Submitted:

30 September 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

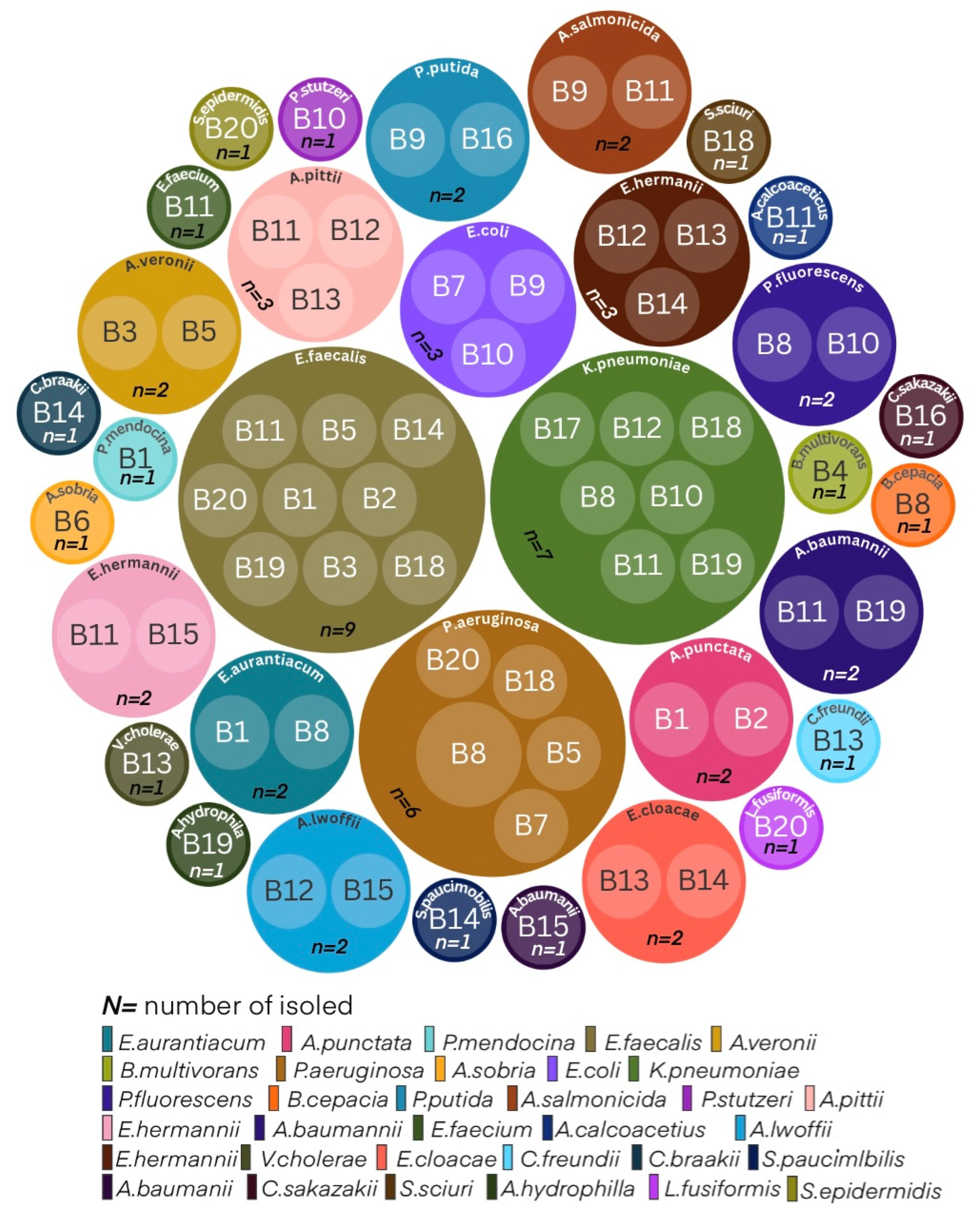

A Recycled wastewater is vital for circular economy, especially on water-scarce islands. This study explored the presence of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales and other emerging pathogens in irrigation water on four Canarian Islands, applying a One Health perspective. Using membrane filtration and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, 69 bacterial isolates were identified. The finding reveals that 50% were gram-negative bacilli like Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter spp., while 30% were Enterobacteriaceae, including Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli. The main mechanisms of carbapenem resistance in Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter were oxacillinases, followed by metallo-β-lactamases (MBL). In Enterobacteriaceae, characterization of carbapenemase types was less frequent, with OXA-48 being the most prevalent. The detection of multidrug-resistant organisms in recycled wastewater highlights an urgent need for routine microbiological monitoring in water management protecting public health and agricultural sustainability.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

