Submitted:

08 September 2025

Posted:

10 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

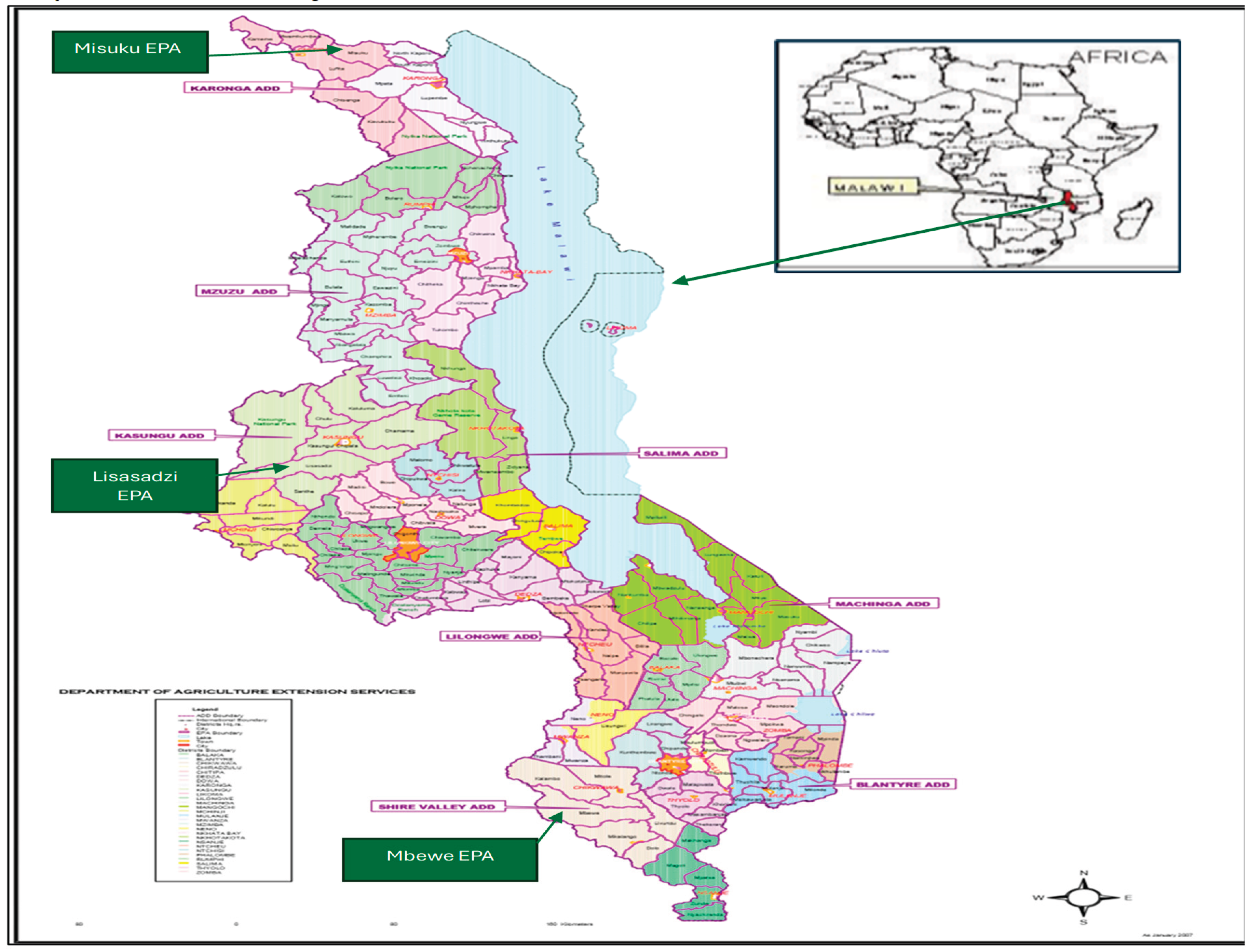

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection Methods

2.2.1. Key Informant Interviews

2.2.2. Focus Group Discussions with Small-Scale Farmers and EAS actors

2.2.3. Desk review

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Qualitative Analytical Techniques

3. Results

3.1. Aspirations of Various Categories of Farmers and EAS Actors on Agriculture and Farming Systems

3.1.1. Current Aspirations of Farmers on Agriculture

- Soil and land degradation; Farming land and soils have degraded for most farmers. Widely, soil infertility is one of the farming challenges among many farmers of all classes. Cases of soil erosion such as gullies and rills are common. This is due to decades of poor farming practices and other anthropogenic practices. For instance, Misuku Cooperative farmers indicated that they cut down trees every season to make a table for drying coffee, a practice that is contributing to soil erosion in the area.

- Climate change; Farmers widely reported facing challenges in farming due to climate change. The commonly mentioned challenges include dry spells, droughts and floods. Furthermore, the drought conditions were also reported to have increased incidences of pests and diseases for both crops and livestock. For example, fall army worm has been one of the serious pests attacking maize plants. The problems were severe in Chikwawa, going by the results of the FGDs. The district experiences floods and droughts often compared to other areas in which the study was conducted.

