1. Introduction

The thermal perception of textiles against the human skin plays a crucial role in determining consumer preference and their comfort, particularly during the initial contact of human skin with a fabric [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This tactile thermal interaction—often referred to as the haptic perception of temperature—is governed by the transient heat transfer between two heterogeneous materials: human skin and textile [

2,

5].

The sensation experienced during this short-term contact, often within the first few seconds, forms the foundation of a consumer’s first impression of a textile product [

4]. In many purchasing contexts, particularly where touch is involved (such as apparel or bedding), the way a fabric feels—cool, warm, dry, or damp—can influence the decision to buy or not to buy [

3,

4]. Studies show that thermal comfort is one of the most important predictors of textile acceptability, also in sportswear and everyday clothing, where both psychological and physiological responses to temperature are relevant [

3,

6,

7]. This perception-related dimension encompasses thermal, tactile, and even emotional elements [

21,

22], reflecting an individual’s response to how a fabric interacts with their body [

4].

Fabrics’ thermal features can be measured objectively using instruments such as Kawabata Evaluation System KES F7 Thermo Labo [

47] and subjectively using Fabric Hand Subjective Evaluation procedure [

20]. In case of empirical studies, placing a thermocouple directly between fabric and skin allows for monitoring how temperature changes when a human fingertip, usually at a temperature around 31 °C [

17] comes into contact with a cooler textile (measured in standard laboratory temperature conditions are 21°C) [

2,

17]. This measurable transient thermal profile provides insights into how heat is transferred between the two materials and, by extension, how “cool” or “warm” the fabric may feel against the skin [

17,

20,

22].

Accurate thermal skin-fabric interface models can serve as a bridge between subjective human sensations and objective physical measurements, enabling the quantification of how human skin may thermally perceive fabrics [

25]. This quantification is vital for predicting and enhancing the thermal comfort of textiles, ensuring that they meet the physiological needs of users. Incorporating thermal modelling into textile design allows engineers to predict a fabric's thermal behaviour before its production [

25,

26]. On the fabric’s materials and construction level, factors such as raw materials, spinning technology of yarns, yarn density, yarns’ arrangement, chemical and mechanical finishes collectively impact fabrics’ thermal characteristics. Collectively, it encompasses the following physical parameters of fabrics: (a) thermal diffusivity (indicates how quickly fabric transfers heat; higher values = cooler sensation); [

30] (b) thermal resistance (measures insulation or resistance to heat flow; higher values = warmer fabric) [

31,

32]; (c) heat flux or maximum heat flux (Qmax) (indicates initial cool/warm feeling upon skin contact; higher Qmax = cooler touch) [

33]; (d) thermal absorptivity (correlates with warm/cool sensation at first touch; lower value = warmer sensation) [

34,

35]; (e) heat transfer coefficient (total rate of heat transfer through the fabric; it is used in comparative thermal studies and modelling) [

36]; (f) specific heat capacity (measures heat required to raise temperature of fabric by 1°C, which is important in performance/technical textiles) [

36,

37]; (g) surface temperature distribution (visual map of heat spread across fabric surface [

23,

24].

In the development of functional textiles, modelling heat and mass transfer properties is crucial for ensuring that garments provide adequate insulation and breathability [

37,

38,

39]. Furthermore, as textiles evolve into smart and functional materials, understanding heat transfer mechanisms becomes increasingly important. Advanced thermoregulatory textiles, designed to manipulate heat transport, storage, rely on precise thermal models to function effectively, drifting towards personal thermal management, which is a holistic approach to offering thermal comfort to humans wearing clothing [

37,

41,

42]. These models inform the development of fibres and fabrics that can adapt to environmental conditions, providing personalized thermal management without the need for external energy sources. By accurately modelling heat transfer dynamics, prior to the mass production of clothing, especially during the initial contact between fabric and skin, manufacturers can optimize the first impression of textiles. It would lead to improved marketability and user experience [

37,

38,

42,

43]. However, mathematical modelling of this thermal behaviour, without mass transportation, encompasses both the human skin and textiles, and is not straightforward. Traditional approaches based on classical Fourier heat conduction theory assume that heat propagates with infinite speed and follows a predictable square-root time dependency (T ∝ √t), at least for short times. However, during the first seconds after contact, the coupled skin–textile system consists of at least two heterogeneous media (skin tissue with blood perfusion, and textile fibers with entrapped air), which often causes deviations from the √t prediction.

While this may be suitable for homogeneous solids observed in longer periods of time, it is insufficient for porous, dual-phase materials like textiles or biological systems such as skin, particularly during short-time transients [

8,

9].

To overcome these limitations, researchers have turned to the Dual Phase Lag (DPL) [

44,

45] approach, which incorporates two independent time delays:

- (a).

τ

q, the lag of heat flux in response to a temperature gradient [

44], and

- (b).

τ

T, the lag of the temperature gradient in response to a heat flux [

10].

This model is suitable for materials like woven or knitted fabrics that exhibit both solid (fibres) and pores (air) phases, as well as for biological materials like human skin, where tissue and blood flow create internal thermal lags [

2,

10,

11]. These systems often display anomalous conduction behaviour where the temperature follows a power-law dependency T ∝ t

α, with α ≠ 0.5—highlighting the inadequacy of classical models for short-duration events.

The goal of this study is to: (a) apply the dual-phase approach to model the results and extract meaningful parameters in the initial short period of contact (0-20 s); (b) experimentally capture the short-time temperature profiles using a precise thermocouple setup; (c) analyse differences across a variety of textile structures.

Through this investigation, the study aims to build a bridge between objective thermal measurements and subjective comfort perception, offering a tool for the design of thermal characteristics of textiles, including high-performance materials, wearables, and next-generation smart materials.

2. Theoretical Approach

To establish a baseline, one considers the classical heat conduction in a semi-infinite solid subjected to a constant heat flux step at the free surface. The boundary condition for a constant heat flux per unit area applied at

x = 0 is:

where

u(t) is the unit step function and

p0 is the applied heat flux amplitude.

This can be expressed in terms of the standard semi-infinite solution [

13,

14]:

where

a = k/cv is the thermal diffusivity,

k is the thermal conductivity,

cv is the specific heat capacity, and

p0 is the power per unit area applied at the free surface. The result (2) shows the well-known square-root dependence on time,

T∝ √t predicted by classical Fourier heat conduction. One will find

cv = ϱ cp, where ϱ is the density and

cp the specific heat capacity per unit mass. The relation

T ∝ √t is also valid for bodies with different geometries, but only for sufficiently short periods. The relation (2) is also used in specialised equipment to measure the product

kcv of solid materials.

