I. Introduction

Text classification has long been a core task in natural language processing, playing a fundamental role in information retrieval, public opinion monitoring, intelligent customer service, and knowledge management. With the explosive growth of online information, the scale of text data continues to expand and semantic structures are becoming increasingly complex. Traditional shallow feature engineering and single-level label prediction approaches can no longer meet the demands of multi-level and multi-dimensional applications. In high-value domains such as medical diagnosis [

1,

2,

3], financial risk management [

4,

5,

6,

7], backend cloud service [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], and e-commerce recommendation systems[

13,

14], category labels often follow a strict hierarchical organization. These hierarchies contain top-down semantic abstractions as well as cross-level dependencies and constraints. How to effectively leverage such structures to achieve efficient, accurate, and semantically consistent classification has become an important direction in intelligent text processing.

Hierarchical classification differs from flat classification. Its goal is not only to predict a single label but also to understand the tree or directed graph structure of a category system and make reasonable inferences across multiple levels of labels. The challenges mainly lie in two aspects. First, there are complex inheritance and constraint relationships between higher-level and lower-level labels, requiring models to capture both global semantic consistency and fine-grained local features. Second, the number of categories is large and their distribution is imbalanced[

15]. Higher-level labels often have sufficient samples, while lower-level labels are sparse. This imbalance can easily lead to bias in prediction. If traditional flat classification strategies are applied, it is difficult to ensure semantic consistency across levels while also achieving fine-grained and robust classification[

16].

Recent advances in deep learning, especially pre-trained language models, have created new opportunities for hierarchical classification. Models such as BERT, trained on large-scale corpora, can automatically learn context-sensitive semantic representations and significantly improve generalization across diverse tasks. Compared with bag-of-words or static word embeddings, pre-trained models better capture long-range dependencies, semantic ambiguities, and contextual dynamics. This provides a strong foundation for modeling hierarchical label systems. However, although BERT shows strong performance in single-label and multi-label classification, its potential in hierarchical classification has not been fully explored. Without explicitly modeling label hierarchies, models may learn fine-grained semantic features but ignore logical constraints between labels, resulting in predictions that are inconsistent with the hierarchical system.

Against this background, combining pre-trained language models with hierarchical classification mechanisms holds significant value. On one hand, hierarchical modeling can explicitly constrain the output space during prediction, preventing inconsistency between labels and improving interpretability[

17,

18,

19]. On the other hand, higher-level labels provide prior knowledge that can guide lower-level label prediction, alleviating problems of data sparsity and long-tail distribution. As application scenarios become more complex, text classification needs not only accuracy but also semantic completeness and hierarchical consistency. This further highlights the necessity of hierarchical methods. Research on BERT-based hierarchical classification is not only an extension of current classification techniques but also a key step toward improving the reliability and controllability of NLP systems in real-world applications[

20].

In summary, research on hierarchical classification algorithms based on BERT is both a response to the technological trends in natural language processing and a practical solution to the challenges of multi-level label systems. It can provide more refined and intelligent solutions for information filtering [

21,

22,

23], knowledge graph construction [

24,

25,

26], public opinion monitoring, and intelligent decision-making [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. From an academic perspective, this line of research expands the application boundary of pre-trained language models and advances hierarchical classification in both theory and practice. From an applied perspective, it improves the interpretability, stability, and usability of automated text processing systems, offering strong support for large-scale information management and intelligent services [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37].

III. Method

In hierarchical classification tasks, ensuring high-quality semantic modeling of the input text is essential for accurate multi-level predictions. To address this, the present study employs a Transformer-based encoder structure, which effectively captures the contextual dependencies within input sequences and produces robust, context-dependent vector representations. This approach specifically employs the time-aware and multi-source feature fusion techniques introduced by Wang [

43], enabling the model to aggregate semantic cues from diverse textual patterns and temporal signals. By employing this strategy, the encoder can dynamically adjust its attention mechanisms to highlight information relevant to hierarchical label structures. Further, the model incorporates the boundary-aware deep learning methodology proposed by An et al. [

44], who demonstrated that explicitly modeling boundaries between semantic units leads to finer-grained segmentation and improved contextual representation. This method is employed within the encoder to better distinguish hierarchical relationships and semantic nuances, which are critical for accurate category prediction across multiple levels.In addition, the internal knowledge adaptation and consistency-constrained dynamic routing mechanisms developed by Wu [

45] are employed to stabilize representation learning and promote semantic alignment within the encoder’s outputs. By integrating these consistency constraints, the model ensures that vector representations are not only context-sensitive but also structurally coherent across hierarchical label paths.

