Submitted:

10 September 2025

Posted:

11 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

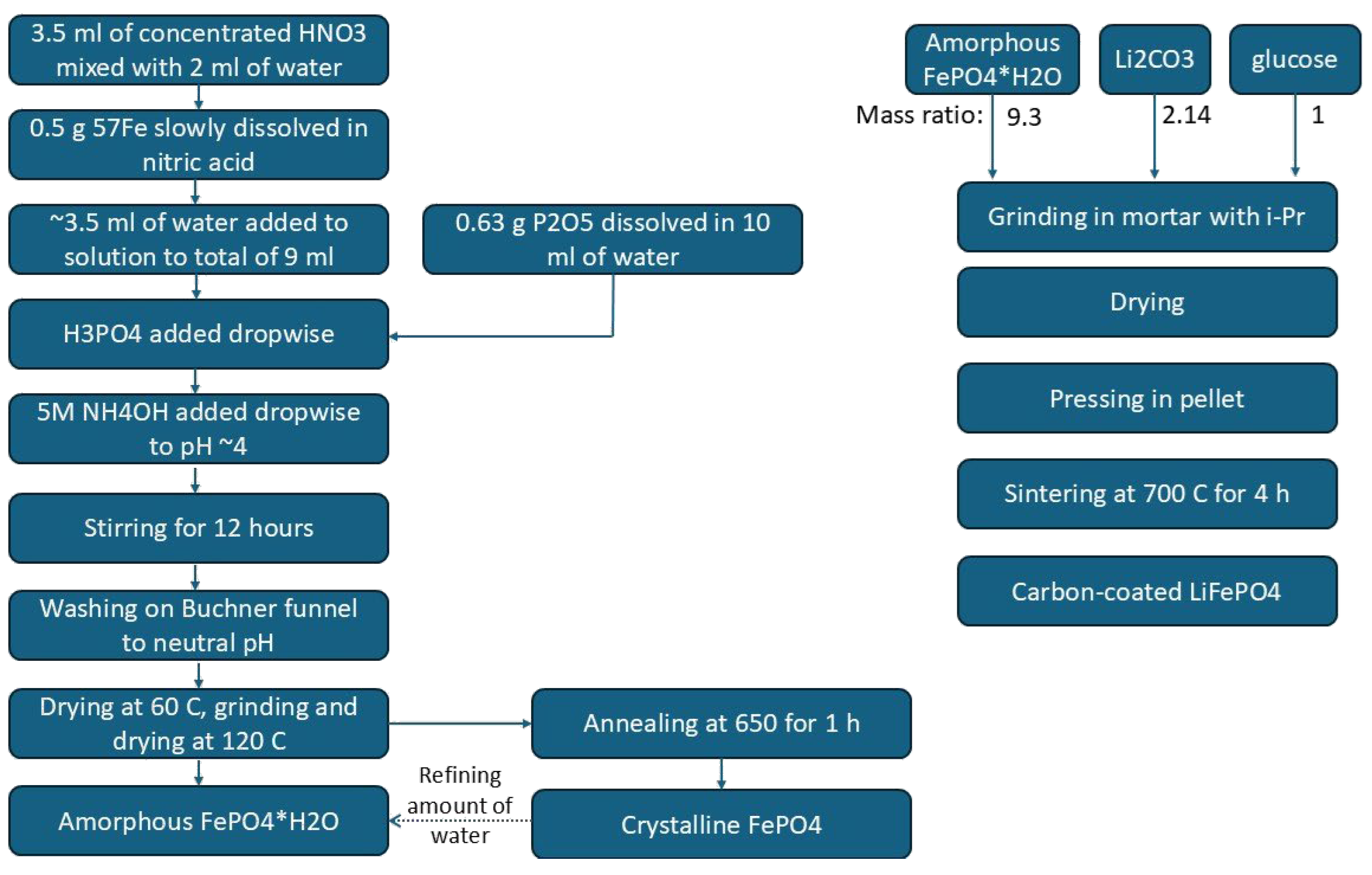

2.1. Synthesis

2.2. Pouch Cell Battery Assembly

2.3. Battery Charging and Discharging

