Submitted:

09 September 2025

Posted:

11 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. The Cultural and Agricultural Wealth of Tlaxiaco

3.2. Circular Economy in Practice

3.3. Empowering Communities Through Education and Artificial Intelligence

3.4. Toward Experiential and Culinary Tourism

3.5. Experiential, Sustainable, and Regenerative Tourism Based on Local Culture

4. Discussion

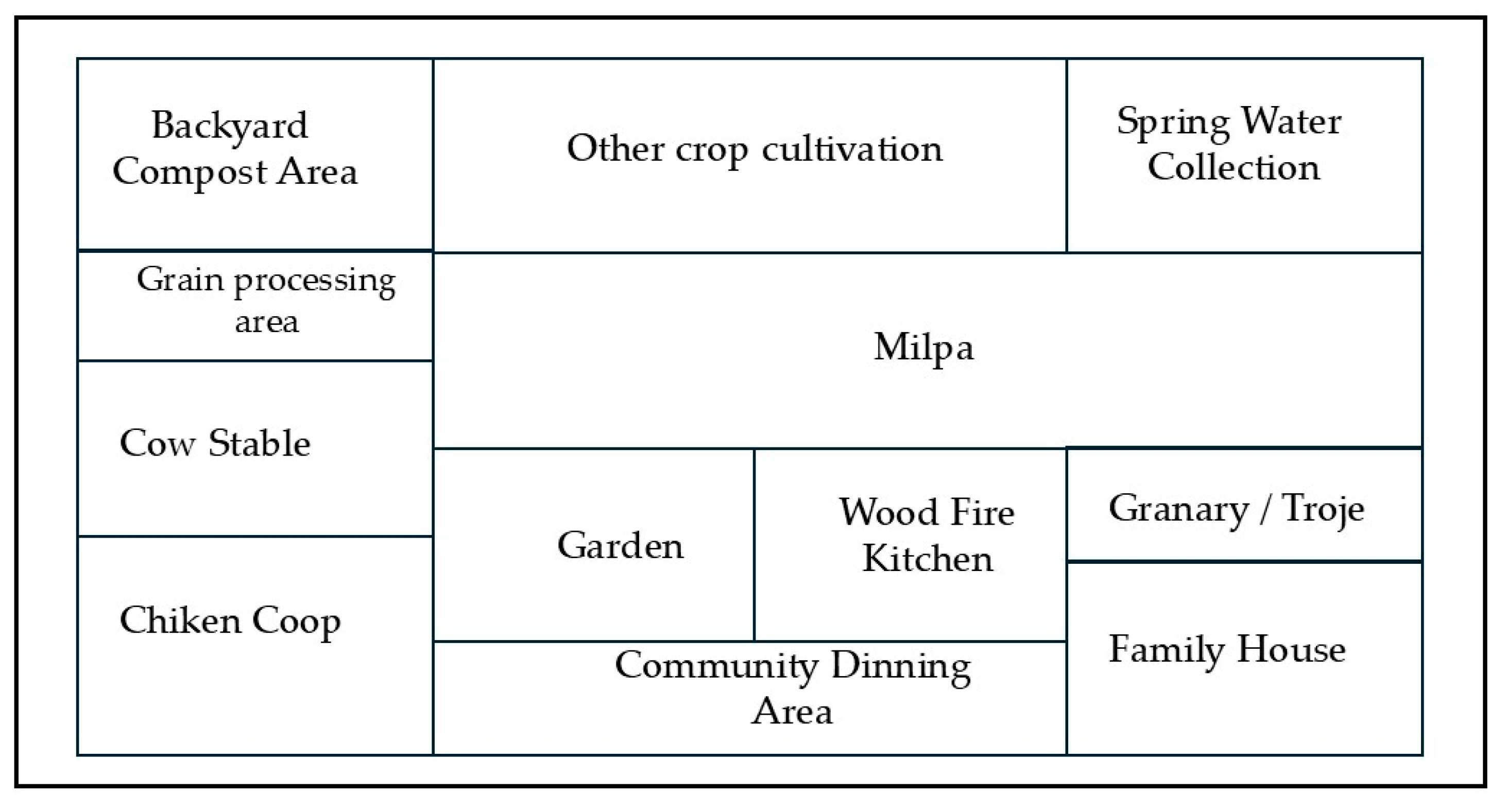

Description of the Components of a Self-Sufficient, Agroecological, and Culturally Rooted Farm in Tlaxiaco

