1. Introduction

The aerospace industry demands exceptional reliability and safety from structural components, making fatigue crack propagation one of the most critical failure mechanisms to understand and predict in aircraft structures [

1,

2,

3]. Aluminium alloys, particularly AA7075-T6, represent the backbone of modern aerospace engineering due to their exceptional strength-to-weight ratio and superior mechanical properties [

4,

5]. However, cyclic loading conditions experienced by aircraft components during service inevitably lead to fatigue damage accumulation, necessitating comprehensive understanding of crack initiation and propagation mechanisms to ensure structural integrity throughout the operational lifetime.

The fundamental understanding of fatigue behaviour in metallic materials has evolved significantly since Griffith's pioneering work on crack propagation theory [

6], which established the theoretical foundation for fracture mechanics. Miller's materials science perspective emphasized the critical relationship between microstructural features and fatigue resistance [

7], while subsequent research has demonstrated strong correlations between fatigue strength and other mechanical properties of metallic materials [

8]. This foundational knowledge has been further enhanced by comprehensive studies on micromechanisms of fracture and fatigue, providing deeper insights into the complex interactions between material microstructure and loading conditions [

9].

AA7075-T6 aluminium alloy has emerged as a material of choice for critical aerospace applications due to its exceptional mechanical properties and microstructural characteristics [

10]. Recent investigations have revealed the significant influence of grain structure and microstructural control on fatigue crack propagation behaviour [

11], particularly under varying stress ratios [

12]. The alloy's performance has been extensively characterized through various processing techniques, including spark plasma sintering, which demonstrates the material's versatility and potential for enhanced properties [

13]. Understanding the relationship between microstructure and mechanical behaviour is essential for predicting fatigue life and optimizing component design for aerospace applications. Enhanced properties can also be achieved through nanoparticle additions for improved grain stability [

14].

The theoretical framework for fatigue crack propagation has been significantly advanced through dislocation-based approaches, building upon the classical work of Cottrell on dislocations and plastic flow in crystals [

15]. Modern understanding incorporates sophisticated dislocation-based fracture mechanics [

16] and distributed dislocation techniques for solving complex crack problems [

17]. The cycle-by-cycle propagation theory for fatigue cracks at small stress intensity ranges has provided crucial insights into the mechanisms governing crack advancement [

18], while comprehensive theories of fatigue crack propagation continue to evolve.

The Paris equation remains a cornerstone of fatigue crack growth analysis, providing the fundamental relationship between crack growth rate and stress intensity factor range [

19]. This empirical approach has been complemented by numerical prediction methods based on cumulative plastic strain, offering enhanced accuracy in predicting fatigue crack growth behaviour [

20]. Recent advances in adaptive control approaches using magnetorheological dampers have shown promise in preventing low-cycle fatigue damage [

21], highlighting the evolving nature of fatigue mitigation strategies.

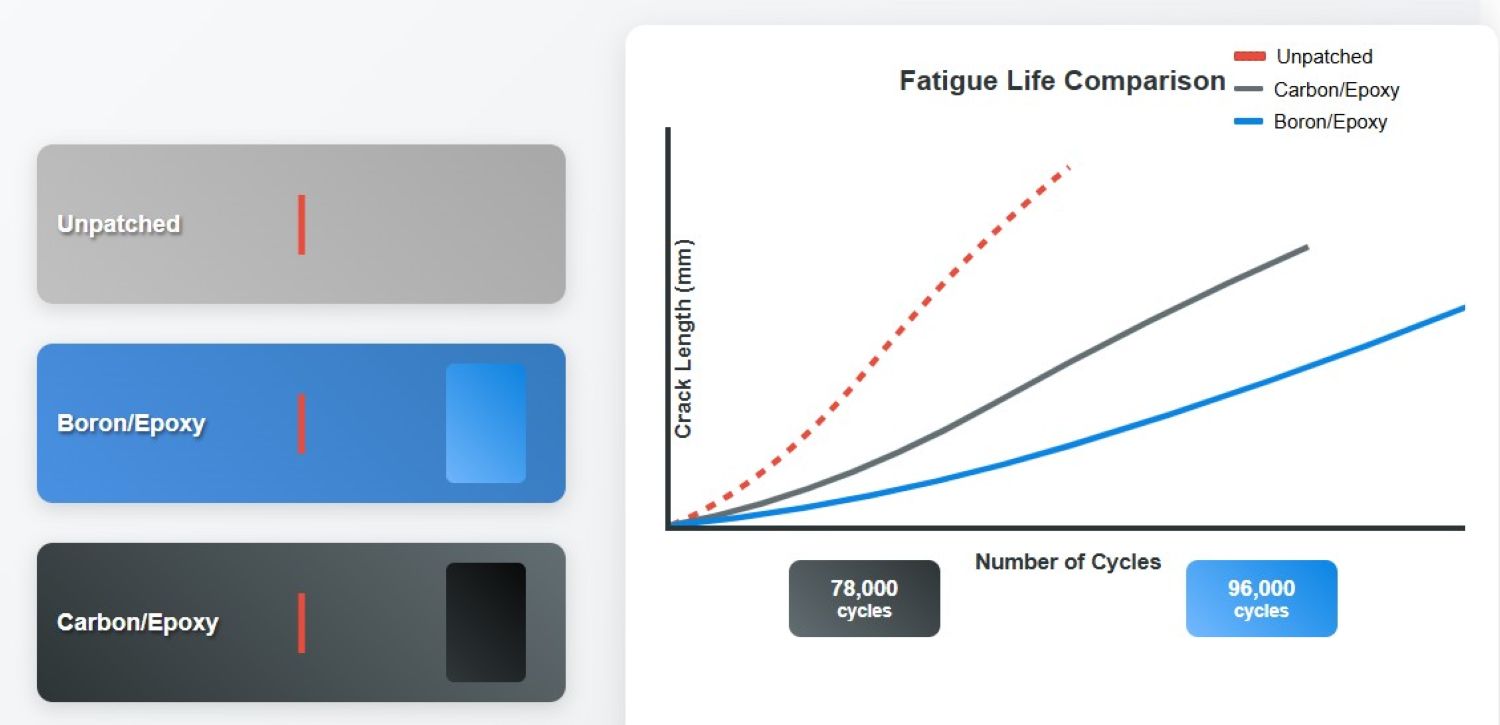

Repair and maintenance strategies for cracked aluminium structures have become increasingly sophisticated, with bonded composite patch repairs emerging as an effective solution for extending service life [

22,

23]. Research on J-integral evaluation of repaired cracks in AA7075-T6 structures has provided valuable insights into the effectiveness of various repair techniques [

4], while studies on the effect of curing cycles on fatigue life of repaired aircraft sheets demonstrate the importance of proper repair procedures [

5]. These advances in repair technology are crucial for maintaining aircraft structural integrity while optimizing operational costs and safety margins.

