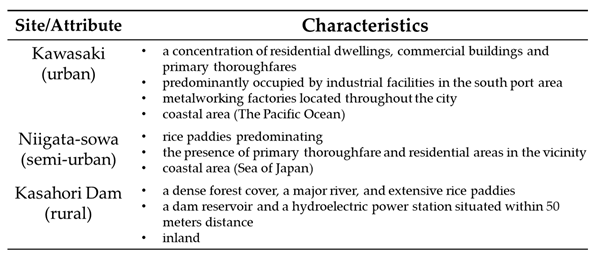

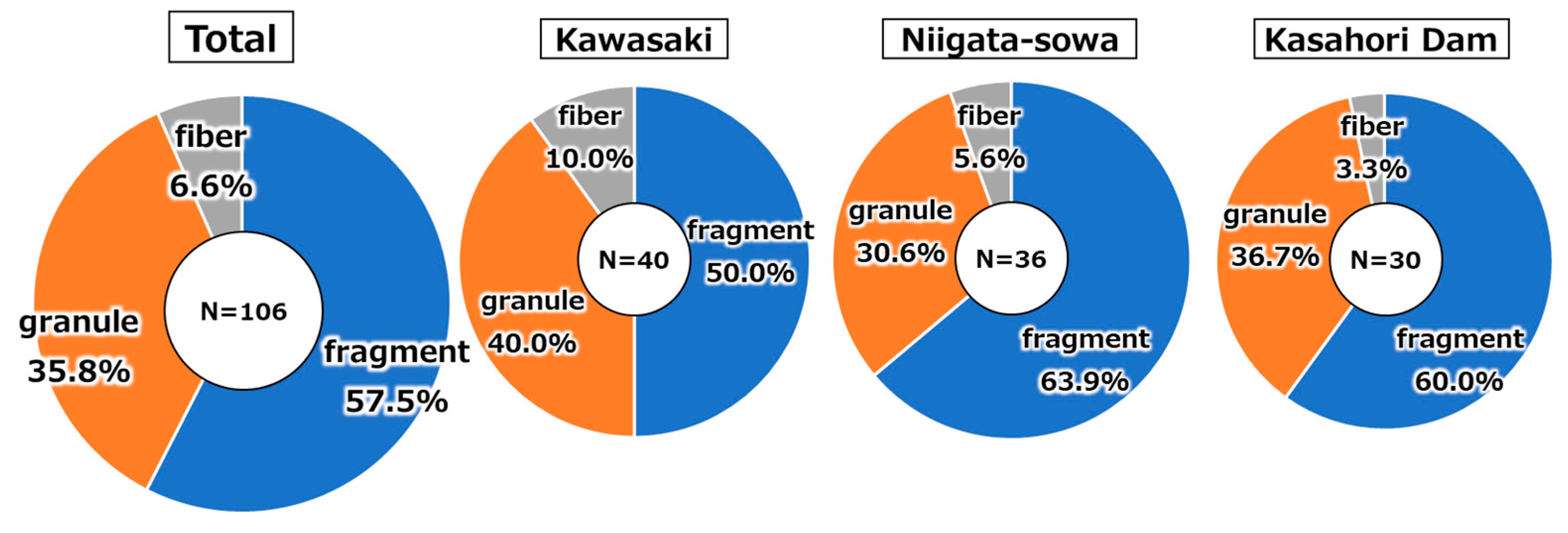

3.1. Comparative Overview of AMNPs and Major PM Components

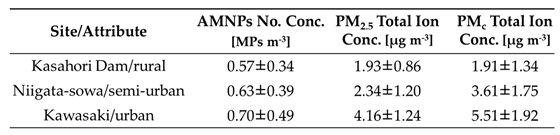

Table 2 presents the annual average values of the AMNP number concentrations and the total ion mass concentrations of PM

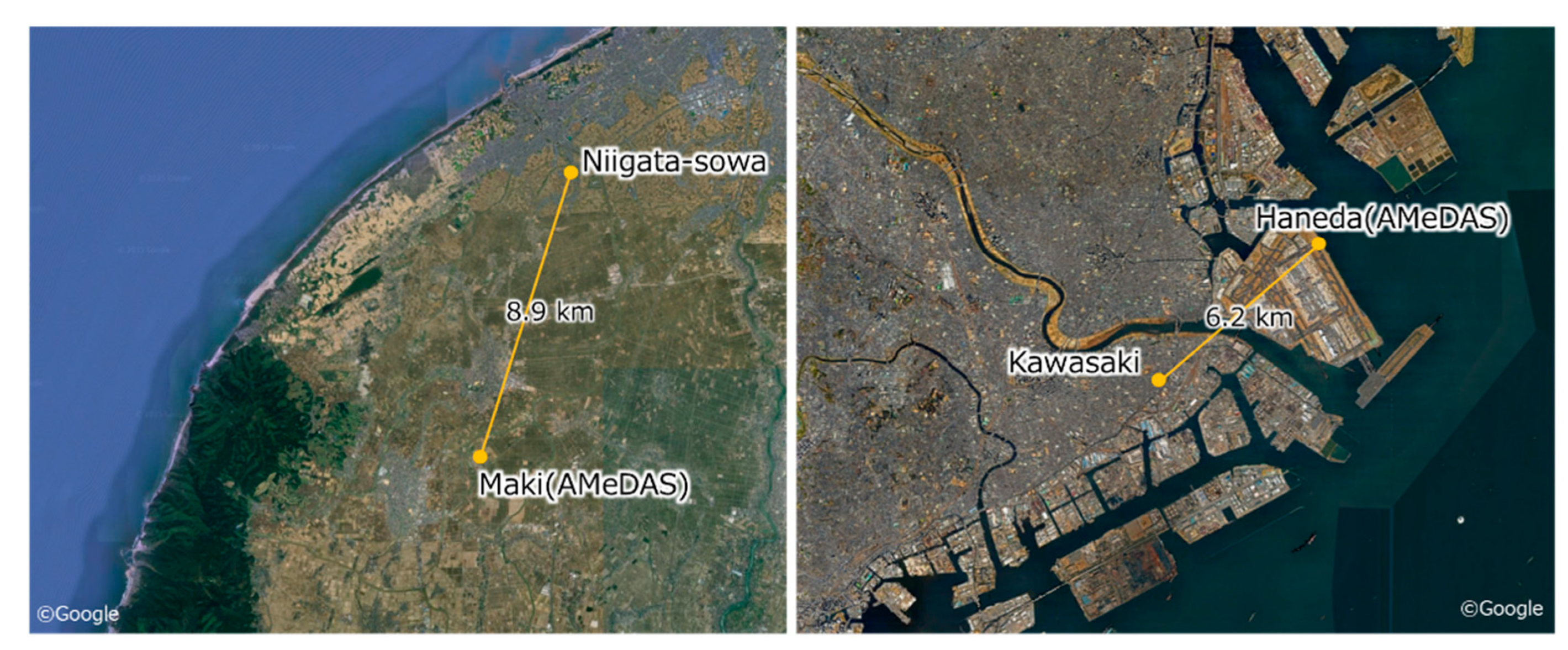

2.5 and PM

c for each sampling site. As stated in the previous studies, soluble inorganic ions have been found to comprise as much as 60-70% of the total mass of suspended particulate matter [