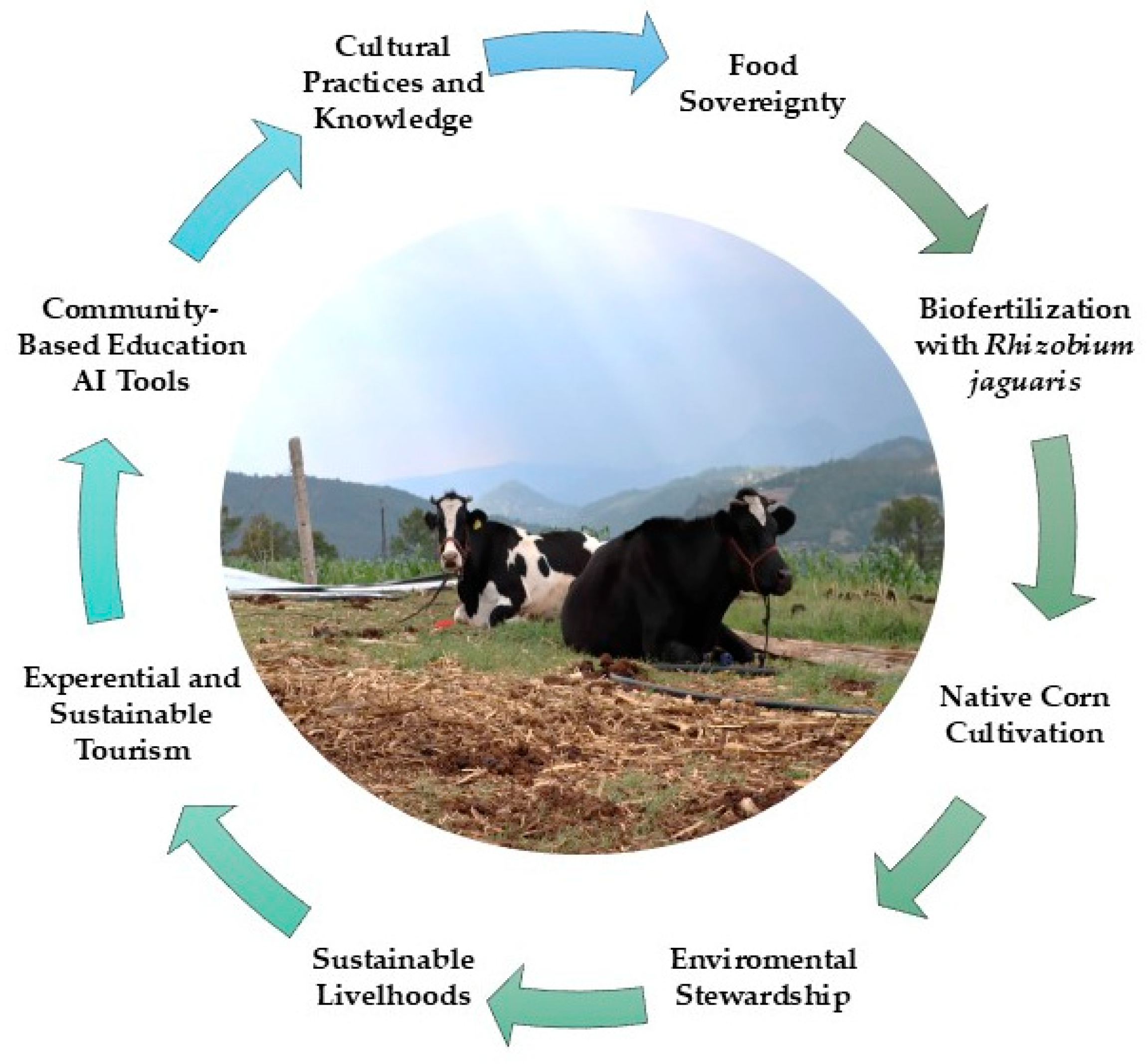

Description of a Circular Model in Experiential and Sustainable Tourism

5. Conclusions

5.1. Limitations and Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| NODESS | Nodos de Economía Social y Solidaria |

| IT | Instituto Tecnológico |

| PROBIOTEC | Red de Investigación de Probióticos Vegetales Rizobianos |

| RIESS | Red de Investigación de Economía Social y Solidaria |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| TecNM | Tecnológico Nacional de México |

| VLR | Voluntary Local Review |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1 Field Notebook

Appendix B

References

- Dirzo, R.; Brodhead, A.; Gregory, H. Bio-cultural diversity and community-based conservation in Oaxaca. Stanford Report, Available online: https://bosp.stanford.edu/explore/short-term-programs/bio-cultural-diversity-oaxaca ( accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Reyes-Santiago, M. R.; Méndez-García, E.; Sánchez-Medina, P. S. “A Mixed Methods Study on Community-Based Tourism as an Adaptive Response to Water Crisis in San Andrés Ixtlahuaca, Oaxaca, Mexico.” Sustainability 2022, 14, 5933.

- García-Padilla, E.; DeSantis, D.L.; Rocha, A.; Fucsko, L.A.; Johnson, J.D.; Lazcano-Villarreal, D. Biological and Cultural Diversity in the State of Oaxaca, Mexico: Strategies for Conservation among Indigenous Communities. Biol. Soc. 2022, 5, 48–72. [CrossRef]

- Leigh, D.S.; Kowalewski, S.A.; Holdridge, G. 3400 Years of Agricultural Engineering in Mesoamerica: Lama-Bordos of the Mixteca Alta, Oaxaca, Mexico. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2013, 40, 2061–2072. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Aguilar, J.A.; Durán, E.; Cortina-Villar, H.S.; Velázquez, A. Landscape Approach to Support Regional Action in Communal Forest Management: The Case of the Mixteca Alta, Oaxaca, Mexico. Investigaciones Geográficas 2022, 109, 106–127. [CrossRef]

- Schmal, J. The Mixtecs and Zapotecs: Two Enduring Cultures of Oaxaca. Indigenous Mexico. Available online: https://www.indigenousmexico.org/articles/the-mixtecs-and-zapotecs-two-enduring-cultures-of-oaxaca (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- One Earth. Sierra Madre del Sur Pine-Oak Forests. Available online: https://www.oneearth.org/ecoregions/sierra-madre-del-sur-pine-oak-forests/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Phillips, T. Fewer wildfires, great biodiversity: what is the secret to the success of Mexico’s forests? The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2024/may/01/fewer-wildfires-great-biodiversity-what-is-the-secret-to-the-success-of-mexicos-forests (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Cagle, N. Wildlife & Forest Management in Oaxaca: Prioritizing Biodiversity and Connectivity in Indigenous Communities of Oaxaca, Mexico. Available online: https://sites.nicholas.duke.edu/nicolettecagle/cagle-lab/applied-conservation-ecology/wildlife-forest-management-in-oaxaca/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- De Ávila, A. Mixtec Plant Nomenclature and Classification. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, Fall 2010. https://escholarship.org/content/qt4pp843br/.

