Submitted:

08 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

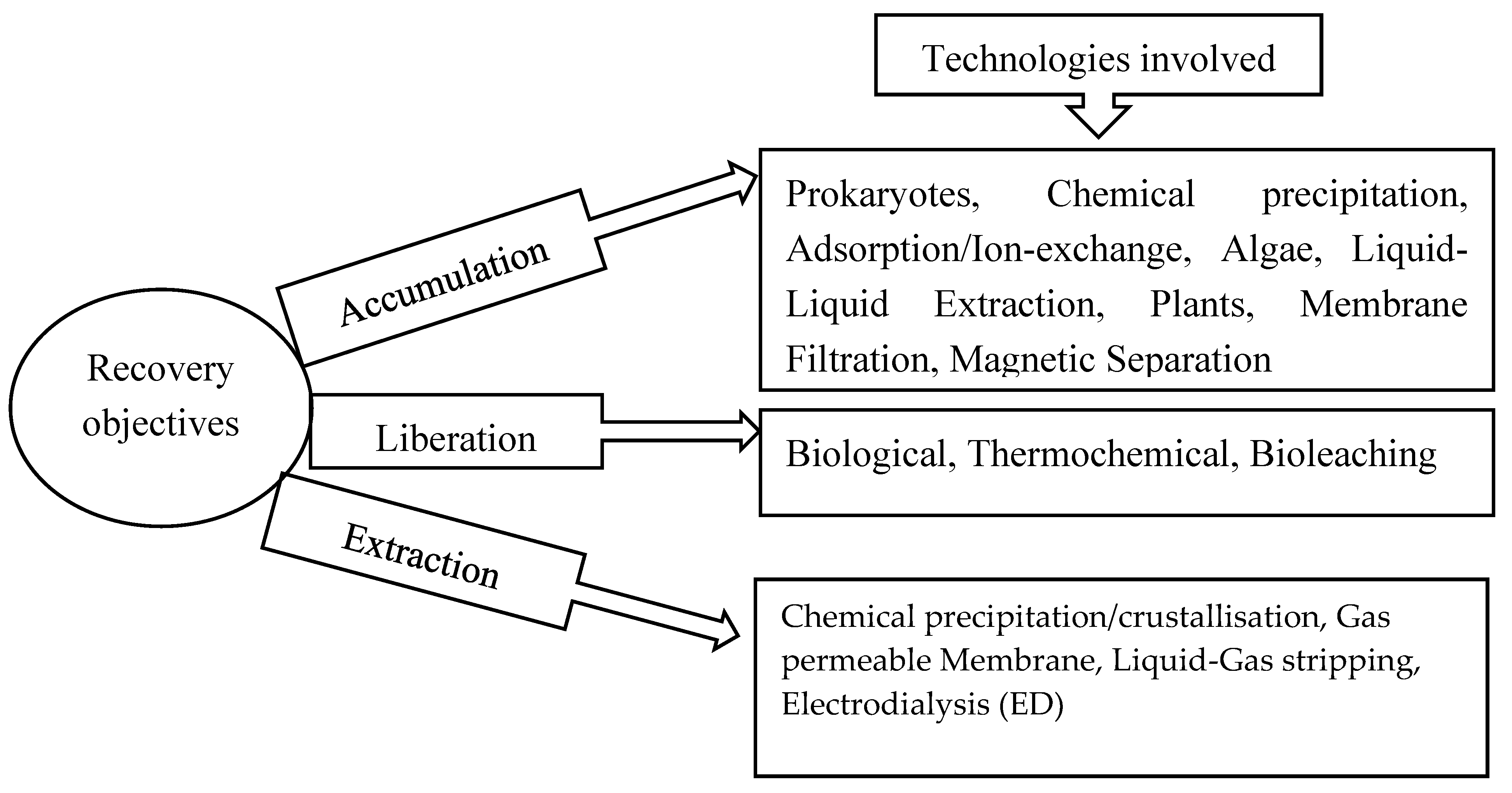

2. Technologies for the Removal of OC and Nutrients from Wastewater

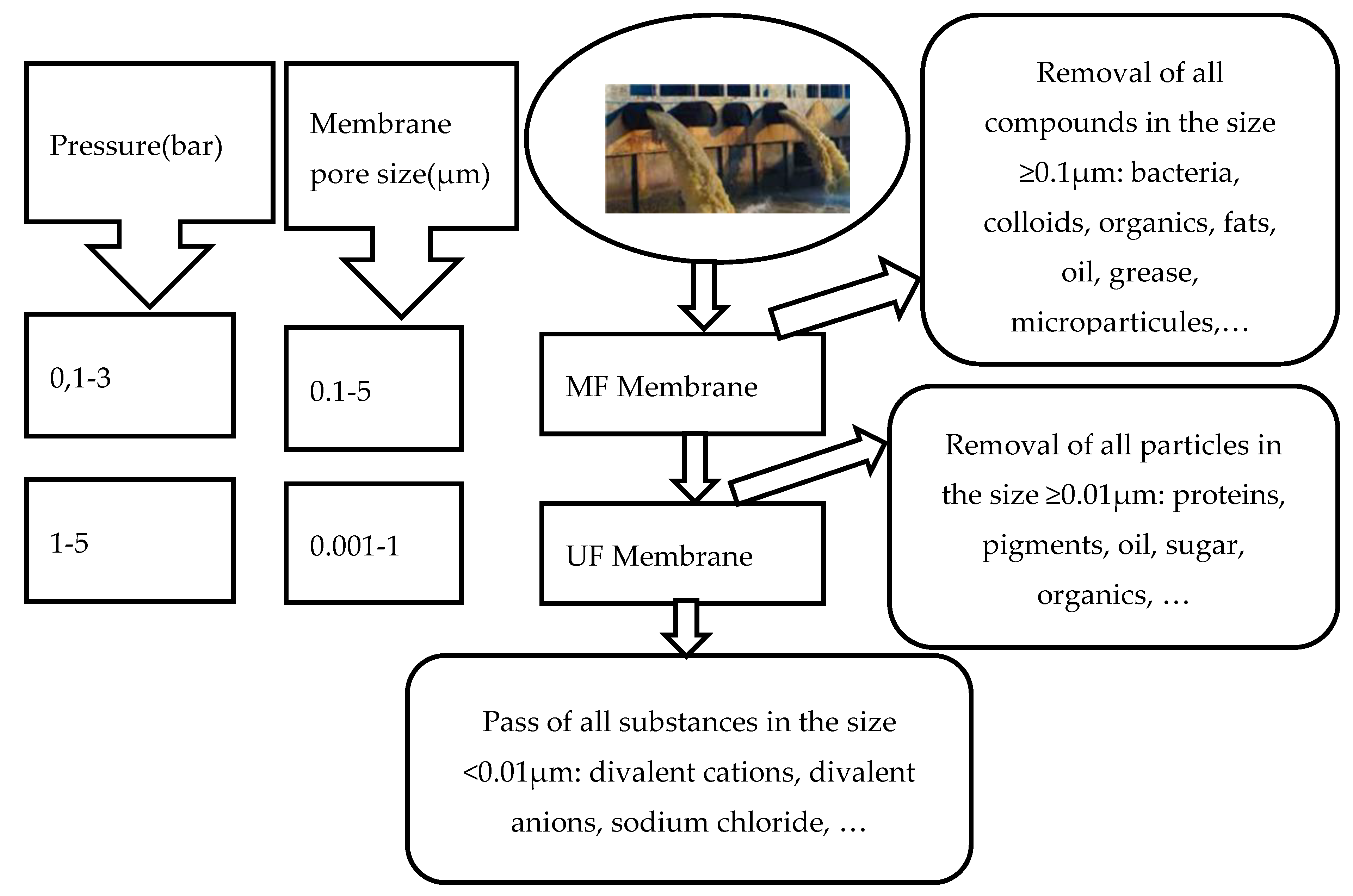

2.1. Removal Efficiency of OC from Liquid Waste by Using MF Membrane

2.2. Removal Efficiency of OC from Liquid Waste by Using UF Membranes

| Wastewater | Membrane material | Removal rate | References |

| Oil and grease | PS and a polyacrylonitrile (PAN) | 96.3% in TOC | [72] |

| Oily | PS | 99.7% in TOC | [73] |

| Municipal | Stainless steel | up to 50% in terms of COD and TOC | [74] |

| Oily | PVDF | 98% in TOC | [75] |

| Oily | PS | 93,5% in TOC | [73] |

| Vegetable oil | PS | 87% in TOC | [76] |

| Poultry Slaughterhouse | PES | 8.8% of COD | [16] |

| Influent from the treatment plant | PVDF | 78% of COD and 91% of BOD5 | [77] |

| Pig manure | PVDF | Total COD mg/L= 15000 | [78] |

| Sieved and settled manure supernatant (SAS) | PVDF | Total COD mg/L= 20000 | [78] |

| Sieved, biologically treated and SBS | PVDF | Total COD mg/L= 160 | [78] |

| Biologically treated wastewater | Zirconium oxide | 52% of COD; 45% of BOD | [79] |

| Vegetable oil |

PS |

91% in COD; 87% in TOC |

[80] |

| Urban | Zirconia (ZrO2) and Al2O3 | 97% of COD | [81] |

| Anaerobically digested sludge | PES | (66% COD removal | [82] |

| Raw sewage ween | PVDF | 138±26mg/L of COD | [83] |

| Primary clarifier effluent | PVDF | 78±30 mg/L of COD | [83] |

| Urban | Polyolephine | 43mg O2/L 0f COD and 17mg O2/L of BOD5 | [84] |

2.3. Removal Efficiency of Phosphorus Compounds from Liquid Waste by Using MF Membrane

