1. Introduction

The Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most critical threats to global public health, being associated with high morbidity and mortality rates [

1,

2]. It is estimated to cause around 700,000 deaths annually, a number that could rise to 10 million by the year 2050 in the absence of effective interventions [

3]. This situation not only compromises the efficacy of antibacterial treatments but also generates a considerable economic impact by prolonging hospital stays and increasing healthcare costs [

4,

5]. Although antimicrobial-resistant bacteria (ARB) and antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) are naturally present in microbial ecosystems, most of them are not clinically relevant [

6,

7,

8]. However, human activity has favored the introduction and dissemination of clinically important ARB and ARGs in environments where they were previously absent, turning them into true emerging contaminants [

9,

10]. This dissemination is exacerbated by the massive release of antibiotic residues (AR), which exert selective pressure that promotes the persistence and horizontal transfer of these elements [

11,

12]. Thus, clinically relevant AR, ARB, and ARGs converge as an environmental threat, as they facilitate the evolution of resistance and its spread among environmental and pathogenic microbial communities, significantly altering the microbial ecology of affected ecosystems [

13,

14,

15]

On the other hand, aquatic environments have been identified as key reservoirs of AMR, as they receive contaminants from various sources such as urban wastewater, agricultural runoff, and industrial discharges [

13,

14]. In these systems, genetic interactions occur between environmental and human-associated pathogenic bacteria, contributing to the emergence and transfer of resistance mechanisms [

16,

17]. Several studies have demonstrated the persistence of ARGs and ARB in water bodies used for human consumption, irrigation, and recreation, increasing the risk of direct and indirect exposure to multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens [

13]. In this context, the Aconcagua River—located in the Mediterranean region of central Chile—represents a model system for the study of AMR in aquatic environments. Its flow depends mainly on seasonal snowmelt from the Andes Mountains, and its basin is subject to multiple anthropogenic pressures. Intensive agricultural activity, including the use of fertilizers and pesticides, exerts selective pressure on bacterial communities, while mining activities contribute with tailings rich in heavy metals, which can co-select for antibiotic resistance determinants [

