Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Overview of Text Categorization (TC) and Recent Research

| Publication Type |

Title | Year | Authors | Objectives | Insights | Practical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Journal Article | Research on Intelligent Natural Language Texts Classification | 2022 | [11] | - Summarize and compare text classification methods. - Explore development direction of text classification research. |

The paper summarizes previous studies on text classification, highlighting the rapid development of machine learning technologies and the diversification of research methods. It compares classification methods based on technical routes, text vectorization, and classification information processing for further research insights. | - Intelligent classification enhances efficient use of natural language texts. - Provides references for further research in text classification methods. |

| Journal Article | The Research Trends of Text Classification Studies (2000–2020): A Bibliometric Analysis | 2022 | [12] | - Evaluate the state of the arts of TC studies. - Identify publication trends and important contributors in TC research. |

The study analyzes 3,121 text classification publications from 2000 to 2020, highlighting trends, contributors, and disciplines. It reveals increased interest in advanced classification algorithms, performance evaluation methods, and practical applications, indicating a growing interdisciplinary focus in text classification research. | - Recognizes recent trends in text classification research. - Highlights importance of advanced algorithms and applications. |

| Journal Article | A survey on text classification and its applications | 2020 | Xujuan et. Al [13] | - Overview of existing text classification technologies. - Propose research direction for text mining challenges. |

Previous studies on text classification have proposed various feature selection methods and classification algorithms, addressing challenges such as scalability due to the massive increase in text data. These studies highlight the importance of effective information organization and management in diverse research fields. | - Important applications in real-world text classification. - Addresses challenges in text mining and scalability. |

| Journal Article | A Survey on Text Classification: From Traditional to Deep Learning | 2022 | [14] | - Review state-of-the-art approaches from 1961 to 2021. - Create a taxonomy for text classification methods. |

The paper reviews state-of-the-art approaches in text classification from 1961 to 2021, highlighting traditional models and deep learning advancements. It discusses technical developments, benchmark datasets, and provides a comprehensive comparison of various techniques and evaluation metrics used in previous studies. | - Summarizes key implications for text classification research. - Identifies future research directions and challenges. |

| Book Chapter | Case Studies of Several Popular Text Classification Methods | 2023 | [15] | - Evaluate automatic language processing techniques for text classification. - Analyze and compare performance of various text classification algorithms. |

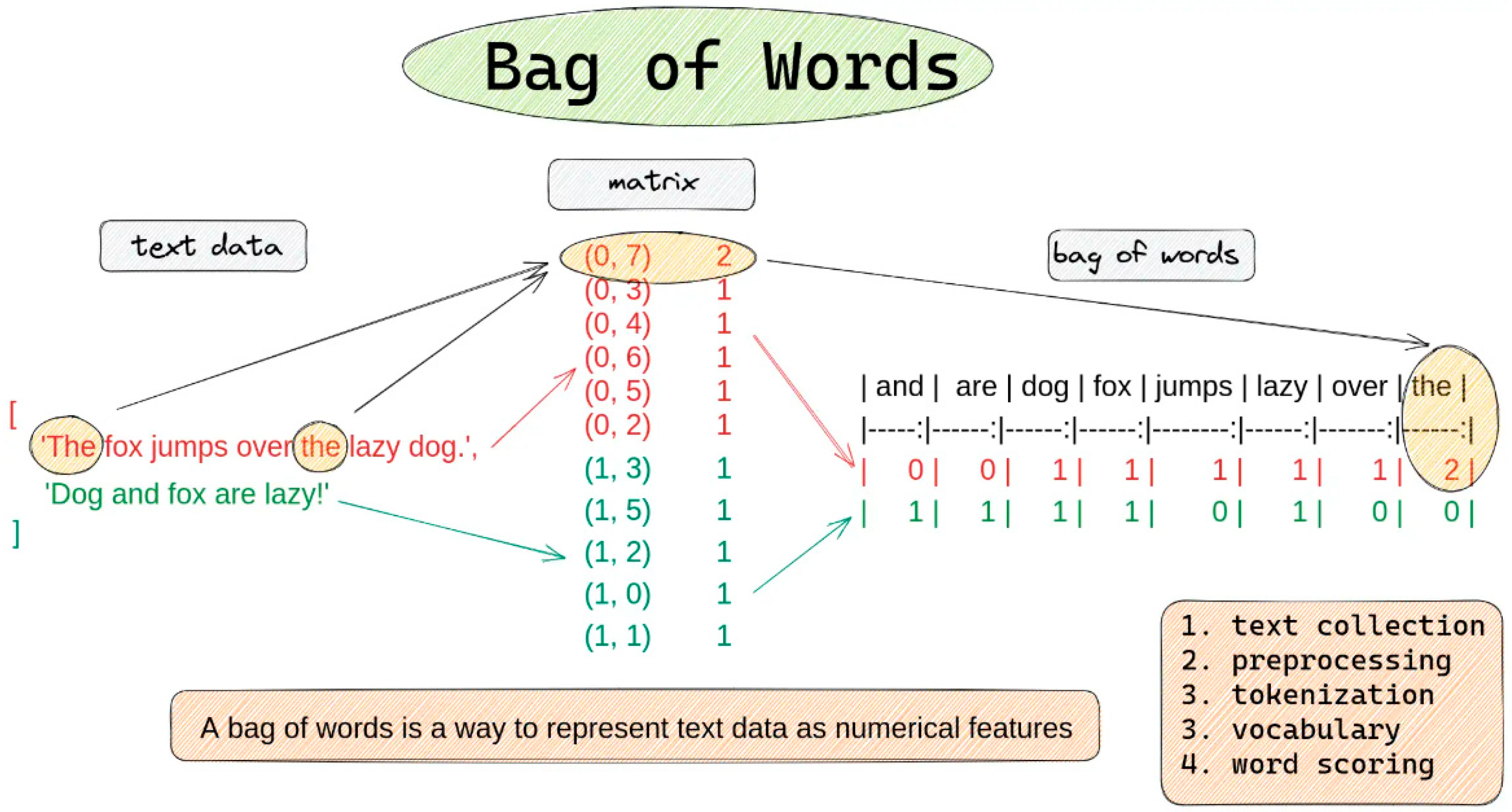

The paper discusses various text classification methods, highlighting that deep learning models, particularly distributed word representations like word2vec and Glove, outperform traditional methods such as Bag of Words (BOW). Contextual embeddings like BERT also show significant performance improvements. | - Improved text classification methods for massive data analysis. - Enhanced performance using advanced feature extraction techniques. |

| Journal Article | Text Classification Using Deep Learning Models: A Comparative Review | 2023 | [16] | - Analyze deep learning models for text classification tasks. - Address gaps, limitations, and future research directions in text classification. |

The paper conducts a literature review on various deep learning models for text classification, analyzing their gaps and limitations. It highlights previous studies' comparative results and discusses classification applications, guiding future research directions in this field. | - Guidance for future research in text classification. - Highlights challenges and potential directions in the field. |

| Journal Article | Survey on Text Classification | 2020 | [17] | - Classify documents into predefined classes effectively. - Compare various text representation schemes and classifiers. |

Previous studies on text classification have utilized various techniques, including supervised learning with labeled training documents, Naive Bayes, and Decision Tree algorithms. Challenges include the difficulty of creating labeled datasets and the limited applicability of individual classifiers across different domains. | - Detailed information on text classification concepts and algorithms. - Evaluation of algorithms using common performance metrics. |

| Journal Article | The Text Classification Method Based on BiLSTM and Multi-Scale CNN | 2024 | [18] | - Overview of deep learning in text classification. - Analyze research progress and technical approaches. |