2.4. Removal Efficiency of Phosphorus Compounds from Liquid Waste by Using UF Membrane

2.5. Separation Efficiency of Nitrogen Compounds from Liquid Waste by Using MF Membrane

2.6. Separation Efficiency of Nitrogen Compounds from Liquid Waste by Using UF Membrane

3. Comparison

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| % | Percentage |

| µm | Micrometer |

| BOD5 | Biochemical Oxygen Demand, 5 days |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| Da | Daltons |

| DOC | Dissolved Organic Carbon |

| h | Hour |

| kDa | KiloDaltons |

| kPa | Kilopascal |

| LMH | Liters per square meter per hour |

| m/s | Meter per second |

| m | Meter |

| m2 | Square meter |

| MF | Microfiltration |

| mg/L | Milligram per Liter |

| min | Minute |

| MWCO | Molecular weight cut-offs |

| NH₄⁺ | Nitrogen Ammonia |

| nm | Nanometer |

| NO-2 | Nitrites |

| NO₃⁻ | Nitrates |

| OC | Organic Carbon |

| Pa | Pascal |

| PAC | Powdered activated carbon , |

| PN | Particulate Nitrogen |

| PO₄³⁻ | Phosphates |

| POC | Particulate Organic Carbon |

| PP | Particulate Phosphorus |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene Fluoride , |

| SS | Suspended Solids |

| TCOD | Total Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| TKN | Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen |

| TMP | Transmembrane Pressure |

| TN | Total Nitrogen |

| TOC | Total Organic Carbon |

| TP | Total Phosphorous |

| TSS | Total Suspended Solids |

| UF | Ultrafiltration |

References

- Kato, S.; Kansha Y. Comprehensive review of industrial wastewater treatment techniques. Springer Berlin Heidelberg 2024, 31, 39. [CrossRef]