18,

19,

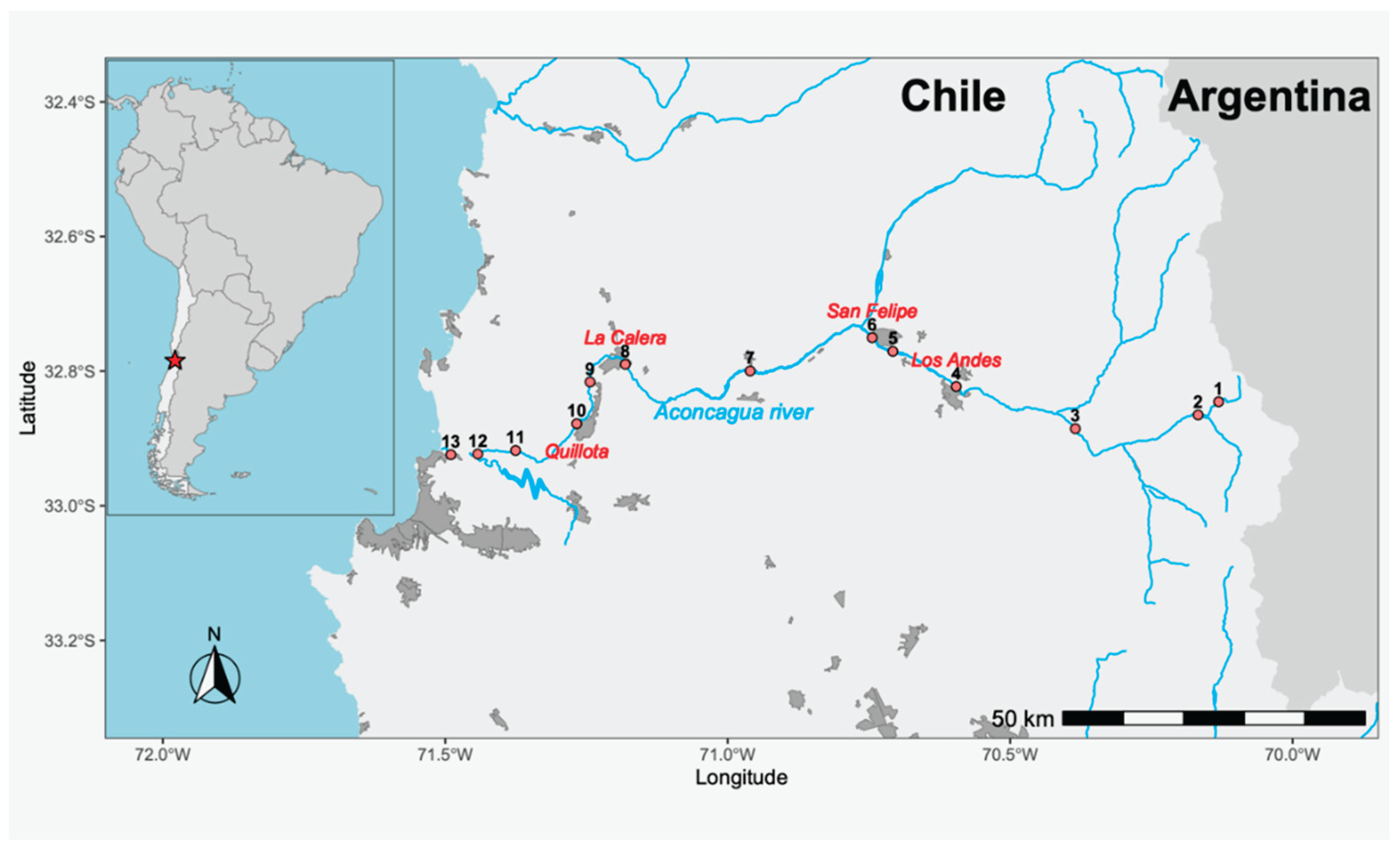

20]. This is further compounded by urban influence, as at least four cities with populations exceeding 50,000 inhabitants (including Quillota, San Felipe, Los Andes and La Calera) discharge their treated wastewater into the river. These treatment plants comply solely with current Chilean regulations, which do not include microbiological criteria—that is, they do not establish a maximum allowable concentration of microorganisms in the treated water to validate the efficacy of the treatment—thus permitting the potential release of ARB and ARGs into the environment. Considering that more than 370,000 people influence the water quality of the Aconcagua River directly or indirectly, and that this aquatic system concentrates multiple factors relevant to the evolution and dissemination of AMR, its study offers a unique opportunity. Moreover, its accessibility and the possibility of conducting comprehensive sampling in a single day allow for the minimization of temporal biases. In this study, we propose the isolation and characterization of ARB present in the Aconcagua River, with the aim of understanding their diversity and the impact of human activities on the spread of AMR in natural environments.

2. Results

2.1. Isolation and Identification of Bacterial Isolates

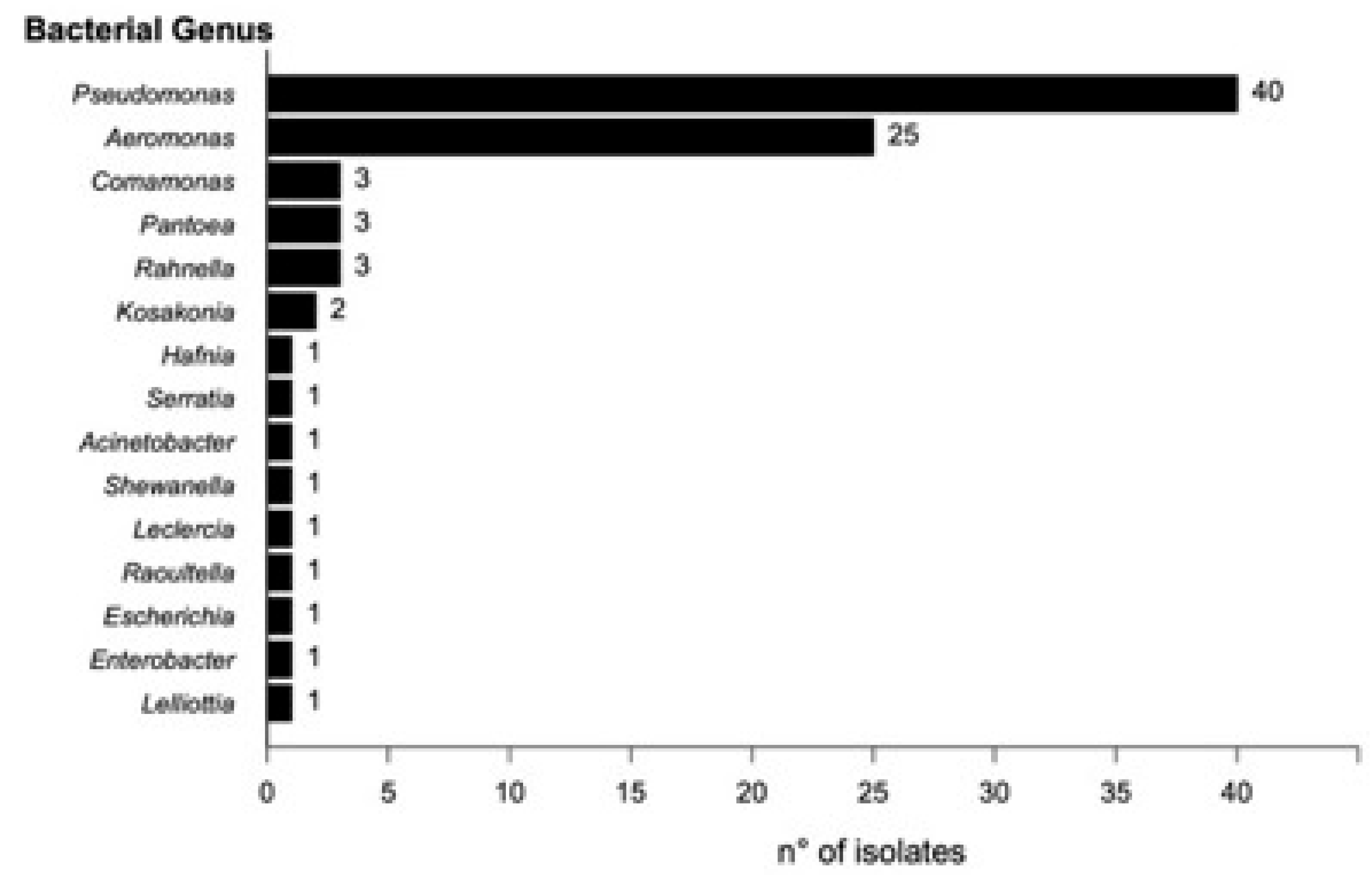

A total of 104 bacterial morphotypes were identified and isolated from the collected samples. Of these, 83 were recovered from control media (MacConkey without antibiotics), and 24 from media supplemented with ceftazidime (CAZ). No growth was observed on the plates supplemented with ciprofloxacin (CIP). Taxonomic identification using MALDI-TOF enabled the identification of 80 isolates at the species level (Score ≥ 2.000) and five at the genus level (Score 1.999–1.700). 19 isolates could not be identified by MALDI-TOF. The predominant genus was Pseudomonas (40 isolates), followed by Aeromonas (25), Comamonas (3), Rahnella (3), Pantoea (3), and Kosakonia (2). The remaining genera were each represented by a single isolate (

Figure 1).