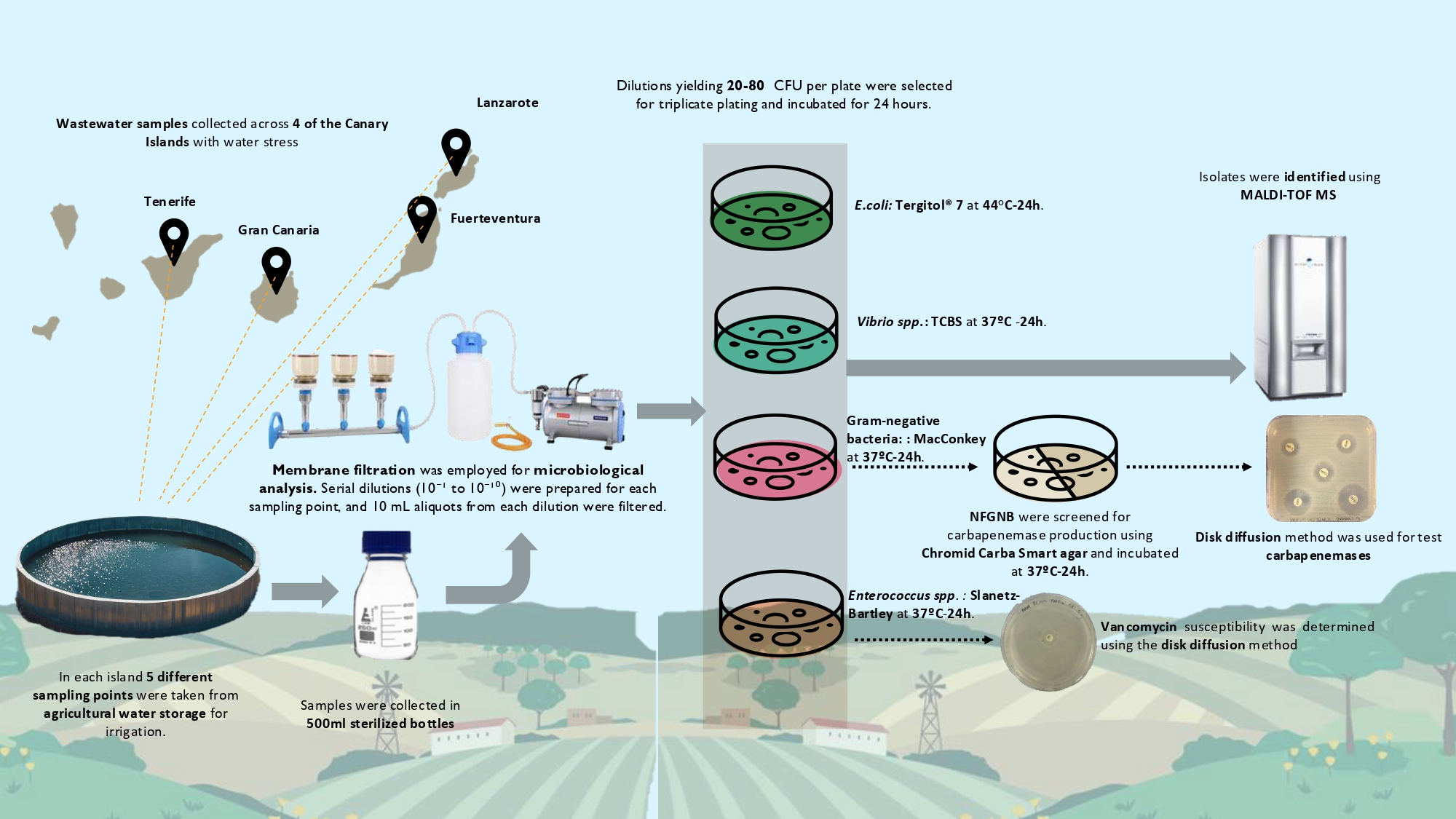

2. Materials and Methods

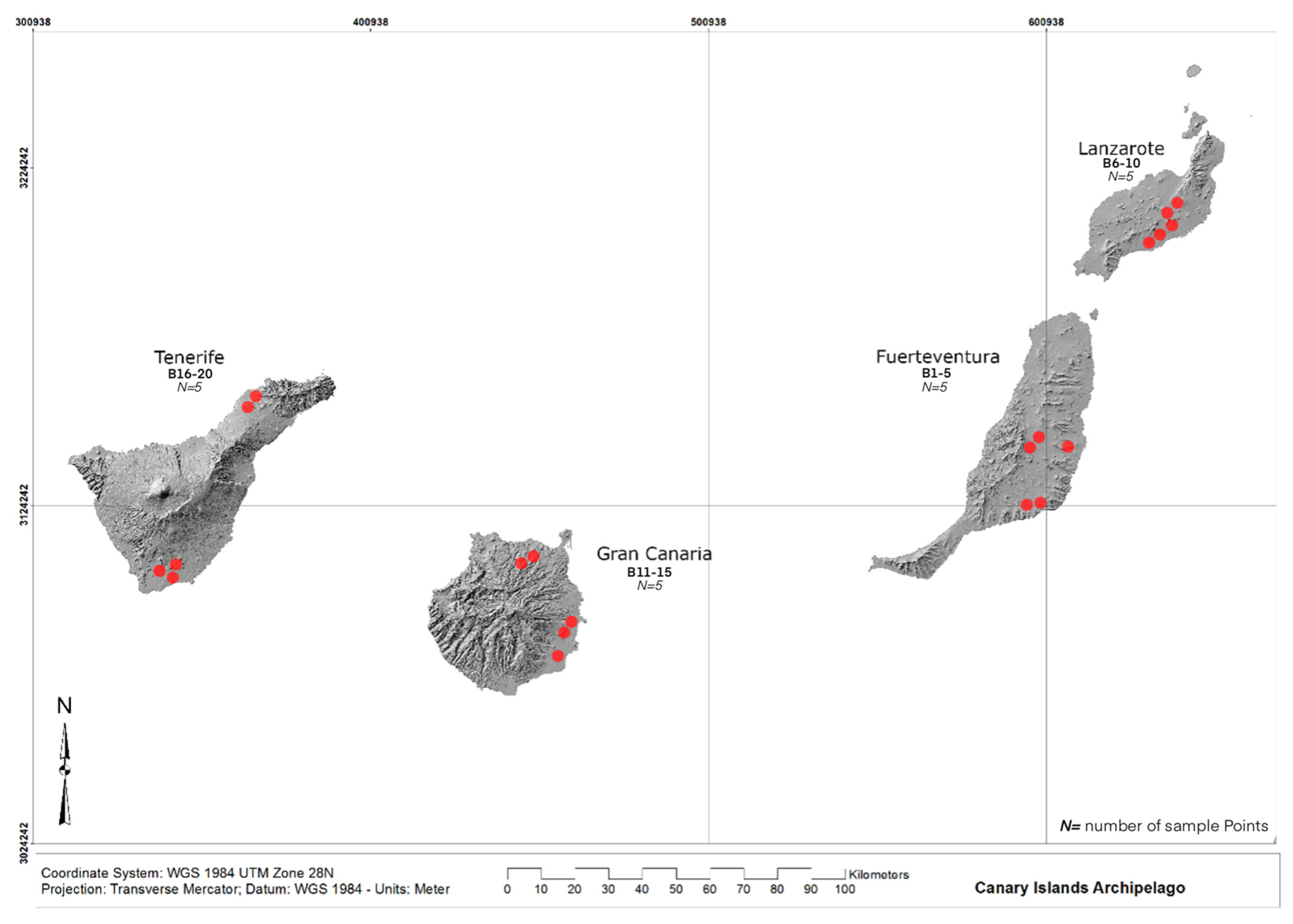

2.1. Study area and fieldwork

2.2. Microbial Culturing

2.3. Identification and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

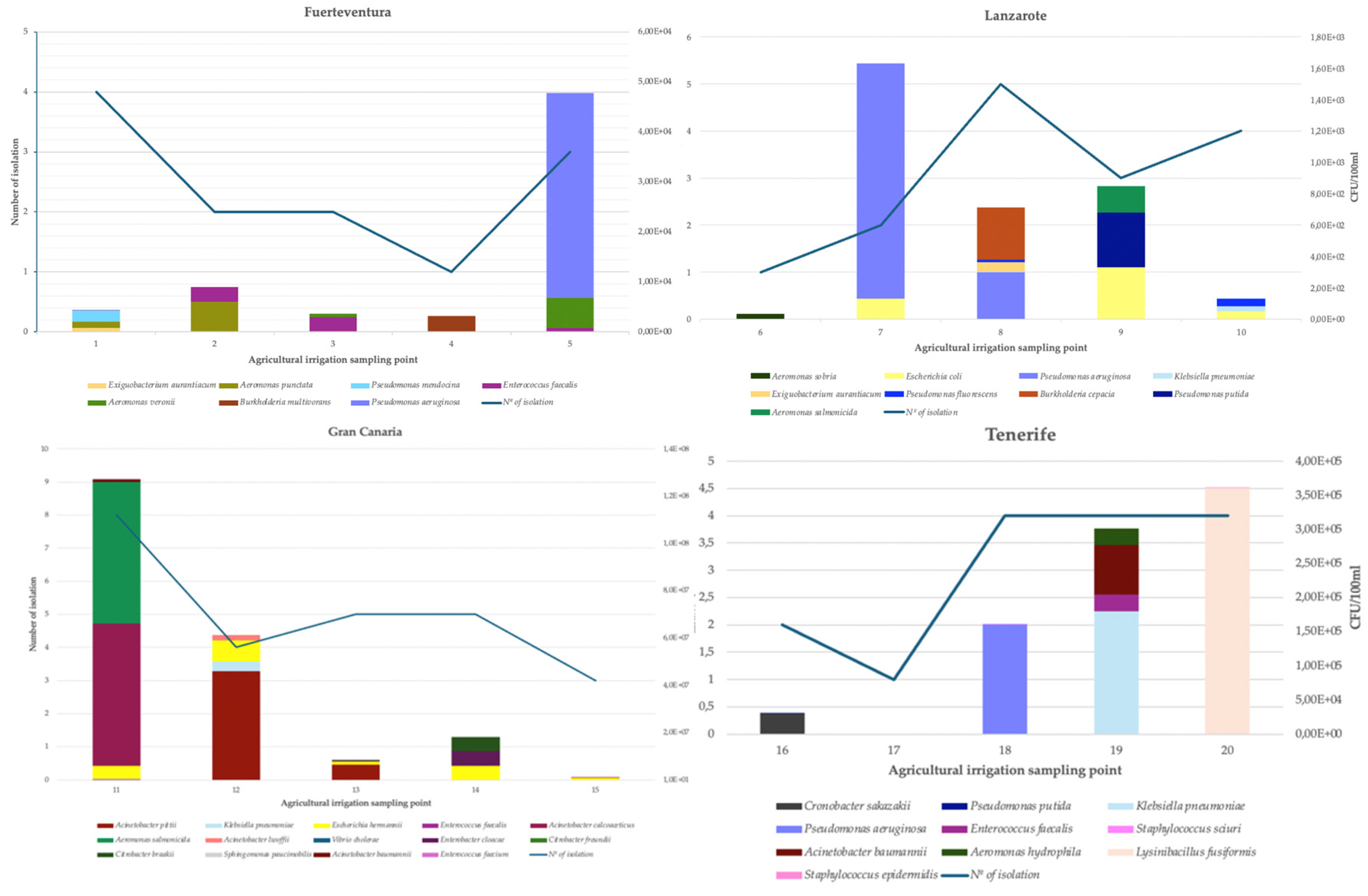

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| CFU | colony-forming-units |

| MALDI-TOF MS | Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. |

| NFGNB | non-fermentative Gram-negative bacilli |

| KPC | Carbapenemasa Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| MBL | Metalo-β-lactamasa |

| OXA | Oxacilinasas |

| WWTP | Waste Water Treatment Plant |

References

- Atay I, Saladié >Òscar. Water Scarcity and Climate Change in Mykonos (Greece): The Perceptions of the Hospitality Stakeholders. Tourism and Hospitality 2022, Vol 3, Pages 765-787 [Internet]. 2022 Sep 6 [cited 2025 Jun 29];3(3):765–87. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2673-5768/3/3/47/htm.

- Bernabé-Crespo MB, Loáiciga H. Managing Potable Water in Southeastern Spain, Los Angeles, and Sydney: Transcontinental Approaches to Overcome Water Scarcity. Water Resources Management [Internet]. 2024 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Jun 29];38(4):1299–313. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11269-023-03721-8.

