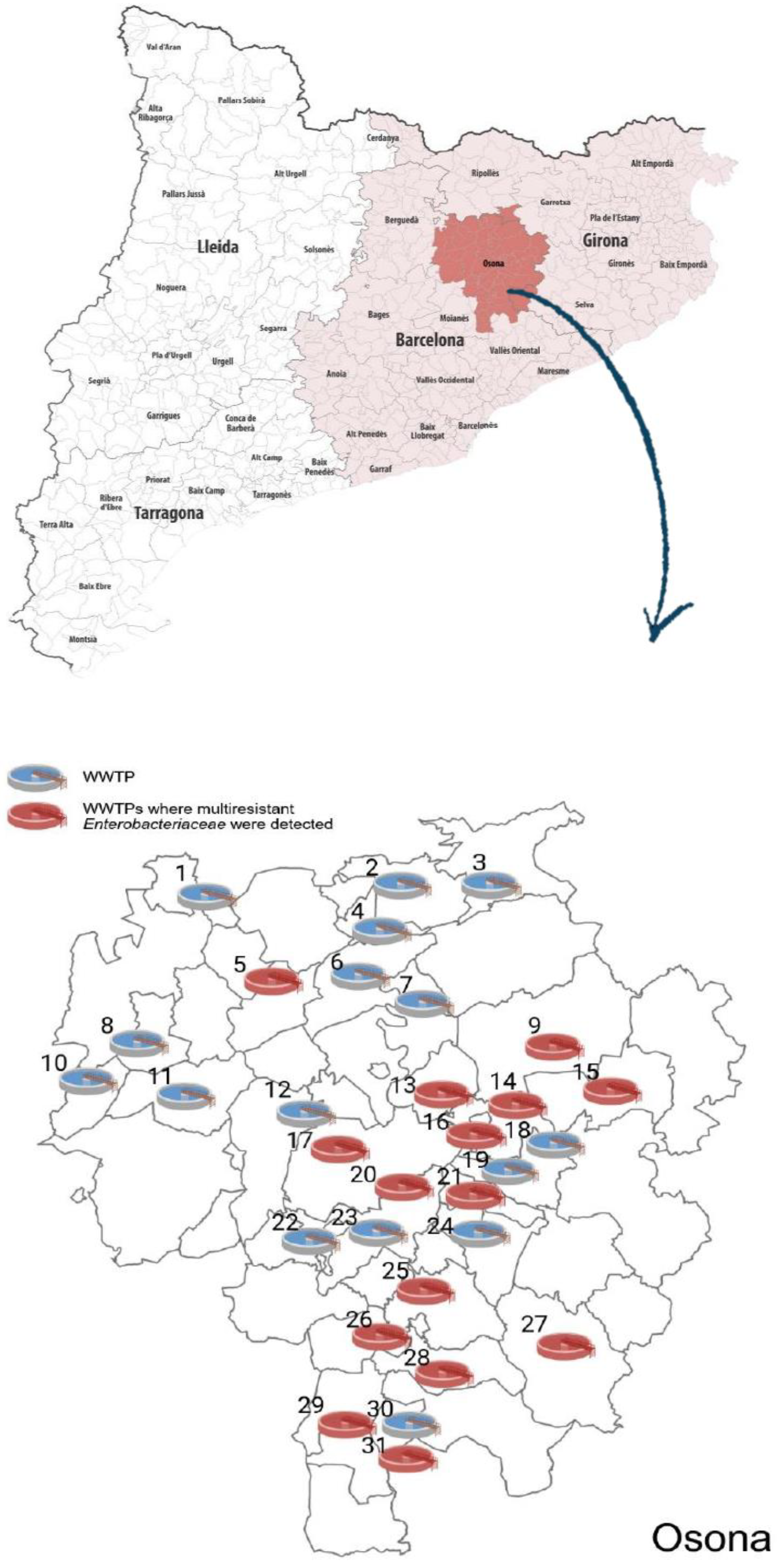

1. Introduction

Enterobacteriaceae, particularly

Escherichia coli, are opportunistic pathogens found as commensals in the intestinal tract of humans and animals and associated with a variety of community- and hospital-acquired infections [

1]. Furthermore, these microorganisms can contaminate many different environments, through fecal transmission, subsequently entering water and food consumed by humans [

2].

Nowadays, an issue of increasing concern to public health authorities is the spread of multiresistant extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) - and carbapenemase-producing

Enterobacteriaceae in the environment, mainly through aquatic ecosystems [

3]. Aquatic habitats enable the convergence of bacteria from human, animal and environmental sources, promoting the horizontal transfer of antibiotic-resistance genes (ARGs) and mobile genetic elements [

4].

Current wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) are not designed to fully remove micropollutants such as antibiotics, antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) and ARGs. As a result, these biological components can easily end up in WWTP effluents discharged into rivers and which then become efficient vehicles for spreading drug-resistant microorganisms over long distances [

5,

6]. In addition, in WWTP settings, ESBL-producing

Enterobacteriaceae can be spread through bioaerosols, potentially exposing plant workers and the inhabitants of surrounding areas to harmful microorganisms in the air [

2].

Previous studies have revealed the presence of ESBL- and carbapenemase-producing

Enterobacteriaceae in samples collected from rivers, WWTP effluents and hospital sewage systems. However, there are few epidemiological studies on this issue in the Spanish context [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

Given that Osona, a county in the Catalan province of Barcelona in northeastern Spain, is a region with a high density of pig fattening farms [

12], it was conjectured that it might have a high percentage of multiresistant

Enterobacteriaceae in its aquatic ecosystems.

The aims of our study were (a) to analyse the prevalence of ESBL- and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in water samples from the river Ter, the main river flowing through the county, and its principal tributaries, the rivers Gurri and Méder, as well as samples from all of the WWTPs in the county; (b) to genetically characterise any ESBL- and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae strains detected; and (c) to compare ESBL-producing E. coli strains in the natural environment with those coming from human communities to determine whether they shared a common origin.

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Characterisation of Multiresistant Enterobacteriaceae from WWTP and River Samples

