Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

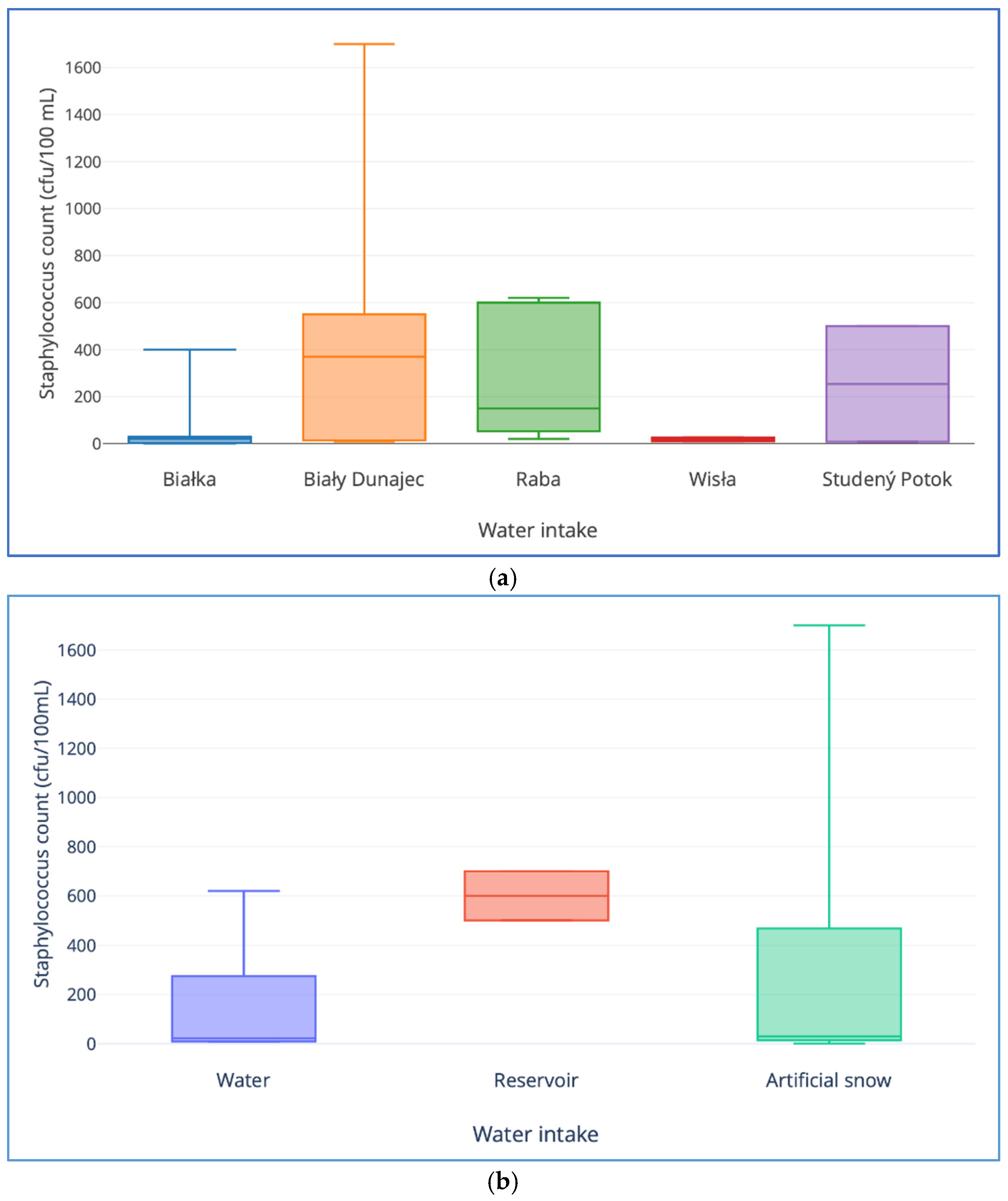

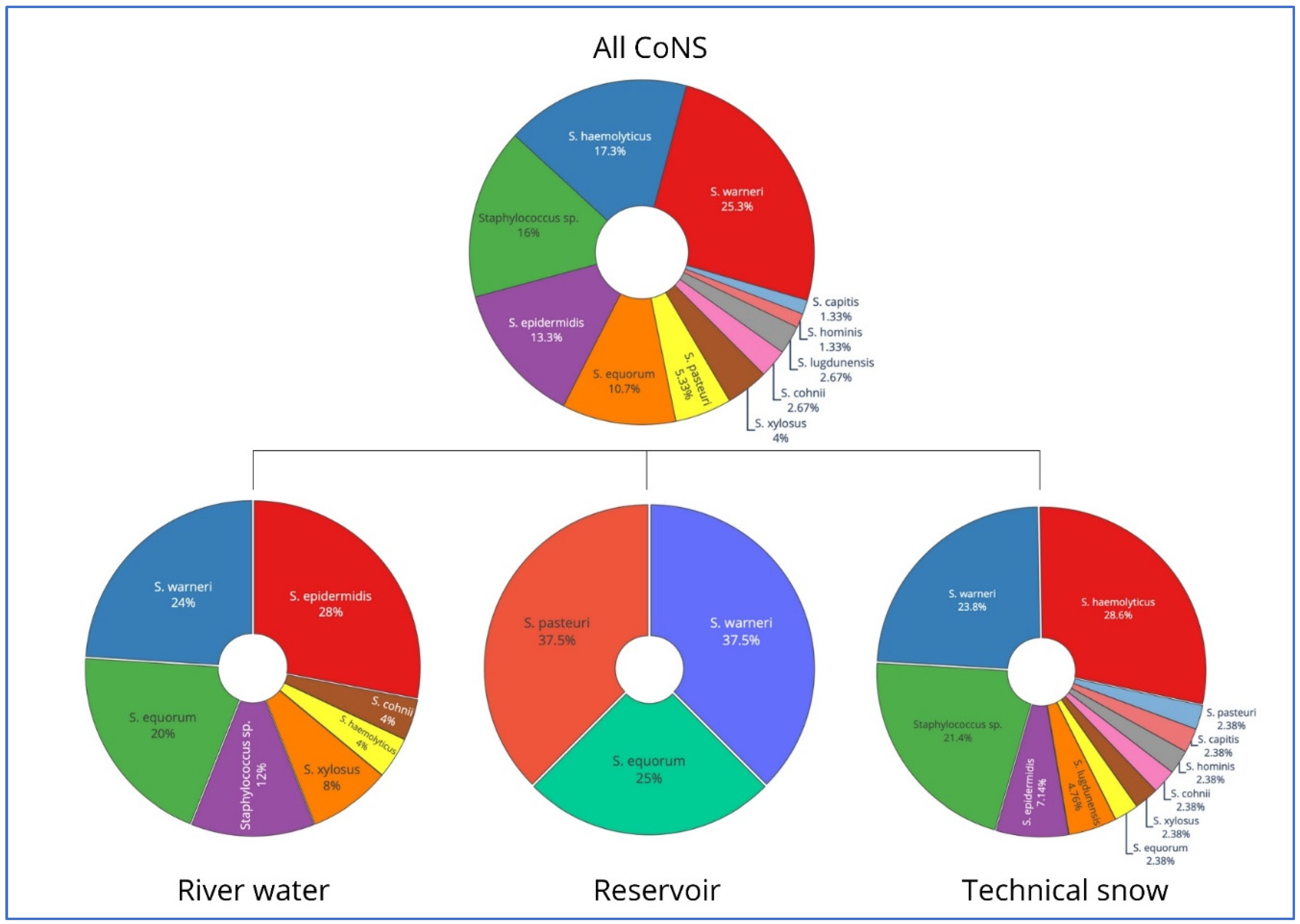

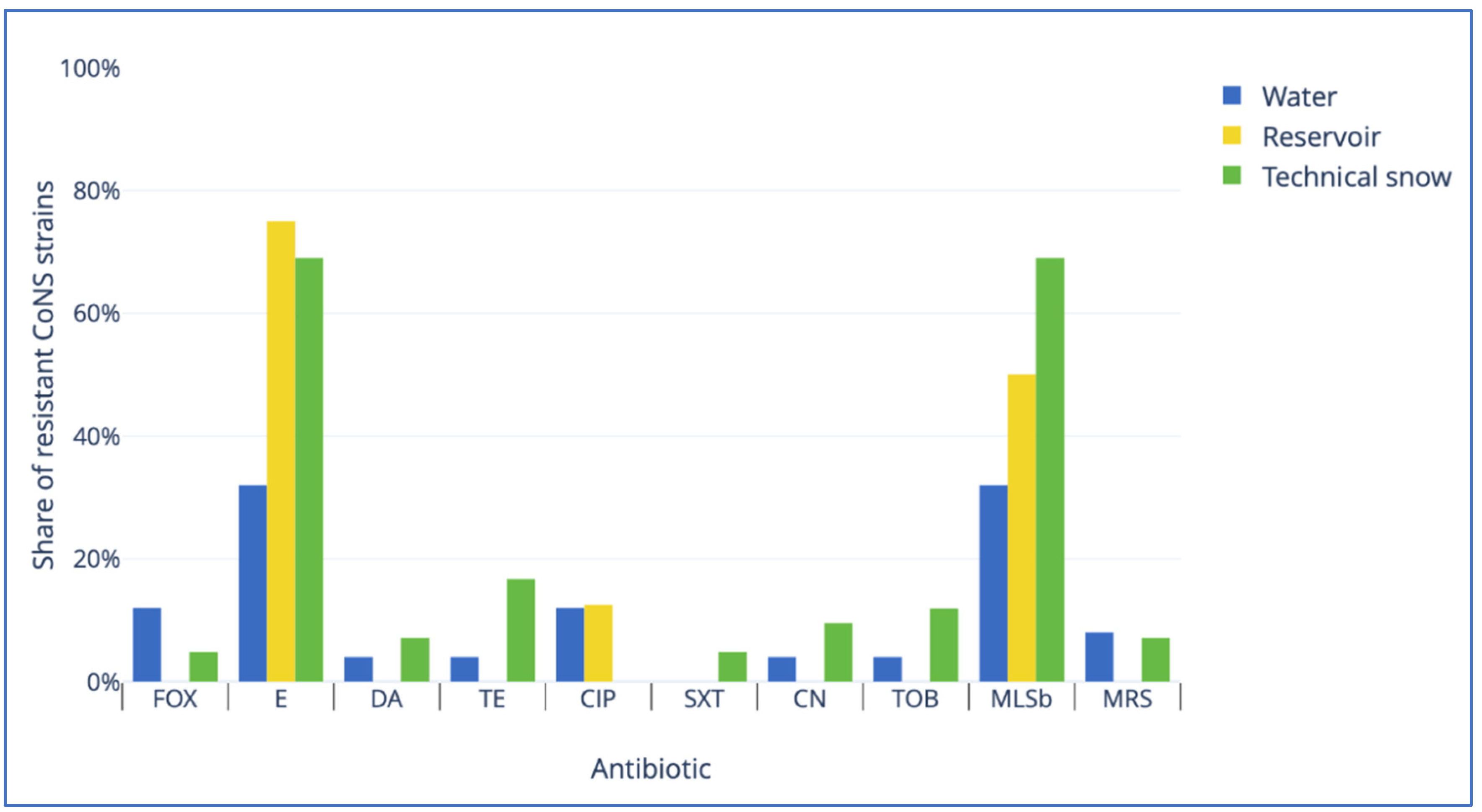

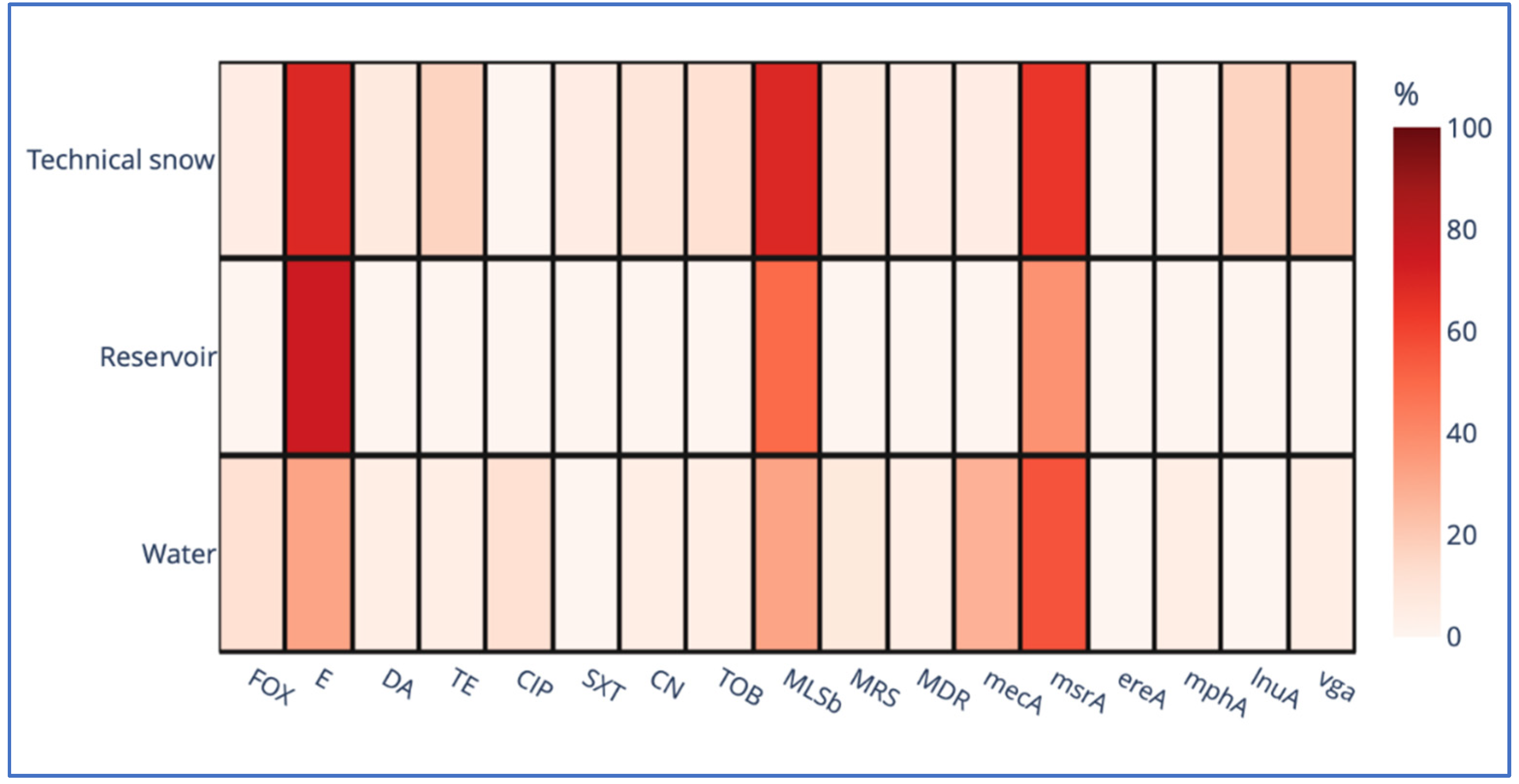

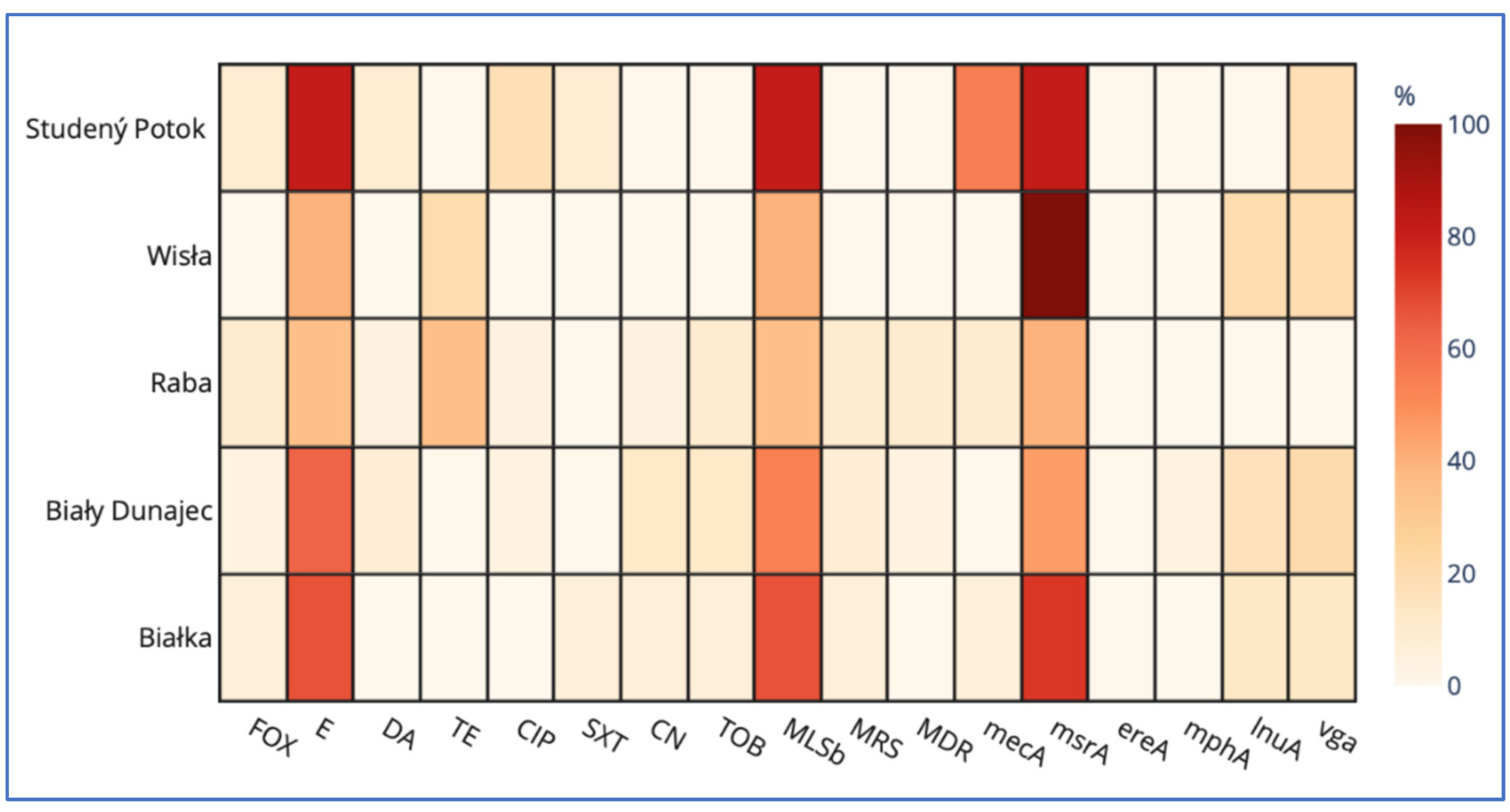

Coagulase-negative staphylococci form a heterogeneous group, defined solely by the lack of coagulase. Initially considered non-pathogenic, now