2.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profile

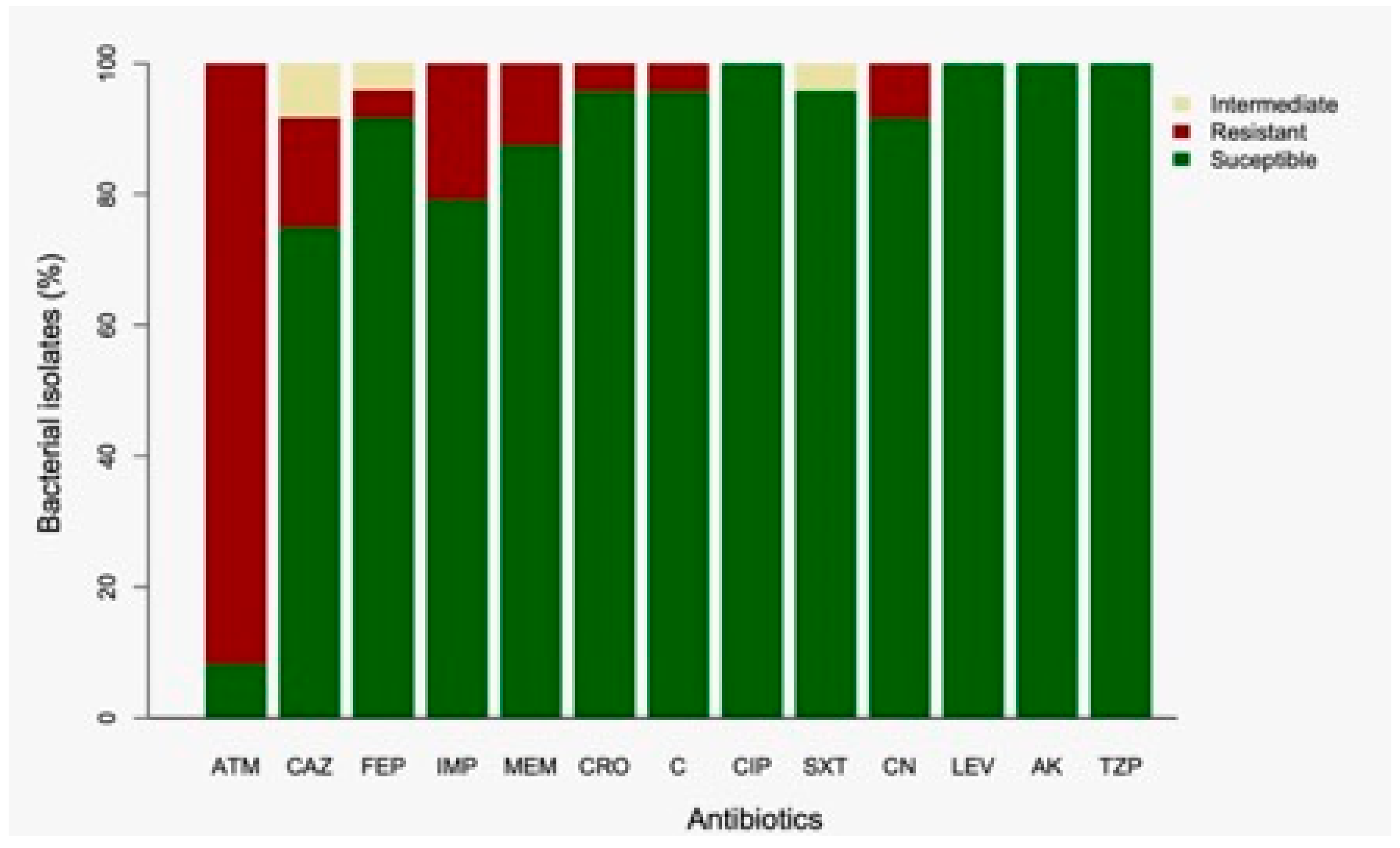

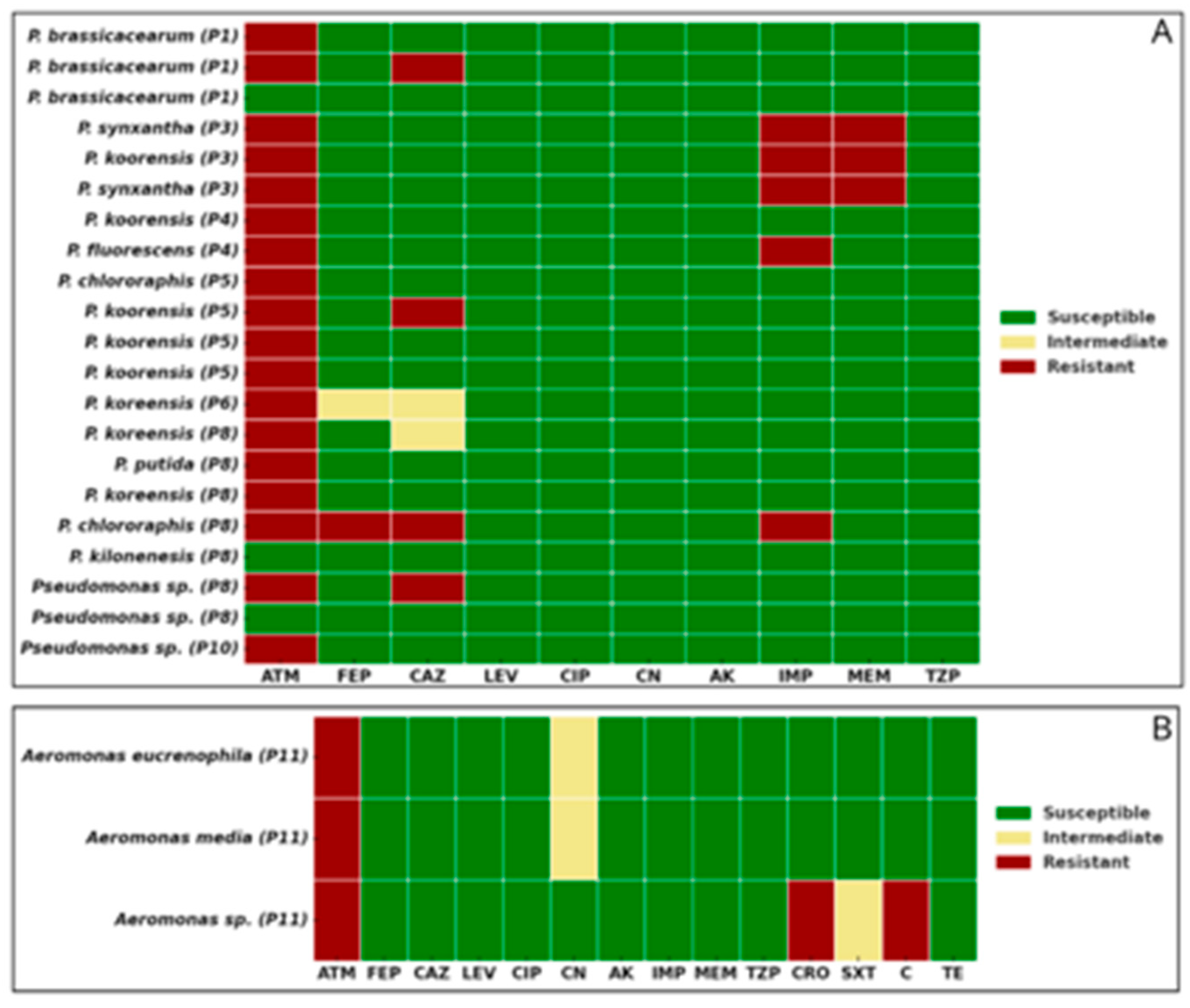

Analysis of the susceptibility profiles revealed that 87.5% (21/24) of the isolates from CAZ-supplemented media were resistant to aztreonam (ATM). Additionally, 25% (6/24) were non-susceptible to ceftazidime (CAZ), including four resistant and two intermediately susceptible isolates (Figure 2). For cefepime (FEP), 8.3% (2/24) of isolates were non-susceptible—one resistant and one intermediate. Resistance to imipenem (IMP) and meropenem (MEM) was observed in 20.8% (5/24) and 12.5% (3/24) of isolates, respectively. Notably, three isolates showed resistance to both carbapenems. Resistance to ceftriaxone (CRO) and chloramphenicol (C) was detected in 4.2% (1/24) of isolates. Intermediate susceptibility to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT) was also observed in 4.2% (1/24) of isolates. Gentamicin (CN) resistance was found in 8.3% (2/24) of isolates, both of which were also resistant to carbapenems. All isolates remained susceptible to ciprofloxacin (CIP), levofloxacin (LEV), amikacin (AK), and piperacillin/tazobactam (TZP). None of the isolates met the criteria for classification as multidrug-resistant (MDR), extensively drug-resistant (XDR), or pandrug-resistant (PDR) (

Figure 3A and 3B). In terms of geographic distribution, sampling point 8 yielded the highest number of resistant isolates (7/24), followed by point 5 (5/24). Among the five carbapenem-resistant isolates, three—resistant to both IMP and MEM—were recovered from point 3, while the remaining two—resistant only to IMP—were isolated from points 4 and 8.

2.3. Detection of Carbapenemases Production

Among the five isolates that exhibited phenotypic resistance to carbapenems, two tested positive in the Blue-Carba assay, confirming the production of active carbapenemases. Molecular analysis identified both isolates—Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas synxantha—as carriers of the blaVIM gene, which encodes the Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase (VIM). This enzyme is one of the most prevalent carbapenemases in the Pseudomonas genus and represents a serious global public health threat.

3. Discussion

AMR represents a complex global challenge that transcends clinical and veterinary contexts, increasingly impacting environmental health [

21,

22]. In this regard, aquatic ecosystems have been widely recognized as critical environments for the study of AMR, as they act simultaneously as reservoirs and vectors for the dissemination of ARB and ARGs [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. This study characterized ARB isolated from the Aconcagua River, a freshwater system located in central Chile which, due to intensive agricultural, livestock, aquaculture, and mining activities, as well as the discharge of urban wastewater, constitutes a representative model for environmental AMR monitoring. One of the most noteworthy