1. Introduction

Climate change has emerged as one of the most pressing global challenges of the 21st century, with rising ambient temperatures and extreme heat events posing direct threats to human health, safety, and productivity [

1,

2,

3]. A growing body of evidence shows that heat exposure is not only a physiological hazard but also a psychosocial and mental health risk factor, affecting stress, mood, cognitive performance, and accident rates [

4,

5,

6]. While the literature has traditionally emphasized the physical consequences of heat, recent reviews underscore the relevance of psychological and behavioral dimensions of occupational heat strain [

7,

8].

In Brazil, the challenges are compounded by rapid urban warming, demographic inequalities, and a large share of outdoor and precarious work [

9,

10]. Informal and self-employed delivery workers are particularly vulnerable, as they often operate under extreme heat without institutional protection, stable labor contracts, or adequate occupational safety measures [

11,

12]. These workers have become emblematic of the platform economy, marked by intense labor demands, low wages, and high turnover. Studies show that delivery riders and drivers typically work long shifts that frequently exceed 49–60 hours per week, with a significant portion reporting more than 60 hours, conditions far above the national average for self-employed workers [

13,

14]. Despite such workloads, their average monthly income remains well below national standards, hovering around R

$1,600 for app-based couriers—more than R

$1,000 below the national average. Moreover, less than one quarter of these workers contribute to social security, compared to nearly half of non-platform delivery workers, reflecting both structural vulnerability and the erosion of formal employment in the sector.

The rise of platform-mediated labor has thus been accompanied by a broader process of precarization, in which algorithmic management controls task allocation, pricing, and even working hours, while sustaining a discourse of autonomy and entrepreneurship. In practice, the majority of app-based drivers and riders report little control over pay, clients, or schedules, as their activities are heavily influenced by digital platforms through penalties, incentives, and suggested shifts [

13,

15,

16]. This contradiction has been described as an “illusion of autonomy,” masking the subordination and heightened risks faced by these workers [

17].

Heat is traditionally classified as a physical hazard within occupational health, yet it can also acquire a psychosocial dimension when combined with precarious working arrangements such as those experienced by delivery workers. In this field, psychosocial risk factors are defined as the organizational and social conditions of work that affect health, well-being, and performance, including aspects such as excessive workloads, low autonomy, and job insecurity [

18]. The interaction between environmental exposure and structural features of platform-mediated labor, including long shifts, income insecurity, algorithmic control, and limited recovery opportunities, transforms heat into a dual risk factor: both a physiological stressor and a psychosocial stressor. Importantly, this transformation does not occur in a vacuum but is shaped by deep social inequalities [

2,

10,

19].

Although heat exposure has been consistently linked to declines in productivity and increases in accidents, absenteeism, and morbidity [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25], empirical evidence on its psychological impacts in informal urban labor markets remains limited. Controversies remain about the magnitude of mental health effects, with some studies reporting strong associations between temperature and mental distress [

6,

26], while others emphasize socioeconomic vulnerabilities as the primary determinants of risk [

27,

28]. Moreover, most of the current research has focused on formal occupational groups such as construction or agriculture [

29,

30], leaving urban gig workers understudied despite their critical exposure profile.

The present pilot study addresses this gap by investigating the effects of climate-related heat exposure on psychological outcomes among self-employed delivery workers in Brasília, Brazil. This group provides a unique case for examining how informal labor, precarious conditions, and climate stressors intersect to shape occupational health risks. By combining daily environmental measurements with repeated self-reports of stress, fatigue, and mood, this study demonstrates that even modest increases in temperature are associated with measurable deterioration in psychological well-being.

2. Materials and Methods

This pilot study adopted a repeated-measures observational design using ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to examine the effects of climate-related heat exposure on psychological outcomes among self-employed delivery workers in Brasília, Brazil. EMA is a method that samples participants’ experiences in real time and in their natural environments, minimizing recall bias and capturing within-person fluctuations across the day. We operationalized EMA by sending automated mobile prompts twice daily—at 12:00 and 18:00 local time—over 15 consecutive days in August 2025 (Brasília’s dry season).

A total of 45 motorcycle couriers were initially recruited through community networks of couriers operating with food and parcel delivery platforms; 30 (66.7%) completed the full protocol and were included in the analyses. At each EMA prompt, participants completed brief self-reports rating stress (1 = not stressed to 5 = extremely stressed), fatigue (1 = not tired to 5 = extremely tired), mood (1 = very positive to 5 = very negative), and perceived heat strain (1 = not hot to 5 = extremely hot), and they reported the kilometers traveled since the previous prompt.