If a heat pulse is used as the heat source, the temperature behaviour turns out to be:

(3) can be easily found by taking the time derivative of (2). The reason for the widespread use of the

√t relationship is that it is an exact analytical solution for a half-infinite medium. The time-dependent heat transfer equation in the one-dimensional case reads:

The fundamental solution of (4) is in the form:

(4) is known as the diffusion equation. (5) is the solution for a single heat pulse in space and time: i.e., in the origin

x = y = z = 0 and

t=0. (5) is known as the fundamental solution or the Green’s function of (4). In the origin (x=0), a temperature decay of the form

T∝ 1/√t is found. If a power step is applied instead of a pulse, integrating

T∝ 1/√t response with respect to time yields

T∝ √t.

As a consequence, the √t has been considered as a fundamental law. Any time a √t behaviour is observed, the conclusion is that one is dealing with a time-dependent heat conduction problem or, more generally, with a diffusion phenomenon.

Over the last two decades, several experimental studies have concluded that the

√t behaviour no longer has its universal value. Instead, a

tα relationship was measured where

α≠1/2. These experimental observations were mainly found in porous and amorphous materials. In porous materials, two phases are involved, and the heat transfer equation (6) has to be adequately modified to reflect the dual-phase phenomenon. Experiments have been done in sand [

10] and, assembly of small (100 µm diameter) copper spheres [

15].

In other studies [

15,

16], mathematical analysis is based on fractal geometry of the percolation network, i.e., how the heat-conducting paths in the material are connected. A

tα relation could be proved where

α depends on the fractal dimension of the structure. An overview of these topics – especially, macroscale heat transfer- was provided by Tzou [

10]. These macroscale phenomena are only observed for sufficiently short periods, and after longer periods, all materials follow the

√t, indicating that the classical heat transfer equation can be used for modelling.

Any textile woven fabric is considered a porous, non-homogeneous object. Not only the empty spaces in between the yarns, but also the yarns being composed of many fibres create spaces filled with air, hence the dual phase approach (textiles and air). A fingertip is also a dual-phase material due to different properties of the tissues composing the fingertip, such as epidermis, dermis, hypodermis (solid), and blood (liquid).

The initial experimental approach presenting the transient temperature between a fingertip and a fabric was published previously [

17]. The goal of this research was to learn how textiles feel when they are in contact with the human body. These kinds of feelings are very subjective and difficult to quantify. Therefore, one has chosen to measure the temperature variation at the interface between a textile fabric and a human finger. A temperature can be measured with sufficient accuracy, and this contact temperature can also be associated with the feeling (perception) of a piece of textile. After touching a fabric for too long, the initial sensation dissipates. Therefore, transient temperature measurements have been done.

In the present paper, the short-time measurements (0 < t < 20s) are studied.

3. Experimental Results

The experimental data for the modelling and analysis were obtained from the previous research [

17]. In that research, a fabric was put on a piece of foam (thickness 2cm) to provide sufficient thermal insulation. Also, in that initial research, only three types of fabrics were tested ((∆) knit 100% angora; (○) woven 65% linen + 35% cotton; woven 70% wool + 20 % linen + 10 % cotton). The data from the short-time transient thermal behaviour measured for these three fabrics were used in the current study. In addition, the short-time transient thermal behaviour for five other fabrics was examined, and the collected data served the modelling in this current research.

