Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Randia spp. is a medicinal plant traditionally used in the treatment of various diseases. In this study, the phytochemical composition and the antioxidant, antiproliferative, and cytotoxic activities of hydroalcoholic extracts from fresh and dried Randia spp. fruits were evaluated. The phytochemical profile was determined through qualitative assays and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Antioxidant activity was assessed using the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and 2,2-azinobis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) assays. The antiproliferative effect was tested against CaCo-2 cells (human colon adenocarcinoma), while cytotoxicity was evaluated using J774.2 murine macrophages, and the selectivity index (SI) was calculated. The fresh and dried fruit extracts contained 50.27 and 47.22 mg QE/g extract of total phenols (TPC), and 27.08 and 35.53 mg QE/g extract of total flavonoids (TFC), respectively. In fresh fruit extracts, four phenolic acids (caffeic, hydroxybenzoic, ferulic, and coumaric) and one flavonoid (kaempferol) were identified, while dried fruit extracts contained ferulic acid, vanillic acid, and kaempferol. Kaempferol was the predominant compound in both extracts (137.55 and 42.10 mg/g dry sample in fresh and dried fruits, respectively). Both extracts displayed antioxidant activity, with IC₅₀ values of 18.29 mg/mL (DPPH) and 8.70 mg/mL (ABTS). Among the tested samples, the dried fruit extract demonstrated the highest antiproliferative activity. Furthermore, the extract showed moderate antiproliferative effects against CaCo-2 cells (IC₅₀ 25.44 ± 0.16 µg/mL) and low cytotoxicity toward J774.2 cells (CC₅₀ > 100 µg/mL), resulting in an SI = 3.92. Overall, the antioxidant and antiproliferative activities can be attributed mainly to kaempferol, given its high abundance in both extracts. The favorable selectivity index suggests that hydroalcoholic extracts of Randia spp. are safe and effective, highlighting their potential as candidates for further preclinical and clinical evaluations.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Preparation