We opted not to use composite heat stress indices such as the Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT), the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI), the Predicted Mean Vote (PMV), or the Thermal Sensation Vote (TSV) because our objective was not to estimate biophysical strain under controlled conditions, but rather to capture how workers themselves experience heat in real-world contexts. These indices, while valuable in occupational hygiene and ergonomics, often require instrumentation, microclimatic monitoring, or metabolic assumptions that are difficult to implement in informal and highly mobile work settings such as motorcycle delivery. EMA, by contrast, allowed us to combine meteorological station data with workers’ subjective perceptions and psychological states, generating a context-sensitive dataset that reflects both environmental exposure and lived experience. This approach aligns with the study’s focus on psychosocial risk, prioritizing the intersection between physical conditions and psychosocial strain in precarious labor markets.

Environmental variables were obtained from the Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia (INMET) through the official Brasília meteorological station (

https://portal.inmet.gov.br/). For each day and time point, corresponding values of temperature (°C), relative humidity (%), and barometric pressure (hPa) were extracted from the INMET dataset and paired with the participants’ self-reports. This ecological momentary assessment design yielded 900 observations (30 workers × 15 days × 2 prompts), providing repeated within-person measures across varying thermal conditions.

Associations between temperature and psychological outcomes were tested using linear regression models estimated separately for each dependent variable, with cluster-robust standard errors by participant to account for the non-independence of repeated measures. Humidity and barometric pressure were evaluated as covariates but did not materially change the estimates and were omitted from the final models for parsimony. Results are presented as unstandardized coefficients with 95% confidence intervals and two-tailed p-values. Analyses were conducted in R (version 4.5.1).

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Centro Universitário de Brasília (Approval Code: 89798625.0.0000.0023) and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. The dataset, statistical code, and survey protocols are openly available at the Open Science Framework (OSF):

https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/Y6HDC.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

A total of 30 delivery workers completed the 15-day protocol, yielding 900 repeated assessments. During the observation window, environmental conditions paired to each prompt showed marked variability, with mean temperature of 23.25 °C (SD = 3.99; range = 16.8–28.5), mean relative humidity of 39.10% (SD = 13.73; range = 19–71), and average daily distance traveled of 72.96 km (SD = 16.41; range = 45–100) (

Table 1). Psychological outcomes also displayed heterogeneity across repeated self-reports: average stress was 3.85 (SD = 1.24), fatigue 3.81 (SD = 1.29), mood 3.04 (SD = 1.40; higher values indicate worse mood), and perceived heat strain 3.95 (SD = 1.00), all on a 1–5 scale (

Table 1).

