Introduction

Anticipation is often described as a high-level cognitive function, conscious, deliberative, and dependent on brain-based representations. But over the past two decades, research has revealed anticipatory capacities in systems far removed from the nervous system: single-celled organisms, immune systems, gene regulatory networks, and metabolic pathways. These findings challenge the assumption that anticipation requires consciousness or even a nervous system. Instead, they suggest that anticipation is a general feature of life.

This paper develops the thesis that anticipation depends on memory: in all known cases of anticipatory behavior, the system draws on stored information to guide current or future action. This memory is not necessarily symbolic or explicitly encoded. While DNA provides a symbolic medium, its expression depends on nonsymbolic mechanisms, and organisms also carry subsymbolic traces — protein conformations, metabolite concentrations, epigenetic marks — that directly bias system dynamics. In bacteria, e.g. DNA functions not only as an evolutionary memory but as a resource for everyday activity. Subsymbolic memory may take the form of molecular structures, gene expression patterns, or epigenetic states—physical organizations that embody the results of past encounters with the environment.

Together, symbolic and subsymbolic forms of memory are indispensable to life, constituting the basis upon which organisms shape their activity and anticipate the future.

The guiding idea is drawn from Robert Rosen’s theory of anticipatory systems: a system is anticipatory if it contains a model of itself and its environment and uses this model to inform its behavior (Rosen 1985; 1991). But if we follow this definition carefully, it leads to an important insight: in biological systems, the model is the memory. The system’s organization reflects a history of interactions that now guide its actions. This moves us away from a representationalism, in which models are symbolic descriptions separate from the system, and toward an embodied view, in which models are physically instantiated within the system as constraints on its dynamics.

