1. Introduction

Causal analysis is of great importance in neuroscience and in biology. Downward or top-down causation is a controversial idea, assuming that higher levels of organization can causally influence behavior at lower levels. In neuroscience, downward causation is often related to mental causation or free will, discussed in the context of the mind-body problem. So, Roger Sperry (1980), the Nobel laureate in physiology and medicine for his work with split-brain patients argues:

Conscious phenomena as emergent functional properties of brain processing exert an active control role as causal detents in shaping the flow patterns of cerebral excitation. Once generated from neural events, the higher order mental patterns and programs have their own subjective qualities and progress, operate and interact by their own causal laws and principles which are different from and cannot be reduced to those of neurophysiology.

Can consciousness, as a global product of neural activity, exert causal control over the brain? Or is consciousness a passive emergent phenomenon without causal power? If so, does this mean that consciousness cannot utilize downward causation, or is the concept fundamentally flawed? If the latter is true, what makes this idea so appealing in neuroscience, psychology, and evolutionary biology?

Downward causation is closely linked to various philosophical concepts from complex systems, nonlinear dynamics, and network science, such as emergence, self-organization, and synergy, often discussed in terms of broken symmetry, criticality, and scale-invariance (Turkheimer et al. 2022; Kesić 2024; Yuan et al. 2024). Synergy is an umbrella term that means an emergent property of complex multiscale systems to spontaneously become self-organized, as encapsulated in the slogan “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” Examples include flocks of birds, swarms of bees, and ant colonies, which are self-organizing complex systems, demonstrating emergent synergy from interactions of a large number of individual elements (Haken 1983; Kauffman 1993). Downward causation is proposed to explain how a system (the whole) can influence its individual components (parts).

Accordingly, the “strong” version of emergence, associated with downward causation (O’Connor 1994; Bedau 1997), can be linked to higher-order cognitive functions that process the synergistic information and interact by laws and principles that cannot be simply reduced to the underlying neurophysiology (Vohryzek et al. 2022). Regarding the causal role of consciousness, downward causation is implicitly involved in the free will problem, presented in the form of ‘synergistic core’ (Luppi et al. 2023; Mediano et al. 2022) that could spontaneously emerge in the brain, and govern the underlying neural activity by downward causation over hierarchical levels.

The physics of free will is heavily hinged on the notion of indeterminism. This starts with the question: how could deterministic brain dynamics generate conscious states, which were not predetermined from the past? Different quantum phenomena are suggested as a viable option to account for human (and animal) freedom to decide (Jedlicka 2017; Hunt and Schooler 2019; Yurchenko 2022). In contrast, the neuroscience of free will focuses primarily on Libet-type experiments, which involve comparing two distinctive things: neural activity and subjective experience. Two temporal measures were proposed to compare these variables, known as the readiness potential, detected from the supplementary motor area, and the awareness of wanting to move, reported with the clock. Since the initial experiments conducted by Libet et al.’s (1983), numerous studies have identified a delay between the neural motor predictors and conscious intentions to move around several hundred milliseconds (Schurger et al. 2012; Salvaris and Haggard 2014; Schultze-Kraft et al. 2016). The common conclusion drawn from these experiments is that experiencing free will may be illusory.

A long-standing controversy regarding this conclusion is that readiness potentials and conscious intentions belong to two different and hardly compatible domains: biophysical and psychological (Triggiani et al. 2023). The former operates exclusively on concepts and tools from dynamical models and network science, whereas the latter appeals to subjective and elusive notions such as attention, self-awareness, meta-cognition, and personality. Thus, all these experiments have already been distorted by the mind-brain duality, which has little relevance to the question of whether or not neural activity in the supplementary motor area, or anywhere else in the brain, precedes the emergence of a particular conscious state at a given time. In this sense, if Cartesian dualism is covertly admitted, Libet-type experiments do not threaten the existence of free will at all (Mudrik et al. 2022).

Nonetheless, assuming Cartesian dualism is not sufficient to explain how consciousness might have causal power over the brain. What processes or mechanisms could allow emergent conscious states to influence underlying neural activity? Downward causation has been proposed as a viable candidate for free will. Downward causation is typically characterized as a way, mediated by information flow, that enables a higher level to causally influence a lower level within a system (Farnsworth 2025). In biological sciences, thus, the mind-brain problem acquires a generalized form of neo-Cartesian dualism between information and matter by assuming that in biological (learning) systems information can have causal power beyond that provided by ordinary physical processes. More broadly, it is suggested that the emergence of life may correspond to a physical transition associated with a shift in the causal structure, where information gains direct and context-dependent causal efficacy over the matter in which it is instantiated (Walker and Davies 2013).

Meanwhile, many modern theories of consciousness directly associate consciousness with information that could, in principle, be processed by artificial systems capable of generating machine consciousness (Dehaene et al. 2017). On the other hand, even if the emergence of consciousness is associated with information processed by the brain (let alone other natural or artificial systems that are not commonly considered conscious), it does not endow consciousness with causal power in the brain. To account for mental causation or free will, these theories implicitly conflate information with causation, and adopt downward causation. In this sense, they can all be classified as theories of strong emergence (Turkheimer et al. 2019). Thus, the age-old problem of free will in the philosophy of mind transforms into the problem of downward causation in neuroscience, which takes the form of neo-Cartesian dualism in biology, where informational terms are all-pervasive (Maynard Smith 2000; Godfrey-Smith 2007).

The purpose of this paper is to disprove downward causation, unless the word “downward” is biased by referring to a spurious, scientifically illegitimate axis in spacetime. The paper is structured as follows: it begins with an examination of causation in various scientific fields, with emphasis on linear causal chains in physics. The relationship between physical causation and information-based measures of causation is then explored. After discussing the concepts of synergy and downward causation, the Causal Equivalence Principle (CEP) is introduced and generalized in terms of the continuity equation as the law of conservation of causation that forbids cross-scale causation in multiscale dynamical systems. The law is then specified in terms of causal scope, scale transitions, and spatial span. Two types of hierarchies (flat and multiscale) are outlined mathematically, showing that information can indeed be synergistic and flow across scales through modular -chains but it cannot have causal power beyond that provided by matter. The ensuing discussion shows that the CEP implicitly underlies the renormalization group formalism in physics and provides an ontological foundation for multilevel selection in evolutionary biology. There is no cross-scale causation, but selection operates simultaneously at all spatial scales, each exhibiting its own causal structure, not reducible to a lower one.

2. Causation

Causation is a vague notion. In the philosophical literature, it is often suggested to make a distinction between causation, defined as the production of one particular event by another, and causality, which is regarded as the law-like relation between causes and effects (Hulswit 2002). This distinction is linked to Peirce’s view that cause and effect are facts within an epistemological context (in terms of causality), while they are actual events within an ontological context (in terms of causation). In this paper, we will use the word “causation” uniformly to mean the causal analysis of actual events as they unfold in spacetime from the dynamics of physical and biological systems, governed by the laws of nature regardless of observability.

Additionally, the concept of cause is often confused with the concept of reason. A cause is a physical event, associated with the state of a system of interest, which is dynamically followed by another event. Events can be observed at different scales. Causation is evident in the form of canonical cause-effect relationships. Therefore, space, time, and scale are fundamental in understanding causation. In contrast, reason is a cause-like explanation for why something occurred, focusing on logic and neglecting space, time, and scale.

The confusion between cause and reason can be traced back to Aristotle, who defined four classes of causes (aitia) that Hofmeyr (2018) called “becauses” or explanatory factors: material, efficient, formal, and final causes, all applied to a thing that should somehow be designed and made of something. Although scientists do not normally think of causation in terms of Aristotelian classification (but see (Ellis 2023)), they still confuse cause with reason, as they are more interested in explaining observable phenomena than in how causation is carried out in time and over spatial scales. For example, a typical formulation in statistics that X (e.g., smoking) can cause Y (e.g., lung cancer) is concerned with a reason, not a cause. Smoking is a bad habit; cancer is a permanent state of health. Neither of these can be regarded as a particular physical event. Another archetypical example of confusing cause with reason is the famous ‘chicken-egg problem’, where each entity is a reason (not a cause) of the other.

On a strict account, causation should be concerned exclusively with relationships between transient events that can be observed at various spatial scales, such as a sunrise on Earth, a car crash on the road, a fired neuron in the brain, or the detection of a particle in a physical lab.

2.1. Physical Causation

Let us start with the formal definition of an event.

Definition 1. An event is an instantaneous state of a system of interest.

Note that the definition does not specify the scale of observation, as the systems of interest can vary in practice. The observation of events depends on two factors: (i) the spatial scale of observation, and (ii) the temporal resolution of observation. Now put aside the traditional view of the world as being full of different things with various physical properties such as position, momentum, size, shape, and so on. Instead, consider linear causal chains that pervade spacetime. From this perspective, there are no things, only instantaneous events that represent their dynamics.

Causal analysis becomes much more rigorous when causation is represented by linear causal chains, as conceptualized by the Causal Set Approach based on Lorentzian geometries of spacetime (Bombelli et al. 1987). This approach follows the principles of relativity theory, which specify that the speed of causal action cannot be faster than the speed of light. The finite speed of causation entails three consequences: (i) the cause must necessarily precede the effect, (ii) simultaneous events are mutually causally independent within a fixed frame of observation, and (iii) linear causal chains must satisfy the Markov property.

The linearity here means that any causal chain evolves only at the same scale and can be graphically depicted as a worldline in Minkowski space . Formally, if linear causal chains are defined on a vector space where the link between two nearest events is a vector symbolizing their cause-effect relation, then the linearity is defined traditionally via a linear map preserving additivity and homogeneity. These yield the so-called superposition property, which states that the effect caused by two or more events is the sum of the effects caused by each event separately. An immediate consequence of this is that every macroevent, observed at the macroscale, can be decomposed into the “sum” of simultaneous and, therefore, mutually causally independent microevents at the microscale.

A causal set is presented by a partially ordered set , with a binary relation ≺, which symbolizes causal order in physical spacetime and corresponds in relativity theory to a timelike interval between two events in Minkowski space (Sorkin 2009).

Definition 2. A causal set

is a set of elements (events) that satisfies the following conditions:

Condition (1.1) states that no event can be a cause of itself. Together with condition (1.2) they imply that linear causal chains in cannot contain closed loops. Intuitively, this follows from the uniqueness of events in spacetime. We can observe the same event repeatedly, but each occurrence is unique in time. If a unique event causes two independent (simultaneous and unique) events and , then the linear chain, containing , splits into two linear chains, one containing and the other containing . Conversely, two linear chains, containing events and separately, converge at event if is caused by both and .

The causal chains can be divided into “one-body” linear chains concerned with only one body (e.g., a simple pendulum) and “multi-body” linear chains involving many bodies (e.g., Newton’s cradle). In the former case, a linear causal chain can be described as a Markovian process by the temporal evolution of a system whose instantaneous states are events, each causally dependent on the previous one. In the latter case, when two (or more) systems interact, the resulting state of each of them is caused by both its own previous state and the state of the other system before the interaction. For example, a collision between two solid bodies, each with its own causal history, is an event that impacts the subsequent states of both bodies (including their energy and momentum in spacetime). Thus, linear one-body causal chains can converge and split at different events, generating multi-body linear causal chains. Both types of chains pervade spacetime as the global causal set . Furthermore, since events are observable at various scales and due to the linearity of causal chains, is not confined to a single preferred scale but should pervade spacetime at all scales.

Consider the murmuration of starlings, often presented as an example of emergent synergy. The flock of starlings contracts, expands, and even splits, continuously changing its density and structure as if it has a ‘life of its own,’ distinct from the thousands of individual birds which constitute the flock. Numerical 3D-simulations of a flock demonstrate that each bird should interact on average with a fixed group of neighbors from six to seven by relatively simple rules to exhibit typical emergent phenomena (Ballerini et al. 2008). In dynamics, the instantaneous states of birds are the microevents that causally impact each other, impelling neighbors to change their flight path in response to their actions. The feedback, repeated over time, generates reciprocal causal loops which are not, however, temporally closed in . Instead, there is a set of entangled linear multi-body causal chains at the scale of individual birds, involving avalanches across scales (Cavagna et al. 2010) and other features, indicative of self-organized criticality on the edge of chaos and order (Adami 1995). These macroscopic features manifest themselves only at the scale of the flock, whose instantaneous states we observe as macroevents that unfold in spacetime as a linear one-body causal chain from which synergistic phenomena emerge. Thus, one-body and multi-body causal chains not only can co-exist within a dynamical system but also pervade it at different scales.

