1. Introduction

The environment is a receiver of all waste of human or animal origin in the form of feces, urine and pharmaceutical or sewage effluent that may carry with it selected resistant bacteria and antibiotic residues into soil, water or air [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Wastewater treatment plants (WWTP) are considered a major source of bacteria carrying resistant genes into the environment [

6]. Although it is well known that wastewater treatment systems are not designed to remove chemical pollutants and do not completely remove the pathogenic bacteria, studying environmental contamination levels from WWTP will lead to a deeper understanding of how antibiotic-resistant infections emerge and how to regulate the use of treated wastewater. Bacteria in the environment and in contact with effluent wastewater, are exposed to antimicrobials in sub-optimal or repeated exposures that provide a platform for resistance development [

4,

7,

8].

In addition, pathogenic antibiotic resistant bacteria contaminating the environment from wastewater treatment plants may interact with other environmental microbiota and transmit resistance and virulence genes [

7]. Resistant bacterial species in the environment may transmit to humans and also to domesticated and wild animals causing incurable diseases thereby amplifying the antimicrobial resistance (AMR) problem further [

9].

Antibiotic resistance is a growing concern worldwide and continually emerging due to many contributing factors that differ from place to place. Microorganisms perpetually mutate and evolve, making it difficult to treat diseases, thereby affecting most of the gains achieved in the management of infectious diseases [

10]. In 2019, about 1.27 million deaths were referable to AMR bacteria in sub-Saharan Africa [

11]. In Malawi, a 20-year study at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital (QECH) between 1998 and 2017 reported an increase in AMR associated with bloodstream infections, a major cause of death in patients [

12]. A more recent study conducted at the same hospital in Malawi revealed that patients with bloodstream infections caused by bacteria resistant to third generation cephalosporins have longer hospital stays and are linked to higher fatality rates [

13]. Persistence of AMR is attributed to the increased use of antimicrobials in the human [

14] and animal sectors [

15] and also the release of effluent from wastewater treatment systems, animal farms and pharmaceutical industries into the environment that may select for antibiotic resistance [

1,

2,

3]. In order to help in the development of preventative interventions, extensive and comprehensive data on antimicrobial resistant pathogens, their effect on human and animal health and the associated consequences are being generated [

12,

16,

17]. Relatively little is known about AMR in the environment, which is a more expansive and varied domain. Therefore, there is a need for environmental surveillance to generate evidence for resistant microbes in the environmental sector and also to define emergence and transmission pathways. This study investigated the presence of ESBL-producing pathogens in effluent from WWTPs in Blantyre, Malawi to complement the data already being collected in the human and animal sectors. The study focused on isolating ESBL-producing

E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacter cloacae, determining the varied antibiotic susceptibilty profiles of the identified bacteria and assessing the association with some environmental factors on resistant ESBL-producing organisms from two WWTPs in Blantyre city. Enterobacterales such as

E. coli, Klebsiella and

Enterobacter are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in humans [

18]. These bacteria are also part of the ESKAPE (

Enterococcus faecium,

Staphylococcus aureus,

Klebsiella pneumoniae,

Acinetobacter baumannii,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and

Enterobacter species) group of pathogens known for increasing rates of AMR and hospital acquired infections [

19,

20]. ESKAPE pathogens, especially those that are able to produce beta-lactamases have developed resistance to most of the antibiotic classes and are a major cause of high disease burden and death due to limited treatment options [

20,

21,

22].

2. Results

2.1. Isolation and Identification of ESBL Organisms in WWTPs

A total of 288 effluent samples were collected between 3

rd April, 2023 and 27

th March, 2024 and 281/288 samples (97.57%) yielded one or more presumptive ESBL isolates. Of these, 7 contained ESBL

E.coli only (2.5%), 16 samples contained ESBL

Enterobacter cloacae only (5.7%), 36 samples contained ESBL

E. coli and ESBL

Enterobacter cloacae (12.8%), 172 contained ESBL

E. coli and ESBL

Enterobacter cloacae (61.2%) and 41 samples contained ESBL

E.coli and other confirmed organisms or organisms with low discrimination profiles (14.6%). The remaining 8 samples contained other ESBL growth that was neither pink nor blue (2.8%); these colonies were not processed further as shown in

Table 1.

