Submitted:

07 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

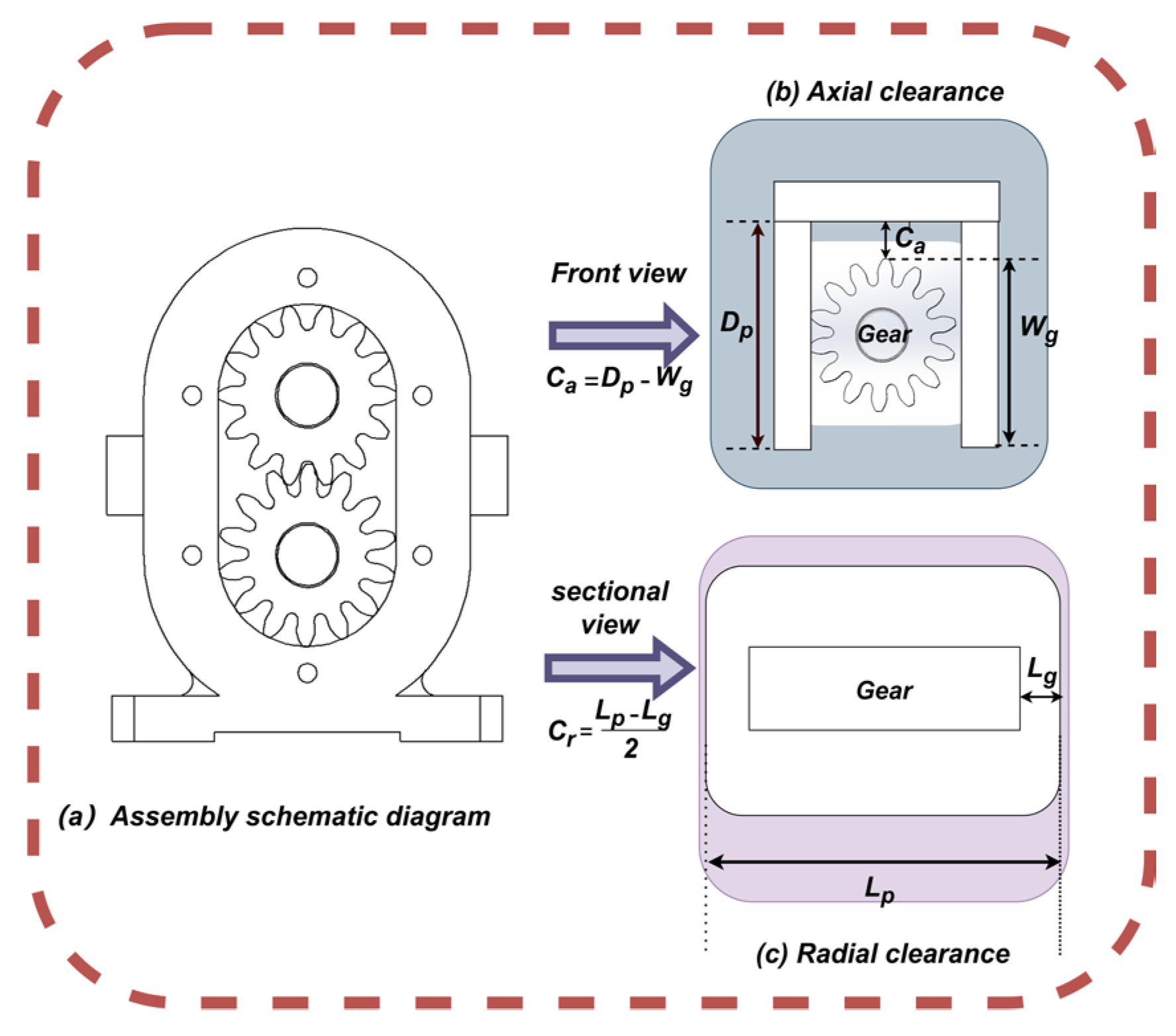

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Goals of Dimension Chain Analysis and Optimization

