Submitted:

08 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents for the Development of DNA Biosensor

2.2. Solutions

2.3. Apparatus

2.4. UV-Vis Study of ssDNA Along with Leucine

3. Procedures

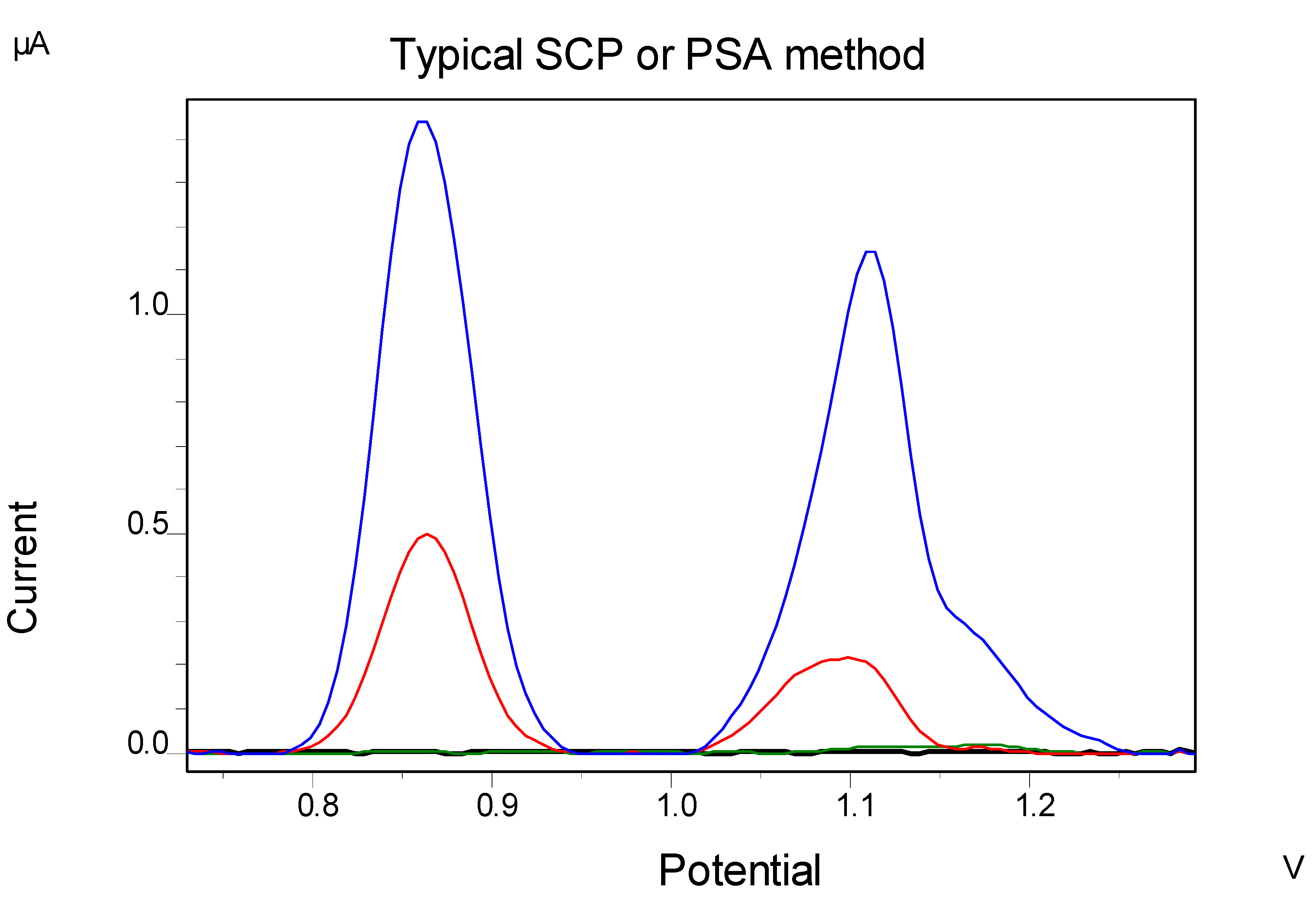

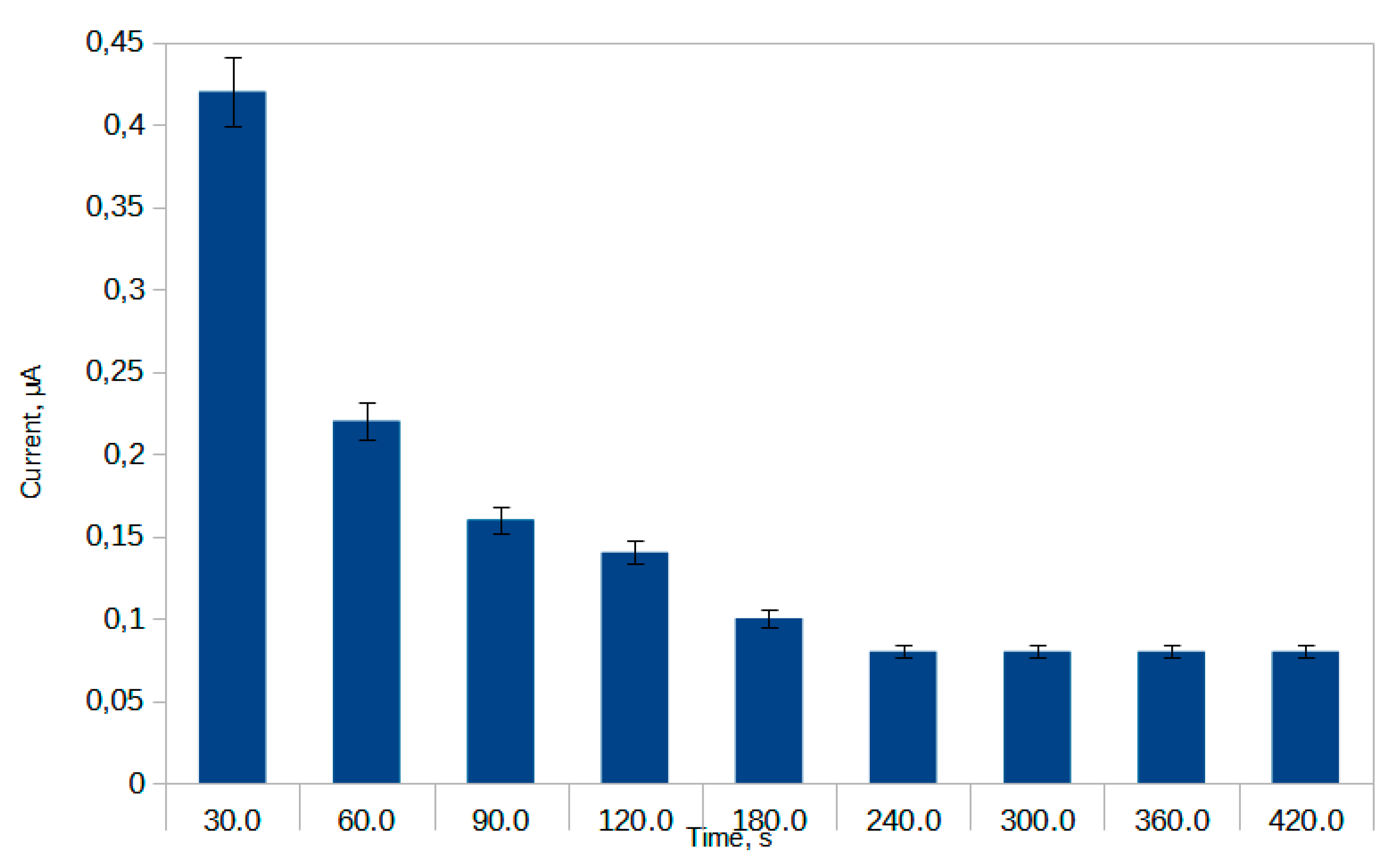

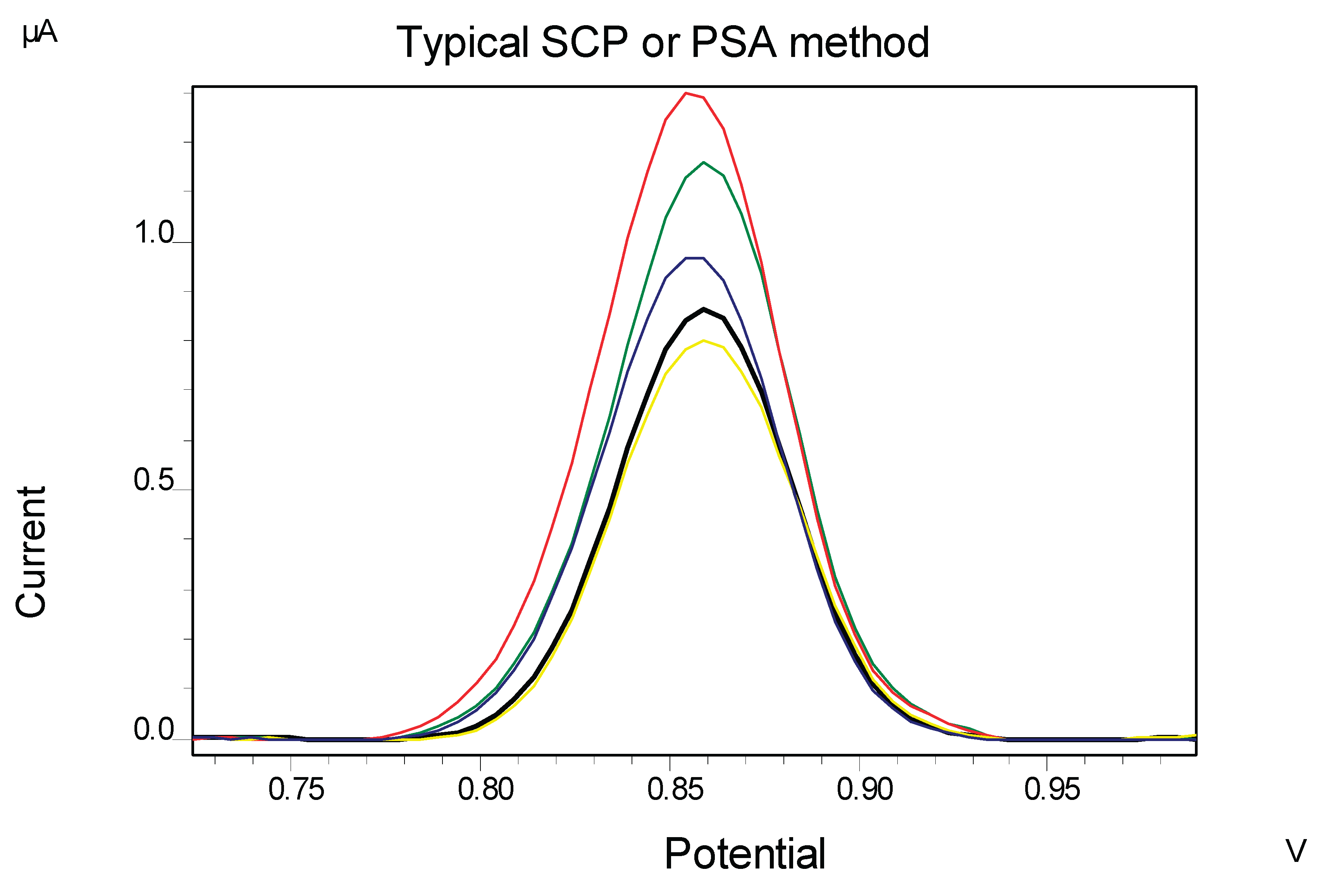

3.1. Interaction of ssDNA with Leu at the CPE/ssDNA Based Biosensor with Leucine