Previous studies on text classification have transitioned from traditional machine learning methods to deep learning models, including attention mechanisms and pre-trained language models, highlighting significant progress and challenges in enhancing model performance and dataset quality across various domains. | - Overview of deep learning text classification methods. - Analysis of labeled datasets for research support. |

| Journal Article | Research on Text Classification Method Based on NLP | 2023 | [19] | - Describe text classification concepts and processes. - Explore deep learning models for text classification. |

Previous studies on text classification have explored various methods, including LSTM-based multi-task learning architectures, capsule networks, and hybrid models like RCNN, demonstrating advancements in feature extraction and improved performance in tasks such as sentiment analysis and spam recognition. | - Text classification methods are important for effectively classifying text-based data. - New ideas such as word embedding models and pre-training models have made great progress in text classification. |

| Book Chapter | A Comparative Study on Various Text Classification Methods | 2020 | [20] | - Analyze methods for efficient text classification. - Examine featurization techniques and their performance. |

The paper does not provide a review of previous studies on text classification. Instead, it focuses on analyzing various text classification methods and featurization techniques, such as bag of words, Tf-Idf vectorization, and Word2Vec approaches. | - Analyzes efficient text classification methods for decision-making. - Discusses various featurization techniques for improved performance. |

| Journal Article | Evaluating text classification: A benchmark study | 2024 | [21] | - Investigate necessity of complex models versus simple methods. - Assess performance across various classification tasks and datasets. |

The paper highlights a gap in existing literature, noting that previous research primarily compares similar types of methods without a comprehensive benchmark. This study aims to provide an extensive evaluation across various tasks, datasets, and model architectures. | - Simple methods can outperform complex models in certain tasks. - Negative correlation between F1 performance and complexity for small datasets. |

| Proceedings Article | Comparative Performance of Machine Learning Methods for Text Classification | 2020 | [22] | - Compare performance of machine learning and deep learning algorithms. - Explore scalability with larger data instances. |

Previous studies on text classification primarily tested machine learning and deep learning methods with relatively small-sized data instances. This paper builds on that by comparing these methods' performance and scalability using a larger dataset of 6,000 instances across six classes. | - Deep learning outperforms traditional methods in text classification. - Scalability of methods for larger data instances explored. |

| Journal Article | A Survey on Text Classification using Machine Learning Algorithms | 2019 | [23] | - Explore algorithms for automated text document classification. - Select best features and classification algorithms for accuracy. |

Previous studies on text classification have explored various methodologies, including feature selection techniques like Document Frequency Thresholding and Information Gain, and classification algorithms such as K-nearest Neighbors and Support Vector Machines, highlighting the importance of efficient keyword prioritization for accurate categorization. | - Automated text classification improves efficiency in document handling. - Reduces reliance on expert classification for large text documents. |

| Dataset | Text Classification Data from 15 Drug Class Review SLR Studies | 2023 | [24] | - Automate citation classification in systematic reviews. - Reduce workload in systematic review preparation. |

The paper references a study by Cohen et al. (2006) that focused on reducing workload in systematic review preparation through automated citation classification, providing a foundation for the datasets used in the current text classification research on drug class reviews. | - Automates citation classification in systematic reviews. - Reduces workload for researchers in drug class studies. |

| Proceedings Article | An Exploration of the Effectiveness of Machine Learning Algorithms for Text Classification | 2023 | [25] | - Explore effectiveness of machine learning algorithms for text classification. - Compare performance of various algorithms like SVM, KNN, CNN, RNN. |

The paper does not provide specific details on previous studies in text classification. It focuses on evaluating and comparing the performance of various machine learning algorithms, such as decision trees, SVM, KNN, CNN, and RNN for text classification tasks. | - Machine learning improves text classification accuracy and efficiency. - Algorithms can handle complex and large datasets effectively. |

| Proceedings Article | A Comparative Text Classification Study with Deep Learning-Based Algorithms | 2022 | [26] | - Compare deep learning algorithms for text classification. - Optimize hyperparameters and evaluate word embeddings effectiveness. |

The paper compares its results with previous studies in the literature, highlighting significant improvements in classification performance using deep learning algorithms and word embeddings. It specifically utilizes an open-source Turkish News benchmarking dataset for this comparative analysis. | - Improved text classification performance using deep learning algorithms. - Effective hyperparameter tuning enhances classification accuracy. |

| Proceedings Article | Classification Models of Text: A Comparative Study | 2021 |

[27] |

- Overview of classification process stages. - Survey and compare popular classification algorithms. |

The paper does not provide specific details on previous studies in text classification. Instead, it focuses on the classification process, including preprocessing, feature engineering, dimension decomposition, model selection, and evaluation, while surveying and comparing popular classification algorithms. | - Text classification has implications in education, politics, and finance. - The paper provides a comparative study of popular classification algorithms. |

| Journal Article | Trends and patterns of text classification techniques: a systematic mapping study | 2020 | [28] | - Provide an overview of text classification research trends and gaps. - Analyze research patterns, problems, and problem-solving methods in text classification. |

The paper systematically reviews ninety-six studies on text classification from 2006 to 2017, identifying nine main problems and analyzing research patterns, data sources, language choices, and applied techniques, highlighting significant trends and gaps in the field. | - Highlights trends and gaps in text classification research. - Identifies nine main problems in text classification area. |

| Journal Article | Research On Text Classification Based On Deep Neural Network | 2022 |

[29] |

- Design text representation and classification models using deep networks. - Improve text feature representation and classification accuracy. |

The paper highlights that traditional text classification methods, such as the bag-of-words model and vector space model, face challenges like loss of context, high dimensionality, and sparsity, prompting a shift towards deep learning techniques for improved performance. | - Deep learning models improve text classification performance compared to traditional methods. - The BRCNN and ACNN models proposed in the paper show better text feature representation and classification accuracy. |

2.2. Approaches to Text Categorization

2.2.1. Supervised Learning

- In supervised learning, models are trained using labeled datasets to classify new documents into predefined categories. Popular algorithms for this purpose include Logistic Regression, Naive Bayes, Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVM), and AdaBoost. For example, Naive Bayes has demonstrated impressive accuracy, reaching up to 96.86% in certain applications [30].