2.2. Causal Reasoning in Statistics

The causal set can be locally represented by a directed acyclic graph , where is a set of nodes, with being the set of edges between nodes. Intuitively, if nodes in are associated with physical events, Bayesian networks for counterfactual causal modeling can then be imposed upon the linear causal chains in by ascribing random variables to nodes, with edges representing the conditional probability for the variables (Pearl 2000). This makes it possible to use “causal loops” in data analysis, where nodes are associated not with actual physical events but with phenomena (e.g., homeostasis) or categorial abstractions (e.g., age-Alzheimer’s disease) taken as the variables of the graph to detect statistical dependencies between them. In fact, Pearlian causal modeling is more concerned with reasonable explanations of regularities than with actual causal chains as they unfold in spacetime on their own by the laws of nature regardless of whether or not we can observe them. While the passage of time is coarsely grained in data obtaining, the scale and causal order are generally neglected in the probabilistic analysis of the data. Thus, there is a principled paradigm shift from explaining actual observer-independent linear causal chains to obtaining reasonable explanations of observable dependencies (Woodward 2003).

In neuroscience, an injection of propofol or the administration of a drug at a molecular scale are said to cause loss of consciousness or promote mental health respectively, both defined as examples of upward causation. In the same mode of counterfactual reasoning, a high body temperature, which is a weakly emergent property of a system, resulting from Brownian fluctuations of cell components in an organism, can be called a cause of mortality among patients. Although these examples propose verifiable cause-like explanations, they abandon the domain of physical causation, applicable exclusively to transient states of a system of interest at different moments of time, depending on a temporal resolution provided by observation. What is important here is that confusing cause with reason can make downward causation admissible as well, e.g., by saying that the environment exerts large-scale constraints on organisms through downward causation (Noble et al. 2019; Ellis and Kopel 2019). Somewhat ironically, counterfactual reasoning allows to turn the above examples of upward causation into downward causation by merely shifting the scale of observation in the so-called “fat-handed” interventions (Romero 2015), e.g., if an injection of propofol and the administration of a drug are defined as environmental constraints, imposed upon the patient’s brain by a clinician in a lab.

2.3. Causation and Prediction

We can observe a similar shift from actual causation to cause-like explanations in most famous causation measures such as Granger causality or Transfer entropy, which are formulated in terms of predictive power. Clearly, if it can be predicted that the occurrence of event X always entails the occurrence of event Y, then there is likely a linear multi-body causal chain between them. However, drawing this conclusion in the context of reason, may confuse or even ignore the scales of description between the variables of interest. Although these measures respect causal order, fine temporal and spatial resolution is limited in practical applications. Coarse-grained causal modeling is scientifically legitimate when applied correctly, but mixing different scales can create a loophole for downward causation. Some proponents of strong emergence directly equate coarse-graining with downward causation (Hoel 2017; Grasso et al. 2021). The following section will explain how this scientific bias arises from conflating causation and information in the context of linear causal chains.

3. Information and Causation

What makes information theory a useful analytical tool in neuroscience is its model independence, which is applicable to any mixture of multivariate data, with linear and non-linear processes (Wibral et al. 2015; Timme and Lapish 2018; Piasini and Panzeri 2019). However, its applicability to causal analysis must be taken with caution. Information theory was originally developed by Shannon (1948) for the reliable transmission of a signal from a source to a receiver over noisy communication channels. It was demonstrated that the maximal capacity

of a discrete memoryless channel with input

and output

is given by mutual information:

where

is Shannon entropy.

Since the physical nature of a signal, the length of a channel, and time for transmitting information are not conditioned, coarse-graining is explicitly embedded in the definition of entropy: is independent of the nature of signal and of how the process of transmitting is divided into parts, or, in Shannon’s (1948) own words: “if a choice be broken down into two successive choices, the original should be the weighted sum of the individual values of .” More formally, Shannon entropy is an additive measure: .

3.1. Information-Based Measures of Causation in Neuroscience

How can all of these elements, concepts, and information-theoretic measures be interpreted in the causal analysis of neural networks? First, the channel can be conceptualized as a tube that is maximally isolated from the environment for transmitting a linear one-body causal chain at an appropriate spatial scale. Reducing temporal resolution also allows us to “compress” the causal chain into a single pair, where the cause is an input

and the effect is an output

, omitting all intermediate events (“choices”) between them. Second, in neural networks, neurons can take the place of both the source and the receiver, while their instantaneous states represent events. Accordingly, synaptic connections provide the communication channels for a single causal pair between two neurons, which are the input

and the output

respectively (

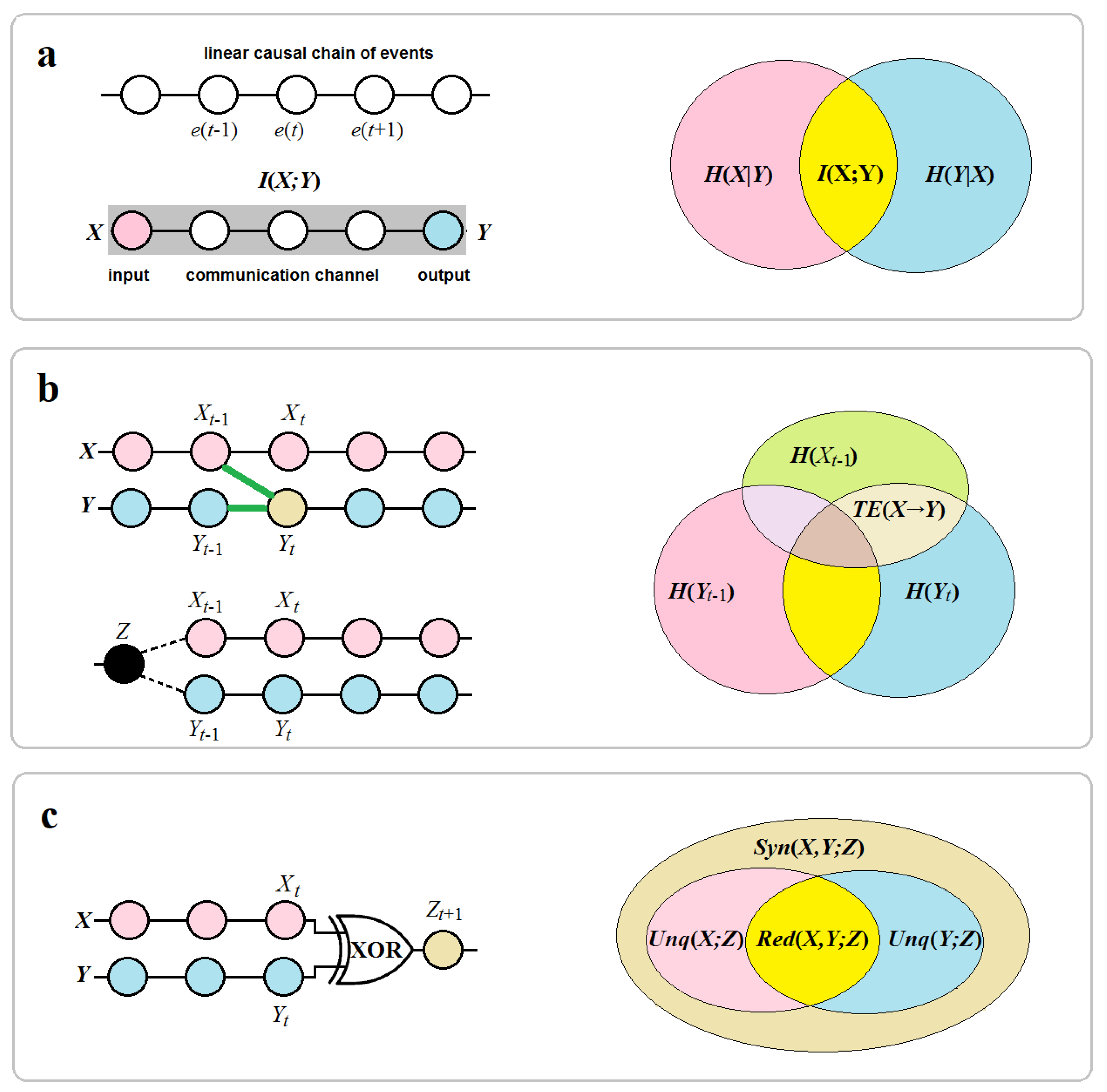

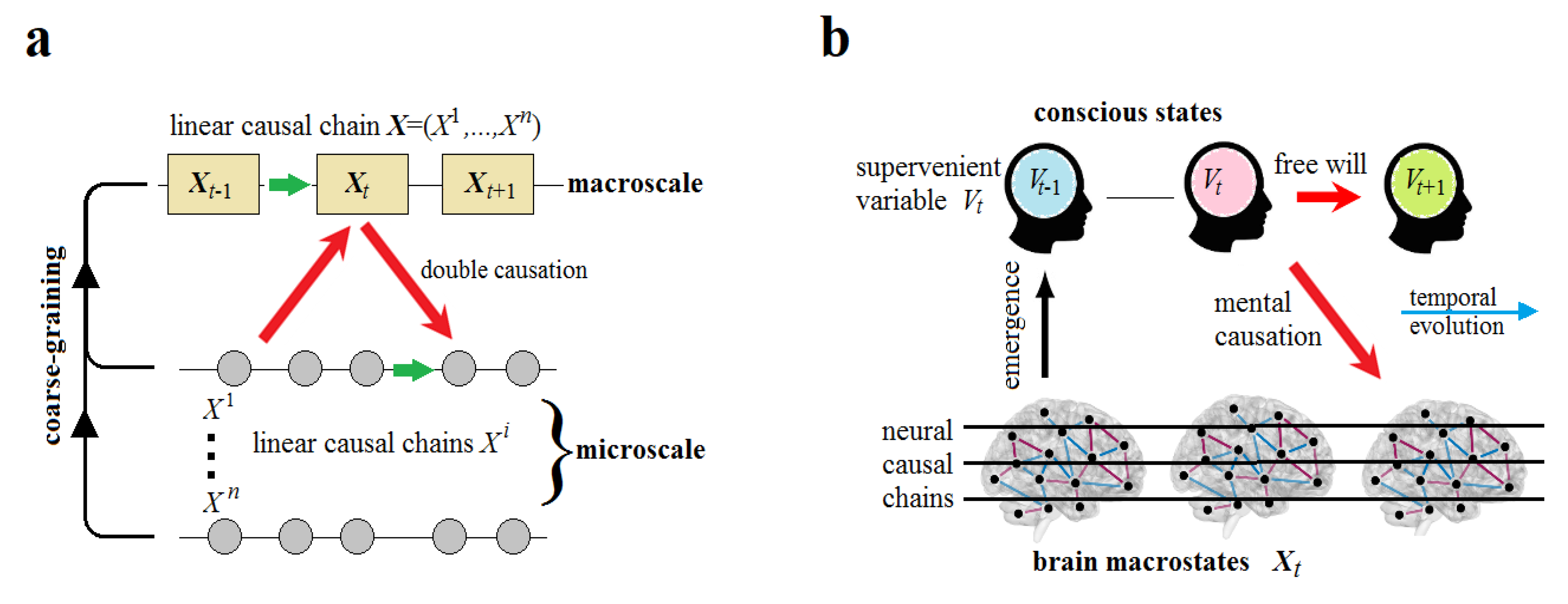

Figure 1a).

In neuroscientific studies, the temporal and spatial resolution, provided by various neuroimaging techniques, is reduced by ascribing input/output locations not to single neurons but rather to brain regions. Mutual information

is a coarse-grained measure that tells us how much our ignorance about one part of a system is reduced by knowing something about a different part of the system. Its value is zero when

and

Y are causally independent (there is no synaptic link between them) so that observing Yone tells us nothing about the otherX. Mutual information is symmetrical and upper-bounded by Shannon entropy:

The symmetry property makes this measure less appropriate for causal analysis since it does not discriminate the causal direction from an input (source) to an output (receiver). Although in engineering communications, the source and receiver are known so that the causal order between events is naturally preserved, one of the main goals of causal analysis in neuroscience is to unravel the causal structure of fine-grained synaptic circuitry in the brain. Contextually, mutual information is a measure of functional coarse-grained connectivity between large-scale neural networks, derived from statistical correlations.