known opportunistic pathogens of increasing importance. This study was conducted to examine the prevalence of Staphylococcus spp., their taxonomic diversity, antibiotic resistance patterns and genetic determinants of antibiotic resistance in the water resources within the technical snow production process. The types of samples included 1) river water at intakes where water is drawn for snowmaking; 2) water stored in technical reservoirs, from which it is pumped into the snowmaking systems; 3) technical snow-melt water. The study was conducted in catchments of five rivers: Białka, Biały Dunajec, Raba and Wisła in Poland, and Studený Potok in Slovakia. Staphylococcus spp. was detected in all types of samples: in 17% of river water, 25% of reservoir-stored water and in 60% of technical snow-melt water. All staphylococci were coagulase-negative (CoNS) and belonged to 10 species, with S. epidermidis being the most prevalent in river water, S. warneri and S. pasteuri in reservoir-stored water, and S. haemolyticus in snowmelt water. The highest resistance rates to erythromycin and macrolide/lincosamid.streptogramin b (MLSb) types of resistance were detected in all types of samples, accompanied by erythromycin efflux pump-determining msrA gene as the most frequent genetic determinant of antimicrobial resistance. This study is the first report of the presence of antibiotic resistant, including multidrug resistant CoNS, carrying more than one gene determining antimicrobial resistance in technical snow, in mountain areas of the central European countries.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Analysis