2.2. Making Decisions with Several Objectives

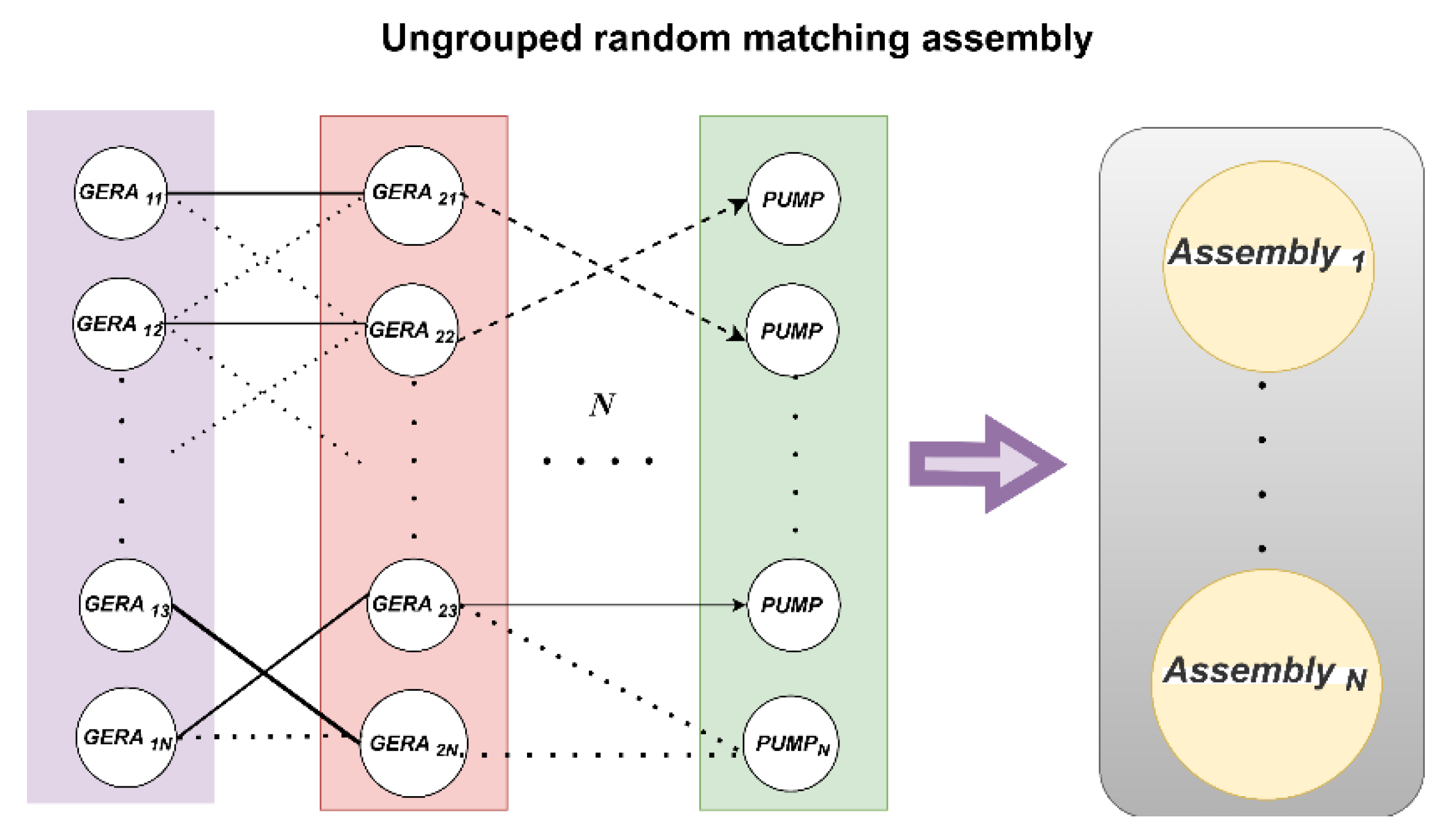

2.2.1. Maximizing assembly Success Rate (Quantity)

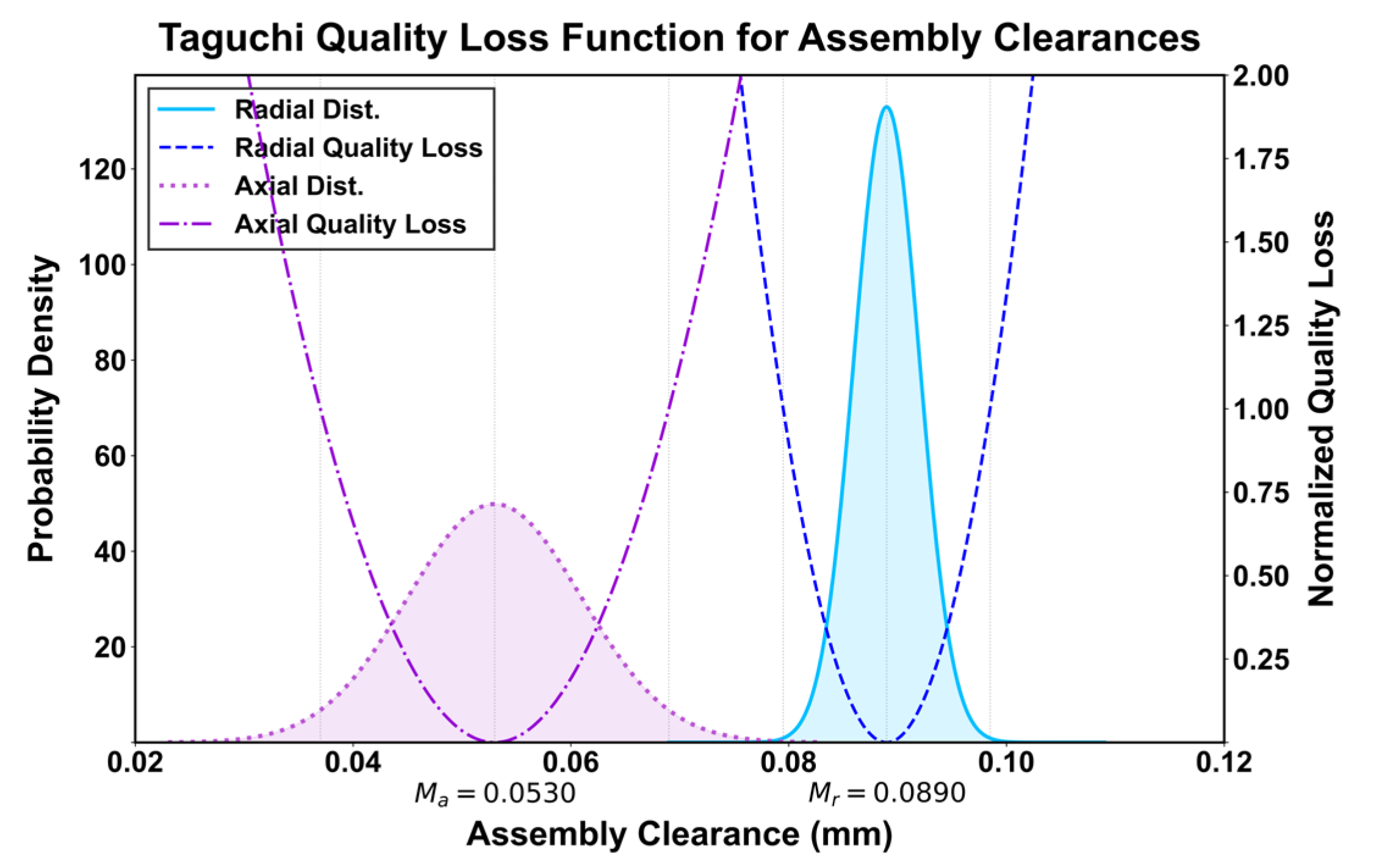

2.2.2. Maximizing Assembly Accuracy (Quality)