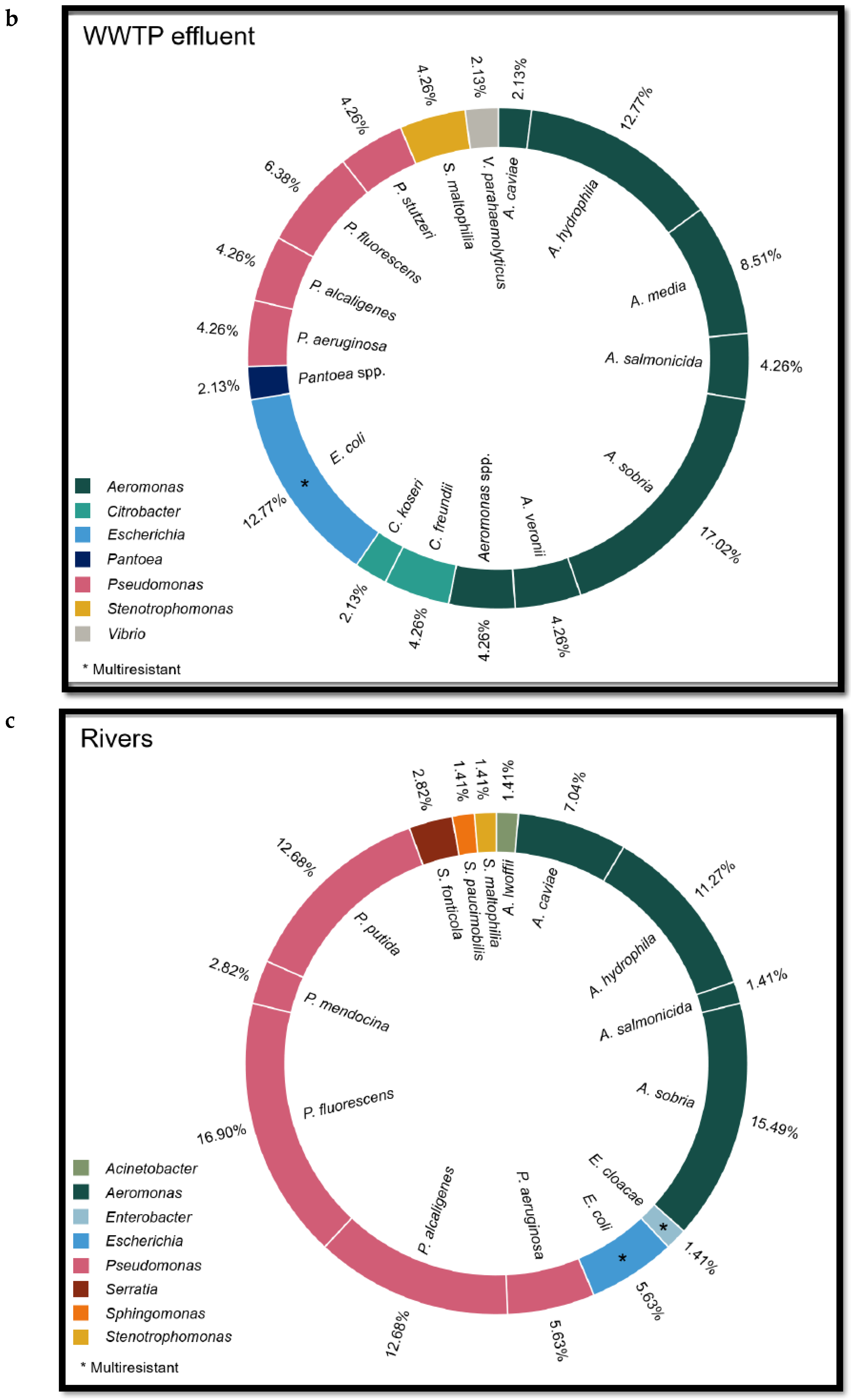

Multiresistant

Enterobacteriaceae were detected at 15 out of 31 (48.4%) WWTPs (see map in

Figure 1). Twelve strains of ESBL-producing

Escherichia coli and one strain each of OXA-48-producing

Klebsiella pneumoniae, SHV-1-producing

Klebsiella oxytoca and ESBL-producing

Klebsiella pneumoniae were isolated in the influent wastewater samples, while in the effluent samples were isolated 6 strains of ESBL-producing

E. coli, of which one was not related to strains in the influent.

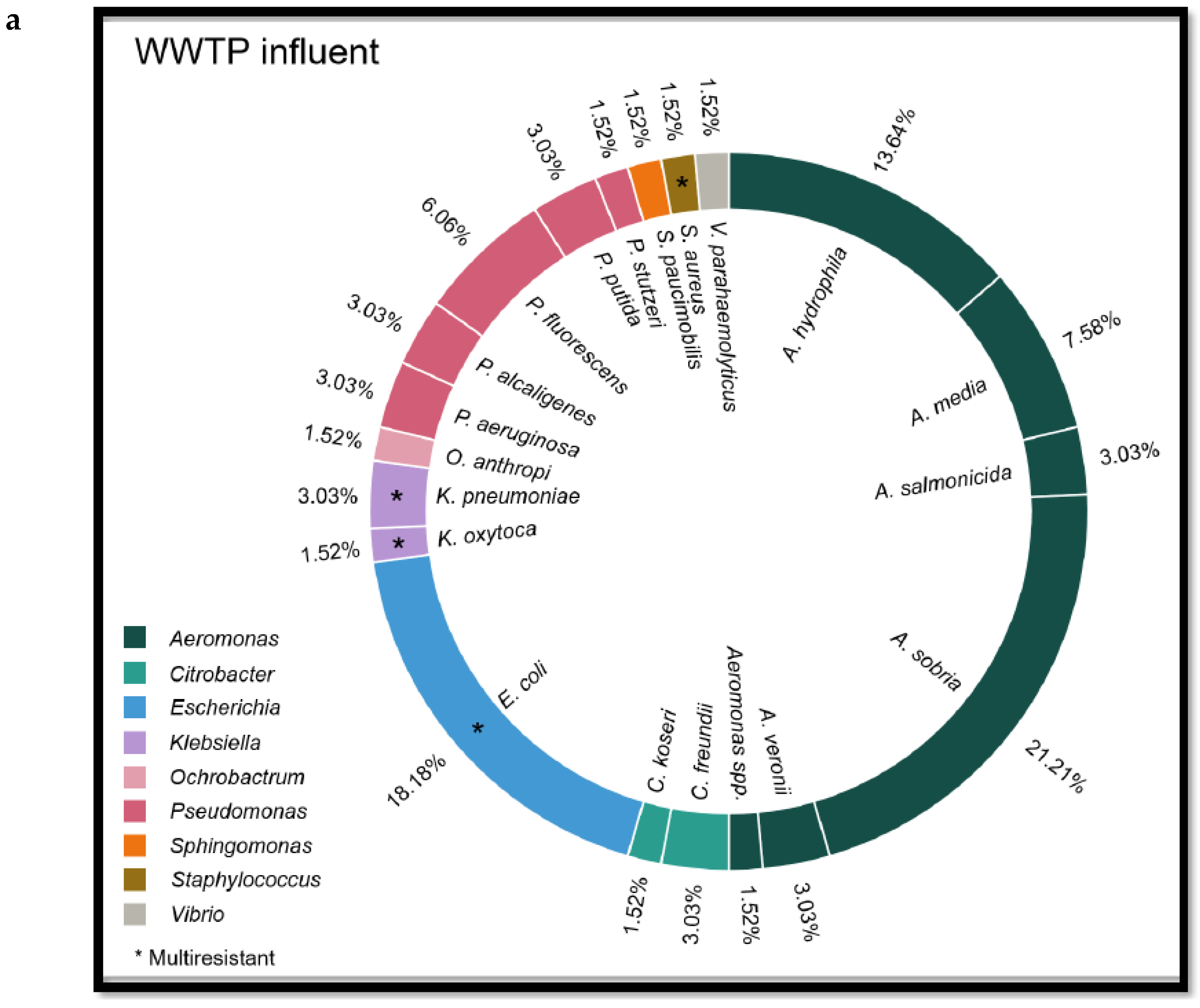

Other Enterobacteriaceae identified in both influent and effluent were the following: Aeromonas sobria (n = 22), Aeromonas hydrophila (n = 15), Aeromonas media (n = 9), Pseudomonas fluorescens (n = 7), Aeromonas salmonicida (n = 5), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 5), Pseudomonas alcaligenes (n = 4), Citrobacter freundii (n = 4), Aeromonas veroni (n = 4), Pseudomonas stutzeri (n = 3), Citrobacter koseri (n = 2), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (n = 2), Sphingomonas paucimobilis (n = 1) and Pantoeae (n = 1).

In addition, by chance, a strain of mecC-carrying methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) ST2676 was isolated from a WWTP influent.