findings was the effectiveness of the MALDI-TOF system in the taxonomic identification of environmental bacteria, enabling species-level assignment of 76.9% of isolates (80/104), including many genera not traditionally associated with human health. This capability highlights the growing utility of this technique for environmental microbiology studies, even though commercial databases remain predominantly enriched with clinically relevant strains [

28]. The accurate identification of environmental bacteria by MALDI-TOF expands the potential for understanding microbial ecology in human-impacted settings [

28].

Another relevant observation was the absence of World Health Organization (WHO)-listed priority pathogens. While this could be interpreted as a favorable indicator from a public health perspective, it may also reflect methodological limitations in recovering certain genera or be influenced by the selective pressure exerted by specific contaminants in the watershed. In contrast, there was a marked predominance of the genus

Pseudomonas, which accounted for 40 of the 85 identified isolates—an observation that aligns with previous reports describing

Pseudomonas as a highly adaptable and prevalent genus in contaminated aquatic environments, capable of tolerating extreme conditions and diverse toxic compounds, including heavy metals and organic pollutants [

29,

30]. The exclusive recovery of

Pseudomonas and

Aeromonas isolates on media supplemented with ceftazidime (CAZ), along with the absence of growth on ciprofloxacin (CIP)-supplemented plates, suggests a differential selective pressure potentially linked to the contaminant profile of the basin. This pattern may reflect the persistence of resistance determinants to third-generation cephalosporins relative to fluoroquinolones, whose resistance mechanisms often impose a high physiological cost [

31,

32,

33]. In fact, 92.5% of isolates recovered on CAZ media exhibited concurrent resistance to aztreonam (ATM), raising additional concerns regarding the role of these genera as reservoirs of clinically relevant ARGs. The detection of carbapenem resistance in five

Pseudomonas isolates—all classified as environmental species—underscores the expansion of critical resistance mechanisms beyond hospital settings. Carbapenems are considered last-resort antibiotics for treating severe infections [

21,

34], and their resistance in non-pathogenic strains signals the possible environmental dissemination of high-priority resistance genes such as bla

VIM. This hypothesis is further supported by the phenotypic confirmation of carbapenemase activity and molecular detection of bla

VIM in two

Pseudomonas isolates, highlighting the role of the river as an active reservoir of resistance determinants with high clinical relevance. While VIM is the most frequently reported carbapenemase in

Pseudomonas aeruginosa [

35,

36,

37,

38], its presence in non-pathogenic members of the genus may facilitate its spread in natural environments.