Despite significant progress in understanding fatigue mechanisms, critical gaps remain in comprehensively linking microscopic dislocation dynamics with macroscopic crack propagation behaviour under realistic service conditions [

9,

16]. The complex interplay between material microstructure, loading history, and environmental factors requires integrated experimental and theoretical approaches to develop predictive models capable of accurately assessing damage tolerance and remaining fatigue life [

11,

20]. Furthermore, the transition from small initial defects to critical crack sizes representative of emergency damage scenarios requires detailed mechanistic understanding to support immediate assessment protocols for temporary repair decisions [

1,

18,

22].

This research addresses these gaps through comprehensive fatigue crack growth testing of AA7075-T6 aluminium alloy using standardized ASTM E647 procedures, combined with mechanistic analysis based on dislocation theory and advanced characterization techniques. The study aims to provide essential data for damage tolerance assessments while contributing to improved predictive models for fatigue failure in aerospace structures, directly supporting enhanced safety and reliability in demanding aerospace applications.

2. Materials and Methods

This research was conducted at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), within the Material Sciences & Manufacturing (MSM) Operating Unit, specifically in the Light Metals (LM) Competency Area. The tests were carried out in the LM/MSM laboratories, with machining performed both at the LM workshop and the National Laser Centre (NLC) at CSIR.