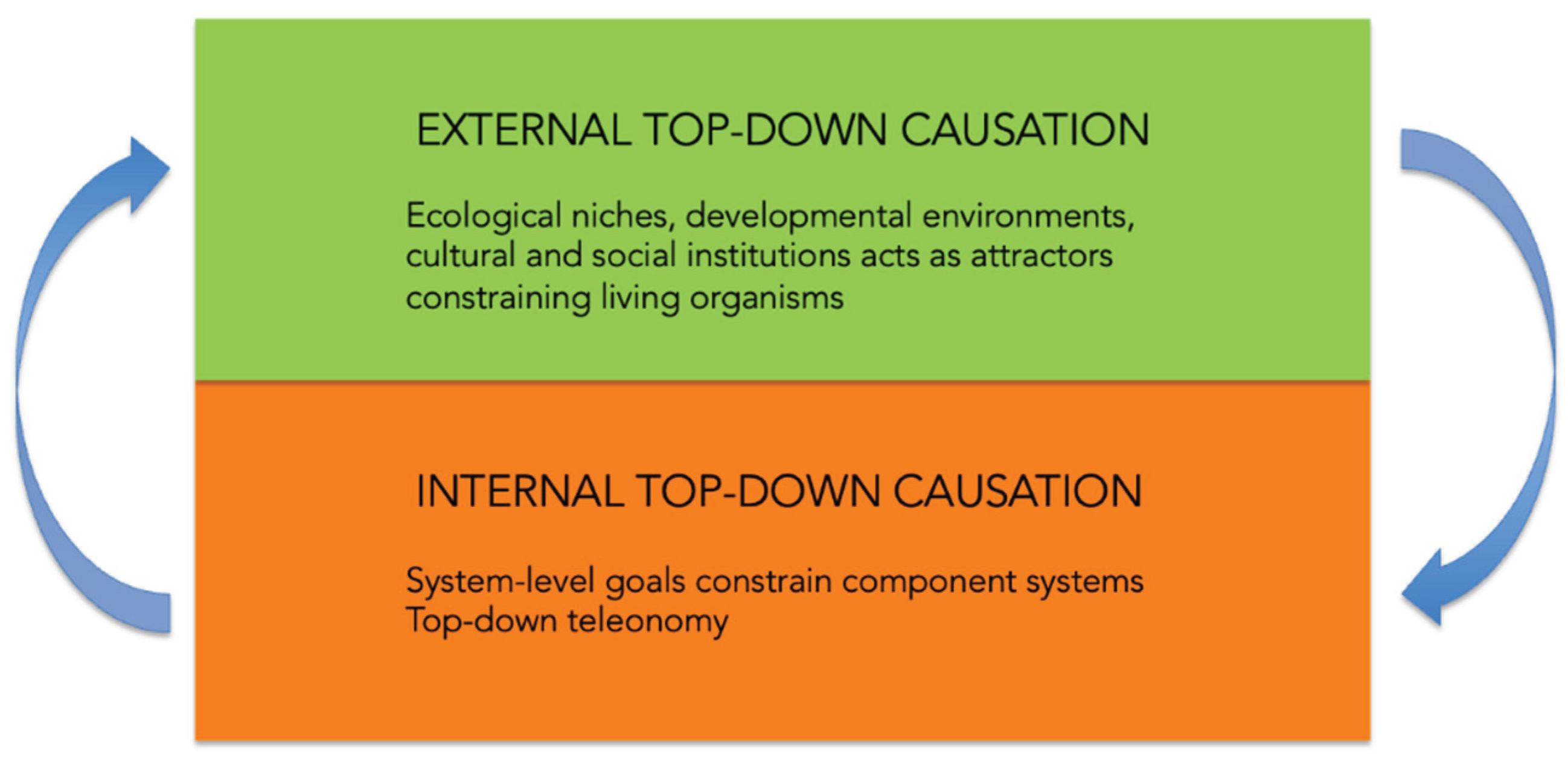

We begin by exploring the concept of memory in living systems—not just cognitive memory but structural and functional traces of experience. From there, we examine how these memories are used to generate predictions and guide behavior, leading to a generalized account of anticipation as a function of memory. We then consider a series of biological examples—ranging from bacteria to immune cells to circadian oscillators—that illustrate this relationship. Finally, we return to the concept of teleonomy, or end-directedness in biology, and argue that anticipatory behavior provides a concrete, mechanistic account of how purpose-like behavior arises from natural processes. Top-down causation refers to the influence of system-level goals, constraints, or models on the dynamics of the parts (Deacon, 2012; Moreno & Mossio, 2015). The thesis developed here is that organisms exercise top-down control by using memory to anticipate future states, thereby activating behaviors appropriate to those anticipated conditions.

While Rosen treated anticipation as a categorical property of life, contemporary perspectives extend his insight along evolutionary and developmental continua. Anticipatory capacities appear in degrees, scaling from molecular and cellular forms of memory to sophisticated cognitive models in humans (Friston, 2010; Levin, 2019).

Memory

The concept of memory is typically associated with conscious recollection in neural systems, but in all biological systems memory takes diverse forms. A scar on the skin remembers an injury; the adaptive immune system remembers a virus; a bacterial cell remembers exposure to a stressor. In each case, the organism stores some trace of a past event, and this trace influences its future behavior.

Memory is not unique to living systems. As Michael Leyton (1992; 2006) emphasized, even the shape of a physical object is a record of its past: the dent in a metal plate remembers an impact, the folds of a mountain remember geological pressures, the twisted form of a tree remembers prevailing winds. These are instances of mechanical memory, in which structure embodies the history of prior forces. Chemistry provides an additional level of memory: many chemical systems are path-dependent, leaving behind stable products or conformational states that bias future reactions (Nicolis and Prigogine, 1977; Hoffmann, 2019).

But in living systems, these traces are not just passive records — they are used. The key distinction is that living systems use memory functionally, to modulate behavior in light of predicted conditions.

This brings us to the idea that biological memory is functional memory: it informs present activity based on past conditions. In other words, biological memory is anticipatory. The anticipatory power of these traces derives from the recurrence and regularity of environmental conditions. If the same challenge is likely to recur — a viral infection, a thermal shock, a nutritional change — then storing a memory of that event confers survival value. As already explained, memories are not limited to symbolic representations of past states — such as DNA, the “chemical languages” of bacteria in quorum sensing, or the animal and human languages that underlie ecological and socio-cultural behavior. They are physical structures such as conformations of proteins, concentrations of molecules, epigenetic markers — that bias the dynamics of the system. They shape what the system is likely to do in a given context. In this sense, memory is not separate from function; it is the constraint on function. Genetic sequences preserve encounters with the environment, as in the incorporation of viral DNA into bacterial CRISPR loci (Marraffini, 2015). Epigenetic modifications and bioelectric fields similarly retain past states in ways that prepare cells for future challenges (Levin, 2019).

