1. Introduction

Water as a potential vehicle for antimicrobial resistance (AMR) circulation between the three domains of health is a well-known phenomenon (Zaheer et al., 2020). By monitoring water sources, researchers can gain information on the circulating genes, key hotspots for evolution and transmission of AMR, and the risk factors that contribute to the exacerbation of the problem (Liguori et al., 2022).

In One Health inspired surveillance programmes, different types of water sources are worth investigating, whereas waters with different dynamics, different size or different locations can contribute to AMR transmission in different ways and different extent (Davis et al., 2022). In this study we attempted to compare a major stream of Europe with small patches of surface waters in order to assess the potential contribution of these completely dissimilar water habitats to AMR circulation.

Rivers are not just channels for water but very complicated ecosystems with great impact on their whole floodplain area. The water that is transported by the river forms a single system with the groundwater of the floodplain area. A part of this groundwater flow very slowly parallelly by the main current. This so-called hyporheic zone of the river serve as a subterranean ecosystem for many aquatic organisms (Stanford & Ward, 1988; Findlay, 1995; Gottstein et al., 2023). We hypothesised that floodplain areas with their hyporheic zones could accumulate bacteria which arrive by floods, therefore these special water systems could possess a rich bacterial community with higher rate of AMR than the remote areas.

Small surface water patches in forests can serve as important water sources for wildlife during scarcity of water during the summer drought. The epidemiological role of these waterholes is confirmed in different parts of the world. All these works ascertained that during harsh drought periods, these waterholes can contribute to the maintenance and spread of different bacterial or parasitic diseases (Jansen et al., 2006; Naranjo et al., 2008; Barasona et al., 2017; Amoroso et al., 2019). Based on these data, we hypothesised that AMR can also be accumulated and transmitted by these watering places. We speculated that in the case of waterholes, very similar bacteria and AMR phenotype could be detected within a limited forest area as a consequence of shared water source.

For demonstration of our hypotheses, we chose the genera Staphylococcus and Enterococcus. These bacteria are ubiquitous and less demanding for culture condition. Both genera can tolerate salt content in the culture media, therefore salt supplemented enrichment step in the isolation process can enhance the success (Ma et al., 2019; Jeong et al., 2017; Paria et al., 2022; Nocera et al., 2022).

2. Materials and methods

Based on the hypothesis that both major rivers and small watering sites of wildlife can transmit AMR between individuals and even between the domains of health, we selected two wet habitats for sampling. We carried out the sampling in June and July 2024.

Our first sample site was the active floodplain of the Drava River on the common border of Croatia and Hungary. This river begins in the Alps, in Italy and takes 749 km until its confluence with the Danube (

Tadic and Brlekovic, 2019). It possesses a 41,810 km

2 catchment area (

Lóczy et al., 2014). The river section in Hungary is mainly a lowland area. The upstream of this section has got very good water quality, the extent of pollution is very low, whereas large cities and extensive industrial or agricultural activity are not characteristic by the river (

Gvozdic et al., 2011). Despite the extensive channelisation and flood control activities, the Drava floodplain area is a valuable natural ecosystem (

Salem et al., 2020). The river’s hyporheic zone maintains a hydraulic balance with groundwater, therefore the riverbed, the tributary streams and the groundwater of the active floodplain form a single system (

Figure 1).

The Zselic Hills area is a hilly microregion in the South Transdanubia of Hungary. Though its climate is under Atlantic influence, most of its surface waters are periodic (

Figure 2). During dry summers, only the main streams remain. During these scarce periods, small waterholes in the forested area are the only source of water for wildlife (

Csivincsik et al., 2016).

We took water and mud samples from the study sites. Water samples were taken with sterile syringe to a sterile plastic tube, which was half-filled with buffered peptone water supplemented with 20% sodium chloride. As we filled the tube fully, the end concetration of the salt got 10%. The mud samples were collected by plunging a sterile cotton swab into the mud and then put it into a tube that was filled with buffered peptone water supplemented with 10% sodium chloride.

The samples were incubated for 48 hours at 36 °C, then we inoculated a plate count agar (PCA) with the homogenised liquid culture. We incubated the plates for 48 hours at 36 °C and checked it in every 24 hours. We purified the suspect Staphylococcus (Shaw et al., 1951) and Enterococcus (Swan, 1954) colonies onto PCA media. After Gram staining, we selected Gram positive cocci for further investigation by VITEK Compact 2 system. We identified the bacterial species by VITEK GP card type. Those, which were identified as Staphylococcus or Enterococcus were processed with antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) by AST-P592 card type.