Regarding river water, 4 strains of ESBL-producing

E. coli and 1 strain of VIM-producing

E. cloacae complex were isolated from the 29 river samples (17.2%). Other

Enterobacteriaceae identified were

Pseudomonas fluorescens (n = 12),

Aeromonas sobria (n = 8),

Aeromonas hydrophila (n = 7),

Pseudomonas putida (n = 5),

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 4),

Pseudomonas alcaligenes (n = 2),

Aeromonas caviae (n = 2) and

Serratia fonticola (n = 2) (See

Figure 2, which lists the

Enterobacteriaceae detected in influent and effluent from WWTPs as well as rivers, and see

Table 1 in Appendix 2 for the genome sequencing of several strains).

2.2. Analysis of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae Strains from WWTP and River Samples

Two strains of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae were detected, one (an OXA-48-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae) in the influent of a WWTP and the other (a VIM-producing E. cloacae complex) in the river Ter.

With respect to the OXA-48-producing K. pneumoniae, the ST was 101 and the plasmids detected were Col440I, ColpVC, IncFIB(K), IncFII(pKP91), IncL and IncR. An analysis of ARGs showed the presence of the following: blaOXA-48, blaOXA-1, blaTEM-1B, blaSHV-106, blaCTX-M-15, aac(6')-Ib-cr, aac(3)-IId, sul2, OqxB, OqxA, dfrA14, tet(D)and fosA. For the VIM-producing E. cloacae complex, the ST was 45 and the plasmids were Col(pHAD28), IncFIB(pECLA), IncFII(pECLA), IncHI2, and IncHI2A. In this case the following ARGs were detected: blaVIM-1, blaACT-15, blaTEM-1B, blaOXA-1, blaCTX-M-9, ant (2'')-Ia, aac(6')-Ib3, aac(6')-Ib-cr, qnrB5, qnrA1, qnrB81, qnrB19, sul1, sul2, dfrA14, dfrB1, tet(A), catB3 and mcr-9.

Figure 2.

Species of Enterobacteriaceae family isolated from WWTP influent (a) and effluent (b) and river water (c) samples.

Figure 2.

Species of Enterobacteriaceae family isolated from WWTP influent (a) and effluent (b) and river water (c) samples.

2.3. Analysis of ESBL-Producing E. coli and K. pneumoniae from WWTP and River Samples

A strain of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae ST35 was isolated with the following ARGs: blaCTX-M-15, blaOXA-1, blaSHV-33, aac(6')-Ib-cr, OqxB, sul2, fosA6, tet(A) and catB3.