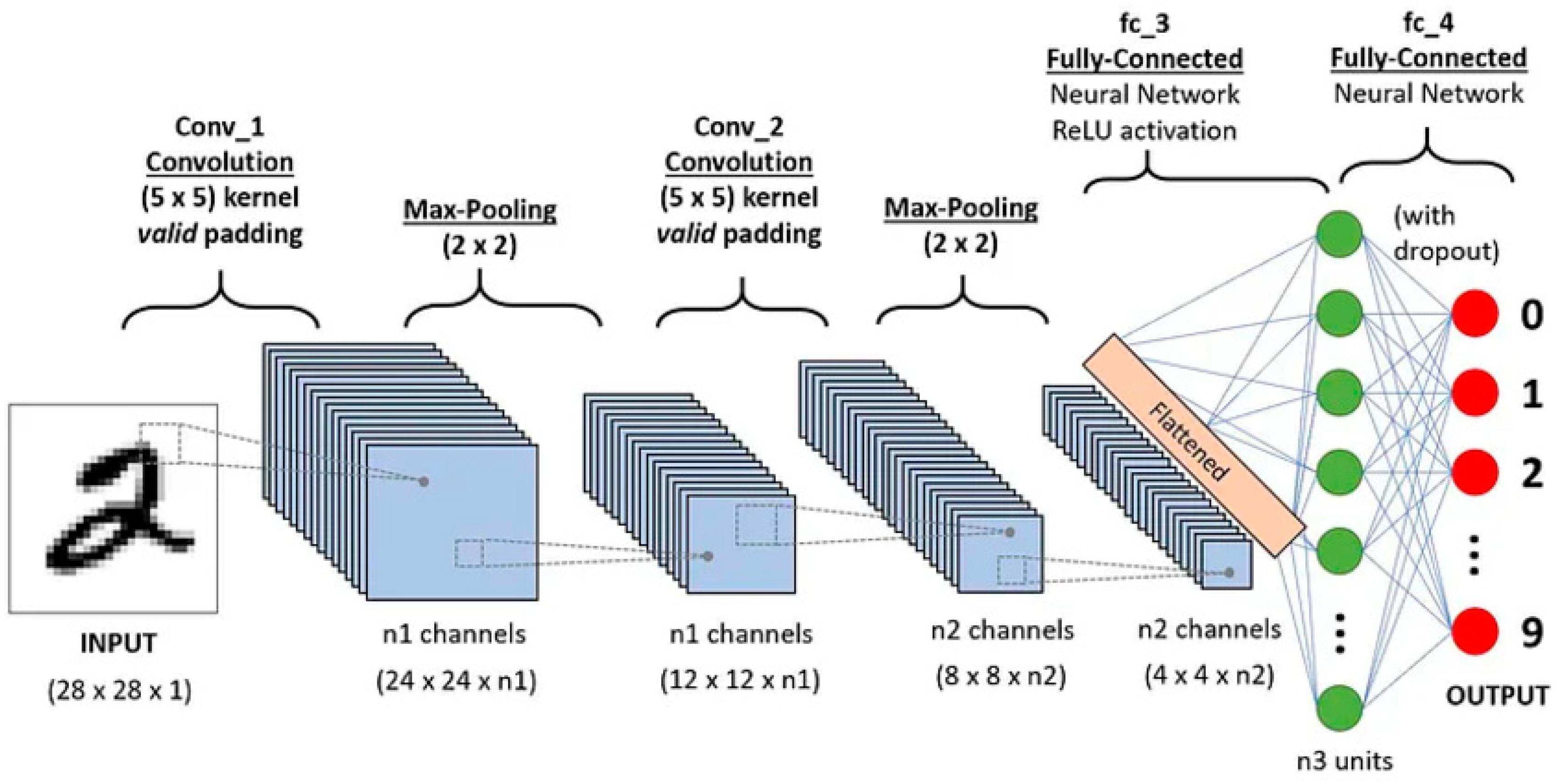

- Deep learning techniques, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, achieve high accuracy while requiring minimal feature engineering. For instance, LSTMs have demonstrated accuracy rates of up to 92% in specific tasks [31].

2.2.2. Unsupervised Learning

- Unsupervised learning techniques, including hierarchical clustering, k-means clustering, and probabilistic clustering, are used to group documents based on content similarity in cases where labeled data is not available [32].

- These techniques uncover inherent data structures and are instrumental in analyzing unlabeled datasets[4],

2.3. The Rise of Machine Learning in TC

- Naive Bayes: Effective for large vocabularies due to its probabilistic approach.

- SVM: Achieves precision by mapping text into high-dimensional spaces, helping identify closely related themes.

2.4. Benefits of Automated TC Over Manual Classification

- Scalability and Efficiency: Handles large datasets rapidly and consistently, unlike manual methods that are time-intensive and impractical for extensive collections.

- Objectivity: Applies standard criteria uniformly, eliminating human bias and ensuring reliable outcomes, crucial for domains like legal document classification.

- Real-Time Processing: Facilitates immediate classification, essential in industries like finance and journalism where timely decisions are critical [34].

2.5. Types of TC Tasks

- Binary Classification: This involves two classes, such as spam and non-spam emails, where each document belongs to one of the two categories [5].

- Multi-Label Classification: In this case, each document may belong to multiple categories simultaneously. For example, an academic paper may be categorized under multiple disciplines like biology and technology [5].

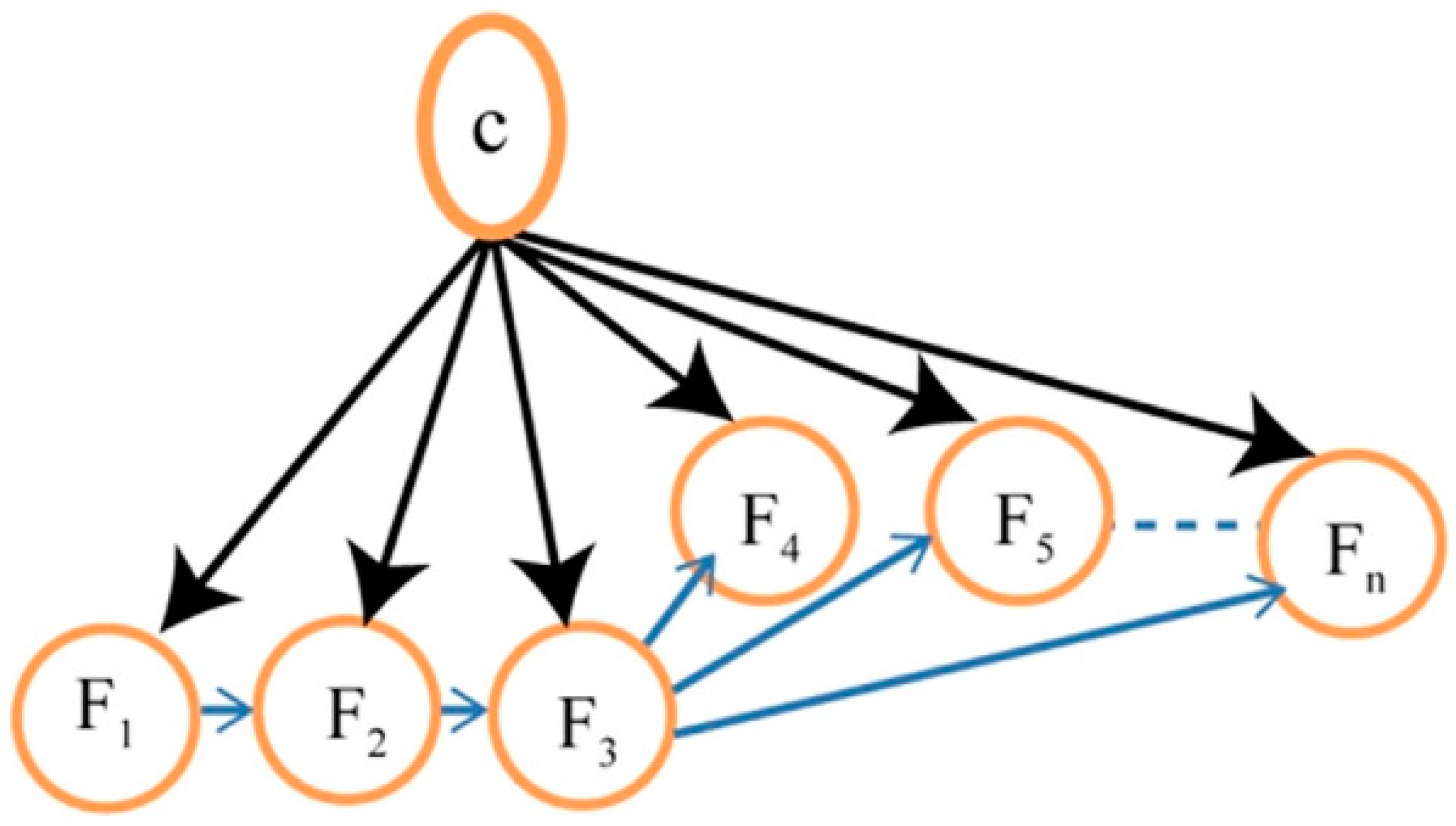

- Hierarchical Classification: Documents are classified into categories organized in a hierarchical format. This type is beneficial for large datasets with numerous categories [5].

