1. Introduction

Forensic investigation of explosive incidents is critical for reconstructing events, identifying explosive formulations, and supporting judicial processes. Among the most widely encountered explosives are ammonium nitrate fuel oil (ANFO) and nitrate-based compounds, which are favored because of their accessibility, low cost, and high detonation efficiency [

1,

2]. Following detonation, residues from these materials disperse onto diverse substrates, including metallic fragments, soils, and concrete. Oversized and irregular debris present additional challenges owing to uneven residue distribution and contamination gradients [

3].

Conventional extraction techniques, such as swabbing and solvent extraction, are widely used in forensic casework but are often insufficient for large-scale or heterogeneous exhibits, yielding low recovery rates and reduced sensitivity [

4]. To overcome these limitations, novel approaches, including spatially resolved subsampling, syringe filtering, and gel-based sampling methods, have been proposed [

5]. Instrumental methods remain central to residue characterization: gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) is the gold standard for organic explosive detection, whereas ion chromatography and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) are widely applied for inorganic residues [

6,

7]. However, the success of these methods depends heavily on the effectiveness of sampling and extraction workflows.

This study aimed to evaluate integrated forensic strategies—combining sequential swabbing, solvent extraction, syringe filtering, and subsampling—applied to oversized debris from ANFO–nitrate detonations. By coupling these workflows with GC–MS, TLC, and FTIR, this study demonstrates a robust protocol for improving explosive residue recovery and strengthening forensic interpretation in complex post-blast scenarios.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Evidence Collection from the Crime Scene

The exhibits were collected from the crime scene where the accused person illegally stored explosive substances in a warehouse of his open property, and the same was exploded due to triggering. The blast damaged the main gate, compound wall of the warehouse and the blasting effect and it’s fragments damaged glasses and Roofs of the nearby houses. Exhibits of small scale to oversized were collected from the crime scene, such as metallic spades, metallic pots with a height of 12 in., defamed metallic pieces with a length of 29 in., metallic nails, Polythene, Nylon sheets, metallic wires, broken plastic sheets, plastic pipes, and multiple small-size fragments, as shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. Soil from the point of explosion and control soil were also collected for examination.

2.2. Exhibits Preparation

The Laboratory received oversized exhibits in four parcels and two envelopes for soil samples. Diethyl Ether was obtained from Finar, Acetone (AR) was obtained from Advent Chembio Pvt. Ltd, Sodium Hydroxide, and Pyridine was obtained from SRL. Demineralized (DM) water procured from Labogen Fine Chem Industry, Ludhiana was used for Water and Alkali extraction. Whatman-42 filter paper was used for filtration. Allpure Nylon Syringe filter (pore size 0.22 μm) was procured from Membrane Solutions and used for the filtration of Ether and Acetone extracts. [

10,

11]