65], and 30-50% of the total PM

2.5 mass [

66,

67]. Given that ion components are widely regarded as the predominant constituents of PM, ion mass concentrations were utilized as metrics to comparatively analyze AMNPs and PM. A comparison with the results of previous studies that also employed the active sampling method revealed that the AMNPs number concentrations ranged from 0.01 to 5,650 MP m

-3 (N = 13, median: 2.9 MP m

-3) [

12,

14,

27,

34,

39,

55,

68,

69,

70,

71]. Notably, the results for all three locations fell within this range, indicating a consistency in the findings across different study sites. Focusing on the comparison of concentrations between PM and AMNPs, the concentrations were Kawasaki, Niigata-sowa, and Kasahori Dam in descending order, a commonality observed across all three items (i.e., AMNPs, PM

2.5, and PM

c). While the concentration differences among the three sites proved to be statistically significant for both PM

2.5 and PM

c (N = 15 for Kawasaki, N = 16 for the other two sites,

p < 0.05), no significant differences were detected in the AMNPs number concentration (N = 16 each,

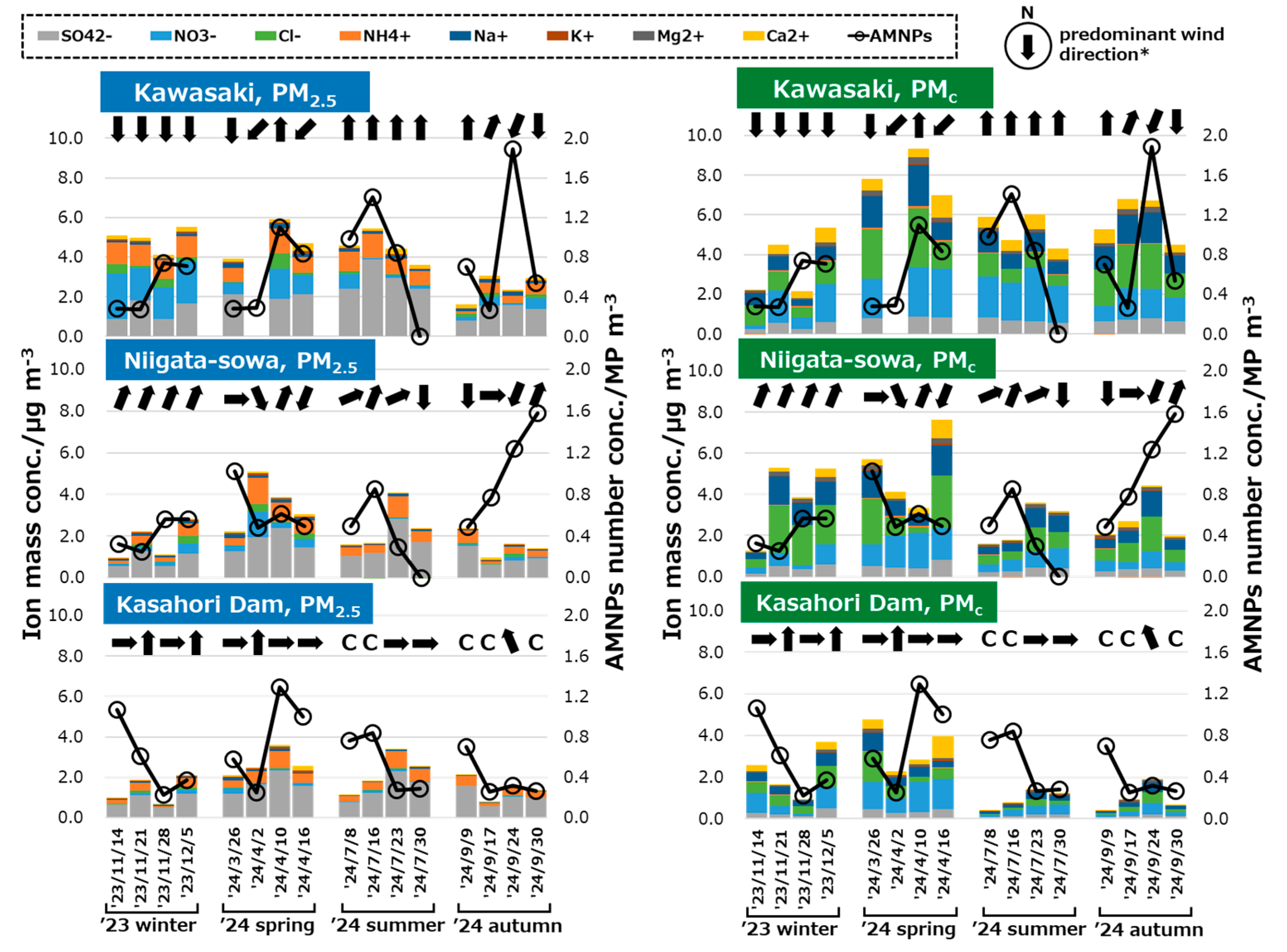

p > 0.05). Weekly fluctuations of AMNPs number concentrations, ion mass concentrations of PM

2.5/PM

c, and the predominant wind directions at each sampling site were delineated in

Figure A3. Although seasonal fluctuation was observed, PM

2.5 tended to have a relatively high proportion of SO₄²⁻ and NH₄, while PM

c tended to have a relatively high proportion of Cl⁻, Na⁺, and Ca

2+ regardless of the locations, which is consistent with previous studies [

59,

65,

66,

67]. However, no clear correlation was observed between total ion mass concentration of PM

2.5/PM

c and AMNP number concentration at any location. According to the Japan Meteorological Agency, dust and sandstorms (DSS) originating from mainland China were observed during December 5-12, 2023, and April 16-23, 2024, respectively [

72]. While the PM

c mass concentration of Ca²⁺, which is known as part of the major components of DSS, was relatively elevated at three sampling sites, there was no significant increase in the number concentration of AMNPs during both periods.

