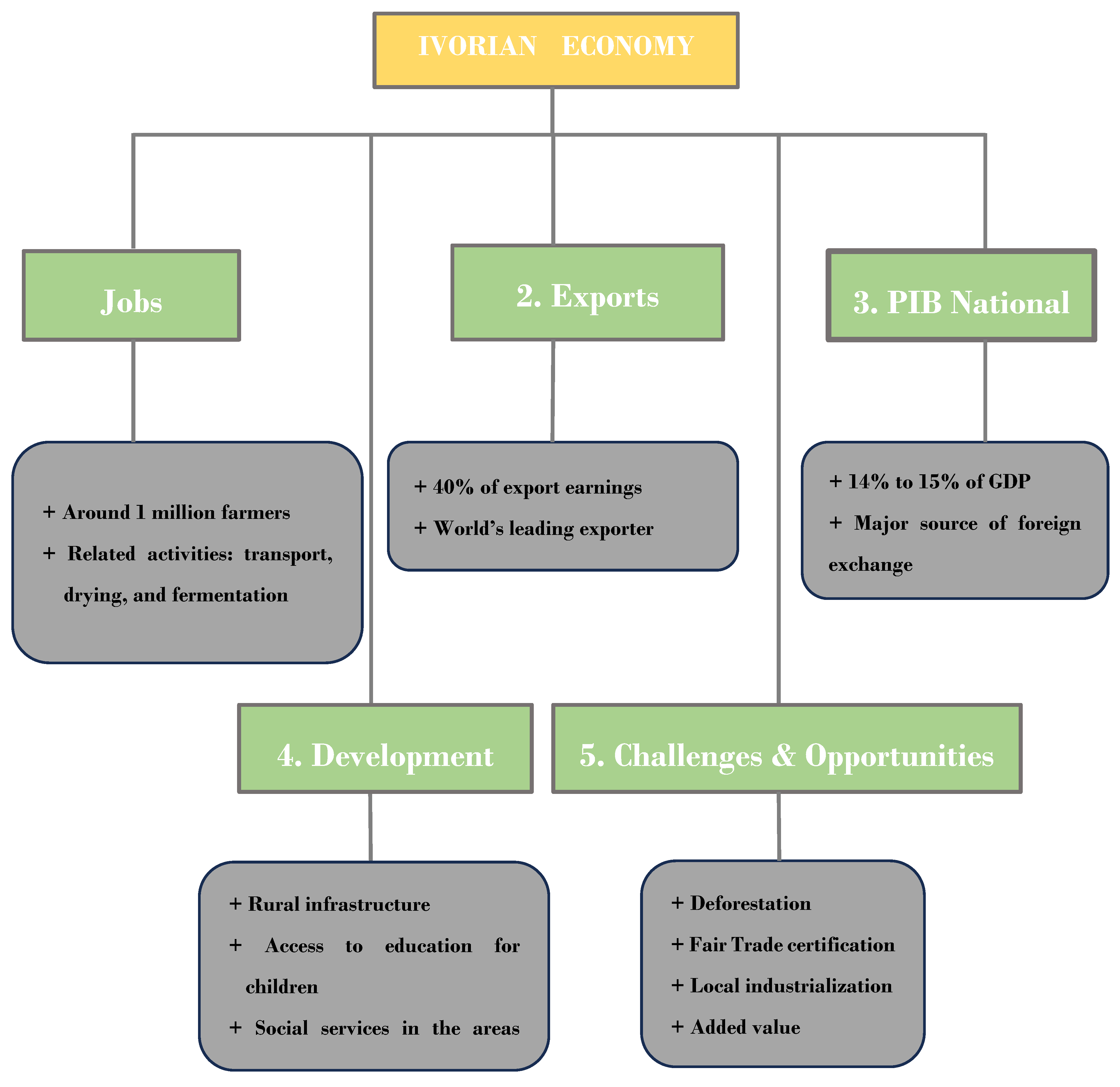

2.1. Cocoa in the Ivorian Economy

2.2. Fermentation: A Qualitative Pivot for Post-Harvest Cocoa Quality

3. The Fermentation Process of Cocoa Beans

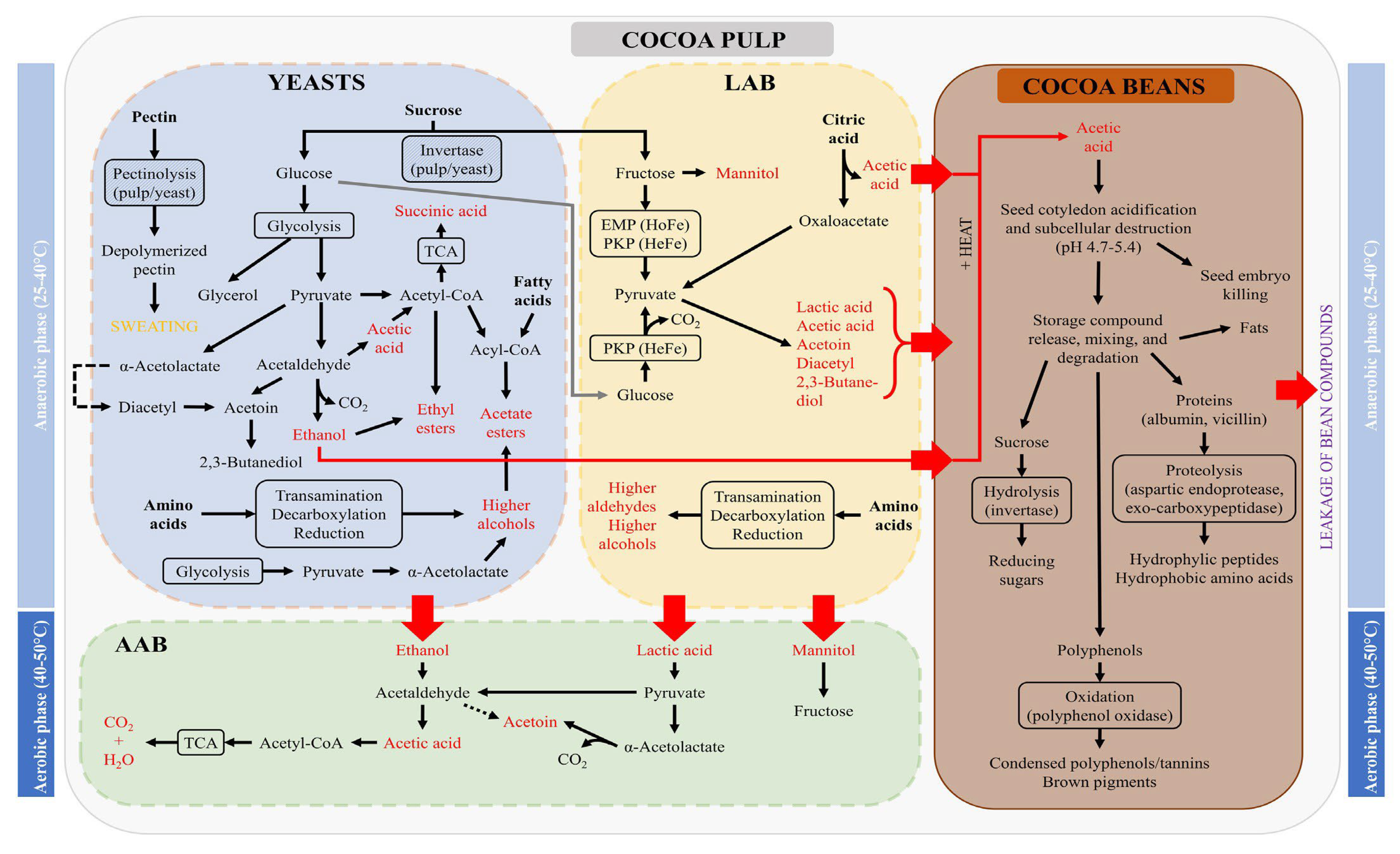

3.1. Biochemical and Microbial Process

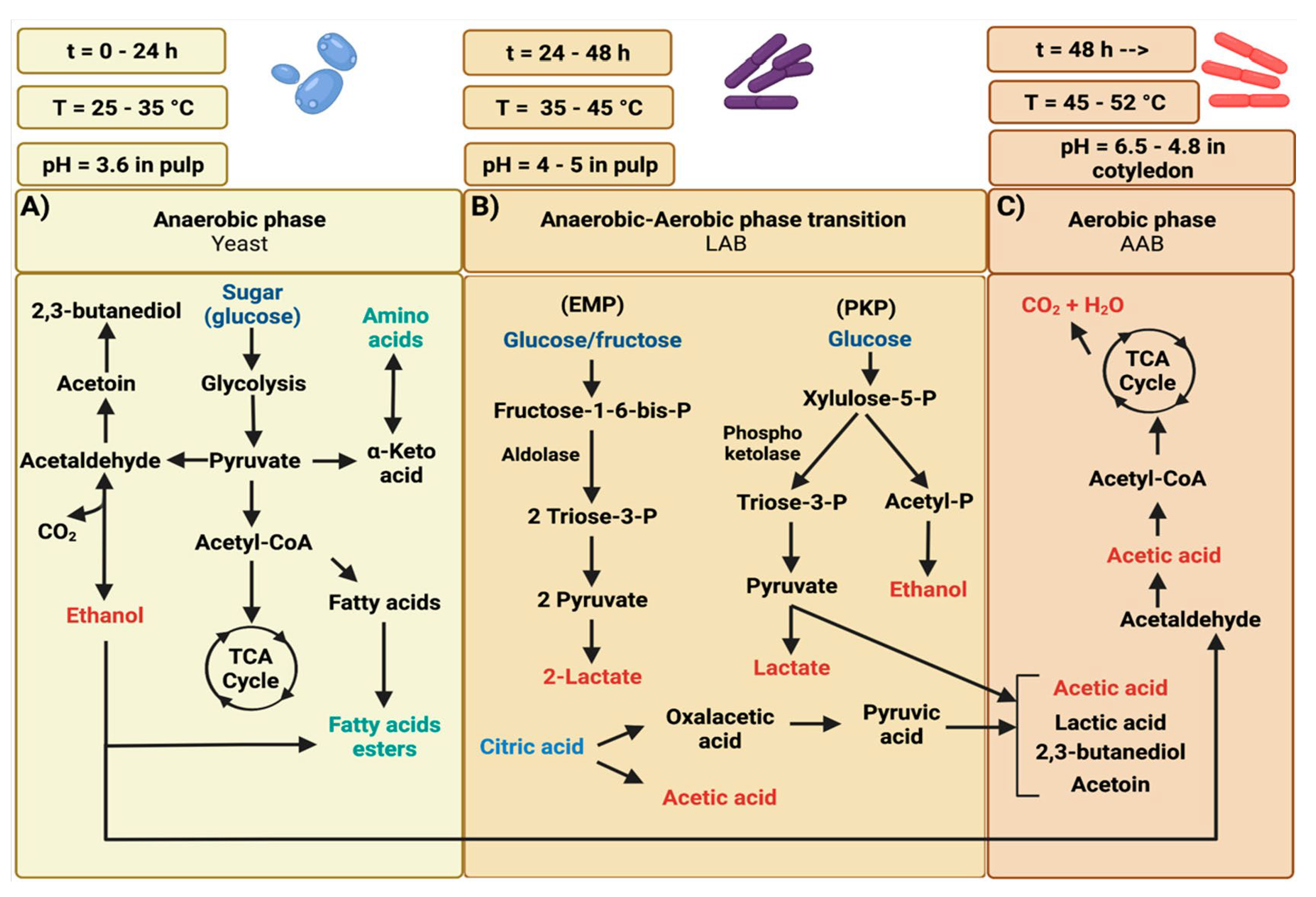

3.1.1. The Different Phases

3.1.2. Chemical Reactions and Physical Transformations

3.2. Traditional Fermentation Techniques in Ivory Coast

3.2.1. Heap Fermentation

3.2.2. Fermentation in Wooden Crates (Bins)

3.2.3. Fermentation in Pits

3.2.4. Other fermentation Techniques Using Emerging Media

3.2.5. Turning of Beans, Importance and Consequences

- -

- Importance of reversal

- -

- Consequences on bean quality

3.3. Factors Influencing Process Efficiency

3.3.1. Variety of Cocoa

3.3.2. Thickness of the Fermented Mass

3.3.3. Ambient Temperature

3.3.4. Rollover Frequency

3.3.5. Total Fermentation Time

3.3.6. Microbiota and Sanitary Conditions

3.4. Important Roles of Yeasts During Cocoa Bean Fermentation, Environment, Diversity and Aroma Production

| Yeasts | VOC | Sensory Descriptor | References |

| Aldehydes and ketones | |||

| S. cerevisiae | Acetaldehyde | Green apple | [7]1 |

| C. metapsilosis | Benzene acetaldehyde | Green | [70]1 |

| S. cerevisiae, K. marxianus, P. kudriavzevii | Phenylacetaldehyde | Floral, honey | [11,71,72]1 |

