1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain the leading cause of morbidity and mortality globally [

1]. Reducing cholesterol levels is crucial to both prevention and management [

2]. Although pharmacological agents (e.g., statins) are available, their use may cause adverse effects, prompting interest in effective, safe, and health-promoting alternatives for cholesterol reduction [

3,

4]. Probiotics with cholesterol-lowering properties have attracted increasing attention. For example, Yue Li et al. [

5] reported that

Lactobacillus plantarum H6 can significantly lower serum cholesterol levels in hypercholesterolemic mice by modulating intestinal microbiota composition (notably increasing

Muribaculaceae abundance) and regulating microbial metabolites (including short-chain fatty acids and vitamins). Similarly, Narathip Puttarat et al. [

6] validated that specific probiotics (such as

Limosilactobacillus reuteri TF-7,

Enterococcus faecium TF-18, and

Bifidobacterium animalis TA-1) can markedly reduce serum cholesterol levels in hypercholesterolemic rats via bile salt hydrolase activity and cholesterol assimilation, with synergistic lipid-lowering effects observed in mixed-strain treatments. Despite these advances, the mechanisms by which probiotics lower cholesterol levels remain incompletely understood [

7,

8].

Bile salt hydrolase (BSH, EC 3.5.1.24) is prevalent in the mammalian gut microbiota, including

Lactobacillus,

Clostridium,

Bacteroides, and

Bifidobacterium. Among these,

Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium are the primary sources of high-yield BSH bacteria used in

in vitro studies [

9,

10]. BSH catalyzes the hydrolysis of conjugated bile acids, releasing free bile acids and amino acids (glycine/taurine) [

11,

12,

13]. Multiple studies have linked BSH activity to cholesterol-lowering effects. For instance, Fengjie Huang et al. [

14] reported that theaflavins in Pu'er tea can inhibit BSH activity, elevate conjugated bile acids levels, obstruct the farnesoid X receptor-fibroblast growth factor 15 (FXR-FGF15) signalling pathway, and diminish cholesterol levels in both mice and humans. Similarly, Guangqiang Wang et al. [

15] engineered a high-activity BSH strain which attenuated hepatic steatosis by enhancing bile acid deconjugation, suppressing the FXR signaling, and upregulating cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1) expression. Our laboratory has conducted continuous research on the cholesterol-lowering properties of the lactic acid bacterium BSH [

16]. Experiments have also shown that the BSH recombinant strain bacterium derived from YB334 exhibits cholesterol-lowering properties through FXR-mediated regulation of bile acids after TCA hydrolysis [

17]. Recent investigations have documented this discovery, which is consistent with our findings. Joyce et al. [

18] reported that

Escherichia coli producing BSH from recombinant

Lactobacillus salivarius exhibited probiotic effects, including lowering plasma cholesterol levels, managing body weight, and modulating glucose and lipid metabolism in mice fed a high-fat diet. The study findings indicated a notable reduction in hepatic FXR expression and a substantial increase in small intestine FXR expression. Conversely, Lina Yao et al. [

19] documented that a

Bacteroides strain with a disrupted BSH gene markedly lowered plasma cholesterol levels in mice on a high-fat diet, resulting in a significant decline in hepatic FXR expression without considerable alteration in small intestine FXR expression.

Our recent comparative study using germ-free (GF) and specific-pathogen-free (SPF) mice revealed that the regulatory influence of the intestinal microbiota contributes to the cholesterol-lowering effects of the lactic acid bacterium BSH [

20]. Building on this foundation, the current study comprehensively investigated the YB334 recombinant bacterium to elucidate a novel mechanism underlying the cholesterol-lowering effect involving BSH-mediated alterations of the intestinal microbiota.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Strain and Culture

All strains used in this study are listed in

Table 1. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium were cultivated anaerobically at 37 °C. Lactobacillus was cultured in de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) medium, while Bifidobacterium was cultured in modified MRS agar medium (supplemented with mupirocin lithium salt and cysteine hydrochloride) [

21]. Both media were obtained from Haibo Ltd. (Qingdao, China). Erythromycin (Em

r; Sangon Biotech Ltd., Shanghai, China) was added at a final concentration of 10 μg/mL.

2.2. Animal Experimentation

All mice were obtained from Gempharmatech Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Nanjing Normal University (Approval Number: SYXK 2020-0047), and all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Six-week-old male C57BL/6 mice (specific pathogen-free, SPF grade) were used in this study. They were housed in SPF conditions at the Experimental Animal Centre of Nanjing Normal University under a 12 h light/dark cycle with temperature maintained at 23 ± 2 °C and relative humidity at 55 ± 5%. The normal diet (ND) and high cholesterol diet (HCD; containing 15% fat, 1.25% cholesterol, and 0.5% sodium cholate) were purchased from Jiangsu Synergy Pharmaceutical Bioengineering Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China).

Following one week of adaptive feeding, the mice were divided into two groups: the control group received a ND, while the experimental group was fed a HCD to induce hypercholesterolaemia. Thereafter, the experimental group received a daily oral gavage of 200 μL of a bacterial suspension (1×10⁹ CFU/mL). In contrast, the ND and HCD control group were administered equivalent volumes of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Sangon Biotech) or skim milk (SM; Anchor, New Zealand), respectively.

Preparation of bacterial suspensions:

Recombinant lactic acid bacteria (NB5462 and YB334): Single colonies were inoculated into liquid medium and cultured overnight for 12 h. The cultures were then diluted in fresh MRS medium to an OD600nm of approximately 0.1, and incubated at 37 °C until the OD600nm reached around 0.3. Protein expression was induced by adding the SppIP inducer peptide (amino acid sequence: MAGNSSNFIHKIKQIFTHR; Genscript Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) at a final concentration of 50 ng/mL. Cultivation continued until an OD600nm of 2.5 was achieved. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed, and resuspended in PBS for storage at 4 °C.

Bifidobacterium pseudolongum BPL-4: A single colony was inoculated into liquid medium and cultured for 16 h overnight. A 1% (v/v) inoculum of this seed culture was transferred to 45 mL of fresh, modified MRS broth supplemented with mupirocin lithium salt and cysteine hydrochloride. After 12 h of incubation, the bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation. The pellet was resuspended in 10% sterile SM and stored at 4 °C.

The experimental period lasted for six to seven weeks, during which mouse body weight was monitored weekly Upon completion of the gavage period, mice were fasted for 12 h (ad libitum access to water was maintained) and subsequently anesthetized with diethyl ether. Blood samples were collected via retro-orbital bleeding. Thereafter, the mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation. Immediately following euthanasia, the liver, ileum, ileal contents, and duodenum were aseptically collected, placed in sterile, nuclease-free microcentrifuge tubes, and snap-frozen at -80 °C for subsequent analysis.

2.3. Serum Biochemical Parameter Analysis

Whole blood was collected from mice via retro-orbital bleeding. After incubation at room temperature for 30 min, the samples were centrifuged at 1500 ×g for 15 min to isolate serum. The serum levels of total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) were quantified using an automated biochemistry analyzer (Hitachi 7100) at the Animal Centre of Nanjing Medical University.

2.4. Liver Histological Analysis

Liver tissue, preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde, was embedded in paraffin, and the resultant wax blocks were sectioned into 4 μm thickness. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and subsequently photographed using an optical microscope (Wuhan Savier Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China).

2.5. Metagenomics Analysis

Metagenomic DNA was extracted from mouse feces using the E.Z.N.A.® Soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek, USA). Qualified DNA samples were used to construct sequencing libraries, which were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq/HiSeq Xten platform (Illumina, USA). The resulting reads were aligned to the host mouse genome using BWA to remove host-derived sequences. Subsequently, non-redundant gene sets were generated with MetaGene and CD-HIT. All bioinformatic analyses were performed on the Majorbio Cloud Platform (

https://cloud.majorbio.com; Shanghai Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd., China).