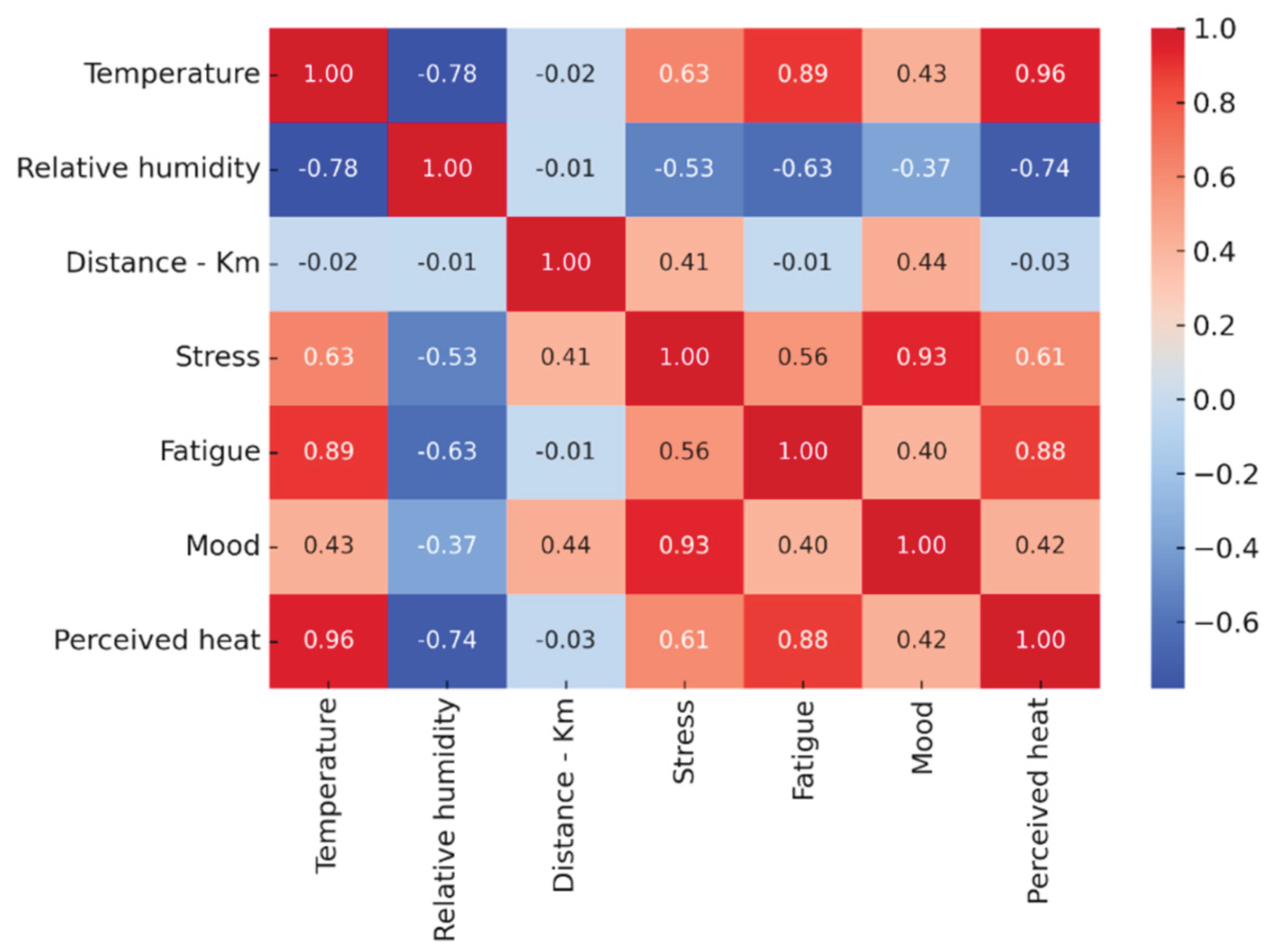

Correlation analyses indicated associations between environmental variables and psychological outcomes. Higher temperature was positively correlated with stress (r = .63), fatigue (r = .89), mood deterioration (r = .43), and perceived heat strain (r = .96), all p < .001. Conversely, humidity was inversely related to all outcomes, including stress (r = –.53), fatigue (r = –.63), mood (r = –.37), and perceived heat strain (r = –.74), all p < .001. Temperature and humidity were themselves strongly negatively correlated (r = –.78, p < .001), consistent with Brasília’s dry-season pattern (

Figure 1).

Regression models with temperature as the sole predictor confirmed sizable associations with psychological outcomes. Each 1 °C increase was associated with higher stress (β = 0.196, 95% CI [0.179, 0.213], p < .001), greater fatigue (β = 0.289, 95% CI [0.284, 0.295], p < .001), and poorer mood (β = 0.149, 95% CI [0.130, 0.168], p < .001). Model fit was strongest for fatigue (R² = .800), followed by stress (R² = .395) and mood (R² = .181).

When relative humidity was included alongside temperature, model fit improved slightly and partial effects emerged that diverged from bivariate correlations, reflecting the strong negative collinearity between temperature and humidity (

Table 2). Controlling for temperature, higher humidity was associated with lower stress (β = –0.010, 95% CI [–0.017, –0.004], p = .002) and better mood (β = –0.011, 95% CI [–0.019, –0.003], p = .007), but with greater fatigue (β = 0.016, 95% CI [0.013, 0.020], p < .001). These models accounted for 40.0% of the variance in stress, 81.2% in fatigue, and 18.6% in mood.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that temperature is the dominant predictor across outcomes, whereas humidity exerts modest but statistically reliable partial effects. Specifically, humidity contributes an incremental ΔR² of approximately .005–.012 depending on the outcome. The findings are robust to clustering by participant and align with the descriptive patterns observed, supporting the interpretation that daily heat exposure represents a salient psychosocial risk factor in this worker population.