- Schallenberg-Rodríguez J, Veza JM, Blanco-Marigorta A. Energy efficiency and desalination in the Canary Islands. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2014 Dec 1;40:741–8.

- Cruz-Pérez N, Santamarta JC, Álvarez-Acosta C. Water footprint of representative agricultural crops on volcanic islands: the case of the Canary Islands. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems [Internet]. 2023 Aug 4 [cited 2025 Jan 17];38:e36. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/renewable-agriculture-and-food-systems/article/water-footprint-of-representative-agricultural-crops-on-volcanic-islands-the-case-of-the-canary-islands/B80B6B6C58E185B66062D3E772B45722.

- Aguilera-Klink F, Pérez-Moriana E, Sánchez-García J. The social construction of scarcity. The case of water in Tenerife (Canary Islands). Ecological Economics. 2000 Aug;34(2):233–45.

- Dwight RH, Fernandez LM, Baker DB, Semenza JC, Olson BH. Estimating the economic burden from illnesses associated with recreational coastal water pollution - A case study in Orange County, California. J Environ Manage. 2005;76(2):95–103.

- Jacob J, Moilleron R, Thiebault T, Jung YJ, Aung Khant N, Kim H, et al. Impact of Climate Change on Waterborne Diseases: Directions towards Sustainability. Water 2023, Vol 15, Page 1298 [Internet]. 2023 Mar 25 [cited 2025 Sep 4];15(7):1298. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/15/7/1298/htm.