Table 1.

Types of memory in inanimate and biological systems.

Table 1.

Types of memory in inanimate and biological systems.

| Memory type |

Examples |

Mechanism |

Role in anticipation / teleonomy |

Mechanical/

Structural |

Dent in metal, folds in mountains, bent tree (Leyton, 1992; 2006) |

Shape retains traces of past forces |

Passive record of history; provides substrate for future constraints |

| Chemical |

Autocatalytic sets (Kauffman, 1993), prion conformations |

Path dependence, conformational stability, hysteresis |

Prior reactions bias future pathways; primitive anticipatory capacity |

| Genetic |

DNA sequences, CRISPR loci (Marraffini, 2015) |

Encoded sequence changes from past encounters |

Records environmental interactions; guides future adaptive responses |

| Epigenetic |

Chromatin modifications, DNA methylation (Guan et al., 2012) |

Stable changes in gene regulation |

“Primed” states enable faster or stronger future responses |

| Bioelectric |

Regenerative pattern memory (Levin, 2019) |

Stable voltage gradients across tissues |

Stores anatomical information guiding regeneration and morphogenesis |

| Neural |

Synaptic plasticity, forward models (Miall and Wolpert, 1996; Wolpert et al., 1998) |

Connectivity changes, dynamic internal simulations |

Enables simulation of actions and flexible prediction of outcomes |

Ecological,

Socio-cultural |

(Ulanowicz, 2009; Deacon, 2012; Krakauer et al., 2020; Pezzulo, 2008) |

Distributed concurrent information processing networks |

Enlarges “cognitive cone” of individual neural units |

The above table shows a continuum from passive physical traces to active biological models, emphasizing that anticipation arises whenever memory is harnessed functionally.

From this perspective, life builds on the universal principle that matter retains traces of its past but transforms it into a mechanism for anticipation. What distinguishes living memory is that these traces are used as active constraints that bias present behavior toward possible futures. In Rosen’s (1985, 1991) terms, the organism contains a “model of itself and its environment.” For a bacterium, this model is a physical organization: methylated receptors comparing past and present concentrations, genomic records of prior infections, or metabolic states that encode environmental regularities. In this way, anticipation is not a mysterious capacity but a natural consequence of how memory becomes organized in living systems into teleonomic functions: the retention of the past shapes present activity in the service of future viability.

A Note on Memory and Non-Ergodicity

In statistical physics, an ergodic system is one in which the system’s trajectory explores all accessible states, and time averages converge to ensemble averages (van Kampen, 1992). Ergodic systems are memoryless: given sufficient time, they lose all dependence on initial conditions. Living systems, however, are profoundly non-ergodic (Kauffman, 2019). Their histories matter: paths taken constrain future possibilities.

Non-ergodicity is visible even in chemistry. Autocatalytic reactions, for example, reinforce their own pathways, closing off alternatives and embedding a history of prior reactions into the structure of the system (Kauffman, 1993). Such path dependence constitutes a fundamental form of memory, since the present state reflects accumulated transformations rather than a statistical equilibrium. This memory provides the substrate for anticipation: without traces of the past, no projection into the future is possible.

Memory and Anticipation

Examples of Anticipatory Memory in Living Organisms

Anticipation in living systems should not be understood as a mystic foresight. Rather, it emerges spontaneously from the way organisms retain traces of past interactions and use them to bias present and future behavior. In Rosen’s language, the “model” a system carries of itself and its environment, is a physical organization whose dynamics encode regularities. The following examples illustrate how even the simplest organisms embody such anticipatory models and how those mechanisms emerge from chemistry and physics.

Autocatalytic Sets: Memory in Chemistry

Autocatalytic networks, first described by Kauffman (1993), are chemical systems in which reactions mutually catalyze one another, forming a circular set. Once established, such networks are historically contingent: their particular topology persists, biasing future reactions. This persistence functions as structural memory, enabling the network to “anticipate” continued availability of reactants. The closure of the network constrains the kinetics of individual reactions, exemplifying a form of top-down causation in which system-level organization governs local dynamics.

