Submitted:

10 September 2025

Posted:

11 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Spectral Data and UAV Images

3.3. Soil Data

3.4. Agronomic Data

3.5. Model Development

3.5.1. Data Preprocessing

3.5.2. Predictor Variable Selection

3.5.3. Modeling

3.5.4. Hyperparameter Tuning for Random Forest Model

3.5.5. Python Code Implementation to Deploy the Model

3.5.6. Evaluation in Probable Scenarios

3. Results

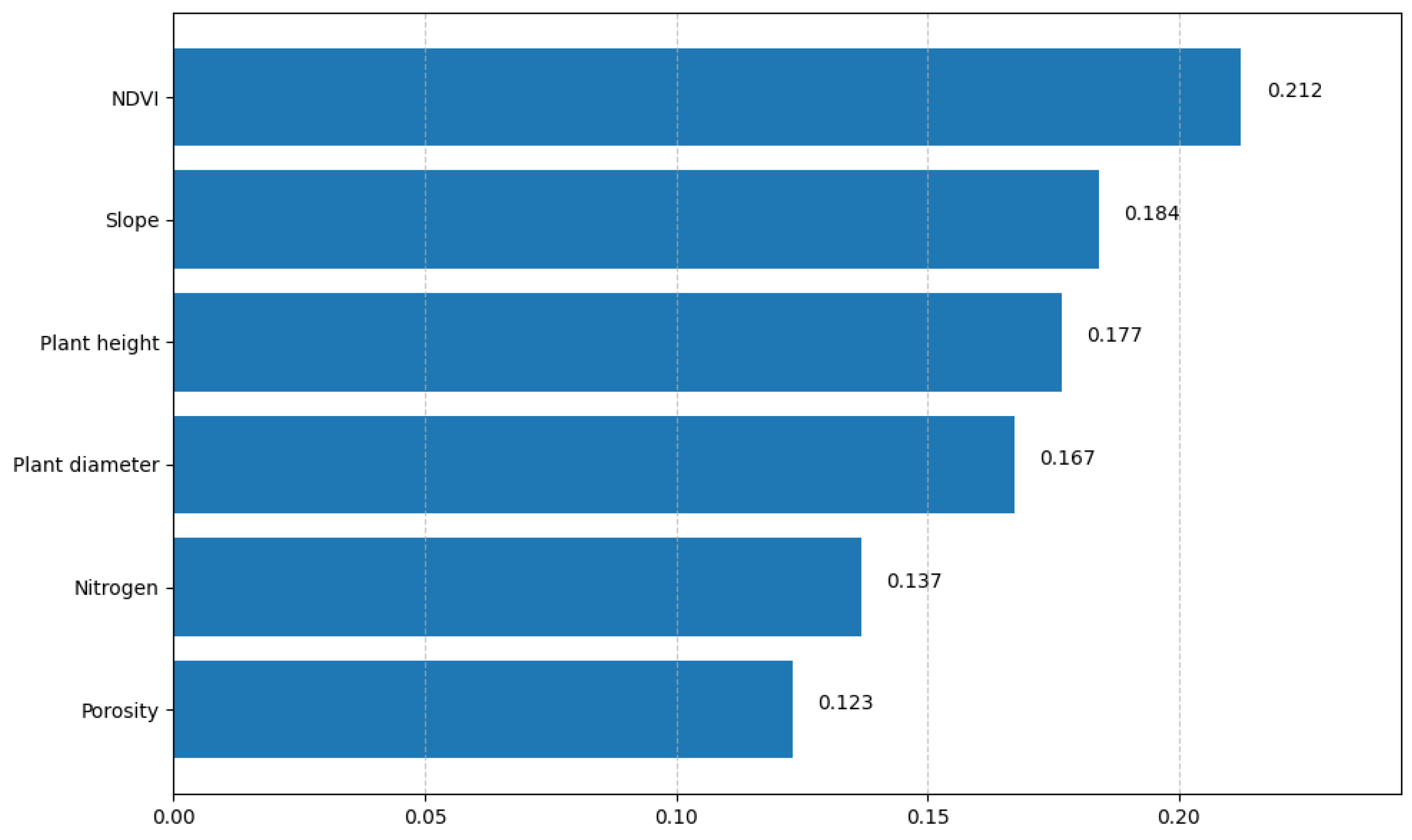

3.1. Predictor Variable Selection

| Variable | Type | Included | VIF | Main decision/reason |

| NDVI | Spectral | yes | 1.88 | Principal predictor; high correlation with yield |