- Sha, C.; Shen,S.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, C.; Lu,X.; Zhang, H. A Review of Strategies and Technologies for Sustainable. water 2024, 16, 3003. [CrossRef]

- Shamshad, J.; Rehman, R.U. Advances Environmental Science Innovative approaches to sustainable wastewater treatment : a comprehensive exploration of conventional and emerging technologies. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2025, 4, 189. [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Talbott, J.; Jones, T.; Ward, B. B. Variable contribution of wastewater treatment plant effluents to downstream nitrous oxide concentrations and emissions. Biogeosciences 2024, 21, 3239–3250. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Li, H.; Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Lu, L. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology Quantifying greenhouse gas emissions from wastewater treatment plants : A critical review. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnology 2025, 27, 2666-4984. [CrossRef]

- Smol,M. Circular Economy in Wastewater Treatment Plant—Water, Energy and Raw Materials Recovery. energies 2023, 16, 3911. [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Li, J.; Liu, R.; Van Loosdrecht, M. C. M. Resource Recovery from Wastewater: What, Why, and Where? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 14065–14067. [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, U.; Sarpong, G.; Gude, V. G. Transitioning Wastewater Treatment Plants toward Circular Economy and Energy Sustainability. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 11794−11803. [CrossRef]

- Sravan, J. S.; Matsakas, L. Advances in Biological Wastewater Treatment Processes : Focus on Low-Carbon Energy and Resource Recovery in Biorefinery Context. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 281. [CrossRef]

- Ezugbe, E. O.; Rathilal, S. Membrane technologies in wastewater treatment: A review. Membranes (Basel) 2020, 10, 5. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Monnot, M.; Ercolei, L.; Moulin, P. Membrane-Based Processes Used in Municipal Wastewater Treatment for Water Reuse : State-Of-The-Art and Performance Analysis. Membranes (Basel) 2020, 10, 131. [CrossRef]

- Aydin, D. Recent advances and applications of nanostructured membranes in water purification. Turkish J. Chem. 2024, 48, 1. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S. A comprehensive review of membrane-based water filtration techniques. Appl. Water Sci. 2024, 14, 8, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Bray,R. T.; Jankowska,K.; Kulbat, E.; Łuczkiewicz, A.; Sokołowska, A. Ultrafiltration process in disinfection and advanced treatment of tertiary treated wastewater. Membranes (Basel) 2021, 11, 3. [CrossRef]

- Kyllönen, H.; Heikkinen, J.; Järvelä, E.; Sorsamäki, L.; Siipola, V.; Grönroos, A. Wastewater Purification with Nutrient and Carbon Recovery in a Mobile Resource Container. Membranes 2021, 11, 975. [CrossRef]

- Fatima, F.; Fatima, S.; Du, H.; Kommalapati, R.R. An Evaluation of Microfiltration and Ultrafiltration Pretreatment on the Performance of Reverse Osmosis for Recycling Poultry Slaughterhouse Wastewater. Separations 2024, 11, 115. [CrossRef]

- Elma, M.; Pratiwi, A.E.; Rahma, A.; Rampun, E.L.A.; Mahmud, M.; Abdi, C.; Rosadi, R.; Yanto, D.H.Y.; Bilad, M.R. Combination of Coagulation, Adsorption, and Ultrafiltration Processes for Organic Matter Removal from Peat Water. Sustainability 2022, 14, 370. [CrossRef]

- Akinnawo, S. O. Eutrophication: Causes, consequences, physical, chemical and biological techniques for mitigation strategies. Environ. Challenges 2023, 12, 2667-0100. [CrossRef]

- Deemter, D.; Oller, I.; Amat, A. M.; Malato, S. Advances in membrane separation of urban wastewater effluents for (pre)concentration of microcontaminants and nutrient recovery: A mini review. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2022, 11, 2666-8211. [CrossRef]

- Mehta,C. M.; Khunjar, W. O.; Nguyen, V.; Tait, S.; Batstone, D. J. Technologies to recover nutrients from waste streams: A critical review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 385–427. [CrossRef]

- Urošević, T.; Trivunac, K. Achievements in Low-Pressure Membrane Processes Microfiltration (MF) and Ultrafiltration (UF) for Wastewater and Water Treatment. In Current Trends and Future Developments on (Bio-) Membranes, 1st ed.; Basile, A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 35–70. [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, A.; Akhtar, A.; Subbiah, S. Microfiltration and Ultrafiltration Membrane Technologies. In Membrane Technologies for Biorefining; Subbiah, S., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 1–32. [CrossRef]

- Utoro, P.A.R.; Sukoyo, A.; Sandra, S.; Izza, N.; Dewi, S.R.; Wibisono, Y. High-Throughput Microfiltration Membranes with Natural Biofouling Reducer Agent for Food Processing. Processes 2019, 7, 1. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Ngo, H. H.; Li, J. A mini-review on membrane fouling. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 122, 27–34. [CrossRef]

- Peters, C. D.; Rantissi, Gitis, T. V.; Hankins, N. P. Retention of natural organic matter by ultrafiltration and the mitigation of membrane fouling through pre-treatment, membrane enhancement, and cleaning - A review. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 44. [CrossRef]