The results of the laboratory work were gathered into an Excel file. The bacterial communities of the two habitats were compared by the calculation of Sorensen Dice similarity index (Dias et al., 2021). The antimicrobial susceptibility results were presented graphically by Sankey charts in Excel Power User. For the statistical comparison of AMR and MDR rates of the two sites, Fisher’s exact test was used in R-statistics software version 4.4.2.

3. Results

By Drava River and within the Zselic Hills, we collected 10 and 22 water or mud samples, respectively. From the Drava and the Zselic samples, 13 and 21 bacterial strains belonging to the genera Staphylococcus or Enterococcus could be isolated.

Table 1.

Isolates of Staphylococcus and Enterococcus genera from Drava River and Zselic Hills.

Table 1.

Isolates of Staphylococcus and Enterococcus genera from Drava River and Zselic Hills.

| Sampling site |

Sample size |

Staphylococcus positive samples |

Enterococcus positive samples |

Number of Staphylococcus species |

Number of Enterococcus species |

| Drava River |

10 |

5 |

5 |

6 |

2 |

| Zselic Hills |

22 |

14 |

7 |

5 |

4 |

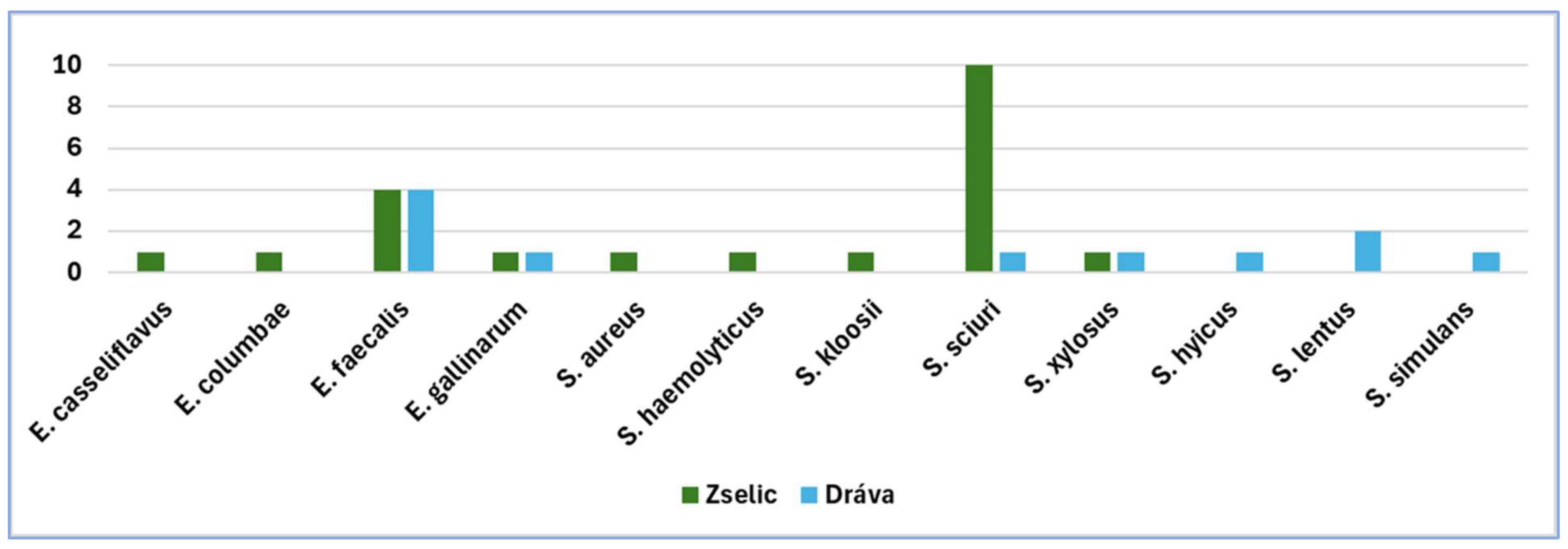

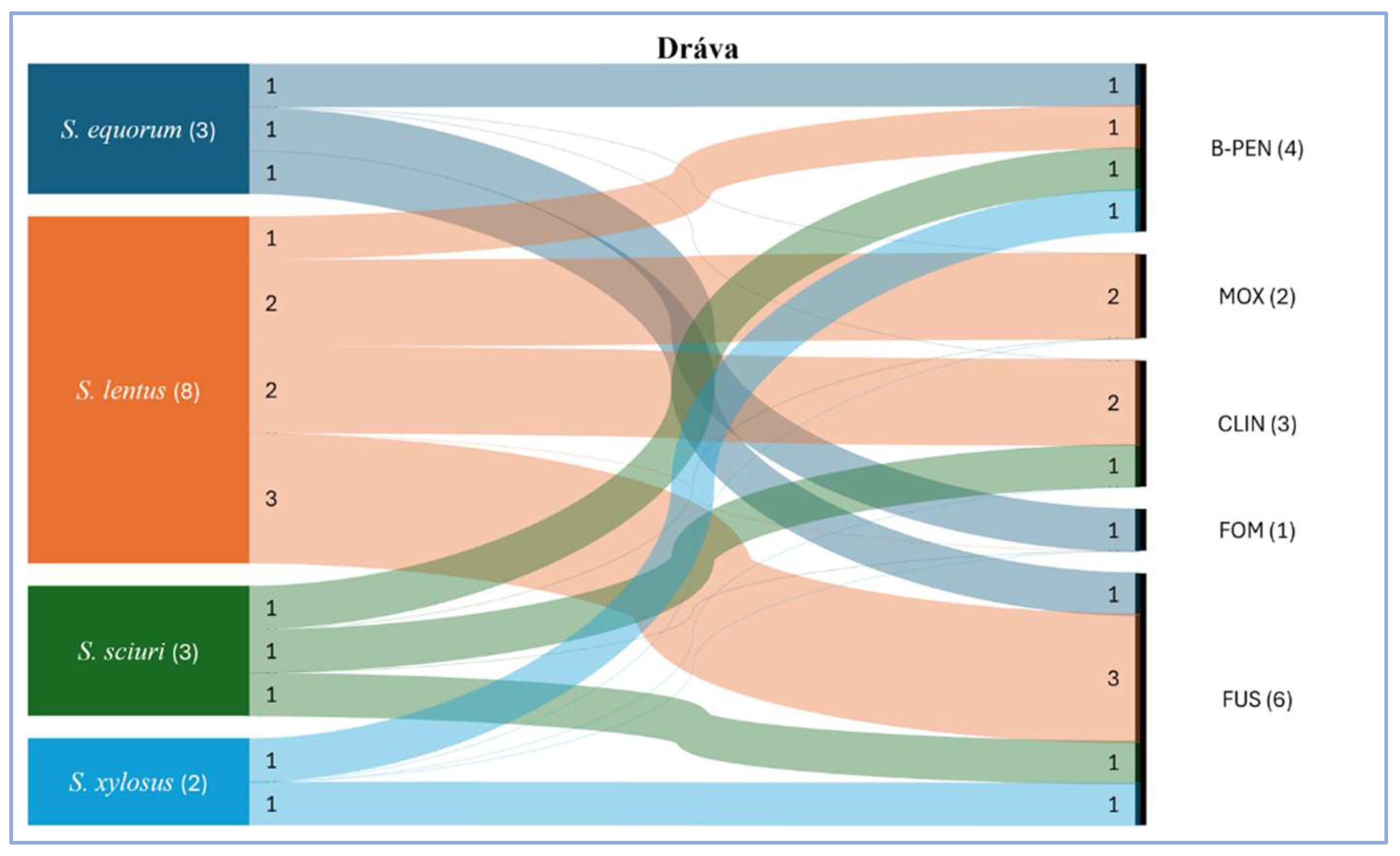

From the active floodplain area of Drava River, we isolated

S. equorum,

S. hyicus,

S. lentus,

S. sciuri,

S. simulans,

S. xylosus.

E. faecalis, and

E. gallinarum (

Figure 3). Among the staphylococci, 4 MDR strains, a

S. sciuri, two

S. lentus, and a

S. equorum isolates were detected. The antimicrobials, to which the isolated bacterial strains proved resistant were fusidic acids (6 strains), benzylpenicillin (4 strains), moxifloxacin (2 strains), clindamycin (3 strains), and fosfomycin (1 strain).