2.2. Extraction Procedures and Traditional Wine Preparation Techniques.

2.3. Phytochemical Profile

2.3.1. Qualitative Identification of Families

2.3.2. Total Polyphenol Content

2.3.2. Total Flavonoid Content

2.4. Identification of Phenols by HPLC

2.5. Antioxidant Activity

2.6. Antiproliferative Activity and Cytotoxicity

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phytochemical Profile

3.1.1. Qualitative Family Identification

3.1.2. Total Polyphenol and Flavonoid Content

3.1.3. Identification of Phenols by HPLC

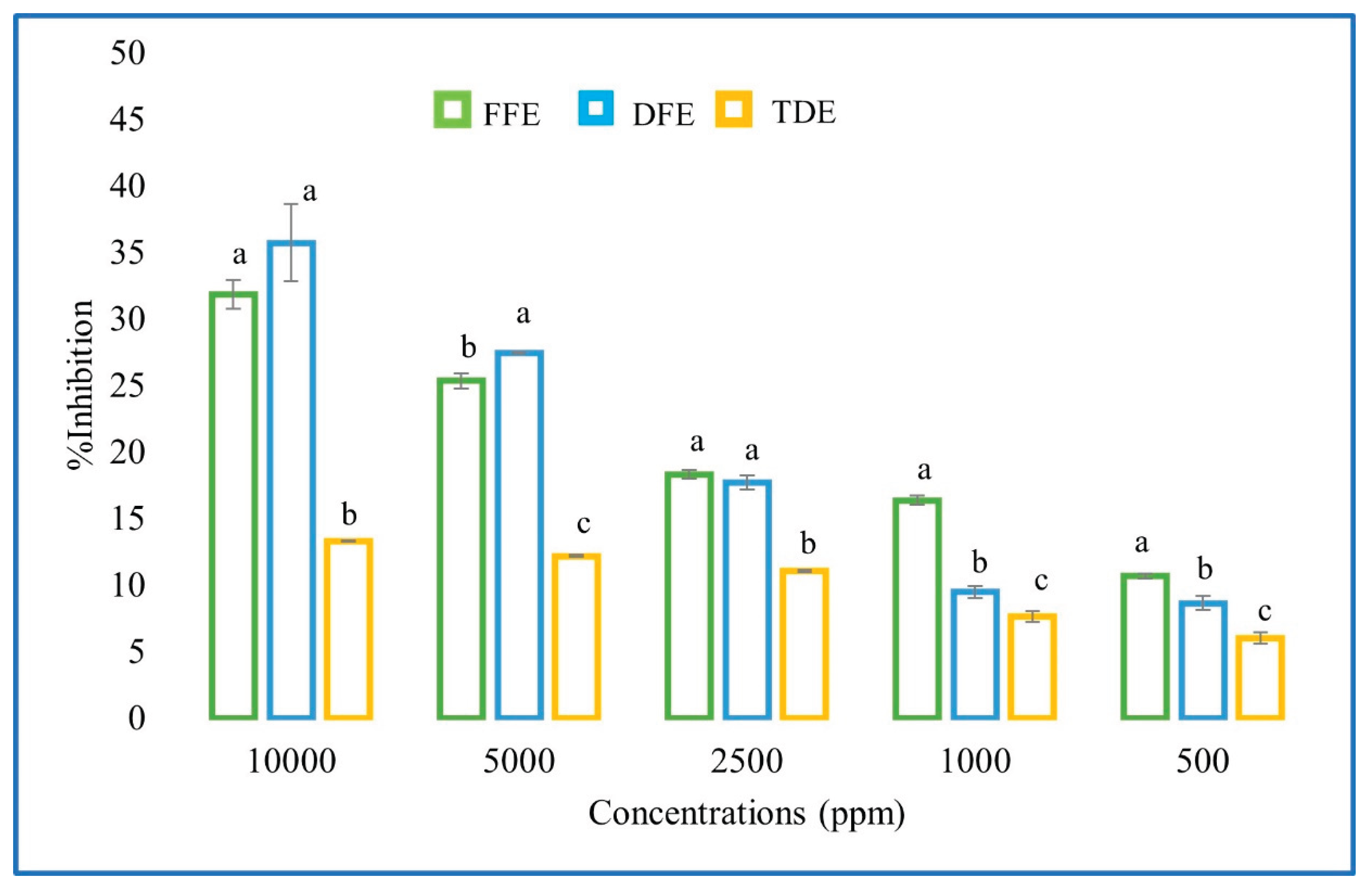

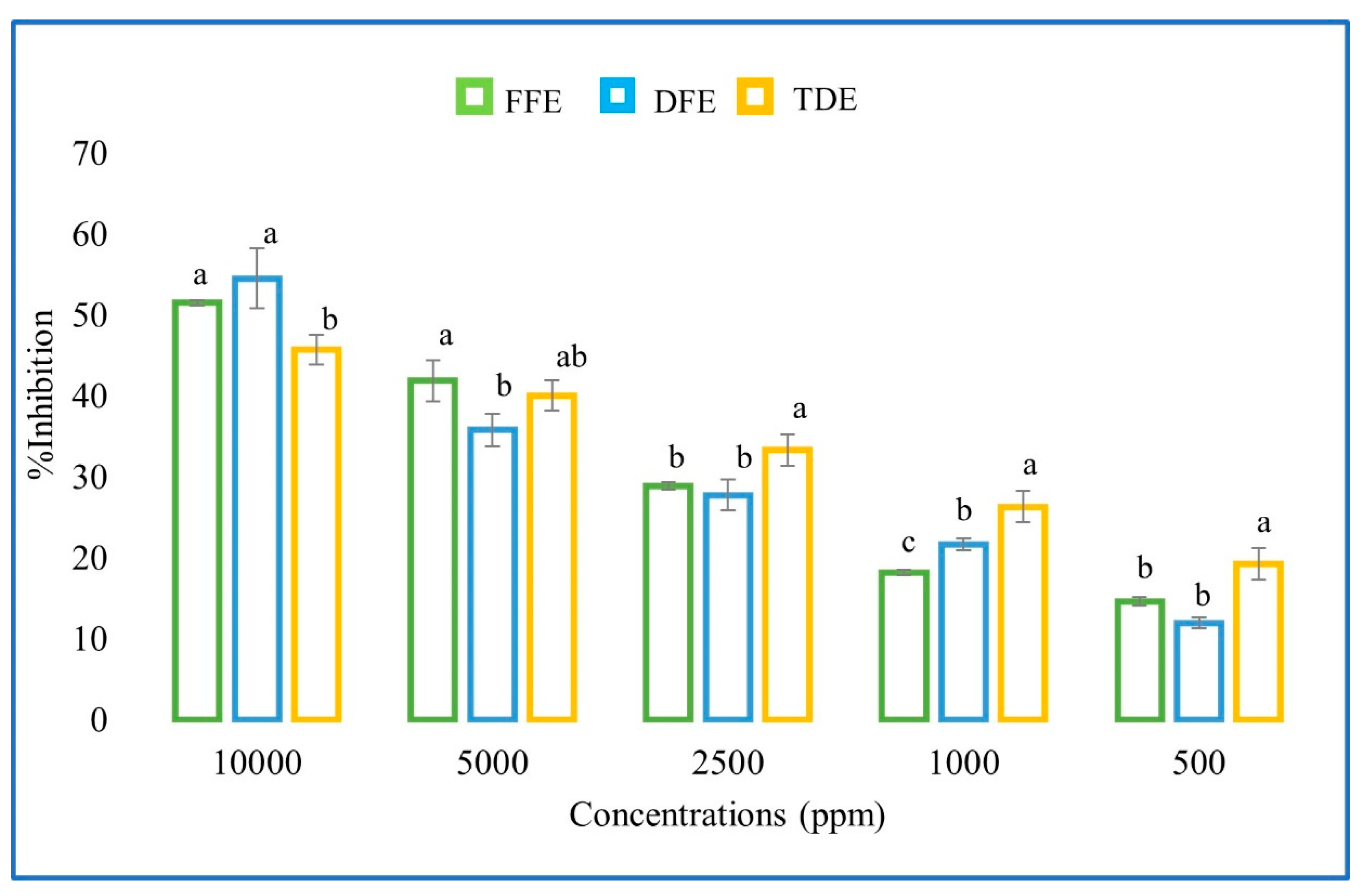

3.2. Antioxidant Activity

3.3. Antiproliferative Activity and Cytotoxicity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gómez, X.; Sanon, S.; Zambrano, K.; Asquel, S.; Bassantes, M.; Morales, J.E.; Otáñez, G.; Pomaquero, C.; Villarroel, S.; Zurita, A.; Calvache, C; Celi, K; Contreras, T; Corrales, D; Naciph, M.B.; Peña, P.; Caicedo; A Key points for the development of antioxidant cocktails to prevent cellular stress and damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) during manned space missions. npj Microgravity 2021, 7, 35. [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Berndt, C.; Jones, D.P. Oxidative Stress. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 715–748.