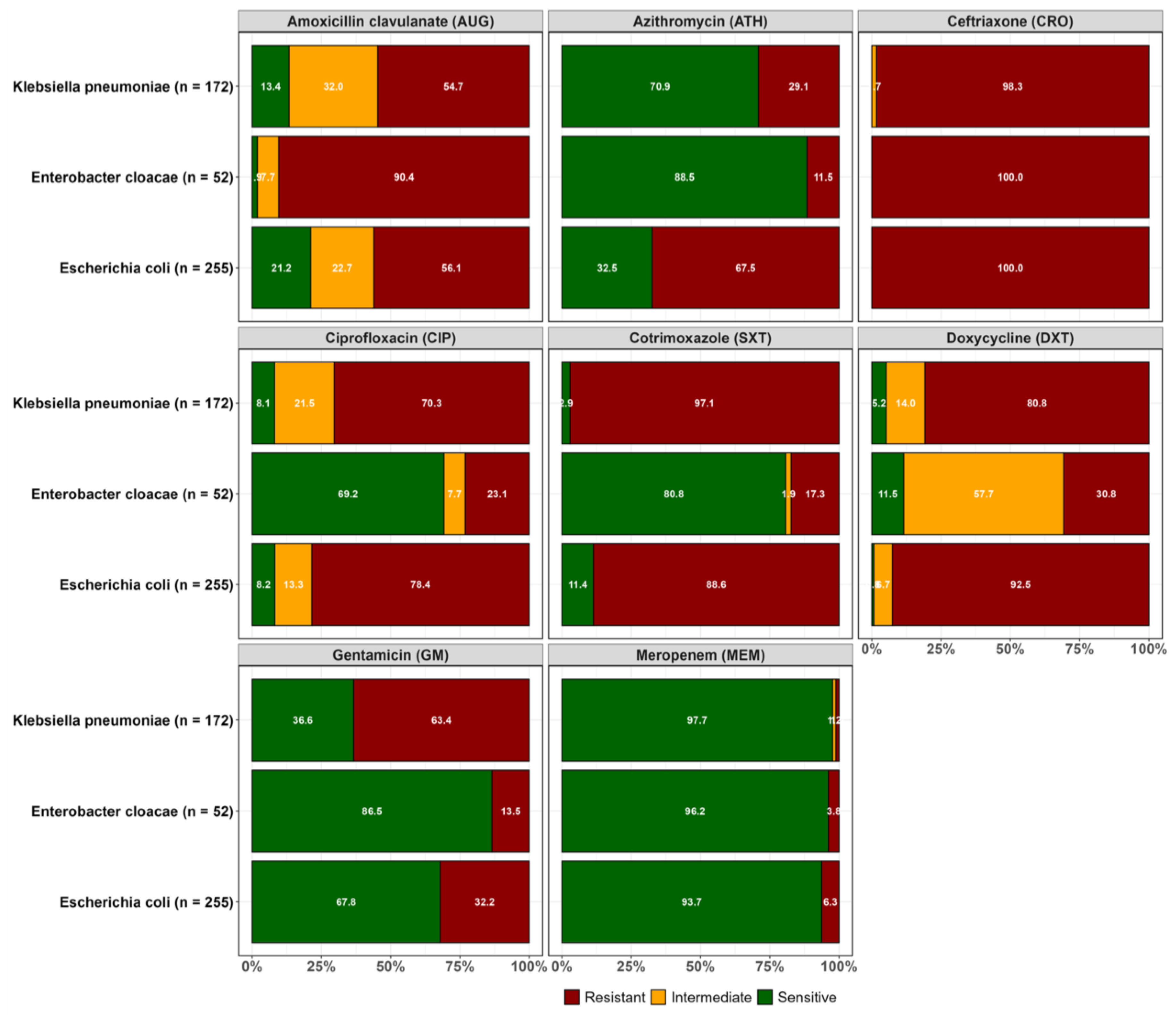

2.2. Resistance Profiles of Isolated ESBL-Producing E. coli, K. pneumoniae and Enterobacter cloacae

Overall, resistance to the third-generation cephalosporin ceftriaxone was common in the three ESBL producing pathogens, as expected. Considering each species individually, ESBL

E. coli isolates showed higher resistance to ceftriaxone (100.0%), followed by doxycycline (92.5%), cotrimoxazole (88.6%), ciprofloxacin (78.4%) and gentamicin (32.2%). Relatively lower resistance rates were observed to meropenem in ESBL

E. coli (6.3%). For ESBL

Klebsiella pneumoniae, high resistance rate was observed for ceftriaxone (98.3%) followed by doxycycline (80.8%), cotrimoxazole (97.1%) and ciprofloxacin (70.3%). However, lower resistance was observed to azithromycin (29.1%) and meropenem (1.2%). ESBL

Enterobacter cloacae were more susceptible to most of the antibiotics that were tested except for ceftriaxone (100%), a third generation cephalosporin, and amoxicillin clavulanate (90.4%) to which intrinsic resistance has been reported (

Figure 1).