- Malnutrition: With high levels of malnutrition as stated (about 39% of under five children suffer chronic malnutrition), farmers are also being oriented to nutrition sensitive agriculture. This is the type of agriculture which embraces a need to produce many crops and livestock so that the households of the farmers consume nutritious and diversified foods, the Malawi’s six food groups (meat, staples, legumes, vegetables, fruits and fats and oils). Thus, farmers are advised to have their farming systems reflect these groups to achieve dietary diversity. Some of the approaches include agricultural diversity (crop and livestock) and having homestead/backyard gardens. Practice of such nutrition sensitive agriculture is hindered by cultural beliefs (i.e. culture or religion prohibiting consumptions), limited access to the seeds, inadequate availability of material and financial resources, lack of sensitization of all the key the food systems actors. Consequently, it is still a struggle for many farmers to design their farming systems based on nutrition.

- Market demands; The market is demanding specific crops and livestock. Maize, rice and some selected legumes (groundnuts, soya, beans and pigeon peas) are the major food crops. Tobacco, sugarcane, cotton, tea and coffee are the major cash crops.

- Gender participation; Women are being encouraged to participate in the farming business because they have been side-lined in major household decision making processes.

- Loss of biodiversity; Farming is increasingly orienting to the market, with production focusing on few high value enterprises. Most smallholders focus on combining maize, soya bean and groundnuts. Most medium farmers would also engage in tobacco in addition to the aforementioned. Large estate focus on one crops or livestock. For instance, Illovo estate only focuses on sugarcane. Upon government request, it produced maize in some years. Many farmers indicated to have lost maize local variety which their ancestors passed on from generation to generation. Likewise, other indigenous crops such as millet, Bambara nuts, Mucuna and local small livestock are being lost also. The farmers indicated that some of these local species were tolerant to tough conditions. Which is why some extension agents are promoting the cultivation of such indigenous species is challenged by the demands of the markets which often do not include them as high value crops. Farmers looking for income rarely focus on this.

- Food safety; With a focus on the market, farmers with capacity apply large quantities of agrochemicals. The aim is to produce more and win by economies of scale. As found in the study, production of more foods is being perceived to be associated with application of more agrochemicals. This study found that limitation to application of agrochemicals on food crops is not environmental stewardess per se but capacity to buy and use the chemicals. It was also clear that there are no standards set for agri-foods sold on the local markets regarding what level of agrochemicals are safe for consumptions.

- Rising cost of agrochemicals; The farmers reported that the current farming system is expensive compared to the past farming system. They claimed that in the past decades, smallholder farmers did not have to apply chemical fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides because the need was less. Nonetheless, the current farming system, requires fertilizer, pesticides and herbicides. Such inputs are said to be expensive. With the high inflation experienced over the past four years, now at over 30% [25], the claim is true. Prices of fertilizers, other agricultural chemicals and hybrid seeds have more than tripled since 2020. While produce is also fetching relatively better prices, farmers are still in a difficult situation. In responding to the barriers, the findings suggest that farmers have been working to substitute some of the farming practices. This tallies with the findings in the characterization of the farmers on agroecology typology which sound that they are at the efficiency and substitution level and not yet on the re-design stage.

3.1.1.1. Are Farmers Happy with the Current Farming Systems?

- Lack of reliable markets; While produce markets are plenty, reliable and value markets are scarce. Farmers indicated that majority of them sell their produce to the vendors offering low prices and sometimes tampering with weighing scales in their favor. Consequently, the farmers fail to recover the high costs incurred required inputs to practice the current farming systems. Government sets minimum price for crops, but most vendors do not comply as the prices are determined by largely forces of supply and demand.

- High cost of production due to an increase in the prices of inputs such as fertilizer, pesticides, herbicides and rentals; The FGDs revealed that most farmers hardly make profits. They also expressed anxiety that Government has reduced the number of AIP beneficiaries, yet the prices of the inputs are high.

- Lack of food safety; There is no guarantee for food safety in the food system from production to consumption. Farm produce does not sufficiently go through proper standards to determine safety of food consumptions. It is only processed foods that in some cases go through Malawi Bureau of Standards (MBS) certification system. Nonetheless, not all processed foods consumed on the markets go through the MBS.

- Lack of environmental stewardess; There is lack of food waste management. Methods of production such as heavy use of agrochemicals contaminates water bodies and affect soil health over time.

- Inequality; There is inequality between farmers and other actors. Other development actors have more powers when it comes to governance. They also get more rewards. Furthermore, within the farmers, smallholder farmers and less better off are now empowered to deal with the dynamics on the free market where vendors are loose. Within households, women still lag in terms of decision making on production and sharing of proceeds.

- Low agricultural productivity; There is still overall low agricultural productivity despite the high consumption of agrochemicals.

- Lack of efficiency; Majority of small-scale farmers hardily use proper technologies in farming and value addition. There is more reliance of the human manual labor that is often inconsistent in quality unlike if farm mechanization is embraced. For instance, a hoe is still the main farm implement.

3.1.2. Future Aspirations of Farmers on Agriculture and Means of Getting There

3.1.2.1. Farming Systems Preferred by Farmers in Future

3.1.2.2. Means of Achieving the Future Farming Systems and Barriers

- Financing; To reach the desired farming systems all the farmer categories indicated a need for both financing raised from the farm and sourced from FIs.