2.1. Characterization of AA7075-T6 Material

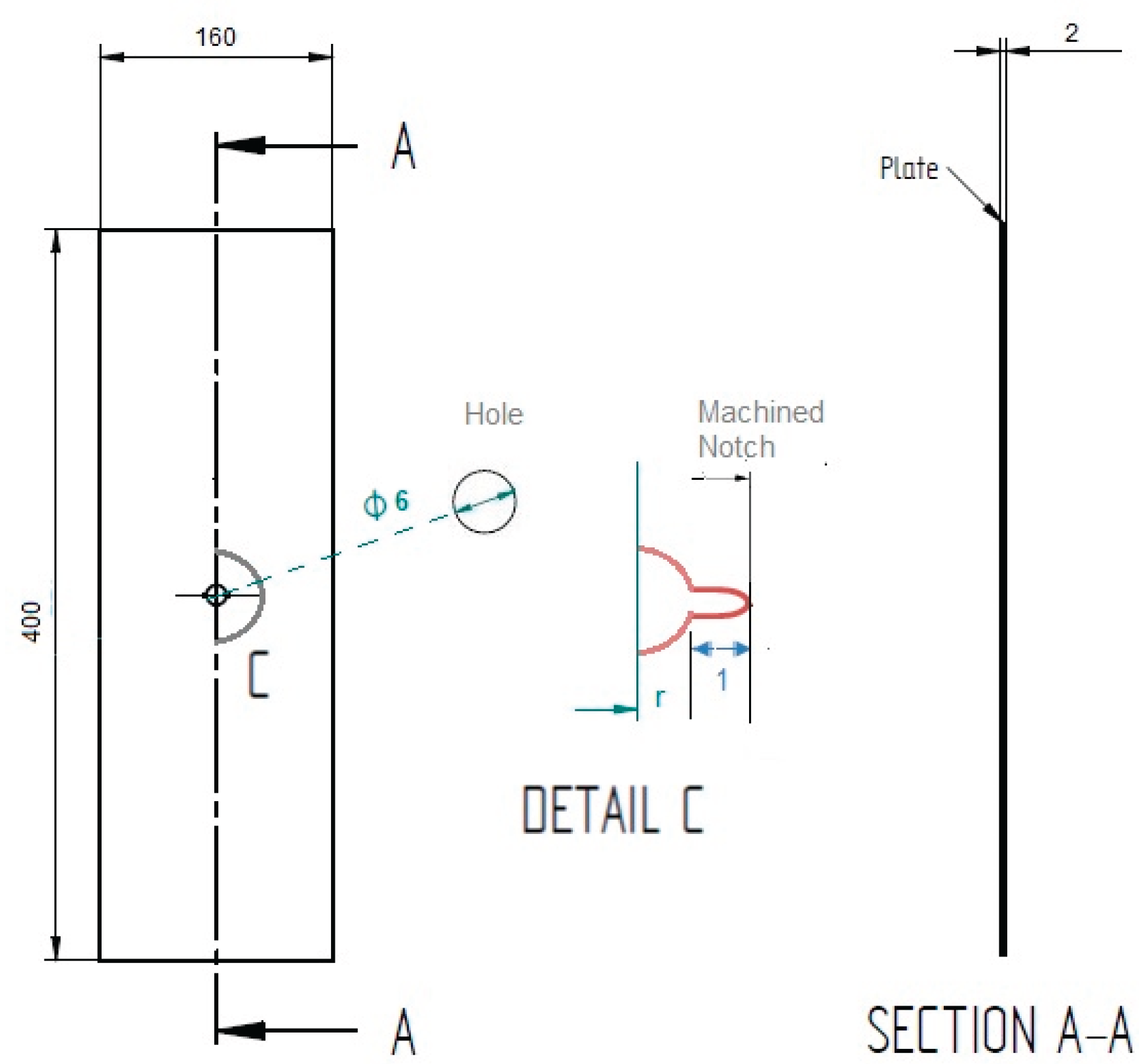

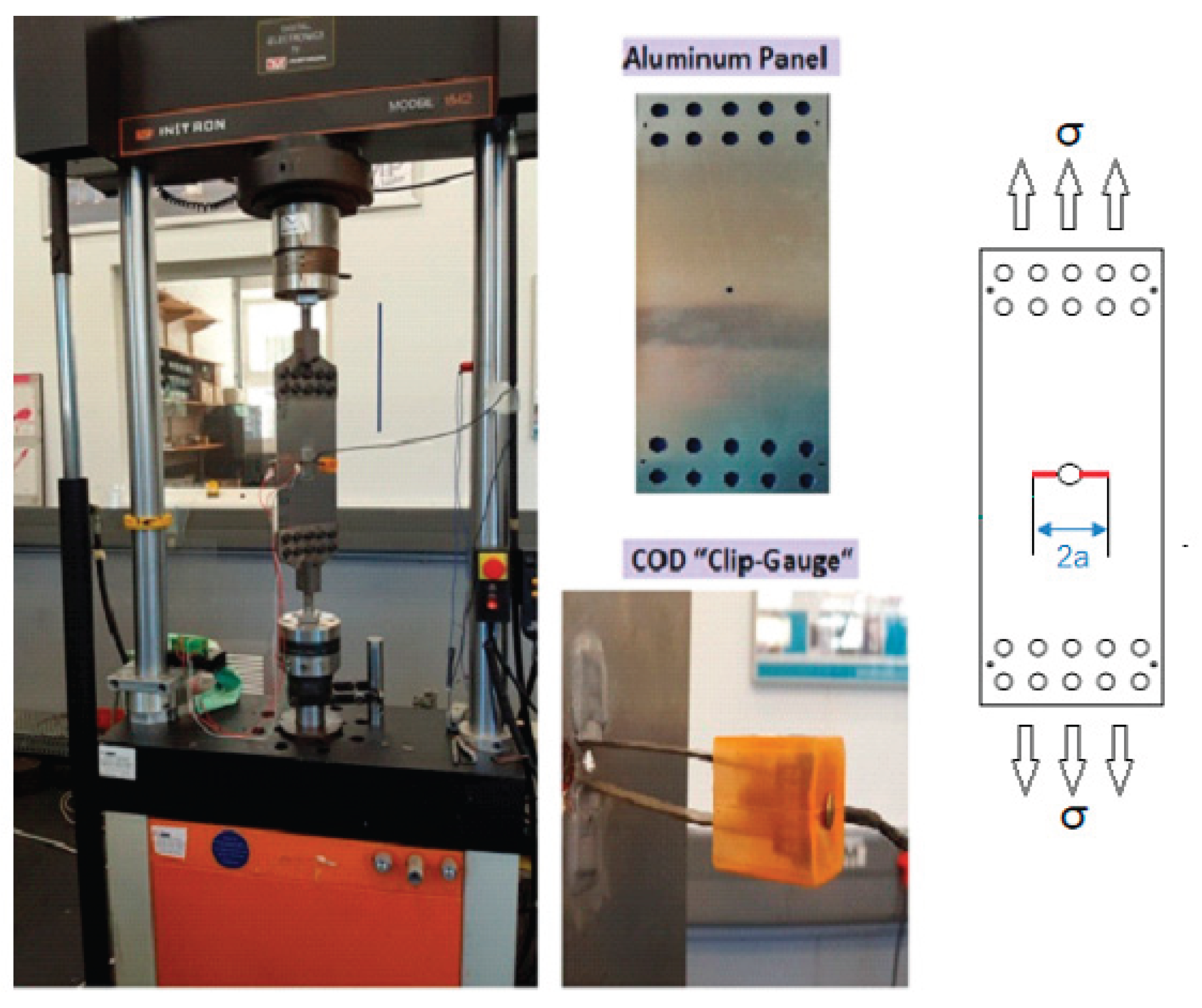

The aerospace-grade AA7075-T6 aluminium plate used in this study (

Figure 1) measured 400 mm × 160 mm × 2 mm and featured a 6 mm rivet hole with a 1 mm wire-cut notch extending perpendicularly from the hole's edge. Material certification (Lot #AA7075-2019-MSM) and storage conditions (ambient temperature, <50% RH) were maintained throughout testing. The material properties used in this research are summarized in

Table 1.