In contrast, a more advanced measure, known as transfer entropy, can detect effective connectivity in a verifiable manner (Ursino et al. 2020). Transfer entropy (TE) is a measure of directed information transfer between two (or more) processes in terms of predictive information by observing how uncertainty on the present measurement of

is reduced if knowledge of the past of

is added to knowledge of the past of

:

TE is asymmetric and upper-bounded by mutual information (

Figure 1b). This is then expressed in terms of causation: if a signal A has a causal influence on a signal B, then the probability of B, conditioned on its past, is different from the probability of B, conditioned on both its past and the past of A, which shows a close analogy to Granger causality (Barnett et al. 2009). Since deriving a causal structure from complex systems such as the brain is challenging, many studies suggest that estimating directed information through TE can be an effective diagnostic tool for inferring causal relationships (Wibral et al. 2015). TE can capture causal order but only by virtue of preserving temporal order. There is evidence that this measure can sometimes fail to detect a causal link when it exists, and sometimes can suggest a spurious link (Lizier and Prokopenko 2010; James et al. 2016; Tehrani-Saleh and Adami 2018). In fact, TE measures correlations that can result from a direct causal effect via an edge between two nodes

and

in neural networks, indicating a causal link

between two events in two separate linear causal chains in the brain. On the

other hand, long-range correlations can also appear due to a common cause

of events in the past without a causal link between

them (

Figure 1b).

3.2. Synergistic Information from Multiple Resources

Since Shannon entropy is additive, mutual information underestimates the synergistic properties of information that can emerge from multiple inputs, such as stereoscopic vision in 3D space provided by the two eyes. More generally, a system exhibits synergistic phenomena, if some information about the target variable

is disclosed by the joint state of two (or more)

source variables that is not disclosed by any individual variable

or

. Williams and Beer (2010) had proposed Partial

Information Decomposition (PID) which allows for the division of

into information “atoms” as follows:

where

represents the redundant information about

contained in both

and

,

and

correspond to the unique information provided by

and

separately, and

refers to the synergistic information that can be derived from

and

together but not from each of them alone.

The simplest example of a synergistic network in engineering is one in which

and

are independent binary variables, and

is determined by the XOR function,

(where ⊕ is the XOR operator). It can be shown that the mutual information between the source variables and target variable vanishes,

, which implies that neither of them alone provide information about

. However, together they completely determine its state. The relationship between

with

and

is called “pure synergy” since the value of

can be computed only when both

and

are known (

Figure 1c). Although this technical example helps our intuition, it does not capture the essence of synergy as extra information (non-additive bonus) beyond the information, provided by the sources separately. Especially, the XOR gate has nothing to do with the large-scale patterns of synergy, such as the spontaneous self-organization of complex systems in the absence of external guidance (Haken and Portugali 2016). Instead, this example shows how transfer entropy can be blind to direct causal links. Because mutual information between

source variables and target variable in XOR networks is zero, transfer entropy vanishes too, , despite the obvious fact that they both causally affect the state of .

Synergy could be better described in the cryptographic context, where access to a secret is distributed among the participants, each of which holds some unique information about the secret. Thus, it should explain how a synergistic (non-additive) component, provided jointly by two or more sources, can make mutual information greater than the sum of the individual information contributions provided by the sources (Gutknecht et al. 2021):

In particular, since synergistic information is inherently non-additive, its PID-representation via Venn diagram is apparently inconsistent in set-theoretic terms: the whole

is greater than the sum of its parts

and

as if

would arise

ex nihilo like magic (

Figure 1c). An explanation comes from the fact

that unlike the other three “atoms” in Equation (5), the synergy component

emerges at a larger scale on the network of sources. Indeed, redundant

information can be completely retrieved from any one source at a corresponding

scale. Unique information is also provided at the same scale by each source

alone. In contrast, synergistic information can only be retrieved from all the

sources at a larger scale, corresponding to their union. Missing even one

portion of that extra-information from a single source could destroy

synergistic information.

To generalize aforesaid, consider a dynamical system of variables, evolving over a discrete (Markovian) stochastic process by a time lag 1 in a state-space . At first sight, the amount of synergistic information, provided by the system should be represented by the sum of the portions within that are provided by each source about at time. On the other hand, each portion of this extra information should initially reside within at the scale of each but emerge only at the scale of their union at time . As stated, Shannon mutual information does not respect the causal order between inputs and outputs (unless explicitly given). It also does not discriminate between scales. Nonetheless, temporal order can still be imposed on information-theoretic measures such as time-delayed mutual information or transfer entropy by taking into account that transmitting information across scales requires time.

Let us return to stereoscopic vision, and perform a simple thought experiment. If we close one eye, we will only receive mutual information between a target and a source (the second eye), losing all PID-components in Equation (5). Now if we have both eyes open at time

, do we (our brains) receive synergistic and unique information simultaneously or does the synergistic (stereoscopic) effect occur shortly after? If the latter is true, we could explain Equation (6) (and the set-theoretic inconsistency of synergy in

Figure 1c) via time-delayed mutual information as follows:

In this sense, Equation (5), presented in a timeless form, is not entirely correct: the components and do not occur simultaneously but decompose mutual information by a time lag 1. Informally, synergistic information is mutual information that emerges at the macroscale of a system from its unique information components provided by the system at the microscale, but with a time delay. This makes synergy a function of both time and scale. We can now interpret this component in the context of Equation (7). To bolster intuition, consider a thermodynamic process of the growth of a crystal in a supersaturated metastable solvent. In this physics-inspired scenario, the redundant information is like a seed crystal within the solvent. This seed is necessary for triggering the growth of a crystal lattice, i.e., , composed of the unique components that are dispersed throughout the solvent (Yurchenko 2024). Thus, the spontaneous growth of a large-scale crystal in a supersaturated solvent gives us an example of self-organized synergy, where causal processes are unambiguously presented by physical interactions.

The question we will be most interested in the next section is this: How are macroscopic emergent phenomena carried out by linear causal chains across scales? Could downward causation be possible due to synergy?

4. Synergy and Downward Causation

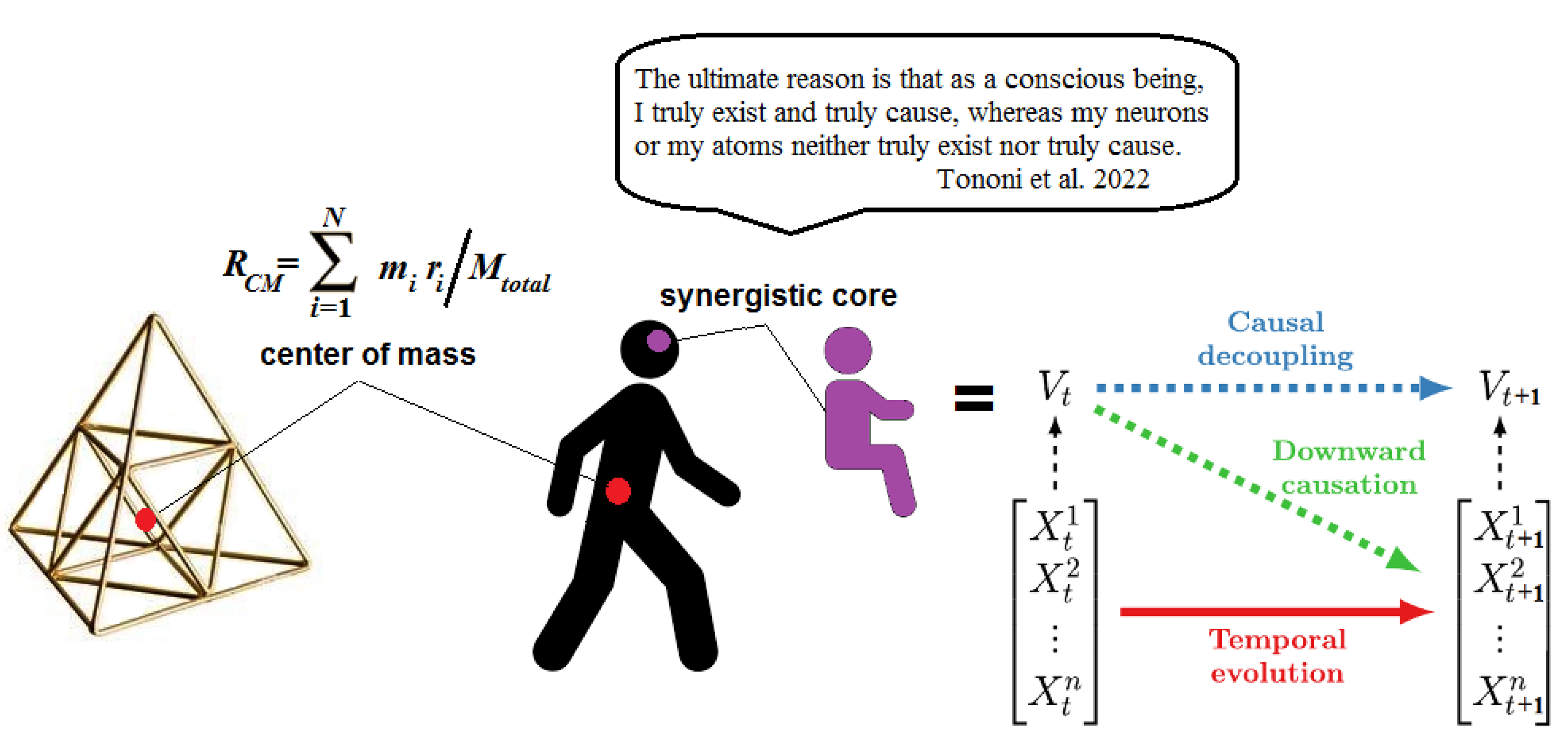

The PID was not initially developed by Williams and Beer to address causation. It was later suggested that the synergistic component could account for downward causation in stochastic dynamical systems, thereby reconciling the strong and weak forms of emergence (Varley and Hoel 2022). The proof utilizes time-delayed mutual information, interpreted in terms of predictive power, and places it in the context of Integrated Information Theory, which baggage is implicitly based on an assumption that conscious experience is identical to the maxima of integrated information , and can have free will to causally affect the brain, intrinsically overcoming its own neural correlates (Tononi et al. 2022).

By replacing the PID-framework with the

ID-framework, Rosas et al. (2020) transform the predictive power of a supervenient feature (macroscopic variable)

into the causal power of

over the underlying dynamical system

, presented as above. Thus, the temporal evolution of the system is described by a linear one-body causal chain at a macroscale, where

and

serve as the source and target states, respectively. The system is said to have causally emergent feature

if and only if

. Now, if

is associated with particular conscious states, emerging over time from the

-structure, while

represents the corresponding states of the neural network, this leads to mental (downward) causation defined formally by the following condition (Rosas et al. 2020):

In other words, downward causation occurs when an emergent feature

has both unique predictive power and irreducible

causal power over specific parts of the underlying system. In addition, causal

decoupling is proposed when

has also predictive and causal properties not only

over any specific part but also over the system as a whole (Mediano et al.

2022):

In fact, what Equation 8 and 9 have shown is that downward causation could be possible if the predictive power of information-based measures about a system, derived from observations, not only reflects causal processes that unfold in spacetime by physical principles, but also, if the system itself is information-processing, becomes equivalent to the causal power of the system itself as expressed in terms of the -ontology. This assumption can be seen as a specific part of a more general hypothesis, called “the hard problem of life” by Walker and Davies (2017), which suggest that a full resolution of the problem of how information, intrinsically processed by living systems, can causally affect matter, will not ultimately be reducible to known physical principles.

Now, consider the dynamical system in terms of the center of mass, which is the mean location of a body’s mass distribution in space. In the case of a system consisting of many bodies, the center of mass is calculated as the average of their masses factored by the distances from a reference point. The center of mass can then be associated with a supervenient variable in Eqs. 9 and 10. Indeed, Rosas et al. (2020) have shown that the center of mass of flocking birds in a 2D computational model predicts its own dynamics via mutual information better than it can be explained from the behavior of individual birds, i.e., via . The authors propose this result as an illustration of their theory of causal emergence. The center of mass emerges from the system’s dynamics as a gravitational pole that does not physically exist. This point-like center, though computationally powerful, may occupy empty space, having, by definition, no causal power since no observable events might occur there.