2.5. Single-Label vs. Multi-Label Classification

- Single-Label Classification: Often approached using binary classification methods, where documents are classified into distinct categories without overlap [37].

- Multi-Label Classification: In this context, a document can belong to several categories, necessitating complex modeling to manage overlapping labels. Methods for handling multi-label classification often involve transforming the problem into multiple binary classification tasks [37].

2.7. Document-Pivoted vs. Category-Pivoted TC

- Category-Pivoted Categorization (CPC): In contrast, CPC classifies documents by first identifying the relevant category. This method is more complex, as it requires re-evaluating document classifications when new categories are added.

2.8. Hard Categorization vs. Ranking

- Hard Categorization: This method assigns each document to a single category, resulting in binary decisions about the classification of whether the text belongs to the category or not.

- Ranking: In contrast, ranking categorization involves generating a list of categories ranked by their relevance to the document. This approach provides a more nuanced view of a document's classification, allowing for further decision-making processes based on category probability.

2.9. Machine Learning vs. Knowledge Engineering in TC

2.9.1. Machine Learning

2.9.2. Knowledge Engineering

3. Applications of Text Categorization

3.1. Document Indexing for Information Retrieval Systems

3.2. Role of Controlled Vocabulary and Thesauri

3.3. Automated Document Organization and Archiving

3.4. Use in Corporate and News Media

3.5. Text Filtering and Content Personalization

3.6. Newsfeeds, Email Filtering, and Spam Detection

3.7. Word Sense Disambiguation (WSD)

3.8. Hierarchical Categorization of Web Content

4. Machine Learning Techniques in Text Categorization (TC)

4.1. Supervised Learning Techniques

4.2. Classifier Construction and Types of Algorithms

- Rule-based Systems: These classifiers use handmade rules, which are highly interpretable but less flexible for complicated or huge datasets [44]. Rule-based systems, on the other hand, continue to be useful in situations when plain, transparent decision-making is required.

- Decision Trees: Decision trees divide data based on certain criteria, making them intuitive and interpretable but susceptible to overfitting. Decision trees are effective for small to medium-sized text corpora, but they may struggle with scalability and feature depth [53].

- Naive Bayes: Naive Bayes is frequently used in TC due to its simplicity, efficiency, and resilience, especially in document categorization and spam filtering [58]. However, while the assumption of feature independence simplifies calculation, it can reduce efficiency when features are highly linked [57].Figure 1. Naive Based Classification [59].Figure 1. Naive Based Classification [59].

- d.

- Neural Networks: “Neural networks, particularly deep learning models, have transformed TC by allowing them to learn sophisticated, hierarchical text representations. Although neural networks often need big datasets and significant computer resources, they provide unrivaled accuracy in capturing semantic meaning and contextual nuances” [60].

4.3. Feature Selection and Engineering

4.4. Advanced Machine Learning Approaches to Text Categorization

4.4.1. Traditional ML Techniques

- Naive Bayes and Logistic Regression: Offer simplicity and effectiveness in text classification, with Naive Bayes achieving up to 96.86% accuracy in specific datasets [30].

- Support Vector Machines (SVM): Efficiently handle high-dimensional data and demonstrate strong performance with word embeddings.

- Random Forest (RF): Achieves a mean accuracy of 99.98% when combined with Word2Vec embeddings [62].

- K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) and Decision Trees: Useful for smaller datasets but less effective compared to SVM and RF [63].

4.4.2. Deep Learning Approaches

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): Capture spatial patterns in text, ideal for classification tasks.

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs): Particularly LSTMs and GRUs, excel at modeling sequential dependencies in text.

4.4.3. Hybrid and Ensemble Methods

5. Document Representation Techniques

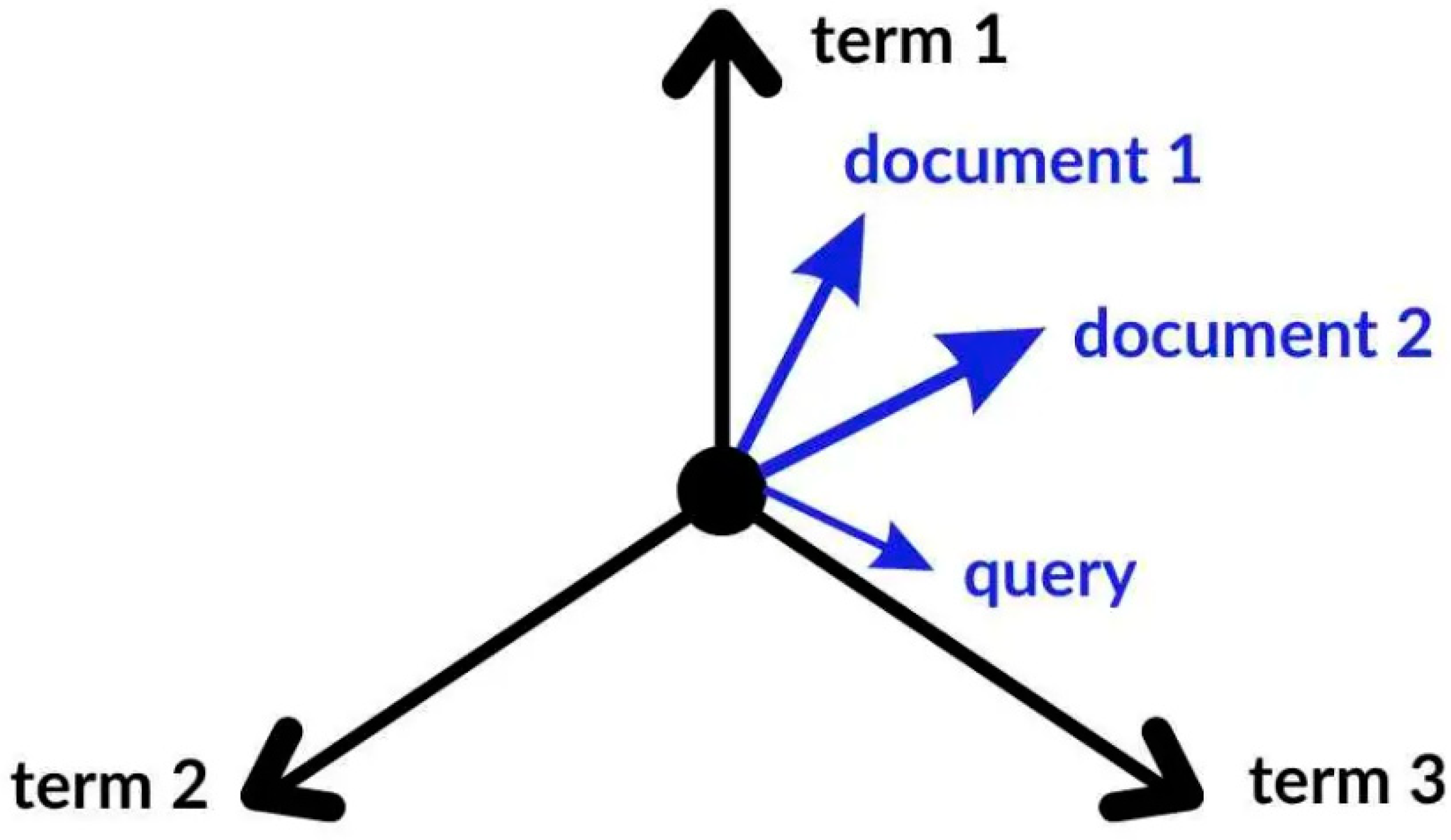

5.1. Vector Space Model (VSM)

5.2. Bag-of-Words and Beyond

5.3. Lexical Semantics and Text Tokenization

5.4. Word Stemming and Stop Word Removal

5.5. Weighting Schemes

5.6. Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF)

5.7. Other Weighting Schemes

6. Dimension Reduction in Text Categorization

6.1. Importance of Dimensionality Reduction

- Improved Efficiency: Streamlines computational demands, particularly during training and testing phases.