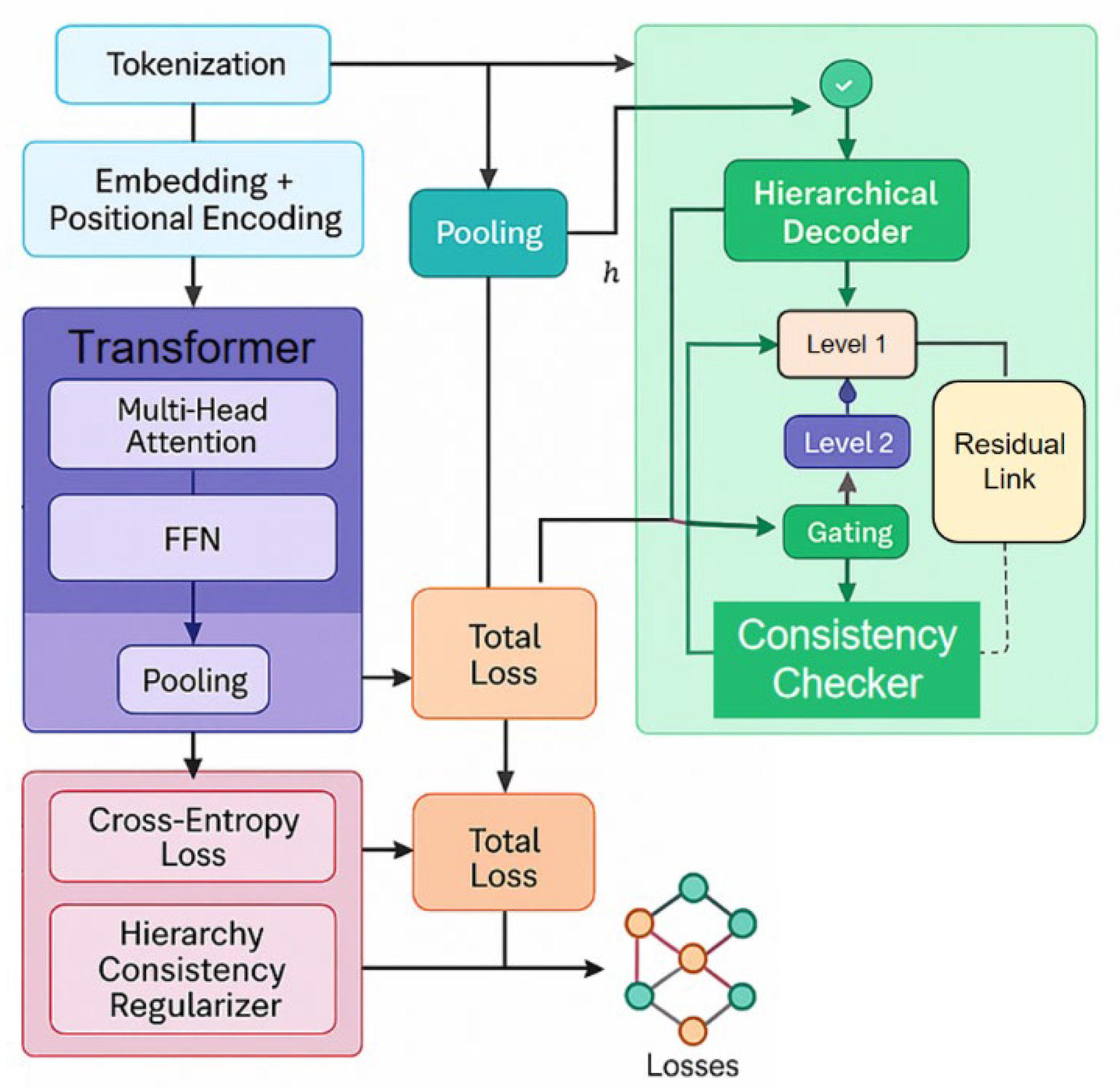

Collectively, the model architecture, as depicted in

Figure 1, employs these advanced methodologies to achieve robust and hierarchical semantic modeling, providing a strong foundation for subsequent stages of hierarchical text classification:

Given an input text consisting of a word sequence, it first passes through the embedding layer and position encoding to obtain the input matrix

, where n represents the sequence length and d represents the embedding dimension. Then, the multi-head self-attention mechanism is used to calculate the dependency between each position in the sequence to obtain the representation matrix:

Among them,

is the context representation after deep encoding. To obtain a global representation at the sentence level, we introduce a pooling operation on this basis:

Where is the semantic vector of the input text.

During the label prediction phase, traditional flat classification approaches typically employ a single softmax layer to output category probabilities. However, in hierarchical classification tasks, the model must explicitly account for the structural relationships among categories to maintain consistency across different levels. To address this, the proposed framework employs a hierarchical prediction strategy that goes beyond standard softmax-based classification. Specifically, the model incorporates the advanced label dependency modeling techniques employed by Wang et al. [

46], who demonstrated that pre-trained language models can be leveraged, even in few-shot learning scenarios, to extract fine-grained and structurally coherent entities within complex label systems. This methodology is employed here to strengthen the connection between semantic representation and label hierarchies. Moreover, the model architecture adopts the layer-wise structural mapping approach introduced by Quan [

47], which is employed to facilitate efficient information transfer and alignment between adjacent hierarchical levels. This enables the network to propagate global and local label dependencies throughout the prediction process, enhancing both precision and consistency. To further improve adaptability and model expressiveness, the framework employs the selective knowledge injection method via adapter modules, as described by Zheng et al. [

48]. By employing this technique, the system can dynamically inject relevant external knowledge into different hierarchical layers, tailoring the model’s decision-making to the multi-level category structure. Additionally, the model leverages the multiscale temporal modeling strategy proposed by Lian et al. [

49], which is employed to capture hierarchical dependencies and category dynamics over various granularities. This multiscale approach supports the hierarchical prediction process by accommodating both broad and fine-grained patterns present in cloud service anomaly detection, and its principles are adapted here for robust hierarchical text classification. By systematically employing these advanced methodologies, the prediction phase effectively models label hierarchies, ensuring that predictions across all levels are structurally consistent and semantically meaningful. Assume that the category system forms a tree, the hierarchical label set is denoted as