2.2.3. Balanced Decision-Making TOPSIS

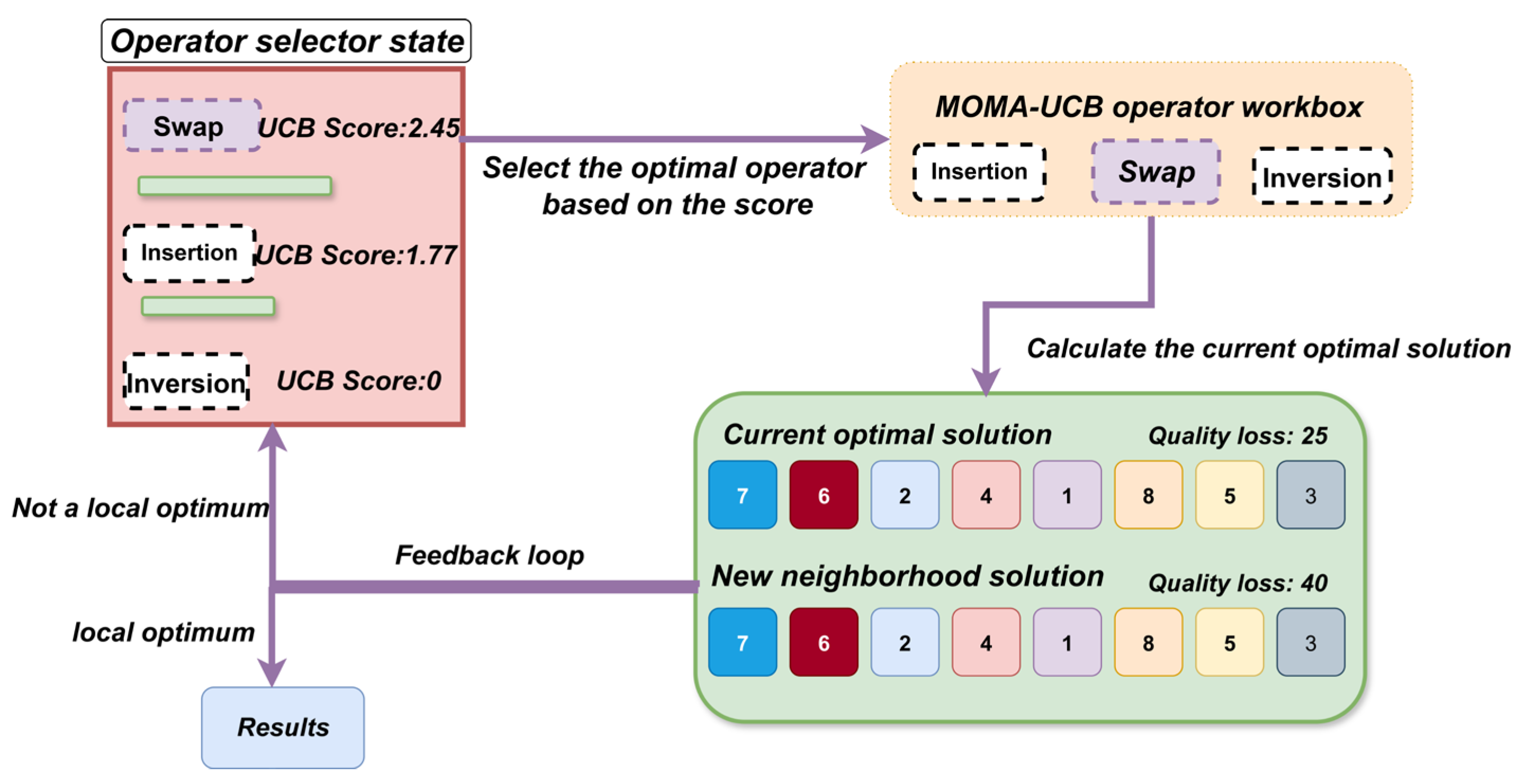

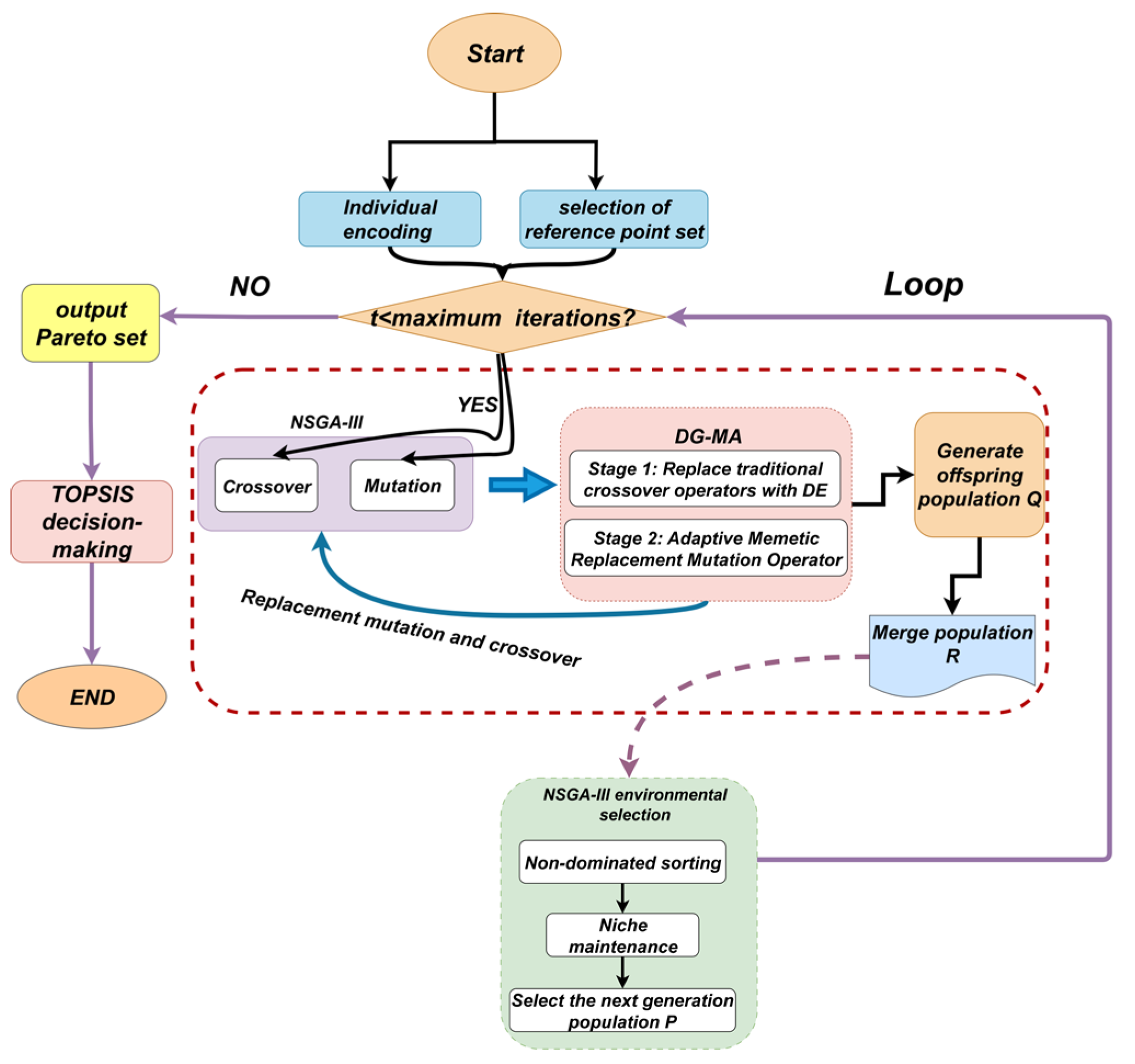

2.3. DG-MA Algorithm Design

2.3.1. Fundamental Structure: NSGA-III

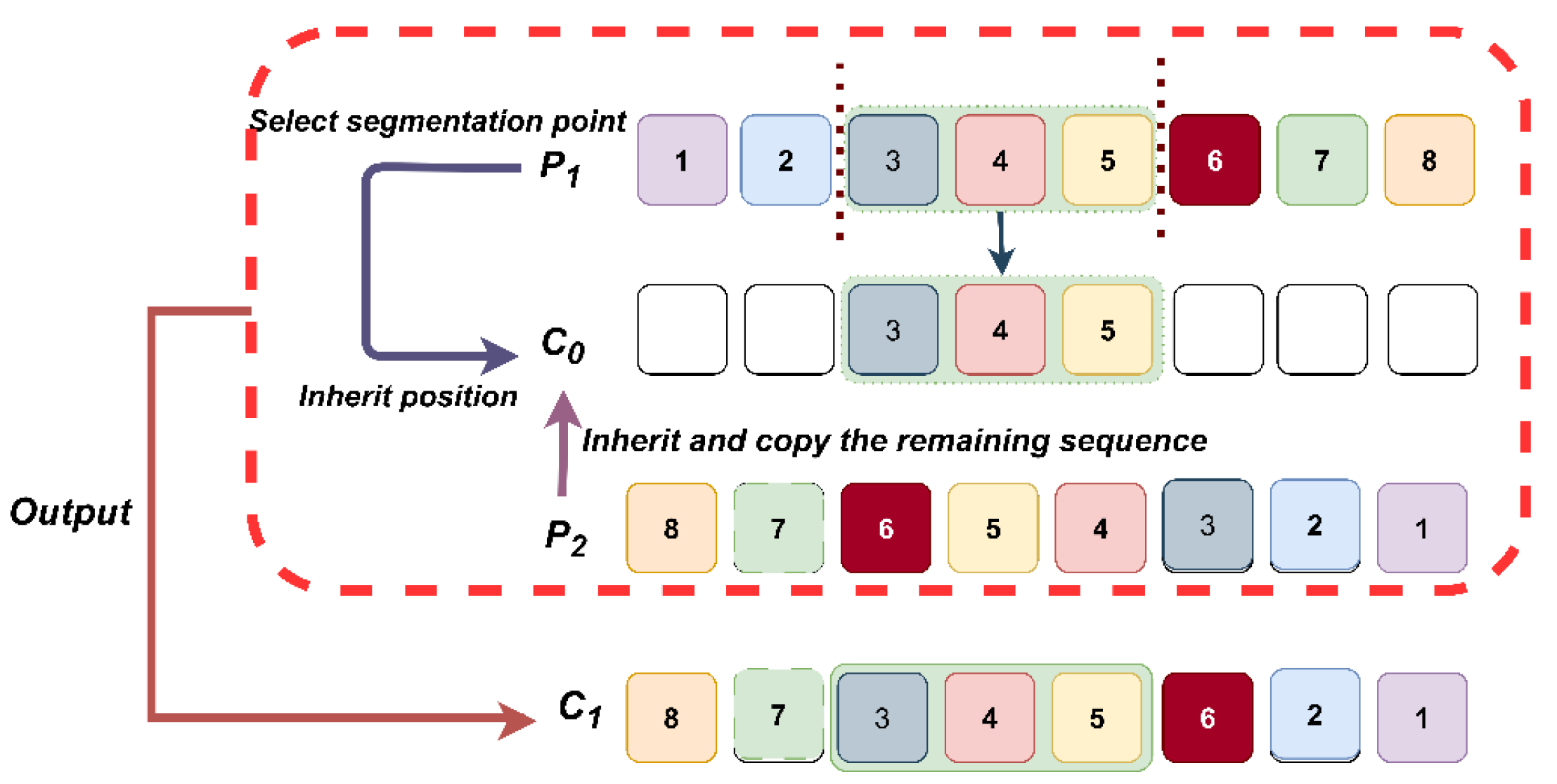

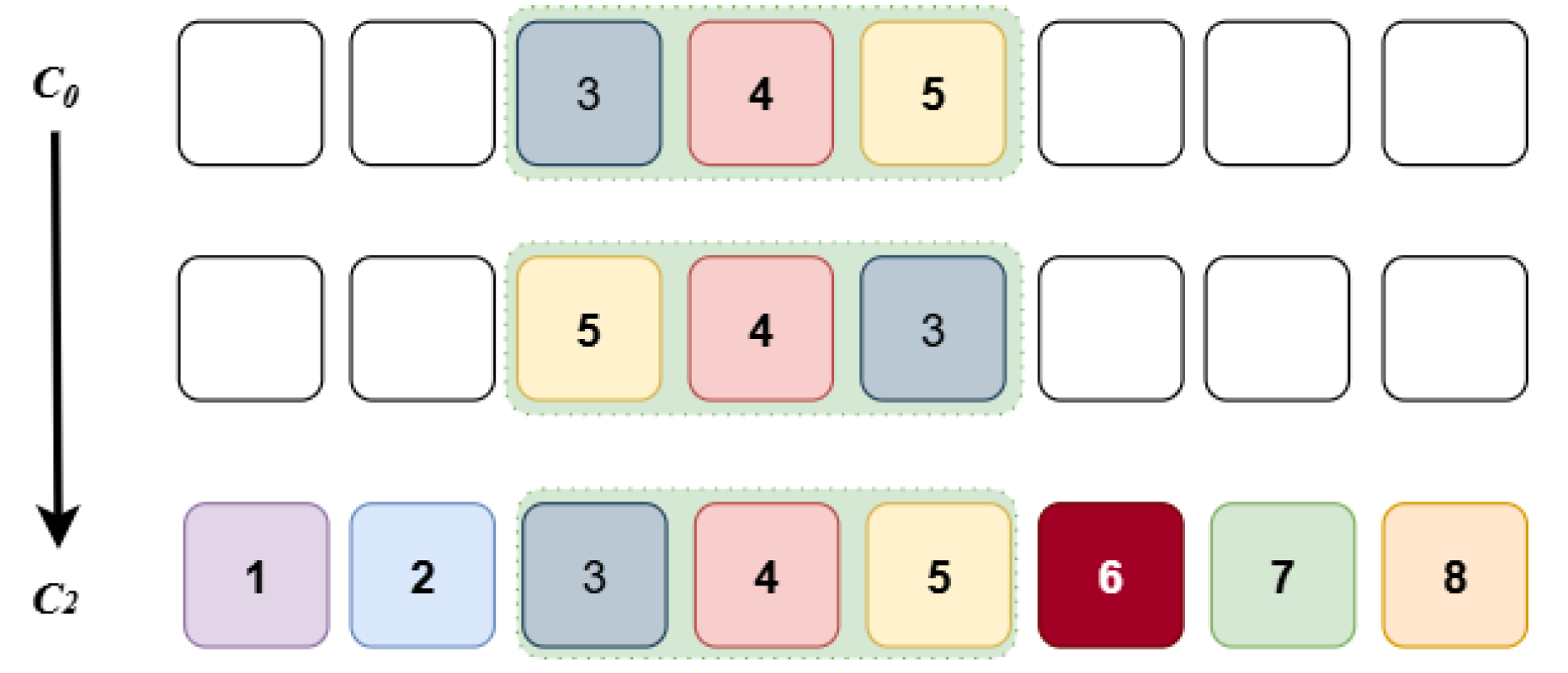