| S. cerevisiae | 2-butanal | Fruity, grassy | [7]1 |

| S. cerevisiae | 2-hexanal | Fruity, grassy | [7]1 |

|

S. cerevisiae, C. metapsilosis, Galactomyces geotrichum, P. pastoris; S. carlsbergensi, P. kudriavzevii |

Benzaldehyde | Almond, hazelnut, candy, burnt sugar | [16,70,71,73]1 |

| S. cerevisiae | Butanal, 2-methyl- | Malty, chocolate | [74,75]1 |

| S. cerevisiae, C. metapsilosis | Butanal, 3-methyl- | Malty, chocolate | [70]1 |

| S. cerevisiae | 2-Methylpropanal | malty/nutty/chocolate | [7]1 |

| S. cerevisiae, P. kudriavzevii | 2-Phenylbut-2-enal | Floral, honey, powdery, cocoa | [71]1 |

| S. cerevisiae, P. kudriavzevii | 5-Methyl-2-phenyl-2-hexenal | Cocoa | [71]1 |

| S. cerevisiae, P. kudriavzevii | Acetophenone | Floral, fruity, almond, pungent, sweet | [70,71,74]1 |

| S. cerevisiae | 2-heptanone | Floral, fruity | [7] |

| P. kudriavzevii | 2-nonanone | Fruity, sweet, waxy, green herbaceous | [71] |

| Yeasts | VOC | Sensory Descriptor | References |

| Alcohols | |||

| S. cerevisiae | Glycerol | Sweet | [70,74]1 |

| S. cerevisiae | 2,3-butanediol | Fruity, creamy, buttery | [70,74]1 |

| S. cerevisiae | 2-Propyldecan-1-ol | Floral | [70]1 |

| S. cerevisiae | Benzene ethanol | Floral | [70]1 |

| S. cerevisiae | 1-butanol–3 methyl | Fruity, malty, bitter, chocolate | [70,74]1 |

| S. cerevisiae, C. tropicalis, G. geotrichum, | 2-phenylethanol | Fruity, floral, honey, rummy | [11,19,71,73,74,76,77]1 |

| H. guilliermondii, H. uvarum, K. lactis, K. marxianus, | 2-heptanol | Fruity, floral, citrus, herbal | [11,71,72]1 |

| P. anomala, P. farinosa, P. kudriavzevii, W. anomalus, | 2-nonanol | Fat, green | [71]1 |

| Yeasts | VOC | Sensory Descriptor | References |

| Acids | |||

| S. cerevisiae | Acetic acid | Sour, vinegar | [71]1 |

| C. metapsilosis | Butanoic acid | Chessy | [70]1 |

| S. cerevisiae | 2-methylbutanoic acid | Sweaty | [7]1 |

| S. cerevisiae | 3-methylbutanoic acid | Sweaty, rancid | [70,72]1 |

| P. kudriavzevii | Octanoic acid | Sweat, fatty | [71]1 |

| Yeasts | VOC | Sensory Descriptor | References |

| Esters | |||

|

S. cerevisiae, C. tropicalis, C. utilis, H. guilliermondii, H. uvarum, K. apiculate, P. anomala, P. farinosa, P. kudriavzevii, W. anomalus, K. lactis |

Ethyl acetate | Floral | [19,73,75,78]1 |

| S. cerevisiae | Acetic acid, ethyl ester | Fruity, sweet | [70]1 |

| P. kudriavzevii | Benzyl acetate | Floral, jasmine | [71]1 |

| S. cerevisiae | Ethyl octanoate | Fruity, floral | [70]1 |

| S. cerevisiae, P. kudriavzevii | Isoamyl benzoate | Balsam, sweet | [71]1 |

| P. kudriavzevii | Ethyl dodecanoate | Sweet, floral | [71]1 |

| S. cerevisiae, C. metapsilosis | Ethylphenyl acetate | Floral | [71]1 |

| S. cerevisiae, H. guilliermondii, H. uvarum,K. marxianus, P. anomala, P. farinosa, P. kudriavzevii | 2-Phenylethyl acetate | Fruity, sweet, roses honey, floral | [71]1 |

| Yeasts | VOC | Sensory Descriptor | References |

| Others | |||

| S. cerevisiae | 2-acethyl-1-pyrrole | Caramel/chocolate/roasty | [7]1 |

| C. metapsilosis | 2-Phenylethyl formate | Floral | [70]1 |

| S. cerevisiae, P. kudriavzevii | Tetramethylpyrazine | Roasted cocoa, chocolate | [71]1 |

| S. cerevisiae | Linalool | Floral | [71]1 |

4. Issues Related to the Marketability of Ivorian Cocoa

4.1. International Quality Standards

- -

- Complete fermentation (between 5 and 7 days), essential for the development of aroma precursors and the reduction of bitterness and astringency of the beans [75];

- -

- A humidity level ≤ 7 % to avoid fungal growth and the risk of contamination by mycotoxins (in particular ochratoxin A) [76];

- -

- The absence of chemical contaminants (pesticide residues, heavy metals), biological contaminants (mosses, moulds, insect fragments) or physical contaminants (foreign bodies, defective beans) (Codex Alimentarius, 2021; ISO 2451:2021);

- -

- Good uniformity of the beans in terms of size, appearance (absence of flat, sprouted or moldy beans), and fermentation visible on the test cut ;

- -

- The traceability of the product, required by sustainability standards, which make it possible to guarantee verified origin, responsible agricultural practices and respect for social and environmental rights [77].