2.3. Extracts Collection and Analysis

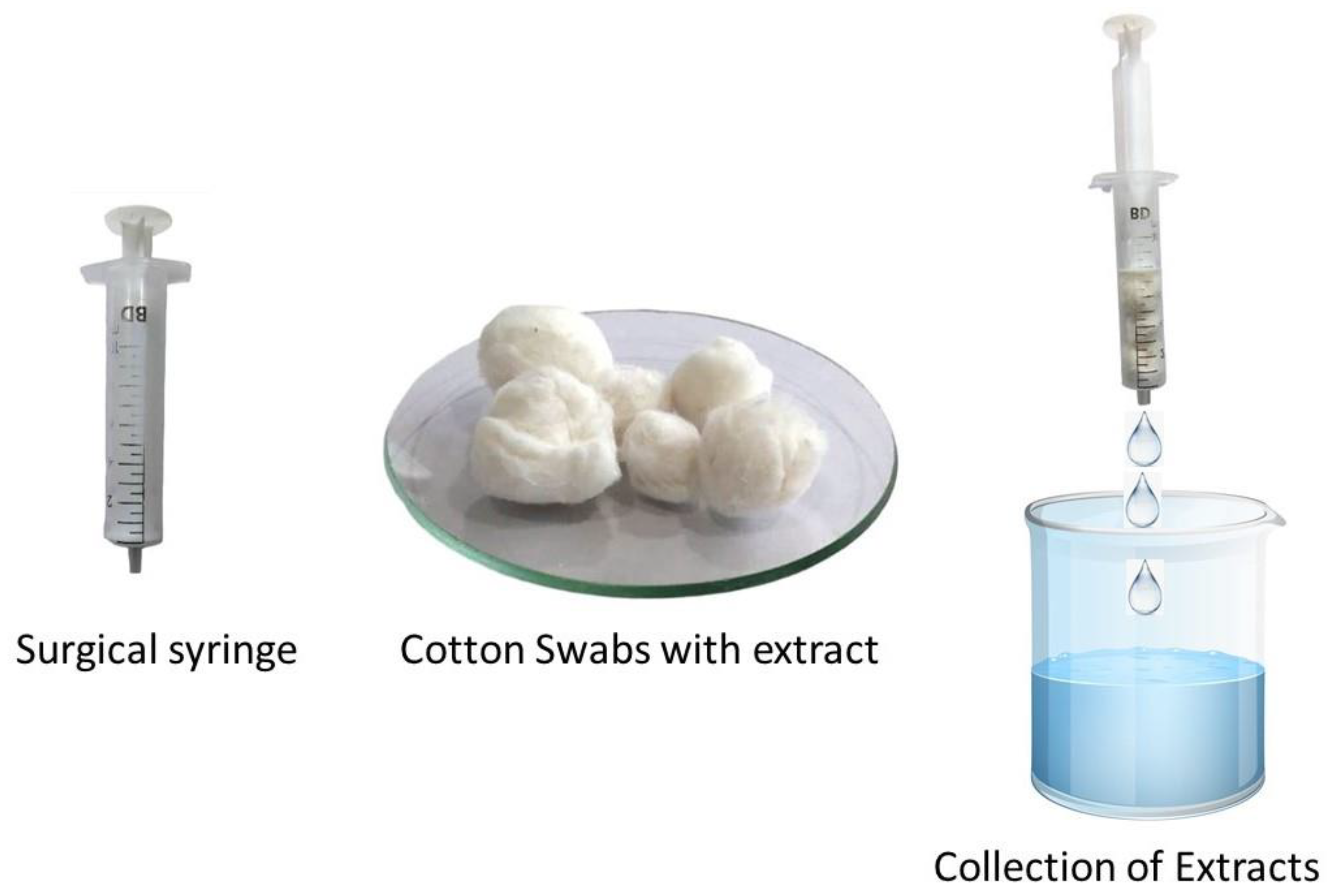

All the small exhibits and their fragments were properly extracted using Ether, Acetone, Water, Sodium Hydroxide and Pyridine to identify both In-Organic and Organic Explosive traces. The extraction was collected from the oversized exhibits using the swabbing method, as shown in

Figure 7. A Surgical syringe of 10 ml capacity and Kapas Absorbent cotton wool I.P. manufactured by Aster Corporation were used for the collection of extracts by the swabbing method. Complete swabbing was performed for the collection of Ether, Acetone, Water, Sodium Hydroxide and Pyridine extracts sequentially, as per the procedure [

8,

9].