- Jiang, F.; Ding, Y.; Tian, Y.; Yang, R.; Quan, M.; Tong, Z.; Zhang, X.; Luo, D.; Chi, Z.; Liu, C. Hydrolyzed low-molecular-weight polysaccharide from Enteromorpha prolifera exhibits high anti-inflammatory activity and promotes wound healing. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 133, 112637. [CrossRef]

- Manikandan, R.; Anjali, R.; Beulaja, M.; Prabhu, N.M.; Koodalingam, A.; Saiprasad, G.; Chitra, P.; Arumugam, M. Synthesis, characterization, anti-proliferative and wound healing activities of silver nanoparticles synthesized from Caulerpa scalpelliformis. Process Biochem. 2019, 79, 135–141. [CrossRef]

- Said Nasser Al-Owamri, F.; Saleh Abdullah Al Sibay, L.; Hemadri Reddy, S.; Althaf Hussain, S.; Subba Reddy Gangireddygari, V. Phytochemical, Antioxidant, hair growth and wound healing property of Juniperus excelsa, Olea oleaster and Olea europaea. J. King Saud Univ. Sci 2023, 35, 102446. [CrossRef]

- Hang, C.; Sun, H.; Zhang, A.; Yan, G.; Lu, S.; Wang, X. Recent Developments in the Field of Antioxidant Activity on Natural Products. Aмурский Медицинский Журнaл 2015, 2, 44–48.