2.6. Isolation and Identification of B. Pseudolongum in Mouse Feces

Fecal samples were obtained from mice in the HCD + YB334 cohort and suspended in PBS. The samples were then serially diluted and plated onto modified MRS agar supplemented with mupirocin lithium salt and cysteine hydrochloride. Following incubation, bacterial colonies were isolated. Genomic DNA was extracted, and the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the universal bacterial primers 27F (5’-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3’) and 1492R (5’-TACGGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3’). The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products were purified and sent to Sangon Biotech for Sanger sequencing. The resulting sequences were analyzed using the basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) to identify homologous bacterial sequences (

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST).

2.7. BSH Activity Assays

The strain's bile salt-degrading activity was assessed using the indophenol method [

22]. An overnight culture was centrifuged, and the pellet was resuspended in 0.1 M HAc-NaAc buffer (pH 5.0; Sangon Biotech) to a final OD

600nm of 5.0. This suspension was then mixed with a bile salt substrate containing 5 mM each of glycocholic acid (GCA) and taurocholic acid (TCA) sodium salts (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After incubation at 37 °C for 1 h, the enzymatic reaction was terminated by adding 100 μL of 15% trichloroacetic acid (Sangon Biotech). Subsequently, 100 μL of the supernatant was transferred, mixed with 900 μL of indophenol solution (Sangon Biotech), and vortexed thoroughly. The mixture was incubated in a water bath for 14 min, cooled in ice water, and its optical density was measured at 570 nm after standing for 5 min.

For the analysis of bile acids in murine fecal samples, Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) was performed using an ExionLC AD liquid chromatography system coupled to a QTRAP® 6500+ mass spectrometer (Majorbio).

2.8. Effect of Addition of Crude Extract of YB334-BSH Enzyme on the Growth of Different Strains of Bacteria

Strain preparation was conducted as previously outlined for animal experiments, with an uninduced control group established and cultivated for 20 h. The bacterial culture was centrifuged at 8000 ×g at 4 °C for 15 min, rinsed with PBS, and resuspended in fresh MRS medium supplemented with TCA at a final concentration of 5 mM in ratios of 10:1 and 5:1 (v/v). The suspension was homogenised using glass beads (speed 6.00 m/s, cycle 10, 30 seconds on, 30 seconds off), followed by centrifugation at 12000 ×g at 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was then removed, filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane filter, and preserved for future use.

Various test strains were initiated and cultured in their appropriate media until the logarithmic phase was reached. A 1% (v/v) inoculum was transferred to 200 μL of MRS + TCA medium containing a crude BSH enzyme extract derived from the YB334 recombinant strain, with MRS + TCA medium used as the control. The 96-well plate was positioned in a microplate reader (Varioskan LUX, Thermo Fisher Scientific, China) and maintained at a constant temperature of 37 °C. The OD at 600 nm was recorded at 30-min intervals, and plate colony counts were performed after 5 h of incubation.

2.9. TCA/CA Bile Salt Tolerance

Two distinct bile salts, taurocholate acid sodium salt (TCA) and cholic acid (CA), were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich to evaluate the bile salt tolerance of the test strains [

23]. Various strains were first inoculated onto appropriate solid media, and individual colonies were selected and transferred to corresponding liquid media for overnight incubation. The overnight culture were then inoculated at 1% (v/v) into fresh liquid media and incubated for 12 h. Subsequently, bacterial cells were harvested from three replicate cultures by centrifugation at 8000 ×g at 4 °C for 15 min. The pellets were washed and resuspended in equal volumes of either PBS buffer containing 5 mM TCA or PBS buffer containing 5 mM CA. The suspensions were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h, and viable counts (CFU/mL) were determined using the pour plate method to assess the survival of each strain in the presence of the respective bile salts.

2.10. RNA Isolation and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from mouse ileum and liver tissues using the RNAiso Plus Kit (Takara Biomedical Technology, Beijing, China). Following extraction, cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript

TM RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara). Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was then performed on a LightCycler System using TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (Takara), with cDNA as the template. The amplification protocol followed the manufacturer's instructions for the TB Green® Premix Ex Taq

TM II Reagent Kit on the LightCycler 480 System. Gene expression levels were calculated using the 2

-ΔΔCT method, with rpL32 mRNA as the internal control, and are presented relative to the HCD group. The primer sequences for RT-qPCR are listed in

Table 2.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

All experimental date are presented as mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD). Graphical representation and statistical analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 9.5). Comparisons among multiple groups were conducted by one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey's post-hoc test for assessing significant differences between individual groups. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. BSH Recombinant Bacterium YB334 Has Cholesterol-Lowering Properties

Figure 1A-B illustrates that after 7 weeks of feeding a HCD, mice in the HCD group showed a substantial increase in body weight relative to those in the ND group (

p < 0.001), confirming effective animal model establishment. Oral administration of either NB5462 of YB334 strains, delivered via gavage, exhibited a specific mitigating effect on weight gain in mice. Compared to the HCD + NB5462 group, the HCD + YB334 group exhibited a markedly smaller increase in body weight (

p < 0.001), with no significant difference in body weight relative to the ND group (

p ≥ 0.05). These results demonstrate that while a high-cholesterol diet can promote weight gain in mice, the recombinant BSH strain YB334 can more successfully mitigate this effect than the NB5462.

Figure 1C illustrates the serum cholesterol levels in mice. Compared to the ND group, TC levels were considerably elevated in mice in the HCD group (

p < 0.001), validating the effective establishment of a hypercholesterolemic animal model. Compared to the HCD + NB5462 group, mice in the HCD + YB334 group exhibited a substantial decrease in TC levels (

p < 0.001). Additionally, the HCD + YB334 group exhibited a substantial reduction in both LDL-C and HDL-C levels compared to the HCD group (

p < 0.05), whereas the HCD + NB5462 group showed no significant change (

p ≥ 0.05).

Figure 1D shows a histological study of the liver tissue stained with H&E. Compared to the HCD + YB334 group, mice in the HCD and HCD + NB5462 groups demonstrated substantial lipid degeneration, suggesting that YB334 ameliorates pathological liver conditions caused by a high-cholesterol diet. These results demonstrate that the BSH recombinant bacterium YB334 can reduce TC, LDL-C, and HDL-C in hypercholesterolemic mice, thereby facilitating further investigation of the cholesterol-lowering mechanisms underlying BSH's cholesterol-lowering effects.

3.2. BSH of Recombinant Bacterium YB334 Regulates Intestinal Flora Distribution

Metagenomic sequencing was performed to investigate intestinal microbiota alterations induced by the BSH recombinant bacterium YB334 (

Figure 2). β-diversity analysis was employed to assess the variance among samples based on all non-redundant gene sets. Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) (

Figure 2A) revealed significant separation of the HCD, HCD + NB5462, and HCD + YB334 groups from the ND group, indicating substantial alterations in the gut microbiota structure among these three groups. Analysis of the genus-level intestinal microbiota in the four mouse groups (

Figure 2B) revealed significant alterations in the relative abundances of 20 species, with the predominant genera being

Turicibacter,

Ligilactobacillus, and

Bifidobacterium.

Subsequent analyses using linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) revealed that the microbial taxa exhibited substantial alterations in relative abundance among the groups (

Figure 2C). Compared to the HCD group, the relative abundances of taxa such as

Eggerthellaceae,

Lactiplantibacillus,

Malacoplasma, and

Erysipelatoclostridium were enriched in the HCD + YB334 group. Notably,

Eggerthellaceae has been linked to cholesterol metabolism [

28], while

Erysipelatoclostridium has demonstrated a negative correlation with cholesterol [

29]. Compared with the HCD + NB5462 group, the relative abundances of genera including

Bifidobacterium,

Limosilactobacillus,

Erysipelotrichaceae, and

Atopobiaceae augmented in the HCD + YB334 group.