- Markets; While markets of all forms of produce are available to farmers and other upstream actors, low profitability is the principal issue according to the study. The common market for most farmers, as found in this study, was vendors being off takers/buyers. Vendors represent the aggregators that often buy produce at farm gate level either as individual or representing big companies. According to the subsistence farmers (especially those not in any farmer group) interviewed, they indicated that some of the vendors even buy the green crop right in the field before the harvest. What was common from all the interviews was that vendors determine the price of the commodities of the producers despite them just being the buyers. Ordinarily, farmers would need to be the ones making the price offers. To survive in this terrain of the buyers dictating prices, the consolation is when there are many buyers from whence farmers choose to earn a better price. In the event of all the prices on offer being lower than expected or below the breakeven price, the farmers sell at a give-away price because they are often destitute to earn the money for meeting immediate household needs.

- Technical and material capacity building; Among the wide range of small-scale farmers interviewed, it was reported that they lack knowledge and skills on the desired farming systems such as agroecology and organic farming. The core reason mentioned for the limited knowledge and skills for the future farming systems was inadequate frontline extension workers with capacity to perform the functions of supporting the farming systems they target to undertake. There was an acknowledgement that even though NGOs who promote sustainable agriculture are spread across the country, they are limited by funds in terms of reaching out to all groups of farmers who may have interest. However, the farmers mentioned that the government extension frontline workers are in majority, and that even the NGOs use the same staff to train them. The farmers also believe that not only frontline extension workers are inadequate but also majority promote the conventional agriculture which is what the government mainly supports. Thus, the government’s subject matter specialists (SMSs) and the frontline staff are trained and specialized in the conventional agriculture.

- Land tenure; Farmers acknowledged that they would need land for investing their desired farming systems. Some farmers claimed that they have enough land to practice all manner of farming systems they wish to undertake. This was mostly reported in Misuku Hills and Lisasadzi. However, not all farmers have land they can call their own. Due to shortage of land, some farmers rent land annually which affects their decision to invest the sustainable production practices into it. On the other hand, farmers were also against ideas of land consolidation per given area because it would take their rights away on what they choose to produce. They feared that people will no longer practice the farming system they want but rather practice what the cooperative wants. The issue concerns policy initiative on land governance so that those willing to cultivate and mange land sustainably should be given a chance to own land.

- Infrastructural development at policy level; Many farmers live in areas with potential for irrigation which could potentially align with desired farming systems for meeting goals of food security and income. Nonetheless, they need external support to invest in such infrastructure on the diverse value chains and farming systems they would indulge in. The infrastructure could include constructing dams and irrigation canals. Dams would not only support irrigation but also fishing and livestock farming. The farmers in Chikwawa, for instance, suggested that they need more projects/interventions supporting the households in dealing with floods in our community. For instance, developing irrigation infrastructure that is durable and that could withstand floods. This is because the areas experience floods that wash away crops and livestock almost every year.

- Incorporation of ideas and experiences of farmers in technology development; Farmers indicated that they would like to see research into technologies concerning the future farming systems incorporating their ideas and experiences. Farmers showed awareness on the potential of indigenous knowledge to support advancement of farming systems. By indicating a need for farming systems that should resemble the old ways of farming before they followed some of the “destructive scientific ways of farming”, small-scale farmers are acknowledging the importance of some of the ways of farming passed on from generations to generations.

- Promote by-laws to support some sustainable farming systems; The future farming systems will require landscape approach to implementation if they are to make meaningful impact. The current way of managing livestock is free grazing rights where farmers free up livestock during the dry season as the community only guards the rainfed farming systems. Thus, livestock destroys all the grasses and residences, or mulch kept deliberately by farmers willing to change their farming systems. Also, plants kept in the farms after the rainy season are browsed by livestock from other community members disturbing the design of the farmer per those willing to transition. So, farmers willing to transition to other farming systems apply more effort to make it work such as guarding the farms or fencing around it which makes it costly, increase work burden and less attractive.

3.1.3. Current Aspirations of EAS Actors on Agriculture

3.1.3.1. Issues with the Current Dominant Systems Supported by Extension

- The dominant farming systems are destroying soil structure and soil health because of wider application of agrochemicals (leading to acidity and creation of hard pans), tillage systems and increasingly monocropping planting patterns that leave the soil vulnerable to soil losses; The chemicals are also killing microorganisms and thus slowing down decomposition of organic matter.

- There is higher incidences of pest and disease attacks on crops than before; Some of the reasons are that crop varieties and breeds are hybrid and less adapted to local conditions. The problem was also attributed to climate change effects which were said to provide conducive environment for proliferation of the pest and microorganisms.

- Limited access to finance for investing in agricultural enterprise for operational costs and capital expenditure; Farmers need large amounts of land, inputs, labor and machinery for enhancing efficiency. An example was mentioned of AGCOM which supporting some farmers in cooperatives. However, majority of farmers remain outside cooperatives and only cooperatives with capacity to contribute access to this finance were said to benefit such financing opportunities. The financing gap was said to worse due to the need to incorporate efficiency and sustainable agricultural practices in the current farming systems which need more input investment. An example was provided by one of the key informants saying that the maize planting system of 1 x 1 demands more farmer labor and input likewise system rice intensification.

- Many farmers for a long time have been running on low profitability because of low agricultural productivity and limited access to profitable markets; This is when a proper economic analysis is applied to the enterprises. Reasons for the low profitability from the supplier side (farmers, such as low financial capital, low technical capacity, limited agribusiness skills and other support), and buyers (exploitative business strategies).