4.2. Constraints Encountered by Producers

- -

- Firstly, the lack of suitable equipment for the postharvest stages, in particular fermentation and drying, remains a major obstacle. In many cocoagrowing areas, producers still use rudimentary devices such as poorly designed fermentation pits or plastic sheeting on the ground for drying, which compromises the optimal development of aromas and promotes the appearance of mould or purple beans [30].

- -

- Third, the pressure of the agricultural calendar and the need to harvest quickly before rains or flight often lead to shortcuts in postharvest practices. Fermentation is sometimes shortened, or the beans are dried inappropriately, which affects the uniformity of the physicochemical quality of the finished product [83] This factor is aggravated by the absence of a strong collective organization in some areas, preventing the pooling of infrastructure and the synchronization of harvests.

4.3. Economic Impact

5. Technological Innovations and Improved Practices

5.1. Deployment of Innovative Technological Tools

5.2. Integration of Digital Technologies for Quality Control and Traceability

5.3. Strengthening Scientific Research on Fermentation Flora and Starter Cultures

6. Conclusions

- -

- Develop a national fermentation reference system, based on standardized protocols and adapted to local agroecological contexts, in order to guarantee a constant and traceable quality of the beans.

- -

- Develop and apply fermentative bio-inoculants from selected autochthonous microbial strains, to improve the efficiency and reproducibility of the fermentation process.

- -

- Promote the dissemination of appropriate technologies, including simple, durable and accessible equipment to control critical fermentation parameters (temperature, drainage, aeration).

- -

- Strengthen the capacities of local actors, by integrating continuous training on the microbiological, technological and economic aspects of fermentation.

- -

- Encourage the creation of certified premium sectors, with a differentiated valuation of well-fermented beans, likely to generate quality premiums of up to USD 300/ton.

- -

- Promote an integrated and partnership-based approach, by mobilizing researchers, cooperatives, public institutions and private sector actors to build effective governance of cocoa quality.

7. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA. | Aide acetic |

| B. | Bifidobacterium |

| C. | Candida |

| DF | Dietary fiber |

| EFSA | The European Food Safety Authority EPS Exopolysaccharide |

| EU | European Union |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization IDF Insoluble dietary fiber |

| H. | Hanseniaspora |

| K. | Kluyveromyces |

| L. | Lactobacillus, Lacticaseibacillus, Lactiplantibacillus, Limosilactobacillus, and Levilactobacillus |

| LAB | Lactic acid bacteria |

| Lac. | Lactococcus |

| Leuc. | Leuconostoc |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus MW Molecular weight |

| P. | Pichia |

| QPS | Qualified Presumption of Safety |

| QSI | Quorum sensing inhibition |

| SCFA | Short chain fatty acids |

| SDF | Soluble dietary fiber |

| Str. | Streptococcus |

| S. | Saccharomyces |

| T. | Torulaspora |

| UREM | Research and Teaching Unit in Microbiology |

| USA | United State of America |

| VOC | Volatile olfatic compounds |

| W. | Wickerhamomyces |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- J. E. Kongor, M. Hinneh, D. V. de Walle, E. O. Afoakwa, P. Boeckx, and K. Dewettinck, “Facteurs influençant la variation de la qualité du profil aromatique des fèves de cacao ( Theobroma cacao ) — Une revue,” Food Res. Int., vol. 82, pp. 44–52, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. G. Gutiérrez-Ríos et al., “Yeasts as Producers of Flavor Precursors during Cocoa Bean Fermentation and Their Relevance as Starter Cultures: A Review,” Fermentation, vol. 8, no. 7, p. 331, July 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Kouamé, G. B. Goualié, S. Soumahoro, G. H. Ouattara, and L. S. Niamké, “A highly diverse Acetic Acid Bacterial community is involved in Cocoa fermenting process in Côte d’Ivoire.” Microbiology and Nature. [CrossRef]

- J. Delgado-Ospina et al., “Functional Biodiversity of Yeasts Isolated from Colombian Fermented and Dry Cocoa Beans,” Microorganisms, vol. 8, no. 7, p. 1086, July 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. Sun et al., “A smart nanofibre sensor based on anthocyanin/poly-l-lactic acid for mutton freshness monitoring,” Int. J. Food Sci. Technol., vol. 56, no. 1, pp. 342–351, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. S. Agyirifo et al., “Metagenomics analysis of cocoa bean fermentation microbiome identifying species diversity and putative functional capabilities,” Heliyon, vol. 5, no. 7, July 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. De Vuyst and F. Leroy, “Functional role of yeasts, lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria in cocoa fermentation processes,” FEMS Microbiol. Rev., vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 432–453, July 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. S. Nielsen, S. Hønholt, K. Tano-Debrah, and L. Jespersen, “Yeast populations associated with Ghanaian cocoa fermentations analysed using denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE),” Yeast, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 271–284, 2005. [CrossRef]

- H.-M. Daniel, G. Vrancken, J. F. Takrama, N. Camu, P. De Vos, and L. De Vuyst, “Yeast diversity of Ghanaian cocoa bean heap fermentations,” FEMS Yeast Res., vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 774–783, Aug. 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Gänzle, “Lactic metabolism revisited: metabolism of lactic acid bacteria in food fermentations and food spoilage,” Curr. Opin. Food Sci., vol. 2, pp. 106–117, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Mota-Gutierrez, I. Ferrocino, M. Giordano, M. L. Suarez-Quiroz, O. Gonzalez-Ríos, and L. Cocolin, “Influence of Taxonomic and Functional Content of Microbial Communities on the Quality of Fermented Cocoa Pulp-Bean Mass,” Appl. Environ. Microbiol., vol. 87, no. 14, pp. e00425-21, June 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Díaz-Muñoz et al., “Curing of Cocoa Beans: Fine-Scale Monitoring of the Starter Cultures Applied and Metabolomics of the Fermentation and Drying Steps,” Front. Microbiol., vol. 11, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. von Wright, “bactéries lactiques: Une introduction,” in bactéries lactiques.