- Mora C, McKenzie T, Gaw IM, Dean JM, von Hammerstein H, Knudson TA, et al. Over half of known human pathogenic diseases can be aggravated by climate change. Nature Climate Change 2022 12:9 [Internet]. 2022 Aug 8 [cited 2025 Sep 4];12(9):869–75. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-022-01426-1.

- Seymour JR, McLellan SL. Climate change will amplify the impacts of harmful microorganisms in aquatic ecosystems. Nature Microbiology 2025 10:3 [Internet]. 2025 Feb 28 [cited 2025 Sep 4];10(3):615–26. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41564-025-01948-2.

- Ingrao C, Strippoli R, Lagioia G, Huisingh D. Water scarcity in agriculture: An overview of causes, impacts and approaches for reducing the risks. Heliyon [Internet]. 2023 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Jun 29];9(8):e18507. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405844023057158.

- Levintal E, Kniffin ML, Ganot Y, Marwaha N, Murphy NP, Dahlke HE. Agricultural managed aquifer recharge (Ag-MAR)—a method for sustainable groundwater management: A review. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 29];53(3):291–314. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/10643389.2022.2050160.

- Mainardis M, Cecconet D, Moretti A, Callegari A, Goi D, Freguia S, et al. Wastewater fertigation in agriculture: Issues and opportunities for improved water management and circular economy. Environmental Pollution [Internet]. 2022 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Jun 29];296:118755. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S026974912102337X.

- Radcliffe JC. Current status of recycled water for agricultural irrigation in Australia, potential opportunities and areas of emerging concern. Science of The Total Environment [Internet]. 2022 Feb 10 [cited 2025 Jun 29];807:151676. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969721067528.

- Cosenza A, Carnesi M, Calantoni D, Ferrante M, Mannina G. Transition to Circular Economy in the Water Sector by Legislative Perspectives for the Sicilian Region (Italy). Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 29];524 LNCE:457–63. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-63353-9_77.

- Maffettone R, Manoli K, Drei P, Cacciatori C, Bellini R, Gawlik BM, et al. Water Reuse in the European Union: Risk Management Approach According to the Regulation (EU) 2020/741. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 29];413–42. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-67739-7_17.

- Ricciardo Calderaro M, Fusco A, Caterina Amitrano C, Ricciardo Calderaro M, Fusco A, Amitrano CC. The European Union Regulation 2020/741: From the Management of Water Resources to the EU Legislation for Its Reuse. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 29];395–412. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-67739-7_16.

- Shemer H, Wald S, Semiat R. Challenges and Solutions for Global Water Scarcity. Membranes 2023, Vol 13, Page 612 [Internet]. 2023 Jun 20 [cited 2025 Jun 29];13(6):612. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0375/13/6/612/htm.

- Maffettone R, Manoli K, Drei P, Cacciatori C, Bellini R, Gawlik BM, et al. Water Reuse in the European Union: Risk Management Approach According to the Regulation (EU) 2020/741. 2024 [cited 2025 Jan 17];413–42. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-67739-7_17.

- Hristov J, Barreiro-Hurle J, Salputra G, Blanco M, Witzke P. Reuse of treated water in European agriculture: Potential to address water scarcity under climate change. Agric Water Manag. 2021 May 31;251:106872.

- Mainardis M, Cecconet D, Moretti A, Callegari A, Goi D, Freguia S, et al. Wastewater fertigation in agriculture: Issues and opportunities for improved water management and circular economy. Environmental Pollution. 2022 Mar 1;296:118755.

- Liu X, Liu W, Tang Q, Liu B, Wada Y, Yang H. Global Agricultural Water Scarcity Assessment Incorporating Blue and Green Water Availability Under Future Climate Change. Earths Future [Internet]. 2022 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Jan 17];10(4):e2021EF002567. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2021EF002567.

- McEwen SA, Collignon PJ. Antimicrobial Resistance: a One Health Perspective. Microbiol Spectr [Internet]. 2018 Apr 6 [cited 2025 Jun 29];6(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29600770/.

- Salam MA, Al-Amin MY, Salam MT, Pawar JS, Akhter N, Rabaan AA, et al. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare 2023, Vol 11, Page 1946 [Internet]. 2023 Jul 5 [cited 2025 Jun 29];11(13):1946. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/11/13/1946/htm.

- Penserini L, Cantoni B, Gabrielli M, Sezenna E, Saponaro S, Antonelli M. An integrated human health risk assessment framework for alkylphenols due to drinking water and crops’ food consumption. Chemosphere [Internet]. 2023 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Aug 13];325:138259. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S004565352300526X?via%3Dihub.

- Penserini L, Cantoni B, Antonelli M. Modelling the impacts generated by reclaimed wastewater reuse in agriculture: From literature gaps to an integrated risk assessment in a One Health perspective. J Environ Manage [Internet]. 2024 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Aug 13];371:122715. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301479724027014?via%3Dihub.

- Wise MG, Karlowsky JA, Mohamed N, Hermsen ED, Kamat S, Townsend A, et al. Global trends in carbapenem- and difficult-to-treat-resistance among World Health Organization priority bacterial pathogens: ATLAS surveillance program 2018–2022. J Glob Antimicrob Resist [Internet]. 2024 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Jun 29];37:168–75. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38608936/.

- Dandachi I, Chaddad A, Hanna J, Matta J, Daoud Z. Understanding the epidemiology of multi-drug resistant gram-negative bacilli in the middle east using a one health approach. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Jun 29];10(AUG). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31507558/.

- Hassoun-Kheir N, Stabholz Y, Kreft JU, de la Cruz R, Romalde JL, Nesme J, et al. Comparison of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes abundance in hospital and community wastewater: A systematic review. Science of The Total Environment [Internet]. 2020 Nov 15 [cited 2025 Aug 13];743:140804. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S004896972034328X?via%3Dihub.

- Carattoli A. Resistance plasmid families in Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother [Internet]. 2009 Jun [cited 2025 Jun 29];53(6):2227–38. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19307361/.

- Carattoli A. Plasmids in Gram negatives: Molecular typing of resistance plasmids. International Journal of Medical Microbiology [Internet]. 2011 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Jun 29];301(8):654–8. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1438422111000890.

