Submitted:

29 August 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Computational Details

3. Results

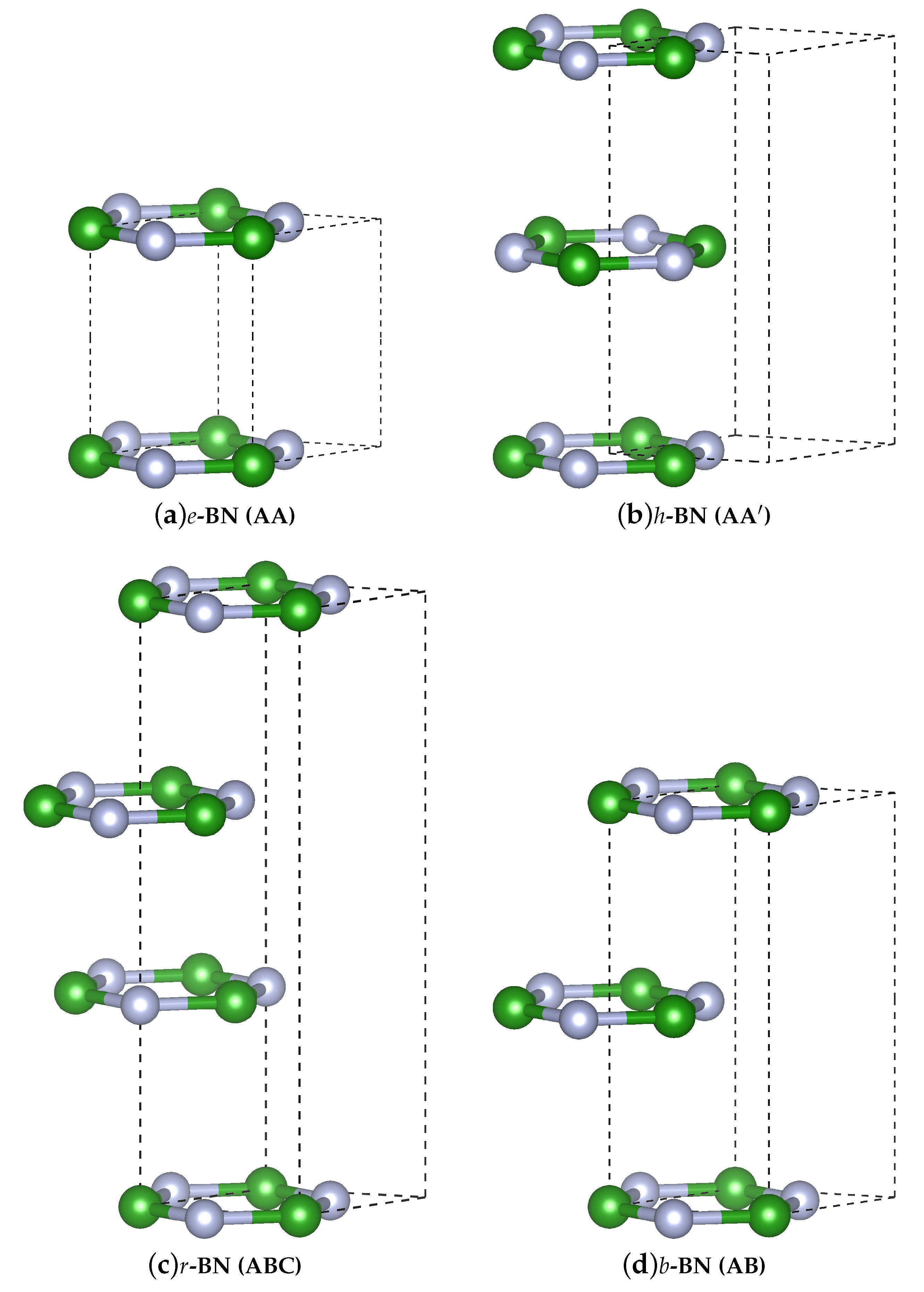

3.1. Crystal Structures for Different Polymorphs of BN

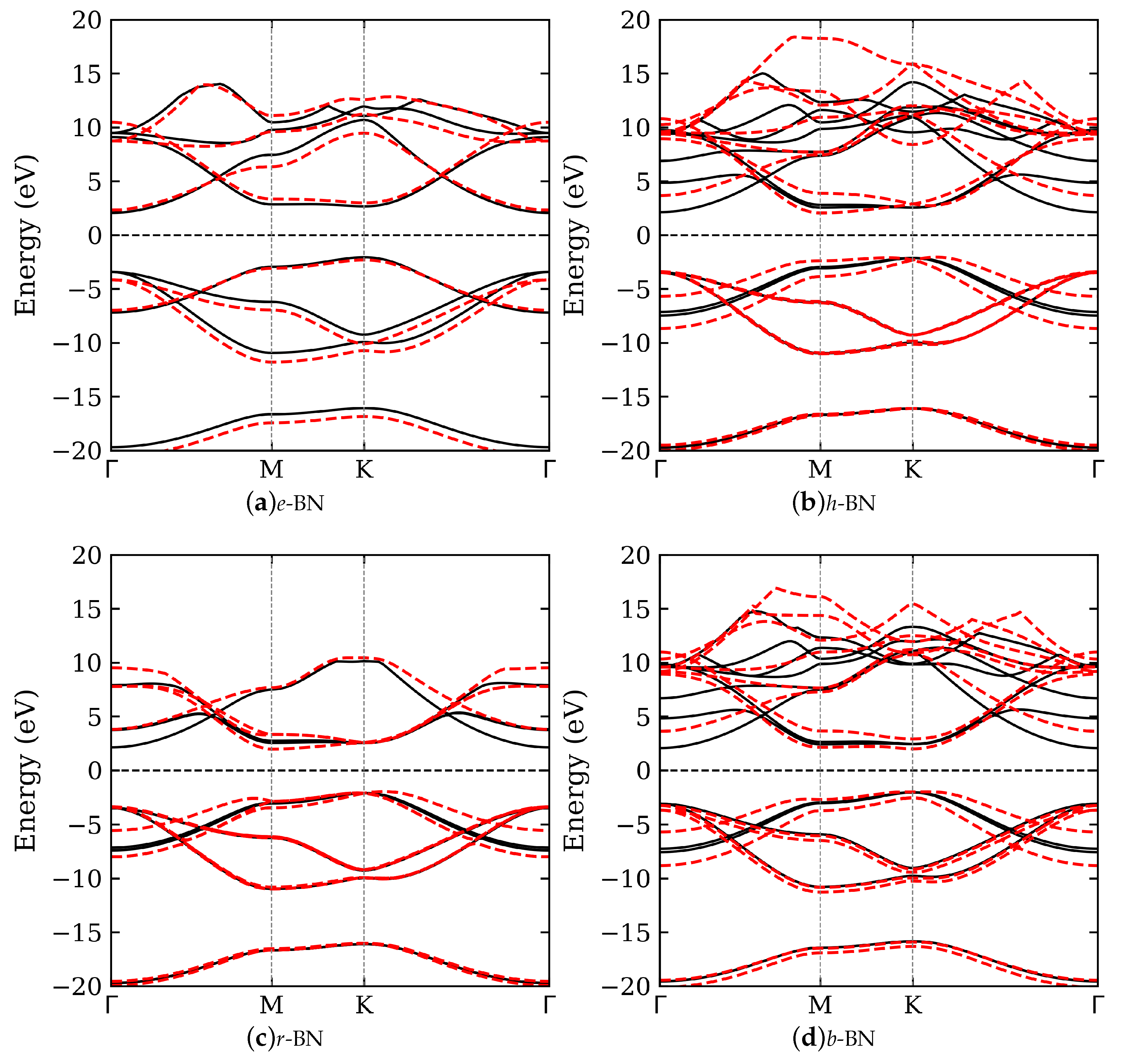

3.2. Electronic Band Structure

3.3. Phonon Frequencies

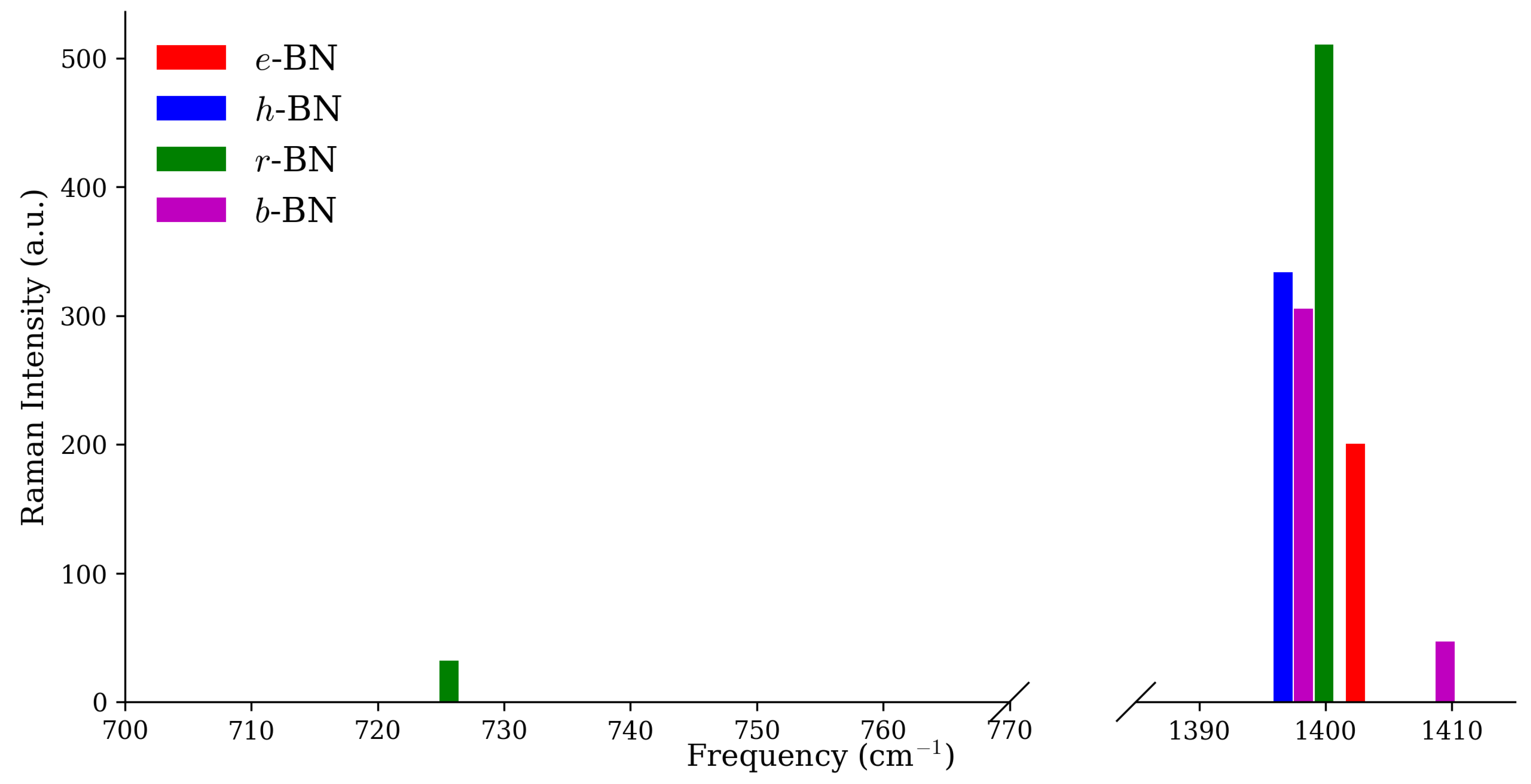

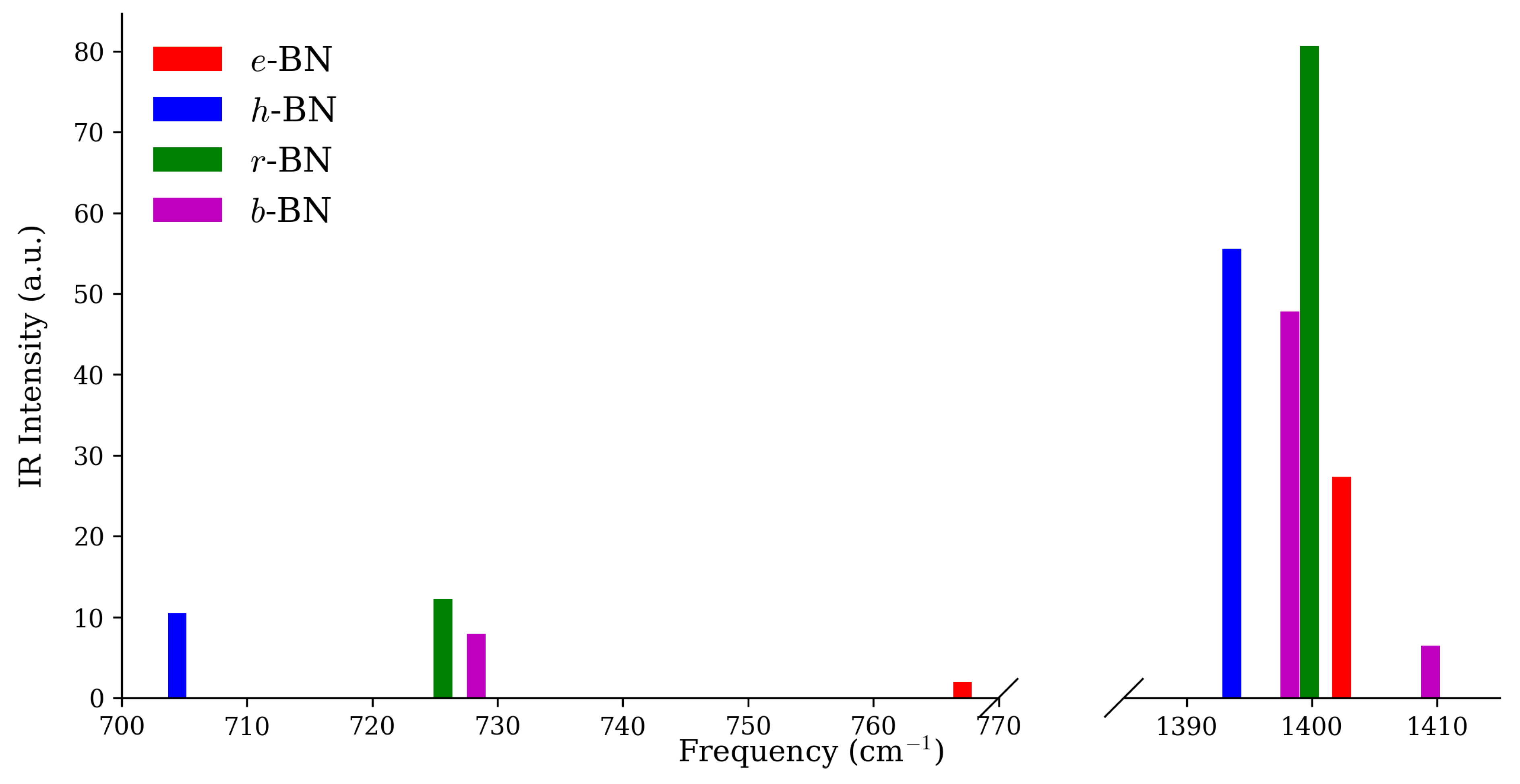

3.4. Raman and Infrared Intensities

4. Summary

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tan, T.; Jiang, X.; Wang, C.; Yao, B.; Zhang, H. 2D Material Optoelectronics for Information Functional Device Applications: Status and Challenges. Advanced Science 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, B.; Desrat, W.; Rousseau, A.; Elias, C.; Valvin, P.; Moret, M.; Li, J.; Janzen, E.; Edgar, J.H.; Cassabois, G. Polytypes of sp2-Bonded Boron Nitride. Crystals 2022, 12, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olovsson, W.; Magnuson, M. Rhombohedral and Turbostratic Boron Nitride Polytypes Investigated by X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2022, 126, 