Geographically, the sampling sites P5 and P8—located immediately downstream of the wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) of Los Andes and Quillota, respectively—showed the highest concentrations of ARB, reinforcing the association between treated effluent discharge and the environmental load of resistant bacteria [

39,

40,

41,

42]. This finding underscores the urgent need to revise Chile’s wastewater treatment standards, which currently lack microbiological criteria, thereby permitting the potential release of ARB and ARGs into natural water bodies.

From a One Health perspective, the findings of this study are of particular concern. The waters of the Aconcagua River are extensively used for agricultural irrigation in one of Chile’s most important horticultural regions. The presence of resistant bacteria and ARGs in these waters poses a tangible risk for the introduction of resistant microorganisms into the food chain, with potential impacts on both human and animal health [

43].

In conclusion, although WHO priority pathogens were not detected, the high prevalence of resistant Pseudomonas, the presence of carbapenem-resistant strains, and the detection of clinically significant carbapenemases such as VIM point to a worrisome environmental health scenario. These findings emphasize the need to establish integrated microbiological surveillance systems and implement public policies aimed at mitigating the environmental dissemination of AMR, particularly in river basins under strong anthropogenic pressure such as the Aconcagua River.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Area and Sampling

The study area corresponds to the Aconcagua River, located in the Valparaíso Region of Chile. The river stretches 177 kilometers, originating in the Andes Mountains (−32.827014, −70.092600) and flowing westward until it empties into the Pacific Ocean at the city of Concón (−32.914798, −71.508738). The river basin covers an area of approximately 7,340 km². The estimated annual net discharge is 429 million m³, with an average flow rate of around 13.6 m³/s. Thirteen sampling points were selected along the course of the river (

Figure 4), and all samples were collected on the same day. At each site, one liter of surface water was collected by submerging a sterile bottle 30 cm below the surface and opening it underwater. The samples were transported under cold chain conditions on the same day to the Molecular Genetics Laboratory at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso.

4.2. Processing and Isolation of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria (ARB)

Each water sample was passed through a 0.22 μm filter. The filters were resuspended in 0.85% saline solution, and serial 1:10 dilutions were prepared from 10⁻¹ to 10⁻⁴. From each dilution, 100 μL were plated onto MacConkey agar plates independently supplemented with either ceftazidime (CAZ) or ciprofloxacin (CIP), both at a final concentration of 2 μg/mL. Cycloheximide was added at a concentration of 50 μg/mL to inhibit fungal growth. A control plate without antibiotics was also included. All plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours. Colonies with distinct morphologies—based on size, color, and shape—were selected from plates showing isolated growth. To ensure the purity of each morphotype, the selected colonies were re-streaked onto tryptic soy agar (TSA) plates. The purified colonies were then preserved in 12% glycerol at -80 °C. Morphotype identification was performed using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry with the Bruker Biotyper® system (Bruker, USA). Isolates with a score value ≥ 2.000 were identified at the species level, while those with scores between 1.700 and 1.999 could only be identified at the genus level. Isolates with score values below 1.700 could not be assigned to any genus [

44,

45].

4.3. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

Antibiotic susceptibility of the isolated bacteria was evaluated using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method, in accordance with Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [

46]. Only isolates that grew on plates supplemented with the antibiotics CAZ and CIP were subjected to susceptibility testing. Antibiotic panels were selected based on genus-specific recommendations: Pseudomonas spp. were tested using agents specified in CLSI M100, 2023 [

46], and Aeromonas spp. according to CLSI M45, 2016 [

47]. The antibiotics tested included ceftazidime (CAZ, 30 μg), cefepime (FEP, 30 μg), ceftriaxone (CRO, 30 μg), aztreonam (ATM, 30 μg), imipenem (IPM, 10 μg), meropenem (MEM, 10 μg), piperacillin/tazobactam (TZP, 100/10 μg), ciprofloxacin (CIP, 5 μg), levofloxacin (LEV, 5 μg), gentamicin (CN, 10 μg), amikacin (AMK, 30 μg), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (SXT, 1.25/23.75 μg), and tetracycline (TE, 30 μg). Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours, and inhibition zones were interpreted according to CLSI breakpoints. Isolates were classified as susceptible (S), intermediate (I), or resistant (R). Where applicable, isolates were further categorized as multidrug-resistant (MDR), extensively drug-resistant (XDR), or pandrug-resistant (PDR) based on standardized international criteria [

48].