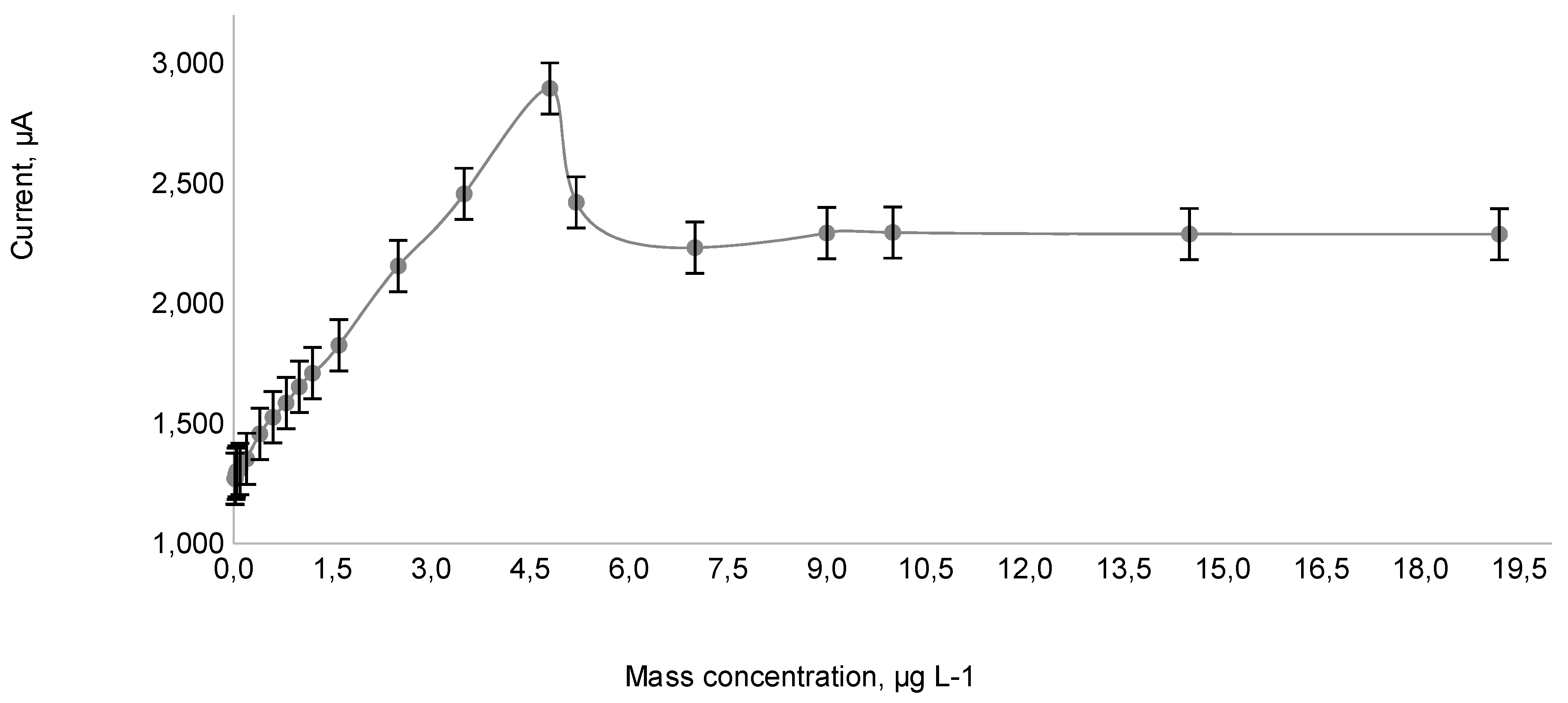

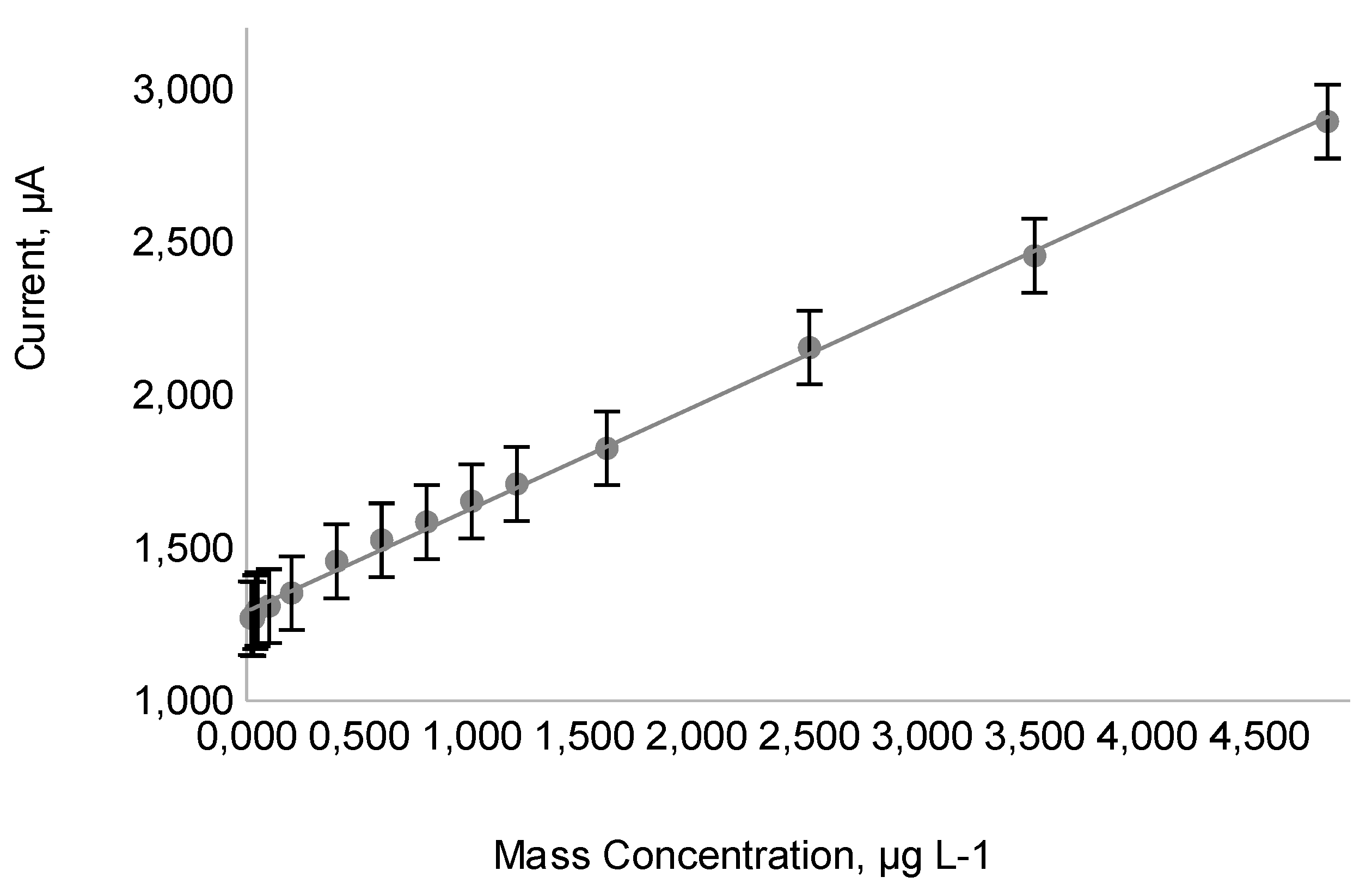

4. Results and Discussion

Interferences' Study

5. Application in Soil Sample

6. Conclusions

References

- Haghighi, M. , Barzegar Sadeghabad, A., Abolghasemi, R.. Effect of exogenous amino acids application on the biochemical, antioxidant, and nutritional value of some leafy cabbage cultivars. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M. , Nahar, K., Alam, M. M., Roychowdhury, R., Fujita, M.. Physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms of heat stress tolerance in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 9643–9684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, Y. , Ren, X. N., Li, X. M.. Research progress on the effects of abiotic stress on plant carbohydrates and related enzymes in their metabolism. J. Anhui Agr. Sci. 2021, 49, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng D, Gao Q, Liu J, Tang J, Hua Z, Sun X, Categories of exogenous substances and their effect on alleviation of plant salt stress. European Journal of Agronomy 2023, 142, 126656. [CrossRef]

- Sun M, Li S, Gong Q, Xiao Y, Peng F. Leucine Contributes to Copper Stress Tolerance in Peach (Prunus persica) Seedlings by Enhancing Photosynthesis and the Antioxidant Defense System. Antioxidants. 2022, 11, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Su Y, Fan Y, Zuo D, Xu J, Liu Y, Mei X, Huang H, Yang M and Zhu S Exogenous leucine alleviates heat stress and improves saponin synthesis in Panax notoginseng by improving antioxidant capacity and maintaining metabolic homeostasis. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1175878. [CrossRef]