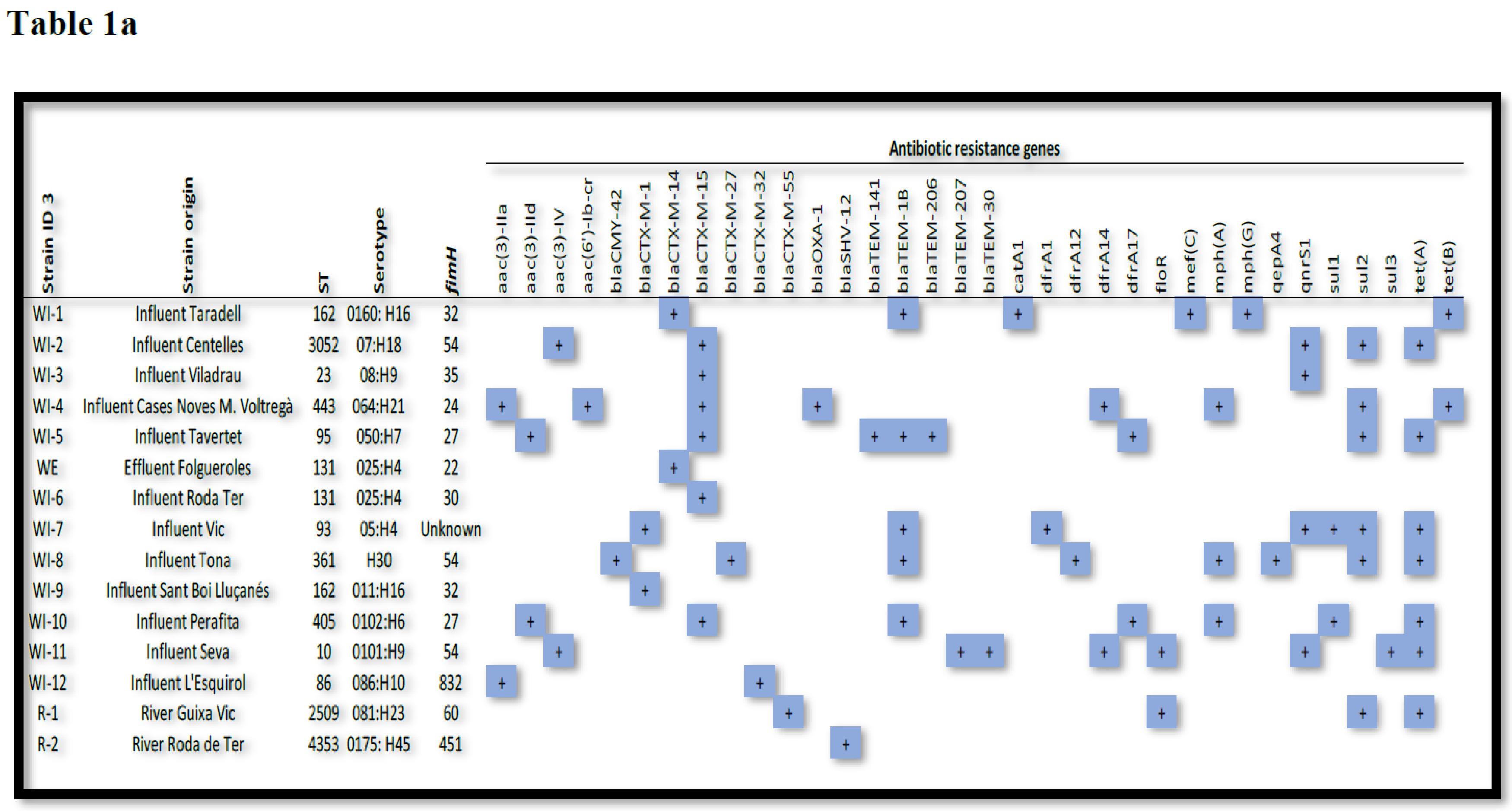

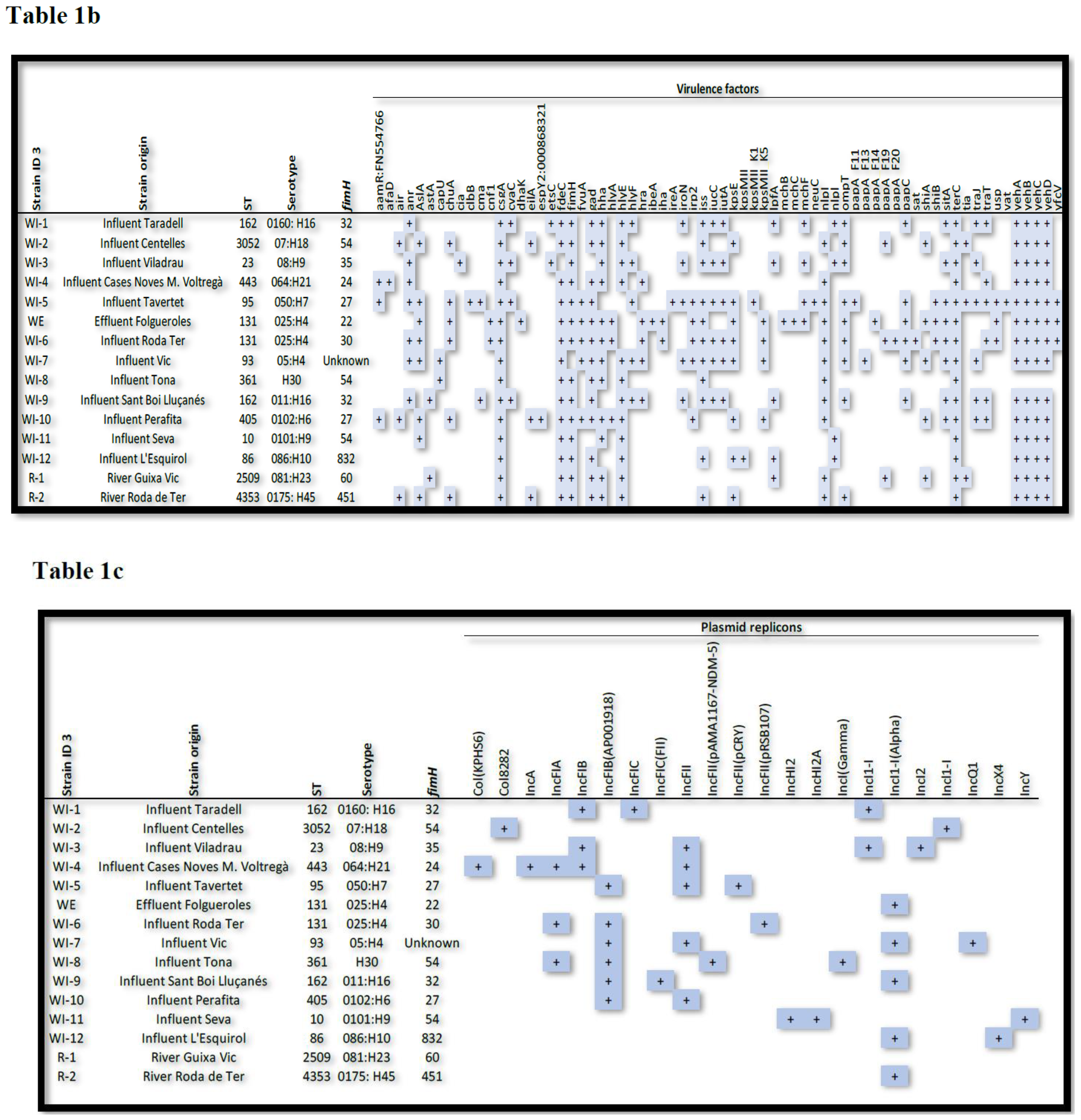

Thirteen different STs were identified among the 15 isolates of ESBL-producing

E. coli (see

Table 1, which shows ESBL-producing

E. coli strains with their respective ST, ARGs, plasmidon replicons and virulence factors) with ST131 and ST162 detected in two isolates, and ST10, ST23, ST86, ST93, ST95, ST361, ST405, ST443, ST2509 (river), ST3052 and ST4353 (river) each detected in only one isolate.

An analysis of the ARG content of the isolates showed that the β-lactam resistance genes blaCTX-M-15 (n = 6) and blaTEM-1B were the most prevalent (n = 5), followed by blaCTX-M-14 and blaCTX-M-1 detected in two isolates. BlaCTX-M-27, blaCTX-M-32, blaCTX-M-42, blaCTX-M-55, blaSHV-12, blaTEM-30, blaTEM-141, blaTEM-206, blaTEM-207 and blaOXA-1 genes were detected in only one isolate.

Ciprofloxacin resistance was related to the presence of qnrS1 (n = 4), followed by aac(6’)-Ib-cr and qepA4 (n = 1), and aminoglycoside resistance was related to aac(3)-IV (n = 2), followed by aac(3)-IId, aac(3)-IIa plus aac(6')-Ib-cr and aac(3)-IIa (n = 1).

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole resistance was mainly associated with the combinations of sul (n = 8) and drfA genes (n = 6). Sul2 alone was present in two isolates and sul1 plus sul2 in one. In addition, dfrA14 and dfrA17 were detected in two isolates and dfrA1 and dfrA12 in one. Furthermore, seven strains had the tet(A) gene and two had the tet(B) gene.

Plasmid Finder analysis confirmed 22 different replicons, of which the most common were IncFIB(AP001918) (n = 6), IncFII (n = 5), IncI1-I(Alpha) (n = 4), IncFIA (n = 3) and IncFIB (n = 3). Most of the isolates contained more than one replicon; one isolate harboured five, while five isolates had three, three isolates had four and two isolates had three replicons. In one isolate, one replicon was found it.

Virulence factor (VF) analysis showed the presence of the following VFs among the isolates: 0–10 VFs (n = 1); 11–25 VFs (n = 7); 26–40 (n = 7).

Table 1.

ESBL-producing

E. coli strains with their respective origin, ST, antibiotic resistance genes (

Table 1a), virulence factors (

Table 1b) and plasmid replicons (

Table 1c).

Table 1.

ESBL-producing

E. coli strains with their respective origin, ST, antibiotic resistance genes (

Table 1a), virulence factors (

Table 1b) and plasmid replicons (

Table 1c).

2.4. Identification and Characterisation of Multiresistant Enterobacteriaceae from Rectal Swabs

Of the 382 rectal swab samples obtained, 39 (10.2%) revealed strains of multiresistant Enterobacteriaceae, of which 26 (66.7%) were ESBL-producing E. coli, followed by ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae (5; 12.8%), ESBL-producing Proteus mirabilis (2; 5.1%), AmpC-producing Citrobacter freundii (2; 5.1%) and to a lesser extent AmpC-producing E. coli, AmpC-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa, multiresistant Pseudomonas luteola and multiresistant Acinetobacter haemolyticus (1 each, together representing 10.3%).

Regarding ESBL-producing E. coli and AmpC-producing E. coli (see Table 2 in Appendix), 16 different STs were identified among the 27 isolates, with ST131 (n = 9), ST69 (n = 3) and ST410 (n = 2) being the most common, followed by ST10, ST12, ST101, ST155, ST162, ST224, ST457, ST609, ST744, ST1193, ST2179, ST3205 and ST12150 (1 each).

An analysis of the ARG content of the isolates showed that the β-lactam resistance genes blaTEM-1B (n = 10), blaCTX-M15 (n = 9) and blaCTX-M-27 (n = 7) were the most prevalent, followed by blaCTX-M-65 (n = 3), blaOXA-1 (n = 3), blaCTX-M-14 (n = 2), blaCTX-M-32 (n = 2), blaTEM-1A (n = 2), blaOXA-10 (n = 2), and blaCTX-M-1, blaSHV-12, blaCMY-2, blaDHA-1, blaTEM-30, blaTEM-1C, blaTEM-126, blaTEM-186 and blaTEM-207 (1 each).

Ciprofloxacin resistance was related to the presence of qnrS1 (n = 5) and aac(6’)-Ib-cr (n = 3), followed by qnrS2 and qnrB4 (1 each) and aminoglycoside resistance was related to aac(6')-Ib-cr (n = 3), followed by aac(3)-IV, ant(2'')-Ia, aac(3)-IId, aac(3)-IIa and aac(3)-IIa (1 each).