2.2. Isolation and Identification of Staphylococci

2.3. Culture-Based Antibiotic Resistance Determination

2.4. Detection of Antibiotic Resistance Genes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Becker, K.; Both, A.; Weißelberg, S.; Heilmann, C.; Rohde, H. Emergence of Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci. Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy 2020, 18, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, K.; Heilmann, C.; Peters, G. Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci. Clinical microbiology reviews 2014, 27, 870–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faria, C.; Vaz-Moreira, I.; Serapicos, E.; Nunes, O.C.; Manaia, C.M. Antibiotic Resistance in Coagulase Negative Staphylococci Isolated from Wastewater and Drinking Water. Science of the Total Environment 2009, 407, 3876–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, G.A.C.; Dropa, M.; Martone-Rocha, S.; Peternella, F.A.S.; Veiga, D.P.B.; Razzolini, M.T.P. Microbiological Monitoring of Coagulase-Negative Staphylococcus in Public Drinking Water Fountains: Pathogenicity Factors, Antimicrobial Resistance and Potential Health Risks. Journal of Water and Health 2023, 21, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowoyo, P.T.; Ogunbanwo, S.T. Antimicrobial Resistance in Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci from Nigerian Traditional Fermented Foods. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials 2017, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünewald, T.; Wolfsperger, F. Water Losses During Technical Snow Production: Results From Field Experiments. Frontiers in Earth Science 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanham, D.; Fleischhacker, E.; Rauch, W. Technical Note: Seasonality in Alpine Water Resources Management - A Regional Assessment. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2008, 12, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulik, K.; Lenart-Boroń, A.; Wyrzykowska, K. Impact of Antibiotic Pollution on the Bacterial Population within Surface Water with Special Focus on Mountain Rivers. Water 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankiewicz, K.; Boroń, P.; Prajsnar, J.; Żelazny, M.; Heliasz, M.; Hunter, W.; Lenart-Boroń, A. Second Life of Water and Wastewater in the Context of Circular Economy - Do the Membrane Bioreactor Technology and Storage Reservoirs Make the Recycled Water Safe for Further Use? The Science of the total environment 2024, 921, 170995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenart-Boroń, A.; Wolanin, A.A.; Jelonkiewicz, Ł.; Żelazny, M. Factors and Mechanisms Affecting Seasonal Changes in the Prevalence of Microbiological Indicators of Water Quality and Nutrient Concentrations in Waters of the Białka River Catchment, Southern Poland. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution 2016, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijazin, M.; Hassan, A.A.; Alber, J.; Lämmler, C.; Timke, M.; Kostrzewa, M.; Prenger-Berninghoff, E.; Zschöck, M. Evaluation of Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) for Species Identification of Bacteria of Genera Arcanobacterium and Trueperella. Veterinary Microbiology 2012, 157, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, A.W.; Kirby, W.M.; Sherris, J.C.; Turck, M. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing by a Standardized Single Disk Method. American journal of clinical pathology 1966, 45, 493–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EUCAST European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. http://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_5.0_Breakpoint_Table_01.pdf 2023, 0–77.

- Magiorakos, A.-P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-Resistant, Extensively Drug-Resistant and Pandrug-Resistant Bacteria: An International Expert Proposal for Interim Standard Definitions for Acquired Resistance. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiebelkorn, K.R.; Crawford, S.A.; McElmeel, M.L.; Jorgensen, J.H. Practical Disk Diffusion Method for Detection of Inducible Clindamycin Resistance in Staphylococcus Aureus and Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci. Journal of clinical microbiology 2003, 41, 4740–4744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.M.; Domingo, J.W.S.; Meckes, M.C.; Kelty, C.A.; Rochon, H.S. Phylogenetic Diversity of Drinking Water Bacteria in a Distribution System Simulator. Journal of applied microbiology 2004, 96, 954–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michels, R.; Last, K.; Becker, S.L.; Papan, C. Update on Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci—What the Clinician Should Know. Microorganisms 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosecka-Strojek, M.; Wolska-Gębarzewska, M.; Podbielska-Kubera, A.; Samet, A.; Krawczyk, B.; Międzobrodzki, J.; Michalik, M. May Staphylococcus Lugdunensis Be an Etiological Factor of Chronic Maxillary Sinuses Infection? International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravaioli, S.; De Donno, A.; Bottau, G.; Campoccia, D.; Maso, A.; Dolzani, P.; Balaji, P.; Pegreffi, F.; Daglia, M.; Arciola, C.R. The Opportunistic Pathogen Staphylococcus Warneri: Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance, Clinical Features, Association with Orthopedic Implants and Other Medical Devices, and a Glance at Industrial Applications. Antibiotics 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Lu, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Wen, G.; Luo, Q.; Shao, H.; Zhang, T. High Concentration of Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Carriage among Bioaerosols of Henhouses in Central China. BMC Microbiology 2020, 20, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ripa, L.; Gómez, P.; Alonso, C.A.; Camacho, M.C.; Ramiro, Y.; de la Puente, J.; Fernández-Fernández, R.; Quevedo, M.Á.; Blanco, J.M.; Báguena, G.; et al. Frequency and Characterization of Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Genes of Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci from Wild Birds in Spain. Detection of Tst-Carrying S. Sciuri Isolates. Microorganisms 2020, 8.