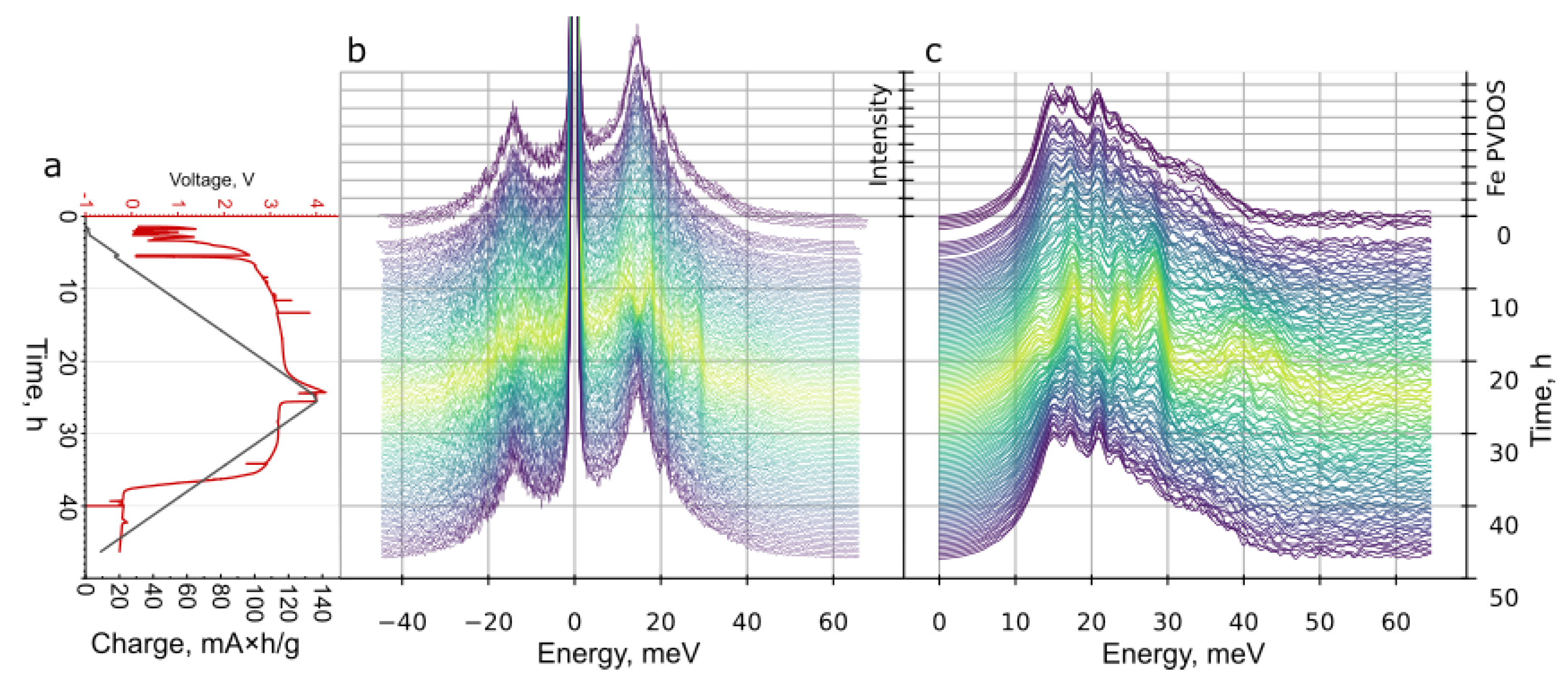

2.4. Nuclear Resonant Vibration Spectroscopy

2.5. Optical Raman Spectroscopy

2.6. Calculation of Total and Partial Vibrational Density of States (PVDOS)