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole resistance was mainly associated with the combinations of drfA (n = 19) and sul (n = 23) genes. Sul2 alone was present in four isolates and sul1 plus sul2 in five. In addition, dfrA17 (n = 8), dfrA1(n = 4) and dfrA14 (n = 3) were the most frequent combinations, followed by dfrA5, dfrA7, dfrA12 and dfrA36 (1 each).

Plasmid Finder analysis confirmed 35 different replicons, the most common being IncFIB(AP001918) (n = 22), Col156 (n = 12), IncFIA (n = 11), IncFII(pRSB107) (n = 9), IncFIC(FII) (n = 8) and Col (BS512) (n = 5).

VF analysis of the isolates yielded the following results: 0–10 VFs (n = 0); 11–25 VFs (n = 6); 26–40 (n = 21).

3. Discussion

Aquatic ecosystems have been recognised as an important medium for the spreading of multiresistant microorganisms, because the discharge of wastewater from human and animal sources into the environment can lead to the bacterial contamination of water bodies. If that water and/or sewage sludge is then used for agriculture, the soil and then food products grown in it also become contaminated, facilitating the spread of these dangerous microorganisms among human populations [

13].

In this study, we analysed 62 wastewater samples, including influent and effluent, from 31 WWTPs located throughout the county of Osona in Catalonia. Home to some 164,000 inhabitants, the county is characterised by a high density of pig, goat and sheep farms [

14]. Our analysis detected multiresistant

Enterobacteriaceae in almost half of these WWTPs.

The number of WWTPs tested was significantly higher than in previous Spanish studies (one in [

7]); two in [

8]; two in [

12]; 21 in [

4] and among the species identified, ESBL - producing

E. coli were the most significant (12 in wastewater influent and 6 in wastewater effluent) and therefore 50% of the strains remained in the effluent, indicating a high likelihood that they would end up in rivers and agriculture.

ESBL-producing

E. coli clones ST131 and ST162 were the most prevalent. The high risk ST131 clone in particular is well known to cause both community-and healthcare-associated infections worldwide [

13,

14]. No overall data are available about the proportions of ST131 isolates (with or without ESBL production) in

E. coli populations released into the environment, however; it has been detected in WWTP effluent [

15] and both WWTP influent and effluent [

16] in the Czech Republic and also in Switzerland [

10] and Japan [

13]. ESBL-producing

E. coli ST162 was also detected recently in wastewater in the Czech Republic [

16].

Another important finding was the isolation of a strain of OXA-48-producing

K. pneumoniae ST101 in the influent of a WWTP. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of this strain at a WWTP in Spain, though it has been detected in other countries such as Finland and Romania [

17,

18]. Although the proportion of this strain in the wastewater analysed in our study was very low, its presence is worrying because this documents the first step of these genes out of the clinical setting into the environment and potentially from there back into the human community [

19].

The detection of VIM-producing

E. cloacae ST45 in a sample taken from the river Ter was of particular interest because as far as we know this is the first report of this strain isolated in river waters in Spain. It should be noted that the location where the river water was sampled was close to a slaughterhouse as well as a sizable flock of ducks, which suggest a possible animal reservoir for the microorganism. This finding differs from those reported in [

20], where carbapenemase-producing

Enterobacteriaceae were recovered from sediment samples, as were two strains of

E. cloacae, one positive for KPC-2 and the other positive for IMI-2. Moreover, this point on the Ter is 27 km from the village where a mecC-carrying MRSA was isolated from samples taken from humans, animals and wastewater [

21].

This study differed somewhat in its methodology from other studies carried out in the Spanish context, and our results in terms of ESBL-producing

E. coli environmental strain counts also differ from other findings. For example, our data showed

blaCTX-M-15 and

blaTEM-1B to be the most prevalent β-lactam resistance genes, followed to a lesser extent by

blaCTX-M-14 and

blaCTX-M-1, while [

4] detected mainly

blaCTX-M-14 and

blaCTX-M-1 and [

22] detected

blaCTX-M-1. The CTX-M-15 enzyme has been identified in hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients and also in pets, in which CTX-M-15 was the most prevalent CTX-M enzyme [

23], as well as in migratory birds [

24].

Concerning human strains in the general population, out of the 382 participants included in our study, 39(10.2%) showed evidence of rectal carriage of multiresistant

Enterobacteriaceae, of which 66.7% were ESBL-producing

E. coli, with the most prevalent antibiotic-resistant genes being mainly ST131,

blaTEM-1B,

blaCTX-M15 and

blaCTX-M-27. Moreover, these first two genes (

blaTEM-1B and

blaCTX-M15) are in line with our most prevalent antibiotic resistance genes of environmental strains. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae were not detected. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study showing such a level of prevalence in rural community settings. In the meta-analysis by [

25] the pooled prevalence of ESBL- producing

E. coli intestinal carriage in Europe was lower (6%) than in all other continents, but a subgroup meta-analysis carried out separately for every three-year period by every 3 years of the study showed an increasing trend, with a much higher carriage rate in recent years.