- Limited agricultural diversity; Many farmers do not produce enough diversified crops and livestock systematically (number of species and evenness); In the process, some crop species and livestock are not highly practiced. For example, common crops included maize, soya, groundnuts and tobacco, coffee (north), sesame (lower shire). On livestock, it is usually cattle, goats, pigs and chickens. Other unconventional livestock such as ducks are not commonly raised despite that they multiply faster than most of the conventional livestock.

- There is poor government policy and legal framework on investment in agriculture: i.e. Investing in subsidizes agrochemical, poor regulation of extension and markets, low mechanization, ow investment in infrastructure and equipment, food safety at all levels of agriculture and limited land.

3.1.4. Aspirations of EAS Actors on Future Agriculture and Farming Systems

- To see farmers adopting agricultural technologies that enhance productivity for food and income independence; EAS should ensure it supports farmers in using sustainable farming practices such as manure application, tree planting, mulching, crop intercropping and others. They should be using practices that will help address the twin goals of restoring soil health and increasing production.

- To see farmers achieving higher agricultural productivity and efficiency; For instance, farmers should grow more food using few resources for them to have sufficient food throughout the year and to go into commercial farming to improve their livelihoods. With this, the broader goal is for Malawi to be a nation that can achieve zero hunger and poverty reduction.

- To see farmers sustaining attain food security and nutrition;

- Farmers indulge in not only food security drive but also in commercialisation and do profitable farming;

- To see farmers able to survive through climatic shocks such as floods and droughts.

- To see inclusive farming;

- Government would employ more extension workers to bridge the extension officer to farmer ratio considered small; Furthermore, NGOs should employ their own extension officers instead of using the government staff whom the government is relying upon.

- Farmers should have access to a wide range of information on sustainable farming systems on the sustainable farming practices; For enhancing instrumental value, extension actors would need to train the community-based farmers and the lead farmers so that they should have enough knowledge on the sustainable farming systems to share to other farmers in the community.

- Demand driven approach would be implemented but augmented with paid extension services to enhance its sustainability.

- Extension should be there to make sure that the recycling of wastes and residues is being promoted and practiced by the farmers because it is one way of restoring the soil health by replacing back the nutrients absorbed by the crop residues than burning them.

- Extension should promote principles of farming that will lead to the ecological balance. Farming practices followed by farmers should be those that consider all the elements of the environment and their interaction for a better future farming system.

- Extension should make sure farmers are using their resources/inputs efficiently and effectively and increase their productivity and profitability.

3.1.4.2. Opportunities and Means of Getting There

- Current extension promotes participatory rural appraisal tools which help identify challenges farmers are facing such as village mapping, transect walk, focus group discussions, farming calendar, wealth ranking, preference ranking etc.

- Extension system in Malawi has established structures at all levels, district level, EPA level and village level; The structures, called DAESS offer potential for stakeholders to interact with each other. There are also innovation platforms/local structures that could be used appropriately for extension. For instance, stakeholders mentioned that they DAECC which can regulate how extension services should be delivered and implemented in the district by different organisations. This can be taken as an advantage to make farmers demand whatever they need for farming. However, functionality of the structures is varied across the country, with others having completely non-functional ones.

- There is gap between the actual productivity and the potential productivity. The gap is wide and needs to be minimized; This gives researchers and extension actors a need to work to provide relevant information which could help address the gap.

- There is a growing younger generation interested in farming that has potential to champion the digital agriculture and artificial intelligence.

- Some farmers still have land to use for investment permanent ways of farming; For example, in Chitipa, due to patrilineal type of family system, farmers have more land and will not be limited to practice any technology and farming system.

- There are some organisations that are promoting sustainable agricultural practices where farmers could get technical and other form of support; in Chitipa, a project under Self Health Africa was focusing on carbon credit through promoting tree planting among farmers. There are a lot of agricultural cooperatives where farmers can join and undertake commercial farming activities.

- Policies also somehow mention aspects of a need for farming to be resilient to shocks and profitable which suggests areas of agreement.

- Huge local and export markets for many commodities exist. The key challenge remains quality and quantity also related to lack of market information and unregulated exploitative behavior. Any farming system that addresses these may help unlock market potential.

- Malawi is producing many qualified young men and women who have completed their studies from different institutions. If the government can employ these energetic young men and women, the ratio of extension worker to farmer can balance.

- Some of the areas have rich and diverse natural capacity for supporting future farming systems. For instance, in Misuku EPA, they have hills full of natural vegetation that provides farmers with a diverse choice of farming systems they want to engage in like bee keeping and tree farming like pine tree which increases the economic sustainability of the farming family. They are also receiving the reliable rainfall compared to other areas.

3.1.4.2. Barriers of Getting to the Desired Future Farming Systems

- Limited financial resources limited actions/interventions by both government and NGOs; According to the extension workers, the government does not provide enough resources which would help to achieve their planned activities as a result such as field days, demonstration and facilitating farmer field schools. As mentioned, there is high vacancy rate in most subject matter specialists and frontline extension workers in government (40-60 % vacancy rate). This implies inability to reach out to many farmers. Most of the research taking place is donor driven. The donors have their own strategies which may not sync with that of the government. The research stations also do not have well trained stuff to collect the required data on the ground for evaluation of research technologies Furthermore, they do not have state of the art facilities and equipment for research and innovation.