Bifidobacterium lowers cholesterol via BSH activity and modulating bile acid metabolism [

30];

Limosilactobacillus can decrease TC levels [

31]; and

Atopobiaceae is a bacterium exhibiting extensive substrate specificity for BSH [

32]. The relative abundance of

Erysipelotrichaceae was significantly elevated in the HCD + YB334 group compared to the HCD and HCD + NB5462 groups. Collectively, these findings suggest that BSH generated by the recombinant bacterium YB334 can ameliorate HCD-induced dysbiosis, which is hypothesized to contribute to its cholesterol-lowering properties.

The HCD + YB334 group displayed the highest abundance of the dominant genus

Bifidobacterium. Wilcoxon rank-sum testing (

Figure 2D) revealed that the relative abundance of

B. pseudolongum was markedly elevated in the HCD + YB334 group relative to the HCD + NB5462 (p < 0.05), with this increase being the most pronounced relative to the other gut microbiota. These findings suggest that the decrease in cholesterol in the HCD + YB334 group is strongly associated with enrichment of gut microbiota, specifically

B. pseudolongum.

3.3. Screening of B. Pseudolongum BPL and Determination of BSH Activity

Preliminary metagenomic research revealed that the HCD + YB334 group possessed abundant gut microbial resources, with B. pseudolongum exhibiting the highest prevalence. Consequently, fecal samples from this group were used for isolating and screening B. pseudolongum.

Fresh feces were homogenized in sterile PBS, and serially diluted to 10-5, 10-6 and 10-7. A volume of 100 μL of the supernatant was plated on modified MRS agar supplemented with mupirocin lithium salt and cysteine hydrochloride, followed by anaerobic incubation at 37 °C for 48 h. The isolated single colonies were purified, and 66 colonies were selected for biochemical characterization and 16S rDNA sequencing. Subsequent analysis identified all the obtained strains as members of the genus Bifidobacterium. Further analysis using national center for biotechnology information (NCBI)-BLAST revealed 54 isolates as B. pseudolongum, subsequently named BPL. The remaining isolates, were classified as two strains of Bifidobacterium longum, BL-4 and BL-7, and one strain of Bifidobacterium adolescentis, BA-6.

The BSH activities of the eight isolated strains of

B. pseudolongum were assessed, and the results are presented in

Table 3. The activity levels varied, leading to the selection of strains BPL-1 (moderate BSH activity), BPL-2 (low BSH activity), and BPL-4 (high BSH activity) for further experiments.

3.4. Effect of Crude Extract of Recombinant Bacterium YB334-BSH on the Growth of Different Strains

BPL-1, BPL-2, BPL-4, BA-6, BL-4, BL-7, J5, J16, and L2 were introduced into MRS + TCA medium supplemented with either inducible (+) or non-inducible (-) BSH crude extracts derived from YB334 recombinant bacterial cultures and subsequently incubated for 5 h. MRS + TCA medium was used as a control. The experimental findings revealed three distinct scenarios:

Figure 3A illustrates that, in contrast to the control group, the culture media infused with the YB334-BSH crude extract and inducer markedly enhanced the proliferation of many strains of

B. pseudolongum, particularly when administered at a 10:1 supernatant-to-medium ration, demonstrating a significant growth-promoting impact, rising from 10

6 CFU/mL to 10

7 CFU/mL. The BPL-4 strain (accession No. PX061997) showed the most significant growth-promoting effects (

Figure 3D). Conversely, the uninduced extract did not significantly influence the proliferation of

B. pseudolongum;

AS shown in

Figure 3B, crude extracts of YB334-BSH, whether induced or non-induced, did not significantly enhance the development of

B. adolescentis BA-6 and

B. longum BL-4 and BL-7;

As shown in

Figure 3C, the induced YB334-BSH crude extract showed inhibitory effects on

Lactobacillus johnsonii J5 and J16, as well as

L. reuteri L2, decreasing their counts from 10⁷ CFU/mL to 10⁶ CFU/mL.

The results revealed that the culture medium containing the induced YB334 crude extract demonstrated selective enhancement of growth across various bacterial strains, with the most pronounced effect observed in BPL strains.

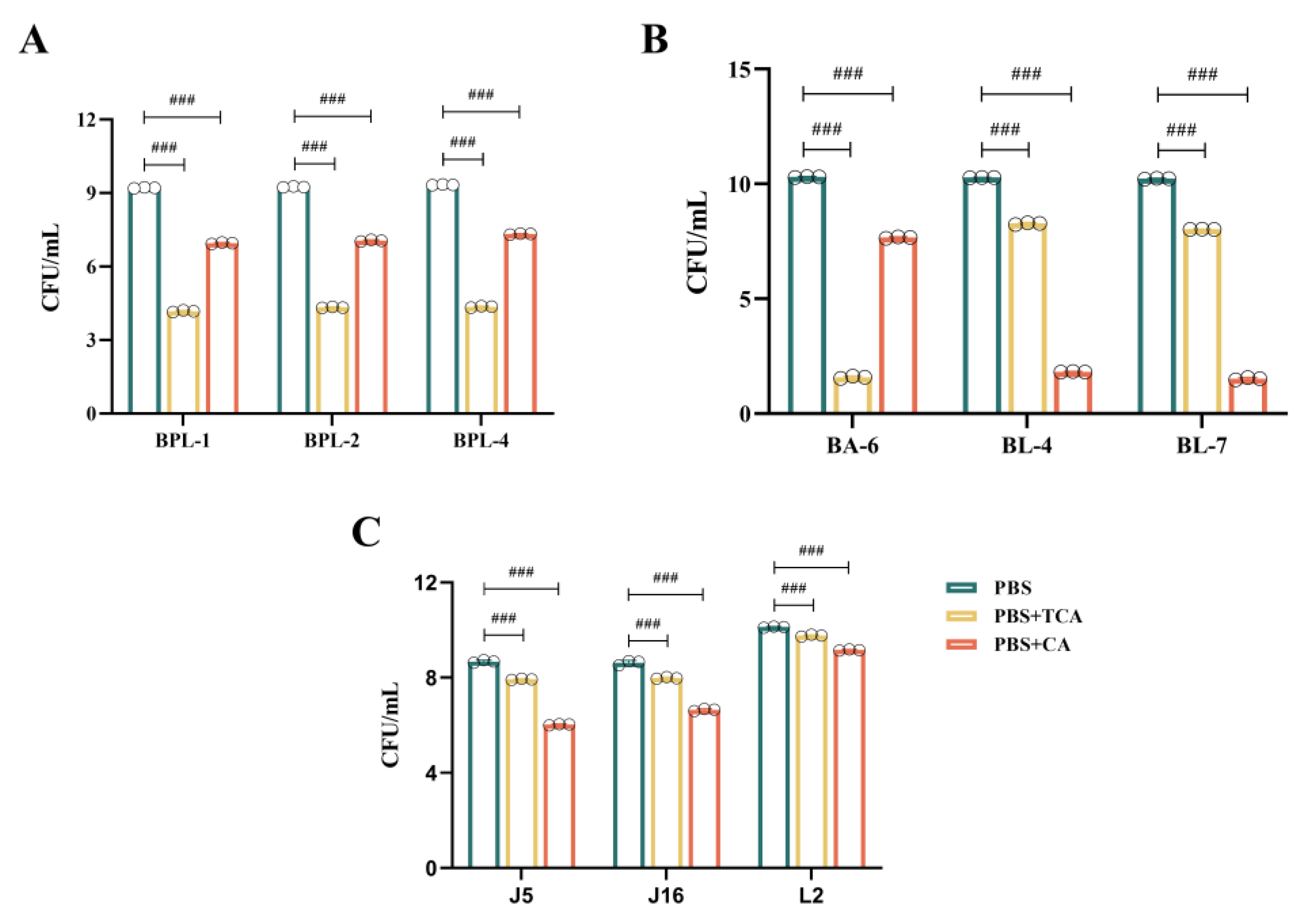

3.5. Effect of Different Strains on Tolerance to TCA/CA Bile Salts

Upon simultaneous addition of TCA and CA to the culture medium at equal concentrations, all nine strains showed growth reductions compared to that in PBS (