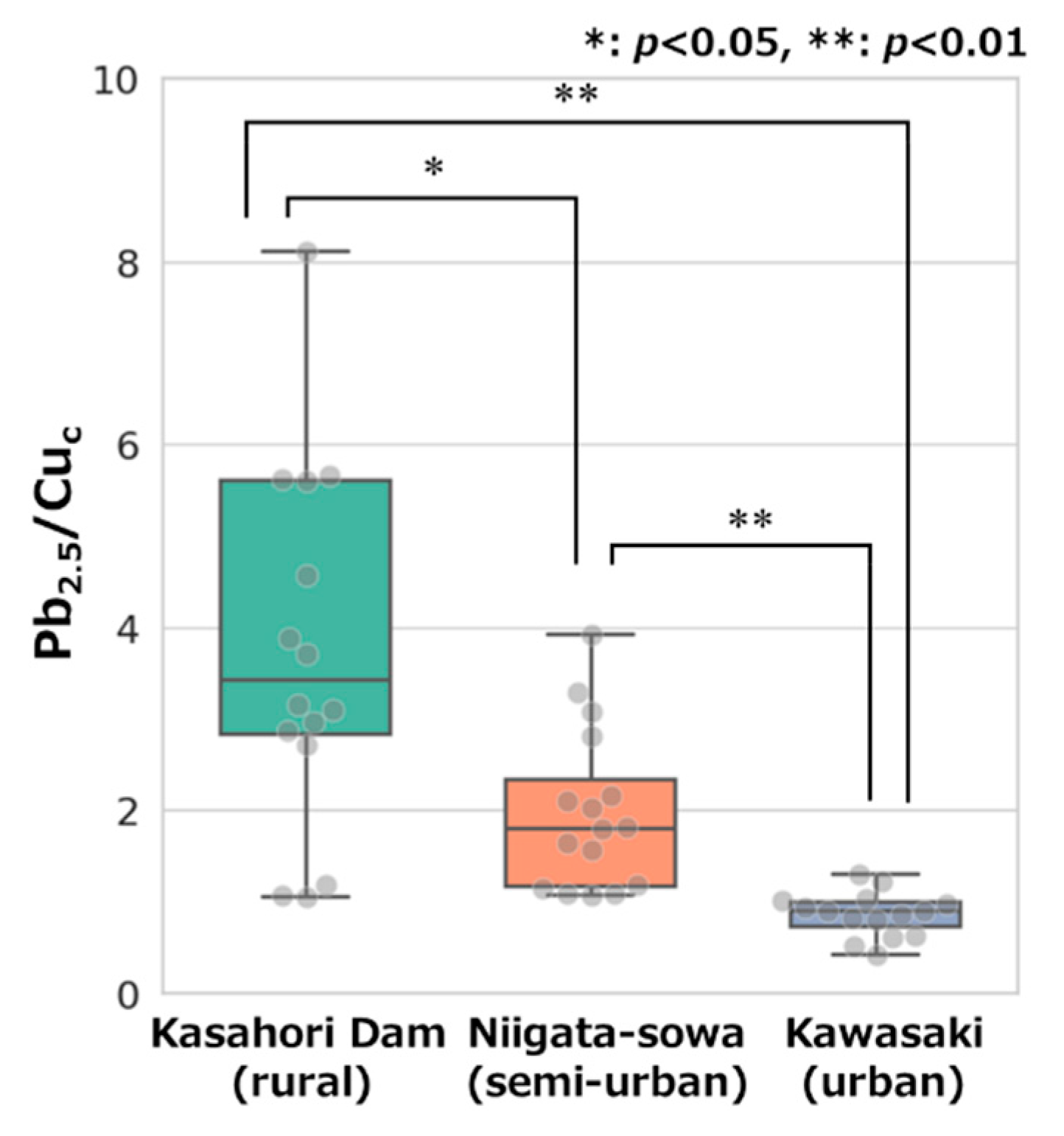

In the context of PM source analysis, the concentrations and ratios of inorganic elements have been employed, which are less susceptible to compositional changes by chemical reactions during a long-term transportation in the atmosphere [

73]. Taniguchi

et al. directed their attention to the ratio of Pb mass concentration in fine particles to that of Cu in coarse particles (Pb/Cu), reporting the efficacy of Pb/Cu as an indicator of transboundary and local air pollution, with a particular emphasis on the emissions from coal combustion and motor vehicle traffic, respectively [

58]. In this study, the mass concentration ratio of Pb in PM

2.5 to Cu in PM

c (Pb

2.5/Cu

c) was utilized, and the values for each sampling site were displayed in

Figure 4 as box and whisker plots. The mean Pb

2.5/Cu

c values at the three sampling sites were highest at Kasahori Dam, followed by Niigata-sowa and Kawasaki. Furthermore, statistically significant differences in the mean Pb

2.5/Cu

c values were observed among the three sites (

p < 0.05 or

p < 0.01). This tendency for Pb/Cu values to be higher in rural areas and lower in urban areas has been reported in the previous study and is consistent with the results of this study [

58].

In consideration of the findings, the conditions of air pollution, as indicated by the ion mass concentrations—the primary constituent of PM—and the indicator defined by the mass concentration ratio of inorganic elements, were found to be generally consistent with the attributes assigned to each location. In contrast, the relationships between AMNPs number concentrations and site attributes were unclear. Therefore, it was hypothesized that there might be little correlation between AMNPs concentrations and conventional site attributes defined by concentration level of air pollutants like PM on a macroscopic level, suggesting that AMNPs pollution may be occurring at the same level in the rural, semi-urban, and urban area. It was also indicated that AMNP dynamics are influenced by additional factors beyond conventional particulate matter processes, and may not be directly inferred from PM behavior alone.