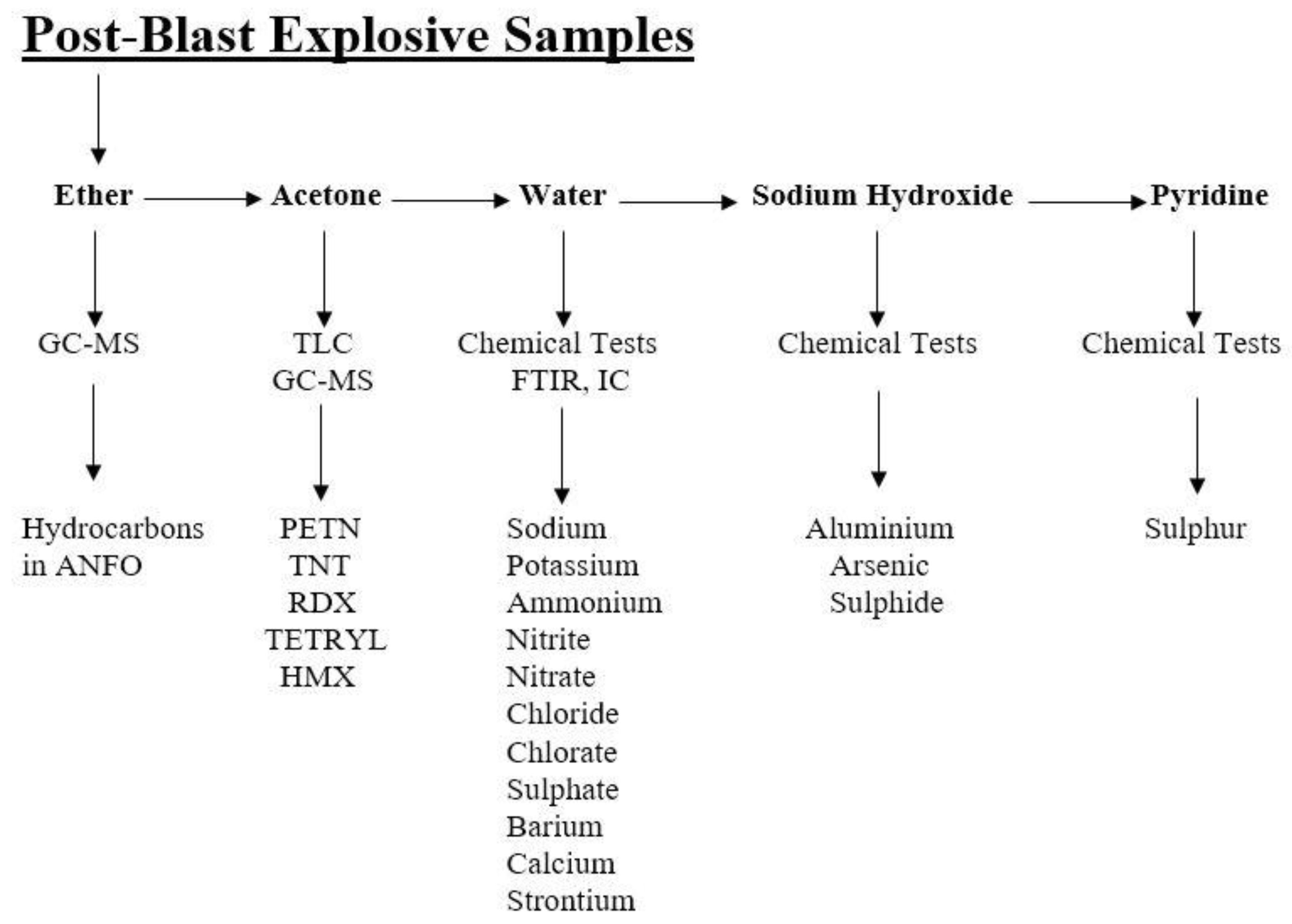

A schematic diagram of the examination of all extracts is shown in

Figure 8. In the Post-Blast phase, the collected exhibits will be heterogeneous, and the identification of the explosive ingredients will be challenging because of their uneven deposition. Therefore, the filter papers, syringe filters, cotton used for swabs, funnels and beakers used for the extraction of Ether extract from a particular exhibit should also be used for the extraction of Acetone, water, Sodium Hydroxide and Pyridine extracts. The extracts collected from the small and oversized samples were filtered using a syringe filter to remove solid impurities. The filtrate was collected in a 100 ml beaker and concentrated upto 2-5 ml by evaporation at room temperature. The Ether filtrates were analyzed using GC-MS for Diesel oil (hydrocarbons) to identify Ammonium Nitrate Fuel Oil (ANFO). Acetone filtrates were analyzed using TLC and GC-MS to identify Organic High Explosives. Water and Sodium Hydroxide Extracts were analyzed by chemical examination, FTIR, and IC for In-Organic Explosive ingredients. Elemental Sulphur will be identified through Pyridine extract.[

8,

9,

10,

11]

2.4. Thin Layer Chromatography

Silica gel 60G F254 Plates with a thickness of 200 micrometer and size of 20 x 20 cm were used for Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) analysis. Chloroform, Acetone, Toluene and Cyclo hexane used for the test.[

8,

9,

10,

11]

Pre-coated TLC plates were activated by placing them in an air oven at 110°C for 30 minutes. One hundred milliliters of solvent [chloroform : acetone (1:1) and toluene : cyclohexane (7:3)] was taken in two different developing chambers (for 20 × 20 cm TLC plates), covered with a lid, and allowed to saturate for at least 30 min. The concentrated acetone extract of each sample was spotted on a pre-coated TLC plate along with reference standards of high explosives, leaving 2 cm from one edge at the bottom of the TLC plate and maintaining a minimum distance of 1.5 cm between two spots. The TLC plate was placed vertically in the developing chamber and allowed to develop until the solvent front rose to 10 cm from the spots by capillary action. After completion, the plate was removed and left at room temperature for the eluent to evaporate.[