| Plant height (m) | Agronomic | yes | 2.35 | Early indicator of vegetative vigor |

| Diameter (cm) | Agronomic | yes | 28.76 | Conserved for agronomic relevance (corrected VIF: 1.2) |

| Nitrogen (mg/kg) | Soil | yes | 3.21 | Key nutrient for crop development |

| Porosity (%) | Soil | yes | 6.99 | Conserved as physical soil indicator (corrected VIF: 1.8) |

| Slope | Topographic | yes | 1.05 | Transformed to ordinal; affects drainage and stability |

| Plant weight (pounds) | Agronomic | no | 31.25 | Excluded due to multicollinearity with diameter (r=0.97) |

| Moisture (%) | Soil | no | 7.12 | Excluded due to multicollinearity with porosity (r=0.83) |

| Density (g/cm3) | Soil | no | 15.43 | Excluded due to redundancy with porosity (r=-0.92) |

| Bunch weight (pounds) | yield | no | - | Excluded due to data leakage (yield component) |

| Number of hands | yield | no | 22.47 | Excluded for being component of label variable |

| Ratio | Calculated | no | 18.92 | Excluded due to ambiguous definition and multicollinearity |

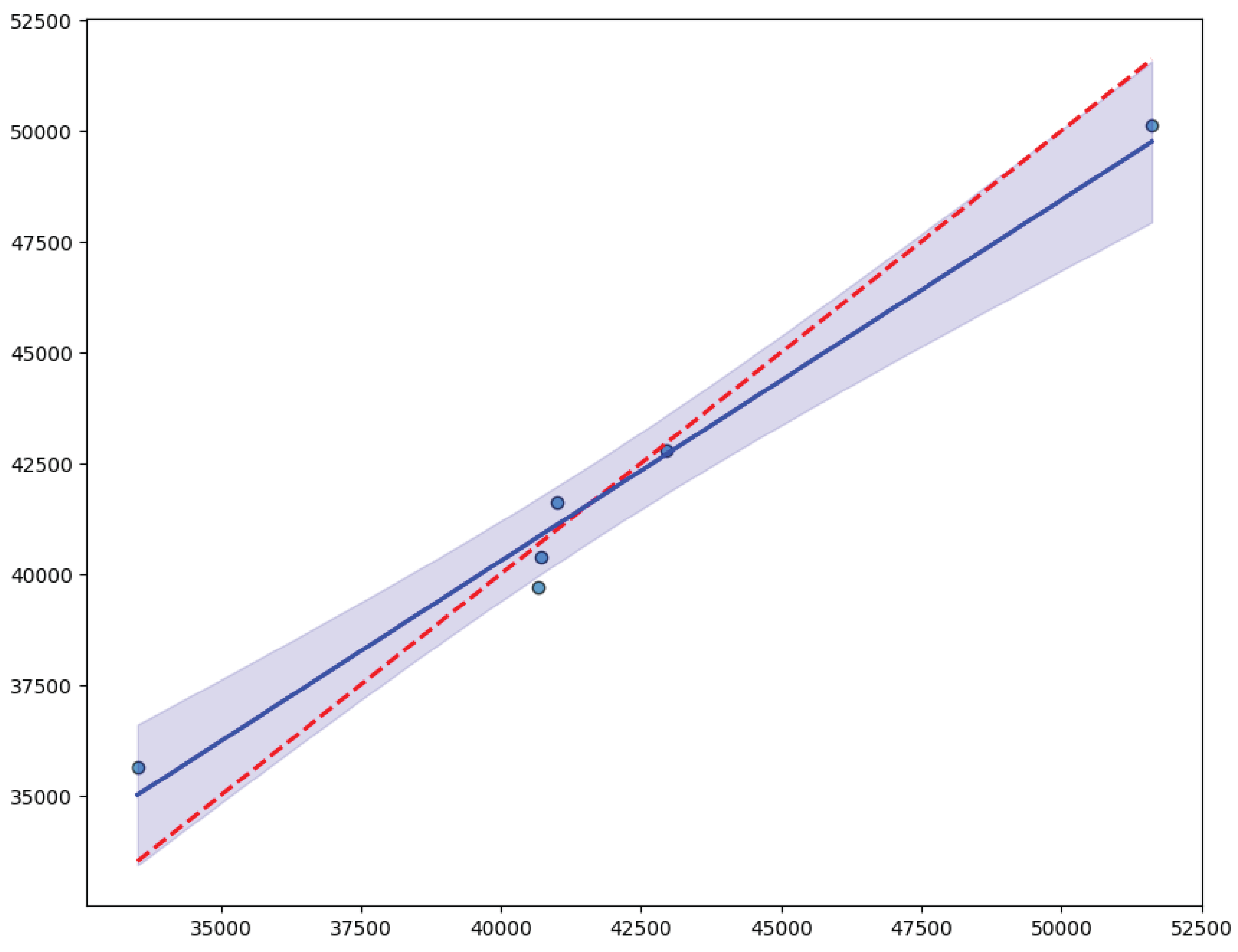

3.2. Modelamiento

| Model | Best hyperparameters | R2 | RMSE (kg ha-1) |

| Ridge Regression | α = 0.1 | 0.950 | 1223.4 |

| Random Forest | max_depth = 7, min_samples_split = 2, n_estimators = 150 | 0.956 | 1164.9 |

| Gradient Boosting | learning_rate = 0.1, max_depth = 3, n_estimators = 150 | 0.953 | 1190.2 |

