1. Introduction

Lentivirus (LV), γ-retrovirus, and adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are the most used viral vectors in various applications. [

1,

2,

3] Those viral vectors have superior transduction efficiency. γ-retroviral vectors were the first viral vectors used for CD19-targeted CAR-T production, accounting for approximately one-fifth of clinical trials involving gene delivery. [

2] AAVs have a relatively lower risk of toxicity; however, their limited package size (~50 kb) restricts their gene delivery capability. [

3] Lentiviral vectors (LVVs) are the most versatile viral vectors for the expression of CAR. [

1] Besides their high gene transfer efficiency, they can transduce both non-dividing and dividing cells. Moreover, since the viral genome is passed to daughter cells, it can exert long-term transgene expression.[

1] It has been reported that ≈94% of evaluable CAR-T products are prepared by viral vectors, with >50% mediated by LVVs. [

4]

CAR-T cells are genetically modified T cells that express synthetic receptors on the cell surface to detect and eradicate cancer cells by identifying specific tumor antigens. Unlike T cells, CAR-T cells can recognize antigens on the surface of cancer cells without human major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules. [

5] Therefore, CAR-T cells can distinguish a wider range of targets than natural T cells. When CAR-T cells bind to the targeted antigen, they are activated and function as “active drugs” that target and attack the tumor [

2]. After the initial approval of the US Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) of the first two CAR-T therapies, Kymriah

TM (

tisagenlecleucel) for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL),[

6,

7,

8] and Yescarta

TM (

axicabtagene ciloleucel) to treat acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) respectively in 2017,[

9,

10] Terakus

TM (

brexucabtagene autoleucel) was approved for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) in 2020,[

11,

12] followed by the approval of Abecma

® (

idecabtagene vicleucel) to treat adult patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (MM) after four or more prior lines of therapy, [

13,

14] and Breyanzi

® (

lisocabtagene maraleucel) to treat adult patients with large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) both in 2021.[

15,

16] Lately, FDA-approved Carvykti

TM (

ciltacabtagene autoleucel) was also released for relapses and refractory MM in February 2022. [

17,

18] Finally, the Chinese National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) approved Fucaso

®(

equecabtagene autoleucel) in 2023 [

19] and Carteyva

® (

relmacabtagene autoleucel) in 2024.[

20] As shown in

Table 1, most of the eight CAR-T therapies approved by the US and Chinese regulatory agencies utilize LVV as the gene delivery strategy, highlighting their widespread use. [

21,

22]

The CAR-T therapies, first described in the late 20th century, have emerged as promising treatments for multiple cancers. [

1,

2,

3] The CAR structure is the primary functional element of CAR-Ts, comprising four distinct domains: the ligand-binding domain, spacer element, transmembrane domain, and cytoplasmic domain.[

4] Once the ligand-binding domain recognizes and binds to the antigen on the surface of the cancer cell, the signal is transmitted downstream, and the CAR-Ts are activated and stimulated to proliferate, release cytokines, and alter their metabolism. Furthermore, granzyme and perforin are released to destroy and digest cancer cells. [

7]

In recent years, CAR technology has emerged and developed rapidly. CAR-T immunotherapy has shown impressive clinical success for refractory and relapsed (r/r) hematopoietic malignancies, including CD19+ leukemia and lymphoma and BCMA+ multiple myeloma. Several CAR-T products have been commercially approved worldwide for treating the above blood tumors. Motivated by the achievements made, researchers have expanded CAR technology from CAR-T to CAR-NK, CAR-CIK, and CAR-MΦ applications, and have employed CAR-engineered cell therapy for broader indications to treat aggressive diseases. [

3,

22,

42]

In Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, the Abu Dhabi Stem Cells Center (ADSCC) GMP laboratory has been producing and applying autologous clinical-grade CAR-T cells for the treatment of hematological malignancies since 2024, utilizing the CliniMacs Prodigy® platform (Miltenyi Biotec). The cells were stimulated and transduced with a lentiviral vector (Lentigen Technology), provided by Miltenyi Biotec, encoding a CAR protein targeting CD19. [

43] Miltenyi CliniMACs Prodigy

® is one of the newest technologies for CAR-T cell expansion. This system is currently utilized for stem cell enrichment and the preparation of virus-reactive T cells. [

44] It is a technology system that combines a cell washer, a magnetic cell separation system, and a cell culture device in a closed, sterilized system. [

45] Equipped with a flexible programming suite, the CliniMACs Prodigy technology enables us to fully integrate and automate the complex, multi-step CAR T cell processing and manufacturing procedures within the GMP lab.

In this review article, we referred to the biological principles of LVVs, a brief description of the CAR-Ts manufacturing platform using LVVs, the regulatory framework for biosafety and biosecurity in LVVs production facilities, and finally, the frontier development of lentiviral transduction techniques that may improve their efficiency and function to meet the growing demand for clinical application.

2. Basic Biology of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 (HIV-1) LVVs.

2.1. What Are LVVs?

The

Retroviridae viral family is the origin of LVVs. These vectors can be derived from various viral sources, including feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV), simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), which is the most used. [

46,

47] Within the

Retroviridae family, LV is a genus of enveloped RNA viruses. These viruses have a spherical structure with an outer envelope, a matrix protein, a capsid, and a core that contains two identical RNA strands and an enzyme. LV, including AIDS-causing HIV, induces chronic and often fatal diseases in humans and other mammals. They are globally distributed and infect hosts like apes, cows, goats, horses, cats, and sheep. Known for their ability to integrate viral DNA into host genomes, they are highly efficient for gene delivery and can be inherited by the host’s descendants. The virion’s morphology reveals enveloped viruses, 80-100 nm in diameter, that are spherical or pleomorphic, with capsid cores that mature into a cylindrical or conical shape. The virus’s surface appears rough because the envelope projections, or tiny spikes (approximately 8 nm), are dispersed evenly over the surface. [

48] The virus is engineered to transfer up to 10 kb of genes to the host cell, resulting in the expression of encoded proteins. [

14]

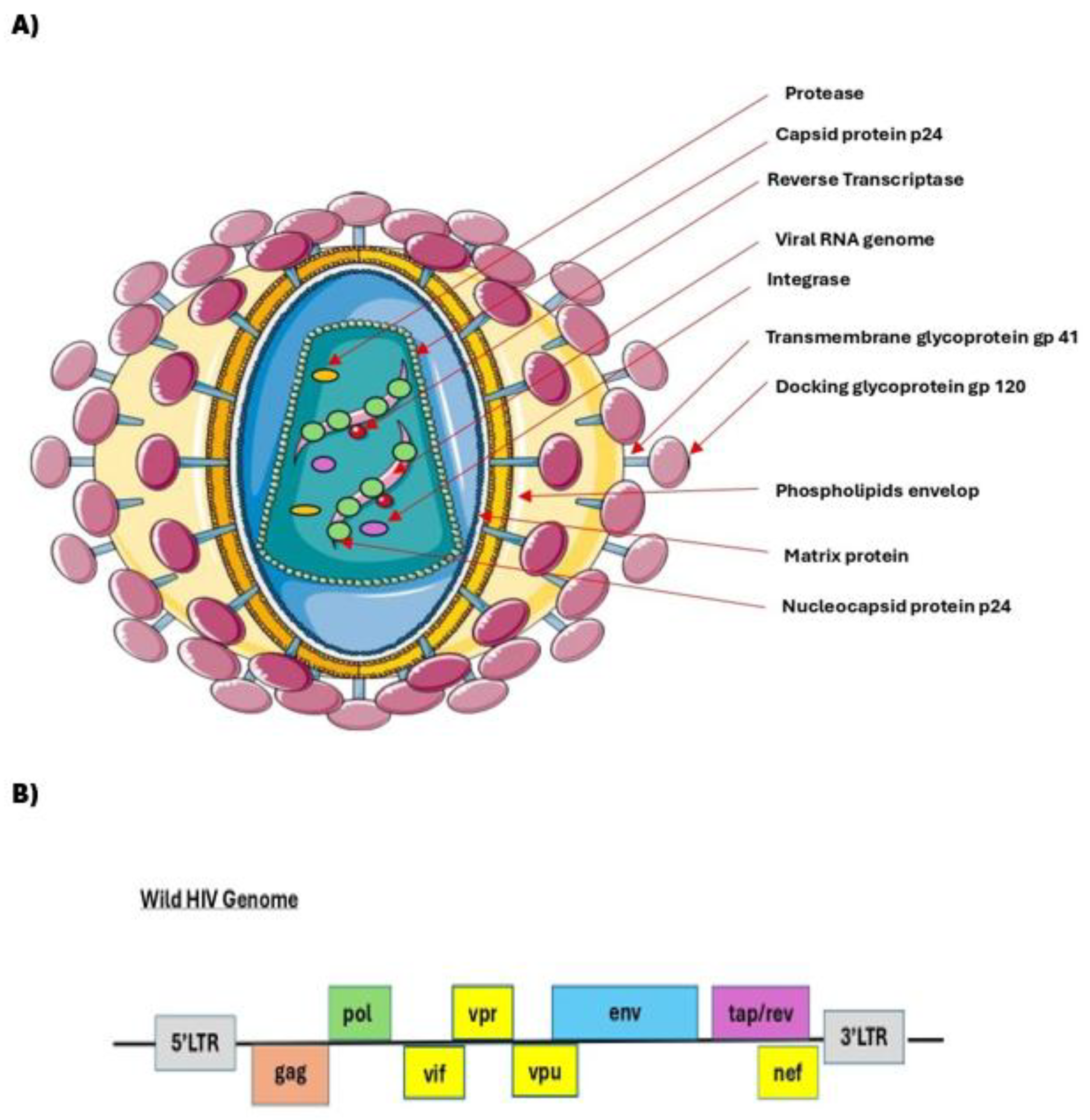

Figure 1 illustrates a wild HIV-1 morphology (

A) a genomic structure (

B).

