1. Introduction

Since the advent of the “theory of climates”, most famously articulated by Montesquieu in The Spirit of Laws [

1], who argued that variations in climate shape people’s temperament, behavior, and even political institutions, scholars have long speculated on the influence that meteorological and seasonal dynamics exert on human well-being and behavior. While early theory posited relatively deterministic effects, empirical research over the past decades has yielded a far more nuanced and inconclusive picture. Systematic reviews indicate that meteorological influences are often moderate at best, whereas others report negligible or context-specific strong associations [

2,

3]. This divergence reflects not only the complexity of human responses to environmental factors but also recurrent methodological and measurement limitations that constrain the reliability of prior findings.

Comparative assessments of systematic reviews have shown that work on temperature and weather effects frequently suffers from deficiencies in protocol registration, risk-of-bias assessment, and reporting transparency, raising questions about the robustness of previous conclusions [

4]. Umbrella reviews further highlight that confidence in the existing evidence is often low to critically low, largely due to inconsistent operationalization of outcomes, high heterogeneity across studies, and limited ability to address confounding or interactions [

5]. Meta-analyses on ambient temperature and mental health corroborate these findings, showing that although associations can be detected, effect sizes are highly variable, heterogeneity is substantial, and analytical approaches rarely capture lagged or non-linear effects [

2].

Further complications arise when contrasting objective measurements with subjective perceptions. Studies show only weak correspondence between meteorological indicators and self-reported experiences of weather, suggesting that perceptual and reporting biases may distort observed associations [

6,

7,

8]. Similarly, subjective well-being measures, often collected through self-reported surveys or experience sampling, are prone to recall bias, mood effects, contextual influences, and missing responses, which can lead to inconsistencies between reported and actual states [

9,

10]. This gap is not trivial, as much of the existing evidence relies on self-reported well-being or retrospective survey data, meaning that discrepancies between experienced and measured conditions could systematically distort effect estimates. The issue is equally salient for mobility, since weather is known to influence transport choices, activity locations, and the use of active versus motorized modes. Yet research demonstrates that self-reported travel adaptations to weather often diverge from mobility patterns captured through GPS or sensor-based tracking, suggesting that individuals may underreport, misremember, or misclassify their behavioral responses to meteorological variation [

11,

12]. Capturing both places visited, weather conditions, and objective well-being through multimodal, high-resolution tracking is therefore crucial to disentangle actual behavioral and affective changes from perceptual bias, and to generate more credible estimates of the true impact of meteorological variability.

In light of these gaps, we contribute to the growing research on the impact of weather on well-being and mobility through the analysis of longitudinal objective and subjective multi-source data collected as part of an observational study conducted in Switzerland in 2024 [

13]. Through the integration of high quality MeteoSwiss weather data, reliable data filtering, and the use of mixed-effects linear regression models, we estimate the effects of weather on several outcomes related to objective and subjective well-being and on distances traveled with different transportation types while controlling for potential socio-demographic confounders. Our work fits in field of environmental health research by demonstrating the feasibility of integrating objective multi-source data to derive practical insights into the effect of environmental factors on humans. Its design mitigates between-person confounding, ensures temporal granularity, and addresses measurement limitations, thereby offering a robust contribution to understanding whether—and to what extent—weather variations shape human well-being and behavioral choices.

The structure of the paper is as follows.

Section 2 provides an overview of previous research investigating the relationships between weather, well-being, and mobility choices.

Section 3 describes the study protocol, the data used, and the statistical methods that we employed.

Section 4 reports the estimates of the weather effects on well-being and mobility that we drew from our sample of observations. Finally,

Section 5 provides a critical discussion of the results and of their limitations, while

Section 6 summarizes the work and provides insights for future works.

2. Related Work

Previous literature found evidence that atmospheric weather has an effect on both well-being [

14] and mobility [

15]. Among several well-being outcomes, researchers investigated the relationship between weather and subjective well-being [

16,

17], happiness [

18,

19], sleep [

20,

21,

22,

23], physical activity and sedentary behaviors [

24,

25], anxiety and depression [

26]. However, results are often inconsistent across studies, with authors finding small or non-significant effects [

25]. As an example, Feddersen et al. found that warm and sunny days are associated with higher levels of self-reported well-being [

17], while Connolly et al. reported that, in regions with hot weather, increase in temperature levels cause a decrease in well-being [

16]. Weather effects on well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic were also analyzed, with results reporting no influence of weather on mental well-being during the pandemic [

25]. The different results reported in literature on the effects of weather may be due different methodologies in the self-assessment of well-being, with studies involving large cohorts solely relying on self-reported information, which may be affected by recall bias and aggregation over long time windows [

16,

17,

18,

19,

24,

25,

26]. Instead, few studies focused on the use of objective data to measure the impact of weather on well-being. The use of objective measurements allows to reduce the risks of recall bias in self-reported data, and it also allows researchers to collect several measurements of well-being over extended periods of time with less burden posed on study participants, as few to none active tasks are needed. The use of commercial devices for well-being tracking, such as smartwatches and smart rings, allows for the continuous and passive monitoring of objective physiological data through which objective information can then be derived and used for the estimation of weather effects on well-being. An example use of objective data in the sleep domain is from Mattingly et al [

20]. In this study, the authors employed a subset of the Tesserae dataset [

27] to assess the impact of weather on sleep duration, bedtime, and wake-up times through a year long multimodal study. The authors exploited objective data collected through smartwatches (Garmin Vivosmart 3) and linked them to the weather of participants’ homes. Results from this study (216 participants, 51836 observations) indicated small but statistically significant seasonal and weather effects, with bedtimes and wake-up times being later with increasing temperature values, and sleep duration being lower with increasing lengths of the day. Recently, Li et al. [

23] reported their analysis on more than 23 millions observations and more than 200 participants, with increasing temperature linked to reduced total sleep time. In a study with an objective measure of physical activity through accelerometers, (127 participants, 720 observations) Sumukadas et al. found day length, temperature, and sunshine to explain 73% of the variance in measured daily activity [

28]. In a similar study by Feinglass et al., the authors analyzed the effects of weather on a three-year long study with six weekly measurement waves (241 participants, 4823 observations) and found daylight hours, cold and hot days, and light or heavy rainfall to be associated with lower physical health [

29]. Similar results on physical activity were found in several studies using accelerometer-based measurements or steps counts from commercial wearables [

24,

30,

31].

