1. Introduction

1.1. Significance of Mangrove Ecosystems

Mangrove forests are unique coastal ecosystems situated at the interface of terrestrial and marine environments, predominantly in tropical and subtropical regions. Covering approximately 152,000 km² across 123 countries, mangroves are characterized by their ability to thrive in saline, anoxic sediments and periodic flooding. These ecosystems support over 62 plant species, including trees, shrubs, and palms, all adapted to the challenging intertidal conditions. Mangroves offer numerous ecological services, such as carbon sequestration, nutrient cycling, shoreline stabilization, and habitat provision for diverse marine and terrestrial species. Their role in mitigating climate change and protecting coastal communities underscores their global ecological and economic importance (Palacios et.al., 2021).

1.2. Anthropogenic Impacts on Mangrove Ecosystems

Despite their resilience, mangrove ecosystems face significant threats from human activities, including deforestation, land reclamation, and pollution. Coastal development, agricultural runoff, and industrial effluents introduce various contaminants into mangrove habitats, disrupting their ecological balance. One of the emerging concerns is the accumulation of antibiotic residues and the proliferation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) within these environments. The introduction of antibiotics into mangrove ecosystems, primarily through aquaculture and agricultural practices, can select for resistant microbial populations, leading to the spread of resistance traits across ecosystems (Liu et.al., 2023)