21101–21108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Feng, Y.P.; Shen, Z.X. Structural and electronic properties ofh-BN. Physical Review B 2003, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, S.M.; Pham, T.; Dogan, M.; Oh, S.; Shevitski, B.; Schumm, G.; Liu, S.; Ercius, P.; Aloni, S.; Cohen, M.L.; et al. Alternative stacking sequences in hexagonal boron nitride. 2D Materials 2019, 6, 021006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotný, M.; Dubecký, M.; Karlický, F. Toward accurate modeling of structure and energetics of bulk hexagonal boron nitride. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2023, 45, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ordin, S.V.; Sharupin, B.N.; Fedorov, M.I. Normal lattice vibrations and the crystal structure of anisotropic modifications of boron nitride. Semiconductors 1998, 32, 924–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazorla, C.; Gould, T. Polymorphism of bulk boron nitride. Science Advances 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikaido, Y.; Ichibha, T.; Hongo, K.; Reboredo, F.A.; Kumar, K.C.H.; Mahadevan, P.; Maezono, R.; Nakano, K. Diffusion Monte Carlo Study on Relative Stabilities of Boron Nitride Polymorphs. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2022, 126, 6000–6007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korona, T.; Chojecki, M. Exploring point defects in hexagonal boron-nitrogen monolayers. International Journal of Quantum Chemistry 2019, 119, e25925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinescu, G.; Kuc, A.; Heine, T. Stacking in Bulk and Bilayer Hexagonal Boron Nitride. Physical Review Letters 2013, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwański, J.; Korona, K.P.; Tokarczyk, M.; Kowalski, G.; Dąbrowska, A.K.; Tatarczak, P.; Rogala, I.; Bilska, M.; Wójcik, M.; Kret, S.; et al. Revealing polytypism in 2D boron nitride with UV photoluminescence. npj 2D Materials and Applications 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korona, K.P.; Binder, J.; Dąbrowska, A.K.; Iwański, J.; Reszka, A.; Korona, T.; Tokarczyk, M.; Stępniewski, R.; Wysmołek, A. Growth temperature induced changes of luminescence in epitaxial BN: from colour centres to donor–acceptor recombination. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 9864–9877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barone, V.; Casarin, M.; Forrer, D.; Pavone, M.; Sambi, M.; Vittadini, A. Role and effective treatment of dispersive forces in materials: Polyethylene and graphite crystals as test cases. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2009, 30, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, R.; e Aleem, F.; Hashemifar, S.J.; Akbarzadeh, H. First principles study of structural and electronic properties of different phases of boron nitride. Physica B: Condensed Matter 2007, 400, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Setten, M.; Giantomassi, M.; Bousquet, E.; Verstraete, M.; Hamann, D.; Gonze, X.; Rignanese, G.M. The PseudoDojo: Training and grading a 85 element optimized norm-conserving pseudopotential table. Computer Physics Communications 2018, 226, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | a [Å] | c [Å] | [eV] | [eV] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| e-BN (AA) | ||||