4.4. Phenotypic and Genotypic Detection of Carbapenemases

Isolates showing phenotypic resistance to at least one carbapenem were evaluated using the Blue-Carba test to confirm carbapenemase production [

49]. E. coli strains producing VIM, KPC, and NDM were used as positive controls. For isolates testing positive in the phenotypic assay, genomic DNA was extracted from TSB broth cultures incubated for 24 hours using Chelex® 100 resin (Bio-Rad). Detection of the blaVIM, blaKPC, and blaNDM genes was performed via PCR using GoTaq® Green Master Mix (Promega). The specific primers and amplification conditions are detailed in

Table 1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.G., D.L.V. and J.O.P.; methodology, N.G., D.V.L., R.C.L. and J.O.P.; validation, D.L.V. and J.O.P.; formal analysis, N.G., D.L.V., J.M., M.C. and J.O.P.; investigation, N.G., D.L.V. and J.O.P.; resources, J.M. and J.O.P.; data curation, N.G.; writing—original draft preparation, N.G.; writing—review and editing, N.G., D.L.V., J.M., M.C. and J.O.P..; visualization, N.G:, D.L.V, and J.O.P; supervision, J.O.P; project administration, J.O.P.; funding acquisition, J.M. and J.O.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the ANID Millennium Science Initiative/Millennium Initiative for Collaborative Research on Bacterial Resistance, MICROB-R, NCN17-08 and FONDECYT grant Nº 1240316

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMR |

Antimicrobial Resistance |

| ARG |

Antimicrobial-Resistance Gene |

| ARB |

Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacteria |

| CAZ |

Ceftazidime |

| CIP |

Ciprofloxacin |

| MDR |

Multidrug-resistant |

References

- Salam, M.A.; Al-Amin, M.Y.; Salam, M.T.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alqumber, M.A.A. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare. 2023, 11, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naghavi, M.; Vollset, S.E.; Ikuta, K.S.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Gray, A.P.; Wool, E.E.; Aguilar, G.R.; Mestrovic, T.; Smith, G.; Han, C.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance 1990–2021: A Systematic Analysis with Forecasts to 2050. The Lancet 2024, 404, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, G.; Midiri, A.; Gerace, E.; Biondo, C. Bacterial Antibiotic Resistance: The Most Critical Pathogens. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesho, E.P.; Laguio-Vila, M. The Slow-Motion Catastrophe of Antimicrobial Resistance and Practical Interventions for All Prescribers. Mayo Clin Proc 2019, 94, 1040–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.C.; Oxlade, C. Innovate to Secure the Future: The Future of Modern Medicine. Future Healthc J 2021, 8, e251–e256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.L. Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Natural Environments. Science. 2008, 321, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquero, F.; Martínez, J.L.; Cantón, R.; Martinez, J.L.; Canton, R. Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance in Water Environments. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008, 19, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fajardo, A.; Martinez, J.L. Antibiotics as Signals That Trigger Specific Bacterial Responses. Curr Opin Microbiol 2008, 11, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Gong, Z.; Wang, S.; Song, L. Occurrence and Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Pathogens in an Industrial Park Wastewater Treatment Plant. Sci Total Environ 2023, 880, 163278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Pratap, S.G.; Raj, A. Occurrence and Dissemination of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance in Aquatic Environment and Its Ecological Implications: A Review. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2024, 31, 47505–47529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.; Machado, I.; Simões, L.C.; Simões, M. Biocides as Drivers of Antibiotic Resistance: A Critical Review of Environmental Implications and Public Health Risks. Environ Sci Ecotechnol 2025, 25, 100557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checcucci, A.; Buscaroli, E.; Modesto, M.; Luise, D.; Blasioli, S.; Scarafile, D.; Di Vito, M.; Bugli, F.; Trevisi, P.; Braschi, I.; et al. The Swine Waste Resistome: Spreading and Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Escherichia coli Strains and the Associated Microbial Communities. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2024, 283, 116774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samreen; Ahmad, I.; Malak, H.A.; Abulreesh, H.H. Environmental Antimicrobial Resistance and Its Drivers: A Potential Threat to Public Health. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2021, 27, 101–111. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skandalis, N.; Maeusli, M.; Papafotis, D.; Miller, S.; Lee, B.; Theologidis, I.; Luna, B. Environmental Spread of Antibiotic Resistance. Antibiotics. 2021, 10, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajayi, A.O.; Odeyemi, A.T.; Akinjogunla, O.J.; Adeyeye, A.B.; Ayo-ajayi, I. Review of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria and Antibiotic Resistance Genes within the One Health Framework. Infect Ecol Epidemiol 2024, 14, 2312953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Yu, S.; Li, D.; Gillings, M.R.; Ren, H.; Mao, D.; Guo, J.; Luo, Y. Inter-Plasmid Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance Genes Accelerates Antibiotic Resistance in Bacterial Pathogens. ISME J 2024, 18, wrad032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeusli, M.; Lee, B.; Miller, S.; Reyna, Z.; Lu, P.; Yan, J.; Ulhaq, A.; Skandalis, N.; Spellberg, B.; Luna, B. Horizontal Gene Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance from Acinetobacter baylyi to Escherichia coli on Lettuce and Subsequent Antibiotic Resistance Transmission to the Gut Microbiome. mSphere 2020, 5, 110–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FRAM Case Study: Aconcagua River in Chile - the Polluted Drinking Water Supplier | University of Gothenburg. Available online: https://www.gu.se/en/research/fram-case-study-aconcagua-river-in-chile-the-polluted-drinking-water-supplier (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Inostroza, P.A.; Jessen, G.L.; Li, F.; Zhang, X.; Brack, W.; Backhaus, T. Multi-Compartment Impact of Micropollutants and Particularly Antibiotics on Bacterial Communities Using Environmental DNA at River Basin-Level. Environ Pollut 2025, 366, 125487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaete, H.; Aránguiz, F.; Cienfuegos, G.; Tejos, M. Heavy Metals and Toxicity of Waters of the Aconcagua River in Chile. Quim Nova 2007, 30, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernando-Amado, S.; Coque, T.M.; Baquero, F.; Martínez, J.L. Defining and Combating Antibiotic Resistance from One Health and Global Health Perspectives. Nat Microbiol 2019, 4, 1432–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, A.H.; Moore, L.S.P.; Sundsfjord, A.; Steinbakk, M.; Regmi, S.; Karkey, A.; Guerin, P.J.; Piddock, L.J.V. Understanding the Mechanisms and Drivers of Antimicrobial Resistance. The Lancet 2016, 387, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero-Cáceres, W.; Marti, E.; Olivares-Pacheco, J.; Rodriguez-Rubio, L. Editorial: Antimicrobial Resistance in Aquatic Environments. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 866268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivares-Pacheco, J.; Marti, E.; Rodríguez-Rubio, L.; Calero-Cáceres, W. Editorial: Antimicrobial Resistance in Aquatic Environments, Volume II. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1211464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lu, S.; Guo, W.; Xi, B.; Wang, W. Antibiotics in the Aquatic Environments: A Review of Lakes, China. Sci Total Environ 2018, 627, 1195–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kümmerer, K. Antibiotics in the Aquatic Environment--a Review--Part II. Chemosphere 2009, 75, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manaia, C.M.; Macedo, G.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Nunes, O.C. Antibiotic Resistance in Urban Aquatic Environments: Can It Be Controlled? Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2016, 100, 1543–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, M.Y.; Da’na, D.A.; Al-Ghouti, M.A. Application of MALDI-TOF MS for Identification of Environmental Bacteria: A Review. J Environ Manage 2022, 305, 114359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, M.; Kimothi, A.; Sharma, A.; Pandey, A. Cold Adapted Pseudomonas: Ecology to Biotechnology. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1218708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silby, M.W.; Winstanley, C.; Godfrey, S.A.C.; Levy, S.B.; Jackson, R.W. Pseudomonas Genomes: Diverse and Adaptable. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2011, 35, 652–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horváth, A.; Dobay, O.; Kardos, S.; Ghidán, Á.; Tóth, Á.; Pászti, J.; Ungvári, E.; Horváth, P.; Nagy, K.; Zissman, S.; et al. Varying Fitness Cost Associated with Resistance to Fluoroquinolones Governs Clonal Dynamic of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2012, 31, 2029–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, Á.; Kocsis, B.; Damjanova, I.; Kristóf, K.; Jánvári, L.; Pászti, J.; Csercsik, R.; Topf, J.; Szabó, D.; Hamar, P.; et al. Fitness Cost Associated with Resistance to Fluoroquinolones is Diverse across Clones of Klebsiella pneumoniae and May Select for CTX-M-15 Type Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014, 33, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zeng, J.; Li, S.; Liang, P.; Zheng, C.; Liu, Y.; Luo, T.; Rastogi, N.; Sun, Q. Interaction between rpsL and gyrA Mutations Affects the Fitness and Dual Resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Clinical Isolates against Streptomycin and Fluoroquinolones. Infect Drug Resist 2018, 11, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp-Wallace, K.M.; Endimiani, A.; Taracila, M.A.; Bonomo, R.A. Carbapenems: Past, Present, and Future. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011, 55, 4943–4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halat, D.H.; Moubareck, C.A. The Intriguing Carbapenemases of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Current Status, Genetic Profile, and Global Epidemiology. Yale J Biol Med 2022, 95, 507. [Google Scholar]