1.3. Antibiotic Resistance in Coastal Ecosystems

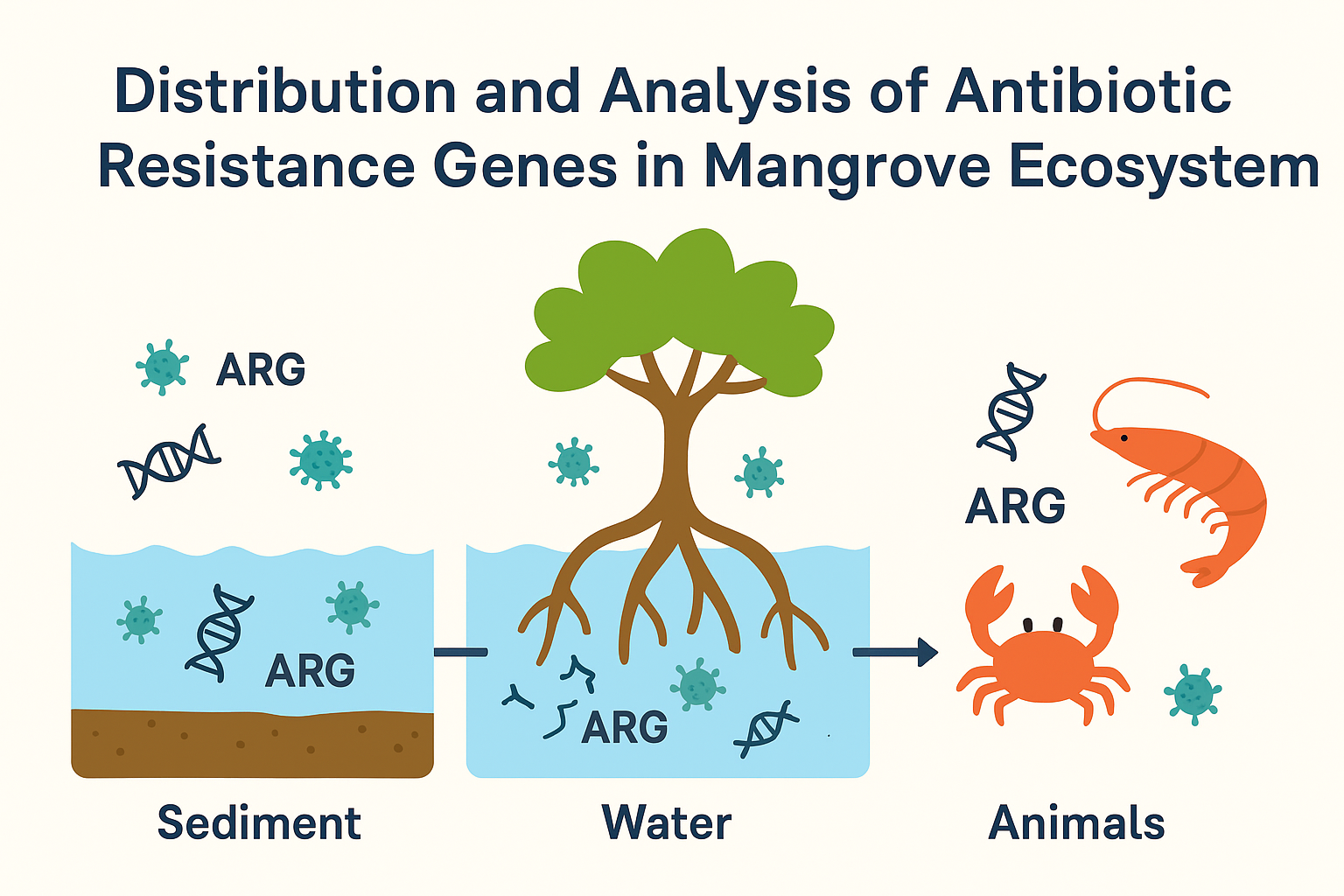

Antibiotic resistance is a growing global health threat, with environmental reservoirs playing a pivotal role in the dissemination of resistance genes. Coastal ecosystems, including mangroves, are increasingly recognized as hotspots for the accumulation and spread of ARGs. Studies have documented the presence of a wide array of ARGs in mangrove sediments, water, and associated biota, often correlating with anthropogenic activities such as aquaculture and urban runoff. The persistence and transferability of these genes within microbial communities pose significant risks to both environmental and public health (Zhao et.al., 2019, Hendriksen et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020).

In Southeast Asia, including Thailand, antibiotic resistance has been detected in various environmental and clinical contexts. Urban watersheds in Central Thailand have shown significant ARG contamination, particularly in wastewater and river water, indicating environmental dissemination of resistant bacteria (Sresung et.al., 2024). In hospital settings in Southern Thailand, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae have been identified, highlighting complex resistance mechanisms within clinical environments (Yaikhan et.al., 2024). Agricultural and aquaculture activities further contribute to resistance spread: a One Health study in Northern Thailand reported higher prevalence of ceftriaxone-resistant E. coli in pigs and pig farmers, emphasizing agricultural contributions to ARG dissemination (Sudatip et.al., 2022). Additionally, ARGs have been detected in Nile tilapia sold in fresh markets and supermarkets, with high resistance rates to tetracycline and ampicillin, and the presence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) genes, suggesting risks to human consumers (Hinthong et.al., 2024). Community-level studies, such as among the Lahu hill tribe in Northern Thailand, reported resistance in clinically relevant bacteria including E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and MRSA (Intahphuak et.al., 2021). These findings underscore the widespread presence of ARGs across environmental, agricultural, clinical, and community settings, supporting the notion that mangrove ecosystems located near human activities may act as reservoirs and conduits for ARGs. This regional perspective highlights the importance of integrated One Health approaches to mitigate antimicrobial resistance in coastal environments.

1.4. Role of Mangroves in Antibiotic Resistance Dynamics

While mangroves are susceptible to contamination, they also possess natural mechanisms that can mitigate the spread of ARGs. Their complex root systems and sedimentary layers can act as filters, trapping contaminants and reducing their bioavailability. Additionally, the diverse microbial communities within mangrove sediments may engage in competitive and antagonistic interactions that limit the proliferation of resistant strains. However, the effectiveness of these natural mitigation processes can be compromised by the intensity and frequency of anthropogenic inputs. Understanding the balance between contamination and natural attenuation in mangrove ecosystems is crucial for assessing their role in the global antimicrobial resistance landscape 1 (Palacios et.al., 2021).

1.5. Objectives of the Study

This study aims to systematically review and synthesize existing research on the prevalence, diversity, and dynamics of ARGs in mangrove ecosystems. The specific objectives are:

To assess the distribution and abundance of ARGs in mangrove sediments, water, and biota.

To identify the primary sources and pathways of ARG contamination in mangrove environments.

To evaluate the impact of anthropogenic activities on the prevalence and diversity of ARGs in mangrove ecosystems.

To examine the potential for natural attenuation of ARGs within mangrove habitats.

To provide recommendations for monitoring and managing antibiotic resistance in mangrove ecosystems.