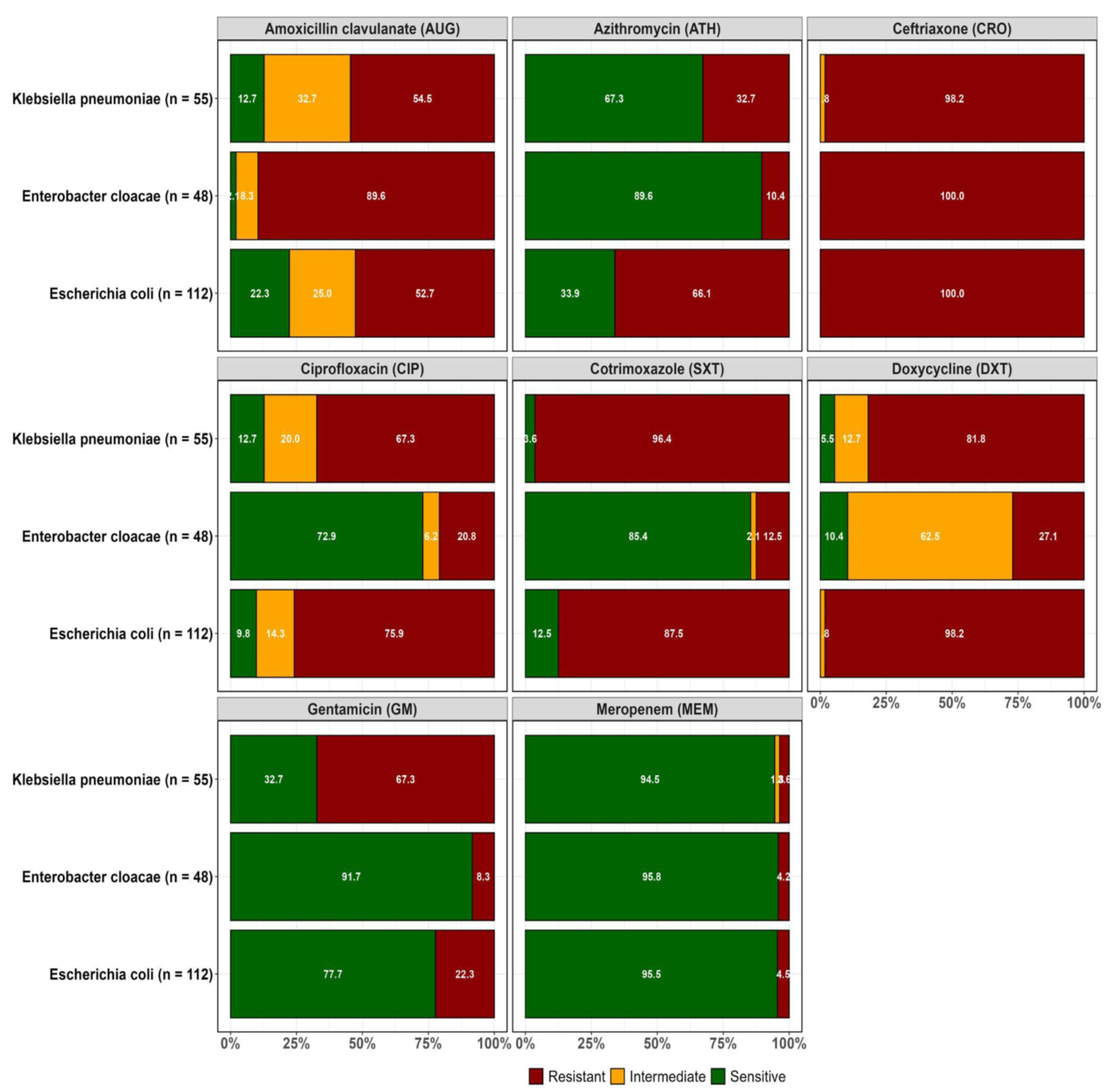

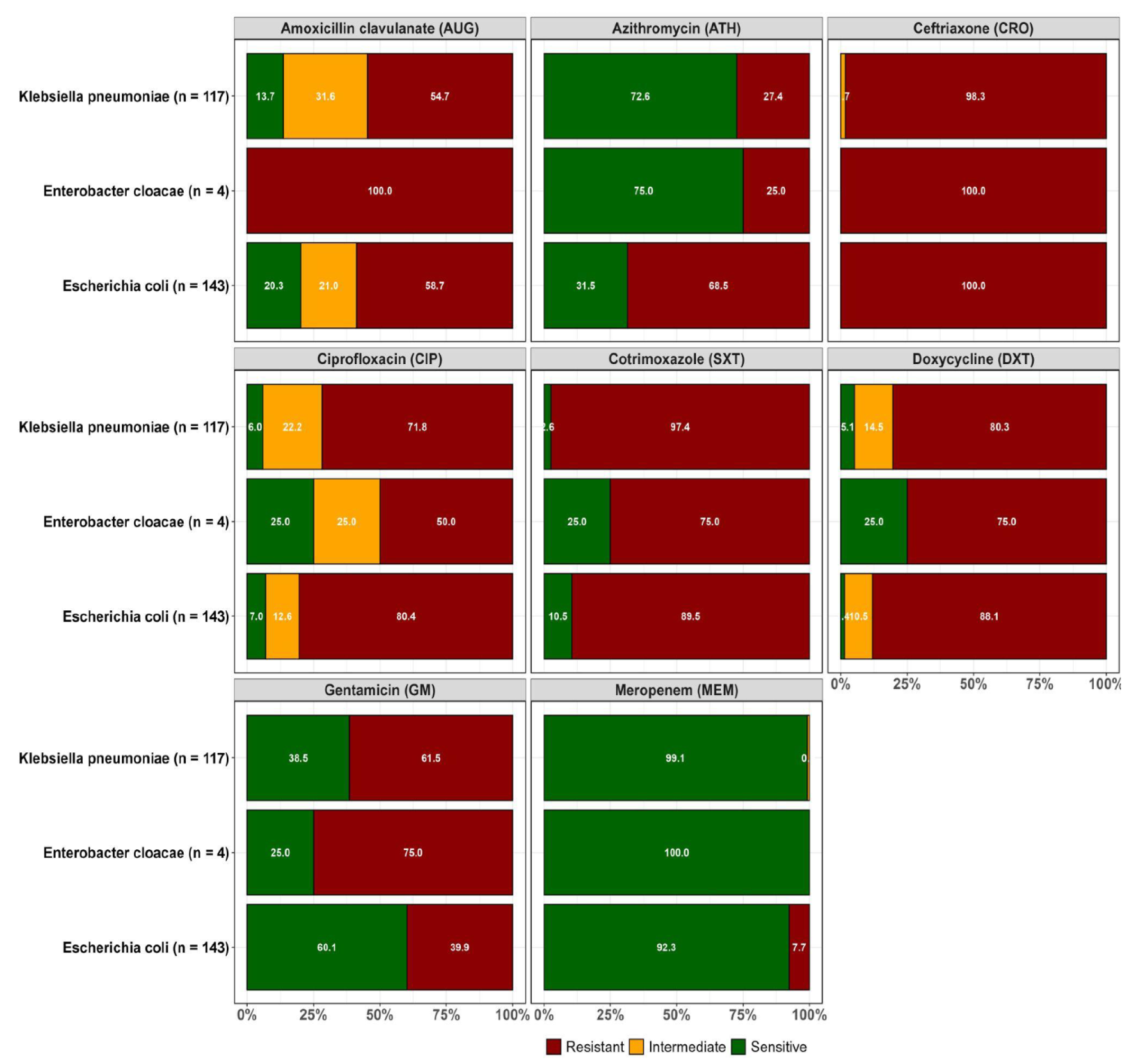

Resistance to at least one of the antibiotics tested was orbserved in the confirmed ESBL-positive isolates recovered from both WWTPs as highlighted in

Figure 2A and 2B.

Prevalence of multiple antibiotic-resistance phenotype and multiple antibiotic resistance index ESBL E. coli, ESBL K. pneumoniae and ESBL E. cloacae

A total of 350 (73.1%) isolates were resistant to three or more classes of antibiotics. Among the multiple resistant isolates that were observed, 51.4% (180/350) were ESBL

E. coli, 43.1% (151/350) were ESBL

K. pneumoniae and 5.4% (19/350) were ESBL

E. cloacae. The most prevalent multiple antibiotic-resistant phenotypes (MARP) among the isolates was AUG-SXT-DXT-CIP-GM-ATH-CRO (55, 15.7%). Six ESBL

E. coli isolates were resistant to all 8 antibiotics that were tested. The multiple antibiotic resistance index (MARI) ranged from 0.4 to 1 with 29.1% of the MARP isolates having a MARI of 0.6 (

Table 2).