CRISPR Systems in Bacteria

CRISPR-Cas systems provide adaptive immunity in prokaryotes. Bacteria store sequences from phage DNA in their genome and use them to recognize and destroy future invaders (Marraffini, 2015). Here the “model” is literally written into the genome: a record of past viral patterns enables anticipation of recurrence. This is teleonomic in the strict sense — the future goal of defense constrains present molecular activity.

Bacterial Chemotaxis

In Escherichia coli, movement toward favorable chemical environments depends on the methylation state of chemoreceptors. Methylation provides an integral feedback memory, allowing cells to compare current ligand concentrations with recent past values (Barkai and Leibler, 1997; Bray, 1995). This enables bacteria to bias their swimming not simply by immediate stimuli but by anticipated trends in concentration gradients. The organism-level goal of gradient climbing constrains the stochastic switching of flagellar motors, a clear instance of top-down causation.

Circadian Rhythms

Many organisms possess internal clocks that anticipate daily environmental changes. In cyanobacteria, circadian rhythms are maintained by a molecular oscillator based on phosphorylation cycles of the KaiC protein (Nakajima et al., 2005). These oscillators function without external input once entrained, predicting the timing of future events such as light availability. The oscillator does not merely respond to light; it anticipates it. The current state of the molecular oscillator is a memory of prior light-dark cycles (Johnson and Golden, 1999). This internal periodicity allows the organism to adjust its behavior proactively. The model is the oscillator itself — an internal, dynamically maintained structure that encodes past cycles and predicts future ones.

Yeast Stress Memory

When exposed to environmental stressors, yeast cells activate a stress response pathway that reconfigures gene expression and metabolic activity. Cells exposed to a mild, nonlethal stress become more resistant to subsequent, more severe stress. This phenomenon, known as stress priming, reflects a form of memory: the cells retain a modified internal state that allows them to survive future challenges. This memory persists over multiple generations, even in the absence of the original stressor (Zakrzewska et al., 2011). Here, the model is the internal configuration of gene expression and protein activity, which reflects past experience and alters future behavior. The system has changed its dynamics in a way that predicts recurrence of the same condition.

Slime Molds and Learning

Slime molds like Physarum polycephalum can learn and solve spatial problems, even though they have no nervous system. They can anticipate periodic events, remember prior stimuli, and adapt behavior accordingly (Boussard et al., 2021). Here, memory is embodied in network geometry, oscillatory dynamics, and cytoplasmic flows. These properties encode past environmental structure and guide behavior, effectively serving as a non-neural model.

Adaptive Immunity

The vertebrate immune system provides a paradigmatic case of anticipatory organization. Following exposure to a pathogen, specific immune cells are selected, expanded, and retained as memory cells (Murphy & Weaver, 2016). Upon re-exposure, these memory cells mount a faster and more effective response. The immune system learns from experience and alters its future response accordingly. The model is encoded in the population of memory cells, which biases the system toward anticipated pathogens. The model is is physical, distributed, and self-maintained.

Trained Innate Immunity

Even innate immune responses, long thought to lack memory, can exhibit lasting changes based on prior exposures. Certain stimuli induce epigenetic modifications that change the transcriptional response of innate immune cells, a phenomenon known as trained immunity (Netea et al., 2016). The result is an enhanced response to subsequent challenges. Again, the system’s organization has been altered by prior experience. The memory is encoded in chromatin states and transcriptional potential. The system behavior shows anticipation of further challenge.

Bioelectric Pattern Memory in Development

Multicellular organisms maintain bioelectric gradients that encode information about target morphologies. In planarians, for example, stable patterns of gap-junctional coupling and membrane voltage store information about head-tail polarity. When injured, tissues regenerate toward this stored pattern, sometimes correcting large perturbations (Levin, 2019). Bioelectric states thus function as a memory of form, guiding anticipatory developmental and regenerative processes. The macro-level goal of restoring a body plan constrains gene expression, proliferation, and migration at the cellular level.

Neural Systems Memory

The evolutionary appearance of nervous systems brought a qualitative transformation. Unlike immune memory or metabolic adaptation, which are largely specialized and domain-specific, nervous systems provide a general-purpose modeling architecture. This shift made possible new forms of anticipation: simulation, flexibility and coordination. Neural systems can simulate, i.e. generate “as-if” scenarios - forward models of what would happen under different actions (Miall and Wolpert, 1996). Instead of encoding only one type of environmental regularity, nervous systems can flexibly learn and update patterns across sensory, motor, and social domains. By integrating multiple streams of information, nervous systems allow anticipation to extend beyond single-cell responses into coordinated organismal behavior. In animals, the nervous system uses synaptic plasticity to build internal models of body and environment (Wolpert et al., 1998). Anticipation enables movements to be corrected before feedback arrives, effectively beating sensorimotor delays. Here the system-level goal (accurate reaching, stable locomotion) shapes the firing patterns of microcircuits, providing an explicit example of top-down causation rooted in memory and prediction.