| without vdW | 2.514 | 5.059 | 7.064 | 4.12 (indirect, K–) |

| with vdW | 2.511 | 3.383 | 7.181 | 4.63 (indirect, K–) |

| literature | 2.476 [2] | 3.476 [2] | – | – |

| h-BN (AA′) | ||||

| without vdW | 2.515 | 9.136 | 7.065 | 4.25 (indirect, K–) |

| with vdW | 2.512 | 6.179 | 7.205 | 4.10 (indirect, K–M) |

| literature | 2.478 [2] | 6.354 [2] | 7.055 [15] | 4.25 [3] |

| r-BN (ABC) | ||||

| without vdW | 2.515 | 13.743 | 7.065 | 4.24 (indirect, K–) |

| with vdW | 2.511 | 9.168 | 7.207 | 3.94 (indirect, K–M) |

| literature | 2.476 [2] | 9.679 [2] | – | 4.21 [3] |

| b-BN (AB) | ||||

| without vdW | 2.514 | 9.229 | 7.065 | 4.11 (indirect, K–) |

| with vdW | 2.511 | 6.117 | 7.207 | 3.98 (direct, K–K) |

| literature | 2.477 [2] | 6.319 [2] | – | – |

| e-BN | h-BN | r-BN | b-BN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq. (no→vdW) | Mode | Freq. (no→vdW) | Mode | Freq. (no→vdW) | Mode | Freq. (no→vdW) | Mode |

| 783 → 757.2 | (I) | 0 → 39.6 | (R) | 0 → 37.3 | E (I+R) | 0 → 48.5 | (I+R) |

| 1343.5 → 1352.5 | (I+R) | 52.9 → 182.8 | (S) | 0 → 39.3 | E (I+R) | 55.2 → 180.0 | (I) |

| 781.1 → 723.0 | (I) | 0 → 150.2 | (I+R) | 781.6 → 732.0 | (I) | ||

| 803.0 → 792.1 | (S) | 49.2 → 159.2 | (I+R) | 803.0 → 793.9 | (I) | ||

| 1341.6 → 1349.3 | (I) | 778.5 → 730.6 | (I+R) | 1343.6 → 1351.9 | (I+R) | ||

| 1341.6 → 1350.3 | (R) | 799.2 → 795.7 | (I+R) | 1343.6 → 1358.7 | (I+R) | ||

| 801.4 → 797.8 | (I+R) | ||||||

| 1343.2 → 1353.1 | E (I+R) | ||||||

| 1343.2 → 1356.4 | E (I+R) | ||||||

| 1343.3 → 1356.4 | E (I+R) | ||||||

| Polymorph | Raman (cm) | Mode (R) | Intensity (R) [a.u.] | IR (cm) | Mode (IR) | Intensity (IR) [a.u.] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e-BN | 1402.4 | 200.54 | 1402.4 | 27.32 | ||

| h-BN(2) | 1396.7 | 333.68 | 704.4 | 10.50 | ||

| r-BN(3) | 1399.9 | E | 510.66 | 1399.9 | E | 80.66 |

| b-BN(4) | 1409.5 | 46.69 | 728.3 | 7.95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).