Well-being is not the only domain that was investigated in relationship with weather data. A vast literature corpus deals with the analysis of the effects of atmospheric weather (temperature, precipitation, humidity, ...) on human mobility and transportation mode choices [

15]. Climate change, with its consequences on weather, can have tremendous effects on human mobility and transportation choices, and therefore it is necessary to investigate how transport mode choices are influenced by weather to take appropriate actions in time [

32]. Similar to what we previously described for well-being, in the mobility domain authors either relied on self-reported information through surveys [

33,

34,

35,

36] or based their analysis on objective data (e.g., GPS traces provided by smartphones or dedicated trackers, smart cards transactions, ...) [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. Among studies that focused on the use of objective mobility data, Pang et al. built a global dataset based on mobility assessed through data retrieved via social networks and found nice weather (high temperature and moderate pressure) to have a positive impact on human mobility [

37]. Lepage et al. integrated data from bike sharing, taxi, and public transport companies to analyze transportation demand under different metereological conditions [

40]. Otim et al. used a total of 2671 GPS trajectories from Bejing to analyze transport mode choices [

41]. Even though several studies focusing on the assessment of the effects of weather on mobility make use of objective data, the majority of them are typically cross-sectional, with surveys containing information from each study participant only for a single day/trip, thus failing into capturing intra-subject fluctuations due to weather differences.

5. Discussion

In this manuscript we reported the study design, methodology and the results obtained when assessing the impact of weather, as measured by mean daily temperature, level of precipitation, and sunshine duration, on ten different outcomes related to well-being (activity, recovery, sleep, and stress) and mobility. For our analysis, we used the dataset collected as part of the RENEWAL study [

13], that involved a total of 294 participants for 30 continuous days and for which objective data (i.e., physiological data through Garmin Health API) and self-reported data (i.e., surveys and ecological momentary assessments) were retrieved. Given the longitudinal nature of our dataset, we employed MELR models to analyze how three key weather predictors, namely mean daily temperature, total daily precipitation, and total sunshine duration, affect these outcomes taking into account both intra-person and inter-person differences. To improve the robustness of our analysis, we filtered our daily observations with strict criteria to keep only reliable observations. We considered only weekdays in which the provided smartwatch was worn more than 70% of the time and for which automatic sleep tracking was available. Furthermore, we kept only days with at least 70% coverage in terms of location data, and we excluded days with presumed travels too far away from home (i.e., with maximum daily distance greater than 300 km), similar to what was done in [

20]. Our final dataset consisted of 2120 daily observations from 151 participants, spanning the period from February to May 2024, with a median (

) number of observations available per participant of 14 (10,22).

Our analysis showed modest effects of weather on both well-being and mobility outcomes. For well-being, MELR models found a positive effect of temperature on total sleep time, wake-up time, and physiological stress, while a negative association with temperature was found for self-reported stress values and the percentage of sedentary time during the day. The amount of sunshine during the day positively affected the physiologically measured stress and the percentage of sedentary time during the day, while negatively impacting the recovery during the next night sleep. We didn’t find any statistically significant association between weather and bedtime and the total number of daily steps. Our results for wake-up time, are in line with was found by Mattingly et al. [

20] with objective sleep data tracked with Garmin smartwatches. The authors found a modest effect of daily temperature on wake-up time. However, their study was conducted over a longer period of time, with participants enrolled for approximately a year. Therefore, authors were able to include also seasonality among the predictors for MELR models, and seasons resulted significant in the prediction of other sleep-related outcomes (total sleep time, bedtime, and wake-up time). In the same study, in contrast to our results temperature was not found to be associated with total sleep time, which was instead affected by season, with sleep duration decreasing in spring with respect to winter. Similarly, in a recent paper by Li et al. [

23] which included automatic sleep tracking through Huawei smartwatches, the authors found total sleep time to be reduced by approximately 10 minutes for every 10

∘ increase in temperature. This contrasting results on sleep-related outcomes may be explained by the limited observation period of our study, with the majority of observations belonging to spring and with little temperature variations. Due to this, we were not able to include seasonality effects in our models, and we instead weather to impact total sleep time and wake-up time, suggesting a shift in wake-up times with increasing temperature, with bedtime remaining unaffected. As far as the activity domain is concerned, our results are in line with previous findings that reported increasing physical activity with increasing temperature and sunshine duration [

24,

28,

29,

31]. Our models showed a statistically significant effect of temperature and sunshine duration on the percentage of time spent in active or highly active states (i.e., non-sedentary behavior) but not on the amount of daily steps, suggesting an increasing extent of physical activities not necessarily including walking or running exercises. Interesting, we found opposite results when assessing the impact of weather on stress. In our models, we used two different stress measurements: an objective stress measure, defined as the mean stress value reported by the Garmin smartwatch (i.e., a Garmin proprietary algorithm based on HRV and heart rate analysis [

54]) and the self-reported stress value in the daily diaries. While we found warmer days to reduce the self-reported stress value, in line with previous large-scale survey-based studies [

17,

25], our analysis showed temperature and sunshine duration to increase the amount of physiological stress as measured through HRV and heart rate, which, to the best of our knowledge, is still unexplored in the available literature. This can be explained by the fact that self-reported and physiological stress are two different representations, with authors finding small to medium effect sizes between self-reported stress and objective physiological stress measures [

55]. Furthermore, objective stress measured by Garmin through their proprietary algorithms takes into account also the extent of activity and the recovery phases following it, thus suggesting that warmer and longer days are linked to a greater amount of activity carried out during the day, as confirmed by our results on effects of weather on sedentary behaviors. Finally, for well-being we also assessed the impact of weather on a the night recovery, i.e. on the amount of “energy" recovered by the body while sleeping at time and being in a rest state. Our models showed a significant modest and negative effect of the sunshine duration on this outcome.