- Carattoli A. Plasmids and the spread of resistance. International Journal of Medical Microbiology [Internet]. 2013 Aug [cited 2025 Jun 29];303(6–7):298–304. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23499304/.

- Lamba M, Graham DW, Ahammad SZ. Hospital Wastewater Releases of Carbapenem-Resistance Pathogens and Genes in Urban India. Environ Sci Technol [Internet]. 2017 Dec 5 [cited 2025 Jun 29];51(23):13906–12. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.7b03380.

- Guo J, Li J, Chen H, Bond PL, Yuan Z. Metagenomic analysis reveals wastewater treatment plants as hotspots of antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements. Water Res [Internet]. 2017 Oct 15 [cited 2025 Sep 4];123:468–78. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0043135417305651.

- Drigo B, Brunetti G, Aleer SC, Bell JM, Short MD, Vasileiadis S, et al. Inactivation, removal, and regrowth potential of opportunistic pathogens and antimicrobial resistance genes in recycled water systems. Water Res [Internet]. 2021 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Sep 4];201:117324. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0043135421005224.

- Jjemba P, Johnson W, Bukhari Z, LeChevallier M. Review of the leading challenges in maintaining reclaimed water quality during storage and distribution. Journal of Water Reuse and Desalination [Internet]. 2014 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Sep 23];4(4):209–37. Available from: http://iwaponline.com/jwrd/article-pdf/4/4/209/378145/209.pdf.

- Reichert G, Hilgert S, Alexander J, Rodrigues de Azevedo JC, Morck T, Fuchs S, et al. Determination of antibiotic resistance genes in a WWTP-impacted river in surface water, sediment, and biofilm: Influence of seasonality and water quality. Science of The Total Environment [Internet]. 2021 May 10 [cited 2025 Sep 23];768:144526. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0048969720380578?via%3Dihub.

- Song P, Xiao Y, Muhammad T, Li Y. Impact of key water quality factors on microbial community and biofilm formation in reclaimed water distribution systems. J Environ Chem Eng [Internet]. 2025 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Sep 23];13(5):117554. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S221334372502250X?via%3Dihub.

- Brienza M, Sauvêtre A, Ait-Mouheb N, Bru-Adan V, Coviello D, Lequette K, et al. Reclaimed wastewater reuse in irrigation: Role of biofilms in the fate of antibiotics and spread of antimicrobial resistance. Water Res [Internet]. 2022 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Sep 24];221:118830. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0043135422007795.

- Attrah M, Schärer MR, Esposito M, Gionchetta G, Bürgmann H, Lens PNL, et al. Disentangling abiotic and biotic effects of treated wastewater on stream biofilm resistomes enables the discovery of a new planctomycete beta-lactamase. Microbiome [Internet]. 2024 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Sep 24];12(1):1–15. Available from: https://microbiomejournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40168-024-01879-w.

- Bhattacharyya A, Haldar A, Bhattacharyya M, Ghosh A. Anthropogenic influence shapes the distribution of antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB) in the sediment of Sundarban estuary in India. Science of the Total Environment [Internet]. 2019 Jan 10 [cited 2025 Sep 10];647:1626–39. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30180366/.

- Plan de gestión del riesgo del agua regenerada [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/agua/temas/concesiones-y-autorizaciones/reutilizacion-aguas-depuradas/plan-de-gestion-del-riesgo-del-agua-regenerada.html.

- Aguilera-Klink F, Pérez-Moriana E, Sánchez-García J. The social construction of scarcity. The case of water in Tenerife (Canary Islands). Ecological Economics [Internet]. 2000 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Jun 29];34(2):233–45. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0921800900001609.

- Inicio ISTAC - Gobierno de Canarias [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 30]. Available from: https://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/istac/.

- Quesada-Ruiz LC, García-Romero L, Ferrer-Valero N. Mapping environmental crime to characterize human impacts on islands: an applied and methodological research in Canary Islands. J Environ Manage [Internet]. 2023 Nov 15 [cited 2025 Jun 29];346:118959. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301479723017474.

- Cruz-Pérez N, Santamarta JC, Álvarez-Acosta C. Water footprint of representative agricultural crops on volcanic islands: the case of the Canary Islands. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems [Internet]. 2023 Aug 4 [cited 2025 Jun 29];38:e36. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/renewable-agriculture-and-food-systems/article/water-footprint-of-representative-agricultural-crops-on-volcanic-islands-the-case-of-the-canary-islands/B80B6B6C58E185B66062D3E772B45722.

- Pérez-Reverón R, Grattan SR, Perdomo-González A, Pérez-Pérez JA, Díaz-Peña FJ. Marginal quality waters: Adequate resources for sustainable forage production in saline soils? Agric Water Manag [Internet]. 2024 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Jun 29];305:109142. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378377424004785.

- Ashfaq MY, Da’na DA, Al-Ghouti MA. Application of MALDI-TOF MS for identification of environmental bacteria: A review. J Environ Manage [Internet]. 2022 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Aug 13];305:114359. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S030147972102421X?via%3Dihub.

- Puljko A, Barišić I, Dekić Rozman S, Križanović S, Babić I, Jelić M, et al. Molecular epidemiology and mechanisms of carbapenem and colistin resistance in Klebsiella and other Enterobacterales from treated wastewater in Croatia. Environ Int [Internet]. 2024 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Aug 13];185:108554. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412024001405.

- Dikoumba AC, Onanga R, Jean-Pierre H, Didelot MN, Dumont Y, Ouedraogo AS, et al. Prevalence and Phenotypic and Molecular Characterization of Carbapenemase-Producing Gram-Negative Bacteria in Gabon. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene [Internet]. 2023 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Jun 29];108(2):268–74. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36535247/.

- Lee SY, Octavia S, Chew KL. Detection of OXA-carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae with chromID CARBA SMART screening plate. Pathology [Internet]. 2019 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Jun 29];51(1):108–10. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30454880/.

- Hopkins KL, Meunier D, Mustafa N, Pike R, Woodford N. Evaluation of temocillin and meropenem MICs as diagnostic markers for OXA-48-like carbapenemases. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy [Internet]. 2019 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Jun 29];74(12):3641–3. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Sun K, Xu X, Yan J, Zhang L. Evaluation of six phenotypic methods for the detection of carbapenemases in gram-negative bacteria with characterized resistance mechanisms. Ann Lab Med [Internet]. 2017 Jul 1 [cited 2025 Jun 29];37(4):305–12. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28445009/.