- Cano-Campos, M.C., Díaz-Camacho, S.P., Uribe-Beltran, M.J., López-Angulo, G., Montes-Avila, J., Paredes-López, O.; Delgado-Vargas, F. Bio-guided fractionation of the antimutagenic activity of methanolic extract from the fruit of Randia echinocarpa (Sessé et Mociño) against 1-nitropyrene. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44(9), 3087-3093. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, W. D., Ulloa, C., Pool, A., & Montiel, O. M. Flora de Nicaragua, 1st ed. St. Louis: Missouri Botanical Garden Press, 2001; pp.943.

- Gallardo-Casas, C.A.; Guevara-Balcázar, G.; Morales-Ramos, E.; Tadeo-Jiménez, Y.; Gutiérrez-Flores, O.; Jiménez-Sánchez, N.; Valadez-Omaña, M.T.; Valenzuela-Vargas, M.T.; Castillo-Hernández, M.C. Ethnobotanic study of Randia aculeata (Rubiaceae) in Jamapa, Veracruz, Mexico, and its anti-snake venom effects on mouse tissue. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 18 (3), 287–294. [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Trujillo, N.; Monribot-Villanueva, J.L.; Alvarado-Olivarez, M.; Luna-Solano, G.; Guerrero-Analco, J.A.; Jiménez-Fernández, M. Phenolic profile and antioxidative properties of pulp and seeds of Randia monantha Benth. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018., 124, 53-58. [CrossRef]

- Ojeda-Ayala, M.; Gaxiola-Camacho, S. M.; Delgado-Vargas, F. Phytochemical composition and biological activities of the plants of the genus Randia. Bot. Sci. 2024, 100(4), 779-796. [CrossRef]

- Mërtiri, I.; Coman, G.; Cotârlet, M.; Turturică, M.; Balan, N.; Râpeanu, G.; Stanciuc, N.; Mihalcea, L. Phytochemical Profile Screening and Selected Bioactivity of Myrtus communis Berries Extracts Obtained from Ultrasound-Assisted and Supercritical Fluid Extraction. Separations 2025, 12(1), 8. [CrossRef]

- Capataz-Tafur, J.; Orozco-Sánchez, F.; Vergara-Ruiz, R.; Hoyos-Sánchez, R Efecto antialimentario de los extractos de suspensiones celulares de Azadirachta indica sobre Spodoptera frugiperda JE Smith en condiciones de laboratorio. Rev. Fac. Nac. de Agr. Medellín. 2007, 60(1), 3703-3715.

- Bulugahapitiya, V.P.; Rathnaweera, T.N.; Manawadu, H.C. Phytochemical composition and antioxidant properties of Dialium ovoideum thwaites (Gal Siyambala) leaves. Int. J Min. Fruits, Med. and Arom. Plants. 2020, 6 (1), 13-19.

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdicphosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16(3), 144-158. [CrossRef]

- Zhishen, J.; Mengcheng, T.; Jianming, W. The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem. 1999, 64(4), 555–559. [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Lagunas, L.L.; Cruz-Gracida, M.; Barriada-Bernal, L.G.; Rodríguez-Méndez, L.I. Profile of phenolic acids, antioxidant activity and total phenolic compounds during blue corn tortilla processing and its bioaccessibility. J. Food Sci.Tech. 2020, 57(12), 4688–4696. [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT - Food Sci. Tech. 1995, 28(1), 25–30.

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26(9-10), 1231–1237. [CrossRef]

- González-Morales, L. D.; Moreno-Rodríguez, A.; Vázquez-Jiménez, L.K.; Delgado-Maldonado, T.; Juárez-Saldivar, A.; Ortiz-Pérez, E.; Rivera, G. Triose Phosphate Isomerase Structure-based virtual screening and in vitro biological activity of natural products as Leishmania Mexicana inhibitors. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15(8), 2046.