From this perspective, the nervous system can be seen as an anticipatory subsystem within the larger anticipatory system of the organism. It centralizes and amplifies capacities that are already present in distributed biological mechanisms but organizes them into a coherent model space. This is why Rosen’s claim — that living systems embody models of themselves and their environments — finds its most direct expression in neural anticipatory architectures.

Above examples illustrate how memory and anticipation are linked across biological scales, and how they generate top-down causal dynamics. They are summarized it

Table 2.

From Memory to Anticipation to Goal-Directedness (Teleonomy)

Rosen showed that through functional entailment (in category theory), it is possible to give a scientifically legitimate account of final cause (Lennox, 2024). Unlike material, efficient, and formal causes, final cause has a reflexive character: the effect participates in entailing its own cause. Traditional science rejected final causes because they seemed to imply “future states acting on the present.” Rosen reframed this: in relational systems, final cause emerges from the organizational closure of entailments.

Final cause in Rosen’s sense means that the organization of the whole constrains the functions of the parts. This is what philosophers of biology describe as downward causation: the system-level goals or functions (e.g., “the heart is for pumping blood”) guide and constrain component processes. Rosen provided the formal system-theoretic machinery to make sense of such final causes without lapsing into metaphysical problems. Recently, Evolution “On Purpose” (Corning et al., 2023) naturalizes teleology into teleonomy, goal-directedness grounded in evolution and self-organization.

Rosen’s idea that an organism contains a “model of itself and its environment” means that its organization encodes information about past interactions in a way that is usable for shaping future behavior. In bacteria, the model is not an explicit representation but a genomic record, a receptor-modification system, or a metabolic configuration. These internal structures embody causal hypotheses about what will happen if the same conditions recur. In this sense, anticipation arises from memory-driven constraints on dynamics, yielding a naturalized teleology.

Endogenous and Exogenous Teleonomy

Rosen argued that the purposiveness of living systems, their teleology, arises endogenously from their internal organization. In his relational biology, organisms are closed to efficient causation: each process is entailed by others within the system, so that the whole constrains the dynamics of its parts (Rosen, 1991). This closure enables the organism to embody what Rosen described as a “model of itself and its environment” (Rosen, 1985). Anticipation, in this view, is not imposed from outside but is a constitutive property of living systems, and teleonomy is naturalized as an intrinsic outcome of their organization.

This emphasis on organizational closure focus on the autonomy of the endogenous dimension. Anticipatory models however arise in relation to external regularities: the “environment” component of Rosen’s formula points directly to the exogenous world of ecological constraints and evolutionary pressures. Memory traces within the organism are themselves records of past interactions with the environment, and the anticipatory power of these traces derives from the fact that external conditions tend to recur or exhibit regularity.

For this reason, anticipation is never purely endogenous. It is always relational, emerging from the interplay between endogenous closure and exogenous embedding. The immune system exemplifies this: once generated, memory repertoires constrain responses endogenously, but their content originates in exogenous encounters with pathogens. Similarly, circadian clocks are endogenous oscillators, but their adaptive function derives from synchrony with external day–night cycles.

Formalization of anticipation and final cause done by Rosen re-legitimizes internal top-down causation: the organization of an anticipatory system entails its own functions, such that system-level goals constrain the behavior of components. In relational terms, this is how living systems embody purposiveness without invoking metaphysical teleology (Louie, 2010). This argument applies primarily within the organismal system. At the same time, teleonomic accounts in evolutionary context (Corning et al., 2023) stress that external top-down causation also plays a critical role. Organisms exist in ecological, developmental, and cultural niches whose higher-level goal states act as attractors that constrain organismal dynamics. Thus, a full account of purposiveness in living systems requires integrating Rosen’s internal closure with external teleonomic constraints, showing how memory and anticipation operate across multiple scales of top-down causation.