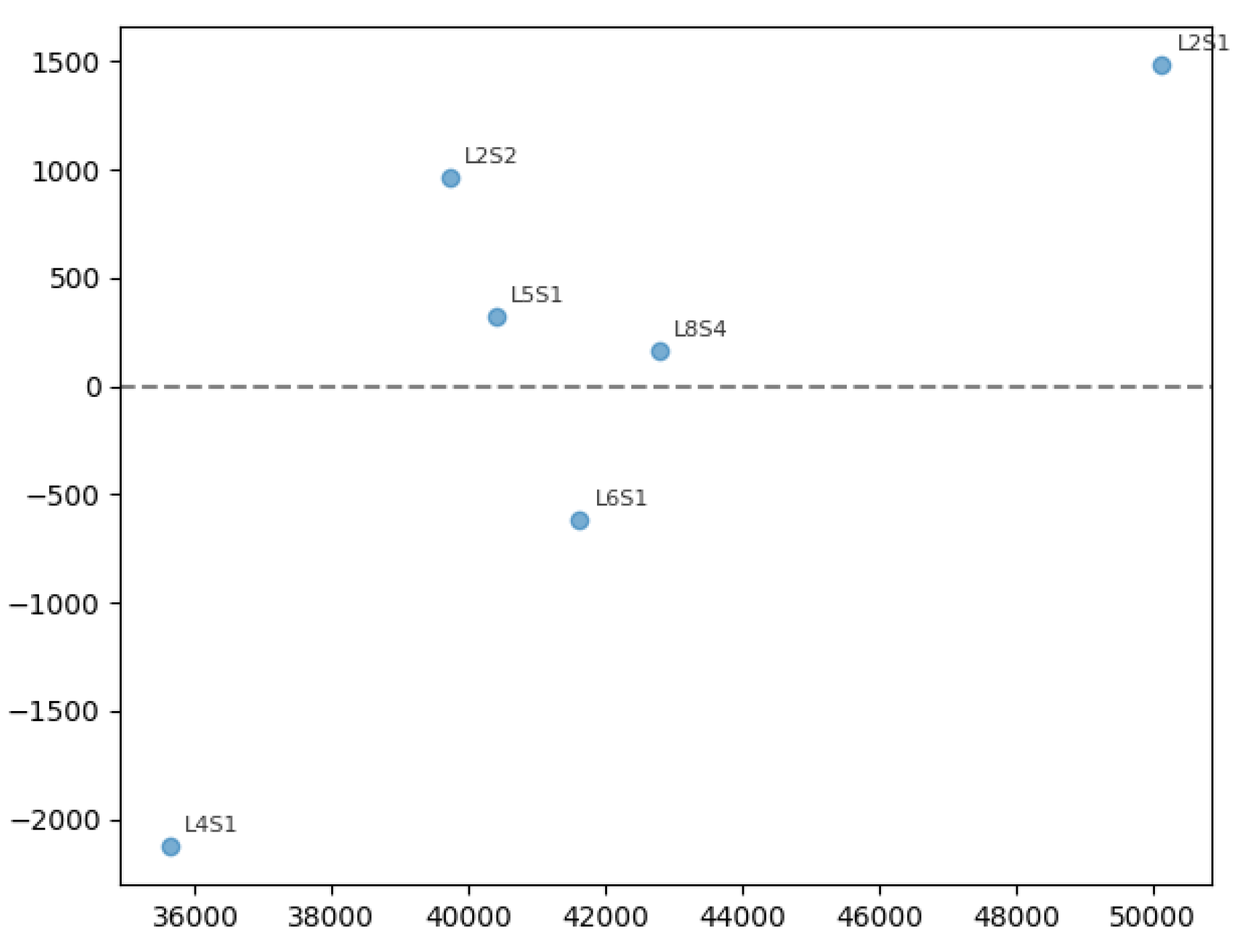

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Veliz, K.; Chico-Santamarta, L.; Ramirez, A.D. The Environmental Profile of Ecuadorian Export Banana: A Life Cycle Assessment. Foods 2022, 11, 3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roibás, L.; Elbehri, A.; Hospido, A. Evaluating the Sustainability of Ecuadorian Bananas: Carbon Footprint, Water Usage and Wealth Distribution along the Supply Chain. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2015, 2, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiloango-Chimarro, C.A.; Gioia, H.R.; de Oliveira Costa, J. Typology of Production Units for Improving Banana Agronomic Management in Ecuador. AgriEngineering 2024, 6, 2811–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, S.L.; Ranawana, C.J.K.; Liyanage, I.C.; Kaliyadasa, P.E. Growth and Yield Estimation of Banana through Mathematical Modelling: A Systematic Review. The Journal of Agricultural Science 2022, 160, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.C.B. da; Oliveira, F.G.; Braga, R.N. da F.G.P. Yield Prediction in Banana (Musa Sp.) Using STELLA Model. Acta Sci., Agron. 2023, 45, e58947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahi, T.B.; Xu, C.-Y.; Neupane, A.; Guo, W.; Shahi, T.B.; Xu, C.-Y.; Neupane, A.; Guo, W. Machine Learning Methods for Precision Agriculture with UAV Imagery: A Review. era 2022, 30, 4277–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeberli, A.; Phinn, S.; Johansen, K.; Robson, A.; Lamb, D.W. Characterisation of Banana Plant Growth Using High-Spatiotemporal-Resolution Multispectral UAV Imagery. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UAV Imaging: The Future of Yield Prediction Research. Pix4D 2021.