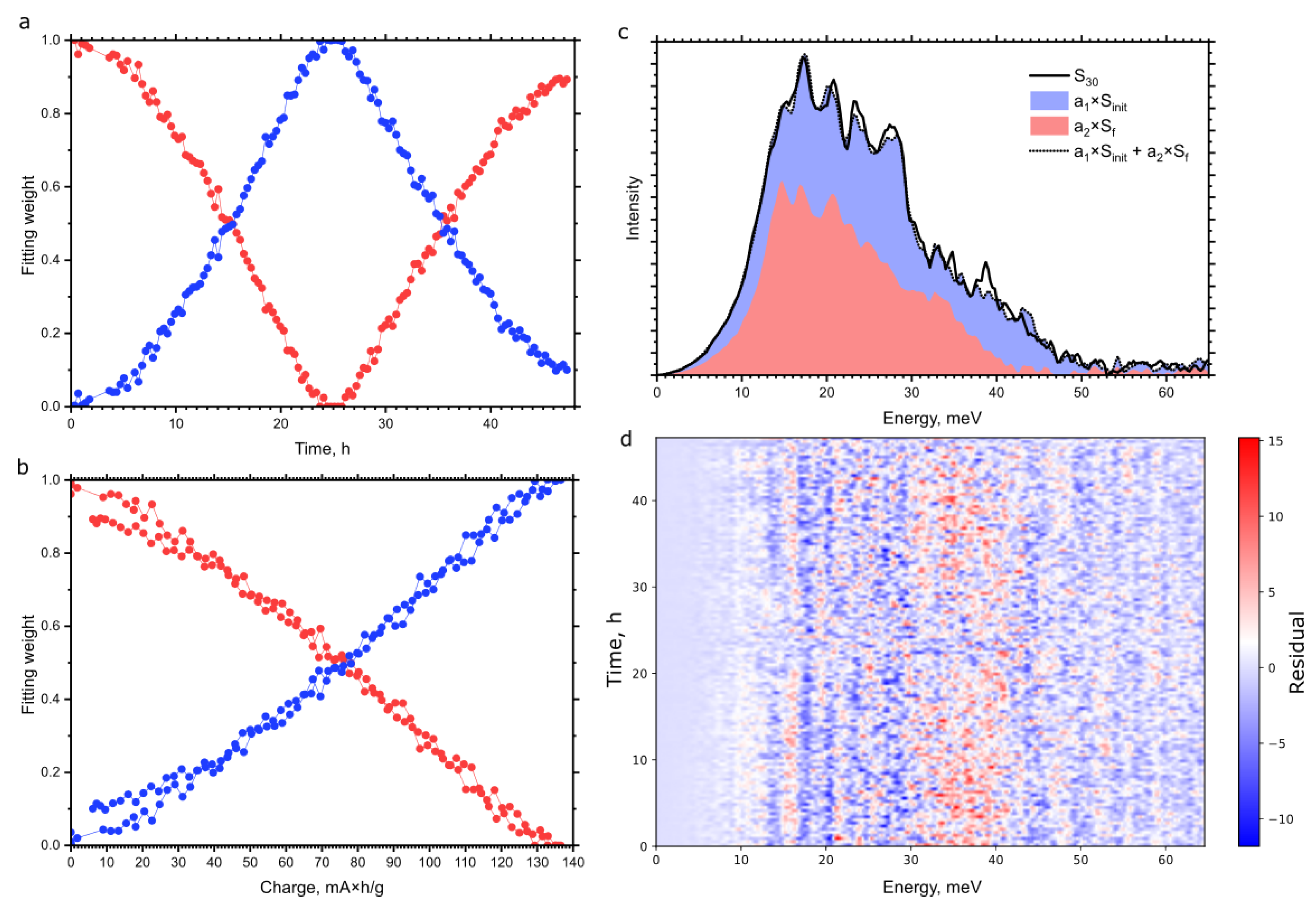

3. Results and Discussion

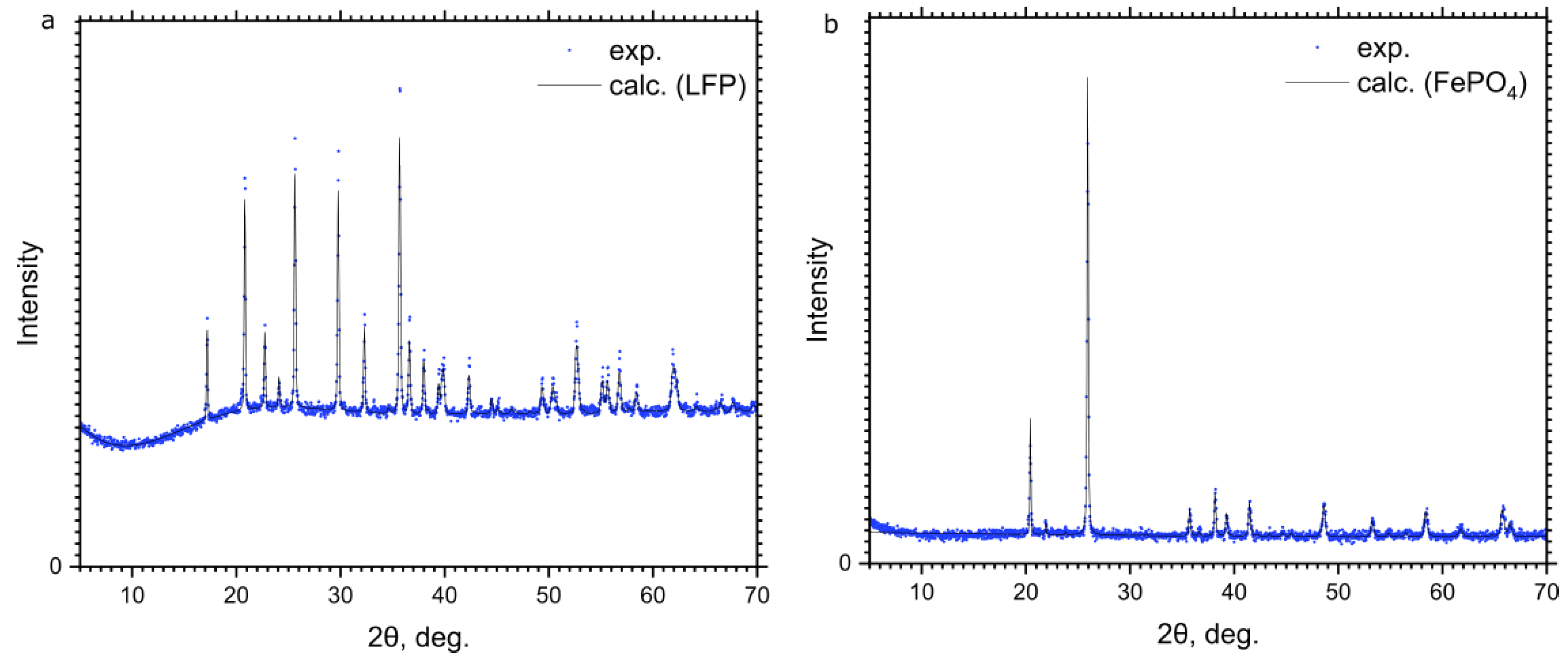

3.1. Crystallographic Structure

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PDOS | Phonon Density of States |