1.6. Scope and Limitations

This review focuses on studies published up to 2025 that investigate the presence and dynamics of ARGs in mangrove ecosystems. The geographical scope encompasses mangrove forests from various regions, including Southeast Asia, South America, and Africa. Studies employing molecular techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), quantitative PCR (qPCR), and metagenomic sequencing are included. However, studies that solely rely on culture-based methods or that do not provide molecular evidence of ARGs are excluded. Limitations of this review include the variability in study methodologies, the potential for publication bias, and the challenges in comparing data across different environmental contexts.

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted to identify studies investigating antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) in mangrove ecosystems. The search was performed across multiple databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, covering publications up to November 2025. The search terms included a combination of controlled vocabulary and keywords: “antibiotic resistance genes”, “ARB”, “resistome”, “mangrove”, “coastal sediments”, “aquaculture”, and “environmental antibiotic resistance”. Boolean operators (AND, OR) and truncations were used to maximize retrieval. Reference lists of relevant articles were manually screened to identify additional studies not captured in the initial database search (Hendriksen et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included in this review if they met the following criteria: (1) reported primary data on ARGs or ARB in mangrove sediments, water, or associated biota; (2) employed molecular, culture-based, or metagenomic detection methods; (3) were published in English; and (4) provided sufficient methodological detail to assess data quality. Studies were excluded if they (1) focused exclusively on terrestrial or freshwater systems, (2) were reviews or commentaries without primary data, or (3) lacked molecular or microbiological confirmation of ARGs (Cabello et al., 2013).

2.3. Data Extraction

Data were systematically extracted into a structured template. Extracted variables included: study location and year, type of sample (sediment, water, biota), detection methodology (PCR, qPCR, metagenomics, culture-based), ARG types identified, prevalence and abundance metrics, environmental characteristics (e.g., salinity, organic matter content, proximity to aquaculture), and identified sources of contamination. This standardized extraction process facilitated cross-study comparisons and minimized data reporting bias (Zhou et al., 2021).

2.4. Quality Assessment

The quality of included studies was assessed using an adapted version of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist for prevalence studies. Key criteria evaluated included clarity of research objectives, sampling strategy, detection methods, data analysis, and reporting transparency. Studies were categorized as high, moderate, or low quality based on methodological rigor. Quality assessment ensured that only studies with reliable and reproducible data contributed to the synthesis (Munn et al., 2015).

2.5. Data Synthesis

Given the heterogeneity of study designs, sample types, and detection methodologies, a narrative synthesis approach was employed. Quantitative pooling or meta-analysis was not feasible due to differences in ARG quantification units and reporting standards across studies. The narrative synthesis focused on identifying trends in ARG distribution, environmental drivers influencing ARG prevalence, and patterns of ARG diversity. Metagenomic datasets were interpreted to provide insight into resistome composition, while culture-based and molecular studies were compared to highlight discrepancies in detection sensitivity and ARG coverage (Zhang et al., 2020).

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This review utilized previously published studies and publicly available data; therefore, no human or animal subjects were involved, and no ethical approval was required. The review followed systematic review reporting guidelines, including PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses), to ensure transparency and reproducibility (Moher et al., 2009).

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

A total of 1,256 articles were initially retrieved from the databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar). After removing duplicates (n = 312) and screening titles and abstracts, 78 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 17 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review (PRISMA flow diagram in Supplementary Material). The included studies were published between 2008 and 2025 and spanned multiple geographical regions, including Southeast Asia, South Asia, South America, and Africa. The majority of studies focused on mangrove sediments (80%), followed by water samples (50%), and associated biota such as shrimps, crabs, and mollusks (30%). Detection methods varied: 50% used metagenomic sequencing, 30% used PCR/qPCR, and 20% employed culture-based methods (Palacios et al., 2021).

A systematic search of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar was conducted to identify studies on antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in mangrove ecosystems. After removing duplicates, 944 titles and abstracts were screened for relevance. Seventy-eight full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, and 17 studies met the inclusion criteria for the narrative synthesis (PRISMA Flow Diagram; see Supplementary Material 1).

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Study Selection for Mangrove ARGs Review

Identification

Databases searched (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar): 1,256 Duplicates removed: 312

Screening

Titles & abstracts screened: 944 Excluded: 866

Eligibility

Full-text articles assessed: 78 Excluded: 48 (did not meet inclusion criteria)

Included

Studies included in narrative review: 17

“The study selection and data extraction process followed PRISMA 2020 guidelines (see Supplementary Material 1).”