Figure 4). The experimental findings revealed three distinct scenarios:

Figure 4A illustrates that the

B. pseudolongum BPL-1, BPL-2, and BPL-4 displayed a notable tolerance to TCA, with a decline from 10

9 CFU/mL to 10

4 CFU/mL; however, they exhibited superior tolerance to CA, with a decrease from 10

9 CFU/mL to 10

7 CFU/mL;

As shown in

Figure 4B,

B. adolescentis BA-6 was highly sensitive to TCA, declining from 10

10 CFU/mL to 10

1 CFU/mL, while it exhibited relatively good tolerance to CA, decreasing from 10

10 CFU/mL to 10

7 CFU/mL. Conversely,

B. longum BL-4 and BL-7 demonstrated poor tolerance to CA, diminishing from 10

10 CFU/mL to 10

1 CFU/mL, but moderate tolerance to TCA, decreasing from 10

10 CFU/mL to 10

8 CFU/mL;

Figure 4C illustrates that

L. johnsonii J5 and J16, along with

L. reuteri L2, demonstrate a notable resistance to both TCA and CA. TCA concentrations diminished from 10

8 CFU/mL to 10

7 CFU/mL, from 10

8 CFU/mL to 10

7 CFU/mL, and from 10

10 CFU/mL to 10

9 CFU/mL, respectively. CA diminished from 10

8 CFU/mL to 10

6 CFU/mL, from 10

8 CFU/mL to 10

6 CFU/mL, and from 10

10 CFU/mL to 10

9 CFU/mL, respectively. They also demonstrated the highest tolerance to TCA.

These data demonstrated that BSH enzyme influences bile tolerance in a strain-dependent manner. Consequently, we hypothesized that such variations may result from the catalytic characteristics of the BSH enzyme, which catalyzes TCA substrate to CA, and that various strains may exhibit differing tolerances to TCA and CA.

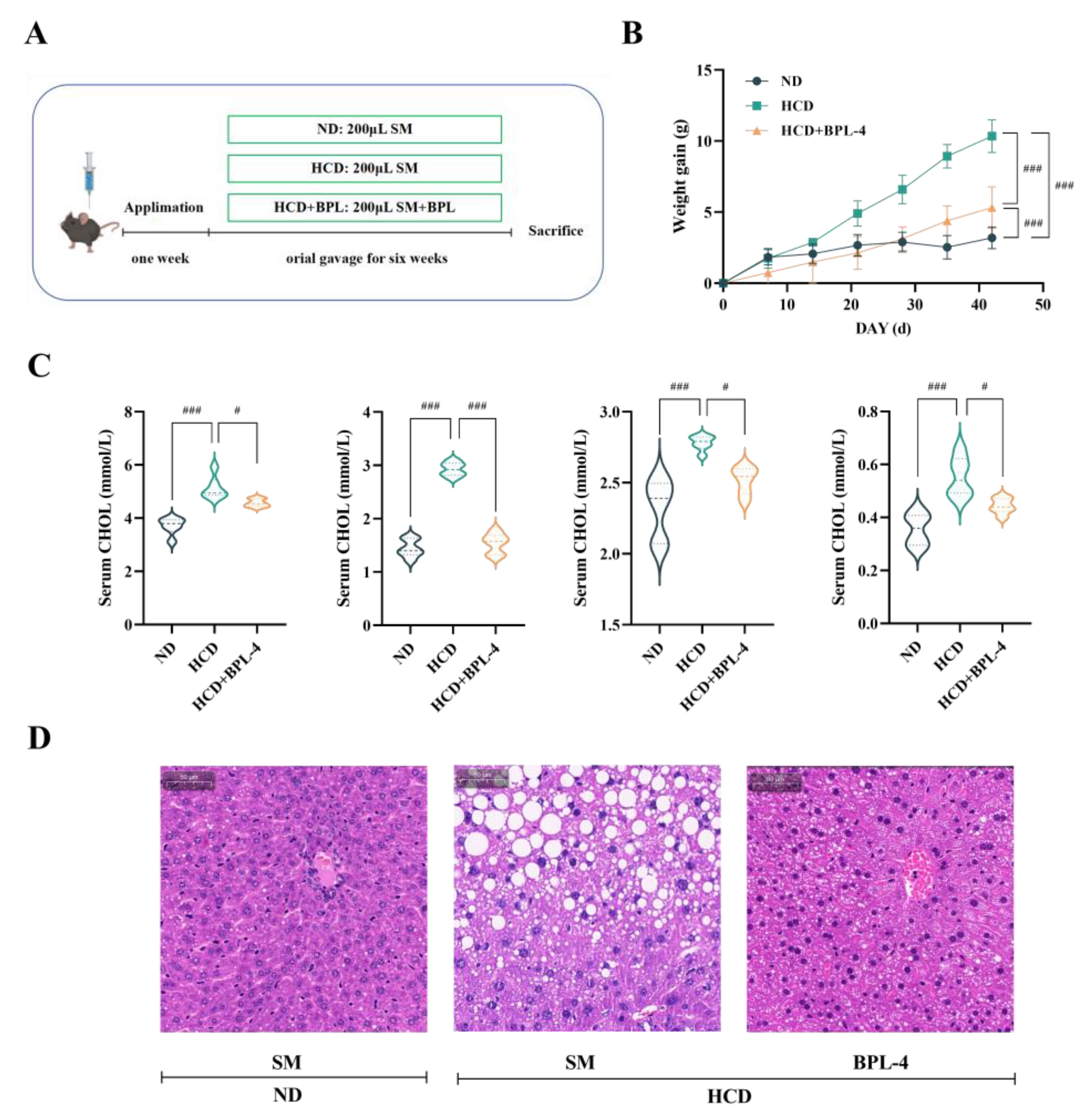

3.6. B. Pseudolongum BPL-4 Has Cholesterol-Lowering Effects

Figure 5A-B illustrates that after 6 weeks of a HCD, mice in the HCD group gained considerable body weight relative to those in the ND group (

p < 0.001), confirming successful model establishment. Compared to the HCD group, the body weight of mice in the HCD + BPL-4 group was substantially reduced (

p < 0.001). As shown in

Figure 5C, serum cholesterol levels in the HCD group were markedly increased relative to the ND group (

p < 0.01), validating the effectiveness of the high-cholesterol animal model. In comparison with the HCD group, TC levels in the HCD + BPL-4 group were markedly diminished (

p < 0.05), and both LDL-C and HDL-C levels were significantly reduced (

p < 0.05).

Figure 5D shows a histological study of the liver tissue stained with H&E. Compared to the HCD + BPL-4 group, mice in the HCD group demonstrated substantial fat degeneration, suggesting that BPL-4 ameliorates liver pathological conditions caused by a HCD. The results revealed that