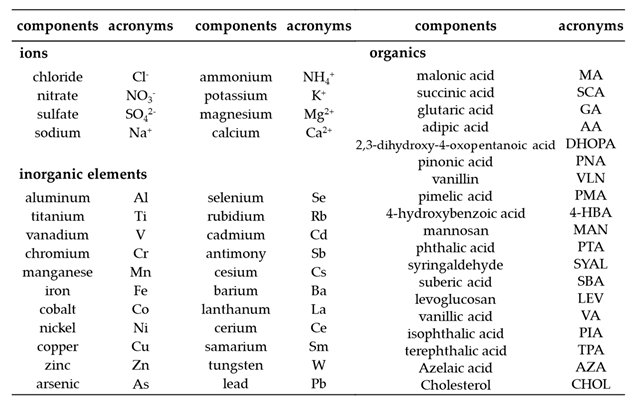

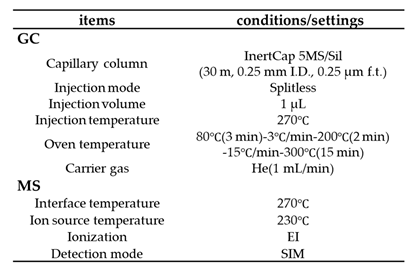

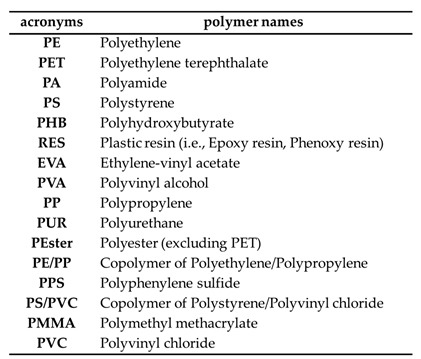

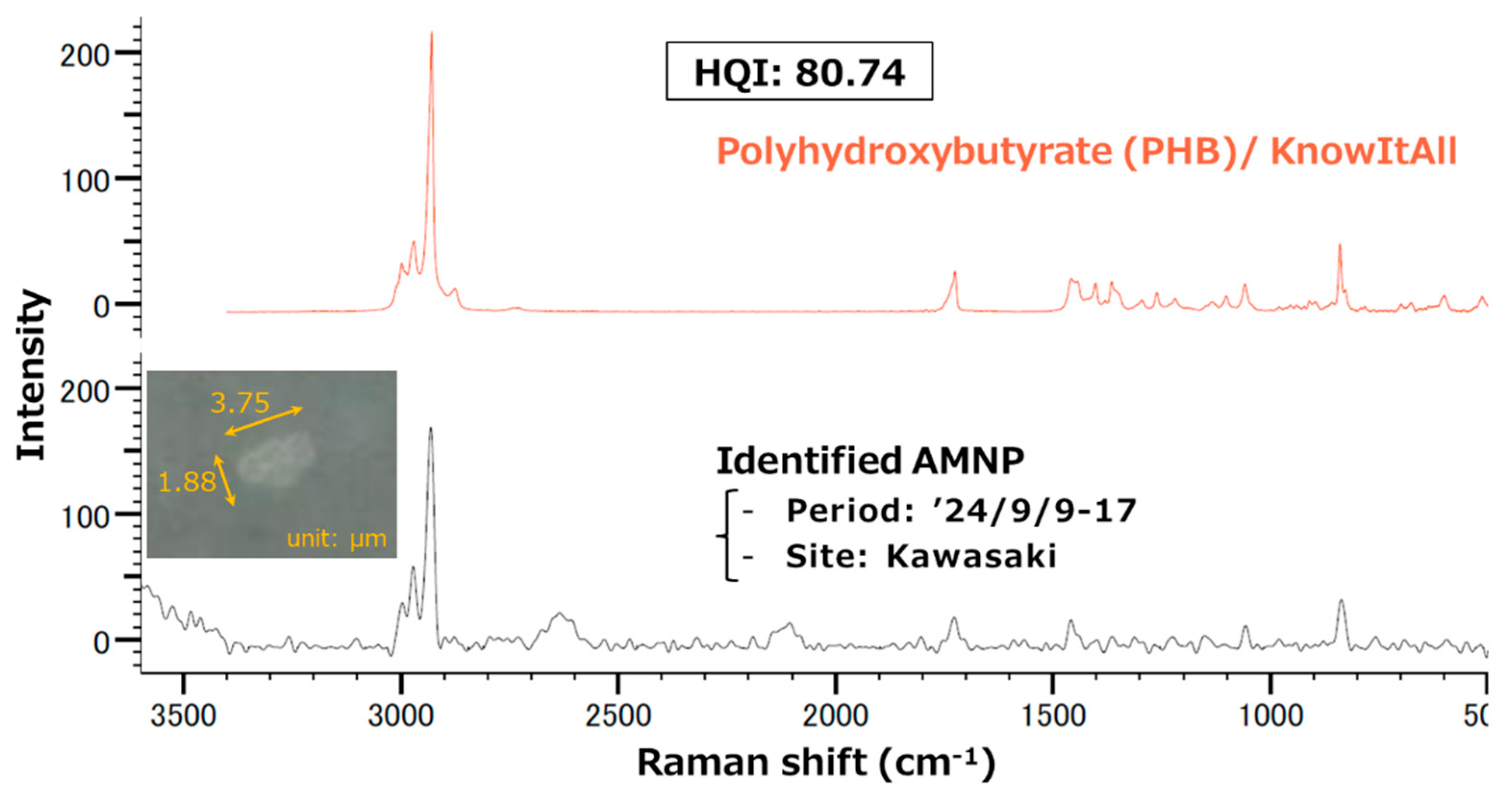

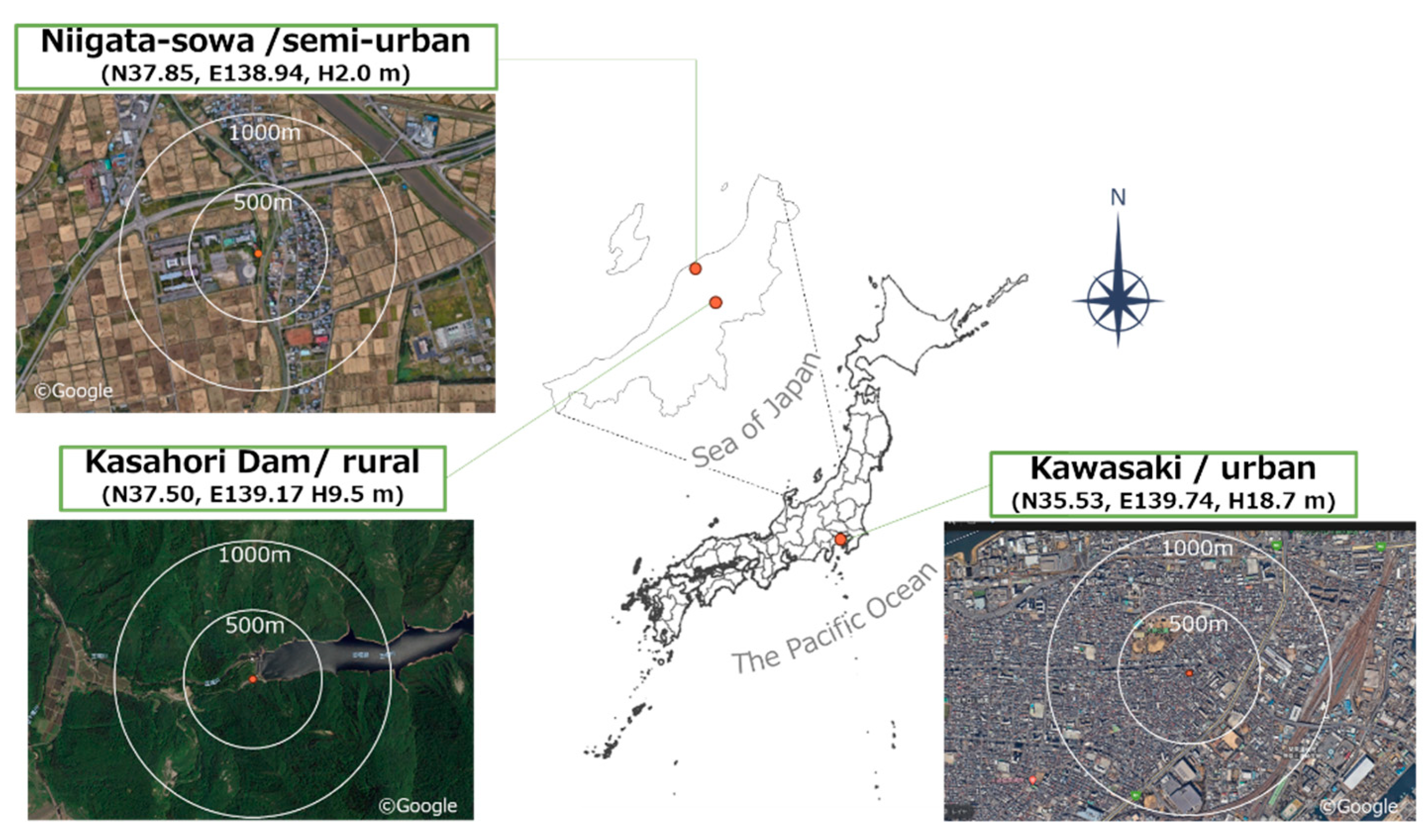

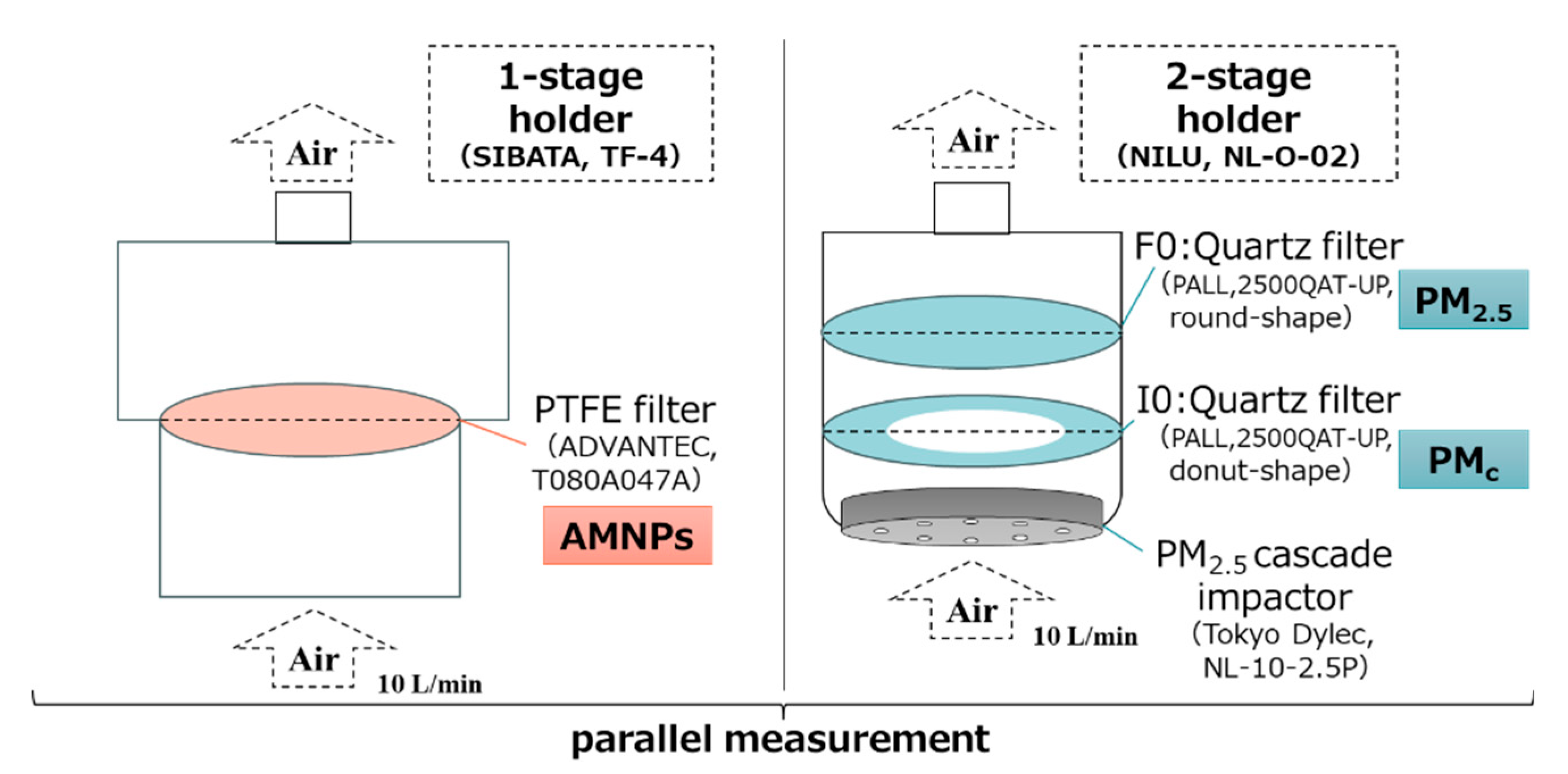

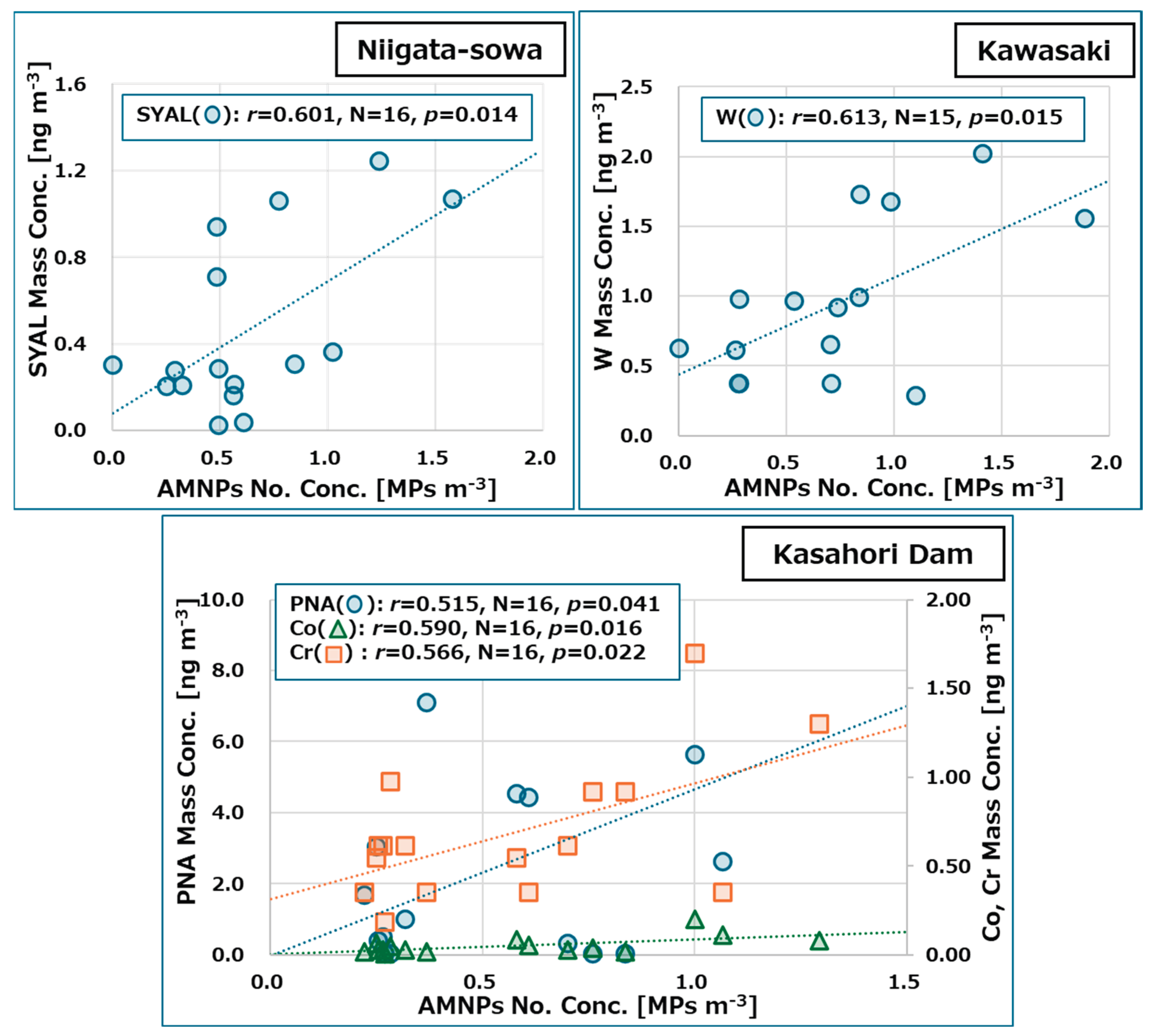

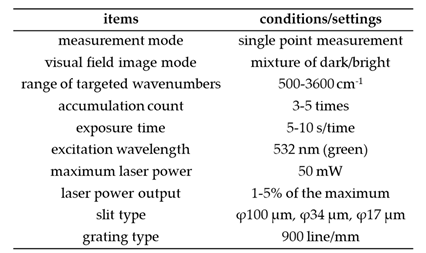

3.3. Exploratory Analysis of Potential Sources via Simple Regression

As illustrated in

Figure 7, the scatter plots and linear approximation curves for mass concentrations of PM

2.5 components exhibited statistically significant positive correlations (

p < 0.05) with the number concentration of AMNPs, based on their geographical location. The figure also presented the number of samples (N), the correlation coefficients (

r), and the p-values (

p). No statistically significant correlations were identified for other PM

2.5 components and meteorological parameters (

p > 0.05).

In Niigata-sowa, a relatively strong correlation between AMNPs number concentration and syringaldehyde (SYAL) mass concentration was observed. SYAL is one of the aldehydes yielded by the fragmentation or depolymerization of lignin, which constitutes 20% of the global biomass [

84]. SYAL is also recognized as an organic marker of PM

2.5 components resulting from biomass combustion [

85]. As previously stated in

Section 2.1.1, Niigata-sowa is located in an area characterized by extensive rice cultivation, with sporadic occurrences of open burning of residual rice straw following the harvest. Additionally, the mass concentration of SYAL exhibited a robust correlation with that of vanillin (VLN;