- Geoparque Mundial UNESCO Mixteca Alta. Patrimonio. Available online: https://geoparquemixtecaalta.org/patrimonio/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Olivera, M. Notas sobre las actividades religiosas en Tlaxiaco. Anales del Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia 1982, 17, 129–151. Available online: https://revistas.inah.gob.mx/index.php/anales/article/view/7226/8069 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Ávila-Quiroz Mijangos, B.; Pérez-León, M.I.; Nahmad-Sitton, S. Ñiviñuun, Gente del Pueblo. La autoidentificación de un poblado mixteco en la costa de Oaxaca. Intersticios Sociales 2021, 12(23), 1–30. Available online: https://www.intersticiossociales.com/index.php/is/article/view/232/Versi%C3%B3n%20Final (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Hernández Rodríguez, G.M.E.; Mariaca Méndez, R.; Vásquez Sánchez, M.Á.; Eroza Solana, E. Influencia de la cosmovisión del pueblo mixteco de Pinotepa de Don Luis, Oaxaca, México, en el uso y manejo del caracol púrpura, Plicopurpura pansa (Gould, 1853). UNAM–CEPHCIS. Available online: https://investigacion.cephcis.unam.mx/generoyrsociales/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Hern%C3%A1ndez%20Rodr%C3%ADguez%20Griselda%20Ma.%20Eugenia.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Secretaría de Turismo del Estado de Oaxaca. Evaluación de la Vocación Turística: Municipio de Heroica Ciudad de Tlaxiaco, Oaxaca; Gobierno del Estado de Oaxaca, Dirección de Planeación y Desarrollo Turístico, Departamento de Vocaciones Turísticas: Oaxaca, México, 2020. Available online: https://www.oaxaca.gob.mx/sectur/wp-content/uploads/sites/65/2020/01/Heroica-ciudad-de-Tlaxiaco.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Cagle, N. Wildlife & Forest Management in Oaxaca: Prioritizing Biodiversity and Connectivity in Indigenous Communities of Oaxaca, Mexico. Available online: https://sites.nicholas.duke.edu/nicolettecagle/cagle-lab/applied-conservation-ecology/wildlife-forest-management-in-oaxaca/ (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- García Leyva, J. Al rescate de la lengua de la lluvia. Ojarasca. Available online: https://ojarasca.jornada.com.mx/2021/03/13/al-rescate-de-la-lengua-de-la-lluvia-287-1506.html (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- El Diario Mixteca. “Tlaxiaco celebrates with rich black mole, picadillo, and stuffed soup—delicacies during August festivities #Mixteca #SantaMariadelaAsunción.” Available online: https://www.facebook.com/share/p/16jnujSjMB/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Cerveza de Mecate Tlaxiaqueña. Authentic Mecate Beer from Tlaxiaco. Available online: https://cervezademecatetlaxiaco.blogspot.com/2012/09/autentica-cerveza-de-mecate-tlaxiaquena.html (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Vive Tlaxiaco. Mecate Beer and Local Delicacies from Tlaxiaco. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/share/p/196Pziq1aE/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Bueno Sánchez, J.A. Crónicas de Oaxaca: Visita a Tlaxiaco. El Imparcial Oaxaca [online], 16 June 2025. Available online: https://imparcialoaxaca.mx/opinion/cronicas-de-oaxaca-visita-a-tlaxiaco/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Honorable Ayuntamiento de Tlaxiaco. Semana Santa en Tlaxiaco 2025: Demostración artesanal de tejido de fibras vegetales. Tlaxiaco Gobierno Municipal [online], 11 April 2025. Available online: https://tlaxiaco.gob.mx/32/semana-santa-en-tlaxiaco-2025/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Albarrán, A. Tlaxiaco disfruta de sus calendas. El Imparcial de Oaxaca [online], 10 August 2024. Available online: https://imparcialoaxaca.mx/los-municipios/tlaxiaco-disfruta-de-sus-calendas/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Mixtequeando. Calenda en honor al Señor de la Columna. Segundo viernes de Cuaresma en Santa Catarina Yosonotu, Tlaxiaco. Facebook [online video], 2025. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/share/v/18gQaANo6h/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de los Pueblos Indígenas (INPI). Etnografía del pueblo mixteco – Ñuu Savi. Gobierno de México [website], 2018. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/inpi/articulos/etnografia-del-pueblo-mixteco-nuu-savi (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Rieger, I.A. Chameleonic Traditions in the Festive Practices of a Mixtec Transnational Community. Rev. Reflexiones 2019, 98, 111–129. [CrossRef]