4. Discussion

In this study higher ambient temperature was consistently associated with worsening psychological outcomes among delivery workers in Brasília, with particularly strong effects on fatigue and robust estimates when clustering by participant. When relative humidity was included in the models, temperature remained the dominant predictor, while humidity showed small but statistically reliable partial effects (protective for stress and mood but adverse for fatigue) reflecting the strong dry-season collinearity between the two variables. These findings underscore heat exposure as a significant psychosocial risk in precarious platform-based outdoor work.

Our findings align with reviews showing that occupational heat strain compromises health, cognition, and productivity [

1,

5,

7,

8] and extend meta-analytic evidence that ambient heat is linked to mental health outcomes [

2,

6]. The especially strong temperature–fatigue relationship is consistent with thermoregulatory load and cardiovascular strain under heat, which elevate perceived exertion and deplete resources over a shift [

5,

7]. The positive association between temperature and mood deterioration and stress coheres with literature connecting heat to irritability, sleep disturbance, and affective dysregulation [

6], while also echoing economic and safety impacts documented in workplaces exposed to heat [

4,

21,

24].

The mixed partial role of humidity (protective for stress and mood but adverse for fatigue)likely reflects (i) suppression effects from the strong inverse temperature–humidity correlation in Brasília’s dry season and (ii) distinct biophysical channels: higher humidity reduces evaporative cooling, intensifying physiological fatigue at a given air temperature, even as slightly cooler, more humid afternoons/evenings may correspond to less psychologically aversive conditions (e.g., less desiccation, dust) and different task composition. This nuance mirrors ergonomics frameworks that integrate temperature and moisture (e.g., WBGT/UTCI), where identical temperatures can impose different total heat loads as humidity varies [

26,

29].

Brazil’s urban warming and social inequalities amplify heat risk [

9,

10]. Delivery workers face prolonged outdoor exposure, traffic hazards, and limited institutional protection. The platformization of work in Brazil has been accompanied by longer working hours, unstable earnings, and low social security coverage [

11,

12,

13]. Evidence from Brazil and elsewhere indicates precarization and algorithmic control over schedules and pay, which can compress rest breaks and encourage risk-taking under heat [

13,

14,

16]. These structural pressures plausibly magnify the psychological burden of heat documented here and may help explain the large fatigue effects we observe.

The intersection with road safety is critical. Heat has been linked to higher crash risk and severity [

25], including among motorcyclists [

23] and on extreme hot days [

22]. In a workforce that travels long distances daily, heat-related fatigue, irritability, and diminished attention may translate into elevated crash risk—adding a public safety dimension to what is often treated as a workplace comfort issue.

Brazil-specific studies highlight current and future risks of occupational heat exposure [

20,

29] and broader morbidity patterns under heat [

3,

9]. International syntheses show robust links to productivity loss and injuries [

4,

5,

21,

24]. Our contribution is to document within-person psychological deterioration in a contemporary, urban gig workforce – a population underrepresented in the literature that often focuses on agriculture and construction [

29,

30]. While some argue socioeconomic factors dominate heat–health associations [

27,

28], our design demonstrates that day-to-day thermal variation explains meaningful within-worker variation in stress, fatigue, and mood (over and above structural disadvantage)pointing to both proximal (heat) and distal (precarity) levers for intervention.

Policy and Practice Implications

Our results argue for multi-layered adaptation spanning urban planning, public health, and platform design:

Limitations should temper inference. First, weather was measured at the station level; microclimates along routes (e.g., urban heat islands, radiant load, wind) were not directly captured, potentially biasing point estimates toward the null or introducing exposure misclassification. Second, outcomes were self-reported; although EMA reduces recall bias, common-method variance and expectancy effects remain possible. Third, selection and completion: 45 were recruited and 30 completed the protocol; differential attrition could bias estimates if non-completers differed systematically. Fourth, time-of-day and workload composition (e.g., mid-day vs. evening, traffic cycles) might confound associations; although cluster-robust SEs address non-independence, future models should incorporate time-fixed effects, distance traveled, and shift-level characteristics. Fifth, strong temperature–humidity collinearity in the dry season complicates estimation of independent humidity effects; non-linear and interaction terms (e.g., temperature × humidity) and heat-stress indices could yield more interpretable parameters. Finally, causality cannot be established in an observational design; however, the magnitude and consistency of within-worker associations are noteworthy and align with mechanistic plausibility.

Future research, priority directions include:

High-resolution exposure: wearable sensors for personal temperature, humidity, radiant load, sweat rate, and heart rate; integration with route-level microclimate mapping.

Advanced modeling: multilevel mixed models, generalized additive models for nonlinearity/thresholds, and distributed-lag structures to quantify delayed effects.