S. hyicus and

S. simulans strains did not show resistance to either tested antimicrobial.

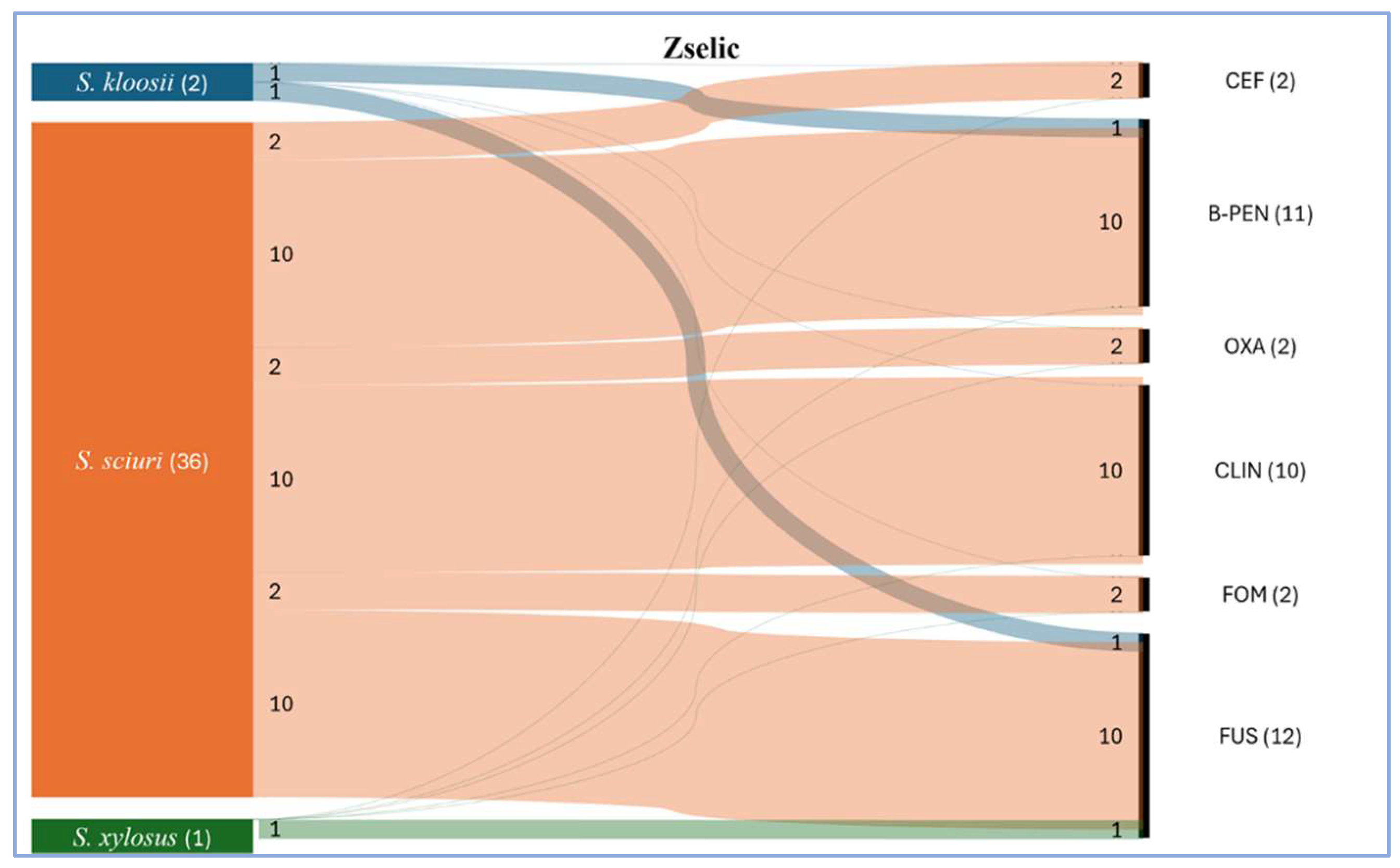

From the Zselic Hills study site, we isolated

S. aureus,

S. haemolyticus,

S. kloosi,

S. sciuri, S

. xylosus,

E. faecalis,

E. casseliflavus,

E. gallinarum (

Figure 3). Among them, we detected 10

S. sciuri strains that were all resistant to at least 3 classes of antimicrobials (ß-lactams, clindamycin, fusidic acid). Two of these multidrug resistant isolates were methicillin resistant (MR) by phenotype, as they proved resistant to both cefoxitin and oxacillin. Moreover, these two MR