A summary of the key genetic elements, their encoded proteins, and functional roles in the HIV-1 lentiviral vector system, as well as the design of modern self-inactivating (SIN) transfer vectors, along with the separation of functions across multiple plasmids for enhanced biosafety, is illustrated in

Table 2 below.

2.2. What Are the LV Structure, Capacities, and Functions in Biotechnology?

As a type of simple retrovirus, HIV-1-derived LV are capable of hijacking host-mediated machinery to sustain efficient nuclear import across the intact nuclear membrane. [

49] This feature has allowed them to efficiently transduce nondividing and terminally differentiated cells (e.g., postmitotic neurons, hepatocytes, or macrophages) with superb efficiency.[

50] The long-lasting effect of the viral transduction supports long-term production of the therapeutic gene-of-interest (thus providing permanent steady-state “dosing” after a single administration of the virus), which is essential for gene therapy applications. The LV genome comprises ~10.7 kb of single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) enclosed within a lipid-enriched spherical capsid measuring ~100 nm in diameter. The viral genome encodes both structural and enzymatic genes, including gag and pol. The polycistronic gag gene encodes three products, namely matrix (MA), capsid (CA), and nucleoproteins (NC). The polycistronic pol gene encodes three viral enzymes: reverse transcriptase (RT), protease (PR), and integrase (IN). HIV-derived LV is an enveloped virus that uses a glycoprotein envelope to attach and enter the host cell.

Nevertheless, the creation of heterologous envelopes used for viral particle pseudo-typing was one of the main progresses in the field, allowing for the dramatic diversification and extension of transduction tropism. The host range of retroviral vectors including LVV can be expanded or altered by a process known as pseudotyping. Pseudotyped LVV consist of vector particles bearing glycoproteins (GPs) derived from other enveloped viruses. Such particles possess the tropism of the virus from which the GP was derived. For example, to exploit the natural neural tropism of rabies virus, vectors designed to target the central nervous system have been pseudotyped using rabies virus derived GPs. Among the first and still most widely used GPs for pseudotyping LVV is the vesicular stomatitis virus GP (VSV-G), due to the very broad tropism and stability of the resulting pseudotypes. Pseudotypes involving VSV-G have become effectively the standard for evaluating the efficiency of other pseudotypes. Additionally, supplementing viral particles with heterologous envelopes has positively impacted vector safety. [

50,

51] As mentioned above, LVs can be efficiently pseudotyped with a broad range of heterologous envelopes, thereby enabling broad viral tropism. For example, LV supplemented with Mokola virus (MV), Ross River virus (RRV), and Rabies virus (RV) demonstrated a strong preference for the transduction into neuronal cells.[

51] However, the most common envelope used to pseudotype viral particles is that of vesicular stomatitis virus protein G (VSV-G). The envelope has been shown to support an extremely broad range of tropism, and as such, it is used for transduction into most cells and tissues. [

50]

In addition to gag and pol, LV carry six supplementary genes: rev and tat, which are involved in viral transcription and export, respectively, and nef, vif, vpr, and vpu, which are involved in viral entry, assembly, replication, particle formation, and release. [

52] Moreover, Tat and Rev are crucial in regulation. Vif, Vpr, Vpu, and Nef are four additional accessory genes unique to HIV-1 that support virus replication and increase pathogenicity in vivo. The 3’ terminus of the viral genome also has two untranslated regions, 5’ R-U5 and U3-R. [

16] The viral RNA functioned as a template for the reverse transcription of viral cDNA after the virus entered the host cells. The U3-U5 sequence is duplicated on both ends of the RNA, resulting in LTRs on the viral DNA. This DNA integrates into the host DNA, becoming a provirus. LVVs are essential for delivering genes because, unlike other

Retroviridae, they can infect nondividing cells. Following replication, the provirus spreads to daughter cells. Finally, transcription of the integrated DNA occurs, and the progeny viral genomes are then delivered to the cytoplasm. The virus forms a mature infectious virion by budding from the plasma membrane, simultaneously acquiring its lipid envelope.[

18]

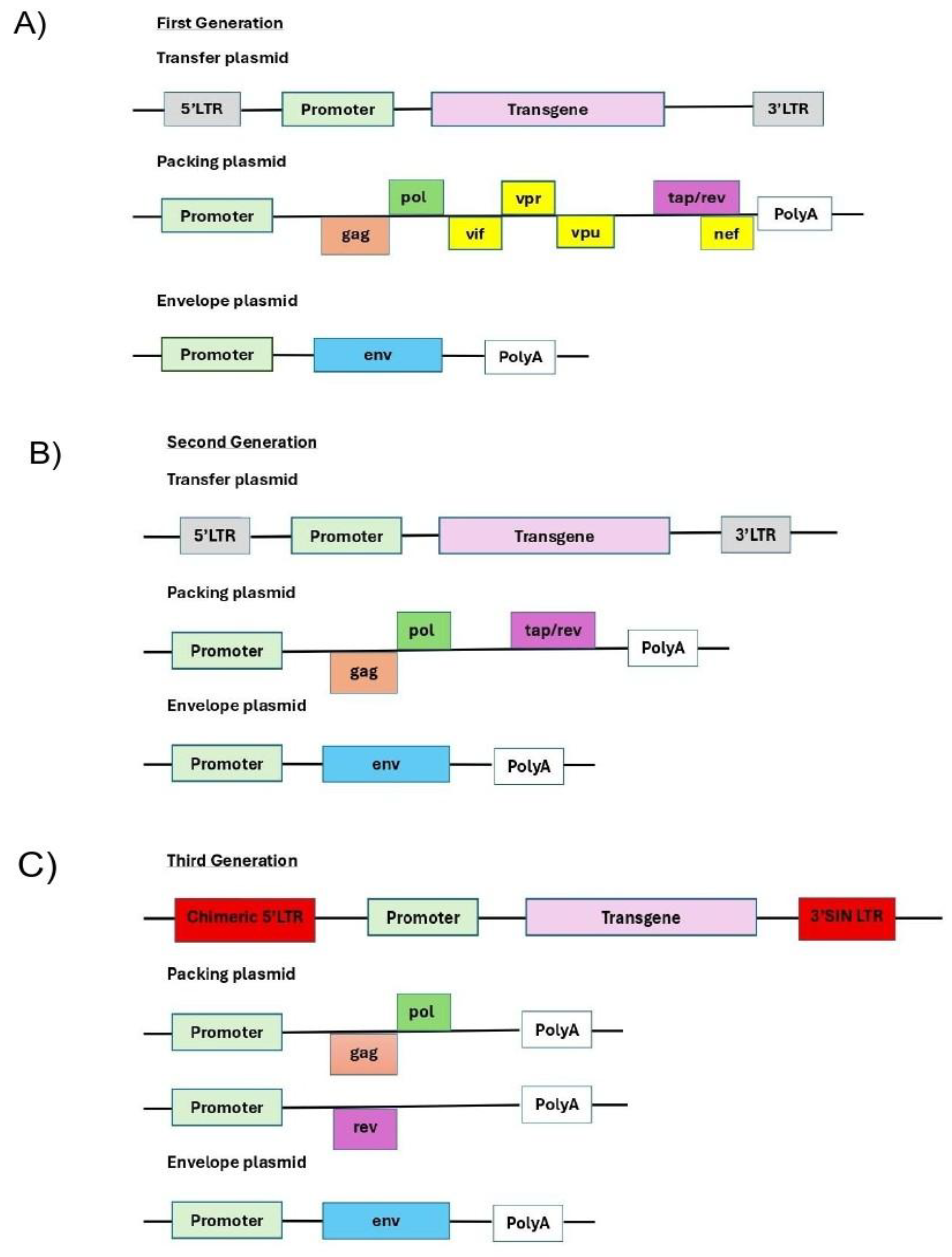

To date, there have been four generations of the LVV system derived from HIV; they are summarized in

Figure 2. The core principle behind this generational classification is the progressive removal of accessory genes and the splitting of the remaining essential genes across multiple plasmids. This minimizes sequence overlap, making it increasingly improbable for a replication-competent lentivirus (RCL) to form through recombination. It is essential to note that the latter four accessory products are dispensable for vector production and can therefore be omitted from the packaging cassette of the vector (

Figure 2A). The removal of these products has been shown to have a positive effect on the vector safety; importantly, their deletion also creates space for cloning larger inserts. [

53,

54,

55,

56] The first generation was released between 1996–1997 with 3 plasmids prove in-vivo, long-term expression: transfer + packaging (carrying many HIV genes) + envelope (often VSV-G). These papers established stable integration and expression in non-dividing cells and set the basic plasmid split [

53]. Indeed, the second generation of the packaging system carried only the tat and rev genes (

Figure 2B). [

57] In 1998, the Self-inactivating (SIN) LTRs: 3′LTR ΔU3 copied to 5′LTR after reverse transcription provided LTRs transcriptionally inactive in the provirus; a major safety leap, and in the same year a third generation conditional packaging was created by rev moved to its own plasmid, tat no longer required when the transfer uses a heterologous promoter; overall system becomes 4 plasmids (transfer SIN + gag/pol + rev + env). This split greatly reduces RCL risk and becomes today’s clinical workhorse. [

55]. The third generation of the packaging system lacks the tat gene, which is coincidental with the deletion of the endogenous promoter harbouring the tat-responsive element, TAR, at the U30 region of the LTRs (

Figure 2C). Instead, full-length RNA of the virus is transcribed from the strong ubiquitous promoter derived from Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) or cytomegalovirus (CMV). It is a still the gold standard system for clinical applications. Further improvement in virus safety has been achieved with the development of the fourth-generation packaging plasmid, highlighted by the separation of the gag/pol and rev sequences into two distinct cassettes. The fourth generation of the packaging systems is the safest to date but still in experimental [

55].