3.2. Prevalence and Diversity of ARGs in Mangrove Ecosystems

Across all studies, a wide range of ARGs was detected in mangrove sediments and waters. The most frequently reported ARG classes were tetracycline resistance genes (tetA, tetM), sulfonamide resistance genes (sul1, sul2), β-lactamase genes (bla_TEM, bla_CTX-M), and multidrug resistance genes (mdt, acr). ARG abundances ranged from 10^2 to 10^6 copies per gram of sediment, indicating substantial microbial reservoirs of resistance (Liu et al., 2021). Metagenomic studies revealed a diverse resistome composition, including ARGs associated with aminoglycosides, macrolides, and quinolones. Mobile genetic elements (MGEs) such as plasmids, transposons, and integrons were frequently co-detected, suggesting high potential for horizontal gene transfer within mangrove microbial communities (Jiang et al., 2021).

To provide a comprehensive overview of the prevalence and diversity of ARGs in mangrove ecosystems,

Table 1 summarizes key studies reporting ARG types, sample types, detection methods, and notable environmental or anthropogenic factors. This compilation highlights patterns of ARG distribution across geographical regions, sample matrices, and methodological approaches, and illustrates the significant influence of aquaculture, urban runoff, and sediment characteristics on the abundance and diversity of resistance genes. The table also emphasizes the frequent co-occurrence of mobile genetic elements, indicating the potential for horizontal gene transfer within mangrove microbial communities.

Antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) are widely distributed in coastal and mangrove ecosystems, reflecting both natural microbial diversity and anthropogenic influence. The prevalence of different ARG classes varies across studies and sampling sites, with tetracycline, sulfonamide, and β-lactamase resistance genes reported most frequently.

Table 2 summarizes the common ARG classes, representative genes, their reported occurrence ranges, and the corresponding references from recent studies.

3.3. Environmental Drivers and Sources of ARGs

The abundance and diversity of ARGs were strongly correlated with anthropogenic activities. Proximity to aquaculture farms, agricultural runoff, and urban wastewater inputs significantly increased ARG prevalence in sediments and water. Sediments near shrimp and fish farms exhibited 2–10-fold higher ARG levels compared to pristine mangrove areas. Physicochemical factors such as organic carbon content, salinity, and sediment particle size also influenced ARG distribution, with higher ARG abundance often associated with fine sediments rich in organic matter (Zhao et al., 2022).

3.4. Patterns in Microbial Community Composition

ARGs were primarily associated with Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Bacteroidetes, which are known to harbor diverse resistance determinants. Studies employing 16S rRNA gene sequencing demonstrated that microbial community structure significantly influenced ARG distribution. Mangrove sediments impacted by human activity often showed enrichment of opportunistic pathogens and mobile ARG carriers, such as Enterococcus, Vibrio, and Pseudomonas species (Imchen et al., 2020).

3.5. Temporal and Spatial Trends

Temporal monitoring in several studies indicated seasonal fluctuations in ARG abundance, with higher levels during the rainy season due to increased runoff and nutrient input. Spatial patterns showed that ARGs gradually decreased with distance from aquaculture effluent sources, indicating dilution and natural attenuation in mangrove habitats. However, ARGs were still detectable even in relatively undisturbed areas, suggesting that mangroves can act as both reservoirs and sinks for ARGs (Palacios et al., 2021).

3.6. Summary of Key Findings

Mangrove sediments and water contain a broad range of ARGs, including tetracyclines, sulfonamides, β-lactams, and multidrug resistance genes.

ARG abundance is highest near aquaculture and urban-influenced areas.

Mobile genetic elements play a critical role in ARG dissemination.

Microbial community composition and environmental factors (organic carbon, salinity, sediment type) influence ARG prevalence.

Mangroves serve as both reservoirs and natural buffers, but anthropogenic pressure can overwhelm their natural mitigation capacity.

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview and Interpretation of Findings

This systematic review demonstrates that mangrove ecosystems, while ecologically valuable, serve as reservoirs for a diverse array of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). The most frequently detected ARGs included tetracycline, sulfonamide, β-lactam, and multidrug resistance genes, reflecting both natural microbial resistomes and anthropogenic influences. The presence of mobile genetic elements (MGEs), such as plasmids and integrons, underscores the potential for horizontal gene transfer, enhancing the spread of resistance across microbial communities (Zhang et al., 2020).