S. sciuri were resistant also to fosfomycin. Besides

S. sciuri isolates, we detected resistance in a

S. kloosi (to benzylpenicillin and fusidic acid) and in a

S. xylosus strain (to fusidic acid). The only one

S. aureus isolate proved susceptible to all tested antimicrobials, like the only

S. haemolyticus isolate as well. Among the enterococci, both

E. gallinarum group strain (

E. gallinarum and

E. casseliflavus) showed resistance against vancomycin. Moreover, the

E. gallinarum strain proved resistant to ciprofloxacin as well.

Comparison of the bacterial communities of the two habitats resulted in a Sorensen-Dice Index of 0.5, which means a moderate similarity. The detailed results of this study can be accessed in a Supplementary Material on link

https://zenodo.org/records/14214070 The antimicrobial resistance conditions of the isolated bacteria from the two studied habitat are presented as Sankey charts. Based on the graphical appearance, the floodplain bacterial community seemed more diverse with less phenotypic resistance (

Figure 4). However, the waterholes gather a less diverse community with resistance to more antimicrobials (

Figure 5).

The summarised AMR conditions of the two habitats seemed different. In Zselic waterholes, among 21 strains, we found 14 resistant isolates of which 10 were MDR. In the floodplain ecosystem of Drava, among 13 strains, 8 isolates proved to be AMR of which 4 were MDR. Comparing the two habitats with Fisher’s exact test, in the view of AMR and MDR rate, we obtained P=1 and P=0.477, respectively.

4. Discussion

Our study compared two types of wet habitats in the viewpoint of AMR circulation between the domains of health. We hypothesised that both watering sites for wildlife and major streams can be vehicles of AMR transmission.

By sampling in the active floodplain of the Drava River and waterholes of the Zselic Hills, we succeeded in isolating staphylococci or enterococci from 80.00% and 68.18% of the samples, respectively. Therefore, we confirmed that sodium chloride supplementation of a general liquid medium (buffered peptone water) was appropriate for selective culture of bacteria belonging to both Staphylococcus and Enterococcus genera.

In the Drava ecosystem, we observed a bacterial community, which was rich in Staphylococcus species. The Staphylococcus community of the Zselic ecosystem was less diverse, since almost half of the strains belonged to S. sciuri. In the case of enterococci, a remarkable predominance of E. faecalis could be detected on both sampling site.

Though the sample size was small, differences can be noticed between the two habitats. Future research with large sample size might reveal the difference between the composition of Staphylococcus communities of the two types of ecosystems. Based on the current observation, we hypothesise that rivers can be important vehicles of resistant bacteria. Molecular genetic investigations might provide more detailed information about the extent of their effect. In the case of Zselic, the potential role of waterholes in transmission of AMR was supported by our data. However, in the lack of molecular genetic investigation, these observations can provide solely indirect evidence of AMR transmission role of watering sites.

The parallel detection of high rate of AMR and E. faecalis suggests that the forest waterholes were frequently visited and contaminated by animals. This observation agrees with previous studies, which confirmed the bacterial contamination of these water sources by wild boars (Jansen et al., 2006; Naranjo et al., 2008; Barasona et al., 2017). Our sampling period was in the summer of 2024, which had an extremely dry weather. The scarcity of water was severe, therefore a lot of animals had to share the same water sources. Neither direct nor indirect contacts through these waterholes could be excluded.

The high prevalence of E. faecalis in river samples also draws attention to the contamination spreader role of the rivers. However, the sample collection of this study was carried out after a smaller flood, which could alter the normal conditions. In the future, it is worth sampling the river’s water in different periods of the year to assess the risk of freshwater habitats as vehicles of bacteria.

By comparison of AMR conditions of the two habitats, we ascertained that benzylpenicillin and fusidic acid are the antibiotics, to which most of the strains were resistant on both sampling sites. Benzylpenicillin is one of the first-choice antibiotics in veterinary practice (Goggs et al., 2021), therefore the widespread resistance was not surprising. However, about extensive use of fusidic acid we could not find any data. This observation needs further research to highlight its background.