8,

9,

10,

11]

The TLC plate was developed by spraying with 5% diphenylamine (DPA) in 95% ethanol, and the colour produced was noted. The plate was then placed under UV light (254 nm) to observe fluorescence and subsequently sprayed with concentrated sulphuric acid, and the resulting colours were recorded. The colours were compared with the Rf values for identification.[

8,

9,

10,

11]

2.5. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

The Ether, Acetone and dried water extracts were examined using a Thermo Fisher Scientific Nicolet iS20 FTIR spectrometer instrument, which equipped with an IR source, an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) accessory, a DTGS detector and KBr beam splitter from Thermo Fisher Scientific. The instrument was operated at resolution of 4.000 between wavenumber 4000 cm-1 to 400 cm-1. The analysis was performed by scanning the background and sample using the Thermo Scientific OMNIC software. The sample was scanned 64 times to obtain a characteristic spectrum. The spectrum was searched using correlation search type in the libraries of the instrument to identify the sample.[

8,

9,

10,

11]

2.6. Challenges in the Analysis of Oversized Exhibits

Extraction from the exhibits of smaller sizes and their debris is possible by rinsing the exhibit with a minimum quantity of solvent in a beaker. In this method, the ingredients of the unexploded and exploded explosives can be easily collected from the exhibits by dissolution. However, in the case of oversized exhibits, the only possible way to collect the extract is by the swabbing method. Many factors, such as, the quality of the cotton, human error, spillage, and the collection of extract from the swab, will affect this method during the collection of the extracts. Care should be taken in the swabbing method to minimize these errors.