- Medina-Reyes, E.I.; Mancera-Rodríguez, M.A.; Delgado-Buenrostro, N.L.; Moreno-Rodríguez, A.; Bautista-Martínez, J.L.; Díaz-Velásquez, C.E.; Martínez-Alarcón, S.A.; Torrens, H.; Godínez-Rodríguez, M.A.; Terrazas-Valdés, L.I.; Chirino, Y.I.; Vaca Paniagua, F. Novel thiosemicarbazones induce high toxicity in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells (MCF7) and exacerbate cisplatin effectiveness in triple-negative breast (MDA-MB231) and lung adenocarcinoma (A549) cells. Invest. New Drugs. 2019, 38, 558-573. [CrossRef]

- Chaparro-Hernández, I.; Méndez-Lagunas, L.; Rodríguez-Ramírez, J.; Sandoval-Torres, S.; Aquino-González, L.; Barriada-Bernal, G. Spray Drying of Stevia Rebaudiana Bertoni Aqueous Extract: Effect on Polyphenolic Compounds. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2023, 98, 33-38.

- Sepúlveda, C.T.; Zapata, J.E. Efecto de la Temperatura, el pH y el Contenido en Sólidos sobre los Compuestos Fenólicos y la Actividad Antioxidante del Extracto de Bixa orellana L. Inf. Tec. 2019, 30(5), 57-66.

- Lesage-Meessen, L.; Bou, M.; Sigoillot, J.C.; Faulds, C.B.; Lomascolo, A. Essential oils and distilled straws of lavender and lavandin: a review of current use and potential application in white biotechnology. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99(8), 3375–3385. [CrossRef]

- Ozer, M.S.; Kirkanb, B.; Sarikurkcuc, C.; Cengizd, M.; Ceylane, O.; Atılgand, N.; Tepef, B. Onosma heterophyllum: phenolic composition, enzyme inhibitory and antioxidant activities. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 111, 179–184.

- Martínez-Ceja, A.; Romero-Estrada, A.; Columba-Palomares, M.C.; Hurtado-Díaz, I.; Alvarez, L.; Teta-Talixtacta, R.; Bernabé-Antonio, A. Anti-inflammatory, antibacterial and antioxidant activity of leaf and cell cultures extracts of Randia aculeata L. and its chemical components by GC-MS. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 144, 206-218. [CrossRef]

- McGaw, L.J.; Elgorashi, E.E.; Eloff, J.N. Cytotoxicity of African medicinal plants against normal animal and human cells. In Toxicological survey of African medicinal plants,1st ed.; Kuete,V. Elsevier: Jamestown Road, London, 2014, pp. 181-233.

- Bye, R.; Linares, E.; Mata, R.; Albor C.; Casteñeda, P.C.; Delgado, G. Ethnobotanical and phytochemical investigation of Randia echinocarpa (Rubiaceae). An. Inst. Biol. Serie Bot. 1991, 62, 87-106.

- Charoensin, S. (2014). Antioxidant and anticancer activities of Moringa oleifera leaves. J. Med. Plants Res, 2014, 8(7), 318-325.

- Sahlabgi, A.; Lupuliasa, D.; Stoicescu, I.; Vlaia, L.L.; Licu, M.; Popescu, A.; Mititelu, M. Determination of the Phytochemical Profile and Antioxidant Activity of Some Alcoholic Extracts of Levisticum officinale with Pharmaceutical and Cosmetic Applications. Separations, 2025, 12(4), 79.

- Do, Q.D.; Angkawijaya, A.E.; Tran-Nguyen, P.L.; Huynh, L.H.; Soetaredjo, F.E.; Ismadji, S.; Ju, Y.H. Effect of extraction solvent on total phenol content, total flavonoid content, and antioxidant activity of Limnophila aromatica. J. Food Drug Anal. 2014, 22, 296–302. [CrossRef]

- Rice-Evans, C.A.; Miller, NJ.; Paganga, G. (1996). Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free Radic Biol. Med. 1996, 20(7), 933-956.

- Budryn, G.; Zaczyńska, D.; Oracz, J. (2016). Effect of addition of green coffee extract and nanoencapsulated chlorogenic acids on aroma of different food products. Lwt, 2016, 73, 197-204.