| NRVS | Nuclear Resonant Vibration Spectroscopy |

| LFP | Lithium Iron Phosphate |

| IR | Infra-Red |

| FP | Iron Phosphate |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

| NMP | N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidon |

| DOS | Density of States |

| PVDOS | Partial Vibrational Density of States |

| NAC | non-analytical term correction |

References

- Evro, S.; Ajumobi, A.; Mayon, D.; Tomomewo, O.S. Navigating battery choices: A comparative study of lithium iron phosphate and nickel manganese cobalt battery technologies. Future Batteries 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Noh, C.; Cho, A.Y.; Kim, J.C.; Kim, N.; Kim, K.H. Enhancing 1D ionic conductivity in lithium manganese iron phosphate with low-energy optical phonons. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 28421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagotra, A.K.; Chu, D.; Cazorla, C. Influence of lattice dynamics on lithium-ion conductivity: A first-principles study. Physical Review Materials 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muy, S.; Schlem, R.; Shao-Horn, Y.; Zeier, W.G. Phonon–Ion Interactions: Designing Ion Mobility Based on Lattice Dynamics. Advanced Energy Materials 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosser, T.E.; Dickinson, E.J.F.; Raccichini, R.; Hunter, K.; Searle, A.D.; Kavanagh, C.M.; Curran, P.J.; Hinds, G.; Park, J.; Wain, A.J. Improved Operando Raman Cell Configuration for Commercially-Sourced Electrodes in Alkali-Ion Batteries. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2021, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghib, K.; Mauger, A.; Goodenough, J.B.; Julien, C.M. Design and Properties of LiFePO4 Nano-materials for High-Power Applications. In Nanotechnology for Lithium-Ion Batteries; Nanostructure Science and Technology; 2012; pp. 179-220.