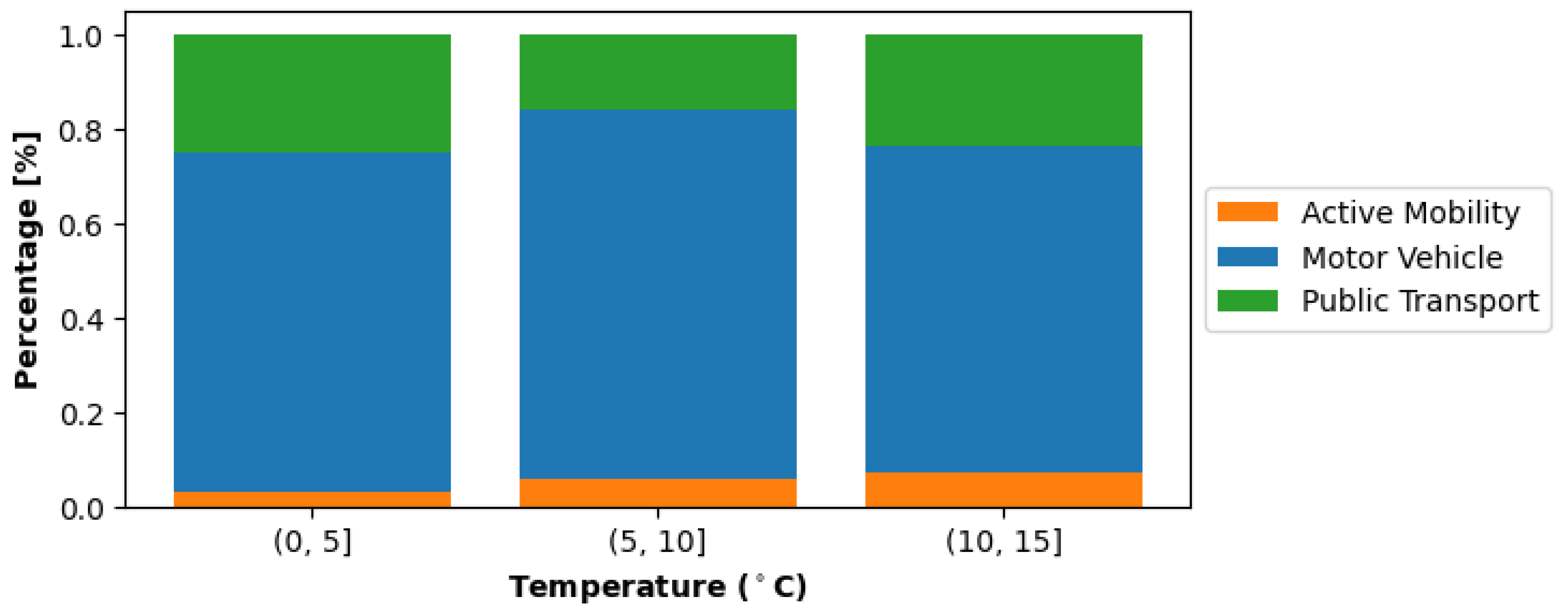

Moving on to the mobility domain, we assessed the impact of weather on the total daily traveled distance according to three different mobility types: active mobility, motor vehicles, and public transport. We found a statistically significant effect of precipitation on both active mobility and public transport, with a reduced distance traveled by active mobility with increasing precipitation, while the opposite holds for public transport, with increased distances with higher precipitation values. When modeling the distance traveled by motor vehicles, we didn’t find any significant effect of weather. This analysis may suggest an overall stability of distances traveled with motor vehicles, while distance traveled using active mobility transportation types (mainly walking or cycling) are replaced with public transportation in case of higher precipitations during the day. When compared to other studies using objective mobility and location data, Pang et al. found a positive effect of weather on the overall mobility, without differentiating between different types of mobility [

37]. Lepage et al. found precipitation to reduce the amount of bikesharing (i.e., indirect measurement of distance traveled with active mobility) [

40], while Otim et al. didn’t include precipitation among the predictors for transport mode choices, and found higher temperature to increase the amount of walking share and to reduce bike share [

41].

This study does not come without limitations. First of all, when compared to other studies using objective data for well-being and mobility assessments, our dataset is smaller. In the two largest studies assessing the impact of weather on sleep, Mattingly et al. had a total of 51836 observations [

20] and Li et al. 23 million observations [

23], which are way larger than our 2120 observations. These datasets also span multiple monitoring months, allowing to assess also the effect of seasons rather than only daily weather measurements. Ours, instead, was limited to a short observation period of four spring months during the year 2024, limiting the possibility of studying seasonal effects on the chosen outcomes. In addition to this, our observations were confined in the region of Canton Ticino (Switzerland) and northern Italy, and study participants were mostly mostly office and information workers, thus limiting the generalization capabilities of our results, since other populations (e.g., shift workers) and/or countries with different weather conditions may experience different effects of weather on their well-being and mobility. Furthermore, while on one hand the strict filtering process that we carried out on the dataset left us with a reliable set of observations, on the other hand it may have introduced a bias in the dataset as only the highly compliant participants were left in the analytical sample used for the modeling. Finally, our analysis on mobility distances considered them as a whole during the day, without splitting them into commuting or recreational trips, which could help into better assessing the impact of weather [

36]. As an example, Sabir et al. found commuting (recreational) trips to be less (more) affected by weather conditions [

33].

Even when considering these potential limitations our results on longitudinal objective and subjective data confirm previous findings in literature for several of the analyzed outcomes (sleep and self-reported stress), while at the same providing new and interesting insights on other outcomes (objective physiological stress and night recovery). The main robustness of our study lays in the use of objective data for the assessment of weather impacts, with the majority of the studies using self-reported aggregated data. Our analysis also showed that it is possible to use passively collected GLH data for the assessment of weather impact on mobility, potentially allowing for the use of the enormous amount of retrospective GLH data to further refine the results reported in this manuscript. We believe that future improvements on the framework outlined in this paper, with longer observation periods spanning multiple locations, can help assessing the impact of weather on well-being and mobility, driving insights and policies that could prevent severe impacts due to climate change.