-

(A)

The first generation is composed by three plasmids: Transfer + Packaging + Envelope. Full HIV-1 genome minus env in packaging; accessory genes present (vif, vpr, vpu, nef). Tat-dependent LTR; non-SIN; high homology to wild-type..

-

(B)

The second generation is composed also by three plasmids:Transfer + gag/pol + tat + rev(packaging) + Envelope. The difference from the first is that accessory genesare deleted (Δvif, Δvpr, Δvpu, Δnef); often still non-SIN; tat + rev retained in packaging.

- (C)

The third generation is composed by four plasmids: Transfer (SIN) + gag/pol + rev + Envelope. At a difference from previous generations rev is moved to a separate plasmid; SIN LTRs (ΔU3) standard; heterologous 5′ promoter; cPPT/CTS and WPRE commonly used. [

12]

It should be noted that the REV gene is present in all packaging systems, as its product, REV, plays a key role in exporting fully length and partially spliced viral RNA (vRNA) from the nucleus into the cytoplasm. [

58] The advanced generations of the packaging plasmids also harbor a strong, heterologous poly-adenylation signal (poly-A), derived from the SV40 virus or bovine/human growth hormone (bGH/hGH). These potent poly-As enable high-level vRNA stability, and as such, their inclusion is advantageous for packaging and viral titers. [

55,

58] Moreover, the inclusion in the third generation of the woodchuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element (WPRE) and the central polypurine tract (cPPT) in the viral transfer cassette has been shown to improve further vRNA stability, transcription efficiency, and overall viral titer. [

59,

60] Importantly, the above modifications significantly reduce the likelihood of recombination-competent retroviruses (RCR) appearing, which positively impacts viral safety characteristics.

Table 3 summarizes the comparison between the 4 generations of LVV and their key genomic features, plasmid system, safety profile, and primary use.

2.3. The Comparison Between Viral Vectors

LVs have the unique ability to stably integrate into the genomes of dividing, nondividing, and post-mitotic mammalian cells, a capability that ɣ-retroviruses do not possess to the same extent. While adenoviruses can also transduce nondividing cells, they cannot integrate stably into the host genome and require significantly more time for design and preparation. Additionally, LVs are far less immunogenic than ɣ-retroviruses and adenoviruses, making them more suitable for various cell types and animal models.

In

Table 4 the comparison highlights the differences between LVs, ɣ-retroviruses, and adenoviruses regarding genome integration ability, target cell types, immunogenicity, design and preparation time, application range, vector capacity, and stability.[

1]

Table 4.

Comparison between lentivirus, ɣ retrovirus, and adenovirus vectors.[

1].

Table 4.

Comparison between lentivirus, ɣ retrovirus, and adenovirus vectors.[

1].

| Characteristic |

Lentivirus (LV) |

ɣ Retrovirus |

Adenovirus (AAVs) |

| Genome Integration Ability |

Stable integration into the host genome |

Less stable integration compared to LV |

Cannot integrate into the host genome |

| Cell Type Target |

Dividing, non-dividing, and post-mitotic cells |

Primarily dividing cells |

Dividing and non-dividing cells |

| Immunogenicity |

Low |

Moderate |

High |

| Design and Preparation Time |

Short |

Moderate |

Long |

| Application Range |

Broad, suitable for various cell types and animal models |

Limited, mainly used in dividing cells |

Generally used for short-term gene expression or vaccine development |

| Vector Capacity |

Relatively small |

Relatively small |

Large |

| Stability |

High |

Moderate |

High |

2.4. LVs’ Summary of Advantages: [48]

-

o

High-efficiency gene delivery: LVs can efficiently deliver exogenous genes into target cells, including those that are difficult to transfect, such as primary and stem cells.

-

o

Long-term gene expression: Once integrated into the host genome, LVs can achieve long-term, stable gene expression, a crucial aspect for treating chronic diseases.

-

o

Broad host range: LVs can infect various cell types, including dividing and nondividing cells, expanding their range of applications.

-

o

Low immunogenicity: Modified LVVs typically have low immunogenicity, reducing the risk of host immune responses.

-

o

Safety: Modern LVVs have been genetically engineered to remove pathogenic genes, enhancing their safety.

2.5. Other Applications of LVs

LV packaging can also be crucial in the development of gene and cell therapies. [

8] Based on the characteristics of the LV system, it may be used in the following applications:

-

o

Basic research: In molecular and cell biology, LLVs are utilized for gene overexpression, gene knockout, and knock-in experiments. Gene knockout involves inactivating a gene by replacing it with an artificial piece of DNA. In contrast, knock-in experiments involve the insertion of a gene into a specific location in the genome. These techniques aid in the study of gene functions and disease mechanisms. Large-scale collaborative efforts are underway to use LVs to block the expression of specific genes using RNA interference technology in high-throughput formats. Conversely, LVVs are also employed to stably over-express certain genes, thus allowing researchers to examine the effects of increased gene expression in a model system. For example, gene editing technologies mediated by LV, such as CRISPR/Cas9, can repair or replace mutated genes.[

12]

-

o

Stable cell line construction: LV can be used to make stable cell lines in the same manner as standard retroviruses. The process involves infecting host cells with recombinant LLVs or pseudo-typed LVVs that carry selectable markers, such as the puromycin resistance gene. This gene confers antibiotic resistance to the infected host cells. When these antibiotics are added to the growth medium of the host cells, they kill any cells that have not incorporated the LV genome. [

1]Those surviving cells can be expanded to create stable cell lines that include the lentiviral genome and harbor the genetic information encoded by it.[

1] For instance, in vaccine development, LLVs can be vaccine carriers to express pathogen antigens, thereby inducing an immune response.[

61] It is used in the development of HIV vaccines and other vaccines for infectious diseases. [

14,

16,

62]

3. Manufacturing CAR T Cells Ex Vivo

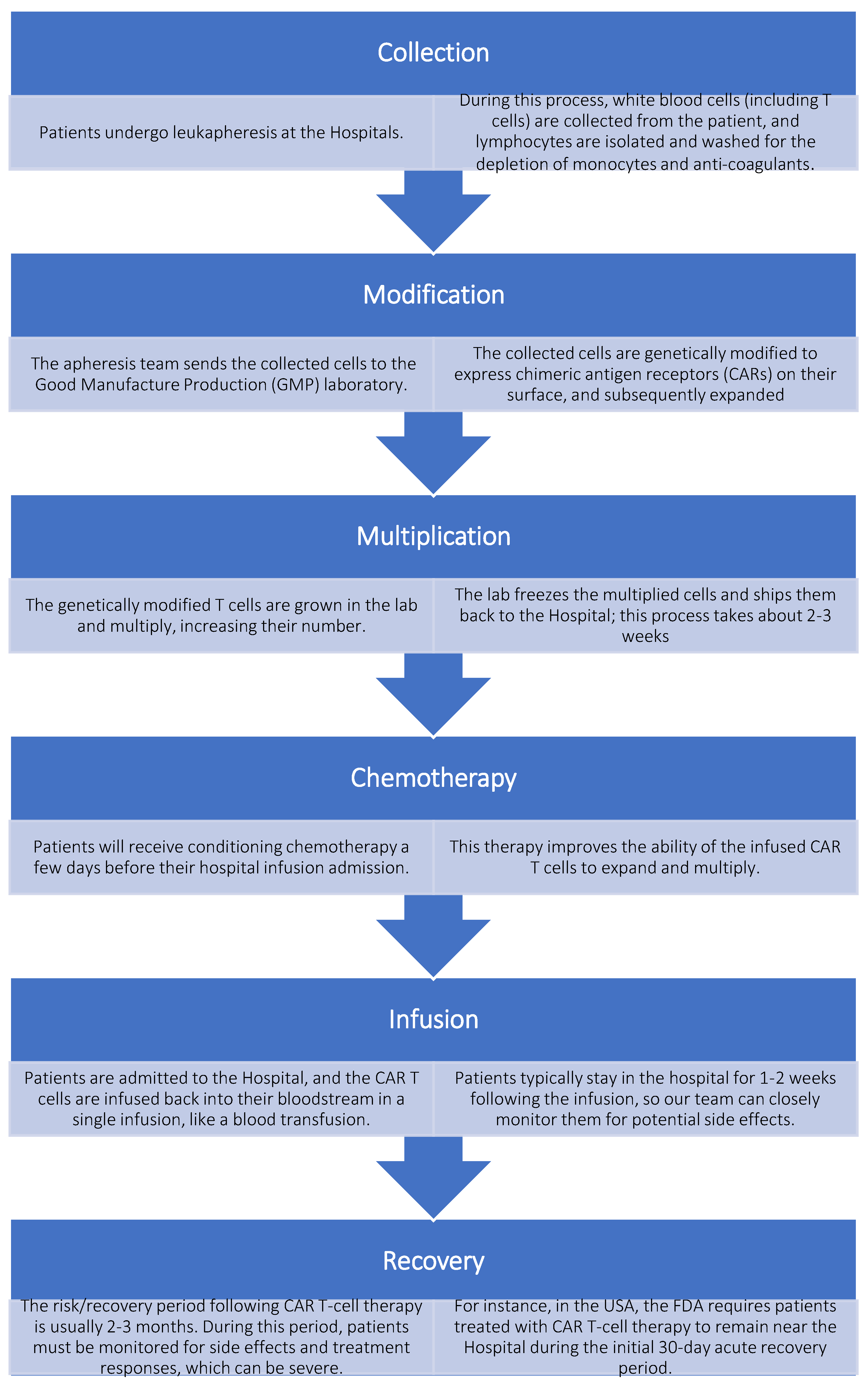

The procedure for manufacturing CAR-Ts ex vivo remains consistent despite various genetic modifications of T cells; however, it involves the patient’s participation. Subjects approved for CAR T-cell therapy typically undergo the following treatment process, as illustrated in