- Vive Tlaxiaco. Día de la Samaritana: Una Tradición muy Oaxaqueña. Facebook. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/ViveTlaxiaco/posts/667464355640847/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Echavarria, M. Tejiendo México: El algodón coyuchi en San Juan Colorado y la lana de Teotitlán. Travesías Digital. Available online: https://www.travesiasdigital.com/comercial/tejiendo-mexico-con-lincoln-por-oaxaca-san-juan-colorado-teotitlan-del-valle/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Klein, K. (Ed.). The Unbroken Thread: Conserving the Textile Traditions of Oaxaca; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1997. Available online: https://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/pdf_publications/pdf/unbroken_thread_eng_vl.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Getty Conservation Institute. The Unbroken Thread: Conserving the Textile Traditions of Oaxaca; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, n.d. Available online: https://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/pdf_publications/pdf/unbroken_thread_eng_vl.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- La Brisa De Mi Huerto. Venta de té limón. Facebook. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/groups/765771927644267/posts/1702061110682006/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Municipio de Tlaxiaco. Sabores Tradicionales de Tlaxiaco. Facebook. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/share/v/16osd9v6E3/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- López, R. Prevalece la medicina indígena tradicional en Tlaxiaco. El Imparcial de Oaxaca. Available online: https://imparcialoaxaca.mx/los-municipios/prevalece-la-medicina-indigena-tradicional-en-tlaxiaco/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS). Compromiso cumplido: Tlaxiaco cuenta con nuevo Hospital Rural de IMSS-Bienestar. IMSS Comunicado No. 165/2020. Available online: https://www.imss.gob.mx/prensa/archivo/%20202004/165 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Páez Tinoco, M.C. Unidades de Producción Familiar de Trigo en la Mixteca de Oaxaca. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Tecnológico del Valle de Oaxaca, Oaxaca, Mexico, January 2023. Available online: https://rinacional.tecnm.mx/jspui/bitstream/TecNM/6744/1/TESIS%20MARIA%20CRISTINA%20PAEZ%20TINOCO.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Katz, E.; Vargas, L.A. Cambio y continuidad en la alimentación de los mixtecos. Anales de Antropología 1990, 27, 15–51. Available online: https://www.revistas.unam.mx/index.php/antropologia/article/view/15716 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Delgado Nute, M. Celebrando a las palmeadoras. Fundación Tortilla. Available online: https://fundaciontortilla.org/Cultura/celebrando_a_las_palmeadoras (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Ortega Ortega, T.; Vázquez García, V.; Flores Sánchez, D.; Núñez Espinoza, J.F. Agrobiodiversity, gender and food sovereignty in Tlaxiaco, Oaxaca. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 2017, 8(18), 3897–3910. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez García, V.; Nuñez Espinoza, J.F.; Ortega Ortega, T. Estructura y resiliencia social en comunidades indígenas: el caso de la Unión de Palmeadoras de Tlaxiaco, Oaxaca, México. Redes 2018, 29(2), 206–225. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-López, L.; Zapata-Martelo, E.; Ayala-Carrillo, M.R.; Martínez-Corona, B.; Vázquez-Carrillo, G.; Jacinto-Hernández, C.; Espinosa-Calderón, A. Practical and theoretical knowledge of corn and beans in the Triqui High Region, Oaxaca. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 2018, 9(1), 207–220. [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Pérez, E.N.; Ramírez-Vallejo, P.; Crosby-Galván, M.M.; Estrada-Gómez, J.A.; Lucas-Florentino, B.; Chávez-Servia, J.L. Classification of Native Populations of Common Bean from South-Central Mexico by Seed Morphology. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 2015, 38(1), 29–38. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0187-73802015000100005 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- El Yolomecano. Elaboración del QUESO | población de la Capilla del Carrizal, Tlaxiaco, Oaxaca. YouTube Video, 2 July 2022. Available online: https://youtu.be/2o3gezgaxWk?si=B50uztRYbFwLPSF2 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Mixtequeando. Desde Llano de Guadalupe, Tlaxiaco. Lugar dónde aún se elaboran los ricos quesos criollos. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/share/v/1Embt7QKRe/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- López, R. En Ojo de Agua, Tlaxiaco, logran alimentación sana para sus familias. El Imparcial 2019. Available online: https://imparcialoaxaca.mx/los-municipios/en-ojo-de-agua-tlaxiaco-logran-alimentacion-sana-para-sus-familias/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Hecho en Oaxaca. Guisado de frutas, platillo de salvaguarda en Tlaxiaco. Leche con Tuna 2022. Available online: https://lechecontuna.com/2022/03/04/guisado-de-frutas-platillo-de-salvaguarda-en-tlaxiaco/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Municipio de Tlaxiaco. Mercado: Día de Plaza en Tlaxiaco. 12 August 2023. Available online: https://lechecontuna.com/2023/08/12/dia-de-plaza-en-tlaxiaco/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Maíz Cocina Tradicional. Agua de Chilacayota – bebida tradicional oaxaqueña. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/reel/1644295609673141 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Ayuntamiento de Tlaxiaco. Día de la Samaritana. Available online: https://tlaxiaco.gob.mx/53/dia-de-la-samaritana-2/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Peach, Y. La Mesa del Rincón: Un rincón de tradición en Tlaxiaco. Leche con Tuna. Available online: https://lechecontuna.com/2024/04/25/la-mesa-del-rincon-un-rincon-de-tradicion-en-tlaxiaco/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- El Universal Oaxaca. Huevos de colores de Oaxaca y el origen de su peculiar pigmento. El Universal. Available online: https://oaxaca.eluniversal.com.mx/mas-de-oaxaca/huevos-de-colores-de-oaxaca-y-el-origen-de-su-peculiar-pigmento/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Gobierno del Estado de Oaxaca. Huajuapan de León celebra la Feria del Mezcal de la Mixteca, cuarta edición. Gobierno del Estado de Oaxaca. Available online: https://www.oaxaca.gob.mx/comunicacion/huajuapan-de-leon-celebra-la-feria-del-mezcal-de-la-mixteca-cuarta-edicion/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Vázquez García, V.; Ramírez Castillo, R.; Hernández Juárez, M. Género, clase y etnicidad en la producción de mezcal. Una genealogía familiar en Valles Centrales, Oaxaca. EntreDiversidades 2024, 21, e202403. [CrossRef]

- Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO). Fichas Técnicas de los Agaves de Oaxaca. Proyecto NE012. Available online: http://www.conabio.gob.mx/institucion/proyectos/resultados/NE012_Anexo_Fichas_agave.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Redacción DM. Tlaxiaco vive fiesta de fraternidad. Diario de la Mixteca 2017. Available online: https://www.diariodelamixteca.com/tlaxiaco/tlaxiaco-vive-fiesta-de-fraterniadad.html (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Chávez García, M. La morfogénesis urbana de la Heroica Ciudad de Tlaxiaco, Oaxaca. Anuario de Espacios Urbanos. Historia, Cultura, Diseño 2020, 7, 1–21. Available online: https://espaciosurbanos.azc.uam.mx/index.php/path/article/view/31/650 (accessed on 16 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- VIVE Tlaxiaco. La Samaritana en Tlaxiaco Oaxaca. Facebook. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/ViveTlaxiaco/posts/666574489063167 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Pérez García, C. Así se come en Tlaxiaco. NVI Noticias 2019. Available online: https://www.nvinoticias.com/gastronomia/asi-se-come-en-tlaxiaco/40256 (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Chefs Jaime y Ramiro. Todas las delicias que uno encuentra en el Mercado de Tlaxiaco. YouTube 2022. Available online: https://youtu.be/RhW2BJU14HA (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Secretaría de Economía. Distribución geográfica de remesas en la Heroica Ciudad de Tlaxiaco. Data México 2025. Available online: https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/es/profile/geo/heroica-ciudad-de-tlaxiaco#remittances (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Lugo-Espinosa, G., Acevedo-Ortiz, M. A., Aquino-Bolaños, T., Ortiz-Hernández, Y. D., Ortiz-Hernández, F. E., Pérez-Pacheco, R., & López-Cruz, J. Y. (2024). Cultural Heritage, Migration, and Land Use Transformation in San José Chiltepec, Oaxaca. Land, 13(10), 1658. [CrossRef]

- CIMMYT. Tequio fortalece la cadena de valor del maíz en Oaxaca. Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo – Noticias 2020, 31 de agosto de 2020. Disponible en: https://www.cimmyt.org/es/noticias/tequio-fortalece-la-cadena-de-valor-del-maiz-en-oaxaca/.

- Chávez Servia, J.L.; Diego Flores, P. Familias campesinas y variación fenotípica de poblaciones nativas de maíz en la región de Tlaxiaco, Oaxaca. Desarrollo, Ambiente y Cultura 2011, 1(1), Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Unidad Oaxaca. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225069907 (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Tech & Leadership. Puesto de queso fresco y tamales en Tlaxiaco, Oaxaca. YouTube, 2024. Available online: https://youtube.com/shorts/MPJgBpOs8Kg?si=pdYlYMHqpUKoMk7y (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Ortega Ortega, T.; Vázquez García, V.; Flores Sánchez, D.; Núñez Espinoza, J.F. Agrobiodiversity, gender and food sovereignty in Tlaxiaco, Oaxaca. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 2017, 8(spe18), 3853–3866. Available online: https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext_plus&pid=S2007-09342017001003673&lng=es&tlng=en (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Cocina Con Gabby. Chorizo Oaxaqueño Casero | Con un Gran Sabor y Color unas de las Mejores Recetas que puedes Hacer. YouTube, n.d. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-4U-4nY8B3Y (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Semblanza Oaxaqueña. Carnita de chicharrón, chorizo, manteca, carne enchilada, costilla y más en el mercado municipal de Tlaxiaco. Facebook, n.d. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/share/v/16Y1Ms7mB8/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Semblanza Oaxaqueña. Tasajo del bueno en el mercado municipal de Tlaxiaco. Facebook. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1HXBYN8RhR/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Secretaría de Turismo del Estado de Oaxaca. ¡El maíz es la base de la alimentación oaxaqueña! Celebración del Día Estatal del Maíz Nativo. Facebook, 29 September 2024. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1Bh8SFmvbF/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Pérez, W. Bajo el calor del atole. Fundación Tortilla, 1 November 2022. Available online: https://fundaciontortilla.org/Cocina/bajo_el_calor_del_atole (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Nochixtlan Bonito. Masita y taco de Barbacoa de #Tlaxiaco #Oaxaca, la masita en Nochixtlan es blanca y en Tlaxiaco es enchilada ambas están muy ricas #GastronomiaDeNuestraMixteca. Facebook. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/share/p/15sV8oaMMz/ (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Fonteyne, S.; Castillo Caamal, J.B.; Lopez-Ridaura, S.; Van Loon, J.; Espidio Balbuena, J.; Osorio Alcalá, L.; Martínez Hernández, F.; Odjo, S.; Verhulst, N. Review of agronomic research on the milpa, the traditional polyculture system of Mesoamerica. Front. Agron. 2023, 5, 1115490. [CrossRef]

- Aguilar Avila, H. La milpa una forma de vida en Ñuu Kene Ndute (Ojo de Agua). Master’s Thesis, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Unidad Xochimilco, Ciudad de México, México, December 2017. Available online: https://repositorio.xoc.uam.mx/jspui/bitstream/123456789/936/1/190035.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Méndez Hernández, Á.; Hernández Hernández, A.A.; López Santiago, M.C.; Morales López, J. Herbolaria oaxaqueña para la salud, 1st ed.; Instituto Nacional de las Mujeres: Ciudad de México, México, 2009; ISBN 978-607-95272-1-1. Available online: http://cedoc.inmujeres.gob.mx/documentos_download/101102.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- París Pombo, M.D. Youth Identities and the Migratory Culture among Triqui and Mixtec Boys and Girls. Migr. Int. 2010, 5, 139–164. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1665-89062010000200005 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Reyes-Santiago, M.D.R.; Méndez-García, E.; Sánchez-Medina, P.S. A Mixed Methods Study on Community-Based Tourism as an Adaptive Response to Water Crisis in San Andrés Ixtlahuaca, Oaxaca, Mexico. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5933. [CrossRef]