- Yeamans, S.; Gil-de-Miguel, Á.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Carrasco-Garrido, P. Self-Medication among General Population in the European Union: Prevalence and Associated Factors. European Journal of Epidemiology 2024, 39, 977–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD Fighting Antimicrobial Resistance in EU and EEA Countries. 2023.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Antimicrobial Consumption in the EU/EEA (ESAC-Net) - Annual Epidemiological Report for 2022. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control 2023, 1–27.

- ECDC Country Summaries - Antimicrobial Resistance in the EU/EEA 2022. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2023. 2023.

- Nava, A.R.; Daneshian, L.; Sarma, H. Antibiotic Resistant Genes in the Environment-Exploring Surveillance Methods and Sustainable Remediation Strategies of Antibiotics and ARGs. Environmental Research 2022, 215, 114212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baloh, P.; Els, N.; David, R.O.; Larose, C.; Whitmore, K.; Sattler, B.; Grothe, H. Assessment of Artificial and Natural Transport Mechanisms of Ice Nucleating Particles in an Alpine Ski Resort in Obergurgl, Austria. Frontiers in microbiology 2019, 10, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Mode of action | Primer sequence (5′-3′) | Amplicon size (bp) | Annealing temperature (°C) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mecA | alternative penicillin-binding protein, PBP 2a | F: GTAGAAAATGACTGAACGTCCGATAA R: CCAATTCCACATTGTTTCGGTCTAA |

310 | 55 | (Geha et al. 1994) |

| msrA | macrolide efflux protein | F: GGCACAATAAGAGTGTTTAAAGG R: AAGTTATATCATGAATAGATTGTCCTGTT |

940 | 50 | (Lina et al. 1999) |

| ereA | macrolide lactone esterase | F: AACACCCTGAACCCAAGGGACG R: CTTCACATCCGGATTCGCTCGA |

420 | 57 | (Sutcliffe et al. 1996) |

| mphA | macrolide-active phosphotransferase | F: AACTGTACGCACTTGC R: GGTACTCTTCGTTACC |

837 | 50 | (Sutcliffe et al. 1996) |

| lnuA | lincosamide nucleotidyltransferase | F: GGTGGCTGGGGGGTAGATGTATTAACTGG R: GCTTCTTTTGAAATACATGGTATTTTTCGATC |

323 | 57 | (Lina et al. 1999) |

| vga | ABC-F subfamily protein conferring resistance to streptogramin A | F: CCAGAACTGCTATTAGCAGATGAA R: AAGTTCGTTTCTCTTTTCGACG |