Figure 3.[

46]

3.1. How Is the CAR-T Cell Structure?

The CAR’s primary structure comprises a tumor-antigen receptor and a signal transduction domain.[

2] The tumor-antigen receptor recognizes specific tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), including proteins, glycoproteins, and other elements, while the signal transduction domain primarily enhances T-cell proliferation and differentiation. Diverse intracellular signal transduction domains characterize different generations of CAR structure. [

3] CAR structures of four generations have been described.[

4] The original CAR framework features an intracellular CD3ζ signaling module, which oversimplifies and conveys signals ineffectively.[

7] Although the first-generation CARs can specifically recognize TTAs and enhance T cell anti-tumor activity, their therapeutic effect is unsatisfactory in vivo due to their decreased proliferation ability.[

8] CAR’s second generation, which integrates a costimulatory domain, such as CD28 or 4-1BB, with the CD3ζ molecule, has remarkably improved cell multiplication and reduced senescence. [

10]

4. Risk Assessment While Working with LVs

HIV-derived LVV are powerful tools in genetic research and gene therapy applications. These vectors are derived from HIV but have been significantly modified to enhance safety while maintaining transduction efficiency. The evolution of vector systems has progressed through multiple generations as shown before. These advanced systems split viral components across multiple plasmids, eliminating essential pathogenic genes and incorporating self-inactivating (SIN) LTR configurations to minimize risks. Despite these safety improvements, working with LVV requires strict adherence to biosafety protocols to prevent laboratory-acquired infections and ensure patient safety in clinical applications. The fundamental biosafety concerns with HIV-derived LVV include their potential to generate replication-competent lentiviruses (RCL) through recombination events, the risk of insertional mutagenesis when integrating into the host genome, and the potential effects of the transgene products (e.g., oncogenes or toxins). Additionally, the common practice of pseudotyping with VSV-G expands cellular tropism, potentially increasing risks if exposure occurs. [

52] These concerns necessitate rigorous containment measures, thorough risk assessment, and comprehensive personnel training to ensure safe handling practices across both laboratory and clinical settings.[

63]

4.1. Modes of Transmission

LVs may be transmitted through skin penetration via puncture or absorption (from scratches, cuts, abrasions, dermatitis, or other lesions) and exposure to the eyes, nose, and mouth through mucous membranes.[

18,

63]

4.2. Containment Level

Working with LVV requires the use of Biological Safety Level 2+ (BSL-2+) practices and procedures. Biosafety Level 2+ (BSL-2+) is the commonly used term for laboratories where work with microorganisms is conducted, utilizing biosafety practices and procedures typically found in BSL-3 laboratories. Most research institutions still struggle to determine when to use this approach and which BSL-3 practices to employ, as BSL-2+ is not a recognized containment level. No standardized list of microorganisms, viral vectors, or research projects to be conducted within BSL-2+ environments. Each decision to use selected BSL-3 practices in a BSL-2 laboratory must be made via a risk assessment. [

64] Examples of when BSL-2+ may be appropriate include viral vectors with gene inserts consisting of oncogenes or genes of unknown function. Second-generation LVVs have an increased risk of recombination, which can generate replication-competent LVs.

4.3. Project Review Process

The project review process is part of the risk assessment process.[

65] This review includes several steps before work can be approved and commenced.[

66] The laboratory supervisor or the Principal Investigator (PI) must complete and submit a project registration document to the Biosafety Officer (BSO). The document must clearly outline the project’s purpose and detail the steps to be taken with the biohazardous material. Review and discuss the project registration document with the laboratory supervisor or PI, BSO, and, in some cases, selected Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC) members with expertise in BSL-2+ research. For example, a virologist may be asked to review a project involving viral vectors. A suitable BSL-2 laboratory space should be proposed, and the BSL-3 practices should be outlined. IBC review and consensus must occur before the project’s initiation. At the IBC meeting, the BSO outlines the proposed project and the BSL-3 practices for use in the BSL-2 laboratory space. The IBC members should agree on the appropriate BSL-3 practices for the proposed work and decide upon a suitable BSL-2 laboratory space. Risk communication and training must be conducted after IBC approval and before any work is performed in the laboratory. The BSO should review the required BSL-3 procedures with the laboratory supervisor or PI and his/her laboratory staff. Ideally, these should be written in the form of an SOP. Additionally, it is essential to review the laboratory space to ensure that the required BSL-2 elements are in place, including, but not limited to, biowaste containers, a sink with soap and paper towels, and certified biological safety cabinets (BSCs).[

64]

4.4. Selection of a BSL-2+ Lab Space

BSL-2 laboratories are often large spaces occupied by many personnel working on diverse projects and sharing laboratory equipment. This scenario may not be conducive to adhering to BSL-3 practices. Dedicating a separate BSL-2 laboratory space to the project that requires BSL-3 practices allows other projects to maintain standard BSL-2 practices. Creating a BSL-2+ lab space means dedicating a smaller BSL-2 or "tissue culture" laboratory room to the project. It allows limited access to only those listed on the research protocol who have received the necessary training.[

64]

5. Facility Considerations

The lab supervisor or the PI must designate a laboratory that fulfills the facility requirements outlined in the US CDC/NIH publications

Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories. [

64] It should be an inner lab with two doors between the BSC and the hallway. Air must flow from the hallway to this lab (in the negative direction, to the lab). All air must be exhausted outside the building, not recirculated. An Environmental Health and Safety (EHS) officer [

68] can evaluate the laboratory’s negative pressure status.

5.1. Engineering Controls

The following safety equipment must be used when working with LVVs:[

69]

-

o

Certified Class II BSCs;

-

o

Sealed centrifuge rotors and safety cups;

-

o

Vacuum lines with an in-line HEPA filter and a primary and secondary vacuum flask containing a 10% bleach solution.

5.2. Examples of Modifications to BSL-3 Practices

One example of a potential modification to BSL-3 practices for use in a BSL-2+ space is the management of waste.[

70] While decontamination within the immediate laboratory is preferable, removing materials from the decontamination facility is an option. All materials encountered with LVVs should be disinfected using a 1:10 bleach solution before disposal. Additionally, all work surfaces must be disinfected with a 1:10 bleach solution once work is completed and at the end of the workday. (Note: At least a 15-minute contact time is required for decontamination.)[

69]

5.3. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

When working with LVVs, the following personal protective equipment must be worn: gloves (consider double gloving depending on the procedures performed), a lab coat, goggles, and a face shield.[

69]

5.4. Waste Disposal Procedures

Non-Sharp Waste—All cultures, stocks, and cell culture materials must be disinfected and autoclaved before being disposed of in a double-lined biohazard box. Sharps Waste, including needles, syringes, razors, scalpels, Pasteur pipettes, and tips, must be disposed of in an approved, puncture-resistant sharps container. Sharps containers must not be filled more than 2/3 of their capacity.[

70]

5.5. Additional Considerations for Implementing BSL-2+

Consider whether it is appropriate for laboratory personnel to bring laboratory notebooks and portable electronic devices into and out of the BSL-2+ laboratory. The best practice is to prohibit this to avoid bringing contamination out of the laboratory, but provide provisions for information to be transmitted to the office through an electronic device dedicated for use within the BSL-2+ laboratory. [

69]Alternatively, a procedure could be implemented to wipe down a laptop with a disinfectant wipe before leaving the lab. If the BSL-2 laboratory is to be renovated or built for a project that utilizes BSL-3 practices, it may be beneficial to incorporate some BSL-3 laboratory facilities for convenience. Examples include installing a hands-free or automatically operated sink for hand washing and locating an anteroom between the laboratory and external areas.[

70]

As there is no "one size fits all" approach to implementing BSL-2+ practices, a risk assessment is crucial in determining whether BSL-3 practices are necessary in a BSL-2 laboratory facility and identifying the specific practices that will be required. Collaboration between the laboratory supervisor or PI, BSO, IBC, and laboratory personnel is crucial to a successful outcome. Modifying BSL-3 practices for work in a BSL-2 laboratory will depend on the work conducted, the risk assessment results, and your institution’s IBC. [

69]

5.6. Other Facility Infrastructure Requirements

The streamlining of workflows, enhancement of process robustness, and adoption of automated closed systems are encouraged to facilitate scalability and lower the cost of goods, while preserving the efficiency of CAR-T (CAR-NK) cell products. To achieve commercial-scale production of CAR-T (CAR-NK) cell therapies, end-to-end automation is desirable, including but not limited to fully automated closed systems and partially automated systems. Fully automated closed systems can be used in less stringent cleanrooms; however, the step of the final product should still be performed in an ISO 7 (Class 10,000, Clean C) cleanroom environment. (See

Table 4).

Table 4.

Cleanroom classification guidelines.

Table 4.