- Enhanced Interpretability: Simplifies understanding by focusing on the most significant features.

- Reduced Overfitting: Ensures the model learns generalizable patterns rather than noise specific to the training dataset.

6.2. Dimensionality Reduction in Support Vector Machines (SVMs)

- Linear Kernel

- 2.

- Polynomial Kernel

- 3.

- Gaussian RBF Kernel

6.3. Text Representation in Dimensionality Reduction

- Rows: Represent terms.

- Columns: Represent documents.

- Entries (aija_[65]aij): Indicate the frequency or presence of term iii in document jjj.

6.4. Common Methods for Term Selection

6.4.1. Document Frequency

6.4.2. Chi-Square Test

6.4.3. Mutual Information

6.4.4. Term Clustering

6.4.5. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

6.5. Comparison of Dimensionality Reduction Methods

6.5.1. Term Extraction Techniques

6.5.2. Term Extraction Techniques

7. Evaluation of Text Categorization Models

7.1. Metrics for Performance Evaluation

- Accuracy

- b.

- Precision

- c.

- Recall (Sensitivity)

| Assign Mean | Corr. Mean | P | R | F |

| 8.6 | 3.6 | 41.5 | 46.9 | 44.0 |

- d.

- Breakeven Point (BEP)

7.2. Validation Techniques

- a.

- k-Fold Cross-Validation

7.3. Challenges in Model Evaluation

- There are only a few lexical databases for a small number of languages, hence knowledge-based systems can be developed only for those languages. Knowledge-based systems are mostly specific in nature for certain languages and subjects, so they cannot easily be used for other languages. These systems can be costly to maintain since languages keep changing. They are also not available for some subjects. [89]. Knowledge-based systems rely on lexical databases, which are limited to a few languages and domains, making them costly and hard to adapt. Researchers are urged to develop these resources for under-represented languages to expand system usability.

- Building and implementing a deep learning-based system can be highly resource-intensive, as training such systems requires expensive hardware and significant computational power, which must be accounted for. [89].

- The meaning relationships of the words in a text document give problems in text categorization, hence making it hard to create a system. Unorganized text data is a tough job for getting meaning relationships to make text categorization systems. [89].

8. Challenges in Machine Learning-Based Text Classification

8.1. Overfitting and Underfitting in TC

8.2. Class Imbalance in TC

8.3. Complexity in Feature Space

8.4. Ambiguity and Polysemy in Language

9. Advancements and Emerging Trends in Text

9.1. Deep Learning for Text Categorization

9.2. CNNs and RNNs for TC Tasks

9.3. Transfer Learning and Pre-Trained Language Models

9.3.1. Use of BERT, GPT, and Similar Models

9.3.2. Hybrid Approaches Combining Knowledge Engineering and ML

10. Future Directions and Research Opportunities

10.1. Multi-Language and Cross-Cultural Text Classification

10.1.1. Importance of Cross-Language Communication

10.1.2. Advancements in Multilingual NLP

10.1.3. Cross-Lingual Transfer Learning

10.1.4. Cultural Sensitivity in Text Classification

10.1.5. Future Research Directions

Universal Multilingual Models

Low-Resource Languages

Enhanced Language Identification

Cultural Awareness in Models

Integration with Real-Time and Multimodal Systems

Ethical AI and Bias Mitigation

Hybrid and Explainable Models

10.2. Real-Time Text Categorization Applications

10.2.1. The Need for Real-Time Classification

10.2.2. Scalability and Speed in Real-Time Systems

10.2.3. Incremental Learning for Dynamic Content

10.2.4. Reducing Latency While Preserving Accuracy

10.2.5. Future Research Opportunities

High-Throughput Systems

Dynamic Adaptation

Applications in Diverse Domains

- Social Media Analytics: Identifying trends, sentiment, and emerging topics in real-time.

- Spam Detection: Filtering spam messages or malicious content as they are generated.

- Fraud Prevention: Monitoring financial transactions or communications for suspicious patterns.

- Customer Support Chatbots: Providing instant, context-aware responses to user queries.

Real-Time Multimodal Integration

Latency-Aware Optimization

Scalability for Global Applications

Context-Aware Personalization

Ethical Considerations and Transparency

10.3. Integration with Other NLP Tasks

10.3.1. Expanding the Scope of NLP Integration

10.3.2. Named Entity Recognition (NER)

10.3.3. Parsing Techniques

10.3.4. Information Extraction (IE)

10.3.5. Multi-Task Learning Frameworks

10.4. Advancing Multimodal Text Classification

10.4.1. Combining Modalities for Comprehensive Analysis

10.4.2. Practical Applications

- E-Commerce: Platforms can integrate sentiment analysis and NER to classify product reviews, extract brand mentions, and monitor customer feedback in real-time.

- Social Media: By combining text-based sentiment analysis with image-based emotion detection, platforms can enhance their content moderation and analytics capabilities.

10.4.3. Future Research Directions in Multimodal Text Classification

10.4.4. Dynamic Multimodal Fusion Techniques

10.4.5. Temporal Multimodal Analysis

10.4.6. Real-Time Multimodal Interaction

10.4.7. Cross-Modal Transfer Learning

10.4.8. Domain-Specific Multimodal Solutions

- Healthcare: Analyzing patient notes alongside medical images for enhanced diagnostic accuracy.

- Finance: Integrating financial reports (text) with market trend graphs (visuals) to improve investment decision-making.

- Legal Analysis: Combining contract text with associated diagrams or annotations to classify clauses efficiently.

10.4.9. Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) Integration

10.4.10. Emotion and Context Detection

10.4.11. Energy-Efficient Multimodal Models

10.4.12. Interactive Multimodal Systems

10.4.13. Multimodal Anomaly Detection

| Research Focus | Future Research Direction | Potential Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Multilingual Models | Develop generalized models for multilingual text classification with minimal labeled data. | Cross-cultural communication, multilingual customer support, and global content moderation. |

| Low-Resource Languages | Use transfer learning, domain adaptation, and unsupervised methods to address data scarcity. | Language preservation, text analysis in underserved regions, and niche domain categorization. |

| Enhanced Language Identification | Improve techniques for detecting and processing multiple languages in text. | Multilingual user-generated content analysis and global social media monitoring. |

| Cultural Awareness in Models | Embed cultural sensitivity to improve classification relevance across diverse contexts. | Sentiment analysis, cross-border marketing, and international public opinion tracking. |

| High-Throughput Systems | Develop systems capable of processing large-scale, real-time data streams with minimal latency. | Live news categorization, stock market monitoring, and emergency response systems. |