In light of these considerations, Rosen’s framework can be usefully extended by distinguishing endogenous teleonomy, the purposiveness that arises from organizational closure, from exogenous teleonomy, the purposiveness imposed by ecological, evolutionary, and cultural contexts. Anticipation thus emerges not only from within but from the dialogue between system and world, making teleonomy an inherently relational property of living systems.

Figure 1.

Internal (endogenous) vs. external (exogenous) top-down causation.

Figure 1.

Internal (endogenous) vs. external (exogenous) top-down causation.

From Memory to Anticipation to Top-Down Causation

To sum up, a common pattern shows the connection: Memory, in structural, epigenetic, immunological, bioelectric, or synaptic form, preserves information about the past. Anticipation is systems use of this stored information to project into expected futures, goal-directed biasing present actions. Top-down causation emerges as system-level objectives (survival, homeostasis, morphology, accuracy) constrain component dynamics.

This perspective is aligned with the constraint-based causation framework developed in theoretical biology and philosophy (Deacon, 2012; Moreno Mossio, 2015). Higher-level goals do not exert unexplainable new forces but operate by constraining the range of micro-level trajectories. Anticipation supplies the mechanism by which these goals exert causal efficacy: memory-based models of the future bias present dynamics in ways aligned with system-level objectives.

This framing constitutes the triad of memory, anticipation, and top-down causation. Memory preserves past configurations, anticipation projects possible futures and top-down causation manifests when those projected futures constrain present dynamics. Teleonomy is thus the evolutionary expression of anticipatory organization. Systems embody models of anticipated futures, and those models act downward on both organismal parts and ecological contexts.

Teleonomy, Anticipation, and Top-Down Causation

Classical biology often treated purposiveness with suspicion, distinguishing teleology (metaphysical purpose) from teleonomy as goal-directedness grounded in natural mechanisms (Pittendrigh, 1958; Mayr, 1974). Recent accounts of evolution “on purpose” (Corning et al., 2023) revisit this distinction by linking teleonomy directly to downward causation in living systems. Goal states, whether in development, physiology, or behavior, act as attractors that constrain lower-level processes. Igamberdiev in (Corning et al., 2023) proposes that the final state retro-causally shapes earlier dynamics, providing an account of purposive behavior. Present article explains that “retro-causality”.

Where Rosen emphasized that life is intrinsically anticipatory (Rosen, 1985, 1991), and Friston formalized this principle via Bayesian generative models (Friston, 2010, 2013), “Evolution On Purpose” extends the argument to evolution itself. Organisms do not merely undergo selection; they actively shape their own evolutionary trajectories through teleonomic top-down causation, niche construction, and genome self-modification.

In this light, teleonomy provides the naturalized vocabulary for connecting individual anticipatory systems with the larger evolutionary process. Anticipation is not only an organizational principle within organisms but also a causal force in evolution, where memory (genetic, epigenetic, cultural) and projection (anticipation of futures) constrain the space of possibilities and bias outcomes.

Conclusion

Living systems are anticipatory. They do not merely react to present stimuli but act in light of anticipated future. Anticipation depends on different types of memory: chemical (autocatalytic closure, non-ergodicity); genetic/epigenetic (DNA, methylation); protein state memory (post-translational modifications, receptor methylation), network memory (bioelectric circuits, gene regulatory loops, immune repertoires), neural memory (synaptic plasticity, working/long-term memory) and cultural-symbolic (language, external artifacts). Through memory-based anticipation, organisms exhibit top-down causation: system-level goals constrain micro-level dynamics by activating adequate responses to anticipated states.

Presented perspective reframes life not merely as a reactive chemical system, but as an organized, memory-driven process oriented toward the future.

It highlights that what distinguishes life is not complexity alone, but the ability to use past experience to shape and coordinate internal dynamics in pursuit of future viability. This synthesis aligns with Rosen’s insight into anticipatory systems while integrating advances from origins-of-life research, systems biology, developmental biology, and neuroscience. By connecting the dots and highlighting the interplay of memory, anticipation, and top-down causation, we can better understand the organizational principles that make living systems distinctively autonomous, adaptive, and creative.