- Coordination of different stakeholder remains a challenge; Government and some NGOs sometimes pull farmers in different directions. With the farming systems, it is the same. Government systems or offices just accept any interventions that are not suited with the area

- Farmers, researchers and extension actors are not ready to take up the farming systems yet; Their mindset is still focused on the current farming systems. Some farmers resist uptake because they do not see immediate benefits on the sustainable farming practices.

- Climate change effects such as droughts, floods, pests and diseases are greatly making extension and research difficult; For instance, the climate is continuing to change now and again so we are afraid that our sustainable farming practices that we perceive that are functional now might not work tomorrow.

- Lack of infrastructure. Poor roads, warehouses for farmers limited access to market opportunities; Poor housing of extension workers gives an excuse to frontline workers to stay away from workstation. Offices look dilapidated and thus not motivating the frontline workers.

3.2. Perceptions of Stakeholders on Why Agroecology is being Promoted in Malawi

3.3. Alignment of Agroecology with the Commercialisation Agenda in Malawi

3.3.1. Small-Scale Farmers

3.3.2. Medium-Scale and Large-Scale Farmers

3.3.3. EAS Actors

3.3.4. Private Sector (Agrodealer Suppliers, Off-Takers, Financial Institutions)

3.3.5. Consumers

3.4. Consensus and Dilemmas on Negotiating Agroecology Agenda

3.4.1. Consensus (Convergences and Synergies) on Agroecology

3.4.1.1. Dilemmas (Divergences and Trade-offs) on Agroecology

- Farmers; Generally, farmers indicated that they are reached out by EAS actors with several key sustainable agriculture approaches being promoted namely agroecology, permaculture, CSA, organic agriculture and regenerative agriculture. Since multiple variants of the sustainable agriculture approaches beside agroecology are promoted in the same communities or across the communities, the farmers reported that they are confused on which one works as there are agricultural technologies within these approaches that overlap and at times contradict. The sustainable agriculture approaches are either promoted concurrently or across time depending on circumstances. EAS actors mentioned motivation being the self-interest or availability of development funds [based on what approach is trending at a given point in time]. Another dilemma among the farmers is when the same EAS actor, especially the government staff, comes with different opposing initiatives. For example, the same EAS actor promoting conventional agriculture in another project and then promotes sustainable agricultural practices in another project or when another NGOs shows up. According to the farmers, the EAS actors ignore the other approaches when focusing on another approach, instead of promoting them together and asking farmers to make choices themselves. The challenge does not only apply at the farming system level but also at the agricultural technology level. For instance, agricultural component technologies promoted as individual technologies by different EAS actors are sometimes viewed as competitors.

- ○

- Farmers perceived agroecology to be feasible in meeting household food needs but the prevailing conventional food market demand: Farmers of this category aim at realizing high yields to achieve food security and high income. During the FGDs, farmers who claimed to be practicing agroecology doubted if agroecology could produce surplus to meet the market demands. The farmers acknowledged that they have been exposed to market-oriented extension where they are urged to produce based on what the market demands which sometimes leads them into specializing into commodities fetching high prices while other species are neglected. They reported that organized markets demand more quantities of one crop and they do not care how the commodity was produced. For the farmers who claimed to use sustainable agricultural practices, they mentioned that it meets their food needs, it is resilient and diversified but it is not based on market demands.

- ○

- Farmers perceive agrochemicals to be more effective than alternatives while also acknowledging their negative side effects in the soils. The FGDs informed that Farmers revere agrochemicals. They clearly believed that they are more effective than alternatives like botanicals. For instance, they believe chemical fertilizers contain essential nutrients required for plant growth even though it degrades the soils. So, they must make a choice of attaining bumper yields while at the same time degrading soils. Another exam-le mentioned was where farmers cultivating on large land that need more labor opt for herbicides to kill weeds even though they claim these chemicals affect soil health in the long run. Thus, farmers weigh on the productivity gains and environmental aspect and from the FGDs, the former supersedes for majority of small-scale farmers. When asked why they take the perceived risk of using agrochemicals which they know the side effects, they reported that they are more pressed with the food and income than they worry on the condition of soils which take time to reveal.

- ○

- Conventional agriculture offers immediate needs while agroecology largely offers long-term benefits. FGDs with the small-scale farmers revealed that farmers opt to use conventional agricultural practices when they are looking for immediate results -i.e. apply chemical fertilizers to have bumper yields in a given season. According to the small-scale farmers, sustainable agricultural practices offer long-term benefits such as improvement in the soul structure and regain soil fertility among others. For example, some agroforest trees such as Faidherbia albida several years to impact on the soil health.

- ○

- Farmers have a feeling that their innovation in sustainable agricultural practices are not embraced by the external EAS actors. Farmers expect extension actors to incorporate the knowledge of farmers in various sustainable agricultural practices because they have experiences that they believe work in their areas. However, they indicated that external EAS actors are more interested in them to use what they are promoting [foreign agricultural technologies]. They admitted that they need these foreign agricultural technologies which have also helped them in many ways such as the hybrid seeds and many other ways of conserving land (i.e. vetiver, making swales, ridge alignment and making compost manure). However, they also wish if the EAS actors were able to pay attention to their knowledge and innovation and incorporated it or advise where they should improve.