| Dynamic Adaptation | Enhance models to adjust to shifting patterns and evolving content in real-time. | Social media analytics, adaptive spam filtering, and customer sentiment tracking. |

| Multimodal Integration | Combine text with other modalities (images, videos, audio) for holistic content analysis. | Social media content moderation, e-commerce review analysis, and multimedia news classification. |

| Temporal Multimodal Analysis | Analyze how user sentiment or trends evolve over time using multiple data types. | Campaign monitoring, real-time sentiment tracking, and user behavior analysis. |

| Real-Time Systems | Optimize latency and computational efficiency for real-time applications. | Chatbots, fraud detection, and personalized content delivery. |

| Cross-Modal Transfer Learning | Enable knowledge transfer between text and other data modalities for enhanced classification. | Healthcare diagnostics, financial trend analysis, and multimedia content categorization. |

| Domain-Specific Frameworks | Design tailored models for specific industries like healthcare, finance, and legal analysis. | Medical text categorization, contract clause extraction, and investment report analysis. |

| AR/VR Integration | Integrate text categorization into augmented and virtual reality systems. | Interactive learning environments, immersive customer support, and AR-based real-time text translation. |

| Emotion and Context Detection | Combine multimodal inputs for nuanced emotion and context understanding. | Mental health monitoring, sentiment-based recommendations, and adaptive marketing strategies. |

| Interactive Multimodal Systems | Develop systems allowing real-time user feedback to refine classification accuracy. | Live content moderation, chatbot systems, and collaborative filtering in e-commerce. |

| Ethical Considerations and Bias Mitigation | Focus on identifying and mitigating biases in training data and algorithms. | Recruitment systems, content moderation for sensitive topics, and legal document categorization. |

| Explainable AI and Hybrid Models | Combine rule-based systems with ML for interpretability and transparency. | Regulatory compliance, healthcare decision support, and consumer trust-building. |

| Energy-Efficient Architectures | Research architectures that optimize resource usage for text categorization. | Mobile applications, edge computing, and sustainable AI deployment in resource-constrained settings. |

| Anomaly Detection | Develop methods to detect inconsistencies across multimodal data streams. | Fraud detection, cybersecurity monitoring, and disaster response systems. |

| Real-Time Multilingual Systems | Extend real-time systems to handle multiple languages dynamically. | Global event monitoring, real-time multilingual chatbots, and international e-commerce platforms. |

11. Conclusions

References

- Joachims, T. and F. Sebastiani, Guest editors' introduction to the special issue on automated text categorization. Journal of Intelligent Information Systems, 2002. 18(2-3): p. 103. [CrossRef]

- Knight, K., Mining online text. Communications of the ACM, 1999. 42(11): p. 58-61.

- Pazienza, M.T., Information extraction. 1999: Springer.

- Sebastiani, F., Text categorization: Advances and challenges. Computational Linguistics,, 2024. 50(2): p. 205–245.

- Yang, Y. and T. Joachims, Text categorization. Scholarpedia, 2008. 3(5): p. 4242.

- Lewis, D.D. and P.J. Hayes, Special issue on text categorization. Information Retrieval Journal, 1994. 2(4): p. 307-340.

- Manning, C. and H. Schütze, Foundations of Statistical Natural Language Processing. 1999: MIT Press.

- Paaß, G., Document classification, information retrieval, text and web mining. Handbook of Technical Communication, 2012. 8: p. 141.

- Larabi-Marie-Sainte, S., M. Bin Alamir, and A. Alameer, Arabic Text Clustering Using Self-Organizing Maps and Grey Wolf Optimization. Applied Sciences, 2023. 13(18): p. 10168. [CrossRef]

- Dhar, V., The evolution of text classification: Challenges and opportunities. AI & Society, 2021. 36(1): p. 123-135.

- Chen, Y. and X.-M. Zhang, Research on Intelligent Natural Language Texts Classification. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 2021.

- Haoran, Z. and L. Lei, The Research Trends of Text Classification Studies (2000–2020): A Bibliometric Analysis. SAGE Open, 2022.

- Xujuan, Z., et al., A survey on text classification and its applications. 2020.

- Qian, L., et al., A Survey on Text Classification: From Traditional to Deep Learning. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology, 2022.

- Arsime, D., Case Studies of Several Popular Text Classification Methods. 2022.

- Zulqarnain, M., et al., Text Classification Using Deep Learning Models: A Comparative Review. Cloud Computing and Data Science, 2024: p. 80-96. [CrossRef]

- Leena, B. and K.V. Satish, Survey on Text Classification. 2020.

- Zhaowei, Z., et al., The Text Classification Method Based on BiLSTM and Multi-Scale CNN. 2024.

- Mengnan, W., Research on Text Classification Method Based on NLP. Advances in Computer, Signals and Systems, 2022.

- Samarth, K., et al., A Comparative Study on Various Text Classification Methods. 2019.

- Manon, R., et al., Evaluating text classification: A benchmark study. Expert Systems with Applications, 2024.

- Bello, A.M., et al., Comparative Performance of Machine Learning Methods for Text Classification. 2020.

- Harshitha, C.P., et al. A Survey on Text Classification using Machine Learning Algorithms. 2019.

- Paweł, C., Text Classification Data from 15 Drug Class Review SLR Studies. 2022.

- Ankita, A., et al. An Exploration of the Effectiveness of Machine Learning Algorithms for Text Classification. 2023.

- Ömer, K. and A. Özlem. A Comparative Text Classification Study with Deep Learning-Based Algorithms. 2022.

- Tiffany, Z., Classification Models of Text: A Comparative Study. 2021.

- Maw, M., et al., Trends and patterns of text classification techniques: a systematic mapping study. Malaysian Journal of Computer Science, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Dea, W.K., Research On Text Classification Based On Deep Neural Network. International Journal of Communication Networks and Information Security, 2022.

- Dawar, I., et al., Text Categorization using Supervised Machine Learning Techniques. 2023.

- Kowsari, K., et al., Text classification algorithms: A survey. Information, 2019. 10(4): p. 150. [CrossRef]

- Quazi, S. and S.M. Musa, Performing Text Classification and Categorization through Unsupervised Learning. 2023.

- Karathanasi, L.C., et al., A Study on Text Classification for Applications in Special Education. International Conference on Software, Telecommunications and Computer Networks, 2021.

- Kadhim, A.I., Survey on supervised machine learning techniques for automatic text classification. Artificial intelligence review, 2019. 52(1): p. 273-292. [CrossRef]

- Ittoo, A. and A. van den Bosch, Text analytics in industry: Challenges, desiderata and trends. Computers in Industry, 2016. 78: p. 96-107. [CrossRef]

- Shen, D., Text Categorization. 2009.

- Sajid, N.A., et al., Single vs. multi-label: The issues, challenges and insights of contemporary classification schemes. Applied Sciences, 2023. 13(11): p. 6804. [CrossRef]

- Chen, R., W. Zhang, and X. Wang, Machine learning in tropical cyclone forecast modeling: A review. Atmosphere, 2020. 11(7): p. 676. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., et al., A review on the application of machine learning methods in tropical cyclone forecasting. Frontiers in Earth Science, 2022. 10: p. 902596. [CrossRef]

- Gasparetto, A., et al., A survey on text classification algorithms: From text to predictions. Information, 2022. 13(2): p. 83. [CrossRef]

- Shortliffe, E.H., B.G. Buchanan, and E.A. Feigenbaum, Knowledge engineering for medical decision making: A review of computer-based clinical decision aids. Proceedings of the IEEE, 1979. 67(9): p. 1207-1224. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M., et al., A data-driven knowledge acquisition system: An end-to-end knowledge engineering process for generating production rules. IEEE Access, 2018. 6: p. 15587-15607. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D., Applied analytics through case studies using Sas and R: implementing predictive models and machine learning techniques. 2018: Apress.