- Zhuang, X., Shi, W., Shen, T., Cheng, X., Wan, Q., Fan, M., & Hu, D. Research Updates and Advances on Flavonoids Derived from Dandelion and Their Antioxidant Activities. Antioxidants, 2024, 13(12), 1449. [CrossRef]

- Krishnaiah, D.; Sarbatly, R.; Nithyanandam, R. A review of the antioxidant potential of medicinal plant species. Food Bioprod. Process. 2011, 89(3), 217-233. [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Trujillo, N.; Tapia-Hernández, F.E.; Alvarado-Olivarez, M.; Beristain-Guevara, C.I.; Pascual-Pineda, L.A.; Jiménez-Fernández, M. Antibacterial activity and acute toxicity study of standardized aqueous extract of Randia monantha Benth fruit. Biotecnia, 2022, 24(1), 38-45. [CrossRef]

- Floegel, A.; Kim, D.O.; Chung, S.J.; Koo, S.I.; Chun, O.K. (). Comparison of ABTS/DPPH assays to measure antioxidant capacity in popular antioxidant-rich US foods. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24(7), 1043-1048.

- Pappis, L.; Prates-Ramos, A.; Fontana, T.; Geraldo-Sangoi, G.; Castro-Dornelles, R.; Bolssoni-Dolwitsch, C.; Rorato-Sagrillo, M.; Cadoná, FC.; Kolinski-Machado, A.; De Freitas, Bauermann, L. Randia ferox (Cham & Schltdl) DC: phytochemical composition, in vitro cyto-and genotoxicity analyses. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 4, 1-7.

- Saklani, A.; Kutty S.K. Plant-derived compounds in clinical trials. Drug Discovery Today, 2008, 13(3-4), 161–171.

- Solowey, E.; Lichtenstein, M.; Sallon, S.; Paavilainen, H.; Solowey, E., & Lorberboum-Galski, H. (2014). Evaluating medicinal plants for anticancer activity. Sci. World J. 2014, 1, 721402.

- Subramani, C.; Sharma, G.; Chaira, T.; Barman, T.K. High content screening strategies for large-scale compound libraries with a focus on high-containment viruses. Antivir. Res. 2024, 221, 105764. [CrossRef]

| Family | Fresh fruit | Dried fruit | Traditional drink |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids | - | - | - |

| Saponins | ++ | ++ | + |

| Sterols and triterpenes | - | - | - |

| Phenols | ++ | ++ | + |

| Flavonoids | + | + | ++ |

| Extract | TPC (mg GAE/g extract) |

TFC (mg QE/g extract) |

|---|---|---|

| Fresh | 47.22 ± 0.96 A | 27.08 ± 1.36 B |

| Dry | 50.27 ± 0.14 A | 35.53 ± 2.20 A |

| Traditional drink | 38.583 ± 2.677B | 18.660 ± 1.696C |

| Compound (mg/gdb) | Fresh | Dry | Traditional drink |

| Caffeic acid | 1.05 ± 0.01 | nd | nd |

| Hydroxybenzoic acid | 5.34 ± 0.1 | nd | nd |

| Ferulic acid | 2.30 ± 0.03 A | 1.94 ± 0.05 B | nd |

| Cumaric acid | 1.54 ± 0.05 | nd | nd |

| Kaempferol | 137.55 ± 0.16 A | 42.10 ± 0.20 B | nd |

| Vanillic acid | nd | 7.51 ± 0.33 | nd |

| Extract | DPPH (%) | IC50 (mg/mL) | ABTS (%) | IC50 (mg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | 31.8 ± 1.85 A | 18.29 ± 0.8 A | 51.54 ± 2.12 A | 8.70 ± 0.14 A |

| Dry | 35.7 ± 1.92 A | 14.22 ± 1.35 A | 54.54 ± 1.87 A | 8.68 ± 0.62 A |

| Traditional drink | 14.6 ± 1.92 B | 61.933 ± 1.042 B | 45.54 ± 1.92 B | 61.933 ± 1.042 B |

| Extract | Cytotoxicity a CC50 (µg/mL) |

Antiproliferative Activityb IC50 (µg/mL) |

SIc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh fruit | >100 | >100 | 1 |

| Dried fruit | >100 | 25.44± 0.16 | 3.92 |

| Traditional drink | 29.99± 8.45 | 100.50 ± 6.54 | 0.29 |

| Control (cisplatin) | 2.22 ± 0.21 | 7.52 ± 0.41 | 0.29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).