- Bodzek, M. Membrane separation techniques – removal of inorganic and organic admixtures and impurities from water environment – review. Arch. Environ. Prot. 2019, 45, 4–9. [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, C. O. C.; Veit, M. T.; Palácio,S. M.; Gonçalves, G. C.; Fagundes-Klen, M. R. Combined Application of Coagulation/Flocculation/Sedimentation and Membrane Separation for the Treatment of Laundry Wastewater. Int. J. Chem. Eng. 2019, 13. [CrossRef]

- Rautenbach, R.; Linn, T.; Eilers, L. Treatment of severely contaminated waste water by a combination of RO, high-pressure RO and NF - Potential and limits of the process. J. Memb. Sci. 2000, 174, 231–241. [CrossRef]

- Quist-Jensen, C. A.; Macedonio, F.; Drioli, E. Membrane technology for water production in agriculture: Desalination and wastewater reuse. Desalination 2015, 364, 17–32. [CrossRef]

- Kataki, S.; Rupam, P.; Soumya, C.; Mohan G.Sharma,V. ; Dwivedi, S. ; Kamboj,S. K. ;Dev V. Bioaerosolization and pathogen transmission in wastewater treatment plants: Microbial composition, emission rate, factors affecting and control measures. Chemosphere 2022, 287, 132180. [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Yang, F.; Li, X.; Liu, S. ; Lin, Y. ; Hu, E.; Gao, L. ; Li, M. Composition of dissolved organic matter (DOM) in wastewater treatment plants influent affects the efficiency of carbon and nitrogen removal. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159541. [CrossRef]

- Szymański, D.; Zielińska, M.; Dunalska, J. A. Microfiltration and ultrafiltration for treatment of lake water during algal blooms. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2019, 19, 351–358. [CrossRef]

- Velusamy, K.; Periyasamy, S.; Kumar, P.S.V; Vo D.V.N.; Sindhu, J.; Sneka, D.; Subhashini, B. Advanced techniques to remove phosphates and nitrates from waters: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 3165–3180. [CrossRef]

- Zacharof, M. P.; Lovitt, R. W. Complex effluent streams as a potential source of volatile fatty acids. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2013, 4, 557–581. [CrossRef]

- Vyas, H. K.; Bennett, R. J.; Marshall, A. D. Influence of operating conditions on membrane fouling in crossflow microfiltration of particulate suspensions. Int. Dairy J. 2000, 10, 477–487. [CrossRef]

- Nouri, E.; Breuillin-Sessoms, F.; Feller, U.; Reinhardt, D. Phosphorus and nitrogen regulate arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in petunia hybrida. PLoS One 2014, 9, 90841. [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, S. S.; Nosova, E. N.; Melnikova, E. D.; Zabolotsky, V. I. Reactive separation of inorganic and organic ions in electrodialysis with bilayer membranes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 268, 118561. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Han, D. W.; Kim, D. J. Selective release of phosphorus and nitrogen from waste activated sludge with combined thermal and alkali treatment. Bioresour. Technol., 2015, 190, 522–528. [CrossRef]

- Talens-Alesson, F. I. Behaviour of SDS micelles bound to mixtures of divalent and trivalent cations during ultrafiltration. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2007, 299, 169–179. [CrossRef]

- Modin, O.; Persson, F.; Wil, B. Nonoxidative removal of organics in the activated sludge process. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 46, 635–672. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, Y.; Torabian, A.; Mehrdadi, N.; Habibi-Rezaie, M.; Pezeshk, H.; Nabi-Bidhendi, G. R. Optimizing aeration rates for minimizing membrane fouling and its effect on sludge characteristics in a moving bed membrane bioreactor. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 186, 1097–1102. [CrossRef]

- Mansi, A. E.; El-Marsafy,S. M.; Elhenawy, Y.; Bassyouni, M. Assessing the potential and limitations of membrane-based technologies for the treatment of oilfield produced water. Alexandria Eng. J. 2023, 68, 787–815. [CrossRef]

- Kafle, S.R.; Adhikari, S.; Shrestha, R.; Ban, S.; Khatiwada, G.; Gaire, P.; Tuladhar, N.; Jiang, G.; Tiwari, A. Advancement of membrane separation technology for organic pollutant removal. Water Sci. Technol. 2024, 89, 2290–2310. [CrossRef]

- Zularisam, A.W.; Ismail, A.F.; Salim, R. Behaviours of natural organic matter in membrane filtration for surface water treatment—A review. Desalination 2006, 194, 211–231. [CrossRef]

- Alsoy Altinkaya, S. A Review on Microfiltration Membranes: Fabrication, Physical Morphology, and Fouling Characterization Techniques. Front. Membr. Sci. Technol. 2024, 3, 1426145. [CrossRef]

- Collivignarelli, M.C.; Abbà, A.; Carnevale Miino, M.; Damiani, S. Treatments for Color Removal from Wastewater: State of the Art. J. Environ. Manage. 2019, 236, 727–745. [CrossRef]

- Qasem, N.A.A.; Mohammed, R.H.; Lawal, D.U. Removal of Heavy Metal Ions from Wastewater: A Comprehensive and Critical Review. npj Clean Water 2021, 4, 36. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; Liu, H.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y. Enhanced Separation Performance of Microfiltration Carbon Membranes for Oily Wastewater Treatment by an Air Oxidation Strategy. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2021, 169, 108620. [CrossRef]

- Żyłła, R.; Foszpańczyk, M.; Kamińska, I.; Kudzin, M.; Balcerzak, J.; Ledakowicz, S. Impact of Polymer Membrane Properties on the Removal of Pharmaceuticals. Membranes 2022, 12, 150. [CrossRef]