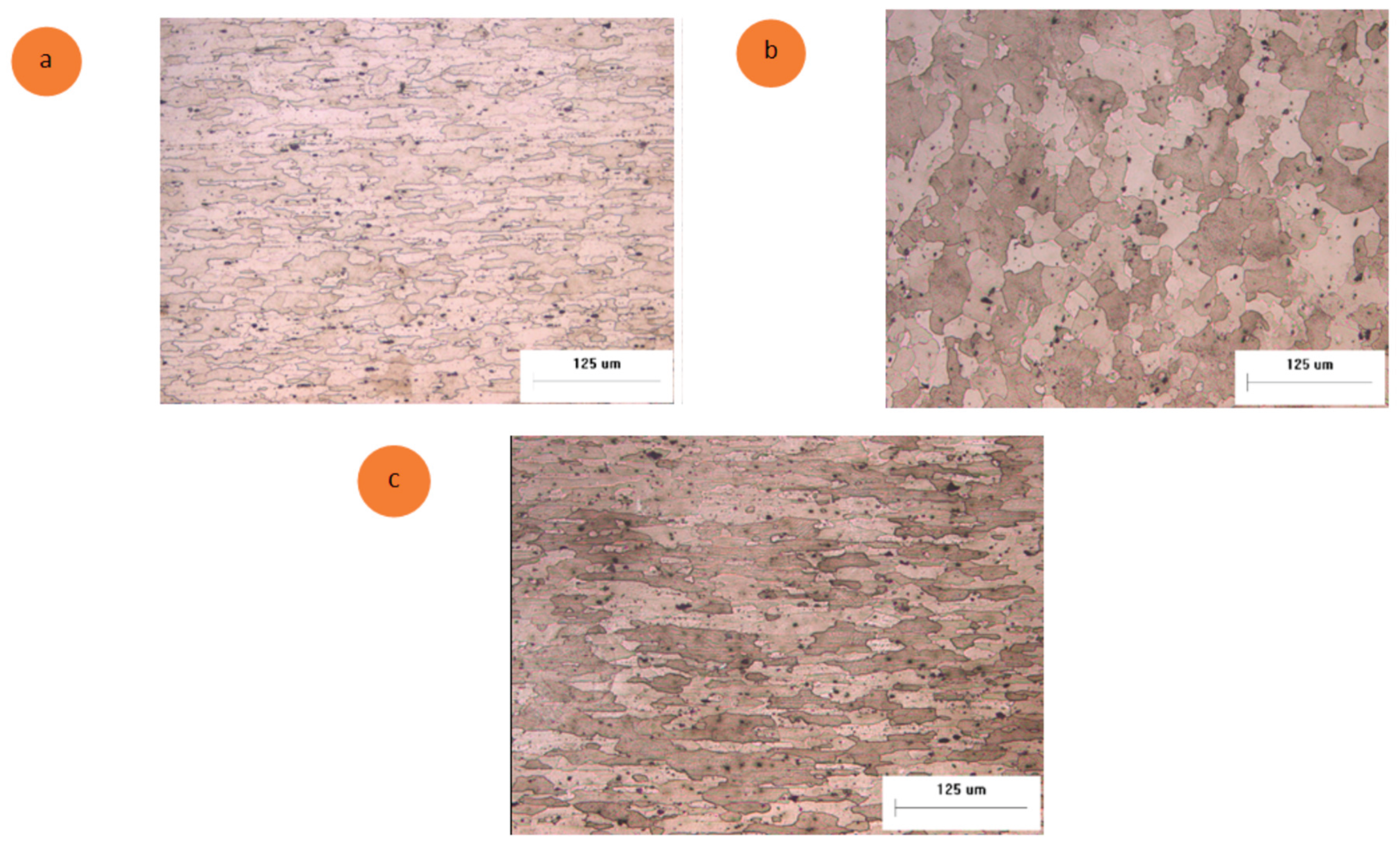

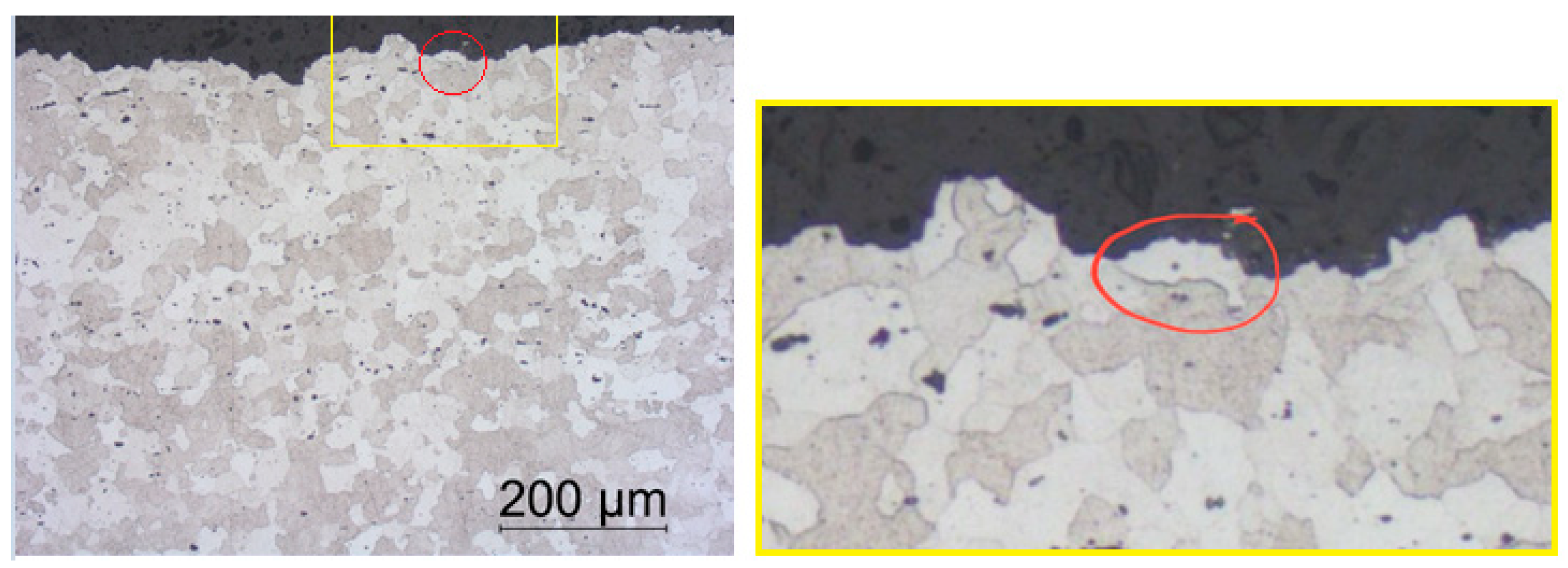

2.2. Microscopic Analysis of AA7075-T6 Plates

Optical microscopy was performed using a Zeiss Axio Observer microscope to analyse the grain structure, phase distribution, and defects of AA7075-T6 aluminium alloy sheets (

Fig. 2). This revealed a fine, homogeneous grain structure, vital for its strength and fatigue resistance, and helped identify elements affecting its performance in aerospace applications. Microstructural observations were conducted following ASTM E3-11 standard metallographic preparation procedures.

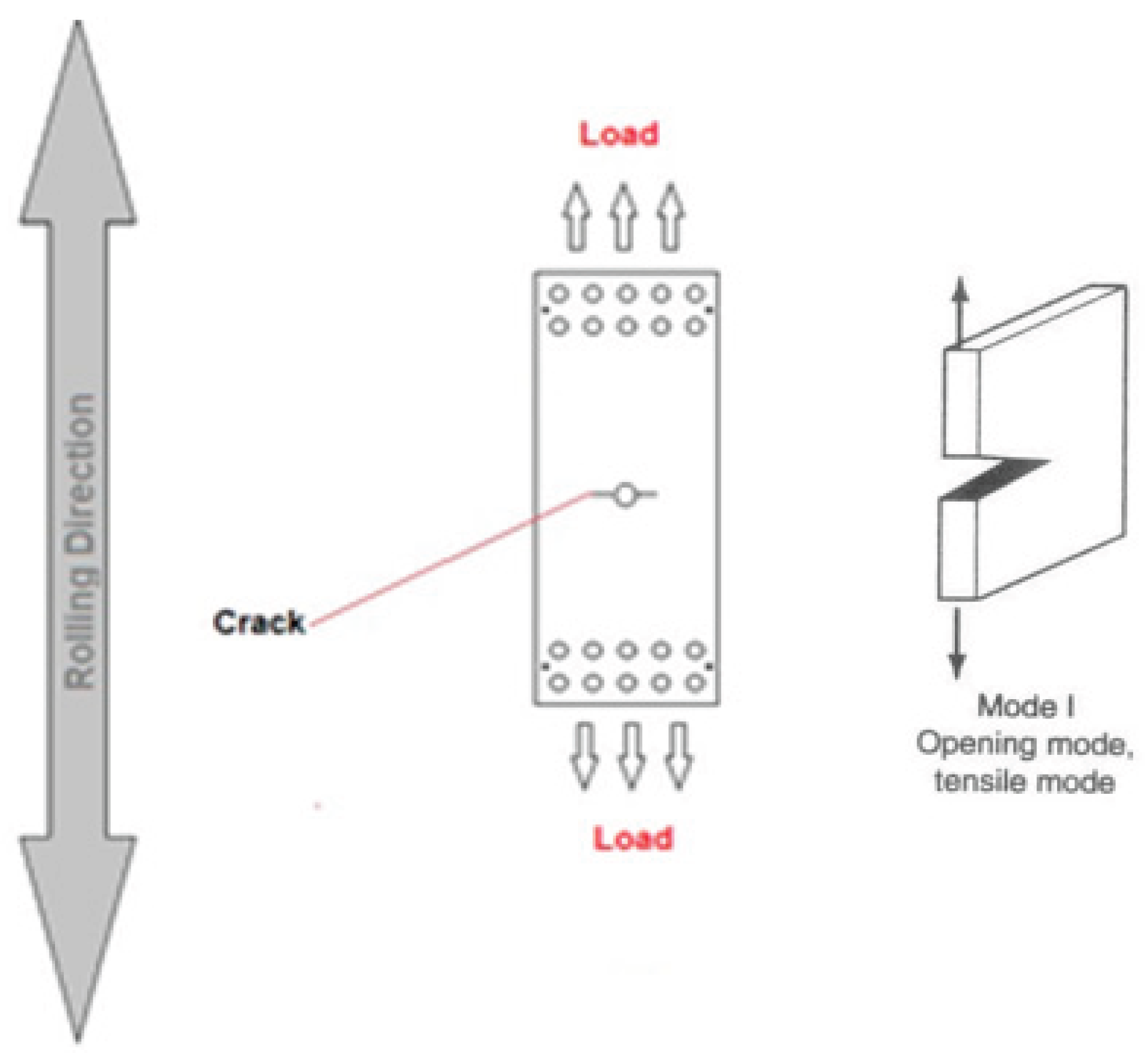

2.3. Fatigue Crack Growth (FCG) Testing

In fracture mechanics, different modes of fracture propagation are distinguished based on the loading conditions applied to the crack. Mode I, also known as the crack opening displacement (COD) mode, involves tensile stress applied perpendicular to the crack faces and is considered the most significant type of loading [