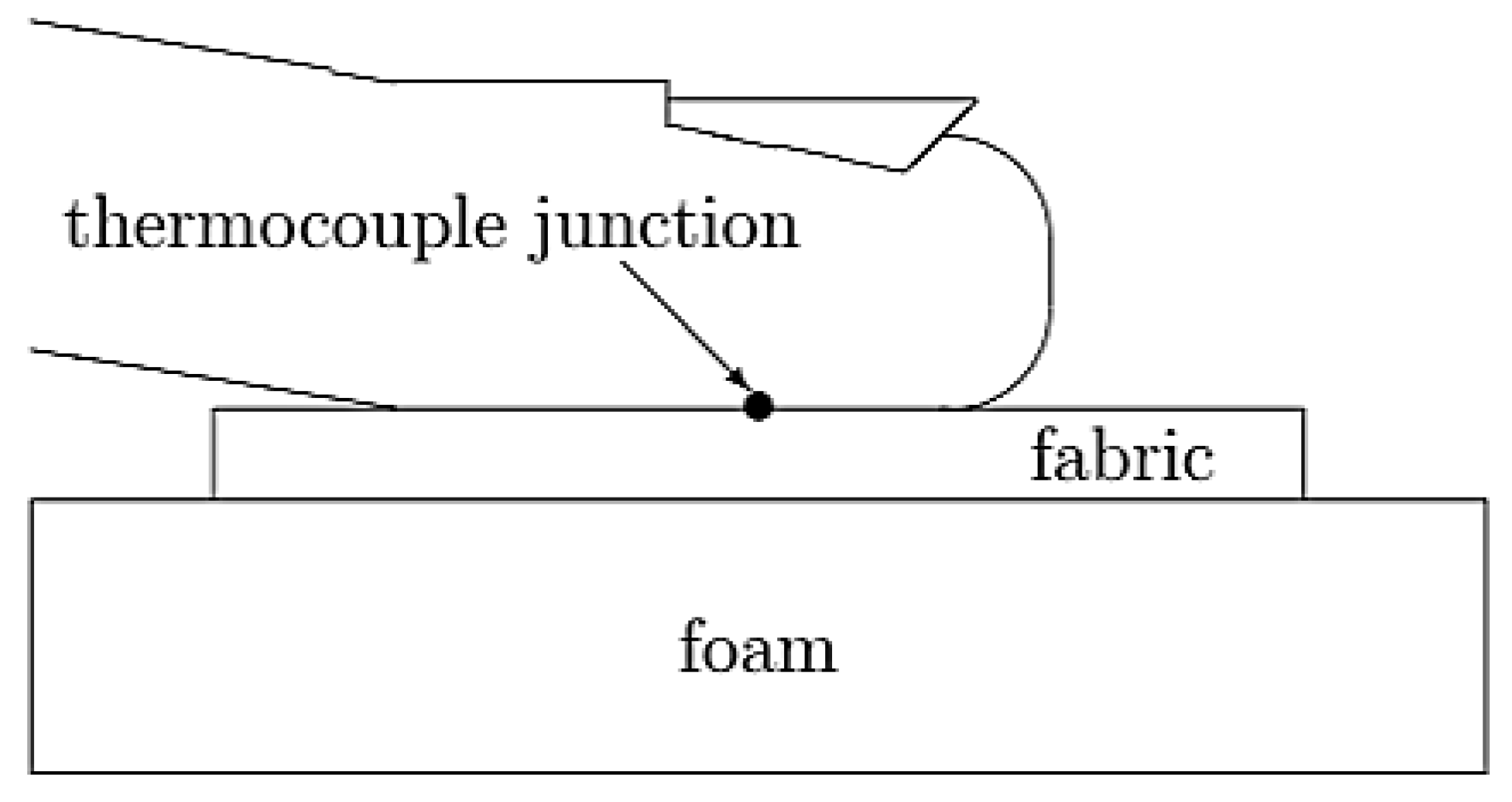

Figure 1 shows an experimental setup with a right-hand index fingertip of a 35-year-old female placed on a thermocouple connected with the voltmeter that registers online changes of the temperature of the interface between a fabric placed on an isolating foam and a fingertip. A thin nickel-chromium thermocouple was put on the fabric to record the temperature variation. This thermocouple generates a voltage of 36.8 µV/°C. Next, the finger was placed on the thermocouple in such a way that the thermocouple junction was just in the middle of the fingertip. The thermocouple junction was a small sphere with a diameter of 0.5 mm. Hence, it can be assumed that its size will not disturb the measurements. Once the finger made contact with the fabric, the temperature was recorded with an electronic voltage meter with a high input impedance of 10 MΩ. The temperature readout was done every second. The starting time t=0 was exactly the moment the finger made contact with the fabric.