- Sönmez, F.; Ashyrov, P.; Toylan, H. Yield Prediction with Deep Learning on UAV Images: Banana Tree Application. KLUJES 2025, 11, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.; Jakeman, A.; Saltelli, A.; Prieur, C.; Iooss, B.; Borgonovo, E.; Plischke, E.; Lo Piano, S.; Iwanaga, T.; Becker, W.; et al. The Future of Sensitivity Analysis: An Essential Discipline for Systems Modeling and Policy Support. Environmental Modelling & Software 2021, 137, 104954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, B.O.; Rey, J.C.; Perichi, G.; Lobo, D. Relationship of Microbial Activity with Soil Properties in Banana Plantations in Venezuela. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, B.; Kathala, K.C.R.; Sujatha, M. A Machine Learning-Based Comparative Approach to Predict the Crop Yield Using Supervised Learning With Regression Models. Procedia Computer Science 2023, 218, 2684–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S. A Beginner’s Guide to Random Forest Hyperparameter Tuning. Analytics Vidhya 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahhosseini, M.; Hu, G.; Archontoulis, S.V.; Huber, I. Coupling Machine Learning and Crop Modeling Improves Crop Yield Prediction in the US Corn Belt. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MAG Boletín situacional cultivo de banano 2024.

- Delgado, D.; Sadaoui, M.; Ludwig, W.; Méndez, W. Spatio-Temporal Assessment of Rainfall Erosivity in Ecuador Based on RUSLE Using Satellite-Based High Frequency GPM-IMERG Precipitation Data. CATENA 2022, 219, 106597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DJI DJI MAVIC 3M, User Manual, v1.0 2022.