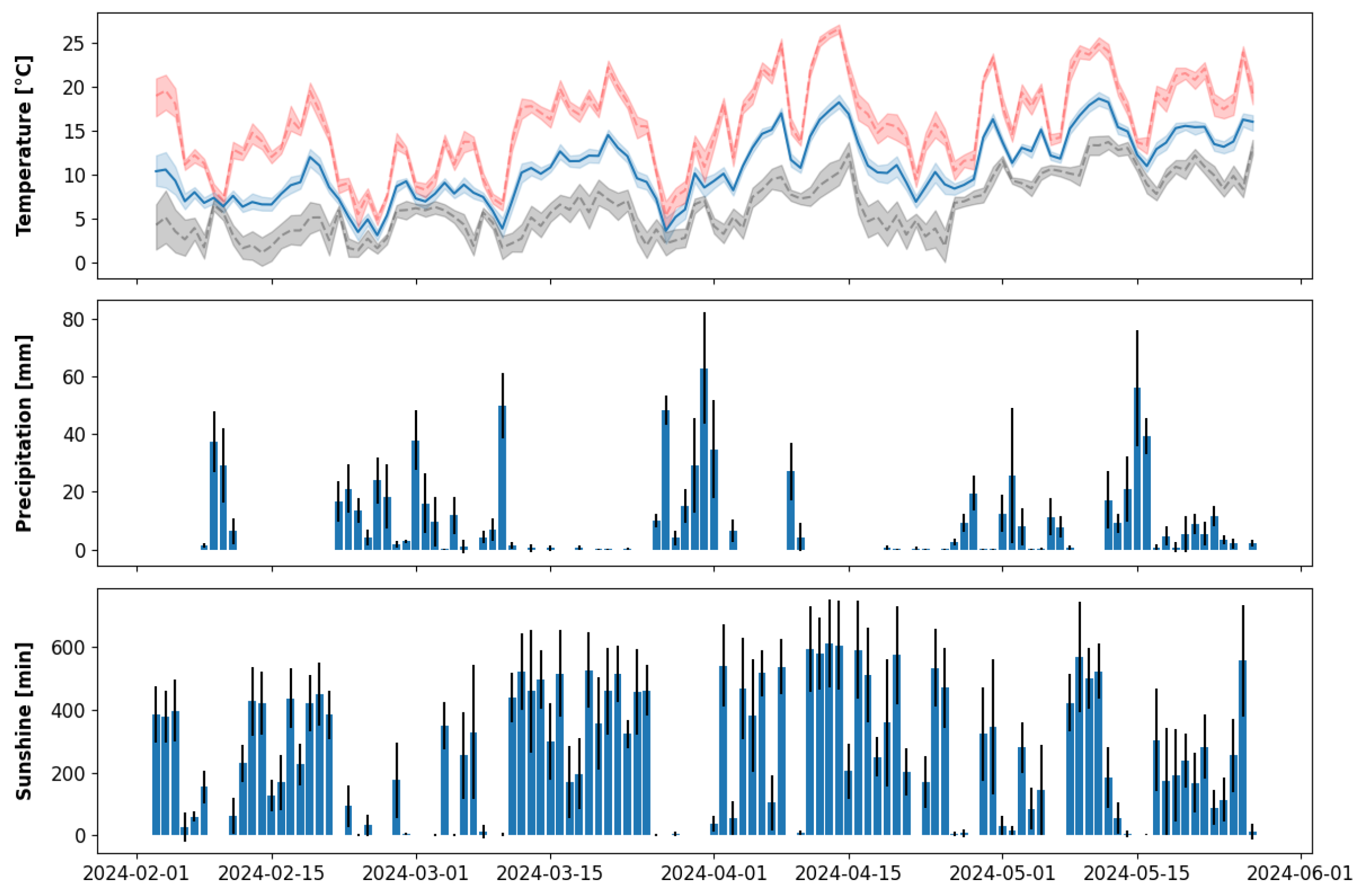

Figure 1.

Temperature (top), precipitation (middle), and sunshine duration (bottom) data from the day of the first participant in up to the day of the last participant out. Temperature data are shown as mean (blue solid line), minimum (black dashed line) and maximum (red dashed line), together with the corresponding 95% CI. Precipitation and sunshine duration data are reported as mean (bar height) and standard deviation (error bar). All data refer to the 7 weather stations that were employed for the retrieval of weather data.

Figure 1.

Temperature (top), precipitation (middle), and sunshine duration (bottom) data from the day of the first participant in up to the day of the last participant out. Temperature data are shown as mean (blue solid line), minimum (black dashed line) and maximum (red dashed line), together with the corresponding 95% CI. Precipitation and sunshine duration data are reported as mean (bar height) and standard deviation (error bar). All data refer to the 7 weather stations that were employed for the retrieval of weather data.

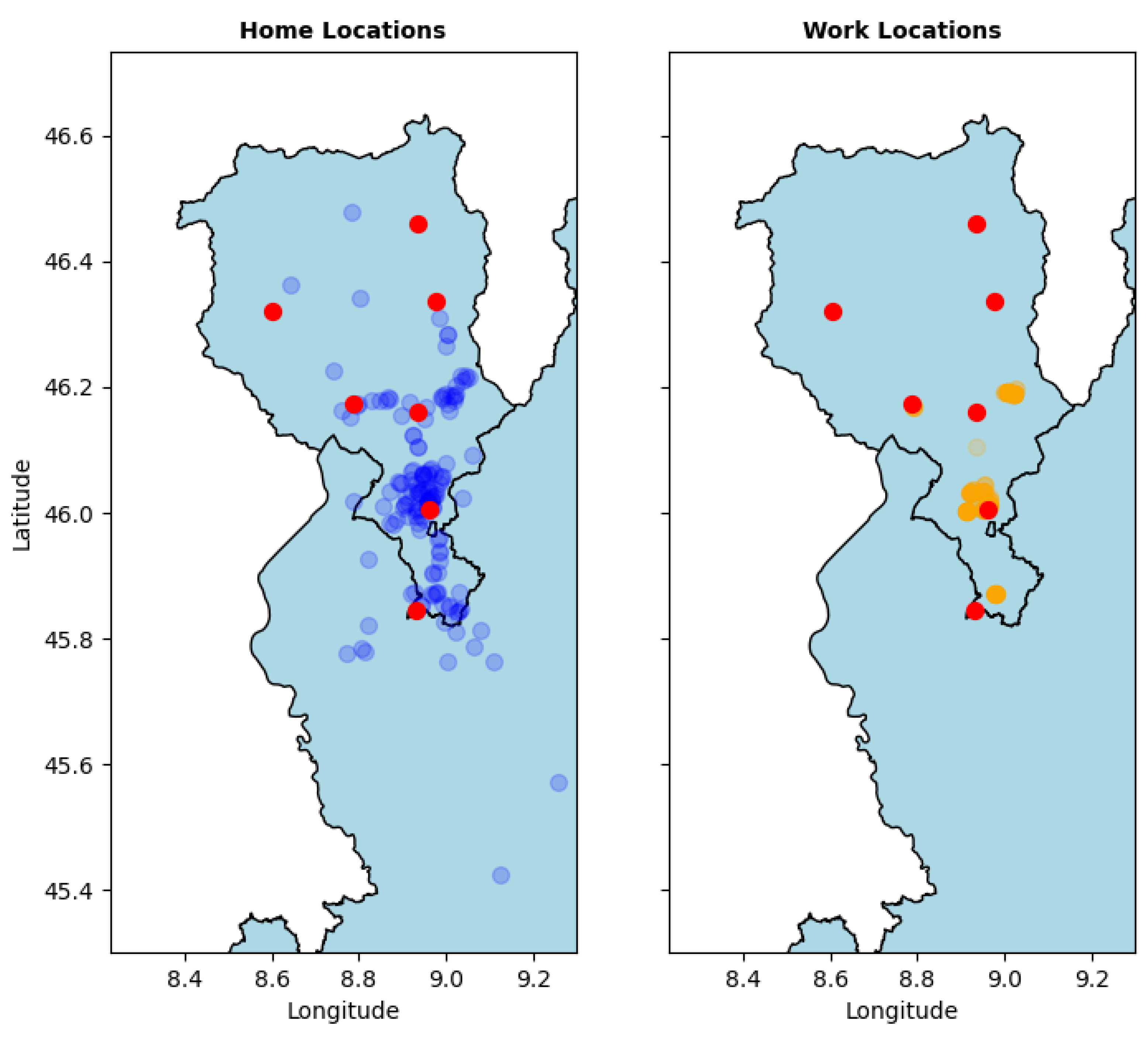

Figure 2.

Coordinates of weather stations employed for the retrieval of weather information (red points) and home (left plot) and work (right plot) location coordinates of the subset of study participants used for the analysis.

Figure 2.

Coordinates of weather stations employed for the retrieval of weather information (red points) and home (left plot) and work (right plot) location coordinates of the subset of study participants used for the analysis.

Table 1.

Detailed description of the outcomes considered for the MELR analysis, together with their source and scale. A.U.: Arbitrary Unit.