16]. The following discussion focuses exclusively on Mode I, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

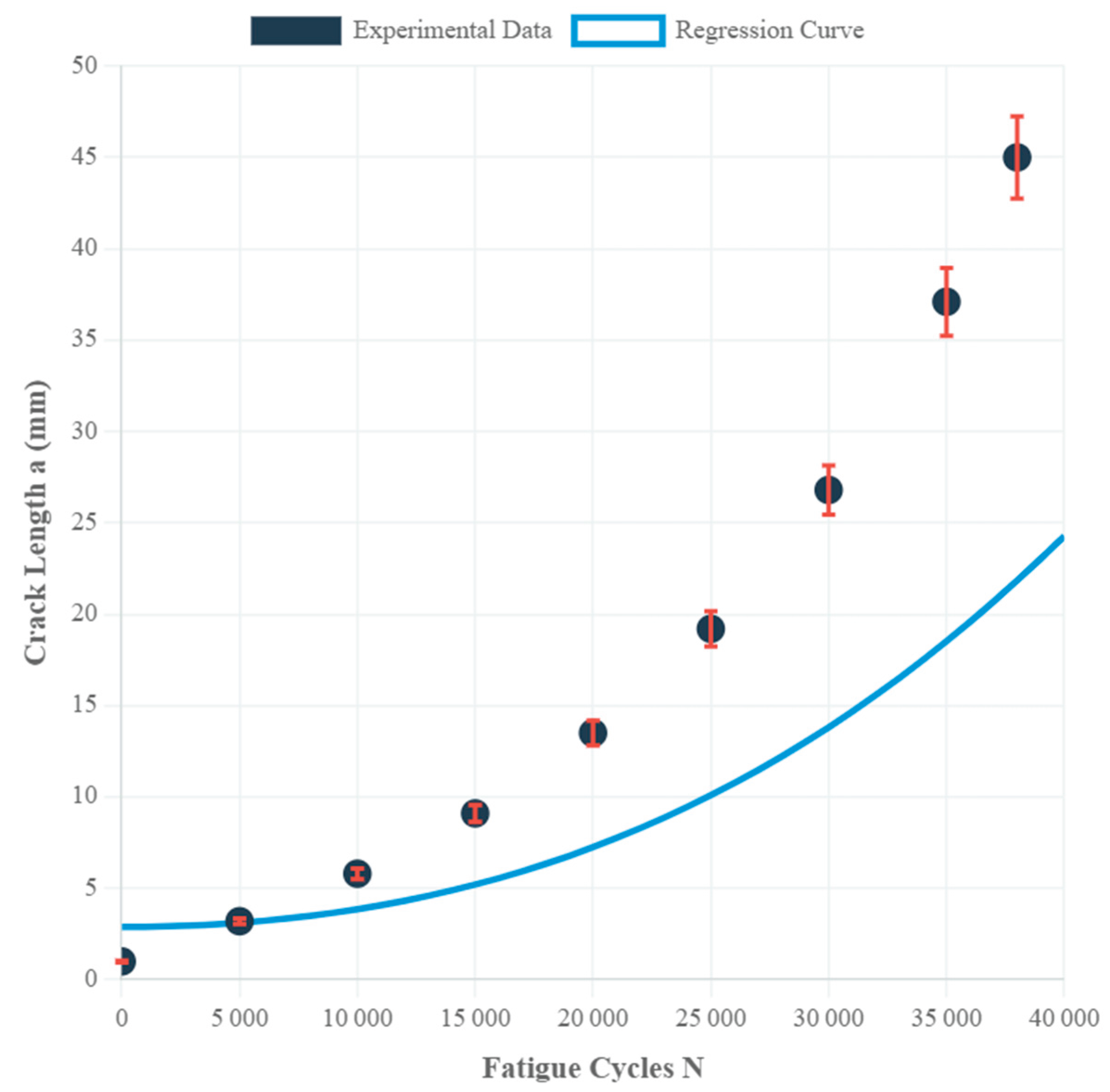

where a = crack length (mm), N = fatigue cycles

a = 2.89 + 8.45×10⁻⁹ × N2 + 1.23×10⁻¹3 × N3

R2 = 0.987

Fatigue crack growth tests were conducted using an Instron 1342-H1314 servo-hydraulic system with a dynamic capacity of 25 kN (

Fig. 4). All tests were performed in triplicate (n=3) with statistical analysis using Student's t-test (α=0.05) to ensure reproducibility. Instrument calibration was performed according to ASTM E647-15e1 standard procedures [

24], with load cell calibration verified to ±0.1% accuracy.

Table 2.

Testing conditions: 22 kN cyclic loading, 10 Hz frequency, stress ratio R = 0.1, room temperature (23±2°C). Error bars represent standard deviation from n=3 specimens. The polynomial regression shows excellent correlation (R2 = 0.987) with three distinct growth regions visible.

Table 2.

Testing conditions: 22 kN cyclic loading, 10 Hz frequency, stress ratio R = 0.1, room temperature (23±2°C). Error bars represent standard deviation from n=3 specimens. The polynomial regression shows excellent correlation (R2 = 0.987) with three distinct growth regions visible.

| Cycles N |

Crack Length a (mm) |

Error Bar (±mm) |

Growth Rate da/dN (mm/cycle) |

| 0 |

1.0 |

±0.05 |

- |

| 5,000 |

3.2 |

±0.16 |

4.4×10⁻⁴ |

| 10,000 |

5.8 |

±0.29 |

5.2×10⁻⁴ |

| 15,000 |

9.1 |

±0.46 |

6.6×10⁻⁴ |

| 20,000 |

13.5 |

±0.68 |

8.8×10⁻⁴ |

| 25,000 |

19.2 |

±0.96 |

1.14×10⁻3

|

| 30,000 |

26.8 |

±1.34 |

1.52×10⁻3

|

| 35,000 |

37.1 |

±1.86 |

2.06×10⁻3

|

| 38,000 |

45.0 |

±2.25 |

2.63×10⁻3

|

All fatigue tests were conducted at a constant cyclic load amplitude of 22 kN, with a frequency of 10 Hz and a stress ratio (R = σ

min/σ

max) of 0.1. Crack length data and the number of cycles were automatically recorded using a computer-controlled data acquisition system with a sampling rate of 10 Hz (

Fig. 5). Environmental conditions were maintained at 23°C ± 2°C and 45% ± 5% relative humidity throughout testing.

3. Results

The mechanisms underlying different fracture modes are described through interactions of dislocations, which involve complex slip and crystallographic relationships [

8]. While dislocation-based models provide insights into these fracture mechanisms, they are mathematically intricate and exceed the scope of this research. This study focuses on fatigue crack propagation in low cycle fatigue (LCF), specifically addressing slow-crack growth controlled by the material's fracture toughness, which is its resistance to unstable crack propagation.