B. pseudolongum BPL-4 effectively lowered serum cholesterol levels in hypercholesterolemic mice.

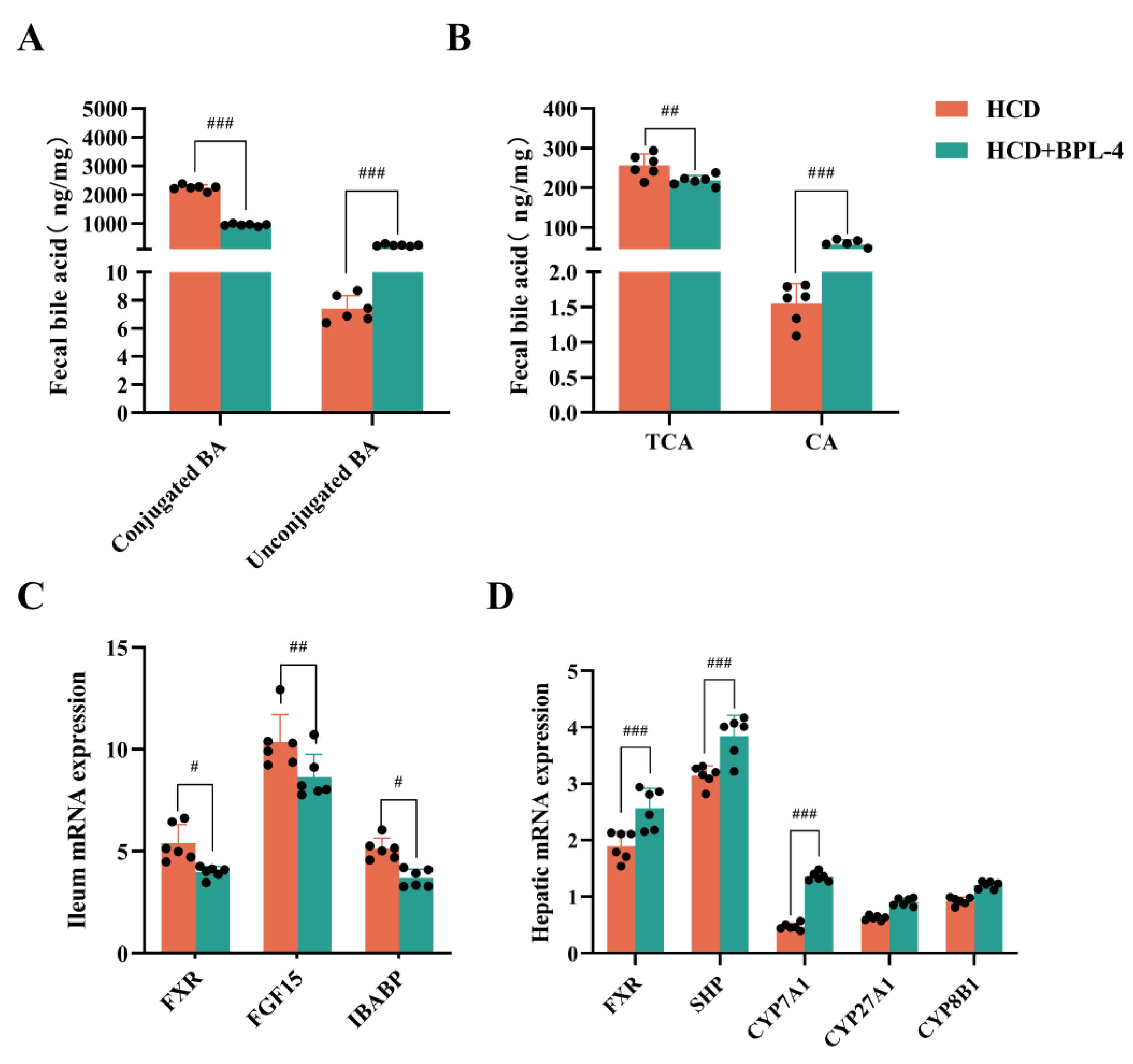

3.7. BSH Indirectly Regulates Intestinal FXR in B. Pseudolongum BPL-4

Figure 6A-B display bile acid profiles in the experimental groups. The HCD + BPL-4 group demonstrated markedly reduced conjugated bile acids (

p < 0.001) and substantially elevated unconjugated bile acids (

p < 0.001) compared to the HCD group. Analysis of individual bile acids revealed significantly reduced (

p < 0.01) TCA levels and elevated (

p < 0.001) CA levels in the HCD + BPL-4 group relative to those in the HCD group. The alterations in bile acid profiles indicate a function for TCA substrate-specific BSH in mice administered with BPL-4 via gavage.

RT-qPCR was employed to assess the expression of signalling molecules linked to the FXR pathway in the liver and ileum tissues (

Figure 6C-D). In comparison to the HCD group, the expression levels of FXR and short heterodimer partner (SHP) in the liver were markedly elevated in the HCD + BPL-4 group (

p < 0.05), but the expression of FXR and its downstream genes, FGF15 and intestinal bile acid binding protein (IBABP), in the ileum was dramatically reduced (

p < 0.05). CYP7A1 expression was markedly elevated in the livers of the HCD + BPL-4 group (

p < 0.001), whereas sterol 27-hydroxylase (CYP27A1) and sterol 12α-hydroxylase (CYP8B1) expression was not significantly altered (

p > 0.05). Given the negative feedback link between CYP7A1 and FXR, we posit that the cholesterol-lowering effect of BPL-4 is facilitated by reducing intestinal FXR, which in turn elevates CYP7A1 expression and diminishes endogenous cholesterol production.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the mechanisms by which Lactobacillus-derived BSH enzymes modulate cholesterol-lowering effects on microbial interactions. Building on prior investigations, the current investigation was conducted on mice using the gavage of BSH recombinant bacterium YB334, with subsequent macro-genome sequencing of their fecal samples to identify the 'responsive' strains of intestinal flora that exhibited substantial changes due to BSH exposure. Metagenomics analysis revealed substantial alterations in B. pseudolongum and L. reuteri compared with the empty-plasmid control. To further characterize these changes, mouse fecal samples were cultured on modified MRS agar plate enriched with lithium mupirocin and cysteine hydrochloride. After anaerobic incubation at 37 °C for 48 h, 66 colonies were isolated and identified as Bifidobacterium through biochemical methods and 16S rDNA sequencing. Among these, 54 colonies were classified as B. pseudolongum, representing 82% of the total, indicating significant advancement in subsequent experiments.

To elucidate the mechanism by which

B. pseudolongum responds to BSH activity, we conducted

in vitro assays by supplementing its culture medium with supernatants from recombinant YB334-BSH bacterial cultures. The findings indicated that the culture medium enriched with the YB334-BSH crude extract, which included the inducer, enhanced the proliferation of

B. pseudolongum in a concentration-dependent manner. As the concentration increased from 5:1 to 10:1, the promoting effect on

B. pseudolongum was amplified, with the BPL-4 strain exhibiting the most pronounced increase. The enhancement of

B. pseudolongum growth by the YB334-BSH crude extract with the inducer was specific to the strain. It exerted no notable promotional effect on

B. adolescentis BA-6 and

B. longum BL-4, and BL-7, and even demonstrated inhibitory effects on

L. johnsonii J5 and J16, as well as

L. reuteri L2. Given that BSH enzymes catalyze the hydrolysis of TCA to CA, we examined the tolerance of various strains to CA and TCA. The findings indicated that several strains of

B. pseudolongum and

B. adolescentis BA-6 showed markedly greater tolerance to CA than to TCA, whereas

B. longum BL-4 and BL-7 displayed significantly enhanced tolerance to TCA than to CA.

L. johnsonii J5 and J16, together with

L. reuteri L2, exhibited considerable tolerance to both TCA and CA. Taken together, these data suggest that under the influence of the YB334 BSH, TCA is hydrolyzed into CA, demonstrating significant tolerance to

B. pseudolongum and thereby facilitating its proliferation. Certain bacterial strains in the gut microbiota exhibiting similar bile salt tolerance may also exhibit alterations in abundance due in response to BSH activity [

33,

34].

Subsequently, we conducted a murine experiment using

B. pseudolongum BPL-4. The findings indicated that, in comparison with the control group, blood cholesterol levels, including TC, LDL-C, and HDL-C, were markedly diminished in high-cholesterol mice administered BPL-4. These results illustrate the cholesterol-reducing effect of BPL-4. An investigation into the mechanism of BPL-4's cholesterol-lowering effects revealed that mice receiving BPL-4 through oral gavage demonstrated markedly decreased levels of conjugated bile acids and substantially elevated levels of unconjugated bile acids. Specifically, TCA levels were significantly diminished, whereas CA levels were significantly increased. In mouse livers, the expression of FXR and SHP was markedly elevated, whereas in the ileum, the expression of FXR and its downstream genes, FGF15 and IBABP, was dramatically diminished. Concurrently, hepatic CYP7A1 expression was notably increased. These results unequivocally indicated that the

B. pseudolongum strain evaluated in this study, when administered to mice on a high-fat diet, significantly decreased FXR levels and augmented CYP7A1 enzymatic activity, thereby lowering cholesterol levels. This method of action aligns with the previously documented cholesterol-lowering mechanism of the YB334 recombinant strain through FXR [

17].