Table 1.

Detailed description of the outcomes considered for the MELR analysis, together with their source and scale. A.U.: Arbitrary Unit.

| Domain |

Outcome |

Source |

Description |

Scale |

Unit |

| Well-being |

Daily Steps |

Garmin |

Count of daily steps while awake |

|

Steps |

| |

Sedentary % |

|

% of time in sedentary state while awake |

0-100 |

% |

| |

Bedtime |

|

Bedtime on next night |

0-24 |

Hours |

| |

Wake-up Time |

|

Wake-up on next night |

0-24 |

Hours |

| |

Total Sleep Time |

|

Total amount of sleep hours |

|

Hours |

| |

Night Recovery |

|

Normalized change of body battery while sleeping |

|

% |

| |

Daily Stress |

|

Mean measured physiological stress |

|

A.U. |

| |

Self-Reported Stress |

Diary |

Perceived stress during the day |

|

A.U. |

| Mobility |

Active Mobility |

GLH |

Total daily distance traveled with active mobility |

|

km |

| |

Motor Vehicle |

|

Total daily distance traveled with motor vehicles |

|

km |

| |

Public Transport |

|

Total daily distance traveled with public transport |

|

km |

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of the continuous variables. Bedtime and wake-up time are reported as hours from midnight.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of the continuous variables. Bedtime and wake-up time are reported as hours from midnight.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Outcome |

Daily Steps |

8392.07 |

3682.85 |

5782.25 |

7859.50 |

10280.00 |

| |

Sedentary % |

82.12 |

7.58 |

77.71 |

83.17 |

87.40 |

| |

Total Sleep Time [hours] |

7.14 |

1.35 |

6.35 |

7.17 |

7.98 |

| |

Bedtime [hours] |

-0.48 |

1.36 |

-1.40 |

-0.65 |

0.30 |

| |

Wake-up Time [hours] |

6.95 |

1.31 |

6.15 |

6.83 |

7.52 |

| |

Mean Stress [%] |

50.71 |

14.64 |

40.23 |

51.51 |

61.20 |

| |

Self-Reported Stress [1-5] |

2.47 |

0.98 |

2.00 |

2.00 |

3.00 |

| |

Night Recovery [%] |

58.37 |

27.57 |

34.74 |

57.90 |

83.20 |

| |

Active Mobility [km] |

2.77 |

5.81 |

0.00 |

0.59 |

2.63 |

| |

Motor Vehicles [km] |

31.32 |

49.92 |

0.35 |

16.69 |

41.39 |

| |

Public Transport [km] |

8.99 |

30.86 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.85 |

| Weather |

Temperature [∘ C] |

11.20 |

3.17 |

8.80 |

11.20 |

13.00 |

| |

Precipitation [mm] |

5.56 |

11.85 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

3.80 |

| |

Sunshine [hours] |

5.25 |

4.16 |

0.34 |

5.27 |

9.12 |

Table 4.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting the total number of daily steps while awake. For the sake of clarity, coefficients are rounded to nearest integer. Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold. *;**;*** MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

Table 4.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting the total number of daily steps while awake. For the sake of clarity, coefficients are rounded to nearest integer. Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold. *;**;*** MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

| |

Daily Steps |

| |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

| |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

| Intercept |

8470*** |

8086 to 8854 |

8011*** |

6607 to 9416 |

7538*** |

6052.0 to 9024.0 |

| Age |

|

|

5 |

-38 to 48 |

6 |

-37 to 49 |

| Sex [0=Female] |

|

|

-439 |

-1251 to 373 |

-432 |

-1242 to 379 |

| Company [0=C1] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C2 |

|

|

-367 |

-1856 to 1121 |

-448 |

-1936 to 1039 |

| C3 |

|

|

925 |

-467 to 2317 |

851 |

-539 to 2241 |

| C4 |

|

|

728 |

-681 to 2136 |

546 |

-871 to 1964 |

| C5 |

|

|

1422* |

190.0 to 2654 |

1256* |

16 to 2495 |

| C6 |

|

|

755 |

-865 to 2374 |

742 |

-875 to 2359 |

| Supervisor role [0=No] |

|

|

-113 |

-927 to 702 |

-118 |

-932 to 695 |

| Having children [0=No] |

|

|

-80 |

-861 to 701 |

-81 |

-860 to 698 |

| SF-12 MCS |

|

|

66** |

19 to 112 |

66** |

20 to 113 |

| SF-12 PCS |

|

|

86** |

22 to 150 |

87** |

23 to 151 |

| Temperature |

|

|

|

|

41 |

-13 to 95 |

| Precipitation |

|

|

|

|

-7 |

-19 to 6 |

| Sunshine Duration |

|

|

|

|

30 |

-9 to 70 |

| Marginal R2 |

0.000 |

0.062 |

0.067 |

| ICC |

0.378 |

Table 5.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting the percentage of sedentary time while awake. Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold.

*;**;***MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

Table 5.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting the percentage of sedentary time while awake. Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold.

*;**;***MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

| |

Sedentary % |

| |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

| |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

| Intercept |

81.989*** |

81.117 to 82.861 |

83.995*** |

80.842 to 87.149 |

85.487*** |

82.202 to 88.772 |

| Age |

|

|

0.021 |

-0.075 to 0.117 |

0.018 |

-0.078 to 0.115 |

| Sex [0=Female] |

|

|

2.31* |

0.488 to 4.132 |

2.295* |

0.475 to 4.114 |

| Company [0=C1] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C2 |

|

|

-1.014 |

-4.354 to 2.326 |

-0.798 |

-4.137 to 2.54 |

| C3 |

|

|

-2.980 |

-6.107 to 0.146 |

-2.817 |

-5.940 to 0.306 |

| C4 |

|

|

-1.940 |

-5.103 to 1.223 |

-1.489 |

-4.666 to 1.688 |

| C5 |

|

|

-3.839** |

-6.605 to -1.073 |

-3.414* |

-6.193 to -0.636 |

| C6 |

|

|

-3.472 |

-7.109 to 0.165 |

-3.456 |

-7.089 to 0.176 |

| Supervisor role [0=No] |

|

|

-0.148 |

-1.977 to 1.681 |

-0.141 |

-1.967 to 1.686 |

| Having children [0=No] |

|

|

-1.484 |

-3.235 to 0.267 |

-1.482 |

-3.231 to 0.266 |

| SF-12 MCS |

|

|

-0.063 |

-0.167 to 0.042 |

-0.064 |

-0.169 to 0.040 |

| SF-12 PCS |

|

|

-0.196** |

-0.340 to -0.053 |

-0.201** |

-0.345 to -0.057 |

| Temperature |

|

|

|

|

-0.115* |

-0.218 to -0.012 |

| Precipitation |

|

|

|

|

0.003 |

-0.021 to 0.026 |

| Sunshine Duration |

|

|

|

|

-0.093* |

-0.168 to -0.017 |

| Marginal R2 |

0.000 |

0.087 |

0.094 |

| ICC |

0.475 |

Table 6.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting total sleep time. Total sleep time is measured in decimal hours. Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold. *;**;*** MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