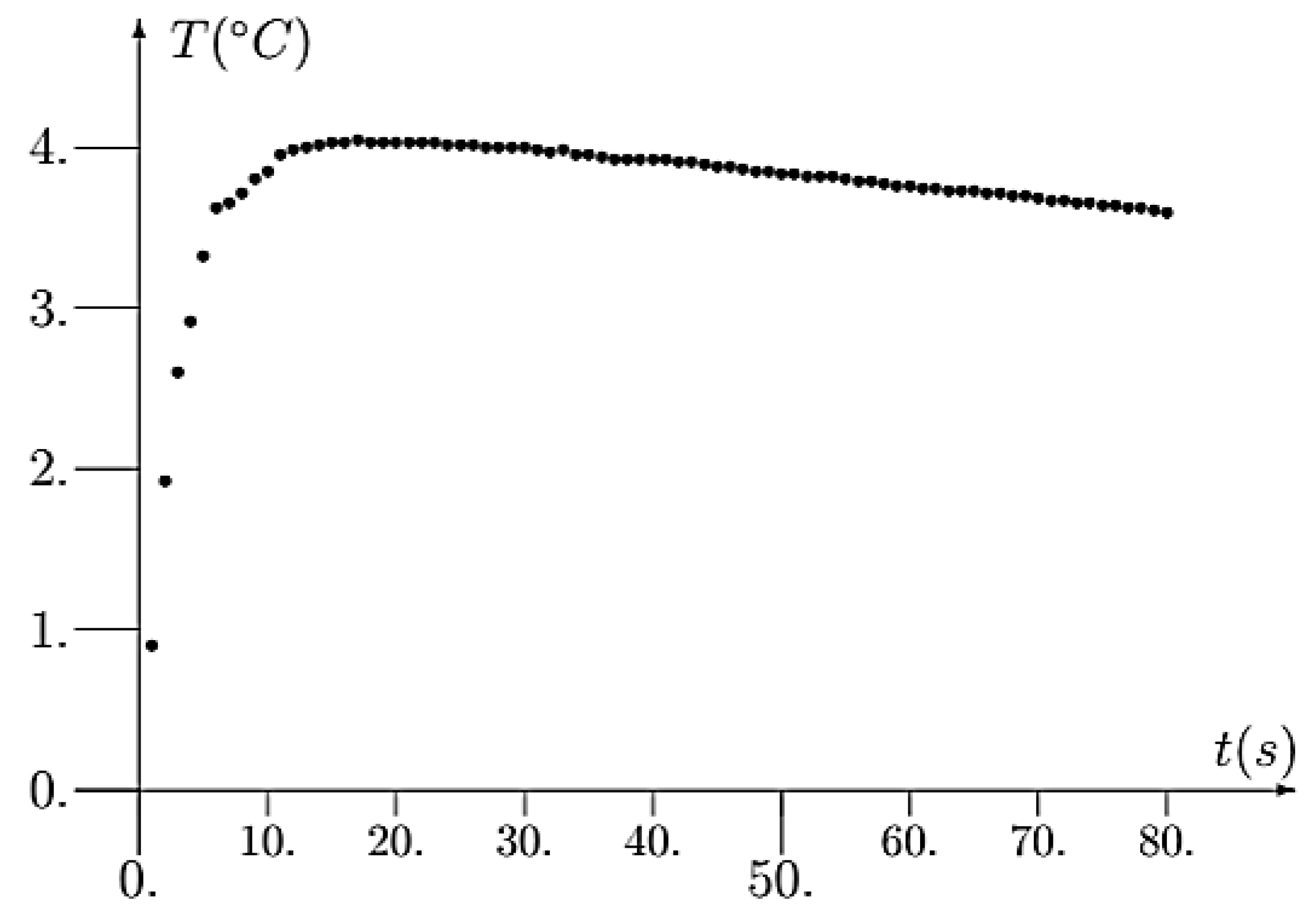

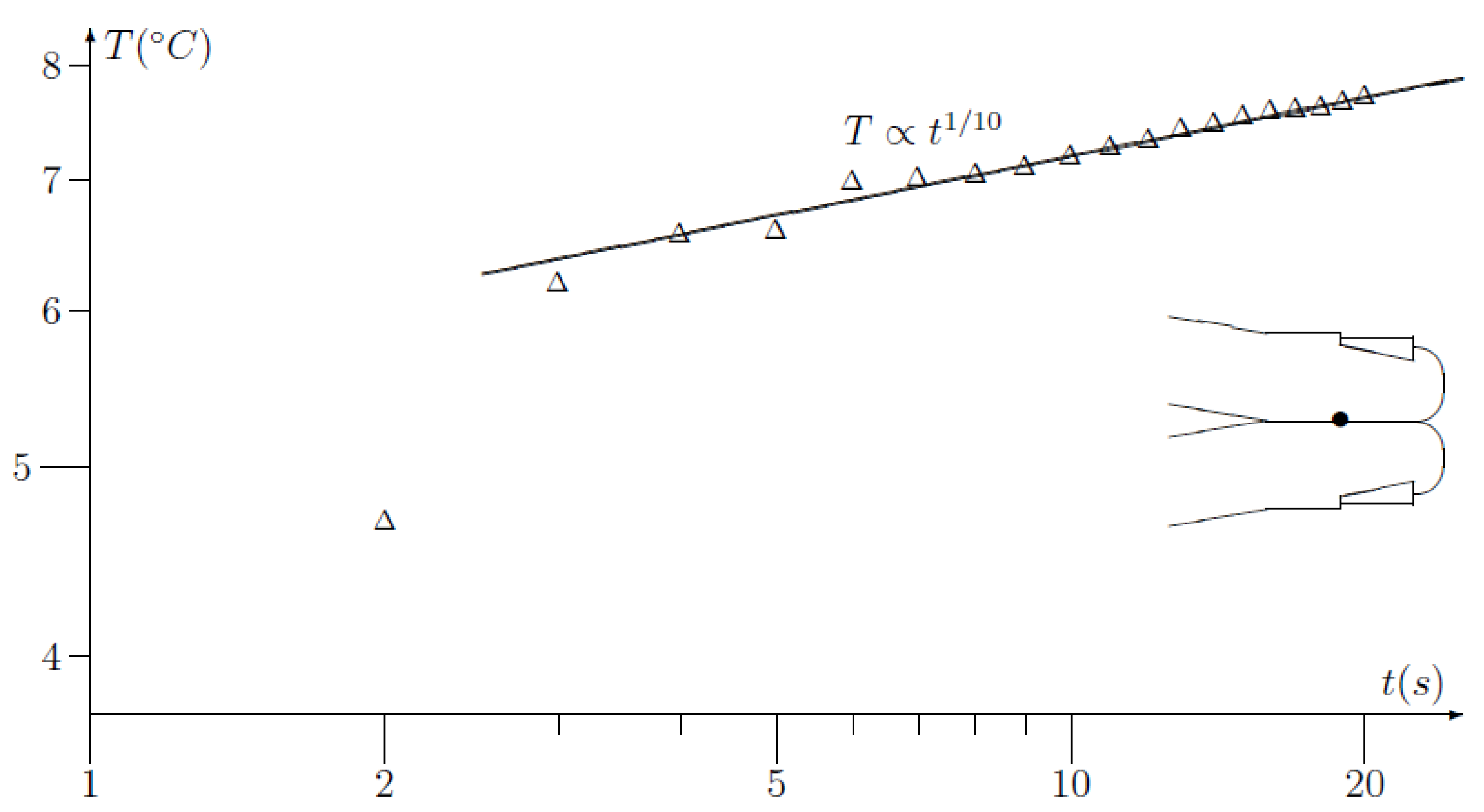

Figure 2 presents a typical, theoretical temperature plot versus time when a fingertip is in contact with a piece of fabric, as presented in

Figure 1. The temperature rises to about 15 s – 20 s followed by a continuous decrease.

Note that the temperature rises until t ≈ 15 s, then decreases continuously. The decrease occurs because, after about 15 s, a large portion of the fingertip’s heat capacity has been used, causing the fingertip’s temperature to drop, as shown in

Figure 2. However, in our experiments, we are focusing on the short-time behaviour, i.e.,

t<15 s.

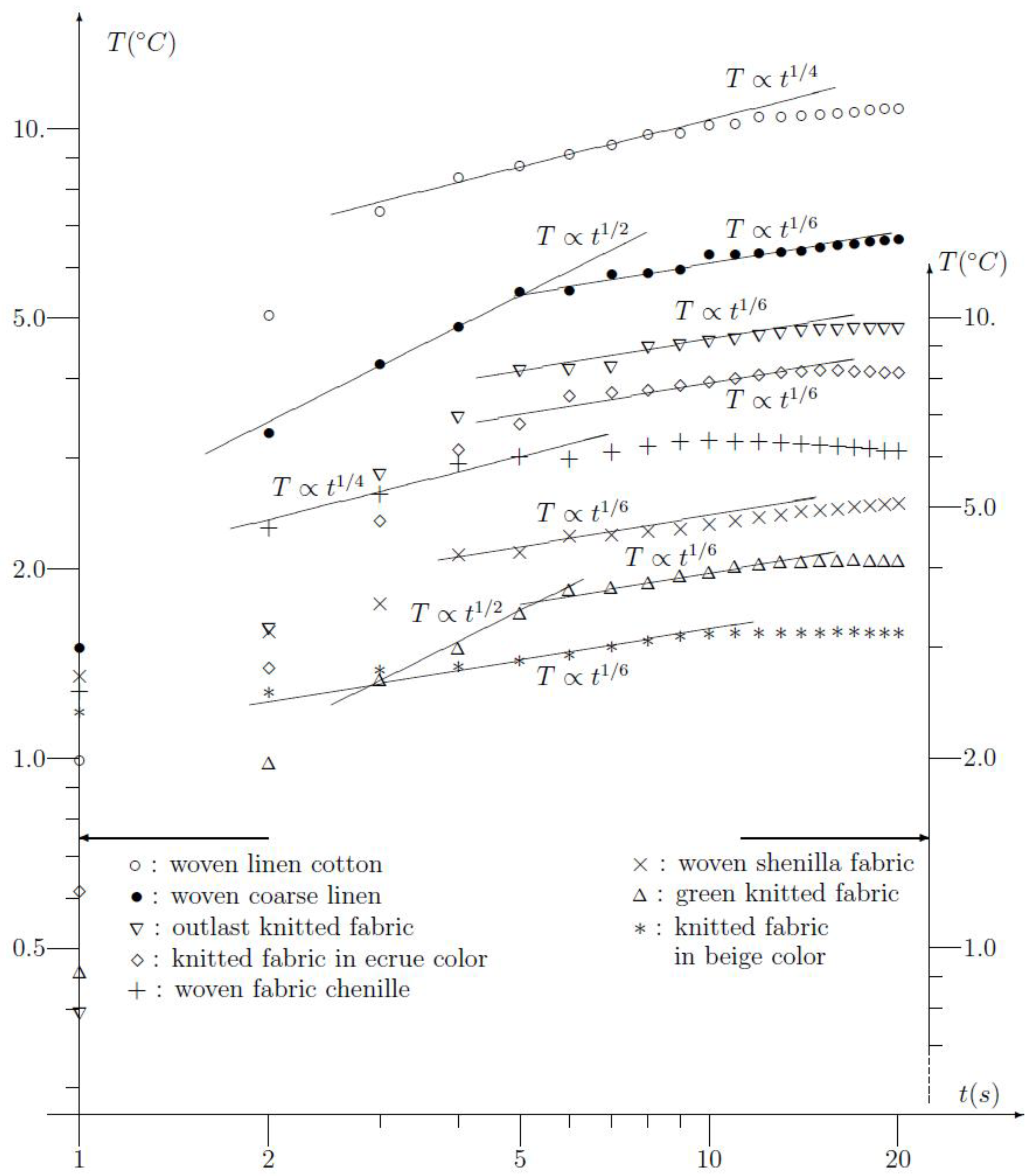

Eight different woven and knit fabrics have been used in the experiment: woven 65% linen and 35% cotton fabric (○), woven coarse linen (●), woven chenille fabric thin polyester(×), Outlast® chenille fabric polyester (), 100% angora knitted fabric (∆), plain knitted fabric polyester in ecru colour (◊), plain knitted fabric cotton in beige colour (⁕), and woven fabric chenille thick (+). The only criterion for fabric selection was their thickness, which was in the range from 0.75 mm ((◊), (∆), (⁕), through 0.90 mm ((○), ()), to 1.25 mm (●), (+), (×)).