, and each label corresponds to an embedding vector

. We calculate the matching score between the text representation and the label representation using the inner product:

And the predicted probability is obtained through the hierarchical constrained softmax:

Where

represents the candidate set that belongs to the same level as the label

. This not only ensures the normalization between labels at the same level, but also preserves the consistency of the hierarchical structure. To further strengthen the model’s capacity for capturing and preserving hierarchical relationships, a structure-aware regularization term is added to the overall loss function. The total loss consists of two components: the standard cross-entropy loss, which evaluates prediction accuracy at each hierarchy level, and a hierarchical consistency constraint that promotes semantic alignment between parent and child categories. This additional term ensures that predictions are logically consistent with the multi-level structure of the label hierarchy.In formulating this structure-aware regularization, several advanced strategies from recent research are employed. The model integrates knowledge graph-infused fine-tuning [

50], which allows for the incorporation of external structured knowledge into the learning process, strengthening the reasoning abilities required for complex label hierarchies. In addition, multi-scale attention and sequence mining techniques are adopted [

51], enabling the model to capture both global patterns and fine-grained relationships within the text and across hierarchical levels. This ensures that contextual dependencies are effectively represented and leveraged when enforcing consistency constraints. To address the stability and contextual richness of the learned representations, structured memory mechanisms are further employed [

52]. These techniques help maintain stable semantic representations as information flows through the network, reducing the risk of semantic drift or inconsistency in deep hierarchical models. Moreover, hierarchical semantic-structural encoding is utilized [

53], providing an explicit framework for encoding hierarchical dependencies and ensuring that each level’s predictions remain compatible with both the semantic and logical requirements of the classification hierarchy. By synthesizing these approaches within the loss function, the proposed method systematically reinforces both the accuracy and the structural integrity of hierarchical predictions. This structure-aware regularization not only improves model robustness but also supports interpretable and reliable classification results under complex, multi-level label systems. The overall loss function can be expressed as:

Where represents the set of parent-child relationship edges in the label hierarchy graph, and is the trade-off coefficient. This regularization term forces the vector representations of parent and child categories to remain close during training, thereby improving the consistency and stability of the model in hierarchical predictions.

During the inference phase, it is essential that predictions strictly comply with the hierarchical constraints defined by the label system. To achieve this, a layer-by-layer decoding strategy is employed: at each level, the model selects the most probable label based on current context and then recursively advances into the subclass space of the subsequent layer. This top-down decoding mechanism ensures that each prediction is both contextually relevant and structurally consistent with the overall label hierarchy. The effectiveness of this approach is enhanced by leveraging several advanced methodologies. Dual-phase learning for unsupervised temporal encoding [

54] is utilized to provide stable and temporally coherent representations during inference, supporting reliable decision-making at each hierarchical level. In addition, principles from scalable multi-party collaborative data mining [

55] are incorporated to ensure that the decoding process remains robust, even when facing distributed or heterogeneous data sources commonly encountered in large-scale classification tasks.

Furthermore, interpretability and consistency are reinforced by integrating semantic and structural analysis techniques [

56], which allow the model to identify and account for implicit biases that may arise during hierarchical label selection. To optimize inference efficiency without sacrificing structural integrity, sensitivity-aware pruning mechanisms [

57] are also adopted, enabling the structured compression of the model and maintaining high accuracy in the selection of optimal labels at each layer. By employing this combination of strategies, the inference phase not only adheres to the constraints of hierarchical classification but also delivers robust, interpretable, and computationally efficient predictions across all levels of the label system. Specifically, assuming the label selected at layer

is

, the candidate label set at the next layer is its child node

. The final prediction path can be expressed as:

Where A represents the hierarchical depth, and B is the complete label path from the root node to the leaf node. This method ensures the rationality of the prediction while also enabling the model to take into account both global structural information and local fine classification requirements.

IV. Performance Evaluation

A. Dataset

The dataset used in this study comes from the Hierarchical Text Classification task on the Kaggle platform. It was specifically constructed to support research on text classification under multi-level label systems. The texts are mainly user-generated comments or short messages, covering multiple thematic domains. The labels are organized in a three-level structure. At the top level, there are six broad categories. Each top-level category is further divided into several subcategories, and some of these subcategories contain even more fine-grained third-level labels, forming a complete hierarchical label system.

The key characteristic of this dataset is its rigorous hierarchical organization and diverse category distribution. Models are required to accurately identify the semantic topics of texts while ensuring consistency across multiple levels of labels. This hierarchical labeling scheme closely resembles real-world application scenarios, such as product categorization, news topic organization, and online content management, where parent and child category relationships are naturally present. Compared to traditional flat classification tasks, this dataset presents a more challenging benchmark and provides an ideal setting for evaluating the effectiveness of hierarchical modeling methods.

In addition, the dataset is of moderate size, with diverse text corpora that exhibit noticeable noise. This makes it suitable for evaluating models under conditions of complex semantics, class imbalance, and label dependencies. By using this dataset, researchers can explore the strengths and limitations of hierarchical classification methods in semantic modeling, label consistency, and long-tail category prediction. Such analysis helps advance the development and application of hierarchical text classification algorithms.

B. Experimental Results

This paper first conducts a comparative experiment, and the experimental results are shown in

Table 1.