r = 0.84), which is also an aldehyde derived from lignin. In light of the findings, a correlation between AMNPs and the open burning events of biomass containing rice straw was hypothesized. As Kirchsteiger et al. reported, certain types of AMNPs—namely, those composed of PE or PP—were suggested to function as carriers for specific PAHs contained in PM

2.5 [

40]. Despite the fact that this study focused on disparate organic components, there is a possibility that it captured phenomena analogous to those reported in the aforementioned study, specifically working as carriers for PM organic components. However, it should be noted that no significant correlation was found between AMNPs and other biomass combustion markers such as levoglucosan (LEV) and mannosan (MAN), nor terephthalic acid (TPA) as a plastic combustion marker (

p > 0.05) [

86]. Furthermore, it is also important to note that a direct comparison between this study and the aforementioned report is precluded by the difference in sampling durations (approximately 7 days and 24 hours, respectively).

In Kawasaki, a relatively strong correlation between AMNPs number concentration and tungsten (W) mass concentration was observed. W has garnered significant attention for its exceptional performance across a wide range of applications, from household items to cutting-edge research, manufacturing, and military fields. The primary products encompass tungsten carbide, alloys, corrosion-resistant coatings, catalysts, semiconductors, fire-resistant compounds, electrical and electronic products, lighting, and so on [

87]. W has minimal natural presence in the atmosphere; however, anthropogenic activities have the potential to cause elevated levels of W [