- Bayranvand M, Akbarinia M, Salehi Jouzani G, Gharechahi J, Baldrian P. Distribution of Soil Extracellular Enzymatic, Microbial, and Biological Functions in the C and N-Cycle Pathways Along a Forest Altitudinal Gradient. Front Microbiol. 2021, 12, 660603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlick PJ, The Role of Leucine in the Regulation of Protein Metabolism11. The Journal of Nutrition 2005, 135, 1553S–1556S. [CrossRef]

- Golia EE, Aslanidis PS, Papadimou SG, Kantzou OD, Chartodiplomenou MA, Lakiotis K, Androudi M, Tsiropoulos. Assessment of remediation of soils, moderately contaminated by potentially toxic metals, using different forms of carbon (charcoal, biochar, activated carbon). Impacts on contamination, metals availability and soil indices. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy 2022, 28, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kgathi, D.; Sekhwela, M.; Almendros, G. Changes in Soil Organic Matter Associated with Land Use of Arenosols from Southern Botswana. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matisic, M.; Dugan, I.; Bogunovic, I. Challenges in Sustainable Agriculture—The Role of Organic Amendments. Agriculture 2024, 14, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igalavithana, A.D.; Lee, S.S.; Niazi, N.K.; Lee, Y.-H.; Kim, K.H.; Park, J.-H.; Moon, D.H.; Ok, Y.S. Assessment of Soil Health in Urban Agriculture: Soil Enzymes and Microbial Properties. Sustainability 2017, 9, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliziani, G.; Bordoni, L.; Gabbianelli, R. Regenerative Organic Agriculture and Human Health: The Interconnection Between Soil, Food Quality, and Nutrition. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clunes J Pinochet, D. Leucine retention by the clay-sized mineral fraction. An indicator of C storage. Agro Sur 2020, 48, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alò, F. , Odriozola I., Baldrian P., Zucconi L., Ripa C., Cannone N., et al.. Microbial activity in alpine soils under climate change. Sci. Total Environ 2021, 783, 147012–10.1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, J. , Causeret F.. Changes in soil carbon inputs and outputs along a tropical altitudinal gradient of volcanic soils under intensive agriculture. Geoderma 2018, 320, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, D.L. , 1996. Methods of soil analysis part 3-chemical methods. Soil Science Society of America book series: 5. Wisconsin, U.S.A.

- Hou, S. , He, H., Zhang, W., Xie, H., & Zhang, X.. Determination of soil amino acids by high performance liquid chromatography-electro spray ionization-mass spectrometry derivatized with 6-aminoquinolyl-N-hydroxysuccinimidyl carbamate. Talanta 2009, 80, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D. L. , Owen, A. G., & Farrar, J. F.. Simple method to enable the high resolution determination of total free amino acids in soil solutions and soil extracts. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2002, 34, 1893–1902. [Google Scholar]

- Ionela Raluca Comnea-Stancu, I. R. , Stefan-van Staden, R. I., & van Staden, J. K. F. Enantioanalysis of Leucine and Arginine: A Key Factor in Lung Cancer Metabolomics. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2024, 171, 067513. [Google Scholar]

- García-Carmona, L. , González, M. C., & Escarpa, A.. Electrochemical On-site Amino Acids Detection of Maple Syrup Urine Disease Using Vertically Aligned Nickel Nanowires. Electroanalysis 2018, 30, 1505–1510. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M. M. , Rahman, M. M., & Asiri, A. M.. Sensitive L-leucine sensor based on a glassy carbon electrode modified with SrO nanorods. Microchimica Acta 2016, 183, 3265–3273. [Google Scholar]