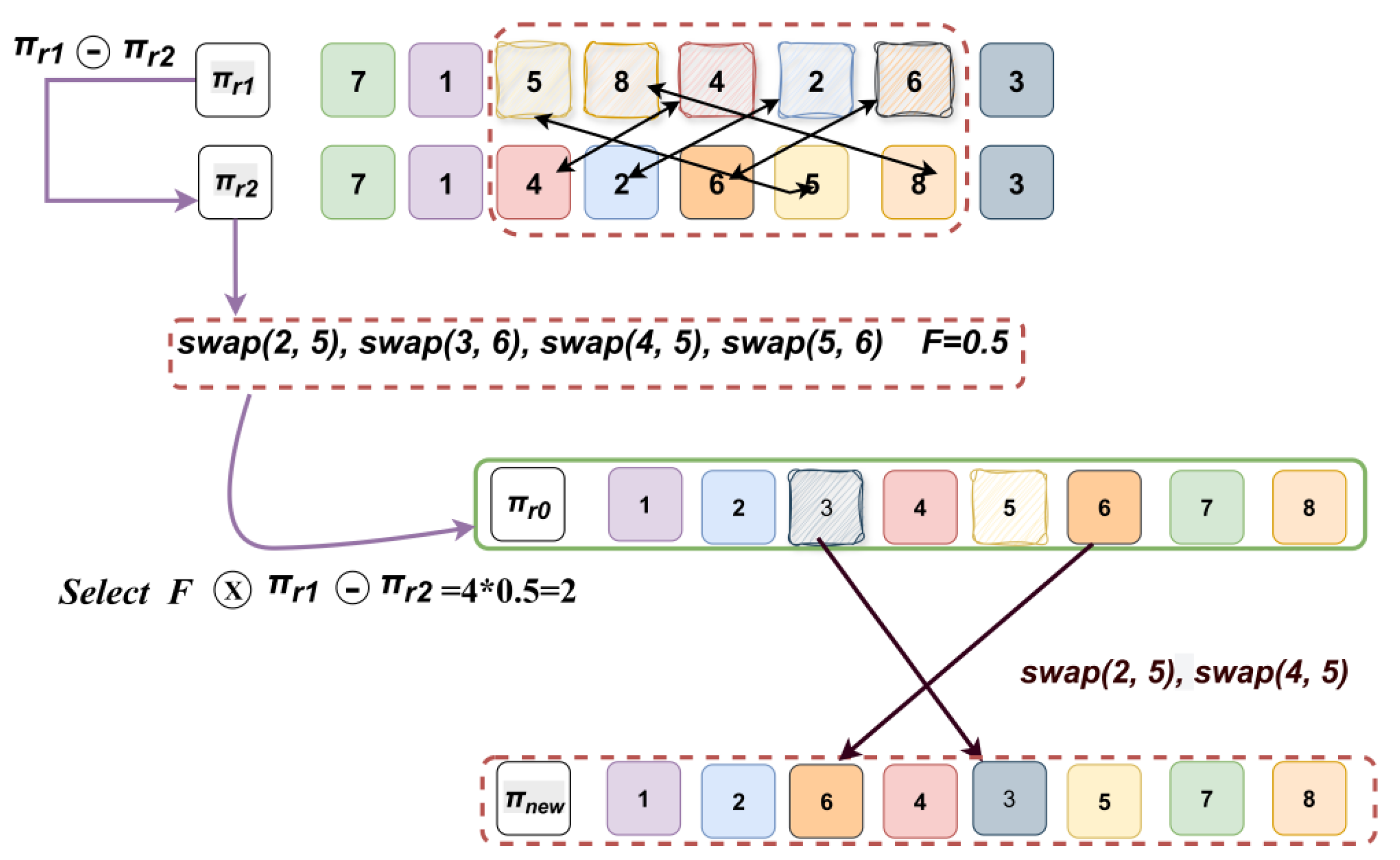

2.3.2. The Design Process of DG-MA

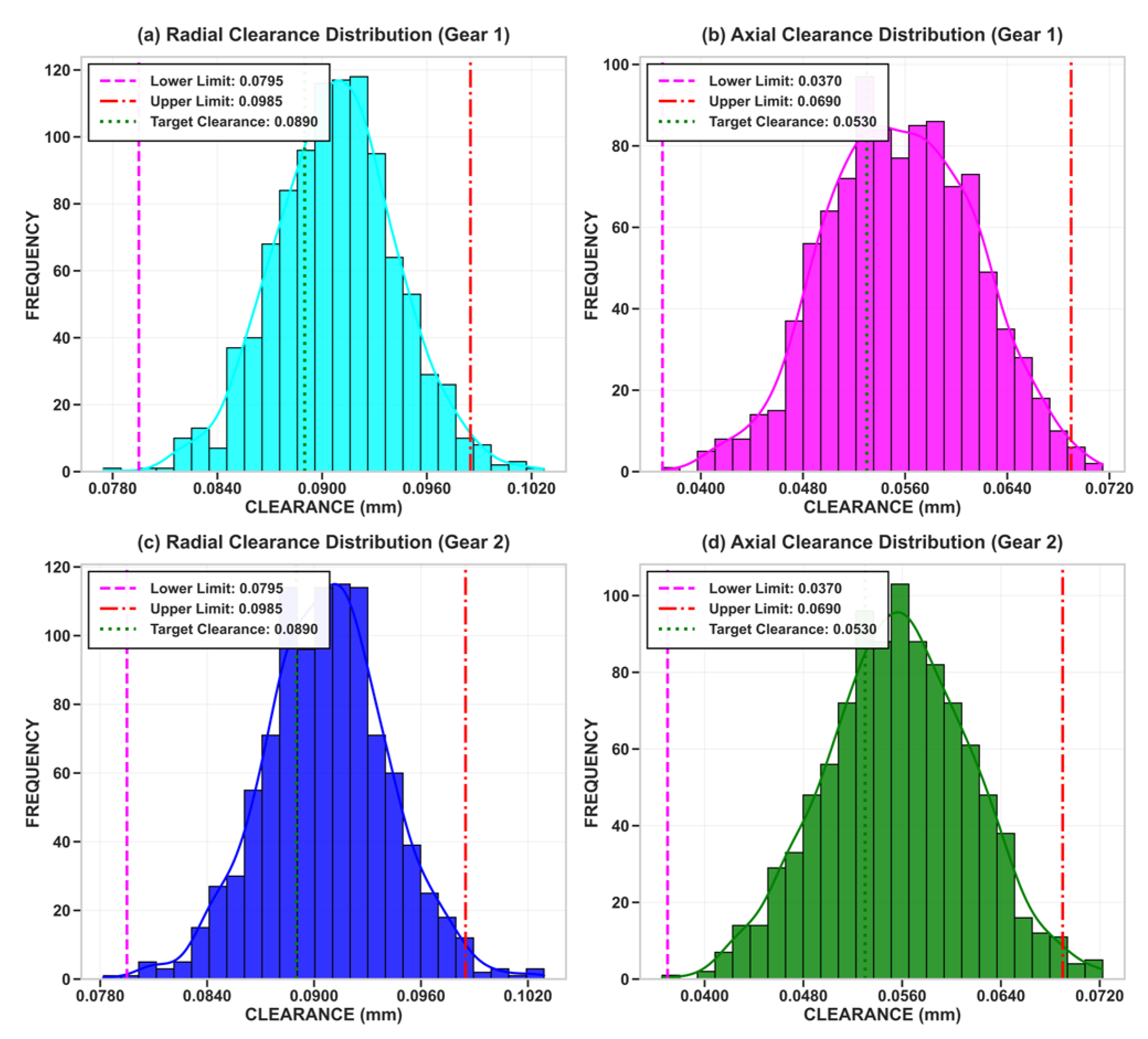

3. Results

3.1. Results Data

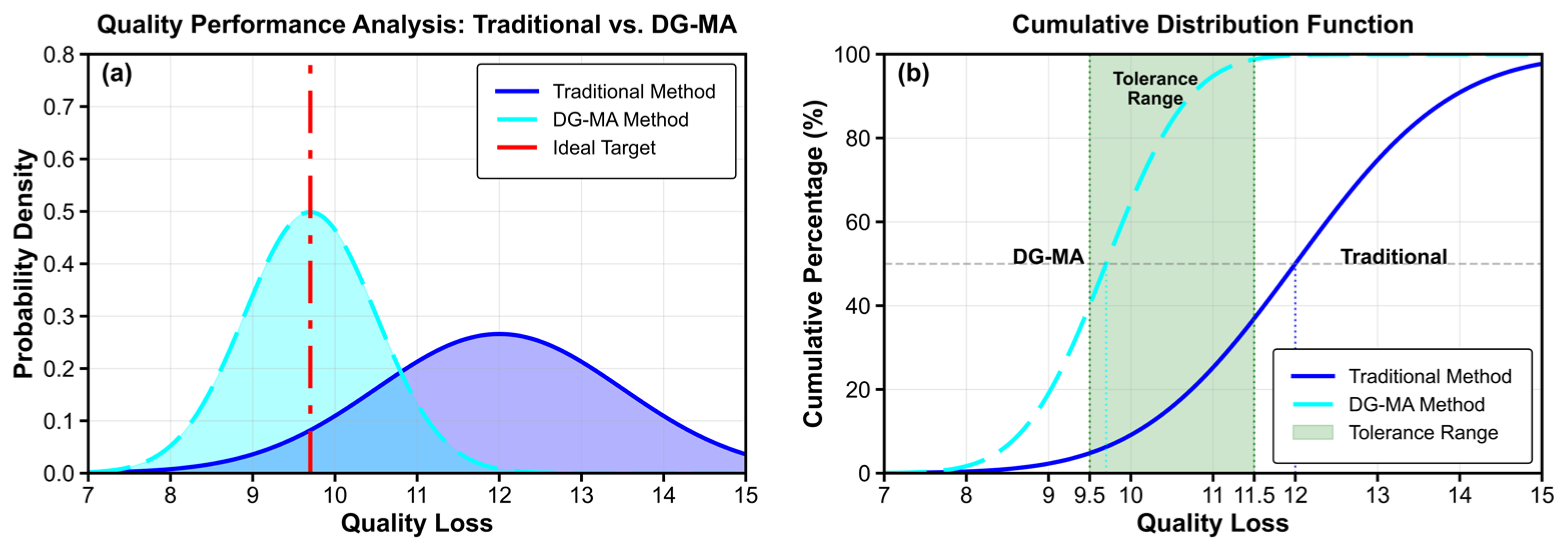

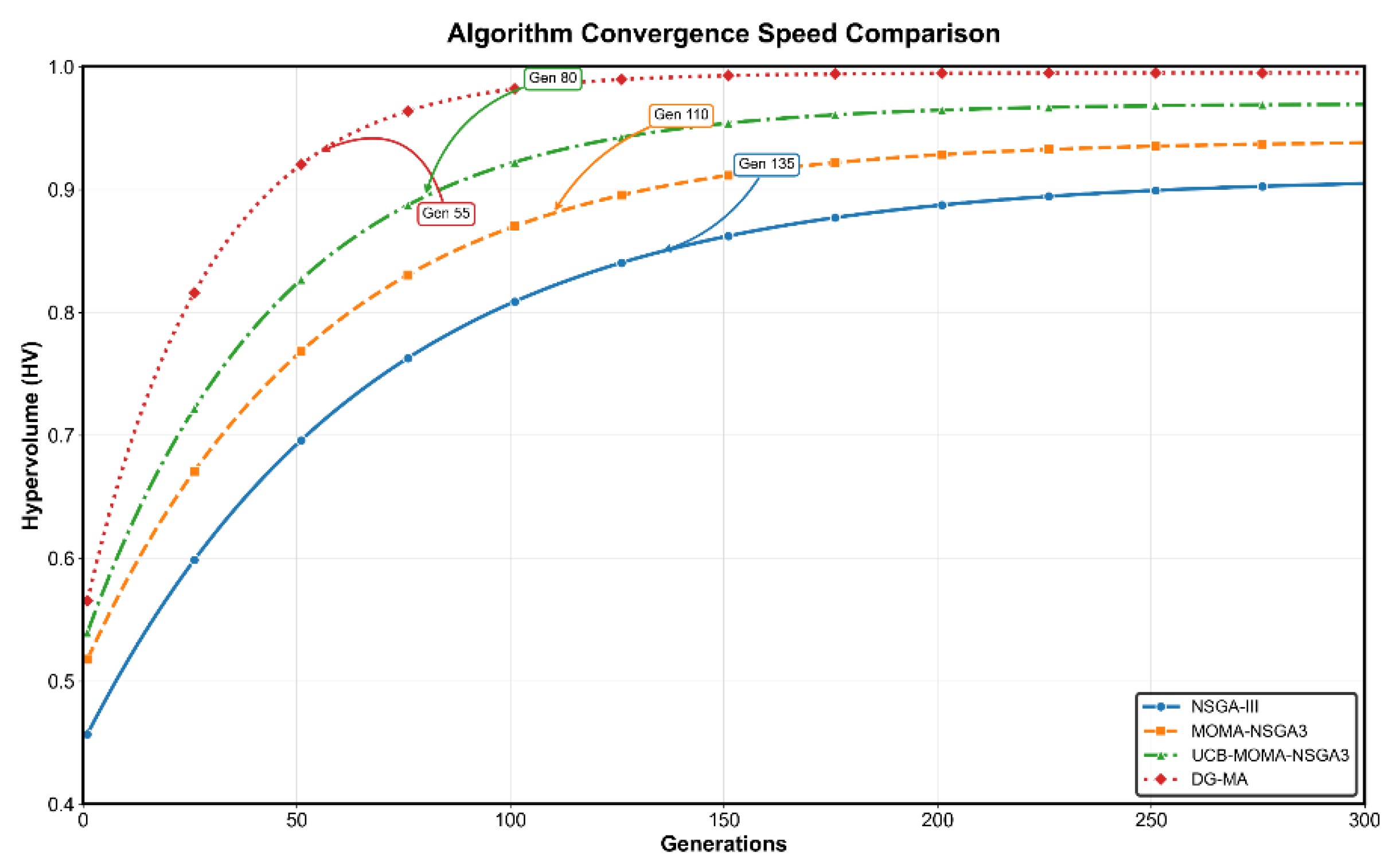