Our findings expand on prior reports on the probiotic effects of secondary metabolites produced by

B. pseudolongum. Qian Song et al. [

35] demonstrated that

B. pseudolongum mitigates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatocarcinogenesis through the secretion of antitumor metabolites, such as acetate, via the gut-liver axis. Additionally, Ke Zhang et al. [

36] indicated that carvacrol and thymol (CAT) enhances the abundance of

B. pseudolongum, activates its cyclic guanosine monophosphate-protein kinase G pathway (cGMP-PKG) signalling pathway, and consequently inhibits dextran sulfate sodium-induced (DSS-induced) colitis. Nonetheless, metabolomic sequencing examination of BPL-4 samples fed via gavage to experimental mice in this investigation revealed no significant variations in the cholesterol-lowering effects of secondary metabolites produced by

B. pseudolongum (results not shown).

This study identified

B. pseudolongum as a strain that notably responds to BSH, with its cholesterol-lowering mechanism mediated through the regulation of the bile acid receptor FXR signaling pathway [

37,

38,

39]. Importantly, the response of

B. pseudolongum to BSH is characterized by markedly greater tolerance to the BSH catalytic product CA than to TCA. To our knowledge, this is the first study to establish a novel mechanism by which BSH modulates certain gut bacterial strains to reduce cholesterol levels. This study focused on the YB334 recombinant strain, which exhibits substrate specificity for TCA hydrolysis. However, BSH strains possess varying substrate specificities, including GCA and TβMCA. We hypothesized that variations in bile acid profiles resulting from BSH strains with distinct substrate specificities may have divergent effects on gut microbiota modulation [

40]. Additional investigations are required to examine the impact of BSH strains with varying substrate specificities on the regulation of gut microbiota to enhance the understanding of how BSH lowers cholesterol levels through modulation of gut microbiota.

5. Conclusions

In this study, complementary in vivo and in vitro experiments were performed to comprehensively examine the mechanism of action of BSH activity in modulating gut microbiota and cholesterol metabolism. Oral treatment with YB334 recombinant bacteria with elevated BSH activity markedly reduced cholesterol levels in hypercholesterolemic mice, whereas metagenomic sequencing revealed B. pseudolongum as a strain that notably responded to BSH. Second, in vitro investigations demonstrated that BSH particularly enhanced the proliferation of B. pseudolongum, indicating that this effect correlated with its elevated tolerance to the BSH catalytic product CA. Subsequent animal experiments demonstrated that BPL-4 significantly lowers cholesterol by modulating bile acid metabolism and the FXR signaling pathway, as evidenced by decreased levels of conjugated bile acids, increased hepatic CYP7A1 expression, and suppression of ileal FXR signaling. This study elucidated a novel mechanism of BSH-B. pseudolongum interaction in cholesterol metabolism and established a scientific foundation for the development of cholesterol-lowering probiotic formulations targeting the gut microbiota. Future research should investigate the precise mechanisms through which BSH strains with varying substrate specificities modulate the gut microbiota and cholesterol metabolism, and assess their therapeutic potential in the prevention and treatment of metabolic disorders, including cardiovascular disease.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, Y. Y.; validation, Y. L., W. K. and M. L.; formal analysis, investigation and data curation, Y. L and Y. Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Y. L, Z. W. and M. Z.; writing—review and editing, Y. Y. and YR. L.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. and H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFF0619500), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu (no. BK20231280) and the Jiangsu Agriculture Science and Technology Innovation Fund (CX(22)2019).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Nanjing Normal University (Approval Code: SYXK 2020-0047; Approval Date: 15 February 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be accessed from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of Biorender to create the graph abstract.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BSH |