- Sebastiani, F., Machine learning in automated text categorization. ACM computing surveys (CSUR), 2002. 34(1): p. 1-47. [CrossRef]

- Fuhr, N. and G. Knorz. Retrieval test evaluation of a rule based automatic indexing (AIR/PHYS). in Proceedings of the 7th annual international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval. 1984.

- Borko, H. and M. Bernick, Automatic document classification. Journal of the ACM (JACM), 1963. 10(2): p. 151-162. [CrossRef]

- Larkey, L.S. A patent search and classification system. in Proceedings of the fourth ACM conference on Digital libraries. 1999.

- Hayes, P.J. and S.P. Weinstein. CONSTRUE/TIS: A System for Content-Based Indexing of a Database of News Stories. in IAAI. 1990.

- Androutsopoulos, I., et al. An experimental comparison of naive Bayesian and keyword-based anti-spam filtering with personal e-mail messages. in Proceedings of the 23rd annual international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval. 2000.

- Drucker, H., D. Wu, and V.N. Vapnik, Support vector machines for spam categorization. IEEE Transactions on Neural networks, 1999. 10(5): p. 1048-1054. [CrossRef]

- Gale, W.A. and K. Church, A program for aligning sentences in bilingual corpora. Computational Linguistics. 1993.

- Chakrabarti, S., et al., Automatic resource compilation by analyzing hyperlink structure and associated text. Computer networks and ISDN systems, 1998. 30(1-7): p. 65-74. [CrossRef]

- Kowsari, K., et al., Text classification algorithms: A survey. Information 10, 4 (2019), 150. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, S.M., Sentiment analysis: Detecting valence, emotions, and other affectual states from text, in Emotion measurement. 2016, Elsevier. p. 201-237.

- Yang, Y. and X. Liu. A re-examination of text categorization methods. in Proceedings of the 22nd annual international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval. 1999.

- Forman, G., An extensive empirical study of feature selection metrics for text classification. J. Mach. Learn. Res., 2003. 3(Mar): p. 1289-1305.

- Aggarwal, C.C. and C. Zhai, An introduction to text mining, in Mining text data. 2012, Springer. p. 1-10.

- McCallum, A. and K. Nigam. A comparison of event models for naive bayes text classification. in AAAI-98 workshop on learning for text categorization. 1998. Madison, WI.

- Luo, X., Efficient English text classification using selected machine learning techniques. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 2021. 60(3): p. 3401-3409. [CrossRef]

- Young, T., et al., Recent trends in deep learning based natural language processing. ieee Computational intelligenCe magazine, 2018. 13(3): p. 55-75. [CrossRef]

- Guyon, I. and A. Elisseeff, An introduction to variable and feature selection. Journal of machine learning research, 2003. 3(Mar): p. 1157-1182.

- Mondal, S., et al. Cancer Text Article Categorization and Prediction Model Based on Machine Learning Approach. 2023.

- Agarwal, A., et al. An Exploration of the Effectiveness of Machine Learning Algorithms for Text Classification. 2023.

- Saha, S., A comprehensive guide to convolutional neural networks — the ELI5 way. 2018.

- Ali, S.I.M., et al., Machine learning for text document classification-efficient classification approach. IAES International Journal of Artificial Intelligence, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Valluri, D., S. Manne, and N. Tripuraneni. Custom Dataset Text Classification: An Ensemble Approach with Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models. 2023.

- Manning, C.D., Introduction to information retrieval. 2008, Cambridge university press.

- Salton, G., A. Wong, and C.-S. Yang, A vector space model for automatic indexing. Communications of the ACM, 1975. 18(11): p. 613-620.

- Van Otten, N., Vector Space Model Made Simple With Examples & Tutorial In Python. Spot Intelligence, 2023.

- Mikolov, T., Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. arXiv preprint arXiv:1301.3781, 2013. 3781.

- DataScienctyst. How to Create a Bag of Words in Pandas Python. Data Scientyst 2023 2023/01/10 [cited 2024 Novebmer 24]; Available from: https://datascientyst.com/create-a-bag-of-words-pandas-python/.

- Lovins, J.B., Development of a stemming algorithm. Mech. Transl. Comput. Linguistics, 1968. 11(1-2): p. 22-31.

- Ramos, J. Using tf-idf to determine word relevance in document queries. in Proceedings of the first instructional conference on machine learning. 2003. Citeseer.

- Salton, G. and C. Buckley, Term-weighting approaches in automatic text retrieval. Information processing & management, 1988. 24(5): p. 513-523. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S. and H. Zaragoza, The probabilistic relevance framework: BM25 and beyond. Foundations and Trends® in Information Retrieval, 2009. 3(4): p. 333-389. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., et al. Entropy-based term weighting schemes for text categorization in VSM. in 2015 IEEE 27th International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI). 2015. IEEE.

- Jones, K.S., S. Walker, and S.E. Robertson, A probabilistic model of information retrieval: development and comparative experiments: Part 2. Information processing & management, 2000. 36(6): p. 809-840.

- Said, D.A., Dimensionality reduction techniques for enhancing automatic text categorization. Cairo: Faculty of Engineering at Cairo University Master of science, 2007.

- Murty, M. and R. Raghava, Kernel-based SVM, in Support vector machines and perceptrons: Learning, optimization, classification, and application to social networks. 2016. p. 57-67.

- Li, B., et al. Weighted document frequency for feature selection in text classification. in 2015 International Conference on Asian Language Processing (IALP). 2015. IEEE.

- Christian, H., M.P. Agus, and D. Suhartono, Single document automatic text summarization using term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF). ComTech: Computer, Mathematics and Engineering Applications, 2016. 7(4): p. 285-294. [CrossRef]

- Peng, T., L. Liu, and W. Zuo, PU text classification enhanced by term frequency–inverse document frequency-improved weighting. Concurrency and computation: practice and experience, 2014. 26(3): p. 728-741. [CrossRef]

- Magnello, M.E., Karl Pearson, paper on the chi square goodness of fit test (1900), in Landmark Writings in Western Mathematics 1640-1940. 2005, Elsevier. p. 724-731.

- Greenwood, P.E. and M.S. Nikulin, A guide to chi-squared testing. Vol. 280. 1996: John Wiley & Sons.

- Chen, Y.-T. and M.C. Chen, Using chi-square statistics to measure similarities for text categorization. Expert systems with applications, 2011. 38(4): p. 3085-3090. [CrossRef]

- Meesad, P., P. Boonrawd, and V. Nuipian. A chi-square-test for word importance differentiation in text classification. in Proceedings of international conference on information and electronics engineering. 2011.

- Wang, G. and F.H. Lochovsky. Feature selection with conditional mutual information maximin in text categorization. in Proceedings of the thirteenth ACM international conference on Information and knowledge management. 2004.

- Lewis, D.D. An evaluation of phrasal and clustered representations on a text categorization task. in Proceedings of the 15th annual international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval. 1992.

- Dhar, A., et al., Text categorization: past and present. Artificial Intelligence Review, 2021. 54(4): p. 3007-3054. [CrossRef]

- Lhazmir, S., I. El Moudden, and A. Kobbane. Feature extraction based on principal component analysis for text categorization. in 2017 international conference on performance evaluation and modeling in wired and wireless networks (PEMWN). 2017. IEEE.