- Linero-Ramos, R.; Parra-Rodríguez, C.; Espinosa-Valdez, A.; Gómez-Rojas, J.; Gongora, M. Assessment of Dataset Scalability for Classification of Black Sigatoka in Banana Crops Using UAV-Based Multispectral Images and Deep Learning Techniques. Drones 2024, 8, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franaszek, M.; Qiao, H.; Saidi, K.S.; Rachakonda, P. A Method to Estimate Orientation and Uncertainty of Objects Measured Using 3D Imaging Systems per ASTM Standard E2919-22. NIST 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.; Anderson, J.; Shuart, W.; Woolard, J. An Evaluation of Reflectance Calibration Methods for UAV Spectral Imagery.

- PIX4D SA Pix4Dmapper 4.1, User Manual 2016.

- Poortinga, A.; Clinton, N.; Saah, D.; Cutter, P.; Chishtie, F.; Markert, K.N.; Anderson, E.R.; Troy, A.; Fenn, M.; Tran, L.H.; et al. An Operational Before-After-Control-Impact (BACI) Designed Platform for Vegetation Monitoring at Planetary Scale. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Su, B. Significant Remote Sensing Vegetation Indices: A Review of Developments and Applications. Journal of Sensors 2017, 2017, 1353691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QGIS Development Team QGIS Geographic Information System 2024.

- Tang, W.; Zhao, C.; Lin, J.; Jiao, C.; Zheng, G.; Zhu, J.; Pan, X.; Han, X. Improved Spectral Water Index Combined with Otsu Algorithm to Extract Muddy Coastline Data. Water 2022, 14, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Li, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Su, C.; Ou-yang, A. Detection of Early Bruises on Loquat Using Hyperspectral Imaging Technology Coupled with Band Ratio and Improved Otsu Method. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2022, 283, 121775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pansu, M.; Gautheyrou, J. Handbook of Soil Analysis: Mineralogical, Organic and Inorganic Methods; Springer Science & Business Media, 2007; ISBN 978-3-540-31211-6. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, B.; Diels, J.; Brown, A.; Bayo, S.; Ndakidemi, P.A.; Swennen, R. Banana Biomass Estimation and Yield Forecasting from Non-Destructive Measurements for Two Contrasting Cultivars and Water Regimes. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Wang, L.; Peng, C.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, M. Banana Plant Counting and Morphological Parameters Measurement Based on Terrestrial Laser Scanning. Plant Methods 2022, 18, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO Good Agricultural Practices for Bananas | World Banana Forum | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2017; Volume 1, 1–5.

- Lamessa, K. Performance Evaluation of Banana Varieties, through Farmer’s Participatory Selection. International Journal of Fruit Science 2021, 21, 768–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikulwe, E.M.; Kyanjo, J.L.; Kato, E.; Ssali, R.T.; Erima, R.; Mpiira, S.; Ocimati, W.; Tinzaara, W.; Kubiriba, J.; Gotor, E.; et al. Management of Banana Xanthomonas Wilt: Evidence from Impact of Adoption of Cultural Control Practices in Uganda. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, B.; Diels, J.; Brown, A.; Bayo, S.; Ndakidemi, P.A.; Swennen, R. Banana Biomass Estimation and Yield Forecasting from Non-Destructive Measurements for Two Contrasting Cultivars and Water Regimes. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Fu, H.; Yang, Z.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, T.; Liu, E.; Duan, J. Research on the Physical Characteristic Parameters of Banana Bunches for the Design and Development of Postharvesting Machinery and Equipment. Agriculture 2021, 11, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapetti, M.; Dorel, M. Bunch Weight Determination in Relation to the Source-Sink Balance in 12 Cavendish Banana Cultivars. Agronomy 2022, 12, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, S.L.R.; Silva, J.A. da; Guimarães, B.V.C.; Silva, S. de O. e Experimental Planning for the Evaluation of Phenotipic Descriptors in Banana. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2018, 40, e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Asten, P.J.A.; Fermont, A.M.; Taulya, G. Drought Is a Major Yield Loss Factor for Rainfed East African Highland Banana. Agricultural Water Management 2011, 98, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, M.; Tian, Z. Predicting Banana Yield at the Field Scale by Combining Sentinel-2 Time Series Data and Regression Models. Applied Engineering in Agriculture 2023, 39, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhajharia, K.; Mathur, P. Machine Learning Based Crop Yield Prediction Model in Rajasthan Region of India. Iraqi Journal of Science 2024, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayanda, M.S.; Didit, W.; Desta, S.P.; Jayanta; Wan, S.W.A. Prediction of Horticultural Production Using Machine Learning Regression Models: A Case Study from Indramayu Regency, Indonesia. Mathematical Modelling of Engineering Problems 2024, 11, 3015–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, B.O.; Calero, J.; Rey, J.C.; Lobo, D.; Landa, B.B.; Gómez, J.A. Correlation of Banana Productivity Levels and Soil Morphological Properties Using Regularized Optimal Scaling Regression. CATENA 2022, 208, 105718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiloango-Chimarro, C.A.; Gioia, H.R.; de Oliveira Costa, J. Typology of Production Units for Improving Banana Agronomic Management in Ecuador. AgriEngineering 2024, 6, 2811–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahhosseini, M.; Hu, G.; Archontoulis, S.V. Forecasting Corn Yield With Machine Learning Ensembles. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ennaji, O.; Baha, S.; Vergutz, L.; Allali, A.E. Gradient Boosting for Yield Prediction of Elite Maize Hybrid ZhengDan 958. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0315493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asamoah, E.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Chairi, I.; Bindraban, P.S.; Logah, V. Random Forest Machine Learning for Maize Yield and Agronomic Efficiency Prediction in Ghana. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, P.; Soundrapandiyan, R. Yield Prediction for Crops by Gradient-Based Algorithms. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0291928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ennaji, O.; Baha, S.; Vergutz, L.; Allali, A.E. Gradient Boosting for Yield Prediction of Elite Maize Hybrid ZhengDan 958. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0315493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, D.K.; Yimam, S.; Arega, T.; Matheswaran, K.; Schmitter, P.M.V. Relatives, Neighbors, or Friends: Information Exchanges among Irrigators on New on-Farm Water Management Tools. Agricultural Systems 2022, 203, 103492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, M.; Rotar, I.; Vidican, R.; Mălinaș, A.; Ranta, O.; Lefter, N. Influence of the UAN Fertilizer Application on Quantitative and Qualitative Changes in Semi-Natural Grassland in Western Carpathians. Agronomy 2021, 11, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, G.M. Generalized Polya’s Theorem on Connected Locally Compact Abelian Groups of Dimension 1 2021.