- Hegstad K, Giske CG, Haldorsen B, Matuschek E, Schønning K, Leegaard TM, et al. Performance of the EUCAST disk diffusion method, the CLSI agar screen method, and the Vitek 2 automated antimicrobial susceptibility testing system for detection of clinical isolates of enterococci with low- and medium-level VanB-type vancomycin resistance: A multicenter study. J Clin Microbiol [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2025 Jun 29];52(5):1582–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24599985/.

- ISTAC. ISTAC | Efectivos de ganado según especies, categorías de animales y razas. Islas de Canarias por años | Banco de datos [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 29]. Available from: https://www3.gobiernodecanarias.org/istac/statistical-visualizer/visualizer/data.html?agencyId=ISTAC&resourceId=E01008B_000019&version=1.5&resourceType=dataset&multidatasetId=ISTAC:E01008B_000001#visualization/table.

- Denissen J, Havenga B, Reyneke B, Khan S, Khan W. Comparing antibiotic resistance and virulence profiles of Enterococcus faecium, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa from environmental and clinical settings. Heliyon [Internet]. 2024 May 15 [cited 2025 Jun 29];10(9):e30215. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405844024062467.

- Liu Y, Yang K, Wang Y, Hao C, Li Y, Zhu H, et al. Intestinal bacteria aerosols from hospital and municipal wastewater treatment: Seasonal variations, dispersal characteristics and toxic effects. Environ Res [Internet]. 2025 Apr 15 [cited 2025 Jun 29];271:121058. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0013935125003093.

- Tsvetanova Z, Boshnakov R. Antimicrobial Resistance of Waste Water Microbiome in an Urban Waste Water Treatment Plant. Water (Switzerland) [Internet]. 2025 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Jun 29];17(1):39. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/17/1/39/htm.

- Deblais L, Ahmedo BU, Ojeda A, Mummed B, Wang Y, Mekonnen YT, et al. Assessing fecal contamination from human and environmental sources using Escherichia coli as an indicator in rural eastern Ethiopian households—a cross-sectional study from the EXCAM project. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2025 Jan 6 [cited 2025 Jun 29];12:1484808. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11743629/.

- Stec J, Kosikowska U, Mendrycka M, Stępień-Pyśniak D, Niedźwiedzka-Rystwej P, Bębnowska D, et al. Opportunistic Pathogens of Recreational Waters with Emphasis on Antimicrobial Resistance—A Possible Subject of Human Health Concern. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2022 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Jun 29];19(12). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35742550/.

- Regulation - 2020/741 - EN - EUR-Lex [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 13]. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2020/741/oj/eng.

- Water Sanitation and Health [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/environment-climate-change-and-health/water-sanitation-and-health/sanitation-safety/guidelines-for-safe-use-of-wastewater-greywater-and-excreta.

- European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net) [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/about-us/networks/disease-networks-and-laboratory-networks/ears-net-data.

- Rice LB. Federal Funding for the Study of Antimicrobial Resistance in Nosocomial Pathogens: No ESKAPE. [cited 2025 Sep 10];1094–102. Available from: http://malaria.wellcome.ac.uk/.

- Montesinos I, Campos S, Ramos MJ, Ruiz-Garbajosa P, Riverol D, Batista N, et al. Estudio del primer brote por Enterococcus faecium vanA en Canarias. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin [Internet]. 2010 Aug [cited 2025 Jun 29];28(7):430–4. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20378209/.

- Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/initiatives/glass.

- Beg AZ, Khan AU. Genome analyses of blaNDM-4 carrying ST 315 Escherichia coli isolate from sewage water of one of the Indian hospitals. Gut Pathog [Internet]. 2018 May 24 [cited 2025 Sep 10];10(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29849769/.

- Hamza D, Dorgham S, Ismael E, El-Moez SIA, Elhariri M, Elhelw R, et al. Emergence of β-lactamase- A nd carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae at integrated fish farms. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control [Internet]. 2020 May 19 [cited 2025 Sep 10];9(1):1–12. Available from: https://aricjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13756-020-00736-3.

- Tavares M, Kozak M, Balola A, Sá-Correia I. Burkholderia cepacia Complex Bacteria: a Feared Contamination Risk in Water-Based Pharmaceutical Products. Clin Microbiol Rev [Internet]. 2020 Jul 1 [cited 2025 Sep 10];33(3). Available from: /doi/pdf/10.1128/cmr.00139-19?download=true.

- Peter S, Oberhettinger P, Schuele L, Dinkelacker A, Vogel W, Dörfel D, et al. Genomic characterisation of clinical and environmental Pseudomonas putida group strains and determination of their role in the transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Genomics [Internet]. 2017 Nov 10 [cited 2025 Aug 13];18(1):859. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5681832/.

- Corona-Nakamura AL, Miranda-Novales MG, Leaños-Miranda B, Portillo-Gómez L, Hernández-Chávez A, Anthor-Rendón J, et al. Epidemiologic Study of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Critical Patients and Reservoirs. Arch Med Res [Internet]. 2001 May 1 [cited 2025 Jun 29];32(3):238–42. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0188440901002673.

- Fazeli H, Akbari R, Moghim S, Esfahani B. Phenotypic characterization and PCR-Ribotypic profile of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from cystic fibrosis patients in Iran. Adv Biomed Res. 2013;2(1):18. [CrossRef]

- Riera E, Cabot G, Mulet X, García-Castillo M, del Campo R, Juan C, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa carbapenem resistance mechanisms in Spain: impact on the activity of imipenem, meropenem and doripenem. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy [Internet]. 2011 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Sep 29];66(9):2022–7. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Ruedas-López A, Alonso-García I, Lasarte-Monterrubio C, Guijarro-Sánchez P, Gato E, Vázquez-Ucha JC, et al. Selection of AmpC β-Lactamase Variants and Metallo-β-Lactamases Leading to Ceftolozane/Tazobactam and Ceftazidime/Avibactam Resistance during Treatment of MDR/XDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother [Internet]. 2022 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Sep 29];66(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34930034/.