- AlMarzooqi, F.A.; Bilad, M.R.; Arafat, H.A. Development of PVDF Membranes for Membrane Distillation via Vapour Induced Crystallisation. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 77, 164–173. [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yin, Q.; Cui, Z.; Li, W.; Xing, W. Fabrication and Characterization of Amphiphilic PVDF Copolymer Ultrafiltration Membrane with High Anti-Fouling Property. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 521, 95–103. [CrossRef]

- Anis, S.F.; Hashaikeh, R.; Hilal, N. Microfiltration Membrane Processes: A Review of Research Trends over the Past Decade. J. Water Process Eng. 2019, 32, 100941. [CrossRef]

- Othman, N.H.; Jaafar, J.; Ismail, A.F.; Othman, M.H.D.; Rahman, M.A.; Hasbullah, H.; Yusof, N.; Abdullah, N. A Review on the Use of Membrane Technology Systems in Developing Countries. Membranes 2022, 12, 30. [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Han, Y. An Effective Mercury Ion Adsorbent Based on a Mixed-Matrix Polyvinylidene Fluoride Membrane with Excellent Hydrophilicity and High Mechanical Strength. Processes 2024, 12, 30. [CrossRef]

- Leiknes, T.; Ødegaard, H.; Myklebust, H. Removal of Natural Organic Matter (NOM) in Drinking Water Treatment by Coagulation-Microfiltration Using Metal Membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2004, 242, 2, 47–55. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.Y.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, J.; Nam, J.W.; Kim, J.M.; Son, S. A Hybrid Microfiltration-Granular Activated Carbon System for Water Purification and Wastewater Reclamation/Reuse. Desalination 2009, 243, 3, 132–144. [CrossRef]

- Babaei, L.; Torabian, A.; Aminzadeh, B. Application of Microfiltration and Ultrafiltration for Reusing Treated Wastewater: A Solution to Ease Iran’s Water Shortage Problems. J. Adv. Chem. 2015, 11, 3662–3668. [CrossRef]

- Abadi, S.R.H.; Sebzari, M.R.; Hemati, M.; Rekabdar, F.; Mohammadi, T. Ceramic Membrane Performance in Microfiltration of Oily Wastewater. Desalination 2011, 265, 3, 222–228. [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.C.; Borges, R.M.H.; Oliveira Filho, A.M.; Nobrega, R.; Sant’Anna, G.L. Oilfield Wastewater Treatment by Combined Microfiltration and Biological Processes. Water Res. 2002, 36, 95–104. [CrossRef]

- Belgada, A.; Achiou, B.; Ouammou, M.; El Rhilassi, A.; Bennazha, J.; El Hafiane, Y. Optimization of Phosphate/Kaolinite Microfiltration Membrane Using Box–Behnken Design for Treatment of Industrial Wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 104972. [CrossRef]

- Hua, F.L.; Tsang, Y.F.; Wang, Y.J.; Chan, S.Y.; Chua, H.; Sin, S.N. Performance Study of Ceramic Microfiltration Membrane for Oily Wastewater Treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2007, 128, 169–175. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, K.H.; Song, K.G. Treatment of Domestic Wastewater Using Microfiltration for Reuse of Wastewater. Desalination 1999, 126, 7–14. [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Song, K.G.; Ahn, K.H. Contribution of microfiltration on phosphorus removal in the sequencing anoxic/anaerobic membrane bioreactor. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2009, 32, 593–602. [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, M.; Mozia, S. Removal of organic matter from water by PAC/UF system. Water Res. 2002, 36, 4137–4143. [CrossRef]

- Sutzkover-Gutman, I.; Hasson, D.; Semiat, R. Humic substances fouling in ultrafiltration processes. Desalination 2010, 261, 218–231. [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, C.; Wasyłeczko, M.; Lewińska, D.; Chwojnowski, A. A Comprehensive Review of Hollow-Fiber Membrane Fabrication Methods across Biomedical, Biotechnological, and Environmental Domains. Molecules 2024, 29, 2637. [CrossRef]

- Diallo, H.M.; Elazhar, F.; Elmidaoui, A.; Taky, M. Combination of ultrafiltration, activated carbon and disinfection as tertiary treatment of urban wastewater for reuse in agriculture. Desalin. Water Treat. 2024, 320, 100596. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Benítez, A.; Sanchís-Perucho, P.; Godifredo, J.; Serralta, J.; Barat, R.; Robles, R.; Seco, A. Ultrafiltration after primary settler to enhance organic carbon valorization: Energy, economic and environmental assessment. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 58, 104892. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, B.M.; Fuller, L.B.M.C.; Siegler, K.; Deng, X.; Tjeerdema, R.S. Treating Agricultural Runoff with a Mobile Carbon Filtration Unit. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2022, 82, 455–466. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.A. Wastewater Treatment and Reuse for Sustainable Water Resources Management: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10940. [CrossRef]

- Voulvoulis, N. Water Reuse from a Circular Economy Perspective and Potential Risks from an Unregulated Approach. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2018, 2, 32–45. [CrossRef]

- Salahi, A.; Mohammadi, T.; Mosayebi Behbahani, R.; Hemmati, M. Asymmetric Polyethersulfone Ultrafiltration Membranes for Oily Wastewater Treatment: Synthesis, Characterization, ANFIS Modeling, and Performance. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 170–178. [CrossRef]

- Chang, I.S.; Chung, C.M.; Han, S.H. Treatment of Oily Wastewater by Ultrafiltration and Ozone. Desalination 2001, 133, 225–232. [CrossRef]