Table 6.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting total sleep time. Total sleep time is measured in decimal hours. Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold. *;**;*** MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

| |

Total Sleep Time |

| |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

| |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

| Intercept |

7.147*** |

7.03 to 7.264 |

7.331*** |

6.899 to 7.763 |

7.025*** |

6.550 to 7.500 |

| Age |

|

|

-0.009 |

-0.022 to 0.005 |

-0.008 |

-0.021 to 0.005 |

| Sex [0=Female] |

|

|

-0.403** |

-0.653 to -0.152 |

-0.398** |

-0.648 to -0.148 |

| Company |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C2 |

|

|

0.002 |

-0.456 to 0.461 |

-0.038 |

-0.498 to 0.421 |

| C3 |

|

|

0.173 |

-0.255 to 0.601 |

0.163 |

-0.264 to 0.591 |

| C4 |

|

|

-0.086 |

-0.519 to 0.348 |

-0.177 |

-0.616 to 0.262 |

| C5 |

|

|

0.109 |

-0.269 to 0.488 |

0.027 |

-0.357 to 0.410 |

| C6 |

|

|

0.187 |

-0.311 to 0.686 |

0.194 |

-0.303 to 0.692 |

| Supervisor role [0=No] |

|

|

-0.074 |

-0.325 to 0.177 |

-0.069 |

-0.320 to 0.181 |

| Having children [0=No] |

|

|

0.052 |

-0.189 to 0.293 |

0.050 |

-0.191 to 0.290 |

| SF-12 MCS |

|

|

0.001 |

-0.013 to 0.016 |

0.001 |

-0.013 to 0.016 |

| SF-12 PCS |

|

|

-0.004 |

-0.024 to 0.015 |

-0.004 |

-0.024 to 0.016 |

| Temperature |

|

|

|

|

0.030** |

0.008 to 0.051 |

| Precipitation |

|

|

|

|

0.003 |

-0.002 to 0.008 |

| Sunshine Duration |

|

|

|

|

0.000 |

-0.016 to 0.016 |

| Marginal R2 |

0.000 |

0.036 |

0.039 |

| ICC |

0.240 |

Table 7.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting bedtime. Bedtime is measured in decimal hours from midnight. Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold. *;**;*** MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

Table 7.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting bedtime. Bedtime is measured in decimal hours from midnight. Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold. *;**;*** MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

| |

Bedtime |

| |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

| |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

| Intercept |

-0.481*** |

-0.628 to -0.334 |

-0.871** |

-1.389 to -0.353 |

-1.018*** |

-1.566 to -0.470 |

| Age |

|

|

-0.017* |

-0.033 to -0.001 |

-0.016* |

-0.032 to -0.000 |

| Sex [0=Female] |

|

|

0.508** |

0.208 to 0.808 |

0.511** |

0.211 to 0.811 |

| Company |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C2 |

|

|

-0.271 |

-0.82 to 0.279 |

-0.292 |

-0.842 to 0.258 |

| C3 |

|

|

0.045 |

-0.469 to 0.559 |

0.044 |

-0.470 to 0.558 |

| C4 |

|

|

0.434 |

-0.086 to 0.954 |

0.384 |

-0.140 to 0.909 |

| C5 |

|

|

0.321 |

-0.134 to 0.775 |

0.277 |

-0.181 to 0.736 |

| C6 |

|

|

0.134 |

-0.464 to 0.732 |

0.139 |

-0.459 to 0.737 |

| Supervisor role [0=No] |

|

|

0.099 |

-0.201 to 0.4 |

0.103 |

-0.198 to 0.404 |

| Having children [0=No] |

|

|

-0.265 |

-0.553 to 0.024 |

-0.266 |

-0.555 to 0.022 |

| SF-12 MCS |

|

|

-0.005 |

-0.023 to 0.012 |

-0.005 |

-0.023 to 0.012 |

| SF-12 PCS |

|

|

-0.017 |

-0.041 to 0.007 |

-0.017 |

-0.040 to 0.007 |

| Temperature |

|

|

|

|

0.017 |

-0.003 to 0.036 |

| Precipitation |

|

|

|

|

0.002 |

-0.003 to 0.006 |

| Sunshine Duration |

|

|

|

|

-0.005 |

-0.020 to 0.009 |

| Marginal R2 |

0.000 |

0.093 |

0.094 |

| ICC |

0.415 |

Table 8.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting wake-up time. Wake-up time is measured in decimal hours from midnight. Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold. *;**;*** MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

Table 8.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting wake-up time. Wake-up time is measured in decimal hours from midnight. Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold. *;**;*** MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

| |

Wakeup |

| |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

| |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

| Intercept |

6.959*** |

6.827 to 7.092 |

6.816*** |

6.357 to 7.275 |

6.326*** |

5.832 to 6.819 |

| Age |

|

|

-0.022** |

-0.036 to -0.008 |

-0.021** |

-0.035 to -0.007 |

| Sex [0=Female] |

|

|

0.089 |

-0.177 to 0.355 |

0.097 |

-0.169 to 0.364 |

| Company |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C2 |

|

|

-0.242 |

-0.729 to 0.245 |

-0.308 |

-0.796 to 0.181 |

| C3 |

|

|

0.196 |

-0.259 to 0.651 |

0.184 |

-0.272 to 0.64 |

| C4 |

|

|

0.269 |

-0.191 to 0.73 |

0.121 |

-0.345 to 0.587 |

| C5 |

|

|

0.374 |

-0.029 to 0.776 |

0.241 |

-0.166 to 0.648 |

| C6 |

|

|

0.292 |

-0.237 to 0.822 |

0.306 |

-0.225 to 0.836 |

| Supervisor role [0=No] |

|

|

-0.012 |

-0.278 to 0.255 |

-0.003 |

-0.27 to 0.264 |

| Having children [0=No] |

|

|

-0.22 |

-0.476 to 0.035 |

-0.225 |

-0.481 to 0.031 |

| SF-12 MCS |

|

|

-0.007 |

-0.023 to 0.008 |

-0.007 |

-0.023 to 0.008 |

| SF-12 PCS |

|

|

-0.019 |

-0.04 to 0.002 |

-0.019 |

-0.04 to 0.002 |

| Temperature |

|

|

|

|

0.049*** |

0.029 to 0.069 |

| Precipitation |

|

|

|

|

0.006* |

0.001 to 0.01 |

| Sunshine Duration |

|

|

|

|

-0.004 |

-0.019 to 0.01 |

| Marginal R2 |

0.000 |

0.09 |

0.10 |

| ICC |

0.347 |

Table 9.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting mean stress value during the day. Mean stress goes from a minimum of 0 (no stress) to a maximum of 100 (high stress). Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold. *;**;*** MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score