- Poirel, L.; Pitout, J.D.; Nordmann, P. Carbapenemases: Molecular Diversity and Clinical Consequences. Future Microbiol 2007, 2, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.J.; Bae, I.K.; Jang, I.H.; Jeong, S.H.; Kang, H.K.; Lee, K. Epidemiology and Characteristics of Metallo-ß-Lactamase-Producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Chemother 2015, 47, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catho, G.; Martischang, R.; Boroli, F.; Chraïti, M.N.; Martin, Y.; Koyluk Tomsuk, Z.; Renzi, G.; Schrenzel, J.; Pugin, J.; Nordmann, P.; et al. Outbreak of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Producing VIM Carbapenemase in an Intensive Care Unit and Its Termination by Implementation of Waterless Patient Care. Crit Care 2021, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaia, C.M.; Macedo, G.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Nunes, O.C. Antibiotic Resistance in Urban Aquatic Environments: Can it be Controlled? Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2016, 100, 1543–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Mozaz, S.; Chamorro, S.; Marti, E.; Huerta, B.; Gros, M.; Sànchez-Melsió, A.; Borrego, C.M.; Barceló, D.; Balcázar, J.L. Occurrence of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Hospital and Urban Wastewaters and Their Impact on the Receiving River. Water Res 2015, 69, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiry, D.; Entezari Heravi, N.; Uluseker, C.; Kaster, K.M.; Kommedal, R.; Pala-Ozkok, I. The Effect of Disinfectants and Antiseptics on Co- and Cross-Selection of Resistance to Antibiotics in Aquatic Environments and Wastewater Treatment Plants. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 1050558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uluseker, C.; Kaster, K.M.; Thorsen, K.; Basiry, D.; Shobana, S.; Jain, M.; Kumar, G.; Kommedal, R.; Pala-Ozkok, I. A Review on Occurrence and Spread of Antibiotic Resistance in Wastewaters and in Wastewater Treatment Plants: Mechanisms and Perspectives. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 717809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Gavidia, C.; Barría, C.; Rivas, L.; García, P.; Alvarez, F.P.; González-Rocha, G.; Opazo-Capurro, A.; Araos, R.; Munita, J.M.; Cortes, S.; et al. Isolation of Ciprofloxacin and Ceftazidime-Resistant Enterobacterales from Vegetables and River Water is Strongly Associated with the Season and the Sample Type. Front Microbiol 2021, 2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trick, W.E. Decision Making During Healthcare-Associated Infection Surveillance: A Rationale for Automation. Clinl Infect Dis 2013, 57, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizzini, A.; Greub, G. Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry, a Revolution in Clinical Microbial Identification. Clin Microbiol and Infect 2010, 16, 1614–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Manual M100; 33rd ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2023.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Methods for Antimicrobial Dilution and Disk Susceptibility Testing of Infrequently Isolated or Fastidious Bacteria. Manual M45; 3rd ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2016.