- Stefan-van Staden, R. I. , & Shirley Muvhulawa, L.. Determination of L-and D-Enantiomers of Leucine Using Amperometric Biosensors Based on Diamond Paste. Instrumentation Science and Technology 2006, 34, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labroo, P. , & Cui, Y. Amperometric bienzyme screen-printed biosensor for the determination of leucine. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 2014, 406, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rezaei, B. , & Zare, Z. M.. Modified glassy carbon electrode with multiwall carbon nanotubes as a voltammetric sensor for determination of leucine in biological and pharmaceutical samples. Analytical letters 2008, 41, 2267–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karastogianni, S.; Girousi, S. Electrochemical (Bio)Sensing of Maple Syrup Urine Disease Biomarkers Pointing to Early Diagnosis: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luscombe, N. M. , Laskowski, R. A., & Thornton, J. M. Amino acid–base interactions: a three-dimensional analysis of protein–DNA interactions at an atomic level. Nucleic acids research 2001, 29, 2860–2874. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.-T.; Malik, F. Single-Stranded DNA Binding Proteins and Their Identification Using Machine Learning-Based Approaches. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, C. T. , Campbell, B. A., & Elcock, A. H. Direct comparison of amino acid and salt interactions with double-stranded and single-stranded DNA from explicit-solvent molecular dynamics simulations. Journal of chemical theory and computation 2017, 13, 1794–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M. , Malik, F. K., & Guo, J. T. A comparative study of protein–ssDNA interactions. NAR genomics and bioinformatics 2021, 3, lqab006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, A. , Shimer, G., Jr., and Meehan, T. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons physically intercalaye into duplex regions of denaturated DNA. Biochemistry 1987, 26, 6392–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherghi, I.Ch. , Girousi, S.Th., Pantazaki, A.A., Voulgaropoulos, A.N., Tzimou-Tsitouridou, R. Electrochemical DNA biosensors applicable to the study of interactions between DNA and DNA intercalators. International Journal of Environmental Analytical Chemistry 2003, 83, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ch. Gherghi, S.Th. Girousi, A. N. Voulgaropoulos, R.Tzimou-Tsitouridou Interaction of the mutagen ethidium bromide (EB) with DNA, using a carbon paste electrode (CPE) and a Hanging mercury drop electrode (HMDE). Analytica chimica Acta 2004, 505, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ch. Gherghi, S.T. Girousi, A. N. Voulgaropoulos, R.Tzimou-Tsitouridou Adsorptive transfer stripping voltammetry applied to the study of the interaction between DNA and actinomycin D. International Journal of Environmental Analytical Chemistry 2004, 84, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Karastogianni, C. Dendrinou-Samara, E. Ioannou, CP Raptopoulou, D Hadjipavlou-Litina, S Girousi Synthesis, characterization, DNA binding properties and antioxidant activity of a manganese (II) complex with NO6 chromophore. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 2013, 118, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ch. Gherghi, S.T.Girousi, A. N.Voulgaropoulos, R Tzimou-Tsitouridou DNA modified carbon paste electrode applied to the voltammetric study of the interaction between DNA and acridine orange. Chemia analityczna. 2004, 49, 467. [Google Scholar]

- Wen Li, Yuan Yuan Ji, Jian Wen Wang, Yong Ming Zhu Cytotoxic Activities and DNA Binding Properties of 1-Methyl-7H-indeno[1,2-b]Quinolinium-7-(4-dimethylamino) Benzylidene Triflate DNA. Cell Biol 2012, 31, 1046–1053. [CrossRef]

- Werdin-Pfisterer, Ν. R, Kielland K, Boone RD Soil amino acid composition across a boreal forest successional sequence. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2009, 41, 1210–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantigny, M. H. , Olk, D. C., & Angers, D. A. Investigating the nature of soil carbohydrates and amino compounds with liquid chromatography. Soil Science Society of America Journal 2025, 89, e70018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Application | LOD mol/L |

Linearity mol/L |

Electrode |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [20] | Blood | 3 × 10−12 | 10−11 - 10−8 | α-CD/ZnO/nanoC |

| [21] | 8× 10−16 | 25-700x10−6 | v-NiNWs | |

| [22] | spiked urine, milk and serum | 37.5 ± 0.2 10−12 | 0,1-100x10−9 | SrO NR |

| [23] | - | Diamond paste | ||

| [24] | - | 2 x10−6 | 10 - 600 x10−6 | Amperometric bienzyme ScPE |

| [25] | blood, urine samples | 3.0 × 10−6 | 9.0 × 10−6 − 5 × 10−3 | MWNTs |

| This work | spiked soil | 4,9.10-10 | 1,4.10-9 - 3,5.10-8 | CPE/ssDNA |

| Recovery, R% at 3 μg L−1 | Interfering aminoacid |

|---|---|

| 100,00 | Leucine |

| 108,75 | Isoleucine |

| 100,95 | Valine |

| 102,4 | Phenylalanine |

| 97,63 | Methionine |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).