470 | 54 | (Lina et al. 1999) |

| No. | Species | River catchment* | Type of sample** | Antibiotic resistance phenotype*** | Antibiotic resistance genes |

| 1 |

S. epidermidis n=10 |

B=4, BD=0 R=0, W=0 S=6 |

W=7 R=0 S=3 |

FOX (1), E (8), DA (0), TE (0), CIP (2), SXT (1), CN (0), TOB (0), MSB (8), cMLSB (0), iMLSB (0), MDR (0) | mecA (7), msrA (8), ereA (0), mphA (0), lnuA (0), vga (0) |

| 2 |

S. haemolyticus n=13 |

B=1, BD=3 R=8, W=1 S=0 |

W=1 R=0 S=12 |

FOX (2), E (11), DA (1), TE (7), CIP (1), SXT (0), CN (4), TOB (3), MSB (1), cMLSB (1), iMLSB (9), MDR (2) | mecA (1), msrA (6), ereA (0), mphA (0), lnuA (5), vga (3) |

| 3 |

S. lugdunensis n=2 |

B=0, BD=1 R=1, W=0 S=0 |

W=0 R=0 S=2 |

FOX (0), E (1), DA (1), TE (0), CIP (0), SXT (0), CN (1), TOB (1), MSB (0), cMLSB (1), iMLSB (0), MDR (1) | mecA (0), msrA (1), ereA (0), mphA (0), lnuA (1), vga (1) |

| 4 |

S. warneri n=19 |

B=2, BD=6 R=7, W=0 S=4 |

W=6 R=3 S=10 |

FOX (0), E (9), DA (1), TE (0), CIP (1), SXT (1), CN (0), TOB (1), MSB (7), cMLSB (0), iMLSB (0), MDR (0) | mecA (0), msrA (12), ereA (0), mphA (0), lnuA (0), vga (2) |

| 5 |

S. pasteuri n=4 |

B=0, BD=3 R=0, W=1 S=0 |

W=0 R=3 S=1 |

FOX (0), E (3), DA (0), TE (1), CIP (0), SXT (0), CN (0), TOB (0), MSB (3), cMLSB (0), iMLSB (0), MDR (0) | mecA (0), msrA (1), ereA (0), mphA (0), lnuA (0), vga (0) |

| 6 |

S. equorum n= 8 |

B=0, BD=7 R=1, W=0 S=0 |

W=5 R=2 S=1 |

FOX (1), E (1), DA (0), TE (0), CIP (0), SXT (0), CN (0), TOB (0), MSB (1), cMLSB (0), iMLSB (0), MDR (0) | mecA (0), msrA (3), ereA (0), mphA (1), lnuA (0), vga (0) |

| 7 |

S. xylosus n=3 |

B=0, BD=2 R=1, W=0 S=0 |

W=2 R=0 S=1 |

FOX (0), E (1), DA (0), TE (0), CIP (0), SXT (0), CN (0), TOB (0), MSB (0), cMLSB (0), iMLSB (1), MDR (0) | mecA (0), msrA (0), ereA (0), mphA (0), lnuA (0), vga (0) |

| 8 |

S. hominis n=1 |

B=0, BD=1 R=0, W=0 S=0 |

W=0 R=0 S=1 |

FOX (0), E (1), DA (0), TE (0), CIP (0), SXT (0), CN (0), TOB (0), MSB (0), cMLSB (0), iMLSB (1), MDR (0) | mecA (0), msrA (0), ereA (0), mphA (0), lnuA (0), vga (0) |

| 9 |

S. cohnii n=2 |

B=0, BD=0 R=1, W=0 S=1 |

W=1 R=0 S=1 |

FOX (0), E (1), DA (1), TE (0), CIP (0), SXT (0), CN (0), TOB (0), MSB (0), cMLSB (1), iMLSB (0), MDR (0) | mecA (1), msrA (2), ereA (0), mphA (0), lnuA (0), vga (1) |

| 10 |

S. capitis n=1 |

B=0, BD=0 R=0, W=1 S=0 |

W=0 R=0 S=1 |

FOX (0), E (1), DA (0), TE (0), CIP (0), SXT (0), CN (0), TOB (0), MSB (1), cMLSB (0), iMLSB (0), MDR (0) | mecA (0), msrA (1), ereA (0), mphA (0), lnuA (0), vga (0) |

| 11 |

Staphylococcus sp. n=12 |

B=8, BD=1 R=1, W=2 S=0 |

W=3 R=0 S=9 |

FOX (1), E (6), DA (0), TE (0), CIP (0), SXT (0), CN (0), TOB (1), MSB (6), cMLSB (0), iMLSB (0), MDR (0) | mecA (0), msrA (10), ereA (0), mphA (0), lnuA (1), vga (3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).