88]. In this study, the mean mass concentration of W in PM

2.5 at each location was determined to be 0.94 ± 0.56 ng m

-3 in Kawasaki, 0.33 ± 0.24 ng m

-3 in Niigata-sowa, and 0.25 ± 0.19 ng m

-3 in Kasahori Dam (N = 15 for Kawasaki, N = 16 for the other two sites). A significant discrepancy was identified in the W mass concentration in Kawasaki when compared with the concentrations observed in the other two locations (

p < 0.01), while the differences between Niigata-Sowa and Kasahori Dam were not found to be statistically significant (

p > 0.05). As previously stated in

Section 2.1.1, Kawasaki is the most urban of the three locations, with factories in the port area and small factories engaged in lathe work scattered throughout residential areas. Additionally, the sampling site is situated adjacent to a major thoroughfare, which results in significant vehicular traffic. Consequently, it was considered that the atmospheric concentration levels of W at the three locations were influenced by site attributes, particularly the number and types of anthropogenic sources. In contrast, the nature of the interaction between W and AMNPs remains elucidated. As indicated by earlier studies, the presence of heavy metals on the surface of microplastics can be attributable to the plastics’ inherent adsorbent properties, although these behaviors are influenced by various factors [

89,

90]. However, it is imperative to acknowledge that the aforementioned studies exclusively focused on interactions occurring in aqueous solutions and did not address interactions that may occur in the atmosphere, as well as W was not focused on.