Analogously, in thermodynamics, temperature, as the average kinetic energy of particles in a system, is a coarse-grained variable that represents the behavior of all the particles. This supervenient variable allows to predict the system’s future state better than it could be made by measuring the speed of individual particles. The predictive value of macroscopic observations is undeniable: the second law of thermodynamics could not even be inferred from observations of microscopic reversible processes in statistical mechanics. However, it does not endow temperature with causal power (even though temperature is conventionally involved in the mechanical work done by a heated system).

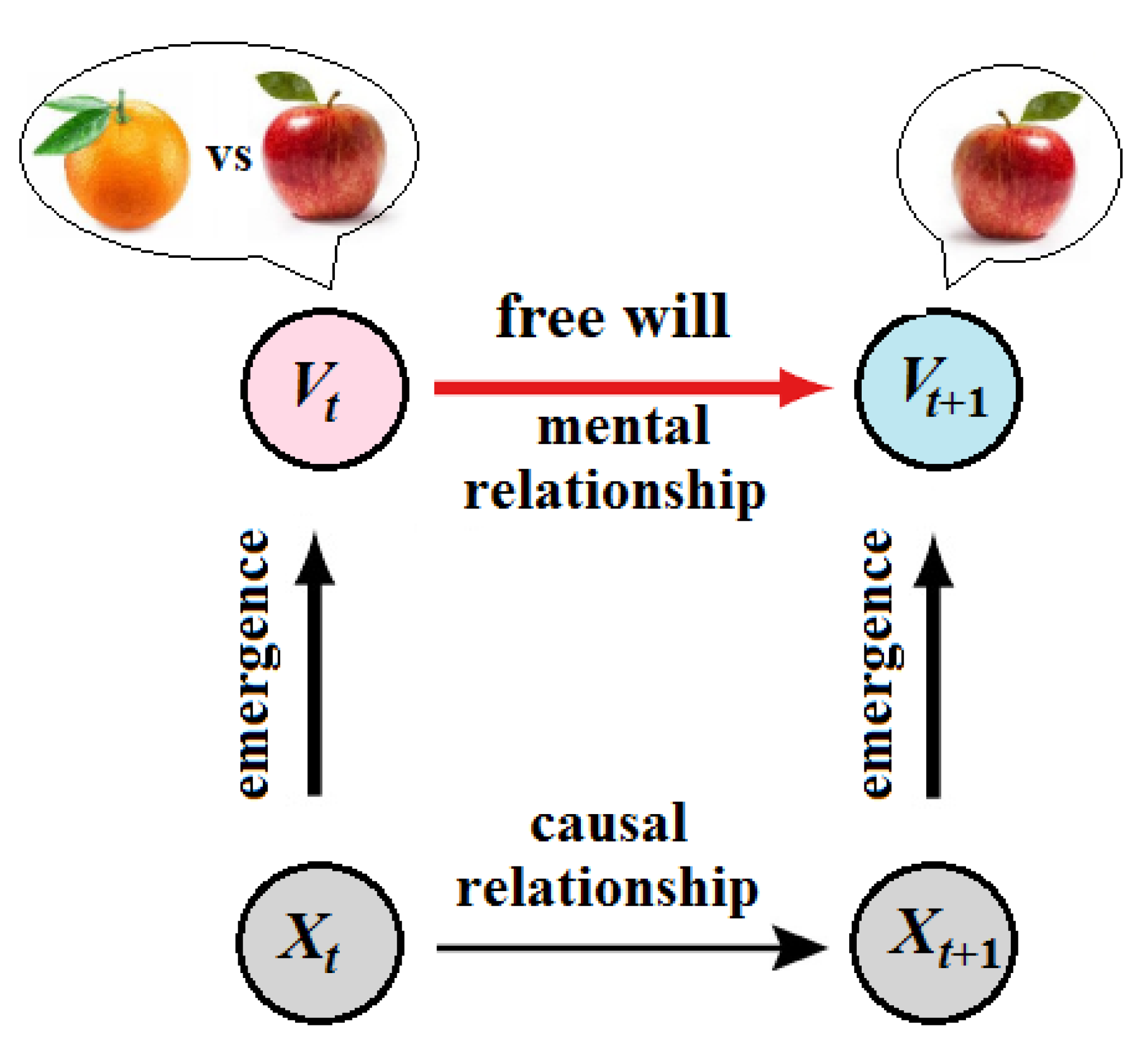

Similarly, knowing someone’s conscious (supervenient) state at the present moment allows to more accurately predict their future state than knowing their brain’s neurodynamics. For example, if someone (say Alice) is asked to choose between an apple and an orange, it can be predicted that Alice’s next state will include either “apple” or “orange” with an equal probability. With additional knowledge about Alice’s desires and beliefs, a psychologist might make more precise predictions about her choice, whereas a neuroscientist would hardly reach this level of predicting the future state of Alice’s brain from the previous state , both determined by a configuration of activated neurons (leaving aside the problem of decoding brain states into mental states). Note also that “desires and beliefs” are concepts of folk psychology, which can suggest a plausible reason (explanation) for Alice’s choice; however, these concepts could not even be formulated in terms of physical causation, defined on a dynamical system in a state-space .

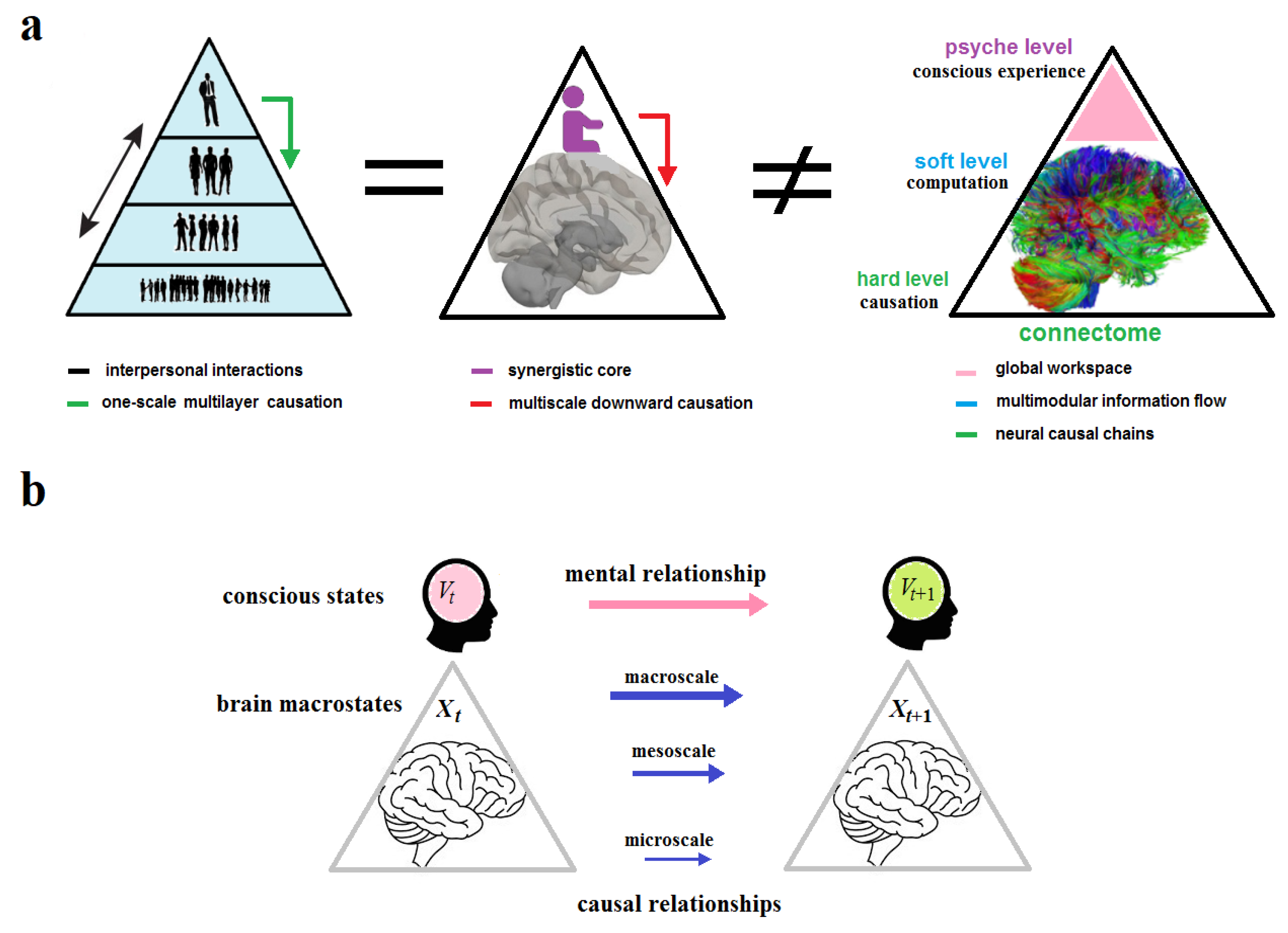

Yet, the choice made by Alice is typically associated with her free will. One could then compute something like a synergistic core in Alice’s brain, and identify this statistically well-informed and powerful entity with her Self or conscious “I” capable of exerting mental downward causation on the executive motor modules in Alice’s brain (

Figure 2).

The Causal Equivalence Principle, discussed in the next section, will disprove this possibility. The aim is to show that consciousness has no more causal power in the brain than temperature does in an ordinary physical system.