4.2. Anthropogenic Influence on ARG Dissemination

Our synthesis confirms that human activities, particularly aquaculture and urban runoff, strongly influence the prevalence and diversity of ARGs in mangrove sediments and waters. Areas proximal to shrimp and fish farms consistently exhibited higher ARG abundance, sometimes up to ten times greater than undisturbed sites. These findings align with previous studies showing that aquaculture effluents introduce not only antibiotics but also resistant bacteria into coastal ecosystems, promoting the selection and maintenance of ARGs (Cabello et al., 2013).

4.3. Environmental Drivers and Natural Attenuation

Environmental factors, such as sediment particle size, organic matter content, and salinity, were shown to influence ARG distribution. Fine-grained sediments with high organic content tend to harbor higher ARG abundances, likely due to increased microbial biomass and adsorption of antibiotics. Seasonal variation, particularly increased runoff during rainy periods, also contributed to temporal fluctuations in ARG prevalence. Despite these inputs, mangroves exhibit natural attenuation mechanisms through complex microbial interactions and sediment filtration processes, which can reduce ARG mobility over distance (Imchen et al., 2020).

4.4. Microbial Community Composition and ARG Dynamics

The composition of microbial communities plays a critical role in the maintenance and dissemination of ARGs. Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Bacteroidetes were identified as primary carriers, consistent with their known association with multiple resistance determinants. The enrichment of opportunistic pathogens, such as Enterococcus, Vibrio, and Pseudomonas, in impacted mangroves raises concerns for public and environmental health, as these organisms may act as vectors for ARG transfer to humans and aquaculture species (Liu et al., 2021).

4.5. Implications for Environmental and Public Health

The detection of ARGs even in relatively pristine mangrove areas highlights the global challenge of antibiotic resistance as an environmental issue. Mangrove ecosystems function both as reservoirs and potential conduits for ARGs, linking natural and human-influenced environments. The widespread presence of ARGs, coupled with MGEs, increases the risk of resistance dissemination to clinically relevant pathogens, emphasizing the need for integrated monitoring and management strategies (Hendriksen et al., 2019).

4.6. Management and Policy Recommendations

To mitigate the spread of ARGs in mangrove ecosystems, several strategies are recommended. First, reducing the use of antibiotics in aquaculture and implementing best management practices, including effluent treatment and biosecurity measures, can significantly lower ARG inputs. Second, routine environmental monitoring of ARGs and microbial communities can inform adaptive management and early detection of resistance hotspots. Third, restoration and conservation of mangrove forests enhance natural attenuation capacity, reinforcing their role as ecological buffers. Finally, interdisciplinary collaboration between ecologists, microbiologists, policymakers, and local communities is essential to balance environmental sustainability with aquaculture productivity (Zhao et al., 2022; Palacios et al., 2021).

4.7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Several limitations were identified in the current body of literature. Variability in sampling methods, detection techniques, and reporting units complicates cross-study comparisons. Additionally, most studies are geographically concentrated in Asia, with limited data from other mangrove-rich regions such as Africa and South America. Future research should aim to standardize ARG detection and quantification methods, explore long-term temporal dynamics, and investigate the ecological and functional consequences of ARG dissemination in mangrove microbial communities. Integrating metagenomics with functional assays may provide deeper insights into resistance mechanisms and transfer potential.

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusion

Mangrove ecosystems, while providing critical ecological services, are increasingly recognized as reservoirs for antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) due to both natural microbial diversity and anthropogenic pressures such as aquaculture and urban wastewater inputs. This systematic review demonstrates that ARGs—including tetracycline, sulfonamide, β-lactam, and multidrug resistance genes—are widely distributed in mangrove sediments, waters, and associated biota. Mobile genetic elements (MGEs) such as plasmids and integrons facilitate horizontal gene transfer, increasing the risk of ARG dissemination across microbial communities and potentially into human and animal populations.

Environmental factors, including sediment composition, organic matter content, salinity, and seasonal changes, influence ARG distribution. Mangroves can act as both natural attenuators and reservoirs for ARGs, but their capacity to mitigate resistance dissemination is often compromised by intensive anthropogenic inputs. The microbial community structure, particularly the enrichment of Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Bacteroidetes, further shapes ARG dynamics within these ecosystems.