The measurements were performed for each fabric separately. The results of the measurements are presented in

Figure 3. The character of the curves in

Figure 3 resembles the curve from

Figure 2.

To detect any kind of DPL, it is mandatory to present all results in a double logarithmic plot, as presented in

Figure 3.

The first observations are the remarkable differences between the different fabrics. Temperatures vary between 2°C and 10°C. A second observation is that fittings can be made of the shape tα. Most frequently, t1/6 is observed. Note that all values of the exponent α can be explained using the dual phase model, which will be explained further on in this paper.

Two curves can be fitted to t

1/2 in the very beginning, followed by t

1/6 for larger values of time (woven coarse linen and green knitted fabric). This behaviour is also observed experimentally in several other cases [

10]. First, a diffusion t

1/2 followed by a dual phase transient, and then once again, a diffusion is observed and described in the literature.

3. Mathematical Analysis – The Dual Phase Lag (DPL) Model

To provide a theoretical explanation for the observed phenomena, one proposes applying the DPL model, which offers a physically grounded explanation. In many textbooks dealing with heat transfer, one finds the Fourier law (the one-dimensional case):

where

q denotes the heat flux and

T the temperature distribution. Conservation of energy is expressed by:

where

cv is the specific heat capacity. The combination of (6) and (7) yields:

(8) is known as the diffusion equation. As pointed out, the diffusion equation can explain the exponent ½, but not the other values observed experimentally.

In the dual phase approach, the Fourier law (6) is replaced by:

The equation (7), expressing the conservation of energy, remains unchanged:

Note that two delay times τ

q and τ

T have been inserted in (9). Using a Taylor series expansion, (7) is replaced by:

And (11) is converted to:

which gives rise to the following equation for the temperature distribution after inserting (10):

The above equation has to be solved with the boundary condition:

where

u(t) denotes the unit step function.

Next, equation (13) is to convert the time-dependent terms to the Laplace domain:

or:

where

s is the Laplace variable. The boundary condition (14) in the Laplace domain is:

Finally, the solution is given by:

and with boundary

x=0 one receives:

The relevant literature notes that the analytical inversion of equation (19) into the time domain is not possible.

However, such an inversion is not necessary. The theory can be verified entirely within the Laplace domain, which will largely simplify the mathematical analysis. To explain the slope (

−1/6) observed in

Figure 3, it is sufficient to consider the following Laplace transform.

where: Γ is the Euler Gamma function. Note that Γ

(7/6) = 0.928. It will be sufficient to make a plot of the following function:

Where:

Z = τT / τq appears to be the dominating parameter according to Tzou [

10]. For very small values of

s (or

t→∞) and also for

s being very large (or

t→0), the function (21) can be approximated by

1/s3/2, which corresponds to

√t in the time domain.