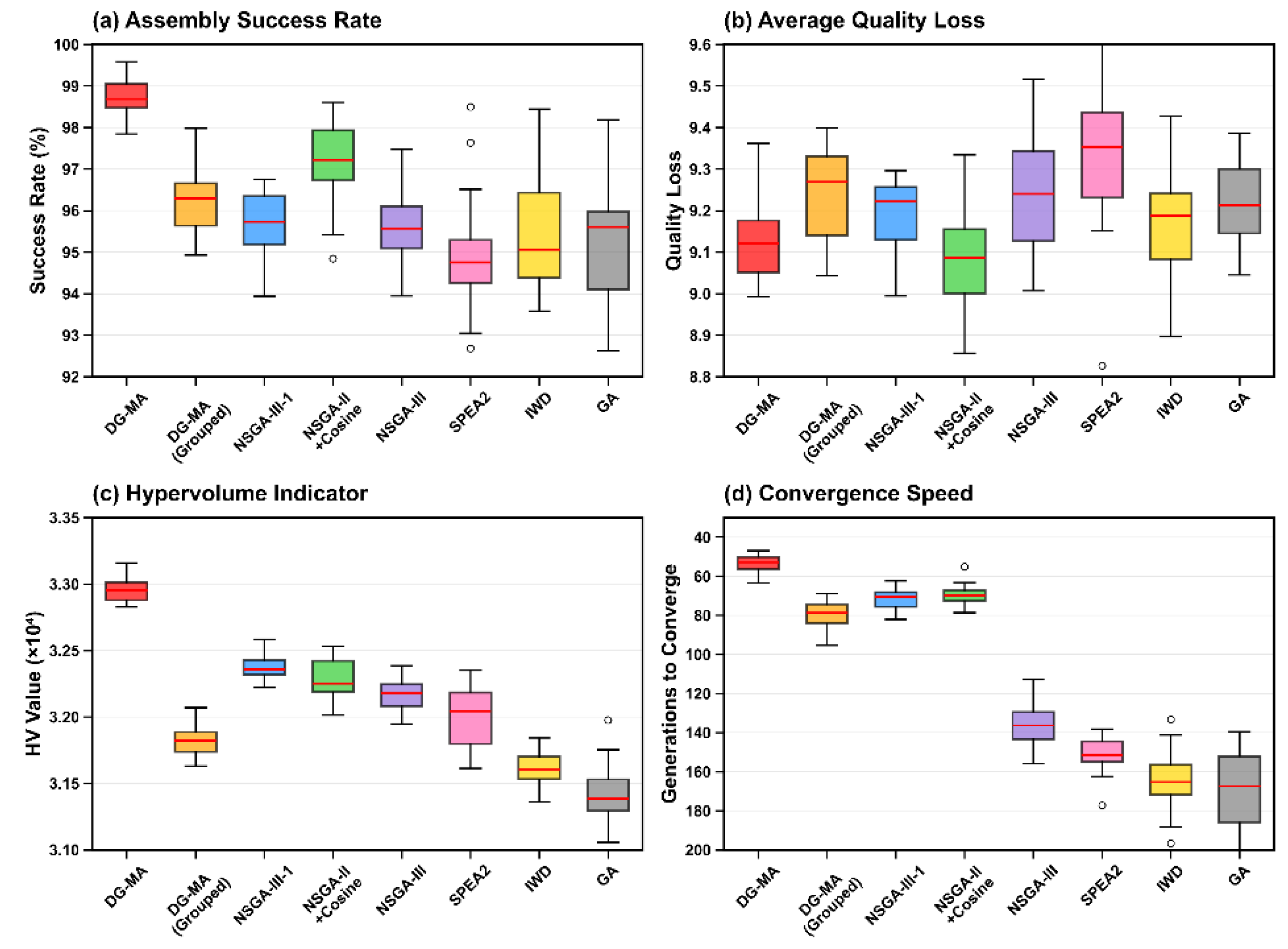

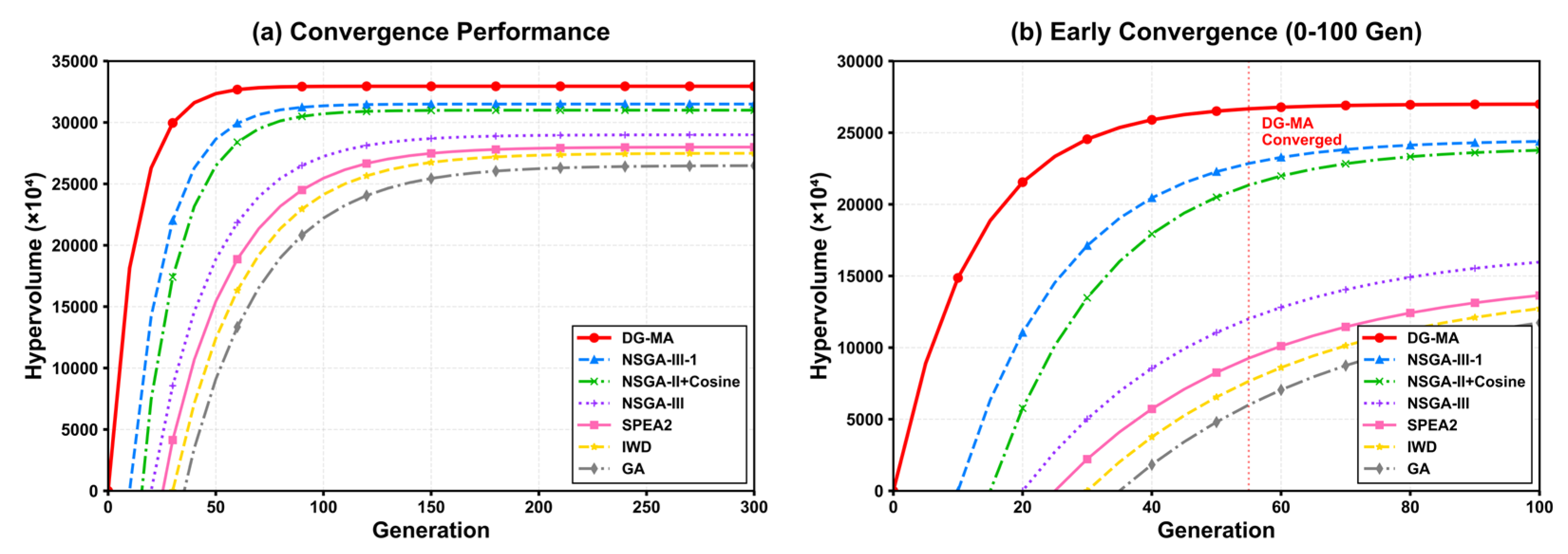

3.2. Data Comparison Analysis

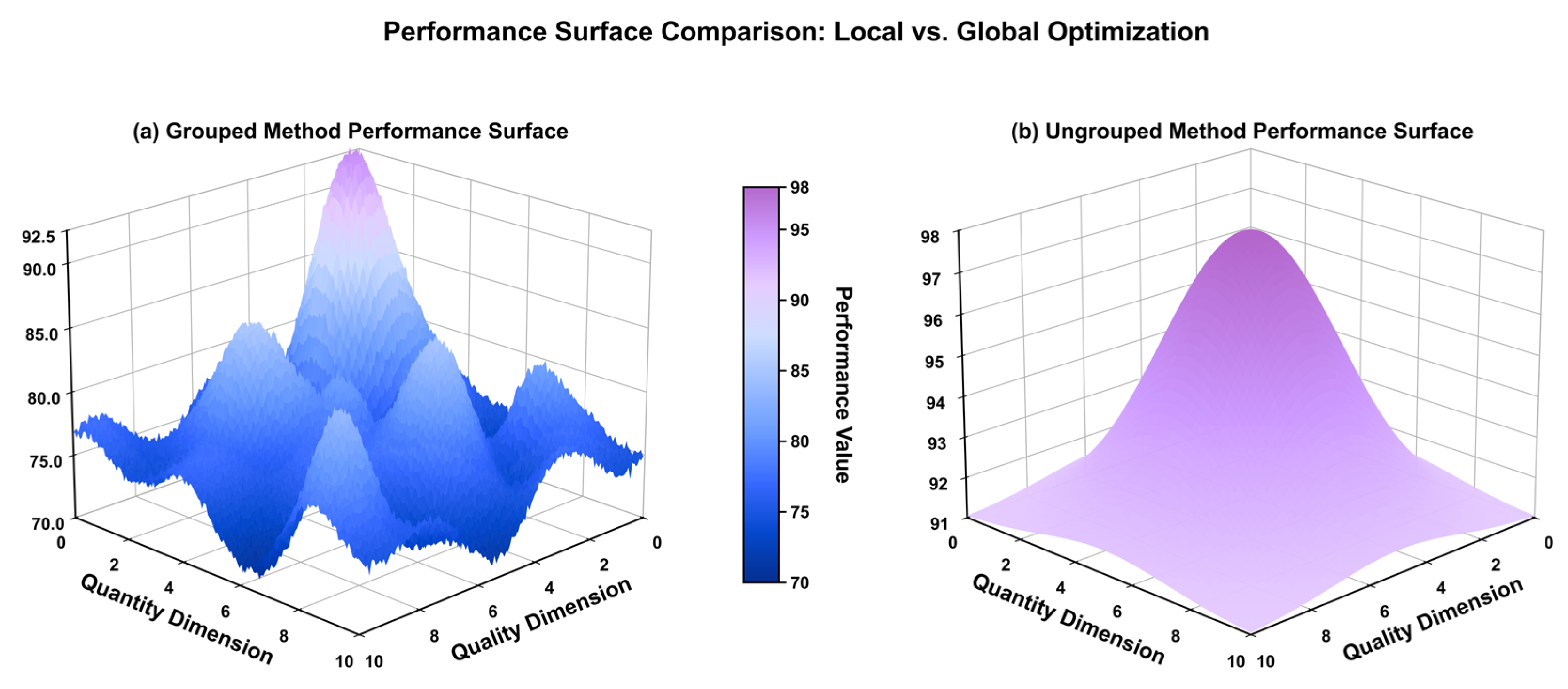

3.2.1. Comparison of Grouping, Non-Grouping, and Traditional Selection Assembly Methods