- ○

- Agroecology and other sustainable agricultural approaches are not being tailored to different farmer categories. The farmers constitute diverse categories (men, women, agribusiness versus subsistence, youth, adolescents, the elderly, persons with disabilities and the illiterate etc) which come with needs and interests requiring different approaches and interventions not available as others are being left behind. Farmers reported that some farmer groups with more resources are widely targeted in many projects that advance the initiatives to act as role models who do not have the same resource endowment and talent.

- ○

- Farmers feel EAS actors have not helped address their perceived unresolved challenges with some of the sustainable agricultural technologies promoted. During the FGDs, small-scale farmers reported that they feel like there is competing demands for some of the raw materials used in the sustainable farming methods. For example, some farmers are close to urban areas or are trading where maize residues are used in place of the scarce firewood mulching in their field. Maize bran is also used as feed for livestock and sometimes food for people. The FGDs also informed that some of the sustainable agricultural technologies resolve one farming problem while giving rise to another farming problem. For example, some farmers organized in a farmer field school experienced more worms that affected their produce when they mulched their fields to reduce water stress. Other farmers experienced reported increased termite incidences when they mulched their fields. According to the farmers, EAS actors seem to pay little attention to their experiences with these technologies as they shift attention towards promoting new agricultural innovations. In some areas, farmers with interest in substituting fertilisers with manure, they are afraid of floods that wash away the manure [this was reported mainly in Chikwawa where they experience frequent floods], yet EAS actors seem to not help them in dealing with such problems.

- Extension Actors (Government, NGOs and Universities): They generally all want to enhance food security and income among households; They also understand that generally, what is right is that extension should be participatory but they continue to apply transfer of technology model which implicitly or explicitly still apply transfer of technology. The dilemma is described in the following paragraphs;

- ○

- The funder is righter than the recipient [farmer] on what intervention should be promoted Public EAS actors informed that the ministry-based extension and research system promote agricultural technologies among farmers it considers appropriate; Government promotes using own operational funds and sometimes using funds or grants to implement flagship projects of its interest. Where government gets funding from development partners, the study found that the projects are also usually implemented using the conditions of the funder which largely promote transfer of technology regardless of the relevance. In a similar fashion, NGOs empower communities and households based on the interests and priorities of their development partner (provider of funds). The development partners set the agenda; whether supporting conventional agriculture, sustainable agriculture or a mix of the two types of agriculture. NGOs were found to being able to alter their mission and goals to adapt to funding opportunities for their survival. The key informants further revealed that they work hard to fit in the interests of the funding windows. In some cases, NGOs have long-term development partners who sync well in terms of the NGOs and the partners priorities.

- ○

- Many EAS actors no longer have passion to serve the needs of farmers but their own hence affecting service provision. Some of the key informants were revealing that the latent or underlying interests of the EAS actors in promoting agricultural interventions is the financial incentives especially when funded project activities are concerned. It was mentioned that government staff during the single party era were often dedicated and passionate to helping farmers, households and communities. In this era, EAS actors were said to take pride in bettering the lives of the farmers. However, in the modern times, EAS actors were said to no longer have passion about service provision but rather focused on improving their own financial and material wealth at the expense of the farmers. Some of the veteran government policy makers were able to reveal that the policy reviews or development initiatives have actually become a money scheme. Government experts or development partners initiate these. Once the policy documents are developed and financial benefits realize, they go ahead to look for another policy to review or develop and so on. Some of the key informants even mentioned that this also the underlying reason why coordination and collaboration among EAS actors is still a challenge despite existence of many structures for enhancing functionality of the same because the need to share financial resources becomes an obstacle. With the income being the drive, EAS actors are more focused on the opportunities for fund-raising than the communities themselves. From these isolated ideas of projects driven by the need to access funding for own development, there are diverse and conflicting approaches used among the EAS actors depending on the source of funding. For example, other actors [mostly the NGOs] were said to be promoting dependence syndrome whenever they have funding. Government actors were said to avoid handouts outside their flagship projects due to low funding. It is also because of this situation that there is no objectivity from EAS actors on what farming systems are appropriate to the diverse farmers. Majority promote the conventional agriculture which has all categories of experts (government, NGOs, researchers, agrodealers etc) and attract support from development partners due to its scientific backing and involvement of multinationals in the economies of the developed countries. On the other hand. Sustainable agricultural approaches such as agroecology attract less development partner support and thus EAS actors [who are attracted to funding] because it is perceived to fight for its place against the dominance of the conventional agriculture regime.

- ○

- Having the desire to help farmers appropriately but low funding leading to poor support: Key informant interviews with EAS actors from the public and NGOs revealed that they lack adequate funding to holistically address some farmer needs which affect quality and quality of technical, financial and access to markets services and support. For instance, lack of adequate funding among the EAS actors leads to limited number of extension agents being employed. The funds are also limited extension activities such as field days and initiatives such as livestock pass-on or supporting farmers with seed capital.