- Zhang, Q.; Huang, W.; Wang, Q.; Wu, J.; Li, J. Detection of Pears with Moldy Core Using Online Full-Transmittance Spectroscopy Combined with Supervised Classifier Comparison and Variable Optimization. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, 200, 107231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Bachofen, C.; Wittwer, R.; Silva Duarte, G.; Sun, Q.; Klaus, V.H.; Buchmann, N. Using PhenoCams to Track Crop Phenology and Explain the Effects of Different Cropping Systems on Yield. Agricultural Systems 2022, 195, 103306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Kong, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Q.; Li, J.; Li, G.; Yuan, J. Using Tree-Based Machine Learning Models to Predict Diverse Compost Maturity via One-Hot Encoding: Model Deployment, Experimental Validation, and Practical Application. Waste Management 2025, 205, 114981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekonnen, D.K.; Yimam, S.; Arega, T.; Matheswaran, K.; Schmitter, P.M.V. Relatives, Neighbors, or Friends: Information Exchanges among Irrigators on New on-Farm Water Management Tools. Agricultural Systems 2022, 203, 103492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K, D.; Devi, O.R.; Ansari, M.S.A.; Reddy, B.P.; T, M.H.; El-Ebiary, Y.A.B.; Rengarajan, M. Optimizing Crop Yield Prediction in Precision Agriculture with Hyperspectral Imaging-Unmixing and Deep Learning. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications (IJACSA) 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rossum, G.; Drake, F.L. Python 3 Reference Manual; CreateSpace: Scotts Valley, CA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4414-1269-0. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. scipy 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numpy: Fundamental Package for Array Computing in Python.