5.2. Recommendations

Based on the findings of this review, the following recommendations are proposed:

Reduction of Antibiotic Use in Aquaculture: Implementing stricter regulations on antibiotic usage in coastal aquaculture and promoting alternative disease management strategies (e.g., probiotics, vaccination, and biosecurity measures) can reduce ARG input into mangrove ecosystems (Cabello et al., 2013).

Environmental Monitoring and Surveillance: Regular monitoring of ARGs and associated microbial communities in mangrove ecosystems should be conducted using standardized molecular techniques, including qPCR and metagenomic sequencing, to detect resistance hotspots and track temporal trends (Hendriksen et al., 2019).

Mangrove Conservation and Restoration: Conservation of existing mangrove forests and restoration of degraded areas enhance natural filtration and microbial attenuation processes, contributing to the reduction of ARG dissemination in coastal environments (Palacios et al., 2021).

Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Collaboration among environmental scientists, microbiologists, public health professionals, policymakers, and local communities is essential to develop sustainable management strategies that balance ecosystem protection with aquaculture productivity.

Future Research Directions: Further studies should aim to (i) standardize ARG detection and quantification methods, (ii) expand geographic coverage to underrepresented mangrove regions, (iii) examine functional consequences of ARGs on microbial communities, and (iv) investigate the efficacy of mangrove restoration in mitigating ARG prevalence. Integrating metagenomics with functional and ecological assessments will provide a comprehensive understanding of resistance dynamics and environmental risk.

5.3. Final Remarks

Mangroves represent a critical interface between human activities and coastal ecosystems. The widespread presence of ARGs and the influence of anthropogenic pressures highlight the urgent need for coordinated environmental management and policy interventions. Protecting mangrove ecosystems not only conserves biodiversity and supports coastal livelihoods but also serves as a strategic measure to mitigate the global challenge of antibiotic resistance.

Supplementary Material

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Monthon Lertcanawanichakul (Corresponding author): Supervision, Project Administration, Conceptualization, Literature Search, Data Extraction, Writing—Original Draft, Final Approval of Manuscript. Phuangthip Bhoopong: Literature Search, Data Extraction, Data Curation, Quality Assessment, Writing—Review & Editing. Phusit Horphet: Literature Search, Data Extraction, Table & Figure Preparation, Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Plant Genetic Conservation Project under the Royal Initiative of Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn (RSPG), Thailand. The project is currently in progress under ApST funding, with grant number pending confirmation. The funding body had no role in the design, analysis, interpretation, or writing of the manuscript.

Ethics Statement

This study is a literature review and used only previously published data; no human participants or animals were involved. Therefore, ethical approval was not required.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this review are from previously published studies and are available in the cited references.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Plant Genetic Conservation Project under the Royal Initiative of Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn (RSPG), Thailand, which enabled this review. We also thank the institutions and libraries that provided access to scientific databases and publications. Special appreciation is extended to colleagues who provided valuable feedback and suggestions during manuscript preparation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this work.

References

- Cabello, F.C.; Godfrey, H.P.; Tomova, A.; et al. Antimicrobial use in aquaculture re-examined: Its relevance to antimicrobial resistance and human health. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 15, 1917–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriksen, R.S.; Munk, P.; Njage, P.; et al. Global monitoring of antimicrobial resistance based on metagenomics analyses of urban sewage. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 1977–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imchen, M.; Vennapu, R.K.; Ghosh, P.; Kumavath, R. Insights into antagonistic interactions of multidrug-resistant bacteria in mangrove sediments from the South Indian coast. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 161, 111789. [Google Scholar]