- ○

- Perception of the EAS actors on the scale of farming at which agroecology can work: In line with what many farmers perceived, many EAS actors believed that most of agroecological practices could work better on a small -scale than large. According to them there has been a struggle in demonstrating applicability of sustainable production methods to large scale farms and predicting benefits (economic, social and environment) in the long term. The struggle, according to the EAS actors, emanates from the fact that agroecological practices are complex. For example, a farmer using Mbeya but also using other non-recommended technologies such as recycled seed which may be conceived to be low yielding. In such a way, it is difficult to attribute improvement of yield. When it comes to comparison between conventional and agroecological farming systems, there is bias in the assessment. Conventional assessment methods focus on comparing the economic aspect (yield and its income value), leaving out the social and environmental aspects. Such approach excludes externalities of the conventional agricultural systems which would add costs and reduce margins. On the other hand, they do not account for the multiple benefits of the agroecological farming practices beyond yield.

- Private sector (agrodealer suppliers, off-takers, financial institutions): The mainstream private sector revealed that profitability is what drives them to indulge into supply of agricultural input in any value chain or type of agriculture; According to some of the agrodealers interviewed, they often stock agricultural inputs that are certified which include hybrid seeds, pesticides, chemical fertilizers and many others. They also stock the mentioned agricultural inputs based on demand from various farmers. Against this backdrop, they explained that organic inputs are not certified and that the demand is low hence not being socked in. However, the agrodealers mentioned that there is an emerging niche market for organic inputs, mainly organic fertilizers, but being limited by lack of certification making farmers not able to trust the producers/suppliers. There are also many fake agrodealers, tarnishing the image of the certified agrodealers. These sell substandard agro-inputs to farmers. So even if agroecology inputs appear among such agrodealers, farmers may not immediately embrace them.

- Consumers: Consumers [people found on the markets] want food that is nutritious, safe and tasty; They also indicated that they are encouraged to buy food with guaranteed safety as they care for their health. For rural consumers, they said that they know what inputs are used for producing foods which include pesticides and chemical fertilizer which create some worry on how healthy the food is. For some urban consumers, they mentioned the need for food to not only be nutritious but also environmentally and socially conducive. The urban consumers mentioned that their the foods on their markets are not certified and that they cannot trace the producer. As such, they are not able to tell by observations whether the food is agroecological or not.

4. Discussion

4.1. Aspirations of Farmers and EAS Actors on Agriculture

4.2. Perceptions on the Agenda for Promoting Agroecology

4.3. Alignment of Agroecology with the Commercialization Agenda in Malawi

4.4. Consensus and Dilemmas on the Agroecology Approach

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| EAS | Extension and Advisory Services |

| NEEF | National Economic Empowerment Fund |

| AGCOM | Agricultural Commercialisation Project |

| SVTP | Shire Valley Transformation Program |

| AIP | Agricultural Input Program |

| FI | Financial Institutions |

| TRADE | Agriculture through Diversification and Entrepreneurship Programme |

| EPA | Extension Planning Area |

| FGD | Focus Group Discussion |

| MK | Malawi Kwacha |

| DAECC | District Agriculture Extension Coordination Commiteee |

| AASP | Area Agriculture Stakeholder Panels |

| AACC | Area Agriculture Coordination Committee |

| NGO | Non Govetnmental Organisation |

| CSA | Climate Smart Agriculture |

| LUANAR | Lilongwe Universtiy of Agriculture and Natural Resources |

References

- Gliessman, S. (2015) Agroecology: The Ecology of Sustainable Food Systems. Boca Raton: Taylor and Francis.

- IPES-Food (2016) ‘Uniformity Diversity From Uniformity’, p. 96. Available at: http://www.ipes-food.org/_img/upload/files/UniformityToDiversity_FULL.pdf.

- Gaitán-Cremaschi, D. et al. (2019) ‘Characterizing diversity of food systems in view of sustainability transitions. A review’, Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 39(1). [CrossRef]

- IPES-food, C. (2020) ‘COVID-19 and the crisis in food systems : Symptoms , causes , and potential solutions’, (April), pp. 1–11.

- Gliessman, S. (2016) ‘Transforming food systems with agroecology’, Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 40(3), pp. 187–189. [CrossRef]

- FAO (2018) Guiding the transition to sustainable food and agricultural systems the 10 elements of agroecology. Rome: FAO of the UN.

- Bilali, H. El et al. (2018) ‘Power and politics in agri-food sustainability transitions’, (July), pp. 1–5.

- Kpienbaareh, D. et al. (2020) ‘Spatial and ecological farmer knowledge and decision-making about ecosystem services and biodiversity’, Land, 9(10), pp. 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Wezel, A. et al. (2020) ‘Agroecological principles and elements and their implications for transitioning to sustainable food systems . A review’.