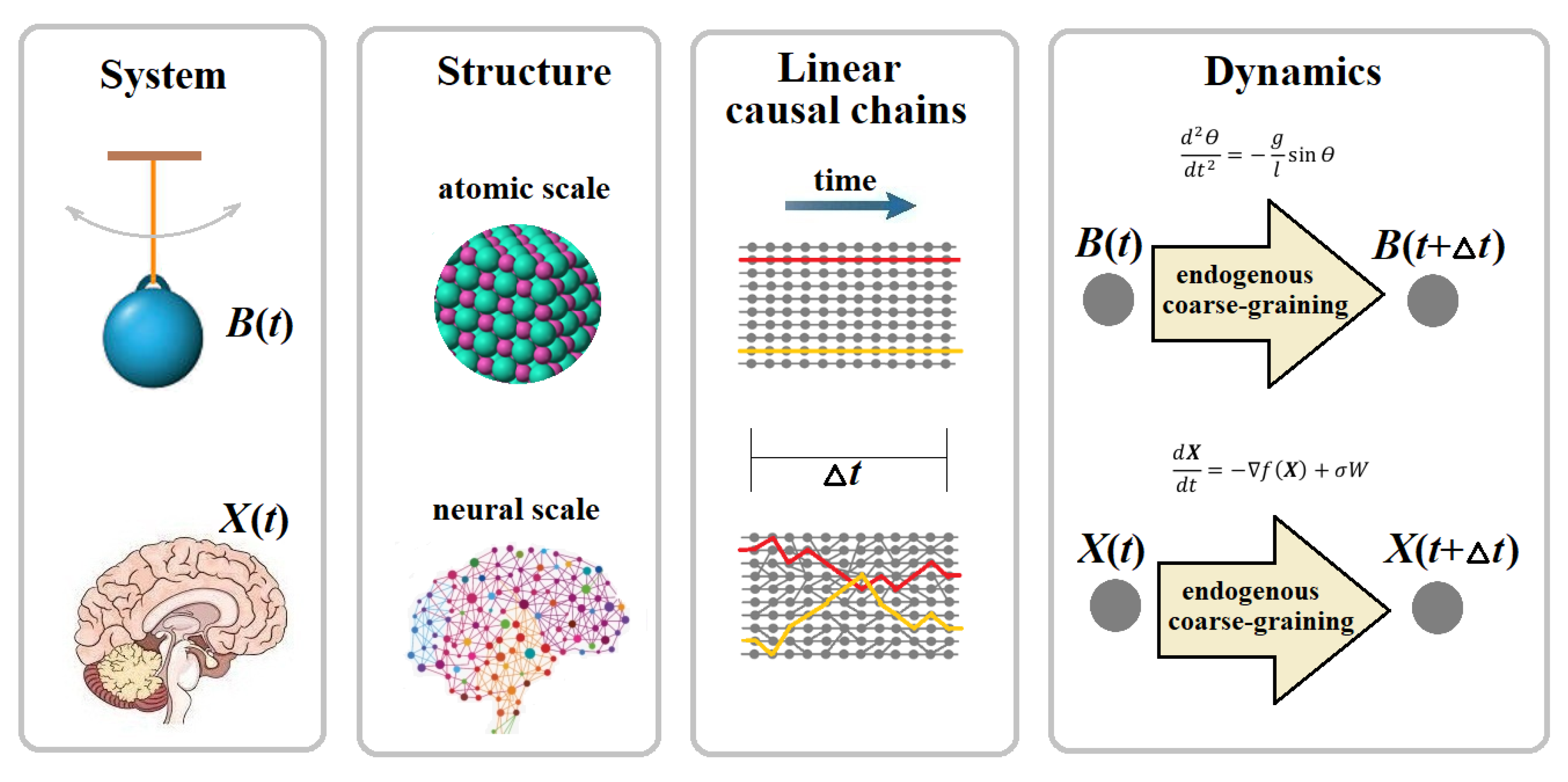

5. Causal Equivalence Principle

Downward causation requires the strong form of emergence, which is incompatible with reductionism. Reductionism argues that causation is valid only at the smallest scale of physical analysis. This requires a preferred scale for linear causal chains, whereas a common practice in modern science tells us that every science analyzes causal processes at a scale that is most appropriate for the systems of its interest. It would be very difficult or even practically impossible to explain cognitive brain functions at the atomic scale or to develop a sociological theory from a perspective of neural interactions. Reductionists see it as a matter of tradeoff between reasonable simplicity and the scope of detail, especially when fine-grained models may incur prohibitive computational costs, compared to low-dimensional coarse-grained models. This view dominates in physics despite the fact that fundamental physical laws (Newton laws or conservation laws) are scale-independent. Historically, Newton formulated his laws of motion without any knowledge about atoms. Likewise, a neuroscientist can study neural processes at different scales by means of appropriate models such as the Hodgkin-Huxley model, Wilson-Cowan neural mass equations, or Kuramoto coupled oscillators model, with no reference to the atomic scale.

The concept of causation is derived by us from the observation of events. Although each particular event occurs at a corresponding scale, the concept of an event is scale-independent, and no preferred scale can be assigned to it. As indicated above, we refer to completely different things as “events” whether it be a sunrise on Earth, a car accident on the road, a firing neuron in the brain, or the result of a quantum measurement in a physical lab. Since these systems can be studied at various spatial scales from atoms to whole organisms and large-scale environments, the events they produce occur at corresponding scales. However, it makes no sense to say that the same event will manifest itself at multiple scales, since a microevent cannot in principle be observed at the macroscale, and a macroevent cannot appear at the microscale. On the other hand, changing the scale of observation does not change physical reality, which exists independently of observations.

The scale-independence of causation can be formulated by analogy with the equivalence of all inertial frames of reference in relativity theory, which postulates that the laws of nature are invariant in all inertial frames of reference. Because of this equivalence, observations in one inertial frame can be converted into observations in another frame by the Lorentz transformation with respect to the speed of light. Likewise, one can assert that the dynamics of a system, governed by the laws of nature, cannot depend on the scale of observation.

The causal equivalence principle (CEP). Coarse-grained and fine-grained variables must yield the same dynamics and/or make consistent predictions on the temporal evolution of a system of interest, except for the scope of detail.

The CEP is not a rule extracted ad hoc from observations, but follows from the inherent properties of spacetime. Its detailed derivation from the causal set in Minkowski space can be found in (Yurchenko 2023a). The proof starts with the microscale and demonstrates how the ‘amount’ of all linear causal chains available there can be conserved by compressing them in space and time. In relativistic spacetime, spatial compression is consistently provided by mapping all simultaneous and, hence, mutually independent microevents onto their temporal slices, each defined as an equivalence class on a spacelike surface. Accordingly, temporal compression occurs along all timelike worldlines, where each linear causal chain of microevents is condensed into a single pair of microevents, typically based on the temporal resolution of observation provided there. As a result, spatial temporal compression both transform all microevents possible in spacetime into macroevents regardless of their location.

Although the CEP was derived in (Yurchenko 2023a) from the idea of spacetime compression, no event might be observed in empty space. There should be physical systems to produce events as their instantaneous states, which are causally connected in spacetime. Therefore, the “compression” should apply not to spacetime but, rather, to the universe as the largest dynamical system occupying spacetime. In this case, the CEP represents a metaphysical realism: The existence of the universe is observer-independent. But how does the universe exist? Is it an atomic (quantum) universe as reductionism claims? We know that organisms consist of atoms, but there are no living entities at the atomic scale. Life is a large-scale emergent phenomenon. In this sense, from a reductionist perspective, the existence of living systems may be viewed as illusory in the atomic (quantum) universe. If so, how do living entities such as bacteria and humans exist? More broadly, how do multiscale dynamical systems like organisms, ecosystems, and planets exist? To answer these questions, we must extend the above postulate to the statement: The universe, with all its components, exists at all spatial scales simultaneously, regardless of whether or not they are accessible for observation.

In this context, the CEP can then be generalized as the law of conservation of causation, expressed in the formalism of Liouville’s theorem (Yurchenko, 2025). This theorem states that the density of representative points of a dynamical system in phase space does not change with time. Its consequence is that the entropy of the system, defined as the logarithm of the volume in phase space,

, remains constant for a perfect observer capable of distinguishing all causal chains within a system. However, for causal analysis, it is more appropriate to consider the theorem in terms of the continuity equation in fluid dynamics. This equation represents the idea that matter is conserved as it flows in spacetime:

Here

is the divergence operator,

is the flow density, and

is the flow velocity in a vector field. For an incompressible fluid, the density

, so that the divergence of the flow velocity is zero everywhere,

. Informally, the equation implies that the control volume of a flow remains constant over time (

Figure 3a).

Now, let us consider a multiscale dynamical system

of

variables. Its macrostate

can be observed as a macroevent

which, by definition, is the “sum” of all simultaneous and causally independent microevents

at a moment

, each associated with a corresponding state of the system component

. Suppose there is a linear causal chain of such microevents

per unite time

. The causal order will still be preserved in a chain of macroevents

by reducing the temporal resolution of observations to the lag

. Therefore, the transition across spatial scales does not change the “quantity” of causation within a multiscale dynamical system for a perfect observer (

Figure 3b). All scales are causally closed.

Another explanation comes from the principle of locality in physics, which states that an object can be causally affected only by its immediate surroundings and not by distant objects, also known in relativity theory as the dictum “No instantaneous action at a distance,” which implies that an action between events is limited by the speed of light. When applied to scale analysis, the principle of locality entails another fundamental property of causation. It states that a microevent (representing the state of an object at time ) at a given scale can be influenced simultaneously by two or more neighboring events (objects), but not by numerous distant events at that same scale. If that were the case, the combined (non-local) effect of these distant events could be regarded as a macroevent that exerts downward causation on the microevent . Thus, the principle of locality forbids the whole from influencing its individual parts. Causally, the whole cannot be greater than the “sum” of its parts.

The law of conservation of causation. The flow of causation in the universe is conserved across scales.

In the context of Noether’s theorem, for every continuous symmetry in the laws of nature, there exists a corresponding conservation law. Accordingly, conservation of causation can be inferred from the invariance of the laws of nature under scale transitions. In effect, this law states that the choice of units of observation in spacetime does not affect the flow of causation. No linear causal chain at a fixed scale can intervene in linear causal chains at other scales. The law rules out both upward and downward causation, which can only appear as artifacts of imperfect observation when different scales of causal analysis are mixed. On the other hand, according to the law, the Markov property remains invariant across scales due to the linearity of causal chains.

6. Corollaries of the CEP

The CEP has corollaries that are directly relevant to the relationship between causation, information, and synergy in biological systems discussed in the previous sections.

Corollary 1. There is no causally preferred spatial scale.

Thus, the CEP is not a reductionist principle. In physicalist terms, reductionism is based on two premises: (i) micro-causal closure and (ii) macro-causal exclusion (Kim 2006). In contrast, the law of conservation of causation states that not only the microscale is causally closed, but every scale is causally closed.

Formally, the CEP is similar to the Principle of Biological Relativity of Noble et al. (2019) which states that there is, a priori, no preferred level of causation across the multiple scales of networks that define the organism. However, there is a principled distinction between them. Biological relativity has no relevance to relativity theory, and typically conflates the notion of reason (as a logical cause-like explanation) with the rigorous concept of cause (as a physical event in spacetime, linked to an instantaneous state of a system of interest). As a result, this admits cross-scale causation. Upward causation is defined by the mechanics that describe how lower elements in a system interact and produce changes at higher levels. Downward causation is represented by the set of constraints imposed by environmental (large-scale) conditions on the system’s dynamics at lower levels.

In contrast, the CEP forbids both kinds of cross-scale causation. Corollary 1 is compatible with Rolls’ approach to causation, which argues that (linear) causal chains operate within scales but not across scales. He regards downward causation as a philosophical “confabulation” aimed at disproving reductionism (Rolls 2021).

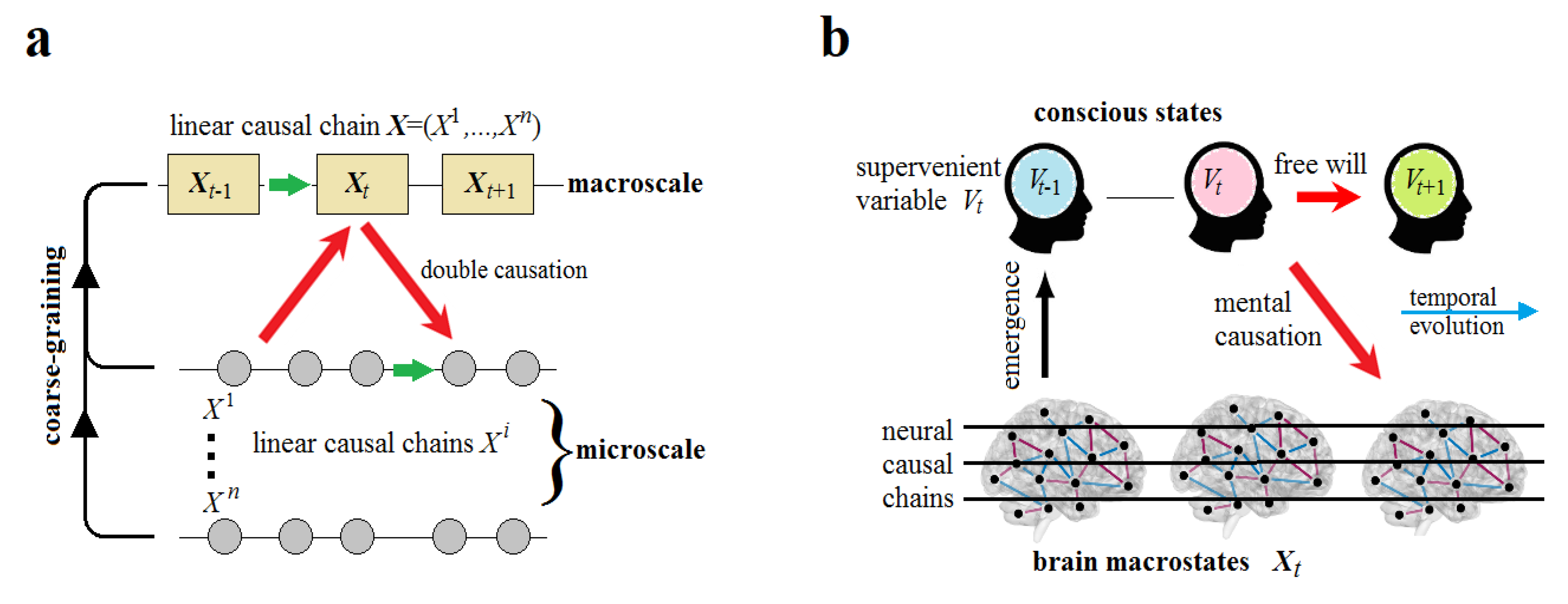

Corollary 2. Mixing two (or more) causally closed scales leads to the double causation fallacy or overdetermination.

Note that “overdetermination” here must not be confused with a case when two or more simultaneous events cause another event, all occurring at the same scale. Such collisions (and bifurcations) between different linear causal chains can be ubiquitous in the causal set

. Corollary 2 permits linear causal chains to intersect at any one scale but not across scales. The double causation fallacy arises when both macroscopic and microscopic variables are supposed to causally affect the same event (

Figure 4a) despite the fact that microevents cannot in principle be observable at the macroscale, and vice versa.