- Gingell, J. Viva Zapotec! A Thriving Ecotourism Project in Mexico’s Oaxaca State. The Guardian 2025, 28 April. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2025/apr/28/viva-zapotec-a-thriving-ecotourism-project-in-mexicos-oaxaca-state (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Oropeza-Tosca, D.; Jiménez-Márquez, O.; Martínez-Gutiérrez, R.; Lucas-Bravo, G.; Rincón-Molina, C. Experiential and Sustainable Tourism: Teaching with Artificial Intelligence to Native Corn Producers in Tlaxiaco, Oaxaca. In Training, Education, and Learning Sciences; Nazir, S., Ed.; AHFE Open Access: USA, 2025; Volume 193. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Martínez, D.A.; Matías-Pérez, D.; Varapizuela-Sánchez, C.F.; Hernández-Bautista, E.; Sánchez-Medina, M.A.; García-Montalvo, I.A. Quesillo: a Cultural and Economic Legacy in Oaxaca through the Social and Solidarity Economy. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1496193. [CrossRef]

- Novotny, I.P.; Tittonell, P.; Fuentes-Ponce, M.H.; López-Ridaura, S.; Rossing, W.A.H. The Importance of the Traditional Milpa in Food Security and Nutritional Self-Sufficiency in the Highlands of Oaxaca, Mexico. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0246281. [CrossRef]

- Stainton, H. Tourism in Oaxaca. Tourism Teacher 2023. Available online: https://tourismteacher.com/tourism-in-oaxaca/ (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Sosa, M.; Aulet, S.; Mundet, L. Community-Based Tourism through Food: A Proposal of Sustainable Tourism Indicators for Isolated and Rural Destinations in Mexico. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6693. [CrossRef]

- Avalos-Rangel, M.A.; Campbell, D.E.; Reyes-López, D.; Rueda-Luna, R.; Munguía-Pérez, R.; Huerta-Lara, M. The Environmental-Economic Performance of a Poblano Family Milpa System: An Emergy Evaluation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9425. [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Ortiz, M.A.; Lugo-Espinosa, G.; Ortiz-Hernández, Y.D.; Pérez-Pacheco, R.; Ortiz-Hernández, F.E.; Martínez-Tomás, S.H.; Tavera-Cortés, M.E. Nature-Based Solutions for Conservation and Food Sovereignty in Indigenous Communities of Oaxaca. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8151. [CrossRef]

- Hirami, N.; Hidalgo Morales, M.R. Sustainable Community-Based Ecotourism Development Mechanism: Oaxaca and Puebla Cases in Mexico. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar 2024, 8(4), 11684–11702. [CrossRef]

- Rocandio-Rodríguez, M.; Santacruz-Varela, A.; Córdova-Téllez, L.; López-Sánchez, H.; Hernández-Bautista, A.; Castillo-González, F.; Lobato-Ortiz, R.; García-Zavala, J.J.; Antonio López, P. Estimation of Genetic Diversity in Seven Races of Native Maize from the Highlands of Mexico. Agronomy 2020, 10, 309. [CrossRef]

- Aragón-Martínez, M.; Serrato-Díaz, A.; Rocha-Munive, M.G.; Martínez-Castillo, J.; Perales, H.; Álvarez-Buylla, E.R. Traditional Management of Maize in the Sierra Sur, Oaxaca, Maintains Moderate Levels of Genetic Diversity and Low Population Differentiation Among Landraces. Econ. Bot. 2023, 77, 282–304. [CrossRef]

- Maranto-Gómez, V.M.; Rincón-Molina, C.I.; Manzano-Gómez, L.A.; Gen-Jiménez, A.; Maldonado-Gómez, J.C.; Villalobos-Maldonado, J.J.; Ruiz-Valdiviezo, V.M.; Rincón-Rosales, R.; Rincón-Molina, F.A. Plant Probiotic Potential of Native Rhizobia to Enhance Growth and Sugar Content in Agave tequilana Weber var. Blue. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 137. [CrossRef]

- Pskowski, M. Indigenous Maize: Who Owns the Rights to Mexico’s ‘Wonder’ Plant? Yale Environment 360 2019. Available online: https://e360.yale.edu/features/indigenous-maize-who-owns-the-rights-to-mexicos-wonder-plant (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Velasco-Murguía, A.; del Castillo, R.F.; Rös, M.; Rivera-García, R. Successional Pathways of Post-Milpa Fallows in Oaxaca, Mexico. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 500, 119644. [CrossRef]

- Rogé, P.; Friedman, A.R.; Astier, M.; Altieri, M.A. Farmer Strategies for Dealing with Climatic Variability: A Case Study from the Mixteca Alta Region of Oaxaca, Mexico. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2014, 38(7), 786–811. [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Ramírez, Q.; Bocco, G.; Solís-Castillo, B. Cajete maize in the Mixteca Alta region of Oaxaca, Mexico: adaptation, transformation, and permanence. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 44(9), 1162–1184. [CrossRef]