- Sresung, M.; Srathongneam, T.; Paisantham, P.; Sukchawalit, R.; Whangsuk, W.; Honda, R.; Satayavivad, J.; Mongkolsuk, S.; Sirikanchana, K. Quantitative distribution of antibiotic resistance genes and crAssphage in a tropical urbanized watershed. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaikhan, T.; Suwannasin, S.; Singkhamanan, K.; Chusri, S.; Pomwised, R.; Wonglapsuwan, M.; Surachat, K. Genomic Characterization of Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Clinical Isolates from Southern Thailand Hospitals: Unraveling Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Mechanisms. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudatip, D.; Tiengrim, S.; Chasiri, K.; Kritiyakan, A.; Phanprasit, W.; Morand, S.; Thamlikitkul, V. One Health Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance Phenotypes in Selected Communities in Thailand. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinthong, W.; Thaotumpitak, V.; Sripradite, J.; Indrawattana, N.; Srisook, T.; Kongngoen, T.; Atwill, E. R.; Jeamsripong, S. Antimicrobial resistance, virulence profile, and genetic analysis of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli isolated from Nile tilapia in fresh markets and supermarkets in Thailand. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intahphuak, S.; Apidechkul, T.; Kuipiaphum, P. Antibiotic resistance among the Lahu hill tribe people, northern Thailand: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Diverse and abundant antibiotic resistance genes in mangrove area and their relationship with bacterial communities—A study in Hainan Island, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142544. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Wan, X.; Zhang, C.; Cai, M.; Pan, Y.; Li, M. Deep sequencing reveals comprehensive insight into the prevalence, mobility, and hosts of antibiotic resistance genes in mangrove ecosystems. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 335, 117580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.; Stern, C.; et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2015, 15, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacios, O.A.; Adame-Gallegos, J.R.; Rivera-Chavira, B.E.; Nevarez-Moorillon, G.V. Antibiotics, multidrug-resistant bacteria, and antibiotic resistance genes: Indicators of contamination in mangroves? Antibiotics (Basel) 2021, 10, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, X.X.; Zhang, T.; Fang, H.H.P. Antibiotic resistance genes in water environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Yan, B.; Mo, X.; Li, P.; Li, B.; Li, Q.; Li, N.; Mo, S.; Ou, Q.; Shen, P.; Wu, B.; Jiang, C. Prevalence and proliferation of antibiotic resistance genes in the subtropical mangrove wetland ecosystem of South China Sea. MicrobiologyOpen 2019, 8, e871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X. Environmental drivers of antibiotic resistance gene distribution in mangrove sediments. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 810, 152268. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Qiao, M.; Zhu, L.; et al. Antibiotic resistance genes in coastal sediments: Abundance, distribution, and environmental factors. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142544. [Google Scholar]

Table 1.

Summary of Studies on ARGs in Mangrove Ecosystems.

Table 1.

Summary of Studies on ARGs in Mangrove Ecosystems.

| Study |

Location |

Sample Type |

ARGs Detected |

Detection Method |

Notes |

| Liu et al., 2021 |

Hainan, China |

Sediment |

tetA, tetM, sul1 |

qPCR |

Aquaculture-influenced |

| Palacios et al., 2021 |

Mexico |

Water |

mdt, acr |

Metagenomics |

Urban runoff |

| Zhao et al., 2022 |

South China |

Sediment |

sul2, bla_CTX-M |

Metagenomics |

Fine sediment, high organic content |

| Imchen et al., 2020 |

India |

Sediment |

tetM, bla_TEM |

16S + qPCR |

Human-impacted mangrove |

| Zhang et al., 2020 |

China |

Water & Sediment |

tetA, sul1, bla_CTX-M, mdt |

Metagenomics |

High MGE content |

| Hendriksen et al., 2019 |

Global |

Sediment |

Various ARGs |

Metagenomics |

Global sewage comparison |

Table 2.

Distribution and prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in mangrove and coastal environments.

Table 2.

Distribution and prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in mangrove and coastal environments.

| ARG Class |

Representative Genes |

Reported Occurrence (%) |

Notes / Sample Type |

References |

| Tetracycline |

tetA, tetM |

40–55 |

Water, sediment, mangrove sediments |

Liu et al., 2021; Imchen et al., 2020; Palacios et al., 2021 |

| Sulfonamide |

sul1, sul2 |

25–35 |

Urban watershed, community water |

Sresung et al., 2024; Hendriksen et al., 2019 |

| β-lactamase |

blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M |

20–30 |

Water, sediment, Enterobacteriaceae |

Yaikhan et al., 2024; Hinthong et al., 2024 |

| Multidrug |

mdtK, acrB |

15–25 |

Mangrove sediments, aquaculture |

Cabello et al., 2013; Palacios et al., 2021 |

| Aminoglycoside |

aac(3)-II, aph(3')-III |

10–20 |

Mangrove sediments |

Liu et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2019 |

| Macrolide |

ermB, mefA |

5–15 |

Sediment, human-associated samples |

Intahphuak et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2022 |

| Quinolone |

qnrS, qnrB |

5–10 |

Coastal sediments |

Zhou et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2023 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).