Bile salt hydrolase |

| FXR |

Farnesoid X receptor |

| CYP7A1 |

Cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase |

| GF |

Germ-free |

| SPF |

Specific pathogen-free |

| MRS |

de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe |

| ND |

Normal diet |

| HCD |

High cholesterol diet |

| PBS |

Phosphate-buffered saline |

| SM |

Skim milk |

| HDL-C |

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LDL-C |

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| TC |

Total cholesterol |

| TG |

Triglycerides |

| H&E |

Hematoxylin and eosin |

| PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction |

| BLAST |

Basic local alignment search tool |

| GCA |

Glycocholic acid |

| TCA |

Taurocholic acid |

| LC-MS/MS |

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry |

| CA |

Cholic acid |

| RT-qPCR |

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| PCoA |

Principal coordinates analysis |

| LEfSe |

Linear discriminant analysis effect size |

| NCBI |

National center for biotechnology information |

| SHP |

Short heterodimer partner |

| FGF15 |

Fibroblast growth factor 15 |

| IBABP |

Intestinal bile acid binding protein |

| CYP27A1 |

Sterol 27-hydroxylase |

| CYP8B1 |

Sterol 12α-hydroxylase |

| CAT |

Carvacrol and thymol |

| cGMP-PKG |

Cyclic guanosine monophosphate-protein kinase G pathway |

| DSS-induced |

Dextran sulfate sodium-induced |

References

- Martin, S.S.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.A.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Gibbs, B.B.; Beaton, A.Z.; Boehme, A.K.; et al. 2024 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: A Report of US and Global Data From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024, 149, E347–E913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, K.; Mohan, S.; Hossain, S.A.; Shah, S.; Konat, A.; Shah, K.; Mehta, S.; Tavethia, J.J.; Sarvaiya, J.N.; Joshi, S.; et al. Prevalence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors in high-risk Kyrgyzstan population as compared to Indians − An Indo-Kyrgyz cardiometabolic study. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2024, 13, 5621–5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baigent, C.; Landray, M.J.; Reith, C.; Emberson, J.; Wheeler, D.C.; Tomson, C.; Wanner, C.; Krane, V.; Cass, A.; Craig, J.; et al. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with simvastatin plus ezetimibe in patients with chronic kidney disease (Study of Heart and Renal Protection): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2011, 377, 2181–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Arnold, M.; Stevens, D.; Kaptoge, S.; Pennells, L.; Sweeting, M.J.; Barrett, J.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Wood, A.M. Prediction of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Accounting for Future Initiation of Statin Treatment. Am. J. Epidemiology 2021, 190, 2000–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Ma, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Ma, H.; Ren, D.; Chen, P. Regulation of viable/inactivated/lysed probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum H6 on intestinal microbiota and metabolites in hypercholesterolemic mice. npj Sci. Food 2022, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puttarat, N.; Kasorn, A.; Vitheejongjaroen, P.; Chantarangkul, C.; Tangwattanachuleeporn, M.; Taweechotipatr, M. Beneficial Effects of Indigenous Probiotics in High-Cholesterol Diet-Induced Hypercholesterolemic Rats. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, S.A.; Conceição, L.; Rosa, D.D.; Siqueira, N.P.; Peluzio, M.C.G. Mechanisms responsible for the hypocholesterolaemic effect of regular consumption of probiotics. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2016, 30, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.-B.; Lew, L.-C.; Yeo, S.-K.; Parvathy, S.N.; Liong, M.-T. Probiotics and the BSH-related cholesterol lowering mechanism: a Jekyll and Hyde scenario. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2013, 35, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, S.A.; Gahan, C.G. Bile Acid Modifications at the Microbe-Host Interface: Potential for Nutraceutical and Pharmaceutical Interventions in Host Health. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 7, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horáčková, Š.; Plocková, M.; Demnerová, K. Importance of microbial defence systems to bile salts and mechanisms of serum cholesterol reduction. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, M.H.; O’fLaherty, S.; Barrangou, R.; Theriot, C.M.; Knoll, L.J. Bile salt hydrolases: Gatekeepers of bile acid metabolism and host-microbiome crosstalk in the gastrointestinal tract. PLOS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Lee, B.H. Bile salt hydrolases: Structure and function, substrate preference, and inhibitor development. Protein Sci. 2018, 27, 1742–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Joyce, S.; Shanahan, F.; Hill, C.; Gahan, C.G. Bacterial bile salt hydrolase in host metabolism: Potential for influencing gastrointestinal microbe-host crosstalk. Gut Microbes 2014, 5, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, F.; Zheng, X.; Ma, X.; Jiang, R.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, S.; Wang, S.; Kuang, J.; et al. Theabrownin from Pu-erh tea attenuates hypercholesterolemia via modulation of gut microbiota and bile acid metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Huang, W.; Xia, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Ai, L. Cholesterol-lowering potentials ofLactobacillusstrain overexpression of bile salt hydrolase on high cholesterol diet-induced hypercholesterolemic mice. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 1684–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miremadi, F.; Sherkat, F.; Stojanovska, L. Hypocholesterolaemic effect and anti-hypertensive properties of probiotics and prebiotics: A review. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 25, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, W.; Xia, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y. Cholesterol-lowering effect of bile salt hydrolase from aLactobacillus johnsoniistrain mediated by FXR pathway regulation. Food Funct. 2021, 13, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, S.A.; MacSharry, J.; Casey, P.G.; Kinsella, M.; Murphy, E.F.; Shanahan, F.; Hill, C.; Gahan, C.G.M. Regulation of host weight gain and lipid metabolism by bacterial bile acid modification in the gut. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 7421–7426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, L.; Seaton, S.C.; Ndousse-Fetter, S.; A Adhikari, A.; DiBenedetto, N.; I Mina, A.; Banks, A.S.; Bry, L.; Devlin, A.S. A selective gut bacterial bile salt hydrolase alters host metabolism. eLife 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Kuang, W.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, H.; Yang, Y. Cholesterol lowering in diet-induced hypercholesterolemic mice using Lactobacillus bile salt hydrolases with different substrate specificities. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 1340–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, P.; Fitzgerald, G.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R. The evaluation of a mupirocin-based selective medium for the enumeration of bifidobacteria from probiotic animal feed. J. Microbiol. Methods 2004, 57, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, P.P.; Annapure, U.S. Fermentation dynamics of bile salt hydrolase production in Heyndrickxia coagulans ATCC 7050 and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum ATCC 10012: Addressing ninhydrin assay limitations with a novel HPTLC–MS method. J. Microbiol. Methods 2024, 226, 107050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frappier, M.; Auclair, J.; Bouasker, S.; Gunaratnam, S.; Diarra, C.; Millette, M. Screening and Characterization of Some Lactobacillaceae for Detection of Cholesterol-Lowering Activities. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2022, 14, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Zhang, F.; Yuan, W.; Wei, Y.; Wei, M.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chang, Y.; Wu, X. Hepatic cholesterol accumulation ascribed to the activation of ileum Fxr-Fgf15 pathway inhibiting hepatic Cyp7a1 in high-fat diet-induced obesity rats. Life Sci. 2019, 232, 116638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, X.; Huang, D.; Dong, Z.; Wang, X.; Ning, M.; Xia, J.; Shen, S.; Wu, S.; Shi, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. FXR Signaling-Mediated Bile Acid Metabolism Is Critical for Alleviation of Cholesterol Gallstones by Lactobacillus Strains. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0051822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayin, S.I.; Wahlström, A.; Felin, J.; Jäntti, S.; Marschall, H.-U.; Bamberg, K.; Angelin, B.; Hyötyläinen, T.; Orešič, M.; Bäckhed, F. Gut Microbiota Regulates Bile Acid Metabolism by Reducing the Levels of Tauro-beta-muricholic Acid, a Naturally Occurring FXR Antagonist. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gottardi, A.; Touri, F.; Maurer, C.A.; Perez, A.; Maurhofer, O.; Ventre, G.; Bentzen, C.L.; Bentzen, E.J.; Dufour, J.-F. The Bile Acid Nuclear Receptor FXR and the Bile Acid Binding Protein IBABP Are Differently Expressed in Colon Cancer. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2004, 49, 982–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, L.; Dang, H.; Wu, J.; Yuan, L.; Chen, X.; Yao, J. Supplementation of Weizmannia coagulans BC2000 and Ellagic Acid Inhibits High-Fat-Induced Hypercholesterolemia by Promoting Liver Primary Bile Acid Biosynthesis and Intestinal Cholesterol Excretion in Mice. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakrishnan, T.T.; Sangwan, N.; Barot, S.V.; Farha, N.; Mariam, A.; Xiang, S.; Aucejo, F.; Conces, M.; Nair, K.G.; Krishnamurthi, S.S.; et al. Multi-omics machine learning to study host-microbiome interactions in early-onset colorectal cancer. npj Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, B.; Zou, Y.; Han, X.; Bae, J.-W.; Jeon, C.O. Gut microbiome-mediated mechanisms for reducing cholesterol levels: implications for ameliorating cardiovascular disease. Trends Microbiol. 2022, 31, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, R.; Song, J.; Sohaib, M.; Wang, S.; Mao, J.; Qi, J.; Xiong, X.; Zhou, W.; Guo, L. Limosilactobacillus reuteri consumption significantly reduces the total cholesterol concentration without affecting other cardiovascular disease risk factors in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Res. 2023, 117, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morinaga, K.; Kusada, H.; Tamaki, H. Bile Salt Hydrolases with Extended Substrate Specificity Confer a High Level of Resistance to Bile Toxicity on Atopobiaceae Bacteria. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- etin, B.; Aktaş, H. Monitoring probiotic properties and safety evaluation of antilisterial Enterococcus faecium strains with cholesterol-lowering potential from raw Cow's milk. Food Bioscience 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yu, H.; Feng, X.; Tang, H.; Xiong, Z.; Xia, Y.; Ai, L.; Song, X. Specific bile salt hydrolase genes in Lactobacillus plantarum AR113 and relationship with bile salt resistance. LWT 2021, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, W.; Wei, H.; Liang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Ding, Y.; Ji, F.; Cheung, A.H.-K.; Wong, N.; et al. Bifidobacterium pseudolongum-generated acetate suppresses non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1352–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Lei, Y.; Cao, X.; Wang, X.; Yan, F.; et al. Bifidobacterium pseudolongum-Derived Bile Acid from Dietary Carvacrol and Thymol Supplementation Attenuates Colitis via cGMP-PKG-mTORC1 Pathway. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2406917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Jiang, C.; Krausz, K.W.; Li, Y.; Albert, I.; Hao, H.; Fabre, K.M.; Mitchell, J.B.; Patterson, A.D.; Gonzalez, F.J. Microbiome remodelling leads to inhibition of intestinal farnesoid X receptor signalling and decreased obesity. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyata, M.; Tanaka, T.; Takahashi, K.; Funaki, A.; Sugiura, Y. Cholesterol-lowering effects of taurine through the reduction of ileal FXR signaling due to the alteration of ileal bile acid composition. Amino Acids 2021, 53, 1523–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wang, H.; Bukhari, I.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, H.; Yu, Y.; Sun, X.; Mi, Y.; Mei, L.; Zheng, P. Effects of cholesterol-lowering probiotics on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in FXR gene knockout mice. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1121203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusada, H.; Arita, M.; Tohno, M.; Tamaki, H. Isolation of a Highly Thermostable Bile Salt Hydrolase With Broad Substrate Specificity From Lactobacillus paragasseri. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 810872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

High-cholesterol modeling (A: experimental design; B: weight gain) and physiological and biochemical indexes (C: serum lipid; D: hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained liver tissue section) were used to evaluate the fat-reducing function of BSH strain in these four groups (ND: normal diet; HCD: high cholesterol diet; HCD + NB5462: high cholesterol diet + empty plasmid control NB5462; HCD + YB334: high cholesterol diet + YB334). TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglycerides; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). Scale bars, 50 μm. White dots in H&E staining diagram indicate lipid droplets. # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001.