Psychophysics tests: directly compare linear, logarithmic (Fechner), and power-law (Stevens) mappings for perceived heat vs. temperature, and assess mediation of stress, mood, and fatigue by perceived heat.

Indices & interventions: evaluate WBGT/UTCI triggers for automated platform nudges, randomized hydration/shade/rest protocols, and algorithmic throttling during heatwaves.

External outcomes: link EMA to crash/near-miss reports and platform telematics to quantify safety implications under heat.

Comparative contexts: replicate across seasons, cities, and platform types (motorcycle, bicycle, e-bike) and examine heterogeneity by socioeconomic status and social protection.

5. Conclusions

In a precarious, platform-mediated workforce central to urban logistics, even modest daily increases in temperature are associated with measurable deterioration in psychological well-being, especially fatigue. Humidity exerts smaller, directionally mixed partial effects that merit modeling with heat-stress indices and non-linear terms. Given accelerating warming and the growth of platform work, protecting delivery workers will require integrated public-health, regulatory, and platform-design responses that reduce heat exposure, enable recovery, and strengthen social protection.

6. Patents

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.L.R.; methodology, C.M.L.R. and L.A.G.C.; software, C.M.L.R.; validation, C.M.L.R. and L.A.G.C.; formal analysis, C.M.L.R.; investigation, L.A.G.C.; resources, C.M.L.R.; data curation, L.A.G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.L.R.; writing—review and editing, C.M.L.R. and L.A.G.C.; visualization, C.M.L.R.; supervision, C.M.L.R.; project administration, C.M.L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Centro Universitário de Brasília (protocol code 89798625.0.0000.0023, date of approval: 01 March 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the participating delivery workers for their time and commitment. The authors also thank the University Center of Brasília (CEUB) for institutional support throughout the study. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI) for grammatical review. The authors have reviewed and edited all content and take full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EMA |

Ecological Momentary Assessment |

| INMET |

Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia |

| WGBT |

Wet Bulb Globe Temperature |

| UTCI |

Universal Thermal Climate Index |

| PMV |

Predicted Mean Vote |

| TSV |

Thermal Sensation Vote |

References

- Levy, B.S.; Roelofs, C. Impacts of Climate Change on Workers’ Health and Safety. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health; Oxford University Press, 2019 ISBN 978-0-19-063236-6.

- Thompson, R.; Hornigold, R.; Page, L.; Waite, T. Associations between High Ambient Temperatures and Heat Waves with Mental Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Public Health 2018, 161, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, R.; Ye, T.; Yu, W.; Yu, P.; Chen, Z.; Mahendran, R.; Saldiva, P.H.N.; Coel, M.D.S.Z.S.; Guo, Y.; et al. Heat Exposure and Hospitalisation for Epileptic Seizures: A Nationwide Case-Crossover Study in Brazil. Urban Climate 2023, 49, 101497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faurie, C.; Varghese, B.M.; Liu, J.; Bi, P. Association between High Temperature and Heatwaves with Heat-Related Illnesses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 852, 158332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flouris, A.D.; Dinas, P.C.; Ioannou, L.G.; Nybo, L.; Havenith, G.; Kenny, G.P.; Kjellstrom, T. Workers’ Health and Productivity under Occupational Heat Strain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Lancet Planetary Health 2018, 2, e521–e531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.; Lawrance, E.L.; Roberts, L.F.; Grailey, K.; Ashrafian, H.; Maheswaran, H.; Toledano, M.B.; Darzi, A. Ambient Temperature and Mental Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Lancet Planetary Health 2023, 7, e580–e589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, L.G.; Foster, J.; Morris, N.B.; Piil, J.F.; Havenith, G.; Mekjavic, I.B.; Kenny, G.P.; Nybo, L.; Flouris, A.D. Occupational Heat Strain in Outdoor Workers: A Comprehensive Review and Meta-Analysis. Temperature 2022, 9, 67–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, Y.H.; Choi, W.-J.; Ham, S.; Kang, S.-K.; Yoon, J.-H.; Yoon, M.J.; Kang, M.-Y.; Lee, W. Heat Exposure and Workers’ Health: A Systematic Review. Reviews on Environmental Health 2022, 37, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, B.F.A.D.; Jacobson, L.D.S.V.; Perez, L.P.; Silveira, I.H.D.; Junger, W.L.; Hacon, S.D.S. Impacts of Heat Stress Conditions on Mortality from Respiratory and Cardiovascular Diseases in Brazil. SustDeb 2020, 11, 297–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.M.D.; Libonati, R.; Garcia, B.N.; Geirinhas, J.L.; Salvi, B.B.; Lima E Silva, E.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Peres, L.F.; Russo, A.; Gracie, R.; et al. Twenty-First-Century Demographic and Social Inequalities of Heat-Related Deaths in Brazilian Urban Areas. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0295766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abilio, L.C.; Grohmann, R.; Weiss, H.C. Struggles of Delivery Workers in Brazil: Working Conditions and Collective Organization during the Pandemic. J. Labor Soc. 2021, 24, 598–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.B.D. Motoboys in São Paulo, Brazil: Precarious Work, Conflicts and Fatal Traffic Accidents by Motorcycle. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives 2020, 8, 100261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, S.S.D.; Nogueira, M.O. Plataformização e Precarização Do Trabalho de Motoristas e Entregadores No Brasil. BMT 2024, 30, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, P.; Kougiannou, N.K.; Clark, I. Informalization in Gig Food Delivery in the UK: The Case of Hyper-Flexible and Precarious Work. Industrial Relations 2023, 62, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abílio, L.C.; Amorim, H.; Grohmann, R. Uberização e Plataformização Do Trabalho No Brasil: Conceitos, Processos e Formas. Sociologias 2021, 23, 26–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Huerta, E.; Leão, L.H.D.C.; Landman, T. Climate Change, Decent Work and Workers’ Health in Brazil: Theoretical Considerations. Rev. bras. saúde ocup. 2025, 50, eddsst12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.-C. No enxame: perspectivas do digital; Editora Vozes, 2021; ISBN 978-85-326-5977-4.