- Y. Wang et al., “Metabolism Characteristics of Lactic Acid Bacteria and the Expanding Applications in Food Industry,” Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol., vol. 9, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Azlan et al., “Antioxidant activity, nutritional and physicochemical characteristics, and toxicity of minimally refined brown sugar and other sugars,” Food Sci. Nutr., vol. 8, no. 9, pp. 5048–5062, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Mathara, U. Schillinger, P. M. Kutima, S. K. Mbugua, and W. H. Holzapfel, “Isolement, identification et caractérisation des micro-organismes dominants du kule naoto : le lait fermenté traditionnel maasaï au Kenya,” Int. J. Food Microbiol., vol. 94, no. 3, pp. 269–278, Aug. 2004. [CrossRef]

- L. J. R. Lima, M. H. Almeida, M. J. R. Nout, and M. H. Zwietering, “Theobroma cacao L., ‘The Food of the Gods’: Quality Determinants of Commercial Cocoa Beans, with Particular Reference to the Impact of Fermentation,” Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr., vol. 51, no. 8, pp. 731–761, Sept. 2011. [CrossRef]

- T. Lefeber, M. Janssens, N. Camu, and L. De Vuyst, “Kinetic Analysis of Strains of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Acetic Acid Bacteria in Cocoa Pulp Simulation Media toward Development of a Starter Culture for Cocoa Bean Fermentation,” Appl. Environ. Microbiol., vol. 76, no. 23, pp. 7708–7716, Dec. 2010. [CrossRef]

- R. F. Schwan and A. E. Wheals, “The Microbiology of Cocoa Fermentation and its Role in Chocolate Quality,” Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr., vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 205–221, July 2004. [CrossRef]

- D. S. Nielsen, O. D. Teniola, L. Ban-Koffi, M. Owusu, T. S. Andersson, and W. H. Holzapfel, “The microbiology of Ghanaian cocoa fermentations analysed using culture-dependent and culture-independent methods,” Int. J. Food Microbiol., vol. 114, no. 2, pp. 168–186, Mar. 2007. [CrossRef]

- N. Camu et al., “Influence of Turning and Environmental Contamination on the Dynamics of Populations of Lactic Acid and Acetic Acid Bacteria Involved in Spontaneous Cocoa Bean Heap Fermentation in Ghana,” Appl. Environ. Microbiol., vol. 74, no. 1, pp. 86–98, Jan. 2008. [CrossRef]

- A. Kouadio, É. Pepey, C. Boussou, S. Brou, L. Fertin, and S. Pouil, “Leviers de substitution à l’usage de pesticides dans les systèmes cacaopiscicoles intégrés en Côte d’Ivoire,” Cah. Agric., vol. 33, p. 30, 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. Arévalo-Gardini et al., “Cacao agroforestry management systems effects on soil fungi diversity in the Peruvian Amazon,” Ecol. Indic., vol. 115, p. 106404, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Koné et al., “Contribution of predominant yeasts to the occurrence of aroma compounds during cocoa bean fermentation,” Food Res. Int., vol. 89, pp. 910–917, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. A. L. Kouadio, A. T. M. Kouakou, G. G. Zanh, P. Jagoret, J.-F. Bastin, and Y. S. S. Barima, “Floristic structure, potential carbon stocks, and dynamics in cocoa-based agroforestry systems in Côte d’Ivoire (West Africa),” Agrofor. Syst., vol. 99, no. 1, p. 12, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J.-L. Kouassi, A. Kouassi, Y. Bene, D. Konan, E. J. Tondoh, and C. Kouame, “Exploring Barriers to Agroforestry Adoption by Cocoa Farmers in South-Western Côte d’Ivoire,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 23, p. 13075, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Kouakou, “Effets des politiques sectorielles d’innovations sur les interactions systémiques pour une transition technologique dans l’agriculture et l’alimentation : Cas des filières agri-alimentaires de la Banane plantain et du Porc en Côte d’Ivoire,” phdthesis, Montpellier SupAgro ; Institut National Polytechnique Félix Houphouët-Boigny (Yamoussoukro, Côte d’Ivoire), 2019. Accessed: Sept. 04, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://theses.hal.science/tel-04095477.

- K. G. N’Guessan, “Le cacao, les défis nationaux d’une filière stratégique dans la lutte contre la pauvreté en Afrique de l’Ouest,” pp. 1–474, 2024, Accessed: Sept. 04, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.torrossa.com/it/resources/an/5904469.

- B. Losch, “La libéralisation de la filière cacaoyère ivoirienne et les recompositions du marché mondial du cacao : vers la fin des ‘pays producteurs’ et du marché international ?,” OCL Ol. Corps Gras Lipides, 2001. [CrossRef]

- J.-L. Kouassi, L. Diby, D. Konan, A. Kouassi, Y. Bene, and C. Kouamé, “Drivers of cocoa agroforestry adoption by smallholder farmers around the Taï National Park in southwestern Côte d’Ivoire,” Sci. Rep., vol. 13, no. 1, p. 14309, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Asante et al., “The cocoa yield gap in Ghana: A quantification and an analysis of factors that could narrow the gap,” Agric. Syst., vol. 201, p. 103473, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Läderach et al., “The importance of food systems in a climate crisis for peace and security in the Sahel,” Int. Rev. Red Cross, vol. 103, no. 918, pp. 995–1028, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. F. Schwan and A. E. Wheals, “The Microbiology of Cocoa Fermentation and its Role in Chocolate Quality,” Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr., July 2004. [CrossRef]

- V. T. T. Ho, J. Zhao, and G. Fleet, “Yeasts are essential for cocoa bean fermentation,” Int. J. Food Microbiol., vol. 174, pp. 72–87, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. Illeghems, L. De Vuyst, and S. Weckx, “Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of Acetobacter pasteurianus 386B, a strain well-adapted to the cocoa bean fermentation ecosystem,” BMC Genomics, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 526, Aug. 2013. [CrossRef]