- Căilean, D.; Barjoveanu, G.; Teodosiu, C.; Pintilie, L.; Dăscălescu, I.G.; Păduraru, C. Technical Performances of Ultrafiltration Applied to Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant Effluents. Desalin. Water Treat. 2015, 56, 1476–1488. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.S.; Yan, L.; Xiang, C.B.; Hong, L.J. Treatment of Oily Wastewater by Organic-Inorganic Composite Tubular Ultrafiltration (UF) Membranes. Desalination 2006, 196, 76–83. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, T.; Esmaeelifar, A. Wastewater Treatment Using Ultrafiltration at a Vegetable Oil Factory. Desalination 2004, 166, 329–337. [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Lin, Y.; Qu, H.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, X.; Tang, Y. Technical and Economic Evaluation of WWTP Renovation Based on Applying Ultrafiltration Membrane. Membranes 2020, 10, 180. [CrossRef]

- Fugère, R.; Mameri, N.; Gallot, J.E.; Comeau, Y. Treatment of Pig Farm Effluents by Ultrafiltration. J. Membr. Sci. 2005, 255, 225–231. [CrossRef]

- Salladini, A.; Prisciandaro, M.; Barba, D. Ultrafiltration of Biologically Treated Wastewater by Using Backflushing. Desalination 2007, 207, 24–34. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, T.; Esmaeelifar, A. Wastewater Treatment of a Vegetable Oil Factory by a Hybrid Ultrafiltration-Activated Carbon Process. J. Membr. Sci. 2005, 254, 129–137. [CrossRef]

- Xing, C.H.; Tardieu, E.; Qian, Y.; Wen, X.H. Ultrafiltration Membrane Bioreactor for Urban Wastewater Reclamation. J. Membr. Sci. 2000, 177, 73–82. [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes-Cabezas, M.; Pérez-Valiente, E.; Luján-Facundo, M.-J.; Bes-Piá, M.-A.; Álvarez-Blanco, S.; Mendoza-Roca, J.A. Ultrafiltration of Anaerobically Digested Sludge Centrate as Key Process for a Further Nitrogen Recovery Process. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 35, 103661. [CrossRef]

- Ravazzini, A.M.; van Nieuwenhuijzen, A.F.; van der Graaf, J.H.M.J. Direct Ultrafiltration of Municipal Wastewater: Comparison between Filtration of Raw Sewage and Primary Clarifier Effluent. Desalination 2005, 178 , 51–62. [CrossRef]

- Alonso, E.; Santos, A.; Solis, G.J.; Riesco, P. On the Feasibility of Urban Wastewater Tertiary Treatment by Membranes: A Comparative Assessment. Desalination 2001, 141, 39–51. [CrossRef]

- Bunce, J.T.; Ndam, E.; Ofiteru, I.D.; Moore, A.; Graham, D.W. A Review of Phosphorus Removal Technologies and Their Applicability to Small-Scale Domestic Wastewater Treatment Systems. Front. Environ. Sci. 2018, 6, 8. [CrossRef]

- Vu, M.T.; Liu, C.; Wei, Z.; Wang, Q.; Tran, H.T.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Zhang, X. Recent Technological Developments and Challenges for Phosphorus Removal and Recovery toward a Circular Economy. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 30, 103114. [CrossRef]

- Smol, M. The Use of Membrane Processes for the Removal of Phosphorus from Wastewater. Desalin. Water Treat. 2018, 128, 397–406. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, R.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, X. Recovery of Phosphorus from Wastewater: A Review Based on Current Phosphorus Removal Technologies. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 1148–1172. [CrossRef]

- El Batouti, M.; Alharby, N.F.; Elewa, M.M. Review of New Approaches for Fouling Mitigation in Membrane Separation Processes in Water Treatment Applications. Separations 2022, 9, 1. [CrossRef]

- Belgada, A.; Bouazizi, A.; Medjahed, S.; Bouzaza, A.; Achour, S.; Hamacha, R.; Drouiche, N.; Aoudj, S.; Ahmed, M. Low-Cost Ceramic Microfiltration Membrane Made from Natural Phosphate for Pretreatment of Raw Seawater for Desalination. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 1613–1621. [CrossRef]

- Zahed, M.A.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Nghiem, L.D.; Zhang, X.; Guo, J. Phosphorus Removal and Recovery: State of the Science and Challenges. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 58561–58589. [CrossRef]

- Battistoni, P.; De Angelis, A.; Pavan, P.; Prisciandaro, M.; Cecchi, F. Phosphorus Removal from a Real Anaerobic Supernatant by Struvite Crystallization. Water Res. 2001, 35, 2167–2178. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Chang, Q.; Liu, X.; Meng, G. Improvement of Crossflow Microfiltration Performances for Treatment of Phosphorus-Containing Wastewater. Desalination 2006, 194, 182–191. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, B. Removal of Phenol and Phosphoric Acid from Wastewater by Microfiltration Carbon Membranes. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2018, 205, 1432–1441. [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.C.; Liu, J.C. Removal of Phosphate and Fluoride from Wastewater by a Hybrid Precipitation-Microfiltration Process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2010, 74, 329–335. [CrossRef]

- Koh, K.Y.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J.P. Improvement of Ultrafiltration for Treatment of Phosphorus-Containing Water by a Lanthanum-Modified Aminated Polyacrylonitrile Membrane. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 7170–7181. [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.; Khosravanipour Mostafazadeh, A.; Drogui, P.; Tyagi, R.D. Removal of Organic Micro-Pollutants by Membrane Filtration. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 1st ed.; Pandey, A., Negi, S., Eds.; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 305–329. [CrossRef]