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, F.V.; Martins, G.D.; Vieira, B.S.; de Assis, G.A.; Orlando, V.S.W. Multispectral Images for Monitoring the Physiological Parameters of Coffee Plants under Different Treatments against Nematodes. Precision Agric 2022, 23, 2312–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Huete, A.R.; Didan, K.; Miura, T. Development of a Two-Band Enhanced Vegetation Index without a Blue Band. Remote Sensing of Environment 2008, 112, 3833–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Lombi, E.; Zhao, F.-J.; Kopittke, P.M. Nanotechnology: A New Opportunity in Plant Sciences. Trends in Plant Science 2016, 21, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.; Schwarze, J.; Sherwood, O.L.; Jnaid, Y.; McCabe, P.F.; Kacprzyk, J. Stressed to Death: The Role of Transcription Factors in Plant Programmed Cell Death Induced by Abiotic and Biotic Stimuli. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciężkowski, W.; Szporak-Wasilewska, S.; Kleniewska, M.; Jóźwiak, J.; Gnatowski, T.; Dąbrowski, P.; Góraj, M.; Szatyłowicz, J.; Ignar, S.; Chormański, J. Remotely Sensed Land Surface Temperature-Based Water Stress Index for Wetland Habitats. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Veeranampalayam-Sivakumar, A.-N.; Bhatta, M.; Garst, N.D.; Stoll, H.; Stephen Baenziger, P.; Belamkar, V.; Howard, R.; Ge, Y.; Shi, Y. Principal Variable Selection to Explain Grain Yield Variation in Winter Wheat from Features Extracted from UAV Imagery. Plant Methods 2019, 15, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, D.D.; Eppes, M.-C.; Austin, J.C.; Bacon, A.R.; Billings, S.A.; Brecheisen, Z.; Ferguson, T.A.; Markewitz, D.; Pachon, J.; Schroeder, P.A.; et al. Soil Production and the Soil Geomorphology Legacy of Grove Karl Gilbert. Soil Science Society of America Journal 2020, 84, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, F.; Ren, X.; Tan, Z. Soil Carbon Sequestration Efficiency under Continuous Paddy Rice Cultivation and Excessive Nitrogen Fertilization in South China. Soil and Tillage Research 2021, 213, 105108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, F.; Gurarie, E.; Fagan, W.F.; Mainali, K.; Santiago, R.; Hervás, I.; Palacín, C.; Moreno, E.; Viñuela, J. Are Trellis Vineyards Avoided? Examining How Vineyard Types Affect the Distribution of Great Bustards. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2020, 289, 106734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traoré, A.; Falconnier, G.N.; Ba, A.; Sissoko, F.; Sultan, B.; Affholder, F. Modeling Sorghum-Cowpea Intercropping for a Site in the Savannah Zone of Mali: Strengths and Weaknesses of the Stics Model. Field Crops Research 2022, 285, 108581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Z.; Lu, X.; Li, S. Yield Prediction of Winter Wheat at Different Growth Stages Based on Machine Learning. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarr, A.B.; Sultan, B. Predicting Crop Yields in Senegal Using Machine Learning Methods. International Journal of Climatology 2023, 43, 1817–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, J.; Pagella, T.; Caulfield, M.E.; Fraval, S.; Teufel, N.; Wichern, J.; Kihoro, E.; Herrero, M.; Rosenstock, T.S.; van Wijk, M.T. Poverty Dynamics and the Determining Factors among East African Smallholder Farmers. Agricultural Systems 2023, 206, 103611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnolucci, M.; Avio, L.; Palla, M.; Sbrana, C.; Turrini, A.; Giovannetti, M. Health-Promoting Properties of Plant Products: The Role of Mycorrhizal Fungi and Associated Bacteria. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Otte, M.L.; Jiang, M.; Wang, M.; Yuan, Y.; Xue, Z. Does the Element Composition of Soils of Restored Wetlands Resemble Natural Wetlands? Geoderma 2019, 351, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatibi, S.M.H.; Ali, J. Harnessing the Power of Machine Learning for Crop Improvement and Sustainable Production. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yang, M.; Mohammadi, K.; Song, D.; Bi, J.; Wang, G. Machine Learning Crop Yield Models Based on Meteorological Features and Comparison with a Process-Based Model. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, P.; Soundrapandiyan, R. Yield Prediction for Crops by Gradient-Based Algorithms. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0291928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasanov, M.; Petrovskaia, A.; Nikitin, A.; Matveev, S.; Tregubova, P.; Pukalchik, M.; Oseledets, I. Sensitivity Analysis of Soil Parameters in Crop Model Supported with High-Throughput Computing. Computational Science—ICCS 2020 2020, 12143, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasanov, M.; Petrovskaia, A.; Nikitin, A.; Matveev, S.; Tregubova, P.; Pukalchik, M.; Oseledets, I. Sensitivity Analysis of Soil Parameters in Crop Model Supported with High-Throughput Computing. In Proceedings of the Computational Science—ICCS 2020; Krzhizhanovskaya, V.V., Závodszky, G., Lees, M.H., Dongarra, J.J., Sloot, P.M.A., Brissos, S., Teixeira, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 731–741. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, P.; Maity, P.P.; Kundu, M. Sensitivity Analysis of Cultivar Parameters to Simulate Wheat Crop Growth and Yield under Moisture and Temperature Stress Conditions. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Albalawneh, A.; Al-Zoubi, M.; Baroud, H. Variance-Based Sensitivity Analysis of Climate Variability Impact on Crop Yield Using Machine Learning: A Case Study in Jordan. Agricultural Water Management 2025, 313, 109409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunkiel, A.T.; Sui, D.; Wiktorski, T. Data-Driven Sensitivity Analysis of Complex Machine Learning Models: A Case Study of Directional Drilling. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2020, 195, 107630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahhosseini, M.; Hu, G.; Huber, I.; Archontoulis, S.V. Coupling Machine Learning and Crop Modeling Improves Crop Yield Prediction in the US Corn Belt. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aeberli, A.; Phinn, S.; Johansen, K.; Robson, A.; Lamb, D.W. Characterisation of Banana Plant Growth Using High-Spatiotemporal-Resolution Multispectral UAV Imagery. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, B.O.; Rey, J.C.; Perichi, G.; Lobo, D. Relationship of Microbial Activity with Soil Properties in Banana Plantations in Venezuela. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habyarimana, E.; Baloch, F.S. Machine Learning Models Based on Remote and Proximal Sensing as Potential Methods for In-Season Biomass Yields Prediction in Commercial Sorghum Fields. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0249136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahi, T.B.; Xu, C.-Y.; Neupane, A.; Guo, W.; Shahi, T.B.; Xu, C.-Y.; Neupane, A.; Guo, W. Machine Learning Methods for Precision Agriculture with UAV Imagery: A Review. era 2022, 30, 4277–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Yield | NDVI | Height (m) | Diameter (cm) | Nitrogen (%) | Porosity (%) | Slope | Yield (kg ha−1) | Boxes ha-1 |