3.2.2. DG-MA vs. NSGA-III

3.2.3. DG-MA vs. Academic Algorithms

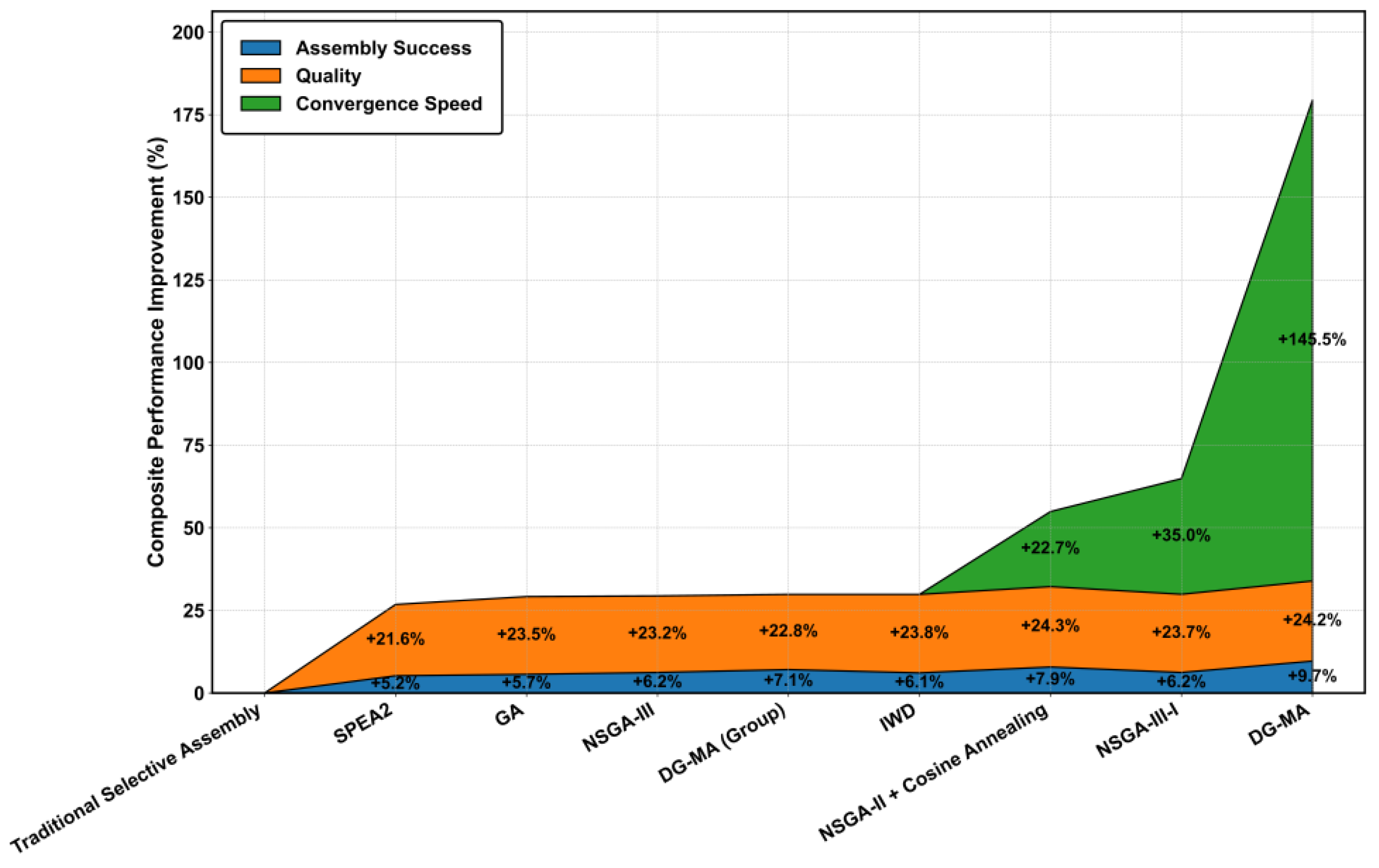

3.3. Assembly Index Comparison Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Advantages of Ungrouped Matching Assembly