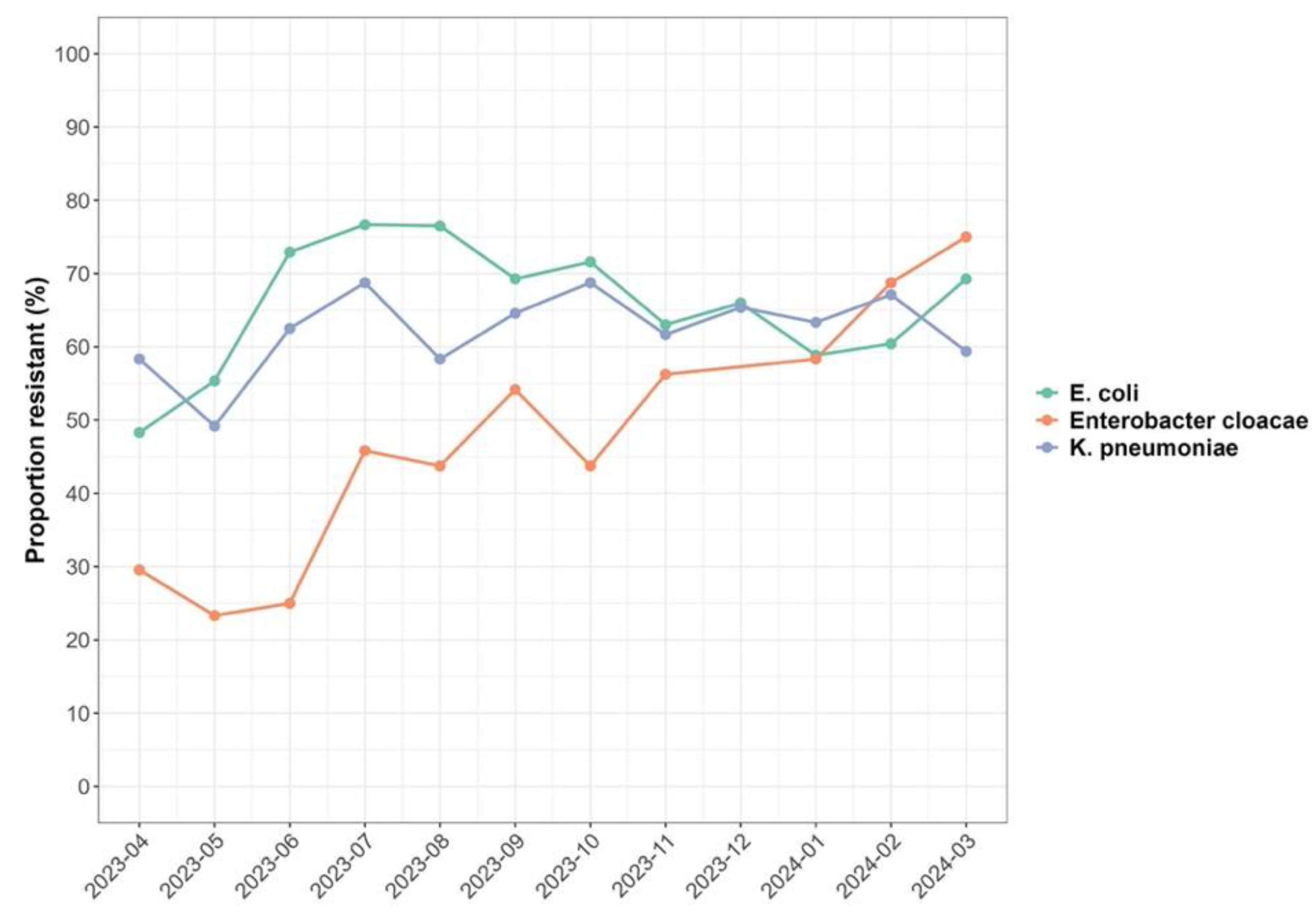

Effect of temperature and rainfall on the prevalence of resistant ESBL organisms

The analysis showed present and ongoing environmental contamination with multiple antibiotic resistant ESBL bacteria across the 12 months of investigation (

Figure 3). It was observed that increases in minimum temperature were associated with an increase in the prevalence of resistant ESBL organisms with an IRR of 1.04 (95% CI: 1.01;1.08). Across the sampled locations, an increase in minimum temperature was associated with an increase in the prevalence of resistant ESBL organisms isolated by 1.41(95% CI: 1.30; 1.53) (p<0.001) for Soche WWTP. Results also showed a decrease in prevalence of resistant ESBL

K. pneumoniae and ESBL

Enterobacter cloacae with an IRR of 0.75 (95% CI: 0.23; 0.32) and 0.27 (95% CI: 0.69, 0.82) respectively with increasing minimum temperature. Conversely, an increase in minimum temperature was associated with increasing antibiotic resistance to CRO, SXT, DXT, CIP with an IRR of 1.62 (95% CI: 1.40, 1.88), 1.58 (95% CI: 1.35, 1.84), 1.40 (95% CI: 1.20, 1.63) and 1.33 (95% CI: 1.40, 1.56) respectively.

Neither maximum temperature nor rainfall had any effect on the prevalence of resistant ESBL organisms as summarized in

Table 3.

3. Discussion

This study has shown environmental contamination with ESBL-producing

E. coli, K. pneumoniae and

Enterobacter cloacae from sewage effluent from two WWTPs in Blantyre, Malawi. The presence of organisms in the wastewater effluent mirrors the observations across the globe reporting ESBL-producing Enterobacterales in effluent wastewater in South Africa [

23], Hungary [

24], Netherlands [

25], Tokyo [

26] and Algeria [

27]. This suggests the need for continuous surveillance for the levels of resistant pathogens in the environment and the improved functionality of wastewater treatment plants across the socioeconomic spectrum encompassing high and also low- and middle-income countries.

Malawi is a low-income country with poor sanitation facilities such as pit latrines, sewage systems and WWTPs. Solid and faecal waste are not always disposed of appropriately and in designated places [

28]. This study persistently found resistant ESBL-producing organisms in effluent from WWTPs over a one-year period, which is a concern because the effluent passes through gardens before entering a river. Of note, there are frequent reports of multidrug-resistant blood stream infections of

E.coli and

K. pneumoniae from a large tertiary hospital located within the catchment area of the Soche WWTP included in this study [

12,

13]. An investigation into the surrounding communities’ exposure to the effluent and the ESBL-producing organisms is required to design appropriate infection prevention and control measures.

A wide variety of antibiotic resistance profiles were found among the ESBL-producing

E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and E. cloacae isolates characterised in this study. The most commonly detected multidrug resistance profile (AUG-SXT-DXT-CIP-GM-ATH-CRO) among these environmental isolates included resistance to widely consumed antibiotics, nationally, in the human sector in Malawi [

29]. There is a potential that the levels of antibiotic consumption are contributing to the emergence of antibiotic resistance [

14]. The calculated multiple antibiotic resistance index in all the three ESBL bacterial species in this study is greater than 0.2 predictive of drug resistance pollution in the environment or high use of antibiotics [

6,

30,

31,

32]. Furthermore, the characterized antibiotic resistance phenotypes in this study are similar to those being reported in isolates from human samples [

21,

22]. The potential for horizontal transfer of resistance genes between human and environmental isolates is possible in this setting. Genome level assessments done in other settings have determined similarity in ESBL-producing isolates from the environmental waste waters and those isolated from human infection [

33]. Genomic surveillance of these MDR pathogens from wastewater and other external environments is needed to ascertain the movement of the bacteria between the environment and the host being infected, whether human or animal.

High levels of resistance to antibiotics in the access (AUG, DXT, GM and SXT) and watch (ATH, CIP, CRO and MEM) WHO categories were prevalent among the environmental isolates investigated in this study. Resistance to meropenem which is categorized as a reserve antibiotic in Malawi was also determined in a few of the isolates from this study. There are limited options for treating these resistant bacteria contaminating gardens and rivers in Blantyre. Carbapenems are scarcely available in public hospitals [

14]. Unregulated antibiotics use at household level in Malawi is largely limited to the access group of antibiotics which are readily available and affordable [

32]. The landscape of resistance in the environmental setting mirrors the reports of high level resistance to access antibiotics and the low levels of carbapenem resistance in the human sector in Malawi [

21,

31]. The similarity in antibiotic resistance levels indicates that environmental isolates and surveillance thereof can be useful in predicting antimicrobial resistance patterns in human infection. As the country invests in infection prevention measures and also antimicrobial stewardship practices in hospitals [

34], waste management regulations should also be strengthened to control the spread of ESBL-producing and carbapenem-resistant infections.