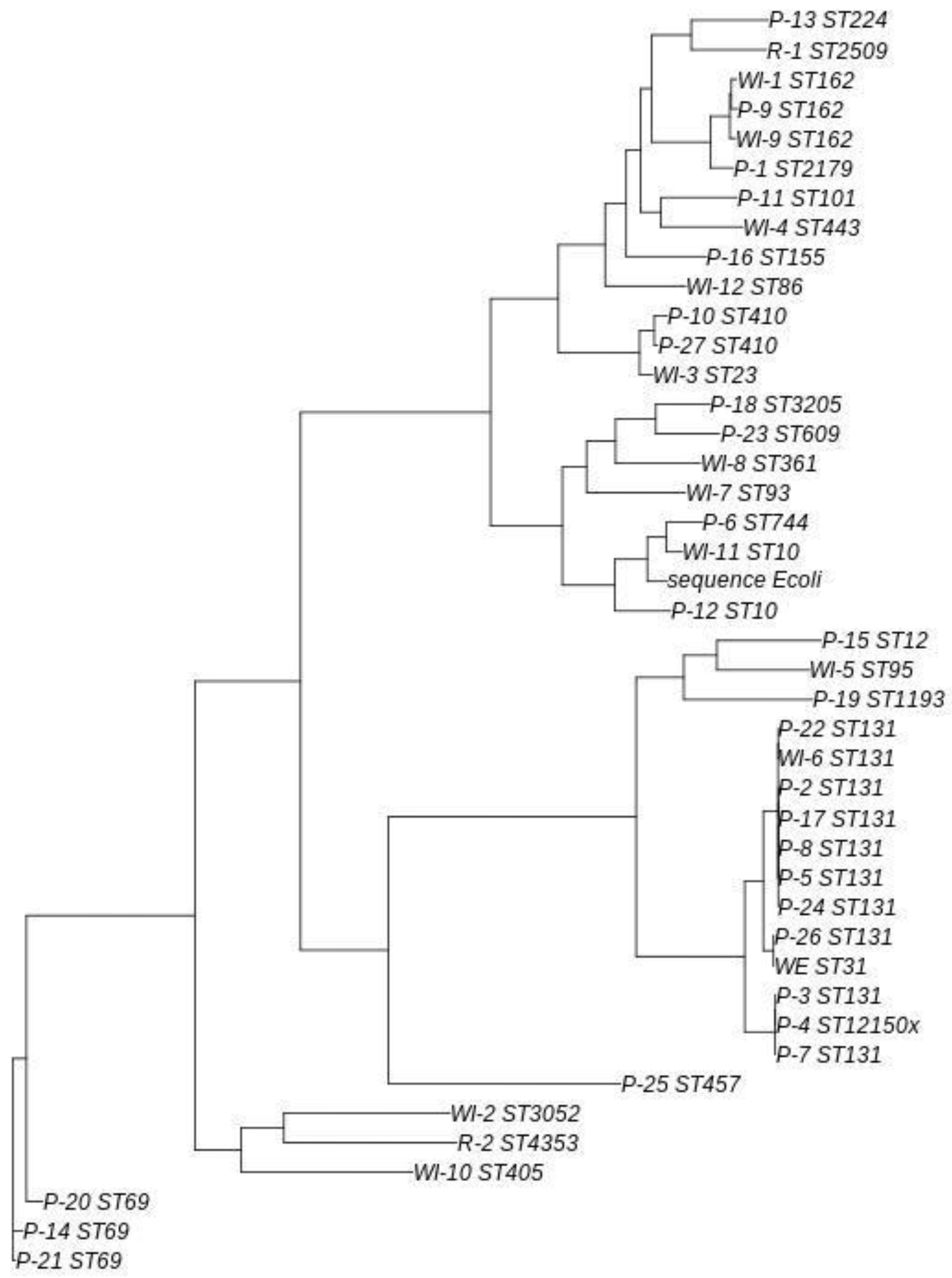

Comparing ESBL- producing

E. coli environmental and human community strains through a phylogenetic tree (see

Figure 3), all samples identified as ST131 and the sample identified as ST12150x clustered together with a common ancestor, although they were grouped into three distinct subgroups. The largest subgroup consisted of patients 2, 5, 8, 17, 22 and 24, along with WWTP influent sample 6. Four of these 6 patients resided within a 9-km range of this WWTP and the remaining 2 lived 22 km away. In the analysis conducted, no significant evolutionary differences were detected among these strains. The second subgroup comprised patients 3, 4, and 7, with differences that were nearly undetectable. The final subgroup included patient 26 and the WWTP effluent, with no evolutionary differences detected between them. This patient resided 17 km from the WWTP in question.

The subgroup comprising WWTP influent 6 and patients 2, 5, 8, 17, 22 and 24 showed a close evolutionary relationship to the subgroup consisting of patient 26 and the WWTP effluent.

Other ST types were detected in more than one sample, but ST131 was the only type in which no evolutionary differences were detected. Patient 9 and WWTP influents 1 and 9 shared the same ST (ST162), although slight differences were observed, with patient 9 and WWTP influent 1 being the closest evolutionary match. A similar pattern was observed in the samples isolated from patients 10 and 27, both of which exhibited ST410.

An interesting case was observed with the cluster made up of WWTP influent 11 and patients 6 and 12. WWTP 11 presented a ST10, patient 6 a ST744 and patient 12 a ST10. Although patient 12 and WWTP influent 11 shared the same ST, the ST in the sample from patient 6 was closer to the ST in the sample isolated from WWTP 11.

The present study has several limitations. The main limitation was that the fact we were not able to recover two ESBL-producing E. coli strains from rivers for genomic sequencing as well as five ESBL-producing E. coli strains from effluents because initially the strains were phenotypically similar to the corresponding influent strains and we did not keep those strains. Furthermore, we could not perform the genomic sequencing of all Enterobacteriaceae isolated. In addition, the results obtained in this study are from single samples taken at each location, so the presence and abundance of the different strains may be affected by the period of the year when sampling was carried out.

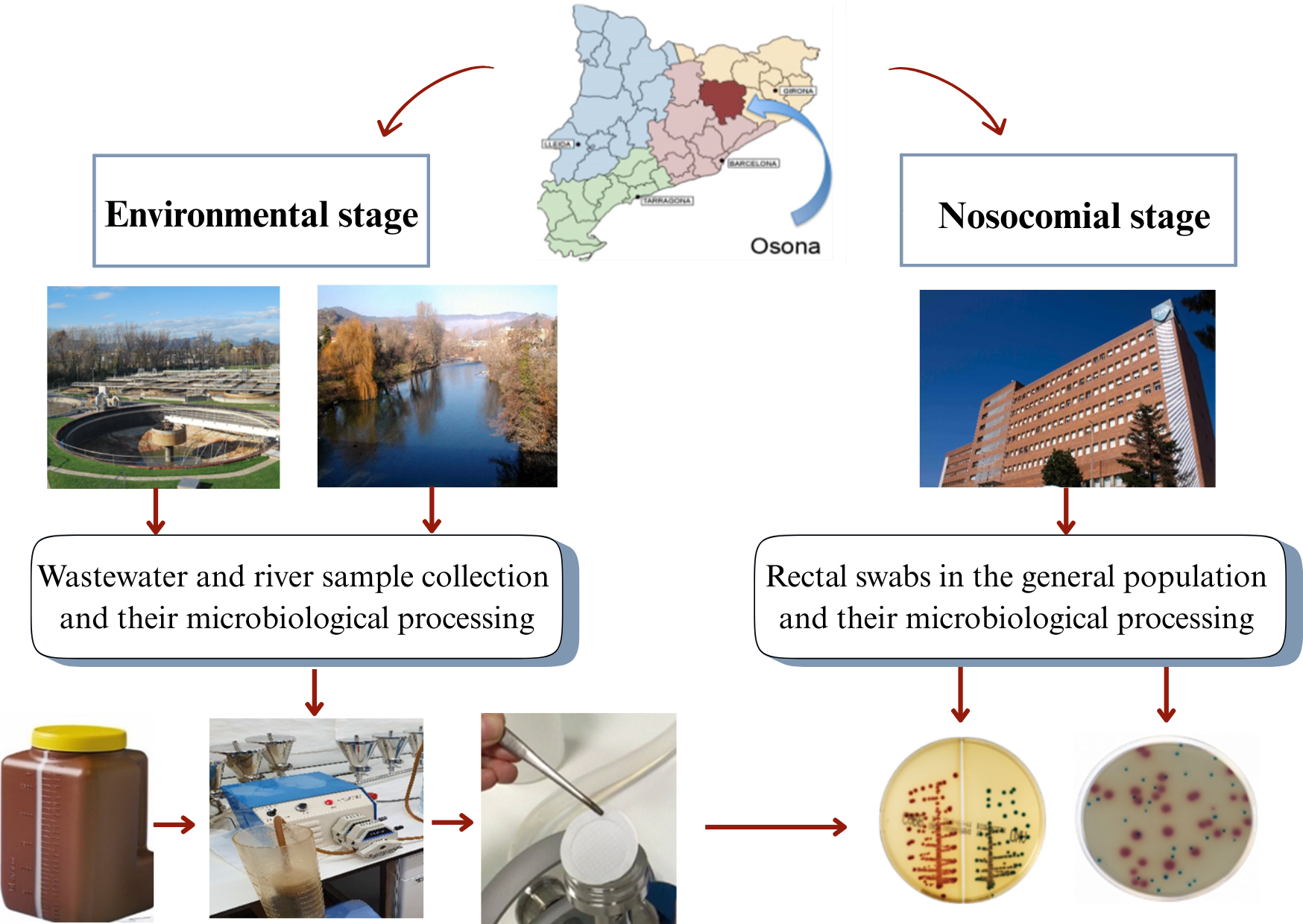

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Collection of Aquatic Samples

From November 2020 to July 2023, samples were collected from influent wastewater and outgoing treated effluent at all 31 WWTPs in Osona, yielding 62 samples in total. In addition, between November 2020 and December 2021, water samples from the rivers Ter, Gurri and Mèder were sampled at 11 different locations in sections of their respective courses where they pass through the main municipalities of Osona (coordinates for these locations are listed in Appendix 1). At some sites, samples were taken on more than one occasion, to yield a total of 29 samples altogether. In all cases sampling was carried out when river flows were normal (i.e., not during or after heavy rain) in order to prevent variation in hydrological conditions from affecting the results [

26].