Cleanroom classification guidelines.

| Cleanroom Standard |

Cleanroom Classification Guidelines |

| ISO 14644-1 |

Class 3 |

Class 4 |

Class 5 |

Class 6 |

Class 7 |

Class 8 |

| EU GMP (at rest) |

- |

- |

A/B |

- |

C |

D |

| US Federal Standard 209F (replaced by ISO 14644 in 2011 |

1 |

-10 |

100 |

1,000 |

10,000 |

100,000 |

In case of cell isolation involving open manipulation, steps must be carried out in an ISO 5 (Class 100) BSC. The environment surrounding the BSCs must maintain aseptic processing operations for cellular therapies that are manipulated and manufactured under cGMPs; the environment surrounding the ISO 5 (Class 100) BSCs should be controlled and classified as an ISO 7 (Class 10,000, Clean C) clean room. ISO 5 (formerly Class 100) BSCs must comply with ISO 5 standards, which include a HEPA-filtered laminar airflow over the work area and a UV sterilization lamp as a minimum. [

64]

6. Recommendations for Working with LVVs

6.1. Practices and Procedures While Working with LVVs

The BSO and the IBC specified the following additional practices and procedures. For instance, the laboratory must have limited access. According to signage posted on the door, only individuals listed in the project registration, the BSO, and select Environmental Health and Safety (EH&S) department members are permitted access. The laboratory supervisor, PI, BSO, or project personnel must escort the janitorial and maintenance staff to the laboratory.[

70,

71] Phone numbers for the laboratory supervisor, PI, and key laboratory staff are posted during an off-hour emergency. BSL-2 work is permitted in the BSL-2+ laboratory, provided that it is performed using the same BSL-3 practices as those required for the LV project.[

68] The laboratory supervisor or PI developed an SOP detailing the work practices and procedures as required by the IBC, using a template provided by the BSO. The BSO reviewed the SOP, which is used for training additional project personnel. Signage for the laboratory door with the universal biohazard symbol includes the Laboratory supervisor or PI’s name, a list of approved/trained project personnel, including others who may have approved access (BSO, EH&S personnel), materials in use (LV and human cells), emergency contacts, and phone numbers. The signage indicates that only approved/trained personnel may enter, and an approved/trained person must accompany visitors.[

71]

Based on consultation with the institution’s occupational health physician, no medical surveillance is required for laboratory members working on the project. Laboratory staff were instructed to contact the occupational health physician with any medical questions or concerns. Since human materials are used in the project, all project personnel were offered Hepatitis B vaccination in accordance with the

Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) Bloodborne Pathogen and Hazard Communications Standards. [

68] Additionally, project personnel were provided with a review of the institution’s procedure for immediately reporting all occupational injuries and illnesses.[

69]

In addition to the two BSCs already in the BSL-2+ laboratory, a tabletop centrifuge, a microscope, two incubators, and a laptop computer were purchased and designated for the laboratory. The laptop transmits notes outside the laboratory, as notebooks cannot be taken in and out.[

70]

The PPE consists of a disposable solid front gown with cuffed sleeves, safety glasses with side shields, and nitrile gloves. In the entry area of the laboratory, coat hooks are available, allowing gowns to be hung up for reuse if deemed non-contaminated. A set of hooks immediately outside the laboratory is available to hang cotton laboratory coats utilized for work in the main BSL-2 laboratory. Each researcher is required to bring a box of gloves into the BSL-2+ laboratory in the appropriate size. Sharps such as Pasteur pipettes and needles are prohibited in the BSL-2+ laboratory. Plasticware is substituted for glass, and plastic pipette tips are allowed. All work is conducted in the BSC, including loading and unloading centrifuge safety cups for the laboratory’s tabletop centrifuge. [

70]

Freshly prepared bleach solutions and 70% ethanol are available and utilized in the laboratory to disinfect surfaces and equipment. There is no autoclave in the BSL-2+ laboratory or the larger BSL-2 laboratory. While an autoclave located in another part of the building is used for media preparation, the institution utilizes a vendor’s services to dispose of biomedical waste and sharps. [

70]

The solid, non-sharp waste, including but not limited to plastic culture flasks and gloves, is collected within the BSC in a small red biohazard bag contained within a Nalgene container with a lid. When two-thirds full, the researcher removed the bag, tied it at the top with a rubber band, and placed it within a vendor-supplied large cardboard waste box lined with two red bags. When full, the box is taped, labeled, and placed immediately outside of the BSL-2+ laboratory for the vendor to remove from the facility and transport for off-site incineration.[

70]

The used pipette tips generated in the BSC are immediately put in a sharp plastic container located within the BSC. Liquid waste is treated with mercury-free bleach (1 to 9 parts liquid waste), allowed to sit for at least 30 minutes, and carefully disposed of via the sink. Materials in labeled secondary containers can be removed from the laboratory and moved to the main BSL-2 laboratory for storage in the -80°C freezer.[

70] Additionally, fixed cells may be removed from the laboratory in a secondary container for cell sorting. A laboratory member must be appointed to serve as the BSL-2+ “manager” and oversee daily lab operations, including ensuring that adequate PPE and supplies, such as disinfectants, are available, monitoring conditions in the lab, including PPE usage, and reporting issues that may require retraining. The BSL-2+ manager coordinates with and accompanies the maintenance department and equipment vendors when access to the BSL-2+ laboratory is necessary.[

70]

6.2. Special Handling Procedures

Cells exposed to LVVs may not be removed from the laboratory for experimental purposes unless inactivated by approved procedures. If culture needs to be aerated, it must be done slowly and in a manner that minimizes the potential for aerosol creation. This action must be carried out in class II BSCs. Pouring and pipetting samples must be done gently and slowly, and must be carried out in a Class II BSC.

Extra precautions must be taken when using sharps. Appropriate substitutes for sharp items must be used whenever they are available. Sharps (including needles and Pasteur pipettes) may not be used to work with LV-infected cell cultures or harvest virus pellets. Use plastic aspiration pipettes instead of glass Pasteur pipettes.[

63] For aspiration, use a plastic vacuum flask with a second vacuum flask connected to it as a backup, using non-collapsible tubing that can withstand disinfection. Attach a hydrophobic filter and a HEPA filter (or a combination filter) to the second vacuum flask to prevent anything from being sucked into the house vacuum system. These three items must be connected to a series from the vacuum source in the hood or a vacuum pump.[

63]

6.3. Impatient Design Rooms for CAR-T Application to Human Subjects

There must be a designated outpatient care area that protects the patient from contagious agents and allows for patient isolation, confidential examination, evaluation, and administration of intravenous fluids, medications, and blood products. For procedures performed in an ambulatory setting, a designated area with adequate space and design must be available to minimize the risk of microbial contamination. Provisions must be in place for prompt evaluation and treatment by an attending physician available 24/7.[

72]

7. Emergency Procedures and Exposure Management

7.1. Exposure Response and First Aid Measures

Immediate response to potential exposures to LVV is crucial for minimizing risks. In the event of exposure, personnel should immediately:

(1) Flush mucous membranes (eyes, nose, mouth) with copious amounts of water for 15 minutes at an eyewash station;

(2) Wash exposed skin with soap and water for at least 15 minutes (5 minutes for intact skin); and

(3) for puncture wounds or cuts, encourage bleeding by gently squeezing the area while washing with soap and water.

After providing immediate first aid, the affected individual should seek medical evaluation promptly, even if the exposure seems minor. Medical providers should be informed about the specific nature of the LVV involved, including the method of generation, the transgene being expressed, and any other relevant details. [

73]

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) with antiretroviral drugs may be considered for significant exposures to HIV-based LVV. Some guidelines recommend that physicians consider initiating a 7-day course of a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI), such as tenofovir, and an integrase inhibitor, such as raltegravir, as soon as possible after exposure (within 72 hours). [ 73 ] The need for PEP should be determined through medical evaluation based on the type and extent of exposure. All exposure incidents must be reported to the supervisor and the institutional biosafety office immediately, with completion of appropriate incident report forms and follow-up as required by institutional policies.

7.2. Spill Response and Decontamination Procedures

Spill response procedures for LVV depend on the volume and location of the spill. For small spills (<1 liter) inside a biological safety cabinet, the sash should be closed and the cabinet allowed to operate for 15 minutes before beginning cleanup. For spills outside the BSC, personnel should immediately evacuate the area and allow 30 minutes for aerosols to settle before re-entering. Appropriate PPE should be done before cleanup, including double gloves, a lab coat, eye protection, and respiratory protection if significant aerosolization may have occurred. The spill cleanup process involves covering the area with absorbent material, applying an appropriate disinfectant (such as a 1:10 fresh bleach solution), and working from the perimeter toward the center to prevent the spread of contamination. After allowing 30 minutes of contact time, the materials can be carefully collected for disposal as biohazardous waste.[

64]

Decontamination protocols for LVV require the use of appropriate disinfectants with demonstrated efficacy against enveloped viruses. For instance, the NIH guidelines recommend sodium hypochlorite (0.5%: use a 1:10 dilution of fresh bleach) with a minimum contact time of 20 minutes, although 5% phenol or a 70% ethanol/isopropanol solution is also effective. [

73] All potentially contaminated materials must be decontaminated before being disposed of or reused. Work surfaces and equipment should be decontaminated after each use and at the end of each workday. Other guidelines emphasize the importance of using absorbent pads on work surfaces within biological safety cabinets to prevent spills from generating aerosols and to facilitate decontamination. [

64,

68,

69]

8. Concluding Remarks

LLVs are widely used in cell gene therapy to treat genetic diseases, cancer, and other chronic diseases. These diseases include, but are not limited to, cystic fibrosis, sickle cell anemia, and various types of cancer. While LVs are primarily a research tool for introducing a gene product into in vitro systems or animal models, their applications in therapeutic development are significant, particularly in adoptive cell transfer therapeutics. These include CAR-T, CAR-NK, TCR-T, and TIL therapies, representing the primary use of LVs in this field.[

74]

LLVs are opening new doors in regenerative medicine and tissue engineering. By effectively transducing stem cells, LLVs enable the genetic modification of these cells, offering a promising avenue for a better understanding and treatment of various diseases. [

75]