3. Observations

3.1. TLC and GC-MS Examinations

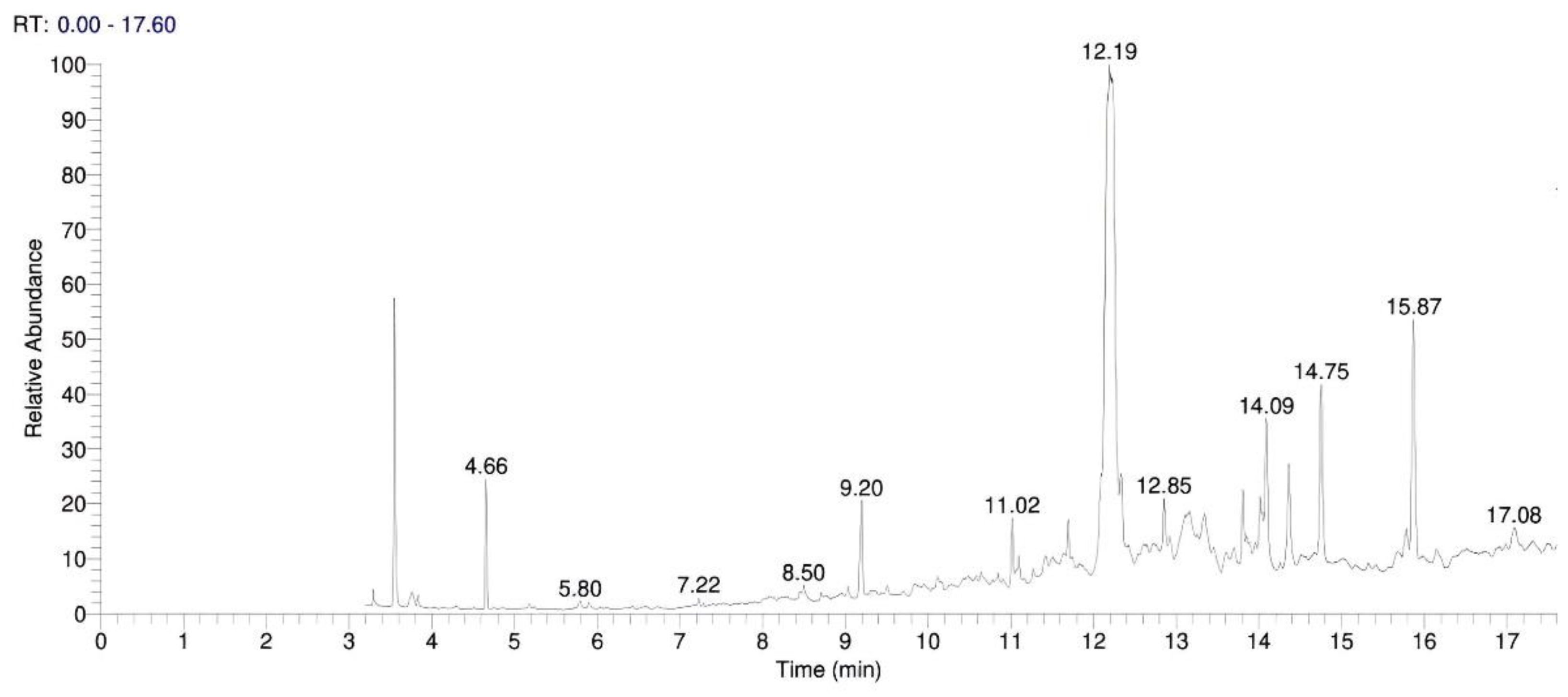

High-boiling fractions of petroleum hydrocarbons identified in the GC-MS analysis of the Ether extracts of the exhibit are shown in the

Figure 1. The compound name was identified by the GC-MS library as Hexadecane at the RT 14.02 having SI value of 792 and RSI value is 929. The GC-MS spectrum has a peak area of 136911064.09 and peak height of 37343910.88, as shown in

Figure 9 of the Total Ion Chromatogram (TIC).