- Pervez, M.N.; Ahsan, M.A.; Nizami, A.S.; Rehan, M.; Lam, S.S.; Ma, Y.; Yang, Y. Factors Influencing Pressure-Driven Membrane-Assisted Volatile Fatty Acids Recovery and Purification—A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 817, 152993. [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Wang, Q.; Ma, H.; Ohsumi, Y.; Ogawa, H.I. Study on Phosphorus Removal Using a Coagulation System. Process Biochem. 2005, 40, 2623–2627. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Sui, Y.; Wang, X. Metal–Organic Framework-Based Ultrafiltration Membrane Separation with Capacitive-Type for Enhanced Phosphate Removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 371, 903–913. [CrossRef]

- Moazzem, S.; Wills, J.; Fan, L.; Roddick, F.; Jegatheesan, V. Performance of Ceramic Ultrafiltration and Reverse Osmosis Membranes in Treating Car Wash Wastewater for Reuse. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 8654–8668. [CrossRef]

- Moradihamedani, P.; Bin Abdullah, A. H. Phosphate Removal from Water by Polysulfone Ultrafiltration Membrane Using PVP as a Hydrophilic Modifier. Desalin. Water Treat. 2016, 57, 25542–25550. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S. M.; Ullman, J. L. Removal of Phosphorus, BOD, and Pharmaceuticals by Rapid Rate Sand Filtration and Ultrafiltration Systems. J. Environ. Eng. 2016, 142, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B. K.; Baek, K.; Yang, J. W. Simultaneous Removal of Nitrate and Phosphate Using Cross-Flow Micellar-Enhanced Ultrafiltration (MEUF). Water Sci. Technol. 2004, 50, 227–234. [CrossRef]

- Al-Juboori, R. A.; Al-Shaeli, M.; Al Aani, S.; Johnson, D.; Hilal, N. Membrane Technologies for Nitrogen Recovery from Waste Streams: Scientometrics and Technical Analysis. Membranes 2023, 13, 15. [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, C. F.; Cancino-Madariaga, B.; Torrejón, C.; Villegas, P. P. Separation of Nitrite and Nitrate from Water in Aquaculture by Nanofiltration Membrane. Desalin. Water Treat. 2016, 57, 26050–26062. [CrossRef]

- Masse, L.; Massé, D. I.; Pellerin, Y. The Use of Membranes for the Treatment of Manure: A Critical Literature Review. Biosyst. Eng. 2007, 98, 371–380. [CrossRef]

- Deemter, D.; Oller, I.; Amat, A. M.; Malato, S. Advances in Membrane Separation of Urban Wastewater Effluents for (Pre)Concentration of Microcontaminants and Nutrient Recovery: A Mini Review. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2022, 11, 100298. [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.; Nakhla, G.; Margaritis, A. Optimization of Biological Nutrient Removal in a Membrane Bioreactor System. J. Environ. Eng. 2005, 131 , 1021–1029. [CrossRef]

- Al Aani, S.; Mustafa, T. N.; Hilal, N. Ultrafiltration Membranes for Wastewater and Water Process Engineering: A Comprehensive Statistical Review over the Past Decade. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 35, 101241. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Performance of Hollow Fiber Ultrafiltration Membrane in a Full-Scale Drinking Water Treatment Plant in China: A Systematic Evaluation During 7-Year Operation. J. Memb. Sci. 2020, 613, 118469. [CrossRef]

- Fard, A. K.; Lau, W. J.; Matsuura, T.; Ismail, A. F.; Emadzadeh, D. Inorganic Membranes: Preparation and Application for Water Treatment and Desalination. Materials (Basel) 2018, 11, 1. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lueptow, R. M. Membrane Rejection of Nitrogen Compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001, 35 , 3008–3018. [CrossRef]

- Chon, K.; KyongShon, H.; Cho, J. Membrane Bioreactor and Nanofiltration Hybrid System for Reclamation of Municipal Wastewater: Removal of Nutrients, Organic Matter and Micropollutants. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 122, 181–188. [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Polonio, E.; Ortuño, J.F.; Borrás, L.; Seco, A.; Aguado, D. Removal of Nitrogen from the Liquid Fraction of Digestate by Membrane Technologies: A Review. Processes 2022, 10, 122. [CrossRef]

- Rizzioli, F.; Bertasini, D.; Bolzonella, D.; Frison, N.; Battista, F. A Critical Review on the Techno-Economic Feasibility of Nutrients Recovery from Anaerobic Digestate in the Agricultural Sector. Separation and Purification Technology, 2023, 306, 122690. [CrossRef]

- Molina, S.; Ocaña-Biedma, H.; Rodríguez-Sáez, L.; Landaburu-Aguirre, J. Experimental evaluation of the process performance of MF and UF membranes for the removal of nanoplastics. Membranes 2023, 13, 683. [CrossRef]