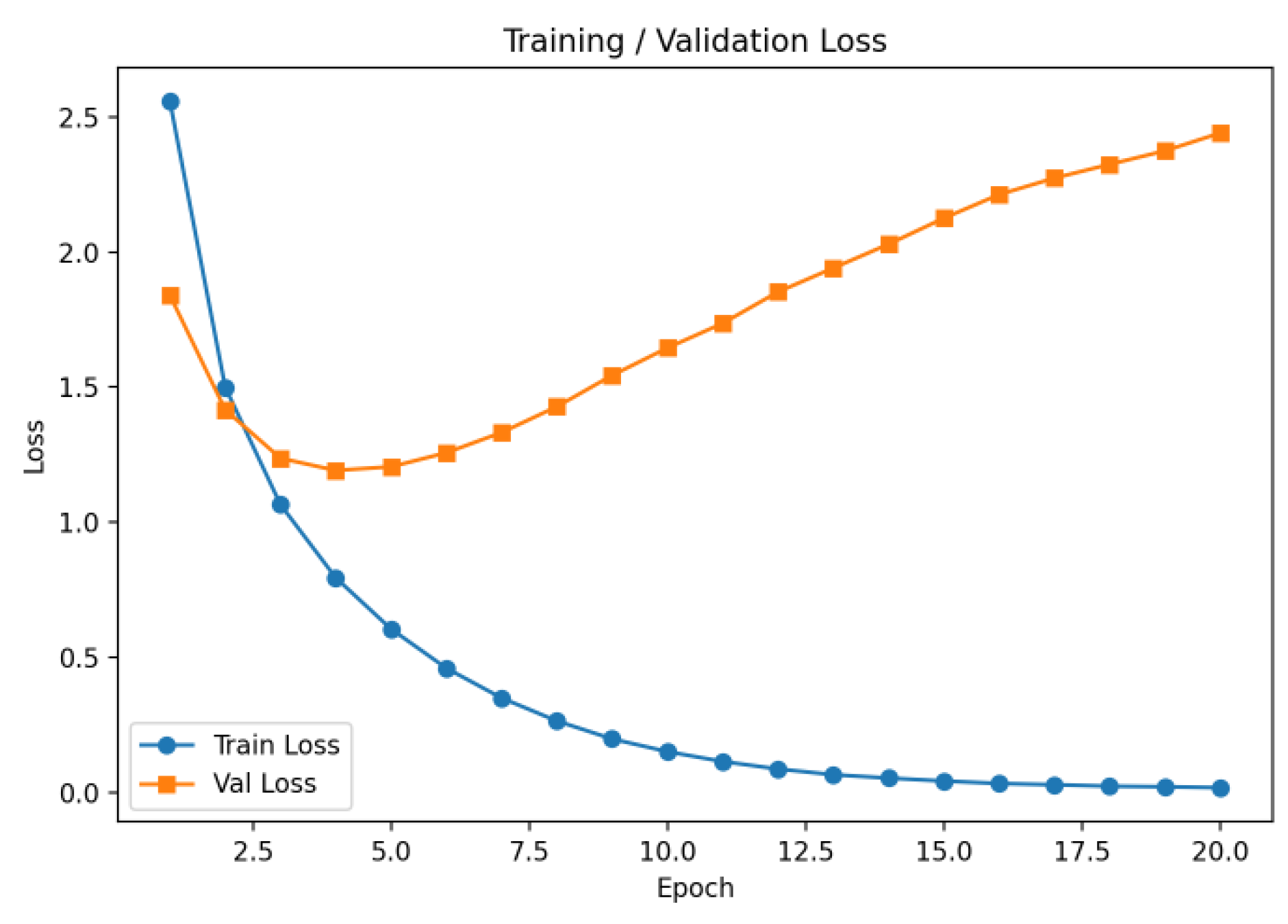

The results show that model performance on three-level classification improves with representational capacity. MLP performs the worst, with L3 accuracy below 0.41, while LSTM offers modest gains but struggles with long dependencies. Transformer further improves accuracy through global attention but lacks hierarchical constraints, causing inconsistency at deeper levels. BERT performs better overall (0.9033 at L1, 0.7133 at L2) but remains limited at L3 (0.5082). The proposed method achieves the best results (0.9194 at L1, 0.5311 at L3, average F1 of 0.7257) by introducing hierarchical modeling and consistency constraints. Training dynamics, illustrated in

Figure 2, further confirm stable optimization and reliable convergence.

From the figure, it can be seen that the training loss decreases rapidly during the first few epochs and then remains at a low level in later stages. This indicates that the model effectively captures semantic information in the text and quickly builds a stable feature representation ability. The trend demonstrates strong learning efficiency, as the model converges to the input space within a short time.

The validation loss also shows a clear decline at the early stage of training. This reflects the adaptability of the model to different data and suggests that the learned representations are not limited to the training set but have generalization ability. As training progresses, the model maintains a relatively stable performance on the validation set, confirming the robustness of the hierarchical classification method in practical tasks.

For hierarchical classification tasks, the downward trend of validation loss shows that the model can effectively use the relationships between hierarchical labels to enhance classification performance. The semantic consistency across different levels allows the model to correctly identify higher-level categories while also achieving strong performance in fine-grained category prediction. This demonstrates that modeling with hierarchical constraints provides significant advantages in improving semantic integrity.