- PÉREZ-VÁZQUEZ M, SOLA-CAMPOY PJ, ZURITA ÁM, ÁVILA A, GÓMEZ-BERTOMEU F, SOLÍS S, et al. Carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Spain: interregional dissemination of the high-risk clones ST175 and ST244 carrying blaVIM-2, blaVIM-1, blaIMP-8, blaVIM-20 and blaKPC-2. Int J Antimicrob Agents [Internet]. 2020 Jul 1 [cited 2025 Sep 29];56(1):106026. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0924857920301898?via%3Dihub.

- Hu Y, Shen W, Lin D, Wu Y, Zhang Y, Zhou H, et al. KPC variants conferring resistance to ceftazidime-avibactam in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. Microbiol Res [Internet]. 2024 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Sep 29];289:127893. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0944501324002945?via%3Dihub.

- Shields RK, Chen L, Cheng S, Chavda KD, Press EG, Snyder A, et al. Emergence of Ceftazidime-Avibactam Resistance Due to Plasmid-Borne blaKPC-3 Mutations during Treatment of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother [Internet]. 2017 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Sep 29];61(3). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28031201/.

- Faccone D, de Mendieta JM, Albornoz E, Chavez M, Genero F, Echegorry M, et al. Emergence of KPC-31, a KPC-3 Variant Associated with Ceftazidime-Avibactam Resistance, in an Extensively Drug-Resistant ST235 Pseudomonas aeruginosa Clinical Isolate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother [Internet]. 2022 Oct 26 [cited 2025 Sep 29];66(11). Available from: /doi/pdf/10.1128/aac.00648-22?download=true.

- Monroy-Pérez E, Herrera-Gabriel JP, Olvera-Navarro E, Ugalde-Tecillo L, García-Cortés LR, Moreno-Noguez M, et al. Molecular Properties of Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Causing Clinically Critical Infections. Pathogens [Internet]. 2024 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Sep 10];13(10):868. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0817/13/10/868/htm.

- Pang Z, Raudonis R, Glick BR, Lin TJ, Cheng Z. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mechanisms and alternative therapeutic strategies. Biotechnol Adv [Internet]. 2019 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Sep 10];37(1):177–92. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0734975018301976?via%3Dihub.

- Estepa V, Rojo-Bezares B, Azcona-Gutiérrez JM, Olarte I, Torres C, Sáenz Y. Caracterización de mecanismos de resistencia a carbapenémicos en aislados clínicos de Pseudomonas aeruginosa en un hospital español. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin [Internet]. 2017 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Sep 10];35(3):141–7. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0213005X16000318.

- Castanheira M, Mendes RE, Gales AC. Global Epidemiology and Mechanisms of Resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii-calcoaceticus Complex Clinical Infectious Diseases ® 2023;76(S2):S166-78.

- Lee CR, Lee JH, Park M, Park KS, Bae IK, Kim YB, et al. Biology of Acinetobacter baumannii: Pathogenesis, antibiotic resistance mechanisms, and prospective treatment options. Front Cell Infect Microbiol [Internet]. 2017 Mar 13 [cited 2025 Jun 29];7(MAR). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28348979/.

- Woodford N, Wareham DW, Guerra B, Teale C. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and non-Enterobacteriaceae from animals and the environment: an emerging public health risk of our own making? Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy [Internet]. 2014 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Jun 29];69(2):287–91. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen M, Joshi SG. Carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii, and their importance in hospital-acquired infections: a scientific review. J Appl Microbiol [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Sep 10];131(6):2715–38. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer Y, Wilharm G, Zander E, Wichelhaus TA, Göttig SG, Hunfeld KP, et al. Molecular characterization of blaNDM-1 in an Acinetobacter baumannii strain isolated in Germany in 2007. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy [Internet]. 2011 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Sep 10];66(9):1998–2001. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez CH, Nastro M, Famiglietti A. Carbapenemases in Acinetobacter baumannii. Review of their dissemination in Latin America. Rev Argent Microbiol [Internet]. 2018 Jul 1 [cited 2025 Sep 29];50(3):327–33. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29548732/.

- Li J, Li Y, Cao X, Zheng J, Zhang Y, Xie H, et al. Genome-wide identification and oxacillinase OXA distribution characteristics of Acinetobacter spp. based on a global database. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2023 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Sep 29];14:1174200. Available from: https://www.

- Kurihara MNL, Sales RO de, Silva KE da, Maciel WG, Simionatto S. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii outbreaks: a global problem in healthcare settings. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Sep 29];53:e20200248. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33174956/.

- WHO publishes list of bacteria for which new antibiotics are urgently needed [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 29]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/27-02-2017-who-publishes-list-of-bacteria-for-which-new-antibiotics-are-urgently-needed.

- Cantet F, Hervio-Heath D, Caro A, Le Mennec C, Monteil C, Quéméré C, et al. Quantification of Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio vulnificus and Vibrio cholerae in French Mediterranean coastal lagoons. Res Microbiol [Internet]. 2013 Oct [cited 2025 Jun 29];164(8):867–74. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23770313/.

- IGERE BE, ONOHUEAN H, Adomi PO, Bashiru A. Phenicol antibiotic resistance status amongst environmental non-O1/non-O139 Vibrio cholerae and Clinical O1/O139 Vibrio cholerae strains: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. The Microbe [Internet]. 2025 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Sep 24];8:100474. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2950194625002420?via%3Dihub.

- Maraki S, Christidou A, Anastasaki M, Scoulica E. Non-O1, non-O139 Vibrio cholerae bacteremic skin and soft tissue infections. Infect Dis (Lond) [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2025 Sep 24];48(3):171–6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26503346/.

- Rodríguez JY, Duarte C, Rodríguez GJ, Montaño LA, Benítez-Peñuela MA, Díaz P, et al. Bacteremia by non-O1/non-O139 Vibrio cholerae: Case description and literature review. Biomedica [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Sep 24];43(3):323–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37871571/.

- Al-Jassim N, Ansari MI, Harb M, Hong PY. Removal of bacterial contaminants and antibiotic resistance genes by conventional wastewater treatment processes in Saudi Arabia: Is the treated wastewater safe to reuse for agricultural irrigation? Water Res [Internet]. 2015 Apr 15 [cited 2025 Sep 10];73:277–90. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0043135415000640?via%3Dihub.