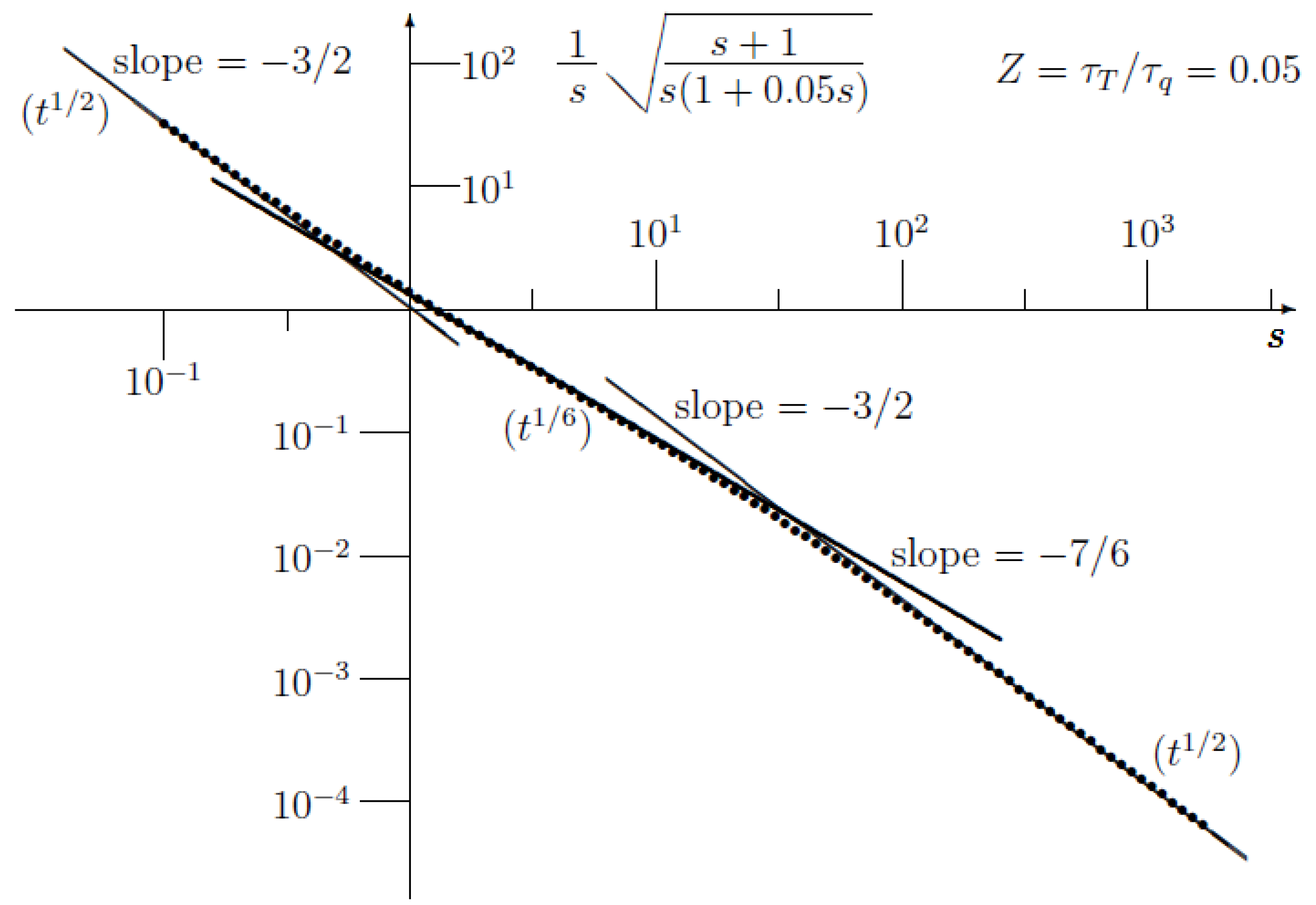

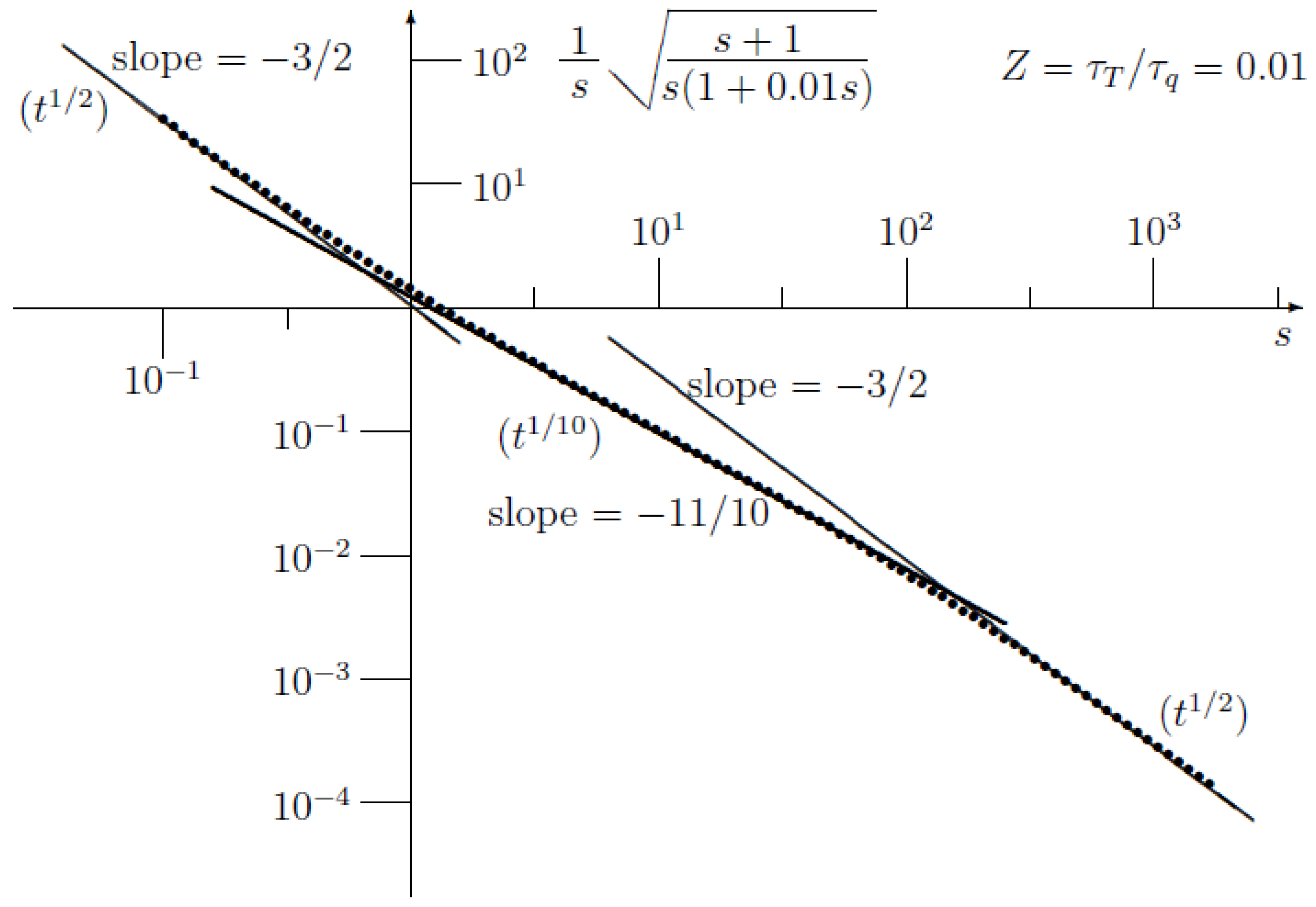

Figure 4 shows a plot of the function (19) for the value Z = τ

T / τ

q = 0.05. A double logarithmic plot was used for clarity. It turns out that in the interval

1 < s < 10, the plot can be very well fitted to a slope

-7/6 or

t1/6 in the time domain. It has been shown that the experimental results can be well explained using the dual-phase model for conduction heat transfer.

Other slopes can be explained similarly.

For high and low values of

s—corresponding, respectively, to low and high values of time

t—the plot in

Figure 4 exhibits a slope of −3/2, which is characteristic of a diffusion process proportional to

√t. Experimentally, the

√t behaviour was not observed at short times, as measurements commenced at 1 s. For a purely diffusive process, the penetration depth

d can be estimated using the following empirical relationship [

18]:

Using typical data for textile fabrics: k = 0.1 W/mK and cv =2 MJ/m3 K, one obtains after t = 10s that d = 1.4mm, smaller than the thickness of the fabric. In other words, the heat did not reach the back side of the fabric. In other words, the thicknesses of the fabrics, all more than 2mm, is not relevant to explain the experiments.

4. Two fingertips Making Contact

While the presented experiment and the theoretical approach (modelling) focus on two different materials: fingertip and textile fabrics, a thermal contact behaviour between two fingertips was examined as a reference for this study.

Figure 3 demonstrates that the type of fabric influences the transient temperature behaviour. To assess whether the experiments might have been significantly affected by fingertip contact, the same experiment was repeated using two fingertips in contact with a thermocouple junction. The results, presented in

Figure 5, show that the experimental data in this case could be fitted to

t1/10. Notably, the exponent 1/10 is smaller than all exponent values observed in

Figure 3. This suggests that the influence of the fingertip is less significant than that of the fabric itself.

For the sake of completeness, a similar analysis as before has been carried out with the results shown in

Figure 5. First, one needs to evaluate the Laplace transform of

t1/10:

Figure 6 shows a plot of the function (24) for a value

Z =

τT / τq = 0.01. It turns out that in the interval 0.5 < log(s) < 1.5, the plot can be very well fitted to a slope -11/10

, which is equivalent to a function

t1/10 in the time domain. At the same time, it has been proven that human tissues can be modelled using the dual-phase model.

This statement holds for the short-time measurements. For larger values of the time, the classical diffusion theory can still be applied.

4. Discussion

The present findings align with our earlier work on the subjective and objective assessment of thermal haptic perception of textiles [

17], in which knitted wool fabrics with higher contact thermal resistance and lower initial heat flux were consistently rated as “warm” or “very warm” by a human subjects, whereas smoother linen–cotton fabrics with higher initial heat flux were perceived as “neutral” to “cool.” In the current study, fabrics exhibiting smaller DPL exponents (α ≈ 1/6) demonstrated slower initial heat transfer, corresponding to the “warm” category in the previously published subjective assessments of selected fabrics. Conversely, fabrics with larger α values, indicating faster heat transfer to the textile, correlate with the “cooler” sensations previously reported. This consistency across independent experimental approaches supports the hypothesis that early-time transient temperature behaviour—quantified here through DPL analysis—can serve as a predictive indicator of perceived thermal comfort.