Overall, the experimental results clearly show the effectiveness of the model in hierarchical text classification. The curves of both training and validation loss confirm the advantages of the method in learning semantic features, maintaining hierarchical consistency, and achieving stable predictions. This highlights the importance of hierarchical classification strategies in improving model performance for complex tasks.

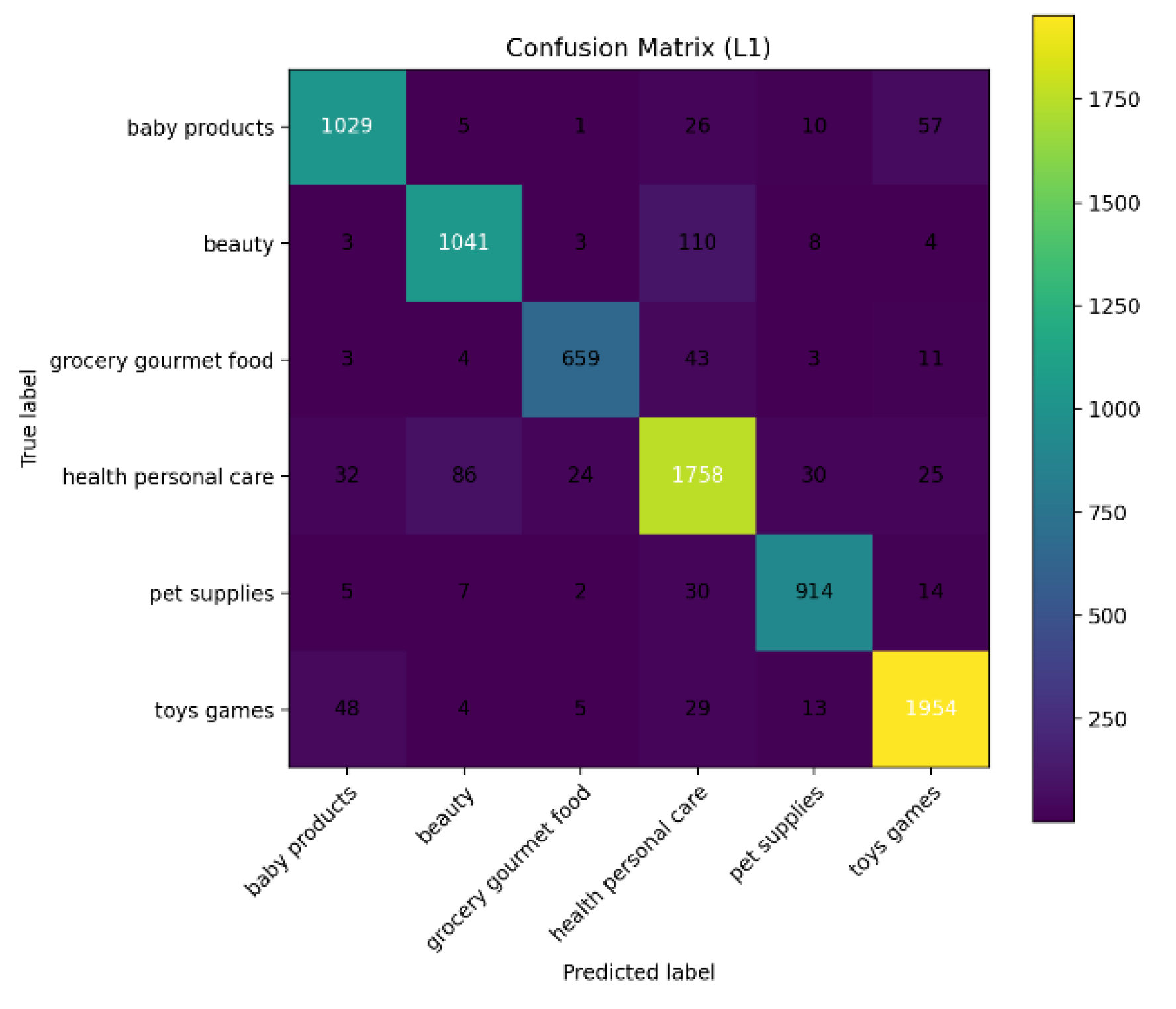

This paper also gives a schematic diagram of the confusion matrix at the L1 level, as shown in

Figure 3.