The ESBL-producing bacteria were isolated throughout a twelve-month period that included both hot and cold seasons as well as dry and wet seasons. Temperature and rainfall have been known to affect bacterial growth and persistence of bacteria in wastewater systems [

35]. This study revealed an increase in prevalence of resistant ESBL-producing bacteria with increasing minimum temperature (IRR=1.04). Similar findings have been reported in the United States [

36] substantiating that minimum temperature is associated with increasing presence of resistant bacterial species in the environment. In terms of resistance to specific antibiotics, there was an increase in antibiotic resistance to CRO, SXT, DXT, CIP with increasing minimum temperature. CRO, SXT, DXT and CIP are most commonly used antibiotics [

29] which would increase the selective pressure and also the conditions are favourable for increasing multiple antibiotic resistance. The study in the United States [

36] reported similar results with increasing fluoroquinolones resistance in methicillin-resistant

S. aureus suggesting that minimum temperature has a role to play on AMR.

The main strength of this study was that it allowed for AMR surveillance in the environmental sector complementing surveillance efforts in the animal and human sectors in Malawi. However, there is a need in future studies to also investigate the prevalence on non-ESBL-producing in the effluent and how the ESBL-producing organisms identified in the effluent disseminate and are transmitted in the communities surrounding the wastewater treatment plants . Additionally, an assessment of the influent coming from the different and varied sources may be necessary for targeted sectoral interventions.

In conclusion, there is ongoing environmental contamination of the environment with ESBL-producing and multiple antibiotic-resistant Enterobacterales in Blantyre Malawi. This study highlights the need for improved and efficient waste water management systems to reduce the levels of AMR organisms in the environment. The recent implementation of the national action plan on AMR focused on investments in the human and animal sectors [

34]. However, the renewed commitment by the AMR National Coordinating Centre to equally invest in environmental surveillance will likely fill the knowledge gaps necessary to avert the spread of AMR in Malawi. Future wastewater surveillance for AMR pathogens should also consider assessments of antibiotic residues in the effluent, to take into account factors selecting for resistant organisms.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Sites

The study was conducted within Blantyre, focusing on Soche (S15

o 49’ 13.71” E35

o 0’ 26.44’’) and Blantyre (S15

o 48’ 32.87” E34

o 59’ 20.92”) wastewater treatment plants. These two sites are of the conventional design; however, Blantyre WWTP uses stabilization ponds due to system blockage. Both treatment plants receive waste effluent from surrounding industries and households. Additionally, the Soche treatment system also receives sewage from septic tanks that are delivered by road tankers and also sewage from Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital (QECH) [

37]. QECH is a large tertiary hospital that caters for a population of about 1.3 million from Blantyre City and also referrals from the surrounding districts [

38]. The treatment plants discharge their effluent into streams, and also directly into farms that are a few kilometers after the discharging point (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

4.2. Sample Collection

The study collected effluent wastewater samples at the point of discharge weekly on three consecutive days; Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays from 3rd April 2023 to 27th March, 2024. From both sites, a 500-milliliter grab sample was collected every hour from 9:00 am to 1:00 pm in sterile bottles. The samples were stored in a cooler box packed with ice blocks and were immediately transported to the laboratory for processing.

4.3. Sample Processing, Culture and Bacterial Identification

Sample processing for resistant bacteria and bacterial identification were done according to Moges et al. [

7] and Teshome et al. [

39]. Briefly, 200mL aliquots from individual grab samples for each day were pooled together and mixed before analysis to make a one-liter composite sample, respectively for each study site. 500mL of the pooled and mixed samples were filtered through a 0.45µm pore membrane (Cellulose Nitrate Filter, Germany) to concentrate the bacteria. After filtration, the nitrocellulose filters were incubated in buffered peptone water (BPW) enrichment media at 37

0C overnight. After 18-22 hours, the cultures were sub-cultured onto ESBL chromogenic agar (CHROMagar

TM, France) with ESBL supplement to check for ESBL-producing bacteria. On the third day, the plates were characterized for pink colonies indicative of

E. coli growth

, and blue colonies indicative of either

K.

pneumoniae or

E. cloacae growth. One pink colony of presumptive

E.coli and one blue colony (presumptive

K. pneumoniae or

E. cloacae) from each plate were then isolated and further subcultured onto fresh ESBL CHROMagar for 18-22 hours at 37

0C to make a pure culture. The pure culture was then subcultured onto nutrient agar followed by colony growth identification using the analytical profile index (API) 20E Kit (Biomerieux).

4.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Disk diffusion method was used to measure antibiotic susceptibility of the isolates according to Moges et al. [

7] and Teshome et al. [

39]. A pure colony from nutrient agar was emulsified in sterile 4-5 mls phosphate-buffered saline and homogeneously spread on Mueller-Hinton agar plates. This was followed by dispersing the antibiotic disc of azithromycin (15μg), amoxicillin-clavulanate (30μg), ciprofloxacin (5μg), ceftriaxone (30μg), cotrimoxazole (1.25/23.75μg), doxycycline (30μg), gentamicin (10μg), and meropenem (10μg) onto the plates and incubating aerobically at 37

0C for 18-24hrs. After incubation, results were read and interpreted by referring to the Clinical Laboratory Standard guidelines (CLSI) [

40].