In the classic example of overdetermination, as suggested by Kim (2006), there are two emergent mental states M and M* that supervene on physical states Q and Q* of a system S respectively. Now, if we agree that M causes M*, then we must also agree that Q is causal for M*. If both M and Q explain M*, then the explanation is overdetermined. This example, however, is more concerned with the mind-body problem than with downward causation. As stated, assuming downward causation alone is not sufficient to solve the mind-body problem. To account for mental causation, neo-Cartesian dualism is necessary to conflate causation with information.

To specify the problem, we translate the above example into the formalism of multiscale dynamical systems. Let large-scale supervenient variables

and

represent mental states M and M* of a multiscale dynamical system

such as the brain. The temporal evolution of each its part

can be represented by a linear causal chain at a corresponding scale less than the scale of the system. In dynamics over time, the state

of each part is determined by its previous state

(though other parts can intervene in the chain). Double causation arises when

is also affected across scales by

. Thus, mental causation would be possible if the conditions of Equation (8) were satisfied (

Figure 4b). But this is not the case for the CEP.

Ultimately, the CEP rejects the strong version of emergence (including downward and mental causation) but adopts its weak version. The CEP may maintain a conventional form of free will on the condition that brain dynamics could not be completely predetermined from the past. Let

and

be two brain states of a corresponding one-body linear causal chain at the macroscale. We say that

is caused by

. Now let

symbolize this linear chain that can be described as a discrete stream of conscious states emerging in critical points of Langevin dynamics (Yurchenko 2023b). According to the CEP, all scales are causally closed so that mental (downward) causation from

to

is precluded. Instead, conscious states passively emerge from brain macrostates. This can be formally provided by mapping the brain states

to the corresponding conscious states

in the stream. Thus, the causal relationship between

and

is spontaneously transformed via the mapping into the mental relationship between

and

as if the former caused the latter (

Figure 5).

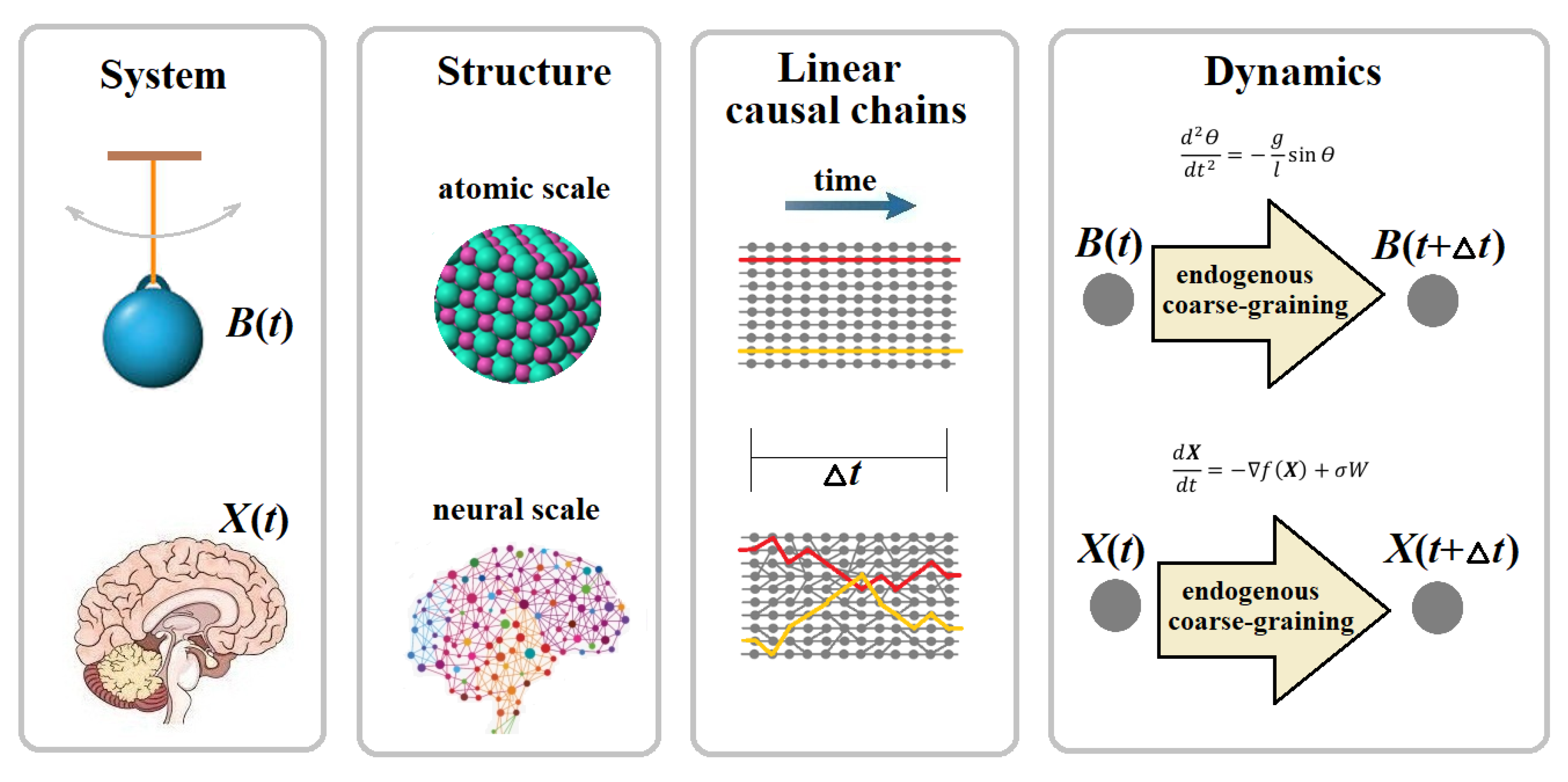

Corollary 3. Endogenous coarse-graining is causally legitimate.

Here, coarse-graining is not related to dimensionality reduction in statistical analysis such as principal component analysis or data compression. Instead, it concerns actual events as they occur according to natural laws, forming a lattice of causal chains in spacetime. Coarse-graining depends on the spatial and temporal resolution of observations as if spacetime itself was compressed, making only macroevents observable. Examples of coarse-graining include temperature in thermodynamics, the center of mass in mechanics, condensed nodes in network analysis, and phase-space models that reduce population size to a single variable in population dynamics. These examples illustrate weak emergence, where “the map is better than the territory” (Hoel 2017), rather than strong emergence, where “the macro beats the micro” (Hoel et al. 2013).

Flack (2017) suggests to distinguish this kind of coarse-graining, imposed by scientists on a system of interest to find compact descriptions of its behavior for making good predictions, and endogenous coarse-graining, imposed by nature itself upon matter. Endogenous coarse-graining is what allows us to distinguish between a physical body and its environment. A physical body is by definition a system of components that are more causally connected to each other than to the components of the environment. In the case of an atom, its electrons are more causally connected to each other and to the atom’s nucleus than to the electrons and nuclei of surrounding atoms. Similarly, a molecule consists of atoms that are chemically coupled with each other either directly or through causal linear chains to a degree that exceeds their coupling with the atoms of other molecules. At a larger scale, the surface of a biological cell is a boundary between the causal strength of internal (atomic and molecular) interactions within the cell and its interactions with the environment.

Endogenous coarse-graining is evident in the multiscale organization of matter from atoms to planets, and, especially, in biological systems, organized across scales from genes to cells to organisms. Although linear causal chains pervade spacetime uniformly, physical bodies and living organisms are more internally connected than externally. This makes them partially autonomous from their environment. In fact, internal causal connectedness (or causal closure) is fundamental to our understanding of physical existence. For example, when we see a stone rolling down a hill, we perceive the stone as a distinct physical body separate from the parts the hill consists of. Also, through observations we can distinguish a leaf on a tree and a tree in a garden across different spatial scales. Why are we sure that these are real physical entities and not illusions created by the sophisticated computational power of the brain, which transforms the beam of photons hitting one’s retina into a series of visual images?

This problem can be traced back to the words of the French philosopher Hippolyte Taine: “Instead of saying that a hallucination is a false exterior percept, one should say that the external percept is a true hallucination” (Corlett et al., 2019). In this context, our observations of hills, stones, gardens, trees, and leaves are true epistemologically because they all exist as endogenously coarse-grained entities. The brain, as a predictive system, could not obtain the information necessary to discern them if they were not internally more causally connected than externally. Endogenous coarse-graining here means that these entities exist ontologically due to their internal causal connectedness, not just as artifacts of our observation. In fact, internal causal connectedness is the primary, if not the only, intrinsic property of physical entities that enables us (our brain) to distinguish them and their parts from one another and from their environments.

Endogenous coarse-graining is closely related to the concept of individuality in biology, which is typically divided into four kinds: metabolic, immunological, evolutionary, and ecological individuality (DiFrisco 2019; Kranke 2024). Since information is physically instantiated in the organizational structure of matter and conveyed through spacetime causally (

Figure 1a), the relationship between endogenous coarse-graining, based on internal causal connectedness, and biological individuality can be statistically inferred in terms of time-delayed mutual information or transfer entropy from the definition: “If the information transmitted within a system forward in time is close to maximal, it is evidence for its individuality” (Krakauer et al. 2020). A similar measure, based on the concept of non-trivial information closure (Bertschinger et al. 2008), is proposed in neuroscience to explain the large-scale emergence of consciousness (psychological individuality) from neural activity in the brain (Chang et al. 2020). Thus, endogenous coarse-graining, as an intrinsic property of matter organization across scales, underlies a set of interdependent concepts in biology and complex systems such as emergence, synergy, self-organization, information closure, autonomy, biological individuality, autopoiesis, cognition, and subjective experience.

Although the law of conservation of causation explains why different levels of description of the same system can co-exist and be causally valid, the question we are interested in now is how the scales are related to each other within the spatial span of endogenously coarse-grained dynamical systems.

7. Causal Scope, Scale Transition, and Spatial Span

In practice, scientists are naturally constrained to choose an elementary basis for the lowest boundary of observation and causal analysis at a scale that is most suitable for the size and dynamics of a system of interest (e.g., the solar system versus a cell). The basis can be chosen explicitly or implicitly, but it will always be embedded in the framework of research. All scales below the basis are ignored (e.g., quantum, atomic, molecular). There will also appear the upper boundary of observation for causal analysis over the spatial (and temporal) span of the system of interest. Again, all scales above the upper boundary are ignored and commonly related to the environment (e.g., populational, ecological, planetary). Within this span, three scales are typically proposed: the microscale for the elementary basis, the macroscale for the system itself, and a mesoscale between them.