In Kasahori Dam, relatively strong correlations between AMNPs number concentration and mass concentrations of cobalt (Co), chromium (Cr), and pinonic acid (PNA) were observed, respectively. Co is a metal that has a variety of applications, including use in pigments, lithium-ion battery electrodes, ceramic paints and glazes, battery manufacturing, and incinerators. It was observed that the mass concentration of this metal in PM

2.5 increases significantly in association with anthropogenic sources [

91]. Cr is regarded as a constituent of PM

2.5, with its primary sources being coal combustion, industry, and transportation (e.g., vehicle tailpipes, brakes, and tire wear) , and is believed to be significantly associated with human activities [

92]. In this study, a significant discrepancy was identified in both Co and Cr mass concentration in Kawasaki when compared with the concentrations observed in the other two locations (

p < 0.01), while the differences between Niigata-Sowa and Kasahori Dam were not found to be statistically significant (

p > 0.05), which was consistent with the previous reports mentioned above. In contrast, as discussed in

Section 2.1.1, the Kasahori Dam is situated in a region with minimal artificial sources and alternative explanations are imperative when discussing the relationship between Co or Cr mass concentrations and AMNP number concentrations. Cr is known to be incorporated into plastics as a coloring pigment [

93], and there were a few reports of the presence of heavy metals, including Co and Cr, in MNPs found in the aquatic environments [

94,

95]. Consequently, at the Kasahori Dam, where anthropogenic sources are limited, it was hypothesized that the correlation between heavy metals adsorbed to AMNPs, whether intentionally or unintentionally, was comparatively robust in comparison to PM tracer components. PNA is classified as a monoterpene tracer due to its synthesis as a secondary product of α-pinene, which is known as one of the biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOC), through photochemical oxidation. According to the extant literature, there was an increase in PNA concentrations during the warm season, concurrent with the period of active vegetation [

96]. However, in this study, PNA concentrations were lowest in summer, and this trend was also observed at the other two locations (see

Table A5), which stood in contrast to the results of the aforementioned report. A previous study demonstrated that PNA exhibited high volatility and predominantly existed in gaseous form at temperatures ranging from 275 to 300 Kelvin [

97]. Additionally, it was also reported that gaseous PNA was adsorbed onto quartz fiber filter paper and was barely collected as particles under a 24-hour sampling duration [

98]. Consequently, it was postulated that the mass concentration variation of PNA in this study was significantly influenced by the artifacts such as gas adsorption, thereby challenging the discussion of its correlation with the number concentration of AMNPs.

In light of the aforementioned results and discussion, it was concluded that the utilization of PM tracer components to elucidate the true state of AMNPs yielded insights that were instrumental in the estimation of emission sources or analogous information. However, it was also recognized that exploring more effective methods for estimating the source of emissions, including avoiding the influence of artifacts and performing multivariate analysis with an increased number of samples rather than simple regression analysis, was necessary.