The slope values obtained from the DPL fits (t1/6, t1/4, t1/10) can be interpreted as indicators of how quickly heat travels through the combined skin–fabric system. Smaller exponents, such as t1/6, correspond to slower initial heat transfer, which occurs when the contact thermal resistance is high due to greater air content in the fabric structure or a more discontinuous fibre–skin contact. In physical terms, the heat pathways are more tortuous and the solid–solid contact area is reduced, limiting the rate at which thermal energy leaves the fingertip. Fabrics with such behaviour typically correspond to “warm” sensations, as confirmed in our earlier study on subjective thermal haptic perception, where knitted wool fabrics with lower initial heat flux were rated as warm or very warm. Larger exponents, approaching t1/2, indicate faster initial heat transfer through more continuous conductive pathways in smoother, denser fabrics, which draw heat away from the skin rapidly and produce a cooler sensation. This correspondence between measured short-time transient behaviour and reported warm–cool feeling suggests that the DPL parameters can be used as quantitative predictors of thermal comfort perception.

5. Conclusions

A short-time temperature measurements (0–20 s) between the fingertip’s skin and a fabric interface showed significant deviations from the classical √t transient predicted by Fourier’s law, confirming that standard diffusion models are insufficient for modelling the contact of textiles with human skin.

The DPL model successfully captured the observed phenomenon, with fitted exponents ranging from t1/6 to t1/4 for fabrics and t1/10 for fingertip–fingertip contact, which reflects the combined effects of fibre/yarn/fabric/ and air trapped in textile structures and heterogeneity of the fingertip (skin tissue, fat, bones, and the blood).

The Laplace domain approach allowed straightforward slope analysis without complex time-domain inversions, making it a practical tool for experimental–theoretical comparison.

The findings provide a quantitative basis for linking physical measurements to subjective thermal perception, enabling the design of textiles with tailored warm–cool sensations for applications from apparel to technical wear.

.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.D.; methodology, G.D., I.C.W.; validation, M.S., B.W., G.D.; formal analysis, M.S., B.W., G.D., I.C.W.; investigation, C.H., L.V.L.; data curation, G.D.; writing—original draft preparation, G.D., I.C.W.; writing—review and editing, G.D., I.C.W.; visualization, G.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data in Excel sheet is available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following parameters, their abbreviations, and typical units of these parameters are used in this manuscript:

| q |

Heat flux [W·m⁻²] |

| T |

Temperature [K or °C]; experimental temperatures are reported in degrees Celsius (°C), but theoretical equations use Kelvin (K) for absolute values. |

| k |

Thermal conductivity [W·m⁻¹·K⁻¹] |

| cv |

Volumetric heat capacity [J·m⁻³·K⁻¹] |

| ρ |

Density [kg·m⁻³] |

| cp |

Specific heat capacity at constant pressure [J·kg⁻¹·K⁻¹] |

| a |

Thermal diffusivity, a = k / cv [m²·s⁻¹] |

| τq

|

Phase lag of the heat flux [s] |

| τT

|

Phase lag of the temperature gradient [s] |

| Z |

Dimensionless ratio of phase lags, Z = τT / τq [–] |

| p₀ |

Applied heat flux amplitude [W·m⁻²] |

| u(t) |

Unit step function [–] |

| δ(t) |

Thermal penetration depth [m] |

| s |

Laplace variable [s⁻¹] |

References

- Wilfling, J., Havenith, G., Raccuglia, M., & Hodder, S. (2022). Consumer expectations and perception of clothing comfort in sports and exercise garments. Research Journal of Textile and Apparel, 26(4), 293–309. [CrossRef]

- Ciesielska-Wróbel, I. L., & Van Langenhove, L. (2012). The hand of textiles – definitions, achievements, perspectives – a review. Textile Research Journal, 82(14), 1457–1468. [CrossRef]

- Kamalha, E., Zeng, Y., Mwasiagi, J. I., & Kyatuheire, S. (2013). The comfort dimension: A review of perception in clothing. Journal of Sensory Studies, 28(6), 423–444. [CrossRef]

- De Mey, G., Ciesielska-Wróbel, I., & Van Langenhove, L. (2016). Mathematical model of haptic perception of temperature. Textile Research Journal, 87(2), 155–164. [CrossRef]

- Ho, H. N., & Jones, L. A. (2008). Modeling the thermal responses of the skin surface during hand-object interactions. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering, 130(2), 021005. [CrossRef]

- Mukae, H., & Watanabe, T. (2016). Psychophysical relations between fabric physical properties and psychological touch perceptions. Journal of Sensory Studies, 31(6), 489–500. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y., Wang, X., Liu, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2024). Modeling the relationship between fabric textures and evoked emotions: The role of sensory perception via vision and touch. i-Perception, 15(1), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Bejan, A. (1993). Heat transfer. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Cengel, Y. A. (2003). Heat transfer: A practical approach (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Tzou, D. Y. (1996). Macro- to microscale heat transfer: The lagging behavior. Taylor & Francis, London, 1996.

- Zhou, J. (2009). Macroscale and nanoscale heat transfer: Fundamentals and engineering applications. Wiley.

- Jay O. and G. Havenith G. (2004). Finger skin cooling on contact with cold materials: an investigation of male and female responses during short-term exposures with a view on hand and finger size. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 93, 1-8.

- Incropera F. and De Witt DP. Introduction to heat transfer. Wiley, 1985, 202-206.

- Bayazitoglu Y. and Ozisik MN. Elements of heat transfer. Mc Graw Hill, 1988, 140-148.

- Fournier D. and Boccara AC. (1989). Heterogenous media and rough surfaces: a fractal approach for heat diffusion studies. Physica (A), 157, 587-592.

- Goldman CH., Norris PM. and Tien CI. (1995). Picosecond energy transport by fractons in amorphous materials. National Heat Transfer conference, Portland, Oregon.

- Ciesielska-Wróbel, I., De Mey, G., & Van Langenhove, L. (2016). Dry heat transfer from the skin surface into textiles: subjective and objective measurement of thermal haptic perception of textiles - preliminary studies. Journal of the Textile Institute, 107(4), 445-455.

- Chatziathanasiou V;,Chatzipanagiotou P., Papagianopoulos I., De Mey G. & Wiecek B. (2013). Dynamic thermal analysis of underground medium power cables using thermal impedance, time constant distribution and structure function. Applied Thermal Engineering, 60, 256-260.

- Ciesielska-Wrobel I.L., Langenhove L.V., Grabowska K. Fingertip skin models for analysis of the haptic perception of textiles. J. Biomed. Sci. Eng., 07 (01) (2014), pp. 1-6, 10.4236/jbise.2014.71001.