- Rodrigues, C.M.L.; Faiad, C.; Facas, E.P. Fatores de Risco e Riscos Psicossociais No Trabalho: Definição e Implicações. Psic.: Teor. e Pesq. 2020, 36, e36nspe19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortum, E.; Leka, S.; Cox, T. Psychosocial Risks and Work-Related Stress in Developing Countries: Health Impact, Priorities, Barriers and Solutions. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health 2010, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitencourt, D.P.; Alves Maia, P.; Cauduro Roscani, R. The Heat Exposure Risk to Outdoor Workers in Brazil. Archives of Environmental & Occupational Health 2020, 75, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S.H.; Rothmore, P.; Giles, L.C.; Varghese, B.M.; Bi, P. Extreme Heat and Occupational Injuries in Different Climate Zones: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Epidemiological Evidence. Environment International 2021, 148, 106384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.; Peng, B.; Xin, Y. Higher Traffic Crash Risk in Extreme Hot Days? A Spatiotemporal Examination of Risk Factors and Influencing Features. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2025, 116, 105045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-K. Heat-Induced Risks of Road Crashes among Older Motorcyclists: Evidence from Three Motorcycle-Dominant Cities in Taiwan. Journal of Transport & Health 2024, 35, 101754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, M.C.; Brewer, G.J.; Williams, W.J.; Quinn, T.; Casa, D.J. Impact of Occupational Heat Stress on Worker Productivity and Economic Cost. American J Industrial Med 2021, 64, 981–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.Y.H.; Zaitchik, B.F.; Gohlke, J.M. Heat Waves and Fatal Traffic Crashes in the Continental United States. Accident Analysis & Prevention 2018, 119, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, G.N.; Dos Santos, G.C.; Ossani, P.C.; Leal, G.C.L.; Galdamez, E.V.C. Analysis of the Climate Impact on Occupational Health and Safety Using Heat Stress Indexes. IJERPH 2025, 22, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ireland, A.; Johnston, D.; Knott, R. Heat and Worker Health. Journal of Health Economics 2023, 91, 102800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, P.; Jha, V. Heat Stress: A Hazardous Occupational Risk for Vulnerable Workers. Kidney International Reports 2023, 8, 1283–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitencourt, D.P.; Maia, P.A.; Ruas, Á.C.; Cunha, I.D.Â.D. Outdoor Work: Past, Present, and Future on Occupational Heat Exposure. Rev. bras. saúde ocup. 2023, 48, edcinq13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjgna, K.; Sharareh, K.; Apurva, P. Impact Analysis of Heat on Physical and Mental Health of Construction Workforce. In International Conference on Transportation and Development 2022; Proceedings; 2022; pp. 290–298.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).