- Nixtamal99. Poetic Language of the Maguey. Masa Americana. 28 May 2021. Available online: https://masaamerica.com/2021/05/28/poetic-language-of-the-maguey/ (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Martínez-Cruz, T.; Camacho-Villa, T.C.; Adelman, L. Indigenous Peoples and the Making of Resilient Life: Hybridizing the Culture of Maize to Achieve Food Sovereignty. In Food and Humanitarian Crises: Science and Policies for Prevention and Mitigation; Pontificia Academia Scientiarum: Vatican City, 2023. Available online: https://www.pas.va/en/publications/scripta-varia/sv154pas/martinez_cruz.html (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Ramírez, C.A. Descubra el singular Agave Cupreata (Agave Papalome). Del Maguey Blog 2024. Available online: https://delmaguey.com/es/agave-cupreata/ (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Mardero, S.; Schmook, B.; Calmé, S.; White, R.M.; Joo Chang, J.C.; Casanova, G.; Castelar, J. Traditional knowledge for climate change adaptation in Mesoamerica: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2023, 7, 100473. [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Copado, J.; Orozco-Villafuerte, J.; Pedrero-Fuehrer, D.; Colín-Cruz, M.A. Sensory Profile Development of Oaxaca Cheese and Relationship with Physicochemical Parameters. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99(9), 7075–7084. [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-López, L.M.; Huerta-Jiménez, M.; Morales-Rodríguez, S.; Gámez-Piñón, J.R.; Carballo-Carballo, D.E.; Gutiérrez-Méndez, N.; Alarcón-Rojo, A.D. Textural, Rheological, and Sensory Modifications in Oaxaca Cheese Made with Ultrasonicated Raw Milk. Processes 2023, 11, 1122. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Méndez, N.; Rodríguez-Figueroa, J.C.; González-Córdova, A.F.; Nevárez-Moorillón, G.V.; Rivera-Chavira, B.; Vallejo-Cordoba, B. Phenotypic and Genotypic Characteristics of Lactococcus lactis Strains Isolated from Different Ecosystems. Can. J. Microbiol. 2010, 56(5), 432–439. [CrossRef]

- Warinner, C.; Robles Garcia, N.; Tuross, N. Maize, Beans and the Floral Isotopic Diversity of Highland Oaxaca, Mexico. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2013, 40(2), 868–873. [CrossRef]

- Dots on a Map. 15 Traditional Oaxacan Foods You Have to Try. Available online: https://www.dotsonamap.net/traditional-oaxacan-foods/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Secretaría de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural (SADER). Los orígenes del mixiote. Gobierno de México, 22 August 2025. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/agricultura/articulos/los-origenes-del-mixiote (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Fonteyne, S.; Castillo Caamal, J.B.; Lopez-Ridaura, S.; Van Loon, J.; Espidio Balbuena, J.; Osorio Alcalá, L.; Martínez Hernández, F.; Odjo, S.; Verhulst, N. Review of Agronomic Research on the Milpa, the Traditional Polyculture System of Mesoamerica. Front. Agron. 2023, 5, 1115490. [CrossRef]

- Siles, P. Fertilidad de los suelos en sistemas de pastos, café y cacao en el TeSAC Nicaragua. CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS): Managua, Nicaragua, 2019. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/107227.

- Severiano-Pérez, P.; Cristians, S.; Bye, R.; et al. Quelites Pasados of the Sierra Tarahumara, Chihuahua, Mexico: An Interdisciplinary Ethnobotanical Study of Leafy Green Vegetables. Econ. Bot. 2023, 77, 433–454. [CrossRef]

- Slotten, V.; Lentz, D.; Sheets, P. Landscape Management and Polyculture in the Ancient Gardens and Fields at Joya de Cerén, El Salvador. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2020, 59, 101191. [CrossRef]

- Arnés, E.; Astier, M. Handmade Comal Tortillas in Michoacán: Traditional Practices along the Rural-Urban Gradient. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3211. [CrossRef]

- Pope, V. The Communal Table: Communal Meal Traditions in Milpa Alta, Mexico. National Geographic, 2025. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/foodfeatures/communal-table/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Capra, F.; Luisi, P.L. The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Bost, J.A.Y.; et al. Edible Plants of the Chinantla, Oaxaca, Mexico with an Emphasis on Quelites. Univ. Res. Argo. 2009, —, —. Available online: https://www.avocadosource.com/papers/research_articles/bostjay2009.pdf.

- Peinado-Guevara, V.M.; Peinado-Guevara, H.J.; Sánchez-Alcalde, M.C.; González-Félix, G.K.; Herrera-Barrientos, J.; Ladrón de Guevara-Torres, M.d.l.Á.; Cuadras-Berrelleza, A.A. Backyard Activities as Sources of Social and Personal Well-Being: A Study of the Mexican Population (Guasave, Sinaloa). Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 462. [CrossRef]

- Avilez-López, T.; van der Wal, H.; Aldasoro-Maya, E.; et al. Home Gardens’ Agrobiodiversity and Owners’ Knowledge of Their Ecological, Economic and Socio-Cultural Multifunctionality: A Case Study in the Lowlands of Tabasco, México. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2020, 16, 42. [CrossRef]

- Medina, F.-X.; Vázquez-Medina, J.A.; Covarrubias, M.; Jiménez-Serna, A. Gastronomic Sustainable Tourism and Social Change in World Heritage Sites. The Enhancement of the Local Agroecological Products in the Chinampas of Xochimilco (Mexico City). Sustainability 2023, 15, 16078. [CrossRef]