4.2. Advantages of DG-MA

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Algorithm | Evolutionary generation | Crossover operator | Mutation operator | Core parameters | |

| Algorithm in this paper | DG-MA | 300 | DE, F = 0.5 | MOMA-UCB, Pls = 0.6, Nls = 25 | Number of partitions = 12, UCB exploration c = 2.0 |

| DG-MA (Grouped) | 300 | DE, F = 0.5 | MOMA-UCB, Pls = 0.6, Nls = 25 | Number of partitions = 12, UCB exploration c = 2.0 | |

| Academic algorithm | NSGA-III-I [19] | 300 | Order crossover, Pc = 0.9 | Inversion mutation, Pm = 0.2 | Number of partitions = 12 |

| NSGA-II + CA [34] | 300 | SBX = 20 | Polynomial mutation, η = 20, Pm = 0.1 | Cosine annealing learn rate | |

| NSGA-III [28] | 300 | Order crossover, Pc = 0.9 | Inversion mutation, Pm = 0.2 | Number of partitions = 12 | |

| SPEA2 [35] | 300 | Order crossover, Pc = 0.9 | Inversion mutation, Pm = 0.2 | Archive size = 100 | |

| IWD [36] | 300 | \ | \ | Initial soil amount = 10,000 | |

| GA [16] | 300 | Order crossover, Pc = 0.9 | Inversion mutation, Pm = 0.2 | Elite retention strategy |

| Pump | DG-MA | DG-MA Grouped | NSGA-III | NSGA-III-I | NSGA-II + CA |

| Pump_258 | Gear_1024 Gear_1833 |

Gear_1022 Gear_1830 |

Gear_755 Gear_1201 |

Gear_910 Gear_1345 |

Gear_950 Gear_1300 |

| Pump_771 | Gear_64 Gear_942 |

Gear_66 Gear_940 |

Gear_132 Gear_1688 |

Gear_215 Gear_1500 |

Gear_200 Gear_1550 |

| Pump_103 | Gear_1509 Gear_33 |

Gear_1511 Gear_35 |

Gear_888 Gear_1902 |

Gear_1400 Gear_102 |

Gear_1450 Gear_80 |

| Pump_520 | Gear_477 Gear_1126 |

Gear_475 Gear_1128 |

Gear_205 Gear_1437 |

Gear_301 Gear_1301 |

Gear_350 Gear_1250 |

| Pump_814 | Gear_1731 Gear_608 |

Gear_1729 Gear_610 |

Gear_512 Gear_1099 |

Gear_1650 Gear_700 |

Gear_1700 Gear_335 |

| Pump_333 | Gear_811 Gear_1620 |

Gear_813 Gear_1618 |

Gear_45 Gear_1730 |

Gear_800 Gear_1600 |

Gear_603 Gear_1632 |

| Pump_901 | Gear_22 Gear_1455 |

Gear_100 Gear_1405 |

Gear_789 Gear_1800 |

Gear_20 Gear_1457 |

Gear_50 Gear_63 |

| Pump_654 | Gear_500 Gear_1234 |

Gear_502 Gear_1232 |

Gear_111 Gear_1111 |

Gear_550 Gear_1200 |

Gear_1210 Gear_1870 |

| Pump_488 | Gear_197 Gear_1890 |

Gear_197 Gear_1890 |

Gear_666 Gear_1555 |

Gear_250 Gear_1850 |

Gear_1340 Gear_573 |

| Pump_211 | Gear_1333 Gear_777 |

Gear_779 Gear_1331 |

Gear_321 Gear_1654 |

Gear_750 Gear_1350 |

Gear_688 Gear_1204 |

References

- Mansoor, E.M. Selective assembly—Its analysis and applications. Int. J. Prod. Res. 1961, 1, 13–24. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, D.; He, F.; Tong, Y. Modelling and optimization for a selective assembly process of parts with non-normal distribution. Int. J. Simul. Model 2018, 17, 133–146. [CrossRef]

- Kannan, S.; Jayabalan, V. A new grouping method to minimize surplus parts in selective assembly for complex assemblies. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2001, 39, 1851–1863. [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Fei, J.-F. An approach to minimizing surplus parts in selective assembly with genetic algorithm. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2015, 229, 508–520. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, L. Determining the number of groups in selective assembly for remanufacturing engine. Procedia Eng. 2017, 174, 815–819. [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, L.; Mahalingam, S.K.; Kandasamy, J.; Gurusamy, S. A novel approach in selective assembly with an arbitrary distribution to minimize clearance variation using evolutionary algorithms: A comparative study. J. Intell. Manuf. 2022, 33, 1337–1354. [CrossRef]

- Aderiani, A.R.; Wärmefjord, K.; Söderberg, R. A multistage approach to the selective assembly of components without dimensional distribution assumptions. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2018, 140, 071015. [CrossRef]

- Babu, J.R.; Asha, A. Tolerance modelling in selective assembly for minimizing linear assembly tolerance variation and assembly cost by using Taguchi and AIS algorithm. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2014, 75, 869–881. [CrossRef]

- Asha, A.; Babu, J.R. Comparison of clearance variation using selective assembly and metaheuristic approach. Int. J. Latest Trends Eng. Technol. 2017, 8, 148–155. [CrossRef]

- Mahalingam, S.K.; Nagarajan, L.; Velu, C.; Dharmaraj, V.K.; Salunkhe, S.; Hussein, H.M.A. An evolutionary algorithmic approach for improving the success rate of selective assembly through a novel EAUB method. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8797. [CrossRef]

- Prasath, N.E.; Benham, A.; Mathalaisundaram, C.; Sivakumar, M. A new grouping method in selective assembly for minimizing clearance variation using TLBO. Appl. Math. Inf. Sci. 2019, 13, 687–697. [CrossRef]

- Jeevanantham, A.K.; Chaitanya, S.V.; Rajeshkannan, A. Tolerance analysis in selective assembly of multiple component features to control assembly variation using matrix model and genetic algorithm. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2019, 20, 1801–1815. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Du, Y.; Chen, F. A hybrid strategy improved SPEA2 algorithm for multi-objective web service composition. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4157. [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, X.; Zhang, Z. Optimization of selective assembly for shafts and holes based on relative entropy and dynamic programming. Entropy 2020, 22, 1211. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, M.; Li, J. A selective assembly method for tandem structure component of product based on the Kuhn-Munkres algorithm. J. Ind. Manag. Optim. 2025, 21, 2596–2624. [CrossRef]

- Raj, M.V.; Sankar, S.S.; Ponnambalam, S.G. Genetic algorithm to optimize manufacturing system efficiency in batch selective assembly. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2011, 57, 795–810. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, C.; You, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liang, S.Y. An effective selective assembly model for spinning shells based on the improved genetic simulated annealing algorithm (IGSAA). Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 119, 4813–4827. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Nan, Z.; Qiu, C.; Tan, J.; Zhou, J.; Yao, Y. A discrete fireworks optimization algorithm to optimize multi-matching selective assembly problem with non-normal dimensional distribution. Assem. Autom. 2019, 39, 323–344. [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.; Yu, J.; Zhao, Y. Many-objective optimization and decision-making method for selective assembly of complex mechanical products based on improved NSGA-III and VIKOR. Processes 2022, 10, 34. [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Xu, H.; Wu, X.; Tao, J.; Shao, G. The method of selective assembly for the RV reducer based on genetic algorithm. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2018, 232, 921–929. [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.; Jin, K. Density-based prioritization algorithm for minimizing surplus parts in selective assembly. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6648. [CrossRef]

- Szwemin, P.; Fiebig, W. The influence of radial and axial gaps on volumetric efficiency of external gear pumps. Energies 2021, 14, 4468. [CrossRef]

- Segura, C.; Coello, C.A.C.; Miranda, G.; León, C. Using multi-objective evolutionary algorithms for single-objective constrained and unconstrained optimization. Ann. Oper. Res. 2016, 240, 217–250. [CrossRef]

- Kannan, S.M.; Jeevanantham, A.K.; Jayabalan, V. Modelling and analysis of selective assembly using Taguchi’s loss function. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2008, 46, 4309–4330. [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, G. Introduction to Quality Engineering: Designing Quality into Products and Processes; Asian Productivity Organization: Tokyo, Japan, 1986.

- Opricovic, S.; Tzeng, G.-H. Compromise solution by MCDM methods: A comparative analysis of VIKOR and TOPSIS. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2004, 156, 445–455. [CrossRef]

- Behzadian, M.; Otaghsara, S.K.; Yazdani, M.; Ignatius, J. A state-of the-art survey of TOPSIS applications. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 13051–13069. [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Jain, H. An evolutionary many-objective optimization algorithm using reference-point-based nondominated sorting approach, part I: Solving problems with box constraints. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2014, 18, 577–601. [CrossRef]

- Deb, K. Multi-objective optimisation using evolutionary algorithms: An introduction. In Multi-Objective Evolutionary Optimisation for Product Design and Manufacturing; Wang, L., Ng, A.H.C., Deb, K., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2011; pp. 3–34. [CrossRef]

- Storn, R.; Price, K. Differential evolution—A simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. J. Glob. Optim. 1997, 11, 341–359. [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Suganthan, P.N. Differential evolution: A survey of the state-of-the-art. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2010, 15, 4–31. [CrossRef]

- Neri, F.; Cotta, C. Memetic algorithms and memetic computing optimization: A literature review. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2012, 2, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Auer, P.; Cesa-Bianchi, N.; Fischer, P. Finite-time analysis of the multiarmed bandit problem. Mach. Learn. 2002, 47, 235–256. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fu, X.; Fu, B.; Du, H.; Tong, H. Multi-objective optimization of aeroengine rotor assembly based on tensor coordinate transformation and NSGA-II. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 51, 190–200. [CrossRef]

- Huseyinov, I.; Bayrakdar, A. Novel NSGA-II and SPEA2 algorithms for bi-objective inventory optimization. Stud. Inform. Control 2022, 31, 31–42. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.S.; Lenin, N.; Rajamani, D. Selection of components and their optimum manufacturing tolerance for selective assembly technique using intelligent water drops algorithm to minimize manufacturing cost. In Nature-Inspired Optimization in Advanced Manufacturing Processes and Systems, 1st ed.; Kakandikar, G.M., Thakur, D.G., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 211–227. [CrossRef]