References

- Barkai, N.; Leibler, S. Robustness in simple biochemical networks. Nature 1997, 387, 913–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boussard, A.; Delescluse, J.; Pérez-Escudero, A.; Dussutour, A. Adaptive behaviour and learning in slime moulds: The role of oscillations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2021, 376, 20190757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, D. Protein molecules as computational elements in living cells. Nature 1995, 376, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Evolution “on purpose”: Teleonomy in living systems; Corning, P.A., Kauffman, S.A., Noble, D., Shapiro, J.A., Vane-Wright, R.I., Pross, A., Eds.; MIT Press, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, T. Incomplete nature: How mind emerged from matter; W. W. Norton, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Friston, K. The free-energy principle: A unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2010, 11, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Q.; Haroon, S.; Bravo, D.G.; Will, J.L.; Gasch, A.P. Cellular memory of acquired stress resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2012, 192, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, R. Roald Hoffmann on the philosophy, art, and science of chemistry; Oxford University Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C.H.; Golden, S.S. Circadian programs in cyanobacteria: Adaptiveness and mechanism. Annual Review of Microbiology 1999, 53, 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauffman, S.A. The origins of order: Self-organization and selection in evolution; Oxford University Press, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, S.A. A world beyond physics: The emergence and evolution of life; Oxford University Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Krakauer, D.C.; Bertschinger, N.; Olbrich, E.; Flack, J.C.; Ay, N. The information theory of individuality. Theory in Biosciences 2020, 139, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennox, J.B. Robert Rosen and relational system theory: An overview. In Anticipation Science; Springer, 2024; Vol. 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, M. The computational boundary of a “self”: Developmental bioelectricity drives multicellularity and scale-free cognition. Frontiers in Psychology 2019, 10, 2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, M. Technological Approach to Mind Everywhere: An Experimentally-Grounded Framework for Understanding Diverse Bodies and Minds. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 2022, 16, 768201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyton, M. Symmetry, causality, mind; MIT Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Leyton, M. Shape as Memory. A Geometric Theory of Architecture. Birkhäuser. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Louie, A.H. Robert Rosen’s anticipatory systems. Foresight 2010, 12, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marraffini, L.A. CRISPR-Cas immunity in prokaryotes. Nature 2015, 526, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miall, R.C.; Wolpert, D.M. Forward models for physiological motor control. Neural Networks 1996, 9, 1265–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, A.; Mossio, M. Biological autonomy: A philosophical and theoretical enquiry; Springer, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.; Weaver, C. Janeway’s immunobiology, 9th ed.; Garland Science, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima, M.; Imai, K.; Ito, H.; Nishiwaki, T.; Murayama, Y.; Iwasaki, H.; Oyama, T.; Kondo, T. Reconstitution of circadian oscillation of cyanobacterial KaiC phosphorylation in vitro. Science 2005, 308, 414–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netea, M.G.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Latz, E.; Mills, K.H.G.; Natoli, G.; Stunnenberg, H.G.; O’Neill, L.A.J.; Xavier, R.J. Trained immunity: A program of innate immune memory in health and disease. Science 2016, 352, aaf1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolis, G.; Prigogine, I. Self-organization in nonequilibrium systems: From dissipative structures to order through fluctuations; Wiley, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Pezzulo, G. Coordinating with the Future: The Anticipatory Nature of Representation. Minds and Machines 2008, 18, 179–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R. Anticipatory systems: Philosophical, mathematical, and methodological foundations; Pergamon, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, R. Life itself: A comprehensive inquiry into the nature, origin, and fabrication of life; Columbia University Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Y.; Shimizu, T.S.; Berg, H.C. Modeling the chemotactic response of Escherichia coli to time-varying stimuli. PNAS 2008, 105, 14855–14860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulanowicz, R.E. A third window: Natural life beyond Newton and Darwin; Templeton Foundation Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- van Kampen, N.G. Stochastic Processes in Physics and Chemistry, 2nd edition; Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert, D.M.; Miall, R.C.; Kawato, M. Internal models in the cerebellum. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 1998, 2, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakrzewska, A.; van Eikenhorst, G.; Burggraaff, J.E.C.; Vis, D.J.; Hoefsloot, H.; Delneri, D.; Oliver, S.G.; Brul, S.; Smits, G.J. Genome-wide analysis of yeast stress survival and tolerance acquisition to analyze the central trade-off between growth rate and cellular robustness. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2011, 22, 4435–4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).