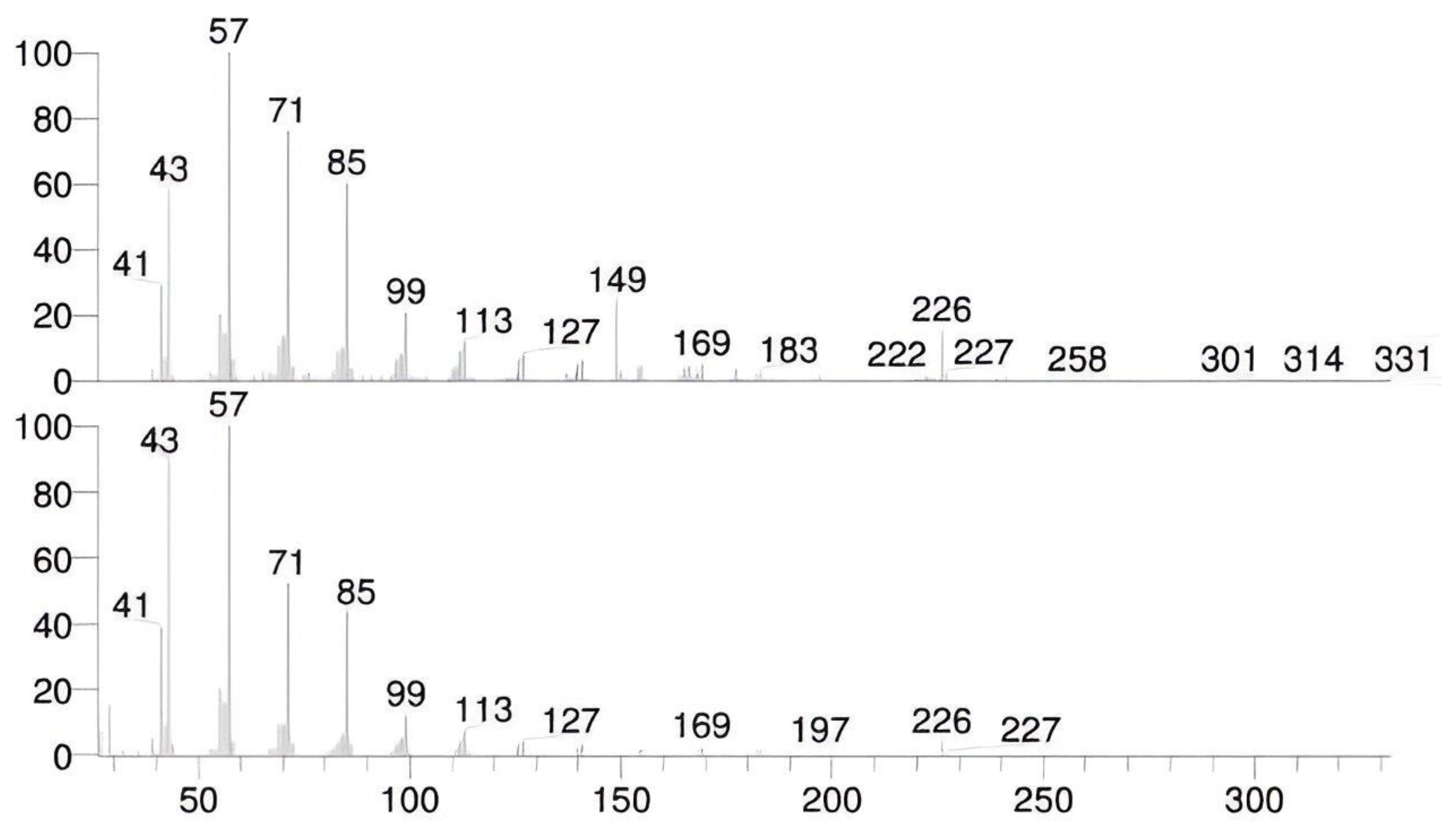

The mass spectra of the forensic case sample obtained by analysis using the GC-MS method, along with the reference library of mass spectra, are shown in

Figure 10. The x axis presents abundance and y axis presents m/z values.

No High Explosives were identified through Chemical Examination, TLC and GC-MS of the Acetone Extract.

3.2. Chemical Examinations

The Low Explosives identified in the Water, Alkali and Pyridine extracts of the smaller-sized and oversized exhibits are listed

Table 1. Except for the control soil, all the exhibits yielded positive results for low explosives.