- H. G. Gutiérrez-Ríos et al., “Yeasts as Producers of Flavor Precursors during Cocoa Bean Fermentation and Their Relevance as Starter Cultures: A Review,” Fermentation, vol. 8, no. 7, p. 331, July 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Torres-Moreno, E. Torrescasana, J. Salas-Salvadó, and C. Blanch, “Nutritional composition and fatty acids profile in cocoa beans and chocolates with different geographical origin and processing conditions,” Food Chem., vol. 166, pp. 125–132, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Ardhana and G. H. Fleet, “The microbial ecology of cocoa bean fermentations in Indonesia,” Int. J. Food Microbiol., vol. 86, no. 1, pp. 87–99, Sept. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Z. Papalexandratou et al., “Species Diversity, Community Dynamics, and Metabolite Kinetics of the Microbiota Associated with Traditional Ecuadorian Spontaneous Cocoa Bean Fermentations,” Appl. Environ. Microbiol., vol. 77, no. 21, pp. 7698–7714, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Koné et al., “Pod storage time and spontaneous fermentation treatments and their impact on the generation of cocoa flavour precursor compounds,” Int. J. Food Sci. Technol., vol. 56, no. 5, pp. 2516–2529, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Koné, O. Nâ€TMNan-Alla, K. M. Kouassi, and K. E. Koffi, “Use of mineral salts to remove recalcitrance to somatic embryogenesis of improved genotypes of cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.),” Afr. J. Biotechnol., vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 33–42, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Konan et al., “Impact of New Fermentation Supports on the Quality of Cocoa Beans (Theobroma cacao L.) From Côte d’Ivoire,” J. Food Qual., vol. 2025, no. 1, p. 2118517, 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. Illeghems, L. D. Vuyst, Z. Papalexandratou, and S. Weckx, “Phylogenetic Analysis of a Spontaneous Cocoa Bean Fermentation Metagenome Reveals New Insights into Its Bacterial and Fungal Community Diversity,” PLOS ONE, vol. 7, no. 5, p. e38040, May 2012. [CrossRef]

- H. Ho and S. Bunyavanich, “Role of the Microbiome in Food Allergy,” Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep., vol. 18, no. 4, p. 27, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Ho, A. Baryshnikova, and G. W. Brown, “Unification of Protein Abundance Datasets Yields a Quantitative Saccharomyces cerevisiae Proteome,” Cell Syst., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 192-205.e3, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Meersman et al., “Detailed Analysis of the Microbial Population in Malaysian Spontaneous Cocoa Pulp Fermentations Reveals a Core and Variable Microbiota,” PLOS ONE, vol. 8, no. 12, p. e81559, Dec. 2013. [CrossRef]

- T. Garcia-Armisen et al., “Diversity of the total bacterial community associated with Ghanaian and Brazilian cocoa bean fermentation samples as revealed by a 16 S rRNA gene clone library,” Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., vol. 87, no. 6, pp. 2281–2292, Aug. 2010. [CrossRef]

- [Z. Papalexandratou and L. De Vuyst, “Assessment of the yeast species composition of cocoa bean fermentations in different cocoa-producing regions using denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis,” FEMS Yeast Res., vol. 11, no. 7, pp. 564–574, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. De Vuyst and S. Weckx, “The cocoa bean fermentation process: from ecosystem analysis to starter culture development,” J. Appl. Microbiol., vol. 121, no. 1, pp. 5–17, July 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. P. Oliveira, “AMAZÔNICOS: IDENTIFICAÇÃO DE GENES ASSOCIADOS,” 2025.

- K. Choque-Quispe et al., “Impact of Altitudinal Gradients on Exportable Performance, and Physical and Cup Quality of Coffee (Coffea arabica L.) Grown in Inter-Andean Valley,” Resources, vol. 14, no. 9, p. 136, Sept. 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. O. Afoakwa, G. O. Sampson, D. Nyirenda, C. N. Mwansa, L. Brimer, and L. Chiwona-Karltun, “Physico-Functional and Starch Pasting Properties of Cassava (Manihot Esculenta Cruntz) Flours as Influenced by Processing Technique and Varietal Variations,” Asian J. Agric. Food Sci., vol. 9, no. 2, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Ardhana and G. H. Fleet, “The microbial ecology of cocoa bean fermentations in Indonesia,” Int. J. Food Microbiol., vol. 86, no. 1, pp. 87–99, Sept. 2003. [CrossRef]

- M. Crafack et al., “Influencer la saveur du cacao en utilisant Pichia kluyveri et Kluyveromyces marxianus dans une culture de démarrage mixte définie pour la fermentation du cacao,” Int. J. Food Microbiol., vol. 167, no. 1, pp. 103–116, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. O. Arévalo-Hernández et al., “Growth and Nutritional Responses of Juvenile Wild and Domesticated Cacao Genotypes to Soil Acidity,” Agronomy, vol. 12, no. 12, p. 3124, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- O. Koffi, L. Samagaci, B. Goualie, and S. Niamke, “SCREENING OF POTENTIAL YEAST STARTERS WITH HIGH ETHANOL PRODUCTION FOR A SMALL-SCALE COCOA FERMENTATION IN IVORY COAST,” Food Environ. Saf. J., vol. 17, no. 2, July 2018, Accessed: Sept. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://fens.usv.ro/index.php/FENS/article/view/572.

- [L. Y. Ouattara et al., “Use of Cocoa Pods Husks (Theobroma cacao L.) as a Potential Substrate for the Production of Lactic Acid by Submerged Fermentation Using Lactobacillus Fermentum ATCC 9338,” Waste Biomass Valorization, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- [K. K. Ahossi, C. Ibourahema, K. K. Athanase, F. F. Stéphane, C. Mendjara, and K. Ibrahim, “Investigation des nouveaux supports de fermentation des fèves de cacao dans les principales régions de production de cacao (Haut-Sassandra, Nawa et Bas-Sassandra) en Côte d’Ivoire,” Int. J. Innov. Appl. Stud., vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 857–865, 2023.

- A. Batista-Gonzalez, R. Vidal, A. Criollo, and L. J. Carreño, “New Insights on the Role of Lipid Metabolism in the Metabolic Reprogramming of Macrophages,” Front. Immunol., vol. 10, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- [E. O. Afoakwa, J. E. Kongor, J. Takrama, and A. S. Budu, “Changes in nib acidification and biochemical composition during fermentation of pulp pre-conditioned cocoa (Theobroma cacao) beans,” 2013, Accessed: Aug. 28, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://csirspace.foodresearchgh.org/handle/1/1338.