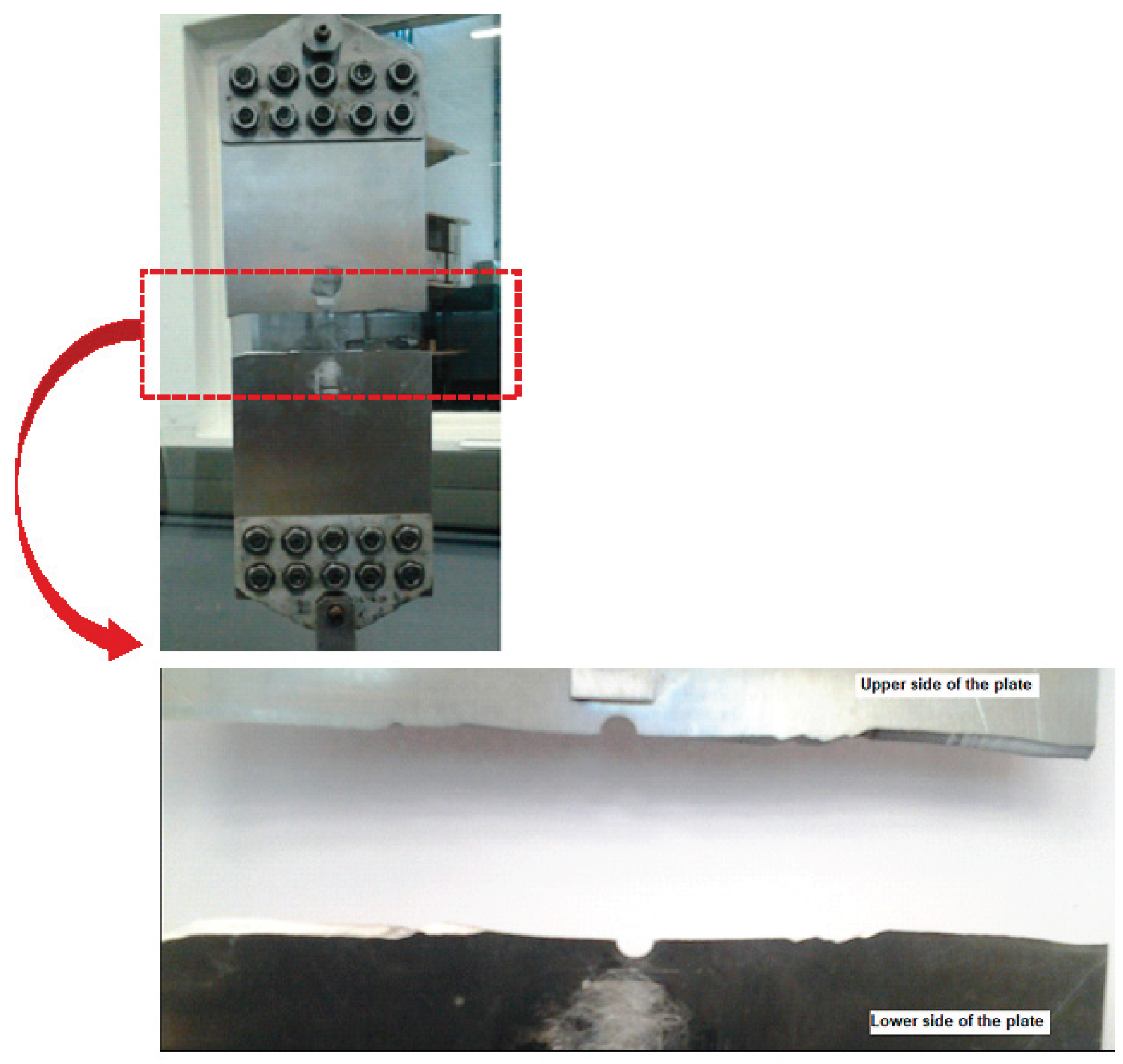

3.1. Crack Propagation Behaviour

Through visual observation and computer monitoring, it was found that all tested samples displayed consistent crack growth behaviour with excellent reproducibility (coefficient of variation < 8%). Initially, the crack propagated slowly and steadily in a straight path from the notch until reaching a length of 20 mm (±2 mm). Beyond this point, the crack began to deviate, forming a 45-degree zigzag pattern and accelerated its growth once it surpassed 35 mm (±3 mm) in length.

The experimental results revealed three distinct propagation regions (

Fig. 6):