Although widely used, shortages persist in LVV utilization in CAR-T establishment. However, several shortcomings exist that are hard to bypass for LVVs. First, in CAR gene integration into T cells, LVVs often undergo random integration into the cellular genome, which can potentially cause adverse effects on the host genome. It can lead to unintended gene silencing, overexpression, or genetic mutations, thereby increasing potential safety risks. [

8]

Moreover, the limited transcriptional capacity of LVVs restricts the size and complexity of the CAR gene payloads, as well as the associated regulatory elements that can be accommodated. Lastly, the large-scale production of LVVs for clinical applications requires matching BSL2+ or BSL3 good manufacturing practice (GMP)-graded laboratory and manufacturing reagents, resulting in close-to-prohibitive manufacturing costs and regulatory hurdles. [

67,

68,

74]

Several methods can be utilized for gene modification of T cells, categorized into viral vectors and non-viral. However, these methods, including electroporation via the transposon system, are inefficient in achieving stable CAR gene expression, although the produced CAR-T cells exhibit faster cytotoxicity in vitro. This inefficiency highlights the need for safer and lower-cost virus-free gene delivery vectors, which are typically represented by transposon systems, CRISPR/Cas9 systems, and mRNA electroporation platforms.[

59,

60,

61] Autologous CAR-T cells have demonstrated remarkable clinical outcomes, significantly altering the treatment of blood cancers. However, there are still issues that prevent patients from receiving CAR-T cell therapy. In addition to the efficacy and safety issues of CAR-T therapy mentioned in the previous sections, the high cost, complex process, and lengthy waiting time of approximately 3 weeks required for manufacturing personalized T cells are also factors that hinder patients’ access to treatment [

76]. Consequently, to overcome these obstacles, the development of universal allogeneic CAR-T cells (also known as “off-the-shelf” CAR-T cells) and other CARs using alternative effector cells is underway.[

77]

Various alternative engineering approaches and sourcing strategies have recently been developed for generating CAR-engineered cells. Given the successful applications of CAR-T therapy in oncology, developing additional strategies with new technologies and improved ease of operation to reduce costs and increase accessibility is warranted. Continuous advances in broadening cell sources and engineering approaches have revealed new ways to improve the supply of CAR-immune cells and simplify the manufacturing of CAR products.[

77] The diverse sourcing strategies, encompassing autologous, donor-derived, third-party, and off-the-shelf cellular products, have unveiled a spectrum of cellular reservoirs with distinct attributes and potential. These strategies have expanded the repertoire of therapeutic candidates and addressed limitations associated with cell availability and functionality. Moreover, ingenious engineering approaches have propelled the optimization of CAR-based immunotherapies. Techniques such as genome editing, synthetic biology, and multi-gene integration have enabled the tailoring of immune cells with enhanced persistence, specificity, and safety profiles. Concurrently, advancements in modular CAR designs, incorporation of costimulatory domains, and switchable CAR systems have fine-tuned the therapeutic response and mitigated adverse events, underscoring the remarkable progress achieved in refining CAR-engineered immune cells.[

78]

The ability of LVVs to generate CAR-T cells in vivo has garnered considerable attention, as it could eliminate the need for ex vivo isolation and activation of T cells, thereby reducing both the cost and time required for in vitro production.[

79]

Further investigations will be warranted to comprehensively elucidate the long-term safety and efficacy of these advanced therapies. The development of standardized protocols for sourcing, engineering, and characterizing CAR-modified immune cells will be instrumental in ensuring reproducibility and facilitating regulatory approval.[

80]

Biosafety practices for HIV-derived LVVs continue to evolve as vector technology advances and our understanding of potential risks improves. The current standards emphasize evidence-based approaches that focus on actual risks rather than predetermined prescriptions, allowing for more flexible and effective safety protocols. The international harmonization of biosafety guidelines facilitates global collaboration in LVV research and therapy development. As these technologies increasingly move into clinical applications, the integration of GMP standards with traditional biosafety practices creates a comprehensive framework for ensuring safety, from the laboratory bench to the patient’s bedside. [

64]

Emerging challenges in LVVs biosafety include the growing use of CRISPR/Cas9 systems delivered via LVV, which necessitate enhanced containment due to their potential for genotoxicity. The scale-up of production for clinical applications also presents novel biosafety considerations that differ from research-scale work. Future developments are likely to include improved vector systems with even greater safety profiles, such as vectors with targeted integration systems that reduce the risks of insertional mutagenesis. Continuous personnel education and training remain essential components of an effective biosafety program, as human factors continue to be the most significant variable in preventing laboratory accidents and exposures. Through diligent application of current guidelines and adaptive response to new challenges, the scientific community can continue to harness the power of LVV technology while maintaining the highest standards of safety for both laboratory personnel and patients.

Enhanced and collaborative efforts between medical centers, the biotechnology industry, pharmaceutical companies, and nanotechnology institutes are poised to expedite the translation of these cutting-edge approaches into transformative clinical interventions, such as the in vivo generation of CAR-T cells, potentially reshaping the landscape of cancer and other immune-related diseases. As we navigate these frontiers, an exciting era of precision immunotherapy emerges, promising personalized, potent, and durable treatments for patients in need. This potential inspires us to continue pushing the boundaries of scientific research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing—original draft, editing, figures preparation, RARJ; Writing—Review and Editing, LAH; Search the medical literature, writing, editing, GRN and DA; Resources, supervision, review of the manuscript, FMAK; Resources, supervision, review-editing draft, YVC; Conceptualization, supervision, project management, and final review of the manuscript, AABH. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable, as it is a literature review.

Data Availability Statement

This review article did not include original data; all material cited has been referenced in the text and the bibliography.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support received from the ADSCC for the publication of this article. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used the Mendeley Reference Manager system and software for bibliography citation. All authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors are employees of the ADSCC and declare no conflict of interest. No financial support or relationships were made with affiliated organizations that could have influenced the submitted work.

Open Access

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, if you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. Parts of the figures were drawn using pictures from Servier Medical Art. Servier Medical Art by Servier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License (

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/). The images or other third-party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless stated otherwise in a credit line to the material.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 4-1BB or CD137 |

A surface glycoprotein that belongs to the tumor necrosis factor receptor family |

| AAVs |

Adeno-associated virus |

| ALL |

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| BSCs |

Biological Safety Cabinets |

| BSL-2+ |

Biological Safety Level 2+ |

| BSL-3 |

Biological Safety Level 3 |

| BSO |

Biosafety Office |

| BCMA |

Anti-B cell maturation antigen |

| CA |

Capsid |

| CAR-CIK |

CAR-cytokine-induced killer cell |

| CAR-MΦ |

CAR-macrophage |

| CAR-NK |

CAR-natural killer cell |

| CAR-T |

Cell chimeric antigen receptor T cell |

| CD19 |

Cluster of differentiation 19 . |

| CD28 |

Cluster of differentiation 28. |

| CD3ζ |

Accessory signaling molecule |

| CRISPR |

Clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats |

| DLBCL |

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. |

| Env |

Envelop |

| EHS |

Environmental Health and Safety |

| EIAV |

Equine infectious anemia virus |

| FDA |

Food and Drug Administration (USA) |

| FIV |

Feline immunodeficiency virus |

| FL |

Follicular lymphoma |

| Gag |

Group-specific antigen |

| GMP |

Good manufacturing practice |

| HIV |

Human immunodeficiency virus |

| HSCT |

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation |

| IN |

Integrase |

| IBC |

Institutional Biosafety Committee |

| kb |

Kilo bytes |

| KI |

Knocking-In |

| KO |

Knocking Out |

| LTR |

Long terminal repeat |

| LV |

Lentivirus |

| LVVs |

Lentivirus vectors |

| MA |

Matrix |

| MCL |

Mantle cell lymphoma |

| MM |

Multiple myeloma |

| NC |

Nucleocapsid |

| NMPA |

National Medical Products and Drug Administration (PR China) |

| PPE |

Personal Protective Equipment |

| PA |

Phosphatidic Acid |

| PI |

Principal Investigator |

| Pol |

Polymerase |

| Poly A |

Poly-Adenine tail |

| PR |

Protease |

| R |

Repeat region |

| RCL |

Replication-competent lentivirus |

| Rev |

Regulator of the expression of viral protein |

| RNA |

Ribonucleic acid |

| RRE |

Rev response element |

| RT |

Reverse transcriptase |

| sgRNA |

Single guide RNA |

| shRNA |

Short hairpin RNA |

| SOP |

Standard Operating Procedure |

| SIV |

Simian immunodeficiency virus |

| TAA |

Tumor-associated antigens |

| Tat |

Trans-activator of transcription |

| U3 |

Unique 3’ region |

| U5 |

Unique 5’ region |

| Vif |

Viral infectivity factor |

| Vpr |

Viral protein R |

| Vpu |

Viral protein U |

| VSV-G |

Vesicular stomatitis virus G |

| Ѱ |

Retroviral psi packaging element |

References

- Yang G. Lentiviral Vectors in CAR-T Cell Manufacturing: Biological Principles, Manufacturing Process, and Frontier Development. Highl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2023;74:172 80. [CrossRef]

- Sadelain M, Rivière I, Brentjens R. Targeting tumours with genetically enhanced T lymphocytes. Nat Rev Cancer 2003;3:35–45. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Z, Chen Y, Francisco NM, Zhang Y, Wu M. The Application of CAR-T Cell Therapy in Hematological Malignancies: Advantages and Challenges. Acta Pharm Sin B 2018;8:539–51. [CrossRef]

- Han D, Xu Z, Zhuang Y, Ye Z, Qian Q. Current Progress in CAR-T Cell Therapy for Hematological Malignancies. J Cancer 2021;12:326–34. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y-J, Abila B, Mostafa Kamel Y. CAR-T: What Is Next? Cancers (Basel) 2023;15:663. [CrossRef]

- FDA Package Insert-KYMRIAH. [(accessed on 13 December 2022)];2022 Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/107296/download.