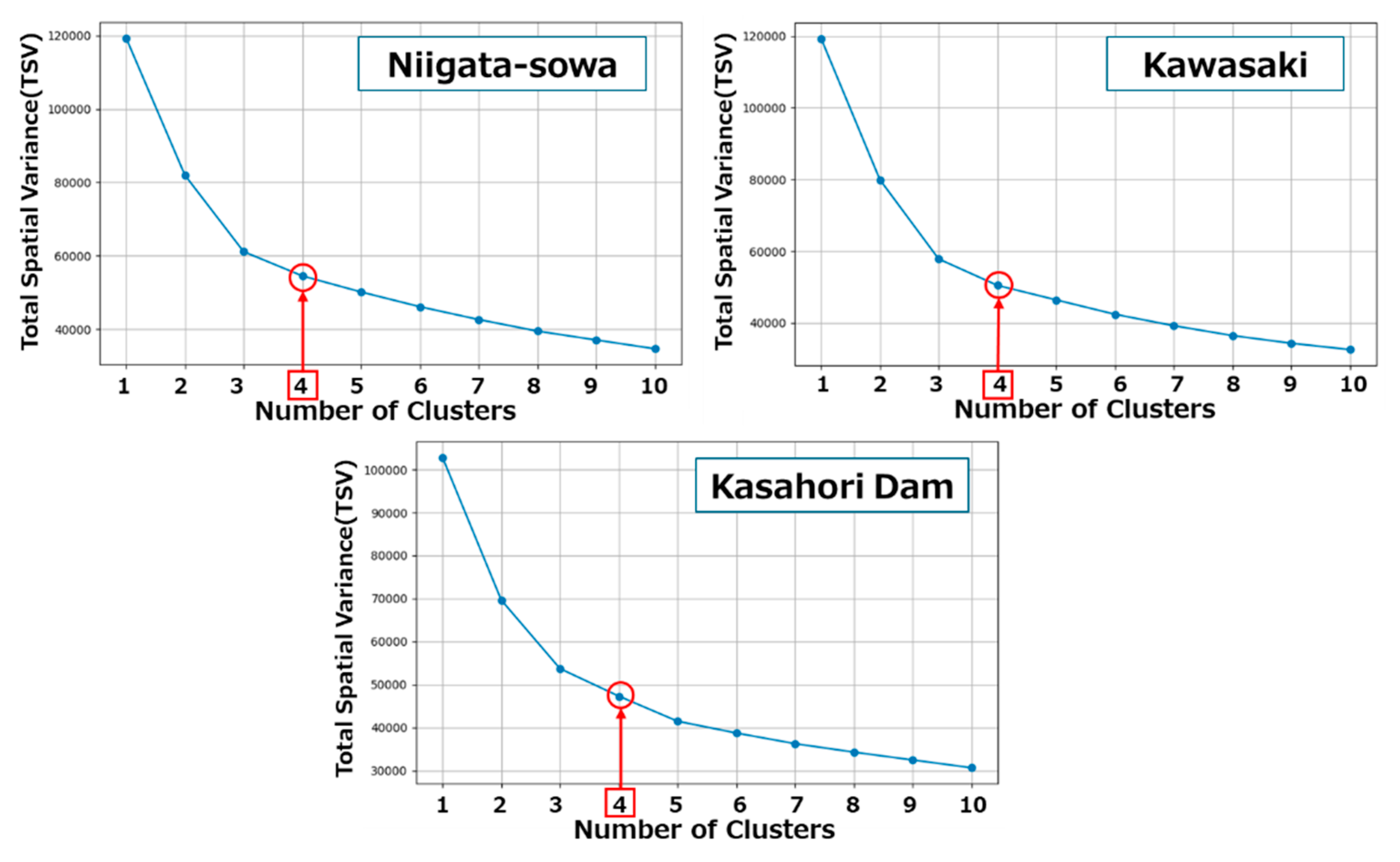

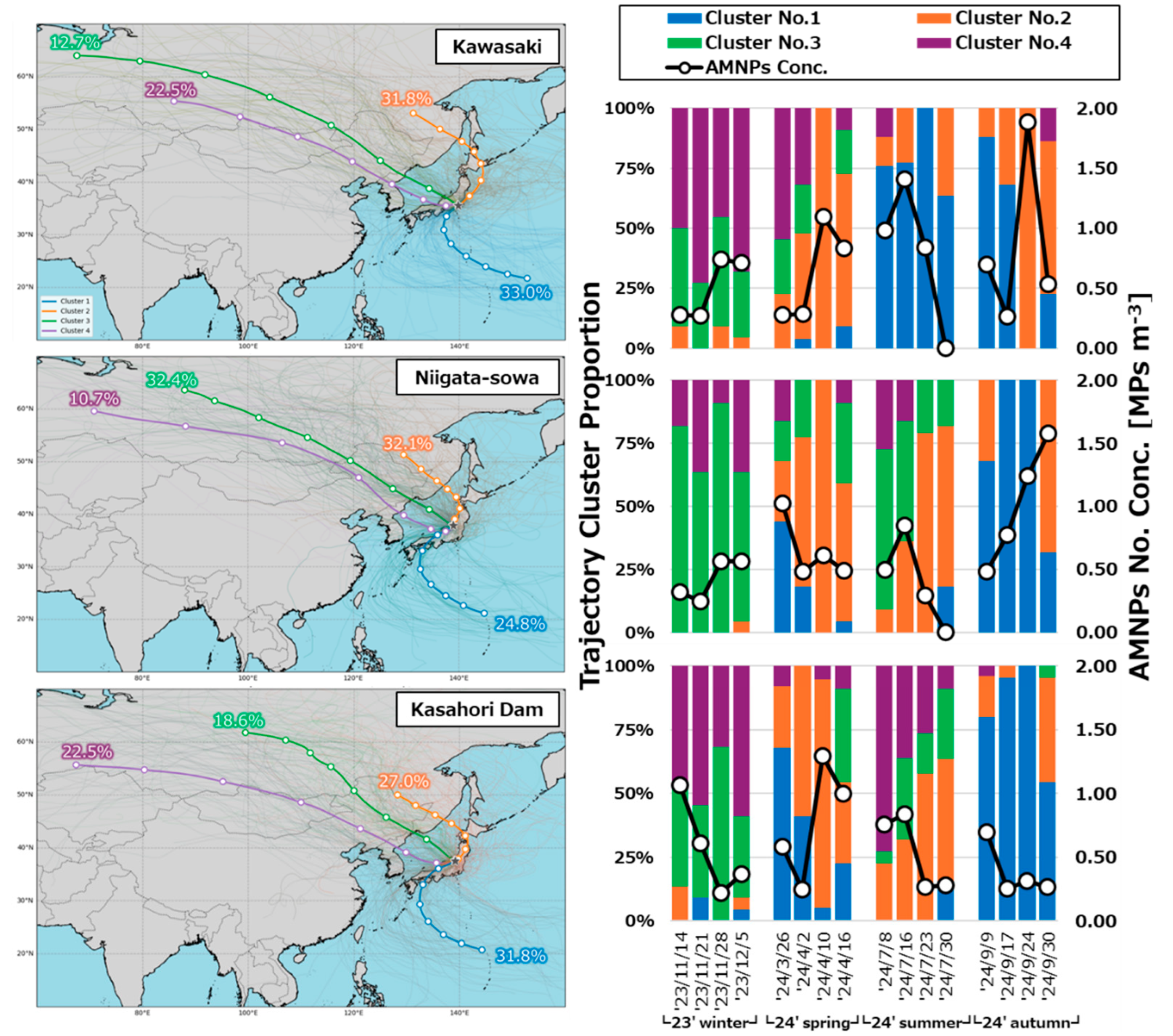

3.4. Back-Trajectory Clustering and Its Implication for AMNP Transport

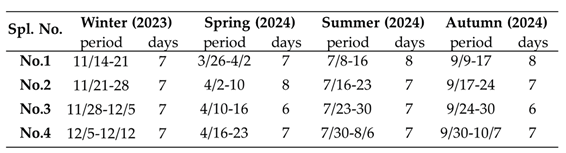

As delineated in

Figure 8, the plan views of trajectory clusters (Nos. 1 to 4) at each location, as well as their presence ratio throughout the year and on a weekly basis were presented. As delineated in

Section 2.4.2, the optimal number of clusters was determined to be four for each location. Despite the presence of minor variations in trajectory clusters across different locations, a generalizable summary of each trajectory is as follows.

Cluster No.1: Air masses flowing into Japan from the southeast, circling around the periphery of Pacific high.

Cluster No.2: Air masses flowing into Japan from the north to northwest via Primorsky Krai in Russia.

Cluster No.3: Air masses flowing into Japan from the northwest via Siberia and northeastern China.

Cluster No.4: Air masses, located slightly south of Cluster No.3, flowing into Japan via Siberia, Mongolia, northeastern China, the Korean Peninsula.

It was observed that, across all locations, Cluster No.3 and 4 exhibited a tendency to predominate during the winter season, while Cluster No.2 demonstrated a similar tendency during the spring season. Additionally, both Clusters No.1 and 2 were predominant during the autumn season. In Kawasaki, located on the Pacific coast, the air masses classified as Cluster No.1 accounted for one-third of the total amount, which was particularly significant in summer. Conversely, Niigata-sowa, situated on the Sea of Japan, exhibited a slightly lower frequency of Cluster No.1 compared to Kawasaki, while Clusters No.2 to 4 demonstrated relatively high frequencies. At Kasahori Dam, which is situated on the Sea of Japan side but inland, the cluster distribution was intermediate between that of Niigata-sowa and Kawasaki. In the summer season, the presence of air masses belonging to Cluster No.1 in Niigata-sowa and Kasahori Dam on the Sea of Japan side was infrequent, in contrast to the patterns observed in Kawasaki. Although the aforementioned back trajectory clustering demonstrated some reasonable results, no substantial correlation was identified between the concentration of AMNPs and the incidence rate of each cluster at each sampling site (p > 0.05). In Niigata-sowa, a quasi-significant correlation (r = 0.47, p = 0.065) with the occurrence rate of Cluster No. 1 was obtained, and the possibility that AMNPs flowed in due to air masses corresponding to the peripheral flow of Pacific high cannot be ruled out. However, given that the aforementioned trend was not observed at the other two locations and that the mass concentration of tracer components that exhibited a significant correlation with the number concentration of AMNPs differed at each location as discussed in Section 3.3.3, it was suggested that local or site-specific factors, rather than transboundary and long-range factors, were predominant in the context of air pollution by AMNPs. In general, particles of smaller size demonstrate a greater propensity to travel over greater distances. Therefore, in the context of the future prospects, the contribution rates of local and transboundary air pollution might be predicted through the aerodynamic size-fractionated sampling of AMNPs.