Table 9.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting mean stress value during the day. Mean stress goes from a minimum of 0 (no stress) to a maximum of 100 (high stress). Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold. *;**;*** MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score

| |

Mean Stress |

| |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

| |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

| Intercept |

50.878*** |

48.94 to 52.815 |

47.498*** |

40.271 to 54.725 |

45.177*** |

37.788 to 52.566 |

| Age |

|

|

-0.016 |

-0.237 to 0.204 |

-0.012 |

-0.234 to 0.209 |

| Sex [0=Female] |

|

|

-1.07 |

-5.242 to 3.101 |

-1.047 |

-5.229 to 3.134 |

| Company |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C2 |

|

|

3.934 |

-3.715 to 11.582 |

3.602 |

-4.067 to 11.271 |

| C3 |

|

|

4.003 |

-3.167 to 11.173 |

3.76 |

-3.428 to 10.948 |

| C4 |

|

|

5.925 |

-1.326 to 13.176 |

5.242 |

-2.046 to 12.53 |

| C5 |

|

|

4.359 |

-1.982 to 10.700 |

3.714 |

-2.658 to 10.087 |

| C6 |

|

|

7.442 |

-0.895 to 15.780 |

7.422 |

-0.935 to 15.779 |

| Supervisor role [0=No] |

|

|

-0.588 |

-4.779 to 3.604 |

-0.598 |

-4.799 to 3.604 |

| Having children [0=No] |

|

|

0.139 |

-3.868 to 4.146 |

0.136 |

-3.880 to 4.153 |

| SF-12 MCS |

|

|

-0.343** |

-0.582 to -0.104 |

-0.341** |

-0.581 to -0.101 |

| SF-12 PCS |

|

|

0.196 |

-0.133 to 0.525 |

0.203 |

-0.127 to 0.533 |

| Temperature |

|

|

|

|

0.176* |

0.016 to 0.336 |

| Precipitation |

|

|

|

|

-0.001 |

-0.038 to 0.036 |

| Sunshine Duration |

|

|

|

|

0.143* |

0.027 to 0.260 |

| Marginal R2 |

0.000 |

0.076 |

0.080 |

| ICC |

0.659 |

Table 10.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting the self-reported stress value. Self-reported stress goes from a minimum of 1 (no stress) to a maximum of 5 (extreme stress). Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold. *;**;*** MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

Table 10.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting the self-reported stress value. Self-reported stress goes from a minimum of 1 (no stress) to a maximum of 5 (extreme stress). Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold. *;**;*** MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

| |

Self-Reported Stress |

| |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

| |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

| Intercept |

2.487*** |

2.385 to 2.588 |

2.350*** |

2.004 to 2.696 |

2.64*** |

2.272 to 3.008 |

| Age |

|

|

0.002 |

-0.009 to 0.012 |

0.001 |

-0.010 to 0.011 |

| Sex [0=Female] |

|

|

0.244* |

0.044 to 0.444 |

0.238* |

0.040 to 0.437 |

| Company |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C2 |

|

|

-0.04 |

-0.407 to 0.326 |

-0.000 |

-0.365 to 0.364 |

| C3 |

|

|

0.258 |

-0.085 to 0.601 |

0.266 |

-0.075 to 0.606 |

| C4 |

|

|

0.224 |

-0.123 to 0.571 |

0.316 |

-0.032 to 0.664 |

| C5 |

|

|

0.035 |

-0.269 to 0.338 |

0.117 |

-0.187 to 0.421 |

| C6 |

|

|

0.142 |

-0.257 to 0.541 |

0.134 |

-0.262 to 0.53 |

| Supervisor role [0=No] |

|

|

-0.031 |

-0.232 to 0.17 |

-0.036 |

-0.236 to 0.163 |

| Having children [0=No] |

|

|

-0.187 |

-0.38 to 0.005 |

-0.184 |

-0.375 to 0.007 |

| SF-12 MCS |

|

|

-0.038*** |

-0.049 to -0.026 |

-0.038*** |

-0.049 to -0.027 |

| SF-12 PCS |

|

|

-0.010 |

-0.026 to 0.006 |

-0.010 |

-0.026 to 0.006 |

| Temperature |

|

|

|

|

-0.030*** |

-0.045 to -0.016 |

| Precipitation |

|

|

|

|

-0.003 |

-0.006 to 0.000 |

| Sunshine Duration |

|

|

|

|

0.004 |

-0.006 to 0.015 |

| Marginal R2 |

0.000 |

0.107 |

0.114 |

| ICC |

0.370 |

Table 11.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting night recovery. Night recovery is measured as percentage from 0 (no recovery) to 100 (maximum recovery). Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold. *;**;*** MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

Table 11.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting night recovery. Night recovery is measured as percentage from 0 (no recovery) to 100 (maximum recovery). Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold. *;**;*** MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

| |

Night Recovery |

| |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

| |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

| Intercept |

58.277*** |

55.438 to 61.117 |

56.490*** |

45.6 to 67.379 |

58.948*** |

47.438 to 70.459 |

| Age |

|

|

-0.163 |

-0.497 to 0.17 |

-0.166 |

-0.500 to 0.167 |

| Sex [0=Female] |

|

|

4.482 |

-1.813 to 10.777 |

4.479 |

-1.825 to 10.783 |

| Company |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C2 |

|

|

2.459 |

-9.081 to 13.998 |

2.797 |

-8.771 to 14.364 |

| C3 |

|

|

3.754 |

-7.04 to 14.548 |

4.139 |

-6.674 to 14.951 |

| C4 |

|

|

0.894 |

-10.027 to 11.816 |

1.523 |

-9.497 to 12.544 |

| C5 |

|

|

-0.579 |

-10.13 to 8.971 |

0.056 |

-9.578 to 9.691 |

| C6 |

|

|

0.727 |

-11.833 to 13.286 |

0.810 |

-11.767 to 13.386 |

| Supervisor role [0=No] |

|

|

1.535 |

-4.781 to 7.85 |

1.587 |

-4.738 to 7.912 |

| Having children [0=No] |

|

|

-4.411 |

-10.463 to 1.641 |

-4.425 |

-10.485 to 1.635 |

| SF-12 MCS |

|

|

0.194 |

-0.167 to 0.555 |

0.190 |

-0.172 to 0.552 |

| SF-12 PCS |

|

|

-0.048 |

-0.546 to 0.449 |

-0.059 |

-0.557 to 0.439 |

| Temperature |

|

|

|

|

-0.125 |

-0.531 to 0.281 |

| Precipitation |

|

|

|

|

0.015 |

-0.078 to 0.109 |

| Sunshine Duration |

|

|

|

|

-0.301* |

-0.597 to -0.004 |

| Marginal R2 |

0.000 |

0.024 |

0.027 |

| ICC |

0.373 |

Table 12.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting daily kilometers in active mobility (cycling, running, walking). Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold. *;**;*** MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