The most prominent finding was the two, methicillin resistant S. sciuri isolates in the Zselic Hills, which showed MICs to oxacillin and even clindamycin above the EUCAST clinical breakpoints (EUCAST, 2024). This observation questioned the routine explanation that S. sciuri, as an ancient type of staphylococci, is a reservoir of naturally evolved resistance genes of the Staphylococcus genus (Sacramento et al., 2022). We hypothesised that above naturally occurring mecA1 gene, which normally cannot cause phenotypic resistance, these strains might carry acquired genetic elements as well. Maybe as a result of a human mediated contamination of the wild domain of health. S. sciuri group can acquire and spread AMR genes as pathogenic staphylococci. This ability calls attention to these ubiquitous bacteria as potential threat to human and animal health (de Carvalho et al., 2024). It was rather curious that the two CoPS strains, S. aureus (Zselic) and S. hyicus (Drava) did not show resistance to any of the tested antibiotics.

In Enterococcus gallinarum strains, we detected vancomycin and ciprofloxacin resistance with very low MIC on both study sites. In the case of vancomycin resistance, we know that E. gallinarum, E. casseliflavus, and E. flavescens species can carry intrinsic resistance genes. The resistance to ciprofloxacin needs further research completed with molecular genetics to reveal the background.

Though the graphical presentation of the AMR data showed conspicuous difference between the two habitats (Sankey charts in Supplementary Material), the statistical analysis of AMR and MDR rates could not reveal any difference between the Drava floodplain and the Zselic forest waterholes.

Summarising our observations, we can ascertain that both staphylococci and enterococci could be isolated from environmental samples with high prevalence. Therefore, the chosen laboratory process was confirmed to be appropriate for these types of samples. The remarkable rate of AMR and MDR in the isolated strains made them suitable as model bacteria for investigation of AMR circulation through the domains of health. Our findings supported the hypothesis that both rivers and watering sites of wildlife can serve as vehicles of AMR. For better appreciation of this role of water, this research is worth continuing with larger sample size completed with molecular genetic investigations.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the Flagship Research Groups Programme of the Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

References

-

Amoroso, C.R., Kappeler, P.M., Fichtel, C. & Nunn, C.L. (2019): Fecal contamination, parasite risk, and waterhole use by wild animals in a dry deciduous forest. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 73(11), 153. [CrossRef]

-

Barasona, J.A., Vicente, J., Díez-Delgado, I., Aznar, J., Gortázar, C. & Torres, M.J. (2017): Environmental presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in aggregation points at the wildlife/livestock interface. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases, 64(4), 1148-1158. [CrossRef]

-

Csivincsik, Á., Rónai, Z., Nagy, G., Svéda, G. & Halász, T. (2016): Surveillance of Mycobacterium caprae infection in a wild boar (Sus scrofa) population in southwestern Hungary. Veterinarski Arhiv, 86(6), 767-775.

-

Davis, B. C., Keenum, I., Calarco, J., Liguori, K., Milligan, E., Pruden, A. & Harwood, V.J. (2022): Towards the standardization of Enterococcus culture methods for waterborne antibiotic resistance monitoring: A critical review of trends across studies. Water Research X, 17, 100161. [CrossRef]

-

de Carvalho, A., Giambiagi-deMarval, M. & Rossi, C.C. (2024): Mammaliicoccus sciuri_’s pan-immune system and the dynamics of horizontal gene transfer among Staphylococcaceae: A One-Health CRISPR tale. Journal of Microbiology, 62, 775–784. [CrossRef]

-

Dias, F.S., Betancourt, M., Rodríguez-González, P.M. & Borda-de-Água, L. (2021): Analysing the distance decay of community similarity in river networks using Bayesian methods. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 21660. [CrossRef]

-

EUCAST (The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing). (2024): Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 14.0. http://www.eucast.org.

-

Findlay, S. (1995): Importance of surface-subsurface exchange in stream ecosystems: The hyporheic zone. Limnology and Oceanography, 40(1), 159-164. [CrossRef]

-

Goggs, R., Menard, J.M., Altier, C., Cummings, K.J., Jacob, M.E., Lalonde-Paul, D.F., Papich, M.G., Norman, K.N., Fajt, V.R., Scott, H.M. & Lawhon, S.D. (2021): Patterns of antimicrobial drug use in veterinary primary care and specialty practice: A 6-year multi-institution study. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 35(3), 1496-1508. [CrossRef]