- Mencaroni, A.; Claeys, D.; De Vuyst, S. A novel hybrid assembly method to reduce operational costs of selective assembly. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 264, 108966. [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.H.Y.; Wu, C.F.J. Generalized selective assembly. IIE Trans. 2012, 44, 27–42. [CrossRef]

| Dimension chain | Ring type | Constituent ring name | Symbol | Nominal dimension (mm) | Tolerance grade (mm) | Upper deviation (mm) | Lower deviation (mm) |

| Radial | Increasing | Pump body bore diameter | 48.15 | H7 | +0.025 | 0 | |

| Radial | Decreasing | Gear outer diameter | 48.00 | g6 | –0.009 | –0.022 | |

| Axial | Increasing | Pump housing cavity depth | 21.03 | H7 | +0.021 | 0 | |

| Axial | Decreasing | Gear width | 21.00 | g6 | –0.007 | –0.018 |

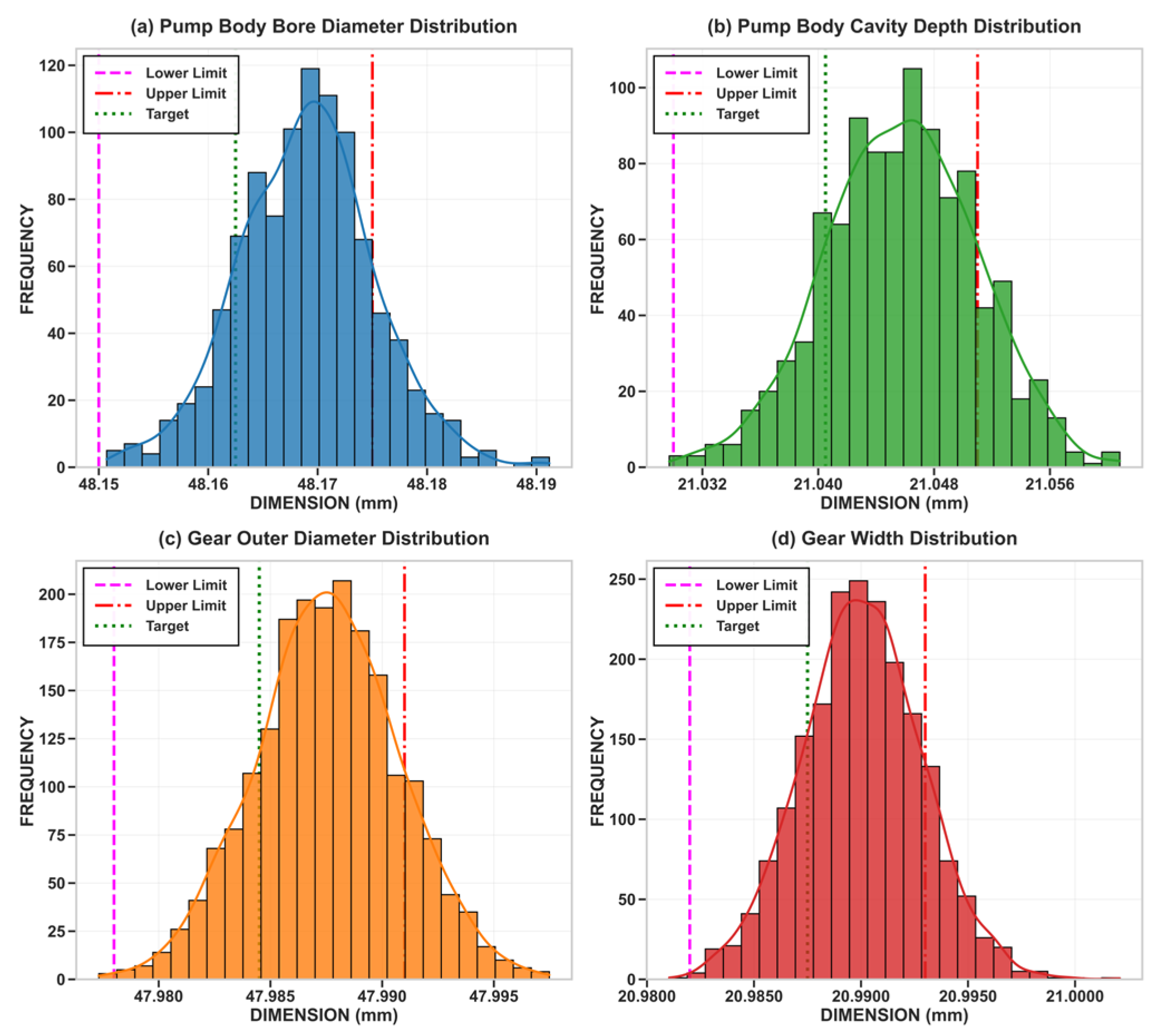

| Symbol | Tolerance (mm) | Nominal center μ (mm) | Reference scale σ (mm) |

| 0.025 | 48.1625 | 0.00417 | |

| 0.013 | 47.9845 | 0.00217 | |

| 0.021 | 21.0405 | 0.00350 | |

| 0.011 | 20.9875 | 0.00183 |

| Algorithm | Optimization strategy | Successful assemblies (units) | Assembly success rate (%) | Wasted parts (units) | Average quality loss |

| DG-MA | Priority on production | 988 | 98.80 | 36 | 9.09 |

| Priority on quality | 970 | 97.00 | 90 | 8.94 | |

| TOPSIS decision | 988 | 98.80 | 36 | 9.09 | |

| DG-MA (Grouped) | Priority on production | 965 | 96.5 | 103 | 9.27 |

| Priority on quality | 949 | 94.90 | 153 | 10.04 | |

| TOPSIS decision | 965 | 96.5 | 103 | 9.27 | |

| NSGA-III-I [19] | Priority on production | 977 | 97.70 | 59 | 9.15 |

| Priority on quality | 962 | 96.20 | 118 | 9.03 | |

| TOPSIS decision | 977 | 97.70 | 59 | 9.15 | |

| NSGA-II [34] + CA | Priority on production | 975 | 97.50 | 67 | 9.16 |

| Priority on quality | 932 | 93.20 | 204 | 8.76 | |

| TOPSIS decision | 972 | 97.20 | 84 | 9.17 | |

| NSGA-III [28] | Priority on production | 962 | 96.20 | 86 | 9.37 |

| Priority on quality | 949 | 94.90 | 145 | 9.11 | |

| TOPSIS decision | 957 | 95.70 | 119 | 9.22 | |

| SPEA2 [35] | Priority on production | 955 | 95.50 | 135 | 9.55 |

| Priority on quality | 940 | 94.00 | 180 | 9.28 | |

| TOPSIS decision | 948 | 94.80 | 156 | 9.41 | |

| IWD [36] | Priority on production | 956 | 95.60 | 132 | 9.27 |

| Priority on quality | 926 | 92.60 | 222 | 8.95 | |

| TOPSIS decision | 953 | 95.30 | 132 | 9.27 | |

| GA [16] | Priority on production | 952 | 95.20 | 124 | 9.28 |

| Priority on quality TOPSIS decision |

916 952 |

91.60 95.20 |

252 124 |

8.85 9.28 |

|

| Traditional selective assembly | 901 | 90.10 | 153 | 12.00 |

| Algorithm | Assembly success rate (%) | Wasted parts (units) | Average quality loss | Best HV value (e+04) | Runs(times) | |

| Algorithm in this paper | DG-MA | 98.80 | 36 | 9.09 | 3.2950 | 25 |

| DG-MA (Grouped) | 96.5 | 103 | 9.27 | 3.1850 | 25 | |

| Academic algorithm | NSGA-III-I [19] | 97.70 | 59 | 9.15 | 3.2315 | 25 |

| NSGA-II [34] + CA | 97.20 | 84 | 9.16 | 3.2287 | 25 | |

| GA [16] | 95.20 | 124 | 9.28 | 3.136 | 25 | |

| NSGA-III [28] | 95.70 | 119 | 9.22 | 3.2172 | 25 | |

| SPEA2 [35] | 94.80 | 156 | 9.41 | 3.1980 | 25 | |

| IWD [36] | 95.30 | 132 | 9.27 | 3.1690 | 25 |

| Algorithm | Assembly success ratio (% of successful assemblies) | Assembly quality improvement (%) | Convergence speed improvement (%) |

| DG-MA | 9.70 | 24.20 | 145.5 |

| DG-MA (Grouped) | 7.10 | 22.80 | –32.5 |

| NSGA-III-I | 6.22 | 23.70 | 35.0 |

| NSGA-II + CA | 7.90 | 24.30 | 22.7 |

| NSGA-III | 6.20 | 23.20 | 0.0 |

| GA | 5.70 | 23.50 | –20.6 |

| IWD | 6.10 | 23.80 | –15.6 |

| SPEA2 | 5.22 | 21.60 | –10 |

| Traditional selective assembly | 0.00 | 0.00 | \ |

| Algorithm | Average API | Average runtime |

| DG-MA | 0.98 | 39 min |

| DG-MA (Grouped) | 0.962 | 152 min |

| NSGA-II + CA | 0.958 | 45 min |

| NSGA-III-I | 0.957 | 41 min |

| NSGA-III | 0.949 | 47 min |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).