Region 1 (0-20 mm): Slow, steady growth with growth rates of 0.036 μm/cycle

Region 2 (20-35 mm): Transitional behaviour with changing crack trajectory

Region 3 (>35 mm): Rapid acceleration leading to final fracture

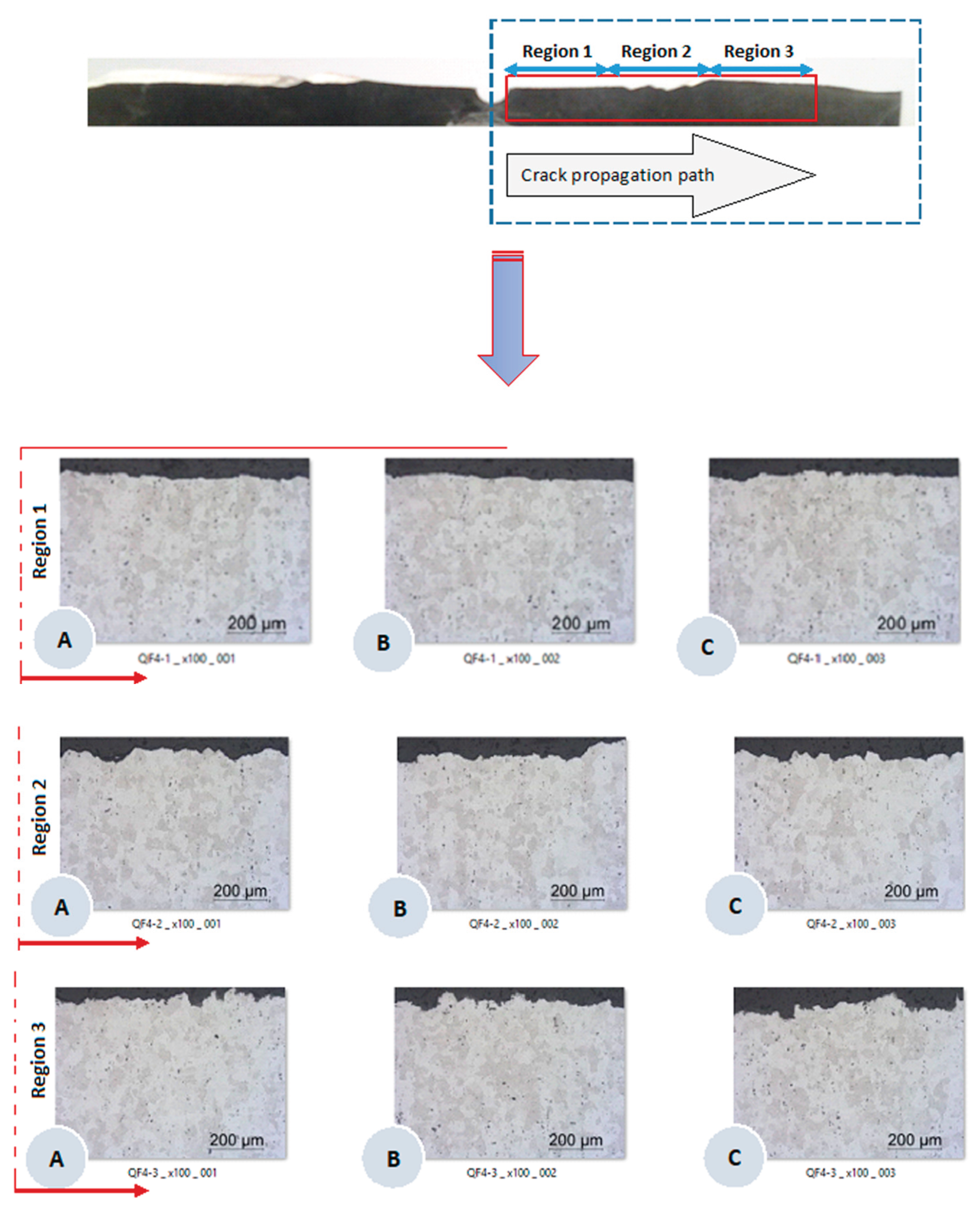

3.2. Microstructural Analysis

Analysis with optical microscopy revealed that the crack propagation remained transgranular throughout all stages of growth. The fracture surface analysis confirmed transgranular fracture mechanisms, as shown in

Figure 7. The crack propagation consistently occurred perpendicular to the applied loading direction, indicating Mode I crack opening conditions (

Fig. 8).

3.3. Paris Law Parameters

The experimental data fitted well to the Paris equation with the following parameters:

Paris constant: C = 1×10-8 (mm/cycle) (MPa√m)-m

Paris exponent: m = 4.05 ± 0.15

Threshold stress intensity: ΔKth = 3.2 ± 0.3 MPa√m

Correlation coefficient: R2 = 0.96

4. Discussion

The experimental results reveal distinct fatigue crack propagation characteristics in AA7075-T6 that provide critical insights for aerospace damage tolerance assessments. The consistent transgranular fracture mode observed throughout all growth stages indicates that dislocation-based mechanisms dominate the fatigue process, aligning with theoretical frameworks [

14,

15].

The identification of three distinct propagation regions offers practical implications for maintenance protocols. Region 1 exhibits slow, straight-line growth controlled by microstructural resistance, while the transition to Region 2 at 20-25 mm represents a critical threshold where crack trajectory begins to deviate. The accelerated growth in Region 3 beyond 35 mm provides a quantitative criterion for emergency repair assessments, directly supporting enhanced safety protocols in aerospace applications.

The dislocation-based analysis reveals quantified local shielding effects at the crack tip through stress intensity factors

and

(Equation 1). The material constants employed in this analysis are rigorously justified: The Burgers vector b = 2.86 × 10⁻¹⁰ m represents the <110> slip direction in the FCC aluminium matrix, while the shear modulus G = 26.9 GPa accounts for both temperature effects and crystallographic anisotropy in AA7075-T6:

Where and are mode-specific constants (c₁ ≈ 1, c₂ ≈ 0 for Mode I) and σᵢⱼ = components of the stress tensor.

The microstructural crack growth model (Equation 2) incorporates experimentally validated parameters: A = 2.5 × 10⁻⁶ mm

(1-k)/cycle represents the material-specific growth resistance, while the plastic strain exponent l = 2.0 and geometric factor k = 0.6 are consistent with literature values for aluminium alloys under similar loading conditions:

Where

refers to the applied plastic strain range, while A, l and k are material parameters with (k ≤ 1) [

18] and da/dN is the crack growth rate.

The basic form of the well-known Paris-Erdogan formula is applied (eq. 3):

Where C and m are material constants determined experimentally. The effective stress intensity factor

accounts for crack closure effects and can be calculated using (eq. 4):

Where U is the crack closure factor (dimensionless), ΔK is the nominal stress intensity factor range (MPa√m), K

max = K

min + ∆K = ΔK/(1-R) (maximum stress intensity factor), K

min = R·K

max (minimum stress intensity factor), K

op is the crack opening stress intensity factor determined experimentally (MPa√m) based on literature and R=stress ratio= K

min/K

max. The closure factor U is defined as (eq. 5):

With (eq. 6):

for R = 0.1 (in our conditions), typical values are K

op≈0.25·K

max (Elber estimation), yielding U≈0.83, which indicates significant closure effects that must be accounted for in fatigue crack growth predictions.

The experimentally determined parameters C = 1×10⁻⁸ and m = 4.05 align well with literature values for AA7075-T6 (m ≈ 4.0-4.2, C ≈ 10⁻⁸ to 10⁻⁹), validating the experimental approach. The crack growth rate of 0.036 μm/cycle at the threshold ΔK

th = 3.2 MPa√m confirms the material's fatigue resistance characteristics and compares favourably with published data for similar aluminium alloys [

25,

26].

The fatigue crack growth behaviour of AA7075-T6 shows superior performance compared to other 7xxx series alloys. The threshold stress intensity factor (3.2 MPa√m) is approximately 15% higher than AA7050-T7451, indicating better crack initiation resistance. The Paris exponent (m = 4.05) falls within the typical range for aluminium alloys (3.5-4.5), confirming material consistency.

These quantitative results provide essential data for predictive modelling and damage tolerance calculations in aerospace structures. The mechanistic understanding linking microscopic dislocation dynamics with macroscopic crack behaviour addresses critical knowledge gaps for AA7075-T6 applications. The established crack length thresholds (20 mm transition, 35 mm critical acceleration) and validated Paris law constants enable direct integration into existing fatigue analysis codes, supporting improved structural integrity assessments and optimized maintenance scheduling for aerospace components operating under demanding fatigue conditions.

The economic impact of these findings is significant, as the quantified thresholds can reduce unnecessary inspections while maintaining safety margins. For example, components with detected cracks below 20 mm can continue operation under extended inspection intervals, while cracks approaching 35 mm require immediate attention, potentially preventing catastrophic failures and associated costs.