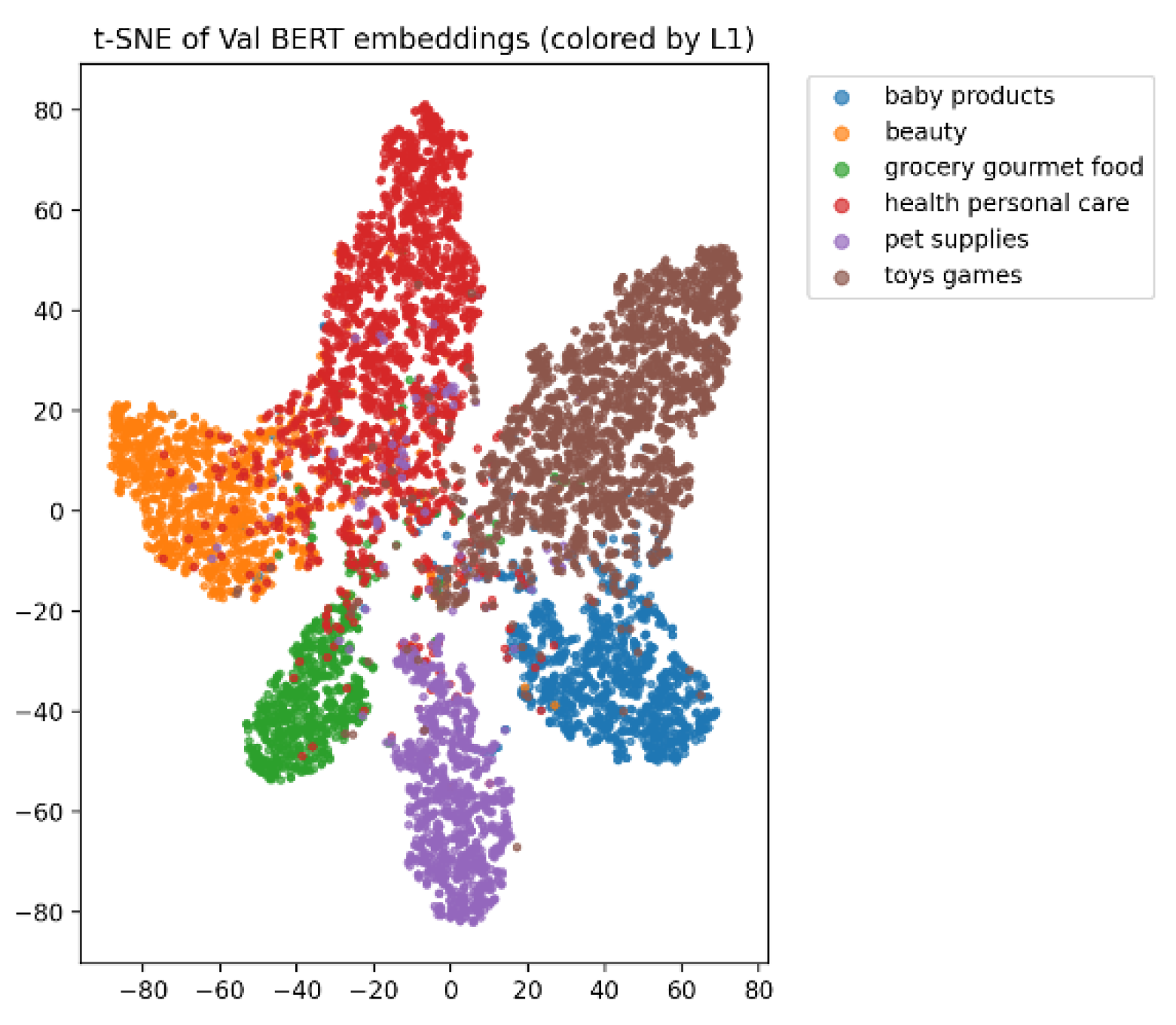

The confusion matrix demonstrates that the model achieves high accuracy in first-level category classification, with diagonal values consistently dominating non-diagonal entries, particularly in domains such as baby products, beauty, toy games, and health and personal care, where nearly 1,800 samples are correctly identified. These results indicate strong discriminative capacity in categories characterized by abundant samples and distinctive semantic features, while stable recognition performance is also observed in low-frequency categories such as grocery, gourmet food, and pet supplies. The incorporation of hierarchical label structures enhances semantic consistency across categories, ensuring robust performance in both coarse- and fine-grained classification tasks, a conclusion further corroborated by the t-SNE visualization in

Figure 4.