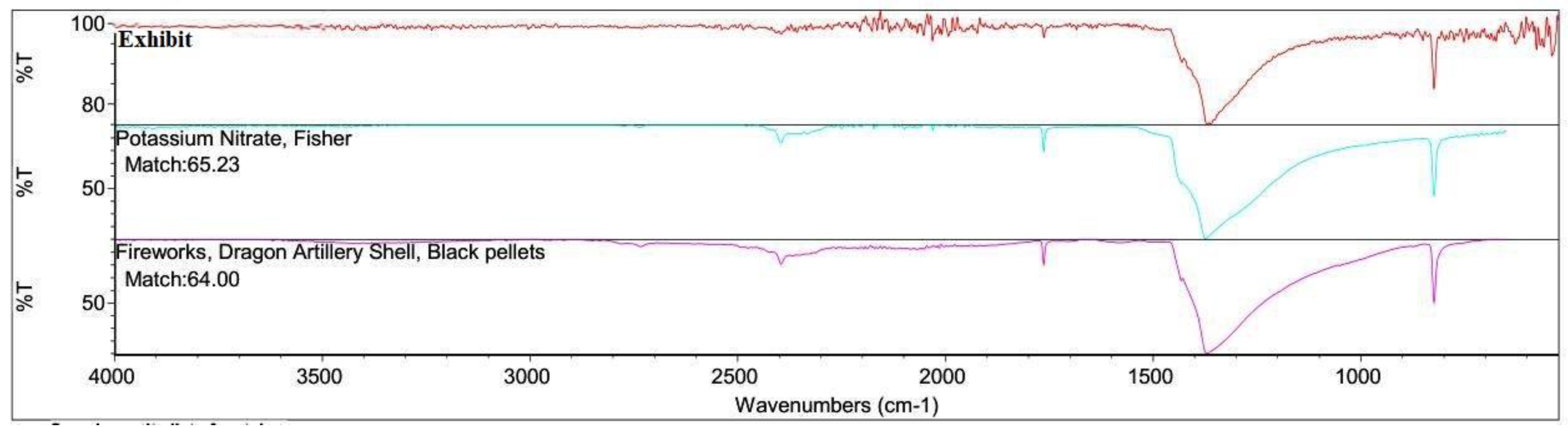

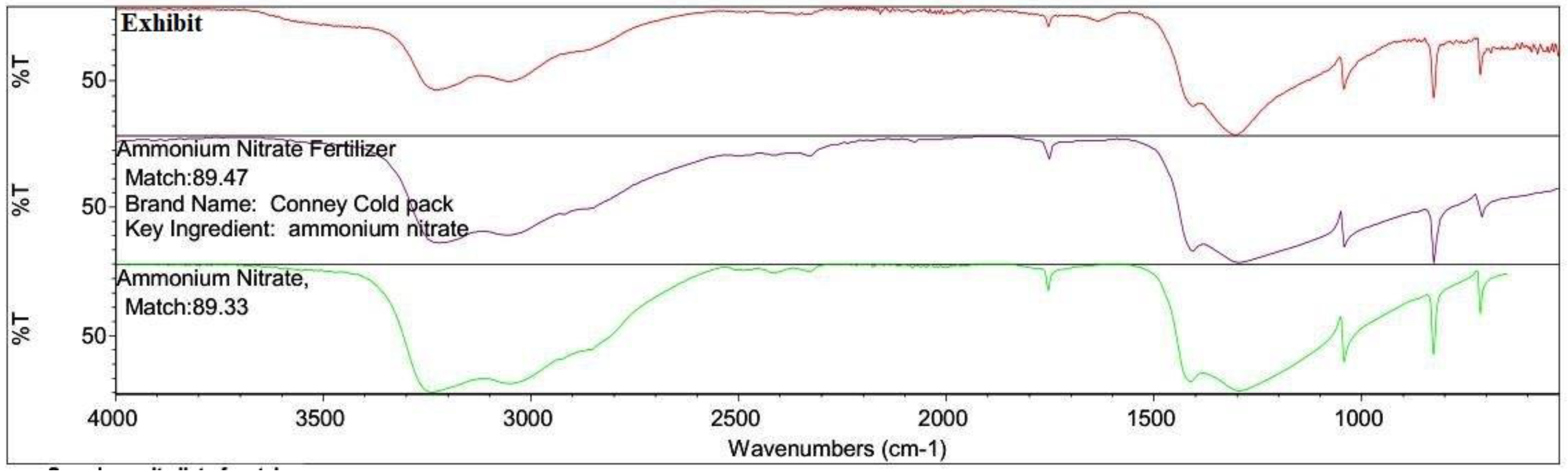

3.3. FTIR Analysis

High Explosives were not identified in the FTIR analysis of the Acetone Extract. However, Potassium Nitrate and Ammonium Nitrate (Low Explosives) were identified in the Water Extract. The FTIR spectra are shown in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12.

The presence of high-boiling fractions of petroleum hydrocarbons and Ammonium Nitrate confirms the presence of Ammonium Nitrate Fuel Oil (ANFO) in the Oversized Exhibits.

4. Results and Discussions

The forensic investigation of oversized and fragmented exhibits from the mixed ANFO–nitrate detonation provided consistent evidence of explosive residues across several analytical platforms.

4.1. Organic Residue Detection (GC–MS and TLC)

GC–MS analysis of ether extracts confirmed the presence of high-boiling petroleum hydrocarbons, with hexadecane identified at a retention time of 14.02 min. This finding is characteristic of diesel oil fractions, supporting the presence of fuel oil in the ANFO formulations. The spectral match with the NIST library provided high similarity indices, indicating robust identification [

1]. These results align with those of prior studies that demonstrated the reliability of GC–MS in detecting post-blast ANFO residues despite environmental degradation and substrate heterogeneity. Notably, no high explosives were detected in the Acetone extracts by TLC or GC–MS, suggesting that the device primarily relied on ANFO rather than high-explosive admixtures.

4.2. Inorganic Residue Detection (Chemical Tests and FTIR)

Chemical spot tests revealed positive results for nitrite, nitrate, ammonium, chloride, potassium, and sulphate ions across multiple exhibits, while chlorate, perchlorate, and metallic salts such as aluminium and magnesium were absent. These findings corroborate the presence of nitrate-based low explosives, consistent with ANFO residues. FTIR analysis further confirmed the ammonium nitrate and potassium nitrate signatures in the water extracts [

7], reinforcing the outcome of the chemical examinations. Such multi-method corroboration strengthens the evidentiary value by reducing false positives and analytical uncertainties, as emphasized in previous forensic residue studies.

4.3. Workflow Efficacy in Oversized Exhibits

The study demonstrated that sequential swabbing followed by solvent extraction and syringe filtration maximized residue recovery efficiency. The syringe filter method, in particular, improved extract clarity and reduced interference in GC–MS runs [

4]. These findings agree with recent advances highlighting that adapted workflows—such as spatially resolved subsampling and filtration—enhance residue detection from heterogeneous matrices.