5. Conclusions

The crack growth behaviour of notched AA7075-T6 aluminium alloy was systematically monitored and analysed in relation to fracture mechanics principles. The investigation provided comprehensive understanding of fatigue behaviour in this aerospace-critical material with the following key findings:

Transgranular Fracture Mode: Throughout all crack growth stages, cracks consistently propagated through grain interiors, resulting in transgranular fractures. This mechanism remained constant across all tested specimens (n=3).

Three-Stage Crack Propagation:

Stage I (0-20 mm): Slow, steady progression (0.036 μm/cycle) along a straight path

Stage II (20-35 mm): Transitional behaviour with 45° zigzag pattern development

Stage III (>35 mm): Rapid acceleration leading to final fracture

Validated Paris Parameters: Experimentally determined constants (C = 1×10⁻⁸, m = 4.05) align well with literature values, confirming material consistency and enabling predictive modelling applications.

Critical Thresholds: Quantified crack length thresholds (20 mm transition, 35 mm critical acceleration) provide practical criteria for damage tolerance assessments and maintenance decision-making.

The findings indicate that while early crack propagation remains controlled and stable, significant acceleration occurs as cracks approach critical dimensions. This accelerated growth is attributed to reduced structural rigidity and increased stress concentration around the crack tip. The study highlights the importance of understanding these transition phases to improve predictions of material performance and enhance design strategies for components subjected to cyclic loading.

These results directly support enhanced structural health monitoring protocols, risk-based inspection strategies, and emergency repair decision frameworks for aerospace applications utilizing AA7075-T6 components.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) with funding from South Africa's Department of Science and Innovation (DSI). We also acknowledge the grant under the National Exceptional Program (PNE) from the Algerian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, as well as the Directorate General of Scientific Research and Technological Development. We extend our thanks to Dr. Kevin Slattery and Selina Cobbs at Boeing, as well as Dr. Leonard Mac Adams at Cytec/Solvay Group-USA, for their assistance with acquiring materials. Our gratitude goes to Pierre Rossouw for logistical management and technical support; Danie Wilkins, Martin Williams, and Marius Grobler for their help with sample preparation; Chris McDuling for his support with mechanical testing.

Conflicts of Interest

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Avram, J.B. Fatigue Response of Thin Stiffened Aluminum Cracked Panels Repaired with Bonded Composite Patches. Master's Thesis, Air Force Institute of Technology, Air University, Dayton, OH, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, K. Fatigue Crack Propagation. In Comprehensive Structural Integrity; Milne, I., Ritchie, R.O., Karihaloo, B., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2003; Volume 4, pp. 95–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khelil, F.; Aour, B.; Belhouari, M.; Benseddiq, N. Modeling of Fatigue Crack Propagation in Aluminum Alloys Using an Energy Based Approach. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2013, 3, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouambi, L.; Khodja, M.; Wahid, O.; Fekirini, H.; Moller, H.; Bouiadjra, B.B. J-Integral Evaluation of Repaired Cracks in AA7075-T6 Structures Subjected to Uniaxial Tensile Stresses. Polym. Test. 2019, 77, 105923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodja, M.; Fekirini, H.; Govender, G.; Bouiadjra, B.B. Effect of Curing Cycle on Fatigue Life of Cracked AA7075 T6 Aircraft Sheet Repaired with a Boron/Epoxy Composite Patch. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Mech. Eng. 2022, 46, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, A.A. Phenomena of rupture and flow in solids. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A 1921, 221, 163–198. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0264-3952%281921%29221%3C163%3ATPORAF%3E2.0.CO%3B2-J.

- Miller, K.J. Materials science perspective of metal fatigue resistance. Mater. Sci. Technol. 1993, 9, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.C.; Li, S.X.; Wang, Z.G.; Zhang, F. Relations between fatigue strength and other mechanical properties of metallic materials. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2014, 37, 958–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokluda, J.; Šandera, P. Micromechanisms of Fracture and Fatigue; Springer-Verlag: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öksüz, K.E.; Bağırov, H.; Şimşir, M.; Karpuzoğlu, C.; Özbölük, A.; Yusuf. Investigation of Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of AA2024 and AA7075. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 390, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, M.; Sokoluk, M.; Cao, C.; Yuan, J.; Zheng, S.; Li, X. Microstructure Control and Performance Evolution of Aluminum Alloy 7075 by Nano-Treating. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Liu, S.; Wang, P.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Al-dakheel, F. Effect of grain structure on fatigue crack propagation behavior of 2024 aluminum alloy under different stress ratios. Mater. Des. 2024, 244, 113117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, E.; Bouchonneau, N.; Alves, E.; Alves, K.; Araújo Filho, O.; Mesguich, D.; Chevallier, G.; Laurent, C.; Estournès, C. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of AA7075 Aluminum Alloy Fabricated by Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS). Materials 2021, 14, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.S.A.; Rajneesh, H.; Madhu, H.C. Effect of SiC nano particles on grain stability of friction stir processed AA7075. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 27, 2586–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, A.H. Dislocations and Plastic Flow in Crystals; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Weertman, J. Dislocation Based Fracture Mechanics; World Scientific: Singapore, 2008; ISBN-10 981-02-2620-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hills, D.A.; Kelly, P.A.; Dai, D.N.; Korsunsky, A.M. Solution of Crack Problems: The Distributed Dislocation Technique; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1996; ISBN 0-7923-3848-0. [Google Scholar]

- Riemelmoser, F.O.; Pippan, R.; Stüwe, H.P. An argument for a cycle by cycle propagation of fatigue cracks at small stress intensity ranges. Acta Mater. 1998, 46, 1793–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, P.C.; Gomez, M.P.; Anderson, W.E. A Rational Analytic Theory in Engineering. The Trend Eng. 1961, 13, 9–14. https://fr.scribd.com/document/470761799/Paris-Gomez-Anderson1961-A-RationalAnalyticTheory-of-Fatigue-pdf.

- Neto, D.M.; Pedro, J.; Borges, M.F.; Borrego, L.F.P.; Sérgio, E.R.; Antunes, F.V. Numerical prediction of fatigue crack growth based on cumulative plastic strain versus experimental results for AA6082-T6. Int. J. Fract. 2023, 240, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behboodi, S.; Bitaraf, M.; Nafisifard, M. Prevention of low-cycle fatigue damage using adaptive control approach and magnetorheological dampers. Structures 2021, 33, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.A.; Jones, R. Bonded Repair of Aircraft Structures. In Composite Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988; Chapter 6, Section 7. [Google Scholar]

-

ASTM E647-15e1; Standard Test Method for Measurement of Fatigue Crack Growth Rates. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- Newman, J.C. A crack opening stress equation for fatigue crack growth. Int. J. Fract. 1984, 24, R131–R135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, R.G.; Kearney, V.E.; Engle, R.M. Numerical analysis of crack propagation in cyclic-loaded structures. J. Basic Eng. 1967, 89, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, R.G.; Kearney, V.E.; Engle, R.M. Numerical analysis of crack propagation in cyclic-loaded structures. J. Basic Eng. 1967, 89, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).