- Wang, H.; Braun, A.; Cramer, S.P.; Gee, L.B.; Yoda, Y. Nuclear Resonance Vibrational Spectroscopy: A Modern Tool to Pinpoint Site-Specific Cooperative Processes. Catalysts 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.M.; Fisher, K.; Smith, M.C.; Newton, W.E.; Case, D.A.; George, S.J.; Wang, H.X.; Sturhahn, W.; Alp, E.E.; Zhao, J.Y.; et al. How nitrogenase shakes - Initial information about P-cluster and FeMo-cofactor normal modes from nuclear resonance vibrational Spectroscopy (NRVS). Journal of the American Chemical Society 2006, 128, 7608–7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rulev, A.; Wang, H.; Erat, S.; Aycibin, M.; Rentsch, D.; Pomjakushin, V.; Cramer, S.P.; Chen, Q.; Nagasawa, N.; Yoda, Y.; et al. 119Sn Element-Specific Phonon Density of States of BaSnO3. Crystals 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Tang, S.; Shi, H.; Hu, H. Synthesis of FePO4·xH2O for fabricating submicrometer structured LiFePO4/C by a co-precipitation method. Ceramics International 2014, 40, 2685–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, A.Q.R.; Tanaka, Y.; Miwa, D.; Ishikawa, D.; Mochizuki, T.; Takeshita, K.; Goto, S.; Matsushita, T.; Kimura, H.; Yamamoto, F.; et al. Early commissioning of the SPring-8 beamline for high resolution inelastic X-ray scattering. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2001, 467-468, 627–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoda, Y. X-ray beam properties available at the nuclear resonant scattering beamline at SPring-8. Hyperfine Interactions 2019, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprouse, G.D.; Hanna, S.S. Gamma ray transitions in 57Fe. Nuclear Physics 1965, 74, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, L.B.; Wang, H.; Cramer, S.P. NRVS for Fe in Biology: Experiment and Basic Interpretation. Methods Enzymol. 2018, 599, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturhahn, W. CONUSS and PHOENIX: Evaluation of nuclear resonant scattering data. Hyperfine Interactions 2000, 125, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Dathar, G.K.; Sun, C.; Theivanayagam, M.G.; Applestone, D.; Dylla, A.G.; Manthiram, A.; Henkelman, G.; Goodenough, J.B.; Stevenson, K.J. In situ Raman spectroscopy of LiFePO4: size and morphology dependence during charge and self-discharge. Nanotechnology 2013, 24, 424009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Brow, R.K. A Raman Study of Iron–Phosphate Crystalline Compounds and Glasses. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 2011, 94, 3123–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, X.; Shi, Y.; Li, J.; Li, G.; Chen, Z.; Chen, S.; Zeni, C.; et al. MatterSim: A Deep Learning Atomistic Model Across Elements, Temperatures and Pressures. 2024; arXiv:2405.04967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togo, A. First-principles Phonon Calculations with Phonopy and Phono3py. Journal of the Physical Society of Japan 2023, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togo, A.; Chaput, L.; Tadano, T.; Tanaka, I. Implementation strategies in phonopy and phono3py. J Phys Condens Matter 2023, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannozzi, P.; Baroni, S.; Bonini, N.; Calandra, M.; Car, R.; Cavazzoni, C.; Ceresoli, D.; Chiarotti, G.L.; Cococcioni, M.; Dabo, I.; et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J Phys Condens Matter 2009, 21, 395502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannozzi, P.; Andreussi, O.; Brumme, T.; Bunau, O.; Buongiorno Nardelli, M.; Calandra, M.; Car, R.; Cavazzoni, C.; Ceresoli, D.; Cococcioni, M.; et al. Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with Quantum ESPRESSO. J Phys Condens Matter 2017, 29, 465901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannozzi, P.; Baseggio, O.; Bonfa, P.; Brunato, D.; Car, R.; Carnimeo, I.; Cavazzoni, C.; de Gironcoli, S.; Delugas, P.; Ferrari Ruffino, F.; et al. Quantum ESPRESSO toward the exascale. J Chem Phys 2020, 152, 154105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halankar, K.K.; Mandal, B.P.; Jangid, M.K.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Meena, S.S.; Acharya, R.; Tyagi, A.K. Optimization of lithium content in LiFePO(4) for superior electrochemical performance: the role of impurities. RSC Adv 2018, 8, 1140–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.Q.; Scholes, C.A.; Qiao, G.G.; Kentish, S.E. Water vapor permeation in polyimide membranes. Journal of Membrane Science 2011, 379, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GmbH, C.K. Water vapor permeability of various plastic films. Available online: https://www.cmc.de/en/blog/know-how-5/water-vapor-permeability-of-various-plastic-films-181 (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Su, L.; Choi, P.; Parimalam, B.S.; Litster, S.; Reeja-Jayan, B. Designing reliable electrochemical cells for operando lithium-ion battery study. MethodsX 2021, 8, 101562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, S.-M.; Shadike, Z.; Lin, R.; Yu, X.; Yang, X.-Q. In situ/operando synchrotron-based X-ray techniques for lithium-ion battery research. NPG Asia Materials 2018, 10, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, S.; Natsui, R.; Yamada, A. Superstructure in the Metastable Intermediate-Phase Li2/3 FePO4 Accelerating the Lithium Battery Cathode Reaction. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2015, 54, 8939–8942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orikasa, Y.; Maeda, T.; Koyama, Y.; Murayama, H.; Fukuda, K.; Tanida, H.; Arai, H.; Matsubara, E.; Uchimoto, Y.; Ogumi, Z. Direct observation of a metastable crystal phase of Li(x)FePO4 under electrochemical phase transition. J Am Chem Soc 2013, 135, 5497–5500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrick, J.P.; Moran, D.; Radom, L. An evaluation of harmonic vibrational frequency scale factors. J Phys Chem A 2007, 111, 11683–11700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedek, P.; Yazdani, N.; Chen, H.R.; Wenzler, N.; Juranyi, F.; Månsson, M.; Islam, M.S.; Wood, V.C. Surface phonons of lithium ion battery active materials. Sustainable Energy & Fuels 2019, 3, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loew, A.; Sun, D.; Wang, H.-C.; Botti, S.; Marques, M.A.L. Universal machine learning interatomic potentials are ready for phonons. npj Computational Materials 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, N.A.; Salehi, A.; Wei, Z.; Liu, D.; Sajjad, S.D.; Liu, F. Length-Scale-Dependent Phase Transformation of LiFePO4 : An In situ and Operando Study Using Micro-Raman Spectroscopy and XRD. Chemphyschem 2015, 16, 2383–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muy, S.; Bachman, J.C.; Giordano, L.; Chang, H.-H.; Abernathy, D.L.; Bansal, D.; Delaire, O.; Hori, S.; Kanno, R.; Maglia, F.; et al. Tuning mobility and stability of lithium ion conductors based on lattice dynamics. Energy & Environmental Science 2018, 11, 850–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Isotope: | Fe-54 | Fe-56 | Fe-57 | Fe-58 |

| Content (at. %): | 0.005 | 0.615 | 96.060 | 3.360 |

| Atom | Fraction |

| Fe | 1 |

| Li | 0.93(13) |

| P | 1.025(30) |

| O1 | 0.84(7) |

| O2 | 0.86(6) |

| O3 | 0.88(6) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).