- Magiorakos, A.-P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B. Multidrug-Resistant, Extensively Drug-Resistant and Pandrug-Resistant Bacteria: An International Expert Proposal for Interim Standard Definitions for Acquired Resistance. Clin Microbiol infect 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccari, L.; Ceriana, P.; Granchetti, H.N.; Pezzaniti, A.V.; Lucero, C.; Rapoport, M.; Menocal, A.; Corso, A.; Pasteran, F. Improved Blue Carba Test and Carba NP Test for Detection and Classification of Major Class A and B Carbapenemases, Including Dual Producers, among Gram-Negative Bacilli. J Clin Microbiol 2024, 62, e01255–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirel, L.; Walsh, T.R.; Cuvillier, V.; Nordmann, P. Multiplex PCR for Detection of Acquired Carbapenemase Genes. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2011, 70, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolter, D.J.; Khalaf, N.; Robledo, I.E.; Vázquez, J.G.; Santé, I.M.; Aquino, E.E.; Goering, R. V.; Hanson, N.D. Surveillance of Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolates from Puerto Rican Medical Center Hospitals: Dissemination of KPC and IMP-18 β-Lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009, 53, 1660–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellington, M.J.; Kistler, J.; Livermore, D.M.; Woodford, N. Multiplex PCR for Rapid Detection of Genes Encoding Acquired Metallo-β-Lactamases. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007, 59, 321–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Distribution of bacterial genera isolated from the river and identified by MALDI-TOF.

Figure 1.

Distribution of bacterial genera isolated from the river and identified by MALDI-TOF.

Figure 3.

Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of bacterial isolates recovered from ceftazidime-supplemented media. Bars represent the percentage of isolates classified as susceptible (green), resistant (red), or intermediate (yellow) according to CLSI guidelines. Abbreviations: ATM, aztreonam; CAZ, ceftazidime; FEP, cefepime; IMP, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; CRO, ceftriaxone; C, chloramphenicol; CIP, ciprofloxacin; SXT, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; CN, gentamicin; LEV, levofloxacin; AK, amikacin; TZP, piperacillin/tazobactam.

Figure 3.

Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of bacterial isolates recovered from ceftazidime-supplemented media. Bars represent the percentage of isolates classified as susceptible (green), resistant (red), or intermediate (yellow) according to CLSI guidelines. Abbreviations: ATM, aztreonam; CAZ, ceftazidime; FEP, cefepime; IMP, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; CRO, ceftriaxone; C, chloramphenicol; CIP, ciprofloxacin; SXT, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; CN, gentamicin; LEV, levofloxacin; AK, amikacin; TZP, piperacillin/tazobactam.

Figure 4.

Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of selected bacterial isolates. (A) Pseudomonas spp. isolates; (B) Aeromonas spp. isolates. Bacterial isolates were identified by MALDI-TOF and its sampling point (P1–P11). Colors indicate susceptibility classification based on CLSI guidelines: green (susceptible), yellow (intermediate), and red (resistant). Antibiotic abbreviations: ATM, aztreonam; FEP, cefepime; CAZ, ceftazidime; LEV, levofloxacin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CN, gentamicin; AK, amikacin; IMP, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; TZP, piperacillin/tazobactam; CRO, ceftriaxone; SXT, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; C, chloramphenicol; TE, tetracycline.

Figure 4.

Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of selected bacterial isolates. (A) Pseudomonas spp. isolates; (B) Aeromonas spp. isolates. Bacterial isolates were identified by MALDI-TOF and its sampling point (P1–P11). Colors indicate susceptibility classification based on CLSI guidelines: green (susceptible), yellow (intermediate), and red (resistant). Antibiotic abbreviations: ATM, aztreonam; FEP, cefepime; CAZ, ceftazidime; LEV, levofloxacin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CN, gentamicin; AK, amikacin; IMP, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; TZP, piperacillin/tazobactam; CRO, ceftriaxone; SXT, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; C, chloramphenicol; TE, tetracycline.

Figure 4.

Map of the Aconcagua River in central Chile. Red dots indicate the sampling sites. The labeled cities are those with over 50,000 inhabitants through which the river directly flows.

Figure 4.

Map of the Aconcagua River in central Chile. Red dots indicate the sampling sites. The labeled cities are those with over 50,000 inhabitants through which the river directly flows.

Table 1.

Primers and PCR conditions for amplification of carbapenemases.

Table 1.

Primers and PCR conditions for amplification of carbapenemases.

| Gene |

Primer Sequences (5'-3') |

Amplicon Size (bp) |

PCR conditions |

Ref |

| blaKPC |

F: CGTCTAGTTCTGCTGTCTTG R: CTTGTCATCCTTGTTAGGCG |

798 |

95 ºC |

10 min |

30 cycles |

[50] |

| 95 ºC |

30 sec |

| 55 ºC |

30 sec |

| 72 ºC |

1 min |

| 72 ºC |

10 min |

| blaVIM |

F: GGTGTTTGGTCGCATATCGC R: CCATTCAGCCAGATCGGCATC |

504 |

95 ºC |

10 min |

30 cycles |

[51] |

| 95 ºC |

30 sec |

| 60 ºC |

30 sec |

| 72 ºC |

30 sec |

| 72 ºC |

10 min |

| blaNDM |

F: GGTTTGGCGATCTGGTTTTC R: CGGTGATATTGTCACTGGTGTGG |

452 |

95 ºC |

10 min |

30 cycles |

[50] |

| 95 ºC |

30 sec |

| 60 ºC |

30 sec |

| 72 ºC |

30 sec |

| 72 ºC |

10 min |

| blaIMP |

F: GGAATAGAGTGGCTTAAYTCT R: CCAACYACTASGTTATCT |

188 |

95 ºC |

10 min |

30 cycles |

[52] |

| 95 ºC |

30 sec |

| 55 ºC |

30 sec |

| 72 ºC |

15 min |

| 72 ºC |

10 min |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).