- Bafna, P., D. Pramod, and A. Vaidya. Document clustering: TF-IDF approach. in 2016 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, and Optimization Techniques (ICEEOT). 2016. IEEE.

- Franke, T.M., T. Ho, and C.A. Christie, The chi-square test: Often used and more often misinterpreted. American journal of evaluation, 2012. 33(3): p. 448-458.

- Tschannen, M., et al., On mutual information maximization for representation learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.13625, 2019.

- Cardoso-Cachopo, A. and A.L. Oliveira. An empirical comparison of text categorization methods. in International Symposium on String Processing and Information Retrieval. 2003. Springer.

- Yang, Y., An evaluation of statistical approaches to text categorization. Information retrieval, 1999. 1(1): p. 69-90. [CrossRef]

- Baldi, P., et al., Assessing the accuracy of prediction algorithms for classification: an overview. Bioinformatics, 2000. 16(5): p. 412-424. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.E. and P. Srinivasan, Hierarchical text categorization using neural networks. Information retrieval, 2002. 5: p. 87-118. [CrossRef]

- Guo, G., et al., Using k nn model for automatic text categorization. Soft Computing, 2006. 10: p. 423-430. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.D. Evaluating text categorization i. in Speech and Natural Language: Proceedings of a Workshop Held at Pacific Grove, California. 1991.

- Wang, B., et al. A pipeline for optimizing f1-measure in multi-label text classification. in 2018 17th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA). 2018.

- Hulth, A. and B. Megyesi. A study on automatically extracted keywords in text categorization. in Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Computational Linguistics and 44th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 2006.

- Wong, T.-T., Performance evaluation of classification algorithms by k-fold and leave-one-out cross validation. Pattern recognition, 2015. 48(9): p. 2839-2846. [CrossRef]

- Moss, H.B., D.S. Leslie, and P. Rayson, Using JK fold cross validation to reduce variance when tuning NLP models. arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.07139, 2018.

- Marcot, B.G., and Hanea, A. M. , What is an optimal value of k in k-fold cross-validation in discrete Bayesian network analysis? 2009–2031, 2021. 3: p. 36. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y., et al. How important is the train-validation split in meta-learning? in International Conference on Machine Learning. 2021. PMLR.

- Vabalas, A., et al., Machine learning algorithm validation with a limited sample size. PloS one, 2019. 14(11): p. e0224365. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., L. Zhang, and Y. Jiang. Overfitting and underfitting analysis for deep learning based end-to-end communication systems. in 2019 11th international conference on wireless communications and signal processing (WCSP). 2019. IEEE.

- Bu, C. and Z. Zhang. Research on overfitting problem and correction in machine learning. in Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2020. IOP Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Dogra, V., et al., A Complete Process of Text Classification System Using State-of-the-Art NLP Models. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2022. 2022(1): p. 1883698. [CrossRef]

- Hachiya, H., et al., Multi-class AUC maximization for imbalanced ordinal multi-stage tropical cyclone intensity change forecast. Machine Learning with Applications, 2024. 17: p. 100569. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., H.T. Loh, and A. Sun, Imbalanced text classification: A term weighting approach. Expert systems with Applications, 2009. 36(1): p. 690-701. [CrossRef]

- Nagy, G. and X. Zhang, Simple statistics for complex feature spaces, in Data Complexity in Pattern Recognition. 2006, Springer. p. 173-195.

- Le, P.Q., et al., Representing visual complexity of images using a 3d feature space based on structure, noise, and diversity. Journal of Advanced Computational Intelligence Vol, 2012. 16(5). [CrossRef]

- Mars, M., From word embeddings to pre-trained language models: A state-of-the-art walkthrough. Applied Sciences, 2022. 12(17): p. 8805. [CrossRef]

- Sinjanka, Y., U.I. Musa, and F.M. Malate, Text Analytics and Natural Language Processing for Business Insights: A Comprehensive Review. vol.

- Bashiri, H. and H. Naderi, Comprehensive review and comparative analysis of transformer models in sentiment analysis. Knowledge and Information Systems, 2024: p. 1-57. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A., A. Patel, and M. Shah, A comprehensive review on resolving ambiguities in natural language processing. AI Open, 2021. 2: p. 85-92. [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, I.S., Text Simplification Using Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning for Better Language Understandability. 2024, Ph. D. thesis, The Australian National University.

- Garg, R., et al., Potential use-cases of natural language processing for a logistics organization, in Modern Approaches in Machine Learning and Cognitive Science: A Walkthrough: Latest Trends in AI, Volume 2. 2021, Springer. p. 157-191.

- Kim, Y., Convolutional neural networks for sentence classification In: Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 1746-1751. ACL. 2014.

- Johnson, R. and T. Zhang, Effective use of word order for text categorization with convolutional neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.1058, 2014.

- Yang, Z., et al. Hierarchical attention networks for document classification. in Proceedings of the 2016 conference of the North American chapter of the association for computational linguistics: human language technologies. 2016.

- Schmidt, R.M., Recurrent neural networks (rnns): A gentle introduction and overview. arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.05911, 2019.

- Devlin, J., Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805, 2018.

- Radford, A., et al., Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog, 2019. 1(8): p. 9.

- Brown, T.B., Language models are few-shot learners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.14165, 2020.

- Azevedo, B.F., A.M.A. Rocha, and A.I. Pereira, Hybrid approaches to optimization and machine learning methods: a systematic literature review. Machine Learning, 2024: p. 1-43. [CrossRef]

- Willard, J., et al., Integrating scientific knowledge with machine learning for engineering and environmental systems. ACM Computing Surveys, 2022. 55(4): p. 1-37. [CrossRef]

- Banu, S. and S. Ummayhani, Text summarisation and translation across multiple languages. Journal of Scientific Research and Technology, 2023: p. 242-247.

- Orosoo, M., et al. Enhancing Natural Language Processing in Multilingual Chatbots for Cross-Cultural Communication. in 2024 5th International Conference on Intelligent Communication Technologies and Virtual Mobile Networks (ICICV). 2024. IEEE.

- Liang, L. and S. Wang, Spanish Emotion Recognition Method Based on Cross-Cultural Perspective. Frontiers in psychology, 2022. 13: p. 849083. [CrossRef]

- Artetxe, M., G. Labaka, and E. Agirre, Translation artifacts in cross-lingual transfer learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.04721, 2020.

- Schuster, S., et al., Cross-lingual transfer learning for multilingual task oriented dialog. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.13327, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., et al., A survey on text classification and its applications. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Yu, M., et al., Deep learning for real-time social media text classification for situation awareness–using Hurricanes Sandy, Harvey, and Irma as case studies, in Social Sensing and Big Data Computing for Disaster Management. 2020, Routledge. p. 33-50.

- Demirsoz, O. and R. Ozcan, Classification of news-related tweets. Journal of Information Science, 2017. 43(4): p. 509-524. [CrossRef]

- Van de Ven, G.M., T. Tuytelaars, and A.S. Tolias, Three types of incremental learning. Nature Machine Intelligence, 2022. 4(12): p. 1185-1197. [CrossRef]

- Yan, H., et al., A unified generative framework for various NER subtasks. 2021.

- Mohit, B., Named entity recognition, in Natural language processing of semitic languages. 2014, Springer. p. 221-245.

- Bui, D.D.A., G. Del Fiol, and S. Jonnalagadda, PDF text classification to leverage information extraction from publication reports. Journal of biomedical informatics, 2016. 61: p. 141-148. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y., R. Dong, and B. Smyth. Why I like it: multi-task learning for recommendation and explanation. 2018.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).