| Baja | 0.70 | 2.5 | 16.0 | 20 | 30 | 3 | 35,988.5 | 1,983.9 |

| Alta | 0.85 | 4.0 | 25 | 55 | 45 | 1 | 50,571.7 | 2,787.9 |

| Yield | Modified variable | Change (%) | yield (kg ha−1) | Δ yield (kg ha−1) | Boxes ha-1 | Δ Boxes ha-1 |

| Low | NDVI | -10% | 35,637.30 | -351.19 | 1,964.57 | -19.36 |

| Low | NDVI | +10% | 36,967.59 | +979.09 | 2,037.90 | +53.97 |

| Low | Height | -10% | 35,988.49 | 0.00 | 1,983.93 | 0.00 |

| Low | Height | +10% | 36,980.12 | +991.63 | 2,038.60 | +54.67 |

| Low | Diameter | -10% | 35,988.49 | 0.00 | 1,983.93 | 0.00 |

| Low | Diameter | +10% | 37,347.32 | +1,358.83 | 2,058.84 | +74.91 |

| Low | Nitrogen | -10% | 35,988.49 | 0.00 | 1,983.93 | 0.00 |

| Low | Nitrogen | +10% | 35,988.49 | 0.00 | 1,983.93 | 0.00 |

| Low | Porosity | -10% | 35,988.49 | 0.00 | 1,983.93 | 0.00 |

| Low | Porosity | +10% | 36,920.1 | +268.67 | 1,998.74 | +14.81 |

| High | NDVI | -10% | 48,025.58 | 2,647.50 | -2,546.10 | -140.36 |

| High | NDVI | +10% | 50,571.68 | 2,787.85 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| High | Height | -10% | 50,571.68 | 2,787.85 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| High | Height | +10% | 50,571.68 | 2,787.85 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| High | Diameter | -10% | 50,571.68 | 2,787.85 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| High | Diameter | +10% | 50,571.68 | 2,787.85 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| High | Nitrogen | -10% | 49,256.46 | 2,715.35 | -1,315.2 | -72.50 |

| High | Nitrogen | +10% | 50,571.68 | 2,787.85 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| High | Porosity | -10% | 50,135.07 | 2,763.79 | -436.61 | -24.07 |

| High | Porosity | +10% | 50,571.68 | 2,787.85 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).