- Eshhar Z, Waks T, Gross G, Schindler DG. Specific activation and targeting of cytotoxic lymphocytes through chimeric single chains consisting of antibody-binding domains and the gamma or zeta subunits of the immunoglobulin and T-cell receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:720–4. [CrossRef]

- Heuser C, Hombach A, Lösch C, Manista K, Abken H. T-cell activation by recombinant immunoreceptors: Impact of the intracellular signalling domain on the stability of receptor expression and antigen-specific activation of grafted T cells. Gene Ther 2003;10:1408–19. [CrossRef]

- [FDA. Package Insert-YESCARTA. 2022. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/108377/download (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- [Bretscher PA. A two-step, two-signal model for the primary activation of precursor helper T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:185–90. [CrossRef]

- FDA. Package Insert-TERAKUS. 2022. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/140409/download (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Dong W, Kantor B. Lentiviral Vectors for Delivery of Gene-Editing Systems Based on CRISPR/Cas: Current State and Perspectives. Viruses 2021;13:1288. [CrossRef]

- FDA. Package Insert-ABECMA. 2021. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/147055/download (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- van Heuvel Y, Schatz S, Rosengarten JF, Stitz J. Infectious RNA: Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Biology, Therapeutic Intervention, and the Quest for a Vaccine. Toxins (Basel) 2022;14:138. [CrossRef]

- FDA. Package Insert-BREYANZI. 2022. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/145711/download (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Labbé RP, Vessillier S, Rafiq QA. Lentiviral Vectors for T Cell Engineering: Clinical Applications, Bioprocessing and Future Perspectives. Viruses 2021;13:1528. [CrossRef]

- FDA. Package Insert-CARVYKTI. 2022. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/156560/download (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Meng B, Lever AM. Wrapping up the bad news – HIV assembly and release. Retrovirology 2013;10:5. [CrossRef]

- National Medical Products Administration. Equecabtagene Autoleucel Injection Approved with Conditions by China NMPA. https://english.nmpa.gov.cn/2023-06/30/c_940256.htm 2023, June 30 (Accessed 8 August 2025).

- Ying Z, Song Y, Yang H, Guo Y, Li W, Zou D, Zhou D, Wang Z, Zhang M, Wu J, Liu H, Wang Ch, Yang S, Zhou Z, Qin Y, Zhu J. Two-year follow-up result of RELIANCE study, a multicenter phase 2 trial of relmacabtagene autoleucel in Chinese patients with relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:7529–7529.

- Addgene. Lentiviral Guide. https://www.AddgeneOrg/Guides/Lentivirus/ 2025.

- Gale RP. Chimeric antigen receptor-T-cell therapy: China leading the way. Blood Science 2022;4:176–176. [CrossRef]

- Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, Waller EK, Borchmann P, McGuirk JP, Jäger U, Jaglowski S, Andreadis Ch, Westin JR, Fleury I, Bachanova V, Foley SR, Ho PJ, Mielke, Magenau JM, Holte H, Pantano S, Pacaud LB, Awasthi R, Chu J, Anak O, Salles G, Maziarz RT. Tisagenlecleucel in Adult Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:45–56. [CrossRef]

- Pasquini MC, Hu Z-H, Curran K, Laetsch T, Locke F, Rouce R, Pulsipher MA, Phillips Ch L, Keating A, Frigault MJ, Salzberg D, Jaglowski S, Sasine JP, Rosenthal J, Ghosh M, Landsburg D, Margossian S, Martin PL, Kamdar MK, Hematti P, Nikiforow S, Turtle C, Perales MA, Steinert P, Horowitz MM, Moskop A, Pacaud L, Yi L, Chawla R, Bleickardt E, Grupp S. Real-world evidence of tisagenlecleucel for pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood Adv 2020;4:5414–24. [CrossRef]

- Rezalotfi A, Fritz L, Förster R, Bošnjak B. Challenges of CRISPR-based gene editing in primary T cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:1689. 10.3390/ijms23031689.

- Locke FL, Ghobadi A, Jacobson CA, Miklos DB, Lekakis LJ, Oluwole OO, Lin Y, Braunschweig I, Hill BT, Timmerman JM, Deol A, Reagan PM, Stiff P, Flinn IW, Farooq U, Goy A, McSweeney PA, Munoz J, Siddiqi T, Chavez JC, Herrera AF, Bartlett NL, Wiezorek JS, Navale L, Xue A, Jiang Y, Bot A, Rossi JM, Kim JK, Go WY, Neelapu SS. Long-term safety and activity of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma (ZUMA-1): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 1–2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:31–42. [CrossRef]

- Neelapu SS, Dickinson M, Munoz J, Ulrickson ML, Thieblemont C, Oluwole OO, Herrera AF, Ujjani Ch.S, Yi Lin Y, Riedell PA, Kekre N, de Vos S, Lui Ch, Milletti F, Dong J, Xu H, Chavez JC. Axicabtagene ciloleucel as first-line therapy in high-risk large B-cell lymphoma: the phase 2 ZUMA-12 trial. Nat Med 2022;28:735–42. [CrossRef]

- Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, Lekakis LJ, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, Braunschweig I, Oluwole OO, Siddiqi T, Lin Y, Timmerman JM, Stiff PJ, Friedberg JW, Flinn IW, Goy A, Hill BT, Smith MR, Deol A, Farooq U, McSweeney P, Munoz J, Avivi I, Castro JE, Westin JR, Chavez JC, Ghobadi A, Komanduri KV, Levy R, Jacobsen ED, Witzig TE, Reagan P, Bot A, Rossi J, Navale L, Jiang Y, Aycock J, Elias M, Chang D, Wiezorek J, Go WY. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-Cell Therapy in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2531–44. [CrossRef]

- Fosum Pharma. Fosun Kite’s First CAR-T Product Yescarta® (Axicabtagene Ciloleucel) Approved for Marketing. June 23, 2021. Available at: Fosun Kite’s First CAR-T Product Yescarta®(Axicabtagene Ciloleucel) Approved for Marketing_R&D News_R&D News_R&D_Fosun Pharma. (Accessed 13 August 2025).

- Andrea AE, Chiron A, Mallah S, Bessoles S, Sarrabayrouse G, Hacein-Bey-Abina S. Advances in CAR-T Cell Genetic Engineering Strategies to Overcome Hurdles in Solid Tumors Treatment. Front Immunol 2022;13. [CrossRef]

- Ball G, Lemieux C, Cameron D, Seftel MD. Cost-Effectiveness of Brexucabtagene Autoleucel versus Best Supportive Care for the Treatment of Relapsed/Refractory Mantle Cell Lymphoma following Treatment with a Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor in Canada. Curr Oncol 2022;29:2021–45. [CrossRef]

- Frey N V. Approval of brexucabtagene autoleucel for adults with relapsed and refractory acute lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2022;140:11–5. [CrossRef]

- Mann H, Comenzo RL. Evaluating the Therapeutic Potential of Idecabtagene Vicleucel in the Treatment of Multiple Myeloma: Evidence to Date. Onco Targets Ther 2022;Volume 15:799–813. [CrossRef]

- Munshi NC, Anderson LD, Shah N, Madduri D, Berdeja J, Lonial S, Raje N, Lin Y, Siegel D, Oriol A, Moreau Ph, Yakoub-Agha I, Delforge M, Cavo M, Einsele H, Goldschmidt H, Weisel K, Rambaldi A, Reece D, Petrocca F, Massaro M, Connarn JN, Kaiser S, Patel P, Huang L, Campbell TB, Hege K, San-Miguel J. Idecabtagene Vicleucel in Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:705–16. [CrossRef]

- Kamdar M, Solomon SR, Arnason J, Johnston PB, Glass B, Bachanova V, Ibrahimi S, Mielke S, Mutsaers P, Hernandez-Ilizaliturri F, Izutsu K. Lisocabtagene maraleucel versus standard of care with salvage chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation as second-line treatment in patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma (TRANSFORM): results from an interim analysis of an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2022;399:2294–308. [CrossRef]

- Iragavarapu C, Hildebrandt G. Lisocabtagene Maraleucel for the treatment of B-cell lymphoma. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2021;21:1151–6. [CrossRef]

- Abramson JS, Palomba ML, Gordon LI, Lunning MA, Wang M, Arnason J, Mehta A, Purev E, Maloney DG, Andreadis C, Sehgal A. Lisocabtagene maraleucel for patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphomas (TRANSCEND NHL 001): a multicentre seamless design study. The Lancet 2020;396:839–52. [CrossRef]

- National Medical Products Administration. Ciltacabtagene Autoleucel Injection Approved for Marketing by China NMPA. 2025, Feb. 2025. https://english.nmpa.gov.cn/2025-02/19/c_1073597.htm (Accessed 8 August 2025).

- Berdeja JG, Madduri D, Usmani SZ, Jakubowiak A, Agha M, Cohen AD, Stewart AK, Hari P, Htut M, Lesokhin A, Deol A. Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): a phase 1b/2 open-label study. The Lancet 2021;398:314–24. [CrossRef]

- Martin T, Usmani SZ, Berdeja JG, Agha M, Cohen AD, Hari P, Avigan D, Deol A, Htut M, Lesokhin A, Munshi NC. Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, an Anti–B-cell Maturation Antigen Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy, for Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma: CARTITUDE-1 2-Year Follow-Up. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:1265–74. [CrossRef]

- Legend Biotech. CARVYKTI® (ciltacabtagene autoleucel) Granted Conditional Approval by the European Commission for the Treatment of Patients with Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma. 2022 May 26. Available at: https://investors.legendbiotech.com/news-releases/news-release-details/carvyktir-ciltacabtagene-autoleucel-granted-conditional-approval.