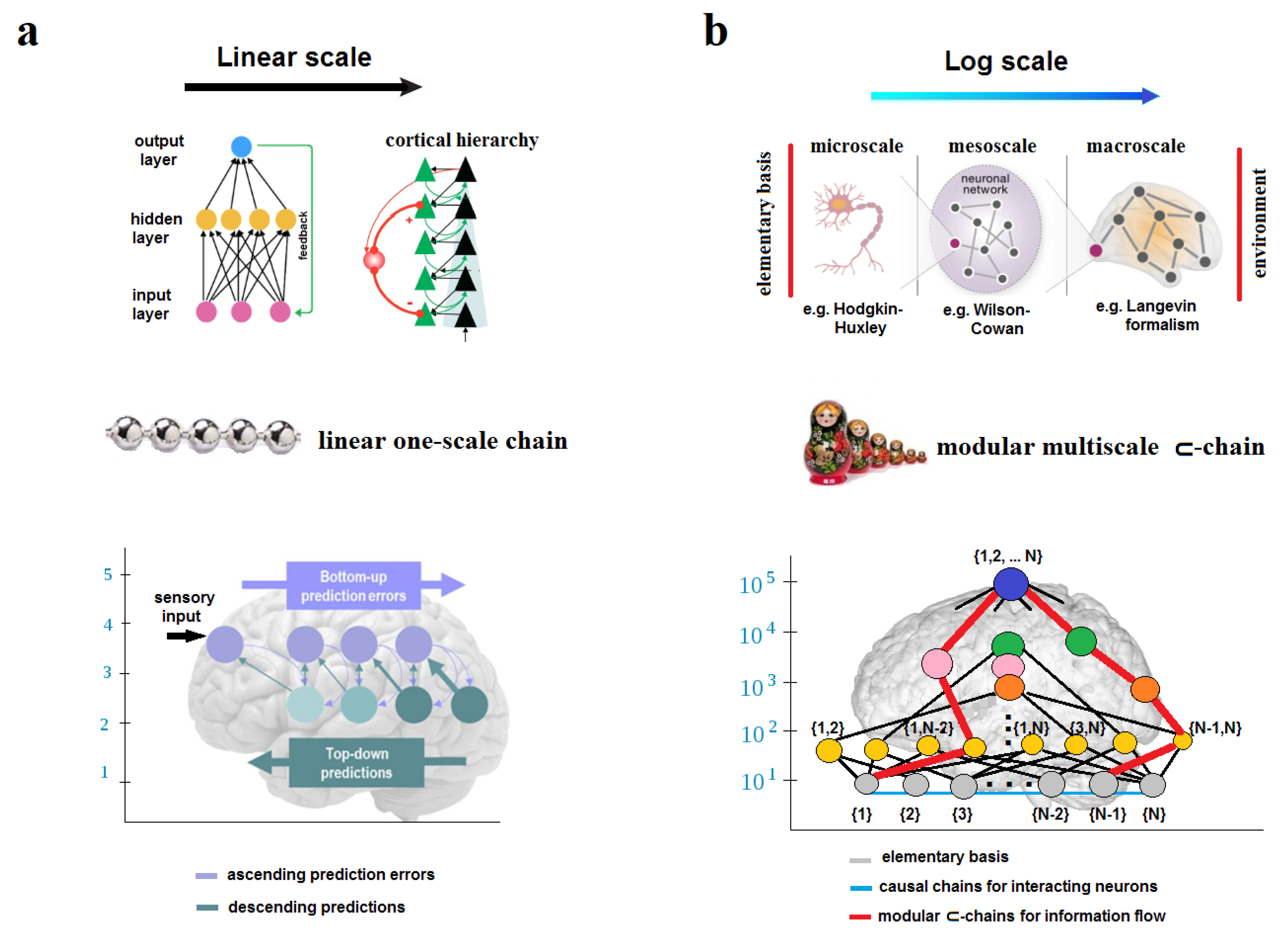

At first sight, graph theory provides the best representation of causal chains that occur and are valid only at the same scale of spatial resolution. However, the graph, defined on a set of nodes, does not discriminate between scales: one node is taken to be of the same size as another node. Although the graph can then be coarse-grained by condensing local networks of strongly interconnected nodes into single large-scale nodes (modules), such transformations would change the scales of description but preserve one-scale representation. According to the CEP, the graph-theoretic representations could indeed be best for dynamical causal modeling, but only on the condition that all the nodes were physically related to the elementary basis of a system of interest. In the case of the mind-brain relation, the elementary basis should be related to the scale of single neurons, while communication channels for linear causal chains between neurons should naturally be provided by structural (anatomical) connectivity via white-matter fibers. Unfortunately, graph-theoretic representations can roughly mix different spatiotemporal scales, as it occurs by detecting statistical correlations of functional connectivity between different regions of the brain with the help of various neuroimaging techniques. Spurious causation can arise there (Reid et al. 2019; Weichwald and Peters 2021; Barack et al. 2022).

Overall, the CEP argues that observers should keep the scales of causal analysis isolated. Theoretically, we should denote the elementary basis of a system of interest as scale 1. The sets of elements, , over the basis, should spontaneously produce the class of equivalence by their cardinality, assigned then to scale . Each new scale would occur by adding a new element to each of the sets. Scales would be additive, in the sense that a set of interdependent components might be replaced by a single component whose scale is equal to the sum of the scales of the individual components (Allen et al. 2017). In practice, however, the distinction between scales cannot be so simple. For example, where should we place the boundary between the microscale and a mesoscale in our observations? More broadly, how should the molecular scale transition spontaneously into the cellular scale, and how should the scale of single neurons consistently turn into the scale of neural functional modules?

This problem is very similar to the so-called “heap paradox” in philosophy, which argues that if a grain of sand is not a heap, and adding a single grain of sand to something that is not a heap does not produce a heap, then a heap is physically impossible despite the fact that it emerges in the eye of an observer. Does the heap of sand really exist? The answer must start with the remark that every grain of sand is already a “heap” of atoms more causally connected with each other than with atoms of other grains. So, a heap of sand arises at a larger scale analogously when a number of grains become causally coupled with each other stronger than with the environment. Therefore, intervention on any part of the heap will causally affect other parts rather than distant objects outside the heap, for example, to bring about an avalanche.

What follows from this dilemma is that the boundaries between scales cannot be defined rigorously but only in terms of neighborhoods, by analogy with topological spaces, in which closeness (or limit) is described in terms of open subsets rather than metric distance. In the topological presentation, the number of interacting individuals must be fixed, whereas in the metric presentation, the number can vary with density per unit volume. In a graph , let each unit scale , defined as the equivalence class by cardinality , be assigned to the neighborhood such that , where is the causal scope (similar to the degree of a node or branching factor in graph theory), which is specific to a particular class of systems, and determines the topological scale parameter, imposed by the principle of locality that is fundamental to causal analysis.

Now, the CEP allows an event to cause

consequent events or, equivalently, to be caused by

previous events at the same scale of observation. However, the principle of locality forbids

to be larger than the neighborhood

of the given scale. The nearest upper scale is defined as

. Thus, the progression of scales will grow exponentially, starting with the initial unit scale

in the elementary basis of

(

Figure 6a):

It is important to note that Equation (11) must be interpreted correctly. The causal scope does not imply that a system is divided into groups of

elements, each forming a clique isolated from the rest of the system. If that were the case, scale transitions would only increase the size of cliques (

Figure 6b). Instead, while the groups are defined numerically by the equivalence class, their neighborhoods

topologically cover the system entirely at every scale by involving intersections between nearest groups with each other, rather than partitioning it into isolated groups of exponentially growing size. Therefore, scale transitions increase the coherence of the system as a whole without making it a clique of completely interconnected elements.

Coherence here refers to the so-called small-world property of a graph, also known as the six degrees of separation in social networks. This property is characterized by a high degree of local clustering and a relatively short path length. The latter is the average number of edges in the shortest path between two nodes in the graph

, defined as

(Watts and Strogatz 1998). In other words, the internal causal connectedness of an endogenously coarse-grained system

guarantees that although the principle of locality forbids its two elements at a distance to have a direct causal link, they can still correlate over time via a multi-body causal chain of finite length of mutually causally connected neighbors within the system (

Figure 6c). We can thus be certain that such a causal chain exists or is intrinsically feasible between any two organelles in a cell, two neurons in a brain, or two organs in an organism.

[1]

Now, let us consider the multiscale nonlinear phenomena of coherence, such as the spontaneous growth of a crystal in a supersaturated solvent or an avalanche that can occur in a heap of sand, a flock of starlings, or a neural network in the brain. These phenomena are triggered by a single element such as a seed crystal, a grain of sand, a single bird, or a neuron. One might argue that these dynamics exemplify upward causation, enabling a part to causally affect the whole across scales. Another famous example of upward causation is the butterfly effect, a metaphor in chaos theory, where a microevent, the flap of a butterfly’s wings, can ultimately cause a series of macroevents, like a hurricane. But is there upward causation?

In a dynamical system of

elements, each element can only causally affect up to

elements at time

, but it cannot simultaneously influence an unlimited number of elements beyond its neighborhood

as dictated by the principle of locality. For example, for a starling flock, the causal scope

(Ballerini et al. 2008), whereas for the rat barrel cortex,

(London et al. 2010). According to the law of conservation of causation, when the scope of elements exceeds

, the scale of observation must be changed (

Figure 6a). This marks the boundary between the two closest scales over which the avalanche progresses, making a system more coherent over time. Instead of upward causation, there is a great number of linear multi-body chains with a common cause in the distant past that triggered the avalanche. There are statistical (functional) correlations among all elements of the avalanche due to the common cause, but there is no immediate causal link between them. If there were, we would have a brain where all neurons form a clique completely interconnected by white-matter fibers. Thus, this is not the case.

Remarkably, assuming upward causation in the above scenario would make downward causation possible as well. If one element was capable of affecting an unlimited number of elements simultaneously, then the opposite process should occur spontaneously. Eventually, there would be a moment when a large number of elements simultaneously affect one element, as if the whole could causally impact its parts. This scenario implies that the brain should again be a clique of neurons completely interconnected via synaptic communication channels despite neurobiological evidence indicating that in the brain, each neuron has, on average, several thousand synaptic connections with other neurons, and only a few can be activated simultaneously. This evidence also demonstrates how the principle of locality is instantiated in the anatomical connectivity of the brain.

The spatial span of an endogenously coarse-grained system can now be defined not as the metric volume in space occupied by the system, but as the number of spatial scales causally covered by its dynamics. According to Equation (11), the spatial span

of a network

can be calculated logarithmically by its elementary basis

as

. For example, if we consider the human brain, which contains approximately 86 billion neurons, and assume that the causal scope of a neuron, as detected experimentally by single-cell stimulations (Kwan and Dan 2012), is

, then the spatial span of the human brain can encompass 7 or 8 scales, beginning with individual neurons in the elementary basis. For a flock of starlings, assuming it consists of about 10 thousand birds, with

(Ballerini et al. 2008), its spatial span would range between 4 and 5 scales (

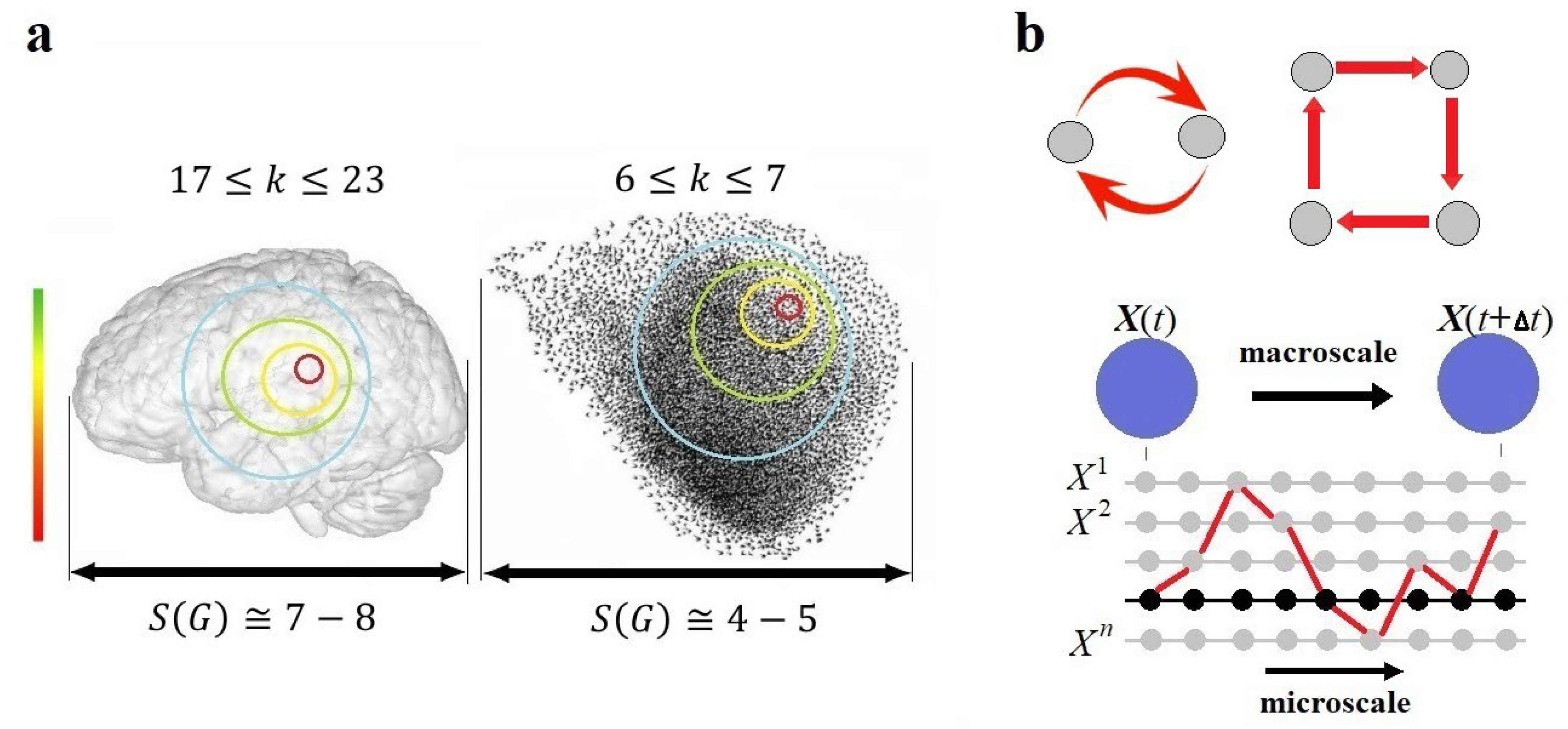

Figure 7a). Of course, in both cases, the number of scales would increase significantly by shifting the elementary basis to the atomic scale. Note also that the value of

may vary across scales even within the same system. At the molecular scale, the causal scope, influenced by the topological scale parameter

, is likely to differ from that at the neural scale.