- A. Beckett and A. Nayak, “The reflexive consumer,” Mark. Theory, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 299–317, Sept. 2008. [CrossRef]

- A. Kumari et al., “Soil microbes: a natural solution for mitigating the impact of climate change,” Environ. Monit. Assess., vol. 195, no. 12, p. 1436, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Bondzie-Quaye, M. S. Swallah, A. Acheampong, S. M. Elsherbiny, E. O. Acheampong, and Q. Huang, “Advances in the biosynthesis, diversification, and hyperproduction of ganoderic acids in Ganoderma lucidum,” Mycol. Prog., vol. 22, no. 4, p. 31, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. O. Afoakwa, R. Adjonu, and J. Asomaning, “Viscoelastic properties and pasting characteristics of fermented maize: influence of the addition of malted cereals,” Int. J. Food Sci. Technol., vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 380–386, Feb. 2010. [CrossRef]

- H.-M. Daniel, G. Vrancken, J. F. Takrama, N. Camu, P. De Vos, and L. De Vuyst, “Yeast diversity of Ghanaian cocoa bean heap fermentations”, Accessed: Sept. 01, 2025. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- D. S. Nielsen, S. Hønholt, K. Tano-Debrah, and L. Jespersen, “Yeast populations associated with Ghanaian cocoa fermentations analysed using denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE),” Yeast, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 271–284, 2005. [CrossRef]

- X. Xia, S. Zhao, A. Smith, J. McEvoy, J. Meng, and A. A. Bhagwat, “Caractérisation des isolats de Salmonella provenant d’aliments vendus au détail sur la base du sérotypage, de l’électrophorèse sur gel en champ pulsé, de la résistance aux antibiotiques et d’autres propriétés phénotypiques,” Int. J. Food Microbiol., vol. 129, no. 1, pp. 93–98, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Z. Papalexandratou, G. Vrancken, K. De Bruyne, P. Vandamme, and L. De Vuyst, “Spontaneous organic cocoa bean box fermentations in Brazil are characterized by a restricted species diversity of lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria,” Food Microbiol., vol. 28, no. 7, pp. 1326–1338, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- O.-A. R. H, L.-V. E. F, U.-V. J. C, and C.-J. C. F, “Microorganisms during cocoa fermentation: systematic review,” Foods Raw Mater., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 155–162, 2020, Accessed: Sept. 01, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/microorganisms-during-cocoa-fermentation-systematic-review.

- J. Tigrero-Vaca et al., “Microbial Diversity and Contribution to the Formation of Volatile Compounds during Fine-Flavor Cacao Bean Fermentation,” Foods, vol. 11, no. 7, p. 915, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. C. A. Chagas Junior, N. R. Ferreira, E. H. de A. Andrade, L. D. do Nascimento, F. C. de Siqueira, and A. S. Lopes, “Profile of Volatile Compounds of On-Farm Fermented and Dried Cocoa Beans Inoculated with Saccharomyces cerevisiae KY794742 and Pichia kudriavzevii KY794725,” Molecules, vol. 26, no. 2, p. 344, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. De Vuyst and F. Leroy, “Functional role of yeasts, lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria in cocoa fermentation processes,” FEMS Microbiol. Rev., vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 432–453, July 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Koné et al., “Contribution of predominant yeasts to the occurrence of aroma compounds during cocoa bean fermentation,” Food Res. Int., vol. 89, pp. 910–917, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. De Vuyst and F. Leroy, “Functional role of yeasts, lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria in cocoa fermentation processes,” FEMS Microbiol. Rev., vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 432–453, July 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Mota-Gutierrez, L. Barbosa-Pereira, I. Ferrocino, and L. Cocolin, “Traceability of Functional Volatile Compounds Generated on Inoculated Cocoa Fermentation and Its Potential Health Benefits,” Nutrients, vol. 11, no. 4, p. 884, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. Kim, B.-R. Cho, and J.-S. Hahn, “Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the production of 2-phenylethanol via Ehrlich pathway,” Biotechnol. Bioeng., vol. 111, no. 1, pp. 115–124, 2014. [CrossRef]

- N. Moreira, F. Mendes, T. Hogg, and I. Vasconcelos, “Alcohols, esters and heavy sulphur compounds production by pure and mixed cultures of apiculate wine yeasts,” Int. J. Food Microbiol., vol. 103, no. 3, pp. 285–294, Sept. 2005. [CrossRef]

- V. Rojas, J. V. Gil, F. Piñaga, and P. Manzanares, “Études sur la production d’esters d’acétate par des levures œnologiques non Saccharomyces,” Int. J. Food Microbiol., vol. 70, no. 3, pp. 283–289, Nov. 2001. [CrossRef]

- S. Llano et al., “Exploring the Impact of Fermentation Time and Climate on Quality of Cocoa Bean-Derived Chocolate: Sensorial Profile and Volatilome Analysis,” Foods, vol. 13, no. 16, p. 2614, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. P. on B. Hazards (BIOHAZ) et al., “Update of the list of QPS-recommended biological agents intentionally added to food or feed as notified to EFSA 15: suitability of taxonomic units notified to EFSA until September 2021,” EFSA J., vol. 20, no. 1, p. e07045, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Mekouar, “Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO),” Yearb. Int. Environ. Law, vol. 34, no. 1, p. yvae031, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Wessel and M. C. Anderson, “Neural mechanisms of domain-general inhibitory control,” Trends Cogn. Sci., vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 124–143, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. Ackah and E. Dompey, “Effects of fermentation and drying durations on the quality of cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) beans during the rainy season in the Juaboso District of the Western-North Region, Ghana,” Bull. Natl. Res. Cent., vol. 45, no. 1, p. 175, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. L. Yao, F. G. Messoum, and K. Tano, “Contamination des fèves de cacao par les hydrocarbures aromatiques polycycliques (HAP) en Côte d’Ivoire,” Rev. Marocaine Sci. Agron. Vét., vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 319–322, Sept. 2022, Accessed: Sept. 01, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.agrimaroc.org/index.php/Actes_IAVH2/article/view/1174.