- Hu Y, Feng J, Gu T, Wang L, Wang Y, Zhou L, et al. CAR T-cell therapies in China: rapid evolution and a bright future. Lancet Haematol 2022;9:e930–41. [CrossRef]

- Abu Haleeqa MI, El-Najjar I, Afifi YK, Ali SA, Alsaadawi N, Dennison JD, Sachdev M, Obeidat SA, Castillo-Aleman YM, Handgretinger R, Ibrahim A, Wahdan R, al Kaabi F, Ventura-Carmenate Y, Hadi LA, Hernández-Ramírez A, Al Karam M. Establishment of CD19-CAR-T Cell Production and Treatment of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma in the United Arab Emirates. Blood 2024;144:7268–7268. [CrossRef]

- Stroncek DF, Tran M, Frodigh SE, David-Ocampo V, Ren J, Larochelle A, Sheikh V, Sereti I, Miller JL, Longin K, Sabatino M. Preliminary evaluation of a highly automated instrument for the selection of CD34+ cells from mobilized peripheral blood stem cell concentrates. Transfusion 2015; 56(2): 511–517. [CrossRef]

- Nickolay LE, Cheung GWC, Pule M, Thrasher A, Johnston I, Kaiser A, Pule M, Thrasher A, Qasim W. Automated lentiviral transduction of T cells with CARs using the CliniMACS Prodigy. European Society of Gene and Cell Therapy Collaborative Congress 2015, Helsinki, Finland. A26.

- Wang X, Rivière I. Clinical manufacturing of CAR T cells: foundation of a promising therapy. Mol Ther Oncolytics 2016;3:16015. [CrossRef]

- Lana, M.G., Strauss, B.E. Production of Lentivirus for the Establishment of CAR-T Cells. In: Swiech, K., Malmegrim, K., Picanço-Castro, V. (eds) Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells. Methods in Molecular Biology, 2020; 2086. Humana, New York, NY. [CrossRef]

- Dufait I, Liechtenstein T, Lanna A, Bricogne C, Laranga R, Padella A, Breckpot K, Escors D. Retroviral and Lentiviral Vectors for the Induction of Immunological Tolerance. Scientifica (Cairo) 2012;2012:1–14. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.F.; Emerman, M. Passage through mitosis is required for oncoretroviruses but not for the human immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 1994; 68, 510–516. [CrossRef]

- Kantor, B.; Bailey, R.M.; Wimberly, K.; Kalburgi, S.N.; Gray, S.J. Methods for Gene Transfer to the Central Nervous System. Agric. Food Prod. 2014, 87, 125–197. [CrossRef]

- Cronin J, Zhang XY, Reiser J. Altering the tropism of lentiviral vectors through pseudotyping. Curr Gene Ther. 2005 Aug;5(4):387-98. [CrossRef]

- Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Varmus HE. The Interactions of Retroviruses and their Hosts. In: Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Varmus HE, editors. Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor (NY): Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. PMID: 21433350.

- Naldini, L.; Blomer, U.; Gage, F.H.; Trono, D.; Verma, I.M. Efficient transfer, integration, and sustained long-term expression of the transgene in adult rat brains injected with a lentiviral vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996, 93, 11382–11388. [CrossRef]

- Blömer U, Naldini L, Kafri T, Trono D, Verma IM, Gage FH. Highly efficient and sustained gene transfer in adult neurons with a lentivirus vector. J Virol. 1997 Sep;71(9):6641-9. [CrossRef]

- Dull T, Zufferey R, Kelly M, Mandel RJ, Nguyen M, Trono D, Naldini L. A third-generation lentivirus vector with a conditional packaging system. J Virol. 1998 Nov;72(11):8463-71. [CrossRef]

- Kafri T, Blömer U, Peterson DA, Gage FH, Verma IM. Sustained expression of genes delivered directly into liver and muscle by lentiviral vectors. Nat Genet. 1997 Nov;17(3):314-7. [CrossRef]

- Zufferey R, Nagy D, Mandel RJ, Naldini L, Trono D. Multiply attenuated lentiviral vector achieves efficient gene delivery in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 1997 Sep;15(9):871-5. [CrossRef]

- Cockrell AS, Ma H, Fu K, McCown TJ, Kafri T. A trans-lentiviral packaging cell line for high-titer conditional self-inactivating HIV-1 vectors. Mol Ther. 2006 Aug;14(2):276-84. [CrossRef]

- Zufferey R, Donello JE, Trono D, Hope TJ. The Woodchuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element enhances the expression of transgenes delivered by retroviral vectors. J Virol. 1999 Apr;73(4):2886-92. [CrossRef]

- Zennou V, Petit C, Guetard D, Nerhbass U, Montagnier L, Charneau P. HIV-1 genome nuclear import is mediated by a central DNA flap. Cell. 2000 Apr 14;101(2):173-85. [CrossRef]

- Di Nunzio F, Felix T, Arhel NJ, Nisole S, Charneau P, and Beignon AS. "HIV-derived vectors for therapy and vaccination against HIV." Vaccine 2012 30; 15: 2499-2509. [CrossRef]

- Beignon A, Mollier K, Liard C, Coutant F, Munier S, SRivière J, Souque P, Charneau P. Lentiviral Vector-Based Prime/Boost Vaccination against AIDS: Pilot Study Shows Protection against Simian Immunodeficiency Virus SIVmac251 Challenge in Macaques. .2009. J Virol 83. [CrossRef]

- Deichmann A, Schmidt M. Biosafety considerations using gamma-retroviral vectors in gene therapy. Curr Gene Ther. 2013 Dec;13(6):469-77. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health. Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories. 6th Edition. https://www.cdc.gov/labs/pdf/SF__19_308133-A_BMBL6_00-BOOK-WEB-final-3.pdf (Accessed: 8 August 2025).

- Cherkassky L, Morello A, Villena-Vargas J, Feng Y, Dimitrov DS, Jones DR, Sadelain M, Adusumilli PS. Human CAR T cells with cell-intrinsic PD-1 checkpoint blockade resist tumor-mediated inhibition. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 3130–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version].

- Abu Dhabi Department of Health (DoH). DOH/RIC/ST/LAGRSP/V1/2023. Standard for Laboratory Accreditation for Genomic-Related Services and Products. 2023. https://www.doh.gov.ae/en/resources/standards (Accessed: 8 August 2025).

- Abu Dhabi Department of Health (DoH). DOH/GDL/RCT/V1/2024. Guidelines for Clinical & Translational Research in Genomics. Feb. 2024. https://www.doh.gov.ae/en/resources/guidelines (Accessed: 8 August 2025).

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Model Plans and Programs for the OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens and Hazard Communications Standards. https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/publications/osha3186.pdf.

- Environmental Health & Engineering. Guide: BSL-2+: A Guide to Safe Implementation in the Research Environment. https://eheinc.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/BSL2-Research-Env-Guide_3rd-Edition.pdf.

- Duane EG. A practical guide to implementing a BSL-2+ biosafety program in a research laboratory. Applied Biosafety 2013;18:30–6. www.liebertpub.com (Accessed 8 August 2025).

- Frank AM, Braun AH, Scheib L, Agarwal S, Schneider IC, Fusil F, Perian S, Sahin U, Thalheimer FB, Verhoeyen E, Buchholz CJ. Combining T-cell-specific activation and in vivo gene delivery through CD3-targeted lentiviral vectors. Blood Adv. 2020 Nov 24;4(22):5702-5715.

- Ahmed, S.O., El Fakih, R., Kharfan-Dabaja, M.A., Syed, F., Mufti, G., Chabannon, C., Rondelli, D., Mohty, M., Al Ahmari, A.A., Gauthier, J. and Ruella, M., 2025. Setting up a Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy Program: A Framework for Delivery from the Worldwide Network for Blood & Marrow Transplantation. Transplantation and Cellular Therapy, Official Publication of the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for HIV post-exposure prophylaxis [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. Providing PEP. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK606993/.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health. NIH Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant or Synthetic Nucleic Acid Molecules. April 2024. (NIH Guidelines) (accessed August 8, 2025).

- Barrett DM, Zhao Y, Liu X, Jiang S, Carpenito C, Kalos M, Carroll RG, June CH, Grupp SA. Treatment of advanced leukemia in mice with mRNA engineered T cells. Hum Gene Ther. 2011 Dec;22(12):1575-86. [CrossRef]

- Balke-Want H, Keerthi V, Cadinanos-Garai A, Fowler C, Gkitsas N, Brown AK, Tunuguntla R, Abou-El-Enein M, Feldman SA. Non-viral chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells going viral. Immunooncol Technol. 2023 Mar 9;18:100375. [CrossRef]

- Moretti A, Ponzo M, Nicolette CA, Tcherepanova IY, Biondi A, Magnani CF. The Past, Present, and Future of Non-Viral CAR T Cells. Front Immunol. 2022 Jun 9;13:867013. [CrossRef]

- Rafiq S, Hackett CS, Brentjens RJ. Engineering strategies to overcome the current roadblocks in CAR T cell therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020 Mar;17(3):147-167. [CrossRef]

- Michels A, Ho N, Buchholz CJ. Precision medicine: In vivo CAR therapy as a showcase for receptor-targeted vector platforms. Mol Ther. 2022 Jul 6;30(7):2401-2415. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Hu Y, Mei H. Advances in CAR-Engineered Immune Cell Generation: Engineering Approaches and Sourcing Strategies. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2023 Dec;10(35):e2303215. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).