Influent was defined as untreated wastewater from households, hospitals, farms or pharmaceutical industries entering the treatment plants, while effluent was defined as fully treated water exiting the plants and therefore in principle apt for reuse [

27].

4.2. Microbiological Analysis of Environmental Samples

The water was collected in a sterile 2-litre container. Once in the microbiology laboratory, the water was filtered using a peristaltic pump and polycarbonate 47 mm and 0.2 μm pore filters. The filter was then placed in a sterile container with 2-3 mL of sterile saline and vortexed. Next, the serum was seeded with a 10 μL loop on selective plates of MacConkey agar, CHROMID®ESBL (bioMerieux) and CHROMID®CARBA SMART (bioMerieux). Finally, the plates were incubated at 35°–37 °C for 24–48 hours.

The antimicrobial susceptibility of all the enterobacterial isolates recovered in CHROMID®ESBL (bioMerieux) and CHROMID®CARBA SMART (bioMerieux) was studied by the microdilution method using Vitek2 (BioMerieux®, Spain), following EUCAST guidelines.

Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase- and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae strains were frozen at -20 °C and then sent to Germans Trias i Pujol Research Institute for whole genome sequencing.

4.3. Rectal Carriage of Multiresistant-Enterobacteriaceae Among the General Population

From November 2020 to 2021, during one week in every four months all patients admitted to the University Hospital of Vic, the capital city of Osona, were screened within 24 hours of admission for the presence of multiresistant-Enterobacteriaceae by means of rectal swabs. Screening data from all patients who gave their consent to the use of their results for purposes of this study were included.

4.4. Microbiological Analysis of Rectal Swabs

Rectal swabs were also plated on selective media, namely MacConkey agar, CHROMID®ESBL (bioMerieux) and CHROMID®CARBA SMART (bioMerieux). Extended-spectrum betalactamase and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae strains were frozen at -20 °C and then sent to Germans Trias i Pujol Research Institute for whole genome sequencing.

4.5. DNA Extraction and Quantification

DNA extraction of all isolated bacterial strains was performed using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Extractions were quantified by fluorometry (Quantus, Promega).

4.6. Whole Genome Sequencing

DNA extractions were normalized at 0.2 ng/µl for library preparation with the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, USA). After the amplification step, the samples were purified with CleanNGS beads (CleanNA, Waddinxveen, Netherlands). Quality control of libraries was performed using a 2200 TapeStation System (Agilent). Libraries were individually quantified by fluorimetry (Quantus), pooled and run on the MiSeq system (at 10pM final concentration containing 10% PhiX) and a million reads per sample were obtained. Sequencing was performed at the Genomic Core Facility at the Centre de Regulació Genòmica in Barcelona.

Raw sequences were imported as paired-end sequences into the KBase platform [

28]. Reads were de novo assembled using SPAdes assembler v3.13.0, with default parameters, to obtain contigs as FASTA files. These contigs were used to genotype isolates using Multi Locus Sequence Typing (MLST) [

29] and other tools available from the Center for Genomic Epidemiology (Technical University of Denmark), such as ResFinder version 4.7.2, FimTyper version 1.0, PlasmidFinder version 2.1 and VirulenceFinder version 2.0.

The phylogenetic tree was built using the Realphy online tool from whole genome sequence data from all

Escherichia coli, whether obtained from clinical or environmental sources. The

Escherichia coli strain K-12 substrain MG1655 was used as a reference to build the tree and was obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information [

30].

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrates the presence of ESBL- and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in water from the river Ter, which flows through an area of Catalonia, Spain, that is characterized by intensive animal husbandry. Noteworthy findings are the first detection of a VIM-producing E. cloacae ST45 strain and the first detection of an OXA-48-producing K. pneumoniae strain in WWTP influent in this region. Also significant is the fact that we isolated ESBL-producing E. coli in almost the half of all WWTPs in the county.

Likewise, the presence of multiresistant Enterobacteriaceae in WWTP effluent as revealed here points to insufficient clearance during treatment processes. These findings underscore the need for improved wastewater management to prevent the release of resistant bacteria into natural water bodies and thereby reduce the risk of subsequent human infection. Finally, several environmental and human strains of the multiresistant microorganisms identified in this study have a common ancestor, which suggests a similar origin and the resistance may have originated in one environment and then spread to the other.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Appendix 1 with location of 11 points where water samples were taken from the rivers Ter, Gurri and Mèder in Osona, Catalonia, Spain and

Appendix 2 showing

Table 1 and Table 2 are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

J.D.d.l.R.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing; N.P.-N.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing; M.N.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation; J.S.-P.: Methodology, Supervision, Validation; A.V.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation; E.A.: Resources, Validation, Visualization; M.B.: Methodology, Supervision, Validation; T.N.B.: Methodology, Supervision, Validation; L.P.-B.: Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation; Ó.M.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation; E.R.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partially funded by Laboratorios Menarini S.A.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was carried out following the rules of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, which was revised in 2013, and was approved by the Consell Comarcal d’Osona and Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitari de Vic in June 2020 (Nº 2020138).

Informed Consent Statement

All the participants provided their informed and written consent to participate in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the present study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to all the WWTP workers in the region of Osona for generously facilitating our labours. We would also like to thank Analia Treveset and Michael Kennedy-Scanlon for style-checking this manuscript and Silvia Díez de los Ríos González for style-checking the graphical abstract. Germans Trias i Pujol Research Institute are included in the CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya. The preliminary results of this work were presented in part at the XXIV Congreso Nacional de la Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica (SEIMC), online format from 5-11 June 2021 (oral communication, presentation code 061); the 31st European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID), online format from 9-12 July 2021 (Poster, presentation number: 334); XXX Jornades de la Societat Catalana de Malalties Infeccioses i Microbiologia Clínica, Sitges, Barcelona, 15-16 October 2021 (Poster); the 32nd European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID), Lisbon, Portugal, 23-26 April 2022 (Poster, presentation number: 1083, selected for “Virtual Walkthrough sessions”); XXV Congreso Nacional de la Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica (SEIMC), Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2-4 June 2022 (Poster, presentation code 0304); and the 35th Congress of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ePoster number P3745).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ARG |