4.4. Forensic Interpretation

The combined detection of hydrocarbons and nitrate ions confirms the presence of

ANFO in the oversized exhibits, thereby directly linking the recovered fragments to the explosive formulation used for detonation. Importantly, the absence of high explosives suggests the deliberate use of bulk ANFO rather than a composite device [

3]. These results are consistent with the reported global trends in improvised explosive devices, where ANFO remains the dominant formulation owing to its accessibility and effectiveness.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of an integrated forensic protocol for investigating oversized and fragmented exhibits from mixed ANFO–nitrate detonations in a field setting. By combining sequential swabbing, solvent extraction, syringe filtration, and complementary analytical techniques (GC–MS, TLC, chemical spot tests, and FTIR), the reliable detection of both organic (fuel oil hydrocarbons) and inorganic (nitrate-based) residues was achieved.

The results highlight three key conclusions:

The residue recovery efficiency was maximized by adapting the workflows to oversized exhibits, with syringe filtration proving particularly valuable.

Analytical corroboration across GC–MS, TLC, chemical tests, and FTIR reinforced evidentiary strength and reduced uncertainty.

Forensic reconstruction confirmed the exclusive use of ANFO, providing insights into the nature of the explosive device and its deployment strategy.

These findings emphasize that forensic protocols must be tailored to the scale and heterogeneity of post-blast exhibits to ensure accurate residue recovery and it’s interpretation. The methodological advances described herein contribute to strengthening forensic investigations of large-scale detonation events and support judicial processes by providing scientifically validated evidences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K.; methodology, D.K.; validation, D.K.; formal analysis, D.K.; investigation, D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K.; writing—review and editing, D.K.; visualization, D.K.; and supervision, D.K. The author has read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The author declares that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper. Should any raw data files be needed in another format, they are available from the author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to the Director, Central Forensic Science Laboratory, Pune, for continuous support and for providing the necessary infrastructure for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

TLC Thin Layer Chromatography

GC-MS Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry

FTIR Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

IC Ion Chromatography

in. inches

TIC Total Ion Chromatogram

NIST National Institute of Standards and Technology

AR Analytical Reagent

DM De-Mineralized

ATR Attenuated Total Reflectance

ANFO Ammonium Nitrate Fuel Oil

PETN Penta Erythritol Tetra Nitrate

TNT Tri Nitro Toluene

RDX Research Department Explosive/ Royal Demolition Explosive

NG Nitro Glycerin

TETRYL Trinitrophenylmethylnitramine

HMX High Melting eXplosive - Octogen

DPA Di Phenyl Amine

UV Ultra Violet

DTGS Deuterated Tri Glycine Sulfate

IR Infra Red

NaOH Sodium Hydroxide

References

- Braga, J. W. B.; Logrado, L. P. L. Evaluation of interferents in sampling materials for analysis of post-explosion residues (explosive emulsion/ANFO) using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). J. Forensic Sci. 2024, 70(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- De Vooght-Johnson, R. Contamination concerns for GC–MS analysis of explosive residues. Anal. Sci. 2024. Wiley Analytical Science. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Brown, K. Post-blast explosive residue: A review of formation and dispersion theories and experimental research. RSC Adv. 2014, 4(41), 12345–12360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doe, A.; Lee, P. Sampling of explosive residues: The use of a gelatine-based medium for the recovery of ammonium nitrate. Forensic Sci. Int. 2020, 310, 110234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.; White, S. Recent advances in ambient mass spectrometry of trace explosives. J. Mass Spectrom. 2018, 53(9), 873–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T. The application of mass spectrometry to explosive casework: Opportunities and challenges. In Applications of Mass Spectrometry for the Provision of Forensic Intelligence; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2017; pp. 201–223. [Google Scholar]

- Yinon, J. Detection of explosives by Fourier transform infrared spectrometry. J. Forensic Sci. 1995, 40(5), 865–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D. Explosive device reconstruction through chemical and trace evidence analysis: A homicide case investigation. Preprint (Version 1), Research Square, 17 August 2025. [CrossRef]

- Central Forensic Science Laboratory Pune. Working Procedure Manual; Doc. No.: CFSL/PUNE/WPM/EXPL/11, Issue No. 01; Directorate of Forensic Science Services, Ministry of Home Affairs: Pune, India, 2022.

- Kumar, D.; Prajakta, U. K. Optimizing forensic detection of explosive substances: Extended column analysis of TNT. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Prajakta, U. K. Thermal decomposition approach for PETN detection in improvised explosive devices. Int. J. Innov. Res. Technol. 2025, 11(12). Braga, J.W.B.; Logrado, L.P.L. Evaluation of interferents in sampling materials for analysis of post-explosion residues (explosive emulsion/ANFO) using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). J. Forensic Sci. 2024, 70, 1–9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).