4.5. Multiple Antibiotic-Resistant Phenotype and Multiple Antibiotic Resistance Index

Multiple antibiotic resistance (MAR) was considered for isolates that were resistant to three or more classes of antibiotics [

6]. Whereas Multiple antibiotic resistance index (MARI) was calculated as a proportion of antibiotics that an isolate was resistant to, compared to the total number of antibiotics that were tested [

6,

30].

4.6. Temperature and Rainfall Data

The temperature and rainfall data used in this study were requested from the Department of climate change and meteorological services in Malawi. Chichiri data was used for BTP WTP and Mpemba data was used for Soche WTP.

4.7. Statistical Analysis

All data collected from the laboratory were organized and quality checked using Microsoft Excel. Statistical analysis was performed in R version 4.4.0, where figures and tables were also computed. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize data on samples. Poisson regression analysis with chi-square goodness-of-fit was applied at 95% confidence interval to check for the effect of rainfall and temperature on the prevalence of resistant ESBL organisms (p-value < 0.05 was considered for significance).

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, E.I., C.L.M., C.M., J.M., J.C., R.S.M., M.P., and S.K.; methodology, C.T.M., Y.D., E.I., and C.L.M.; formal analysis, H.H.T., E.I., and C.L.M.; investigation, E.I., C.T.M., Y.D., and C.L.M.; resources, C.L.M., C.M., T.K., J.M., and L.S., ; data curation, E.I.; writing—original draft preparation, E.I.; writing—review and editing, C.L.M., T.K., C.T.M., J.M., R.S.M., S.K., H.H.T., E.M., L.S., W.K., S.M.K and C.M.; supervision, C.L.M., J.M., and C.M.; project administration, E.I., and C.L.M.; funding acquisition, C.L.M., C.M., F.L., T.K., J.M., and L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research was funded by the Swedish International Development Agency under the Joint Programming Initiative on Antimicrobial Resistance, through the African population Health Research Centre (APHRC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The College of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee (COMREC) approved the study, COMREC reference number P.08/22/3695.

Informed Consent: Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Department of Pathology for the Masters Scholarship opportunity. Our sincere gratitude goes to Amadu Jabili Mmadi and Wemusi Chabwera from Blantyre wastewater treatment facilities, who assisted with sample collection. We are also thankful to Chimwemwe Chisembe and Mwayi Taulo for assisting with study map generation. Lastly, we are thankful to the Environmental Research Laboratory team for all the support and also Prof. Nicholas Feasey and Finola Leonard for the insightful comments and guidance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Singer AC, Shaw H, Rhodes V, et al. Review of antimicrobial resistance in the environment and its relevance to environmental regulators. Front Microbiol 2016; 7: 1–22.

- Andleeb S, Majid M, Sardar S. Environmental and public health effects of antibiotics and AMR/ARGs. 2020; 269–291.

- Thai PK, Xuan L, Ngan V, et al. Occurrence of antibiotic residues and antibiotic-resistant bacteria in effluents of pharmaceutical manufacturers and other sources around Hanoi, Vietnam. Sci Total Environ 2018; 645: 393–400.

- Chitescu CL, Lupoae M, Elisei AM. Pharmaceutical residues in the environment - new european integrated programs required. Rev Chim 2016; 67: 1008–1013.

- Papajov I, Gregov G, Papaj J, et al. Effect of wastewater treatment on bacterial community, antibiotic-resistant bacteria and endoparasites. Int J Environ Res Public Health; 19. [CrossRef]

- Mbanga J, Luther A, Abia K, et al. Longitudinal surveillance of antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli and Enterococcus spp. from a wastewater treatment plant and its associated waters in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Microb Drug Resist 2021; 27: 904–918.

- Moges F, Endris M, Belyhun Y, et al. Isolation and characterization of multiple drug resistance bacterial pathogens from waste water in hospital and non-hospital environments, northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 2014, 2014; 7: 2–7.

- Milakovi M, Vestergaard G, González-plaza JJ, et al. Antibiotic-manufacturing sites are hot-spots for the release and spread of antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements in receiving aquatic environments pollution from azithromycin-manufacturing promotes macrolide-resistance gene propagation a. Environ Int 2019; 123: 501–511.

- Max M. Antibiotics, antibiotic resistance and environment. Encyclopedia of the environnement 2019; 1–9.

- Rodríguez-molina D, Mang P, Schmitt H, et al. Do wastewater treatment plants increase antibiotic resistant bacteria or genes in the environment? protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev 2019; 9: 1–8.

- Collaborators, AR. Articles Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019 : a systematic analysis. 399. Epub ahead of print 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tam PI, Musicha P, Kawaza K, et al. Emerging resistance to empiric antimicrobial regimens for pediatric bloodstream infections in Malawi (1998-2017). Clinical infectious diseases 2019; 2–30.

- Lester R, Musicha P, Kawaza K, et al. Articles Effect of resistance to third-generation cephalosporins on morbidity and mortality from bloodstream infections in Blantyre , Malawi : a prospective cohort study. The Lancet Microbe; 3: e922–e930.

- Kayambankadzanja RK, Lihaka M, Barratt-due A, et al. The use of antibiotics in the intensive care unit of a tertiary hospital in Malawi. BMC Infect Dis 2020; 20: 1–7.