- Pessoa RBG, Oliveira WF de, Correia MT dos S, Fontes A, Coelho LCBB. Aeromonas and Human Health Disorders: Clinical Approaches. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2022 May 31 [cited 2025 Sep 10];13:868890. Available from: www.frontiersin.org.

- Fernández-Bravo A, Figueras MJ. An Update on the Genus Aeromonas: Taxonomy, Epidemiology, and Pathogenicity. Microorganisms 2020, Vol 8, Page 129 [Internet]. 2020 Jan 17 [cited 2025 Sep 10];8(1):129. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2607/8/1/129/htm.

- Dias C, Borges A, Saavedra MJ, Simões M. Biofilm formation and multidrug-resistant Aeromonas spp. from wild animals. J Glob Antimicrob Resist [Internet]. 2018 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Sep 10];12:227–34. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2213716517301765?via%3Dihub.

| Irrigation sampling point | Microorganism | CFU/100mL |

| B5 | Pseudomona aeruginosa | 4,1 x104 |

| B7 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1,5x104 |

| B8 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 2,9x102 |

| B8 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 6,7x100 |

| B18 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1,6x105 |

| B20 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1,6x102 |

| B11 | Acinetobacter baumannii | 1,2x106 |

| B15 | Acinetobacter baumannii | 6,0x104 |

| B19 | Acinetobacter baumannii | 7,3x104 |

| B11 | Acinetobacter pittii | 1,9x105 |

| B12 | Acinetobacter pittii | 4,6x107 |

| B13 | Acinetobacter pittii | 6,5x106 |

| Irrigation sampling point | Microorganism | CFU/100mL |

| B8 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 6,7x100 |

| B10 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 3x101 |

| B11 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1,5x105 |

| B12 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 4,1x107 |

| B17 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 5x100 |

| B18 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 6x102 |

| B19 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1,8x105 |

| B7 | Escherichia coli | 1,3x100 |

| B9 | Escherichia coli | 3,3x100 |

| B10 | Escherichia coli | 5x101 |

| B11 | Escherichia hermannii | 5,7x106 |

| B12 | Escherichia hermanii | 8,8x106 |

| B13 | Escherichia hermanii | 1,3x106 |

| B14 | Escherichia hermanii | 6,0x107 |

| B15 | Escherichia hermannii | 8,3x105 |

| B13 | Enterobacter cloacae | 3,0x106 |

| B14 | Enterobacter cloacae | 6,0x107 |

| Irrigation sampling point | Microorganism | CFU/100mL |

| B11 | Enterococcus faecium | 9,3x100 |

| B1 | Enterococcus faecalis | 5,2x101 |

| B2 | Enterococcus faecalis | 3x103 |

| B3 | Enterococcus faecalis | 3x103 |

| B5 | Enterococcus faecalis | 7,7x102 |

| B11 | Enterococcus faecalis | 1,3x102 |

| B14 | Enterococcus faecalis | 2,8x103 |

| B18 | Enterococcus faecalis | 7,3x101 |

| B19 | Enterococcus faecalis | 2,4x104 |

| B20 | Enterococcus faecalis | 2,3x102 |

| Island | Irrigation sampling point | Microorganism | Resistant mechanism | Number of isolates |

| Fuerteventura | B1 | Aeromonas punctata | Intrinsic/other resistance mechanism | 2 |

| Fuerteventura | B1 | Pseudomonas mendocina | Intrinsic/other resistance mechanism | 1 |

| Fuerteventura | B2 | Burkholderia multivorans | Intrinsic/other resistance mechanism | 1 |

| Lanzarote | B6 | Aeromonas sobria | Intrinsic/other resistance mechanism | 1 |

| Lanzarote | B8 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | MBL | 1 |

| Lanzarote | B8 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | KPC | 1 |

| Lanzarote | B8 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | ESBL + Loss of porin | 1 |

| Lanzarote | B8 | Burkholderia cepacia | Intrinsic/other resistance mechanism | 1 |

| Lanzarote | B9 | Pseudomonas putida | Intrinsic/other resistance mechanism | 1 |

| Lanzarote | B9 | Aeromonas salmonicida | Intrinsic/other resistance mechanism | 1 |

| Lanzarote | B10 | Pseudomonas stutzeri | Intrinsic/other resistance mechanism | 1 |

| Lanzarote | B10 | Pseudomonas fluorescens | Intrinsic/other resistance mechanism | 1 |

| Gran Canaria | B11 | Acinetobacter pittii | Oxacilinasa | 2 |

| Gran Canaria | B11 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | OXA-48 | 1 |

| Gran Canaria | B11 | Acinetobacter baumanii | Oxacilinasa | 1 |

| Gran Canaria | B11 | Acinetobacter calcoacetius | MBL | 1 |

| Gran Canaria | B11 | Aeromonas salmonicida | Intrinsic/other resistance mechanism | 1 |

| Gran Canaria | B12 | Acinetobacter pittii | Intrinsic/other resistance mechanism | 1 |

| Gran Canaria | B12 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Intrinsic/other resistance mechanism | 1 |

| Gran Canaria | B12 | Acinetobacter lwoffii | Oxacilinasa | 1 |

| Gran Canaria | B14 | Escherichia hermanii | OXA48 + ESBL | 2 |

| Gran Canaria | B14 | Enterobacter cloacae | AmpC+ loss of porin | 1 |

| Gran Canaria | B14 | Sphingomonas paucimobilis | Intrinsic/other resistance mechanism | 1 |

| Gran Canaria | B14 | Enterobacter cloacae | KPC | 2 |

| Gran Canaria | B15 | Escherichia hermannii | ESBL+loss of porin | 2 |

| Gran Canaria | B15 | Acinetobacter baumanii | Oxacilinasa | 1 |

| Gran Canaria | B15 | Acinetobacter calcoacetius | MBL | 1 |

| Tenerife | B16 | Pseudomonas putida | Intrinsic/other resistance mechanism | 1 |

| Tenerife | B18 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | KPC | 1 |

| Tenerife | B18 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Intrinsic/other resistance mechanism | 1 |

| Tenerife | B19 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Intrinsic/other resistance mechanism | 1 |

| Tenerife | B19 | Acinetobacter baumanii | Oxacilinasa | 1 |

| Tenerife | B19 | Aeromonas hydrophila | Intrinsic/other resistance mechanism | 1 |

| Tenerife | B20 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | MBL | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).