- American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists (AATCC) (2025), Evaluation Procedure (EP) 5, Guidelines for the Subjective Evaluation of Fabric Hand, in AATCC Manual of International Test Methods and Procedures (Vol. 100). Research Triangle Park, NC: American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists.

- Zeng F, Wang G, Qiao J, et al. Modeling the relationship between fabric textures and the evoked emotions through different sensory perceptions. Journal of Engineered Fibers and Fabrics. 2024;19. [CrossRef]

- Abreu, M. J., Martins, E., Nagamatsu, N., & Amaral, W. (2022). Tactile Perception in the Sensory Comfort of Fabric Samples. In Journal of Biomimetics, Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering (Vol. 57, pp. 57–63). Trans Tech Publications, Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Cardone, G., Ianiro, A., dello Ioio, G. et al. Temperature maps measurements on 3D surfaces with infrared thermography. Exp Fluids 52, 375–385 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Więcek, B., De Mey, G. (2011). Termowizja w podczerwieni: podstawy i zastosowania. Poland: Wydawnictwo PAK.

- Zhou, Y., Yu, H., Luo, M., & Zhou, X. (2024). Skin Heat Transfer and Thermal Sensation Coupling Model under Steady Stimulation. Buildings, 14(2), 547. [CrossRef]

- Mandal S, Annaheim S, Greve J, Camenzind M, Rossi RM. Modeling for predicting the thermal protective and thermo-physiological comfort performance of fabrics used in firefighters’ clothing. Textile Research Journal. 2018;89(14):2836-2849. [CrossRef]

- Bnar Ibrahim Omer, Yassin Mustafa Ahmed, Rzgar Mhammed Abdalrahman, Impact of textile types and their hybrids on the mechanical properties and thermal insulation of mohair-reinforced polyester Composite laminates, Results in Materials, Volume 21, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Stanisław Kocik, Agnes Psikuta, Joanna Ferdyn-Grygierek, Human body area view factors for radiative heat transfer: Influence of body region, shape, and posture, Building and Environment, Volume 281, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A., Psikuta, A., Annaheim, S., & Rossi, R. M. (2023). Modelling of heat and mass transfer in clothing considering evaporation, condensation, and wet conduction with case study. Building and Environment, 228, 109786 (16 pp.). [CrossRef]

- Kalaoglu-Altan OI, Kayaoglu BK, Trabzon L. Improving thermal conductivities of textile materials by nanohybrid approaches. iScience. 2022 Jan 30;25(3):103825. PMID: 35243220; PMCID: PMC8867053. [CrossRef]

- R.A. Scott, Cold weather clothing for military applications, Editor(s): J.T. Williams, In Woodhead Publishing Series in Textiles, Textiles for Cold Weather Apparel, Woodhead Publishing, 2009, pp 305-328. [CrossRef]

- Rajesh Mishra, Jiri Militky, Mohanapriya Venkataraman, Nanoporous materials, Editor(s): Rajesh Mishra, Jiri Militky, In The Textile Institute Book Series, Nanotechnology in Textiles, Woodhead Publishing, 2019, pp 311-353. [CrossRef]

- H. Gidik, G. Bedek, D. Dupont, Developing thermophysical sensors with textile auxiliary wall, Editor(s): Vladan Koncar, In Woodhead Publishing Series in Textiles, Smart Textiles and their Applications, Woodhead Publishing, 2016, pp. 423-453. [CrossRef]

- Elahi Mangat, A., Hes, L., Bajzik, V., & Mazari, A. (2018). Thermal absorptivity model of knitted rib fabric and its experimental verification. AUTEX Research Journal, 18(1), 3–8. [CrossRef]

- Atalie D, Tesinova P, Tadesse MG, Ferede E, Dulgheriu I, Loghin E. Thermo-Physiological Comfort Properties of Sportswear with Different Combination of Inner and Outer Layers. Materials (Basel). 2021 Nov 14;14(22):6863. PMID: 34832265; PMCID: PMC8624076. [CrossRef]

- Mandal S, Mazumder NU, Agnew RJ, Song G, Li R. Characterization and Modeling of Thermal Protective and Thermo-Physiological Comfort Performance of Polymeric Textile Materials-A Review. Materials (Basel). 2021 May 5;14(9):2397. PMID: 34062955; PMCID: PMC8124731. [CrossRef]

- Yucan Peng, Yi Cui, Thermal management with innovative fibers and textiles: manipulating heat transport, storage and conversion, National Science Review, Volume 11, Issue 10, October 2024, nwae295, . [CrossRef]

- Puszkarz, A.K., Machnowski, W. & Błasińska, A. Modeling of thermal performance of multilayer protective clothing exposed to radiant heat. Heat Mass Transfer 56, 1767–1775 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Gholamreza, F., Su, Y., Li, R., Nadaraja, A. V., Gathercole, R., Li, R., Dolez, P. I., Golovin, K., Rossi, R. M., Annaheim, S., & Milani, A. S. (2022). Modeling and Prediction of Thermophysiological Comfort Properties of a Single Layer Fabric System Using Single Sector Sweating Torso. Materials, 15(16), 5786. [CrossRef]

- Tang, K. H. D. (2025). Advances in Thermoregulating Textiles: Materials, Mechanisms, and Applications. Textiles, 5(2), 22. [CrossRef]

- Lei L, Shi S, Wang D, Meng S, Dai JG, Fu S, Hu J. Recent Advances in Thermoregulatory Clothing: Materials, Mechanisms, and Perspectives. ACS Nano. 2023 Feb 14;17(3):1803-1830. Epub 2023 Feb 2. PMID: 36727670. [CrossRef]

- Lama Hamadeh, Amin Al-Habaibeh, Towards reliable smart textiles: Investigating thermal characterisation of embedded electronics in E-Textiles using infrared thermography and mathematical modelling, Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, Volume 338, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F.L. Zhu, Q.Q. Feng, Recent advances in textile materials for personal radiative thermal management in indoor and outdoor environments, International Journal of Thermal Sciences, Volume 165, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Da Yu Tzou, The generalized lagging response in small-scale and high-rate heating, International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, Volume 38, Issue 17, 1995, Pages 3231-3240. [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, S., Kothari, S., Kumar, R. (2014). Dual Phase-Lag Thermoelasticity. In: Hetnarski, R.B. (eds) Encyclopedia of Thermal Stresses. Springer, Dordrecht. [CrossRef]

- Quintanilla, R., Racke, R. (2007). Qualitative aspects in dual-phase-lag heat conduction. Proc. R. Soc. A.463659–674. [CrossRef]

- KatoTech, Kawabata Thermo Labo System KES-F7, information available at https://english.keskato.co.jp/archives/products/kes-f7 on July 22, 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).