- Mankhomwa J, Tolhurst R, M’biya E, et al. A qualitative study of antibiotic use practices in intensive small-scale farming in urban and peri-urban Blantyre, Malawi: implications for antimicrobial resistance. Front Vet Sci 2022; 9: 1–16.

- Cocker D, Chidziwisano K, Mphasa M, et al. Articles investigating one health risks for human colonisation with extended spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in Malawian households: a longitudinal cohort study. The Lancet Microbe 2023; 4: 534–543.

- Tegha G, Ciccone EJ, Krysiak R, et al. Genomic epidemiology of Escherichia coli isolates from a tertiary referral center in Lilongwe , Malawi. Microb Genomics 2021; 7: 1–12.

- Varela AR, Manaia CM. Human health implications of clinically relevant bacteria in wastewater habitats. Env Sci Pollut Res 2013; 20: 3550–3569.

- Navidinia, M. The clinical importance of emerging ESKAPE pathogens in nosocomial infections. J Paramed Sci 2016; 7: 43–57.

- Oliveira DMP De, Forde BM, Kidd TJ, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in ESKAPE pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev 2020; 33: 1–49.

- Musicha P, Feasey NA, Cain AK, et al. Genomic landscape of extended-spectrum β-lactamase resistance in Escherichia coli from an urban African setting. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017; 72: 1602–1609.

- Musicha P, Msefula CL, Mather AE, et al. Genomic analysis of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Malawi reveals acquisition of multiple ESBL determinants across diverse lineages. J Antimicrob Chemother 2019; 74: 1223–1232.

- Nzima B, Adegoke AA, Ofon UA, et al. Resistotyping and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase genes among Escherichia coli from wastewater treatment plants and recipient surface water for reuse in South Africa. New Microbes New Infect 2020; 38: 1–7.

- Mutuku C, Melegh S, Kovacs K, Urban P, Virág E, Heninger R, Herczeg R, Sonnevend A, Gyenesei A, Fekete C et al. Characterization of β -lactamases and multidrug resistance mechanisms in enterobacterales from hospital effluents and wastewater treatment plant. Antibiotics 2022; 11: 1–21.

- Verburg I, Garc S, Hern L, et al. Abundance and antimicrobial resistance of three bacterial species along a complete wastewater pathway. Microorganisms 2019; 7: 1–15.

- Sekizuka T, Tanaka R, Hashino M, et al. Comprehensive genome and plasmidome analysis of antimicrobial resistant bacteria in wastewater treatment plant effluent of Tokyo. Antibiotics 2022; 11: 1–16.

- Alouache S, Estepa V, Messai Y, et al. Characterization of esbls and associated quinolone resistance in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from an urban wastewater plant in Algeria. Microb Drug Resist 2013; 00: 1–9.

- Mwapasa T, Mphasa M, Cocker D, et al. Community exposure assessment to anti-microbial resistance (AMR); case study of Malawi. In: UNC Water and Health, p. 1.

- Ministry of Health (Mw). Malawi standard treatment guidelines. 6th ed., https://www.differentiatedservicedelivery.org/wp-content/uploads/MSTG-6th-Edition-2023-Final-Draft-CC-gn-2-edditi_230719_133059.pdf (2023).

- Afunwa RA, Ezeanyinka J, Afunwa EC, et al. Multiple antibiotic resistant index of gram-negative bacteria from bird droppings in two commercial poultries in Enugu , Nigeria. Open J Med Microbiol 2020; 10: 171–181.

- Sibande GT, Banda NPK, Moya T, et al. Antibiotic guideline adherence by Clinicians in medical wards at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital (QECH), Blantyre Malawi. Malawi Med J 2022; 34: 3–8.

- Macpherson EE, Mankhomwa J, Dixon J, et al. Household antibiotic use in Malawi : A cross- sectional survey from urban and peri-urban Blantyre. PLOS Glob Public Heal 2023; 1–13.

- Raven KE, Ludden C, Gouliouris T, et al. Genomic surveillance of Escherichia coli in municipal wastewater treatment plants as an indicator of clinically relevant pathogens and their resistance genes. Microbiol Soc 2019; 5: 1–10.

- Malawi national action plan on antimicrobial resistance: review of progress in the human health sector. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021. Epub ahead of print 2021. DOI: licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo.

- Conforti S, Holschneider A, Sylvestre É, et al. Monitoring ESBL- Escherichia coli in Swiss wastewater between November 2021 and November 2022: insights into population carriage . mSphere; 9. Epub ahead of print 2024. [CrossRef]

- MacFadden DR, McGough SF, Fisman D, et al. Antibiotic resistance increases with local temperature. Nat Clim Chang 2018; 8: 510–514.

- Kraslawski A, Avramenko Y. Comparison of pollutant levels in effluent from wastewater treatment plants in Blantyre, Malawi. Int J Water Resour Environ Eng 2010; 2: 79–86.

- Feasey NA, Gaskell K, Wong V, et al. Rapid emergence of multidrug resistant, H58-lineage salmonella typhi in Blantyre. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015; 9: 1–13.

- Teshome A, Alemayehu T, Deriba W, et al. Antibiotic resistance profile of bacteria isolated from wastewater systems in eastern Ethiopia. J Environ Public Health 2020; 2020: 10.

- CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 30th ed. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2020.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).