Table 12.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting daily kilometers in active mobility (cycling, running, walking). Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold. *;**;*** MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

| |

Active Mobility Distance [km] |

| |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

| |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

| Intercept |

2.774*** |

2.255 to 3.292 |

1.766 |

-0.097 to 3.629 |

1.38 |

-0.651 to 3.412 |

| Age |

|

|

0.103*** |

0.046 to 0.161 |

0.104*** |

0.047 to 0.161 |

| Sex [0=Female] |

|

|

1.131* |

0.052 to 2.21 |

1.139* |

0.065 to 2.213 |

| Company [0=C1] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C2 |

|

|

-0.203 |

-2.180 to 1.775 |

-0.293 |

-2.264 to 1.679 |

| C3 |

|

|

0.715 |

-1.130 to 2.560 |

0.579 |

-1.258 to 2.416 |

| C4 |

|

|

-0.808 |

-2.675 to 1.060 |

-1.015 |

-2.898 to 0.869 |

| C5 |

|

|

1.648* |

0.015 to 3.281 |

1.457 |

-0.189 to 3.104 |

| C6 |

|

|

-0.800 |

-2.948 to 1.348 |

-0.841 |

-2.979 to 1.296 |

| Supervisor role [0=No] |

|

|

-0.305 |

-1.386 to 0.775 |

-0.327 |

-1.403 to 0.748 |

| Having children [0=No] |

|

|

-0.308 |

-1.347 to 0.730 |

-0.306 |

-1.339 to 0.727 |

| SF-12 MCS |

|

|

0.030 |

-0.032 to 0.092 |

0.030 |

-0.032 to 0.092 |

| SF-12 PCS |

|

|

0.008 |

-0.078 to 0.093 |

0.010 |

-0.075 to 0.095 |

| Temperature |

|

|

|

|

0.029 |

-0.063 to 0.120 |

| Precipitation |

|

|

|

|

-0.022* |

-0.043 to -0.001 |

| Sunshine Duration |

|

|

|

|

0.062 |

-0.005 to 0.129 |

| Marginal R2 |

0.000 |

0.053 |

0.061 |

| ICC |

0.264 |

Table 13.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting daily kilometers in motor vehicles (car, motorcycle, taxi). Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold. *;**;*** MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

Table 13.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting daily kilometers in motor vehicles (car, motorcycle, taxi). Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold. *;**;*** MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

| |

Motor Vehicle Distance [km] |

| |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

| |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

| Intercept |

30.729*** |

26.893 to 34.564 |

49.26*** |

36.082 to 62.438 |

43.307*** |

28.016 to 58.597 |

| Age |

|

|

0.08 |

-0.327 to 0.486 |

0.091 |

-0.319 to 0.501 |

| Sex [0=Female] |

|

|

3.536 |

-4.117 to 11.189 |

3.672 |

-4.048 to 11.392 |

| Company [0=C1] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C2 |

|

|

-27.850*** |

-41.872 to -13.827 |

-28.948*** |

-43.132 to -14.763 |

| C3 |

|

|

-33.537*** |

-46.564 to -20.509 |

-34.438*** |

-47.592 to -21.284 |

| C4 |

|

|

-29.332*** |

-42.536 to -16.127 |

-31.988*** |

-45.597 to -18.380 |

| C5 |

|

|

-26.410*** |

-37.956 to -14.863 |

-28.794*** |

-40.688 to -16.900 |

| C6 |

|

|

-22.570** |

-37.760 to -7.380 |

-22.722** |

-38.045 to -7.400 |

| Supervisor role [0=No] |

|

|

6.952 |

-0.691 to 14.595 |

6.907 |

-0.803 to 14.618 |

| Having children [0=No] |

|

|

1.634 |

-5.742 to 9.010 |

1.592 |

-5.847 to 9.030 |

| SF-12 MCS |

|

|

-0.104 |

-0.544 to 0.336 |

-0.104 |

-0.548 to 0.340 |

| SF-12 PCS |

|

|

0.200 |

-0.407 to 0.807 |

0.214 |

-0.398 to 0.826 |

| Temperature |

|

|

|

|

0.628 |

-0.205 to 1.461 |

| Precipitation |

|

|

|

|

-0.112 |

-0.306 to 0.081 |

| Sunshine Duration |

|

|

|

|

0.194 |

-0.420 to 0.807 |

| Marginal R2 |

0.000 |

0.059 |

0.062 |

| ICC |

0.172 |

Table 14.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting daily kilometers in public transportation (bus, train, tram). Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold. *;**;*** MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

Table 14.

Results of empty model, socio-demographics model, and weather model predicting daily kilometers in public transportation (bus, train, tram). Significant coefficients are highlighted in bold. *;**;*** MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

| |

Public Transport Distance [km] |

| |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

| |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

Coef. |

CI |

| Intercept |

9.144*** |

7.028 to 11.26 |

3.300 |

-4.914 to 11.513 |

3.149 |

-6.301 to 12.598 |

| Age |

|

|

0.172 |

-0.081 to 0.426 |

0.171 |

-0.081 to 0.423 |

| Sex [0=Female] |

|

|

1.533 |

-3.238 to 6.303 |

1.441 |

-3.310 to 6.193 |

| Company [0=C1] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C2 |

|

|

4.707 |

-4.034 to 13.448 |

4.992 |

-3.738 to 13.722 |

| C3 |

|

|

4.267 |

-3.853 to 12.387 |

4.578 |

-3.514 to 12.67 |

| C4 |

|

|

5.637 |

-2.594 to 13.868 |

6.596 |

-1.783 to 14.974 |

| C5 |

|

|

12.430** |

5.233 to 19.627 |

13.173*** |

5.853 to 20.494 |

| C6 |

|

|

0.376 |

-9.092 to 9.843 |

0.47 |

-8.957 to 9.896 |

| Supervisor role [0=No] |

|

|

-0.447 |

-5.212 to 4.317 |

-0.422 |

-5.166 to 4.322 |

| Having children [0=No] |

|

|

-2.993 |

-7.591 to 1.605 |

-2.963 |

-7.541 to 1.615 |

| SF-12 MCS |

|

|

0.064 |

-0.211 to 0.338 |

0.069 |

-0.204 to 0.343 |

| SF-12 PCS |

|

|

-0.706*** |

-1.085 to -0.328 |

-0.703*** |

-1.079 to -0.326 |

| Temperature |

|

|

|

|

-0.178 |

-0.700 to 0.344 |

| Precipitation |

|

|

|

|

0.123* |

0.002 to 0.244 |

| Sunshine Duration |

|

|

|

|

0.191 |

-0.194 to 0.575 |

| Marginal R2 |

0.000 |

0.042 |

0.044 |

| ICC |

0.124 |