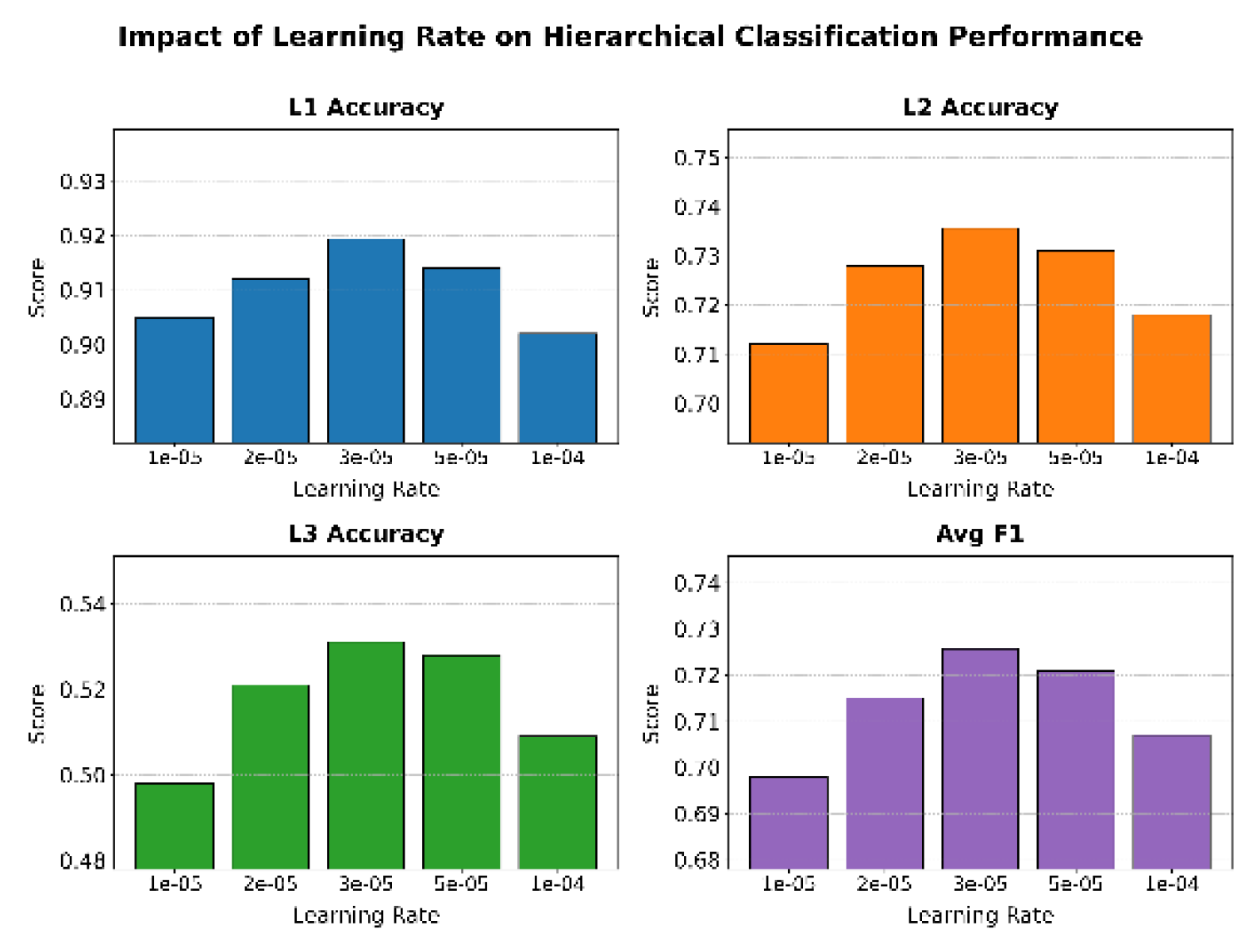

The t-SNE visualization demonstrates that the model achieves clear semantic clustering for first-level categories, with sample points forming compact, well-separated clusters that indicate strong discriminative capacity in the encoding process. Categories such as baby products, beauty, and toy games show the most compact structures, with toy games forming a particularly distinct and well-separated cluster, reflecting the model’s advantage in high-sample domains. Even in low-frequency categories such as grocery, gourmet food, and pet supplies, the model preserves independent clustering regions, illustrating the robustness of hierarchical semantic modeling in handling long-tail recognition under imbalanced data. Overall, the visualization confirms that the BERT-based hierarchical method maintains both inter-class separability and intra-class compactness, thereby providing a reliable foundation for stable prediction in complex classification tasks. Furthermore, the analysis of learning rate effects, as presented in

Figure 5, highlights its critical role in convergence speed, optimization stability, and the preservation of hierarchical semantic dependencies, with empirical results showing that appropriate configurations enable more effective representation learning while avoiding instability or failure during training.

The results of the average F1 score provide even clearer evidence of this pattern. At the learning rate of 3e−5, the average F1 score reaches the highest value, demonstrating the model’s ability to balance consistency across levels with fine-grained classification. This means that by selecting a proper learning rate, the model can not only improve overall accuracy but also enhance recognition of fine-grained categories while maintaining hierarchical consistency.

When the learning rate is further increased to 1e−4, the metrics show a decline. This suggests that an excessively large learning rate affects the stable update of parameters and weakens semantic modeling. In summary, the experiment verifies that learning rate, as a key hyperparameter, plays a decisive role in hierarchical text classification performance. Properly setting the learning rate maximizes the advantages of the BERT-based hierarchical classification method.