- P. Läderach et al., “The importance of food systems in a climate crisis for peace and security in the Sahel,” Int. Rev. Red Cross, vol. 103, no. 918, pp. 995–1028, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. O. Afoakwa, G. O. Sampson, D. Nyirenda, C. N. Mwansa, L. Brimer, and L. Chiwona-Karltun, “Physico-Functional and Starch Pasting Properties of Cassava (Manihot Esculenta Cruntz) Flours as Influenced by Processing Technique and Varietal Variations,” Asian J. Agric. Food Sci., vol. 9, no. 2, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. De Icco et al., “Does MIDAS reduction at 3 months predict the outcome of erenumab treatment? A real-world, open-label trial,” J. Headache Pain, vol. 23, no. 1, p. 123, Sept. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Cadby and T. Araki, “Towards ethical chocolate: multicriterial identifiers, pricing structures, and the role of the specialty cacao industry in sustainable development,” SN Bus. Econ., vol. 1, no. 3, p. 44, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Jouvin, “Strategic misreporting along the value chain : the case of certified cocoa in Côte d’Ivoire,” These de doctorat, Bordeaux, 2024. Accessed: Sept. 04, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://theses.fr/2024BORD0201.

- F. and A. O. of the U. Nations, FAO publications catalogue 2022: April. Food & Agriculture Org., 2022.

- W. H. Organization, Levels and trends in child malnutrition child malnutrition: UNICEF / WHO / World Bank Group Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates: Key findings of the 2023 edition. World Health Organization, 2023.

- A. Kamilaris, I. R. Cole, and F. X. Prenafeta-Boldú, “Chapter 7 - Blockchain in agriculture,” in Food Technology Disruptions, C. M. Galanakis, Ed., Academic Press, 2021, pp. 247–284. [CrossRef]

- P. P. Churi, S. Joshi, M. Elhoseny, and A. Omrane, Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: A Practical Approach. CRC Press, 2022.

- S. Misra, P. Pandey, and H. N. Mishra, “Novel approaches for co-encapsulation of probiotic bacteria with bioactive compounds, their health benefits and functional food product development: A review,” Trends Food Sci. Technol., vol. 109, pp. 340–351, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. N. Nyangena et al., “Effects of Traditional Processing Techniques on the Nutritional and Microbiological Quality of Four Edible Insect Species Used for Food and Feed in East Africa,” Foods, vol. 9, no. 5, p. 574, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. R. C. Konfo, F. M. C. Djouhou, M. H. Hounhouigan, E. Dahouenon-Ahoussi, F. Avlessi, and C. K. D. Sohounhloue, “Recent advances in the use of digital technologies in agri-food processing: A short review,” Appl. Food Res., vol. 3, no. 2, p. 100329, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Sam, “Lessons from Working with the Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA): The Case of the Ghana-Question and Answer Service (Ghana-QAS),” Knowl. Manag. Dev. J., vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 78–98, Aug. 2021, Accessed: Sept. 01, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://km4djournal.org/index.php/km4dj/article/view/494.

- The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023. FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO;, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. van der Linden, “Misinformation: susceptibility, spread, and interventions to immunize the public,” Nat. Med., vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 460–467, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. A. A. Kouassi, H. A. Andrianisa, S. K. Sossou, M. B. Traoré, and R. M. Nguematio, “Sustainability of facilities built under the Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) implementation: Moving from basic to safe facilities on the sanitation ladder,” PLOS ONE, vol. 18, no. 11, p. e0293395, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Traoré and S. Asongu, “The diffusion of green technology, governance and CO2 emissions in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J., vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 463–484, Sept. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Boeck, “Antibiotic tolerance: targeting bacterial survival,” Curr. Opin. Microbiol., vol. 74, p. 102328, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Belmin et al., “Conception d’un idéotype de territoire agroécologique pour le département de Fatick, Sénégal. Rapport d’atelier d’idéotypage Dakar, Sénégal 2-6 septembre 2024,” Sept. 2024, Accessed: Sept. 01, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/168907.

- É. Michaud, “International Organization for Standardization (ISO). (2023). Plain language - Part 1 : Governing principles and guidelines. Norme ISO 24495-1:2023,” Discourse WritingRédactologie, vol. 35, pp. 35–37, 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang et al., “OPT: Open Pre-trained Transformer Language Models,” June 21, 2022, arXiv: arXiv:2205.01068. [CrossRef]

- K. Agyekum et al., “If Others Are, Why not Ghana? A Case for Industrial Hemp Application in the Ghanaian Construction Industry,” in Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure Development in Africa’s Changing Climate, E. Adinyira, C. Amoako, T. E. Kwofie, C. Aigbavboa, K. Agyekum, and M. Addy, Eds., Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024, pp. 23–39. [CrossRef]

- O. J. Ajor, A. Akintola, and J. T. Okpa, “United nations development programme (undp) and poverty alleviation in cross river state north senatorial district, nigeria,” Glob. J. Soc. Sci., vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 49–61, Aug. 2023, Accessed: Sept. 05, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/gjss/article/view/253384.

- [ E. P. on B. Hazards (BIOHAZ) et al., “Update of the list of QPS-recommended biological agents intentionally added to food or feed as notified to EFSA 15: suitability of taxonomic units notified to EFSA until September 2021,” EFSA J., vol. 20, no. 1, p. e07045, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. K. Asare, O. Domfeh, S. W. Avicor, P. Pobee, Y. Bukari, and -Attah I. Amoako, “Colletotrichum gloeosporioides s.l. causes an outbreak of anthracnose of cacao in Ghana,” South Afr. J. Plant Soil, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 107–115, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. J. End, A. J. Daymond, and P. Hadley, Directrices técnicas para el movimiento seguro del germoplasma de cacao. Versión revisada de las Directrices técnicas de FAO/IPGRI No. 20 (Quinta actualización, 2024). Bioversity, 2024. Accessed: Sept. 01, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/173210.

- T. Lefeber, Z. Papalexandratou, W. Gobert, N. Camu, and L. De Vuyst, “On-farm implementation of a starter culture for improved cocoa bean fermentation and its influence on the flavour of chocolates produced thereof,” Food Microbiol., vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 379–392, June 2012. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).