Antibiotic resistant gene |

| E. coli |

Escherichia coli |

| ESBL |

Extended-spectrum β-lactamase |

| K. pneumoniae |

Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| MLST |

Multi Locus Sequence Typing |

| MRSA |

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

|

| SEIMC |

Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica |

| ST |

SpaType |

| VF |

Virulence factor |

| VIM |

Verona integron-encoded metallo-beta-lactamase |

| WWTP |

Wastewater treatment plant |

References

- Mairi, A.; Pantel, A.; Sotto, A.; Lavigne, J.P.; Touati, A. OXA-48-like carbapenemases producing Enterobacteriaceae in different niches. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 37(4), 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Said, L.; Jouini, A.; Alonso, C.A.; Klibi, N.; Dziri, R.; Boudabous, A.; et al. Characteristics of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)- and pAmpC beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae of water samples in Tunisia. Sci. Total. Environ. 2016, 550, 1103–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurfluh, K.; Hächler, H.; Nüesch-Inderbinen, M.; Stephan, R. Characteristics of extended-spectrum β-lactamase- and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates from rivers and lakes in Switzerland. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79(9), 3021–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojer-Usoz, E.; González, D.; García-Jalón, I.; Vitas, A.I. High dissemination of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae ineffluents from wastewater treatment plants. Water. Res. 2014, 56, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masarikova, M.; Sukkar, I.; Jamborova, I.; Medvecky, M.; Papousek, I.; Literak, I.; et al. Antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli from treated municipal wastewaters and Black-headed Gull nestlings on the recipient river. One. Heal. 2024, 19, 100901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabri, N.A.; Schmitt, H.; Van Der Zaan, B.; Gerritsen, H.W.; Zuidema, T.; Rijnaarts, H.H.M.; et al. Prevalence of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in a wastewater effluent-receiving river in the Netherlands. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8(1), 102245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser-Ali, M.; Aja-Macaya, P.; Conde-Pérez, K.; Trigo-Tasende, N.; Rumbo-Feal, S.; Fernández-González, A.; et al. Emergence of Carbapenemase Genes in Gram-Negative Bacteria Isolated from the Wastewater Treatment Plant in A Coruña, Spain. Antibiotics. 2024, 13(2), 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pino-Hurtado, M.S.; Fernández-Fernández, R.; Campaña-Burguet, A.; González-Azcona, C.; Lozano, C.; Zarazaga, M.; et al. A Surveillance Study of Culturable and Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacteria in Two Urban WWTPs in Northern Spain. Antibiotics. 2024, 13(10), 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynaga, E.; Navarro, M.; Vilamala, A.; Roure, P.; Quintana, M.; Garcia-Nuñez, M.; et al. Prevalence of colonization by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 in pigs and pig farm workers in an area of Catalonia, Spain. BMC. Infect. Dis. 2016, 16(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggel, M.; Hoehn, S.; Frei, A.; Dassler, K.; Jans, C.; Stephan, R. Dissemination of ESBL-producing E. coli ST131 through wastewater and environmental water in Switzerland. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 337, 122476. [Google Scholar]

- Díez de los Ríos, J.; Hernández-Meneses, M.; Navarro, M.; Montserrat, S.; Perissinotti, A.; Miró, J.M. Staphylococcus caprae: an emerging pathogen related to infective endocarditis. Clin.Microbiol.Infect. 2023, 29(9), 1214–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovejero, C.M.; Delgado-Blas, J.F.; Calero-Caceres, W.; Muniesa, M.; Gonzalez-Zorn, B. Spread of mcr-1-carrying Enterobacteriaceae in sewage water from Spain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72(4), 1050–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibuki, R.; Nishiyama, M.; Mori, M.; Baba, H.; Kanamori, H.; Watanabe, T. Characterization of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolated from municipal and hospital wastewater in Japan. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 32, 145–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas-Chanoine, M.H.; Bertrand, X.; Madec, J.Y. Escherichia coli st131, an intriguing clonal group. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27(3), 543–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolejska, M.; Frolkova, P.; Florek, M.; Jamborova, I.; Purgertova, M.; Kutilova, I.; et al. CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli clone B2-O25b-ST131 and Klebsiella spp. isolates in municipal wastewater treatment plant effluents. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011, 66(12), 2784–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidova-Gerzova, L.; Lausova, J.; Sukkar, I.; Nesporova, K.; Nechutna, L.; Vlkova, K.; et al. Hospital and community wastewater as a source of multidrug-resistant ESBL-producing Escherichia coli. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13(May), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heljanko, V.; Tyni, O.; Johansson, V.; Virtanen, J.P.; Räisänen, K.; Lehto, K.M.; et al. Clinically relevant sequence types of carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae detected in Finnish wastewater in 2021–2022. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2024;13(1),1–11. [CrossRef]

- Popa, L.I.; Gheorghe, I.; Barbu, I.C.; Surleac, M.; Paraschiv, S.; Măruţescu, L.; et al. Multidrug Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae ST101 Clone Survival Chain From Inpatients to Hospital Effluent After Chlorine Treatment. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 610296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galler, H.; Feierl, G.; Petternel, C.; Reinthaler, F.F.; Haas, D.; Grisold, A.J.; et al. KPC-2 and OXA-48 carbapenemase-harbouring Enterobacteriaceae detected in an Austrian wastewater treatment plant. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20(2), O132–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedra-Carrasco, N.; Fàbrega, A.; Calero-Cáceres, W.; Cornejo-Sánchez, T.; Brown-Jaque, M.; Mir-Cros, A.; et al. Carbapenemase-producing enterobacteriaceae recovered from a Spanish river ecosystem. PLoS One. 2017, 12(4), e0175246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porrero, M.C.; Valverde, A.; Fernández-Llario, P.; Díez-Guerrier, A.; Mateos, A.; Lavín, S.; et al. Staphylococcus aureus carrying mecc gene in animals and Urban Wastewater, Spain. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20(5), 899–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monge-Olivares, L.; Peñalva, G.; Pulido, M.R.; Garrudo, L.; Ángel Doval, M.; Ballesta, S.; et al. Quantitative study of ESBL and carbapenemase producers in wastewater treatment plants in Seville, Spain: a culture-based detection analysis of raw and treated water. Water. Res. 2025, 281, 123706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantón, R.; González-Alba, J.M.; Galán, J.C. CTX-M enzymes: Origin and diffusion. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohsin, M.; Raza, S.; Schaufler, K.; Roschanski, N.; Sarwar, F.; Semmler, T.; et al. High prevalence of CTX-M-15-Type ESBL-Producing E. coli from migratory avian species in Pakistan. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezabih, Y.M.; Sabiiti, W.; Alamneh, E.; Bezabih, A.; Peterson, G.M.; Bezabhe, W.M.; et al. The global prevalence and trend of human intestinal carriage of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in the community. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76(1), 22–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proia, L.; Anzil, A.; Subirats, J.; Borrego, C.; Farrè, M.; Llorca, M.; et al. Antibiotic resistance along an urban river impacted by treated wastewaters. Sci. Total.Environ.2018,628–629,453–66. doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.02.

- Limayem, A.; Wasson, S.; Mehta, M.; Pokhrel, A.R.; Patil, S.; Nguyen, M.; et al. High-Throughput Detection of Bacterial Community and Its Drug-Resistance Profiling From Local Reclaimed Wastewater Plants. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkin, A.P.; Cottingham, R.W.; Henry, C.S.; Harris, N.L.; Stevens, R.L.; Maslov, S.; et al. KBase: The United States department of energy systems biology knowledgebase. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36(7), 566–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.V.; Cosentino, S.; Rasmussen, S.; Friis, C.; Hasman, H.; Marvig, R.L.; et al. Multilocus sequence typing of total-genome-sequenced bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50(4), 1355–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertels, F.; Silander, O.K.; Pachkov, M.; Rainey, P.B.; Van Nimwegen, E. Automated reconstruction of whole-genome phylogenies from short-sequence reads. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014, 31(5), 1077–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).