Figure 1.

High-cholesterol modeling (A: experimental design; B: weight gain) and physiological and biochemical indexes (C: serum lipid; D: hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained liver tissue section) were used to evaluate the fat-reducing function of BSH strain in these four groups (ND: normal diet; HCD: high cholesterol diet; HCD + NB5462: high cholesterol diet + empty plasmid control NB5462; HCD + YB334: high cholesterol diet + YB334). TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglycerides; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). Scale bars, 50 μm. White dots in H&E staining diagram indicate lipid droplets. # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

YB334 regulated the gut microbiota. (A) β-diversity analysis of sample metagenomes using principal coordinates analysis (PCoA). (B) Gut microbiota composition at species levels. (C) Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe). (D) Differential species testing at the genus level. ND: normal diet; HCD: high cholesterol diet; HCD + NB5462: high cholesterol diet + empty plasmid control NB5462; HCD + YB334: high cholesterol diet + YB334. Values were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

YB334 regulated the gut microbiota. (A) β-diversity analysis of sample metagenomes using principal coordinates analysis (PCoA). (B) Gut microbiota composition at species levels. (C) Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe). (D) Differential species testing at the genus level. ND: normal diet; HCD: high cholesterol diet; HCD + NB5462: high cholesterol diet + empty plasmid control NB5462; HCD + YB334: high cholesterol diet + YB334. Values were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Figure 3.

The effect of YB334-BSH enzyme crude extract on the growth of different strains. (A): Bifidobacterium pseudolongum BPL-1, BPL-2 and BPL-4. (B): Bifidobacterium adolescentis BA-6 and Bifidobacterium longum BL-4 and BL-7. (C): Lactobacillus johnsonii J5 and J16 and Limosilactobacillus reuteri L2. (D). BPL-4 growth curve. Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001.

Figure 3.

The effect of YB334-BSH enzyme crude extract on the growth of different strains. (A): Bifidobacterium pseudolongum BPL-1, BPL-2 and BPL-4. (B): Bifidobacterium adolescentis BA-6 and Bifidobacterium longum BL-4 and BL-7. (C): Lactobacillus johnsonii J5 and J16 and Limosilactobacillus reuteri L2. (D). BPL-4 growth curve. Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001.

Figure 4.

Growth of different strains when TCA and CA are added. (A): B. pseudolongum BPL-1, BPL-2 and BPL-4. (B): B. adolescentis BA-6 and B. longum BL-4 and BL-7. (C): L. johnsonii J5 and J16 and L. reuteri L2. Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001.

Figure 4.

Growth of different strains when TCA and CA are added. (A): B. pseudolongum BPL-1, BPL-2 and BPL-4. (B): B. adolescentis BA-6 and B. longum BL-4 and BL-7. (C): L. johnsonii J5 and J16 and L. reuteri L2. Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001.

Figure 5.

High-cholesterol modeling (A: experimental design; B: weight gain) and physiological and biochemical indexes (C: serum lipid; D: H&E stained liver tissue section) were used to evaluate the fat-reducing function of BSH strain in these three groups (ND: normal diet; HCD: high cholesterol diet; HCD + BPL-4: high cholesterol diet + BPL-4). TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglycerides; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). Scale bars, 50 μm. White dots in H&E staining diagram indicate lipid droplets. # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001.

Figure 5.

High-cholesterol modeling (A: experimental design; B: weight gain) and physiological and biochemical indexes (C: serum lipid; D: H&E stained liver tissue section) were used to evaluate the fat-reducing function of BSH strain in these three groups (ND: normal diet; HCD: high cholesterol diet; HCD + BPL-4: high cholesterol diet + BPL-4). TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglycerides; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). Scale bars, 50 μm. White dots in H&E staining diagram indicate lipid droplets. # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001.

Figure 6.

Fecal bile acid (A: conjugated and unconjugated BA; B: TCA and CA) and and genes related to hepatic FXR (C) and ileal FXR (D) of SPF mice were used to analyze the TC-reducing metabolism of BSH. HCD: high cholesterol diet; HCD + BPL-4: high cholesterol diet + BPL-4. TCA: taurocholic acid; CA: cholic acid. Values were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001.

Figure 6.

Fecal bile acid (A: conjugated and unconjugated BA; B: TCA and CA) and and genes related to hepatic FXR (C) and ileal FXR (D) of SPF mice were used to analyze the TC-reducing metabolism of BSH. HCD: high cholesterol diet; HCD + BPL-4: high cholesterol diet + BPL-4. TCA: taurocholic acid; CA: cholic acid. Values were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study.

| Strains |

Descriptionsa |

Source or reference |

| Lactobacillus johnsonii |

|

|

| YH334 |

Wide type |

Laboratory screening [17] |

| J5 |

Wide type |

This study |

| J16 |

Wide type |

This study |

| Lactiplantibacillus plantarum |

|

|

| YB334 |

Emr, the pSIP334 plasmid was introduced into strain WCFS1Δbsh

|

Laboratory construction [17] |

| NB5462 |

Emr, the pSIP334 plasmid was introduced into strain WCFS1Δbsh

|

Laboratory construction [17] |

| Bifidobacterium pseudolongum |

|

|

| BPL |

Wide type |

This study |

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis |

|

|

| BA-6 |

Wide type |

This study |

| Bifidobacterium longum |

|

|

| BL-4 |

Wide type |

This study |

| BL-7 |

Wide type |

This study |

| Limosilactobacillus reuteri |

|

|

| L2 |

Wide type |

This study |

Table 2.

Table 2. Primer sequence in this study.

Table 2.

Table 2. Primer sequence in this study.

| Primer |

Sequence (5’-3’) |

Reference |

| FXR-F |

GGAACTCCGGACATTCAAC |

[24] |

| FXR-R |

GTGTCCATCACTGCACATC |

| SHP-F |

TCCTAGCCAAGACAGTAGCCTTCC |

[25] |

| SHP-R |

TACCGCTGCTGGCTTCCTCTAG |

| CYP7A1-F |

GCTAAGACGCACCTCGTGATCC |

| CYP7A1-R |

CCGCAGAGCCTCCTTGATGATG |

| FGF15-F |

CGGTCGCTCTGAAGACGATTGC |

| FGF15-R |

TACATCCTCCACCATCCTGAACGG |

| CYP27A1-F |

ATTAAGGAGACCCTGCGCCT |

| CYP27A1-R |

AGGCAAGACCGAACCCCATA |

| CYP8B1-F |

AAGGCTGGCTTCCTGAGCTT |

[26] |

| CYP8B1-R |

AACAGCTCATCGGCCTCATC |

| IBABP-F |

GGCCCGCAACTTCAAGATC |

[27] |

| IBABP-R |

TAGTGCTGGGACCAAGTGAAGTC |

| rpL32-F |

TCTGGTCCACAACGTCAAGG |

[17] |

| rpL32-R |

GGATTGGTGACTCTGATGGC |

Table 3.

BSH activities of different Bifidobacterium pseudolongum strains.

Table 3.

BSH activities of different Bifidobacterium pseudolongum strains.

| Strain |

enzyme activity(U/mL)

|

| GCA |

TCA |

| BPL-1 |

0.84 ± 0.06*** |

1.83 ± 0.07*** |

| BPL-2 |

0.44 ± 0.03*** |

1.37 ± 0.03*** |

| BPL-4 |

2.11 ± 0.05*** |

2.53 ± 0.04*** |

| BPL-5 |

0.84 ± 0.02*** |

1.93 ± 0.07*** |

| BPL-8 |

0.95 ± 0.11*** |

1.90 ± 0.07*** |

| BPL-9 |

0.93 ± 0.02*** |

1.60 ± 0.03*** |

| BPL-10 |

1.24 ± 0.04*** |

2.96 ± 0.08*** |

| BPL-11 |

0.60 ± 0.08*** |

1.71 ± 0.07*** |

| NB5462 |

0.07 ± 0.01 |

0.07 ± 0.02 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).