Another important feature of scale transitions is that they can essentially change the causal structure of a system at each scale. For a dynamical system

, the causal scope means that a variable

, associated with a microevent at time

, can simultaneously affect

other variables, generating multi-body causal chains. Circular causation arises when one (or more) of the affected variables causally impact

at time

(

Figure 7b). However, circular causation at a smaller scale may not be observable at a larger scale, and vice versa. Macroscopic systems can, thus, exhibit nontrivial complex behavior that could not be inferred from their microscopic components. The CEP can explain how complex nonlinear phenomena can emerge on multiscale networks from linear causal chains solely due to scale transitions, e.g., when a system constrains itself to move through a cyclic attractor in phase space. In this context, the CEP underlies the renormalization group formalism in condensed matter physics, in terms of critical phenomena on Ising models that are typically characterized by spontaneous avalanches across scales (di Santo et al. 2018; Lombardi et al. 2021).

As stated, the CEP is not a reductionist principle. From the reductionist perspective, we should ultimately agree that all endogenously coarse-grained systems, including ourselves, have no biological individuality because only atoms (or quanta) genuinely exist, and have causal power. In contrast, the CEP asserts that all scales are ontologically valid and causally closed. According to the law of conservation of causation, scale transitions preserve the quantity of causation invariant in dynamics when a system passes from one state to another regardless of the scale of observation. However, observations of the system’s causal structure at the macroscale do not allow one to uncover its causal structure at the microscale, and vice versa, so reduction is precluded (

Figure 8).

On the other hand, the CEP can explain the problem of indeterminism for living organisms in the context of their biological freedom to respond to external stimuli without resorting to mental downward causation (

Figure 5). First, causation is not synonymous with determinism which heavily relies on the idea of predictability as seen from the perspective of a perfect observer like an omniscient Laplacian demon. Every event is said to be completely predetermined from the past so that randomness (stochasticity) only appears to an observer lacking perfect knowledge. In contrast, causation requires only irreflexivity and transitivity by Equations (1.1) and (1.2). No event can be a cause of itself as every event, associated with the state of a system, is necessarily preceded by other events, including its previous state. Even if the dynamics of organisms are entirely deterministic at the atomic scale, their macroscopic behavior can still have its own causal structure that may not be derived from the causal structure at the microscale. Meanwhile, the law of conservation of causation tells us that there is nothing new added to the “quantity” of causation at the scale of organisms compared to the “quantity” of causation they possess at the atomic scale within their spatial span (

Figure 7a). Since their behavioral response to external stimuli is not reducible to atomic interactions, it cannot in principle be proven (or disproven) that the response has been predetermined from the past. According to the CEP, all causal structures within the system’s spatial span are consistent so that our free will can be preserved without involving mental downward causation or quantum indeterminism.

So, we may be puzzled when observing systems as different as a simple pendulum and the human brain. The dynamics of both are summed up at the macroscale to a consolidated one-body causal chain despite a huge difference in the complexity of their causal structures at lower scales. (

Figure 8). Thus, multiscale hierarchical organization provides not only the biological individuality of organisms based on their internal causal connectedness but also their biological freedom to adapt to the environment. Their ability to adapt is selectively encoded over evolutionary time-scales in the entangled and circular multi-body causal chains pervading their spatial span at all scales (

Figure 7b), while atoms, the organisms consist of, do not adapt but follow their deterministic ways.

The following sections will present a mathematical demonstration of how the CEP can be applied to multiscale, hierarchically organized networks.

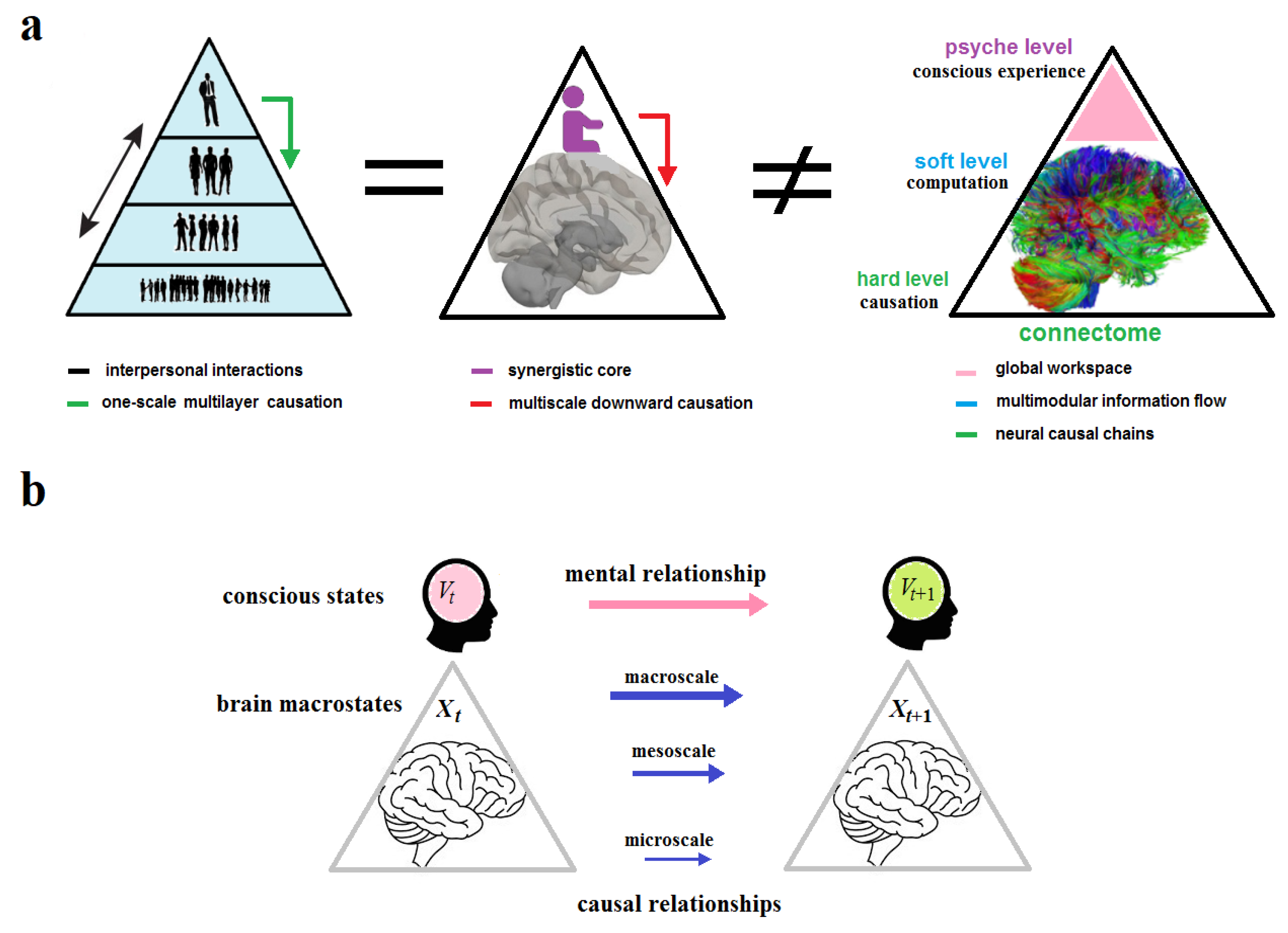

8. Hierarchical organization of Complex Systems

Hierarchy is a universal feature of complex systems in social sciences, biology, and neuroscience (Mihm et al. 2010; Kaiser et al. 2010; Deco and Kringelbach 2017; Hilgetag and Goulas 2020). In causal analysis, however, this term must be taken with caution since there are two very distinctive types of hierarchy. It follows from the fact that “hierarchy” can be conceptualized in two relevant but mathematically different ways.

8.1. Flat Hierarchy

In literature, hierarchy is typically defined as a set of elements (nodes) arranged into ranks or layers. In its most general mathematical formulation, a hierarchy is an acyclic directed graph , also represented as an upper semilattice , where symbolizes subordination in the usual mathematical sense of order. A canonical example is a power hierarchy, which consists of a central authority that is transferred down across subordinated ranks to exert the chains of command and control. The order arises spontaneously within the hierarchy across ranks. In general, given a set , the number of ranks (the height of the hierarchy) is determined by the degree of branching, i.e., by the number of subordinates each node has on average. The can be decomposed by linear chains, consisting of subordinated nodes over all ranks in the hierarchy. But such a representation produces great confusion that is responsible for assuming downward causation in complex hierarchical systems.

First, this definition only characterizes the simplest form of a hierarchy where all layers are presented at the same scale. A much more complex example is a nested hierarchy which is composed of subsystems that, in turn, have their own subsystems, and so on. The nested hierarchy is a multiscale modular structure that is nearly decomposable (Simon 1969). Simon argued that near-decomposability (modularity) is a pervasive feature of natural complex systems because it provides the emergence of complexity from simple systems through stable intermediate functional modules that allow the system to adapt one module without risking the loss of function in other modules (Meunier et al. 2009). Importantly, unlike a one-scale (or flat) power hierarchy where nodes (elements) are distributed across layers with one node at the top, which is superior to all others, and those at the bottom, which are inferior to all others, in a multiscale hierarchy all nodes are uniformly placed in the lowest layer (scale) as the elementary basis above which modules unfold.

8.2. Multiscale Modular Hierarchy

The multiscale hierarchy is a power-set

that can be mapped onto an upper semilattice

by condensing all subsets (including one-element subsets) of

as nodes with no interior content at a given scale:

. Mathematically, the multiscale hierarchy can be defined as an ideal

, a structure on the elementary basis

, all subsets of which satisfy the following conditions:

In the biological context, the closure of the hierarchy from above by the conditions (12) establishes the boundary between an endogenously coarse-grained system and its environment as a necessary prerequisite for its self-organization and autonomy. In the neuroscientific context, the closure is also a prerequisite for the existence of the global workspace (Dehaene and Naccache 2001) and non-trivial information closure (Chang et al. 2020), both associated with the emergence of consciousness in the brain. It is important to note that closure is a universal property of independent of the size of its elementary basis, such as the number of neurons in a neural hierarchy: both the human brain and the mouse brain are hierarchies closed from above. Thus, this property must be present across species (whereas cultures of neurons or slices of cortex from in vitro experiments lack it).

Another universal property of is its self-similar (fractal) architecture or scale-invariance, viewed as one of the fundamental features of hierarchy. Mathematically, any closed subset in the elementary basis of a hierarchy can spontaneously generate its own sub-ideal, . This makes hierarchy a universal scale-independent phenomenon of nature that can spontaneously emerge over any set of physical units that are causally (and informationally) connected. Thus, both closure from above and self-similarity of hierarchy are natural prerequisites for concepts such as biological individuality (Krakauer et al. 2020), which can evolve at any level of organization and be nested across scales.

In network science, a variety of different measures are suggested to detect connected populations in networks (Rubinov and Sporns 2010; Lynn and Bassett 2019). Unfortunately, the words “level”, “layer” and “scale” are often used interchangeably in the literature. This terminology confuses causal analysis of complex systems. Here and below, these terms will be strictly separated. While “scale” will obviously mean spatial (or temporal) scales arranged logarithmically according to Equation (11), the term “layer” will exclusively refer to the structural organization of a system, studied at the same scale of observation. So, the power hierarchy, the cortical hierarchy of pyramidal cells, or an artificial input-output neural network will all be called