- Kemp, R., Schot, J. and Hoogma, R. (1998) ‘Regime shifts to sustainability through processes of niche formation: The approach of strategic niche management’, Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 10(2), pp. 175–198. [CrossRef]

- Markard, J., Raven, R. and Truffer, B. (2012) ‘Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects’, Research Policy, 41(6), pp. 955–967. [CrossRef]

- Isaac, M. E. et al. (2018) ‘Agroecology in Canada: Towards an integration of agroecological practice, movement, and science’, Sustainability (Switzerland), 10(9), pp. 1–17. [CrossRef]

- El Bilali, H. (2019) ‘The multi-level perspective in research on sustainability transitions in agriculture and food systems: A systematic review’, Agriculture (Switzerland), 9(4). [CrossRef]

- Bezner-Kerr, R. (2020) ‘Agroecology as a means to transform the food system’, 70, pp. 77–82. [CrossRef]

- Gliessman, S. (2022) ‘Can agricultural extension be of service to agroecology ?’, Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 46(7), pp. 953–954. [CrossRef]

- Razanakoto, O. R. et al. (2020) ‘Why smallholder farms ’ practices are already agroecological despite conventional agriculture applied on market-gardening’, Outlook on Agriculture. [CrossRef]

- Tittonell, P. et al. (2020) ‘Agroecology in Large Scale Farming—A Research Agenda’, Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4(December). [CrossRef]

- Lucantoni, D. et al. (2023) ‘Evidence on the multidimensional performance of agroecology in Mali using TAPE’, Agricultural Systems, 204(February 2022), p. 103499. [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, I. et al. (2025) ‘Assessment of the Agroecological Transition of Farms in Central Tunisia Using the TAPE Framework’. [CrossRef]

- National Planning Commission (NPC) (2020) Malawi 2063. Lilongwe: National Planning Commission (NPC).

- Kundhlande G, Franzel S, Simpson B. Gausi E. 2014. Farmer-to-farmer extension approach in Malawi: A survey of organizations using the approach ICRAF Working Paper No. 183. Nairobi, World Agroforestry Centre. [CrossRef]

- Bryan, A. (2012) Social Reseach Methodsمائیں. 4th edn. Oxford University Press.

- Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D. and Guassora, A. D. (2015) ‘Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies : Guided by Information Power Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies : Guided by Information Power’, (December). [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. (2014) Research Design: Qauntitative, qualitative and mixed approaches. 4th edn. SAGE Publications Inc.

- NSO and ICF (2024) Demographic and Health Survey-Key Indicators. Zomba.

- Julien et al. (2019) Assessing farm performance by size in Malawi, Tanzania, and Uganda. Food Policy Volume 84, April 2019, Pages 153-164. Available:. [CrossRef]

- Muyanga, M. et al. (2020) ‘The future of smallholder farming in Malawi’, Journal of Gender, Agriculture and Food Security, 2371(2022), p. 46. Available at: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/319855/.

- Biggs, S. D. (1990) ‘Agricultural Source of Innovation and Technology Model of Promotion’, 18(11).

- Ostrom, E. (2009) ‘A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems’, Science, 419(325). [CrossRef]

- Drinkwater, L. E., Friedman, D. and Buck, L. (2016) Innovative Solutions to Complex Challenges. Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE). Available at: http://www.sare.org/Learning-Center/Books/Systems-Research-for-Agriculture.

- Mottet, A. et al. (2019) Tape - Tool for Agroecology Performance Evaluation. Rome. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/ca7407en/ca7407en.pdf.

- Thierfelder, C. and Wall, P. C. (2011) ‘Innovations as Key to the Green Revolution in Africa’, in A. Bationo, B. Waswa, J.M.M. Okeyo, F. Maina, J. M. K. (ed.). Springer Science, p. 1269 1277. [CrossRef]

- Kaluzi, L., Thierfelder, C. and Hopkins, D. W. (2017) ‘Smallholder Farmer Innovation and Contexts in Maize-Based Conservation Agriculture Systems in Central Malawi’, Sustainable Agriculture Research, 6(3), p. 85. [CrossRef]

| Farm | Processing area | Market |

| holes watering canes secateurs pruning saw slasher chemicals fertilizer pails sacks |

pails sacks scale drying tables machines |

stationary (delivery notebooks, pen, calculator) sacks vehicles |

| EAS Actors | What farming system and extension they would like to see |

|---|---|

| DAECC | Labour saving technologies that still produce good results because some of the technologies we are promoting now are labour intensives and expensive like construction of live fencing around conservation agriculture fields. For example, farming system that promotes the use of machine instead of hoe. Technologies that should provide good results within a short period of time. i.e. Provide enough carbon credit and biomass within a short period of time to replenish the soil fertility. Farming system that integrates agroecology. Farming system that should suit with farmers working in groups like cooperative. Farming systems that include bio fortified crops like orange maize (MH44), beans, yellow sweet potatoes for improving nutrition Farming systems that enable communities have adequate income through agriculture commercialization. Farming systems that will enrich our soils with nutrients to harvest bumper yields with less inputs being used on the farm. Farming systems that will encourage the inclusion of animals in the system so that farmers should have diverse sources of nutrients and that animals should be providing manure to the farmers. |

| Researchers | Precision agriculture: farmers should be precious in the way the use their land and resources like farm input for high production. Increased human population requires land to be used optimally and that can only be attained if we employ precision agriculture. Digital agriculture to help in achieving precision agriculture to benefit the coming in of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in agricultural research and food system and advancement of climate smart agriculture and irrigation. |

| AACC | Farming systems that will be able to help the farmers in time of crisis such as floods as it is the major problem that farmers in the area face almost every year [message was strong in Chikwawa] Farming systems that will require the farmers to use less inputs especially the chemicals. Farming systems that will enable the farmers to produce more and be food secured throughout the year. Farming systems that embrace climate resilience, biodiversity conservation, and inclusivity. Farming systems that should aim to integrate sustainable agricultural approaches such as agroecology and to be adopted. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).