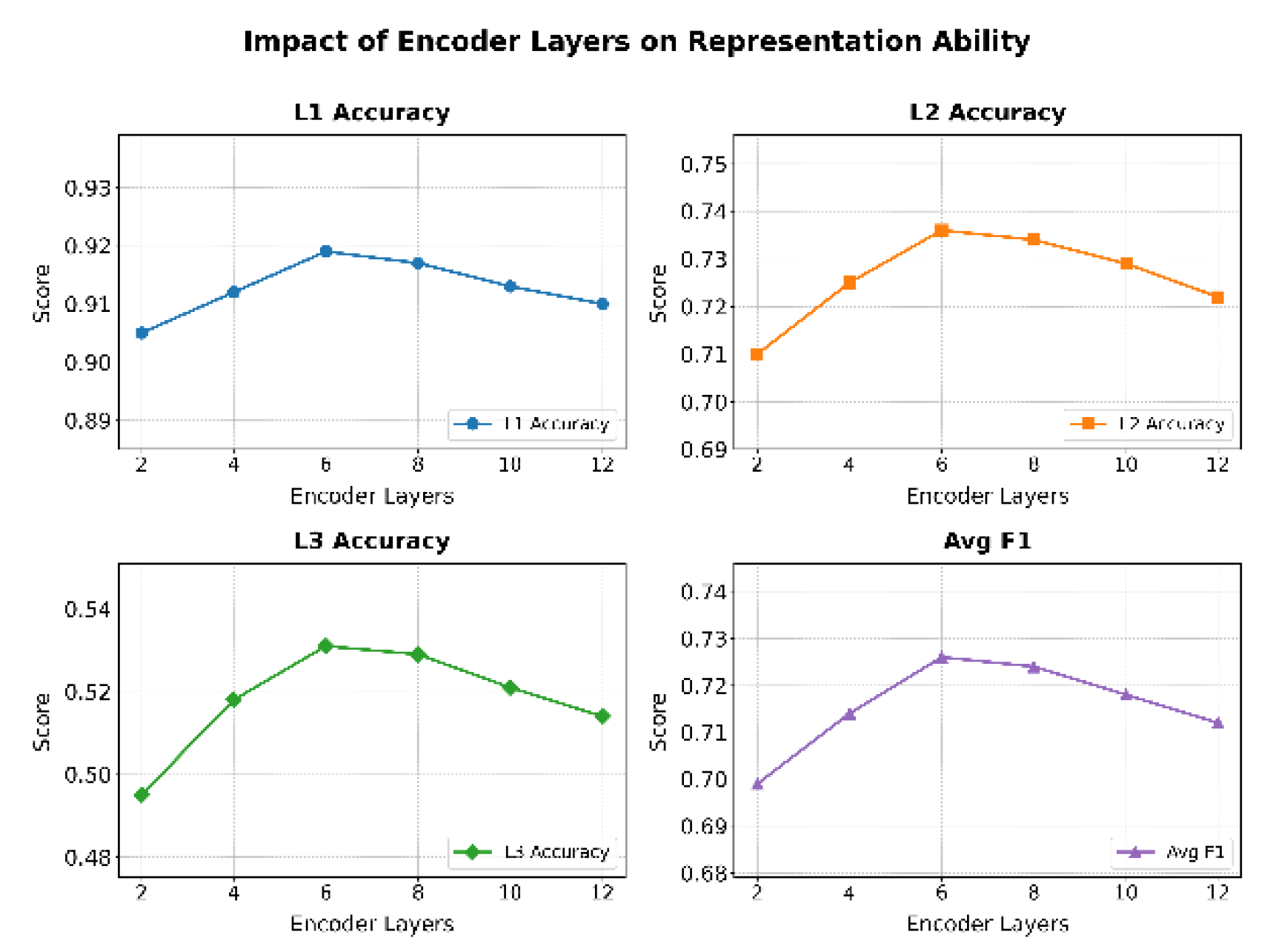

This paper also gives the impact of the number of encoding layers on representation ability, and the experimental results are shown in

Figure 6.

For the first-level and second-level accuracy, the highest performance is achieved at 6 layers, reaching about 0.919 and 0.736, respectively. This suggests that an appropriate increase in encoder depth helps the model better capture the semantic features of higher-level labels and improves discriminative ability in middle-level label recognition. The results at this stage reflect the advantage of deeper networks in handling complex semantic relations. In hierarchical systems, semantic consistency can be maintained more effectively.

For the third-level accuracy and the average F1 score, a similar trend of “rising first and then declining” is observed as depth increases. At 6 layers, the model achieves the best performance, with third-level accuracy exceeding 0.53 and average F1 reaching 0.726. This shows that under an optimal configuration of depth, the model balances inter-class separability and intra-class compactness, leading to overall stable classification and reliable fine-grained prediction.

When the encoder depth further increases to 10 and 12 layers, the metrics begin to decline. This suggests that although deeper networks increase model capacity, they may also introduce parameter redundancy and overfitting, which weakens the effectiveness of representation. Overall, the experiment confirms that in hierarchical text classification tasks, properly controlling the number of encoder layers is crucial for enhancing semantic modeling ability and maintaining hierarchical consistency.

V. Conclusion

This study conducts a systematic analysis and empirical investigation of a BERT-based hierarchical classification method. By combining semantic representation with hierarchical constraints, the proposed model demonstrates strong stability and effectiveness across classification tasks at different levels. The experimental findings show that the method captures both global and local semantic information within multi-level label spaces, achieving significant improvements in first-level, second-level, and third-level accuracy as well as overall F1 score. These results not only confirm the potential of pre-trained language models in hierarchical text classification but also provide solid support for improving existing classification systems.

From a methodological perspective, this work integrates deep semantic modeling with hierarchical consistency regularization, addressing the limitations of traditional flat classification that overlook hierarchical label relations. The model maintains semantic integrity while alleviating the challenges posed by class imbalance and sparse lower-level labels, ensuring strong robustness even in long-tail categories and complex semantic scenarios. This approach offers a feasible solution for classification under multi-level label systems and lays a solid foundation for the design and optimization of future related tasks.

From the perspective of experimental analysis, the proposed model exhibits good adaptability under key hyperparameters such as learning rate and encoder depth. This further demonstrates its stability and applicability under different conditions. Consistent advantages are observed across accuracy, F1 score, t-SNE visualization, and confusion matrix analysis, confirming the strength of the method in both representation learning and hierarchical modeling. Such consistency across multiple evaluation dimensions provides important empirical support for the reliability and generalizability of the model.

Overall, this research contributes not only to the theoretical and methodological development of hierarchical text classification but also holds practical significance in multiple application domains. Tasks such as legal document classification, medical text processing, e-commerce product management, news topic recognition, and intelligent question answering can all benefit from the proposed hierarchical classification method. By improving fine-grained categorization and hierarchical consistency, these applications can achieve higher accuracy and better interpretability in large-scale information processing, thereby offering a stronger technical foundation for intelligent information services and knowledge management.