-

Gottstein, S., Redžović, Z., Erk, M., Sertić Perić, M., Dautović, J. & Cindrić, M. (2023): Life history traits of the stygophilous amphipod Synurella ambulans in the hyporheic zone of the lower reaches of the Upper Sava River (Croatia). Water,15(18), 3188. [CrossRef]

-

Gvozdić, V., Brana, J., Puntarić, D., Vidosavljević, D. & Roland, D. (2011): Changes in the lower Drava River water quality parameters over 24 years. Arhiv za Higijenu Rada i Toksikologiju, 62(4), 325-332. [CrossRef]

-

Jansen, A., Nöckler, K., Schönberg, A., Luge, E., Ehlert, D. & Schneider, T. (2006): Wild boars as possible source of hemorrhagic leptospirosis in Berlin, Germany. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 25, 544-546. [CrossRef]

-

Liguori, K., Keenum, I., Davis, B. C., Calarco, J., Milligan, E., Harwood, V.J. & Pruden, A. (2022): Antimicrobial resistance monitoring of water environments: A framework for standardized methods and quality control. Environmental Science & Technology, 56(13), 9149-9160. [CrossRef]

-

Lóczy, D., Dezső, J., Czigány, S., Gyenizse, P., Pirkhoffer, E. & Halász, A. (2014): Rehabilitation potential of the Drava River floodplain in Hungary. Water Resources and Wetlands, Conference Proceedings, 11-13. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y., Lan, G., Li, C., Cambaza, E.M., Liu, D., Ye, X., Chen, S. & Ding, T. (2019): Stress tolerance of Staphylococcus aureus with different antibiotic resistance profiles. Microbial Pathogenesis, 133, 103549. [CrossRef]

-

Naranjo, V., Gortazar, C., Vicente, J. & de La Fuente, J. (2008): Evidence of the role of European wild boar as a reservoir of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Veterinary Microbiology, 127(1-2), 1-9. [CrossRef]

-

Nocera, F.P., Ferrara, G., Scandura, E., Ambrosio, M., Fiorito, F. & De Martino, L. (2022): A preliminary study on antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus spp. and Enterococcus spp. grown on mannitol salt agar in European wild boar (Sus scrofa) Hunted in Campania Region-Italy. Animals,12, 85. [CrossRef]

-

Paria, P., Chakraborty, H.J. & Behera, B.K. (2022): Identification of novel salt tolerance-associated proteins from the secretome of Enterococcus faecalis. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 38(10), 177. [CrossRef]

-

Sacramento, A.G., Fuga, B., Monte, D.F., Cardoso, B., Esposito, F., Dolabella, S.S., Barbosa, A.A. T., Zanella, R.C., Cortopassi, S.R.G., da Silva, L.C.B.A., Lincopan, N. & Sellera, F.P. (2022): Genomic features of mecA-positive methicillin-resistant Mammaliicoccus sciuri causing fatal infections in pets admitted to a veterinary intensive care unit. Microbial Pathogenesis, 171, 105733. [CrossRef]

-

Salem, A., Dezső, J., El-Rawy, M. & Lóczy, D. (2020): Hydrological modeling to assess the efficiency of groundwater replenishment through natural reservoirs in the Hungarian Drava River floodplain. Water, 12(1), 250. [CrossRef]

-

Shaw, C., Stitt, J. M., & Cowan, S. T. (1951). Staphylococci and their classification. Microbiology, 5(5), 1010-1023. [CrossRef]

-

Stanford, J. & Ward, J. (1988): The hyporheic habitat of river ecosystems. Nature,335, 64–66. [CrossRef]

-

Swan, A. (1954): The use of a bile-aesculin medium and of Maxted’s technique of Lancefield grouping in the identification of enterococci (group D streptococci). Journal of Clinical Pathology, 7(2), 160-163. [CrossRef]

-

Tadić, L. & Brleković, T: (2019): Hydrological characteristics of the Drava River in Croatia. In: Lóczy, D. (eds) The Drava River. Springer Geography. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, R., Cook, S.R., Barbieri, R., Goji, N., Cameron, A., Petkau, A., Polo, R.O., Tymensen, L., Stamm, C., Song, J., Hannon, S., Jones, T., Church, D., Booker, C.W., Amoako, K., Van Domselaar, G., Read, R.R. & McAllister, T.A. (2020): Surveillance of Enterococcus spp. reveals distinct species and antimicrobial resistance diversity across a One-Health continuum. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 3937. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).