- Sharer, E.J. Agroecology and Culinary Tourism: The Regeneration of Native Food Systems in Juluchuca, Guerrero, Mexico. Unpublished Thesis, Colorado College, Department of Anthropology, Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 2012. Available online: https://digitalcc.coloradocollege.edu/record/2087/files/Agroecology%20and%20Culinary%20Tourism%20the%20Regeneration%20of%20Native%20Food%20Systems%20in%20Juluchuca%2C%20Guerrero%2C%20Mexico.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Gen-Jiménez, A.; Flores-Félix, J.D.; Rincón-Molina, C.I.; Manzano-Gómez, L.A.; Villalobos-Maldonado, J.J.; Ruiz-Lau, N.; Roca-Couso, R.; Ruíz-Valdiviezo, V.M.; Rincón-Rosales, R. Native Rhizobium Biofertilization Enhances Yield and Quality in Solanum lycopersicum under Field Conditions. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 41(4), 126. [CrossRef]

- Oropeza-Tosca, D.R.; Rincón-Molina, C.I.; Baptista, A.; Notario-Priego, R. Perspective Chapter: Development of Business in Rural Southeastern Mexican Communities and Environmental Awareness. In Degrowth and Green Growth—Sustainable Innovation; Martínez-Gutiérrez, R., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024; pp. 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Rincón-Rosales, R.; Villalobos-Escobedo, J.M.; Rogel, M.A.; Martínez, J.; Ormeño-Orrillo, E.; Martínez-Romero, E. Rhizobium calliandrae sp. nov., Rhizobium mayense sp. nov. and Rhizobium jaguaris sp. nov., Rhizobial Species Nodulating the Medicinal Legume Calliandra grandiflora. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63(9), 3423–3429. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Márquez, O.; Soria Saavedra, R.; Pesce Gomez, A. Una Opción de Turismo Alternativo y Vivencial, Caso la Microcuenca Río Delgado. In La Producción de Conocimiento en las Ciencias Sociales Aplicadas; Atena Editora: Ponta Grossa, Brasil, 2023; Capítulo 6, pp. 58–76. Available online: https://atenaeditora.com.br/catalogo/dowload-post/77104 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Martínez-Gutiérrez, R.; Barreto-Canales, I.G.; Lucas-Bravo, G.; Moreno-Cabral, S. SDG Voluntary Local Reports (VLRs): Analysis of Glocal Sustainable Innovation. In Degrowth and Green Growth—Sustainable Innovation; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Aloo, B.N.; Tripathi, V.; Makumba, B.A.; Mbega, E.R. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacterial Biofertilizers for Crop Production: The Past, Present, and Future. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1002448. [CrossRef]

- Battiston, R.; di Pietro, W.; Amerini, R.; Sciberras, A. The Praying Mantids (Insecta: Mantodea) as Indicators for Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation: A Case Study from the Maltese and Balearic Archipelagos. Biodiversity 2020, 21(3), 142–149. [CrossRef]

| Practice Type | Description | Local Ingredients/Tools | Seasonality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maize Cultivation | Milpa planting with intercropping and tequio participation | Native corn, coa, mezcal | March–April |

| Maize Harvesting | Once the husk and stalk are dry, the maize is ready to be harvested | Picker, tenate (basket), troje (storage shed) | August–November |

| Cheese Production | Traditional fermentation for 6 to 72 hours and wrapped in banana leaves | Raw cow milk, salt, banana leaves | Year-round |

| Tortilla Making | Hand-formed and comal-cooked tortillas prepared by women | Corn (white, blue, yellow), lime | Daily |

| Mushroom Foraging | Seasonal collection in forests during the rainy season | Forest mushrooms | June–August |

| Salsa Preparation | Tomato and chili salsa ground in a molcajete and served with meats | Tomatoes, chiles, molcajete | Daily |

| Boiled Beans (Frijoles sancochados) | Cooked with spring water | Pork lard, salt, garlic, onion, epazote | Daily |

| Creole Hen Broth (Caldo de gallina criolla) |

Cooked with spring water | Rice, hoja santa, tomato, garlic, salt, onion | Weekly |

| Compost Production | Organic food scraps and animal waste used for natural fertilization | Manure, kitchen waste | Year-round |

| Activity | Willingness to Host Visitors | Available Infrastructure | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional tortilla-making demonstration | High | Comal, space in homes | Women are enthusiastic about sharing this tradition |

| Milpa field tour | Medium | Pathways, shaded areas | Best during planting or harvesting seasons |

| Cheese-making workshop | Medium–High | Holstein cows, tools | Requires sanitary precautions |

| Mushroom foraging | Low (seasonal) | Forest access | Only possible during the rainy season |

| Hosting visitors at home | Medium | Cabins, extra rooms | Requires prior notice and flexibility |

| Forest walk and flora/fauna photography | High | Natural trails | Birds, salamanders, orchids, bromeliads, agave, juniper, and more can be observed |

| Observation of springs and irrigation channels | High | Access to natural water bodies | Ideal for connecting with nature and learning about traditional water management |

| Visits to caves, marine fossils, and rock paintings | High | Rural trails, pedestrian access | Requires hiking on uneven terrain and prior scheduling |

| Traditional food tasting | High | Community kitchens | Dishes include chicken soup, beans with cheese, handmade tortillas, chicharrón or tripe salsa, carnitas |

| Pulque bread-making workshop | High | Wood-fired oven, local ingredients | Uses pulque, eggs, sugar, salt, lard; requires advance notice |

| Observation and feeding of poultry (chickens, turkeys) | High | Chicken coops, available feed | Visitors can feed corn, oats, and alfalfa; suitable for families and children |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).