| Component | Nutrients | Nutrients form | Size(µm) | References |

| Organics | Organic Carbon | TOC | 1-100 μm | [40] |

| Inorganics | Nitrogen | TN | >0.5 nm |

[41] |

| Ammonium ion (NH₄⁺) | 0.1 to 0.5 nm | |||

| Nitrate (NO₃⁻) | 0.2 to 0.4 nm | |||

| Nitrite (NO₂⁻) | 0.2 to 0.4 nm | |||

| Phosphorus | TP | higher than 0.5nm | ||

| Phosphate (PO₄³⁻) | 0.5 nm in diameter |

| Wastewater | Membrane material | Removal rate | References |

| Secondary treated water | Polyolefin | 25–30% in DOC | [56] |

|

Olive oil mill |

Cell body and cell holder |

75.4% in TOC |

[57] |

|

Oil |

Ceramic membrane |

higher than 95% in TOC |

[58] |

|

Oilfield |

Mixed cellulose ester (MCE) |

82% in TOC |

[59] |

|

Industrial textile |

Phosphate/kaolinite |

69.39% in TOC |

[60] |

|

Oily |

Ceramic (Al2O3) |

96.6–97.7% in TOC |

[61] |

|

Domestic |

Membrane tank |

65,8% in TOC and 60% in DOC |

[62] |

| Reclamation/reuse | Polyolefin | 25–30%; 20–25% of COD | [56] |

| Reclamation/reuse | GAC | 53% of COD | [56] |

| Secondary effluent | PP fibers | 78% of COD | [57] |

| Activated sludge | Polyethersulfone(PS) | 96.3% of TCOD | [63] |

|

Poultry Slaughterhouse |

PVDF |

26.5% of COD |

[16] |

| Wastewater | Membrane material | Removal rate | References |

| Secondary treated water | Polyolefin | 5–8% of TP | [56] |

| Reclamation/reuse | Polyolefin | 5–8% of TP | [56] |

| Reclamation/reuse | GAC | 13% of TP | [56] |

| Sedimentation pond | PP fibers | 7% of TP | [57] |

| Activated sludge floc | PS | 82.6 % of TP and 70.8 % of PO₄³⁻ | [63] |

| From Automobile plant | Al2O3 ceramic | 99.7% of PO₄³⁻ | [93] |

| Phosphoric acid | Carbon | 55.3% in acid form | [94] |

| Liquid crystal display | MCE | 99% of PO₄³⁻ | [95] |

| Poultry Slaughterhouse | PVDF | 5.6% of TP | [16] |

| Urban wastewater tertiary | Propylene | 7,6mg/L in TP and 5,9mg/L of PO₄³⁻ | [84] |

| Wastewater | Membrane material | Removal rate | References |

| Car wash | Zirconia Oxide | Phosphorus (100%) with FeCl3 coagulant | [101] |

| Aqueous solution | Iron oxide/hydroxide | 93.6% of PO₄³⁻ | [102] |

| Municipal | Anthracite | >96% in TP | [103] |

| Poultry Slaughterhouse | PES | 16.7% in TP | [16] |

| Forms micelles | Acrylonitrile | > 91% of PO₄³⁻ | [104] |

| From the treatment plant | PVDF | 85% in TP | [77] |

| Pig manure | PVDF | Pt mg/L= 80 | [78] |

| Sieved and settled manure | PVDF | Pt mg/L= 150 | [78] |

| Sieved and biologically treated | PVDF | TP mg/L=30 | [78] |

| Biologically treated | Zirconium oxide | 25% of TP | [79] |

| Biologically treated | Zirconium oxide | 55% of Pt | [79] |

| Vegetable oil | PS | 85% of PO₄³⁻ | [76] |

| Municipal: raw sewage weens | PVDF | 4,4±0,6 mg/L in TP and 4±0,8 mg/L of PO₄³⁻ | [83] |

| Municipal: primary clarifier effluent | PVDF | 4,1±1 mg/L in TP and 3,4±1,6 mg/L of PO₄³⁻ | [83] |

| Urban | Polyolephine | 4 mg/L of PO₄³⁻ | [84] |

| Wastewater | Membrane material | Removal rate | References |

| Secondary treated | Polyolefin | 5–10% of TN | [56] |

| Reclamation/reuse | Polyolefin | 5–10% of TN | [56] |

| Secondary effluent discharged | PP fibers | 40 percent of TKN | [57] |

| Activated sludge floc | PS |

68.1 % of TN; 95.3 % in NH₄⁺ and 9.7% of NO₃⁻ | [63] |

| Urban | Propylene | 35mg/L of TN; 25 mg/L in NH₄⁺; 3,2 mg/L of NO₃⁻; 1,1mg/L of NO₂⁻ | [84] |

| Wastewater | Membrane material | Removal rate | References |

| Poultry Slaughterhouse | PVDF | 32.1% of TN | [16] |

| Forms micelles | Acrylonitrile | > 86% of NH₄⁺ | [104] |

| Influent from the treatment plant | PVDF | 98% of NH₄⁺ | [77] |

| Sieved and settled manure supernatant (SAS) | PVDF | TKN mg/L= 900 | [78] |

| Biologically treated | Zirconium oxide | 10% of TN | [79] |

| Biologically treated | Zirconium oxide | 26% of TN | [79] |

| Urban | ZrO2 and Al2O3 | 96.2% of (NH₄⁺) | [81] |

| Anaerobically digested sludge | PES and one PVDF | 13% of NH₄⁺ | [82] |

| Municipal: raw sewage ween | PVDF | 29±3mg/L in TN and 39,4±11,6mg/L of NH₄⁺ | [83] |

| Municipal : primary clarifier effluent | PVDF | 28,1±2,3 mg/L of TN | [83] |

| Urban tertiary | Polyolephine | 38 mg/L of TN; 19 mg/L in NH₄⁺; 12 mg/L of NO₃⁻ and 1,3mg/L of NH2- | [84] |

| Membrane | Target Compounds | Removal Efficiency (%) | Main Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

| MF | TOC, TSS, some TP | 60–75 | Sieving | Low cost, easy operation | Limited nutrient removal |

| UF | TOC, TP, TN | 75–99 | Sieving + adsorption | High selectivity | Fouling, costlier |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).